ABSTRACT

Understanding “what works” for capacity development support in an international development setting remains an important area for operational research. This mixed-methods study explored this topic within a global programme that supports civil society organisations in fifteen countries to secure the health and human rights of marginalised and underserved populations. Taking a complex adaptive systems approach, and seeking to understand the phenomena from the “receiver” perspective, the study found that the programme fostered the development of four interconnected domains of capacity through a reflexive, user-led approach. These capacity gains could be linked, although not causally, to important programmatic achievements for the programme’s focus populations.

Introduction

Capturing the nature and effects of capacity development is a complex task, particularly if the acquired capacity is expected to contribute to a process of social change and transformation. The understanding of how these processes unfold, and the attempt to identify links or pathways between capacity development interventions, acquired capacity, and social change is an evolving science (Brinkerhoff and Morgan Citation2010; Gruskin et al Citation2015). Previous approaches attempting to describe linear relationships have, more recently, been supplanted by more dynamic and complexity-oriented understandings of how capacity is acquired and embedded within the social systems and involves multiple interplays of actors and factors as the process unfolds (McEvoy, Brady, and Munck Citation2016; Vallejo and Wehn Citation2016). In the last decade, within the international development context, the “complex adaptive” view of capacity development has gained traction, with more and more development practitioners from the “Global North” adopting it as the basis for designing, providing and reflecting on their support to partners in the “Global South” (McEvoy, Brady, and Munck Citation2016). Different models and frameworks have emerged that take this complexity-oriented approach, sharing characteristics such as iteration, learning, flexibility, and non-linearity, with an explicit focus on the interactions between recipients of capacity development and their external environments (Pascual et al. Citation2013; Vallejo and Wehn Citation2016). In many respects, this complexity-oriented approach involves observing and interpreting links between capacity development and acquired capacity more than measuring and explaining these phenomena in terms of generalisable or replicable patterns. A pre-occupation remains, however, with “what works” and at least some degree of replication, given the emphasis on results and value-for-money among the agencies supporting North–South partnerships, and which have a genuine interest that tangible and durable capacity gains emerge at the Southern end of these investments.

For this study, which had a similar aim of identifying “what works”, the researchers adopted a study design that was guided by complex-adaptive systems (CAS) thinking, and incorporated methods that allowed for an endogenous approach. This approach involved observing and interpreting capacity development, capacity gains, and programmatic achievements from the perspective of those leading and experiencing these changes and within the specific contexts where these changes unfold. The study involved a global programme covering a wide variety of CSOs pursuing change objectives for specific focus populations in an equally diverse range of socio-political environments. This programme, called Bridging the Gaps, has been in existence since 2011 and is led by an Alliance of nine global NGOs and networks.Footnote1 It is one of very few global programmes focussing on the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of key populations, which include sex workers of all genders; people who use or inject drugs (PWUD); lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people (LGBT); and people living with HIV within each of these groups.Footnote2 The programme aims to contribute to ending the AIDS epidemic in these focus populations through achieving three long-term goals: a strengthened civil society that holds governments to account; increased fulfilment of human rights for key populations; and improved SRHR, including fewer HIV transmissions and AIDS-related deaths. Across three continents and fifteen countries, more than ninety CSOs work towards achieving these results in challenging environments characterised by an interplay of powerful interests that limit or deny the health and rights of their constituencies.

Given the central role of civil society partners in the programme, ensuring that these entities have sufficient capacity is an important priority. All Alliance members, most regional-level partners, and a number of the more established in-country partners provide capacity development interventions, using different modalities (e.g. training workshops, hands-on mentoring), for different target groups (staff of partner organisations, staff of programme subgrantees, programme stakeholders, and beneficiaries) and for different durations and levels of intensity (once-off events, longer-term, multi-year capacity development-focussed relationships). In order to understand in greater depth what these approaches achieved in relation to programme results, and whether they had any discernible degree of effectiveness, a multi-country operational research project was undertaken. Its aim was to identify those capacity development interventions that effectively equip CSOs and networks led by or working with key population groups to secure their health and rights, and to advocate for social change in complex legal and socio-cultural contexts. The study was carried out by a team of international and national researchers between April 2018 and July 2019 and its results are reported here.

Research approach

In the international development literature, the theoretical and practical approaches to capacity development have been continually evolving with no strong consensus on definitions or approaches (Backer Citation2000; OECD Citation2006; UNDP Citation2009). As a starting point, the research team chose to adopt the terminology of the OECD which has been applied to similar research efforts within a North–South frame. The OECD defines capacity as “the ability of people, organisations and societies as a whole to manage their affairs successfully” (OECD Citation2006, 12). It subsequently defines capacity development as, “the process whereby people, organisations and society as a whole unleash, strengthen, create, adapt and maintain capacity over time”. Capacity is used in these descriptions in its holistic sense as an aggregate of a number of sub-components that some scholars define as “an emergent combination” or “a complex interplay of attitudes, assets, resources, strategies and skills, both tangible and intangible” with “technical, organisational and social aspects” (Baser and Morgan Citation2008, 3, 23). The phrases “emergent combination” and “complex interplay” are important and suggest that what makes up capacity very much depends on the contexts where one is attempting to locate it, either from a research or practice standpoint (McEvoy, Brady, and Munck Citation2016). Following from this, and given the breadth of CSOs, operating contexts, programmatic objectives, and focus populations that comprise the programme, the researchers adopted a similarly “emergent” stance.

In the study, capacity development was further conceptualised as a process that strengthens existing capacities as opposed to building capacity where none existed previously (Ubels, Acquaye-Baddoo, and Fowler Citation2010). In this view, capacity develops from within individuals and organisations and occurs in a dynamic environment in which new knowledge and skills are offered, received, and subsequently integrated (or not) into the procedures and routines of individuals and organisations. Capacity development interventions can be characterised as learning processes, aimed at strengthening or improving the way in which individuals and organisations think and act, and acquired capacity as the outcome of this learning process. However, the ways in which such learning unfolds can be complex and challenging to trace or describe (Lavergne Citation2006). This suggests that any analysis of capacity development must seek to understand “the process of change from the perspective of those undergoing the change” as a priori or externally derived concepts or frameworks will not suffice (Baser and Morgan Citation2008). The researchers also took this endogenous view, meaning that, in relation to the research question, what was ultimately considered to “effectively equip” organisations to achieve social change was largely contingent on the views and experiences of the individuals and organisations engaged in these processes.

The research team designed a mixed-methods approach that included a core component of comparative case studies involving four Bridging the Gaps supported CSOs, each operating in different countries, with varying organisation structures, membership bodies, and focus populations.Footnote3 To undertake the case studies, the research team used outcome harvesting, a flexible investigative technique that is gaining in recognition in capacity development research using a CAS approach (Wilson-Grau and Britt Citation2012; McEvoy, Brady, and Munck Citation2016; Vallejo and Wehn Citation2016). This participatory technique unfolds in stages. It begins with the identification of significant results and then works retrospectively to collect the “evidence” of what is said to have been achieved in order to specify, substantiate, and validate the nature and extent of the results and the contributory factors leading to their realisation. In each case, the process began with participatory workshops involving staff members and researchers who identified significant programme results and then reflected on the contributory factors, including the role of capacity development. These elements were further investigated through document review, key informant interviews (including with individuals external to the organisation), and additional group discussions. The findings were then prepared as concise outcome statements describing the outcome itself and the contributions (on the part of the organisation itself, other partners or stakeholders, unforeseen influences or events, and capacity development support) that purportedly led to its achievement. In total, twenty-four detailed outcome statements were completed, across the four organisations, each having gone through several iterations and a final validation in a workshop setting.

Other data collection techniques in the study included a literature and document review, an electronic survey completed by sixty programme partners, and semi-structured interviews with fifteen key informants from the Alliance with an aim to review the current state of the art in capacity development within international development and human rights and health programmes, and to inventorise the capacity development theories, approaches, and interventions used across the Bridging the Gaps programme. The interviews and electronic survey also sought to examine the perspectives of both the Alliance members and their partners on the effectiveness of capacity development in the programme. The research team used the data that was collected through the survey to inform the selection of the four case studies. Given the range and quantity of data collected, the research team adopted different approaches for data analysis, interpretation, and validation. These included thematic analysis of documents, interview notes and transcripts, workshop reports and outcome statements, and descriptive analysis of survey data. For the case studies, the research team developed a coding structure, derived from the key concepts and research questions, for the analysis of the interview transcripts and as an interpretive guide for analysing documentation collected during the harvesting process. This approach helped to ensure the consistency of the analytic focus between the different researchers within and across the case studies. To link the results from these analytic approaches, the research team used triangulation. Analytic rigour was achieved through a continual, reflexive engagement with the data by the researchers, individually and jointly, and through the re-engagement of the research participants at different stages of the analysis process.

Approval to conduct the study was granted by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa. Approval was also granted through the Research Advisory Committee of Aidsfonds, who commissioned the research on behalf of the Alliance. Additional ethics clearances were obtained in Tajikistan and Nepal where two of the four case studies were conducted (in Uganda and Zimbabwe this was not required). Written informed consent was obtained prior to conducting key informant interviews. Consent to conduct the case studies was also provided by the governing body of each case study organisation.

Study findings

This section begins with some cross-cutting observations on the nature of capacity and capacity development in the Bridging the Gaps programme and the elaboration of a framework, that was informed by the programme’s goals and the research data, to help unpack and analyse capacity development within the context of this programme. The section then continues along the structure of this framework to present the study findings.

Situating capacity and capacity development within a social change agenda

The study began with an analysis of concepts and approaches to capacity and capacity development as understood by the leaders and participants in the programme, and as described in the capacity development materials that were collected. While these sources all demonstrated a strong commitment, what constituted the programme’s approach to capacity development, from both a conceptual and practical perspective, was neither consistently defined nor linked to an overarching strategy (a theory of change, for example). Nevertheless, across the interviews with the nine Alliance members a certain consistency was observed in the way capacity development was viewed as an iterative, continuous process which needed to centre around and leverage the role of the key population communities themselves, as described below:

The philosophy of a lot of funders is to believe now in “ready-organisations”. There is no such thing. They [organisations] can be great and powerful today, but crumble tomorrow. Capacity is something that is constant; you have to keep putting into it. For us it is really a focus on the bottom up approach. (Interview Alliance member)

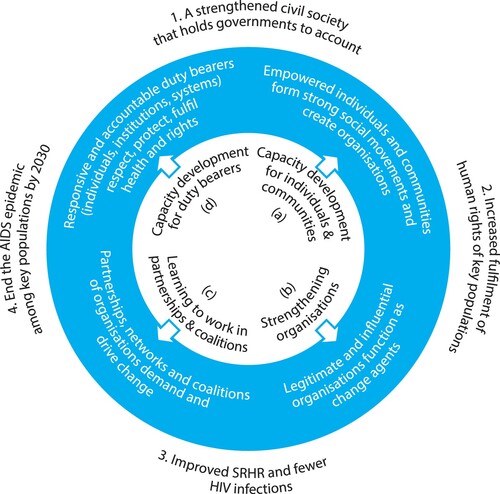

Capacity development for individuals and communities – This community development component of the Bridging the Gaps programme aims towards empowering individuals within their personal and social spheres to articulate and claim their identities and to form and sustain social movement structures in their communities.

Strengthening organisations – As a way to instrumentalise and direct the political power of social movements, empowered key population communities have formed organisations (or allies have formed organisations on their behalf). Governments or other types of “duty bearers” that affect the health and rights of key population groups operate through systems, processes, or institutional mechanisms that are most effectively accessed by organisations. It follows, then, that key population communities need strong organisations to act on their behalf (be legitimate, accountable, and influential) within the institutional and structural relationships that they are seeking to change and transform.

Learning to work in partnerships and coalitions – The change imperatives of the Bridging the Gaps programme are broad and multi-dimensional. They encompass not just institutional shifts in laws or policies, for example, but also shifts in socio-cultural attitudes, beliefs, or practices. There is no singular change imperative but a constellation of challenges that need to be resolved. Organisations as change agents need to combine forces to push against powerful forces in the form of governments or other social institutions that are indifferent or resistant to such shifts.

Capacity development for duty bearers – An important component of the Bridging the Gaps programme involves strengthening the capacity of duty bearers, whether as individuals (senior level politicians or decision makers), institutions (health ministries or police forces, for example), or systems (health services, for example) to be more responsive and accountable for the health and rights of key population groups. Through encounters with Bridging the Gaps-supported interventions, such as training or sensitisation workshops, or through advocacy interventions to affect laws, regulations, or policies, such duty bearers acquire desired capacities for change.

The four domains were not independent of each other and surfaced as emergent combinations that complemented each other according to local needs (). For example, it was personal empowerment that enabled members of the key population groups to sit in a parliamentary forum and give persuasive testimonies about their life experiences, in environments where aspects of their identities and behaviours are criminalised and socially condemned.

The following sections, based largely on the results of the outcome harvesting process, place in context the four identified domains, and help deepen their meaning and illuminate their practical application of “what works” and “how” for efforts to equip CSOs to demand and sustain social change.

Capacity development for individuals in communities

In pursuing social change, partner organisations placed considerable emphasis on the empowerment of members from key population groups to articulate their identities and to form and sustain social movement structures in their communities. These trajectories of community empowerment interventions consistently involve supporting individuals or groups to “step out of the shadows” in their personal and social spheres and to use their acquired capacities to alter their own life circumstances, including gaining control of their health and the factors that influence it. Across the four case studies, a range of approaches to foster personal and collective empowerment were observed. This included activities that reached out to socially isolated and highly vulnerable individuals through outreach workers or volunteers; that encouraged the formation of support groups or social networks in local communities; or that were made up of more elaborate mechanisms with broader scope, such as national or international meetings or conferences that brought constituencies together in larger numbers. Trainings, technical guides, outreach manuals, and other inputs provided by the Alliance members, including financial support, enabled organisations to undertake this work.

As an example, AFEW-Tajikistan, one of the case study organisations, put in place Key Population Councils as an intervention to empower and engage members of these constituencies. The councils played an active role in the monitoring, oversight, and accountability of programmes and services designed for their benefit. Initially, they were established to oversee the programmes and services of AFEW-Tajikistan. Over time, the councils’ role expanded to cover the work of other governmental and non-governmental actors, following the promotion of their work by AFEW-Tajikistan among these key stakeholders and a continued training and mentoring of these councils. Many of the individuals that became involved in the councils underwent some personal transformation through the skills and experiences they acquired, ranging from additional technical knowledge about the nature of organisations and service provision, to more personal achievements such as improved skills and confidence for social interaction. From the interviews with council members, there was a sense of these individuals moving from the margins to more central positions with an increased sense of authority and influence over what surrounded them, with a particular focus on the quality and legitimacy of programmes and services. One of the study respondents, involved in the hands-on guidance of the councils, described this change as follows:

They [key populations] considered themselves to be clients and persons who could only get some services but did not have the right to vote, or plan or evaluate … This is the uniqueness of creating the councils … which are not funded in any way. The model that we set out and implemented has worked, although at the beginning it was very difficult since the council members were constantly changing. But those who remained on board saw that their voice was heard and some steps were decided on. They watched, listened, wrote and sent letters […] and suddenly saw the significance of their voice. (Case study AFEW-Tajikistan: programme stakeholder interview I)

Empowering of key populations was very important, because the government now, for sure, 100%, they are inviting the key populations to discussions on planning, and for some strategic activities. This never happened 10 years ago, maybe five years ago, but now it is more and more common. (Case study AFEW-Tajikistan: programme stakeholder interview II)

Strengthening organisations

Key population communities require strong organisations to act on their behalf within the institutional and structural relationships that they are seeking to change and transform. The previous paragraph discussed different gradations in the involvement and leadership of these communities within partner organisations of the Bridging the Gaps programme. The researchers observed that, through cycles of experimentation, reflection, and learning, capacity was acquired, nurtured, and sustained as organisations evolved and strengthened their legitimacy and influence on the issues that were central to their mandates. As the programme has its most direct relationships with organisations, it was expected that a significant proportion of support would focus on organisational strengthening. The main areas involved programme management, financial management, resource mobilisation, and the strengthening of the technical quality of key population services. Modalities included online and offline training courses, on-site mentoring, exchange visits, provision of guidelines, tools and training manuals around specific topics, advocacy, and lobbying. Alliance members provided advice on partners’ internal systems for monitoring and evaluation, financial and human resource management, issues of governance and how to use research to generate an evidence-base for programming, and advocacy during monitoring visits and e-mail exchanges. A case study participant from GALZ described how Bridging the Gaps-supported trainings and events had strengthened organisational procedures and routines, in this way, meeting the broader objective of capacity development for the organisation as a whole:

I think they [Bridging the Gaps] have played a huge role, particularly supporting staff of our organisation in the capacity-building initiatives that they have […] MPact and COC would actually do the training and you would see that the staff were really benefitting from those initiatives because then they would come back and apply the techniques on the issues that they would have learned [to] their programming. And, in a way, it has influenced how or changed the way we are working internally because of that internally aided capacity. (Case study GALZ: staff member interview I)

Case study participants also identified risks and set-backs that could result in significant capacity losses. For example, WONETHA described how investments in recruitment, training, and mentoring of members as peer educators were lost when these members moved on, often to other organisations offering higher remunerations. And while there was an understanding of why one would look for other opportunities, there was nevertheless a frustration that the capacity investment had been lost for the organisation and that resources were not always available to conduct training for replacements. The study observed how the presence of financial pressures threatened capacity gains (loss of staff for example, when programme funding ended) and opened up critical capacity gaps when, for example, new programmes were undertaken which were more complex than any that partners had implemented previously. Risks also rose from the fragility of an organisation’s “license” to operate in a hostile context – particularly where key populations were criminalised – and government authorities sought to deregister and declare such CSOs illegal. The capacity to “read” and subsequently act on specific situations is developed through an extensive practice and a deep knowledge of the terrain by these health and human rights-oriented civil society partner organisations. Furthermore, it is this uncertainty or suddenness with which opportunities and threats for bringing about change arise that requires a certain amount of flexibility and trust within the funder–partner relationship and in the execution of their joint plans and goals for capacity development, which the Bridging the Gaps programme allowed for.

Learning to work in partnerships and coalitions

The researchers observed the breadth of change imperatives of the programme and how partner organisations worked on multiple health and rights dimensions, from institutional shifts through laws and policies, to shifts in socio-cultural attitudes, beliefs, and practices. There was no singular change imperative but a constellation of challenges that needed to be addressed and resolved. This complexity and breadth of the change agenda required partners to enter into strategic alliances and undertake collective action with like-minded organisations. It also required organisations to initiate and sustain functional relationships with partners that did not always share similar (or sometimes had opposing) goals or stances, such as governments, politicians, or police forces, but that were necessary for change. Depending on the level of partnership formalisation, there was a need for understanding the legal and social aspects of forming collaborative structures, and to develop communication or mediation skills to deal with any tensions arising from such arrangements.

In this domain, capacity development support consisted of promoting partner organisations’ connectivity at national, regional, and global levels. Opportunities were created for them to participate and interact with other organisations during conferences, in delegations and networking events. Across three of the four case study organisations, there was clear recognition of the need to embed themselves into local structures in order to effect change. All had seats on government committees and in technical working groups, whereby the nature of their work organically defined the different spaces they considered necessary to occupy. This was sometimes extensive; ranging from health governance structures, CSO networks, and multi-sectoral entities created under national HIV responses, to mechanisms for the oversight and channelling of international funding to their countries.

Although not a specific area of focus in the capacity development support of the programme, the ability to balance the politics and power dynamics and to foresee possible challenges emerged as an important set of skills from the study data. This included conflict resolution and risk management. As an illustration of the need for such capacity, GALZ (Zimbabwe) identified the establishment of an LGBT Sector Forum as a main outcome or result of their participation in the programme. The Forum unites LGBTI organisations within a self-organising platform through which to negotiate and consolidate their collective interest for greater influence, particularly within the national HIV response which has recently become more open to HIV-related LGBT health concerns. As GALZ itself explained:

I think there is strength in numbers and when we look at the sector, it doesn’t help when we are working in silos and if we are divided. We want to develop a common advocacy strategy that will apply to all organisations and that we will use as a reference in the work that we do to come up with common objectives and work towards that goal in our different organisations. (Case study GALZ: Staff interview II)

Capacity development for duty bearers

A last but equally important component of the programme involved strengthening the capacity of duty bearers to be more responsive to and accountable for the health and rights of key populations that fell within their institutional jurisdictions, such as a Ministry of Health or Home Affairs. Equipping partner organisations to be effective in this work, either as individuals, organisations, or through working in partnerships and coalitions, constituted the fourth domain of capacity development for the programme. There were two-way capacity gains through interactions with duty bearers: government entities, for example, gained knowledge and experience about key populations and their health and human rights challenges; meanwhile, key population representatives acquired skills for speaking out and influencing important State representatives and institutions. The following example succinctly illustrates the cumulative nature of the capacity to have influence over important duty-bearers:

Our government trusts this organisation … (Case study AFEW-Tajikistan: programme stakeholder interview III)

A component of WONETHA’s efforts to influence duty-bearers and the larger programme environment was to address harmful and discriminatory messaging about sex workers in local media, including the participation of the police in perpetuating this practice. WONETHA’s approach was to draw on the empowered capacity of its members and staff to participate in training and sensitisation interventions with police, the media, and other local stakeholders and duty-bearers. During these events, women shared their personal stories as sex workers and the negative impacts of public exposure on them and their families, following the use of discriminatory and harmful media stereotypes. The results of these capacity development interventions were noted by peer educators on the ground as well as by other civil society organisations working on human rights issues in Uganda:

Police used to invite the media whenever they would do sex workers’ raids. This has stopped ever since they were sensitised. (Case study WONETHA: peer-educator interview)

I think media attitudes and perceptions have changed. Some of the mainstream media houses are now reporting on the human rights violations that sex workers experience, particularly those perpetuated by police. (Case study WONETHA: programme stakeholder interview)

Drawing in duty bearers and developing their capacity with a view to making them more responsive as key actors in a social system that is discriminatory, even hostile to key populations, is a challenging endeavour. The researchers observed how, in a context of repressive legal environments, the four case study organisations carefully planned any encounter with or training for duty bearers. Strategic use was made of capacity development interventions to draw duty bearers into the programme and offer them something personal in return: new knowledge and skills. The example of Youth Vision is used as an illustration here, while similar situations were also seen in the other case studies, of how all these carefully crafted investments can rapidly be undone and undermine the achievement of the programme as a whole. There is limited control over external variables, such as these, but the existence of a reciprocal relationship with duty bearers was observed to form an important element in the risk mitigation strategies of partners.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assist an Alliance of global development actors in identifying effective capacity development strategies that would enable the CSOs participating in the programme to secure the health and human rights of key populations. These were individuals and groups largely from socially excluded populations living in complex and often hostile legal and socio-cultural contexts. Capacity was initially conceived in the realm of organisations acquiring, sustaining, and “unleashing” power, agency, and legitimacy in order to bring about structural change. As the research unfolded, a broader, more situated conceptualisation of capacity across four main domains became more relevant and useful for analysing the nature and extent of the change-oriented results of the programme. This suggested the idea of a well-capacitated sector that, through its collective power, agency, or legitimacy, can achieve structural change, inclusive of, but moving beyond, organisations alone. Capacity development interventions involved different forms of empowering actions, starting from individuals in communities and reaching as far as duty-bearers that manage or influence structural relations such that they either enable or impede the realisation of the sexual health and rights for the programme’s focus populations.

The research findings reinforce the situated nature of capacity and capacity development and how their meaning and what they achieve in terms of important development results can only be securely grasped through exploring experiences in particular contexts (Vallejo and Wehn Citation2016). The strong appeal of the CAS approach for this field of enquiry lies in its attention to how these phenomena move, influence, and are being influenced by the interactions between individuals, organisations, and the larger social system within which they unfold (McEvoy, Brady, and Munck Citation2016). Through this approach, the study was able to discern four domains that encapsulate, and to an important degree, organise what the critical capacities are in relation to the programme’s objectives. The utility of multiple domain conceptualisations to further unpack capacity in a given context is also reflected in the literature, such as through the five capabilities model (Morgan Citation2006) and the three-levels approach to capacity development support (UNDP Citation2009). Apart from using them for analytic purposes, they also offer opportunities to serve as an overarching frame or as parameters to guide and track capacity development strategies.

The study set out to identify effective capacity development strategies that lead to durable programmatic gains. This initially suggested a result-based orientation, something that is common to externally-funded development programmes where accountability and value-for-money are predominant concerns. The findings modified this approach by offering an alternative, more experientially influenced view of effectiveness (leaning towards Earl et al.’s (Citation2001) “improved rather than proved” effectiveness). What is important from the findings is not so much an objectively defined set of capacity development strategies that can produce effective results but rather a set of experiential learnings illustrating how some commonly employed capacity development strategies can contribute to organisational and social level achievements along various pathways which require retrospective analyses through techniques like outcomes harvesting.

The question of what encompasses “evidence” as we try and link capacity gains to programmatic results is as important for researchers involved in this field as for development practitioners. It requires, as programmes are being designed, some sense of direction on the anticipated capacity needs and pathway(s) for capacity development in view of programme results, especially if the programme brings together different global actors in one Alliance. If this is not in place, there is a risk of offering interventions that are not underpinned by a shared programme logic, adding further difficulties to locating their benefits in highly dynamic programme environments. Such articulation remains compatible with the emergent nature of learning within programmes seeking to drive social change as long as it avoids the reductionist approach of output driven support. There will inevitably be a tension for programmes like Bridging the Gaps between flexible approaches to capacity development that allow for endogenous and emergent learning while, at the same time, being required by funders to measure and document some form of result. The approach of working with broader parameters or domains, and allowing partner organisations to define and track their own process of learning and achieving significant change may be one way to manage such tension.

Across the different data sources, some discernible results could be observed in the health, social, and legal environments of the focus populations, even if the connections between capacity development support, achieved capacity, and these important programmatic results could not be firmly established. Several results were described in this paper, for example, how the stronger capacity of key population members led them to initiate and sustain positive change for themselves as well as collectively, and drew the attention of policy makers. With regard to practice-oriented findings, experiences of the case study organisations suggest the following approaches to capacity development that fit well within a flexible approach. All of them have been identified elsewhere in similar research on capacity development support in complex contexts:

Use of an interactive approach to capacity assessment leading to user-defined and “owned” priorities for capacity development support. Capacity development is most effective when it builds on what exists and when it is owned and led by those seeking to improve their capacity (see also Pearson Citation2011; Ika and Donnelly Citation2017).

A co-learning, risk-sharing approach to capacity development, innovation, and change. Organisational development trajectories that cover the full range of organisational needs and extend over a longer period of time, with allowance for emergent needs, achieve greater gains in capacity development. So too do relationships between organisations and their technical partners and funders that are built on mutual support, risk-sharing and co-learning (see also Girgis Citation2007; De Grauwe Citation2009; Datta, Shaxson, and Pellini Citation2012).

Use of peer-to-peer learning and exchange mechanisms. This is a widely used approach whereby individuals and organisations are encouraged to actively support each other’s learning processes, undertake joint problem solving, and mentor one another, all within a context of explicitly or implicitly understood shared experience and identity (see also Pearson Citation2011; Thol et al. Citation2012; Sadhu et al. Citation2014).

Limitations

The study encountered several limitations. One pertained to outcome harvesting which relies on people’s readiness to reflect on both positive and negative aspects of capacity or performance and on the outcomes substantiation by people external to the organisation who are not necessarily privy to how acquired capacity was unleashed to accomplish programmatic results. Hence, substantiation relied primarily on the evidence generated from the case study organisations and their funding partner(s), which affects study validity. We employed several strategies to mitigate for this, such as applying mixed methods, deep probing, and creation of a non-threatening environment (e.g. focus groups without senior management) to elicit responses.

For the substantiation different types of data were collected and analysed, including programme documents containing evidence relevant to the outcomes. In a number of instances, written documentation was difficult to obtain and led to a potential over-reliance on verbal accounts through key informant interviews whereby some claims proved difficult to independently verify.

The case study and survey components spanned several global regions and numerous countries. The research team worked in English and relied on translations of interviews and document summaries from Buganda, Nepalese, and Russian. As a result, context and nuance may have been lost. We tried to mitigate against this by building in reflexive cycles in the data analysis and interpretation in each of the case study teams in which both the local researchers and implicated staff members mastered these languages and were well embedded in the research context

Lastly, the research findings described in this paper are to a large extent based on four organisational case studies, which limit the generalisability of the research beyond these particular contexts. However, across the cases some common trends and patterns emerged which could support learning in other organisational and country contexts.

Conclusion

The study has offered a comprehensive analysis of capacity and capacity development in the context of a unique global programme that supports a broad diversity of populations, organisations, and interventions. It has also illustrated how a longer-term partnership of trust, shared learning and risk-taking was an important enabler for organisational growth and for the achievement of the programme’s goal of securing the health and rights of key populations within complex country contexts. It is clear that capacity development in pursuit of social change is a complex area of research in which different methodologies have been tried and tested to trace change processes that are partly inimical to the gaze of the researcher. The important conceptual debates around this topic will continue, and will become richer to the extent that they can draw on experiential studies such as this one which attempt to examine and situate the theoretical complexities within rich descriptions of how capacity development unfolds in global programmes. The study makes a contribution to grounding the larger research enterprise while also being of practical value to development practitioners by highlighting good practices from the field.

Acknowledgements

The research was made possible through the participation and support of the Bridging the Gaps Alliance members and their partner organisations. HEARD acknowledges the support and guidance of the reference group members to the study, notably Ellen Eiling, Pedro Garcia, Anke Groot, Marie Ricardo, Esther Vonk, and Janine Wildschut. HEARD also acknowledges the important contributions of the in-country researchers Nigora Abidjanova, Maheshwar Ghimire, Rosemary Kabugo, and Nelson Muparamoto, and the staff focal points Zarina Davlyatova, Naomi Mujuni, Sylvester Nyamatendedza, and Rajendra Thapa to the study. HEARD is grateful for the participation and commitment of the staff, volunteers, programme beneficiaries, and partners of Gays and Lesbians Zimbabwe, Women’s Organisational Network for Human Rights Advocacy (Uganda), AFEW-Tajikistan, and Youth Vision (Nepal) to the case studies. Their contribution to the depth and relevance of the research was invaluable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carolien Jeanette Aantjes

Carolien Jeanette Aantjes is a research fellow with HEARD at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal in South Africa. Her research focuses on the sexual and reproductive health and rights of adolescent and young key populations, and the access to safe abortion care and other reproductive services for adolescent girls and women.

Dave Burrows

Dave Burrows is a Director of APMG and is based in Sydney, Australia. He has worked as a technical specialist on HIV programmes across the globe since 1987, and with a focus on people who use drugs.

Russell Armstrong

Russell Armstrong is a senior research officer with HEARD at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal in South Africa, focusing on financing and sustainability planning for national HIV responses, capacity development for recipients of Global Fund grants, and policy and programme development for sexual and reproductive health programmes for sexual minorities.

Notes

1 The Alliance members are the Aidsfonds, AFEW International, Federation of Dutch Associations for the Integration of Homosexuality (COC), Mainline, the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+) (all based in the Netherlands), the International Network of People who Use Drugs (INPUD), the Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP) (both UK-based), the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition (ITPC) (based in Botswana), and MPact (US-based). Country and regional partners in the programme are based in Kenya, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Indonesia, South Africa, Tanzania, Vietnam, Zimbabwe, Tajikistan, Mozambique, Myanmar, Uganda, Botswana, Nepal, and Georgia. More details about the programme are available at: https://hivgaps.org.

2 For additional details, see: https://www.unaids.org/en/topic/key-populations.

3 The selection of case studies was drawn from a larger sample of 60 organisations, which submitted preliminary information on capacity support through an electronic survey. Selection criteria included considerations of geographic location (representative of the different global regions of the programme), organisational structures and focus populations (representative of the variety of CSO partners and of the focus populations in the programme), and having sufficient history with the programme to support outcome harvesting and to generate a robust case study. The final selection included AFEW-Tajikistan, a social service organisation based in Dushanbe operating a sexual health programme for key population groups; Gays and Lesbians Zimbabwe (GALZ), a membership-led national organisation based in Harare operating programmes for the LGBT community; Youth Vision (Nepal), a national social service organisation operating in Kathmandu with a harm reduction programme for PWUD; and the Women’s Organisational Network for Human Rights Advocacy (WONETHA) (Uganda), a national sex-worker-led organisation based in Kampala supporting community-led interventions for sexual health promotion.

References

- Aidsfonds. 2015. Bridging the Gaps Alliance. Phase 2 programme document November 2015. Amsterdam: Aidsfonds.

- Backer, T. E. 2000. Strengthening Non-Profits: Capacity-Building and Philanthropy. Encino, CA: Human Interaction Research Institute.

- Baser, H., and P. J. Morgan. 2008. Study on Capacity, Change and Performance. Maastricht: European Centre for Development Policy Management Discussion Paper.

- Brinkerhoff, D. W., and P. J. Morgan. 2010. “Capacity and Capacity Development: Coping with Complexity.” Public Administration and Development: The International Journal of Management Research and Practice 30 (1): 2–10.

- Datta, A., L. Shaxson, and A. Pellini. 2012. Capacity, Complexity and Consulting. Lessons from Managing Capacity Development Projects. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- De Grauwe, A. 2009. Without Capacity, There is no Development. Paris: UNESCO, International Institute for Educational Planning.

- Earl, S., F. Carden, M. Q. Patton, and T. Smutylo. 2001. Outcome Mapping: Building Learning and Reflection into Development Programmes. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

- Girgis, M. 2007. “The Capacity-Building Paradox: Using Friendship to Build Capacity in the South.” Development in Practice 17 (3): 353–366.

- Gruskin, S., E. Waller, K. Safreed-Harmon, T. Ezer, J. Cohen, A. Gathumbi, & P. Kameri-Mbote. 2015. Integrating human rights in program evaluation: Lessons from law and health programs in Kenya. New Directions for Evaluation (146): 57–69.

- Ika, L. A., and J. Donnelly. 2017. “Success Conditions for International Development Capacity Building Projects.” International Journal of Project Management 35 (1): 44–63.

- Lavergne, R. 2006. Addressing the Paris Declaration: Collective Responsibility for Capacity Development, Learning Network on Capacity Development – Forum 17 Berlin.

- McEvoy, P., M. Brady, and R. Munck. 2016. “Capacity Development Through International Projects: A Complex Adaptive Systems Perspective.” International Journal of Managing Projects in Business. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-08-2015-0072.

- Morgan, P. J. 2006. The Concept of Capacity. Maastricht: European Centre for Development Policy Management Discussion Paper.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2006. The Challenge of Capacity Development. Working Towards Good Practice. DAC Guidelines and Reference Series. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Pascual, S., M. Siemen Veenstra, U. Wehn de Montalvo, R. Tulder, and G. Alaerts. 2013. “What Counts as ‘Results’ in Capacity Development Partnerships Between Water Operators? A Multi-Path Approach Toward Accountability, Adaptation and Learning.” Water Policy 15 (S2): 242–266.

- Pearson, J. 2011. Training and Beyond: Seeking Better Practices for Capacity Development. OECD Working Papers. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Sadhu, S., A. R. Manukonda, A. R. Yeruva, S. K. Patel, and N. Saggurti. 2014. “Role of a Community-to-Community Learning Strategy in the Institutionalization of Community Mobilization Among Female Sex Workers in India.” PLoS One 9 (3): e90592.

- Thol, P., S. Chankiriroth, D. Barbian, and G. Storer. 2012. “Learning for Capacity Development: A Holistic Approach to Sustained Organisational Change.” Development in Practice 22 (7): 909–920.

- Ubels, J., N. A. Acquaye-Baddoo, and A. Fowler. 2010. Capacity Development in Practice. London: Earthscan.

- UNDP. 2009. Capacity Development: A UNDP Primer. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- Vallejo, B., and U. Wehn. 2016. “Capacity Development Evaluation: The Challenge of the Results Agenda and Measuring Return on Investment in the Global South.” World Development 79: 1–13.

- Wilson-Grau, R., and H. Britt. 2012. Outcome Harvesting. Cairo: Ford Foundation.