Medically unexplained syndromes (MUS) are defined as persistent bodily symptoms with functional disability but no explanatory pathology. They are highly prevalent in both primary and secondary care. In a meta-analysis of medically unexplained symptoms (not syndromes) in primary care, the percentage of patients complaining of at least one medically unexplained symptom ranged from 40.2 (95% CI 0.9–79.4%; I2 = 98%) to 49% (95% CI 18–79.8%, I2 = 98%) (Haller et al., Citation2015). MUS are associated with high levels of distress and do not respond easily to reassurance and simple explanation (Barsky & Borus, Citation1999). They are seen in all medical specialties. Fibromyalgia (FM) is frequently seen in rheumatology, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in gastroenterology, non-cardiac chest pain in cardiology, chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) in infectious diseases, non-cardiac chest pain and functional palpitations in cardiology, hyperventilation syndrome in respiratory medicine, tension headache in neurology and multiple chemical sensitivity in allergy. These syndromes have mostly been studied in isolation. However, research has observed extensive symptom overlap with more than half of patients with one MUS condition fulfilling diagnostic criteria for at least one other MUS condition (Nimnuan et al., Citation2001). For this reason, Wessely et al. (Citation1999) suggested advantages to redefining MUS as one syndrome. Fink & Schroder (Citation2010) advocated a new over-arching term, “bodily distress syndrome”, to encompass all the different MUS. They submit that there is now substantial evidence that MUS conditions are not clearly distinct disease entities but rather a common phenomenon with different subtypes. They describe similarities in diagnostic criteria, aetiology, pathophysiological, neurobiology, psychological mechanisms, patient characteristics and treatment response. Some years earlier Yunus (Citation2007) had suggested the generic term “central sensitivity syndrome” which suggests that the common mechanism underlying various MUS is central sensitisation which is the hyper-excitement of neurons in the central nervous system.

However, this “lumping” hypothesis triggered much debate due to criticisms that overlap is not present between all the MUS. For instance, there is little symptomatic overlap between IBS and FM. Furthermore, the pathophysiology is not consistent across syndromes in that there is hyperactivity of corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in FM but hypoactivity in CFS (Neeck & Crofford, Citation2000). From a cognitive behavioural perspective unhelpful beliefs and behaviours may differ markedly from one syndrome to another.

The study of MUS often attracts debate and sometimes controversy. Even the label MUS comes under fire. Persistent physical symptoms (PPS) is a new patient-centred term that refers to MUS. For several reasons, we prefer to use the term PPS. Firstly, two surveys of different populations preferred the term. One group consisted of healthy subjects (Marks & Hunter, Citation2015) and the other group involved patients with CFS (Picariello et al., Citation2015). People found the term more acceptable as it avoids mind–body dualism and has cross-cultural relevance. Secondly, it includes symptoms associated with medically diagnosed long-term conditions such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis which may present co-morbidly with MUS. Thirdly, it also concurs with changes in the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistics Manual (DSM-5). The DSM-5 has consolidated previous terms including somatization disorder, conversion disorder, hypochondriasis into a new diagnostic term and somatic symptom disorder (SDD). This refers to persistent (>6 months) and clinically significant somatic complaints accompanied by excessive and disproportionate health-related thoughts, feelings and behaviours regarding the symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). We will use the new term PPS to refer to MUS but continue to use the term MUS when referring to the work of other authors who have used this term.

The development and delivery of effective treatments for PPS is important for patients, health professionals, the wider healthcare system and the economy. There is an increasing demand to ensure that this is achieved efficiently in an “over-stretched” healthcare system. Prevalence of MUS in secondary care is ∼50% and healthcare costs are twice those of other patients (Barsky et al., Citation2005). Initiatives to meet this demand are being commissioned and developed. The improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) programme is expanding to treat PPS and long-term conditions (LTC’s) to increase access in primary care (McCrae et al., Citation2015).

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for PPS has traditionally focussed on developing specific treatment programmes for conditions such as CFS and IBS. This approach is supported by a good evidence base. CBT has demonstrated both short-term and long-term efficacy with small effect sizes for MUS (Van Dessel et al., Citation2014) yet larger treatment effects are seen in specific syndromes such as CFS (White et al., Citation2011) and IBS (Altayar et al., Citation2015).

Given the overlap between syndromes and the fact that the stability of diagnoses within individuals is low it is highly probable that a number of core transdiagnostic aetiological factors underlie the disorders and that common processes perpetuate the symptoms and disability. We and others have identified cognitive and behavioural responses to symptoms that are common across MUS conditions. For example, such cognitive and behavioural responses include avoidance of activity and focussing on symptoms (Deary et al., Citation2007; Spence & Moss-Morris, Citation2007). In both IBS and CFS, participants hold significantly more beliefs about the unacceptability of emotions compared to healthy controls (Bowers & Wroe, Citation2015; Rimes & Chalder, Citation2010).

The transdiagnostic approach while addressing common processes is flexible enough to address issues specific to the disorder. For example, research has identified different aetiological pathways for the development of CFS and IBS. CFS is more likely to develop following infection with glandular fever and IBS following campylobacter infection. Depression has been found to be a greater risk factor for CFS yet stress, anxiety and perfectionism are important predictors for IBS (Moss-Morris & Spence, Citation2006; Spence & Moss-Morris, Citation2007). While IBS and CFS share an overall transdiagnostic response of “avoidance behaviour” they sometimes differ in the type of avoidance. IBS patients may respond to their symptoms with “embarrassment-avoidance”. More specifically they may avoid social situations due to fear of embarrassment or fear of having an accident. However, CFS patients often report that they avoid activity or exercise in response to the symptom of fatigue due to fear of exacerbating it.

Co-morbidity of disorders and common processes are also observed in mental disorders. Transdiagnostic approaches and unified treatment protocols for mental disorders such as anxiety, depression and eating disorders have been developed to address this (Barlow et al., Citation2004; Fairburn et al., Citation2003; Kring & Sloan, Citation2010). They focus on identifying the core and common maladaptive temperamental, psychological, cognitive, emotional, interpersonal and behavioural processes that underlie a range of diagnostic presentations and target these in treatment (Newby et al., Citation2015). For example, there is evidence of mechanisms that link the process of rumination to both depression and anxiety. In depression, rumination exacerbates low mood, negative thoughts about the past, present and future and interferes with problem solving. Of course problem solving is the very thing that may lead to the behavioural resolution of problems that causes or perpetuates depression. The same mechanisms have also been found to maintain anxiety but cognition is usually focussed on future threat rather than the past (Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, Citation2011).

There is also a growing evidence base for transdiagnostic approaches for mental disorders. In their systematic review and meta-analysis, (Newby et al., Citation2015) concluded that transdiagnostic approaches are as effective as disorder specific treatments for treating anxiety and may be superior for reducing depression. Similarly, Norton & Barrera (Citation2012) observed treatment equivalence between disorder specific and transdiagnostic treatments for anxiety in a non-inferiority randomised controlled trial (RCT).

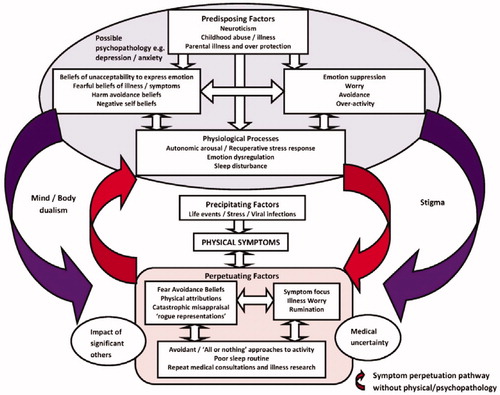

We have developed a transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural approach for PPS which can also be used for long-term conditions. We anticipate that the adapted transdiagnostic approach may address the need for efficiency while maintaining the efficacy of larger effects seen in specific condition treatment programmes. Our transdiagnostic approach for PPS is guided by the use of a transdiagnostic meta-model (). It integrates predisposing and precipitating aetiological factors with perpetuating factors. As with most cognitive behavioural models, cognitive and behavioural responses are key. However, emotional responses or reactions and their corresponding physiological interactions are also considered in the maintenance of symptoms (Brown, Citation2004; Deary et al., Citation2007; Yunus, Citation2007). Two explanatory pathways include and exclude pre-morbid physical pathology or psychopathology. Acute and recuperative stress responses are emphasised as are key physiological processes that variably interact with other factors to perpetuate symptoms. In terms of how this maps onto the treatment process an assessment of these factors and processes with each individual influences the development of a formulation. This is shared with the patient to provide explanation for their symptoms and disability and guides the selection of interventions and strategies for treatment. summarises the transdiagnostic processes with corresponding interventions and strategies that have informed the design of the approach.

Table 1. Adapted transdiagnostic interventions.

It is important that the transdiagnostic approach is flexible enough to accommodate specific responses associated with different symptom clusters whilst focusing on key factors which are thought to perpetuate the problem. In order to bring some clarity to this complex issue, we have organised factors and processes within a matrix framework. The Research Domain Criteria (RDoc) initiative provides a template for the development of such a framework (Morris & Cuthbert, Citation2012). It uses a dimensional transdiagnostic approach to capture processes (e.g. cognitive, affective, arousal) that are common across disorders. Adapting the framework we propose a two-dimensional hierarchical matrix for PPS. Columns contain the superordinate processes: symptoms; physiological; emotional; cognitive, behavioural and social processes. Rows consist of both broad transdiagnostic processes as well as processes specific to conditions or symptom clusters which are potential targets (). Fatigue is illustrated as a transdiagnostic symptom and will provide a model for the development of the rest of the matrix.

Table 2. Proposed matrix: illustrated with fatigue as a transdiagnostic symptom.

Ideally, the matrix evolves as research identifies and develops evidence for additional factors and processes to populate the matrix cells. The strength of evidence for each factor or process could be visually represented to map strong, medium and weak evidence, creating a third dimension. In addition, moderating factors that determine the route from transdiagnostic to specific could form a network of links between factors and processes. These are described as divergent trajectories in Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins (Citation2011) heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models. They describe how a transdiagnostic risk factor results in different disorders in different people or different disorders within the same person over time. Ideally these transdiagnostic mechanisms should be assessed frequently during the course of treatment so that the process of change can be assessed. In RCTs measuring both transdiagnostic and specific mediators would allow a more robust evaluation of their importance (Windgassen et al., Citation2016).

The development of the matrix could provide a useful clinical tool to assist treatment formulations and for guiding clinicians in their treatment of PPS. It may also be used for the training and professional development of therapists.

The high prevalence and complexity of PPS with increased access to treatment in new and developing primary care services demands a treatment approach that is effective and also “efficient” with relative ease of dissemination across the NHS. Transdiagnostic approaches have the potential to provide effective treatment across a range of conditions that often present co-morbidly. Overlap of symptoms and co-morbidity in PPS as well as commonality in cognitive and behavioural responses suggests that a transdiagnostic approach may be suitable. We argue that a transdiagnostic approach needs to be flexible enough to accommodate specific responses peculiar to certain conditions. We are currently carrying out a RCT to test the efficacy of such an approach in PPS.

Declaration of interest

Overcoming Chronic Fatigue by Mary Burgess and Trudie Chalder, Robinson Publishing Ltd.

Overcoming Chronic Fatigue in Young People: A cognitive behavioural self help guide by Katherine Rimes and Trudie Chalder, Routledge.

Coping with Chronic Fatigue: Overcoming Common problems by Trudie Chalder, Sheldon Press.

Acknowledgements

T.C. is in receipt of funding from Guys and St Thomas Charity and acknowledges financial support from the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health award from South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) and the Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College London.

References

- Altayar O, Sharma V, Prokop L, et al. (2015). Psychological therapies in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract, 2015, 549308

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

- Barlow D, Allen L, Choate M. (2004). Towards a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behav Ther, 35, 205–30

- Barsky A, Borus J. (1999). Functional somatic syndromes. Ann Int Med, 130, 910–21

- Barsky A, Orav J, Bates D. (2005). Somatization increases medical utilization and costs independent of psychiatric and medical comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 62, 903–10

- Bowers H, Wroe A. (2015). Beliefs about emotions mediate the relationship between emotional suppression and quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome. J Mental Health, 25, 154–8

- Brown R. (2004). Psychological mechanisms of medically unexplained symptoms: an integrative conceptual model. Psychol Bull, 130, 793–812

- Deary V, Chalder T, Sharpe M. (2007). The cognitive behavioural model of medically unexplained symptoms: a theoretical and empirical review. Clin Psychol Rev, 27, 781–97

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther, 41, 509–28

- Fink P, Schroder A. (2010). One single diagnosis, bodily distress syndrome, succeeded to capture 10 diagnostic categories of functional somatic syndromes and somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res, 68, 415–26

- Haller H, Cramer H, Romy L, Gustav D. (2015). Somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. Dtch Arztebl Int, 112, 279–87

- Kring A, Sloan D. (2010). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: a transdiagnostic approach to aetiology and treatment. New York, NY: Guildford Press

- Marks E, Hunter S. (2015). Medically unexplained symptoms: an acceptable term? Br J Pain, 9, 109–14

- McCrae N, Correa A, Chan T, et al. (2015). Long term conditions and mediaccly unexplained symptoms: feasibility of cognitive behavioural interventions within the improving access to Psychological Therapies Programme. J Mental Health, 24, 379–84

- Morris S, Cuthbert B. (2012). Research domain criteria: cognitive systems, neural circuits and dimensions of behaviour. Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 14, 29–37

- Moss-Morris R, Spence M. (2006). To “lump” or to “split” the functional somatic syndromes: can infectious and emotional risk factors differentiate between the onset of chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome? Psychosom Med, 68, 463–9

- Neeck G, Crofford L. (2000). Neuroendocrine perturbations in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am, 26, 989–1002

- Newby J, McKinnon A, Kuyken W, et al. (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of transdiagnostic psychological treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood. Clin Psychol Rev, 40, 91–110

- Nimnuan C, Hotopf M, Wessely S. (2001). Medically unexplained symptoms: an epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosom Res, 51, 361–7

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Watkins E. (2011). A heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology: explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspect Psychol Sci, 6, 589–609

- Norton P, Barrera T. (2012). Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis specific CBT for anxiety disorders: a preliminary randomised control non-inferiority trial. Depress Anxiety, 29, 874–82

- Picariello F, Ali S, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. (2015). The most popular terms for medically unexplained symptoms: the views of CFS patients. J Psychosom Res, 78, 420–6

- Rimes KA, Chalder T. (2010). The beliefs about emotions scale: validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. J Psychosom Res, 68, 285–92

- Spence M, Moss-Morris R. (2007). The cognitive behavioural model of irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective investigation of patients with gastroenteritis. Gut, 56, 1066–1971

- Van Dessel N, Den Boeft M, Van der Wouden J, et al. (2014). Non-pharmacological interventions for somatoform disorders and medically unexplained physical symptoms (MUPS) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, CD011142. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011142.pub2

- Wessely S, Nimnuan C, Sharpe M. (1999). Functional somatic syndromes: one or many? Lancet, 354, 936–9

- White P, Goldsmith K, Johnson A, et al. (2011). Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet, 377, 823–36

- Windgassen S, Goldsmith K, Moss-Morris R, Chalder T. (2016). Establishing how psychological therapies work: The importance of mediation analysis. J Ment Health, 25, 93–9

- Yunus M. (2007). Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Sem Arthritis Rheum, 36, 339–56