ABSTRACT

Participation has been proposed to improve agricultural extension programmes in developing countries. This paper reports on experience with COCREATE, an approach to agricultural extension programmes that supports agricultural chain actors in self-directed learning in action research with smallholder farmers and local traders in Indonesia. This approach resulted in the changes in relation and task division between farmers and their local traders in the agricultural production and supply and chains, improved their market position and in new institutions.

Introduction

In improving quality of farmers’ produce, including lowering pesticide residues, many governments in developing countries have relied on agricultural extension programmes to improve their farmers’ knowledge and skills. These programmes focus primarily on production without focusing on local context. Engagement of local actors in extension activities (e.g. identifying problems and needs, developing solutions) has been proposed to improve these agricultural extension programmes (Baloch and Thapa Citation2019; World Bank Citation2010) to encourage farmers to improve their produce quality. The notion of market-driven extensions (MDE) has been developed (World Bank Citation2010) for farmers to be: (1) involved in identifying their initial situations; (2) organised into groups; (3) encouraged to grow high-value crops; (4) supported to improve produce quality; and (5) facilitated to markets (directly).

The MDE approach has embraced improvement of production and knowledge of the market. However, it overlooks the context of agricultural supply chain governance in developing countries. Traditionally in many developing countries, most farmers are connected to the local traders (local market players who connect farmers to markets) through agreed chain governance (Natawidjaja et al. Citation2007; Subervie and Vagneron Citation2013): local traders provide credit to farmers with the condition that the farmers are obliged to sell all of their produce only to them. Although they are fully dependent on each other, there is often little awareness of the challenges with which they are each faced (Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier Citation2019). Self-directed learning (SDL) characterised by active participation of actors to identify their problems and set their learning needs, and to learn from their experience and others’ experience and knowledge is the approach this paper embraces (Zoundji et al. Citation2016). This paper proposes a practical SDL approach to extension programmes, extending initial results reported in Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier (Citation2019), to improve value chain management between farmers and their local traders.

More specifically, this paper addresses the question “Can COCREATE support farmers and their local traders in developing countries in SDL activities to improve their own value chain management?” Action research with multiple farmers–local trader groups in a horticultural production centre in Indonesia has been performed to this purpose.

Agricultural extension programmes in developing countries

Different approaches have been developed and deployed by agricultural extension programmes in developing countries for decades. Broadly speaking, four categories of agricultural extension programmes can be distinguished: Training and Visiting, Farmer-to-Farmer Extension Programmes, Farmer Field Schools and Extension Programmes through information and communication technologies (ICT).

Training and visiting

Training and visiting is an approach developed by World Bank in the mid-1970s (Rocha Citation2017). This approach is still commonly used in developing countries to transfer knowledge from agricultural extension officers as senders to farmers as receivers (Benson and Jafry Citation2013).

Lack of participation of farmers in applying knowledge taught by agricultural extension officers is one of the challenges this approach faces. Agricultural extension officers determine the knowledge to be transferred, design and conduct training and visiting activities, and monitor and evaluate the outcomes (Benson and Jafry Citation2013; Rocha Citation2017). Local context is not always taken into account, making it often difficult for farmers to apply the knowledge acquired.

Farmer-to-farmer extension programmes

Farmer-to-Farmer extension programmes, also called Farmer-to-Farmer training or Volunteer-Farmer-Trainer, is an approach that involves trained farmers (as senders) to transfer knowledge to other farmers (as receivers) (Fisher et al. Citation2018; Kiptot and Franzel Citation2015). In this approach, selected farmers in a farming area are trained by agricultural extension officers or external parties to conduct field experiments (with support and packages of production input by agricultural extension officers). The trained farmers are then obliged to transfer the knowledge they obtained to other farmers in their area (Fisher et al. Citation2018; Kiptot and Franzel Citation2015).

Involving local farmers in transferring knowledge targets the challenge of including local context. However, often trained farmers lack the necessary technical skills needed, and motivation required (Fisher et al. Citation2018) to integrate this knowledge in the programmes they host.

Farmers Field School

Since the 1990s the Farmers Field School approach has been developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations explicitly to improve participation of local farmers to improve farming activities (Rocha Citation2017; Settle et al. Citation2014). In this approach, farmers are organised into groups consisting of about 25 persons per group. Each group is facilitated by one field agent who is usually an agricultural extension officer or by a farmer who has been trained in advance. These field agents train groups of farmers in standard procedures of farming, and provide packages (good quality seeds and other production inputs) to conduct field experiments. Facilitated by the field agents, groups of farmers meet periodically in the field to analyse the condition of crops in every stage of growth (Rocha Citation2017).

Despite some successful cases, this approach still faces major challenges in the sustainability of farmer participation (Scheba Citation2017). Lack of other chain actors’ involvement (e.g. market actors) is believed to be one of main factors for farmers to discontinue their participation in the programmes (Scheba Citation2017). In addition, even though this approach uses a participatory approach to some extent, the initiatives themselves (e.g. field experiments, production inputs) are organised by the field agents for the farmers, and knowledge transfer activities are most often still linear (from sender to receiver).

Extension programmes through information and communication technology

The relative recent development of ICT has encouraged scholars, governments, industries and non-profit organisations to develop ICT-based applications for agricultural extension programmes or so-called e-extension programmes (Kelly, Bennett, and Starasts Citation2017; Verma and Sinha Citation2018; Witteveen et al. Citation2017). Some e-extension programmes have been developed and tested in developing countries to, for example, facilitate interaction between cocoa farmers and agricultural extension officers in Sierra Leone on farming activities (Witteveen et al. Citation2017), between farmers and agricultural extension officers in India on farming methods (Verma and Sinha Citation2018), in Ghana on farm planning (Munthali et al. Citation2018), and in India to facilitate learning among and between farmers, agricultural extension officers, and scientists on farming practice (Kelly, Bennett, and Starasts Citation2017).

E-extension programmes are believed to have the potential to provide a means for effective and efficient knowledge sharing. However, in developing countries, this approach is often challenged by farmers’ limited digital skills and poor ICT infrastructure in many rural farming areas (Kelly, Bennett, and Starasts Citation2017; Munthali et al. Citation2018).

Self-directed learning

SDL, introduced by (Knowles Citation1975), is defined as

a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing appropriate learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes. (Knowles Citation1975, 18)

With respect to learners, in SDL, learners take control and responsibility in the learning process (Garrison Citation1992). Control is related to decision making, while responsibility is related to participation of learners in every step of the learning process (Garrison Citation1992). With respect to educators, in SDL, educators are facilitators (Bosch, Mentz, and Goede Citation2019). Facilitators encourage learners to engage, and facilitate access to information resources needed (Bosch, Mentz, and Goede Citation2019). In the process of SDL, knowledge is constructed not only individually, but also collaboratively through sharing knowledge, experience and information between learners, and between learners and facilitators (Bolhuis Citation2003; Garrison Citation1992; Knowles Citation1975).

The main goal of SDL is to increase learners’ capacity to find ways to solve their problems by themselves through collaboration with others: learning-to-learn (Garrison Citation1992; Knowles Citation1975).

A practical SDL approach to agricultural extension programmes based on co-creation: COCREATE

COCREATE is an SDL approach to agricultural extension programmes in which farmers and their local traders together not only identify the challenges with which they are confronted and explore potential solutions (Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier Citation2019) but also implement these solutions, reflect on their success/barriers encountered, and adapt their plans. This last phase, namely implementation and adaptation, is the focus of this paper. Facilitators play a role in: (1) organising meetings with external parties, e.g. extension officers, markets, government (on request); (2) visiting participants periodically (1–2 times a week) and inviting experts (when needed) to answer participants’ specific knowledge questions.

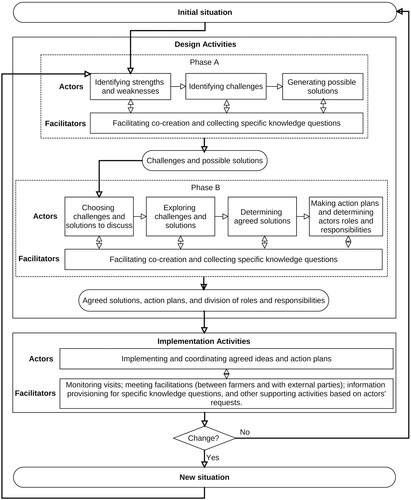

In COCREATE, there is no fixed line between design activities and implementation activities – the approach is cyclic with continuous feedback between the two types of activities, both in co-creation ().

Figure 1. COCREATE: a practical approach to agricultural extension programmes.

Note: Extending the approach presented in Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier (Citation2019).

Method

This study is performed as action research, in particular participatory action research (Kidd and Kral Citation2005), in which the COCREATE approach was implemented and evaluated in cases with local trader–farmer groups in a horticultural production centre in Indonesia, extending initial results reported in (Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier Citation2019).

Case study

This case study took place in Ciwidey, a subdistrict in the Bandung District, representative of horticultural production centres in Indonesia in terms of value chain management (Natawidjaja et al. Citation2007).

This case study represents a single context situation (supply chain situation in a farming area in Indonesia) with multiple cases of local trader–farmers groups (Yin Citation2003). A local trader–farmers group is a group of farmers whom are connected to a local trader in an agricultural production and supply chain system through agreed chain governance between themselves (discussed in more detail below). The unit of analysis of this case study is the relationship between local trader and farmers in each local trader–farmers group.

Three local trader–farmers groups who participated in the initial design activities reported in (Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier (Citation2019) continued their participation in the implementation and follow-up design activities.Footnote1 The number of farmers in each local trader–farmers group in this case study is provided in .

Table 1. Number of farmers in each local trader–farmers group.

Setting

The traditional division of tasks when this programme started was that local traders are the intermediary between the farmers and the market. In the local trader–farmers groups, there were informal (verbal) contracts in which local traders provide credit (in cash or kind of input production, e.g. seed, fertilisers, pesticides) to farmers with the condition that the farmers were obliged to sell all their produce only to them. With respect to selling systems, farmers delivered ungraded produce and local traders evaluated the quality of the produce, took care of all post-harvest activities (cleaning, sorting and grading) and decided on the most appropriate market. The price farmers were paid by their local traders was based on the price in the traditional market and farmers had little access to market information. This relationship provided few incentives for farmers to increase their produce quality and often lead to lack of commitment by farmers to the agreements in place (Natawidjaja et al. Citation2007).

Participants of COCREATE

The division of participants of COCREATE in the implementation and follow-up design activities are shown in .Footnote2 In the follow-up design activities, Groups 1 and 2 consist of local traders and farmers who work with these local traders, while Group 3 only consists of farmers.

Table 2. Number of participants in the implementation and follow-up design.

COCREATE implementation

The implementation of solutions and action plans agreed between April and June 2017 (see Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier Citation2019) were performed between July 2017 and April 2018. Two facilitatorsFootnote3 visited the three groups in the case study area, at least, 1–2 times a week for a period of 5 months, from August to December, after which from January to March, less-frequent visits, 1–2 times a month, were held plus additional meetings with extension officers and other experts to address specific needs and desires of local traders and farmers. After that, two follow-up design meetings were held in April 2018 supported by five facilitatorsFootnote4 and a researcher from TU Delft (to support the three groups).

Results

The results of COCREATE implementation are presented in chronological order following the activities in COCREATE: the initial design activities; implementation and follow-up design activities. With respect to value chain management, the results are categorised into: (1) production; (2) market; (3) finance; (4) logistics; and (5) institutions, i.e. governance, aspects (Kusnandar, Brazier, and van Kooten Citation2019).

The initial design activities: challenges, agreed solutions and action plans

The challenges, agreed solutions and action plans resulted from the initial design activities are provided in .

Table 3. Challenges, agreed solutions and action plans (Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier Citation2019 adapted).

Implementation activities and follow-up plans

During implementation activities the groups: (1) held informal meetings among themselves to discuss farming methods; (2) contacted supermarkets to acquire access to these markets; and (3) held meetings with extension officers and local government to form formal farmers groups. As indicated above, follow-up design meetings were held after approximately 10 months supported by facilitators and an agricultural extension officer was invited to a meeting on specific request of farmers and the local traders.

The results of implementation activities and follow-up design are described below for value chain management in relation to production, market, logistics, finance and institutions.

Production

Farmers and local traders were mostly successful in implementing their plans and discovered limitations during the process (). The plans were then adapted (during the follow-up design meetings) based on their experience (during implementation activities) and new technical knowledge gained from interaction with an agricultural extension officer.

Table 4. Implementation of agreed solutions and actions plans, and follow-up plans with respect to production.

Market

With respect to the market, all groups pursued the option to supply produce to supermarkets. Initially, all groups were unsuccessful. Groups 1 and 2 pursued and were successful, while Group 3 did not pursue this any further. As of November 2018, Groups 1 and 2 are working with a supermarket supplier to supply produce to two supermarkets with a total of 11 outlets. Farmers are involved in post-harvest activities and have access to market informationFootnote5 that affected their awareness on produce quality and the implications for market value. In the follow-up design, Groups 1 and 2 have plans to increase their supply to supermarkets, while Group 3 is pursuing opportunities to expand their market.

shows how agreed solutions and action plans have been implemented, and the follow-up plans of all groups with respect to the market.

Table 5. Implementation of agreed solutions and action plans, and follow-up plans with respect to the market.

Logistics

With respect to logistics, farmers continue to work together to fix roads connecting their land. However, because most roads are not paved, they are easily damaged. For this, they came up with follow-up plans to pave the roads and to ask for support from the local government ().

Table 6. Implementation of agreed solutions and action plans, and follow-up plans with respect to logistics.

Finance

Little has changed for all three groups with respect to finance (). In the follow-up design, Group 3 agreed to try to acquire access to finance from the government. This requires the status of a formal farmer group (discussed in the next section).

Table 7. Implementation of agreed solutions and action plans, and follow-up plans with respect to finance.

Institutions

With respect to institutions, all groups pursued formalisation of their group. As of November 2019, Groups 1 and 2 have been registered in the database of the Ministry of Agriculture and have acquired a formal organisational structure. Meanwhile, due to regulationsFootnote6 farmers in Group 3 needed to re-join an established farmer group of coffee growers (of which they were previously members). Negotiations to this purpose were successful.Footnote7

Implementation of agreed solutions and action plans and follow-up plans with respect to institutions are shown in .

Table 8. Implementation of agreed solutions and action plans, and follow-up plans with respect to institutions.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper explores the potential of supporting agricultural chain actors in self-directed learning, through the COCREATE approach, to improve actors’ awareness of their own and each other’s situation, to work together to design and implement plans to deal with challenges in term of value chain management, extending initial results reported in (Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier Citation2019).

Experience with COCREATE in the cases of farmers and local traders in Indonesia shows the potential of SDL for agricultural extension programmes to facilitate to enable agricultural chain actors to work together to learn how to improve their value chain management by themselves supported by facilitators. From the cases, it can be seen that farmers and local traders were able to: (1) improve their common understanding of their chain situation that can be seen from the plans designed and agreed by them (in the first design activities); (2) work together to implement the agreed plans (in the implementation activities); and (3) evaluate the results and to adapt the solutions (in the follow-up design). In this approach, facilitators played roles in: (1) supporting farmers and local traders to follow COCREATE procedure and structure appropriately; (2) answering participants’ knowledge questions in terms of value chain management (including production questions) and involving experts when needed; (3) facilitating participants to access external parties (e.g. government, market, finance) when needed; and (4) encouraging participants to devise and implement their plans through periodic visits that correspond to the role of facilitators in SDL (Bosch, Mentz, and Goede Citation2019).

The effects of the COCREATE approach in supporting SDL activities in these cases are promising. It can be seen from the changes in roles and relationship between farmers and their local traders (in each group), especially in Group 1 and 2. Local traders in these two groups have become more aware of the farmers’ situations and farmers have become more aware of the challenges with which local traders are faced. Shifting the responsibility for post-harvest activities from the local traders to the farmers (that had never been done before in this area) for produce supplied to supermarkets required a major leap in faith from both parties, but it worked. Availability and transparency of market information from the supermarkets (price, volume order, post-harvest cost) increased awareness for both farmers and local traders, and provided the basis for discussions on daily practice: the choice of crops, planting date, desired quality, production techniques and possible governmental support. Shifting these tasks and responsibilities to the farmers was a direct consequence of the COCREATE approach, confirming the importance of awareness of value chain management for sustainable chains (Kusnandar, Brazier, and van Kooten Citation2019; Unnevehr Citation2015).

Meanwhile, the group that proceeded without the local trader (Group 3) struggled to implement solutions agreed in the design activities. However, in the follow-up design, they managed to reorganise their group (to be independent of the local trader) and to join an established group.

The need for additional technical knowledge (Benson and Jafry Citation2013) was also confirmed. All groups in this study discovered the need to form formal farmer groups to access technical knowledge from agricultural extension programmes and to access financial (governmental) programmes (e.g. production inputs subsidies, credit with low interest rate). The self-directed learning approach embraced within COCREATE, made it possible for facilitators to provide information when asked for.

Based on these results, implementing COCREATE demonstrates the need for new types of SDL in extension programmes. Initially intense, if the approach is implemented over time with farmers and local traders (and other chain actors), participants could be expected to become used to working with this approach requiring less-intense support from facilitators. Agricultural extension programmes (long established in Indonesia and other developing countries) can be extended to enable implementation of long-term COCREATE programmes. As the resources of agricultural extension programmes in Indonesia and other developing countries are limited, cooperation with local universities can be a promising strategy. Training for extension officers and others (people from local universities) is required to ensure COCREATE procedure is implemented appropriately. The other challenge of this approach is scalability. For this, ICT may well be able to provide a solution in the future. Further research is needed to explore these options.

Practical notes

COCREATE can be used by agricultural extension programmes to support farmers and other actors in the chain in a self-directed learning activities.

Implementation of COCREATE would require agricultural extension programmes to take a role as facilitator in self-directed learning activities in addition to providing specific courses on specific topics.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of Republic of Indonesia within the RISET-PRO programme. The field research was conducted within a collaboration between Systems Engineering Section, Department of Multi Actor Systems, Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management, Delft University of Technology, Netherlands and the Study Programme of Agribusiness, Faculty of Agriculture, Padjadjaran University, Indonesia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

K. Kusnandar

Kusnandar is a PhD candidate at Systems Engineering Section, Department of Multi Actors Systems, Faculty of Technology Policy and Management, TU-Delft, the Netherlands. He is also affiliated to the Research Centre for Science and Technology Development, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI). His current research focuses on empowering agricultural chain actors through participatory approach.

O. van Kooten

Olaf van Kooten is a professor emeritus at Horticulture and Product Physiology, Department of Plant Science, Wageningen University, the Netherlands. He is also affiliated to Inholland University of Applied Science. His current research focuses on new market strategies and chain partnerships in agricultural sector.

F. M. Brazier

Frances Brazier is a full professor within the Systems Engineering Section, Department of Multi-Actor Systems, Faculty of Technology Policy and Management, TU-Delft, the Netherlands. Her current research focuses on the design of participatory systems (www.participatorysystems.org), supporting self-organisation and emergence based on the values trust, empowerment and engagement.

Notes

1 Crops planted by farmers in all groups are diverse, e.g. watercress, tomatoes, beans, cabbage, chillies, leafy green vegetables.

2 The continuation of the initial design activities reported in Kusnandar, van Kooten, and Brazier (Citation2019).

3 Students from Unpad (a local university) supported by research assistants and lecturers from Unpad and TU-Delft.

4 Research assistants from Unpad.

5 The two local traders share information of price, volume order, post-harvest and transportation cost of produce supplied to supermarkets with the farmers.

6 Based on the rules, farmers who are registered in a formal farmer group cannot become a member of a new farmer group.

7 The head of coffee farmer group came to the follow-up design meeting invited by Group 3 and accepted the plans.

References

- Baloch, Mumtaz Ali, and Gopal Bahadur Thapa. 2019. “Review of the Agricultural Extension Modes and Services with the Focus to Balochistan, Pakistan.” Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences 18 (2): 188–194.

- Benson, Amanda, and Tahseen Jafry. 2013. “The State of Agricultural Extension: An Overview and New Caveats for the Future.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 19 (4): 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2013.808502.

- Bolhuis, Sanneke. 2003. “Towards Process-Oriented Teaching for Self-Directed Lifelong Learning: A Multidimensional Perspective.” Learning and Instruction 13 (3): 327–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(02)00008-7.

- Bosch, Chantelle, Elsa Mentz, and Roelien Goede. 2019. “Self-Directed Learning: A Conceptual Overview.” In Self-Directed Learning for the 21st Century: Implications for Higher Education, edited by Elsa Mentz, Josef de Beer, and Roxanne Bailey. Durbanville, South Africa: AOSIS (Pty) Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4102/aosis.2019.BK134.

- Fisher, Monica, Stein T Holden, Christian Thierfelder, and Samson P Katengeza. 2018. “Awareness and Adoption of Conservation Agriculture in Malawi: What Difference Can Farmer-to-Farmer Extension Make?” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 16(3): 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2018.1472411.

- Garrison, D Randy. 1992. “Critical Thinking and Self-Directed Learning in Adult Education: An Analysis of Responsibility and Control Issues.” Adult Education Quarterly 42 (3): 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171369204200302.

- Kelly, Nick, John McLean Bennett, and Ann Starasts. 2017. “Networked Learning for Agricultural Extension: A Framework for Analysis and Two Cases.” The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension 23 (5): 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2017.1331173.

- Kidd, Sean A, and Michael J Kral. 2005. “Practicing Participatory Action Research.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 52 (2): 187–195.

- Kiptot, Evelyne, and Steven Franzel. 2015. “Farmer-to-Farmer Extension: Opportunities for Enhancing Performance of Volunteer Farmer Trainers in Kenya.” Development in Practice 25 (4): 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2015.1029438.

- Knowles, Malcolm S. 1975. “Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers.”

- Kusnandar, K., F. M. Brazier, and O. van Kooten. 2019. “Empowering Change for Sustainable Agriculture: The Need for Participation.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 17: 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2019.1633899.

- Kusnandar, Kusnandar, O van Kooten, and F. M. Brazier. 2019. “Empowering through Reflection: Participatory Design of Change in Agricultural Chains in Indonesia by Local Stakeholders.” Cogent Food & Agriculture 5 (1): 1608685. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1608685.

- Munthali, Nyamwaya, Cees Leeuwis, Annemarie van Paassen, Rico Lie, Richard Asare, Ron van Lammeren, and Marc Schut. 2018. “Innovation Intermediation in a Digital Age: Comparing Public and Private New-ICT Platforms for Agricultural Extension in Ghana.” NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 86-87: 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2018.05.001.

- Natawidjaja, T Reardon, S Shetty, T Noor, T Perdana, E Rasmikayati, S Bachri, and R Hernandez. 2007. “Horticultural Producers and Supermarket Development in Indonesia.” World Bank Report No.38543-ID.

- Rocha, Jozimo Santos. 2017. Agricultural Extension, Technology Adoption and Household Food Security. Wageningen: Wageningen University.

- Scheba, Andreas. 2017. “Conservation Agriculture and Sustainable Development in Africa: Insights From Tanzania.” Natural Resources Forum 41, 209–219. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12123.

- Settle, William, Mohamed Soumare, Makhfousse Sarr, Mohamed Hama Garba, and Anne-Sophie Poisot. 2014. “Reducing Pesticide Risks to Farming Communities: Cotton Farmer Field Schools in Mali.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 369 (1639): 20120277. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0277.

- Subervie, Julie, and Isabelle Vagneron. 2013. “A Drop of Water in the Indian Ocean? The Impact of GlobalGap Certification on Lychee Farmers in Madagascar.” World Development 50 (April 2011): 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.05.002.

- Unnevehr, Laurian. 2015. “Food Safety in Developing Countries: Moving Beyond Exports.” Global Food Security 4: 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2014.12.001.

- Verma, Pranay, and Neena Sinha. 2018. “Integrating Perceived Economic Wellbeing to Technology Acceptance Model: The Case of Mobile Based Agricultural Extension Service.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 126: 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.08.013.

- Witteveen, Loes, Rico Lie, Margriet Goris, and Verina Ingram. 2017. “Design and Development of a Digital Farmer Field School. Experiences with a Digital Learning Environment for Cocoa Production and Certification in Sierra Leone.” Telematics and Informatics 34 (8): 1673–1684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2017.07.013.

- World Bank. 2010. Extension and Advisory Systems: Procedures for Assessing, Transforming, and Evaluating Extension Systems. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

- Yin, Robert K. 2003. Case Study Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications CA.

- Zoundji, Gerard C, Florent Okry, Simplice D Vodouhe, and Jeffery W Bentley. 2016. “The Distribution of Farmer Learning Videos: Lessons from Non-Conventional Dissemination Networks in Benin.” Cogent Food & Agriculture 2 (1): 1277838. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2016.1277838.