ABSTRACT

Through a sensemaking lens, this article investigates the concrete appropriation of the so-called transdisciplinary learning communities-approach (TLC for short) as part of a Flemish–Bolivian university cooperation project for development. The article has its empirical basis in ethnographic research conducted between 2017 and 2020 on four campuses of the Bolivian university UCB. The primary data is the so-called organisational talk, gathered through interviews, participant observations, and meetings with Bolivian university staff members who are the main players involved in the Flemish–Bolivian university cooperation project. The analysis suggests that an informal, horizontal, and symmetrical style of organisational communication between organisational members seems to have a positive impact on the appropriation of TLC, which in turn leads to more successful experiences of cooperation with communities and other external partners in the social environment.

Introduction

One of the main challenges of university cooperation for development remains to produce knowledge with and for local communities that is implementable in practice (Dewulf, Craps, and Bouwen Citation2005). Action and community-based methodologies are often considered the most suitable for this, as they conceive development as a joint learning process in which expert knowledge is integrated with lived expertise (Anyidoho Citation2010; Blanes Citation2018; Lozoya-Santos et al. Citation2019). However, the introduction of these methodologies in an academic context can bring numerous questions and meet low levels of acceptance, especially in contexts such as the Latin American, where universities occupy a dominant position in knowledge production and where the universities themselves are characterised by vertical organisational culture and traditional power hierarchies (Beigel Citation2013; Craps Citation2019; Lozoya-Santos et al. Citation2019).

Against this backdrop, we investigate through a sensemaking lens the concrete appropriation of the so-called transdisciplinary learning communities approach as part of a Flemish–Bolivian university cooperation project for development in the context of the Institutional University Cooperation program (IUC for short). As one example of action and community-based methodologies, transdisciplinary learning communities (TLC for short) aims to stimulate cooperation at different levels and in various fields to solve complex and challenging problems. Hence, collaboration and knowledge sharing between universities and local community stakeholders, academic and non-academic partners, and different academic disciplines are all geared towards mutual learning and development (Lozoya-Santos et al. Citation2019; Craps Citation2019; Jansen Citation2020).

Consistent with the sensemaking approach, we argue that a fine-grained understanding of how organisational members give sense to reform in their organisation is crucial to explain the varying level and speed at which this change initiative is appropriated. The general research questions guiding the study are framed as follows: How does TLC come to mean what it means? What sensemaking processes characterise the appropriation of TLC? The article has its empirical basis in ethnographic research conducted between 2017 and 2020 on four campuses of the Universidad Católica Boliviana San Pablo (UCB for short). The primary data is the so-called organisational talk (Ford and Ford Citation1995; Thurlow and Helms Mills Citation2009), gathered through interviews, documents, participant observations, and meetings with Bolivian university staff members who are the main players involved in the IUC program, a Flemish–Bolivian university cooperation project.

The article sets out with a brief discussion of sensemaking theory that serves as the analytical framework for the research. The second section is concerned with the background of the study, followed by a description of the data gathering and analysis. The third section discusses the particularities of the sensemaking processes for the four university campuses. In the fourth section, we attempt to identify more general patterns in the relation between sensemaking and appropriation of TLC, and to present programmatically, although with some caution given the context-specificity of our study, some signposts for the implementation of TLC as part of university cooperation projects for development.

Sensemaking theory and organisational change

Although the concept of sensemaking has its origins in symbolic interactionism, social phenomenology, and hermeneutics, it is thanks to Weick (Citation1995; Citation2005) that it has become widely accepted in organisation studies. The central premise of his sensemaking theory is that in order to comprehend how an organisation grapples with events that change or interrupt its routine understandings and practices, processes of sensemaking among its members are an important entry point.

Weick’s (Citation1995) analytical framework for understanding and reconstructing processes of organisational sensemaking points to seven so-called sensemaking properties that researchers can use in a manner of sensitising concepts, suggesting directions along which to look, and giving a general sense of reference and guidance in approaching sensemaking processes: identity construction, retrospection, extracted cues, plausibility, enactment, social orientation, and ongoing process. The interrelatedness of these properties is vital to sensemaking research (Helms Mills, Thurlow, and Mills Citation2010), as explained in the next paragraph.

When people try to make sense of organisational change they tend to rely on what is familiar and plausible to them by associating it with information stored in their reservoir of knowledge and experience, in relation to identity standpoints as a member of a profession, social group, community, organisation, etc. Sensemaking starts with the individual’s ability to interpret and rationalise cues, such as specific events or activities, that call the individual’s attention and are used as points of reference against which the individual makes sense of change. At the same time, it is an inherently social activity and collective process, based on symbolic interactions with others with whom one can agree or disagree. Sensemaking always occurs in a retrospective way: interrupting events are understood after they have occurred, when people process them in various forms of organisational talk. It is here that we can observe the enactment of sensemaking processes that has a generative effect on social environments, which in turn are used to extract cues for sensemaking. The ongoing character of sensemaking processes, with no clear beginning nor end, which means it cannot be pinned down at one disrupting moment, contributes to both social reproduction/continuity and social change/discontinuity (Weick Citation1995).

In the field of organisational studies, this analytical framework has been invoked to understand how organisational members, both in the public and the private sector, make sense of a new policy, reform, organisational restructuring, etc. for the purpose of identifying and explaining the reasons, conditions, and criteria underpinning why change and innovation fail to or become accepted (Thurlow and Helms Mills Citation2009; Louis, Febey, and Schroeder Citation2005; Baly, Kletz, and Sardas Citation2016; Ito and Inohara Citation2015; Maitlis and Sonenshein Citation2010). In the more critically oriented sensemaking field, the effects of institutional context, social conflict, and structural power imbalances on sensemaking processes receive particular and explicit attention. While this approach builds on Weick’s analytical framework, it is more attentive to the ideological aspects of language, competing narratives of change, and power imbalances within organisations and wider society (Weber and Glynn Citation2006; Maitlis Citation2005; Helms Mills, Thurlow, and Mills Citation2010; Thurlow and Helms Mills Citation2009). For university contexts in particular, this field has revealed that the tradition-bound character of universities and conservative power hierarchies in academic communities are an important factor that can slow down the implementation of reform or innovation (Moilanen, Montonen, and Eriksson Citation2018; Gioia, Thomas, Clark and Chittipeddi Citation1994).

Background of the study

The IUC program with UCB was launched in 2017 by four Flemish universities for a term of ten years and is supervised by a Flemish and Bolivian national coordinator. It is publicly funded by the VLIR-UOS, a Flemish governmental agency that supports partnerships between universities and university colleges in Flanders (Belgium) and the Global South. With one of the highest rates of extreme poverty in Latin America, despite notable advances in the last decade (CEPAL Citation2019), Bolivia is seen as a priority country for Flemish development projects. With the first term running from 2017 to 2021 and the second from 2022 to 2026, the program aims to put TLC teams into action at each campus to focus on the following priorities: social vulnerability (mainly related with children rights and gender equality), water management, food sovereignty, indigenous rights, and productive development.

The main objective of IUC is to improve the living conditions of vulnerable Bolivian communities by collaborating with four regional university campuses in Cochabamba, La Paz, Santa Cruz, and Tarija. For the Flemish promotors and funders of the program TLC is considered the lynchpin of IUC and presented as a promising methodology on the IUC Bolivia official website:

Transdisciplinary Learning Communities are dynamic spaces, composed of academics, leaders and members of the community and civil society organizations. The TLCs work together in different stages of a research project: in the formulation of the complex local question to be answered, in the methodological decisions (how to collect information) and in the socialization of the knowledge generated. The TLCs are spaces for interaction where disciplinary boundaries merge, meet and generate new knowledge to propose improvements in intervention plans, in the formulation of protocols and local public policies that benefit the quality of life of local communities.

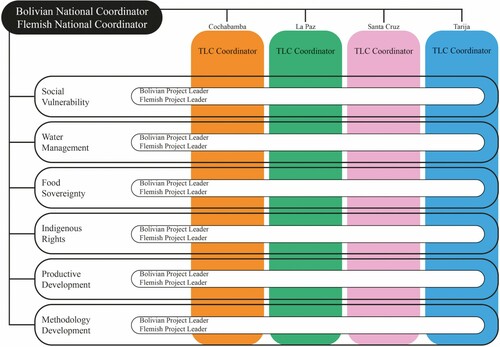

From an organisational point of view, the program’s objectives are reflected in a matrix model that is structured along two axes (see ). The horizontal axis concerns the project logic, resulting in six thematic project teams that are led by both a Bolivian and a Flemish university staff member (referred to as project leaders) and working on the priorities mentioned above and the implementation of the TLC methodology across the four regions. The vertical axis pertains to the TLC approach, resulting in four TLC teams, each based on a different regional university campus. Led by a Bolivian university staff member (referred to as the TLC coordinator), the TLC teams aim for intra-regional cooperation across academic disciplines and with various stakeholders (e.g. NGOs, public services, community actors such as indigenous people, community leaders, etc.). All Bolivian university staff members involved are part of one thematic project team and are expected to carry out activities with respect to the identified research priorities. Most of them are also part of one TLC team and are required to collaborate with colleagues from other disciplines in supporting local communities. As a result, the Bolivian university staff members often report to two or more supervisors (the project leader, the TLC coordinator and the national coordinator) next to their fellow colleagues in the teams.

Data gathering and analysis

Given the personal involvement of the three authors in the roll-out of the IUC program, we were able to witness from an ethnographic insider perspective how the introduction of the TLC approach was perceived as an interruption, marking a distinction with the university’s organisational structure and its working culture. As argued by Gioia, Thomas, Clark, and Chittipeddi (Citation1994), this offers the advantage of following sensemaking processes of organisational change very closely. As a Bolivian member of the methodological project team and the TLC team of La Paz, the first author took on a participant-observer’s role. As Flemish project leader and national coordinator, the third and fourth author also observed the sensemaking process from an insider perspective, while participating in meetings, research activities and visits on site. The second author had no participation in the IUC program. She has been only indirectly involved in the program, and attended only one meeting with a delegation of Bolivian and Flemish team members in Brussels. The role of this author might in ethnographic terms be described as that of an outsider, guaranteeing therefore a more “naive” perspective, whilst challenging the co-authors to make explicit their tacit knowledge and assumptions they take for granted as members of the IUC program (cf. Agar Citation2010; Hammersley and Atkinson Citation2019).

The relatively extended engagement in the field allowed us to examine the retrospective and ongoing character of sensemaking from an abductive approach. This consists of moving back and forth between the multiple sources of data, between data and theory, and between data collection and data analysis in order to “describe and understand social life in terms of social actors, meanings, and motives” (Blaikie Citation2009, 84). In the present study, the structure of understanding the organisational sensemaking processes of TLC was circular, involving several rounds of data gathering and analysis (see Appendix 1).

Between 2017 and 2020, we triangulated multiple methods of data gathering and combined various sources of organisational talk (see Appendix 2): (1) participant observation of regular meetings, three national meetings and four national workshops in the form of field notes; (2) seven group discussions with the TLC teams; (3) four semi-structured interviews with academic authorities; (4) four meetings with both academic-decision makers and TLC team members; and (5) a complementary document analysis of the IUC proposal and three TLC reports. All interviews were recorded and transcribed. After each participant observation, the field notes would be re-organised in detail.

Data analysis comprised four main stages. We started with analysing the verbal data as types of discourse and language, narrative and account, and patterns of social interactions. We then constructed concepts and categories in order to grasp the process of sensemaking. In this step, we were sensitive to how social and institutional contexts shape individual sensemaking practices by providing resources, allowing room for agency, and imposing constraints. In our study, this was achieved by paying attention to the organisational culture and management of the four university campuses, their mutual relationship, their embedment in the IUC program, their grounding in the region, and their experiences with community stakeholders. Thirdly, we triangulated findings from previous rounds with new observations. Fourthly, we shared our preliminary findings with the TLC team members and invited them to assess our analysis as a means of member validation (Seale Citation2004). The feedback and input we received was used to refine the analysis and to triangulate the data once more.

Results

With a strong support for the TLC approach, one of the first objectives of the Flemish promoters and funders of the IUC program at its start in 2017 was to set up the four TLC teams as quickly as possible. In these relatively pressurised conditions, it became clear that there was a lot of ambiguity about the concrete elaboration, let alone the fundamentals, of this approach. Although the TLC approach was presented in the proposal text of the IUC program and in the plenary kick-off meeting of the program in La Paz in 2017, the members of the four TLC teams working on different campuses in very different regions gave very different explanations of how such a TLC should be put into practice.

These observations triggered our investigation and motivated us to uncover the different sensemaking processes that accompanied the appropriation of TLC and the new organisational realities associated with it. We argue that in order to understand the differences between the four campuses, a context-sensitive approach to organisational sensemaking processes is vital. For that reason, we first present the four university campuses as separate cases and reconstruct the distinct dynamics at play, hereby sometimes using the organisation members’ own words (in italics).

Cochabamba

The TLC team of Cochabamba got off the starting blocks right after the start of the IUC program. From the onset it was well-staffed with approximately 10 members, of both senior and junior status, who knew by the end of the first year they wanted to work with local communities in the rural area of Tiraque. The rather successful launch, however, came under substantial pressure in year two, when alignment among its members started to break.

The lack of and the resulting need for more horizontal communication within the TLC team emerged as one of the key elements in the accounts of the organisation members concerned. This was seen as the main reason for substantial disagreement within the team over its functioning and plan of action. It was clear that the change of TLC coordinator and style of leadership in year two had effects on leader–member and member–member communication. This resulted in complaints from motivated members, who pointed out that there was a wide gap between the “very willing” colleagues, emphasising the importance of “engagement”, “roles”, and “shared expectations”, versus the uncommitted and rather absent team members.

Since the campus management was very much in favour of the IUC program and the regional authorities had already in year one become aware of the objectives of the TLC team, some of the committed TLC team members had expressed their wish for a more top-down implementation of TLC, advocating “authority”, “formality”, and “coercion”. In this specific institutional context, the sensegiving role of leaders seemed to be the crux to encourage a successful continuation of TLC. However, in synchronising their own demand for “sincere” interactions, “true” dialogue, and open internal communication with the needs for the TLC functioning, the internal struggles and tensions within the TLC team were discussed and pacified via open dialogue that was supported by the campus management. Furthermore, the return of the first TLC coordinator in year three was perceived as a good step towards building “synergy”.

As noted earlier, the decision to work with stakeholders in Tiraque had already been taken by the end of year one. Building on previous project experiences in this area, weekly meetings with NGOs and fieldworkers, and some visits to the wider region of Cochabamba, the TLC team had been able to determine the priority areas relatively quickly. In year two, however, academic staff members noticed distrust of the inhabitants of Tiraque, which they attributed to previous “paternalist” development programs. This experience and, more importantly, how they rationalised it in their talk, was a good example of retrospective sensemaking, which reinforced the importance they attributed to symmetrical communication, horizontal leadership, and “coordination”. Hence, in year two, a large workshop with the people of Tiraque was organised, during which local inhabitants expressed their interest in research and training related to other topics than the ones the program had prioritised. By year three, the TLC team had decided to interact more intensively with the communities, leading to a considerable “opening of the community”.

La Paz

As the oldest, and historically, leading campus of UCB, the La Paz campus hosts the national rector of the university, the central offices of the university administration, and the national research centres. For that reason, this university campus has played a very important role in the development and organisation of the IUC program. This is, for example, clearly demonstrated by the involvement of the heads of the national research centres in preparing the proposal. Also, at the start of the program all six project leaders were based in La Paz. Currently, one of the national research centres leads the program, and its director is also the national coordinator. However, strong involvement in the conceptualisation of the research program proved not to be a guarantee for efficacious appropriation of TLC.

The team was well-staffed with 15 members, six of whom also took up the role of project leader and controlled the sensemaking processes in the TLC team, each with the logic of their own project. From the start, the interviews and observations showed that the meetings were dominated by “the leaders”, and the discussions were related to the thematic projects rather than the practical implementation of TLC. This generated frustration, especially among the junior researchers, demanding in year two more “autonomy” from the project leaders, who were all of senior status. As an act of defiance, the junior members even created for a short time a separate TLC team, against the wish of the project leader-members, in order to build a space where they could conceptualise TLC in a more horizontal and open manner.

This decision was a testament to the perceptions of what TLC “should be”. Tensions between the project leader-members and the others did not ease, as the former claimed they were part of the TLC team and wished to remain involved in all meetings pertaining to TLC. Hence, the frequency of the meetings and the relationships within the team were severely compromised, with substantial disagreement about priority areas, the roles of the project leaders, communication, etc., resulting in three staff changes at the TLC coordination level. The over-representation of La Paz in leadership roles also caused tensions with the other campuses, that complained about “centralism” in decision-making.

Despite La Paz’ cockpit role in the program, the university authorities themselves did not claim project ownership. One management staff member metaphorically described the relation between the IUC program and the campus as follows: “(The program is) not the fifth wheel of the car (but) rather a Mercedes Benz in itself that has these resources”. Coming with large funds, the program was perceived as a sovereign unit in itself, disengaged from the rest of the campus, and with a clear lack of active, external communication. While some senior TLC members acknowledged this problem, others expected the university management to be more “syntonized” in the program’s progress, rather than the other way around.

Hierarchical communication problems with controlling project leaders and a disconnected university management seemed to be the cues the junior team members pointed at in explaining and criticising La Paz’s indecisiveness about which areas and community stakeholders to involve. The “radical progress” by the end of year three, when the Altiplano region was finally chosen as the priority area, was the result of organisational changes in the IUC program and the TLC team. The monopoly of La Paz in the project teams was opened up by appointing two leaders from other regions. One of the senior members of the TLC team was appointed as the new national coordinator of the IUC program. While applying a more horizontal style of leadership and drawing on her formal authority to organise more frequent meetings in which issues were openly discussed, the pressure to get off the starting blocks gave an important impetus, especially given La Paz’s leading role in IUC and UCB.

Santa Cruz

From the very start, the TLC team of Santa Cruz has been characterised by solid, collaborative, and horizontal leadership. Unlike the other TLC teams, it has been led by the same coordinator all the time with five members. In preparation for the fieldwork in San José de Chiquitos, the team had consulted NGO workers and adopted from one of them a philosophy of working which they referred to as the “paradigm of taking care”. Based on this, the coordinator developed an overall strategy with the team, with clear concepts and values about how to take care of others in terms of spending time, showing mutual interest, creating personal spaces, and encouraging interactions among all participants involved.

As a result, Santa Cruz enacted a shared and transparent sense of TLC, in the words of the coordinator, as “a space where you involve actors, who are willing to be part and who have a common agenda to work together; where we all have the same levels of participation, without letting academia, NGOs or civil society to absorb it”. The articulate and explicit sensemaking practices clearly transpired in the organisation members’ accounts, in which they described their team as “a cell” and as “part of something much bigger”, demonstrating a great sense of involvement to solve complex and challenging problems.

Since this sensemaking process was also consolidated at the institutional level at the very outset, with the regional rector showing strong commitment to the program and the TLC approach, the whole TLC team participated actively in the fieldwork. Much effort was devoted to building relationships of trust, respect, and common understanding through open forums and follow-up communication via messaging apps. This intensive and symmetrical communication process also allowed for serendipity, such as identifying priority communities, which had not thought of beforehand. Organisation members described this as a socially rewarding aspect of TLC, even if it required flexibility on their part. All this indicated that the academic staff members of the Santa Cruz team embraced TLC as an opportunity to collectively construct an organisational identity in terms of community engaged and participatory action research.

Tarija

Being the last TLC team to start off, as well as the smallest and geographically most isolated campus of UCB, in the first two years, Tarija struggled greatly with implementing the objectives of the IUC program and launching its TLC team with very few members. Both management and academic staff members reiterated that the program had not been able “to bridge the gaps between the regional campuses”. At the institutional level, organisation members alluded to the asymmetric relation with the national administration, particularly the national coordinator and national project leaders, who were at that time still all based in La Paz. The academic staff members as well felt underappreciated because research-related decisions were frequently taken at the central level. In addition, some TLC members shared similar experiences in their relation with the regional authorities, and felt they had to accept top-down decisions which were pushed through.

However, in year three, these sensemaking practices, which had mainly been built on ideas of inferiority and disregard, moved towards a narrative of empowerment and self-confidence. Organisation members praised the small scale of the campus for its flat organisational structure, with very little hierarchy, substantial ownership, and a pragmatic approach. Both the observations and the interviews indicated a friendly, informal, and relaxed atmosphere. As one organisation member explained: “Here, we all know each other well, we get along. If anyone leads or not, there is no problem in that regard”.

The breakthrough came with the appointment of a TLC coordinator who invested a lot of time in negotiations. He decided to involve more academic than management staff members with the TLC team, which not only “motivated the group”, but also improved the goal orientation of the fieldwork. As the team became more self-governing, gained more local ownership, and started to take more autonomous and self-confident decisions, the unequal relationship between Tarija and the national coordination also changed. These successes fuelled new dynamics of social energy on the campus, built on ideas of partnership and friendship: “We are so empowered as a group that we often forget that there is a pyramidal structure”.

For this team, “building a community” became the main paradigm in their understanding of TLC, not only to make sense of themselves, but also in how they defined their work with Cirminuelas, the area of intervention. TLC members highlighted that “the affection of the people” towards them was “spectacular”, and they were proud to tell that they were successful at building a collaborative relationship with local actors and at appearing “on their agenda”.

Discussion

Given their distinct organisational culture and management, embedment in the IUC program, grounding in the region, and experiences with community stakeholders, the sensemaking process of TLC at the four university campuses was different in terms of the functioning of the team, the implementation of the approach, and the local involvement. Despite the particularities of each regional reality, similarities in the process could also be observed.

Firstly, it is interesting to note that in all four cases of this study a more productive appropriation of TLC seemed to be facilitated by continuous communication and horizontal-type interaction among academic staff members. For example, in Cochabamba and La Paz, the two campuses that experienced the most difficulties with the roll-out of TLC, there was a breakthrough as conditions were created to have more interactions among the organisation members. In Santa Cruz and Tarija, their organisational culture of horizontal and informal interaction, based on values such as trust, openness, and commitment, contributed considerably to a fast-paced implementation of TLC in the university departments involved.

Secondly, we learned that the quality of communication and interaction among the academic TLC members appeared important for the roll-out of TLC in the external environment, i.e. the collaboration with the local community actors and other stakeholders. The teams that experienced the most difficulty with internal communication and a lack of active and participative discussion (Cochabamba and La Paz) also experienced more problems in their work in the field with the external social actors. The teams that were characterised by close and fluent communication (Santa Cruz and Tarija) were able to establish more productive relations with the actors in the field and articulate a shared mission. Thus, the type of communication and interaction among academic organisation members seems to influence the fieldwork of a development program such as IUC. Likewise, the cases of Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, and Tarija showed that group visits to the field and actual interaction with community actors and stakeholders seemed conducive to the appropriation and development of an action and community-based methodology such as TLC.

Although the organisational university context and its authorities were not without importance, as the four cases showed, in our study this level seemed to be less crucial for the implementation of TLC. This can probably be explained by the way in which IUC was from the onset conceived as a true cooperation, with clear equivalent input from the academic rather than the management staff members of UCB.

Nevertheless, in the rather hierarchical university context investigated here, the disconnection between management and academic staff members could be an obstacle to a swifter implementation of TLC. The case of Tarija showed the difficulties in this regard, because of the asymmetries they faced. The team from La Paz, which had experienced difficult discussions and labourious meetings in making sense of TLC, expressed frustration about their distant and disconnected relationship with the university management, and came to realise that management support was crucial for success. Conversely, we also saw that in organisations such as Santa Cruz and Cochabamba, where the degree of institutional willingness to implement TLC was high, collective sensemaking processes led more quickly to a productive roll-out of TLC.

Conclusion

In this study we aimed to understand how university staff members of a Bolivian university made sense of the roll-out of TLC on their campus as part of a larger university cooperation project for development. We were interested in how the organisational members made this process sensible or, in Weick’s (Citation1995) wording, how they constructed what they constructed and with what effects. We analysed various sources of organisational talk to reconstruct the central features of their sensemaking processes in an attempt to explain the different paces of appropriation observed. The analysis showed that although each university campus took a different road to reach the destination, the central component in implementing the TLC approach proved to be communication among the university staff members of the TLC teams. The sensemaking data revealed that the informal, horizontal, and symmetrical style of organisational communication between members who form a group for functional reasons seems to affect the success of cooperation with communities and other external partners in the social environment. The TLC teams that were successful at horizontal communication within the university context also better managed to relate to the local communities in a more collaborative way.

Within the scope of our study, we were only interested in how the introduction of the TLC approach was made sensible by the Bolivian partner in the university cooperation project, i.e. the receiving partner of support for action-oriented knowledge production. However, there is no question that the Flemish university staff members as well as local stakeholders, engaging in this process from different positions, also affect sensemaking and appropriation of TLC. As argued by others, inquiry into the effects of sensegiving activities on sensemakers is just as important (Maitlis and Sonenshein Citation2010). Hence, insights into the sensegiving activities of the Flemish university staff members, who played a leading role in creating meanings for the Bolivian colleagues (cf. definition of TLC), will certainly also contribute to a better understanding of the social dynamics in university cooperation programs and the challenges this entails. Furthermore, we learned that the non-academic partners in the priority areas for action played a critical part in how TLC is constructed. It would thus be valuable to widen the study toward these organisational stakeholders.

In spite of its limitations, this study adds to our understanding of the pivotal role of communication in organising university cooperation projects in a development framework, and more specifically, in making externally introduced change work. As such, it corroborates the key findings of sensemaking research that organisational talk is pivotal, as it talks organisational reform and re-organisation into existence (Ford and Ford Citation1995; Thurlow and Helms Mills Citation2009). Probably because IUC and TLC open up many developmental opportunities both for Bolivian research and society, all campuses showed a commitment to the program and its methodological approach. Hence, in most cases the tensions and asymmetries had less to do with the university top management towards academic staff, but more with university staff members themselves who were responsible for implementing the bulk of TLC efforts. This entailed a lot of extra reporting and consultation work, also caused by the matrix model, which put pressure on a staff that is relatively small, with an already heavy workload, and that is required to change its routines. In line with critical sensemaking research, we found that the campuses’ commitment to IUC and TLC produced an institutional context that allowed a certain degree of freedom of action and in some cases played an active role in supporting open discussion forums to collectively make sense of TLC and the new realities it entails in terms of organisation and relevance of academic research.

This is not to say that questions about asymmetric relationships did not surface. As an approach that challenges traditional ways of doing academic research, TLC can be disruptive and put a strain on relationships with authorities, other academic disciplines, non-academic local stakeholders, and communities. However, in our study, most of the university staff members considered this as part of the process and were committed to invest efforts in appropriating the methodological approach, which is ultimately aimed at improving the life conditions in their country.

Finally, even though the findings of this study are context-specific, they have a number of practical implications for university cooperation development projects that aim to implement action- and community-based methodologies such as TLC. The first stems from the connection between successful appropriation and horizontal communication. An assessment of the organisational culture of the targeted university teams might be recommended, in order to learn how important values such as trust, commitment, and openness are involved, and how they are enacted in day-to-day organisational communication. A second practical implication is for university management seeking to encourage TLC implementation within their university. Leadership interventions can be advantageous if they create more space for continuous communication, open dialogue, and active engagement. A third practical implementation concerns the interaction with non-academic actors (NGO’s, civil society organisations, community actors, etc.). The results of this study clearly show that community stakeholders and actors need to be involved from the early stages of the process, as this not only increases the likelihood of a more productive appropriation of TLC, but also of a more favourable climate for collaborative communication among academic actors.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download JPEG Image (1.3 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Guadalupe Peres-Cajías

Guadalupe Peres-Cajías PhD student in Media and Communication Studies at Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Belgium). Professor and Researcher at Universidad Católica Boliviana “San Pablo” (La Paz, Bolivia). Scholarship-holder of IUC VLIR-UCB Program.

Joke Bauwens

Joke Bauwens Associate Professor. Department of Media and Communication Studies, Research group ECHO, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Belgium).

Marc Craps

Marc Craps Emeritus Professor. Faculty of Economics and Business Management, Centre for Corporate Sustainability, KU Leuven (Belgium).

Gerrit Loots

Gerrit Loots Emeritus Professor. Department of Sociology, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (Belgium).

References

- Agar, M. 2010. “On the Ethnographic Part of the Mix: A Multi-Genre Tale of the Field.” Journal of Organizational Research Methods 13 (2): 286–303. doi:10.1177/1094428109340040.

- Anyidoho, N. A. 2010. “Communities of Practice: Prospects for Theory and Action in Participatory Development.” Development in Practice 20 (3): 318–328. doi:10.1080/09614521003710005.

- Baly, O., F. Kletz, and J. C. Sardas. 2016. “Collective Sensemaking: The Cave within the Cage,” Paper presented at 76th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Aug. 2016, Anaheim, United States. hal-01305315.

- Beigel, F. 2013. The Politics of Academic Autonomy in Latin America. New York: Routledge.

- Blaikie, N. 2009. Designing Social Research: The Logic of Anticipation. 2nd ed. London: Polity Press.

- Blanes, J (Compiler). 2018. Comunidades de Prácticas en Chipaya, Experiencias de Resiliencia. [Communities of Practice in Chipaya: Experiences of Resilience]. La Paz: Editorial Presencia.

- CEPAL. 2019. Panorama Social de América Latina, 2019 . [Social Panorama of Latin America] (LC/PUB.2019/22-P/Rev.1). Santiago: NU-CEPAL.

- Craps, M. 2019. “Transdisciplinarity and Sustainable Development”.” In Springer Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education, edited by W. L. Filho, 1–8. Cham: Springer.

- Dewulf, A., M. Craps, and R. Bouwen. 2005. “How Indigenous Farmers and University Engineers Create Actionable Knowledge for Sustainable Irrigation.” Action Research 3 (2): 175–192. doi:10.1177/1476750305052141.

- Ford, J. D., and L. W. Ford. 1995. “The Role of Conversations in Producing Intentional Change in Organizations.” Academy of Management Review 20 (3): 541–570. doi:10.5465/amr.1995.9508080330.

- Gioia, D., J. Thomas, S. Clark, and K. Chittipeddi. 1994. “Symbolism and Strategic Change in Academia: The Dynamics of Sensemaking and Influence.” Organization Science 5 (3): 363–383. doi:10.1287/orsc.5.3.363.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 2019. Ethnography: Principles in Practice. 4th ed. New York: Routledge.

- Helms Mills, J., A. Thurlow, and J. Mills. 2010. “Making Sense of Sense Making: The Critical Sensemaking Method.” Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management on International Journal 5 (2): 182–195. doi:10.1108/17465641011068857.

- Ito, K., and T. Inohara. 2015. “A Model of Sense-Making Process for Adapting New Organizational Settings, Based on Case Study of Executive Leaders in Work Transitions.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 172: 142–149. d oi:1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.347.

- Jansen, B. 2020. Rethinking Community Through Transdisciplinary Research. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Louis, K. S., K. Febey, and R. Schroeder. 2005. “State-Mandated Accountability in High Schools: Teachers’ Interpretations of a New Era.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 27 (2): 177–204. doi:10.3102/01623737027002177.

- Lozoya-Santos, J., B,J Guajardo-Leal, A. Vargas-Martínez, I. Molina-Gaytán, A. Román-Flores, R. Ramírez-Mendoza, and R. Morales-Menendez. 2019. “Transdisciplinary Learning Community: A Model to Enhance Collaboration between Higher Education Institutions and Society”. Paper presented at IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Dubai, April 9–11 622–630.

- Maitlis, S. 2005. “The Social Processes of Organizational Sensemaking.” The Academy of Management Journal 48 (1): 21–49. doi:10.2307/20159639.

- Maitlis, S., and S. Sonenshein. 2010. “Sensemaking in Crisis and Change. Inspiration and Insights from Weick (1988).” Journal of Management Studies 47 (3): 551–580. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00908.x.

- Moilanen, J., T. Montonen, and P. Eriksson. 2018. “Power in the Commercialization Process: Adopting a Critical Sensemaking Approach to Academic Entrepreneurship.” In Leveraging Human Resources for Human Management Practices and Fostering Entrepreneurship, edited by A. K. Dey, and T. Thatchenkery, 307–315. New Delhi: Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Limited.

- Seale, C. 2004. “Validity, Reliability and the Quality of Research.” In Researching Society and Culture, edited by C. Seale, 71–84. London: Sage.

- Thurlow, A., and J. Helms Mills. 2009. “Change, Talk and Sensemaking.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 22 (5): 459–479. doi:10.1108/09534810910983442.

- Weber, K., and M. Glynn. 2006. “Making Sense with Institutions: Context, Thought and Action in Karl Weick’s Theory.” Organization Studies 27 (11): 1639–1660. doi:10.1177/0170840606068343.

- Weick, K. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Weick, K. 2005. “Managing the Unexpected: Complexity as Distributed Sensemaking.” In Uncertainty and Surprise in Complex Systems: Questions on Working with the Unexpected, edited by R. R. McDaniel Jr, and D. J. Driebe, 51–65. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.