?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the content of corporate tweets related to earnings announcements and the incremental usefulness of YouTube and Instagram in disseminating earnings news. Textual analysis of tweets reveals that investors react more strongly to a firm’s communication on Twitter when it (i) includes financial information, (ii) mentions the CEO or the CFO, (iii) includes a visual element, and (iv) posts are written in a moderate tone. Tweets related to earnings announcements are particularly useful when retail ownership is high. Incrementally to Twitter, YouTube videos and Instagram posts do not have, on average, positive incremental effects on the price response to earnings news.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

Previous research is silent on the content of tweets that contain earnings news, thus, what firms communicate on social media and how investors react to the content of tweets remain unexplored.Footnote1 Furthermore, prior studies have focused almost exclusively on how investors react to earnings news posted on Twitter. Consequently, the incremental usefulness of other social media platforms than Twitter in disseminating earnings news is unclear. The aim of this study is twofold. First, we investigate the content of corporate tweets about earnings results, such as the type of financial information they include (e.g., about the firm’s revenue and growth), the use of visual elements (such as pictures and videos), and the tone of the message, before examining how such content affects investors’ interpretation of earnings news. Second, we assess the usefulness of YouTube and Instagram in conveying earnings information. We focus on YouTube and Instagram as these two platforms emphasize video and picture communication more than Twitter does (Twitter tends to focus on short text). This means that YouTube and Instagram are distinct from Twitter in terms of their presentational medium, which, in turn, could mean their user bases are distinct too and as a result, the two platforms can play an incremental role to Twitter in earnings news dissemination.Footnote2

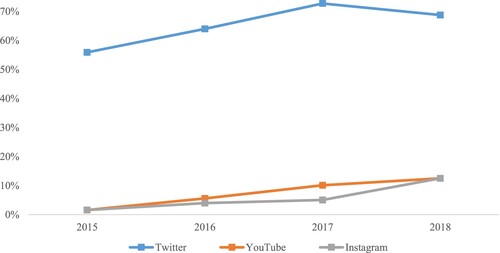

We examine the use of Twitter, YouTube and Instagram in earnings communication by the largest UK firms (as identified by the FTSE 100 index) because these firms have the resources necessary to engage in multi-platform communication.Footnote3 We document that 64% of the firms in our sample used Twitter to communicate with investors about semi-annual and annual earnings announcements over the period January 2015–April 2018, with the usage rate increasing from 56% in 2015 to 69% in 2018. The uptake of the other two social media platforms is initially low, but increases over time: the proportion of firms posting on YouTube is around 2% in 2015 and increases to 13% in 2018, a 6.5-fold increase, with a similar pattern for Instagram.

Focusing on the content of all tweets issued at earnings announcements that included earnings results – what we define as the earnings-day Twitter communication – we document that a significant proportion of Twitter communications refer to financial information on revenue, growth, expenses, operating performance and on dividend and repurchases. For example, around 43.1% of communications on Twitter mention the firm’s revenue and growth, and 20.7% mention payouts (either dividends or repurchases). Moreover, around 36.2% of Twitter communication mentions the CEO/CFO and often include short statements from the CEO highlighting the firm’s performance. 82.8% of Twitter communications include positive tone words, while approximately 15% of communications include a graphical element, such as a cashtag, picture or video. Thus, there is a significant heterogeneity in the content of Twitter communication released in relation to earnings announcements.

To understand how investors react to earnings news conditional on the content of the tweets, we relate them to price reactions. To capture the content of earnings news, we follow previous studies and calculate the earnings surprise – the standardized difference between actual earnings and the analyst consensus forecast (see Aboody & Kasznik, Citation2000; Healy & Palepu, Citation1995; McVay, Citation2006 Skinner, Citation1994;). We then interact the earnings surprise with variables capturing the content of tweets.

We find that investors react more strongly to earnings news when Twitter communication include references to financial information (on revenue, growth, expenses, operating performance and on dividend and repurchases). To illustrate, the price reaction to earnings surprises increases by 22% when Twitter communication mentions revenue, and by 17% when tweets mention operating performance. This finding is consistent with investors attaching more weight to earnings news when managers identify the drivers of financial performance, which helps investors assess the persistence of earnings surprises (Ertimur et al., Citation2003). Twitter communication that mentions the CEO or the CFO increase price reaction to earnings surprises by 17%. This result suggests that firms can enhance the credibility of social media communication by conditioning on the top-management’s reputation (Kelton & Pennington, Citation2020). Twitter communication with a more moderate tone associates with stronger price reactions, which suggests that companies can increase the credibility of social media communication by avoiding excessively optimistic wording (Davis et al., Citation2015). Finally, tweets that include visual elements, such as cashtags, pictures or videos, associate with higher earnings response coefficients. These results suggest that visual elements can help attract investor attention to tweets, thus facilitating the dissemination of earnings news.Footnote4

To sharpen the analysis of why investors react to earnings news disseminated on Twitter, we also examine (i) how different audiences react to Twitter communication and (ii) how characteristics of the Twitter communication, such as the frequency of tweeting, affect the usefulness of this social media platform in disseminating earnings results. We find that earnings news tweets are particularly useful when the stock has significant retail ownership, consistent with social media reducing information acquisition costs for retail investors (Barber & Odean, Citation2008; Nofsinger, Citation2001). We do not find that a higher frequency of tweets, higher reader engagement with tweets through likes, reposts and comments, or higher user following correlate with stronger price reactions to earnings surprises.

Next, we turn to the role of YouTube and Instagram in earnings news communication. We find that firms are more likely to use YouTube and Instagram when they also communicate on Twitter. Instagram posts are also more likely to be utilized if a firm is using YouTube. These results suggest that firms use YouTube and Instagram to complement their Twitter output, presumably as a means to increase news reach beyond Twitter.

To capture the incremental usefulness of YouTube and Instagram in earnings communication beyond that of Twitter, we focus on the earnings response coefficients. We find no evidence that, on average, YouTube and Instagram posts increase price reactions to earnings news. In fact, YouTube posts associate on average with incrementally lower price reactions. This evidence is consistent with (i) a relatively low usage of YouTube and Instagram in relation to earnings announcements, (ii) that Twitter also allows firms to post pictures and video, which reduces the competitive advantage of YouTube and Instagram, and (iii) that firms tend to use the same media content across platforms (see , which presents the infographic for International Hotel Group on Twitter and Instagram). Subsample analysis documents that YouTube videos associate with incrementally more positive price reactions to earnings news when (i) retail ownership is high and (ii) firms engage more on YouTube by posting more videos – such posts moderate the average negative effect from earnings news communication on YouTube. Instagram posts, meanwhile, have no positive incremental effect on how investors interpret earnings news even when conditioning on retail ownership, firm engagement on Instagram, and user engagement with the post.

Figure 1. An example of social media posts on Twitter and Instagram related to earnings announcements for International Hotel Group.

We conclude by presenting three complementary results. First, we show that our conclusion that YouTube and Instagram posts do not associate with incrementally higher price reactions to earnings news extends to earnings-related posts on Facebook. Second, our evidence suggests that price reactions to tweets and YouTube videos that present earnings results are incrementally stronger for firms with higher retail ownership. This evidence suggests that communication on these two platforms meets the retail investors’ demand for the channel through which to disseminate financial results. Following up on this result, we also examine whether retail ownership increases in response to firms’ communication of earnings news on Twitter, YouTube and Instagram, a result we confirm. Third, considering that Twitter facilitates earnings news dissemination and helps to attract retail ownership, we would expect analysts to issue more favorable recommendations for firms that communicate earnings results on Twitter. Though large investment banks focus on institutional clients, some brokerage firms serve both retail and institutional investors, and some brokers focus specifically on retail investors (Cowen et al., Citation2006; De Franco et al., Citation2007).Footnote5 We find that the mean of stock recommendations issued after earnings announcements is more likely to be higher than the mean of stock recommendations issued before earnings announcements for firms that communicate earnings results on Twitter, particularly for high retail ownership stocks.

This study contributes several results to the accounting literature. First, we perform textual analysis of tweets issued at earnings announcements to understand what sort of content firms post on Twitter and what information investors use to interpret earnings news. This evidence enhances previous studies on the use of Twitter in corporate communication (Bhagwat & Burch, Citation2016; Bollen et al., Citation2011; Curtis et al., Citation2016; Jung et al., Citation2018) and is relevant to investor relations departments in determining the content of Twitter posts to increase their impact. Relatedly, because of a more focused sample and a manual process of verifying all tweets, we can be more confident that we identify tweets that relate to earnings announcements as opposed to non-corporate communication.Footnote6 Higher data reliability coupled with tests that specifically distinguish between earnings announcement tweets and non-corporate communication on Twitter builds confidence that our results capture the usefulness of Twitter in corporate communication rather than higher visibility of firms present on Twitter.

Second, we highlight the usefulness of Twitter, YouTube and Instagram to retail investors, who have limited information sources and incur higher costs when processing complex financial information compared to institutional investors (Barber & Odean, Citation2008; Nofsinger, Citation2001). Our results are relevant to companies for whom retail holdings comprise a significant proportion of stock ownership, such as small and medium-size firms. The Investor Relations magazine 2021 survey highlights that retail investors hold over 50% more shares compared to holdings by institutional investors. Further, the survey revealed that Investor Relations departments find retail investors lack of knowledge as the biggest challenge in communicating financial news to them.’Footnote7

Third, we document no average benefit of disseminating earnings news on YouTube and Instagram. This result helps explain the relatively low uptake of these two platforms. The usefulness of social media platforms other than Twitter has not been explored so far in the accounting literature. For example, in their descriptive study, Jung et al. (Citation2018) identify firms that use Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, LinkedIn, Google+, and Pinterest in earnings dissemination. However, their empirical tests focus on Twitter ‘since the data suggest that Twitter is the preferred social media platform’ (Jung et al., Citation2018, p. 231). Our evidence, therefore, adds new insights to the accounting literature on the evolving use of the three social media channels – Twitter, YouTube and Instagram – and their efficacy in communicating corporate information. These results can help investor relations departments to determine how to efficiently allocate resources across the three social media platforms.Footnote8

Fourth, the study adds new evidence to the nascent literature that examines the use of social media outside the US (e.g., Gómez-Carrasco et al., Citation2020, who study firm Corporate Social Responsibility communication on social media for a sample of Spanish banks). We believe more international research is warranted because it is unclear whether the US evidence is generalizable to other countries with different institutional features, such as lower institutional holdings and ownership concentration (Bena et al., Citation2017).Footnote9 For example, Blankespoor et al. (Citation2014, p. 105) report that they do not ‘find compelling evidence of an association between tweeting activity and a change in small trade activity [proxy for retail trading]’ in the US, which stands in contrast to our evidence for the UK The need to validate results in non-US settings has been emphasized in several fields including the corporate governance literature (Crossland & Hambrick, Citation2007) and auditing (Simnett et al., Citation2016).

Finally, our results add new evidence to the corporate disclosure literature (Aboody & Kasznik, Citation2000; Healy & Palepu, Citation1995; McVay, Citation2006 Skinner, Citation1994; Trueman, Citation1986;). Our evidence highlights that the content of tweets and the choice of social media dissemination channels (Twitter, YouTube and Instagram) affects investor processing of earnings news. Our evidence on the usefulness of Twitter in disseminating earnings news echoes the recommendation of some regulators, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), who have endorsed the use of social media to disseminate corporate news to enhance corporate transparency.Footnote10

2. Background and Hypothesis Development

Corporate communication takes on many forms. Traditional channels through which companies disseminate earnings news include investor relations pages, regulatory and press releases, and investor and analyst calls. In recent years, companies started using social media to communicate with investors. Engaging with investors on social media to disseminate earnings news has important advantages compared to traditional channels. The firm communicates directly with investors, circumventing intermediaries such as Bloomberg or brokerage houses, which avoids delays in information sharing and distortions in the message’s content. ‘Pushing’ the message to users also reduces investors’ information acquisition costs. Furthermore, the message can be shaped to reduce information processing costs and meet the informational needs of various audiences, e.g., the company can highlight the main financial drivers behind firm results and use visual aids in communicating with retail investors.

Several studies have examined whether firms use Twitter to promote earnings news dissemination. Bhagwat and Burch (Citation2016) document that firms are strategic and tweet more frequently around positive earnings surprises. They also find that tweets related to earnings news increase price reaction to small earnings news, but not to small negative surprises, for less visible stocks. Blankespoor et al. (Citation2014) examine the impact on stock liquidity of firm tweets related to 233 earnings announcements for 79 technology firms between 2006 and 2009. They show that tweets that point to the earnings press release reduce the bid-ask spreads and depths. Jung et al. (Citation2018) document that managers are opportunistic and more likely to disclose positive news on Twitter. Focusing on posts written by investors, Bartov et al. (Citation2018) provide evidence that sentiment in investor tweets about a firm predicts the firm’s earnings news and stock returns in relation to earnings announcements. Curtis et al. (Citation2016) measure investor attention by their social media activity and find that abnormally high levels of investor attention are associated with higher sensitivity of market returns to earnings news and lower post-earnings announcement drift. Sprenger et al. (Citation2014) and Bollen et al. (Citation2011) study the sentiment of investor Twitter posts and find that high daily volume of Twitter activity and more positive sentiment about a stock predict next period returns. Gómez-Carrasco et al. (Citation2020) examine posts written by firms and by investors related to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) communication on social media and find that significant differences exist between the information interests of companies and stakeholders.

This study expands the literature by first examining the content of all tweets that contain earnings news and are issued at earnings announcements. Managers choose the content to present on social media and posts on Twitter can include information about the firm’s financial performance, e.g., revenue and growth, graphical elements, and the tone of the messages can convey managerial optimism about the news. We propose four hypotheses related to the content of tweets. First, we expect that investors will react more strongly to earnings news when Twitter communication contains financial information on revenue, costs, growth, operating performance and dividend/repurchases.Footnote11 This is because (i) the precision of such financial information tends to be higher compared to qualitative information (Hirst et al., Citation2008) and (ii) such financial information points to the drivers behind the earnings results and can help investors assess the persistence of earnings surprises (Ertimur et al., Citation2003).

Hypothesis 1a. Tweets related to earnings news that include financial information (about revenue, costs, growth, operating performance or dividend/repurchases) associate with incrementally stronger price reactions to earnings announcements.

Second, companies can increase the credibility of tweets by including references to the CEO or CFO or by including short statements made by the CEO or CFO. Linking the tweet’s content to top management can increase the tweets’ credibility as managers stake their reputation and social capital on the credibility of the content (Kelton & Pennington, Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2015). Consistently, Elliott et al. (Citation2018) draw on the social identity theory to predict that CEO tweets help build social bonds, which in turn increase trust in CEOs’ messages. Their experimental evidence suggests CEO tweets can facilitate the development of investor trust, which then helps mitigate the effects of negative information.

Hypothesis 1b. Tweets related to earnings news that include references to the CEO or CFO associate with incrementally stronger price reactions to earnings announcements.

Third, graphics help efficiently summarize granular and complex information (Tufte, Citation1997). Thus, visual elements can help draw investor attention to the firm’s post. Asay et al.’s (Citation2018) research demonstrates that including a photograph of the CEO with the earnings release increases the perceived credibility of the disclosure and associates with a stronger investor reaction. Elliott et al.’s (Citation2017) research shows that the use of pictures in a firm’s CSR report increases the perceived trustworthiness of the report’s content as well as increasing the likelihood that a subject will invest in a firm. Visual elements that can draw investor attention to a tweet also include a cashtag, which is a combination of a currency sign and the listing ticker, that groups tweets related to the financial performance of a firm. Cashtags clearly highlight company’s ticker in a tweet, which can attract investors’ attention to the message. Companies can also use cashtag links in tweets to direct the user to more granular information on their financial performance, thus reducing investors’ information search costs. We expect that investors will react more strongly to tweets that include more visual elements such as pictures, videos and cashtags.

Hypothesis 1c. Tweets related to earnings news that include visual elements associate with incrementally stronger price reactions to earnings announcements.

Fourth, managers may use a more optimistic tone in tweets in order to create a favorable impression of the earnings result. Mahoney and Lewis (Citation2004) document that managers vary the tone of the language within the earnings press release to strategically emphasize more favorable information. Davis et al. (Citation2012) report that investors react more positively to earnings press releases that use more optimistic words. In contrast, Henry and Leone (Citation2016) and Tetlock (Citation2007) report that investors place less weight on optimistic qualitative disclosure in earnings press releases compared to disclosures with a pessimistic tone.Footnote12 We expect that a more cautious tone of a tweet will signal higher credibility of the post and will lead to a stronger price reaction to the firm’s earnings news.

Hypothesis 1d. Tweets related to earnings news that are written in a more positive tone associate with incrementally lower price reactions to earnings announcements.

Our second research question focuses on the incremental usefulness of YouTube and Instagram, beyond Twitter, for earnings dissemination. Managers can choose the portfolio of social media platforms through which to disseminate earnings results. Twitter, a microblogging site, emphasizes short text messages.Footnote13 Tweets can include text, hyperlinks to outside sources, pictures and videos. By contrast, YouTube is an online video sharing platform, and Instagram is primarily a photo sharing platform. Smith et al. (Citation2012, p. 104) argue that the three social media platforms ‘represent different types of social media, and that each site has its own unique architecture, culture and norms. Users visit these sites with slightly different intentions, interact in diverse ways,’ meaning the three platforms can potentially reach different audiences, thus increasing the reach of earnings news. Den et al. (Citation2014, p. 1) report that ‘the information emergence and propagation is faster in social textual stream-based platforms [Twitter] than that in multimedia sharing platforms [YouTube] at micro user level.’ However, it is unclear if YouTube and Instagram are useful in disseminating earnings news incrementally to Twitter. Thus, our second hypothesis examines the incremental usefulness of YouTube and Instagram for earnings news dissemination.

Hypothesis 2. Posts on YouTube and Instagram related to earnings news associate with incrementally higher price reactions to earnings announcements.

To better understand why investors react to the content of tweets and to posts on YouTube and Instagram, we examine the role of retail ownership. Compared to institutional investors, retail investors have limited information sources and incur higher costs when processing complex financial information (Barber & Odean, Citation2008; Nofsinger, Citation2001). Consistent with retail investors’ lower ability to acquire and process information, studies find that retail investors underreact to new information (Ben-Rephael et al., Citation2017), buy attention-grabbing stocks that subsequently disappoint (Barber & Odean, Citation2008), and tend to herd leading to temporary stock mispricing (Barber et al., Citation2009). We expect that retail investors will find social media posts particularly helpful in interpreting earnings news because information in social media posts is more easily accessible and easier to process. Thus, our third hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 3. There is an incremental price reaction to earnings news communicated on Twitter, YouTube and Instagram when retail holdings are high.

3. Data

We first manually identify the social media accounts of FTSE 100 firms on Twitter, YouTube and Instagram. To do this, we search the social media for company names and verify the correct link by checking the nature of the posts and whether they link with the corporate site. We verify each account manually to eliminate cases where the name reflects a user group or a community unrelated to the firm. We then use Crimson Hexagon, a social analysis platform, to identify the posts. Crimson Hexagon contains over one trillion posts from various social media platforms and is considered ‘the largest repository of public social data’.Footnote14 We then search for the semi-annual and annual earnings announcements on social media over the period January 2015 to April 2018. We read each post to ensure it includes information related to financial results and is not part of the firm’s non-corporate communication (e.g., product advertising), or unrelated to earnings (e.g., CSR disclosure). This allows us to identify investor-focused tweets as opposed to customer-centric communication, which ensures we capture corporate communication targeting investors around earnings announcements. We collect financial data from Compustat Global Fundamentals and market data from Compustat Global Security Daily files. Analyst data is from international I/B/E/S files and stock ownership data is from Factset. Our final sample includes 383 earnings announcements by 93 unique firms.Footnote15 Appendix A explains how we arrive at the final sample.

We focus on earnings announcements because they are an important and persistent component of corporate communication (Kothari, Citation2001) and have a significant impact on investor portfolio allocation decisions (Ball & Brown, Citation1968 and Beaver, Citation1968), properties of analyst forecasts (Altinkilic & Hansen, Citation2009 Ivković & Jegadeesh, Citation2004; Schipper, Citation1991;), and managerial compensation and turnover (Matsumoto, Citation2002). Moreover, clustering of announcements within a relatively short window means investors face increased information processing costs that social media can reduce (Hirshleifer et al., Citation2009). Online Appendix A illustrates that between 26 and 35 firms announced their results in a three-day window between 5th and 7th March 2019.

We focus on the UK as it offers a unique setting to examine the effect of earnings news communication on social media. First, compared to the US, UK firms have more dispersed ownership (Goergen & Renneboog, Citation2001 Leech, Citation2001) and regulatory constraints introduced through the Cadbury (Citation1992), Hampel (Citation1998) and Newbold (Citation2001) corporate governance committees reproached institutional investor to become more passive and rely more on public sources of information (Faccio & Lasfer, Citation2000 Goergen & Renneboog, Citation2001; Stapledon, Citation1996). Second, retail ownership in UK listed firms is relatively high compared to US firms and social media communication is likely to be particularly important for this investor group.Footnote16 Thus, understanding the UK context is conducive to understanding how different audiences (retail vs. institutional) react to earnings communication through different social media channels (Twitter, YouTube and Instagram).

presents the time-series distribution of earnings news posts across the three social media platforms. Around 56% of FTSE 100 firms used Twitter to announce their financial results in 2015 with the proportion increasing to almost 70% in the first half of 2018. The frequency of posts on YouTube and Instagram is smaller, although it increases substantially over time: the proportion of YouTube posts increases from around 2% in 2015–13% in 2018, a 6.5-fold increase, with a similar pattern for Instagram.Footnote17

4. Research Methods

4.1 Twitter and the Content of Tweets

To identify firms that use Twitter to disseminate earnings results, we create an indicator variable, Tweet, which takes a value of one if a firm issued at least one earnings-related tweet on the earnings announcement day, and zero otherwise. This captures the overall firm communication on Twitter at the earnings announcement. Next, we look at the content of tweets that a firm posted on Twitter. Firms can either issue simple messages that alert investors to firms results, e.g., ‘3i Group plc has announced strong half year results this morning, with both the Private Equity and Infrastructure businesses performing well: https://www.3i.com/investor-relations ‘ or can highlight specific information, e.g., ‘Diageo preliminary results; Organic net sales flat, operating margin up 24bps, free cash flow of £2bn, full year dividend up 9%’. They can also enhance tweets with pictures and videos or increase tweets’ credibility through CEO or CFO testimonies, e.g., ‘Group CEO Stephen A. Carter: steady operational & financial progress in fourth year of our acceleration program http://goo.gl/EwSCem.’

To capture the financial information contained in tweets issued at earnings announcements (about revenue, costs, growth, operating performance or dividend/repurchases), we define several indicator variables. Sales equals one if any of the tweets issued at earnings announcement reference revenue and is zero otherwise. Costs indicates whether any of the tweets mention costs, and Growth is a dummy variable equal to one if any of the tweets mention growth. Operating equals one if any of the tweets refers to operating performance and zero otherwise. Dividend/repurchase is an indicator variable equal to one if any of the tweets refer to a dividend or a repurchase, and is zero otherwise.

We determine whether any of the tweets reference the CEO or the CFO and define a variable CEO/CFO equal to one in such instances. As an extension, we also look at whether referencing analysts in any of the tweets can increase price reactions to earnings news. Mentioning analysts or analyst reports can increase the credibility of the news. Analyst takes a value of one if any of the tweets references analysts and is zero otherwise. To capture visual enhancements to tweets that can grab investor attention, we code as one (i) an indicator variable Picture or video if any of the tweets include either a picture or a video, and (ii) an indicator variable Cashtag if a firm uses cashtags. Finally, we measure the positive tone of the Twitter communication at earnings announcement, Tone, by searching for favorable words in all the tweets. We select most commonly used keywords that identify positive tone words from the Loughran and McDonald (Citation2011) dictionary. Appendix B presents the definitions of the variables used in the analysis and the keywords we use in coding the variables, thus capturing the content of tweets.

4.2 Characteristics of Corporate Communication on Twitter

To capture the characteristics of corporate activity on Twitter, we count the number of firm-initiated tweets (#Twitter posts) to capture the intensity of firm communication. If a company has more than one account on a social platform that it uses to announce earnings results, we sum up the activity across all accounts.Footnote18 Crimson Hexagon’s software ForSight calculates the total number of followers for the firm, which we measure seven days before earnings announcements (#Twitter Followers) and use it to capture firm following. A larger number of users following a firm should facilitate the spread of the message. We count the cumulative number of retweets, likes and comments (Twitter User Eng) to gauge user engagement with the firm’s Twitter posts. Higher user engagement should facilitate impounding of news into the share price.

4.3 YouTube and Instagram Posts

Next, we collect information for YouTube and Instagram posts on the earnings announcement day. A dummy variable YouTube takes a value of one if a firm posted at least one YouTube video related to financial results, and is zero otherwise. Instagram takes a value of one if a firm posted at least one earnings results related message on Instagram, and zero otherwise. We collect information on the number of firm’s posts on both social media platforms (#YouTube posts and #Instagram posts) and measure user engagement through cumulative likes (also dislikes on YouTube) and comments on all posts (YouTube User Eng and Instagram User Eng).Footnote19

4.4 Earnings Surprises and the Regression Model

Consistent with previous studies (Datta & Dhillon, Citation1993; Jegadeesh & Livnat, Citation2006 Mendenhall, Citation2004;), we measure news revealed at earnings announcements by the standardized difference between actual earnings, , and analyst consensus forecast,

, based on the latest analyst forecasts in a 90-day period before earnings announcements. To make earnings surprises comparable across firms, we scale this difference by the standard deviation in analyst EPS estimates,

, i.e.,

We then interact the earnings surprise with the content and characteristics of social media posts and regress cumulative abnormal returns on the surprise and its interaction terms. We measure cumulative abnormal returns in a four-day window around the earnings announcement, CAR(-1,2). The basic regression takes the form:

(1)

(1)

where

is a vector that captures (i) the content and characteristics of tweets, and, in further analysis, (ii) firm activity on YouTube and Instagram.

captures the incremental price reaction at earnings announcements for firms that communicate through social platforms we study, i.e., a more efficient impounding of earnings news into the stock price. Standard errors are adjusted for heteroskedasticity and within-firm correlation.

We recognize that firms self-select to disclose information on social media and that anticipating higher benefits from such disclosure prompts firms to post earnings news on social media. The decision to disclose earnings news on social media can be modeled as

and

where

captures the latent decision to disclose earnings news on social media and the model is standardized so that non-zero values capture positive expected benefits from social media posts. A consistent estimation of Equation (1) requires conditional estimation based on the outcome of the latent model to allow the effect of the firm’s choice to communicate on social media to affect price reactions to earnings announcements. The estimation can be performed consistently by including an inverse Mills ratio from the model predicting the choice to communicate earnings news on social media in Equation (1). Specifically, the conditional regression takes the form

(2)

(2)

where

and

This conditional model is also referred to as an endogenous treatment regression model (Cameron & Trivedi, Citation2005; Wooldridge, Citation2010). We use Equation (2) to account for the selectivity in the firm’s choice to post earnings news on social media.

4.5 Controls

The set of controls in Equations (1) and (2) includes variables that previous studies have identified as being associated with price reactions to earnings announcements (Collins et al., Citation2009 Francis et al., Citation2002;). Lower information environment quality means investors attach more weight to new information as it becomes available, which can increase price reactions to earnings news. We count the number of analysts following a firm and include its logarithms, ln #Analysts, as a higher analyst following associates with a higher-quality information environment. Investors may attach more weight to earnings news when the heterogeneity in investor expectations is higher. We capture the heterogeneity in investor opinions by the stock price volatility, Volatility, calculated as the stock price standard deviation measured over two months ending two weeks before earnings announcements and scaled by the mean stock price. Though the FTSE 100 index includes the largest listed firms, there remains considerable variation in size between the top and bottom index percentile. We use the logarithm of the firms’ market capitalization, ln MV, to capture the differences in media and investor attention to firms within the index. We control for the (logarithm of) number of institutional investors in a stock, ln #IO, as greater investor dispersion should associate with stronger price reactions. We measure the proportion of retail ownership, Retail ownership, as higher retail ownership can lead to less efficient pricing of earnings news and weaker price reactions. Earnings news are more important for growth stocks, captured by the book-to-market ratio, B/M, as they reveal how firms convert growth options into cash flows. We control for leverage, Leverage, as investors may react more strongly to disappointing earnings news for financially distressed firms. Social media platforms compete with traditional media as a medium for information diffusion (Kayany & Yelsma, Citation2000). We control for the media coverage intensity of a firm in a 30-day window ending seven days before earnings announcements, news intensity. We capture the intensity of media coverage by the weighted average of (i) the number of articles mentioning a firm and (ii) the prominence of a company in the media article. Year and industry effects account for the heterogeneity in price reactions over time and across industries and the resultant serial correlation of residuals.

presents descriptive statistics for the variables in Equation (1). Panel A reports descriptive statistics for the price reaction, Twitter usage and the content of all tweets issued at earnings announcements. The average abnormal price reaction to earnings announcements is 0.18%, while 63.97% of firms use Twitter to communicate earnings results. A considerable proportion of earnings-day Twitter communications refer to financial information. For example, around 43.1% of Twitter communications mention revenue, 43.09% mention growth, 13.8% costs and 5.2% operating performance. We find that 20.7% of communications include references to dividend or repurchase payouts, and around 36.2% mention the CEO/CFO or short statements from the CEOs highlighting the firm’s performance. Only 6.9% of Twitter communications mention analysts. Close to 15% of Twitter communications include a graphical element, and 12.65% feature a cashtag. Around 82.8% of communications include positive tone words.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Panel B reports descriptive statistics for the characteristics of the tweets issued at earnings announcements. Firms release on average 7.641 tweets and have on average 26,430 Twitter followers.Footnote20 On average, users commented or retweeted firm posts 114.571 times. Panel C reports results for the usage of YouTube and Instagram in relation to earnings announcements. The proportion of firms using YouTube and Instagram is 6.01% and 4.18%, respectively. There were around 11.609 YouTube likes and comments on all firm posts on YouTube, and 250.438 likes and comments on all Instagram posts issued at earnings announcements. On average, firms released three videos and posted over two Instagram messages. Descriptive statistics for control variables in Panel D are similar to other studies that focus on FTSE 100 firms (Abraham & Cox, Citation2007; Skovoroda & Bruce, Citation2017). Panel E reports Pearson correlations between the indicator variables capturing the content of tweets and we observe that the signs of correlations are positive on average.

5. The Content of Tweets and Price Reactions to Earnings Announcements

Panel A of reports regression results for Equation (1), for which we include interaction terms between the earnings surprise and the variables capturing the content of tweets (for brevity, we do not report the intercept in any of the tables). We document that investors react more strongly if the tweets include specific references to financial information. The economic effect of the content of tweets is significant: focusing on standardized coefficients, a one standard deviation increase in an earnings surprise for firms whose Twitter communication references revenue associates with a 22%-higher price reaction.Footnote21 A similar magnitude increase in earnings surprises for Twitter communication that mentions costs associates with a 34% lower price reaction, and tweets that refer operating performance associate with a 17%-stronger price reaction. These results are consistent with hypothesis H1a, which states that mentioning financial information in Twitter communication helps investors to assess the persistence of earnings surprises, which increases the magnitude of price reactions to earnings news. References to either dividends or buybacks associate with lower price reactions. Contrary to the prediction of the dividend signaling theory, prior research finds weak or no support for the dividend signaling hypothesis and repurchases can signal lower earnings persistence.Footnote22 Thus, mentioning dividends or buybacks in earnings announcements provides either no signal about the persistence of earnings or signals lower earnings persistence, which should correlate with lower price reactions to earnings surprises.

Table 2. Regression results for content of tweets.

Consistent with hypothesis 1b, we document that Twitter communication that mentions the CEO or the CFO associates with stronger price reactions to earnings news. This evidence supports the notion that mentioning top management in a tweet adds credibility to the earnings results. A one standard deviation increase in an earnings surprise for Twitter communication that refers to the CEO or the CFO correlates with a 16%-stronger price reaction. In contrast, we find no significant effect if tweets mention analysts or analyst reports. Though the coefficient on the interaction term Analyst*SUE is positive, it is not significant at conventional levels.

We find that visual elements included in Twitter communication, such as cashtags, pictures and videos, have a positive effect on price reactions to earnings news, which supports hypothesis 1c. This result is consistent with the view that graphical elements help to attract investors’ attention to firm’s posts. A one standard deviation increase in an earnings surprise issued jointly with Twitter communication that contains a cashtag associates with 28%-stronger price reactions, while the inclusion of pictures or videos increases price reaction by 10%.

Twitter communication in which managers use a positive tone to increase the favorableness of the news is associated with weaker price reactions. This result is consistent with hypothesis 1d and suggests that investors may see through the impression management that firms employ to boost the impact of news. Posts with an overall more positive tone on Twitter, in addition to a one standard deviation increase in an earnings surprise, associate with 30%-lower price reactions. Jointly, our results suggest that the content of the tweets has a material effect on how this social media channel affects price reactions to earnings news.Footnote23

In the Online Appendix D, we present two further tests. First, we re-calculate the measures capturing the content of tweets relating to sales, costs, growth, operating performance and dividend/repurchases to account for the total length of Twitter communication at earnings announcement. This test is motivated by the possibility that a single tweet out of ten that mentioned certain information, e.g., about revenue, could have a different impact compared to a single tweet a firm made at earnings announcements that mentioned revenue. The second test we report recognizes that the tone of tweets can also be measured by a net value of positive and negative words and by scaling the number of positive words by the total word count in all tweets issued at earnings announcements. The conclusions from both tests are consistent with our main findings.

5.1 Addressing the Selectivity Concern

This section presents results that help to address the concern that unobserved firm characteristics could correlate with both the firm’s decision to post earnings results on Twitter and price reactions to earnings news, thus confound the relations we examine. Column ‘Firm effects’ in Panel A of reports results for Equation (1) augmented with firm effects. We run the Hausman test with the null hypothesis that the random effects model is preferred due to higher efficiency to select between the random and fixed effects models. The alternative hypothesis is that the fixed effects model is at least as consistent, thus preferred. We cannot reject the null hypothesis and choose the random effects model. Regression results for the firm effects model are consistent with our main conclusions.

Column ‘Conditional pricing model’ reports results from estimating the conditional price reaction model (2). The first-stage regression estimates the likelihood that a firm will communicate earnings news on Twitter. The first instrument is the proportion of FTSE 100 firms that communicated on Twitter in a three-week period before the focal firm’s earnings announcements, Avg Twitter use. Building on the network literature (Leary & Roberts, Citation2014), we expect that the decision to use social media will depend on the behavior of company’s peers. However, we do not expect that past peers’ choices to use social media will affect price reaction to the focal firm’s current earnings announcement. The second instrument is an indicator variable that determines whether a firm has been active on Twitter between 90 and seven days before earnings announcements, Non-corporate tweets. Companies engage with customers on their Twitter account by posting news about their products and services. This non-corporate communication builds familiarity with the platform and experience of managing the social media dialogue with users, which should increase a firm’s propensity to post corporate news on social media. However, a firm’s previous use of Twitter for non-corporate communication, e.g., advertising, should not affect how investors react to earnings news. Thus, both instruments meet the relevance condition and the exclusion restriction.

First-stage regression results show positive coefficients on Avg Twitter use and Non-corporate tweets. Thus, the experience of using Twitter and the proliferation of peers’ use of Twitter for corporate communication increase the likelihood that a firm will communicate earnings news through this channel. Column ‘Second stage’ reports results from estimating Equation (2) when we include the inverse Mills ratio to control for selectivity in firms communicating earnings results on Twitter. The conclusions from this regression are similar to our main findings. Jointly, tests that address selectivity in corporate disclosure on Twitter support our main conclusion that investors find earnings posts on Twitter useful in interpreting financial information. However, we acknowledge we cannot completely rule out that selectivity explains our results.

5.2 Retail Ownership and Characteristics of Twitter Communication

We expect that social media communication will be particularly important for investors with high information acquisition and processing costs, such as retail investors. To test this proposition, we first create an indicator variable High retail ownership, which takes a value of one if retail ownership is in the top quartile of all FTSE 100 constituents, and is zero otherwise. We then augment the regression model with interaction terms between High retail ownership and Tweet and SUE.Footnote24 Column ‘Retail ownership’ in Panel B of reports a positive coefficient on the triple interaction term SUE*Tweet*High retail ownership, which suggests Twitter communication helps retail investors to more effectively process earnings information. This result supports hypothesis 3.

Next, we examine whether the characteristics of Twitter communication, such as the frequency of tweeting, affect the usefulness of Twitter in disseminating earnings results. Firms can boost the impact of Twitter communication by posting a larger number of tweets related to earnings announcements. We create an indicator variable, High #Tweets, which equals one for the tercile of stocks with the highest number of Twitter posts, and is zero otherwise. Column ‘Number of tweets’ documents that investors do not react more strongly to earnings news for firms that post a larger number of tweets.

If Twitter communication helps firms to reach a wider audience, its impact should increase as a larger number of users engage with the firm’s tweet by either commenting on it or retweeting the post. Variable High #Twitter RLC takes a value of one for the top tercile of stocks based on the number of retweets, likes and comments, and is zero otherwise. Column ‘Investor engagement’ documents that higher user engagement does not increase price reactions to earnings news.

Firms may build large followings on Twitter, which in turn can facilitate the dissemination of earnings news. We create an indicator, High # Followers, which equals one for the tercile of stocks with the highest number of Twitter followers, and is zero otherwise. Column ‘#Followers’ reports results for the regression model augmented with an interaction term for the number of Twitter followers. The information on the number of Twitter followers is available only for the last two years (2017–2018), which reduces the number of observations to 192. We can collect the data for semi-annual results only, which we extrapolate to annual results. We do not find that a higher number of Twitter followers increases the earnings response coefficient. We conclude that the characteristics of firm activity on Twitter, such as the number of posts, investor engagement and a high number of followers on Twitter, do not affect investor responses to earnings news.

5.3 Further Tests: The Effect of Earnings Announcements Clustering and of Small Earnings Surprises

To shed more light on when tweets are more useful, we examine incremental price reactions on days when multiple firms announce their results. Hirshleifer et al. (Citation2009) document that when multiple firms announce on the same day, immediate price and trading volume reactions are weaker, and the post-announcement drift is stronger, consistent with limited investor attention on such days. We test whether social media communication can partially alleviate this effect. Specifically, we count the number of earnings announcements one day before and on the focal company’s announcement day to capture the intensity of peer firms’ earnings announcements, # of earn announcements. We then interact # of earn announcements with SUE*Tweet. Column ‘Multiple earnings announcements on the same day’ in Panel C of documents a positive coefficient on the interaction term SUE*Tweet*# of earn announcements, which suggests that Twitter communication helps attract investors’ attention to firm results on high news days.

Jung et al. (Citation2018) suggest that firms are more likely to report positive news on Twitter and we build on their analysis to understand if tweets increase price reaction to positive news and reduce price reaction to negative news, as well as examining whether tweets can increase price reactions to small surprises. Small positive surprises are not headline-grabbing and investors may ignore them, focusing instead on firms with large positive or negative surprises (Hirshleifer et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, firms may attempt to provide more context to explain small negative news to avoid the market penalty for missing analyst estimates (Lopez & Rees, Citation2002). To test these propositions, column ‘Small surprises’ in Panel C disaggregates SUE into four components: positive earnings surprises that are higher than 0.1 pence, positive SUE; small positive surprises in a range [0,0.1], small positive SUE; small negative surprises in a range [−0.1,0), small negative SUE; and negative surprises smaller than −0.1 pence, negative SUE. The cut-off point of 0.1 reflects the bottom decile of the unscaled mean surprise of 1.017, but the conclusions are robust to other cut-off points. We then interact the four earnings surprise terms with Tweet. The positive coefficient on the interaction small positive SUE*Tweet and a negative coefficient on the term small negative SUE*Tweet are consistent with social media communication boosting price reactions to relatively small earnings surprises and moderating the negative effect of small negative news. The coefficient on positive SUE*Tweet is not significant, which suggests the result in Jung et al. (Citation2018) on incrementally higher price reaction to positive surprises communicated on Twitter may be confined to small positive surprises.

6. YouTube and Instagram Communication

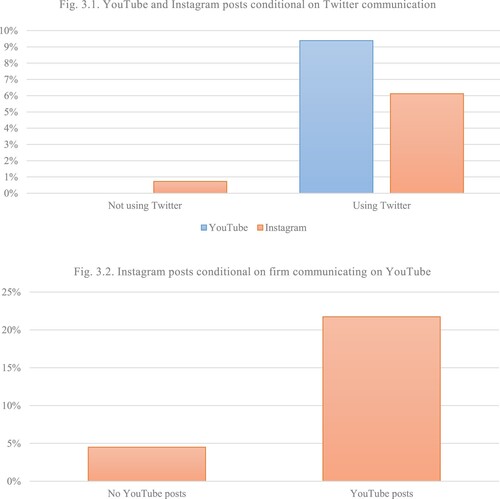

This section first examines the frequency with which companies use YouTube and Instagram conditional on firms communicating on Twitter. .1 shows that firms are more likely to post earnings results on YouTube and Instagram when they also communicate on Twitter (the differences in the proportion of YouTube and Instagram posts between Twitter and non-Twitter firms are significant at 1%). .2 expands this analysis by showing that firms are more likely to use Instagram when they also post on YouTube (the z-test for the difference in proportions is −4.44). Jointly, the results shown in suggest that firms are more likely to use YouTube and Instagram when they already post their results on Twitter.

Figure 3. YouTube and Instagram posts: complementary effects. .1 reports the proportion of firms that use YouTube and Instagram to communication earnings announcements conditional on the firm also communicating on Twitter. .2 documents the percentage of firms using Instagram conditional on the firm also communicating on YouTube.

Next, we examine whether earnings communication on YouTube and Instagram has an incremental effect on price reactions to earnings news beyond Twitter posts. The first columns of report results for Equation (1), which controls for Twitter earnings posts, when we include indicator variables for YouTube and Instagram earnings posts and their interactions with the earnings surprise. The negative coefficient on SUE*YouTube suggests that, on average, YouTube communication reduces price sensitivity to earnings news. This result suggests that, on average, YouTube videos are ill-suited to communicate financial information disclosed in earnings announcements. This result may reflect that, compared to pictures, videos included with text may obscure the message. Indeed, Sundar (Citation2000) finds that people can better recall and process picture information than they can video information. This finding is also consistent with the information overload theory, which predicts that multimedia can inhibit information processing due to a cognitive overload (Chandler & Sweller, Citation1991; Sweller et al., Citation1998; Wong et al., Citation2012). Yang et al. (Citation2020) results further support this view, finding that the use of multimedia weakens the assimilation of textual information among Kickstarter investors. Instagram posts, on average, are not associated with incremental price reactions, which suggests investors do not perceive this channel as incrementally useful to YouTube and Twitter in disseminating earnings news. Jointly, the evidence in Panel A of suggests that, on average, YouTube and Instagram do not facilitate the dissemination of earnings results, a result inconsistent with hypothesis 2. This finding may reflect the fact that Twitter already allows for pictures and videos, which may reduce the appeal of YouTube and Instagram, which focus on these media. Moreover, companies frequently use the same infographics and videos on Twitter as they do on YouTube and Instagram, further reducing the competitive advantage of YouTube and Instagram.

Table 3. Price reactions to YouTube and Instagram communication.

Table 3. Continued.

Column ‘Firm effects’ repeats the analysis after including random firm effects in Equation (1) and the conclusions remain unchanged. Column ‘Conditional pricing model’ reports results for Equation (2), which controls for the selectivity in the firm’s choice to post on YouTube and Instagram. The first-stage regression models the likelihood that a firm will post on either YouTube or Instagram, in addition to Twitter. As instruments, we use (i) the proportion of peers posting on Twitter and either YouTube or Instagram in a 60-day window before the focal firm’s earnings announcements, Avg YouTube and Instagram use, and (ii) whether a firm posted non-corporate content on either YouTube or Instagram over a 60-day window before earnings announcements, Non-corporate YouTube or Instagram posts. We do not expect peers’ choices to use Instagram or YouTube for earnings dissemination nor the firm’s non-corporate posts on YouTube and Instagram to increase price reaction to earnings announcements, but they should affect the firm’s propensity to post earnings results on these two platforms. First-stage regression results document significant loadings on the two instruments and second-stage regression results continue to show no average incremental positive effect on stock returns from posting earnings news on YouTube or Instagram.

In the Online Appendix E, we also examine the incremental role of posts related to earnings results on Facebook. We find that companies do not often post earnings-related information on Facebook – the frequency of earnings posts on Facebook increases from 3.1% in 2015 to 6.2% in 2018. Further, we do not find that posts on Facebook associate with incremental price reactions to earnings announcements, which mirrors the evidence for Twitter and Instagram.

6.1 Characteristics of YouTube and Instagram Communication

Companies can ‘boost’ the impact of YouTube and Instagram communication by posting several messages on the two platforms at earnings announcements. Consistently, column ‘#posts’ in Panel B of reports a positive incremental effect from a higher number of YouTube videos released by a firm as measured by the positive coefficient on SUE*#YouTube posts. This effect moderates the average negative effect from posting on YouTube captured by the negative coefficient on SUE*YouTube. This result is consistent with the notion that a higher firm engagement on YouTube can offset the negative average effect of YouTube posts on price reactions to earnings news. A higher number of Instagram posts seems to have no incremental effect. Column ‘User engagement’ shows no evidence that a higher user engagement on YouTube or Instagram associates with stronger price reactions to earnings news, which is similar to what we find for Twitter.

The emphasis on videos and graphics to present information on YouTube and Instagram may appeal to retail investors. Column ‘Retail investors’ reports results augmented with interaction terms with High retail ownership. The positive coefficient on the triple interaction SUE*YouTube*High retail ownership suggests that YouTube videos posted by companies with high retail ownership moderate the average negative effect from positing earnings results on YouTube. This evidence is consistent with YouTube posts helping retail investors to better understand the content of earnings news. Instagram does not associate with incremental pricing effects for stocks with high retail ownership. Overall, we find very weak support for hypothesis 3 and only for YouTube as dissemination channel.

6.2 Additional Tests

The Online Appendix F presents three additional results. First, if posts on social media, such as Twitter and YouTube, meet retail investors’ demand for the information communication channel, we would expect retail investors to increase their holdings in firms that use these social media to disseminate corporate news, a result we confirm. Second, considering that Twitter facilitates earnings news dissemination and helps to attract retail ownership, we would expect analysts to issue more favorable recommendations for firms that communicate earnings results on Twitter. Consistently, we find that the mean of stock recommendations issued after earnings announcements is more likely to be higher than the mean of stock recommendations issued before earnings announcements for firms that communicate earnings results on Twitter, particularly for high retail ownership stocks. Third, we find no evidence of an incremental post-earnings announcement drift for firms that communicate on social media. Thus, our results are likely to reflect more efficient information pricing at earnings announcements rather than irrational investor behavior at earnings announcements for firms that use social media.

7. Conclusions

This study examines (i) how the content of tweets and (ii) posts on YouTube and Instagram related to earnings announcements facilitate the dissemination of earnings news. We observe that what companies mention in their Twitter communication has an incremental effect on how investors interpret earnings results. Tweets about earnings announcements are particularly useful when retail ownership in a stock is high. Incrementally to Twitter, YouTube and Instagram do not, on average, promote stronger price reactions to earnings results.

This study is subject to limitations. First, the small sample size means our results may be period or sample specific; thus, further research is required to build confidence in the generalizability of the results. Second, our evidence is based solely on a sample of UK firms, leaving the door open for future studies to examine whether the results can be replicated in other institutional settings. Third, we attempt to address endogeneity in several ways; however, we cannot preclude that the firm’s use of social media in communicating earnings news correlates with other corporate decisions or firm characteristics, which in turn affect price responses to earnings news. Future research could explore the decision process underlying firms’ choices to communicate earnings news on social media, e.g., through interviews, to shed more light on this issue. Such evidence would be helpful in uncovering potential correlations that could muddle the relation modeled in this and earlier research linking the use of social media to earnings dissemination.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Editor, Beatriz García Osma, two anonymous referees and Daniel Blaseg, Andreas Charitou, Joshua Ronen and participants at the 2019 SKEMA Fintech and Digital Finance conference and the 2019 European Accounting Association congress for helpful comments. We thank FTI Consulting and Ge Ge for help with data collection. All errors and omission are our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2022.2084759

Notes

1 Bollen et al. (Citation2011), Curtis et al. (Citation2016), Bhagwat and Burch (Citation2016), Jung et al. (Citation2018) only examine whether Twitter facilitates the dissemination of earnings news, not the content of tweets.

2 We do not include Facebook in our main analysis because Facebook’s market positioning is to create a social network of ‘friends’ who can view and comment on the content posted on Facebook. Thus, users are more likely to look to Facebook for social interactions within their social network than for corporate news. Consistently, our sensitivity tests show that half the number of companies in our sample that used YouTube and Instagram used Facebook to disseminate earnings results in 2018. Facebooks earnings posts were typically brief and highlighting that the financial results were available on the corporate page with the link to the report. For example, International Hotel Group post on Facebook states ‘Today we announced our Full Year Results for 2020. Read in full here: http://ihg.co/6184HcWNY’. Further tests show that Facebook posts of earnings results do not associate with incrementally significant price reactions to earnings news.

3 Social media communication is costly in terms of the time and resources necessary to prepare the message and the audio-visual content, engage with the audience, and respond to potentially unfavourable comments. The cost of social media communication also includes staff costs and compliance costs as material posted on social media must meet legal and regulatory guidelines. Costs of promoting engagement on social media can also be nontrivial, e.g., promoting a trend on Twitter can cost $200,000 per day and promoting a single tweet costs $4 per engagement. These costs increase with the number of social media platforms a firm uses.

4 The evidence that graphical elements enhance the appeal of tweets is consistent with laboratory experiments in Elliott et al. (Citation2017).

5 Because analyst compensation is tied to trading volume both at retail-focused and full-service brokers, analysts have an incentive to recommend stocks of interest to retail investors to promote retail trading in these stocks. Cowen et al. (Citation2006, p. 123) highlight that even in full-service investment banks, which include several bulge-bracket brokers, analyst compensation is based on, among other things, ‘trading volume by retail client’.

6 Previous studies are not always successful in identifying tweets related to earnings announcements. For example, Bhagwat and Burch (Citation2016, p. 13) acknowledge that ‘[W]e recognize there could be tweets we classify as financial that are not related to earnings.’ Blankespoor et al. (Citation2014, p. 86) state that they gather ‘[P]otential Earnings Announcement Observations (within Firm Twitter Period)’ without verifying if the tweet relates to earnings announcements.

7 For the Investor Relations magazine 2021 survey, see https://research.irmagazine.com/reportaction/ Retail_Investors_2021/Marketing

8 We do not look at social media like Google+, Pinterest and LinkedIn because Jung et al. (Citation2018) report that less than half of firms that use Twitter, YouTube and Facebook use these other platforms. Specifically, Jung et al. (Citation2018) report that 28.5% of firms in their sample used LinkedIn to disseminate earnings results, 10.5% Google+ and 5.5% Pinterest compared to 44.2% using Facebook and 47.5% using Twitter. Thus, if a platform is not popular among companies, we would not expect it to provide a meaningful earnings dissemination channel.

9 Faias and Ferreira’s (Citation2017) study of 45 countries finds that outside the U.S., institutional holdings increased on average from 10% in 2000 to 20% in 2010, a fraction of the institutional ownership in the U.S. that stands above 70%. Thus, it is not clear whether U.S. evidence applies to other countries where institutional holdings are less prevalent.

10 In 2013, the SEC accepted the use of Twitter to communicate corporate announcements. In 2014, it allowed firms to release financial information via social media (SEC, Citation2013).

11 We consider tweets to contain financial information if they mention at least of the following categories of information: sales, costs, growth, operating performance, and dividend and repurchases.

12 The U.K. Financial Conduct Authority guidance states that companies can communicate on social media if the communication is ‘fair, clear and not misleading’ and that social media communication does not substitute for formal notification of information concerning a change in financial condition, performance or expectation of performance if the change would be likely to lead to a substantial share price movement, see https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/guidance-consultation/gc14-06.pdf

13 At launch in 2006, Twitter allowed up to 140 characters for tweets, which increased to 280 characters from November 2018.

14 McClellan et al. (2017, 497) use Crimson Hexagon to collect tweets related to depression and suicide and emphasise that ‘Crimson Hexagon provides more comprehensive data compared to other tools that have been used in previous studies, such as the free Twitter application interface’. Jiang and Shen (Citation2017) use Crimson Hexagon to study how Twitter covers business scandals, Ceron et al. (Citation2014) to examine the relation between social media sentiment and political preferences, and Uede et al. (Citation2017) to analyse the relation between Twitter coverage of celebrity suicides and population suicide rates.

15 Data requirements led us to exclude some FTSE100 constituents. For example, Royal Mail and Merlin Entertainments became part of the FTSE 100 index immediately following their IPOs and have insufficiently long history to allow us to calculate certain control variables, such as the stock return volatility.

16 The U.K. Office for National Statistics listed individual investors as the largest ownership group for FTSE 100 stocks in 2016 after ‘Rest of the world’ and ahead of domestic insurance companies and pension funds. Bena et al. (Citation2017) report that only 12% of U.K. listed stocks were owned by domestic institutional investors, compared to 67% in the U.S. (foreign institutional ownership was 20% and 8%, respectively). The importance of retail investors is reflected in corporate communication. To illustrate, the annual report of Saga plc recognises that ‘Saga has a diverse shareholder register which is formed of both institutional and retail ownership, the latter numbering over 170,000’ (Saga, Citation2018, 82).

17 In untabulated results, we find that Twitter’s use varies between 100% for consumer-facing industries, such as consumer durables (e.g., cars, TVs and furniture), and 46.9% for business-to-business industries, such as wholesale and manufacturing. The use of YouTube and Instagram also tends to be more pronounced among customer-oriented industries, such as the non-durables industry (e.g., food, tobacco, textiles, apparel, leather, toys). The Pearson correlation between Twitter and YouTube earnings news posts is 0.190 and between Twitter and Instagram posts is 0.130. The correlation between YouTube and Instagram posts is 0.222.

18 For example, AstraZeneca has a group and a U.S.-specific account.

19 Crimson Hexagon allows only one year of data for the number of followers on YouTube and Instagram, which is why we do not measure user following for these two platforms.

20 Online Appendix B presents an example of tweets related to the earnings announcement for Glencore PLC.

21 Standardised coefficients report results for variables normalised to a mean of zero and unit standard deviation.

22 For dividend signalling, see Grullon et al. (Citation2005) for the U.S. evidence, Conroy et al. (Citation2000) and Fukuda (Citation2000) for evidence for Japan, Chen et al. (Citation2002) for China, Abeyratna and Power (Citation2002) for the U.K, and Andres et al. (Citation2013) for Germany. Allen and Michaely (Citation2003) review the dividend signalling literature and conclude, ‘[T]he overall accumulated evidence does not support the assertion that dividend changes convey information about future earnings.’ For stock repurchases signalling, Grullon and Michaely (Citation2004, p. 652) ‘find no evidence that repurchasing firms experience an improvement in future profitability relative to their peer firms. In fact, some of the performance measures indicate that repurchasing firms underperform their peers. We also find that analysts revise their expectations downward after the announcement of a share.’ Studies also link share repurchases to earnings management to increase reported EPS (Hribar et al., Citation2006), avoid EPS declines (Myers et al., Citation2007) and sustain EPS growth (Bens et al., Citation2003), which further questions the usefulness of repurchases for signalling earnings persistence.

23 For completeness, Online Appendix C presents tests for Equation (1) that includes only the indicator for whether a firm posts earnings results on Twitter and its interaction with the earnings surprise. We present these results to validate the U.S. evidence that posts on Twitter related to earnings announcements associate, on average, with incremental price reactions.

24 We estimate the regression with an interaction term between retail ownership and whether a firm posts earnings results on Twitter, rather than with the content of tweets, as the latter would produce too many variables (additional 24 variables on top of existing 23 variables) for too few degrees of freedom, which would undermine the reliability of the estimates.

References

- Aboody, D., & Kasznik, R. (2000). CEO stock options awards and the timing of corporate voluntary disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 29(1), 73–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(00)00014-8

- Abeyratna, G., & Power, D. (2002). The post-announcement performance of dividend-changing companies: The dividend-signalling hypothesis revisited. Accounting and Finance, 42, 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-629X.00071

- Abraham, S., & Cox, P. (2007). Analysing the determinants of narrative risk information in UK FTSE 100 annual reports. The British Accounting Review, 39(3), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2007.06.002

- Allen, F., & Michaely, R. (2003). Payout policy. In G. Constantinides, M. Harris, & R. Stulz (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of finance: Corporate finance (Vol. 1A, pp. 337–430). North Holland.

- Altinkilic, O., & Hansen, R. (2009). On the information role of stock recommendation revisions. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 48(1), 17–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.04.005

- Andres, C., Betzer, A., van den Bongard, I., Haesner, C., & Theissen, E. (2013). The information content of dividend surprises: Evidence from Germany. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 40, 620–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12036

- Asay, H., Libby, R., & Rennekamp, K. (2018). Do features that associate managers with a message magnify investors’ reactions to narrative disclosures? Accounting, Organization, and Society, 68, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2018.02.003

- Ball, R., & Brown, P. (1968). An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbers. Journal of Accounting Research, 6(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490232

- Barber, B., & Odean, T. (2008). All that glitters: The effect of attention on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Review of Financial Studies, 21(2), 785–818. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhm079

- Barber, B., Odean, T., & Zhu, N. (2009). Do retail trades move markets? Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 151–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn035

- Bartov, E., Mohanram, P., & Faurel, L. (2018). Can Twitter help predict firm-level earnings and stock returns? Accounting Review, 93(3), 25–57. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51865

- Beaver, W. (1968). The information content of annual earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting Research, 6, 67–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490070

- Ben-Rephael, A., Da, Z., & Israelsen, R. (2017). It depends on where You search: Institutional investor attention and underreaction to news. Review of Financial Studies, 30(9), 3009–3047. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhx031

- Bena, J., Ferreira, M., Matos, P., & Pires, P. (2017). Are foreign investors locusts? The long-term effects of foreign institutional ownership. Journal of Financial Economics, 126(1), 122–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2017.07.005

- Bens, D. A., Nagar, V., Skinner, D. J., & Wong, F. H. (2003). Employee stock options, EPS dilution, and stock repurchases. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 36(1–3), 51–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2003.10.006

- Bhagwat, V., & Burch, T. (2016). Pump It Up? Tweeting to Manage Investor Attention to Earnings News. Working paper, George Washington University.

- Blankespoor, E., Miller, G., & White, H. (2014). The role of dissemination in market liquidity: Evidence from firms’ use of twitter. Accounting Review, 89(1), 79–112. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50576

- Bollen, J., Mao, H., & Zeng, X. (2011). Twitter mood predicts the stock market. Journal of Computational Science, 2(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2010.12.007

- Cadbury, A. (1992). Cadbury report of the committee on the financial aspects of corporate governance. Gee & Co.

- Cameron, A., & Trivedi, P. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press.

- Ceron, A., Curini, L., Iacus, S., & Porro, G. (2014). Every tweet counts? How sentiment analysis of social media can improve our knowledge of citizens’ political preferences with an application to Italy and France. New Media & Society, 16(2), 340–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813480466

- Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8(4), 293–332. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci0804_2

- Chen, G., Firth, M., & Gao, N. (2002). The information content of concurrently announced earnings, cash dividends, and stock dividends: An investigation of the Chinese stock market. Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting, 13, 101-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-646X.00080

- Collins, D., Li, O., & Xie, H. (2009). What drives the increased informativeness of earnings announcements over time? Review of Accounting Studies, 14(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-007-9055-y

- Conroy, R., Eades, K., & Harris, R. (2000). A test of the relative pricing effects of dividends and earnings: Evidence from simultaneous announcements in Japan. The Journal of Finance, 55, 1199–1227.

- Cowen, A., Groysberg, B., & Healy, P. (2006). Which types of analyst firms are more optimistic? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 41(1-2), 119–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2005.09.001