Abstract

Background

People with existing mental health conditions may be particularly vulnerable to the psychological effect of the COVID-19 pandemic. But their positive and negative appraisals, and coping behaviour could prevent or ameliorate future problems.

Objective

To explore the emotional experiences, thought processes and coping behaviours of people with existing mental health problems and carers living through the pandemic.

Methods

UK participants who identified as a mental health service user (N18), a carer (N5) or both (N8) participated in 30-minute semi-structured remote interviews (31 March 2020 to 9 April 2020). The interviews investigated the effects of social distancing and self-isolation on mental health and the ways in which people were coping. Data were analysed using a framework analysis. Three service user researchers charted data into a framework matrix (consisting of three broad categories: “emotional responses”, “thoughts” and “behaviours”) and then used an inductive process to capture other contextual themes.

Results

Common emotional responses were fear, sadness and anger but despite negative emotions and uncertainty appraisals, participants described efforts to cope and maintain their mental wellbeing. This emphasised an increased reliance on technology, which enabled social contact and occupational or leisure activities. Participants also spoke about the importance of continued and adapted mental health service provision, and the advantages and disadvantages associated with changes in their living environment, life schedule and social interactions.

Conclusion

This study builds on a growing number of qualitative accounts of how mental health service users and carers experienced and coped with extreme social distancing measures early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather than a state of helplessness this study contains a clear message of resourcefulness and resilience in the context of fear and uncertainty.

Keywords:

Introduction

On 23 March 2020, the UK government announced measures to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. People were told to remain at home, only go out for essential purposes, and to self-isolate if they came into contact with the virus or were in an “at-risk” group. Although these measures were introduced to protect the community and ease pressure on the UK NHS services, concerns have been raised about the consequences for mental health (Venkatesh & Edirappuli, Citation2020). Evidence from previous pandemics suggests an increased experience of difficult emotions such as anger, confusion and anxiety, and high prevalence of clinical disorders such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) amongst those exposed to quarantining measures (Brooks, Citation2020). Estimates from late March to early April 2020, when this study was conducted, suggested that COVID-19 was affecting the well-being of 53.1% of the UK general population, with high anxiety reported by 49.6% compared to 21% at the end of 2019 (Office for National Statistic, Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

There is, however, emerging evidence of improved mental well-being and reduced stress. These positive effects may be based on having more free time and reduced demands to leave home, but still being engaged in social interactions using technology (Lau, Citation2020; MQ & AMS, Citation2020). Individuals may also adapt to the stresses associated with the pandemic which is often referred to as resilience (Vinkers, Citation2020). Core psychological components of the “3 Cs” resilience model developed for natural disasters (Reich, Citation2006) include: Control (a feeling of personal agency), Coherence (managing uncertainty through knowledge provision by those in power) and Connectedness (feeling a sense of togetherness). In the USA going outside, exercise, a perception of strong social support, good sleep and spirituality are associated with stronger levels of resilience during the current pandemic (Killgore et al., Citation2020). Healthy family processes (e.g. good communication and shared beliefs) are also thought to promote resilience (Prime et al., Citation2020).

In the early stages of the UK lockdown, an online survey of people with lived experience of mental health problems highlighted concerns about the pandemic exacerbating pre-existing mental health issues (MQ & AMS, Citation2020). This is similar to previous pandemics. Anxiety during the 2009 H1N1 Swine Flu pandemic increased and individuals with pre-existing anxiety experienced more intolerance of uncertainty and fear of contamination (Taha et al., Citation2014; Wheaton et al., Citation2012). Informal carers may also be at risk of increased strain during the pandemic due to a reduced access to support services (Onwumere, Citation2020).

Mental health in those with pre-existing mental health problem is not inevitable as living circumstances and psychological factors also contribute and can mitigate people’s experiences. Folkman and Lazarus’ (Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1984) transactional model of stress and coping proposes that appraisals of both threat and coping influence how an individual responds to stressful situations. In relation to pandemics, beliefs about (a) how severe the virus is, (b) how effective the recommended behaviours are and (c) the individual’s ability to engage in these behaviours, may be helpful in understanding changes in mental health (Teasdale et al., Citation2012). Support for this theory comes from data collected in the H1N1 Swine Flu (Prati et al., Citation2011) and SARS (Taha et al., Citation2014) pandemics as increases in anxiety and worry were mediated by appraisals of threat and control.

Exploring the psychological and individual factors that contribute to mental well-being or ill-health during the COVID-19 pandemic is a research priority (Holmes, Citation2020). This study investigated in detail the psychological experiences of people with mental health problems and informal carers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. We sought to elicit cognitive appraisals and behaviours that were either problematic for, or protective of mental health difficulties during a period of enforced social distancing.

Methods

Design

The study was based on principles of co-production with service user researchers being involved at all stages of the research process, including the generation of research questions, design, data collection and analysis. The qualitative methods involved semi-structured interviews.

Participant characteristics

Participants were eligible if they were at least 16 years and were either currently, or had experience of, using mental health services or they identified as an informal carer for somebody who has used services. Participants needed internet or phone access and were excluded if they were unable to give informed consent. They were recruited through purposive and snowball sampling via existing patient involvement and advisory groups.

Researcher characteristics

Six researchers conducted the interviews with participants. They all had lived experience of a mental health problems and the majority were employed as service user researchers. This experience allowed the researchers to relate more closely to the experience of participants being interviewed. Three service user researchers analysed the data, and, again, drew on personal experience to guide the interpretation.

Procedure and ethics

The study was granted ethical approval by the Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee at King’s College London (reference: MOD-19/20-18180). Mental health service users and carers interested in research and who were members of advisory panels were approached and given an information sheet about the study by researchers at King’s College London or a charity, the McPin Foundation, and given time to decide if they would like to take part in the study. Participants provided written informed consent which included an electronic signature via email prior to interview. The interviews were conducted by the six service user researchers between 31 March 2020 and 9 April 2020, via telephone or videoconferencing software, based on participant preference and accessibility. Clinical and demographic characteristics were collected and then participants were interviewed. They were reimbursed for their participation. Participants were provided with information on mental health support helplines and online resources and researchers also supported participants’ well-being and welfare throughout the interview.

Interview

The topic guide was developed from research identifying the impact of past pandemics, social distancing and self-isolation on mental health, potential psychological mechanisms and coping strategies (available on request). The discussions explored: the general impact of social distancing and self-isolation on their mental health and access to services; specific triggers for mental health problems; current methods of coping; and other protective factors. The interviews lasted for approximately 30 minutes and were digitally recorded and transcribed using Microsoft Teams videoconferencing software.

Sample size and data analysis

We conducted interviews until data saturation was reached which was established by a review of the summary findings for each semi-structured interview question. A framework analysis (Gale et al., Citation2013) was applied to the data, combined with an inductive process to code themes that did not fit within the a priori framework matrix, consisting of three broad categories: “emotional responses”, “thoughts” and “behaviours”. Three service user researchers read and re-read transcripts and independently coded the data into themes (created a summary label for individual quotes from each transcript), charting these themes into the framework matrix, i.e. whether the participant was referring to an emotion felt, a thought experienced or a behaviour engaged in. For data not categorised, each service user researcher generated a set of additional themes and they became major themes if they were coded by more than one person. The three service user researchers met on a regular basis to discuss and resolve discrepancies in their coding. However, a final set of major themes and subthemes were generated by one service user researcher (DM) who reviewed the three analysis results and amalgamated similar codes fitting inside and outside of the initial framework.

Results

Sample characteristics

Thirty-one participants were included in the analysis (21 women, eight men, two non-binary) and their ages varied from 16 to 79 (M = 42.61, SD 20.49). More than half were service users (18/31; 58%), 16% (5/31) were carers and 26% (8/31) identified as both service users and carers.

Emerging themes

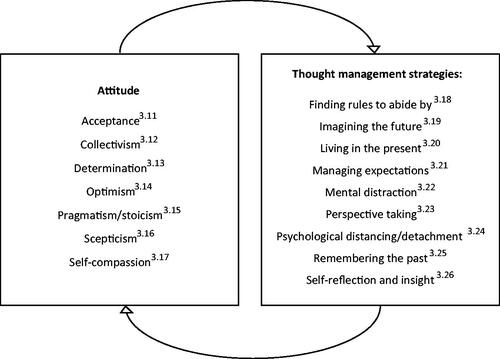

The summary of the full framework of themes is shown in and these themes are described in detail below.

Table 1. Framework of categories and emerging themes.

Emotional responses

Participants revealed a multitude of negative emotional responses to their current situation. These were categorised into the seven themes, highlighted in bold, with illustrative quotes provided in .

Table 2. Illustrative quotes for the participants interviewed for all dimensions and themes, referenced throughout the main text.

Many participants expressed fear. This included fear of infection, fear of death, fear about the future and fear for their mental health1.1. Anger was expressed as frustration1.2, annoyance and irritability, e.g. losing their temper with others. Many felt a sense of sadness at their situation1.3 and commented about feeling “depressed”, “flat” and tearful. Some spoke of memories being reactivated and this producing negative emotions, including feelings of guilt1.4. Others expressed boredom with things just feeling monotonous and tedious and every day being similar1.5. Other negative feelings included participants expressing disgust at a lack of police presence or enforcement of social distancing measures1.6. Surprise, and even horror, was expressed, for example, about racism and people not following recommending behaviours1.7.

However, there were also more positive experiences (illustrative quotes also provided in ). Some spoke of feeling of happiness1.8, excited and experiencing a sense of relief for having “freedom” and less demands on their time. Others expressed a sense of calm and feeling more relaxed due to a slower pace of life1.9.

Thoughts

These comments fell into five main categories of appraisals (see for a list of illustrative quotes). Some appraisals directly related to their life situation with many describing difficulties with looking forward, disliking the novelty of the situation. They reported new sources of worry (e.g. about the effect on education, accessing essential items, and the wider societal, economic and political impact of the pandemic2.1). Some reported having too much free time, which made worries harder to contain. More positive appraisals on life circumstances included thoughts about increased time to manage their health condition2.2. Not feeling stuck indoors and having some freedom, e.g. to go for a walk, were also viewed as positive.

There was a strong message that social support was vital. But many reported a strain on their relationships in the home because of the pandemic2.3. Some expressed negative views about the behaviour of others (e.g. not following rules2.4) and felt divide between “healthy” and “vulnerable” groups and were concerned about who would receive healthcare resources (e.g. ventilators).

Some spoke of the virus as highly contagious, very serious and worse than past viruses, with a risk of death2.5. Consequently, they were very worried about catching the virus and the stigma attached to those who might have contracted it. But others thought COVID-19 was no more serious than past viruses and felt safe as they were unlikely to come into contact with it2.6. Participants felt there was a challenge in determining the accuracy of information provided about the pandemic2.7 and some spoke of rumours or conspiracy theories that they had heard. Coverage in the media was perceived as negative and scary, revealing the damage outside the relative security of their own homes. Some felt that this coverage was overly negative and not presented a balanced overview of the current risk.

Some participants expressed dissatisfaction with organisations and services. For example, in terms of the government’s response; they felt it had been slow, recommended ineffective behaviours, and lacked enforcement or helpful information. They worried about the pressures on healthcare, and were concerned about the cancellation, postponement or adaptation of their care. Remote support was valued but, for a few, it was not viewed as the same as in-person care. Some felt their health issues were treated as secondary to COVID-192.8, whilst others, mindful of the high demand faced by the NHS, felt unable to reach out for help. They expressed several unmet needs (including the need for increased service provision and improved communication) and a sense of hopelessness that services would not improve during the crisis. Other participants, who were receiving support, thought mental health services were doing their best or even doing well, and were important for keeping them well2.9. They spoke of trusting officials and professionals but suggested that services needed to increase their visibility to the public about being open (e.g. through using social media to broadcast this message).

In addition to the appraisals of their environment and the world around them, participants also expressed thoughts about themselves. Negative attitudes towards oneself were common and exacerbated by the pandemic, with participants thinking that they were being judged and had low self-worth. Some also expressed feeling isolated and lonely. The majority felt uncertain and some spoke of thoughts about feeling lost, unmotivated and overwhelmed. They worried about their ability to cope long term but not all appraisals of self were negative. Many felt that they were more resilient because they had learnt coping strategies from past adversity that they could draw on and felt better prepared to manage a crisis2.10. Participants acknowledged the importance of feeling safe and a sense of control during times of great uncertainty and making adjustments in their daily routine provided that sense of autonomy and ownership. Participants expressed several cognitive coping strategies that were helping them to manage the current situation. These ways of coping are summarised in .

Behaviours

Eight main themes emerged (see for selected quotes from participants). In terms of actions directly related to the virus, participants followed the recommended behaviours, e.g. rules around social distancing, but sometimes this was more difficult, for practical and emotional reasons. Other precautions were followed including staying at home as much as possible, the use of gloves and masks, increased handwashing, and sanitising objects3.1. Some illness-related behaviours were reinforced by the current situation, e.g. excessive handwashing and checking (the news) for individuals with obsessive compulsive disorder, and preoccupation with access to the right foods and reduced exercise for those with eating disorders3.2. More generally, in terms of health-related behaviours, participants spoke of disrupted sleep and exercise routines as well as missing medication. Despite these difficulties, many spoke about actions to maintain good health (including mental health), such as taking medication as prescribed, monitoring for symptoms of COVID-19, maintaining good levels of hygiene, supporting the immune system with vitamins, eating well and exercising (including walks).

Participants spoke about how they were spending their time and the changes associated with this. Many leisure activities had been disrupted or stopped altogether3.3. Despite this, participants discussed activities they were enjoying. Participants specifically spoke about home-focused activities, taking the opportunity to do more gardening, home improvement and household chores4.4. Some concerns were raised about excess use of computers, smartphones and televisions but participants viewed technology-related activities as very important to enable socialising and to support leisure activities (e.g. listening to podcasts, watching television and films) and health management (e.g. use of mobile health apps3.5). Maintaining social behaviours and support through virtual means was reported as important due to less physical contact but so was the maintenance of personal space3.6. Good communication, and sometimes humour, was considered vital when interacting with others. Some reported continued engagement in organised online prayer groups and virtual services3.7. Others engaged in more personal forms of religious worship and spirituality. In addition, continued engagement in work was a way of remaining occupied and provided a sense of purpose3.8. Where paid employment was limited, participants spoke of engagement in volunteering, e.g. research and patient and public involvement (PPI) opportunities.

Change in routine was a common experience with the need to adapt to a new way of living3.9 and manage their time differently. Establishing and maintaining a new routine was described as a positive way of coping and feeling in control. Although some felt that they were being less productive, others described keeping busy and distracted. Rather than planning for the future, participants described taking things day by day3.10. Many wanted to keep informed about COVID-19 for some sense of control, but they also raised the importance of limiting news consumption as it was distressing3.11.

Despite changing their current behaviour, some felt that life was not much different, especially those who were socially isolated before the pandemic3.12.

Other contextual categories

It may be important to note that a minority of participants had concerns about being in a high-risk group (e.g. an older adult, a person with a pre-existing physical health condition or being a keyworker in addition to being a service user and or an informal carer). Participants belonging to these high-risk groups (including carers in the sample) spoke about being severely affected by the restrictions and feeling greater levels of distress4.1. Some participants did not experience their life circumstances as either positive or negative or reported no change and some reported a continued low level of social interaction or cleanliness, through choice, rather than following any recommendations4.2.

Comparing the views of service users and carers

Service users and carers expressed their own unique challenges. For service users, pre-existing health conditions, obtaining medication and re-emerging symptoms of mental health conditions were the main concern, whereas for carers it was their additional responsibilities for others that was causing potential pressure and strain. Formal support was discussed by service users more than carers.

Although service users spoke more about the challenges related to following the recommended behaviours, a greater proportion of service users reported that they were self-isolating. They expressed feeling less physically connected to others, which was associated with a variety of negative emotions, including stress or anxiety and anger, and feelings of exclusion or longing for social contact or boredom. Carers reported negative emotions but only fear, anger and sadness. Service users discussed disruption to the structure and routine of their life more than carers and more concerns were raised about their ability to sustain coping, long-term. Despite the negative experience described, service users spoke proportionally more about feeling safe, in control and grateful and fortunate relative to others.

The personal accounts suggest that service users and carers may also have coped slightly differently during the pandemic. Service users spoke about turning to technology, e.g. for social interaction and support, more than carers, who talked about being busy and distracted in other ways (including caring tasks). Whilst service users and carers both expressed interest in keeping informed about the pandemic, service users spoke more about limiting news consumption because it was affecting their mood negatively.

Discussion

This study builds on a growing number of qualitative accounts of how mental health service users and carers experienced and coped with extreme social distancing measures early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings provide a formulation, structured through a simple framework. Despite its simplicity, the richness and varied nature of the accounts was apparent.

Whilst some experiences replicated previous findings, especially the experience of negative emotions and an exacerbation of mental health symptoms (Brooks, Citation2020; Gao et al., Citation2020; Huang & Zhao, Citation2020), people in this study also spoke about resilience and positive experiences of adaptation and coping. The quality of the emotional reactions varied across individuals but this contributes to a growing literature suggesting that people experience a multitude of different negative emotions in response to pandemics and social distancing measures including, confusion, fear, anger, grief, boredom and frustration (for a review, see Brooks, Citation2020). However, it also suggests that people can have positive experiences of lockdown including, an increased sense of freedom, joy and calmness due to increased leisure time and the slowed pace of life. With people being encouraged to work from home and some furloughed, leisure time increased and there was greater opportunity for family time, which may have led to improved wellbeing. A qualitative study conducted in care-givers of patients with COVID-19 highlighted that positive and negative emotions often co-exist, but that negative emotions are dominant during the early stages of the outbreak and positive emotions appear much more gradually, which coincided with psychological or life adjustment (i.e. diary writing, mindfulness, exercise, distraction, humour and rationalisation) and growth (i.e. gratitude, personal development and self-reflection) (Sun et al., Citation2020). Given that the response to COVID-19 and associated restrictive measures appears to be heterogeneous, future research should endeavour to elucidate the factors that determine whether a person is able to adapt and cope with the challenges that the virus presents and whether lockdown has a negative or positive impact on their mental health. Moreover, it will be important to determine which factors, if any, are protective of wellbeing.

In our study, participants spoke about resilience, adaptation and coping. In a recent qualitative study that examined the impact of COVID-19 on mental health service users, hospital and care staff expressed hope that an increase in resilience in mental health service users would be one positive outcome from the pandemic (Johnson et al., Citation2020). So far, preliminary evidence suggests that psychological flexibility and resilience are associated with greater well-being during lockdown (Dawson & Golijani-Moghaddam, Citation2020; Killgore et al., Citation2020). Folkman and Lazarus’s theory (Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1984) proposes that experiences of stress are first influenced by primary appraisals (of threat) and secondary appraisals (of coping resources), then by the ability to implement cognitive and behavioural responses (coping strategies). In our interviews, some people felt threat in relation to the virus (the primary appraisal) and some did not, but it was clearly felt to be an uncertain and disruptive time, generating fear about the future, especially for service users. The role of uncertainty in distress has been documented in relation to previous pandemics (Taha et al., Citation2014) but the level of disruption caused by population-wide social distancing measures associated with the management of the COVID-19 pandemic may be unique. In terms of the secondary appraisal, perceptions of coping resources, these were influenced by their service user or carer status with people expressing confidence arising from past experiences of adversity and support from mental health services. Resilience may, in part, arise from knowing how to respond to challenges and feeling in control (Reich, Citation2006). Where people felt out of control and unable to cope, they expressed more stress. Of note, was the increased reliance on technology, especially for service users, which, in the face of social distancing measures, enabled continued contact with others and the ability to maintain purposeful activity, e.g. employment.

Strengths and limitations

This work is unique in that it was designed and run by service user researchers. The benefits of user-led research have been described in Ennis and Wykes (Citation2013) and include greater ease of recruiting to targets and the ability to empathise more closely with the experience of those being interviewed. All recruitment and data collection were performed remotely, encouraging the participation of those who were hard to reach and providing convenience and flexibility (Janghorban et al., Citation2014), but required participants to have access to technology and may not generalise to people who do not have the same access. Whilst we are unable to draw any causal inferences from qualitative data, the results serve as a basis for larger quantitative studies that will help to measure, and test hypothesises generated through the eyes of service users. Data for this study were gathered during a specific two-week period during the UK lockdown, this may have significantly influenced the results generated. Further research in this area should take a longitudinal rather than a cross-sectional approach, factoring in the influence of time. The influence of factors such as age, ethnicity, gender and location may also be important. In this study, the majority were middle-aged, women, who self-identified as a mental health service user or carer and this may have influenced the results. For example, Orgeta and Health (Citation2009) and John and Gross (Citation2004) found that older adults were better able to regulate emotions, had better coping strategies and used cognitive reappraisal techniques more often.

Conclusion

In this study, we took a practical approach, using opportunistic sampling methods, to gain a better understanding of how carers as well as mental health service users were coping, not just focusing on poor mental health but also on protective factors. The aim was to describe the psychological experiences of people who may be vulnerable to distress following the COVID-19 outbreak and enforced social distancing measures. Service users and carers may have their own unique challenges and solutions, but, both groups, emphasised factors that maintain wellbeing. The specific ways in which people coped at the beginning of the UK lockdown period may serve to inform recommendations for management of mental health during pandemics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Brooks, S. K. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

- Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17, 126–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010

- Ennis, L., & Wykes, T. (2013). Impact of patient involvement in mental health research: Longitudinal study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(5), 381–386. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119818

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Gao, W., Ping, S., & Liu, X. (2020). Gender differences in depression, anxiety, and stress among college students: A longitudinal study from China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 292–300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.121

- Holmes, E. A. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

- Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112954. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

- Janghorban, R., Latifnejad Roudsari, R., & Taghipour, A. (2014). Skype interviewing: The new generation of online synchronous interview in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 24152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.24152

- John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1301–1333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00298.x

- Johnson, S., Dalton-Locke, C., Juan, N. V. S., Foye, U., Oram, S., Papamichall, A., Landau, S., Olive, R. R., Jeynes, T., Shah, P., Ralns, L. S., Llloyd-Evans, B., Carr, S., Killaspy, H., Gillard, S., & Simpson, A. (2020). Impact on mental health care and on mental health service users of the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed methods survey of UK mental health care staff. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01927-4

- Killgore, W. D. S., Taylor, E. C., Cloonan, S. A., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113216

- Lau, B. H. (2020). Resilience of Hong Kong people in the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned from a survey at the peak of the pandemic in Spring 2020. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02185385.2020.1778516

- MQ and AMS. (2020). Survey results: Understanding people’s concerns about the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Transforming Mental Health (MQ) and Academy of Medical Sciences (AMS).

- Office for National Statistic. (2020a). Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritain/16april2020

- Office for National Statistic. (2020b). Personal and economic well-being in Great Britain: May 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/personalandeconomicwellbeingintheuk/may2020

- Onwumere, J. (2020). Informal carers in severe mental health conditions: Issues raised by the United Kingdom SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. SAGE Publications Sage UK.

- Orgeta, V. J. A., & Health, M. (2009). Specificity of age differences in emotion regulation. Aging and Mental Health, 13(6), 818–826. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860902989661

- Prati, G., Pietrantoni, L., & Zani, B. (2011). A social-cognitive model of pandemic influenza H1N1 risk perception and recommended behaviors in Italy. Risk Analysis, 31(4), 645–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01529.x

- Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660

- Reich, J. W. (2006). Three psychological principles of resilience in natural disasters. Disaster Prevention and Management, 15(5), 793–798. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560610712739

- Sun, N., Wei, L., Shi, S., Jiao, D., Song, R., Ma, L., Wang, H., Wang, C., You, Y., Liu, S., & Wang, H. (2020). A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. American Journal of Infection Control, 48(6), 592–598. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018

- Taha, S., Matheson, K., Cronin, T., & Anisman, H. (2014). Intolerance of uncertainty, appraisals, coping, and anxiety: The case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. British Journal of Health Psychology, 19(3), 592–605. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12058

- Teasdale, E., Yardley, L., Schlotz, W., & Michie, S. (2012). The importance of coping appraisal in behavioural responses to pandemic flu. British Journal of Health Psychology, 17(1), 44–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02017.x

- Venkatesh, A., & Edirappuli, S. (2020). Social distancing in covid-19: What are the mental health implications? BMJ, 369, m1379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1379

- Vinkers, C. H. (2020). Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 35, 12–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.05.003

- Wheaton, M. G., Abramowitz, J. S., Berman, N. C., Fabricant, L. E., & Olatunji, B. O. (2012). Psychological predictors of anxiety in response to the H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(3), 210–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9353-3