ABSTRACT

Women’s groups are a widely implemented and researched development intervention, particularly in South Asia and Africa. Groups encompass many models and aim to address a range of objectives. However, there is no consistent approach to describing their varied implementation models, which hinders the accurate interpretation of evidence and construct validity. Drawing from three recent evidence reviews and research experience with groups, we propose a typology and common reporting indicators to describe women’s groups. As large-scale investments in women’s groups grow, these tools can support the interpretation and transferability of evidence across models and settings.

Background

A women’s group – defined here as a voluntary group in which the majority of members are women – typically is formed to serve a common interest and for members to provide social, material, or other support to one another. Women’s groups have played an important role in feminist movements to advance women’s economic participation, environmental activism, and reproductive rights.Footnote1 Women’s groups come together in various ways, such as through informal cultural groups, as part of local social movements, financial Self-Help Groups (SHGs), adolescent or young mother’s groups, community mobilisation groups towards development, political organisations, trade unions, and producers’ collectives. Over the past 20years, a large body of research (Prost et al. Citation2013; Anderson, Biscaye, and Gugerty Citation2014; Brody et al. Citation2015; Kumar et al. Citation2018; Barooah et al. Citation2019; Desai et al. Citation2020) has emerged on the effects of such group-led approaches, albeit primarily with a focus on groups formed as part of development interventions rather than autonomously formed and operating groups. Evidence spans a range of outcomes, including financial inclusion, asset ownership, health and nutrition, and women’s autonomy. However, there is no consistent approach to classifying or describing implementation models of women’s groups in the impact evaluation literature.

Consistent descriptions of women’s group models and attention to implementation details can support sharing of the different types of groups in practice as well as the transferability of evidence. Although they share some common features, women’s groups function differently across and within settings depending on characteristics such as who formed them, the organising purpose, membership criteria, and primary activities. For example, a government-formed SHG in India is comprised of 10–12 women who meet weekly to collect savings in a bank, while a village savings group in Uganda includes 20–30 women and men who keep savings in a group lockbox that can be “shared out” in a predefined cycle. Autonomous women’s organisations, such as the Self-Employed Women’s Association, mobilise women workers into a trade union, occupational groups, and women-owned cooperatives, each with their own set of membership criteria and activities. Or, in another model, community members form groups with the support of an NGO or local health worker, to address health problems through open, facilitated meetings as part of a participatory learning and action cycle. Members of Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCA) typically gather for meetings during which each member contributes an amount to a collective “pot”, which is then given to one member who is excluded from receiving the pot in future meetings but still obliged to contribute (Anderson and Baland Citation2002).

Common definitions can also inform the growing investments in large-scale women’s groups programs across settings. For example, in India, the National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM) aims to mobilise 70 million households into women’s SHGs. India’s National Health Mission supports the scale up of women’s groups practicing participatory learning and action, facilitated by community health workers. In Bangladesh, the Grameen Bank, BRAC, and the Association for Social Advancement offer microloans to millions of households. The Nigeria for Women project aims to mobilise over 300,000 women into Women’s Affinity Groups. In Uganda, several large-scale, government-supported programs actively work with women’s groups, such as the Project for Financial Inclusion in Rural Areas and the Uganda Women’s Entrepreneurship Programme.

The large, and growing, evidence base on women’s groups in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) spans impact evaluations, process studies, and qualitative research, mainly using economic, public health, and anthropological methods. Impact evaluation studies have focused on the contribution of women’s groups to development outcomes – such as consumption and asset ownership, health, and women’s agency. However, the definitions and features used to describe women’s groups vary widely across studies, which in turn, limit the transferability of evidence and insights across contexts. We also note that the existing literature, particularly impact evaluation research, focuses mainly on formal or externally constituted groups, with relatively few evaluations of autonomously created social or cultural women’s groups. This is in contrast to anthropological and sociological research, which has a long history of studies on ROSCAs, for example (e.g. Ardener Citation1964; Geertz Citation1962), and research on different types of autonomously constituted groups, informal associations, and social networks amongst women (Desai Citation1996; Mahmud Citation2001; Lont and Hospes Citation2004; Kumar Citation2012; Chatty and Rabo Citation2020).

Our experience conducting and synthesising research on women’s groups across several LMICs suggests that consistent descriptions of implementation models could improve learning from research, both within and across contexts. In line with this viewpoint,Footnote2 we propose: (i) a typology and (ii) a set of common reporting indicators to improve the utility of the evidence base on women’s groups.

How to describe a women’s group?

A three-level typology

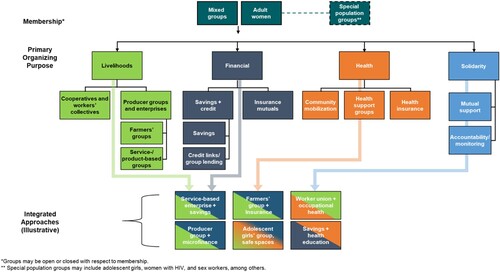

The current impact evaluation literature, as well as documentation by implementers, policymakers, and funders uses many different terms to define women’s groups. These range from umbrella terms, such as women’s groups or women’s empowerment collectives, to sector-specific categories, such as livelihoods groups, group-based microfinance, self-help groups, or savings groups. However, these terms are not commonly understood or mutually exclusive across important characteristics of a women’s group, such as its purpose or membership criteria. In response, some evidence syntheses have proposed typologies to categorise women’s groups. The most common characteristic currently used by researchers to describe women’s groups is the groups’ primary organising purpose or function, e.g. health, savings, and credit or livelihoods. For example, Kumar et al. (Citation2018) identified four categories of women’s groups in South Asia – microfinance, livelihoods, multi-sectoral, and behaviour change – that work through different pathways to improve nutrition (Kumar et al. Citation2018). Anderson, Biscaye, and Gugerty (Citation2014), focusing on South Asia and Africa, proposed a taxonomy of groups in which groups vary in member participation in group governance and a continuum of creating social relative to private benefits. Categories that emerged included livelihood groups, informal and formal savings and credit groups (e.g. Rotating Savings and Credit Associations and SHGs), and health groups comprised of women’s health groups and health clubs (Anderson, Biscaye, and Gugerty Citation2014; Gugerty, Biscaye, and Anderson Citation2019). Barooah et al. (Citation2019) proposed a categorisation by informal and semi-formal institutions, with the latter subdivided into community-based, solidarity-based, and livelihood-based groups (Barooah et al. Citation2019). Other possible dimensions for a typology include member characteristics – which may refer to mixed-gender groups, women-only groups or a specific group of women (i.e. women with a disability), group size or level (village, district, national), and how the group was created and operates (e.g. autonomously or facilitated by an external agency). In addition, Gram, Desai, and Prost (Citation2020) distinguish between three different types of approaches adopted by community-based groups to deliver health interventions: classrooms, clubs, and collectives. According to this typology, classrooms engage groups as a platform for reaching populations, while clubs aim to build, strengthen, and leverage relationships between group members, and collectives use a particiaptory approach to engage whole communities to identify local problems and solutions.

These dimensions could expand the universe of groups, beyond women’s groups to the wider range of community groups such as those formed for political, sports, or religious purposes. Mansuri and Rao (2013) provide a broader overview of the landscape of community-driven development approaches, including groups. In this paper, we focus specifically on ways to describe and categorise women’s groups, with the impact evaluation literature as our starting point.

Existing typologies of women’s groups mainly focus on their primary organising purpose. However, groups typically do not perform a single function in practice. For example, a portfolio evaluation of 46 Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation investments in women’s groups across over 20 countries found that 38 of 57 groups had integrated programs, wherein existing or new groups engaged in multiple activities, most commonly health and microfinance (Anderson et al. Citation2019). A scoping review of women’s groups in Uganda found that the most common combination of activities was savings and credit, followed by livelihood activities combined with savings and/or credit, as well as cases in which a savings group included health activities (Namisango, Mulyampiti et al. Citation2022). Groups also differ by who they intend to reach – members only or the wider community – and by who initiated the group. In India’s Mahila Samakhya program, women’s groups prioritised their own activities, but spillover effects reached beyond members to support community development (Janssens Citation2011). In Uganda, some health-oriented groups were more likely to have a membership comprised exclusively of women than other groups focused on savings, credit, or livelihoods, sometimes targeting younger women or adolescents (Namisango, Mulyampiti et al. Citation2022).

proposes three levels of characteristics to describe a group by: (i) membership, (ii) primary organising purpose, and (iii) secondary activities. An SHG could be described as: “an all-women savings and credit group that also implements health and livelihoods activities”. Similarly, an agriculture group may be described as a “mixed producer group that provides crop and health insurance”, while another may be “a sex workers collective for member solidarity, along with microfinance and health activities.” applies this typology to five examples.

Table 1. Applying a basic typology of women’s groups.

Implementation characteristics

Consistent documentation of the way groups are implemented – such as who forms them, membership criteria, meeting frequency, and activities – enables comparability, as well as transferability of evidence across settings (Masset and White Citation2019). We examined four recent evidence syntheses of published and grey literature on women’s group interventions to compare how implementation characteristics were described (). A review of 44 impact evaluations of the effect of groups on health outcomes in India found that fewer than half of the studies reported on the size of groups, and 28/44 included the frequency of meetings (Desai, Misra et al. Citation2020). While most studies reported on facilitator characteristics, only a small proportion described how facilitators were trained or paid.

Table 2. Implementation characteristics reported in evaluationsa

A scoping review to examine the evidence base on women’s groups in Uganda, which included 66 studies, of which 10 were experimental or quasi-experimental evaluations, found that most studies reported the gender composition of groups, but relatively few reported group size or meeting frequency, and less than half reported facilitator characteristics (Namisango et al. Citation2022). Almost all of the groups reported on were externally formed, with relatively little research on autonomously formed groups. Similarly, information on group implementation models was limited in a portfolio evaluation of Gates Foundation investments of women’s groups, despite access to program reporting documents (Anderson et al. Citation2019). Overall, we found that studies do not describe women’s groups with sufficient detail or consistency to compare evidence across settings or to inform the implementation of women’s group programs.

Consistent reporting on implementation models also allows for comparison across seemingly distinct models. For example, Ethiopian village savings and loan associations (VSLAs) are typically more informal and aimed at collective risk pooling, while Bangladeshi microfinance groups are formally linked to a bank. Yet groups in Bangladesh and Ethiopia both meet regularly, maintain similar records, and include trained facilitators. Moreover, key differences across models may determine effectiveness. Women’s groups who practiced participatory learning and action in Jharkhand and Odisha, India, were open to all community members – a factor that may have supported population-level effects on neonatal mortality (Prost et al. Citation2013). On the other hand, groups formed to conduct health education on maternal and newborn health and microfinance in Bihar were closed to women members who contribute savings, and thus, only reached two to four pregnant women/new mothers per SHG (Saggurti et al. Citation2018). However, these two distinct models – groups practicing participatory learning and action that are open to all community members and groups formed to conduct health education to women members only – are commonly considered as the same category in evidence syntheses (Kumar et al. Citation2018; Dìaz-Martin et al. Citation2020).

proposes a set of reporting indicators/characteristics to describe women’s group implementation models across five categories. The group’s primary purpose and secondary activities, similar to the typology, describe both the initial purpose of the group and its additional functions. Some health groups involve entire communities, while most financial groups focus on members. In some settings, livelihoods groups are federated at a geographic level of business unit to facilitate governance, increasing access to credit and access to markets. The category of indicators on group membership, eligibility, and retention requirements identifies who groups include – and importantly, who they may exclude. Group meeting norms include frequency and length of meetings, as well as where and why groups meet. Lastly, we include several characteristics of group facilitators that may influence group functioning. These characteristics refer to descriptions of group implementation as designed, or “in theory”, to facilitate comparison across models. They may also help evaluators monitor implementation quality and fidelity to the intended design.

Table 3. Reporting indicators for women’s group implementation models.

and use these indicators to compare two types of women’s group interventions evaluated for the same outcome. In the first example, two group-based approaches aimed to reduce violence against women in rural India. In the Do Kadam intervention, government SHGs in rural Bihar worked with a non-governmental organisation to address violence against women through integrating gender sensitisation sessions into SHGs (Jejeebhoy et al. Citation2018). In the second model, Ekjut, a non-governmental organisation in Jharkhand, conducted a participatory learning and action cycle with open women’s groups to reduce violence against women (Nair et al. Citation2020). Both women’s groups aimed to sensitise women on gender-based violence and link them to services through groups, with variation in group purpose, size, and eligibility requirements. In a second example, we compare an adolescent girls group model (Bandiera et al. Citation2020) with a VSLA model in Uganda (Karlan et al. Citation2017). While there are some similarities, the differences in these models highlight why research on women’s groups should interpret evidence by comparing implementation models and their outcomes, even in the same context.

Table 4. Two women’s group models to address VAW in India.

Table 5. Two women’s group models to address women’s empowerment and economic outcomes.

Discussion

Women’s group-based interventions continue to grow in LMICs, with the ambition to improve a range of outcomes related to women’s well-being. While, in some cases, group formation is the intervention itself (Karlan et al. Citation2017), we found that evaluations of an “add-on” component to women’s groups often lack an adequate description of the underlying group. We propose a high-level typology to describe women’s groups, along with a common set of indicators for researchers and implementers to use when describing a group model. These indicators could be used in conjunction with existing guidelines to describe intervention delivery, such as the TiDIER framework (Hoffmann et al. Citation2014).

Our typology and report indicators offer two contributions to the researchers and practitioners engaged with women’s groups (Desai, de Hoop et al. Citation2020). One, the simplicity allows for wide usage across contexts and types of women’s groups. We suggest research on women’s groups includes a simple box to describe the group and its design characteristics. Two, the reporting indicators can contribute to a better understanding of pathways to change and identifying relevant outcomes for women’s group interventions: e.g. group organising purpose identifies impacts and outcomes; eligibility criteria can be linked to analyses of heterogeneity of impacts; and meeting norms and facilitator characteristics can point to implementation quality.

Researchers may face some limitations in applying the typology and reporting indicators in practice. Since most of the available evidence focuses on groups in South Asia and parts of Africa, the typology may not encompass all models in other settings. Further, we acknowledge that the evaluation literature, and thus our examples, focuses on externally formed or formal groups – which do not represent the universe of all women’s social, economic, cultural, and political groups. Differentiating a group’s primary and secondary objectives may not be possible for some groups, in which case, the reporting indicators will be more relevant than the typology. Moreover, there is a wide range of other types of groups that share similar or different development objectives towards women’s empowerment and community mobilisation, such as political associations or cultural groups that are less commonly evaluated. While our specific typology has been drawn from the impact evaluation literature on women’s groups (Brody et al. Citation2015; Anderson et al. Citation2019; Desai, Misra et al. Citation2020; Mulyampiti et al. Citation2022), the principles of a common typology and reporting indicators could be applied more widely to research with other community groups. Future efforts can focus on developing similar typologies and checklists for other community-based groups, as well as expanding the evidence base to study and evaluate autonomously created/operating groups more widely. Importantly, the typology should be further developed through primary research and consultation with women’s groups to reflect characteristics that research thus far may not have captured. Direct engagement can also incorporate women’s views, which will vary by context, on group identity, underlying power structures, and the multiple factors that inform group functioning.

We aimed to create a generalisable, relatively short list of indicators that could be applied across fields and impact evaluations focused on women’s groups. We have not yet tested the typology and indicators beyond the examples cited; our intention is to continue to engage with women’s groups members, researchers, and practitioners to refine both content and usability.

Transferability of evidence on women’s groups depends on the comparability of implementation models, amongst other factors (Masset and White Citation2019). Moving away from umbrella terms towards meaningful descriptions will support a better understanding of the diversity of women’s groups. Clearly defining (i) the type of women’s group and (ii) key implementation characteristics will allow policy makers, implementers, and researchers to interpret evidence with clarity, as well as strengthen transferability of evidence between contexts. It also decreases the risk that policy makers use evidence from impact evaluations of one model to support the use of different implementation models for which evidence is limited (Bold et al. Citation2018). We hope these tools can be adapted and used widely to support accurate interpretation and application of evidence on the rich range of women’s groups in practice.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Roopal Jyoti Singh and Carly Schmidt for contributions to the typology and reporting indicators, and to David Seidenfeld and two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sapna Desai

Sapna Desai is an Associate at the Population Council India, where she focuses on women's groups, women's health and well-being and health systems. She co-leads the Evidence Consortium on Women's Groups.

Thomas de Hoop

Thomas de Hoop is a managing economist and program area lead for food security, agriculture, and nutrition at American Institutes for Research. He is also co-lead of the Evidence Consortium on Women's Groups.

C. Leigh Anderson

C. Leigh Anderson is the Marc Lindenberg Professor for Humanitarian Action, International Development and Global Citizenship at the University of Washington's Daniel J. Evans School of Public Policy and Governance and the founder and director of EPAR.

Bidisha Barooah

Bidisha Barooah is Lead Specialist at 3ie where she leads evidence programs on gender and livelihoods. She has a PhD in Economics from Delhi School of Economics.

Tabitha Mulyampiti

Tabitha Mulyampiti is a Senior Lecturer in the Gender Studies Department at Makerere University, Uganda. She is a development researcher who focuses on women's movements, social change and social transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Ekwaro Obuku

Ekwaro Obuku is Co-Founder and Co-Director of the Africa Centre for Systematic Reviews and Knowledge Translation, Makerere University, Uganda. He currently serves as Senior Technical Advisor Global Health Security at the Infectious Diseases Institute Makerere University, Uganda and teaches evidence synthesis at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, University of London.

Audrey Prost

Audrey Prost is Professor of Global Health and Co-Director of the Centre for the Health of Women, Children and Adolescents at University College London. She has over 15 years' experience developing and evaluation community mobilisation interventions with women's groups to improve health, primarily in India.

Howard White

Howard White is Director of Evaluation and Evidence Synthesis, and previously CEO of the Campbell Collaboration and Executive Director of International Initiative for Impact Evaluation.

Notes

1 Abbreviations: LMIC: Low and middle-income country; SHG: Self-help group; NRLM: National Rural Livelihoods Mission (India); and VSLA: Village savings and loan association.

2 This paper is based on the working paper: Desai, de Hoop et al. (Citation2020).

References

- Anderson, S., and J.-M. Baland. 2002. “The Economics of Roscas and Intrahousehold Resource Allocation.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (3): 963–995.

- Anderson, L., P. Biscaye, and M. K. Gugerty. 2014. “Self-Help Groups in Development: A Review of Evidence from South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.” EPAR Technical Reports, University of Washington Technical Report #28.

- Anderson, L., T. De Hoop, S. Desai, G. Siwach, A. Meysonnat, R. Gupta, N. Haroon, et al. 2019. Investing in Women's Groups: A Portfolio Evaluation of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation's Investments in South Asia and Africa.

- Ardener, S. 1964. “The Comparative Study of Rotating Credit Associations.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 94 (2): 201–229.

- Bandiera, O., N. Buehren, R. Burgess, M. Goldstein, S. Gulesci, I. Rasul, and M. Sulaiman. 2020. “Women's Empowerment in Action: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial in Africa.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12 (1): 210–259.

- Barooah, B., S. Chinoy, P. Dubey, R. Sarkar, A. Bagai, and F. Rathinam. 2019. Improving and Sustaining Livelihoods Through Group-Based Interventions: Mapping the Evidence (3ie Evidence Gap Map Report 13). New Delhi, India: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation.

- Bold, T., M. Kimenyi, G. Mwabu, and J. Sandefur. 2018. “Experimental Evidence on Scaling up Education Reforms in Kenya.” Journal of Public Economics 168: 1–20.

- Brody, C., T. De Hoop, M. Vojtkova, R. Warnock, M. Dunbar, P. Murthy, and S. L. Dworkin. 2015. “Economic Self-Help Group Programs for Improving Women's Empowerment: A Systematic Review.” Campbell Systematic Reviews 11 (1): 1–182.

- Chatty, D., and A. Rabo. 2020. “Formal and Informal Women’s Groups in the Middle East. Organizing Women.” Routledge, 1–22.

- Desai, M. 1996. “Informal Organizations as Agents of Change: Notes from the Contemporary Women's Movement in India.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 1 (2): 159–173.

- Desai, S., T. de Hoop, L. Anderson, B. Barooah, T. Mulyampiti, E. Obuku, A. Prost, and H. White. 2020. Improving Evidence on Women's Groups: A Proposed Typology and Reporting Checklist, Evidence Consortium on Women's Groups.

- Desai, S., M. Misra, A. Das, R. J. Singh, L. Gram, N. Kumar, and A. Prost. 2020. “Community Interventions with Women’s Groups to Improve Women’s and Children’s Health in India: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review of Effects, Enablers and Barriers.” BMJ Global Health 5 (12).

- Dìaz-Martin, L., A. Gopalan, E. Guarnieri, and S. Jayachandran. 2020. “Greater than the Sum of the Parts? Evidence on Mechanisms Operating in Women’s Groups.”.

- Geertz, C. 1962. “The Rotating Credit Association: A “middle rung” in development.” Economic development and cultural change 10: 241–263.

- Gram, L., and S. Desai. 2020. “Classroom, Club or Collective? Three Types of Community-Based Group Intervention and Why They Matter for Health.” BMJ Global Health 5 (12).

- Gugerty, M. K., P. Biscaye, and C. Anderson. 2019. “Delivering Development? Evidence on Self-Help Groups as Development Intermediaries in South Asia and Africa.” Development Policy Review 37 (1): 129–151.

- Hoffmann, T., P. P. Glasziou, I. Boutron, R. Milne, R. Perera, D. Moher, D. G. Altman, V. Barbour, H. Macdonald, and M. Johnston. 2014. “Better Reporting of Interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist and Guide.” Bmj 348.

- Janssens, W. 2011. “Externalities in Program Evaluation: The Impact of a Women's Empowerment Program on Immunization.” Journal of the European Economic Association 9 (6): 1082–1113.

- Jejeebhoy S. J., and K. G. Santhya. 2018. “Preventing violence against women and girls in Bihar: challenges for implementation and evaluation.” Reproductive Health Matters 26 (252): 92–108.

- Karlan, D., B. Savonitto, B. Thuysbaert, and C. Udry. 2017. “Impact of Savings Groups on the Lives of the Poor.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (12): 3079–3084.

- Kumar, S. 2012. Micro-Finance, Women Empowerment and Health: An Anthropological Study of Self Employed Women Association (SEWA), Bikaner, Rajasthan.” PhD University of Delhi.

- Kumar, N., S. Scott, P. Menon, S. Kannan, K. Cunningham, P. Tyagi, G. Wable, K. Raghunathan, and A. Quisumbing. 2018. “Pathways from Women's Group-Based Programs to Nutrition Change in South Asia: A Conceptual Framework and Literature Review.” Global Food Security 17: 172–185.

- Lont, H. B., and O. Hospes. 2004. Livelihood and Microfinance: Anthropological and Sociological Perspectives on Savings and Debt. Eburon Uitgeverij BV Utrecht.

- Mahmud, S. 2001. “Group Dynamics and Individual Outcomes: Women's Informal Groups in Rural Bangladesh.” The Bangladesh Development Studies 27 (2): 115–136.

- Masset, E., and H. White. 2019. “To Boldly Go Where No Evaluation Has Gone Before: The CEDIL Evaluation Agenda.”.

- Mulyampiti, T., T. de Hoop, E. Namisango, R. Apunyo, N. Muhidini, E. Okiria, R. S. Alyango, et al. 2022. Scoping Review of the Evidence on Women’s Groups in Uganda. ECWG, Evidence Consortium on Women's Groups.

- Nair, N., N. Daruwalla, D. Osrin, S. Rath, S. Gagrai, R. Sahu, H. Pradhan, M. De, G. Ambavkar, and N. Das. 2020. “Community Mobilisation to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls in Eastern India Through Participatory Learning and Action with Women’s Groups Facilitated by Accredited Social Health Activists: A Before-and-After Pilot Study.” BMC International Health and Human Rights 20 (1): 1–12.

- Prost, A., T. Colbourn, N. Seward, K. Azad, A. Coomarasamy, A. Copas, T. A. Houweling, E. Fottrell, A. Kuddus, and S. Lewycka. 2013. “Women's Groups Practising Participatory Learning and Action to Improve Maternal and Newborn Health in Low-Resource Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet 381 (9879): 1736–1746.

- Saggurti, N., Y. Atmavilas, A. Porwal, J. Schooley, R. Das, N. Kande, L. Irani, and K. Hay. 2018. “Effect of Health Intervention Integration Within Women's Self-Help Groups on Collectivization and Healthy Practices Around Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health in Rural India.” PLoS One 13 (8): e0202562.