Abstract

Background

Self-rated health (SRH) is a single question with which general health status is assessed.

Aims

To study whether SRH (i) is associated with depression and anxiety symptoms, concurrently and after three years, (ii) predicts the course over time for meeting a cutoff for depression and anxiety, and (iii) predicts development of depression and anxiety after three years.

Method

Population-based questionnaire data from northern Sweden were used. In total, 2336 individuals participated at baseline and three-year follow-up. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale was used to quantify symptoms of depression and anxiety. Categorical and continuous data were used for analyses to complement each other.

Results

Regarding prevalence, the analyses showed three- to four-fold increased odds for depression and anxiety at three-year follow-up, and two- to three-fold odds for their development at three-year follow-up. SRH at baseline was also found to be a significant, but weak, predictor of depression and anxiety severity and worsening at follow-up as well as being a predictor over time for meeting a cutoff for depression and anxiety.

Conclusions

Assessment of SRH may be used in general practice to identify individuals who qualify for further evaluation of depression and anxiety.

Introduction

Mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety, are among the largest contributors to the burden of disease worldwide (Whiteford et al., Citation2013). Globally, 264 million people suffer from depression, which is one of the leading causes of disability, with many of these individuals suffering also from anxiety. A recent WHO (Citation2020) study estimates that depression and anxiety disorders cost the global economy US$1 trillion each year only in lost productivity. Apart from human misery and lost health, the cost for healthcare is extensive. Taking elderly as an example, the excess annual adjusted healthcare costs of depression, anxiety and their comorbidity is estimated to $27.4, $80.0, and $119.8 million, respectively, per 1,000,000 population of elderly community-dwelling adults (Vasiliadis et al., Citation2013). The high cost for comorbidity can be explained by depression and anxiety being strong bidirectional risk factors for one another (Jacobson & Newman, Citation2017). The high impact of depression and anxiety calls for identification of early and easily assessable risk factors for its prevention.

Self-rated health (SRH), also referred to as self-assessed, self-perceived and self-evaluated health, gained considerable interest in the late 1970s when having been shown to predict mortality (Jylhä, Citation2009). SRH is typically conducted by having the individual evaluate his/her general health status on a 5- or 7-point scale, ranging from poor to excellent health (Eriksson et al., Citation2001). Its predictability for mortality remains when adjusting for comorbidity and functional status (Idler & Benyamini, Citation1997; Ganna, & Ingelsson, Citation2015), implying that SRH provides valid and important information about an individual’s general health status (Jylhä, Citation2009). SRH is probably the most feasible and inclusive measure of health status, as it captures elements of health not captured by more guided questions (Jylhä, Citation2009). Consequently, SRH is assessed in studies across multiple disciplines, including psychology, sociology, public health and epidemiology (Graf & Hicks Patrick, Citation2016). However, the formulation of the SRH item provides little guidance as to what the individual may be thinking of when assessing the general health status.

Recent research has demonstrated various factors that may impact SRH: income/social class, education level, gender roles, employment status, healthy lifestyle, health literacy, marital status and age (Aydin, Citation2020; Baćak, Citation2018; Cui et al., Citation2020; Hu et al., Citation2016; Levin-Zamir et al., Citation2016; Mazeikaite et al., Citation2019; Präg, Citation2020; Storey et al., Citation2020; Willerth et al., Citation2020). Regarding age, young adults tend to consider a broader range of criteria, including performance of healthy behavior and engagement in age-appropriate activities, whereas old adults draw mainly on physical, functional and mental-health criteria when considering SRH (Graf & Hicks Patrick, Citation2016). Work-related aspects of importance for SRH include working hours and unemployment or being disabled/retired (Jeon et al., Citation2020; Jurewicz & Kaleta, Citation2020), and in a broad sense also daily hassles, stressful significant life events and self-esteem (Graf et al., Citation2017; Jafflin et al., Citation2019).

As expected, serious chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes are considered strongly when reporting one’s SRH, in particular in cases of comorbidity (Kaneva et al., Citation2018). However, the psychological factors underlying poor SRH are multifaceted. For example, illness perception was in cardiac patients found to account for 16.2% of their SRH, and health complaints for another 14.2% (Chiavarino et al., Citation2019). Au and Johnston (Citation2014) showed that vitality, followed by ill-health limiting mobility and pain are important determinants of SRH.

Vitality is closely related to depression and anxiety (Lindeberg et al., Citation2006). Extent to which SRH is related to depression and anxiety is complicated by the fact that psychological factors (e.g. response style) may affect assessment of health. Two pathways for the relation between psychological processes and SRH have been suggested: (1) psychological aspects are part of or correlate with health in general, and (2) psychological dispositions affect the assessment process itself. An example of the latter is that SRH, at least partly, reflects the attitude to one’s health, such as pessimism (Ferraro et al., Citation1997). Cross-sectional studies of depression and anxiety have in certain subgroups shown associations with poor SRH (e.g. Balázs et al., Citation2018; Han et al., Citation2018; Levola et al., Citation2020), although such studies of the general population appear to be lacking.

SRH has been shown to be associated with change over time in a number of chronic diseases, sociodemographic factors and health styles, effects of country and regional health system and declared symptoms (Becchetti et al., Citation2018). However, prior results are not fully consistent in their ability to predict depression and anxiety, which so far has been conducted in the elderly population. De Beurs et al. (Citation2001) reported that SRH predicts prevalence of depression and anxiety as single conditions, but not as a comorbid state, whereas Chou et al. (Citation2011) later reported that poor SRH predicts development of depression, but not anxiety. In yet another study of elderly, SRH was found to predict persistence of major depressive symptoms over a one-year period (Thielke et al., Citation2010). With focus instead on prognosis in a primary care cohort with a history of depressive symptoms, Ambresin et al. (Citation2014) reported that SRH predicts the risk of future depressive symptoms up to five years.

The present aim was to understand the roles of depression and anxiety symptoms in SRH in a general adult population, including extent to which SRH can predict development of depression and anxiety. The objectives were to study (1) whether depression and anxiety symptoms, both concurrently and at three-year follow-up, differ in severity between poor and good SRH at baseline, (2) whether the course over a three-year period for meeting a cutoff for depression and anxiety symptoms differs between poor and good SRH, and (3) whether poor SRH at baseline predicts development of depression and anxiety at three-year follow-up. More specifically regarding the second objective, it was investigated whether the courses of (i) consistent depression/anxiety over time, (ii) change from depression/anxiety to no depression/anxiety, (iii) a change from no depression/anxiety to depression/anxiety and (iv) consistent absence of depression/anxiety over time differ in prevalence between poor and good SRH. Whereas the operationalization of the constructs of good vs poor SRH has the advantage of providing easily interpreted results in a clinical context, it was based on a cutoff on the SRH scale, and thus somewhat arbitrary. For this reason, the relations between SRH and depression/anxiety were further investigated with a correlational approach.

Materials and methods

Population and sample

Cross-sectional and longitudinal data were used from the Västerbotten Environmental Health Study (Palmquist et al., Citation2014). A questionnaire was sent by mail to a sample of 8520 individuals aged 18 to 79 years in the County of Västerbotten in northern Sweden. The sample was stratified for age and sex according to the age strata 18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69 and 70–79 years. The baseline data were collected in 2010 and the follow-up data in 2013, at both occasions in March–April. Of the 3406 (40.0%) persons who responded at baseline, 3181 were still alive and living in Västerbotten in 2013. Of these, 2336 (73.4%) responded at follow-up.

SRH was measured with the single item “In general, how would you describe your health?” for which the participant was asked to rate his/her general health on a five-point scale with the response alternatives poor, fair, good, very good and excellent. At baseline, 61 participants rated their health as poor, 545 as fair, 789 as good, 679 as very good and 238 as excellent, whereas 24 did not respond to the SRH question and were therefore excluded from further analysis. Following a large number of prior studies (Idler & Benyamini, Citation1997), the responses were categorized into two groups: “poor” and “fair” were referred to as poor SRH (n = 606) and “good”, very good,” and “excellent” were referred to as good SRH (n = 1706) at baseline. The three shades of positive response alternatives were used (as opposed to two positive, one neutral and two negative alternatives) as it well captures inter-individual variability in high-income countries with high prevalence of good general health (Cullati et al., Citation2020), such as Sweden. The two groups are described in with respect to demographics, physical exercise and self-report of having received a physician-based diagnoses. Whereas the poor and good SRH groups did not differ significantly regarding sex distribution, they differed with respect to age, education, married/living with partner and physical exercise, which were regarded as confounding variables. The poor SRH groups consisted also to a larger proportion of individuals with various physician-based diagnoses of relevance for depression and anxiety ().

Table 1. Description of the participants with poor and good self-rated health (SRH) at baseline. The groups were compared with t-test for age and chi-square analysis (Fisher’s exact test when n < 5) for the remaining variables.

Assessment of depression and anxiety

The Swedish version (Lisspers et al., Citation1997) of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983) was used to quantify degree of depression and anxiety symptoms. The HADS consists of two subscales, one for depression (HADS-D; e.g. “I have lost interest in my appearance”), and another for anxiety (HADS-A; e.g. “Worrying thoughts go through my mind”), each ranging from 0 to 21 in score (high score representing high level of depression and anxiety). The HADS has good discriminant and concurrent validity and good internal consistency (Bjelland et al., Citation2002; Lisspers et al., Citation1997). Following the recommendation of Morriss and Wearden (Citation1998), a cutoff score of ≥10 on the HADS-D and HADS-A was used for being considered as having symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Procedure

The questionnaire was sent to the participants with the instruction to return it via mail with prepaid postage. Those who did not respond to the first invitation received up to two reminders. Missing data from a participant typically regarded only a small proportion of the items on a particular questionnaire instrument. Imputation was therefore considered a reliable procedure for questionnaire instruments, whereas it was not so regarding single questions. Missing data were therefore estimated for the HADS-D (1.2% at baseline and 1.4% at follow-up) and HADS-A (1.3% at baseline and 1.6% at follow-up), but not for single questions such as the background variables, with multiple imputations using fully conditional Markov chain Monte Carlo methods with 10 maximum iterations by means of which five imputed datasets were created. The estimate values were obtained by pooling the five imputed datasets. The procedure for data collection at baseline and follow-up were identical. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Umeå Regional Ethics Board (Dnr 09-171 M). All participants gave their informed consent to participate.

Statistical analysis

Significant differences in background variables between the groups with poor and good SRH at baseline were tested with independent samples t-test and chi-square analysis. Age, education, married/living with partner, and physical exercise were identified as confounding variables as they differed significantly between groups. One-way analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted to compare the two groups on severity of depression and anxiety at baseline and follow-up, with the confounding variables as covariates. The assumption of normality was met for both SRH groups at both baseline and follow-up for both depression (skewness = 1.21–1.86; kurtosis = 2.02–4.61) and anxiety (skewness = 0.95–1.27; kurtosis = 0.81–1.81).

Chi-square analysis was used to determine whether poor and good SRH at baseline differed with respect to course over time, from baseline to follow-up, for depression and anxiety. Data from baseline and follow-up were used to divide the sample into four groups, which represented all possible courses: Depression/anxiety symptoms at baseline and follow-up, depression/anxiety at baseline only, depression/anxiety at follow-up only and depression/anxiety neither at baseline nor follow-up. Post-hoc, chi-square analysis was used to test differences between the groups on all four courses for both depression and anxiety.

Binary logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine the predictive power of poor SRH at baseline on depression and anxiety at follow-up. Separately for depression and anxiety, and with the group with good SRH at baseline as referents, an odds ratio (OR) was expressed as (i) unadjusted, (ii) adjusted for the confounding variables and (iii) adjusted for the confounding variables and either depression at baseline (for prediction of depression at follow-up) or anxiety at baseline (for prediction of anxiety at follow-up). The former two ORs refer to prediction of prevalence of depression/anxiety, whereas the latter OR refers to prediction of development of depression/anxiety.

Taking on a correlational approach, hierarchical regression analyses were conducted, using continuous data for SRH, depression and anxiety to investigate (i) associations between level of SRH at baseline and severity of depression and anxiety at baseline and follow-up and (ii) the ability of level of SRH at baseline to predict aggravated depression and anxiety severity at follow-up. SRH was placed in a second block in all analyses. Regarding associations, adjustment for the four confounding variables at baseline was conducted by placing them in a first block. Regarding development of depression at follow-up, depression at baseline was placed together with the confounding variables at baseline in a first block, and regarding development of anxiety at follow-up, anxiety at baseline was placed together with the confounding variables at baseline in a first block. This enabled adjustment for the confounding variables and depression or anxiety. As for depression and anxiety, the assumption of normality was met for SRH at baseline (skewness: 1.08, kurtosis: −1.83).

Due to missing values in the confounding variables age (n = 0), education (n = 21), married/living with partner (n = 19) and physical exercise (n = 29), 2264 participants were included in the adjusted logistic regression analyses and the hierarchical regression analyses. The α-level was set at 0.05. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25, Armonk, NY) was used for all analyses.

Results

Associations with depression and anxiety

Mean scores on depression and anxiety controlled for the confounding variables are given in . When controlling for these variables, the poor SRH group showed significantly higher level than the good SRH group on both depression and anxiety at both baseline and follow-up ().

Table 2. Mean (SE) scores on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at baseline and three-year follow-up in the groups with poor and good self-rated health (SRH) at baseline, and results from one-way analyses of covariance when controlled for age, education, married/living with partner and physical exercise.

Results from the hierarchical regression analyses on R2 change and standardized β coefficients for severity of depression and anxiety are given in . When controlling for the confounding variables, SRH at baseline was a significant statistical predictor of depression and anxiety severity at both baseline and follow-up, with R2 change ranging from −0.07 to −0.11 and β coefficients ranging from −0.28 to −0.35.

Table 3. Results from hierarchical regression analyses with self-rated health as statistical predictor at baseline of associations with and development of depression and anxiety.

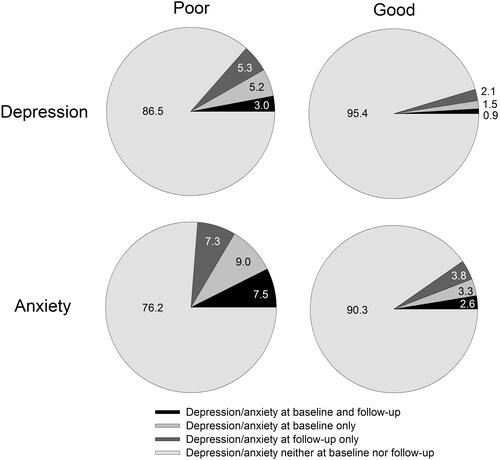

Course over time in depression and anxiety

Distributions of participants across the different courses from baseline to follow-up of meeting the cutoff for depression and anxiety are presented in , separately for the groups with poor and good SRH. The distributions differed significantly between the two groups for depression (χ2 = 55.03, p < 0.001) and anxiety (χ2 = 81.09, p < 0.001). Post-hoc tests showed a significant difference between groups for all four courses for both depression and anxiety (χ2 >12.06, p < 0.001).

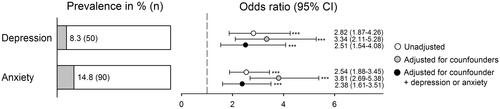

Development of depression and anxiety

Prevalence rates for depression and anxiety at follow-up for the poor SRH group at baseline are shown in . The figure also presents ORs for poor SRH at baseline as a predictor of depression and anxiety at follow-up expressed as (i) unadjusted, (ii) adjusted for confounding variables and (iii) adjusted for confounding variables and either depression or anxiety at baseline. All six ORs differed significantly from unity. When adjusted for confounding variables, the odds for developing depression and anxiety at follow-up was three- to four fold. When adjusted for confounding variables and either depression or anxiety at baseline, the odds was two- to three fold.

Figure 2. Left panel: Prevalence of meeting a cutoff score for symptoms of depression and anxiety at three-year follow-up in the group with poor self-rated health (SRH) at baseline. Right panel: Odds ratios and confidence intervals (CI) for the group with poor SRH when unadjusted, adjusted for confounding variables, and adjusted for confounding variables and depression or anxiety at baseline, with the group with good SRH as referents (***p < 0.001).

R2 change and standardized β coefficients for development of depression and anxiety are presented in . When controlling for the confounding variables, SRH at baseline was a significant statistical predictor of depression and anxiety development at follow-up, with an R2 change of −0.01 and a β coefficients of −0.09 for both depression and anxiety. Thus, the predictive ability of SRH was in this respect very small.

Discussion

The results show that depression and anxiety symptoms differed in severity between poor and good SRH, both concurrently and at three-year follow-up. Thus, compared to the good SRH group, the poor SRH group had significantly higher scores on both the HADS-D and HADS-A at both baseline and follow-up. In accordance, associations between degree of SRH and depression/anxiety severity were supported by results from hierarchical regression analyses. However, the associations according to the regression analyses were very weak. Nevertheless, these results give additional support for concurrent associations between poor SRH and severity of depression and anxiety symptoms (e.g. Balázs et al., Citation2018; Han et al., Citation2018; Levola et al., Citation2020) as well as SRH-based prediction of depression and anxiety symptoms three years later (De Beurs et al., Citation2001). Similar findings have been reported from a primary care cohort with a history of depressive symptoms (Ambresin et al., Citation2014).

The poor and good SRH groups differed in their course over the three-year period for meeting the cutoff for depression and anxiety symptoms. Compared to the good SRH group, a larger proportion of the poor SRH group was showed (i) consistent depression/anxiety over time, (ii) change from depression/anxiety to no depression/anxiety, (iii) change from no depression/anxiety to depression/anxiety, and a smaller proportion showed (iv) consistent absence of depression/anxiety over time. The three-year consistency in depression in this general population is in accordance with a prior report of a one-year consistency among elderly (Thielke et al., Citation2010). Hence, the present result extends this to three years in a general population and includes anxiety as well.

The results also showed that SRH can predict presence of meeting a cutoff for depression and anxiety symptoms. Perhaps even more interesting, when adjusting for depression/anxiety at baseline, the odds were two- to three fold for developing depression and anxiety at follow-up, suggesting that SRH also can predict development of depression and anxiety. Furthermore, continuous data suggest prediction of aggravated severity of depression and anxiety based on SRH. However, the proportion explained variance (1%) according to the hierarchical regression analyses was very small.

Vitality may be a contributing feature in explaining these associations and predictions since it partly underlies SRH (Au & Johnston, Citation2014) and is closely related to depression and anxiety (Lindeberg et al., Citation2006). Other conditions known to underlie SRH that may provide further explanations are daily hassles, stressful significant life events and low self-esteem (Graf et al., Citation2017; Jafflin et al., Citation2019).

The present results make it seem less plausible that associations between poor SRH and depression/anxiety are results of a psychological disposition affecting the assessment process (Ferraro et al., Citation1997). If poor SRH was to reflect a pessimistic attitude, that in part can be understood as a depressive symptom, it is difficult to explain the longitudinal association for individuals who do not show such symptoms at baseline. It is also likely that depression would have shown a stronger association than anxiety, since depression is more strongly related to pessimism. Thus, psychological aspects being part of or correlating with health in general may be more plausible (Ferraro et al., Citation1997).

The findings from both categorical and continuous data suggest that poor SRH, assessed with the time-efficient, 1-item SRH, indicates increased risk for comorbid depression and anxiety as well as development of depression and anxiety. Consequently, when a patient reports poor SRH, irrespective of presenting predominantly with mental or somatic complaints, healthcare professionals may consider screening for depression and anxiety. If time available is limited, ultra-brief screening instruments for depression and anxiety can be used, such as the 4-item Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al., Citation2009). In cases of suspected mental ill-health, an alternative to general SRH may be assessment of self-reported mental health (Casu & Gremigni, Citation2019). This version has been shown to be associated with poor general SRH, physical health problems, increased health service utilization and dissatisfaction with mental health services (Ahmad et al., Citation2014).

Regarding SRH being associated with comorbid depression and anxiety, additional chi-square analyses show that poor SRH at baseline was not significantly more common in cases of comorbid depression and anxiety than in cases of only depression or only anxiety, neither at baseline (53.7 vs. 49.3%) nor at follow-up (49.6 vs. 43.3%). According to the network approach, a mental disorder is a network of symptoms that stand in direct, possibly causal, relation to one another. Comorbidity between mental disorders is conceptualized as a direct relation between symptoms of multiple disorders (Cramer et al., Citation2010).

It has been suggest that depression and anxiety share the symptoms sleep disturbance, concentration problems, restlessness and fatigue (Carlehed et al., Citation2017; Cramer et al., Citation2010), which may predominantly be underlying poor SRH in these conditions. Other results suggest that anhedonia is a linking factor between anxiety and depression, such that anxiety devolves into depression through anhedonia (Winer et al., Citation2017). Notably, five of the 14 items of the presently used HADS can be referred to anhedonia. Hence, anhedonia may also be an important symptom contributing to poor SRH.

The strengths of this study include being population-based, using longitudinal data, stratifying the sample for age and sex, having a large sample size and that the study population had an age and sex distribution that is very similar to that of Sweden in general (Statistics Sweden, Citation2010). Another strength is that both categorical and continuous data support the conclusions, although the continuous data only very weakly so. Furthermore, the higher prevalence of physician-based diagnoses of depression and anxiety (and related disorders) in the poor SRH group, compared to the good SRH group, provides indirect support for the current use of the HADS and its cutoff score for depression and anxiety. As would be predicted (Wittchen et al., Citation2011), meeting the cutoff for anxiety was more prevalent than meeting the cutoff for depression.

A limitation is the relatively low response rate, 40.0% at baseline, although 73.4% at follow-up. This leaves only 29.4% of the initial sample for the analysis, which may have resulted in a selection bias, with implications for the representativeness. Another limitation is that data were collected at only two occasions during the three-year period.

In conclusion, despite its limitations, the results from the present study suggest that poor SRH (1) is associated with relatively severe degree of depression and anxiety symptoms, both concurrently and three years later, (2) predicts a persistent course of depression and anxiety symptoms and (3) predicts development of depression and anxiety symptoms three years later. Together with prior findings, an implication of the results is that SRH may be used in general practice to identify individuals at risk for comorbid poor mental health and at risk of it developing, in particular regarding depression and anxiety.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Eva Palmquist for valuable help with the database. This work is an extension of an undergraduate thesis by David Östberg.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmad, F., Jhajj, A. K., Stewart, D. E., Burghardt, M., & Bierman, A. S. (2014). Single item measures of self-rated mental health: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-398

- Ambresin, G., Chondros, P., Dowrick, C., Herrman, H., & Gunn, J. M. (2014). Self-rated health and long-term prognosis of depression. Annals of Family Medicine, 12(1), 57–65.

- Au, N., & Johnston, D. W. (2014). Self-assessed health: What does it mean and what does it hide? Social Science & Medicine (1982), 121, 21–28.

- Aydin, K. (2020). Self-rated health and chronic morbidity in the EU-28 and Turkey. Journal of Public Health, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01328-6

- Baćak, V. (2018). Measuring inequalities in health from survey data using self-assessed social class. Journal of Public Health, 40(1), 183–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdx036

- Balázs, J., Miklósi, M., Keresztény, A., Hoven, C., Carli, V., Wasserman, C., Hadlaczky, G., Apter, A., Bobes, J., Brunner, R., Corcoran, P., Cosman, D., Haring, C., Kahn, J.-P., Postuvan, V., Kaess, M., Varnik, A., Sarchiapone, M., & Wasserman, D. (2018). Comorbidity of physical and anxiety symptoms in adolescent: Functional impairment, self-rated health and subjective well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(8), 1698. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15081698

- Becchetti, L., Bachelet, M., Riccardini, F. (2018). Not feeling well … true or exaggerated? Self-assessed health as a leading health indicator . Health Economics, 27(2), e153–e170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3581

- Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T., & Neckelmann, D. (2002). The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(2), 69–77.

- Carlehed, G., Katz, J., & Nordin, S. (2017). Somatic symptoms of anxiety and depression: A population-based study. Mental Health & Prevention, 6, 57–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2017.03.005

- Casu, G., & Gremigni, P. (2019). Is a single-item measure of self-rated mental health useful from a clinimetric perspective? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 88(3), 177–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000497373

- Chiavarino, C., Poggio, C., Rusconi, F., Beretta, A. A. R., & Aglieri, S. (2019). Psychological factors and self-rated health: An observative study on cardiological patients. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(14), 1993–2002. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317712591

- Chou, K., Mackenzie, C. S., Liang, K., & Sareen, J. (2011). Three-year incidence and predictors of first-onset of DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in older adults: Results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(2), 144–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05618gry

- Cramer, A. O., Waldorp, L. J., Van Der Maas, H. L., & Borsboom, D. (2010). Comorbidity: A network perspective. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 137–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X09991567

- Cui, Y., Sweeney, E., Forbes, C., DeClercq, V., Grandy, S. A., Keats, M., … Dummer, T. J. (2020). The association between physical activity and self-rated health in Atlantic Canadians. Journal of Women & Aging, 33, 1–15.

- Cullati, S., Bochatay, N., Rossier, C., Guessous, I., Burton-Jeangros, C., & Courvoisier, D. S. (2020). Does the single-item self-rated health measure the same thing across different wordings? Construct validity study. Quality of Life Research, 29(9), 2593–2604. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02533-2

- De Beurs, E., Beekman, A., Geerlings, S., Deeg, D., Van Dyck, R., & Van Tilburg, W. (2001). On becoming depressed or anxious in late life: Similar vulnerability factors but different effects of stressful life events. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 179(5), 426–431. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.179.5.426

- Eriksson, I., Undén, A.-L., & Elofsson, S. (2001). Self-rated health: Comparisons between three different measures. Results from a population study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30(2), 326–633. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/30.2.326

- Ferraro, K. F., Farmer, M. M., & Wybraniec, J. A. (1997). Health trajectories: Long-term dynamics among black and white adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 38–54.

- Ganna, A., & Ingelsson, E. (2015). 5 year mortality predictors in 498 103 UK Biobank participants: A prospective population-based study. The Lancet, 386(9993), 533–540. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60175-1

- Graf, A. S., & Hicks Patrick, J. H. (2016). Self-Assessed health into late adulthood: Insights from a lifespan perspective. GeroPsych, 29(4), 177–187. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000156

- Graf, A. S., Long, D. M., & Patrick, J. H. (2017). Successful aging across adulthood: Hassles, uplifts, and self-assessed health in daily context. Journal of Adult Development, 24(3), 216–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-017-9260-2

- Han, K. M., Ko, Y. H., Yoon, H. K., Han, C., Ham, B. J., & Kim, Y. K. (2018). Relationship of depression, chronic disease, self-rated health, and gender with health care utilization among community-living elderly. Journal of Affective Disorders, 241, 402–410.

- Hu, Y., van Lenthe, F. J., Borsboom, G. J., Looman, C. W. N., Bopp, M., Burström, B., Dzúrová, D., Ekholm, O., Klumbiene, J., Lahelma, E., Leinsalu, M., Regidor, E., Santana, P., de Gelder, R., & Mackenbach, J. P. (2016). Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in self-assessed health in 17 European countries between 1990 and 2010. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(7), 644–652. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206780

- Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 21–37.

- Jacobson, N. C., & Newman, M. G. (2017). Anxiety and depression as bidirectional risk factors for one another: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 143(11), 1155–1200.

- Jafflin, K., Pfeiffer, C., & Bergman, M. M. (2019). Effects of self-esteem and stress on self-assessed health: A Swiss study from adolescence to early adulthood. Quality of Life Research : An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 28(4), 915–924.

- Jeon, J., Lee, W., Choi, W. J., Ham, S., & Kang, S. K. (2020). Association between working hours and self-rated health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2736. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082736

- Jurewicz, J., & Kaleta, D. (2020). Correlates of poor self-assessed health status among socially disadvantaged populations in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041372

- Jylhä, M. (2009). What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 69(3), 307–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013

- Kaneva, M., Gerry, C. J., & Baidin, V. (2018). The effect of chronic conditions and multi-morbidity on self-assessed health in Russia. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(8), 886–896.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Löwe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics, 50(6), 613–621.

- Levin-Zamir, D., Baron-Epel, O. B., Cohen, V., & Elhayany, A. (2016). The association of health literacy with health behavior, socioeconomic indicators, and self-assessed health from a national adult survey in Israel. Journal of Health Communication, 21(sup2), 61–68.

- Levola, J., Eskelinen, S., & Pitkänen, T. (2020). Associations between self-rated health, quality of life and symptoms of depression among Finnish inpatients with alcohol and substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Use, 25(2), 128–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2019.1664667

- Lindeberg, S. I., Östergren, P. O., & Lindbladh, E. (2006). Exhaustion is differentiable from depression and anxiety: Evidence provided by the SF-36 vitality scale. Stress, 9(2), 117–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890600823485

- Lisspers, J., Nygren, A., & Söderman, E. (1997). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD): Some psychometric data for a Swedish sample. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 96(4), 281–286.

- Mazeikaite, G., O’Donoghue, C., & Sologon, D. M. (2019). The Great Recession, financial strain and self-assessed health in Ireland. The European Journal of Health Economics : Hepac: Health Economics in Prevention and Care, 20(4), 579–596. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-1019-6

- Morriss, R. K., & Wearden, A. J. (1998). Screening instruments for psychiatric morbidity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 91(7), 365–368.

- Palmquist, E., Claeson, A.-S., Neely, G., Stenberg, B., & Nordin, S. (2014). Overlap in prevalence between various types of environmental intolerance. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 217(4-5), 427–434.

- Präg, P. (2020). Subjective socio-economic status predicts self-rated health irrespective of objective family socio-economic background. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 48(7), 707–714. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494820926053

- Statistics Sweden. (2010). Tables on the population of Sweden 2009: 1.3.1 Population by sex, age, marital status by county Dec. 31, 2009 according to the administrative subdivisions of Jan 1, 2010.

- Storey, A., Hanna, L., Missen, K., Hakman, N., Osborne, R. H., & Beauchamp, A. (2020). The association between health literacy and self-rated health amongst Australian university students. Journal of Health Communication, 25(4), 333–311. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2020.1761913

- Thielke, S. M., Diehr, P., & Unutzer, J. (2010). Prevalence, incidence, and persistence of major depressive symptoms in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Aging & Mental Health, 14(2), 168–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903046537

- Vasiliadis, H. M., Dionne, P. A., Préville, M., Gentil, L., Berbiche, D., & Latimer, E. (2013). The excess healthcare costs associated with depression and anxiety in elderly living in the community. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(6), 536–548. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2012.12.016

- Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., Charlson, F. J., Norman, R. E., Flaxman, A. D., Johns, N., Burstein, R., Murray, C. J. L., & Vos, T. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England), 382(9904), 1575–1586. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6

- WHO. (2020). Mental health in the workplace: Information sheet. www.who.int/mental_health/in_the_workplace/en/

- Willerth, M., Ahmed, T., Phillips, S. P., Pérez-Zepeda, M. U., Zunzunegui, M. V., & Auais, M. (2020). The relationship between gender roles and self-rated health: A perspective from an international study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 87, 103994. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.103994

- Winer, E. S., Bryant, J., Bartoszek, G., Rojas, E., Nadorff, M. R., & Kilgore, J. (2017). Mapping the relationship between anxiety, anhedonia, and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 221, 289–296.

- Wittchen, H. U., Jacobi, F., Rehm, J., Gustavsson, A., Svensson, M., Jönsson, B., Olesen, J., Allgulander, C., Alonso, J., Faravelli, C., Fratiglioni, L., Jennum, P., Lieb, R., Maercker, A., van Os, J., Preisig, M., Salvador-Carulla, L., Simon, R., & Steinhausen, H.-C. (2011). The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. European Neuropsychopharmacology : The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 21(9), 655–679. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x