Abstract

Is audit capable of evolving into something that is more consistently valued and socially purposeful? We address this fundamental question, utilizing Sennett’s (2008). The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press) notion of ‘dynamic repair’ to present four key ways of thinking differently about the statutory financial audit and its core conceptual foundations. First, we highlight the capacity for audit to be regarded as a first-order function of value in its own right rather than a second-order function inherently dependent on corporate financial statements. Second, we call for a change in the assumed relationship between audit and assurance, arguing that assurance should be treated as a sub-set of audit rather than the other way round. Third, we consider the scope for audit standard setting to provide a space for ‘product’ innovation. Finally, we advocate moving beyond presumptions that the current statutory financial audit serves ‘the public interest’ to asking deeper questions about the type of society we want to inhabit and whether audit has a more direct and valued contribution to make. Collectively, such re-conceptualizations offer a broader canvas for audit innovation and can help to sustain the promise of current audit reform initiatives proposed by the Brydon Report and others.

The simplest way to make a repair is to take something apart, find and fix what’s wrong, then restore the object to its former state. This could be called a static repair; it occurs, for instance, when the blown fuse in a toaster is replaced. A dynamic repair will change the object’s current form or function once it is reassembled… (Sennett, Citation2008, p. 200)

1. Introduction

Our primary motivation in writing this paper derives from a deep level of concern with the development and social significance of the statutory financial audit.Footnote1 Given the perennial nature of discussions over the audit expectations gap, the scale and frequency of major corporate scandals, the resulting questioning of the quality of audit, the regularity of investigations and official sanctions of the big audit firms, it is timely to ask where stands audit nowadays? How can audit evolve into something that is more consistently and vividly valued?

It is particularly worrying at the present time to see an increasing scale of criticism of the auditing profession, the efficacy of audit and its capability to serve the ‘public interest’ (e.g., Ford & Marriage, Citation2018; Jack, Citation2017; Williams, Citation2014). The auditing profession and its regulators have been talking for years of the importance of ‘restoring trust in audit’ (Brewster, Citation2003). Yet the continued calls for such restoration patently suggest that the requisite level of trust has yet to be achieved (Mueller et al., Citation2015; Unerman & O’Dwyer, Citation2004). The seemingly ever-rising scale and reach of regulation and the associated concern with the nature of regulatory reforms is accompanied by doubts as to whether the quality of audit practice is really improving (Sikka, Citation2018).

Since the emergence of audit in the UK in the nineteenth century, its history has come to be one written around cases of notable audit failure. Audit practice is routinely spoken of in terms of being pre- or post- a particular crisis, such as Enron or the global financial crisis. The most recent international string of corporate scandals such as Carillion and Wirecard, coupled with regulatory fines and sanctions have brought considerable reputational damage to the Big firms, and have even seen relatively conservative media outlets such as the Financial Times launch major investigative analyses of the ‘crisis’ facing the audit profession (Ford & Marriage, Citation2018; Marriage, Citation2018), while some authors have gone as far as implicating such firms in the demise of capitalism (see Brooks, Citation2018). With award winning audits of companies such as Rolls Royce subsequently ending up with damning criticism in the financial press,Footnote2 it is hard not to form the view that all the regulatory endeavor of the last 20 years has done little to eliminate the enduring problem of the audit expectations gap (Sikka, Citation2018). Furthermore, formal audit inspection reports repeatedly document unsatisfactorily high levels of audit deficiencies, with members of the International Forum of Independent Audit Regulators (IFIAR) reporting in the 2019 Inspection Findings Survey that 33% of audit inspections of firms affiliated with the six largest audit firm networks had deficiencies (IFIAR, Citation2020).

Despite 70 years of initiatives contemplating the ‘future of the audit’ (ICAEW, Citation1993, Citation1995, Citation2000; Smallpiece, Citation1981), reforms responding to the repeated cycle of audit failures have rarely questioned the conceptual underpinnings of audit in its traditional form. Reform proposals tend to focus on the implementation, delivery, regulation and inspection of audit, rather than audit itself and different conceptions of what it could represent. The most recent episode of the ‘audit in crisis’ debate in the UK has been dominated by proposals to strengthen the audit regulatory body, to establish ‘audit only’ firms, to make the audit market more competitive and even talk of the establishment of an independent audit appointments board (AFM, Citation2018; Sikka et al., Citation2009, Citation2018; Woolf, Citation2020). Regulatory efforts to repair and restore trust in auditing essentially focus on market and regulatory structures, while taking the audit for granted in terms of its form, purpose and social value.

The failure to question the current conception of audit and to revisit repeatedly proposals for reform is somewhat surprising given the scale of criticism of such reforms. For example, Peterson (Citation2015), in devoting 94 pages of his book to what he refers to as the ‘non-solutions’ to the problems of the current audit model, is left to conclude that the audit, as we have come to understand it, is fundamentally broken. This conclusion is likely to be disputed by those who categorize audit as a function with statutory and/or market institutional backing, but what cannot be disputed is that the search for new regulatory solutions, of presumed better ways of delivering the same old audit, is (a) not one with a great track record of success and (b) not an easy one to halt or break.

Current conceptions of audit continue to be fundamentally restricted in most jurisdictions to assuring the material accuracy of the financial statements, a secondary function at the end of the financial reporting supply chain. This paper is premised on the view that there is a need to break out of this conceptual conservatism to think differently, and to create space in which new conceptions of audit can emerge. Well over 25 years ago Flint (Citation1992), critical of the development of philosophical principles on which auditing practices were based and changed, concluded that

Auditing has developed as a collection of practices to meet specific objectives rather than as a social function of which the practices and the immediate objectives were the instruments i.e., these have been seen as the end whereas they should be regarded as the means to the end which is of a higher order. (p. 2)

We draw on Sennett’s (Citation2008, Citation2012) work on craftsmanship, and his notions of repair, to frame our argument for thinking differently about auditing. Sociologists are increasingly paying attention to the social significance of repair work, as the reliance in advanced economies on ‘make-use-dispose’ linear economic activity models are increasingly seen as unsustainable (see Bozkurt & Cohen, Citation2019). Driven by a craftsman’s curiosity to ask ‘why?’ and ‘how?’ in exploring notions of ‘problem solving’ and ‘problem finding,’ repair work embodies a range of complex human qualities and attributes. Sennett explains that in craft work the simplest form of repair is to take something apart, ‘find and fix what’s wrong and restore it to its former state’ (Sennett, Citation2008, p. 200). He contrasts this static repair with a dynamic repair, where creativity and imagination exercised during the reconfiguration processes can ‘change the object’s current form or function [and] may involve a jump of domains [or] invite new tools for working with’ (Sennett, Citation2008). In order to break out of the repeated cycle of regulatory reforms, Sennett’s work serves to inspire a very clear challenge: audit is in fundamental need of a dynamic repair.

In calling for dynamic repair of audit, our paper contributes a much broader consideration of the reconfiguration of audit than has been considered heretofore. Our objective is not about providing a single example of the outcome of such dynamic repair, rather the paper suggests multi-layered ways in which dynamic repair of auditing can be contemplated. We argue that the socially constructed objective of audit can be released from the current limited focus on corporate financial statements, recognizing the capacity of audit to become a first- rather than a second-order function. We call for a revision in the assumed relationship between audit and assurance, arguing that assurance should be treated as a sub-set of audit rather than the other way round, as this provides a broader canvas for conceptual innovation in audit. We point to the capacity for standard setting to focus more on product innovation than on consistency and compliance. Finally, we call for a re-think of the social value of audit, arguing for a move away from what the auditing profession currently undertakes ‘in the public interest’ to asking what type of a society we want to inhabit and to encourage a re-imagining of the concept of audit in ways that could make a more direct and valued contribution to society.

The remainder of the paper is set out as follows: section 2 explains Sennett’s concepts of static and dynamic repair, followed by section 3 which considers prior attempts at repair of the audit, which have largely cemented rather than questioned the existing concept of audit. Section 4 presents four conceptual reconfigurations that can help to provide the necessary foundational elements for the pursuit of a dynamic repair of audit. They are primarily intended to be illustrative of the scope to contemplate change and to provoke debate about the conceptual underpinnings of audit. Section 5 concludes the paper, considering the scope for dynamic repair offered by the recently published Brydon report in the UK (Brydon, Citation2019) which addresses the quality and effectiveness of audit.

2. The Conceptual Nature of Repair

There have been regular associations of auditing with the notion of craftsmanship. Numerous authors including Francis (Citation1990, Citation1994), Hanlon (Citation1994), Power (Citation1997) and Westermann et al. (Citation2015) have made reference to auditing as a craft. The mode of analysis in contemplating such craft work has typically been to consider the extent to which increasing commitments to standards and the codification of practice, coupled with the growth in internal firm monitoring practices and the rise of external regulation and inspection, have constrained or restricted the ‘craft’ of auditing (Westermann et al., Citation2015) – so much so, that the word ‘craft’ is typically written in inverted commas to suggest a degree of questioning and doubt as to whether auditing is now really capable of being described as a ‘craft.’

‘It is by fixing things that we often get to understand how they work’ (Sennett, Citation2008, p. 199). Such ‘live intelligence’ (p.199), ‘practical creativity’ (p. 30) and a moral imperative of working to high standards were virtues of craftsmanship which Sennett saw as deserving of greater consideration, especially in confronting assumptions regarding the capacity of markets and competition to stimulate good work and enhanced quality (Sennett, Citation2008, pp. 30–32). In building his analysis, Sennett made explicit reference to the traditional representation of Japan as a ‘nation of craftsmen’ and the associated underlying cultural imperatives to ‘work well for the common good’ (Sennett, Citation2008, p. 30; also see Fujimoto, Citation1999, Citation2018; Komori, Citation2008, Citation2015).Footnote3

Sennett’s (Citation2008) writing centers on understanding the essential functioning of craftsmanship and the contributions that it has made to human and scientific development. Of particular interest to our paper is his discussion of craft-like responses when an object stops working and is in need of repair. Sennett discusses three categories of repair: restoration which is to make a damaged object just like new; remediation which is to substitute better parts or materials to improve its operation, and reconfiguration which can change the object’s form or function once it is reassembled. In considering the potential contribution of the act of repair, Sennett distinguishes between static and dynamic repair (Sennett, Citation2012). He contrasts a static repair, which represents basic and routine restoration and remediation of an object to its former state with a dynamic repair, which involves reconfiguration, and which can change the object’s form or function once reassembled.

Sennett (Citation2012) sought to highlight the potential of dynamic repair to generate innovation; repair processes promote re-imagination and transform the object’s purpose as well as its functioning. In doing so, ‘fit-for-purpose’ tools are contrasted with ‘multipurpose tools’ that serve as curiosity’s instrument (Sennett, Citation2008, p. 200). Sennett regards ‘fit-for-purpose’ tools as being one-dimensional – efficient for their intended purpose but inherently frustrating when objects stop working and things go wrong. He refers to ‘multipurpose tools’ as being sublime (‘puzzling’), and whose sheer variety

admits all manner of unfathomed possibilities; it, too, can expand our skills if only our imagination rises to the occasion (p. 195) … The tool that simply restores is likely to be put mentally in the toolbox of fit-for-purpose-only, whereas the all-purpose tool allows us to explore deeper the act of making a repair. (p. 200)

Driven by the artisan’s curiosity to contemplate alternative usage, dynamic repair is accompanied by improvization that ‘most often occur(s) through small, surprising changes which turn out to have larger implications’ (Sennett, Citation2012, p. 214). In contrast to static repair, the reconfiguration involved in dynamic repair is ‘experimental in outlook and more informal in procedure’ (p. 220) and requires care and attention to detail in a way that suggests ‘an openness to different possibilities’ (p. 219). Sennett argues that all repair strategies depend on an initial judgement that what is broken can indeed be fixed and that one is not dealing with a ‘hermetic object’ that cannot be repaired and is beyond recovery (p. 219).

Sennett’s exploration of repair in the context of craftwork is not merely for its own sake; instead as a sociologist, his interest is driven by contemplation of new ways to relate the physical and the social.Footnote4 He explains

Restoration, whether of a pot or of a ritual, is a recovery in which authenticity is regained, the damage of use and history undone; the restorer becomes a servant of the past. Remediation is more present-oriented and more strategic. The repair work can improve the original object by replacing old parts with new; so too, social remediation can make an old purpose better if served by new programmes and policies. Reconfiguration is more experimental in outlook and more informal in procedure; fixing an old machine can lead, when people play around with it, to transforming the machine’s purpose as well as its functioning; so too, repairing broken social relations can become open-ended, especially if pursued informally. (Sennett, Citation2012, p. 219–220)

3. The Historically Restricted Nature of Audit Repair

Over the course of history, the audit and its regulatory arrangements have typically faced or been confronted with reform initiatives during significant post-crisis periods. Since the mid-1990s, such reforms have explicitly sought to strengthen the international financial architecture and restore the loss of confidence in the financial reporting supply chain (Humphrey et al., Citation2009). This section considers the nature of these audit reforms through Sennett’s lens of static and dynamic repair.

3.1. Historical Repair of the Regulatory Framework of Audit

With the traditional conception of audit typically being framed around evaluating evidence regarding assertions against established criteria and communicating the results to interested users (American Accounting Association, Citation1973), its principal value proposition in the financial reporting context has been associated with securing accountability between contracted parties via the enhanced reliability that audit should bring to an organization’s annual report. During the aftermath of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, a ‘standards–surveillance–compliance’ system (Wade, Citation2007, p. 115) was put in place to strengthen the institutional and market infrastructure to maintain financial stability in an increasingly globalized world. Audit reforms were directed towards achieving a more globally consistent audit practice through international standards. International Standards on Auditing (ISAs) were enrolled by the Financial Stability Forum (now Financial Stability Board) as one of the 12 key standards for achieving financial stability. This entailed strengthening global audit standard setting via a three-tier collaborative model, engaging the accountancy profession (IFAC), the international regulatory community (the Monitoring Group) and the oversight body (the Public Interest Oversight Board), with the intent of developing high quality global standards that better serve the public interest (Humphrey et al., Citation2009). The post-Enron reforms that followed sought further to strengthen the regulatory infrastructure around the audit by enhancing clarity in auditing standards (IAASB, Citation2008)Footnote5 and stipulating more stringent rules governing independence, competence, oversight and enforcement (EC, Citation2003; IFAC, Citation2003). Despite the developing relationship between auditing and global financial regulatory structures, the conceptual nature of audit has remained very much the same as expressed by Jane Diplock, the then Chair of the New Zealand Securities Commission as ‘the first external independent line of enforcement of financial reporting standards and financial reporting law. Audit is one of the vital filters that ensure that users of financial statements can have confidence in them’ (Diplock, Citation2006).

This conception of the audit came to be further reinforced in the wake of the 2007 global financial crisis, with the new G20 grouping envisioning a stronger version of the ‘standards–surveillance–compliance’ system (Humphrey et al., Citation2009). Within this context, the European Commission launched a broad consultation on the role and relevance of the audit and the wider environment within which audits are conducted (EC, Citation2010). The discussion and debates were however ‘surprisingly closed’ leading to the reform being structural than fundamental in nature (Power, Citation2011, p. 324). Premised on the rationale that auditors are entrusted to fulfill a societal role in offering an opinion on the truth and fairness of the financial statements of audited entities, reforms focused on enhancing audit quality to re-establish investor confidence in financial information (EC, Citation2010). Focal points of the reform included efforts to reduce concentration in the audit market and enact legislation to strengthen auditor independence, support International Standards on Auditing (ISAs), and enhance the informational value of the audit report to investors (EU, Citation2014a, Citation2014b). Although such regulatory proposals have rarely been supported by strong empirical evidence in delivering better quality auditing (Hottegindre et al., Citation2016; Humphrey et al., Citation2011; Quick, Citation2012), their prevalence suggests that they have been more acceptable to powerful vested interests than a fundamental questioning of the value and purpose of audit.

This history of repairs to the international financial architecture can be viewed as dynamic, involving reconfigurations of the regulatory paradigm and the contested interplay between the international regulators, the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) and the large accounting firms (Loft et al., Citation2006; Sonnerfeldt & Loft, Citation2018). However, within this context repairs to the audit itself have been static, owing to the historically restricted nature of reforms that have fortified the audit-consulting and trust-skepticism dichotomies, underpinned by a persistent belief in, and commitment to, the existing audit model. This is reflected in the latest Monitoring Group recommendations on the structure, governance and funding of the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) and International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA) to enhance the independence of the standard-setting process and its responsiveness to the public interest (Monitoring Group, Citation2020). Likewise, the recent development of extended audit reports addressing key audit matters (Gutierrez et al., Citation2018; ICAEW, Citation2017; Minutti-Meza, Citation2020) are centered on explaining the undertaking and findings of a conceptually static audit function, albeit in a more customized and extensive narrative. The increasing emphasis on convergence, external oversight and independent audit inspection may well have pushed the balance further towards a growing emphasis on compliance with an increasingly detailed and complex body of formal auditing standards but, in the process, has served to further embed the ruling conception of audit (Dowling et al., Citation2018). The conceptual foundations of audit and the substantive impact that alternative forms of audit could potentially deliver have never really been questioned. These repairs of audit are, in Sennett’s terms, essentially static repairs.

3.2. Thinking Beyond the Traditional Audit

Beyond the regulatory framework, there have been on-going discussions acknowledging the need to rethink fundamentally the audit and reconsider its role and relevance in society. Whilst the statutory financial audit is known to be heavily regulated, Hayward (Citation2003) contended that ‘many of the supposed barriers to change in auditing are actually matters of custom and practice, rather than unalterable facts’ (p. 11) and that mythologies about auditing can be broken.

While accepting auditing as a second-order function designed to opine on corporate reporting, proposals have been made to remediate the audit by broadening the scope of the audit to enhance its social relevance. Hayward (Citation2003) for example, proposed maintaining the current audit but altering its rationale to help management to ‘get things right.’ In tandem with this, he proposed an additional new class of public interest auditor called an ‘evaluator’ who is ‘genuinely – totally – independent of management and external to the company’s processes’ (p. 4). A critical element underpinning his views is that an auditor, as typically conceived, is required to ride two horses – one of providing a public interest audit and the other of helping management (Hayward, Citation2003). A possible way forward, he argued, is not to shoot one horse (i.e., prevent auditors from providing non-audit services) but to create a second rider (the evaluator) who can provide the public interest audit in a truly independent fashion. In another proposal, Hatherly (Citation2013) suggested an alternative to the current ‘one-level of assurance’ audit model by envisioning an audit report to consist of parts covering different elements, allowing the audit opinion to vary to reflect the differing level of risk to the element being audited in order to strengthen the information value chain for not only investors but also other stakeholders. In a similar vein, Jeppesen (Citation2019) suggested enhancing the social relevance of audits by including the detection of commercial and political corruption at micro level of organizations within the scope of audit. He proposed that corruption to be included as a main category of fraud in ISA 240, which would then be considered in the auditors’ initial risk assessment (Jeppesen, Citation2019).

A step closer to contemplating dynamic repair is to rethink the socially constructed boundaries between audit and assurance, and of consulting and independence (e.g., Jeppesen, Citation1998). A particularly significant initiative was the work of the AICPA Special Committee on Assurance Services (Elliott Committee), established to develop new markets for assurance services in the mid-1990s (AICPA, Citation1997; Elliott, Citation1994, Citation1998). The Committee considered extending the financial audit along three dimensions: namely, subject matter, service and form employed (Elliott, Citation1994; Elliott & Pallais, Citation1997). The Elliott Committee framed the extended range of services not as ‘audit services’ but as ‘assurance services’ that ‘improve the quality of information, or its context, for decision makers’ (AICPA, Citation1997). This framing potentially freed the audit from its link with financial reporting which then afforded ‘audit-like’ services the flexibility to deviate from the provisions of attestation (including auditing) standards (AICPA, Citation1997; Nugent, Citation1999). While some of these professionalization projects (e.g., WebTrust) were not known for their success (Boulianne & Cho, Citation2009; Gendron & Barrett, Citation2004; Shafer & Gendron, Citation2005), one outcome of these developments was that the framing of assurance created a possible space within which innovation could take place and potentially challenge the status quo of the financial audit. For example, stressing the goal of information improvement rather than the issuance of a report on the credibility of the reported information puts focus on the assurance service or process itself (rather than just an assurance statement or certificate). It also reduces the need to fit a range of services into a predetermined presentation or reporting format which arguably could serve to stifle the growth of such services and make it less responsive to the needs of decision makers (AICPA, Citation1997; Nugent, Citation1999).

Disassociation of the audit from the financial reporting context has also created a space to think differently about audits. Power’s (Citation1994, Citation1997) work on the Audit Society drew attention to how spread of the idea of audit beyond financial auditing has vastly increased the social significance of audit. A special issue in Accounting, Organizations and Society invited readers to open up audit spaces by exploring how audit-like services manifest in other substantive domains (see Chapman & Peecher, Citation2011; Francis, Citation2011; Power, Citation2011). An increasing number of academic studies have explored the broader social manifestation of ‘audit-like,’ assurance services (see, for example, Andon et al., Citation2015; Andon & Free, Citation2012; Jamal & Sunder, Citation2011; Jeacle, Citation2017; Jeacle & Carter, Citation2011; O’Dwyer et al., Citation2011; Power, Citation1997). Operating in less regulated practice arenas and quite different contexts to the statutory financial audit, the observed diversity of assurance practices has been reflected in the differing roles and identities of assurance providers, varying stakeholder relationships and levels of assurance.Footnote6 Attention has also been given to understand the ‘transmogrification’ of traditional audit logics in new domains of ‘assurance,’ especially the shifting level of emphasis placed on the importance of an assuror’s degree of independence from the subject matter being assured, and the capacity for a greater level of flexibility and improvization compared to the more conservative cultural conditions traditionally associated with the audit and audit firms (see Jeacle, Citation2017).

It is perhaps surprising that the exploration of the broad nature of assurance services has not provoked greater reflection on the possibilities for dynamic repair of the statutory financial audit. Instead, the audit has largely remained a compliance-orientated function, dependent on the value of the information being assured for its significance.Footnote7 Drawing on Sennett’s work, we argue that dynamic repair requires a deeper form of conceptual framing that allows the audit to break free from its past constraints. The next section considers keys constraints that limit the scope of dynamic repair and points to ways in which the conceptual basis of the audit can be reconfigured.

4. Towards a Dynamic Repair

As explained in Section 2 above, reconfiguring relationships with the social is at the heart of repair work (Sennett, Citation2012, p. 219). The implication of Sennett’s arguments is that dynamic repair can encompass and enable shifts in the social functionality of a particular craft or activity – a sentiment which echoes those of Flint (Citation1971) when contemplating the adequacy of audit more than forty years previously:

It is true that audit practice has changed and is changing; new methods and techniques are being developed and used; auditing standards have been raised. Yet, how can it be determined if they are adequate until it is certain that the objective they are designed to achieve is right. Against what criteria can the adequacy of practice be judged in the absence of a basic philosophy. The theoretical basis of the audit function has received little attention in the past and yet it is an evolving function reacting to social change and need. (p. 287)

what is more valuable – an audit that confirms that your business has made a massive loss but has stated the loss accurately in its accounts or an audit that informs and helps to sustain the business, providing meaningful, long-term employment to staff who would otherwise have been made redundant? Is an auditor not able to do or say more than that the accounts of a ‘pay-day’ money lending company charging interest rates of up to 1460% APR are true and fair?

4.1. Recognizing the Constraints of ‘An Audit is an Audit’

The phrase ‘an audit is an audit’ has been used in a prominent colloquial fashion across different contexts for almost a century, with its usage typically reflecting the supposedly mundane nature of audit (Andersen, Citation1926) or its perceived limited value: ‘In the eyes of clients, an audit is an audit, and often little or no added value is perceived in choosing one firm over another’ (Palmer, Citation1989, p. 85). The claims that ‘an audit is an audit’ have been used to connect across different forms of audit, suggesting similarities, for example, across sustainability, performance and medical audits, and programs or activities under review.Footnote8 The phrase has also been used by the accounting firms to cut down some of the hyperbole inherent in recruitment marketing campaigns:

I just begin to get irritated when staff from the other 3 point fingers at KPMG for being the bad guy. They seem to forget that an audit is an audit and unless PwC has discovered a new shmebit [sic]. … that the rest of the Big 4 don’t know about then I am pretty sure they audit the balance sheet and income statement the same way the rest of us do. (Newquist, Citation2011)

An audit is an audit … But we recognize the need to be able to provide that service as effectively as possible. Because we’re in the trenches, we can recommend things that may help them do their finances better. (Egneckow, Citation2014)

It is often said that an audit is an audit is an audit. But not at Ashurst Accountancy – we see this service as an essential part of your business risk strategy. (Ashurst, Citationn.d.)

However, beyond such generic uses of the phrase lie some quite fundamental issues and critical shifts regarding the conceptual underpinnings of audit and the key driving forces behind what we have come to accept as ‘standard’ audit practice. The term ‘an audit is an audit’ has been deliberately and directly utilized to promote what has become one of the core dimensions of audit quality, namely the consistency of audits. As the ICAEW (Citation2010) summarized in its monograph on audit quality:

Consistency is an important element of quality. The mantra of ‘an audit is an audit’ is widely used to emphasize the importance of consistency in ensuring that audits of small and medium enterprises are not seen to be of inferior quality simply on the basis of size. Likewise, it may also be used to emphasize that the quality of an audit should not be judged on the basis of the country where it is performed. Significant efforts have gone into developing internationally recognized standards that contribute to audit quality and explain what auditors need to do to achieve it. Standards set out expectations covering many aspects of the FRC’s drivers of audit quality: culture, skills and personal qualities; audit process; and audit reporting. (p. 17)

Underlying the 2008 policy position statement are two important assumptions. Firstly, associating ‘audit’ with any other level of assurance is likely to be confusing and costly to the users of financial statements. Therefore, the word ‘audit’ should convey only one level of assurance (specified as reasonable level of assurance). A second important assumption is that ‘high quality auditing standards should be, and in fact are, capable of being applied to the audits of the financial statements of entities of all sizes’ (IFAC, Citation2008, p. 2). Taken together, these assumptions imply that single set of standards should exist for auditing purposes and this enables a consistent level of assurance to be associated with the word audit.

Recognizing that each audit is different, professional judgement is called for to determine the required procedures to be performed, or in exceptional circumstances to depart from a relevant requirement, to arrive at a level of assurance sufficient to enable the auditor to express an audit opinion. Based on this reasoning, it has been stipulated in both versions of the policy statement that ‘While the audit approach itself may differ, the auditing standards on which it is based (i.e., the ISAsFootnote11) and the level of assurance the auditor is required to obtain, should not. It is in this sense that “an audit is an audit”’ (IFAC, Citation2008, p. 2, Citation2012a, p. 2).

The vivid consequence of such policy stipulations is that the essential pre-requisite for delivering on the claim that ‘an audit is an audit’ is that audits have to be done in compliance with a quality set of auditing standards. The 2008 IFAC policy position statement does not directly state that ISAs are such standards but a very important amendment in the 2012 revised policy position statement made this very clear:

IFAC believes that high-quality auditing standards (i.e. ISAs) are capable of being applied to audits of the financial statements of entities of all sizes. This enables a consistent level of assurance to be associated with the word ‘audit’ and allows users to make decisions based on a common understanding about the reliability of audited financial statements. (IFAC, Citation2012a, p. 5)

This reinforcement of the ruling conception of audit has exercised a constraining influence on audit methodological innovation (Curtis et al., Citation2016). As a case in point, the business risk audit (BRA), introduced by the Big 4 audit firms around the mid- to late-1990s (Curtis & Turley, Citation2007) represented a direct attempt to re-engineer the conceptual nature of audit. In defining business risk as the risk that an entity would not meet its objectives (Lemon et al., Citation2000), there was a clear opportunity for auditors to expand their focus from the financial statements to a broader assessment of the audited entity’s performance and the strategies being applied to meet its stated business objectives. However, the audit firms who led such innovations, wary of extending their exposure to litigation, insisted that this was just a new way of forming an opinion on the company’s financial statements (Curtis & Turley, Citation2007). Despite the theoretical potential to develop a broader and more valuable form of audit (Bell et al., Citation1997; Peecher et al., Citation2007), in practice the potential for conceptual development was confronted by regulators’ suspicions that this so-called new methodology was a thinly disguised attempt on the part of the big firms to generate more management consulting revenues and did not conform to pre-existing conceptions of an audit (Jeppesen, Citation1998; Levitt, Citation1998). A clear message from the case of the BRA is that the capacity to pursue and deliver conceptual innovation in audit is fundamentally restricted by what the regulators were willing to sanction (Curtis et al., Citation2016).

Constraints to making audits more value relevant can also be observed in the various attempts by the profession to address the issue and challenges of SME audits. Discussions on new forms of audit have been subjugated by the strength of support for ‘an audit is an audit’ (IAASB, Citation2019, p. 6). To illustrate, in June 2015, the Nordic Federation of Accountants published for consultation the Nordic Standard for Audits of Small Entities (SASE) which was developed for the purpose of establishing a high quality, stand-alone, principles-based auditing standard tailored to audits of small entities (NRF, Citation2015). The IAASB responded to the consultation reiterating that ‘any such efforts cannot be undertaken at the expense of audit quality, which we believe is a strong possibility if the proposed SASE is put into practice’ (IAASB, Citation2015, p. 1). Although a separate standard for the audit of less complex entities is currently being contemplated to improve its fitness-for-purpose, the IAASB has reiterated that the separate standard would be based on similar principles of ISAs (IAASB, Citation2020) thus constraining any attempt at conceptual development.

We argue that the predominance of the notion of ‘an audit is an audit’ limits significantly the scope of actors to engage in any dynamic repair of audit. If standard setters and their key constituents’ have fixed views of the concept of audit, then change is restricted to adjustments in the way of doing a particular, standardized form of audit. This leads to a policy arena that puts the reforming emphasis on the ‘what’ and ‘how’ to audit rather than the ‘why’ of audit. It dispirits initiatives intent on reformatting the purpose, or challenging the conceptual underpinnings, of audit and constrains the possibility of accepting fundamentally different forms of audit. If, as we argue, a dynamic repair is to have the capacity to encompass a broadening of the objective of audit, to contemplate audit as a first- rather than a second-order function or to reconfigure the contribution of audit to society, then the conceptual rigidity of ‘an audit is an audit’ must first be dismantled.

4.2. Rethinking the Relationship between Audit and Assurance

In contemplating dynamic repair of audit and the related scope for its conceptual development, an important focal point is the regulatory boundary constructed around audit practice. Considering the capacity to reconfigure this boundary, especially in terms of the defined relationship between audit and assurance, can provoke a fundamental reframing of audit’s value proposition.

In the international regulatory arena, the audit is envisaged as an instrumental pillar serving to strengthen the effectiveness of financial reporting (Financial Stability Board, Citationn.d.). In this context, it is framed by the IAASB as an activity of ‘significant public interest’ and a ‘critical part of regulatory and supervisory infrastructure,’ the value proposition of audit is focused centrally on assuring the quality and credibility of financial information, and bolstering public confidence in financial reporting and disclosure (Schilder, Citation2010). Firmly associated with a decision usefulness perspective, the audit is represented primarily as serving the needs of capital markets, with a strong emphasis on convergence towards one set of global, principles-based auditing standards.

Intriguingly, a further substantial restriction on the scope for conceptual development in audit rests in the IAASB’s framing of the audit-assurance relationship. Initial consideration of the need to develop formal standards for assurance engagements was undertaken by the International Auditing Practices Committee (IAPC) (the predecessor body to the IAASB) when seeking to attend to the diversity of practices by accounting firms who, in the 1990s, were increasingly engaged in providing ‘audit-like’ services on a broad range of subject matters. Standardization was seen here as a way of not only establishing consistent terminology but also offering measured guidance to the profession on the performance of these services (IAPC, Citation1997). The initial efforts of the Assurance Subcommittee of the IAPC focused on developing a structure to provide top level guidance which would define and describe the core elements of assurance and identify the particular forms of assurance engagements by which secondary guidance could be subsequently discussed (IAPC, Citation1996). The assurance framework was drafted drawing on the elements and general principles of financial auditing at a higher, more generic level, which could then be re-embedded to apply to assurance services across an array of different subject matter (IAPC, Citation1997). The IAPC chose to emphasize the attributes of objectivity, independence and competence of professional accountants, with the stated intention of building on an asserted existing public acceptance that independent verification of information and system operations enhances the credibility of the information produced by such systems (IAPC, Citation1997; Sonnerfeldt, Citation2011).

With the ‘audit’ being increasingly represented as a vital part of a developing international financial architecture, it became imperative for the IAASB to set the financial audit apart from these other forms of assurance services; such that audit was represented as a product conveying a higher level of assurance. The relationship between audit and assurance was formalized during the June 2002 IAASB Board meeting where it was decided that audit and review of historical financial statements were ‘types of assurance engagement,Footnote12 but had special characteristics such that separate series of standards were needed to deal with them and with other assurance engagements’ (IAASB, Citation2002, p. 4). The International Framework of Assurance Engagements (hereafter, ‘the Framework’) delineated two fundamental categories of assurance engagements: audit and review engagements on historical financial information (where ISAs and ISREs applied respectively), and engagements other than audits and reviews of historical financial information (where ISAEs applied).

Defining an assurance engagement as one in which ‘a practitioner expresses a conclusion designed to enhance the degree of confidence of the intended users other than the responsible party about the outcome of the evaluation or measurement of a subject matter against criteria’ (IAASB, Citation2003, p. 6) clearly limited the interventionist capacity of an assurance engagement performed according to IAASB standards – because assurance providers would not directly improve the matter subject to assurance. Any enhancement would be indirect, resting on the use made of the assured information and the faith placed in the assurance provider’s assessment of its credibility. However, such an approach also had major implications for the development of audit’s value proposition. By defining audit as one particular form of ‘assurance’ service and then further limiting the notion of an ‘assurance’ engagement to a form of independent verification, fundamentally restricts the conceptual development capacity of the audit. Even an extension in the scope of the audit pertaining to information other than historical financial information, cannot be classified as an audit development but has to be classified as the provision of an ‘assurance service.’ Thus, in essence, any attempt to shift audit to a form of primary rather than secondary intervention (where the value of the audit depends directly on the actions of the auditor rather than the value of the information set whose ‘credibility and veracity’ is in the process of being ‘audited’ and/or ‘assured’) now faces a double barrier. Given the way ‘assurance’ has been defined, the pursuit of any primary investigative function is not capable of being classified as an assurance service, let alone an audit.

To counter such constraints on the conceptual development of audit, and to promote the capacity for dynamic repair, one strategy would be to reverse the presumed relationship between audit and assurance.Footnote13 Treating assurance as a subset of audit (rather than the other way round) is a conceptual leap that can immediately transform thinking about audit by removing the ‘double trap’ within the current set of IAASB’s pronouncements. This would create space for ‘audit’ to move from assertions about what is not audit, to assessments of what auditing could become, with such contemplations grounded less in what auditing has typically been and more in how audit and auditors can best serve society. The way audit has been positioned in such architecture with a central commitment to serving the ‘public interest’ invites the possibility of audit being conceptualized in broader ways. As an essentially social phenomenon (Flint, Citation1988; Mautz & Sharaf, Citation1961), audit’s conceptualization is not fixed or set in stone. It does not have to remain as one particular form of information assurance at the end of the financial reporting supply chain. It could, for example, take on a primary concern with the ‘repairing’ of audited companies.Footnote14 The philosophy of audit regulation could also switch from one that pursues convergence and compliance to one that acknowledges the multi-purpose and idiosyncratic nature of auditing (Knechel, Citation2009). But this requires a rethinking or reconceptualization of the capacity of audit standard setting processes to contribute to innovation in audit practice. This is considered in the next sub-section.

4.3. Rethinking the Innovative Capacity of Auditing Standards

The way in which international standards on auditing (ISAs) are set, organized, implemented and enforced to facilitate greater comparability and consistency in audit quality, brings with it the potential for unintended consequences in encouraging a compliance oriented, form over substance mentality to audit practice (Dowling & Leech, Citation2014). The typical response to any such tendency is to look inwardly; to review the nature, extent and content of standards or to add another layer of regulation to the audit regulatory infrastructure, which in the process, further discourages dynamic forms of repair.

Standards have come to be omnipresent in a globalized world, addressing all walks of life from food production to emissions trading and even defining what constitutes a planet (Busch, Citation2011; Timmermans & Epstein, Citation2010). Each standard has its own history and differs in scope, level of precision, inclusiveness and ways of coping with regime design (Baxter, Citation1981; Sunder, Citation2016).But comparing the international audit standard setting with different standard setting regimes provides an important opportunity to make intuitive leaps (Sennett, Citation2008; Timmermans & Epstein, Citation2010), to develop a sense of ‘wonder’ (Sennett, Citation2008, p. 211) as to what might be able to be achieved from learning how standard setting functions in other domains – especially those characterized by rapid innovation. A fascinating illustrative example here comes from a study documenting the work of the Standards Education Committee (SEC) of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) (Schneiderman, Citation2015):

(Standards) are the fundamental building blocks for the development of products that help drive the process of compatibility and interoperability; standards make it easier to understand and compare products. As standards are adopted and applied to new markets, they also fuel international trade with an emphasis on promoting technical cooperation and harmonization. (p. 2, emphasis added)

International standards have been driving innovation, contributing to the growth of markets. (p. 4, emphasis added)

(T)oday, more than ever, the world needs international standards to enable the creation of products and services that will be implemented and used by customers globally. (p. 4, emphasis added)

Bluetooth has been one of the fastest growing innovations on the wireless market sector, with literary billions of Bluetooth products already in use. It was also one of the quickest in the sector to gain standards status and name recognition. The technology (and standard) have gone through several revisions and updates, virtually all of which have reduced its cost and added enhanced feature capabilities not dreamed of when engineers at Ericsson first started thinking about a wireless alternative to RS-232 cables. That was in 1994. Today, the accepted Bluetooth standard, IEEE 802.15.1, defines a uniform structure with global acceptance to ensure interoperability of any Bluetooth-enabled device. (p. 56, emphasis added)

Talk of standards creating the space for innovation and the development of new products and services sounds very different to the international audit arena where mantras such as ‘an audit is an audit’ discourage new services or conceptualizations of audit; in essence holding audit out as a unitary product or service. While accepting that standards in electronic engineering and auditing may well reflect and be responding to very different sets of circumstances (Timmermans & Epstein, Citation2010), the comparison raises important questions about what the notion of ‘compatibility’ and ‘interoperability’ could mean in relation to the content and depth of auditing standards.

It is easy to see the dysfunctionality of having mobile phone chargers that only work on individual models and the attractiveness of wireless charging devices that work on all types of phones – and the evident value of developing (even detailed and specific) technical standards so long as they facilitate such a level of functionality. In contrast, in terms of auditing, it is important to recognize the dysfunctionality of promoting a particular (standardized) form of auditing that is not compatible with ruling modes of corporate governance and social responsibility norms. For example, the current ruling conception of audit may be capable of being delivered in accordance with pre-specified formal procedures, but with potentially very different end results and social impact in different cultural contexts. Such results could include the potential privileging of formal over substantive compliance and a reduction in the capacity for professional judgement, that prior to external standardization, had been suitably aligned with differing contextual circumstances and conditions (for more discussion, see Sunder, Citation2016). If the notion that ‘an audit is an audit’ is largely constructed around an Anglo-led, western institutional socio-cultural, political and business context (Botzem & Quack, Citation2009; Loft et al., Citation2006), the direction of practice development is not only largely one-dimensional – from Anglo-led nations to others – but runs significant risks of limiting the opportunity for substantive practice innovation (Komori, Citation2008, Citation2015, Citation2016).

Such questioning on the identity and compatibility of audit leads directly into consideration of how process-, as compared to output-, oriented do international auditing standards need to be? If the commitment to enhancing audit quality is framed as one of empowering talented professionals to work better and contribute more, it becomes very important to look beyond a compliance orientated functionality to the advancement of outcomes and product development. In addressing this issue, the experience with international standard setting functions in electrical engineering is again pertinent – specifically through the way it treats the sharing of intellectual property, which Schneiderman (Citation2015) stresses has proved to be ‘(o)ne of the most critical and contentious issues in developing technical standards’ (p. 235).

The principal problem here is that companies holding essential patents will push to raise their licensing fees once a particular patented electronic technology has been incorporated into an international electronic engineering standard (p. 236). To counter such tendencies, the resulting standard setting response has been one of requiring patent holders ‘to license them to standards implementers under terms commonly referred to as fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND)’ (p. 236, emphasis added). Bluetooth was such a success in terms of the scale of product innovation ‘because companies agreed to out-license the basic patents at no costs for the development of Bluetooth enabled devices. Only non-essential patents for particular solutions would be charged, at non-discriminatory and fair conditions’ (p. 68). The standardization of Bluetooth technology and associated ease of access provided the critical interoperability and the resulting scale of product innovation.

What if we ask the same question to international standard setting in auditing? Are ISAs and their associated standard setting process being classified unambiguously as ‘FRAND’ and, as such enabling audit product development? The answer is not in the affirmative. To be a member of the IAASB specifically requires a declaration to support the development of ISAs. The comparison with the electronic sector illuminates the ‘interested’ content of ISAs. They are not neutral vehicles. Not only do they belong to particular moments in time and particular ways of thinking, but they also belong to someone as the case of IFAC’s policy on translations (of its standards) makes clear: ISAs and other related international accounting ethics and education standards are IFAC’s intellectual property (IP):

IFAC strives to make these materials accessible—particularly to promote the widespread adoption and implementation of high-quality international standards for the accountancy profession, in the public interest. At the same time, we aim to strike a balance with good stewardship of our IP. This means controlling access in order to monitor and ensure accuracy and quality in the translations and reproductions of our copyrighted material. (IFAC, Citation2018a) (emphasis added)

In contemplating whether international auditing standards are ‘FRAND,’ it does suggest that we need to be asking more pertinently whether the current regime persists because it suits particular interested parties and what capacity the current regime has for encouraging ‘product’ innovation and promoting new forms of audit? If serving the public interest is demanding of such conceptual advancement or product development, in the spirit, for example, of kaizen and continuous improvement (Fujimoto, Citation1999; Hiromoto, Citation1991), then the role of audit standard setting in facilitating such innovation and change needs to be addressed.

4.4. Rethinking the Public Interest Role of Audit

In placing the ‘public interest’ at the forefront of its responsibilities (Humphrey & Loft, Citation2008; IFAC, Citation2005), IFAC chose to define it as the ‘net benefits derived for, and procedural rigor employed on behalf of, all society in relation to any action, decision or policy’ (IFAC, Citation2012b). In a subsequent public policy report, IFAC provided a snapshot of the profession’s contribution to the achievement of the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (IFAC, Citation2016a), highlighting that ‘the SDGs should be seen as an opportunity for the profession to reflect on the nature of the changes ahead and capitalizing on the highest potential of the accountant within it’ (IFAC, Citation2016a, p. 30). As IFAC Chief Executive Officer Fayez Choudhury commented at the launch of the report:

It is important for our profession to be conscious of how we contribute, both directly and indirectly, to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. The skillset, experience, and influence professional accountants possess gives them enormous scope to shape solutions to sustainable development challenges. (IFAC, Citation2016b)

… The public and private sectors should embrace the opportunities presented by the Goals to act in the public interest as well as create value for business and investors. What we do as accountants benefits society and contributes to the resilience of the organizations we work in, both of which are key themes of this publication. (IFAC, Citation2016b, emphasis added)

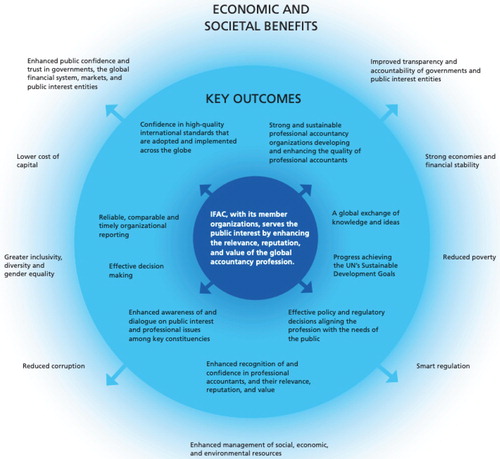

An illustration of the way IFAC has characterized the public significance attached to what the profession does is provided by diagrammatic form (Figure ). The core of the diagram represents the primary activities of IFAC and the outer circles identify the outcomes as well as social and economic impact that such activities can influence. There is a sense of connection passing from the inner circle to the outermost circle. For instance, setting high quality auditing standards, should enhance auditing practice, which can bolster the confidence of the public in the profession, and hopefully deliver enhanced transparency and lower costs of capital.

Figure 1. Economic and societal benefits. Source: IFAC Strategic Plan 2019–20 (IFAC, Citation2018b, p. 3). Copyright © 2018 by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). All rights reserved. Used with permission of IFAC.

One typical form of questioning with respect to such delineated chains of causation is whether audit and related technologies of governance can be so readily and uniformly assumed to apply across differing institutional socio-cultural contexts, especially in the developing world (see, Sinkovics et al., Citation2016).Footnote16 An alternative, and potentially more fundamental social critique, is emerging from a growing range of studies on notions of public interest and the common good (see Ballantine et al., Citation2020; Frémeaux et al., Citation2020; Killian & O’Regan, Citation2020), which have the direct intent of stimulating within the accounting profession a higher level of awareness of social needs and human development. Building on the spirit of such investigations and contemplating the opportunity for dynamic repair, it is worth contemplating the effect of reversing the arrows or chain of causation in IFAC’s diagrammatic representation of its strategy – where the starting point is to address ‘which social values should prevail and what sort of society we wish to create’ (Humphrey & Owen, Citation2000, p. 47). More specifically, how could the concept and function of audit be reshaped and reconfigured to deliver such ends? In other words, it calls for an innovative switch of presumptions of influence and purpose – from assuming that what auditors do is in the public interest to asking, ‘what can auditors do to serve the public interest?’ Instead of assuming that what is already being done by the accounting profession will result in particular desired social outcomes, a dynamic repair would engage the profession in addressing directly how best to impact on such social goals? It is from this perspective, rather than what auditing already does, where the reconfiguration of audit can begin.

In the UK, the Financial Reporting Council (FRC, Citation2006) long ago agreed with many audit researchers that audit is a social construction. Accordingly, we argue that it is possible to reconstruct audit around concepts, values and actions that make fundamentally better use of the hugely valuable resources being consumed in the delivery and regulation of the audit and associated education and training processes. We have become accustomed to accepting a justification of auditing that is functionally highly indirect. To paraphrase the standard international representation of purpose and effect: If IFRS and ISAs can be adopted and complied and enforced internationally, it will help to ensure that corporate financial reports are more transparent and this can lead to greater confidence being placed in such reports which may, in turn, lead to a reduction in corporate costs of capital, which, by implication, serves to increase the NPV of future revenue streams, which means increased corporate wealth and a greater capacity to pay dividends and possibly higher wages, in (another) turn allowing for greater levels of private and public investment, and, … , eventually holding out the possibility of enhanced levels of social inequality, reductions in poverty and increased social well-being.

We believe that audit can achieve more than this – but it requires a fundamental switch in mind set and a willingness to contemplate the functionality and impact of audit in more direct, ambitious and socially sensitive terms. Dynamic repair of audit requires shifting consideration from what audit has always been, or has not been, to contemplating new forms of audit which are better placed to deliver on desired social outcomes; audits that contribute directly to the development of better businesses with the capacity to deliver improved working conditions and reductions in levels of poverty and social inequality. Contemplating the contribution that the accounting profession can make to the UN’s SDGs does not have to be undertaken through the lens of a static conceptualization of the statutory financial audit.

5. Concluding Discussion

While some quite dramatic coverage in the media can create a sense of impending crisis in audit, at another level, especially when viewed from a historical perspective, there is a vivid sense of audit reform muddling through, of drifting from one crisis to another (Ford & Marriage, Citation2018; Langenbucher et al., Citation2020; Marriage, Citation2018). Despite successive indications and sequences of ‘failure,’ audit manages to retain its status as ‘a restorer of comfort,’ experiencing only cosmetic reforms to its operational purpose and intent (Power, Citation1994, p. 23). Our concerns with the continuing lack of emphasis on the reconceptualization of the core purpose of audit bears a striking similarity with Flint’s concerns in the 1970s when stressing the need for a more dynamic, critical and clearer understanding of social philosophy of audit:

What is needed in auditing is something dynamic, a critical, penetrating, enquiring attitude of mind, and a deep conviction of a vital social purpose. In some respects, this last aspect is the most important. The practice of auditing cannot evolve satisfactorily in a changing world if it is not conceived and exercised in the context of a social philosophy of audit and accountability. (Flint, Citation1971, p. 287)

In promoting the case for a dynamic repair of audit, we have highlighted four principal conceptual considerations. We started by emphasizing the restrictiveness of the notion of an ‘audit is an audit’ on conceptual innovation in audit and the way it has been utilized to reinforce the powers of international audit standard setters to determine what is or is not accepted as legitimate auditing and assurance practice. We then called for a conceptual switch in the relationship between audit and assurance, highlighting the potential impact on the value proposition of audit and the capacity for practice innovation if ‘assurance’ is viewed as a subset of ‘audit’ rather than the other way round. In a similar vein, we stressed the importance of reframing assumptions regarding the functionality of audit standard setting, calling for a regulatory space centered on facilitating innovation in auditing practice rather than compliance with one particular set of auditing practice standards. Finally, we advocated a major transformation in the way the profession contemplates its public interest responsibilities. Rather than presuming that what the audit currently does is, inherently, in the public interest, the starting point for the profession should be the contemplation of social needs and ambitions – and considering how the functional competencies of auditors can best contribute to the achievement of those ambitions. Pursuit of dynamic repair requires, in Sennett’s terms, a reconfiguration from within (Sennett, Citation2012, p. 255); in particular, for auditors to break out of their taken-for-granted views and to contemplate alternative, socially purposeful configurations of the statutory audit.

In seeking to stimulate a dynamic repair of the statutory financial audit, we have centered our analysis on core conceptual dimensions, as our analytical priority has been to build a stronger foundation and motivation for ‘thinking differently’ about the statutory financial audit and the ways to reform it. However, in closing the paper, we reflect on what an embracing of such analytical dimensions could produce in terms of reconfiguring the financial audit. Consider, for example, the case of the BRA. As explained in section 4.1, BRA held out the possibility of a fundamentally broader purposed audit with its definition of business risk as the risk that a business would not meet its objectives (Lemon et al., Citation2000). However, in choosing to retain the central audit focus on the financial statements of the audited business, the BRA lost its capacity to reform fundamentally the overall purpose and scope of audit. Working with the assumption that business risk ultimately impacts on financial statements risk, the principal challenge for auditors became one of determining how their broader based knowledge of business risk, strategy and operating environment would impact on detailed audit testing of individual elements in the financial statements. In the process, however, the opportunity to provide a more insightful and forward-looking form of assurance to stakeholders on the business’ capacity to meet its objectives, was fundamentally lost. Detailed historical analysis of the rise and fall of the BRA (see Curtis et al., Citation2016) highlights the core institutional factors that hindered, and ultimately defeated, an audit methodological innovation that potentially offered an opportunity for meaningful conceptual change of the audit (Peecher et al., Citation2007).

In a recent paper, Knechel et al. (Citation2020) sought to re-conceptualize financial audit by considering economic service perspectives, emphasizing that auditor independence is not a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution for maximizing audit quality. They argue for prioritizing the need, value and potential for audit to become more idiosyncratic and facilitate the exercising and expression of professional judgement. Such an outlook invites a major reconsideration of the case for the BRA and of the possibilities for a broader-based audit function centered on assessing the capability of a business to meet its objectives. Freed from the constraints of ‘an audit is an audit’ and associated compliance driven standards, a reconfigured BRA would be as idiosyncratic and diverse as the objectives and risks faced by different businesses. Further, in contemplating the consistency of such business objectives with desired social goals and values, there is an evident capacity for the BRA to deliver a more socially purposeful audit.

Such a frame of thinking connects directly with the philosophy underpinning the recently published report in the UK into the quality and effectiveness of auditing, hereafter ‘the Brydon report’ (Brydon, Citation2019).Footnote17 The central vision of the Brydon Report is one of getting the most from audit and it centers on the need for better auditing, better decision making and better, more resilient businesses (including audit firms) working visibly in the public interest. Most significantly, the Brydon report constructs its case for change by reformulating the basic purpose of audit and the nature of audit professionalism and developing its recommendations from there. Its reframed concept of audit states that the ‘purpose of audit is to help establish and maintain deserved confidence in a company, in its directors and in the information for which they have responsibility to report, including the financial statements’ (p. 22).

The notion of ‘deserved confidence’ is a particularly interesting one, because it is more of a moral or social concept than a statistical one. To build and maintain ‘deserved confidence’ demands some delineation and assessment by the company, its directors and auditors of the way the business functions and what it has achieved – with assessment of the extent to which confidence is ‘deserved’ being fundamentally dependent not just on the company’s business expectations but on those that society holds for it (given that society has granted the company a license to operate). In essence, establishing ‘deserved confidence’ not only requires businesses to review their strategic priorities and achievements but offers the opportunity for audit to shift beyond a predominant compliance orientation and financial statement assurance emphasis – and, in the process, recover the potential for conceptual innovation that the BRA once possessed.Footnote18 A business at risk of not meeting its strategic and societal expectations is not one likely to be deserving of the confidence of its stakeholders.

Another way of looking at this issue is to recall that the recent promotion of big data analytics (BDA) into auditing methodologies has been challenged for running the risk, as with previous technological developments in auditing, of amounting to the search for a technical solution to what are existential problems and dilemmas regarding the societal relevance of the statutory financial audit – and stressing that such initiatives must fundamentally contemplate their impact on the significance and role of auditing in the governance of business (see Salijeni et al., Citation2019, p. 115, emphasis added). Salijeni et al. (Citation2019) posed the question as to whether BDA will prove to be ‘a destructive innovation, at least in terms of the standing of auditing and auditors as a professional group’ (p. 115). It is similarly possible to ask whether the enabling potential of BDA will be fundamentally constrained, or hindered (as was the case with BRA), by the need to relate BDA to the continuing, restricted, information assurance task of reporting on the truth and fairness of the view given by the company’s financial statements?

But what if thinking differently about BDA is able to transform its meaning from one that involves the application of a new technology to a static conceptualization of the purpose of audit to one that dramatically transforms contribution that audit can make to business and social development. In fact, conceptually reconfiguring the audit in ways that enhance its learning and empowering role are latent in existing calls for auditors to do more, such as: providing fresh perspectives on key information published by management and greater transparency as to what has been learned during the course of the audit (e.g., see Forbes, Citation2014); ensuring greater stakeholder inclusivity in the corporate accountability chain (e.g., Edgley et al., Citation2010); and engaging the reporting organization and its various stakeholders with the intent of co-creating value (Knechel et al., Citation2020). Audit can be pushed further, particularly in the current climate. A profession committed to serving the public interest has no better opportunity than the present to put society first when thinking about the conceptual foundations of audit.

In making the case for dynamic repair, Sennett (Citation2012) specifically acknowledges that:

Opponents of this kind of repair/reform counter that, while it may feel good, destabilizing changes of this sort produce incoherent results. … . Incoherence in reconfiguration arises when the craftsman forgets there was a problem to solve in the first place

History readily indicates that we have had numerous past opportunities to reconfigure audit and have known the societal importance of doing so. Embracing the possibilities of dynamic repair can help to ensure that we do not waste the opportunity this time around. On the basis of the analytical dimensions covered in this paper, we certainly should not be overawed by the challenge.

More important, however, is the concept that today’s accounting problems do not involve only accounting. It follows that the ‘solutions’ to problems should not be derived only from accounting considerations. What appears to be sensible accounting theory or the logical reaction to criticism must be considered in the broader context of a rapidly changing social situation with dimensions and implications far beyond the control of accountants. If we are to preserve and improve our profession’s status, we must attempt to understand its position relative to the social revolution now in process, and to react appropriately. It will not be easy. (Seidler, Citation1973, p. 43, emphasis added)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the valuable comments on previous versions of this paper received from the two anonymous reviewers as well as Bertrand Malsch, Brendan O’Dwyer, Mary Canning, David Hatherly, Stuart Turley and Jim Peterson.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this paper when we use the term ‘audit’ we are referring to the statutory financial audit, unless otherwise specified.

2 ‘KPMG said it was co-operating and was “confident in the quality” of its work but surely, a detailed and professional audit should have turned up this widespread, recurrent and illegal activity? If it didn’t what the hell are auditors for anyway?’ (Jack, Citation2017).

3 In Japan, craftsmanship is called ‘monozukuri,’ which literally means the ‘production’ or the ‘making of things’ and connotes a collective dedication to working to sustainably high manufacturing outcomes. Although traditional craftspeople are decreasing in Japan due to the lack of successors and increasing levels of automation and robotisation, the spirit of philosophy of monozukuri continues to thrive, retaining economic and social significance (see Lufkin, Citation2020).

4 Sennett was the doctoral supervisor for Matthew Gill's (Citation2009) study of the way in which accountants construct truth and also himself analyzed craft-like tendencies in the back offices of Wall Street banks and investment houses (Sennett, Citation2012, p. 164; p. 170).

5 IAASB embarked on the clarity project to comprehensively review all International Standards on Auditing (ISAs) and International Standards on Quality Control (ISQCs) to improve their clarity and, thereby, their consistent application.

6 O’Dwyer et al. (Citation2011), for example, analyzed the entrepreneurial endeavor of one of the Big 4 firms to introduce a more user focus into sustainability assurance statements. Channuntapipat et al. (Citation2019) also showed that sustainability assurance takes various forms including compliance, social, formative and integrated assurance.

7 In rare cases, assurance providers have moved beyond statement verification roles to engage in more advisory roles (e.g., Chelimsky, Citation1985) but a more typical pattern has been for assurors to adopt quite basic judiciary roles, ‘enforcing’ compliance with rules (Andon & Free, Citation2014).

8 The Tennessee Department of Transportation’s internal audit manual states ‘An audit is an audit is an audit and they all work the same way; no matter where you are and what industry you are in. All audits go through the same basic steps’ (Tennessee Department of Transportation, Citation2016, p. 5).

9 The ICAEW report went on, however, to discuss the fragility of attempts to secure globally consistent audits, acknowledging that a ‘country’s values and norms may not be aligned with those that are implicit in international standards’ (p. 20) and that cultural biases in standards could lead to some countries having difficulties with their implementation, citing Mennicken’s (Citation2008) conclusion that ‘(a)lthough the adoption of ISAs is often motivated by attempts to imagine and create auditing as a uniform, internationally homogeneous whole, differences between the local and non-local, between the big international and the smaller indigenous audit firms, can never be completely erased’ (p. 20).

10 The words in parenthesis were deleted from the title of the 2012 revised version.

11 The words in parenthesis were added in the 2012a revised version.

12 The term ‘assurance engagement’ was adopted by the IAPC in 1999 to re-label assurance services previously referred to as ‘Reporting on the credibility of information’ (IAPC, Citation1999).

13 This suggestion was initially developed in a formal submission made to the Brydon review by Turley et al. (Citation2019).

14 The authors thank David Hatherly for this contribution.

15 The role and responsibilities of auditors continue to be specified in narrower terms than the ‘public’ may desire (Canning & O’Dwyer, Citation2006; Humphrey & Moizer, Citation1990; Humphrey et al., Citation2006; Jeppesen, Citation2019; Williams, Citation2014).

16 Sinkovics et al. (Citation2016) shows how the Rana Plaza building collapse provides a brutal exposure of the failings of corporate governance reporting mechanisms in Bangladesh.

17 The Brydon review was undertaken while the current paper was being revised and one of the authors was a member of its Advisory Board. This closing segment of the paper draws directly from a more detailed assessment by the author as to how best to read the Brydon Review report, (see Humphrey, Citation2020).