Abstract

Objectives

To conduct a 1-year evaluation of James’ Place, a suicidal crisis centre delivering a clinical intervention in a community setting.

Design

A case series study, following men entering the service during the first year of operation.

Participants

Men experiencing a suicidal crisis referred to the service (N = 265), with N = 176 going on to engage in therapy.

Intervention

The James’ Place Model is a therapeutic intervention offered to men who are in a suicidal crisis. Trained therapists provide a range of therapeutic approaches and interventions, focusing on decreasing suicidal distress and supporting men to develop resilience and coping strategies.

Main outcome measures

CORE-34 Clinical Outcome Measure (CORE-OM).

Results

For all subscales of the CORE-OM there was a significant reduction in mean scores between assessment and discharge (p < 0.001), with all outcomes demonstrating a large effect size. All reductions illustrated a clinically significant change or a reliable change.

Conclusions

Our results support the use of the James’ Place Model for men in suicidal distress to aid in potentially preventing suicides in this high-risk group of the population.

Evaluates a brief psychological clinical intervention delivered in the community.

Model effectively reduces suicide risk and findings can inform future services.

Accessed men receiving an innovative intervention at the time of suicidal crisis.

Highlights

Introduction

With over 800,000 people dying by suicide each year worldwide (WHO, Citation2019a), suicide remains a significant, yet preventable public health risk. A key feature of suicide epidemiology is the significant gender difference in suicide rates (Struszczyk et al., Citation2019). The prevalence of death by suicide among men is consistently higher than females in the majority of countries (Turecki & Brent, Citation2016; WHO, Citation2019b). Recent figures show that men accounted for three quarters (4903 deaths by suicide) of the 6507 registered suicides in 2018 in the UK (ONS, Citation2019a). Suicide mortality among males in England significantly increased by 14% in 2018 compared to 2017, with a 31% increase of men aged 20–24 years dying by suicide and middle-aged men (40–50 years) accounting for a third of all suicides in England in 2018 (ONS, Citation2019a).

Previous suicide attempt forms one of the strongest predictors of suicide (Barzilay & Apter, Citation2014; Blasco-Fontecilla et al., Citation2016; Harris & Barraclough, Citation1997), however, it is widely accepted that the psychosocial determinants of suicidal ideation and suicidal behaviour are multifactorial and complex (O'Connor, Citation2011; O'Connor & Kirtley, Citation2018). Risk factors include unemployment (Yoshimasu et al., Citation2008), living alone (Kposowa et al., Citation1995; NCISH, Citation2018), socioeconomic factors (Kim et al., Citation2016; Pirkis et al., Citation2017) and relationship breakdown including divorce and separation (Corcoran & Nagar, Citation2010; Kposowa, Citation2003; Scourfield & Evans, Citation2015), which pose a significantly greater risk for males than for females (Milner et al., Citation2012; Scourfield & Evans, Citation2015). Risk factors also include loss, grief and misuse of drugs or alcohol (CDCP, Citation2014; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019). Problems associated with poor reporting and rates of help-seeking among men compared to women (Hartley & Petersen, Citation1993; Möller-Leimkühler, Citation2002) add further complexity to the multi-faced nature of suicide. Around 18–19% of people who die by suicide do not access support from a primary care provider in the year preceding their suicide (Mallon et al., Citation2019; NCISH, Citation2014; Pearson et al., Citation2009), with research supporting that men endure proportionally greater mental distress before they engage in help-seeking behaviour (Biddle et al., Citation2004). In addition, less primary consultation has been found to occur closer to the time of suicide (Luoma et al., Citation2002; Pearson et al., Citation2009), with one study finding that 56% of men contacted their GP in the three months preceding their suicide or undetermined death, and fewer still one month prior to their suicide or undetermined death (38%) (Stanistreet et al., Citation2004). Many of the men consulted for physical issues but there were significantly more consultations for psychological issues for the men who died by suicide (p = 0.005). Recent research suggests that for those men who do communicate suicidal distress, service provision is lacking, particularly within community settings (Pearson et al., Citation2009; Saini et al., Citation2010, Citation2016, Citation2018).

Previous findings suggest that existing suicide prevention services are incompatible with the needs and preferences of men who are experiencing suicidal distress (Pearson et al., Citation2009; Saini et al., Citation2010, Citation2016, Citation2018). This adds further to the research evidence suggesting suicide prevention interventions should be tailored to suit the specific needs of their targeted audience (Lynch et al., Citation2018; Zalsman et al., Citation2016). Recent research has suggested that men have a greater need to receive support from a trusted individual, preferably in an informal setting (CPHC, Citation2019; Struszczyk et al., Citation2019). Facilitating rapid access to a community-based centre could overcome problems associated with poor help-seeking behaviours and communication of suicidal distress among men. It would also offer the desired informal setting which would be a much-needed lifeline to men in suicidal crisis that cannot be provided by conventional primary care or emergency departments.

Brief psychological interventions have been shown to be effective in the prevention of suicide (Cheshire et al., Citation2016; McCabe et al., Citation2018; Saini, Kullu, et al., Citation2020). The Atlas Men’s Well-being Programme was designed to be “male sensitive”, to provide counselling and/or acupuncture for men suffering from stress or distress. The evaluation demonstrated an under-investigated pathway by which men experiencing mental health problems could be identified in primary care and helped to talk about the problems concerning them, and/or receive physical therapy aimed at reducing stressed-related symptoms. This evaluation highlighted the value of engaging GPs in encouraging stressed/distressed men to identify and seek help for mental health problems (Cheshire et al., Citation2016). McCabe et al. (Citation2018) conducted a systematic review of the effectiveness of four brief psychological interventions conducted in Switzerland, the U.S. and across low and middle-income countries, in addressing suicidal thoughts and behaviour in healthcare settings. The components of the interventions were early therapeutic engagement, information provision, safety planning and follow-up contact for at least 12 months. Of the four trials, two that measured suicidal ideation found no impact, two showed fewer suicide attempts, one showed fewer suicides and one found an effect on depression. Although the evidence base is small, brief psychological interventions appeared to be effective in reducing suicide and suicide attempts, however, all studies were conducted with people who had attended the Emergency Department and not in other settings. However, these interventions were not conducted in the UK and may not be generalisable. While some studies have reported promising findings on early engagement and brief psychological therapeutic interventions being particularly beneficial for positive improvements in psychological well-being including suicidal ideation (McCabe et al., Citation2018), anxious mood and stress (Cheshire et al., Citation2016), there remains a paucity of evaluative studies that consider the effectiveness of the implementation of suicide prevention programs targeted towards men. Subsequently, a knowledge gap between what researchers and practitioners reliably know works in suicide prevention interventions for men in a community setting exists. Research suggests that brief psychological models may be effective in reducing suicidal crisis, however, to date this has only been shown within hospital settings (Brown et al., Citation2020; McCabe et al., Citation2018) and more research is needed within community settings. This paper aims to evaluate the effectiveness of James’ Place, an innovative suicidal crisis centre and the first of its kind in the UK. The study further aimed to conduct a social value assessment of the service to provide an understanding of the potential social, economic and environmental impact of James’ Place. Uniquely this service delivers a clinical intervention within a community setting for men in suicidal crisis.

Methods

Participants

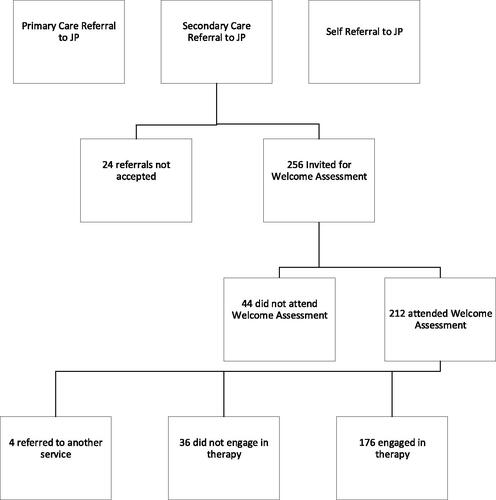

This is a case series study of men experiencing a suicidal crisis who had been referred to the James’ Place Service between 1 August 2018 and 31 July 2019 (n = 265). Referrals came from Secondary Care, Primary Care or self-referrals. An “other” category was also created which consisted of referrals from voluntary organisations and charities. Adherence to treatment includes men attending a welcome assessment and at least one session of therapy. Those who only attended a welcome assessment and did not have any further sessions were classed as incomplete.

The James’ Place model

James’ Place is a community-based service delivering a clinical intervention for men in crisis based in a house in Liverpool, North West of England. The therapeutic service started in August 2018, and this study includes those referred to James’ Place within its first year. The centre is the first of its kind in the UK, delivering suicide prevention by trained therapists with an emphasis on co-producing the therapeutic intervention together with the service user. James’ Place aims to deliver an intervention based on three theoretical models: Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner et al., Citation2009), The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS; Jobes, Citation2012) and The Integrated Motivational-Volitional Theory of Suicide (IMV; O'Connor, Citation2011; O'Connor & Kirtley, Citation2018). All three models seek to explain suicidal behaviour in an individual or group and suggest ways in which individuals at risk of suicide can be treated and which interventions could be helpful. The commonality of the above approaches is the process of working alongside the suicidal person to understand why they have become suicidal and work towards co-producing effective suicide prevention strategies that may help them in coping with similar distress in the future. The James’s Place model is familiar to those of a “Crisis Resolution” model (Department of Health, Citation2001). The difference is that James’ Place supports men who are experiencing a suicidal crisis and who do not need to have been diagnosed with a serious mental health problem (e.g. Severe Depressions, Bipolar Disorder, Psychotic Illness, Personality Disorder) to receive therapy. In common with the CAMS model, the therapists offer a range of therapeutic approaches and interventions but focus upon decreasing suicidal distress and supporting the men to develop greater resilience and coping strategies.

The model includes nine sessions of therapy in three lots of three. The first three sessions are given over the first week and typically involve the assessment formulation stage where therapists assess the risk of the men, collaboratively, with a safety plan. The first stage is about managing the risk, making sure the men are safe and engaged in the talking therapy. The “Lay your Cards on the Table” model is introduced within the first three sessions to aid conversation and visually display how the men are being affected by their suicidal thoughts. The middle part lasts over 10 days and is more person-centred. The therapists may conduct brief psychological intervention if someone is struggling with negative beliefs about themselves or unhelpful cognitions. This may include behavioural activation, relaxation with someone who is really struggling with anxiety, or sleep hygiene. The final three sessions will typically consist of relapse prevention and going through a very in-depth safety plan, making sure that the men know the progress they have made and they know what has actually helped them. That could be using the cards, getting all the cards out and looking at what has been useful and what has not been useful. Looking at that person’s early warning signs and what is a sign for them when they are going downhill again. Planning with them for that scenario, so a lapse is less likely to turn into a relapse. More detailed outcomes for the service are available in two published reports (Saini et al., Citation2019; Saini, Chopra, et al., Citation2020).

Partnerships across the city enabled men to be referred to James’ Place from ED, Primary Care, local universities or via self-referrals. Clients were offered the James’ Place model that included ∼10 sessions of therapy; however, the number fluctuated dependent on each client’s individual needs. Experienced therapists who were trained to deliver the James Place model provided sessions.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

CORE-34 Clinical Outcome Measure (CORE-OM; Core System Group, Citation1998). The CORE-OM is a client self-report questionnaire, which is administered before and after therapy. The client was asked to respond to 34 questions about how they have been feeling over the last week, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” (0) to “most of the time” (4). Eight items are reverse scored. The 34-items cover four dimensions; subjective well-being (four items), problems/symptoms (12 items), life functioning (12 items) and risk/harm (six items), producing an overall score called the global distress (GD) score. Comparison of the pre and post-therapy scores offer a measure of “outcome” (i.e. whether or not the client's level of distress has changed, and by how much).

CORE-OM data are routinely collected by psychological therapy services (Beck et al., Citation2015). Recent research has shown that participants find the CORE-OM useful in assessing psychological distress and progress within treatment (Paz et al., Citation2020).

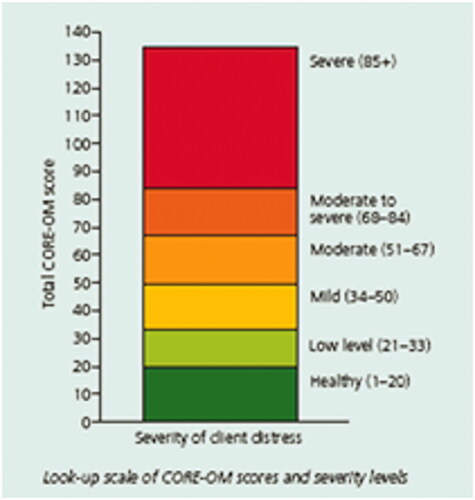

The measure shows good reliability and convergent validity with other measures used in psychiatric or psychological settings (Barkham et al., Citation2005; Evans et al., Citation2002). Connell et al. (Citation2007) published benchmark information and suggested a GD score equivalent to a mean of 10 or above was an appropriate clinical cut-off, demonstrating a clinically significant change, while a change of ≥5 was considered reliable (see ).

Secondary outcomes

A range of psychological, motivational and volitional factors that play a role in suicidality was assessed by the therapist during each session. These were informed by leading evidence-based models of suicidal behaviour, which the James’ Place model is based upon. Therapists received training on how these factors should be assessed and recorded by the service. When men discussed factors, such as “feeling trapped”, “being a burden” or “lack of ‘social support’” these would be recorded in their case file at each session. In addition, the referrer to the service and the precipitating factors the referrer attributed to the suicidal crisis were recorded. With regards to the secondary outcomes, therapists were trained on recognising the outcomes to reduce subjectivity and recorded this information at the time of consultation thus reducing recall bias. Feedback was sought from men once discharged from the service via an anonymised questionnaire.

It should be noted that some of the secondary outcomes are subjective due to referrer or therapist interpretation. Additionally, the men often completed the CORE-OM in the presence of the therapist which may have caused further interpretation bias. However, the sessions at James’ Place provided an environment where clients felt comfortable and at ease, reducing any sense of pressure. With regards to the secondary outcomes, therapists were trained on recognising the outcomes to reduce subjectivity and recorded this information at the time of consultation thus reducing recall bias.

Statistical methods

Our sample size was predetermined based on the number of men who used the service in the first year. Data were analysed using SPSS 26. To examine client outcomes repeated measures general linear models were used to compare pre- and post-treatment data. Correlational analysis was used to determine the association between the precipitating factors and the levels of general distress at the initial assessment. An Anova was used to determine any differences between referrer sources on levels of distress at the initial assessment. t-Tests were conducted to examine differences in general distress between those with and without each precipitating factor. The magnitude of effect sizes (r) was established using the Cohen criteria for r of 0.1 = small effect, 0.3 = medium effect and 0.5 large effect.

Clinical records from the service were available for the entire sample. However, the records only captured entries made in clinical records; unrecorded clinical activity or missing information from referral documents therefore unavailable. For the purposes of this study, only the presence of each factor within each client’s clinical records was used for the analysis. It is possible this strategy may have led to the underestimation of some factors, for example, sexual orientation.

Patient and public involvement

The James’ Place Centre was originally conceptualised by the bereaved parents of a young man aged 20 years old who was attending university at the time of his death. In consultation and co-production with academics, clinicians, commissioners, public health, researchers, therapists, psychologists and experts-by-experience, the centre was designed and implemented. All members of the centre design team were involved in finalising the outcome measures developed for the James’ Place model and these were informed by their priorities, experience and relevance. The research question was developed through a collaboration involving the James’ Place Research Steering Group who oversees all the research taking place at the centre. The group includes commissioners, clinicians, academics, researchers, therapists, James’ Place Charity Trustee members and experts-by-experience. Experts-by-experience is men who have personal experience of being in a suicidal crisis or those who have been bereaved by male suicide. Experts-by-experience were involved in a series of meetings when setting up the service and are members of the Research Steering Group. Members of both groups will be involved in choosing the methods and agreeing with plans for the dissemination of the study to ensure that the findings are shared with wider, relevant audiences within the field, particularly as some members are part of the National Suicide Prevention Alliance and The National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration. JB was involved in the development, writing and submission of the paper as a Clinical Lead and Expert-by-Experience.

Results

Between 1 August 2018 and 31 July 2019, James’ Place received 265 referrals from ED, Primary Care, Universities or self-referrals. Of those, 212 (80%) attended a welcome assessment and 176 (83%) went on to engage in therapy (see ). For those who did not attend the welcome assessment, the reason was usually no response when the men were followed up or some said they were not feeling suicidal anymore. The mean age was 33 years (range 18–61 years). Baseline characteristics of the men are given in . In terms of ethnicity, relationship status, sexual orientation, employment status and the CORE-OM, no significant differences were noted for the men. One-hundred and thirty-seven (78%) men completed the CORE-OM at assessment, and 60 (34%) completed it following discharge from the service. Both the assessment and discharge CORE-OM measure was completed by 56 (32%) men.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the men attending for therapy.

CORE-34 clinical outcome data (CORE-OM)

The mean general distress score for the assessment CORE-OM (N = 137) was 85.50 (SD 19.24). Men scored highest on problem symptoms [M = 35.27 (7.52)] and the life functioning domain [M = 26.04 (7.57)]. Men had a mean score of 12.16 (2.88) on subjective well-being, and a mean score of 9.55 (4.68) on risk/harm.

For those who completed both the assessment and discharge CORE-OM (N = 56), all subscales of the CORE-OM showed a statistically significant reduction in mean scores between assessment and discharge, with all outcomes demonstrating a large effect size (see ). Results found that for risk/harm and subjective well-being, there was a clinically significant change, with mean scores reducing to under 10, indicating a level of distress classed as healthy. Problems/symptoms and life functioning demonstrated a reliable change with a reduction of more than five in the clinical distress scores following therapy.

Table 2. CORE-OM scores for those with assessment and discharge measures (N = 56).

Referrals into the service

shows the referral details for men who were seen at the James’ Place Service for a welcome assessment over year one (N = 212). Men were referred from a variety of places. Most of the referrals came from mental health practitioners (35%) based in Emergency Departments, 16% were from GPs, 8% via self-referral and nearly a third were not specified (see ). There was no significant relationship between the source of referral and the level of distress at the initial assessment (p = 0.19, η2 = 0.02).

Table 3. Referrer details for men referred into the James’ Place service.

Precipitating factors for men help-seeking in suicidal crisis

presents the precipitating factors related to the current suicidal crisis the men were in at the time of referral into the James’ Place Service. Precipitating factors to the crisis were recorded by the referrer. The most common factors were relationship breakdown (44%), family problems (including domestic abuse) (43%), work (30%), debt (including financial distress) (26%), Bereavement (22%), alcohol misuse (18%), drug misuse (16%) and university stress (14%). There was no relationship between the precipitating factors and the levels of general distress found at the initial assessment (p > 0.05). Additionally, t-tests demonstrated no significant differences in general distress between those with and without each precipitating factor (p > 0.05).

Table 4. Correlations and t-tests between precipitating factors and initial levels of distress.

The psychological factors that affect men the most were also explored. The most common included hopelessness (91%), social isolation (86%), rumination (81%), social support (79%), thwarted belongingness (75%), entrapment (74%), humiliation (71%), past suicide attempts or self-harm (70%) and impulsivity (68%).

Feedback from men using the service

One-fifth of the men (18%; 39/212) who used the service completed feedback questionnaires on their experience of the service. Feedback suggested that men found the service useful and importantly, that it had provided support and help for them at a time when they were in a suicidal crisis. Overall, there was no negative feedback from men using the service in the first year. A report by Saini, Chopra, et al. (Citation2020) demonstrated how James’ Place is seen to provide men with somewhere safe and welcoming, a therapeutic setting where they felt that they were supported, and were encouraged to talk about their problems and find solutions. The support and therapy they received appeared to increase their awareness to understand their own thoughts and feelings, and they were able to adopt coping strategies and all of this in turn had a positive impact on their mental health and their thoughts around suicide and 16 wanting to act on these. A small number of the men also spoke about experiencing improved relationships with family. Most of the men spoke about being in suicidal crisis and that they were not sure where they would have gone for help if James’ Place was not there and that they may not have survived (see Box 1 and Saini, Chopra, et al., Citation2020 for more detailed information).

Box 1. Quotes from men on their experience of the James’ Place Service (Saini, Chopra, et al., Citation2020). “Thank you for everything you have done for me and a special thank you to [therapist name] who’s been a great help (getting there slowly).” “It was good to talk feel listened to and feel I could be open and honest.” “I really feel lucky to have such amazing help and support from James’ Place the first moment I walked in I felt safe.” “I felt I noticed my progress and didn’t really need to be informed however, signs were pointed out.” “I really appreciate everything James’ Place has done for me. I feel so much better now, then I have in a long time.” “The environment and friendly atmosphere helped me be open with my issues.” “I’ve not felt this safe and good in years.” “[Therapist name] was wonderful, she has helped me massively and I can’t thank her enough.” “Everyone was very friendly and understanding and the support I received was very good.” “I feel like I have a purpose.” “Understanding and caring and not judgemental or bias, which was good.” “The quality is outstanding.”

Discussion

Main findings

To our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of a clinical intervention delivered within a community setting for men in suicidal crisis. A significant reduction in general distress from assessment to discharge was found. A clinically significant change for subjective well-being and risk of harm subscales and a significant reliable change in levels of problems/symptoms and life functioning were reported. In addition, the findings relating to the psychological, motivational and volitional factors offer further support for the utility of the IMV model (O'Connor, Citation2011; O'Connor & Kirtley, Citation2018), CAMS (Jobes, Citation2012) and Joiner et al.’s (Citation2009) model for understanding suicidal behaviour. Men commonly reported many of the key factors in these models at the time of their suicidal crisis (e.g. feelings of defeat, entrapment, thwarted belongingness, hopelessness, humiliation, social isolation and experiences of rumination). With regard to precipitating factors of the suicidal crisis, our research supports that social aspects which increase suicide risk, particularly for men, such as relationship breakdown and family problems (Corcoran & Nagar, Citation2010; Kposowa, Citation2003; Milner et al., Citation2012; Scourfield & Evans, Citation2015), being the most common factors within our sample. Overall, the study has demonstrated the benefits of rapid access tailored intervention for men in suicidal crisis.

Strengths and limitations

This research has several key strengths, with James’ Place being the first community-based therapeutic suicide prevention centre in the UK. In addition, this has been the first study to access men at the time of their suicidal crisis. Its novel and timely findings can inform future service implementation to reach a male population group that is at high risk of suicide (Struszczyk et al., Citation2019) and who are less likely to seek help (Biddle et al., Citation2004); thus filling an important gap in service provision that traditional care pathways are not always able to reach.

A further strength is that this research has helped to inform and enhance the service. On-going monitoring of the service since its inception has allowed evaluative evidence accrued through a collaborative partnership with key stakeholders (including therapists, researchers and service users) to be communicated and implemented (Saini et al., Citation2019; Saini, Chopra, et al., Citation2020). By employing and actively engaging the principles of co-production (e.g. Slay & Stephens, Citation2013) this collaborative partnership has allowed processes within the service to be strengthened in preparation for the second year of the service running. Consistent with co-production principles, James’ Place seeks to collaborate and draw upon the knowledge and expertise of its diverse stakeholders within a mutually equitable relationship (Boyle & Harris, Citation2009). Implementing coproduction within this way has been shown to improve outcomes and strengthen service delivery within mental health settings by increasing access, facilitating early intervention, cost-effectiveness, community engagement and reach (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Citation2019; Slay & Stephens, Citation2013), while being responsive to the individual needs of a community. Importantly this research provides an ongoing evidence base for a potentially life-saving intervention and informs current and future developments, including the planned national growth of this service.

However, these findings should be interpreted in the context of some methodological limitations. The first issue is that of missing data. Whilst this is to be expected due to attrition and establishing processes in the first year of running a new service, it has been a valuable learning point for improving the service going forward. Having monitoring and evaluation built into the service from the start has enabled timely evidence and data to be fed back. This had led to the implementation of clinical data systems; thus providing evidence for the need of funding a costly resource to improve data collection. The absence of psychometric measures for the secondary outcome measures has limited the level of mapping of the psychological factors as we have only been able to use binary “yes/no” answers. Future studies should include using more measures to collate this data, however, this can be challenging to collate in a service where service users are in suicidal distress and potentially may become overwhelmed.

With regard to sampling, it is important to note that only records for men who were seen by the service were sampled, therefore the results may not reflect the information for men who did not have contact with the service who may also have been in suicidal crisis. Thus, it is difficult to draw firm aetiological conclusions from this data. This, however, was a deliberate decision in the design phase of this study, as one of the main aims was to examine the pilot stage of the feasibility of the service. This was to ensure that the relevant population of men was being referred into the service and that the service being provided was efficient and safe for men in helping to reduce their suicidal distress. Due to the significant reduction in clinical risk for most of the men who used the service, we think these findings are even more striking.

Another limitation is the absence of a control group. Comparative data would highlight how these men’s outcomes compare to men receiving other, or no, treatment (or those that drop out of treatment). However, due to ethical issues around the safety of people placed in a control group, comparator studies are more difficult to conduct within suicide research (Fisher et al., Citation2002). Additionally, it is important to note that suicidal distress can typically reduce overtime in the absence of effective treatments, thus the reduction in suicidal distress may not all be attributed to the intervention. However, this is not to say that the program is ineffective but that the data are not sufficiently rigorous to establish the degree to which it is effective. However, in-depth qualitative feedback from men who have used the service suggests that the rapid access, environment and therapy all played a significant role in the reduction of their suicidal distress (Saini, Kullu, et al., Citation2020).

This study was conducted in service in the North-West of England. Therefore, care must be taken when attempting to generalise these findings to other geographical regions. This region is reported to have the highest rate of suicides in the UK (ONS, Citation2019b) which may have influenced the study findings when comparing to regions where the suicide rate is much lower. The higher rates of suicide may be reflective of the health inequalities reported by the Public Health England (PHE) report (Powell, Citation2021). The life expectancy across this region is lower compared to that of most of England; thus increasing the importance of such interventions. Previous research has demonstrated that the provision of community-based services for those in suicidal distress is lacking (Pearson et al., Citation2009; Saini et al., Citation2010, Citation2016, Citation2018). The findings of the current study support that this type of service provision within a community setting can play a significant role in reducing suicidality.

Conclusion

Our results support the use of the James’ Place Model for men in suicidal distress to aid in potentially preventing suicides in this high-risk group of the population. Coproduction between suicide prevention experts, service users and relevant social and health professionals in the design and implementation of community-based tailored crisis services for men should be an essential part of any suicide prevention strategy. Future research needs to assess the long-term effects of the model to understand whether the effects of the therapy are sustainable over a period of time following discharge from the service.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Liverpool John Moores University (Reference: 19/NSP/057) and written consent was gained from men using the service at their initial welcome assessment.

The lead author affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Author contributions

P.S., J.C. and J.B.: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work. P.S., J.C., C.H., B.H., H.T. and J.B.: acquisition of the data. P.S., J.C. and J.B.: data extraction. J.C.: statistical analyses. All authors: interpretation of the data. P.S., C.H. and J.C.: drafting the work. All authors: revising it critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. P.S. and J.B. act as guarantors.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities

The study findings will be disseminated via conference presentations, press releases and social media. A companion qualitative article will serve to further stimulate discussion on the research. The authors will also disseminate findings to media organisations and press councils, and also national and international suicide prevention alliances. The wider public will be informed via media and in lectures and seminars on suicide prevention that target the broader public. Discussions on how the findings will be used to the benefit of the community will involve media professionals, individuals with personal experience of suicidal ideation or suicide attempt, individuals with experience of bereavement from suicide, mental health professionals and the broader interested public.

Disclosure statement

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work; P.S. has received research grants from the James’ Place Charity, J.B. has been paid for developing and delivering the James’ Place Model; no other relationships or activities could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from James’ Place. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the corresponding author with the permission of James’ Place.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barkham, M., Gilbert, N., Connell, J., Marshall, C., & Twigg, E. (2005). Suitability and utility of the CORE-OM and CORE-A for assessing severity of presenting problems in psychological therapy services based in primary and secondary care settings. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 239–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.186.3.239

- Barzilay, S., & Apter, A. (2014). Psychological models of suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 18(4), 295–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.824825

- Beck, A., Burdett, M., & Lewis, H. (2015). The association between waiting for psychological therapy and therapy outcomes as measured by the CORE-OM. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 233–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12072

- Biddle, L., Gunnel, D., Sharp, D., & Donavan, J. L. (2004). Factors influencing help seeking in mentally distressed young adults: a cross sectional survey. British Journal of General Practice, 54, 248–253.

- Blasco-Fontecilla, H., Rodrigo-Yanguas, M., Giner, L., Jose Lobato-Rodriguez, M. J., & de Leon, J. (2016). Patterns of comorbidity of suicide attempters: An update. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18, 93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0733-y

- Boyle, D., & Harris, M. D. (2009). The Challenge of Co-Production. How Equal Partnerships between Professionals and the Public Are Crucial to Improving Public Services; National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts [NESTA]. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/the_challenge_of_co-production.pdf

- Brown, S., Iqbal, Z., Burbidge, F., Sajjad, A., Reeve, M., Ayres, V., Melling, R., & Jobes, D. (2020). Embedding an evidence-based model for suicide prevention in the National Health Service: A service improvement initiative. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 4920. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17144920

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Injury prevention and control: Suicide prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/suicide

- Champs Public Health Collaborative. (2019). Community-based mental health and suicide prevention interventions for men. Rapid Evidence Review. Retrieved May 10, 2021, from https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/nccmh/suicide-prevention/monthly-clinic/champs-eitc-rapid-review-comm-mens-health-programmes.pdf

- Cheshire, A., Peters, D., & Ridge, D. (2016). How do we improve men's mental health via primary care? An evaluation of the Atlas Men's Well-being Pilot Programme for stressed/distressed men. BMC Family Practice, 17(1), 13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0410-6

- Connell, J., Barkham, M., Stiles, W. B., Twigg, E., Singleton, N., Evans, O., & Miles, J. N. V. (2007). Distribution of CORE-OM scores in a general population, clinical cut-off points and comparison with the CIS-R. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 69–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017657

- Corcoran, P., & Nagar, A. (2010). Suicide and marital status in Northern Ireland. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(8), 795–800. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0120-7

- Core System Group. (1998). CORE System (Information Management) Handbook. Leeds University of Leeds.

- Department of Health. (2001). Crisis resolution/home treatment teams: The mental health policy implementation guide.

- Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., Mellor‐Clark, J., McGrath, G., … Audin, K. (2002). Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 51–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.1.51

- Fisher, C., Pearson, J., Kim, S., & Reynolds, C. (2002). Ethical issues in including suicidal individuals in clinical research. IRB, 24(5), 9–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3563804

- Harris, E. C., & Barraclough, B. (1997). Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 205–228. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.170.3.205

- Hartley, D. P., & Petersen, D. R. (1993). Metabolic interactions of 4-hydroxynonenal, acetaldehyde and glutathione in isolated liver mitochondria. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 328, 27–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-2904-0_4

- Jobes, D. A. (2012). The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS): An evolving evidence-based clinical approach to suicidal risk. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(6), 640–653. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00119.x

- Joiner, T. E., Jr., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., & Rudd, M. D. (2009). The interpersonal theory of suicide: Guidance for working with suicidal clients. American Psychological Association.

- Kim, J. L., Kim, J. M., Choi, Y., Lee, T.-H., & Park, E.-C. (2016). Effect of socioeconomic status on the linkage between suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 46(5), 588–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12242

- Kposowa, A. J. (2003). Divorce and suicide risk. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57(12), 993–995. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.12.993

- Kposowa, A. J., Breault, K. D., & Singh, G. K. (1995). White male suicide in the United States: A multivariate individual-level analysis. Social Forces, 74(1), 315–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/74.1.315

- Luoma, J. B., Martin, C. E., & Pearson, J. L. (2002). Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: A review of the evidence. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(6), 909–916. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909

- Lynch, L., Long, M., & Moorhead, A. (2018). Young men, help-seeking, and mental health services: Exploring barriers and solutions. American Journal of Men's Health, 12(1), 138–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988315619469

- Mallon, S., Galway, K., Rondon-Sulbaran, J., Hughes, L., & Leavey, G. (2019). When health services are powerless to prevent suicide: Results from a linkage study of suicide among men with no service contact in the year prior to death. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 20(e80), e80–e86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423619000057

- McCabe, R., Garside, R., Backhouse, A., & Xanthopoulou, P. (2018). Effectiveness of brief psychological interventions for suicidal presentations: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1663-5

- Milner, A., McClure, R., & De Leo, D. (2012). Socio-economic determinants of suicide: An ecological analysis of 35 countries. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0316-x

- Möller-Leimkühler, A. M. (2002). Barriers to help-seeking by men: A review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 71(1–3), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00379-2

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. (2019). Working well together: Evidence and tools to enable co-production in Mental Health Commissioning.

- National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Mental Health. (2014). The National Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness Annual Report. Retrieved from http://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=37594

- National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Mental Health. ( 2018). Annual Report 2018: England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Retrieved from https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/reports/annual-report-2018-england-northern-ireland-scotland-and-wales/

- O'Connor, R. C. (2011). The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 32(6), 295–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000120

- O'Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B Biological Sciences, 373(1754), 20170268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2019a). Suicides in the UK: 2018 Registrations. Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2018registrations

- Office for National Statistics. (2019b). Suicides in England and Wales: 2019 registrations. Retrieved March, 2021, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2019registrations

- Paz, C., Adana-Diaz, L., & Evans, C. (2020). Clients with different problems are different and questionnaires are not blood tests: A template analysis of psychiatric and psychotherapy clients’ experiences of the CORE-OM. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 20(2), 274–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12290

- Pearson, A., Saini, P., Da Cruz, D., Miles, C., While, D., Swinson, N., Williams, A., Shaw, J., Appleby, L., & Kapur, N. (2009). Primary care contact prior to suicide in individuals with mental illness. The British Journal of General Practice, 59(568), 825–832. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X472881

- Pirkis, J., Spittal, M. J., Keogh, L., Mousaferiadis, T., & Currier, D. (2017). Masculinity and suicidal thinking. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(3), 319–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1324-2

- Powell, L. (2021, March). Health inequalities dashboard: Statistical commentary. Retrieved April 2, 2021, from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/health-inequalities-dashboard-march-2021-data-update/health-inequalities-dashboard-statistical-commentary-march-2021

- Saini, P., Windfuhr, K., Pearson, A., Da Cruz, D., Miles, C., Cordingley, L., While, D., Swinson, N., Williams, A., Shaw, J., Appleby, L., & Kapur, N. (2010). Suicide prevention in primary care: General practitioners' views on service availability. BMC Research Notes, 3(246), 246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-3-246

- Saini, P., Chantler, K., & Kapur, N. (2016). General practitioners' perspectives on primary care consultations for suicidal patients. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(3), 260–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12198

- Saini, P., Chantler, K., & Kapur, N. (2018). GPs' views and perspectives on patient non-adherence to treatment in primary care prior to suicide. Journal of Mental Health, 27(2), 112–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1294736

- Saini, P., Whelan, G., & Briggs, S. (2019, March). Qualitative Evaluation Six Months Report: James’ Place Internal Evaluation. Liverpool John Moores University.

- Saini, P., Chopra, J., Hanlon, C., Boland, J., Harrison, R., & Timpson, H. (2020, October). James’ Place Internal Evaluation: One-Year Report. Liverpool John Moores University. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.jamesplace.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/James-Place-One-Year-Evaluation-Report-Final-20.10.2020.pdf

- Saini, P., Kullu, C., Mullin, E., Boland, J., & Taylor, P. (2020). Rapid access to brief psychological treatments for self-harm and suicidal crisis. The British Journal of General Practice, 70(695), 274–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X709913

- Scourfield, J., & Evans, R. (2015). Why might men be more at risk of suicide after a relationship breakdown? Sociological insights. American Journal of Men's Health, 9(5), 380–384. https://journals.sagepub.com/home/jmh https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988314546395

- Slay, J., & Stephens, L. (2013). Co-production in mental health: A literature review. London: New Economics Foundation. https://b.3cdn.net/nefoundation/ca0975b7cd88125c3e_ywm6bp3l1.pdf

- Stanistreet, D., Gabbay, M. B., Jeffrey, V., & Taylor, S. (2004). The role of primary care in the prevention of suicide and accidental deaths among young men: An epidemiological study. The British Journal of General Practice, 54(501), 254–258.

- Struszczyk, S., Galdas, P. M., & Tiffin, P. A. (2019). Men and suicide prevention: A scoping review. Journal of Mental Health, 28(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1370638

- Turecki, G., & Brent, D. A. (2016). Suicide and suicidal behaviour. The Lancet, 387(10024), 1227–1239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00234-2

- WHO. (2019a). Suicide data. Retrieved September 9, 2019, from http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/

- WHO. (2019b). Male: female suicide ratio. Retrieved September 9, 2019, from http://www.who.int/gho/mental_health/suicide_rates_male_female/en/

- Yoshimasu, K., Kiyohara, C., Miyashita, K., & Stress Research Group of the Japanese Society for Hygiene (2008). Suicidal risk factors and completed suicide: Meta-analyses based on psychological autopsy studies. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 13(5), 243–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-008-0037-x

- Zalsman, G., Hawton, K., Wasserman, D., van Heeringen, K., Arensman, E., Sarchiapone, M., Carli, V., Höschl, C., Barzilay, R., Balazs, J., Purebl, G., Kahn, J. P., Sáiz, P. A., Lipsicas, C. B., Bobes, J., Cozman, D., Hegerl, U., & Zohar, J. (2016). Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-Year systematic review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 646–659. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X