Abstract

Background

Numerous studies have explored the concept of ‘professionalism’ in medicine, yet little attention has been paid to the concept in a mental health services context.

Aims

This study sought to determine how the lived experience of patients, carers and healthcare professionals in mental health services align with medically defined, generic, professionalism standards.

Method

Interviews and focus groups were conducted with patients, carers, nurses, occupational therapists, psychiatrists and psychologists. A framework analysis approach was used to analyse the data, based on the ‘Improving Selection to the Foundation Programmes’ Professional Attributes Framework.

Results

Fifty-six individuals participated. Data aligned to all nine attributes of the Professional Attributes Framework, however the expectations within each attribute varied from that originally cited. A tenth attribute was devised during the process of analysis; Working with Carers. This attribute acknowledges the need to liaise with, and support carers in mental health services. Situational examples included both online and offline behaviours and the topic of ‘black humour’ emerged.

Conclusions

Compared to a conventional medical definition of professionalism, additional themes and differing emphases were observed for mental health and learning disability services. These findings should be used to inform the teaching and evaluation of professionalism, especially for staff pursuing mental health service careers.

Introduction

What is Professionalism?

Professionalism is a multidimensional concept (van de Camp et al., Citation2004). Definitions have tautologically included “upholding professional values, exhibiting professional behaviours or demonstrating professional attitudes” (Aguilar et al., Citation2011). The context-dependent nature of professionalism has previously been highlighted (Aylott et al., Citation2019; Rees & Knight, Citation2007). Yet, whilst many studies have sought to explore ‘professionalism’ in medicine, there is a dearth of studies focusing on the concept in mental health services (MHS; Aylott et al., Citation2019).

Mental health problems are, reportedly, the single largest source of burden of disease in the UK; nonetheless, services are in receipt of inadequate funding, an understaffed workforce, and insufficient training (British Medical Association, Citation2017). When services are not resourced adequately, the likelihood of unprofessional behaviour may increase.

Each healthcare area has their own regulatory frameworks, as do each of the professions; nonetheless, there are nuances to MHS that warrant further exploration regarding the concept of professionalism. For example, patients may experience impaired mental capacity, rendering them less autonomous and vulnerable to exploitation. This adds complexity to the ethical and professional issues that face mental health professionals.

Professionalism in mental health services

A recent systematic review provided an operational definition of professionalism for MHS (Aylott et al., Citation2019). Practitioners are described as embodiments of their profession, possessing intrapersonal, interpersonal and working professionalism. A scarcity of patient presence was observed in the literature. Therefore, this study explored the perceptions of professionals, patients and carers regarding the professional attitudes and behaviours experienced in MHS. Having reviewed the literature, the authors determined that the findings would be best analysed against the professional attributes framework (PAF), developed as part of the ‘improving selection to the foundation programme’ project, commissioned by the Medical Schools Council (Citation2011). This was considered a suitable framework, as most of the professionalism literature regarding MHS focuses on psychiatry (a medical profession). The PAF also helped inform the development of the topic guide. The research questions were: (1) what are patients, carers and professionals experiences of, and perceptions of professionalism in a mental health setting? (2) how does this experience align, if at all, with medically defined, generic, professional standards and attributes?

Methods

Ethics

All procedures were approved by the Health Sciences Research Governance Committee at the University of York and a favourable ethical opinion was obtained from London–Camden & Kings Cross Research Ethics Committee (18/LO/0630).

Design

Focus groups were undertaken with carers and professionals. Individual semi-structured interviews were undertaken with patients, as the ethics committee expressed that this approach would raise fewer ethical concerns than the use of focus groups.

Recruitment

The study was advertised in an NHS Trust using their electronic news bulletin and intranet. Emails were sent via professional leads, and flyers were placed in community centres, and distributed via a patient and public newsletter. A carers’ network was also approached.

Participation was voluntary; however, patients and carers were offered a £20 gift voucher to reimburse them for their time and travel. Purposive sampling was used. Too much heterogeneity within each focus group could inhibit the discussion (Freeman, Citation2006); thus, separate focus groups were conducted with psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, occupational therapists (OTs) and carers. Patients that had accessed MHS, within the last two years, participated in one to one interviews. Having had the objective of the study explained, written consent was obtained from all participants.

Data Collection

Interview questions were established based on the critical incident technique (Flanagan, Citation1954) and prior research on professionalism (Burford et al., Citation2014; Medical Schools Council, Citation2011). The schedule was piloted, confirming that the questions and prompts were fit for purpose (see ). The lead author facilitated all interviews and focus groups; four focus groups were co-facilitated by a co-author. Interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Member checking was used during focus groups and interviews to confirm the authors’ interpretation of the data.

Table 1. Topic guide used to generate discussion on professionalism in mental health services.

Data analysis

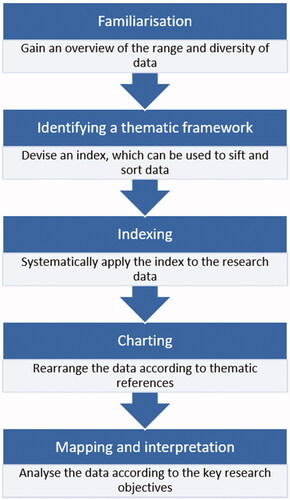

Data were managed using NVivo. As the researchers had apriori themes in mind, framework analysis (Ritchie et al., Citation2003; Ritchie & Spencer, Citation1994) was employed (see ). During the familiarisation stage, open coding was utilised; it was determined that the data fit the PAF (Medical Schools Council, Citation2011). Data were subsequently indexed against all nine attributes of the PAF. Codes and subsequent themes were created to portray an accurate description of the data.

Figure 1. Stages of Framework Analysis (adapted from Ritchie & Spencer, Citation1994).

Analysis was predominantly performed by two authors (LA, SB). An iterative process was used by SB to review a transcript against the codes and themes created by LA. Data were discussed, and codes amended through negotiation, resulting in themes and subthemes; hereby referred to as the professional attributes and expectations. To improve the validity of the analysis, all authors reviewed a sample of coding.

Results

In total, 6 focus groups and 13 interviews were conducted between August 2018 and January 2019. Participants included 18 men, 36 women, and 2 individuals that referred to their gender as ‘other’. The total sample was 56, including 7 psychiatrists, 7 psychologists, 10 nurses, 10 OTs, 7 carers, and 15 patients. Ages ranged from 21 to 86 years. Professionals worked in a range of specialties, across inpatient and community settings.

Data aligned to all nine attributes, however the expectations within each attribute varied to that originally cited. A tenth attribute was devised during analysis; ‘Working with Carers’. The ten professional attributes, which became the coding framework are described in turn here, with illustrative quotes provided. Each attribute includes a brief description to reflect its overall nature. As each attribute has multiple expectations, it is not possible to describe each one; an overview of this structure is reported within .

Table 2. Professional attributes and expectations of staff working in mental health services (adapted from CitationMedical Schools Council, 2011).

Commitment to Professionalism

Individuals should be committed to honouring their profession by adhering to guidelines and challenging poor practice. Professionals must have integrity and be a responsible practitioner

Challenging poor practice can make professionals unpopular, but they have “a duty” to challenge. Social media presented issues, specifically with regards to online dating and platforms such as Facebook, but the work and personal life dichotomy was made clear.

…it’s about having clear boundaries as well isn’t it, so I’ve got a Twitter account for purely professional stuff … but then Facebook, I have strict settings on that… (OT)

I am a single person, but I have got an issue for example with internet dating as well because of that status you have got [as a psychiatrist], I don’t do it…. I think there are some unwritten rules you are supposed to follow. (Psychiatrist)

Coping with Pressure

Practitioners must utilise their clinical judgement, particularly in times of uncertainty and ambiguity. Professionals must have resilience and be able to de-escalate situations when others are experiencing distress

Participants were aware of the need for professionals to separate themselves from the work that they do, to not let this impinge upon their own wellbeing.

Professionalism for me is walking out of here and onto the next thing with a fresh mind, a fresh view…you have got to detach. (Patient)

Acknowledging the need for de-escalation, a carer highlighted that some staff de-escalate situations better than others.

I have seen physical restraint used detrimentally to the point even when people were saying ‘oh should we do your hair’ while they are restraining this person on the floor, whereas other staff would be able to talk to that person and dissolve the situation (Carer)

Humour was noted as a means of making light, defusing stress and normalising situations. An example was provided with respect to a suicidal patient who frequently swallowed a specific form of vegetation. After numerous incidents within a shift a staff member made a blasé remark, ‘I can’t wait for spring, when there are no [vegetation] around.’ Humour was viewed negatively in certain circumstances, such as when one is critical of a patient.

Effective Communication

Practitioners must communicate effectively, using both verbal and non-verbal communication. Professionals should have the ability to build rapport with patients, and validate the thoughts and feelings of others

Banter can be used to build rapport; however, it was recognised that this can go wrong very quickly, particularly “if someone feels targeted, especially where they’ve got trauma histories, where they’ve been humiliated, bullied, and all the rest.” (Psychologist)

Learning and Development

Practitioners must possess the appropriate knowledge and skills for their role, utilising professional development opportunities. Professionals should accept feedback and utilise supervision accordingly

Supervision is a safe forum for discussing the difficulties one may face, particularly when struggling with patients.

You could say the same thing, but in different contexts. And some are professional and some are not professional. (Psychologist)

Organisation and Planning

Practitioners must maintain accurate records and read case notes attentively. Professionals must effectively manage limited resources, and their time accordingly

One professional suggested that documentation was a waste of clinician time, whereas a patient commented that sometimes this must take precedence.

All the notes we keep really are litigation proof that’s all it is you know (Nurse)

The planning of my care could depend on that, … If it isn’t recorded properly I might lose out on the appropriate care. (Patient)

Patient Focus

Practitioners must possess qualities that enable them to build therapeutic relationships with patients, such as altruism and humility. Professionals, also, must maintain an appropriate professional distance and not impose their own values on patients, delivering person-centered care

A service user indicated that, in some cases, respect is not always evident. This finding was supported by an OT’s comments.

Just the way someone speaks to you honest they speak to you like you’re on their shoe. (Patient)

when people open doors without knocking, or open curtains without getting permission… It’s low-grade stuff, but it’s poor practice. (OT)

One patient discussed their anxiety at making telephone calls; noting that their nurse challenged them to do this, they felt they should be challenged in this way.

It’s finding … something I need to do or want to do and pushing me to do that, as opposed to pushing me to do whatever they think most people who are depressed or hear voices or whatever do. (Patient)

Problem Solving

Practitioners must be able to reason with abstract information. Professionals also must understand problems from a wider perspective, having the ability to adapt their practice

Patients experience mental illness differently; professionals must therefore conceptualise with abstract information.

The word schizophrenia does not describe people with schizophrenia, you know everybody’s different and I think you have to … think outside the box a bit in mental health that you maybe don’t have to do so much in sort of medical care. (Nurse)

Self-Awareness and Insight

Practitioners must possess self-awareness and acknowledge the limits to their competence. It is appropriate to disclose some information about self, but professionals must recognise and maintain boundaries when doing so

Self-disclosure can break down some of the boundaries in a staff–patient relationship. However, the disclosure must be appropriate for each patient.

It also seems a bit of a balance sometimes because you expect a patient to share so much of themselves… And then you kind of go, but I won’t tell you anything about me. (Psychologist)

Professionals must reflect-in-action.

I’ve seen a fair few emails that maybe come across as disrespectful and unprofessional, because they’re emotive emails about a topic that people have strong opinions on… I think professionalism is about taking a step back and thinking right, I’m quite annoyed about this, maybe I should send this later or ask someone else to look over it. (Psychologist)

Working Effectively as Part of a Team

Practitioners must work alongside colleagues effectively, acknowledging people’s strengths and capabilities. Professionals must also be a positive role model

Discussions arose regarding negative role modelling and the detrimental impact this can have on students and newly qualified professionals.

When they’re qualified, you can’t go home and have a cup of tea and I think that sometimes with students, … we set the wrong examples. (OT)

Working with Carers

Professionals must involve carers where possible, whilst adhering to the bounds of confidentiality. Carers generally want to be involved and should feel supported in their role

The study found that professionals were perceived to hide behind policy. Carers want to be supported, yet that support is not always available.

confidentiality, he is using that against me because all he is sees is a carer … he is not making that connection between if he supports me professionally as a carer, he is also supporting my son in the future (Carer)

Carers feel left to the wayside; professionals should work with carers, where possible, to improve patient care.

the majority of carers want to be involved and want to help and get very fed up of being left in a corner. (Carer)

Discussion

Professionalism is widely cited as the basis of a social contract between professions and society (see Aylott et al., Citation2019). With regards to medicine, physicians can expect their core activities to be protected and governed by licensing laws (Cruess, Citation2006); which permit members to practice. Professions are permitted and expected to self-regulate (Cruess, Citation2006). However, in return, the views of the patients they serve, who place their trust in the profession, must be incorporated (Irvine, Citation1997). Indeed, the social contract must be regularly renegotiated (Bhugra, Citation2008; Bhugra & Gupta, 2010).

The study sought to explore the professional attributes desired within mental health services. The authors hoped to determine how this experience aligned to medically defined, generic, professional standards and attributes.

Main Findings

The findings demonstrate that patients’, carers’ and professionals’ views on professionalism in MHS mostly align to medically defined, generic, professional standards and attributes; however, there are differing emphases, and carers must be factored into the equation. When working with clients exhibiting challenging behaviours, it is important that one maintains self-awareness and insight to maintain a neutral, professional stance with patients. Effective communication is paramount across settings, yet this is more challenging in MHS, where patients may be severely unwell and lack mental capacity. As highlighted previously, the use of banter can go extremely badly when used with patients that have trauma histories.

Whilst carers are not unique to mental health settings, they often play a key role in the care of many patients with mental health problems and working collaboratively with them is an essential part of modern service delivery (Cleary et al., Citation2006); nevertheless, the findings demonstrate that all too often, carers are feeling left to the wayside and unsupported in their role. Given that a patient’s mental capacity is often impaired in MHS, carers fill a vital role, “if you are really doing the best for your patient, you have to be able to look at their social network, particularly in mental health” (Carer).

Comparisons with the Existing Literature

As demonstrated previously (Green et al., Citation2009), the study found that patients and professionals do not always place the same regard on certain professional behaviours; there were differing views between a patient and professional regarding documentation.

In comparison to the medically derived PAF, the study identified a tenth attribute; working with carers. The importance of carers being involved in the treatment of patients with mental health problems has previously been reported in the Triangle of Care guidance document (Worthington et al., Citation2013). Nevertheless, carers report being shunned by professionals, who won't even talk to them, because “the patient has not given consent for the carer to be involved” (Carer). This study adds further evidence to support the findings of Cleary et al. (Citation2005); over 50% of carers reported that information, such as that regarding medication, illnesses and community resources is not provided to them.

Similarities are observed between these findings and the definition of professionalism proposed by Aylott et al. (Citation2019). The attribute ‘Commitment to Professionalism’ is congruous with ‘Intrapersonal Professionalism’; ‘Patient Focus’ and other attributes align to the concept of ‘Interpersonal Professionalism’; and ‘Coping with Pressure’ is harmonious with ‘Working Professionalism’–the ability to form judgements and act accordingly, thinking critically and using reflection in action.

The importance of contextual factors and situational judgement has previously been reported by Burford et al. (Citation2014). Whilst their study was not conducted in MHS, their findings resonate with the current study; as a psychologist highlighted, “You could say the same thing, but in different contexts. And some are professional and some are not professional”. Similarly, the use of humour and self-disclosure is dependent on contextual, patient related factors.

Humour is viewed as acceptable amongst professionals, but professionals must be aware of their audience, and they must use humour in a safe setting. Camaraderie and banter have been reported on in a study with medical undergraduates, whereby “camaraderie was condoned as a legitimate means by which medics can diffuse stress” (p.819; Finn et al., Citation2010). Nearly a decade later, the same issues still present. This is a controversial issue, as professionals argue that humour is vital for their wellbeing, but many alluded to its context dependence and sensitivity.

The need to be a positive role model was highlighted, echoing that previously reported with the ‘hidden curriculum’; there are discrepancies between what students learn in textbooks and classrooms versus what they pick up on placement (Hafferty & Franks, Citation1994). Concerningly, the observation of and participation in unethical conduct has been shown to result in ethical erosion overtime (Satterwhite et al., Citation2000). Problematic behaviour during training has also been found to predict disciplinary action in later clinical practice (Papadakis et al., Citation2004).

In many ways, professionalism is more noticeable by its absence than its presence. Following their evaluation of a Situational Judgement Test measuring integrity, de Leng et al. (Citation2018) suggested that there may be a greater consensus regarding what is considered inappropriate, as opposed to appropriate behaviour. Certainly, in the current study, participants frequently referred to professionalism as about ‘what not to do’, as opposed to more optimal behaviours. Healthcare is becoming increasingly bureaucratic and administrative, and in a litigious society, professions are more regulated than ever. Whilst participants seemed open about their professional and unprofessional encounters, some behaviours may not have been disclosed. This is in keeping with what John McLachlan refers to as ‘Pious Platitudes’ about professionalism; that practitioners, when asked to define professionalism, may respond with what they think they ought to say, rather than with what they have actually observed (Monrouxe & Rees, Citation2017).

Interpretation of findings

Various medical specialties suggest that refinements to the concept of professionalism are needed for this to be pertinent to their practice (Woodruff et al., Citation2008). For instance, it has been argued that the Physician Charter does not take account of many elements of surgery practice, that pose specific ethical and professional questions for their specialty (Jones et al., Citation2006). Given the nature of MHS, it is not surprising that the study identified a tenth attribute–working with carers. Carers were not directly involved in the development of the PAF. However, there are nuances in MHS that are not present in other specialties; detained patients lose their patient autonomy–one of the three fundamental principles of medical professionalism (Project of the ABIM Foundation, 2002); and patients are vulnerable (Department of Health, Citation2000, updated in 2015), often relying on carers to protect and advocate for them. As stated in the Triangle of Care, “Carers are usually the first to be aware of a developing crisis … They are often best placed to notice subtle changes in the person for whom they care, and usually the first to notice the early warning signs of a relapse” (p.7, Worthington et al., Citation2013).

MHS pose many challenges for professionals, as well as professionalism in general. For example, patients may commit suicide, which undoubtedly impacts upon a professional’s own wellbeing. Patients, also, may be criminals, yet the professional has a duty of care and must do their best by the patient. Discussing the ever-increasing challenges, a psychiatrist commented–“isn’t our status because we do, we make good a bad system … I think we are regarded at a level that we are regarded because we don’t let bad things happen”. The current study explored the expectations placed on professionals working in MHS; however, we must acknowledge the requirements of the professions themselves, including a properly funded and value-driven healthcare system (Bhugra, Citation2008; Cruess, Citation2006). The social contract places expectations on patients too, such as ‘a shared responsibility’ for their own health and wellbeing (Bhugra, Citation2008; Cruess, Citation2006); it is important that patients and carers work with professionals, by, for example, returning calls in a timely manner, and turning up to appointments.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study to explore professionalism from the views of patients, carers, and professionals in MHS. The findings are enriched by the opinions of patients and carers; a voice underrepresented in the professionalism literature. Some researchers criticise the combining of interview and focus group data; however, Lambert and Loiselle (Citation2008) describe how the integration of focus group and individual interview data can enhance the trustworthiness of findings. Alike Lambert and Loiselle’s study (Citation2008), not all prompts were used during focus groups to elicit the information. Nonetheless, the topic guide enabled a semi-structured approach and minimised the likelihood of interviewer bias.

The study was conducted in a large NHS Trust and there were geographical variances in where professionals and patients, had trained, worked, and/or received healthcare previously. Professionals worked across a mixture of settings and a number of nationalities were represented; it is thus the opinion of the research team that these findings are transferable to and representative of mental health issues nationally. Acknowledging that the interviewer is an active participant in co-constructing meaning during interviews (Holloway & Galvin, Citation2017), two individuals analysed the data in order to minimise bias. A reflexive approach was taken throughout (Berger, Citation2015).

Implications for policy and practice

To promote collaboration between practitioners and carers, the authors support some recommendations proposed by Lloyd and King (Citation2003); managers must openly ask staff about their involvement with carers during routine review meetings; collaboration should become a key feature of performance appraisals; and staff should receive appropriate training on the topic. The authors recommend that the study findings are used to guide training curricula. Unprofessional behaviours were highlighted during the study. It has previously been demonstrated that approximately a quarter of students found the school environment “not very conducive” or “not at all conducive” to the open discussion of ethical concerns (Satterwhite et al., Citation2000). The authors would like to reiterate the recommendations of Monrouxe et al. (Citation2011); that more sense-making opportunities should be made available to students, under the supervision of clinical educators. The findings may be used to inform the development of assessments for the selection of staff into MHS. In addition, it may be fruitful to integrate these findings into the standards and inspection guides of health care regulators.

Implications for Future Research

The study did not set out, specifically, to identify differences amongst the professions, with regards to the desired professional attributes. Further research could utilise these findings to determine the extent that each profession endorses each attribute. Professionals face many challenges at work and rely on patients to engage with their treatment in order for the practitioner themselves, to fulfil their role. The authors suggest that future research explores the professionalism of patients that use MHS. A greater understanding of the impact that patient behaviour has on the clinical care delivered will facilitate the development of more tailored packages for patients, and more educational interventions for staff. The study demonstrates that professionals need to fulfil expectations across 10 professional attributes in MHS; including working with carers. The authors urge practitioners to support carers and provide a forum for them to air their views. When a patient is in crisis, a carer’s words could be lifesaving.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aguilar, A., Stupans, L., & Scutter, S. (2011). Assessing students’ professionalism: Considering professionalism’s diverging definitions. Education for Health, 24(3), 599. http://www.educationforhealth.net/text.asp?2011/24/3/599/101417

- Aylott, L. M., Tiffin, P. A., Saad, M., Llewellyn, A. R., & Finn, G. M. (2019). Defining professionalism for mental health services: A rapid systematic review. Journal of Mental Health, 28(5), 546–565. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1521933

- Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

- Bhugra, D. (2008). Renewing psychiatry's contract with society. Psychiatric Bulletin, 32(8), 281–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.108.020560

- Bhugra, D., & Gupta, S. (2010). Medical professionalism in psychiatry. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 16(1), 10–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.108.005892

- British Medical Association (2017). Breaking down barriers: The challenge of improving mental health outcomes. British Medical Association. https://www.bma.org.uk/-/media/files/pdfs/collective%20voice/policy%20research/public%20and%20population%20health/mental%20health/breaking-down-barriers-mental-health-briefing-apr2017.pdf?la=en.

- Burford, B., Morrow, G., Rothwell, C., Carter, M., & Illing, J. (2014). Professionalism education should reflect reality: Findings from three health professions. Medical Education, 48(4), 361–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12368

- Cleary, M., Freeman, A., & Walter, G. (2006). Carer participation in mental health service delivery. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 15(3), 189–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2006.00422.x

- Cleary, M., Freeman, A., Hunt, G. E., & Walter, G. (2005). What patients and carers want to know: An exploration of information and resource needs in adult mental health services. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39(6), 507–513. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01611.x

- Cruess, S. R. (2006). Professionalism and medicine’s social contract with society. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 449, 170–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000229275.66570.97

- de Leng, W. E., Stegers-Jager, K. M., Born, M. P., & Themmen, A. P. (2018). Integrity situational judgement test for medical school selection: Judging ‘what to do’ versus ‘what not to do’. Medical Education, 52(4), 427–437. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13498

- Department of Health. (2000). No secrets: Guidance on developing and implementing multi-agency policies and procedures to protect vulnerable adults from abuse. Department of Health. (updated in 2015). Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/194272/No_secrets__guidance_on_developing_and_implementing_multi-agency_policies_and_procedures_to_protect_vulnerable_adults_from_abuse.pdf

- Finn, G., Garner, J., & Sawdon, M. (2010). ‘You're judged all the time!’ Students’ views on professionalism: A multicentre study. Medical Education, 44(8), 814–825. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03743.x

- Flanagan, J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327–358. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/cit-article.pdf

- Freeman, T. (2006). ‘Best practice’ in focus group research: Making sense of different views. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(5), 491–497.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04043.x

- Green, M., Zick, A., & Makoul, G. (2009). Defining professionalism from the perspective of patients, physicians, and nurses. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84(5), 566–573. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819fb7ad

- Hafferty, F. W., & Franks, R. (1994). The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 69(11), 861–871. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001

- Holloway, I., & Galvin, K. (2017). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare (4th ed.). Wiley Blackwell.

- Irvine, D. (1997). The performance of doctors. I: Professionalism and self regulation in a changing world. BMJ, 314(7093), 1540–1540. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7093.1540

- Jones, J. W., McCullough, L. B., & Richman, B. W. (2006). Ethics and professionalism: Do we need yet another surgeons’ charter? Journal of Vascular Surgery, 44(4), 903–906. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2006.07.028

- Lambert, S., & Loiselle, C. (2008). Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(2), 228–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x

- Lloyd, C., & King, R. (2003). Consumer and carer participation in mental health services. Australasian Psychiatry, 11(2), 180–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1039-8562.2003.00537.x

- Medical Schools Council. (2011). Improving selection to the foundation programme: Final Report. https://isfporguk.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/isfp-final-report-appendices.pdf

- Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2017). Healthcare professionalism: Improving practice through reflections on workplace dilemmas. John Wiley & Sons.

- Monrouxe, L. V., Rees, C. E., & Hu, W. (2011). Differences in medical students’ explicit discourses of professionalism: Acting, representing, becoming. Medical Education, 45(6), 585–602. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03878.x

- Papadakis, M. A., Hodgson, C. S., Teherani, A., & Kohatsu, N. D. (2004). Unprofessional behavior in medical school is associated with subsequent disciplinary action by a state medical board. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 79(3), 244–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200403000-00011

- Project of the ABIM Foundation, A. A. F., and European Federation of Internal Medicine. (2002). Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136(3), 243–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012

- Rees, C. E., & Knight, L. V. (2007). The trouble with assessing students’ professionalism: Theoretical insights from sociocognitive psychology. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 82(1), 46–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000249931.85609.05

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. Bryman & R. Burgess (Eds.), Analzing Qualitative Data (pp. 173–194). Routledge.

- Ritchie, J., Spencer, L., & O’Connor, W. (2003). Carrying out qualitative analysis. In J. Ritchie & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. (pp. 219–262). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Satterwhite, R. C., Satterwhite, W. M., & Enarson, C. (2000). An ethical paradox: The effect of unethical conduct on medical students’ values. Journal of Medical Ethics, 26(6), 462–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.26.6.462

- van de Camp, K., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Grol, R., & Bottema, B. (2004). How to conceptualize professionalism: A qualitative study. Medical Teacher, 26(8), 696–702. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590400019518

- Woodruff, J., Angelos, P., & Valaitis, S. (2008). Medical professionalism: One size fits all? Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 51(4), 525–534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.0.0056

- Worthington, A., Rooney, P., & Hannan, R. (2013). The Triangle of Care. Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health in England (2nd ed.). Carers Trust. https://professionals.carers.org/sites/default/files/thetriangleofcare_guidetobestpracticeinmentalhealthcare_england.pdf