Abstract

COVID-19 and the resulting measures to curb the spread of the virus have significantly changed our lives, including our nutritional choices. In this rapid scoping review an overview is provided of what psychological factors may be associated with peoples’ eating behaviour during COVID-19 restrictions. Relevant literature was identified using PubMed, PsycInfo, CINAHL and MEDLINE databases from 2019 onwards. For included studies, information on study characteristics, eating behaviours, and psychological factors were extracted. 118 articles were included, representing 30 countries. Findings indicated that most people consumed more and unhealthy food in times of COVID-19 restrictions, while some consumed less but often for the wrong reasons. Several psychological factors, related to (1) affective reactions, (2) anxiety, fear and worriers, (3) stress and (4) subjective and mental wellbeing were found to be associated with this increase in food consumption. These outcomes may help to be better inform future interventions, and with that, to be better prepared in case of future lockdown scenarios.

Introduction

In late December 2019, several cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome were reported (Barbarossa et al. Citation2020). In March 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic (Sohrabietal Citation2020). Most countries imposed strict measures to prevent the infection from spreading, such as travel bans, lockdowns, and many restrictions on daily living, including isolation, social distancing, and home confinement. While these strict precautionary measures were necessary to protect the public health, the restrictions to stay at home, to work at home, and to avoid close contact with others for a prolonged time also has negative psychological effects. Indeed, population-based studies have shown a high occurrence of self-reported psychological distress during phases of the pandemic in different populations and contexts (Benfante et al. Citation2020; Di Renzo, Gualtieri, Cinelli, et al. Citation2020; Mazza et al. Citation2020; Pappa et al. Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2020; Pirrone et al. Citation2022). It is likely that COVID-19, the restrictions, and the psychological consequences – including increased daily stress levels – have also influenced people’s eating behaviours (see for example Di Renzo, Gualtieri, Cinelli, et al. Citation2020).

Current studies on eating habits amid the COVID-19 outbreak portray a change in self-reported eating towards more unhealthy eating habits, such as consuming high caloric “comfort” foods, unrestricted eating, and snacking between meals (Ammar et al. Citation2020; Scarmozzino and Visioli Citation2020; Di Renzo, Gualtieri, Cinelli, et al. Citation2020; Robinson et al. Citation2021). Stress is known to be associated with increased reward-driven comfort food intake as a means to “feel better”, while emotional eating and associated eating behaviours are closely related to stressful life events and to perceptions of life as stressful (Camilleri et al. Citation2014). In contrast to reports of increased unhealthy eating habits, there have also been reports of people embracing healthier diets during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, a study conducted among the Spanish population by Rodríguez-Pérez et al. (Citation2020) found that during the lockdown in Spain, people adopted healthier dietary habits, with increased consumption of foods such as vegetables, fruits, legumes, and olive oil.

Considering the increasing body of studies that observe different dietary changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the known associations between psychological factors such as stress and eating, there is a need to provide an overview of whether and how individuals’ eating behaviour was affected as a result of the measures imposed by various governments around the world. Additionally, to optimally prepare for potential future lockdown scenarios, an overview of the psychological determinants (i.e. the psychological constructs that theoretically are assumed to affect behaviour) is needed. Knowledge of these psychological factors may help to be better inform future interventions. To this end, we conducted a rapid scoping review as a first step to investigate the associations between psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, or depression, and individuals’ nutritional choices and eating behaviour.

Methods

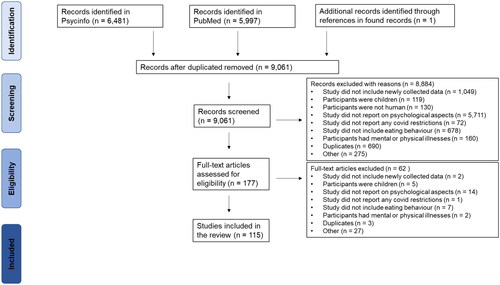

Papers about dietary changes during the COVID-19 pandemic were identified by searching PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and MEDLINE databases from 2019 onwards. The initial search was performed on 20 April 2021, and updated on 19 December 2021. Initially, we aimed to develop a search strategy containing terms related to (1) COVID-19, consequent lockdowns, or restrictions, and (2) eating or dietary behaviours, and (3) psychological outcomes. However, for the literature search, this last criterion was not feasible, because the psychological outcomes were too varied depending on the underlying theoretical concept. Therefore, we did not capture this third criterion in query terms: we used the first two criteria and then selected papers that mentioned any psychological concepts (see ).

Table 1. Search strategies used in PubMed and PsycInfo.

After removing duplicate records, three authors (AvL, MD, SR) independently screened titles, abstracts and full texts against the predefined inclusion criteria (see next section). In each screening round, 20% of all papers were double checked (also by AvL, MD, SR). Discrepancies were presented and resolved in consultation with a fourth and fifth author (KM and GtH). Lastly, the reference list and citations of included papers were screened to identify additional papers of interest. A PRISMA flow diagram of the complete search procedure is included (see ).

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematics reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram of search procedure.

In- and exclusion criteria

Papers were included if (a) at least one psychological outcome was reported (initially defined in the broadest sense of the word) and (b) a relationship between dietary changes in healthy adults (18+) and the COVID-19 lockdown was reported. This 18+ criterion was applied to ensure that individuals were relatively responsible for their own food choices. However, some studies included participants of 16+ years which were also included as the largest group of participants was still 18+ years. No restrictions were made regarding methods or design of the study, but studies that did not include newly collected data (e.g. letters to the editor, narratives, reviews) were excluded.

The following exclusion criteria were applied. First, papers focussing on dietary changes in children (Mean age < 18 years) were excluded as their food intake still largely depends on their parents, and they are not completely responsible for their own food choices. Furthermore, psychological factors are mostly not researched in children due to ethical reasons. Second, dietary changes due to COVID-19 in individuals with illnesses (mental or physical) were not included because these people might already have altered eating habits which is why the results of these papers might not be representative for the general population, which was the focus of this study. Moreover, illnesses might influence psychological factors just due to the illness per se and not due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, to narrow down the thematic focus of this review, papers that report on changes in drinking behaviour due to COVID-19, instead of eating behaviours, were excluded. Lastly, papers written in another language than English were not included either.

Extraction of data

For the included papers, the following information was extracted from the papers: sample size, age, country, study methodology, type of COVID-19 restrictions, methods for assessing diet, type of eating behaviour, psychological factor(s) and how they were assessed, and study results. For all included studies, this data can be found .

Table 2. Overview of the included studies.

Extraction of psychological outcomes

After data extraction, it turned out that different authors used different labels for the psychological outcomes. To decide which psychological outcome measures could be aggregated, a consensus approach was applied. First, three authors (AvL, MD, SR) individually created a list of categories. Subsequently, the fourth and fifth author (KM and GtH) combined the three initial lists into a final list of categories. All psychological outcomes were ordered into the following broad categories: (1) Affective reactions, (2) Anxiety, Fears, Worries, (3) Stress, (4) Subjective and Mental Wellbeing. These four factors are not mutually exclusive, and include multiple psychological outcomes as measured in the included studies (e.g. our label “affective reactions” included a diversity of specific emotions like anger and loneliness, but excluded anxiety, fears, and worries). We deemed that the ordering may help with interpreting and structuring the outcomes. In the results section, each of those four categories will be described, including a list of included outcomes.

Results

Overall, 118 studies, representing a total of 30 countries, were included in this systematic literature review. Both cross-sectional (n = 50) and longitudinal observations (n = 8) were included. Where the cross-sectional studies mostly offered insight into initial changes in dietary habits during the pandemic, longitudinal studies illustrate differences in pre-pandemic experiences with current COVID-19 dietary settings. Both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies showed that dietary habits changed significantly during the COVID-19 confinement (see ). Most often a change in quantity of consumed food was reported: overall, people reported eating more during the lockdown than before. People consumed more food of all categories, including snacks and fried food but also fruit and vegetables for example. A healthier diet often included eating home-cooked meals, not ordering meals, low frequency of skipping meals and increased fruit consumption. An unhealthier diet often consisted of increased intake of fried food, sugary foods, fast food, increased snacking, and a high salt intake (see . Note that papers are distinguished by “psychological factors”, therefore the same paper can be repeatedly mentioned when more than one factor is included).

Psychological factors related to dietary changes

Except for three cases, all studies were summarised under four final broad headings: (1) Affective reactions, (2) Anxiety, fear and worries, (3) Stress, and (4) Subjective and mental wellbeing.

Affective reactions

Of all papers, 52 report on people’s eating behaviour in times of COVID-19 in relation to measures of affective reactions, including specific emotions (e.g. anger), depression, and loneliness: 18 published in 2020 and 34 in 2021. The number of participants is relatively high; only 4 studies have less than 100 participants, while 27 have more than 1000, including one study with 45.161 participants (Szwarcwald et al. Citation2021). The percentages of female participants vary; for most studies it is between 50–80%, with among the few exceptions 1 quite low (13.3%; Snuggs and McGregor Citation2021), and 3 quite high (100%; Al-Musharaf Citation2020; Kekäläinen et al. Citation2021; Cirillo Citation2021). Moreover, two studies included only students (Romero-Blanco et al. Citation2020; Xie et al. Citation2021). All participants are over 18 years old and almost all age means are within 20–40 years old, except four studies among elderly, M: resp. 68, 74 and ≥65 years old (Vitman-Schorr et al. Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Lehtisalo et al. Citation2021). From these studies in this category, 26 are from Europe, 3 from Israel, 5 from the USA, 2 from China and 2 from Chilli, plus single studies from Australia, Brazil, Peru, South-Korea, Quatar and Lebanon.

Almost all studies made use of an online survey, except one that used a postal survey (Lehtisalo et al. Citation2021) and three that used telephone interviews (Garre-Olmo et al. Citation2021; Vitman-Schorr et al. Citation2021a, Citation2021b). These studies report on changes in eating behaviours, including eating habits, diet and food, in combination with psychological factors, especially affective reactions.

For eating behaviour in relation to affective reactions, there is a wide range of measuring instruments. Most studies focussed on eating behaviour at the time of participation, but in about a third of the studies people were asked to compare their current food intake with their intake before COVID-19. In the majority of studies some kind of measure for eating disorders is used, often including binge eating and weight concerns. In a minority of studies the focus is on food intake, food choice, malnutrition, and BMI, mostly at the individual level, but sometimes at the family level. Of these studies, 3 make use of the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEB); 3 the Binge Eating Scale (BED), 2 the Short Diet Behaviours Questionnaire for Lockdowns (SDBQL) and 2 the Adult Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (AEBQ), see also .

Table 3. Examples of measures that were used more than once.

For the psychological factors, there is again a wide range of measuring instruments and only a few studies use comparable measures. The relatively most frequently used measures are the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, 11x), the UCLA-3 loneliness scale (3x), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10, 5x), the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress scale (DASS-21, 7x; DASS-42, 1x), the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS, 2x), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI, 2x), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS, 2x, and the CES-3 depression scale (2x); see also . All other measures are unique for the studies in which they are applied, often specific for the situation that many of the participants are more often at home most of the time.

All studies mention that, overall, the COVID-19 lockdowns have negative effects on people’s affective reactions: On the one hand, there are unhealthy lifestyles, increase in BMI, poorer sleep, malnutrition, binge eating and loneliness, on the other hand anxiety, depression and weight concerns. Generally, the lockdowns have caused food patterns that are less healthy, however, not for everyone (e.g. Deschasaux-Tanguy et al. Citation2021). Overweight people do relatively worse in terms of affective reactions, while underweight people do better (Herle et al. Citation2021). Simone (Citation2021) suggests that low stress management skills lead to unhealthy weight control behaviour. Interestingly, how important weight control is for people, can have positive as well as negative effects (Marty et al. Citation2021). Depressive feelings during COVID-19 (and especially in combination with COVID related concerns) are often associated with lower food quality, less physical activity, less sleep, more emotional eating and a higher BMI, but this association was not found in all studies and also not for all participants in these studies (Robinson et al. Citation2021). Some authors report that the negative effects of the lockdown are especially strong for dietary/eating behaviours, and less for exercise; Amatori (Citation2020, 1) even suggests that: “Exercise led to healthier nutritional choices, and mediating the effects of mood states, it might represent a key measure in uncommon situations, such as home-confinement”.

Anxiety, fears, worries

Of all papers, 56 report on people’s eating behaviour in times of COVID-19 in relation to measures of anxiety, fear and worries, including concerns and uncertainties: 17 were published in 2020 and 39 in 2021. The number of participants is relatively high; only 5 studies have less than 100 participants, while 29 have more than 1000. The percentages of female participants vary, but for most studies, it is between 50% and 80%, with 11 studies >80%; of which one among pregnant women (Pope et al. Citation2022). Moreover, three studies included only students (Romero-Blanco et al. Citation2020; Kalkan Uğurlu et al. Citation2021; Xie et al. Citation2021), tow studies targeted only adults with obesity (Pellegrini et al. Citation2020; Marchitelli et al. Citation2020) and one only HCW’s (Tran et al. Citation2020). All participants are over 18 years old and almost all age means are within 20–40 y, with 5 studies >40 y. From the studies, 26 studies are from Europe, 4 from the USA, 2 from China, 2 from Saudi-Arabia plus single studies from Lebanon, Israel, Japan, Peru, Ethiopia, Qatar, Lebanon, Zimbabwe, Australia, Vietnam, India, Chilli, and China. Almost all studies made use of an online survey; one study used telephone interviews (Garre-Olmo et al. Citation2021). These studies report on changes in eating behaviours, including eating habits, diet and food, in combination with psychological factors, especially anxiety, fears and worries.

For eating behaviour in relation to anxiety, fear and worries, there is a wide range of measuring instruments; however, with almost no comparable methods. In all studies, food intake is measured, often in combination with a habit measure. Many studies include some weight measure, often BMI, and in half of the studies there is some kind of comparison between before and after COVID-19. Also in about half of the studies, some kind of measure of emotional, external and/or restricted eating is used. In the study among pregnant women, the Prenatal Health Behaviour Scale (PHBS) was applied (Pope et al. Citation2022).

For the psychological factors, there is again a wide range of measuring instruments, with only a few studies using comparable measures. The most frequently used labels are anxiety, fear and worries. The relatively most frequently used measures are the Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7, 11x; GAD-2, 1x), the PHQ (PHQ-9, 9x; PHQ-2, 2x), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-42,2x; DASS-21, 5x), the Fear of Covid-19 (FCV-19, 3x); the PSS (PSS-4, 4x; PSS-10, 2x), the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, 3x); and the BAI (3x); see also . Other measures are unique for the studies in which they are applied. Individual studies sometimes have specific interest, such as loneliness, intolerance for uncertainty, stress, sleep quality, worries about the economy, or from a different perspective, pleasure, trust in institutions, or confidence.

A majority of studies indicate a negative effect of anxiety, fear and worries on people’s eating behaviour. Emotional eating is associated with anxiety (12x), anxiety and stress (3x), and anxiety, depression and stress (3x). Some other findings mention that anxiety and stress cause weight gain, that high fear of COVID leads to shape and weight concerns, that loneliness leads to overeating, and that some people try to counter stress by eating. Coakley (Citation2021) mentions that groups experiencing the highest degree of moderate to severe anxiety symptoms included transgender, gender fluid, and other-gendered participants. Savarese (Citation2021) reports that people may have doubts about the importance of strengthening the immune system through food consumption.

However, not all outcomes are negative. People who habitually follow the Mediterranean diet show less negative changes (Romero-Blanco et al. Citation2020; Kaufman-Shriqui et al. Citation2021), one study shows positive effects that mirror the negative effects (Deschasaux-Tanguy et al. Citation2021) and one study among HCW’s implies that a higher level of health literacy may counter stress (Tran et al. Citation2020). Wilson (Citation2021) reports that fat intake was not significantly associated (p > 0.05) with any measures of mental health.

Stress

Of all papers, 51 reported on people’s eating behaviour in times of COVID-19 in relation to measures of stress: 15 published in 2020, 36 in 2021. The number of participants is relatively high; only 4 studies have less than 100 participants, while 13 have more than 1000. The percentages of female participants vary, but are between 50% and 80% for most studies, with two studies having 100% females, one targeting pregnant women (Pope et al. Citation2022) and one targeting nurses (Nashwan et al. Citation2020). Moreover, two studies included only students (Kalkan Uğurlu et al. Citation2021; Jalal Citation2021) and one study only people with current and past obesity (Jimenez et al. Citation2021). All participants are over 18 years old and in three studies the mean age is >40. From these studies, 20 are from Europe, 10 from the USA, 3 from China, 2 from Saudi-Arabia, Peru and Brazil, 1 from Japan, Chilli and Israel, 1 from Ireland, the UK and the US combined, and 1 from 38 countries combined. All studies made use of an online survey. These studies report on changes in eating behaviours, including eating habits, diet and food, in combination with psychological factors, especially stress.

For eating behaviour in relation to stress, there is a wide range of measuring instruments. Next to BMI, most instruments measure emotional and/or restrained eating, e.g. the BED, the Emotional Easter Questionnaire (EEQ) or the DEB. Pope et al. (Citation2022) applies the PHBS. For the psychological factors, there is again a wide range of different measures, and only rarely the same: PSS (PSS-4, 1x; PSS-10, 8x, PSS-14, 1x), DASS (DASS-21, 8x; DASS-42, 1x), GAD (GAD-2, 1x, GAD-7, 1x), PHQ (PHQ-2, 1x; PHQ-9, 1x), 1x); FCV-19, 1x), see also . Other measures are unique for that study and include, for example, body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, anxiety disorder, or depression.

Of these 51 studies on stress, 45 report a (statistical) connection between an increase in stress and an increase in unhealthy eating in times of COVID-19; among those are four studies that report a greater effect for women compared to men. Moreover, two other studies only included women, and both show the same direct connection between stress and unhealthy eating (Al-Musharaf Citation2020; Pope et al. Citation2022). Most studies report a decrease in food quality and food intake, some studies report increases in weight and all studies that included measures of emotional eating report an increase in emotional eating. Alothman (Citation2021) demonstrates a connection between Fear of COVID-19 and stress. Not all outcomes are negative; Shimpo (Citation2021) describes positive effects on diet among people with higher income and health literacy, while Madali (Citation2021) and Alon-Tirosh (Citation2021) report on positive next to negative changes in their participants. Tribst (Citation2021) shows a positive effect of family support on dealing with COVID-19-related stress. LaCaille (Citation2021) shows in a study with students, that of the health behaviours that are protective for mental health and stress during the pandemic, only diet quality emerged as a significant predictor.

Some findings are relatively unique because they were only asked in specific studies. In the study among pregnant women, Pope et al. (Citation2022) show that COVID-related stress leads to more adherence to guidelines in pregnant women and also suggest that social support can help pregnant women to deal better with COVID-related stress. De Backer et al. (Citation2021) suggest that COVID-stress is a barrier for healthy eating for women, but an enabler for men. Huber (Citation2020) found in male participants that stress led to a BMI increase in combination with a decrease in sports activities. Du (Citation2021) suggests that stress in times of COVID also increases alcohol misuse. Jeżewska-Zychowicz (Citation2020) reports that Polish people are afraid that food will not be easily available over time and Matsungo and Chopera (Citation2020) does report an actual increase in food prices during the lockdown. Zachary (Citation2020) found that especially those people who use food as a coping mechanism, gained weight, while Smith (Citation2021) reports that highly processed and sweet foods have high motivating value across multiple measures of dealing with COVID-19 related stress, while Salazar-Fernández (Citation2021) shows that people use comfort food to deal with increased emotional distress.

Subjective and mental wellbeing

Of all papers, 44 report on people’s eating behaviour in times of COVID-19 in relation to measures of subjective and mental wellbeing, including mood and quality of life: 17 were published in 2020 and 27 in 2021. The number of participants is relatively high; only 2 studies have less than 100 participants, while 11 have more than 1000. The percentages of female participants vary, but for most studies, it is between 50% and 75%; 100% in the study by Cirillo (Citation2021). Moreover, three studies included only students (Romero-Blanco et al. Citation2020; Xie et al. Citation2021; Kalkan Uğurlu et al. Citation2021). All participants are over 18 years old and almost all age means are within 20–40 y. From these studies, 13 studies are from Europe, 5 from China, 2 from the US, plus single studies from Ghana, Lebanon, Zimbabwe, South Korea and Turkey. Almost all studies made use of an online survey. These studies report on changes in eating behaviours, including eating habits, diet and food, in combination with psychological factors, especially subjective and mental wellbeing.

For eating behaviour in relation to subjective and mental well being, there is a wide range of measuring instruments. In some studies eating behaviour is measured at that time, sometimes changes in eating behaviour is measured, and sometimes (old and new) eating habits. In other studies, the focus is on eating frequency, sometimes on food quality. Other studies focus on eating motivation, and specifically on anxiety and boredom driven eating, binge eating and eating restrictions. Others combine measures of eating with BMI scores. One reason for the diversity in measuring instruments is culture; the Mediterranean diet (Biviá-Roig et al. Citation2020) as well as the Chinese diet (Xie et al. Citation2021) are mentioned. Finally, two studies used a newly developed Short Diet Behaviours Questionnaire for Lockdowns (SDBQL; Ammar et al. Citation2020).

For the psychological factors, there is again a wide range of measuring instruments and only a few studies use comparable measures. The most frequently used are the PHQ: PHQ-2 (1x), PHQ-4 (2x), PHQ-9 (3x), followed by the SWEMWBS (6x), the PSS (5x), the EQ-5D (4x) and the ULS-4 (2x). All other measures are unique for the studies in which they are applied and use various measures for general psychological factors such as mental health, well-being, mood, depression, or more specific factors in times of COVID, such as loneliness, sleep quality, social support, and depression. See also .

Of these 44 studies, some report direct negative effects of the lockdown on diet and most report indirect effects, via increased stress, reduced well-being and comparable factors. The reported negative effects of the lockdown are increased weight or BMI, more binge-eating and an increase in the consumption of unhealthy foods. There are two studies that do not show a negative effect on diet (Rossinot et al. Citation2020; Barone Gibbs Citation2021), two studies that suggest a protective effect of the Mediterranean lifestyle (Biviá-Roig et al. Citation2020; Romero-Blanco et al. Citation2020), but also a study reporting that people follow the Mediterranean Diet less (Cirillo Citation2021). There are three studies that only report on (negative) changes in physical exercise, not in diet.

Many of these studies show indeed a negative effect on psychological factors such as negative moods (including less sleep), emotion dysregulation, lower quality of life and less social support. In terms of behaviour, next to the negative effects on diet, the lockdown leads to less exercise and more sitting time. All these effects, including the effects on diet, are not always present and if so, often in a minority of the participants. Some studies also show positive effects of the lockdown, when people try to counter these challenges, for example by doing more exercise (Amatori et al. Citation2020). One other interesting finding is a reduction in alcohol use (Ammar et al. Citation2020), which may be explained by the limitation of social contacts.

Not all effects are the same and also not all effects are negative. Sińska et al. (Citation2021) mentions that the highest adherence to the principles of appropriate nutrition was observed in individuals characterised by the ability to cope with difficult situations and those who quickly adapted to new changing circumstances. Wilson (Citation2021) mentions that fat intake has increased in part of the population but has decreased in another part in a comparable way. Bell (Citation2021) reports more behaviour changes (including diet) in a healthy direction than an unhealthy direction, which are associated with more relaxing behaviour and with helping the neighbours. Sheng (Citation2021) reports that perceived severity of coping results in more eating problems at the social level, but fewer eating problems at the individual level. Berge (Citation2021) suggests that people who have family-shared meals more often, show higher levels of mental wellbeing. Finally, Nashwan et al. (Citation2020) reports that nurses in COVID-19 care are more often emotional eaters, but their social support is still the same.

Discussion

As it is known that psychological factors might influence subsequent behaviour (see e.g. Peters Citation2014), knowledge of these psychological factors may help to be better inform future interventions. With that, we can better prepare ourselves in case of future lockdown scenario’s. Therefore, the aim of this scoping review was to provide an overview of what psychological factors may be associated with peoples’ eating behaviour during COVID-19 restrictions. The main finding of this scoping review is that several psychological factors significantly influenced individuals’ eating habits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the results of the most recent publications that report on peoples’ eating behaviour during the pandemic, show an increase of food consumption (sometimes more healthy, but often more unhealthy), potentially contributing to weight gains during the pandemic. Overall, most people engaged in unhealthier diets during confinement compared to before, but some also in healthier diets.

The analysis yielded that psychological factors, such as negative affective reactions, anxiety and fear of COVID-19, stress, and subjective and mental wellbeing, had an impact on individual’s eating behaviour, and mostly a negative impact. There was a heightened level of experienced stress during the pandemic, which was found to be associated with weight gain and increased food consumption. One potential explanation for this link is a decrease in weight gain protective behaviours, meaning that people increasingly engage in emotional eating or binge eating, exercise less, and consume more and more unhealthy food.

Furthermore, altered anxiety levels were linked to COVID-19, causing changes in dietary habits: People consumed, for instance, more salt, fried foods, and sugary foods, had a higher fat intake, and increased episodes of binge eating and emotional eating. Anxiety was also associated with weight gain, poor appetite, and overeating. Fear of catching the COVID-19 virus caused people to eat irregularly and also altered their food choices.

Higher levels of depression and negative mood during the pandemic, often caused by social isolation and safety restrictions, also predicted a shift in eating habits. Generally, the articles reviewed reported an increase in depression levels, which was on the one hand associated with decreased food consumption, especially among women, and poor appetite. On the other hand, it was associated with binge eating, emotional eating, external eating, weight gain, and overeating. Similarly, a general negative mood led to poorer diets during the pandemic, causing people to eat and snack more, and to eat foods of low nutritional value.

Lockdowns and other measures restricted many people’s daily activities like going to the cinema or shopping with friends, and our review showed that boredom was associated with an increase in emotional eating, cause weight gain, and unhealthy and unvaried food choices. A similar pattern was observed for reductions in quality of life, which was linked to emotional eating and unhealthy food consumption.

This review has shown that several psychological factors influence individuals’ dietary behaviour during the pandemic, and that generally, these were negative psychological factors that negatively influenced individuals’ eating patterns. Importantly, choice motives can be relevant influential factor in this domain, and these may also have altered due to the pandemic and the imposed restrictions. Along these lines, stress can also act as a food choice motive to influence food consumption. Before the pandemic, food choice motives like the price or the sensory appeal of a certain food product were central determinant (Shen et al. Citation2020). According to Shen and colleagues (Citation2020), it is very likely that psychological factors can also become food choice motives, especially during times of COVID-19. For instance, when people experience stress during the lockdown, the price of a certain product might not be the first motivator anymore to purchase the product, but rather the experience of stress may cause people to purchase unhealthy food (Marchitelli et al. Citation2020). In this light, the influence of impulsivity on food purchase and food intake, in interaction with – and/or as a result of – stress may be an important focus of future (review) studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on our lifestyle behaviours (see e.g. Van Blyderveen et al. Citation2016).

This review also clearly illustrated that COVID-19, and in particular the restrictions imposed to curb the spread of the disease, does not only pose a threat for humans’ physical health, but also for their mental health. Negative effects are not restricted to the fear of catching the virus but extend to decreased well-being and an increase of anxiety and depression. Thus, it becomes increasingly important to reduce, as far as possible, the associated negative effects. One possibility would be to promote physical activity, as some authors indeed have suggested. During the lockdown physical activities were reduced, mostly because of physical limitations, which in turn was related to decreased mental health (e.g. Al-Musharaf Citation2020; Rossinot et al. Citation2020; Ruíz-Roso, de Carvalho Padilha, Mantilla-Escalante, Ulloa, et al. Citation2020; Ruíz-Roso, de Carvalho Padilha, Matilla-Escalante, Brun, et al. Citation2020). The study by Santhi et al. (Citation2018), showed that there is a link between physical activity, stress, depression, anxiety and quality of life. Engaging in regular exercise and physical activity can reduce depression, anxiety and stress and improve quality of life. Therefore, exercising regularly would be one opportunity to indirectly reduce the impact that COVID-19 has on peoples’ mental health, by influencing the psychological factors that were investigated in this review.

Limitations and implications

This systematic literature review has several limitations. First, we based our search on 30 different countries, which all introduced different safety restrictions. This means that we contribute to a global overview of the pandemic, but also that results need to be generalised with caution. Second, we only screened four databases, meaning that there might be some articles published elsewhere that were not assessed for this review. Third, it is important to realise that these studies describe the effects of the lockdown on behaviours and wellbeing as experienced by people and measured at one moment in time; the data do not allow for causal conclusions about (indirect) effects, as some of the authors claim. It is likely that the lockdown has caused changes in psychological factors and that those changes have resulted in different eating behaviours. However, the type of studies represented here cannot confirm the causality in that process.

The results from the studies reported here provide starting points for health promotion efforts in preparation of and during future pandemics. For example, Deschasaux-Tanguy et al. (Citation2021, 931–936) describes three groups in their study population of over 50.000 French participants. Cluster 1, the no change group, are “individuals with probably less lifestyle/environment disruption during the lockdown or those with well-established habits”. Cluster 2, the group displaying unfavourable changes in food and physical activity during the lockdown, “seemingly associated with being female, working from home, and the presence of children at home, lower income, higher pre-lockdown consumption of ultra-processed foods, and more depressive symptoms”. In contrast, people in cluster 3 worked on balancing their diet during the lockdown to improve its quality or to compensate for the loss of PA, which are “individuals more likely to have the financial means, knowledge, and time to invest in health-promoting behaviors”. It is the second group who are unprepared for a lockdown and, unsurprisingly, shows all the characteristics of what health promotors call the “less easy to reach” group. This means that there is a whole body of knowledge already available to prepare people, especially those less easy to reach, for a possible next lockdown.

To better prepare for a future pandemic, research should, among others, focus on the behaviours of those people who adapted relatively better to this COVID-19 pandemic, and find out how they managed to do so. For example, physical activity might help with better nutritional choices and the reduction in physical activity was especially present in people who were dependent on organised sports and not in people who exercised by themselves and the last group showed better health outcomes. Higher health literacy was shown to help people deal better with this crisis. Health promotors have been developing methods and strategies for reaching various targets for behaviour change, based on careful analyses of performance objectives and their psycho-social determinants. For example, Intervention Mapping (Bartholomew-Eldredge et al. Citation2016; Kok et al. Citation2016) describes a series of steps, tasks, and processes to help health promotion planners develop theory- and evidence-based programs, targeting individuals as well as agents who are responsible for the social and physical environment.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review shows that the COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on peoples’ eating behaviour, often but not always in a negative way, and it illustrates furthermore that various psychological factors had a role in that process. During a pandemic lockdown, an increase in bodyweight is very likely. Our analysis of 118 papers showed that after the lockdown, factors like depression, stress, anxiety and negative mood influenced food consumption, most commonly in a negative way. This review also identified additional factors like quality of life and fear of COVID-19 that have a negative impact. Targeting these psychological factors is important to prevent overweight among a society during a lockdown. Moreover, addressing peoples’ eating behaviour is important because a healthy diet positively influences our immune system, which might prevent the further spread of the disease. More research is needed to better understand (1) the long-term consequences that COVID-19 has on individuals’ diet, and (2) how we can be better prepared to deal with eating behaviour in case of another lockdown.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All available information is presented in the manuscript and in the additional files.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agurto HS, Alcantara-Diaz AL, Espinet-Coll E, Toro-Huamanchumo CJ. 2021. Eating habits, lifestyle behaviors and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic quarantine among Peruvian adults. PeerJ. 9:e11431.

- Alenko A, Agenagnew L, Beressa G, Tesfaye Y, Woldesenbet YM, Girma S. 2021. COVID-19-related anxiety and its association with dietary diversity score among health care professionals in Ethiopia: a web-based survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 14:987–996.

- Al-Musharaf S. 2020. Prevalence and predictors of emotional eating among healthy young Saudi women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. 12(10):2923.

- Alon-Tirosh M, Hadar-Shoval D, Asraf K, Tannous-Haddad L, Tzischinsky O. 2021. The association between lifestyle changes and psychological distress during COVID-19 lockdown: the moderating role of COVID-related stressors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(18):9695.

- Alothman SA, Alghannam AF, Almasud AA, Altalhi AS, Al-Hazzaa HM. 2021. Lifestyle behaviors trend and their relationship with fear level of COVID-19: cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. PLoS One. 16(10):e0257904.

- Amatori S, Donati Zeppa S, Preti A, Gervasi M, Gobbi E, Ferrini F, Rocchi MBL, Baldari C, Perroni F, Piccoli G, et al. 2020. Dietary habits and psychological states during COVID-19 home isolation in Italian college students: the role of physical exercise. Nutrients. 12(12):3660.

- Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, Bouaziz B, Bentlage E, How D, Ahmed M, et al. 2020. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behavior and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 12(6):1583.

- Ansah EW, Sarfo JO, Apaak D. 2020. Physical activity and dietary behaviors: a phenomenological analysis of experiences of Ghanaians during the COVID-19 lockdown. Pan Afr Med J. 37:199.

- Barbarossa MV, Fuhrmann J, Meinke JH, Krieg S, Varma HV, Castelletti N, Lippert T. 2020. Modeling the spread of COVID-19 in Germany: early assessment and possible scenarios. PLoS One. 15(9):e0238559.

- Barcın-Güzeldere HK, Devrim-Lanpir A. 2022. The association between body mass index, emotional eating and perceived stress during COVID-19 partial quarantine in healthy adults. Public Health Nutr. 25(1):43–50.

- Barone Gibbs B, Kline CE, Huber KA, Paley JL, Perera S. 2021. Covid-19 shelter-at-home and work, lifestyle and well-being in desk workers. Occupat Med. 71(2):86–94.

- Bartholomew-Eldredge LKB, Markham CM, Ruiter RA, Fernández ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. 2016. Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bell LM, Smith R, van de Venter EC, Shuttleworth C, Wilson K, Lycett D. 2021. COVID-19 stressors, wellbeing and health behaviours: a cross-sectional study. J Public Health. 43(3):e453–e461.

- Bemanian M, Mæland S, Blomhoff R, Rabben ÅK, Arnesen EK, Skogen JC, Fadnes LT. 2021. Emotional eating in relation to worries and psychological distress amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based survey on adults in Norway. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(1):130.

- Benfante A, Di Tella M, Romeo A, Castelli L. 2020. Traumatic stress in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: a review of the immediate impact. Front Psychol. 11:2816.

- Berge JM, Hazzard VM, Larson N, Hahn SL, Emery RL, Neumark-Sztainer D. 2021. Are there protective associations between family/shared meal routines during COVID-19 and dietary health and emotional well-being in diverse young adults? Prevent Med Rep. 24:101575.

- Bhutani S, Vandellen MR, Cooper JA. 2021. Longitudinal weight gain and related risk behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in adults in the US. Nutrients. 13(2):671.

- Biviá-Roig G, La Rosa VL, Gómez-Tébar M, Serrano-Raya L, Amer-Cuenca JJ, Caruso S, Commodari E, Barrasa-Shaw A, Lisón JF. 2020. Analysis of the impact of the confinement resulting from COVID-19 on the lifestyle and psychological wellbeing of Spanish pregnant women: an internet-based cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(16):5933.

- Bonaccio M, Costanzo S, Bracone F, Gialluisi A, Di Castelnuovo A, Ruggiero E, Esposito S, Olivieri M, Persichillo M, Cerletti C, et al. 2021. Psychological distress resulting from the COVID-19 confinement is associated with unhealthy dietary changes in two Italian population-based cohorts. Eur J Nutr. 61(3):1491–1505.

- Borgatti AC, Schneider-Worthington CR, Stager LM, Krantz OM, Davis AL, Blevins M, Howell CR, Dutton GR. 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic and weight management: effective behaviors and pandemic-specific risk factors. Obes Res Clin Pract. 15(5):518–521.

- Camilleri GM, Méjean C, Kesse-Guyot E, Andreeva VA, Bellisle F, Hercberg S, Péneau S. 2014. The associations between emotional eating and consumption of energy-dense snack foods are modified by sex and depressive symptomatology. J Nutr. 144(8):1264–1273.

- Cecchetto C, Aiello M, Gentili C, Ionta S, Osimo SA. 2021. Increased emotional eating during COVID-19 associated with lockdown, psychological and social distress. Appetite. 160:105122.

- Chopra S, Ranjan P, Singh V, Kumar S, Arora M, Hasan MS, Kasiraj R, Suryansh , Kaur D, Vikram NK, et al. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on lifestyle-related behaviours-a cross-sectional audit of responses from nine hundred and ninety-five participants from India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 14(6):2021–2030.

- Cirillo M, Rizzello F, Badolato L, De Angelis D, Evangelisti P, Coccia ME, Fatini C. 2021. The effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle and emotional state in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology: results of an Italian survey. J Gynecol Obstet Human Reprod. 50(8):102079.

- Coakley KE, Le H, Silva SR, Wilks A. 2021. Anxiety is associated with undesirable eating behaviors in university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutr J. 20:45.

- Coulthard H, Sharps M, Cunliffe L, van den Tol A. 2021. Eating in the lockdown during the Covid 19 pandemic; self-reported changes in eating behaviour, and associations with BMI, eating style, coping and health anxiety. Appetite. 161:105082.

- Cummings JR, Wolfson JA, Gearhardt AN. 2022. Health-promoting behaviors in the United States during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Appetite. 168:105659.

- Davila-Torres DM, Vilcas-Solís GE, Rodríguez-Vásquez M, Calizaya-Milla YE, Saintila J. 2021. Eating habits and mental health among rugby players of the Peruvian pre-selection during the second quarantine due to the COVID-19 pandemic. SAGE Open Med. 9:20503121211043718.

- De Backer C, Teunissen L, Cuykx I, Decorte P, Pabian S, Gerritsen S, Matthys C, Al Sabbah H, Van Royen K, et al. 2021. An evaluation of the COVID-19 pandemic and perceived social distancing policies in relation to planning, selecting, and preparing healthy meals: an observational study in 38 countries worldwide. Front Nutr. 7:621726.

- Deschasaux-Tanguy M, Druesne-Pecollo N, Esseddik Y, De Edelenyi FS, Allès B, Andreeva VA, Baudry J, Charreire H, Deschamps V, Egnell M, et al. 2021. Diet and physical activity during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown (March–May 2020): results from the French NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 113(4):924–938.

- Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Cinelli G, Bigioni G, Soldati L, Attinà A, Bianco FF, Caparello G, Camodeca V, Carrano E, et al. 2020. Psychological aspects and eating habits during COVID-19 home confinement: results of EHLC-COVID-19 Italian online survey. Nutrients. 12(7):2152.

- Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F, Soldati L, Attinà A, Cinelli G, Leggeri C, Caparello G, Barrea L, Scerbo F, et al. 2020. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey. J Transl Med. 18:229.

- Du C, Zan MCH, Cho MJ, Fenton JI, Hsiao PY, Hsiao R, Keaver L, Lai CC, Lee H, Ludy MJ, et al. 2021. Health behaviors of higher education students from 7 countries: poorer sleep quality during the COVID-19 pandemic predicts higher dietary risk. Clocks Sleep. 3(1):12–30.

- Enriquez-Martinez OG, Martins MCT, Pereira TSS, Pacheco SOS, Pacheco FJ, Lopez KV, Huancahuire-Vega S, Silva DA, Mora-Urda AI, Rodriguez-Vásquez M, et al. 2021. Diet and lifestyle changes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ibero-American countries: Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, and Spain. Front Nutr. 8:671004.

- Flaudias V, Iceta S, Zerhouni O, Rodgers RF, Billieux J, Llorca PM, Boudesseul J, de Chazeron I, Romo L, Maurage P, et al. 2020. COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and problematic eating behaviors in a student population. J Behav Addict. 9(3):826–835.

- Freitas FDF, de Medeiros ACQ, Lopes FDA. 2021. Effects of social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and eating behavior—a longitudinal study. Front Psychol. 12:645754.

- Gao Y, Ao H, Hu X, Wang X, Huang D, Huang W, Han Y, Zhou C, He L, Lei X, et al. 2022. Social media exposure during covid‐19 lockdowns could lead to emotional overeating via anxiety: the moderating role of neuroticism. Appl Psychol Health Wellbeing. 14(1):64–80.

- García-Esquinas E, Ortolá R, Gine-Vázquez I, Carnicero JA, Mañas A, Lara E, Alvarez-Bustos A, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Sotos-Prieto M, Olaya B, et al. 2021. Changes in health behaviors, mental and physical health among older adults under severe lockdown restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(13):7067.

- Garre-Olmo J, Turró-Garriga O, Martí-Lluch R, Zacarías-Pons L, Alves-Cabratosa L, Serrano-Sarbosa D, Vilalta-Franch J, Ramos R. 2021. Changes in lifestyle resulting from confinement due to COVID-19 and depressive symptomatology: a cross-sectional a population-based study. Compr Psychiatry. 104:152214.

- Grove JR, Prapavessis H. 1992. Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of an abbreviated profile of mood states. Int J Sport Psychol. 23(2):93–109.

- Guerrini Usubini A, Cattivelli R, Varallo G, Castelnuovo G, Molinari E, Giusti EM, Pietrabissa G, Manari T, Filosa M, Franceschini C, et al. 2021. The relationship between psychological distress during the second wave lockdown of COVID-19 and emotional eating in Italian young adults: the mediating role of emotional dysregulation. J Pers Med. 11(6):569.

- Gutiérrez-Pérez IA, Delgado-Floody P, Jerez-Mayorga D, Soto-García D, Caamaño-Navarrete F, Parra-Rojas I, Molina-Gutiérrez N, Guzmán-Guzmán IP. 2021. Lifestyle and sociodemographic parameters associated with mental and physical health during COVID-19 confinement in three Ibero-American countries. A cross-sectional pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(10):5450.

- Haddad C, Zakhour M, Haddad R, Al Hachach M, Sacre H, Salameh P. 2020. Association between eating behavior and quarantine/confinement stressors during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. J Eat Disord. 8(1):1–12.

- Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, Coleman SM, Heeren T, Rose-Jacobs R, Cook JT, Ettinger de Cuba SA, Casey PH, Chilton M, et al. 2010. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 126(1):e26–e32.

- Herle M, Smith AD, Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. 2021. Trajectories of eating behavior during COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal analyses of 22,374 adults. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 42:158–165.

- Hu Z, Lin X, Chiwanda Kaminga A, Xu H. 2020. Impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on lifestyle behaviors and their association with subjective well-being among the general population in mainland China: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 22(8):e21176.

- Huber BC, Steffen J, Schlichtiger J, Brunner S. 2020. Altered nutrition behavior during COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in young adults. Eur J Nutr. 60(5):2593–2602.

- Ingram J, Maciejewski G, Hand CJ. 2020. Changes in diet, sleep, and physical activity are associated with differences in negative mood during COVID-19 lockdown. Front Psychol. 11:588604.

- Jalal SM, Beth M, Al-Hassan H, Alshealah N. 2021. Body mass index, practice of physical activity and lifestyle of students during COVID-19 lockdown. J Multidiscip Healthcare. 14:1901–1910.

- Jansen E, Thapaliya G, Aghababian A, Sadler J, Smith K, Carnell S. 2021. Parental stress, food parenting practices and child snack intake during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appetite. 161:105119.

- Jeżewska-Zychowicz M, Plichta M, Królak M. 2020. Consumers’ fears regarding food availability and purchasing behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: the importance of trust and perceived stress. Nutrients. 12(9):2852.

- Jimenez A, de Hollanda A, Palou E, Ortega E, Andreu A, Molero J, Mestre C, Ibarzabal A, Obach A, Flores L, et al. 2021. Psychosocial, lifestyle, and body weight impact of COVID-19-related lockdown in a sample of participants with current or past history of obesity in Spain. Obes Surg. 31(5):2115–2124.

- Kalkan Uğurlu Y, Mataracı Değirmenci D, Durgun H, Gök Uğur H. 2021. The examination of the relationship between nursing students’ depression, anxiety and stress levels and restrictive, emotional, and external eating behaviors in COVID‐19 social isolation process. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 57(2):507–516.

- Yılmaz SK, Eskici G. 2021. Evaluation of emotional (depression) and behavioural (nutritional, physical activity and sleep) status of Turkish adults during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Public Health Nutr. 24(5):942–949.

- Kaufman-Shriqui V, Navarro DA, Raz O, Boaz M. 2021. Multinational dietary changes and anxiety during the coronavirus pandemic-findings from Israel. Isr J Health Policy Res. 10(1):1–11.

- Kaya S, Uzdil Z, Cakiroğlu FP. 2021. Evaluation of the effects of fear and anxiety on nutrition during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Public Health Nutr. 24(2):282–289.

- Keenan GS, Christiansen P, Hardman CA. 2021. Household food insecurity, diet quality, and obesity: an explanatory model. Obesity. 29(1):143–149.

- Keenan GS, Christiansen P, Owen LJ, Hardman CA. 2022. The association between COVID-19 related food insecurity and weight promoting eating behaviours: the mediating role of distress and eating to cope. Appetite. 169:105835.

- Kekäläinen T, Hietavala EM, Hakamäki M, Sipilä S, Laakkonen EK, Kokko K. 2021. Personality traits and changes in health behaviors and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis from pre-pandemic to onset and end of the initial emergency conditions in Finland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(15):7732.

- Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters G-JY, Mullen PD, Parcel GS, Ruiter RAC, Fernández ME, Markham C, Bartholomew LK. 2016. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. 10(3):297–312.

- Kowalczuk I, Gębski J. 2021. Impact of fear of contracting covid-19 and complying with the rules of isolation on nutritional behaviors of polish adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(4):1631.

- LaCaille LJ, Hooker SA, Marshall E, LaCaille RA, Owens R. 2021. Change in perceived stress and health behaviors of emerging adults in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Behav Med. 55(11):1080–1088.

- Landaeta-Díaz L, González-Medina G, Agüero SD. 2021. Anxiety, anhedonia and food consumption during the COVID-19 quarantine in Chile. Appetite. 164:105259.

- Landaeta-Díaz L, Agüero SD, Vinueza-Veloz MF, Arias VC, Cavagnari BM, Ríos-Castillo I, Nava-González EJ, López SC, Ivankovich-Guillén S, Pérez-Armijo P, et al. 2021. Anxiety, Anhedonia, and related food consumption at the beginning of the COVID-19 quarantine in populations of Spanish-speaking Ibero-American countries: an online cross-sectional survey study. SSM Popul Health. 16:100933.

- Larson NI, Wall MM, Story MT, Neumark‐Sztainer DR. 2013. Home/family, peer, school, and neighborhood correlates of obesity in adolescents. Obesity. 21(9):1858–1869.

- Lehtisalo J, Palmer K, Mangialasche F, Solomon A, Kivipelto M, Ngandu T. 2021. Changes in lifestyle, behaviors, and risk factors for cognitive impairment in older persons during the first wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in Finland: results from the FINGER study. Front Psychiatry. 12:21.

- León-Paucar SD, Calderón-Olivos BC, Calizaya-Milla YE, Saintila J. 2021. Depression, dietary intake, and body image during coronavirus disease 2019 quarantine in Peru: an online cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 9:20503121211051914.

- Li Q, Xiang G, Song S, Li X, Liu Y, Wang Y, Luo Y, Xiao M, Chen H. 2021. Trait self-control and disinhibited eating in COVID-19: the mediating role of perceived mortality threat and negative affect. Appetite. 167:105660.

- Liboredo JC, Anastácio LR, Ferreira LG, Oliveira LA, Della Lucia CM. 2021. Quarantine during COVID-19 Outbreak: eating behavior, perceived stress, and their independently associated factors in a Brazilian sample. Front Nutr. 8:704619.

- López-Moreno M, López MTI, Miguel M, Garcés-Rimón M. 2020. Physical and psychological effects related to food habits and lifestyle changes derived from COVID-19 home confinement in the Spanish population. Nutrients. 12(11):3445.

- Madalı B, Alkan ŞB, Örs ED, Ayrancı M, Taşkın H, Kara HH. 2021. Emotional eating behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 46:264–270.

- Marchitelli S, Mazza C, Lenzi A, Ricci E, Gnessi L, Roma P. 2020. Weight gain in a sample of patients affected by overweight/obesity with and without a psychiatric diagnosis during the Covid-19 lockdown. Nutrients. 12(11):3525.

- Marty L, de Lauzon-Guillain B, Labesse M, Nicklaus S. 2021. Food choice motives and the nutritional quality of diet during the COVID-19 lockdown in France. Appetite. 157:105005.

- Mason TB, Barrington-Trimis J, Leventhal AM. 2021. Eating to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic and body weight change in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 68(2):277–283.

- Mata J, Wenz A, Rettig T, Reifenscheid M, Möhring K, Krieger U, Friedel S, Fikel M, Cornesse C, Blom AG, et al. 2021. Health behaviors and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal population-based survey in Germany. Soc Sci Med. 287:114333.

- Matsungo TM, Chopera P. 2020. Effect of the COVID-19-induced lockdown on nutrition, health and lifestyle patterns among adults in Zimbabwe. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. 3(2):205–212.

- Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, Colasanti M, Ferracuti S, Napoli C, Roma P. 2020. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(9):3165.

- McAtamney K, Mantzios M, Egan H, Wallis DJ. 2021. Emotional eating during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom: exploring the roles of alexithymia and emotion dysregulation. Appetite. 161:105120.

- Modrzejewska A, Czepczor-Bernat K, Modrzejewska J, Matusik P. 2021. Eating motives and other factors predicting emotional overeating during COVID-19 in a sample of Polish adults. Nutrients. 13(5):1658.

- Nashwan AJ, Villar RC, Al-Qudimat AR, Kader N, Alabdulla M, Abujaber AA, Al-Jabry MM, Harkous M, Philip A, Ali R, et al. 2020. Weight-related lifestyle behaviors and the COVID-19 crisis: an online survey study of UK adults during social lockdown. Obes Sci Pract. 6(6):735–740. ()()()

- Ortenburger D, Mosler D, Pavlova I, Wąsik J. 2021. Social support and dietary habits as anxiety level predictors of students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(16):8785.

- Owen AJ, Tran T, Hammarberg K, Kirkman M, Fisher JR. 2021. Poor appetite and overeating reported by adults in Australia during the coronavirus-19 disease pandemic: a population-based study. Public Health Nutr. 24(2):275–281.

- Pak H, Süsen Y, Denizci Nazlıgül M, Griffiths M. 2021. The mediating effects of fear of COVID-19 and depression on the association between intolerance of uncertainty and emotional eating during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Int J Ment Health Addic. 20(3):1882–1896.

- Papandreou C, Arija V, Aretouli E, Tsilidis KK, Bulló M. 2020. Comparing eating behaviours, and symptoms of depression and anxiety between Spain and Greece during the COVID‐19 outbreak: cross‐sectional analysis of two different confinement strategies. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 28(6):836–846.

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. 2020. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behavior Immun. 88:901–907.

- Park KH, Kim AR, Yang MA, Lim SJ, Park JH. 2021. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyle, mental health, and quality of life of adults in South Korea. PLoS One. 16(2):e0247970.

- Park KH, Kim AR, Yang MA, Park JH. 2021. Differences in multi-faceted lifestyles in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and their association with depression and quality of life of older adults in south korea: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 13(11):4124.

- Pellegrini M, Ponzo V, Rosato R, Scumaci E, Goitre I, Benso A, Belcastro S, Crespi C, De Michieli F, Ghigo E, et al. 2020. Changes in weight and nutritional habits in adults with obesity during the “lockdown” period caused by the COVID-19 virus emergency. Nutrients. 12(7):2016.

- Peters G-JY. 2014. A practical guide to effective behavior change: how to identify what to change in the first place. Eur Health Psychol. 16(4):142–155.

- Pirrone C, Di Corrado D, Privitera A, Castellano S, Varrasi S. 2022. Students’ mathematics anxiety at distance and in-person learning conditions during COVID-19 pandemic: are there any differences? An exploratory study. Educ Sci. 12(6):379.

- Pope J, Olander EK, Leitao S, Meaney S, Matvienko-Sikar K. 2022. Prenatal stress, health, and health behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international survey. Women Birth. 35(3):272–279.

- Prete M, Luzzetti A, Augustin LS, Porciello G, Montagnese C, Calabrese I, Ballarin G, Coluccia S, Patel L, Vitale S, et al. 2021. Changes in lifestyle and dietary habits during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: results of an online survey. Nutrients. 13(6):1923.

- Robertson M, Duffy F, Newman E, Bravo CP, Ates HH, Sharpe H. 2021. Exploring changes in body image, eating and exercise during the COVID-19 lockdown: a UK survey. Appetite. 159:105062.

- Robinson SM, Jameson KA, Bloom I, Ntani G, Crozier SR, Syddall H, Dennison EM, Cooper CR, Sayer AA. 2017. Development of a short questionnaire to assess diet quality among older community-dwelling adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 21:247–253.

- Robinson E, Boyland E, Chisholm A, Harrold J, Maloney NG, Marty L, Mead BR, Noonan R, Hardman CA. 2021. Obesity, eating behavior and physical activity during COVID-19 lockdown: a study of UK adults. Appetite. 156:104853.

- Rodríguez-Pérez C, Molina-Montes E, Verardo V, Artacho R, García-Villanova B, Guerra-Hernández EJ, Ruíz-López MD. 2020. Changes in dietary behaviors during the COVID-19 outbreak confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet study. Nutrients. 12(6):1730.

- Romero-Blanco C, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Onieva-Zafra MD, Parra-Fernández ML, Prado-Laguna MDC, Hernández-Martínez A. 2020. Physical activity and sedentary lifestyle in university students: changes during confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(18):6567.

- Rossinot H, Fantin R, Venne J. 2020. Behavioral changes during COVID-19 confinement in France: a web-based study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(22):8444.

- Ruíz-Roso MB, de Carvalho Padilha P, Mantilla-Escalante DC, Ulloa N, Brun P, Acevedo-Correa D, Arantes Ferreira Peres W, Martorell M, Aires MT, de Oliveira Cardoso L, et al. 2020. Covid-19 confinement and changes of adolescent’s dietary trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. Nutrients. 12(6):1807.

- Ruíz-Roso MB, de Carvalho Padilha P, Matilla-Escalante DC, Brun P, Ulloa N, Acevedo-Correa D, Arantes Ferreira Peres W, Martorell M, Rangel Bousquet Carrilho T, de Oliveira Cardoso L, et al. 2020. Changes of physical activity and ultra-processed food consumption in adolescents from different countries during COVID-19 pandemic: an observational study. Nutrients. 12(8):2289.

- Ruiz MC, Devonport TJ, Chen-Wilson C-HJ, Nicholls W, Cagas JY, Fernandez-Montalvo J, Choi Y, Robazza C. 2020. A cross-cultural exploratory study of health behaviors and wellbeing during COVID-19. Front Psychol. 11:608216.

- Sadler JR, Thapaliya G, Jansen E, Aghababian AH, Smith KR, Carnell S. 2021. COVID-19 stress and food intake: protective and risk factors for stress-related palatable food intake in US adults. Nutrients. 13(3):901.

- Sagaribay III, R, Frietze G, Lerma M, Perez MG, Louden JE, Cooper TV. 2022. A prospective analysis of loss of control over eating, sociodemographics, and mental health during COVID-19 in the United States. Obes Res Clin Pract. 16(1):87–90.

- Salazar-Fernández C, Palet D, Haeger PA, Román Mella F. 2021. The perceived impact of COVID-19 on comfort food consumption over time: the mediational role of emotional distress. Nutrients. 13(6):1910.

- Sánchez-Sánchez E, Díaz-Jimenez J, Rosety I, Alférez MJM, Díaz AJ, Rosety MA, Ordonez FJ, Rosety-Rodriguez M. 2021. Perceived stress and increased food consumption during the ‘third wave’of the covid-19 pandemic in Spain. Nutrients. 13(7):2380.

- Sanlier N, Kocabas Ulusoy HG, Celik B., Ş 2022. The relationship between adults’ perceptions, attitudes of COVID-19, intuitive eating, and mindful eating behaviors. Ecol Food Nutr. 61(1):90–109.

- Santhi S, Samson R, Srikanth PD. 2018. Effectiveness of physical activity on depression, anxiety, stress and quality of life of patients on hemodialysis. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 8(8):1194–1199.

- Sato K, Kobayashi S, Yamaguchi M, Sakata R, Sasaki Y, Murayama C, Kondo N. 2021. Working from home and dietary changes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study of health app (CALO mama) users. Appetite. 165:105323.

- Savarese M, Castellini G, Morelli L, Graffigna G. 2021. COVID-19 disease and nutritional choices: how will the pandemic reconfigure our food psychology and habits? A case study of the Italian population. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 31(2):399–402.

- Scarmozzino F, Visioli F. 2020. Covid-19 and the subsequent lockdown modified dietary habits of almost half the population in an Italian sample. Foods. 9(5):675.

- Shen W, Long LM, Shih CH, Ludy MJ. 2020. A humanities-based explanation for the effects of emotional eating and perceived stress on food choice motives during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. 12(9):2712.

- Sheng R, Yang X, Zhou Y, Liu X, Xu W. 2021. COVID-19 and eating problems in daily life: the mediating roles of stress, negative affect and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychol Rep. 126(1):34–51.

- Shimpo M, Akamatsu R, Kojima Y, Yokoyama T, Okuhara T, Chiba T. 2021. Factors Associated with Dietary Change since the Outbreak of COVID-19 in Japan. Nutrients. 13(6):2039.

- Simone M, Emery RL, Hazzard VM, Eisenberg ME, Larson N, Neumark‐Sztainer D. 2021. Disordered eating in a population‐based sample of young adults during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Int J Eat Disord. 54(7):1189–1201.

- Sińska B, Jaworski M, Panczyk M, Traczyk I, Kucharska A. 2021. The role of resilience and basic hope in the adherence to dietary recommendations in the polish population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. 13(6):2108.

- Smith KR, Jansen E, Thapaliya G, Aghababian AH, Chen L, Sadler JR, Carnell S. 2021. The influence of COVID-19-related stress on food motivation. Appetite. 163:105233.

- Snuggs S, McGregor S. 2021. Food & meal decision making in lockdown: how and who has Covid-19 affected? Food Qual Prefer. 89:104145.

- Sohrabietal C, Alsafi Z, O’Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha R. 2020. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 76:71–76.

- Szwarcwald CL, Damacena GN, Barros M, Malta DC, Souza Júnior P, Azevedo LO, Machado ÍE, Lima MG, Romero D, Gomes CS, et al. 2021. Factors affecting Brazilians’ self-rated health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cadernos De Saude Publica. 37(3):e00182720.

- Tran TV, Nguyen HC, Pham LV, Nguyen MH, Nguyen HC, Ha TH, Phan DT, Dao HK, Nguyen PB, Trinh MV, et al. 2020. Impacts and interactions of COVID-19 response involvement, health-related behaviours, health literacy on anxiety, depression and health-related quality of life among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 10(12):e041394.

- Tribst A, Tramontt CR, Baraldi LG. 2021. Factors associated with diet changes during the COVID-19 pandemic period in Brazilian adults: time, skills, habits, feelings and beliefs. Appetite. 163:105220.

- Van Blyderveen S, Lafrance A, Emond M, Kosmerly S, O'Connor M, Chang F. 2016. Personality differences in the susceptibility to stress-eating: the influence of emotional control and impulsivity. Eat Behav. 23:76–81.

- Vandevijvere S, De Ridder K, Drieskens S, Charafeddine R, Berete F, Demarest S. 2021. Food insecurity and its association with changes in nutritional habits among adults during the COVID-19 confinement measures in Belgium. Public Health Nutr. 24(5):950–956.

- Vitman-Schorr AV, Yehuda I, Tamir S. 2021a. Loneliness, malnutrition and change in subjective age among older adults during COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(1):106.

- Vitman-Schorr AV, Yehuda I, Tamir S. 2021b. Ethnic differences in loneliness, depression, and malnutrition among older adults during COVID-19 quarantine. J Nutr Health Aging. 25(3):311–317.

- Wang X, Lei SM, Le S, Yang Y, Zhang B, Yao W, Gao Z, Cheng S. 2020. Bidirectional influence of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns on health behaviors and quality of life among chinese adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(15):5575.

- Wilson JJ, McMullan I, Blackburn NE, Klempel N, Yakkundi A, Armstrong NC, Brolly C, Butler LT, Barnett Y, Jacob L, et al. 2021. Changes in dietary fat intake and associations with mental health in a UK public sample during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Public Health. 43(4):687–694.

- Xie J, Li X, Luo H, He L, Bai Y, Zheng F, Zhang L, Ma J, Niu Z, Qin Y, Wang L, et al. 2021. Depressive symptoms, sleep quality and diet during the 2019 novel coronavirus epidemic in China: a survey of medical students. Front Public Health. 8: 588578.

- Xu Y, Li Z, Yu W, He X, Ma Y, Cai F, Liu Z, Zhao R, Wang D, Guo YF, et al. 2020. The association between subjective impact and the willingness to adopt healthy dietary habits after experiencing the outbreak of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a cross-sectional study in China. Aging. 12(21):20968.

- Ye B, Wang R, Liu M, Wang X, Yang Q. 2021. Life history strategy and overeating during COVID-19 pandemic: a moderated mediation model of sense of control and coronavirus stress. J Eat Disord. 9:1–12.

- Zachary Z, Brianna F, Brianna L, Garrett P, Jade W, Alyssa D, Mikayla K. 2020. Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes Res Clin Pract. 14(3):210–216.

- Znazen H, Slimani M, Bragazzi NL, Tod D. 2021. The relationship between cognitive function, lifestyle behaviours and perception of stress during the COVID-19 induced confinement: insights from correlational and mediation analyses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(6):3194.