ABSTRACT

There is a paucity of official data on violence against women (VAW) in Mexico. Two-hundred and seventy-two household surveys and seven focus group discussions with 50 women were conducted to explore women’s experiences of VAW in public spaces in Corregidora, Mexico. Seven semi-structured interviews with stakeholders were carried out to understand their knowledge of VAW and reduction measures through infrastructure delivery and urban planning. Results showed that the most common and recurring type of VAW was catcalling, and 39 per cent of survey participants experienced at least one type of VAW. Government stakeholders appeared either unaware of the extent of VAW or were dismissive of its impact. The disconnect between women’s experiences and stakeholders’ views has implications for the design and implementation of safety measures for women.

Introduction

A state’s lack of (and sometimes unwillingness to report) data on VAW may limit the possibility of accessing information on VAW figures from the outset. Personal or political views of state agents may interfere with an administration’s decision-making powers by hindering the ability to make comparisons or understand the depth of the problem in a given location (Purkayastha and Ratcliff Citation2014). Additionally, poor crime-recording practices, deficient data management, and that some types of VAW might not be considered crimes may mean that incidents of VAW do not get recorded (Garfias Royo, Parikh, and Belur Citation2020; Lecuona and Raúl Citation2017). Consequently, informed decision-making for introducing measures for safer built environments and cities for women and girls is challenging.

In Mexico, there is a scarcity of official data and studies addressing VAW outside of Mexico City. While a national survey on VAW is conducted every five years by the National Institute of Geography (INEGI) and UN Women collects a global database on VAW that includes Mexico (INEGI Citation2021; Women Citation2023), there is a need for additional official and alternative sources of datasets containing information about VAW in the country that are further geographically disaggregated. This paper addresses some of the challenges of studying VAW by using a mixed-methods approach to explore the victimisation and experiences of violence against adult women in public spaces in Corregidora, Mexico. It also brings light to the state’s response to VAW in public spaces with respect to urban design and planning. The work presented in this paper is part of a larger study that sought to understand the link between VAW and the built environment.

Categorisation of violence against women

Violence has strong links to social norms, structures, and subjectivities intrinsic in gender, sexuality, class, ethnicity, ability, and religion, and is rooted in the social control exercised by the dominant groups (Levy Citation2013; McIlwaine Citation2013; Parkes Citation2015). The UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women defines VAW as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life” (UN Citation1993). Hegemonic masculinity traits (such as aggression, toughness, self-reliance, and sexual conquest) that males are expected to perform and the acceptance of traditional gender roles tend to condone and normalise different forms of violence and exclusion, actively contributing to the perpetuation further exacerbates the escalation of VAW (Frías Citation2016; Lindsey Citation1997). When patriarchy-as-usual and notions of women’s subordination are no longer fully secure, its reproduction requires greater levels of coercion (Kandiyoti Citation2016). While most cases of VAW are perpetrated by a partner in the domestic sphere (WHO Citation2012), this study refers to violence inflicted in the public sphere (which may or may not be perpetrated by strangers or partners).

When designing cities and urban policies, carrying out gender analysis of how designed spaces are used by different groups is typically not considered or often viewed as not important by local governments (Purkayastha and Ratcliff Citation2014; Soto Villagrán Citation2020). Understanding VAW in public spaces as a production of an enabling urban environment coupled with unequal and sexist sociocultural norms, it is important to utilise comprehensive approaches to provide pragmatic solutions as well as changing the sociocultural norms that give way to this violence (Bianchi Alves and Gonzales Citation2015; Soto Villagrán Citation2018).

This study categorises VAW into three main types: physical, sexual, and psychological. It must be noted, however, that there is an intrinsic interrelationship between them. In most cases, more than one type is committed simultaneously, leading to a continuum of experiences.

Physical violence is the most commonly understood form of abuse. It is exercised through physically aggressive acts that may not result in physical injury, and differs from sexual violence in that it does not include any sexual traits (Johnson Citation2006; Krantz and Garcia-Moreno Citation2005).

Psychological violence is usually used interchangeably with emotional abuse. This type of violence is usually perceived as a gendered crime and is strongly correlated to physical aggression and has harmful impacts on the victim (Scott et al. Citation2015). It is theorised to stem from power and control which a person exerts over another (victim) in order to prevent them from physically or emotionally separating and retaliating if the victim shows efforts to do so (Mechanic, Weaver, and Resick Citation2000).

Sexual violence can take many forms, such as sexual abuse, sexual harassment, sexual exploitation, forced abortion, and attempted rape/rape (WHO Citation2007). The concept and meaning of sexual harassment are shaped by its context, as the distinct legal framings stem from differences in political, legal, and cultural constraints and resources, which impact its social understanding (Saguy Citation2003). When committed in the public sphere, it can be referred to as “street harassment”, and it includes unwanted interactions in public spaces, motivated by a person’s actual or perceived gender, gender expression or sexual orientation, and it is most commonly perpetrated by a stranger (Garrido, Javiera, and Guerrero González Citation2017; Kearl Citation2014).

There are no universal definitions for the different types of VAW and related crimes, as each nation-state defines VAW from its own legal frameworks, leading to variations among data sources and countries (Leclerc et al. Citation2016), and regardless of the data set used, the possibility of under-counting exists (Sinha Citation2013).

Additionally, what women consider violence may be not recorded as such and may be downplayed in the data, such as recording an aggression as a less serious offence. Estimates of the prevalence of VAW vary vastly depending on the survey applied (Parkes Citation2015). There are also differences in measuring strategies of victimisation and crime between administrative and population-based surveys. For example, police-reported surveys only record criminal code offences, in contrast with population-based surveys which document information on crimes regardless of whether they were reported or substantiated by the police (Sinha Citation2013). Personal or political views may interfere with an administration’s decision-making powers, hindering the ability to make comparisons or understand the depth of the problem at a given location (Purkayastha and Ratcliff Citation2014).

Case study

There are scarce official figures on VAW in Mexico, despite countless unofficial accounts and anecdotal evidence from women throughout the country. Reports of harassment, rape, and femicides flood the news and social media daily. Women have become frustrated at the government’s inability to respond to this violence, as demonstrated by recurrent protests (cf. Villegas Citation2020; Aristegui Noticias Citation2022), including the occupation of the Human Rights Commission building by a feminist group in 2020 (Wattenbarger Citation2020).

Mexico’s social fabric has been steadily deteriorating, with violent crimes spreading with almost total impunity (Lakhani Citation2016). Some estimates have shown that only 6.3 per cent of crime incidents are reported at national level, and of these, about 99.5 per cent go unpunished and only 0.89 per cent are solved (Lecuona and Raúl Citation2017). The impunity has permeated the Mexican justice system, encouraging and facilitating the expression of many different types of violence, including VAW (Rubio Gutiérrez Citation2022; Lecuona and Raúl Citation2017). Women have become targets of torture, abductions and disappearances, arbitrary detention, criminalisation, and murder in alarming numbers (Bautista Citation2017). The Executive Commission for Attention to Victims (CEAV) reported that from 2010 to 2015 there was an average of 600,000 sexual crimes per year, of which, an estimated 81 per cent of the victims were women (CEAV Citation2016). The increase in crime has undermined the collective sense of security, and the failure to create law-abiding and effective police forces has led to a decrease in crime reporting and overall erosion of social capital (Rodriguez Ferreira Citation2016). This has an effect on the availability of information at the national level regarding crimes due to ineffective actions by the state and failure to follow the appropriate processes and documentation, as well as low interest in reporting, resulting in unknown and unclassified victims (Lecuona and Raúl Citation2017). The high levels of impunity signal that perpetrators of violence will face no consequences (Lakhani Citation2016; Melgoza, López, and Pigeonutt Citation2017).

The widespread VAW in Mexico is manifested in the rise of its most extreme expression: femicide. From January 2015 to May 2023, 6,826 femicides have been registered at the national level (SSNSP Citation2023). Many researchers and activists, however, suggest that these figures do not represent the true extent of the problem (Mobayed Vega Citation2022), with estimates from civil society groups showing that 46 out of 100 murders of women should have been typified as femicides (Durán Citation2020). A study conducted by ONU Mujeres, Inmujeres, and the Ministry of the Interior of Mexico (Citation2017) also showed a high rate of impunity in femicide cases through the number of preliminary investigations that led to a conviction.

This study was conducted in the urban public space of Corregidora Municipality in Querétaro state, Mexico. The state of Querétaro recognises sexual harassment as a crime; however, it still lacks the recognition of street harassment as a crime (Poder Legislativo del Estado de Querétaro Citation2022; Segura Amaro Citation2022). Corregidora Municipality has made efforts to introduce regulations for the use of parks and gardens, for citizen participation, and for access to a life free of violence and equality between men and women, announced through its monthly gazettes (Ayuntamiento de Corregidora Citation2019a; Citation2019c; Citation2019b). The Municipal Institute of Women seemingly also generates public policies with a gender perspective, paying attention to gender mainstreaming throughout the municipal public administration. But the reporting of activities is vague and does not accurately describe what, how, and when these activities took place. While the municipality’s publications increasingly refer to gender protocols and VAW commitments, this may be policy rhetoric and there is no evidence yet of such policies being substantively delivered or translated into procedures. This is reflected in the municipality’s scarce and outdated official data regarding VAW. Official municipal crime records are not published by the municipal police and fail to capture data on some types of VAW (such as public exposure; Informal conversation with main author). The gap of dissemination of cases of VAW and publicly available data on VAW in the municipality is usually filled by national statistics reported to the Mexican Secretariat of Public Security (SESNSP), a national survey regarding household dynamics with a focus on gender-related VAW conducted every five years (ENDIREH) from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography in Mexico (INEGI) and figures from local independent and autonomous institutions, but these numbers are not updated regularly and usually do not show how widespread VAW is in the municipality. The INEGI survey estimated that 59.8 per cent of the urban population of women in the state of Querétaro had experienced VAW in the public domain in their lifetime, and 33.8 per cent the year prior to the survey (INEGI Citation2022). The survey also found that less than 13 per cent reported the incident (INEGI Citation2022). The SESNSP figures reported 11 cases specifically labelled gender violence plus an additional 95 cases that could be labelled as VAW in Corregidora in 2021. However, the methodologies for recording crimes vary between municipalities and at different levels of government. This means that the cases reported could be much higher but is not possible to record them officially due to data inconsistencies. Furthermore, surveys tend to capture different data from official figures, leading to comparison discrepancies.

Method

It is not possible to draw conclusions on the extent of VAW in the municipality of Corregidora from the publicly available data. A mixed-methods approach was used on this research to conduct primary data collection. This was driven by the sensitivity of the subject and lack of crime statistics. Household surveys and focus group discussions were conducted with women, and semi-structured interviews with local government stakeholders. The unit of analysis was the urban public sphere of Corregidora Municipality. A collaboration was established with the local government of Corregidora Municipality, which allowed access to stakeholders as well as to Municipal Culture Centres to conduct focus group discussions. However, no access to local crime statistics was granted. Ethical approval was obtained from a UK University Ethics Committee and a local university in Mexico.

Household surveys

The household survey (HHS) was designed to gather information regarding incidents of VAW experienced in public spaces by women who were 18 years of age or older and residents of the selected urban localities of Corregidora Municipality. The questions consisted of 13 types of VAW, which were taken from INEGI’s National Survey on the Dynamics of Household Relationships, which also gathers data on VAW perpetrated in public spaces (ENDIREH for its acronym in Spanish; INEGI Citation2016a). The survey collected demographic information and explored topics such as types of violence experienced; experiences of VAW in the public sphere; frequency, time, and date of the incidents; locations where the incidents took place; and demographic data of the perpetrators. It is worth noting that this data was based on the women’s perceptions of VAW and no explanation about the types of violence asked on the survey were explained to the respondents prior, during, or after the survey. See for the types of VAW included in the survey.

Table 1. Types of VAW included in the survey.

At the time of sampling, the municipality was divided into 64 basic geostatistical areas (AGEBS), of which 60 were classified as urban and were clustered into six localities. The sample population was based on the 2010 Population and Housing Census of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography of Mexico, which reported a total estimated population of 181,684 inhabitants in 2018 and was the most recent census at the time the sample was calculated (INEGI Citation2010; Citation2015). Blocks were selected randomly from the National Housing Framework of 2016, which reported 828 inhabited dwellings with more than one household and information regarding the population at the time the sample was calculated (INEGI Citation2016b).

A two-stage simple random sample with a finite population correction design was used. A sample of 300 units (blocks) was calculated based on the population size, which included an additional 15 per cent to account for no responses. At the time of data collection, convenience sampling was used to select a random household within the sampled block.

The surveys were conducted in November 2018, Monday to Friday from 8:00 hrs to 18:30 hrs and Saturday and Sunday from 10:00 to 18:30 hrs. Safety measures included not conducting surveys after 18:30hrs – sunset time – due to security reasons. The surveys were carried out in Spanish by a team of eight local data collectors and the main author. The data collectors took a mandatory induction session delivered by the first author. Surveys took between half an hour to an hour, depending on the information the participants were willing to disclose. Data collectors were instructed to conduct the surveys in strict privacy, with no family members present; however, this was not possible in all instances. In the case of the latter, participants were given several opportunities to terminate the survey if they so wished. Security measures for the research team conducting surveys included not entering people’s houses, informing the first author (who managed and monitored collection) about the block where surveys were being applied and the starting and finishing times, setting boundary areas within neighbourhoods as well as meeting points for data collection activities, and being in constant communication. Given the sensitivity of the research, all the questions and answers were pseudonymised as a risk-mitigating strategy in case of breach of information.

Focus group discussions

A total of seven focus group discussions (FGDs) were held, with a combined total of 50 participants. The aim of the discussions was to understand the experiences of VAW of women in public spaces and the role that urban infrastructure and the built environment plays in the perpetration of VAW. The issues discussed included the definition of public spaces, perceptions of safe and unsafe spaces, fear of violence and crime, understanding of VAW, experiences of violence, and measures for safety.

The FGDs followed a purposive and convenience sampling strategy, allowing for the selection of participants based on accessibility (O Nyumba et al. Citation2018). Participants were recruited through a network of Cultural Centres, which also provided access to spaces to conduct the sessions in a safe, neutral space, and participants did not receive incentives. The FGDs were conducted in April 2019 and were administered by the main author.

Stakeholder interviews

A total of seven semi-structured stakeholder interviews were conducted to understand the local government decision-making processes that existed at the time regarding infrastructure delivery and urban planning. The interview themes included the application of gender-related protocols, knowledge of decision-making processes, and perception of violence within the municipality.

A brief stakeholder mapping based on the local government administration of 2015–2018 was carried out to identify actors that may have an influence on these decision-making processes. This was done in collaboration with a member of the former Instituto Municipal de Planeación de Corregidora (IMPLASCO), who informed the decision about which Institutes, Secretariats, or Ministries to approach. Stakeholders from the Planning Unit, Urban Development and Public Works, Treasury and Finance, Social Development, and three members of the Ministry of Mobility, Urban Development, and Ecology were interviewed.

Ethical considerations

This research raised several ethical challenges and posed risks for both the participants and researchers. Careful consideration was given to the use of appropriate language, locations for method application, reducing and managing participants’ distress, and the safety of both participants and data collectors. Risk assessments were completed prior to data collection to establish action plans and risk mitigating procedures, as well as to ensure the safety and security of the participants, data collectors, and the main researcher. The WHO's (Citation2001) safety and ethical guidelines for conducting research on domestic violence and trafficking were followed. The study was approved by the ethics panel of a UK university and a local university.

Analysis and coding

Univariate descriptive analysis was used to analyse the HHS, to understand frequency and percentage response distributions regarding the most common types of VAW. The FGDs and stakeholder interviews were analysed thematically using a mix of selective and open coding (Ellsberg and Heise Citation2005). Pre-determined themes explored in the questions were listed as coding categories and subcategories, which were modified in an iterative process as the coding took place, allowing for data comparisons and for themes to emerge from the data.

Results and discussion

A total of 305 households were visited, with a response rate of 89.18 per cent, resulting in 272 effective surveys. Thirty-nine per cent (106 women) expressed having experienced at least one type of violence within the year prior to the survey, with many reporting multiple incidents, yielding a combined total of 279 incidents of experienced violence (see and ). An additional 22.4 per cent (61 women) of respondents recounted incidents that took place more than a year prior to the survey, which included an additional 102 incidents of violence. According to the INEGI survey, 33.9 per cent of the women living in urban areas of Querétaro experienced violence in the public sphere within the year prior to the survey and 53.6 per cent throughout their life (INEGI Citation2016a). Some of the types of violence collected through the survey are crimes in and of themselves. Some involve actions which are not necessarily criminal in Mexico or elsewhere, such as offensive remarks or shaming someone for being a woman, and some of these types focus on the feelings or perceptions of the woman, rather than the intention or actions of another, such as when a woman fears what might happen. However, for the purposes of this study seeking to understand VAW from the perspective of women, each type was nonetheless considered violence.

Table 2. Number of women who experienced violence and number of incidents.

Table 3. Reported number of incidents women experienced (See for typologies).

The survey conducted for this research shows that the problem may be more widespread than previously thought. A total of 34 personal stories of harassment and violence were shared during the FGDs, which coincided with the most common types of violence identified in the HHS. Catcalling, stalking, groping, and flashing were the most common types of violence featured in the FGDs.

Catcall, whistling, or offensive sexual remarks. This type of violence was the most discussed in the FGDs. It seemed to be the most common aggression women from Corregidora experience when using public spaces. This type of violence ranged from remarks to more direct attacks that left women feeling unsafe and fearful, regardless of their background or age:

I was coming back from dropping off my kids at school and I go through a place that is a bit lonely. […] And a man, told me things like, I mean, horrible things. […] I felt, like, I mean, attacked. (Participant in FGD5)

There is a lack of trust in the authorities in Mexico, particularly for reporting gender crimes (Durán Citation2020; Melgoza, López, and Pigeonutt Citation2017). The high rates of impunity that permeate the country may encourage some people, particularly men, to commit acts of VAW knowing that the risk of being charged or facing justice is very slight. The results additionally showed that few women report incidents or are interested in doing so, due to low levels of trust in police and fears of being re-victimised by insensitive policing.

Younger participants provided insights to this problem from their experiences with security guards or police officers perpetrating harassment. A participant in FGD7 commented on how police officers act as perpetrators of this violence. A participant in FGD6 expressed having been told sexual remarks by a guard stating that “even the guards themselves tell you ‘goodbye mamacita [hot mama]’. I mean a guard cannot tell you that” (Participant in FGD6). This showcases an ineffective police culture that reflects the machismo that exists within the Mexican society.

During the HHS, data collectors noticed that almost all the women over 40 years of age seemed to mention they were not “young”, “teenagers”, “16, 17 or 20 years old” – the most commonly referred to ages – anymore, thus they did not experience catcalling. A participant in FGD4 provided a comment that captures these types of responses: “When I was young, I mean I am 49 years old, when I was 16 years old, […] they would tell you ‘ay mamacita [hot mama]’” (Participant in FGD4). Similarly, some women in other FGDs noted that once they became mothers, they no longer experienced this.

Regarding recurrence, discussions held in FGD3, FGD5, and FGD7 highlighted how all the participants had experienced catcalling. These groups had the youngest participants (apart from the participants in FGD6) with ages ranging from 18 to 33. As a participant in FGD5 described: “I think that at some point [it has happened] to all of us” (Participant in FGD5). Another participant stated that “the worst part is that they say it behind you, they don’t say it to your face” (Participant in FGD3). Additionally, in FGD3, a group mainly composed of mothers, there was a conversation among participants in which discussion included walking in the streets with their children and their children’s safety, as even when walking with their children, they are subjected to violence.

Catcalling is usually viewed as a less severe form of VAW and has generally been condoned and normalised. Some consequences of catcalling or whistling include the fear of being attacked and feeling more vulnerable to violence, and lead to women changing their behaviour (such as avoiding certain areas or avoiding walking alone) and moving less freely around the city (Kearl Citation2014; Wesely and Gaarder Citation2004). A number of studies have found that less severe forms of VAW remind women of the threat of other forms of violence (Koskela Citation1999; Natarajan et al. Citation2017).

Stalking. Many of the stories shared by the participants included a single, short instance of being followed through a street segment. Only one story, shared by a participant in FGD7, contained evidence of stalking. The participant was followed by a man for a month on her way to school. She told her family, classmates, and school about the incident. Her family and school representatives responded by not allowing her to go to or leave school on her own at any point. She reported the man to the police, who talked to him, but the participant claimed that the man “justified that he was going to do paperwork at that school, which is why he was going every day” (Participant in FGD7), which, in the participant’s view, was untrue, but the police did not check or follow up the story. It is unclear what the participant in FGD7 could have expected the police to do in a country that, regardless of specific laws for stalking (Gobierno de Mexico and INMUJERES Citation2014), has little history of their implementation (Ureste Citation2020). Stalking, as well as being followed, can have harmful psychological consequences for the victim, however short the incident is and regardless of the number of times it occurs. This impact should not be disregarded, as it may not necessarily be proportional to the length of the incident.

Fear. Participants held discussions regarding the daily fear that most of them experience. There were also discussions regarding how this fear influences their behaviour, and the different coping mechanisms and fear management strategies they adopt. Many participants also expressed the fear caused by constant, recurrent events of VAW, or induced by reports of VAW in news outlets and social media: “if you see in the news that I don’t know how many girls have been kidnapped and how they are killed and how they are found, well imagine, it […] induc[es] fear” (Participant in FGD7).

Women who experienced violence

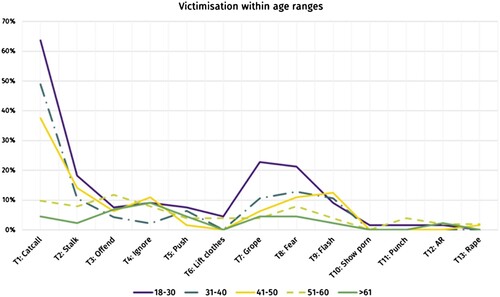

Younger women, particularly those within the age range of 18o to 30 years of age, seemed more likely to experience violence than other age groups, namely catcalling, stalking, groping, and fear of attack (see ). Women between the ages of 30 and 50 seemed to also be subjected to catcalling and stalking, although to a slightly lesser degree, while women over 61 years of age reported very low incidents of VAW in public spaces. The only exceptions were being ignored, humiliated, or the exposure of genitals and/or public masturbation, where the opposite trend was observed, and women in their forties to fifties reported having proportionally more incidents of this nature.

Figure 1. Number of respondents that experienced VAW per type per age group (18–30, N = 66; 31–40, N = 47; 41–50, N = 64; 51–60, N = 51; > 61, N = 44.)

Some studies have found that older women tend to report lower rates of physical and sexual violence, but the psychological or emotional violence does not show the same inverse relationship to age (Crockett, Brandl, and Dabby Citation2015; Pathak, Dhairyawan, and Tariq Citation2019). It is not clear whether these trends in victimisation stem from vulnerabilities associated with patriarchal power dynamics, aging, or a combination of both factors (Crockett, Brandl, and Dabby Citation2015). Younger participants may be more exposed to violence given their patterns of movement in comparison with older women. It is possible that younger women travel more and by themselves more often than older women in this context. As for women aged 26–40, they may be at work for longer periods of time, or with children, reducing their exposure to incidents of VAW in public spaces. Similarly, women above the age of 50 may not go out into public life as often, or at least not on their own, as expressed by some participants in the FGDs. The generational changes regarding talking about experiences of violence and the different views regarding VAW and its normalisation may be another explanation for this trend (Cook, Dinnen, and O’Donnell Citation2011).

A test for calculating the socioeconomic level of the participants was carried out; however, the results were inconclusive, particularly for the FGDs.

The normalisation of violence against women

The normalisation of everyday violence was a recurrent topic in all the FGDs; however, younger participants seemed more familiar and able to discuss it more articulately. It seemed that all the participants agreed that this is a reality faced by women in Mexico on a regular basis. When asked about their experiences of VAW, there were differences in how the participants in each group responded. There was a particular FGD (carried out with participants with the lowest socioeconomic level) in which participants did not seem to recognise less severe forms of VAW (such as catcalling) as “violence” per se. They required prompting to share personal stories, and some participants were visibly uncomfortable with the topic. This was noticeable in instances where women struggled to bring themselves to say words to describe VAW, which can be indicative of the social taboo that surrounds discussing sexual crimes, as well as the human body and bodily functions associated with reproduction and sexual health more generally. This reluctance to discuss personal incidents of VAW, or perhaps inability to recognise that what they had experienced could qualify as VAW, was contrasted with their willingness to describe incidents that occurred to someone else.

In contrast, during the FGD held with the youngest participants, who were mostly students of diverse socioeconomic levels, personal incidents of catcalling were shared within the first five minutes of the discussion (lasting 55 min) without prompting. The youngest participants seemed more familiar and able to discuss catcalling more articulately, regarding it as an act of violence, and while they were aware that these incidents could unfortunately be part of their everyday life, they did not think it was something they were obliged to endure or internalise as “normal” behaviour. According to Herrera and Agoff (Citation2018, 54), agency is a “capacity for action [to negotiate within power relations] created and made possible by specific relations of subordination, where resistance to the norms is only one of a number of options”. The authors further state that what can be seen as “passivity from a progressive viewpoint, can be a form of agency, since agency does not refer solely to actions that result in radical or even progressive changes, but can also apply to those that seek continuity and stability” (54). So, in this context, despite many of the younger participants having had experiences of violence, they were less willing internalise VAW as something that was just an inevitable part of their everyday life. This refusal to normalise VAW was evident in their awareness of the definition of catcalling and harassment, their sorority and knowledge of support services that exist to address VAW.

Perpetrators

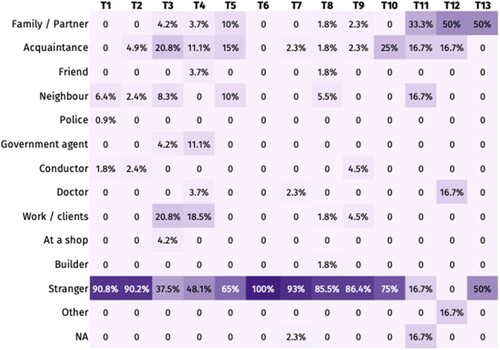

In 94.16 per cent (371 incidents) of the cases the perpetrator was a man; only 3.3 per cent (13 incidents) of the cases were perpetrated by a woman; while 1.27 per cent (five incidents) were carried out by both men and women, and an equal amount did not disclose, or could not recall who did it (see ).

In 2010, UN Women launched the global program Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces for Women and Girls Global Initiative (UN Women Citation2017). The program supports the development, implementation, and evaluation of tools, policies, and approaches for the prevention and response to VAW globally. In Mexico City, a campaign to tackle sexual harassment in public spaces aimed at men was launched. The campaign generated public debate on the topic, put the issue on the public agenda, and managed to change some men’s views about sexual harassment (UN Women Citation2019). Initiatives like this have the potential of being highly effective for communicating how social change can take place, including encouraging bystander intervention and questioning of myths justifying violent behaviours.

Stakeholders’ perceptions of violence against women

The focus of the interviews was to understand if there were protocols in place to mitigate VAW at any point in the process of planning and delivery of infrastructure. The stakeholder interviews indicated that, at the time, the local government stakeholders were not aware of any gender protocols in place for planning or delivering infrastructure or for dealing with gender issues within the local government. None of the stakeholders seemed to know of any set of criteria for the design of public infrastructure to minimise the risk of VAW. There also seemed to be a limited understanding of the term gender perspective, as illustrated by this response of a man government stakeholder, who stated that:

There is always a gender perspective, because if we carry out a social [public] work – a park – there are security considerations. More than gender [perspectives] these [considerations] are for security for people. (Stakeholder two, Man, Government Employee)

Now statistics are being recorded. […] beaten women, raped and everything, has always existed in this country. But if you don't have them [statistics], what do you compare against? So today is a lot, it's a little, I don't know. (Stakeholder five, Woman, Government Employee)

During interviews with government agents, a woman stakeholder mentioned that the working environment within the municipality still faced gender inequality and stated that “the gender issue here is still very biased, I think. There is still a lot of machismo, but there are no protocols for that” (Stakeholder seven, Woman, Government Employee).

Other relevant interactions during data collection include the police’s denial to a request for collaboration, and a denial to a request to use the logo of the local government for research purposes on the grounds that “by allowing the use of the logo of the municipality, the local government was accepting that there is violence against women” (Anonymous, personal oral communication, 21 November 2018).

There was a disconnect between the experiences of violence of women in public spaces and the views, knowledge, and interest on the subject by the stakeholders working at the municipal government. The municipality’s resistance to investigate and prioritise the reduction of VAW could be explained by social attitudes, as revealed through the interactions with the municipality throughout the research. Women’s freedom from violence and physical security is directly related to the material basis of the relationships that control the use and distribution of entitlement, resources, and authority within a community and the state (Ertürk and Purkayastha Citation2012). If a state facilitates violence by addressing it in limited ways, a culture of violence is produced, which can normalise the escalation of violence in everyday life (Purkayastha and Ratcliff Citation2014).

Conclusions

The urban space of Corregidora Municipality in Mexico was used as a case study to investigate Violence Against Women (VAW) in public spaces and women’s experiences through a mixed-methods approach. Two-hundred and seventy-two surveys, seven FGDs with 50 participants, and seven stakeholder interviews were conducted. It was found that the most common and recurrent type of VAW women experience in Corregidora, Mexico is catcalling, with 35.5 per cent of the survey participants experiencing this type of violence over the year prior to the survey, and most FGD participants sharing stories of this nature. Participant accounts indicated that they perceived several incidents as being VAW which may not be recognised as such by state or national laws or might not have been reported to law enforcement. Local government stakeholders were not aware of the figures of this violence, nor of gender protocols for the planning or delivery of infrastructure that would reduce the risk of VAW in public spaces. It was also found that there was a lack of regard for women’s lives and right to participate fully in the social fabric of Corregidora, which is possibly driven by impunity in the criminal system, but also by the normalisation of VAW in everyday life. Key recommendations include recognising less severe types of VAW as crimes, the inclusion of gender perspectives into planning and infrastructure delivery, as well as better prevention and response strategies to VAW, which do not re-victimise, stigmatise, or discourage victims who wish to come forward. Prevention strategies could integrate the way in which women and girls use public spaces, including mechanisms for their participation in decision-making and co-production in the design of spaces. There is a need for more public education and discussion about patriarchy and men’s entitlement, such as the sexual objectification and intimidation of women and girls in public. Another key recommendation includes the need for interventions at community and institutional levels which address and open discussions to disrupt norms and taboos regarding sexual and reproductive health. It is essential to engage men, particularly young and middle-aged men, to facilitate dialogues and messaging about respectful behaviour and the need to challenge societal views towards VAW and harassment of women and girls in public spaces. Such interventions, however, need to be undertaken in a context-sensitive way which creates safe spaces for women to openly discuss and reflect on these subjects.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants for sharing their views and stories as, without their answers, this work would not be possible. We thank Fernanda Martinez, the research assistant who supported the facilitation and transcription of the focus group discussions. We would also like to thank CONACYT Mexico for funding this research. Margarita Garfias Royo: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Julian Walker, Jyoti Belur: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing. Priti Parikh: Conceptualisation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – Review & Editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bautista, Nidia. 2017. “Justice for Lesvy: Indifference and Outrage in Response to Gender Violence in Mexico City.” North American Congress on Latin America, 31 July 2017. https://nacla.org/news/2017/07/31/justice-lesvy-indifference-and-outrage-response-gender-violence-mexico-city.

- Bianchi Alves, Bianca, and Karla Dominguez Gonzales. 2015. “Smart Measures in Transport: Moving beyond Women’s-Only Buses.” World Bank Blog, 2015. http://blogs.worldbank.org/transport/smart-measures-transport-moving-beyond-women-s-only-buses.

- CEAV. 2016. Primer Diagnóstico sobre la atención de la violencia sexual en México. Mexico City: Comisión Ejecutiva de Atención a Víctimas (CEAV). https://www.gob.mx/ceav/documentos/primer-diagnostico-sobre-la-atencion-de-la-violencia-sexual-en-mexico.

- Cook, Joan M, Stephanie Dinnen, and Casey D O’donnell. 2011. “Older Women Survivors of Physical and Sexual Violence: A Systematic Review of the Quantitative Literature.” Journal of Women’s Health 20 (7): 1075–1081. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2279.

- Crockett, Cailin, Bonnie Brandl, and Firoza Chic Dabby. 2015. “Survivors in the Margins: The Invisibility of Violence Against Older Women.” Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect 27 (4-5): 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2015.1090361.

- de Corregidora, Ayuntamiento. 2019a. “Lineamientos Que Emite La Secretaría de Administración a Través de Los Cuales Se Regula El Uso de Parques y Jardines Para El Municipio de Corregidora, Qro.” Gaceta Municipal La Pirámide, 31 May 2019. https://www.corregidora.gob.mx/Documentos/2018–2021/Transparencia/art67/VIII/2019/Mayo/Gaceta_No_31_31_mayo_2019.pdf.

- de Corregidora, Ayuntamiento. 2019b. “Reglamento Del Sistema Municipal de Acceso de Las Mujeres a Una Vida Libre de Violencia y Para La Igualdad Sustantiva Entre Mujeres y Hombres.” Gaceta Municipal La Pirámide, 30 August 2019. https://www.corregidora.gob.mx/Documentos/2018–2021/Transparencia/art67/VIII/2019/Agosto/Gacet_No_34_30_agosto_2019.pdf.

- de Corregidora, Ayuntamiento. 2019c. “Reglamento Del Sistema de Consejos de Participación Ciudadana Municipal de Corregidora, Qro.” Gaceta Municipal La Pirámide, 31 December 2019. https://www.corregidora.gob.mx/Documentos/2018-2021/Transparencia/art67/VIII/2019/Diciembre/Gaceta_No_40_TomoIII_31_diciembre_2019.pdf.

- Durán, Valeria. 2020. “Feminicidas Libres.” https://contralacorrupcion.mx/feminicidas-libres/#met1.

- Ellsberg, Mary, and Lori Heise. 2005. Researching Violence Against Women: A Practical Guide for Researchers and Activists. Washington DC, U.S: World Health Organisation.

- Ertürk, Yakın, and Bandana Purkayastha. 2012. “Linking Research, Policy and Action: A Look at the Work of the Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women.” Current Sociology 60 (2): 142–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392111429216.

- Frías, Sonia M. 2016. “Violentadas.” Nexos, 1 June 2016. https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p = 28501.

- Garfias Royo, Margarita, Priti Parikh, and Jyoti Belur. 2020. “Using Heat Maps to Identify Areas Prone to Violence Against Women in the Public Sphere.” Crime Science 9 (1): 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-020-00125-6.

- Garrido, Arancibia, Marco Billi Javiera, and María José Guerrero González. 2017. “¡Tu “Piropo” Me Violenta! Hacia Una Definición de Acoso Sexual Callejero Como Forma de Violencia de Género.” Revista Punto Género 7: 112–137. https://doi.org/10.5354/2735-7473.2017.46270

- Gobierno de Mexico, and INMUJERES. 2014. “Legislación Penal En Las Entidades Federativas: Acoso Y Hostigamiento Sexual.” https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/48374/Acoso_y_Hostigamiento_Sexual-2014.pdf.

- Herrera, Cristina, and María Carolina Agoff. 2018. “The Intricate Interplay Between Victimization and Agency: Reflections on the Experiences of Women Who Face Partner Violence in Mexico.” Journal of Research in Gender Studies 8 (1): 49–72. https://doi.org/10.22381/JRGS8120183.

- INEGI. 2010. “Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010: Principales Resultados Por AGEB y Manzana Urbana.” http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/ccpv/cpv2010/iter_ageb_manzana_2010.aspx.

- INEGI. 2015. “Encuesta Intercensal 2015.” http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/enchogares/especiales/intercensal/.

- INEGI. 2016a. “Encuesta Nacional Sobre La Dinámica de Las Relaciones En Los Hogares (ENDIREH).” Instituto National de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/proyectos/enchogares/especiales/endireh/2016/.

- INEGI. 2016b. “Inventario Nacional de Viviendas (INV).” Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/inv/.

- INEGI. 2021. “Encuesta Nacional Sobre La Dinámica de Las Relaciones En Los Hogares (ENDIREH) 2021.” https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/endireh/2021/.

- INEGI. 2022. “Encuesta Nacional Sobre La Dinámica de Las Relaciones En Los Hogares (ENDIREH) 2021.” Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/endireh/2021/.

- Johnson, Holly. 2006. “Measuring Violence Against Women: Statistical Trends 2006.” 85-570-XWE. Ottawa. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-570-x/85-570-x2006001-eng.htm?contentType = application%2Fpdf.

- Kandiyoti, Deniz. 2016. “Locating the Politics of Gender : Patriarchy, Neo- Liberal Governance and Violence in Turkey.” Research and Policy on Turkey 1 (2): 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/23760818.2016.1201242.

- Kearl, Holly. 2014. “Unsafe and Harassed in Public Spaces: A National Street Harassment Report.” Reston, Virginia. http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/2014-National-SSH-Street-Harassment-Report.pdf.

- Koskela, Hille. 1999. “‘Gendered Exclusions”: Women’s Fear of Violence and Changing Relations to Space.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 81 (2): 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.1999.00052.x.

- Krantz, Gunilla, and Claudia Garcia-Moreno. 2005. “Violence Against Women.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59 (10): 818–821. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.022756.

- Lakhani, Nina. 2016. ““Impunity Has Consequences”: The Women Lost to Mexico’s Drug War.” The Guardian, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/08/mexico-drug-war-cartels-women-killed.

- Leclerc, Benoit, Yi Ning Chiu, Jesse Cale, and Alana Cook. 2016. “Sexual Violence Against Women Through the Lens of Environmental Criminology: Toward the Accumulation of Evidence-Based Knowledge and Crime Prevention.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 22 (4): 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610–015–9300-z.

- Lecuona, Zepeda, and Guillermo Raúl. 2017. “Índice Estatal de Desempeño de Las Procuradurías y Fiscalías.” Mexico City. http://www.impunidadcero.org/uploads/app/articulo/49/contenido/1510005056X78.pdf.

- Levy, Caren. 2013. “Travel Choice Reframed: “Deep Distribution” and Gender in Urban Transport.” Environment and Urbanization 25 (1): 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813477810.

- Lindsey, Linda L. 1997. Gender Roles: A Sociological Perspective. 3rd ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- McIlwaine, Cathy. 2013. “Urbanization and Gender-Based Violence: Exploring the Paradoxes in the Global South.” Environment and Urbanization 25 (1): 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813477359.

- Mechanic, Mindy B, Terri L Weaver, and Patricia A Resick. 2000. “Intimate Partner Violence and Stalking Behaviour: Exploration of Patterns and Correlates in a Sample of Acutely Battered Women.” Violence and Victims 15 (1): 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.15.1.55

- Melgoza, Alejandro, Marco Antonio López, and Vania Pigeonutt. 2017. “Se Duplican Asesinatos de Mujeres En La Última Década (Reportaje e Informe).” Aristegui Noticias, 13 December 2017. https://aristeguinoticias.com/1312/mexico/se-duplican-asesinatos-de-mujeres-en-la-ultima-decada-reportaje-e-informe/?utm_source = hootsuite&utm_medium = redes&utm_campaign = aristeguinoticiasredes.

- Mobayed Vega, Saide. 2022. “Día Internacional de La Eliminación de La Violencia Contra La Mujer.” In Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas (IIJ), edited by Alethia Fernández de la Reguera and Fabiola de Lachica Huerta, 53–85. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. https://www.un.org/es/observances/ending-violence-against-women-day%0Ahttps://www.un.org/es/observances/ending-violence-against-women-day%0Ahttps://www.un.org/es/observances/ending-violence-against-women.

- Natarajan, Mangai, Margaret Schmuhl, Susruta Sudula, and Marissa Mandala. 2017. “Sexual Victimization of College Students in Public Transport Environments: A Whole Journey Approach.” Crime Prevention and Community Safety 19 (3-4): 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-017-0025-4.

- Noticias, Aristegui. 2022. ““México Feminicida”: Con Leyendas Gigantes Protestan Contra Violencia En Monterrey y Guadalajara.” Aristegui Noticias, 5 September 2022. https://aristeguinoticias.com/0509/mexico/con-letreros-gigantes-de-mexico-feminicida-protestan-contra-violencia-en-monterrey-y-guadalajara/.

- ONU Mujeres, Inmujeres and Ministry of the Interior of Mexico. 2017. La Violencia Feminicida En México: Aproximaciones y Tendencias 1985-2016. Mexico City: ONU Mujeres, Inmujeres and SEGOB. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/293666/violenciaFeminicidaMx_07dic_web.pdf.

- O Nyumba, Tobias, Kerrie Wilson, Christina J. Derrick, and Nibedita Mukherjee. 2018. “The Use of Focus Group Discussion Methodology: Insights from Two Decades of Application in Conservation.” Methods in Ecology and Evolution 9 (1): 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12860.

- Parkes, Jenny. 2015. “Theory and Diagnostics: Introduction.” In Gender Violence in Poverty Contexts: The Education Challenge, edited by Jenny Parkes, 3–10. Oxon: Routledge.

- Pathak, Neha, Rageshri Dhairyawan, and Shema Tariq. 2019. “The Experience of Intimate Partner Violence among Older Women: A Narrative Review.” Maturitas 121 (March): 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.12.011.

- Poder Legislativo del Estado de Querétaro. 2022. Código Penal Para El Estado de Querétaro. México: Querétaro.

- Purkayastha, Bandana, and Kathryn Strother Ratcliff. 2014. “Routine Violence: Intersectionality at the Interstices.” Gendered Perspectives on Conflict and Violence: Part B, Advances in Gender Research 18: 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1529-21262014000018B005.

- Rodriguez Ferreira, Octavio. 2016. “Violent Mexico: Participatory and Multipolar Violence Associated with Organised Crime.” International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV) 10 (1): 40–60. https://doi.org/10.4119/UNIBI/IJCV.395.

- Rubio Gutiérrez, Harmida. 2022. “Ciudad Equitativa? La Legislación Urbana Veracruzana y Las Mujeres En La Ciudad.” UVserva 14: 165–180. https://doi.org/10.25009/uvs.vi14.2882.

- Saguy, Abigail C. 2003. What Is Sexual Harassment? Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Scott, Adrian J, Nikki Rajakaruna, Lorraine Sheridan, Jeff Gavin, and Sellenger Centre. 2015. “International Perceptions of Relational Stalking: The Influence of Prior Relationship, Perpetrator Sex, Target Sex, and Participant Sex.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 30 (18): 3308–3323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514555012.

- Segura Amaro, Paco. 2022. “Colectivo Pide Reconocer y Tipificar El Acoso Callejero En Querétaro.” Vía Tres, 30 July 2022. https://www.viatres.com.mx/queretaro/2022/7/30/colectivo-pide-reconocer-tipificar-el-acoso-callejero-en-queretaro-11072.html.

- Sinha, Maire. 2013. Measuring Violence Against Women: Statistical Trends. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- Soto Villagrán, Paula. 2018. “Hacia La Construcción de Unes Geografías de Género de La Ciudad: Formas Plurales de Habital y Significar Los Espacios Urbanos En Latinoamérica.” Revista Perspectiva Geográfica 23 (2): 13–31.

- Soto Villagrán, Paula. 2020. “Construcción de Ciudades Libres de Violencia Contra Las Mujeres. Una Reflexión Desde América Latina.” Cuadernos Manuel Giménez Abad, March 2020.

- SSNSP. 2023. Contra Las Mujeres Incidencia Delictiva y Llamadas de Tema Página. Mexico City: Secretariado Ejecutivo del Sistema Nacional de Seguridad Ciudadana (SSNSP). http://secretariadoejecutivo.gob.mx/docs/pdfs/nueva-metodologia/Info_violencia_contra_mujeres_DIC2018.pdf.

- UN. 1993. “Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women.” UN OHCHR.

- UN Women. 2017. Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces. New York. http://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2017/safe-cities-and-safe-public-spaces-global-results-report-en.pdf?la = en&vs = 45.

- UN Women. 2019. Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces for Women and Girls Global Initiative: Global Results Report 2017–2020. New York. https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2021/07/safe-cities-and-safe-public-spaces-global-results-report-2017-2020.

- Ureste, Manu. 2020. “Casi El 100% de Los Casos de Acoso y Hostigamiento Sexual En Contra de La Mujer Queda Impune: Red TDT.” Animal Politico, 4 March 2020. https://www.animalpolitico.com/2020/03/casos-acoso-hostigamiento-sexual-mujeres-impunidad-redtdt/.

- Villegas, Paulina. 2020. “Las Mujeres de México Toman Las Calles Para Protestar Contra La Violencia.” The New York Times, 10 March 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/es/2020/03/10/espanol/mexico-paro-mujeres-protestas.html.

- Wattenbarger, Madeleine. 2020. “Mexican Women’s Patience Snaps at Amlo’s Inaction on Femicide.” The Guardian, 16 September 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/sep/16/mexico-women-activists-human-rights-commission-protest.

- Wesely, Jennifer K, and Emily Gaarder. 2004. “The Gendered “Nature” of the Urban Outdoors: Women Negotiating Fear of Violence.” Gender and Society 18 (5): 645–663. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204268127.

- WHO. 2001. Putting Women First. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb1402

- WHO. 2007. WHO Ethical and Safety Recommendations for Researching, Documenting and Monitoring Sexual Violence in Emergencies. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO. 2012. Understanding and Addressing Violence against Women: Intimate Partner Violence. Geneva. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77432/1/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf.

- Women, UN. 2023. “Global Database on Violence against Women: Mexico.” https://evaw-global-database.unwomen.org/en/countries/americas/mexico.