Abstract

Understanding food sustainability and healthy diets public awareness is of utmost importance since consumers are the main drivers of global consumption patterns. Using Google Trends data, from 2010 to 2021, we aim to explore the temporal dynamics of food sustainability public interest across Europe and its association with interest in sustainability, healthy diet, Mediterranean diet (MedDiet), and flexitarianism. Public interest in food sustainability has increased and is positively associated with the interest in the topic of sustainability. With few exceptions, no general association between food sustainability and healthy diet or MedDiet interest were found. Consistent associations between food sustainability and flexitarianism were found across most of the European regions and countries. Despite the growing interest, only flexitarianism seems to be associated with food sustainability. Understanding consumers’ interest in food sustainability is crucial for the transition towards healthy and sustainable diets and to define educational and behavioural interventions.

Introduction

In 2010, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), in collaboration with Bioversity International, reached a scientific consensus on the definition of sustainable diets: “Sustainable diets are those diets with low environmental impacts which contribute to food and nutrition security and to healthy life for present and future generations. Sustainable diets are protective and respectful of biodiversity and ecosystems, culturally acceptable, accessible, economically fair and affordable; nutritionally adequate, safe, and healthy; while optimising natural and human resources” (Burlingame and Dernini Citation2012). Recently, the EAT-Lancet Commission identified food as the single strongest lever to optimise human health and environmental sustainability on Earth (Willett et al. Citation2019).

Current dietary patterns of consumption are greatly contributing to increasing global incidences of chronic diseases. At the same time, they cause significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and contribute to land clearing. Therefore, food and dietary choices are a relevant link in environmental sustainability and human health (Tilman and Clark Citation2014). In high and middle-income countries adoption of sustainable diets can result in concurrent reductions in environmental and health detrimental impacts; while, on the other hand, the adoption of sustainable diets in low-income countries may result in greater resource expenditure and limit sustainability (Springmann et al. Citation2018). The existence of a significant overlap between health promoting and environmentally sustainable diets does not mean that they are mutually inclusive, since nutritionally adequate diet can have a high environmental impact and a diet with low GHG emissions may also be nutritionally deficient (Macdiarmid Citation2013; Culliford and Bradbury Citation2020). Even though healthier diets are not necessarily more environmentally beneficial, and environmentally beneficial diets are not necessarily healthier, there are many dietary patterns that may be positive for both human and environmental health (Tilman and Clark Citation2014).

The assessment of the sustainability of diets has received a sizable amount of research attention in the last decade, with most of the research conducted in the field having been undertaken since 2006 (Jones et al. Citation2016) and, specifically, research on the sustainability of MedDiet since 2012 (Portugal-Nunes et al. Citation2021). Since its identification, MedDiet has been considered a healthy diet. Evidence suggests that adherence to the MedDiet is associated with a reduced risk of overall mortality, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, overall cancer incidence, neurodegenerative diseases, and diabetes (Dinu et al. Citation2018). MedDiet has also been a recognised example of a sustainable diet (Burlingame and Dernini Citation2011; Dernini and Berry Citation2015).

Animal-source foods are the largest contributors to the unsustainable nature of the current food production system, therefore, proposal on sustainable diets have focussed on the reduction of meat and dairy products (Macdiarmid Citation2013; Parodi et al. Citation2018; Willett et al. Citation2019). Reduction on meat consumption may result in greater sustainability, health benefits, and reduction of disease burden (Yip et al. Citation2013), indicating that sustainable and healthy diets may go hand in hand. Considering the diet–environment–health trilemma, the EAT-Lancet report recommends that there is a need for an “healthy reference diet”, also referred to as a “flexitarian” diet (Lawrence et al. Citation2019; Willett et al. Citation2019). On this, flexitarian diet is considered one of the most environmentally friendly dietary patterns due to its GHG mitigation potential, being only supplanted by vegan and vegetarian diet and supplant healthy diet and MedDiet (IPCC Citation2019). While healthy diet and MedDiet include meat consumption in moderate amounts, a flexitarian diet limits the consumption of meat and dairy (Derbyshire Citation2017; Cena and Calder Citation2020).

Consumers are relevant players shaping the food systems (Outlaw and Smith Citation2001; Arnalte-Mur et al. Citation2020; van Bussel et al. Citation2022), and while the academic interest on this topic is clear, the public/consumers interest seems to be overlooked (Macdiarmid et al. Citation2016). Human behaviour affects, and may even drive, the future of global sustainability (Ilieva and McPhearson Citation2018). Consumers, through their choices in terms of type of products, quantity, and quality (including production and preparation modes), direct the sustainability of food systems (van Bussel et al. Citation2022). Drivers of consumers choices may include the social norm effect, self-efficacy (perceived behavioural control), and various other dimensions, such as health, environment, economic, social, and cultural. Moreover, consumers’ choices are, among other factors, directed by the information that they seek and is made available to them (Meybeck and Gitz Citation2017; Eker et al. Citation2019). Food sustainability is a characteristic that is not apparent before acquisition of food and it is not experienced during and after its consumption; therefore, information must be sought out, or provided, to allow informed decision making (Van Loo et al. Citation2017). Nonetheless, despite being a central piece in the consumer decision making process, information provision is not a sufficient factor to be translated into actions, such as healthy and sustainable food choices, known as the attitude-behaviour gap (O'Rourke and Lollo Citation2015; Van Loo et al. Citation2017).

In recent years, tools have emerged to facilitate research in Big Data, whose applications include supporting groups and organisations in understanding social changes and make predictions (Nuti et al. Citation2014; Jun et al. Citation2018). The data that is accumulated during internet search activities is one form of Big Data that may provide valuable insights and information into population behaviour and interests. One tool that allows users to interact with Internet search data is Google Trends, a free, publicly accessible online portal of Google Inc. Google Trends analyses a representative portion of the three billion daily Google searches (Nuti et al. Citation2014). The analysis of internet search queries offers information on the extent of public attention, thereby indicating the level of public awareness. Google Trends has been used in many research publications to analyse users’ interests across various fields (Jun et al. Citation2018).

Understanding the public interest and demand for information on food sustainability and dietary patterns is paramount to understand the availability and susceptibility of consumers to change towards healthy and sustainable food systems. In this study, we use an infodemiological approach to explore the trends of public interest in food sustainability, sustainability, and healthy dietary patterns, such as the MedDiet and flexitarianism, in several European countries. We also explore the correlates of food sustainability interest with the interest in general sustainability, healthy diet, MedDiet, and flexitarianism, in each country.

Methods

Google trends tool

Google trends (https://trends.google.com/trends/) is an online tool that estimates relative search volume (RSV) of queries conducted using the Google search engine. The tool allows the analysis of a chosen phrase, in a selected region and period, since January 2004. RSV is an index of search volume adjusted to the number of Google users in a given geographic area and time interval. RSV ranges from 0 to 100, where the value of 100 indicates the peak of popularity (100% of popularity in given period and location) and 0 complete disinterest (0% of popularity in given period and location) (Nuti et al. Citation2014; Kamiński et al. Citation2020).

Google trends may qualify analysed phrases as “search term” or “topic.” Search terms are literally typed words, whereas topics may be proposed by Google Trends when the tool recognises phrases related to popular queries. Topics enable easy comparison of the given term between countries. For example, the search term “London” will be analysed by Google Trends exactly; thus, RSV will be the highest in English-speaking countries, whereas the topic “London” will include all queries associated with the query in all available languages, for example, “Capital of the United Kingdom” and “Londres” (in Portuguese and Spanish, meaning “London”) (Kamiński et al. Citation2020).

It is important to note that none of the searches in the Google database for this study can be associated with a particular individual. The database does not retain information about the identity, IP address, or specific physical location of any user.

Google accounts for >80% of global search engine use (Search engine market share Citation2022), and Google Trends is one of the few open sources of search query data. Google Trends is considered a valid and robust indicator to track interest, attention, and public opinion, over time (Zhu et al. Citation2012; Anderegg and Goldsmith Citation2014), and has been increasingly used to quantify trends in public interest in several fields such as health care (Nuti et al. Citation2014; Mavragani et al. Citation2018), tourism (Bangwayo-Skeete and Skeete Citation2015), and economics (Preis et al. Citation2013; Preis et al. Citation2010).

Strengths and advantages of Google trends are evident; nevertheless, this tool also present limitations. Due to time and geographical normalisation, we can only compare relative popularity, meaning that different regions that show the same RSVs for a term or topic will not always have the same total search volumes. Other limitations include that not everyone uses the Internet and internet use may be higher in younger individuals; therefore, Google trends data may not be fully representative of the population and may present a selection bias (Fondeur and Karamé Citation2013; Palma Lampreia Dos Santos Citation2018).

Google trends data

The Google Trends tool was used in January 2022 to retrieve data on internet user search activities regarding food sustainability, sustainability, healthy diet, MedDiet, and flexitarianism, as a proxy measure for public interest in these subject matters. Healthy diet, MedDiet and flexitarianism were chosen both due to their reported associations with sustainability and because do not exclude food groups (IPCC Citation2019).

Google Trends RSVs were retrieved from January 2010 to December 2021. Searches were performed independently for each country with the following filters: “Country”, in “All Categories” and for “Web Searches”. Sustainability, healthy diet, MedDiet and flexitarianism were searched as topics. Since no food sustainability related topic was available, individual search terms combined in a query were used, as listed in , in the official language of each country.

Table 1. Google Trends search query for food sustainability.

Google Trends RSVs for Portugal, Spain, Italy, Turkey, the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark were retrieved. No Google Trends RSVs could be retrieved for other European countries (for food sustainability). Data was analysed independently for each country and used to compute mean values for European regions and Europe.

Statistical analyses

Based on monthly data, annual average Google Trends RSVs were calculated. Due to data nature, non-parametric tests were used as a conservative approach. Jonckheere–Terpstra test was used to determine if there was a statistically significant trend of RSVs for food sustainability, sustainability, healthy diet, MedDiet and flexitarianism across time. The Kendall’s Tau correlation coefficient was used to determine pairwise correlations between food sustainability RSVs and RSVs for sustainability, healthy diet, MedDiet and flexitarianism. SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) was used for data processing and analysis. Results were considered statistically significant if p<.05.

Results

Changes in google trends RSVs for food sustainability

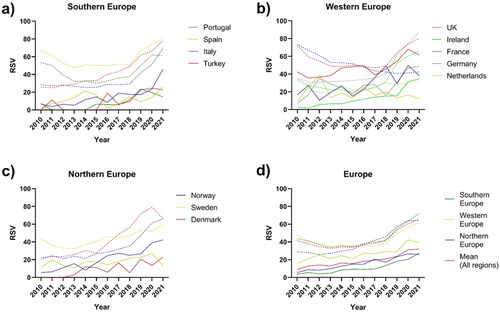

presents the Jonckheere-Terpstra trend analysis for the change in the RSVs across time. Between 2010 and 2021, the mean European RSV for food sustainability significantly increased from 8.98 to 31.94 (255.76% increase; ZJT = 7,798; p<.001). Similar results were observed for the European regions analysed: in Southern European countries (Portugal, Spain, Italy and Turkey) increased from 3.48 to 27.29 (684.43% increase; ZJT = 7.054; p<.001); in Western European countries (United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Germany and the Netherlands) from 15.52 to 39.20 (152.63% increase; ZJT = 5.551; p<.001); and in the Northern European countries (Norway, Sweden and Denmark) from 5.42 to 26.06 (381.03% increase; ZJT = 5.423; p<.001). Apart from the Netherlands (ZJT = −0.774; p = .439) and Sweden (ZJT = 1.239; p = .216), the remaining analysed European countries presented significant increases in the RSVs for food sustainability. Briefly, Portugal presented 104.60% increase (7.25–14.83), Italy presented 585% increase (6.67–45.67), the United Kingdom presented 44.99% increase (42.42–61.50), Ireland presented 1341.38% increase (2.41–42.83), France presented a 131.82% increase (16.5–38.25), Germany presented 597.62% increase (7–48.83), and Norway presented 656.72% increase (5.58–42.25). Due to the reduced number of searches using the search terms that compose the search query for food sustainability the 2010 RSVs for Spain, Turkey and Denmark were 0, therefore no % of change was calculated for these countries. For these, in 2021 the RSVs were 26, 22.67 and 22.92, respectively. The graphical representation of annual evolution of RSV for food sustainability can be observed in as full lines.

Figure 1. RSVs evolution for food sustainability and sustainability. (a) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and sustainability (dotted lines) in Southern European countries; (b) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and sustainability (dotted lines) in Western European countries; (c) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and sustainability (dotted lines) in Northern European countries; (d) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and sustainability (dotted lines) in Europe (mean) and European regions (mean for country regions).

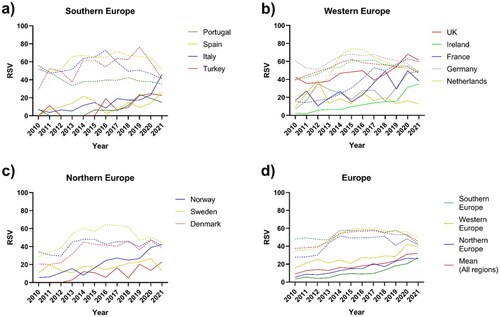

Figure 2. RSVs evolution for food sustainability and heathy diet. (a) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and healthy diet (dotted lines) in Southern European countries; (b) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and healthy diet (dotted lines) in Western European countries; (c) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and healthy diet (dotted lines) in Northern European countries; (d) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and sustainability (dotted lines) in Europe (mean) and European regions (mean for country regions).

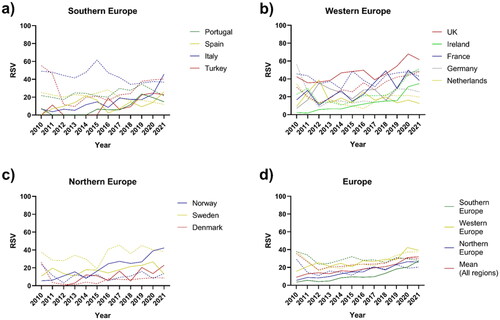

Figure 3. RSVs evolution for food sustainability and MedDiet. (a) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and MedDiet (dotted lines) in Southern European countries; (b) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and MedDiet (dotted lines) in Western European countries; (c) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and MedDiet (dotted lines) in Northern European countries; (d) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and MedDiet (dotted lines) in Europe (mean) and European regions (mean for country regions).

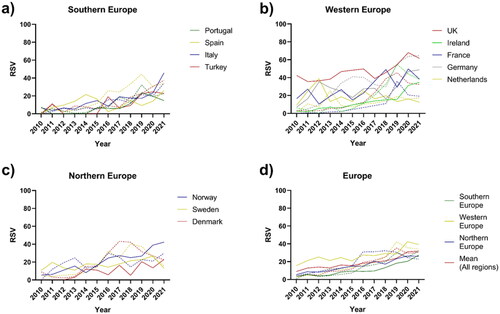

Figure 4. RSVs evolution for food sustainability and flexitarianism. (a) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and flexitarianism (dotted lines) in Southern European countries; (b) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and flexitarianism (dotted lines) in Western European countries; (c) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and flexitarianism (dotted lines) in Northern European countries; (d) RSVs evolution for food sustainability (full lines) and flexitarianism (dotted lines) in Europe (mean) and European regions (mean for country regions).

Table 2. Jonckheere-Terpstra trend analysis for RSVs from 2010 to 2021.

Changes in google trends RSVs for sustainability

shows the evolution of RSVs for the sustainability topic as dotted lines and the evolution of food sustainability as full lines. A positive significant trend was observed for the interest in sustainability in general in European countries. The mean RSV value for European countries increased by 58.03% from 2010 to 2021 (41.49–58.03; ZJT = 6.305; p<.001). The highest mean relative increase was observed for the Northern European countries with an increase of 121.79% (28.81–63.89; ZJT = 9.122; p<.001), followed by the Southern European countries with a 64.51% increase (43.73–71.94; ZJT = 5.678; p<.001), while the lowest mean increase was observed for the Western European countries with an increase of 29.94% (47.32–61.48; ZJT = 3.631; p<.001).

Regarding the interest in the topic of sustainability, apart from France, which had a significant decrease of 42% was observed for France (73.42–42.58; ZJT = −7.876; p<.001), all the analysed countries presented a significant increase. Briefly, Portugal presented 15% increase (53.33–61.33, ZJT = 2.227; p = .026), Spain 18.22% (67.25–79.5; ZJT = 2.877; p = .004), Italy 142.11% (28.5–69; ZJT = 6.362; p<.001), Turkey 201.6% (25.83–77.92; ZJT = 10.188; p<.001), the United Kingdom 10.82% (72.42–80.25; ZJT = 2.315; p = .021), Ireland 94.81% (33.75–65.75; ZJT = 5.940; p<.001), Germany 146.81% (35.25–87; ZJT = 9.428; p<.001), the Netherlands 46.36% (21.75–31.83; ZJT = 6.348; p<.001), Norway 220.24% (20.58–65.92; ZJT = 8.205; p<.001), Sweden 36.20% (43.5–59.25; ZJT = 4.840; p<.001), and Denmark 197.76% (22.33–66.5; ZJT = 10.832; p<.001).

Changes in google trends RSVs for healthy diet

Evolution of RSVs for the healthy diet topic is shown in as dotted lines and the evolution of food sustainability as full lines. A general positive significant trend was observed for the interest in healthy diet in European countries, with the mean RSV value increasing by 20.65% from 2010 to 2021 (37.60–45.37; ZJT = 4.472; p<.001). The highest mean relative increase was observed for the Northern European countries with an increase of 49.45% (27.81–41.56; ZJT = 4.273; p<.001), followed by Western European countries with a 42.27% increase (35.25–50.15; ZJT = 6.076; p<.001). Namely, in the Western European countries, Ireland presented a significant 22.08% increase (40–48.83; ZJT = 3.092; p = .002), France presented a significant increase of 293.41% (15.17–59.67; ZJT = 12.080; p<.001) and the Netherlands presented 122.83% increase (21.17–47.17; ZJT = 4.685; p<.001). No significant changes over time were observed for the United Kingdom and Germany (ZJT = 1.943; p = .052 and ZJT = −0.245; p = .807). In the Northern European region, Sweden presented 57.73% increase (28.58–45.08; ZJT = 2.839; p = .005) and Denmark presented 86.69% increase (20.67–38.58; ZJT = 5.013; p<.001). No significant changes were observed for Norway (ZJT = 1.932; p = .053). On the other hand, the mean RSV for the healthy diet topic in the Southern European countries did not present significant changes over time (47.90–42.25; ZJT = .515; p = .607). Specifically, Portugal presented a significant decrease of 37.01 (55.83–35.17; ZJT = −2.280; p = .023), Italy did not present a significant change over time (52–42.25; ZJT = −1.588; p = .112), Turkey presented a significant increase of 40.69% (ZJT = 3.011; p = .003 respectively), and Spain, despite a negative variation of 5.49% (54.67–51.67), presented positive trend over time (ZJT = 2.066; p = .039).

Changes in google trends RSVs for MedDiet

Evolution of RSVs for the MedDiet diet topic is shown in as dotted lines and the evolution of food sustainability as full lines. A general positive significant trend was observed for the interest in MedDiet in European countries (ZJT = 2.105; p = .035), despite the mean RSV value decrease of 16.30% from 2010 to 2021 (35.70–29.88). Considering the European regions under analysis, only Western Europe presented a significant positive trend, despite that no discernible variations could be observed when comparing 2010 and 2021 (37.93–37.47; ZJT = 3.510; p<.001). Southern and Northern Europe did not present significant changes over time (ZJT = −1.597; p = .110 and ZJT = 1.622; p = .105). In the Western European region, the United Kingdom and Ireland presented a 55.83% (30.75–47.92; ZJT = 6.917; p<.001) and 125.18% increase (22.83–51.42; ZJT = 3.925; p<.001), respectively. In the Southern European region, Portugal presented a significant increase over time, despite no discernible variations between 2010 and 2021 (21.75–21.58; ZJT = 2.065; p = .039), while Spain and Italy presented significant negative trends with a 52.98% (25.17–11.83; ZJT = −6.301; p<.001) and 24.83% decrease (49–36.83; ZJT = −3.956; p<.001), respecively. In the Northern European region, Sweden was the only country presenting a significant trend towards increase (2.67%; 37.42–38.42; ZJT = 2.794; p = .005). No other European countries presented significant changes over time ().

Changes in google trends RSVs for flexitarianism

Evolution of RSVs for the flexitarianism topic is shown in as dotted lines and the evolution of food sustainability as full lines. From 2010 to 2021, a marked increase in interest in flexitarianism was observed across the analysed European countries. For Europe, an 1083.65% increase was observed (2.59–20.60; ZJT = 12.888; p<.001). Southern European countries presented the highest increase observed (3172.24%; 0.98–32.04; ZJT = 11.773; p<.001), followed by Western European countries, with a 1177.64% increase (2.68–34.28; ZJT = 13.069; p<.001), and Northern European countries with 396.97% increase (4.58–22.78; ZJT = 7.615; p<.001).

When analysed independently, all countries included in the analysis presented significant increase in the relative interest regarding flexitarianism, as measured by the RSVs. Briefly, in the Southern European countries, Portugal presented a 1405.56% increase (1.5–22.58; ZJT = 7.566; p<.001), Spain 1935% (1.67–33.92; ZJT = 11.581; p<.001), and Italy 4466.67% (0.75–34.25; ZJT = 10.600; p<.001). Turkey also presented a significant increase in interest regarding flexitarianism across time (0–37.42; ZJT = 5.878; p<.001), however the 2010 RSV was 0, preventing us from calculating the % of change. In the Western European countries, the United kingdom presented a 870% increase (3.34–32.34; ZJT = 12.086; p<.001), Ireland 524.66% (6.08–38; ZJT = 8.770; p<.001), France 11400% (0.17–19.17; ZJT = 13.626; p<.001), Germany 2318.75% (2.67–64.5; ZJT = 11.717; p<.001), and the Netherlands 1392.86% (1.17–17.42; ZJT = 7.495; p<.001). In the Northern European countries, the interest in the flexitarianism topic increased by 239.29% in Sweden (4.67–15.83; ZJT = 8.703; p<.001), and by 146.79% in Denmark (9.08–22.42; ZJT = 5.123; p<.001), with Norway, despite no % of change being calculated, also presenting a significant increase (0–30.08; ZJT = 3.033; p = .002).

Association of food sustainability with general sustainability, healthy diet, MedDiet and flexitarianism

presents the Kendall’s tau correlation coefficients for the associations of food sustainability with sustainability, healthy diet, MedDiet and flexitarianism. A positive significant association was observed in Europe between food sustainability and sustainability. Similar results were observed for Southern and Northern Europe. Specifically, Italy, Turkey, Norway and Denmark presented significant positive correlations ranging from τ = 0.818 to τ = 0.534. On the other hand, France presented a significant negative correlation (τ = −0.576; p = .009) between food sustainability and sustainability.

Table 3. Food sustainability correlations with sustainability, healthy diet, MedDiet, and flexitarianism.

Associations between the interest in food sustainability and the interest in topics of dietary patterns were also tested. No general associations for food sustainability were observed, for Europe or European regions, with healthy diet or MedDiet. A positive association between food sustainability and healthy diet RSV was observed for France (τ = 0.545; p = .014). MedDiet and food sustainability were positively associated in Portugal (τ = 0.445; p = .050), the United Kingdom (τ = 0.697; p = .002), and Ireland (τ = 0.485; p = .028). Interestingly, a positive strong association, between food sustainability and flexitarianism, was observed for Europe (τ = 0.848; p<.001). This association was also significant in the European regions, namely Southern Europe (τ = 0.909; p<.001), Western Europe (τ = 0.636; p = .004), and Northern Europe (τ = 0.576; p = .009). The Southern European countries Portugal (τ = 0.636; p = .005), Italy (τ = 0.657; p = .003), and Turkey (τ = 0.724; p = .002) presented positive associations between food sustainability and flexitarianism, while Spain did not present a significant association (τ = 0.242; p = .273). In Western Europe, the United Kingdom (τ = 0.636; p = .004), Ireland (τ = 0.727; p = .001), France (τ = 0.576; p = .009), and Germany (τ = 0.455; p = .040) presented positive associations between food sustainability and flexitarianism, while the Netherlands did not (τ = −0.229; p = .303). In the Northern European countries, significant association between food sustainability and flexitarianism were found in Norway (τ = 0.595; p = .007) and Denmark (τ = 0.481; p = .032), but not in Sweden (τ = 0.382; p = .086).

Discussion

In this study, the public interest in food sustainability, and its association with sustainability and the public interest in dietary patterns, was explored for the first time. Specifically, we used the RSVs provided by Google Trends to examine temporal patterns of public interest in food sustainability and to test its associations from 2010 to 2021.We found a significant increase in the public interest on food sustainability in the European countries analysed, with few exceptions, namely the Netherlands and Sweden. A similar trend was observed for the public interest in the sustainability topic. The public interest in food sustainability, and in sustainability, were significantly associated in Europe, specifically in Southern and Northern Europe. We also found that public interest in healthy diets generally increased in Europe, specifically in Northern and Western Europe, but not in the Southern European region. A significant increase in the public interest on MedDiet was also observed, specifically in Western Europe. Public interest in healthy diet and MedDiet were not associated with interest in food sustainability in any of the European regions, despite a few associations observed in some countries. Interestingly, public interest in the topic of flexitarianism significantly increased in all the countries analysed and that increase was significantly associated with the increase in the topic of food sustainability in all the European regions and in most of the countries.

Tulloch et al. (Tulloch et al. Citation2021) used google trends to explore the public interest in nature-related impacts of agri-food system. They found that, from 2009 to 2019, public interest in environmental sustainability increased, with consumers increasingly demanding information on the impacts of their food consumption choices on the environment, human health, and animal welfare. These results align with our findings that interest in food sustainability is, in general, positively correlated with the interest in sustainability. On the other hand, Van Bussel et al. (van Bussel et al. Citation2022) reported that sustainability does not influence consumers food choices, and consumers have difficulty defining the concept “sustainability” and to estimate the environmental impact of their food choices (van Bussel et al. Citation2022). Also, Macdiarmid and colleagues (Macdiarmid et al. Citation2016), in a study regarding public awareness of the environmental impact of food, found a lack of consumers’ awareness on the association between food consumption and environmental impact, and a rooted perception that personal dietary behaviour has a minimal impact on environmental sustainability. The authors also reported the belief that other human activities such as transportation, pollution from industry and power stations, and land clearance by non-food industries, were often regarded as more environmentally damaging than food production. The apparent disassociation between the public perception regarding food sustainability and general sustainability and environmental impacts is difficult to conciliate with our results; therefore, it is possible that changes in public interest in food sustainability and sustainability have occurred concomitantly, but in an unrelated fashion.

Global interest in healthy diet from 1 January 2004 to 30 June 2020, measured in RSV, has globally decreased according to Palomo-Llinares et al. (Palomo-Llinares et al. Citation2021). We found that from 2010 to 2021, in the Northern and Western European regions, a significant increase in the public interest in healthy diet was observed. A possible explanation for the mismatch in these finding may lay on the regional specificity of our findings. We also observed regional increases in the public interest in MedDiet that was not consistent across all the European regions. Kamiński et al. (Kamiński et al. Citation2020) explored the global trends in diets popularity from 2004 to 2019 and observed a significant increase in the popularity of the MedDiet. Despite the global increase in the public interest regarding MedDiet, the authors also shown that this interest is not equal in all countries. No studies were found regarding the evolution of public interest on flexitarianism, yet it was reported that in the United Kingdom the expression “Planetary Diet” had a high RSV on Google Trends and there was a specific peak at the Eat-Lancet Commission report launch date (Luderer Citation2022). Despite not using the same search term, Kamiński et al. (Kamiński et al. Citation2020) found a marked increase in the popularity of the plant-based diet, which is a concept similar to flexitarianism.

Since health and nutrition are an important dimension on “nutritional sustainability” (Portugal-Nunes et al. Citation2021), we would expect an association between healthy dietary patterns and food sustainability public interest; however, this was true only for flexitarianism. A possible explanation lays on the higher internet use by younger individuals (Dunahee and Lebo Citation2016), who are more likely to seek online information associated with health compared to older internet users (Kontos et al. Citation2014). Environmental issues are also particularly salient for young adults (McDougle et al. Citation2011) who, at the same time, are more prone to transitioning towards a flexitarian diet (Kemper and White Citation2021). Culliford and Bradbury (Culliford and Bradbury Citation2020), in a study exploring the readiness of consumers to adopt an environmentally sustainable diet, found that health was among the most commonly reported motives for food choices, highlighting the public knowledge between eating behaviour an health. Furthermore, in a recent systematic review on consumers’ perceptions on food-related sustainability, van Bussel et al. (van Bussel et al. Citation2022) found that price, taste, and individual health are more influential than sustainability on consumers’ food choices.

Consumers have significant influence over the direction of the food system and food system sustainability. Through the acquisitions of foods they express their preferences and values and help shape the decisions made by producers and retailers. Their influence is growing as they consider what they buy, why they buy it and how and where they purchase their food. The nature and extent of consumers influence is shaped by several factors such as geography, cultural norms, government policy, socio-economic status, and, in a great extent, by information and knowledge (Zander and Hamm Citation2010; Ghvanidze et al. Citation2016; OECD/FAO Citation2018; Initiative Citation2018).

Previous work found that the concepts of healthy diets and sustainable diets are perceived as highly compatible by consumers (Van Loo et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, the concept of a plant-based diet, like a flexitarian diet, was also found to highly compatible with a healthy and sustainable diet. Our results support the compatibility of a flexitarian and sustainable diet through the analysis of interest in those topics. Policies addressing sustainable and healthy diets based on a flexitarian dietary pattern may be well accepted by the public.

The strategy used in this work may be particularly relevant nowadays. Recently, major global events have challenged the food systems and publicly emphasise their vulnerability, namely the Covid-19 pandemic (Bakalis et al. Citation2020) and the war in Ukraine (Behnassi and El Haiba Citation2022; Ben Hassen and El Bilali Citation2022). With Covid-19 outbreak, growing media attention highlighted incidents of food flow disruption due to the pandemic, from vegetables left to rotten in fields, food processing facilities running short of staff due to the disease, and panic-buying in stores (Dou et al. Citation2021). On top of the Covid-19 imposed constrains on food systems, the Russian-Ukrainian conflict has also adversely affected food supply chains, with significant effects on production, processing, and logistics, and significant shifts in demand that had a global impact (Jagtap et al. Citation2022). Our work describes the tendencies on public interest regarding food sustainability, sustainability, and some relevant dietary patterns, setting the ground to the study of how major events affect public interest. Using data previous to those events it may be possible to develop models of how public interest would progress in the absence of those events and then compare to the real progression of public interest. Studies of this kind may provide clues on how individuals change their priorities in face of major alterations that affect the food systems.

Conclusion

Here it was explored, for the first time, consumer interest in food sustainability and healthy dietary patterns in Europe. According to our results, despite the growing interest, there is a mismatch between food sustainability, healthy diet, and MedDiet. On the other hand, public interest in flexitarian diet and food sustainability seems to be consistently associated across all the counties analysed. Understanding consumers’ beliefs and behaviours towards food choices is crucial for the transition towards sustainable diets. On this, the definition of educational and behavioural interventions are essential to this transition (Biasini et al. Citation2021), and engagement, interest and information seeking are essential for the construction of beliefs and behaviours. We believe that more research is needed in this field; nevertheless, our findings may be important for policy makers to design and select strategies that may promote a transition to a sustainable food system supported in the healthy dietary patterns.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderegg WRL, Goldsmith GR. 2014. Public interest in climate change over the past decade and the effects of the ‘climategate’ media event. Environ Res Lett. 9(5):054005.

- Arnalte-Mur L, Ortiz-Miranda D, Cerrada-Serra P, Martinez-Gómez V, Moreno-Pérez O, Barbu R, Bjorkhaug H, Czekaj M, Duckett D, Galli F, et al. 2020. The drivers of change for the contribution of small farms to regional food security in europe. Global Food Secur. 26:100395.

- Bakalis S, Valdramidis VP, Argyropoulos D, Ahrne L, Chen J, Cullen PJ, Cummins E, Datta AK, Emmanouilidis C, Foster T, et al. 2020. Perspectives from co + re: how covid-19 changed our food systems and food security paradigms. Curr Res Food Sci. 3:166–172.

- Bangwayo-Skeete PF, Skeete RW. 2015. Can google data improve the forecasting performance of tourist arrivals? Mixed-data sampling approach. Tourism Management. 46:454–464.

- Behnassi M, El Haiba M. 2022. Implications of the Russia–Ukraine war for global food security. Nat Hum Behav. 6(6):754–755.

- Ben Hassen T, El Bilali H. 2022. Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war on global food security: towards more sustainable and resilient food systems? Foods. 11(15):2301.

- Biasini B, Rosi A, Giopp F, Turgut R, Scazzina F, Menozzi D. 2021. Understanding, promoting and predicting sustainable diets: a systematic review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 111:191–207.

- Burlingame B, Dernini S. 2011. Sustainable diets: the Mediterranean diet as an example. Public Health Nutr. 14(12a):2285–2287.

- Burlingame B, Dernini S. 2012. Sustainable diets and biodiversity directions and solutions for policy, research and action. Rome: FAO Headquarters.

- Cena H, Calder PC. 2020. Defining a healthy diet: evidence for the role of contemporary dietary patterns in health and disease. Nutrients. 12(2):334.

- Culliford A, Bradbury J. 2020. A cross-sectional survey of the readiness of consumers to adopt an environmentally sustainable diet. Nutr J. 19(1):138.

- Derbyshire EJ. 2017. Flexitarian diets and health: a review of the evidence-based literature. Front Nutr. 3:55.

- Dernini S, Berry EM. 2015. Mediterranean diet: from a healthy diet to a sustainable dietary pattern. Front Nutr. 2:15.

- OECD/FAO. 2018. OECD-FAO agricultural outlook 2018–2027. Paris/FAO, Rome: OECD Publishing.

- Dinu M, Pagliai G, Casini A, Sofi F. 2018. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 72(1):30–43.

- Dou Z, Stefanovski D, Galligan D, Lindem M, Rozin P, Chen T, Chao AM. 2021. Household food dynamics and food system resilience amid the covid-19 pandemic: a cross-national comparison of China and the United States. Front Sustain Food Syst. 4:577153.

- Dunahee M, Lebo H. 2016. The world internet project international report. Los Angeles, CA: Center for the Digital Future.

- Eker S, Reese G, Obersteiner M. 2019. Modelling the drivers of a widespread shift to sustainable diets. Nat Sustain. 2(8):725–735.

- Fondeur Y, Karamé F. 2013. Can Google data help predict French youth unemployment? Economic Modelling. 30:117–125.

- Ghvanidze S, Velikova N, Dodd TH, Oldewage-Theron W. 2016. Consumers’ environmental and ethical consciousness and the use of the related food products information: the role of perceived consumer effectiveness. Appetite. 107:311–322.

- Ilieva RT, McPhearson T. 2018. Social-media data for urban sustainability. Nat Sustain. 1(10):553–565.

- Initiative GH. 2018. 2018 global agricultural productivity report® (gap report®). Consumer evolutions transform the global food system. Washington, D.C.: GHI.

- IPCC. 2019. Climate change and land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. Geneva, Switzerland. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ffnIggZePcbx3EkfOogz5DUMC8lrZ8t0/view.

- Jagtap S, Trollman H, Trollman F, Garcia-Garcia G, Parra-López C, Duong L, Martindale W, Munekata PES, Lorenzo JM, Hdaifeh A, et al. 2022. The Russia-Ukraine conflict: its implications for the global food supply chains. Foods. 11(14):2098.

- Jones AD, Hoey L, Blesh J, Miller L, Green A, Shapiro LF. 2016. A systematic review of the measurement of sustainable diets. Adv Nutr. 7(4):641–664.

- Jun S-P, Yoo HS, Choi S. 2018. Ten years of research change using google trends: from the perspective of big data utilizations and applications. Technol Forecasting Social Change. 130:69–87.

- Kamiński M, Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Nowak JK, Stachowska E. 2020. Global and local diet popularity rankings, their secular trends, and seasonal variation in google trends data. Nutrition. 79-80:110759.

- Kemper JA, White SK. 2021. Young adults’ experiences with flexitarianism: the 4cs. Appetite. 160:105073.

- Kontos E, Blake KD, Chou W-YS, Prestin A. 2014. Predictors of ehealth usage: insights on the digital divide from the health information national trends survey 2012. J Med Internet Res. 16(7):e172.

- Lawrence MA, Baker PI, Pulker CE, Pollard CM. 2019. Sustainable, resilient food systems for healthy diets: the transformation agenda. Public Health Nutr. 22(16):2916–2920.

- Luderer CAF. 2022. A new diet: news on food habits and climate change. In: Leal Filho W, Djekic I, Smetana S, Kovaleva M, editors. Handbook of climate change across the food supply chain. Climate change management. Switzerland: Springer, Cham; p. 39–53.

- Macdiarmid JI. 2013. Is a healthy diet an environmentally sustainable diet? Proc Nutr Soc. 72(1):13–20.

- Macdiarmid JI, Douglas F, Campbell J. 2016. Eating like there’s no tomorrow: public awareness of the environmental impact of food and reluctance to eat less meat as part of a sustainable diet. Appetite. 96:487–493.

- Mavragani A, Ochoa G, Tsagarakis KP. 2018. Assessing the methods, tools, and statistical approaches in google trends research: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 20(11):e270.

- McDougle LM, Greenspan I, Handy F. 2011. Generation green: understanding the motivations and mechanisms influencing young adults’ environmental volunteering. Int J Nonprofit Volunt Sect Mark. 16(4):325–341.

- Meybeck A, Gitz V. 2017. Sustainable diets within sustainable food systems. Proc Nutr Soc. 76(1):1–11.

- Nuti SV, Wayda B, Ranasinghe I, Wang S, Dreyer RP, Chen SI, Murugiah K. 2014. The use of google trends in health care research: a systematic review. PLOS One. 9(10):e109583.

- O'Rourke D, Lollo N. 2015. Transforming consumption: from decoupling, to behavior change, to system changes for sustainable consumption. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 40(1):233–259.

- Outlaw JL, Smith EG. 2001. The 2002 farm bill: policy options and consequences. Oak Brook, IL: Farm Foundation.

- Palma Lampreia Dos Santos MJ. 2018. Nowcasting and forecasting aquaponics by google trends in European countries. Technol Forecasting Social Change. 134:178–185.

- Palomo-Llinares R, Sánchez-Tormo J, Wanden-Berghe C, Sanz-Valero J. 2021. Trends and seasonality of information searches carried out through google on nutrition and healthy diet in relation to occupational health: infodemiological study. Nutrients. 13(12):4300.

- Parodi A, Leip A, De Boer IJM, Slegers PM, Ziegler F, Temme EHM, Herrero M, Tuomisto H, Valin H, Van Middelaar CE, et al. 2018. The potential of future foods for sustainable and healthy diets. Nat Sustain. 1(12):782–789.

- Portugal-Nunes C, Nunes FM, Fraga I, Saraiva C, Gonçalves C. 2021. Assessment of the methodology that is used to determine the nutritional sustainability of the Mediterranean diet—a scoping review. Front Nutr. 8:772133.

- Preis T, Moat HS, Stanley HE. 2013. Quantifying trading behavior in financial markets using google trends. Sci Rep. 3(1):1684.

- Preis T, Reith D, Stanley HE. 2010. Complex dynamics of our economic life on different scales: insights from search engine query data. Phil Trans R Soc A. 368(1933):5707–5719.

- Search engine market share. 2022. https://netmarketshare.com/search-engine-market-share.aspx.

- Springmann M, Wiebe K, Mason-D'Croz D, Sulser TB, Rayner M, Scarborough P. 2018. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Health. 2(10):e451–e461.

- Tilman D, Clark M. 2014. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature. 515(7528):518–522.

- Tulloch AIT, Miller A, Dean AJ. 2021. Does scientific interest in the nature impacts of food align with consumer information-seeking behavior? Sustain Sci. 16(3):1029–1043.

- van Bussel LM, Kuijsten A, Mars M, van ‘t Veer P. 2022. Consumers’ perceptions on food-related sustainability: a systematic review. J Cleaner Prod. 341:130904.

- Van Loo EJ, Hoefkens C, Verbeke W. 2017. Healthy, sustainable and plant-based eating: perceived (mis)match and involvement-based consumer segments as targets for future policy. Food Policy. 69:46–57.

- Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, Garnett T, Tilman D, DeClerck F, Wood A, et al. 2019. Food in the anthropocene: the eat-lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 393(10170):447–492.

- Yip CSC, Crane G, Karnon J. 2013. Systematic review of reducing population meat consumption to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and obtain health benefits: effectiveness and models assessments. Int J Public Health. 58(5):683–693.

- Zander K, Hamm U. 2010. Consumer preferences for additional ethical attributes of organic food. Food Qual Preference. 21(5):495–503.

- Zhu J, Wang X, Qin J, Wu L. 2012. Assessing public opinion trends based on user search queries: validity, reliability, and practicality. Paper presented at 65th Annual Conference of the World Association for Public Opinion Research; China. p. 1–7.