ABSTRACT

This article analyses outcome mapping monitoring data to identify which strategies were effective for engaging practitioners and policymakers with research projects in four countries – Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia. It applies a qualitative thematic approach to analyse and code monitoring data against research into use strategies. The article identifies and discusses three emerging themes: early engagement, using existing and new forums and seizing opportunities. It discusses the contextual difference and the relevance of the outcome mapping methodology for research into use and is relevant for those seeking to engage and influence stakeholders with their research and programmes.

Introduction

The Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE) consortium used outcome mapping methodology as an approach to plan, implement and monitor its research into use (RIU) work in Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia. Outcome mapping is a planning, monitoring and evaluation approach that helps organisations understand their contribution to change (Earl, Carden, and Smutylo Citation2001). This paper applies a qualitative thematic approach to code and analyse three years of quarterly monitoring data. It identifies key strategies used to engage stakeholders and discusses to what extent these differ or share similarities across contexts.

The paper adds to a growing body of work on RIU and may be relevant for organisations and individuals seeking to influence others with their research. As the analysis is descriptive in nature and specific to each context, it is likely to be of particular interest for those working in East and Southern Africa. The paper presents one way to analyse and use outcome mapping monitoring data for evaluative thinking and programmatic learning – which may inform the work of programme managers and monitoring and evaluation specialists applying outcome mapping principles.

Research into policy and practice

Different terminology has been used to describe how research findings are taken up by various stakeholders – including knowledge translation, research utilisation, research to policy, research into use and research uptake (Bedford et al. Citation2017). For the purpose of consistency, this article will use the term “research into use”, defined as “the uptake of research which contributes to a change in policy or practice” (CARIAA Citation2017).

Evidence generated through academic research is relevant to a range of actors, including policymakers (local/national government officials, civil servants and political representatives), international agencies, donors, and implementers such as NGOs and civil society organisations (Hennink and Stephenson Citation2005). Researchers utilise various strategies to influence these stakeholders to engage with research findings: from early engagement in the research process, working in partnership with the desired end users, packaging research findings to meet the needs of different audiences (i.e. tailored policy briefs), as well as budgeting for and implementing research dissemination activities (Hanney et al. Citation2003; Hennink and Stephenson Citation2005; El-Jardali et al. Citation2012).

There is a growing body of work on the unique challenges of using research to engage policymakers in low- and middle-income countries (Hennink and Stephenson Citation2005; Young Citation2005; Nabyonga-Orem and Mijumbi Citation2015). These challenges include understanding the local political context, the (sometimes disproportionate) influence of external actors such as donors, and the changing role of civil society organisations (Young Citation2005). This paper adds to that discussion by documenting experiences from four East and Southern African countries.

While RIU strategies have been described elsewhere, this paper aims to make a unique contribution through documenting which strategies have been effective across the SHARE research programme. The thematic analysis shares successful early outcomes as well as challenges from five water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) research projects.

Research into use in the SHARE programme

SHARE was funded by DFID as part of their research and evidence portfolio. Between 2015 and 2018, SHARE funded five implementing partners to conduct sanitation and hygiene research projects in four countries: the Centre for Infectious Disease Research Zambia (CIDRZ), Great Lakes University Kisumu (GLUK) in Kenya, the WASHTED Centre at the University of Malawi (UNIMA), the Mwanza Intervention Trials Unit (MITU) and WaterAid in Tanzania.

Research into use was conceptualised as one of the three core areas of the SHARE programme and was budgeted for from the outset. The programme’s theory of change (ToC) aimed to facilitate RIU through a range of approaches, including communication, translation, convening, knowledge synthesis and capacity building (SHARE Citation2019a). The programme had two full-time RIU staff and one full-time monitoring and evaluation specialist based at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) – as well as staff working on RIU across all five partner institutions. Resourcing RIU was essential to plan, implement and monitor this work – as well as to contribute towards positive RIU outcomes.

Outcome mapping

Outcome mapping is an iterative tool that helps teams design and plan for the results they wish to bring about through working in collaboration with other actors (Earl and Carden Citation2002). Outcome mapping is designed to work in complexity and it focuses on contribution to change rather than attributing change to one single actor (Earl, Carden, and Smutylo Citation2001).

The Rapid Outcome Mapping Approach (ROMA) involves mapping and identifying the key stakeholders (known as boundary partners) within an organisation’s sphere of influence (ODI Citation2014). Project teams then write outcome challenges – statements describing the highest possible level of change from each boundary partner group. These are accompanied by a series of progress markers describing the observable steps towards change – expect to see, like to see and love to see. Progress markers are observable changes in behaviour, attitudes, relationships or policies from boundary partners that implementers aim to influence. Teams then develop relevant strategies to contribute towards this change. Progress markers are monitored and may be adjusted if the steps towards change are inaccurate or to account for unpredictable outcomes.

Outcome mapping in SHARE

Outcome mapping was built into SHARE’s logframe with a quantitative outcome indicator measuring the percentage of progress markers met. Some examples of SHARE progress markers are: international agencies provide feedback and advice on research (expect to see); NGOs adapt WASH programmes to include food hygiene components (like to see); donors co-fund new research related to urban sanitation demand-creation (love to see).

Each implementing partner used the outcome mapping approach to develop a plan for engaging seven key groups of stakeholders (donors, national government, local government, national research institutes, NGOs, international agencies, and project participants) with the aim of getting their research into use. They used ROMA to generate outcome challenges, progress markers, and strategies to influence and engage each stakeholder group (ODI Citation2014). Implementation lessons from SHARE’s use of outcome mapping have been documented elsewhere (Balls Citation2018).

Partners provided monitoring reports against outcome mapping plans on a quarterly basis. These reports consisted of two sections; first, updates on planned RIU activities and strategies and, second, reported change against progress markers. For changes in progress markers, partners were asked to indicate contributing factors (including related activities/strategies) and provide evidence of change. This allowed the programme team to link changes in progress markers with specific strategies from monitoring reports. This monitoring data is the basis of analysis for this paper. The paper is also informed by annual workshops with partners, which provided an opportunity to discuss and verify monitoring data.

Methodology

This article applies a thematic qualitative approach to analyse outcome mapping monitoring data (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). Existing monitoring data were entered into a relational database for qualitative coding and thematic analysis (SocioCultural Research Consultants Citation2018). An individual record was created for each progress marker with some degree of change reported over the past three years. Each record was tagged to the relevant implementing partner, country, target stakeholder group and level of change (expect to see, like to see or love to see). After this process, there were 181 progress marker records in the database.

A deductive and inductive analytical approach was applied. The thematic analysis followed six steps: familiarisation, coding, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining themes and writing up narratives (Clarke and Braun Citation2013). The authors read each record in full to familiarise themselves with the content before coding. Coding was done against three key areas. The main coding focus was against an evolving list of RIU strategies and this paper primarily focuses on the analysis of these strategies. Coding was also done against the outcomes defined in the SHARE ToC. The ToC outcomes are: influencing key actors to discuss new issues; plan differently; coordinate; invest; implement; monitor; investigate (SHARE Citation2019a). Finally, progress markers were coded according to whether partner monitoring data reported observable changes in behaviour, attitudes, relationships or policies. These latter two areas of coding have informed this analysis but were primarily used to inform SHARE’s programme report (SHARE Citation2019b).

After coding, the authors reviewed the number of coding incidences for each strategy against stakeholder groups, implementing partner and country. They used this review to search for themes, identify emerging themes and review related records in depth. They then reviewed themes, reflecting together on whether the themes told a comprehensive story of the data, and collapsed and split themes as needed. Themes were defined, named and written up in the narratives presented here.

Records were divided for review – one coder reviewed all records for three implementing partners and the other reviewed all records for two partners. To ensure consistency, each coder cross-checked some records from the partners that they did not code. Drafts of the paper were also shared with partners and their input was incorporated into the final version.

Findings

This section presents a summary of qualitative outcome mapping monitoring data as well as a thematic analysis relating to three broad themes. It also briefly discusses outcome mapping as a framework for analysis.

As terminology varies across disciplines and contexts, we have provided definitions for each RIU strategy.

Convene events: The implementing partner organises and convenes an event to introduce the project, get stakeholder input or share research findings.

Create and disseminate resources: The implementing partner creates a resource based on their research (i.e. report, policy brief, poster, journal publication) and shares this with stakeholders.

Establish advisory group: The implementing partner establishes a project advisory group or steering committee and invites stakeholders to join it.

Give technical input: The implementing partner provides technical or research expertise to stakeholders.

Have bilateral meeting: The implementing partner meets one on one with a particular stakeholder.

Involve in project development: The implementing partner involves stakeholders in the development, design and early stages of the research project.

Meet community members: The implementing partner directly engages members of the community targeted by the research intervention in face to face events and interactions.

Meet new stakeholders: The implementing partner meets with stakeholders they did not previously have a relationship with.

Present at conferences: The implementing partner presents research plans, protocols or findings at national or international conferences.

Seize new opportunities: The implementing partner does something different such as accepting an event invitation, meeting a new stakeholder or participating in a proposal bid.

Use existing forums: The implementing partner attends or presents at existing local/national level mechanisms such as technical working groups and NGO networks.

Use networks: The implementing partner uses existing networks to meet with and build relationships with stakeholders.

Work in partnership: The implementing partner works with a stakeholder on an aspect of the research project, or on a different project, policy or programme.

Work with local government: The implementing partner works with local government as a step towards influencing national government.

Effective strategies for stakeholder engagement

This section summarises the RIU strategies reported by partners within monitoring data as strategies to meet progress markers and highlights the most common approaches used.

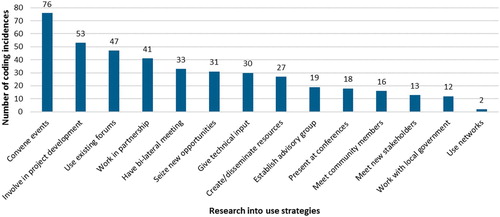

summarises the number of times each strategy was coded (across all stakeholder groups and all implementing partners).

As seen in , the most commonly used strategy was convening events (n = 76). Event convening was used to introduce stakeholders to the project, get their input and to share project findings. A related strategy was using existing forums (n = 47) such as technical working groups to introduce research plans and disseminate findings. Another important strategy was involving stakeholders in project development (n = 53). SHARE’s RIU strategy prioritised engaging stakeholders from the beginning of research projects and continuing this engagement over time in order to maximise future uptake of the research findings. In some cases, implementing partners worked in partnership (n = 41) with their stakeholders on aspects of the research project or other related work.

The number of coding incidences per strategy against each stakeholder group – which was the starting point for a deeper analysis of emerging themes – is summarised in . Less common to more commonly coded strategies are shaded from light to dark orange. Grey cells represent strategies that were not coded against the corresponding stakeholder groups.

Table 1. Number of coding incidences of strategy against stakeholder group.

shows that implementing partners used multiple strategies to engage all stakeholder groups. Implementing partners used 10–12 different strategies for each stakeholder group, with the exception of the project participants group. Some strategies were used across all groups, such as convening events and involving stakeholders in project development. Certain strategies were particularly relevant for some stakeholders – for example, it was common to involve local government in project development (n = 23) and convening events was a common strategy to engage national government (n = 21). Some strategies were linked to certain stakeholder groups – for example, presenting at conferences related mainly to national research institutes (n = 8) and meeting community members related mainly to project participants (n = 11).

Progress markers with no reported change

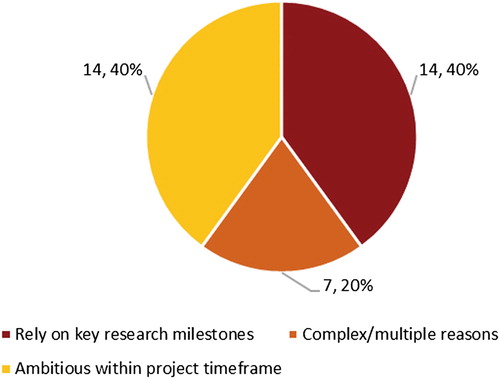

Due to programme funding, resource and timelines, this paper was written before the SHARE programme closed. This means it could not include monitoring data on final research results and any related changes in progress markers. At the time of analysis, there were 35 progress markers with no reported change. These were not included in the database and thematic analysis. As there was no monitoring data associated with these progress markers, it would not have been possible to apply a consistent analytical approach. The authors, therefore, reviewed these separately and coded each progress marker against potential reasons why change was not reported ().

Some of these progress markers related to change that could only take place once a specific research milestone had been reached, such as stakeholders discussing final research findings (n = 14). As the programme was being implemented at the time of writing, some of these milestones had not yet taken place. Other progress markers were very ambitious or aspirational within the project timeline of three years (n = 7). The remainder were coded as complex – for these progress markers, it was not easy to define any one reason why change had not happened (n = 14).

A discussion with the programme team generated a range of possible explanations for complex progress markers, one or several of which may apply to each progress marker. These included: challenging stakeholders who were hard to communicate with; areas that are particularly hard to monitor and see tangible change in (i.e. advocacy); areas that are hard to influence such as policy action or financial investments; progress markers that require seizing opportunities and being in the right time and right place to engage stakeholders. The fact that 40% of progress markers were coded as complex illustrates the complexity of RIU change processes, related monitoring challenges and the difficulty of predicting how and when change happens.

Outcome mapping as a framework for analysis

This section briefly analyses monitoring data against the levels of change defined in outcome mapping progress markers. Outcome mapping conceptualises expect to see, like to see and love to see progress markers as incremental steps on a ladder towards significant change (Earl, Carden, and Smutylo Citation2001). These levels of change were defined differently by each implementing partner, depending on the initial relationship they had with their stakeholders. For instance, a partner with a strong existing relationship with local government might define their participation at meetings as expect to see whereas a partner with no pre-established ties might define this as love to see. It is also to be noted that reporting of activities reflected partners’ agreed plans developed in the outcome mapping process. Although there was flexibility to add activities iteratively, the linear nature of monitoring templates may mean that unplanned strategies were not fully documented.

Our analysis found that the frequency with which different RIU strategies were coded against progress markers varied for each level of change; for example, different strategies were used to achieve expect to see, like to see and love to see progress markers. Monitoring data from expect to see progress markers described the early development of relationships through engaging stakeholders in project development, convening events, existing forums and bilateral meetings. The like to see level shows continued engagement through existing forums, new forums and convening events. Monitoring data from like to see and love to see progress markers describes increasing recognition and trust from stakeholders through taking up new opportunities to work in partnership, give technical input, present at events and seek funding.

Themes

While lists 14 strategies, the main analysis focuses on three broad themes that emerged as relevant for delivering RIU work and contributing towards early positive outcomes. These themes are:

Early engagement through event convening

Using existing and new forums to inform policy

Creating and seizing opportunities.

For each thematic area, we discuss below which strategies worked well for different stakeholder groups and illustrate this with examples of partner strategies and early outcomes.

Early engagement through event convening

As shown in , engaging stakeholders in project development and convening them through events were the most commonly used strategies. Involving stakeholders in early project development and design proved to be key for all implementing partners. This strategy was used across all stakeholders but was especially relevant for engaging local and national government bodies. Convening events was a key strategy to facilitate early engagement and these codes often co-occurred in our analysis.

Early engagement through event convening allowed implementing partners to understand community needs, as well as to facilitate community entry through gatekeepers. It also helped to improve implementation. CIDRZ noted that early stakeholder engagement meant they could effectively communicate and coordinate with others in Lusaka to avoid multiple projects in the same geographical site, potentially affecting the research. Convening events played an important role in initiating and maintaining a direct dialogue with research participants. For example, before the project began MITU invited parents for meetings to provide information and later engaged them with their child’s health results.

Implementing partners used early engagement events to ask stakeholders for feedback and input into project inception and design. This would often result in stakeholders following up to ask for further information or to invite implementing partners to other events. For example, CIDRZ convened an event introducing the theoretical framework used for the project and a staff member of the Ministry of Health followed up asking to adapt the framework for a presentation on behaviour change. WaterAid found that involving municipal level stakeholders in the research process through early meetings led to positive outcomes. Stakeholders felt that they could take ownership of research findings and use these to inform their own plans.

The town sanitation and water authority has gained interest and feel part of the research team. They are keen to take ownership of the research findings as they realised it will inform their plans on designing relevant urban waste water infrastructure for the town. The managing director is fully converted to the sanitation research and is leading his team to support the research. (WaterAid (from monitoring report))

Early engagement also helped to build partnerships. Several implementing partners highlighted that early engagement enabled stakeholders to build an understanding of research objectives and develop a shared history. UNIMA described getting to know one stakeholder and building mutual respect over time. Relationships built early on sometimes developed into partnerships. For example, WaterAid involved the Tanzanian Ministry of Health (MoH) through inviting them to inception meetings, asking for input on study design and for their participation in implementation. In the longer term, this resulted in a strengthened partnership between WaterAid and MoH:

The Ministry of Health has engaged itself in the project from the very beginning. They participated in the review of the protocol and the consultation meetings. At the local level, the engagement has enabled the smooth implementation of project activities. The MoH forms part of the research team at the local level. The Municipal Health Officer participated in the training of enumerators. (WaterAid (from monitoring report))

While convening events initially allowed partners to introduce their interventions, they also played a key role in framing, discussing and interpreting research findings with stakeholders. For example, GLUK used convening events to explain formative research findings regarding WASH and food hygiene. These findings caused an attitude change for county community health volunteers, which led to noticeably greater interest and engagement.

The community health volunteers were shocked at the situation and took it seriously. We felt the scale of the problem hit home and their awareness grew a lot. People found it eye opening and shocking. An NGO then offered to host the next meeting and requested circulation of our formative research information. (GLUK (from outcome mapping workshop))

The early engagement of stakeholders through event convening was an important strategy that helped build a solid foundation for successful research implementation, building relationships, establishing partnerships and translating research findings.

Using existing and new forums to inform policy

All the countries that research projects took place in had pre-existing mechanisms for informing policy; often government convened technical working groups (at both the district and national level), NGO networks and donor/development partner forums. These groups often met on a quarterly basis and provided a formal means to share ongoing work with stakeholders, feed into government processes and collaborate on advocacy and policy work. The use of these existing forums – as well as the creation of new forums – emerged as key strategies with these codes frequently co-occurring.

All but one implementing partner used these established mechanisms to share plans, disseminate results and get feedback. Attending these forums was useful for reaching a pre-established group of stakeholders who met regularly from NGOs to local/national government, international agencies, donors and national research institutes.

Some partners had very little previous engagement with these groups and became aware of them through the stakeholder mapping phase of outcome mapping. For these implementers, there was an initial phase of seeking access to these forums. This was not always straightforward and required persistence. Some partners convened their own introductory event to meet stakeholders who could then invite them to join existing forums. On the other hand, partners already engaged used existing forums to reach international agencies or donors – before inviting them to join a new forum or meet bilaterally.

We are developing relationships with the UNICEF nutrition and community health teams through attendance at a range of technical working groups. These have led to successive meetings to discuss SHARE work in more detail. (UNIMA (from monitoring report))

In the November Development Partners meeting, some findings from SHARE research were presented. The chair of the meeting appreciated what this research is going to achieve and recommended the use of research findings to inform sector dialogue and decision making. Development partners at the meeting, KFW, GIZ and SNV, later participated in our WASH symposium in December. (WaterAid (from monitoring report))

Attending existing technical working groups enabled partners in Malawi and Tanzania to establish new relationships with international agencies and donors, leading to bilateral meetings and future opportunities for partnership. In Malawi, ongoing engagement with the NGO WASH network led to UNIMA building new partnerships as well as influencing the network’s advocacy framework to include links between WASH and nutrition.

In Kenya, GLUK took on the leadership and organisation of the county-level WASH policy and advocacy working group. This has had significant impacts on their RIU work, enabling them to convene key stakeholders and create an audience for research findings. In Zambia, CIDRZ were invited to be secretary of the local epidemiology and health promotion technical working group and in Malawi UNIMA were invited to chair the WASH research and knowledge exchange thematic working group.

Existing forums were often used in combination with the creation of new forums – three implementing partners created a research advisory group (RAG) to regularly convene selected stakeholders. These new groups were particularly relevant for involving government, international agencies, NGOs and donors in an advisory capacity. In Tanzania, geographical distance meant that it was challenging for MITU to access existing national forums – they, therefore, created their own project steering committee to engage key stakeholders. Both MITU and UNIMA chose to hold some RAG meetings in the capital city – although they weren’t based there themselves, most of their stakeholders were.

Research advisory groups also helped partners build relationships at the organisational level – for example, in Malawi the RAG agreed to mentor another UNIMA project. These new groups enabled partners to build closer interpersonal relationships with individuals, leading to opportunities to attend other events or get involved in new projects. In Malawi, donors and government representatives in the RAG invited UNIMA to join existing forums which they previously did not have access to and to take part in policy review processes.

This was discussed at the RAG meeting in March and [the Ministry of Health representative] concluded that SHARE will now be invited to the Partners Coordinating Meeting currently coordinated by the Global Sanitation Fund where we can work on issues related to the National Sanitation and Hygiene Coordinating Unit. (UNIMA (from monitoring report))

There are also emerging examples of partnership going beyond SHARE research projects – this aligns closely with the OM principle of being actor focused rather than project focused. Each research project exists in the context of relationships between individuals and organisations – developing stakeholder relationships at the organisational level is key for ongoing engagement beyond project timeframes. In Tanzania, WaterAid facilitated a meeting where stakeholders formed a committee to mobilise financial resources and develop a business proposal for municipal sanitation and hygiene beyond the project.

Across SHARE, donors and international agencies have been some of the most challenging stakeholders to engage. Using existing forums was a key strategy to get time and input from these busy stakeholders. Implementing partners also created new forums in the absence of accessible mechanisms. Some partners have used both approaches to build and develop relationships with stakeholders.

Creating and seizing opportunities

A key emerging theme for positive RIU outcomes was creating, identifying and seizing new opportunities. There were examples of this across all implementing partners relevant to a range of stakeholders with particularly significant examples for donors, national government and international agencies – perhaps because partners needed to be reactive to their timelines. It was important to engage across and with multiple stakeholders as government and international agencies often work in partnership in the project contexts.

For example, CIDRZ was invited to host a DFID-organised UK parliamentary visit to their sanitation behaviour change research project in an informal settlement in Lusaka – this opportunity came with a short lead time but the partner recognised it as a valuable influencing opportunity and was able to quickly prepare. This engagement contributed towards a strengthened relationship with DFID in Zambia and a successful application for a behaviour change intervention on cholera.

We have had the best engagement with DFID. The VIP visit opened doors to recognition and funding and has led to various collaborations. (CIDRZ (from outcome mapping workshop))

As noted earlier, GLUK now leads the WASH policy and advocacy working group at the county level in Kisumu, Kenya. They have also reacted quickly to invitations to attend county and national level meetings, sometimes organised at short notice or taking place in a distant location. This ongoing engagement has led to increased influence at county level. GLUK is now seen as a valued partner by county-level government, with a member of staff noting at an outcome mapping workshop that “the County Public Health Officer categorically said they really need input from us before the sanitation policy and bill is finalised”. GLUK also gave input to the county integrated community development plan and were able to ensure that hygiene was included in the plan.

In Malawi, UNIMA was invited to take part in multiple government policy consultations and won consultancies to review outdated WASH strategies to create an updated and aligned National Sanitation and Hygiene Strategy. Contributing factors to this success were being present at key meetings such as technical working groups, becoming known by government stakeholders, consistently attending new forums and saying yes to opportunities. In Tanzania, WaterAid was able to adapt their plans and timeline to input into town level planning. Flexibility was important to ensure that their research could influence policy and practice.

All implementing partners have reacted quickly to emerging funding opportunities; for example, in Tanzania MITU provided technical expertise to a regional group which led to their inclusion in a new research proposal. Another interesting outcome has been implementing partners collaborating on new research proposals; prior to SHARE they had not worked in partnership. Three implementing partners were awarded funding for a new regional collaborative project establishing an inter-disciplinary network on WASH around the African Great Lakes led by the WASHTED Centre at UNIMA.

A factor that helped implementing partners to seize opportunities was using networks and key contacts strategically. For instance, LSHTM based co-investigators were able to support implementing partners in Kenya and Zambia to leverage their existing relationships with donors and increase the number of bilateral meetings. In Kenya, GLUK was invited to attend a regional USAID meeting in Tanzania and input into their work on children in urban informal settlements. This led to an invitation for GLUK to input into new guidelines on research on East Africa.

Our colleagues in London were instrumental in linking us up with DFID in Zambia. Our London PI knows the WASH specialist in DFID Zambia so helped us to link up and share. Because of those engagements, DFID Zambia have asked us to see if we can do work on cholera prevention. We have submitted a proposal which has gone on to the next stage. (CIDRZ (from outcome mapping workshop))

There are also examples of stakeholders introducing partners to new opportunities; in Zambia, CIDRZ was invited to join a panel for city mayor candidates and talk about the health impacts of poor sanitation. Interestingly, there were only two incidences when the use of networks was described in partner monitoring data. Perhaps networks and interpersonal relationships are a form of tacit knowledge which are less likely to be explicitly described as contributing factors to positive outcomes.

Contextual challenges

This section discusses the differences across context, highlighting key challenges for the implementation of RIU strategies. While all projects were implemented in East and Southern African countries, implementing contexts varied significantly.

The SHARE programme found that the first stage of ROMA, in which implementers map the political and institutional environment, was particularly important for understanding context (ODI Citation2014). This process enabled each implementing partner to map their context and design appropriate strategies to reach different stakeholders. Stakeholder mapping was especially relevant for understanding the different functions of local/national government bodies, as well as identifying key international agencies and donors.

The location of each implementing organisation in relation to their stakeholders presented challenges in access and engagement. Two implementing partners had their offices in the capital whereas three were based in non-capital cities. This geographical distance was complicated by the fact that some partner research sites were in a different area entirely, with research teams dispersed between their base and research site.

Stakeholders such as donors, international agencies and national government ministries tended to be based in the capital city, often with decentralised functions in each district or county. All four countries had some degree of local government decentralisation. Some partners engaged local representatives and used this group to feed into national government whereas other partners liaised in parallel with local and national government representatives. In Kenya, GLUK noted that it was important to first engage government at the county level and to later seek to influence national-level government. In the case of Tanzania, the two implementing partners had to factor in the ongoing process of government ministries moving from Dar es Salaam to Dodoma.

Partners based in a capital city found it easier to convene national stakeholders for events and to seize emerging opportunities. As mentioned earlier, CIDRZ hosted a donor visit to their research project in urban informal settlements in Lusaka. This type of stakeholder engagement opportunity may not have been available to partners based far from administrative capitals.

Implementing partners with dispersed teams and offices used a range of strategies to reach geographically distant stakeholders including hosting events in the capital. For example, the two Tanzanian partners (MITU and WaterAid) worked in collaboration to host a joint research symposium in Dar es Salaam, where the majority of stakeholders were based. This was an effective way to bring together key stakeholders. As conceptualised in the outcome mapping approach, context is key and must be considered in planning, implementation and monitoring of strategies (Earl, Carden, and Smutylo Citation2001; ODI Citation2014).

Reflections and limitations

It is important to note that the data used for this analysis was monitoring data, the original purpose for which was improved programme implementation – as well as quantitative tracking for our logframe. The analysis process aimed to use messy, inconsistent and imperfect monitoring data for evaluative purposes. A limitation is therefore around data consistency – each implementing partner recorded monitoring data differently in terms of length, detail and communication style.

It is also relevant to acknowledge that implementers rarely have the time to analyse and learn from programme monitoring data; this analysis process created a space and opportunity for learning which was informative and useful for SHARE.

The authors acknowledge the importance of engaging communities with research processes; however, it was outside the scope of this paper to provide a detailed analysis on this topic (Chidziwisano et al. Citation2018). Reviewing fidelity to implementation plans or the effectiveness of research interventions also falls outside the scope.

Conclusion

This paper documents, analyses and discusses the strategies that the SHARE programme used to encourage research into use in East and Southern Africa. Our qualitative analysis of monitoring data found that implementing partners used a wide range of strategies to engage different stakeholders. Each partner utilised these strategies as appropriate to their existing relationships and different contexts. Key approaches across all implementing partners included convening events to facilitate early engagement, using existing forums and creating new forums to influence policy processes, and being open to and seizing emerging opportunities.

For SHARE, outcome mapping provided a conceptual framework to help us map, monitor and understand the strategies and processes that lead towards RIU outcomes. Outcome mapping was particularly useful for programmatic learning – detailed monitoring data enabled us to better understand how implementing partners contributed to change. Progress markers provided a useful framework to track changing stakeholder relationships. Outcome mapping concepts enabled us to plan, implement and document the steps towards change – although our analysis of unmet progress markers demonstrates the unpredictability and complexity of getting research into use.

While it is too early to see the uptake of research into high-level policy, the strategies documented in this paper have led to successful engagement and early outcomes across a range of stakeholders. The SHARE programme has also used this data to highlight significant outcomes in relation to our ToC in our programme report (SHARE Citation2019b). In the longer term, these RIU strategies may strengthen the uptake of SHARE research into policy and practice.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank our colleagues at CIDRZ, GLUK, UNIMA, MITU and WaterAid who have led on implementing the work described in this paper. Special thanks to Joseph Banzi, Dr Caroline Chisenga and Dr Tracy Morse for their inputs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Emily Balls holds an MA in Education and International Development from University College London. She was the monitoring and evaluation specialist for SHARE at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Her research interests include outcome mapping, adaptive management, and research uptake.

Nisso Nurova holds an MSc in Public Health from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. She has worked in research on the social determinants of health, as a team lead on a systematic review with the Hospital for Sick Children. Her research interests are in adolescent health and WASH.

ORCID

Emily Balls http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2917-5405

Additional information

Funding

References

- Balls, E. 2018. Applying Outcome Mapping to Plan, Monitor and Evaluate Policy Influence; Learning from the SHARE Research Consortium. London: Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE).

- Bedford, D. A. D., J. Turner, T. Norton, L. Sabatiuk, and H. G. Nassery. 2017. “Knowledge Translation in Health Sciences.” In Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, edited by S. Erdelez and N. K. Agarwal, 539–542. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- CARIAA. 2017. Guidance Note: The CARIAA RiU Learning Guide. Ottawa: Collaborative Adaptation Initiative in Africa and Asia (CARIAA).

- Chidziwisano, K., R. Daudi, S. Durrans, K. Lungu, K. Luwe, and T. Morse. 2018. Policy Brief: Engaging Participants in Community-Based Research. London: Sanitation and Hygiene Applied Research for Equity (SHARE).

- Clarke, V., and V. Braun. 2013. “Teaching Thematic Analysis: Overcoming Challenges and Developing Strategies for Effective Learning.” The Psychologist 26 (2): 120–123.

- Earl, S., and F. Carden. 2002. “Learning from Complexity: The International Development Research Centre’s Experience with Outcome Mapping.” Development in Practice 12 (3–4): 518–524. doi: 10.1080/0961450220149852

- Earl, S., F. Carden, and T. Smutylo. 2001. Outcome Mapping: Building Learning and Reflection into Development Programs. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

- El-Jardali, F., J. N. Lavis, N. Ataya, and D. Jamal. 2012. “Use of Health Systems and Policy Research Evidence in the Health Policymaking in Eastern Mediterranean Countries: Views and Practices of Researchers.” Implementation Science 7: 2. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-2

- Hanney, S. R., M. A. Gonzalez-Block, M. J. Buxton, and M. Kogan. 2003. “The Utilisation of Health Research in Policy-Making: Concepts, Examples and Methods of Assessment.” Health Research Policy and Systems 1: 2. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-1-2

- Hennink, M., and R. O. B. Stephenson. 2005. “Using Research to Inform Health Policy: Barriers and Strategies in Developing Countries.” Journal of Health Communication 10: 163–180. doi: 10.1080/10810730590915128

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Nabyonga-Orem, J., and R. Mijumbi. 2015. “Evidence for Informing Health Policy Development in Low-Income Countries (LICs): Perspectives of Policy Actors in Uganda.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management 4: 285–293. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.52

- ODI (Overseas Development Institute). 2014. ROMA: A Guide to Policy Engagement and Policy Influence. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- SHARE. 2019a. “Theory of Change.” Accessed May 1, 2019. www.shareresearch.org/our-research/monitoring-evaluation.

- SHARE. 2019b. SHARE End of Programme Report. London: SHARE.

- SocioCultural Research Consultants. 2018. Dedoose Version 8.0.42, Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data (2018). Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants.

- Young, J. 2005. “Research, Policy and Practice: Why Developing Countries Are Different.” Journal of International Development 17: 727–734. doi: 10.1002/jid.1235