Abstract

Background

Although children who are exposed to victimisation (including abuse, neglect, domestic violence and bullying) have an increased risk of later psychopathology and functional impairment, not all go on to develop these outcomes. Risk calculators that generate individualised probabilities of a victimised child developing future psychopathology and poor functioning have the potential to help practitioners identify the most vulnerable children and efficiently target preventive interventions.

Aim

This study explored the views of young people and practitioners regarding the acceptability and feasibility of potentially using a risk calculator to predict victimised children’s individual risk of poor outcomes.

Methods

Young people (n = 6) with lived experience of childhood victimisation took part in two focus groups. Health and social care practitioners (n = 13) were interviewed individually. Focus groups and interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and thematically analysed.

Results

Ten themes were identified, organised according to the three main topics of discussion: (i) identifying risk (risk factors, current practice, accuracy, implementation, response); (ii) protective factors and prevention (individual, environment, preventative intervention); and (iii) communication of research (stakeholders, methods).

Conclusion

Risk calculators have the potential to enhance health and social care practice in the United Kingdom, but we highlight key factors that require consideration for successful implementation.

Introduction

Childhood victimisation, including abuse, neglect, exposure to domestic violence, and bullying by peers, is a pervasive and serious public health concern (Radford et al., Citation2013). Longitudinal studies of the consequences of victimisation suggest that exposed children have poor long-term outcomes. For example, childhood victimisation has been associated with externalising psychopathology including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder and substance use disorders (e.g. Braga et al., Citation2017; Capusan et al., Citation2016; Lansford et al., Citation2010), internalising psychopathology such as depression and anxiety (Li et al., Citation2016; Nanni et al., Citation2012; Takizawa et al., Citation2014) and psychotic symptoms (Arseneault et al., Citation2011; Fisher et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, victimised children are more likely than their non-victimised peers to have lower educational attainment (Currie & Widom, Citation2010), be unemployed or “Not in Education, Training or Employment” (NEET; Brimblecombe et al., Citation2018; Jaffee et al., Citation2018), engage in criminal offending (Malvaso et al., Citation2018), be teenage parents (Herrenkohl et al., Citation1998), and experience further victimisation (Ports et al., Citation2016) and loneliness (Matthews et al., Citation2017) in adulthood. Such adverse outcomes may have negative and long-lasting implications for the individual’s health, wellbeing and life-opportunities as well as entailing significant costs for communities and public services.

Although victimisation is a key risk factor for later psychopathology and poor functioning, there is significant heterogeneity of outcomes among victimised children. Indeed, some individuals demonstrate very positive outcomes despite their negative experiences (Cicchetti, Citation2013; Rutter, Citation2013). Research seeking to understand why some victimised children are vulnerable to poor outcomes whereas others are resilient has identified a wide range of moderating factors at the level of the individual (e.g. intelligence, personality), family (e.g. socio-economic status, parental warmth) and community (e.g. peer relationships, social support) (Afifi & MacMillan, Citation2011; Crush et al., Citation2018; Meng et al., Citation2018). This knowledge is important to identify potentially modifiable factors to target to reduce the detrimental impact of victimisation and to help identify children who may be at greater risk and in need of support.

Crucially, these studies inform us about the factors that increase or decrease victimised children’s risk of poor outcomes on average. However, it cannot be assumed that such knowledge can be directly applied to accurately forecast outcomes for individual victimised children (Danese, Citation2020). As such, these findings are of limited practical use to health and social care practitioners who assess individual children and therefore seek insight into that particular child’s level of future vulnerability or resilience. Our recent work to translate this current knowledge into a risk calculator screening tool that makes individual-level predictions is therefore notable (Latham et al., Citation2019; Meehan et al., Citation2020). Although this tool needs to be validated in external samples before being implemented, our initial evidence demonstrates its potential to support practitioners to accurately identify which victimised children are at high risk of developing poor outcomes at the transition to adulthood. In turn, this could promote a more cost-effective allocation of resources by enabling practitioners to target preventative interventions to those children who are most in need and, therefore, most likely to benefit.

However, the implementation and use of a risk calculator by practitioners to predict adverse outcomes among children exposed to victimisation may not be straight-forward. For example, there is a need to consider who should administer the tool and in what setting. Furthermore, it may raise issues regarding the implications of a victimised child being identified as “high risk” which will need to be carefully thought through to ensure the tool is implemented sensitively. Therefore, it is vital to investigate what the key considerations are from those practitioners who might use the risk calculator (e.g. social workers, psychiatrists) as well as those with whom it would be used (e.g. children exposed to victimisation).

Thus, this qualitative study aimed to explore the views of young people with lived experience of childhood victimisation or mental health problems, and practitioners from health and social care about the potential use of a screening tool to identify those victimised children who are at highest risk of developing psychopathology and poor functional outcomes. Their opinions were gathered via focus groups (with young people) and individual interviews (with practitioners). The main aspects focused on were how to best integrate such a screening tool into health and social care services in the United Kingdom (UK), the potential benefits and issues that may arise when implementing and undertaking the screening, and how risk prediction would be best communicated to children and their families. We also explored with the young people how our risk calculator research could be communicated effectively to children, their families, practitioners and the wider public. The findings are intended to provide valuable information to inform future studies aimed at implementing and evaluating the use of such a risk calculator in practice.

Materials and methods

Participants

Young people were recruited to take part in two focus groups. For inclusion, they had to be aged 18–25 years, reside in the UK, and self-identify as either having mental health problems and/or childhood exposure to abuse, neglect, domestic violence or bullying. Recruitment was undertaken in collaboration with the McPin Foundation – a London-based mental health charity – who shared advertisements via Twitter and via email with their network of young people.

Practitioners aged over 18 years who resided in the UK and worked in health or social care services supporting children or young people who have been exposed to victimisation were also recruited. Advertisements were circulated via email to local Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and National Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) Service Centres, shared through Twitter and via the research recruitment websites of King’s College London and the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

Procedure

Full ethical approval for the study was granted by the Psychiatry, Nursing, and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee at King’s College London (ref.: HR-18/19-10547) and all participants provided informed written consent. Young people were invited to attend two semi-structured focus groups held at the McPin Foundation offices in London. Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire at the beginning of the sessions. The focus groups were co-facilitated by a member of the McPin Foundation (RKT) and a King’s College London researcher (RML). Each group lasted no longer than three hours, was audio-recorded and then transcribed. Young people received a £90 voucher for their participation in a focus group and were reimbursed for their travel expenses.

Initially, we invited practitioners to take part in a focus group. However, due to difficulties identifying a mutually convenient time that a sufficient number of practitioners could attend, we instead conducted semi-structured individual interviews with each participant to ascertain their views. These one-to-one interviews typically lasted for approximately one hour and were audio-recorded and then transcribed. Practitioners were offered a £10 voucher in return for their participation.

Materials

Semi-structured topic guides (see Supplementary Materials) were developed to guide the focus group discussions and interviews. These outlined open-ended questions related to identifying risk, protective factors and prevention, and – for the young people’s focus groups – communication of the risk calculator research. Example questions included: “What factors in a child’s life do you think might increase their risk of having mental health problems and poor functioning following exposure to victimisation?”, “How receptive would you be to implementing a screening tool to identify victimised children at high risk of poor mental health and functioning in your role?”; and “Who do you think would be interested in hearing about the screening tool?”. Questions for the young people were tailored to ensure the language was accessible.

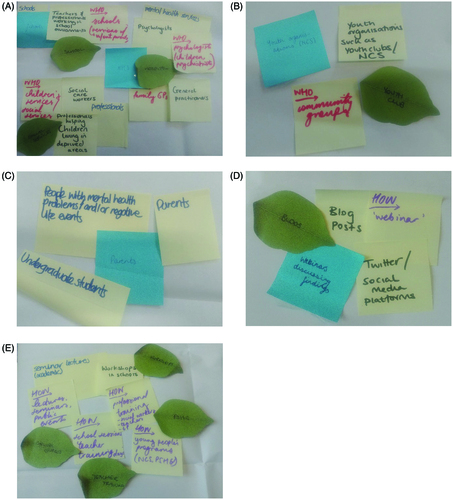

We provided the young people with an outline agenda for the focus group session, so they were aware of what topics to expect and scheduled breaks. To facilitate their discussions, we included some activities in the focus groups. For example, participants wrote their ideas on post-it notes which were then used to create visual mind maps. We also used cards with different emotions written on them (e.g. “hopeful”, “embarrassed”, “worried”) to help them consider how a victimised child may feel if they were identified as being at high risk of having poor outcomes. Photographs were taken of the work produced through these activities to accompany the focus group audio recordings.

Analysis

Transcripts and photographs were coded and analysed using the software package NVivo 12. Thematic analysis was used with the aim of understanding young peoples’ and practitioners’ views regarding the acceptability and feasibility of using a risk calculator to identify those victimised children who are most vulnerable to psychopathology and poor functioning. The six phases of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) were followed to guide this analytic process. Transcripts were read and re-read to establish familiarity, initial codes were then generated, and broader themes identified. These themes were then refined and defined. One researcher (RML) independently coded all transcripts. A second researcher (HLF) independently coded one third of the transcripts and any differences were resolved by discussion and repeated inspection of the data until a consensus was reached.

Results

Sample characteristics

Two focus groups with young people were held. The first group comprised four participants and the second group included an additional two participants, all of whom had lived experience of mental health problems and childhood victimisation. Participants were predominantly female and aged 20–21 years old (see ).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of young people participating in focus groups.

Thirteen individual interviews were conducted with practitioners. The majority of whom were female, white British, and most commonly aged 30–39 years old. Approximately, half of the practitioners worked in health care and half were social workers (see ).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of practitioners participating in interviews (n = 13).

Thematic analysis

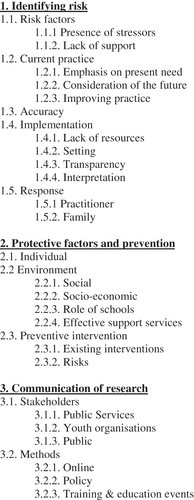

From the two focus groups and 13 interviews, 10 main themes were identified. These themes were organised according to the three topics of discussion: (i) identifying risk (risk factors, current practice, accuracy, implementation, response); (ii) protective factors and prevention (individual, environment, preventative intervention); and (iii) communication of research (stakeholders, methods). Several of these themes also included subthemes (see for an overview of the thematic structure).

Figure 1. Thematic structure overview with all codes that were used to designate themes and sub-themes.

Figure 2. Photographs of the young people’s focus group mind maps of ideas for communicating the research on the risk calculator both to whom (A–C) and how (D, E).

Full details and explanations of the themes and subthemes are provided in with illustrative quotes from the young people and practitioners. We found that themes were largely similar across the two stakeholder groups.

Table 3. Thematic analysis of young people’s (n = 6) and practitioners’ (n = 13) views regarding the potential use of a risk calculator to identify victimised children most at risk of developing psychopathology and poor functioning in young adulthood.

Discussion

This study explored the views of young people and practitioners regarding the acceptability and feasibility of implementing a risk calculator to identify children who are most at risk of developing psychopathology and poor functioning following victimisation. Thematic analysis revealed significant commonality between the considerations of these two key stakeholder groups. We discuss below the implications of our findings for future work aimed at implementing the screening tool.

Our study suggests that the risk calculator would be a relevant and novel addition to practitioners’ toolkits when working with victimised children (theme 1.2. “current practice” and subtheme 1.4.2. “setting”). Even though children’s current presentation was often the primary focus of practitioners’ assessments, many also considered what their future needs may be. We found that practitioners typically relied on their professional experience and knowledge to do this. Some people did also identify tools – including the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) questionnaire (Felitti et al., Citation1998) and the Risk and Resilience Matrix (Daniel & Wassell, Citation2002) – that they believed could be used to inform their assessment. However, the suitability of these tools for forecasting individual outcomes is limited. For example, although research on ACEs is important for highlighting the association between childhood adversity and poor outcomes, not everyone follows the average pattern. That is, many individuals who score high on the ACE checklist do not show poor outcomes therefore it cannot be assumed that screening for ACEs will give accurate information of individual risk prediction within groups of victimised children (Danese, Citation2020). Similarly, although the Risk and Resilience Matrix encourages practitioners to consider the presence of protective factors alongside the child’s experience of adversity, it does not translate this information into a prediction of vulnerability or resilience related to a specific future outcome. Using the matrix to forecast a victimised child’s future mental health and functioning thus requires subjective interpretation by the practitioner. Our findings therefore suggest that an individualised risk calculator for future psychopathology and poor functioning fills an important gap that could help these practitioners to assess and support the future wellbeing of children who have experienced victimisation.

Our study also showed that young people and practitioners were positive about the notion of early intervention to try and prevent psychopathology and functional problems from developing among individuals exposed to childhood victimisation (subthemes 1.2.3. “improving practice” and 1.2.2. “consideration of the future”). Although this approach was endorsed by young people as well as practitioners in both social work and CAMHS, most CAMH services are not currently set up to provide preventative mental health intervention as their limited resources are concentrated on those with existing and severe psychopathology instead. This has important implications for how effectively the risk calculator could be implemented into UK health and social care services. It is vital that a victimised child who is screened and identified as being at high risk of developing mental health problems has access to appropriate support regardless of whether they have already developed psychiatric disorders. Our findings cast some doubt on whether this would currently be the case (subtheme 1.2.1. “emphasis on current need”), suggesting that a shift towards preventative intervention may be required (together with allocation of enough resources) for successful implementation and utilisation of other sectors, such as schools, primary care or charities (subtheme 1.4.2. “setting”). However, we posit that it is also possible that use of the tool could contribute to this shift as it has the potential to provide a more effective means of allocating preventative resources to those who are most in need and therefore most likely to benefit (subtheme 1.2.3. “improving practice”).

The availability of preventative intervention was found to be important not only for the effectiveness of the risk calculator, but it was also fundamental to practitioners’ acceptance of it (subtheme 1.4.1. “lack of resources”). In the absence of appropriate intervention, screening children to see who is most vulnerable for developing poor outcomes was viewed as unacceptable; practitioners deemed it to be unethical and potentially detrimental to the child due to the risk of fuelling feelings of hopelessness and negative self-fulfilling prophecies (Merton, Citation1948). There are a wide range of interventions and support currently available to promote the mental health and functioning of children who have experienced victimisation (subtheme 2.3.1. “existing interventions”). These include initiatives that are delivered in schools and communities (e.g. mentoring), targeted support for specific victimisation experiences (e.g. the NSPCC’s “Letting the Future In” for sexual abuse survivors) and therapeutic support through CAMHS (e.g. cognitive behavioural therapy). More work will be needed to establish a solid evidence base for early interventions in victimised children (National Institute for Health Care and Excellence, Citation2018). Importantly though, we note the context of limited resources in which these services operate resulting in long waiting lists, restrictions on the duration of support, and variability in what services are available in different geographic areas, all of which could impact the effectiveness and acceptability of the risk calculator.

Another key consideration that we identified for the potential use of the risk calculator was the transparency with which the tool would be used with victimised children and their caregivers (subtheme 2.4.3. “transparency”). Our findings revealed a tension between a desire to work openly with families by involving the child in the screening and sharing the resulting risk score information, and a desire to protect them from feeling overburdened by numerous assessments and frightening information. Young people expressed similarly mixed feelings about whether or not risk scores should necessarily always be shared with children and their caregivers. There is likely not a “one size fits all” solution to this; instead we suggest that a decision may be best made on a case-by-case basis taking account of factors such as the child’s age and level of understanding, any legal obligation to share information with the child’s parents, and the potential for increasing risk further. Making such sensitive judgements about what and how information should be shared with vulnerable children and their caregivers is certainly not unique to the use of this risk calculator but is a core part of health and social care practitioners’ training and day-to-day work. Thus, they are likely well-placed to determine what level of transparency and involvement is appropriate for a particular child they wish to screen whilst upholding core ethical values of honesty, openness and protecting from harm.

Finally, our findings suggest that successful implementation of the risk calculator will require training for the practitioners who will use it. We found that people were very knowledgeable about the wide range of factors that could buffer or accentuate the risk of poor outcomes following exposure to victimisation (themes 1.1. “risk factors”, 2.1. “individual” and 2.2. “environmental”). However, awareness of this complexity and of individual differences in response to victimisation gave rise to scepticism about whether a statistical tool could accurately predict such outcomes (theme 1.3. “accuracy”). Increasing practitioners’ understanding of the risk calculator as a means of individual – rather than average – prediction and evidencing its accuracy will therefore be critical in promoting their acceptance of the tool. This is consistent with the What Works for Children’s Social Care recommendation for the use of prediction models and their limitations to be included in social worker training (Leslie et al., Citation2020). Additionally, practitioners will need to be trained in how to interpret the risk scores. In particular, further work is needed to determine a clinically appropriate cut-point to guide practitioners regarding what they should interpret as a “high” risk score that requires action (subtheme 1.4.4. “interpretation”).

Limitations

We acknowledge some limitations of our study. First, our sample of young people was relatively small. Second, the self-selecting and predominantly female sample may limit the generalisability of findings as those who volunteered may have a greater interest in research and a proclivity towards the use of a screening tool. However, the views of our young people and practitioners were not unequivocally positive with regards to the acceptability and implementation of a risk calculator. Moreover, men are indeed under-represented in health and social care roles in the UK (Les, Citation2017; Skills for Care, Citation2017) such that our practitioner sample reflects the female-dominated gender composition of these professions. Despite attempts to achieve a balanced gender composition of young people, the low number of males means that this sample is not representative of children who experience victimisation (Radford et al., Citation2013). Third, the study did not include parents/carers or teachers who also have a key role in supporting children and young people who have experienced victimisation. Ascertaining the views of these stakeholders is also important, particularly given our finding that schools and/or multi-agency meetings may be a useful setting for the risk calculator to be used. Finally, this qualitative study was undertaken while the risk calculator is still in the early stages of development and validation. Therefore, we were unable to demonstrate to participants exactly what the risk calculator would look like or how well it performs in external samples. Nonetheless, finding out what young people and practitioners’ feel are the main considerations is critical to inform the further development of the risk calculator and future implementation efforts.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding these limitations, the findings of the current study provide useful insights into the acceptability and feasibility of implementing a risk calculator to identify victimised children who are most at risk for developing psychopathology and poor functioning. Overall, young people and practitioners recognised the potential for an accurate screening tool like this to enhance health and social care practice but also highlighted key considerations and challenges related to its successful implementation. This will be useful to inform future work in this area.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are extremely grateful to all of the individuals who gave up their time to take part in the interviews and focus groups, and to the McPin Foundation for their assistance with recruitment to and facilitation of the focus groups.

Disclosure statement

All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Afifi, T. O., & MacMillan, H. L. (2011). Resilience following child maltreatment: A review of protective factors. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 56(5), 266–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371105600505

- Arseneault, L., Cannon, M., Fisher, H. L., Polanczyk, G., Moffitt, T. E., & Caspi, A. (2011). Childhood trauma and children's emerging psychotic symptoms: A genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(1), 65–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040567

- Braga, T., Gonçalves, L. C., Basto-Pereira, M., & Maia, Â. (2017). Unraveling the link between maltreatment and juvenile antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 33, 37–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.006

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brimblecombe, N., Evans-Lacko, S., Knapp, M., King, D., Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2018). Long term economic impact associated with childhood bullying victimization. Social Science & Medicine, 208, 134–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.014

- Capusan, A. J., Kuja-Halkola, R., Bendtsen, P., Viding, E., McCrory, E., Marteinsdottir, I., & Larsson, H. (2016). Childhood maltreatment and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in adults: A large twin study. Psychological Medicine, 46(12), 2637–2646. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001021

- Cicchetti, D. (2013). Annual research review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children-past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(4), 402–422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x

- Crush, E., Arseneault, L., Jaffee, S. R., Danese, A., & Fisher, H. L. (2018). Protective factors for psychotic symptoms among poly-victimized children. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(3), 691–700. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx111

- Currie, J., & Widom, C. S. (2010). Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreatment, 15(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559509355316

- Danese, A. (2020). Annual research review: Rethinking childhood trauma – new research directions for measurement, study design and analytic strategies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(3), 236–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13160

- Daniel, B., & Wassell, S. (2002). The early years; assessing and promoting resilience in vulnerable children. Jessica Kingsley.

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258.

- Fisher, H. L., Schreier, A., Zammit, S., Maughan, B., Munafo, M. R., Lewis, G., & Wolke, D. (2013). Pathways between childhood victimization and psychosis-like symptoms in the ALSPAC birth cohort. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(5), 1045–1055. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbs088

- Herrenkohl, E. C., Herrenkohl, R. C., Egolf, B. P., & Russo, M. J. (1998). The relationship between early maltreatment and teenage parenthood. Journal of Adolescence, 21(3), 291–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.1998.0154

- Jaffee, S. R., Ambler, A., Merrick, M., Goldman-Mellor, S., Odgers, C. L., Fisher, H. L., Danese, A., & Arseneault, L. (2018). Childhood maltreatment predicts poor economic and educational outcomes in the transition to adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 108(9), 1142–1147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304587

- Lansford, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2010). Does physical abuse in early childhood predict substance use in adolescence and early adulthood? Child Maltreatment, 15(2), 190–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559509352359

- Latham, R. M., Meehan, A. J., Arseneault, L., Stahl, D., Danese, A., & Fisher, H. L. (2019). Development of an individualized risk calculator for poor functioning in young people victimized during childhood: A longitudinal cohort study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 104188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104188

- Les, R. (2017, September 5). Drive to get more men into social work. Frontline. https://thefrontline.org.uk/drive-to-get-more-men-into-social-work/

- Leslie, D., Holmes, L., Ott, E. (2020). Ethics review of machine learning in children’s social care. https://whatworks-csc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/WWCSC_Ethics_of_Machine_Learning_in_CSC_Jan2020.pdf

- Li, M., D'Arcy, C., & Meng, X. (2016). Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychological Medicine, 46(4), 717–730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002743

- Malvaso, C. G., Delfabbro, P., & Day, A. (2018). The maltreatment-offending association: A systematic review of the methodological features of prospective and longitudinal studies. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 19, 20–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015620820

- Matthews, T., Danese, A., Gregory, A. M., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Arseneault, L. (2017). Sleeping with one eye open: Loneliness and sleep quality in young adults. Psychological Medicine, 47(12), 2177–2186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000629

- Meehan, A. J., Latham, R. M., Arseneault, L., Stahl, D., Fisher, H. L., & Danese, A. (2020). Developing an individualized risk calculator for psychopathology among young people victimized during childhood: A population-representative cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 262, 90–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.034

- Meng, X., Fleury, M.-J., Xiang, Y.-T., Li, M., & D'Arcy, C. (2018). Resilience and protective factors among people with a history of child maltreatment: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(5), 453–475. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1485-2

- Merton, R. K. (1948). The self-fulfilling prophecy. The Antioch Review, 8(2), 193–521.

- Nanni, V., Uher, R., & Danese, A. (2012). Childhood maltreatment predicts unfavorable course of illness and treatment outcome in depression: A meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(2), 141–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020335

- National Institute for Health Care and Excellence. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder NICE guideline (NG116). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116

- Ports, K. A., Ford, D. C., & Merrick, M. T. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and sexual victimization in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 313–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.017

- Radford, L., Corral, S., Bradley, C., & Fisher, H. L. (2013). The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment and other types of victimization in the UK: Findings from a population survey of caregivers, children and young people and young adults. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(10), 801–813. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.004

- Rutter, M. (2013). Annual research review: Resilience-clinical implications. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(4), 474–487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02615.x

- Skills for Care. (2017, November 17). What do we know about men working in social care? skillsforcare. https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/About/Blog/Article/What-do-we-know-about-men-working-in-social-care.aspx

- Takizawa, R., Maughan, B., & Arseneault, L. (2014). Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: Evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 777–784. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401