Abstract

Background

Ongoing concern for the unique mental health challenges faced by university students has been magnified by the disruption of the global COVID-19 pandemic since March 2020.

Aims

This study aimed to investigate changes in mental health and wellbeing outcomes for UK university students since the pandemic began, and to examine whether more vulnerable groups were disproportionately impacted.

Methods

Students at a UK university responded to anonymous online cross-sectional surveys in 2019 (N = 2637), 2020 (N = 3693), and 2021 (N = 2772). Students completed measures of depression, anxiety and subjective wellbeing (SWB). Multivariable logistic regression models investigated associations of survey year and sociodemographic characteristics with mental health and SWB.

Results

Compared to 2019, fewer students showed high levels of depression and anxiety symptoms in 2020. However, there was evidence of worsened levels of anxiety and SWB in 2021 compared to 2019. Interaction effects indicated that students from a Black, Asian or minority ethnicity background and students previously diagnosed with a mental health difficulty showed improved outcomes in 2021 compared to previous years.

Conclusions

There is a need for sector-wide strategies including preventative approaches, appropriate treatment options for students already experiencing difficulties and ongoing monitoring post-pandemic.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic had both immediate and ongoing consequences for people’s lives, not least university students. Even before the pandemic, there had been growing concerns for the mental health and wellbeing of university students (Auerbach et al., Citation2018). Prior to the pandemic universities around the world were already seeing year-on-year increases in the numbers of students seeking support for mental health problems (Lipson et al., Citation2019; Oswalt et al., Citation2020), specifically from counselling services (Broglia et al., Citation2018; Thorley, Citation2017). This reflects increases in depression, anxiety and self-harm in young people more widely, particularly teenage girls (Ford et al., Citation2021). Evidence gathered globally also indicates the COVID-19 pandemic had particularly impacted levels of depression and anxiety for younger populations (Santomauro et al., Citation2021). COVID-19 has affected all areas of daily life, and more widely impacted healthcare systems (Iyengar et al., Citation2020) and the global economy (Ozili & Arun, Citation2020), contributing to a climate of uncertainty about the present and future. There has been ongoing debate about whether or not university student mental health and wellbeing has deteriorated since the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to pre-pandemic levels (Grubic et al., Citation2020).

Concerns about worsening student mental health in the UK during the pandemic may have reflected the many ways student life had to change after government restrictions to prevent the spread of COVID-19 were first introduced in March 2020. Longitudinal studies in Italy, Switzerland, and the UK following student cohorts between 2019 and April 2020 reported poorer mental health and wellbeing outcomes after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Elmer et al., Citation2020; Evans et al., Citation2021; Meda et al., Citation2021). Universities were required to respond rapidly to support students remotely (Liu et al., Citation2020). Educationally, students were faced with campus closures, new remotely delivered courses, disruption to course assessments and adjusted access to academic support (Dhawan, Citation2020; Gamage et al., Citation2020). Socially, requirements to stay at home and limits placed on opportunities to socialise, both restricted physical activity (Savage et al., Citation2020) and disconnected students from their peers, family and the wider community (Freeman et al., Citation2021).

The mental health of some groups may have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic (Holmes et al., Citation2020). For example, international students studying in the UK will have been affected by travel restrictions, separation from their wider support networks and fears for the health and safety of their families as Covid-19 infection rates fluctuated globally (Zhai & Du, Citation2020). Black, Asian and Minority ethnicity students may also have been at a greater risk for poor mental health due to poorer COVID-19 clinical outcomes (Mamluk & Jones, Citation2020), and subsequently greater likelihood of experiencing family bereavement during the pandemic. Finally, students with a history of mental health difficulty may have found self-isolation, restricted access to services and disrupted usual routines an aggravator of underlying difficulties (Yao et al., Citation2020).

The overall aim of this study was to compare pre-pandemic data (2019) among university students attending a UK university, with data collected during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020), and again after living through the COVID-19 pandemic (2021). Additionally, to investigate associated social, educational and health factors and any differential impact on student mental health.

Research question 1: How do levels of anxiety, depression and subjective wellbeing differ among students between 2019, 2020 and 2021?

Research question 2: Have mental health and subjective wellbeing outcomes worsened for students with additional vulnerabilities (i.e. history of mental health diagnosis, Black, Asian, or ethnic minority, and International students) since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methods

Design and context

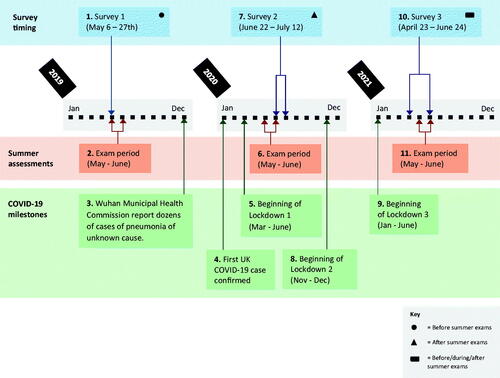

All registered students (undergraduate, postgraduate-taught and postgraduate research) within a large UK university were invited to participate in anonymised online cross-sectional questionnaires in 2019 (May), 2020 (June/July) and 2021 (April to June). The institution has tracked student mental health and wellbeing outcomes to support policymaking with an annual Student Wellbeing Survey since 2018, however for 2020, it was renamed The Covid-19 Survey. presents a timeline of survey timings in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic and examination dates. Students received email reminders about the survey during the data collection period and the survey was promoted on social media. Participants provided informed consent before taking part in the survey. The survey tool was designed with collaborative input from students, academics and staff leading wellbeing support services for students. In the UK, the first national lockdown began on 23 March 2020, and following easing of social restrictions in the summer of 2020, a second national lockdown began on October 31. Following further easing of restrictions and the re-introduction of a tier system, the UK entered a third national lockdown 6 January 2021. By 21 June 2021, all national legal limits on social contact were removed. During the lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, changes were made to educational procedures, e.g. teaching, assessments and learning support transferred online, and many student services, e.g. wellbeing assistance, counselling provision, transferred to telephone or online support.

No incentives for participation were provided to survey respondents. We obtained ethical approval through the University Faculty of Health Sciences Ethics Committee (reference: 49861).

Measures

Survey data were collected on key sociodemographics (gender, ethnicity, whether they were the first person in their family to attend university (a measure of socioeconomic position) and sexual orientation). Educational data concerning international student status, and whether they were studying for an undergraduate or postgraduate qualification (course type) were also collected. To assess previous mental health difficulties, students were asked to report whether “a doctor, psychiatrist or other medical professional has ever diagnosed you with a mental health condition?”.

Depressive symptoms in the previous two weeks were screened using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), where scores of 10 or higher are interpreted as indicative of moderate/severe depression (Kroenke et al., Citation2001). Levels of anxiety symptoms in the previous 2 weeks were screened using the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), where scores of 10 or higher are interpreted as indicative of moderate/severe anxiety (Spitzer et al., Citation2006). Levels of subjective wellbeing (SWB) in the previous two weeks were measured with the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS) (Fat et al., Citation2017), with scores ranging from 7 to 35. In this study, we used the cut-off of 19.5 or below to signal low SWB and scores above 19.5 to signal moderate/high SWB (Warwick Medical School, Citation2021). For the PHQ-9, GAD-7 and SWEMWBS, total scores were calculated for students who fully completed these measures.

Data analysis

Research question 1

We used descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages) to summarise the variables in our analysis across each year of data collection. We estimated three multivariable logistic regression models to assess whether survey year and student characteristics were associated with odds of moderate/severe depression (model 1), moderate/severe anxiety (model 2) and low SWB (model 3). Each model controlled for the potential confounding factors outlined in . These variables were included in our three multivariable models alongside survey year (2019, 2020 and 2021), to control for differing responder characteristics across survey years.

Table 1. Confounding variables controlled for within multivariable logistic regression models.

Odds ratios (ORs) were provided with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). All logistic regression analyses used a “complete case approach”, omitting respondents with missing data on any of the variables. Complete cases were available for 96.4% of respondents in model 1 (8772/9102), 96.5% of respondents in model 2 (8781/9102), and 96.4% of respondents in model 3 (8778/9102). Statistical analyses were undertaken using STATA 16 (College Station, TX).

Research question 2

We investigated interaction effects between previous mental health diagnosis, Black, Asian and minority ethnic background (ethnicity), and international student status (fee status) with our three-level survey year variable. We prioritised these student groups on the basis that they may be more likely to experience additional wellbeing challenges during the pandemic (as outlined in section “Introduction”). We used likelihood-ratio (LR) tests to compare these nested models, and stratified ORs are presented for each survey year within supplementary materials.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Two thousand six hundred and thirty-seven students completed the 2019 survey (response rate = 2637/26,102: 10%), 3693 students completed the 2020 survey (response rate = 3693/27,513: 13%), and 2772 students competed the 2021 survey (response rate = 2772/29,536: 9%). Respondent characteristics are presented in . The majority of respondents in all three years were female, ranging from 63.2% (2021) to 69.4% (2019), and approximately 80% were aged 24 or younger. We observed a higher percentage of Black, Asian or minority ethnicity respondents, international students, and postgraduates in 2020 compared to 2019 and 2021. There was a noticeably lower percentage of heterosexual students in 2021 compared to 2020 and 2019. A higher percentage of students reported that they had never been diagnosed with a mental health difficulty in their lifetime in the 2020 survey, compared to 2021 and 2019. Finally, there was a higher proportion of students who were the first-generation in their family to attend university in 2021, compared to 2020 and 2019. Although female students were overrepresented in our study sample (compared to administrative data on registered students at the same university), overall demographic proportions for gender (majority female), fee status (majority home/EU), ethnicity (majority White British) and level of study (majority undergraduate) for our sample largely match the proportions of the student population this sample was drawn from (Supplementary file 1).

Table 2. Respondent socio-demographic characteristics for 2019, 2020 and 2021.

Mental health and wellbeing outcomes across study years are presented in . A lower percentage of students reported moderate/severe symptoms of depression in 2020 (1396, 37.8%), compared to 2021 (1334, 48.1%) and 2019 (1219, 46.2%). Similarly, a lower percentage of students reported moderate/severe symptoms of anxiety in 2020 (1063, 28.8%), compared to 2021 (1183, 46.7%) and 2019 (947, 35.9%). Similar levels of students reported lower SWB in 2020 (1811, 49.0%) and 2019 (1290, 48.9%) compared to a greater percentage in 2021 (1212, 56.3%).

Table 3. Mental health and wellbeing outcomes in 2021, 2020 and 2019.

Logistic regression analyses

Research question 1 – How do levels of anxiety, depression and subjective wellbeing (SWB) differ between 2019, 2020 and 2021?

The odds for moderate/severe depression, moderate/severe anxiety and low SWB across survey years controlling for respondent characteristics are presented in . In 2020, students had a 26% lower odds of screening positive for depression symptoms compared to 2019 (OR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.66–0.82), and again in 2021 they had a 4% lower odds of screening positive for depression compared to 2019 (OR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.85–1.08). In 2020, students also had a 21% lower odds of screening positive for anxiety compared to 2019 (OR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.70–0.89), but a 25% higher odds of screening positive for anxiety in 2021 (1.25, 95% CI = 1.11–1.41). The odds of students reporting lower levels of SWB increased by 6% in 2020 (1.06, 95% CI = 0.95–1.18), but students had a 27% higher odds of reporting lower SWB in 2021 compared to 2019 (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.14–1.43).

Table 4. Factors associated with depression (model 1), anxiety (model 2) and low SWB (model 3)a.

Key risk factors for moderate/severe depression were identifying as a minority gender, ethnicity or sexuality, being a first-generation student, and having a previously diagnosed mental health difficulty, with the latter being the most strongly related (OR = 3.02, 95% CI = 2.73–3.34). Protective factors against moderate/severe depression were male gender and being a postgraduate research student. Key risk factors for moderate/severe anxiety were identifying as a minority ethnicity or sexuality, being a first-generation student, and having a previously diagnosed mental health difficulty, with the latter being the most strongly related (OR = 3.06, 95% CI = 2.77–3.38). Again, the only protective factors identified against moderate/severe anxiety were male gender and being a postgraduate research student. Key risk factors for low SWB were identifying as a minority ethnicity, gender or sexuality, being a first-generation student, and having a previously diagnosed mental health difficulty, with the latter being the most strongly related (OR = 2.50, 95% CI = 2.27–2.77).

Research question 2 – Have mental health and subjective wellbeing outcomes worsened for students with additional vulnerabilities (i.e. history of mental health diagnosis, Black, Asian, or ethnic minority, and international students) since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Stratified ORs and p values for interaction in models 1, 2 and 3 are presented separately within Supplementary File 2. There was statistical evidence (p = 0.039) that the risk of depressive symptoms among respondents with a previous mental health diagnosis compared to those without a previous diagnosis declined across the three survey years with the strongest association in 2019 (OR = 3.66, 95% CI = 3.00–4.33) and weaker associations in 2020 (OR = 2.89 (2.42–2.36) and 2021 (OR = 2.68, 95% CI = 2.22–3.14). There was also evidence (p = 0.008) that the risk of poor SWB decreased for this group between 2019 (OR = 3.16, CI = 2.60–3.73) and 2020 (OR = 2.21, CI = 1.85–2.57), and between 2019 and 2021 (OR = 2.32, CI = 1.92–2.72). Similarly, there was statistical evidence (p = 0.005) that the risk of depressive symptoms among Black, Asian or ethnic minority respondents compared to other students declined between 2019 and 2021, with the strongest association in 2019 (OR = 1.88, 95% CI = 1.40–2.37), a reduction in 2020 (OR = 1.56 (95% CI = 1.25–1.88) and again in 2021 (OR = 1.08, 95% CI = 0.83–1.33).

Discussion

Main findings

Levels of anxiety and depression were lower in 2020 in the early stages of the pandemic compared to 2019. However, levels of anxiety were higher in 2021 compared to 2019 following multiple national lockdowns, changing social restrictions and extended changes to university life. Low levels of SWB were more prominent in 2021 than 2019. In contrast, levels of depression were not worse in 2021 compared to 2019. Consistent key risk factors for poor mental health and wellbeing were: being from a Black, Asian and minority ethnicity group, non-binary or another gender, identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or another sexuality, being the first person in your family to study at university, and most notably having a history of diagnosed mental health difficulty. Rather than being more susceptible to difficulty, students with a history of mental health diagnosis had a lower risk of depression relative to students without a history of mental health diagnosis in 2020 and 2021 compared to 2019. Similarly, students from a Black, Asian or minority ethnicity background had lower risk of depression relative to students from a White British background in 2020 and 2021 compared to 2019. While mental health diagnosis and ethnicity are still strongly associated with mental health and wellbeing outcomes, the data show a monotonic reduction in the influence of both between 2019 and 2021.

Existing literature

In contrast to several existing studies (Elmer et al., Citation2020; Evans et al., Citation2021; Meda et al., Citation2021), our research highlights increased anxiety and lower SWB later into the pandemic in 2021, rather than in 2020 as reported elsewhere. Key risk factors for poor mental health and wellbeing among university students identified within the existing literature have been further highlighted in this study, specifically being a first generation student (Stebleton et al., Citation2014), identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or another sexuality (Auerbach et al., Citation2018), and being from a Black, Asian or ethnic minority background (Arday, Citation2018). Contrary to our hypothesis, we report results in line with emerging evidence demonstrating improved mental health and wellbeing outcomes during the pandemic for students with a history of diagnosed mental health difficulty (Hamza et al., 2021). These groups assumed to be disproportionately impacted during the pandemic may in fact have benefited most from campus closures and subsequent freedom from growing social pressures of university life, embracing the “joy of missing out” (JOMO) (Crook, Citation2014). Lockdowns may have also provided the time and space required to reflect and act on individual needs. While mental health diagnosis and ethnicity are still strongly associated with mental health and wellbeing outcomes, we observed a reduction in the influence of both over time.

Strengths and limitations

The key strength of this research is the availability of pre-pandemic data. Within our multi-year study design, we were are able to report on how poor mental health and SWB in 2021 represent a meaningful decline when compared to the same outcomes prior to and during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. This extends the insights of smaller longitudinal and single-year cross-sectional studies. Further, this study was co-developed through collaborative input from academic staff, students and support service providers. Multi-stakeholder perspectives were incorporated into the initial development, data collection, analysis and writing up of the research, to reflect the importance of multiple forms of topic-expertise.

A key limitation of our study is the response rate and that responder characteristics differed across survey years. The 2020 survey had a lower percentage of respondents with previously diagnosed mental health difficulties (18%), compared to the 2019 survey (34%) and 2021 survey (30%). Its promotion as a “Covid-19” survey in 2020 rather than a “Wellbeing” survey, may have engaged students with a different mental health profile. Second, as this study was conducted in a single university setting, further research would be needed to deterimine whether these findings represent trends across the sector. This further research would rely on cross-institutional collaborative partnerships where common outcome measures could be agreed and data shared across universities (Barkham et al., Citation2019; Broglia et al., Citation2021). A final limitation is that we collected our data at slightly different times of the year across years, each period with potentially differing implications for student stress levels, such as heightened anxiety during exam periods when many students juggle revision and final assessments.

Implications and future research

In response to worsened outcomes in 2021 compared to pre-pandemic data, there is a continued need to ensure available treatment options are appropriately resourced, accessible, able to meet the needs of students and minimise the impact of ill-health on studies. Simultaneously, preventative strategies must be prioritised to equip students with tools to navigate ongoing educational and wider social uncertainties (Conley et al., Citation2017). Increasing evidence suggests mental health difficulties are rising among young people more broadly (Ford et al., Citation2021; Hafstad & Augusti, Citation2021; Kwong et al., Citation2021). Universities should therefore work collaboratively with experts in healthcare, different stages of education, and specialist charities within a wider and more connected network of support for young people (Universities UK, Citation2018). Future research is required to explore how the wellbeing needs of university students may have shifted or been unmet during the pandemic, to ensure support provisions can be appropriately designed and targeted. With calls in the HE sector for universities to demonstrate their commitment to student mental health and wellbeing, this research underlines the importance of an evidence-based population approach to understanding, monitoring and supporting the student experience (Hughes & Spanner, Citation2019).

Groups predicted to struggle more during the pandemic demonstrated the opposite outcome. However, some students will have spent parts of lockdown at home with family support. In addition, the academic mitigations made to ensure the grading of assessments and exams were not adversely affected by Covid may have reduced student stress. In addition, the absence of other campus stressors may have been a protective factor. Therefore, further research should explore the conditions associated with these findings amidst such societal upheaval. This research could generate recommendations for transferable policy and practice useful for supporting students experiencing additional vulnerabilities in university or other educational settings. Although students with a mental health diagnosis reported better outcomes in 2021, in general, they still experience some of the poorest ongoing mental health and wellbeing compared to students who have not had a diagnosis. Further work is needed to support young people transitioning out of children and adolescent mental health services (Dunn, Citation2017) as they transition into university life (Worsley et al., Citation2021).

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study utilised pre-pandemic data, early pandemic data, and data collected one year into the pandemic to demonstrate improvements in mental health outcomes in 2020, followed by worsened levels of anxiety and lower levels of SWB in 2021, compared to pre-pandemic data collected in 2019. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, groups we identified as potentially more vulnerable did not appear to be disproportionately impacted. Alongside preventative strategies to offset the development of mental health difficulties, addressing the rising prevalence of clinically significant symptoms requires appropriate support from specialists across sectors that meets the needs of students studying in the aftermath of a pandemic. Further research into how later stages of the pandemic may have been more challenging for students than earlier stages of the pandemic would help to contextualise the findings of this study.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (42.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the survey's Governance Group for supporting the development of this research, through collaboration between university staff and students. We also thank the thousands of students who have taken part in this research since it began in 2017.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arday, J. (2018). Understanding mental health: What are the issues for black and ethnic minority students at university? Social Sciences, 7(10), 196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100196

- Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Murray, E., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Stein, D. J., Vilagut, G., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2018). WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623–638. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362

- Barkham, M., Broglia, E., Dufour, G., Fudge, M., Knowles, L., Percy, A., Turner, A., & Williams, C. (2019). Towards an evidence-base for student wellbeing and mental health: Definitions, developmental transitions and data sets. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19(4), 351–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12227

- Broglia, E., Bewick, B., & Barkham, M. (2021). Using rich data to inform student mental health practice and policy. Wiley Online Library.

- Broglia, E., Millings, A., & Barkham, M. (2018). Challenges to addressing student mental health in embedded counselling services: A survey of UK higher and further education institutions. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46(4), 441–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1370695

- Conley, C. S., Shapiro, J. B., Kirsch, A. C., & Durlak, J. A. (2017). A meta-analysis of indicated mental health prevention programs for at-risk higher education students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(2), 121–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000190

- Crook, C. (2014). The joy of missing out: Finding balance in a wired world. New Society Publishers.

- Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520934018

- Dunn, V. (2017). Young people, mental health practitioners and researchers co-produce a Transition Preparation Programme to improve outcomes and experience for young people leaving Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2221-4

- Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS One, 15(7), e0236337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

- Evans, S., Alkan, E., Bhangoo, J. K., Tenenbaum, H., & Ng-Knight, T. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health, wellbeing, sleep, and alcohol use in a UK student sample. Psychiatry Research, 298, 113819. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113819

- Fat, L. N., Scholes, S., Boniface, S., Mindell, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2017). Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the Health Survey for England. Quality of Life Research, 26(5), 1129–1144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1454-8

- Ford, T., John, A., & Gunnell, D. (2021). Mental health of children and young people during pandemic. British Medical Journal Publishing Group.

- Freeman, S. W., Chung, R. J., Ford, C. A., & Wong, C. A. (2021). Winning the hearts and minds of young adults in the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(3), 441–442. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.12.131

- Gamage, K. A., Wijesuriya, D. I., Ekanayake, S. Y., Rennie, A. E., Lambert, C. G., & Gunawardhana, N. (2020). Online delivery of teaching and laboratory practices: Continuity of university programmes during COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 10(10), 291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10100291

- Grubic, N., Badovinac, S., & Johri, A. M. (2020). Student mental health in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for further research and immediate solutions. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(5), 517–518. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020925108

- Hafstad, G. S., & Augusti, E.-M. (2021). A lost generation? COVID-19 and adolescent mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 8(8), 640–641. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00179-6

- Hamza, C. A., Ewing, L., Heath, N. L., & Goldstein, A. L. (2021). When social isolation is nothing new: A longitudinal study psychological distress during COVID-19 among university students with and without preexisting mental health concerns. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 62(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000255

- Holmes, E. A., O'Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Cohen Silver, R., Everall, I., Ford, T., John, A., Kabir, T., King, K., Madan, I., Michie, S., Przybylski, A. K., Shafran, R., Sweeney, A., … Worthman, C. M. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

- Hughes, G., & Spanner, L. (2019). The university mental health charter. Student Minds.

- Iyengar, K., Mabrouk, A., Jain, V. K., Venkatesan, A., & Vaishya, R. (2020). Learning opportunities from COVID-19 and future effects on health care system. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome, 14(5), 943–946. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.036

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

- Kwong, A. S. F., Pearson, R. M., Adams, M. J., Northstone, K., Tilling, K., Smith, D., Fawns-Ritchie, C., Bould, H., Warne, N., Zammit, S., Gunnell, D. J., Moran, P. A., Micali, N., Reichenberg, A., Hickman, M., Rai, D., Haworth, S., Campbell, A., Altschul, D., … Flaig, R. (2021). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 218(6), 334–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.242

- Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by US college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 60–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800332

- Liu, C. H., Pinder-Amaker, S., Hahm, H. C., & Chen, J. A. (2020). Priorities for addressing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health. Journal of American College Health, 1–3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1803882

- Mamluk, L., & Jones, T. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. National Institute for Health Research (NHR) Report, 20(05).

- Meda, N., Pardini, S., Slongo, I., Bodini, L., Zordan, M. A., Rigobello, P., Visioli, F., & Novara, C. (2021). Students’ mental health problems before, during, and after COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 134, 69–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.045

- Oswalt, S. B., Lederer, A. M., Chestnut-Steich, K., Day, C., Halbritter, A., & Ortiz, D. (2020). Trends in college students’ mental health diagnoses and utilization of services, 2009–2015. Journal of American College Health, 68(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1515748

- Ozili, P. K., & Arun, T. (2020). Spillover of COVID-19: Impact on the global economy. SSRN 3562570.

- Santomauro, D. F., Mantilla Herrera, A. M., Shadid, J., Zheng, P., Ashbaugh, C., Pigott, D. M., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., Amlag, J. O., Aravkin, A. Y., Bang-Jensen, B. L., Bertolacci, G. J., Bloom, S. S., Castellano, R., Castro, E., Chakrabarti, S., Chattopadhyay, J., Cogen, R. M., Collins, J. K., … Dai, X. (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 398(10312), 1700–1712. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

- Savage, M. J., James, R., Magistro, D., Donaldson, J., Healy, L. C., Nevill, M., & Hennis, P. J. (2020). Mental health and movement behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic in UK university students: Prospective cohort study. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 19, 100357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2020.100357

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Stebleton, M. J., Soria, K. M., & Huesman, R. L., Jr. (2014). First-generation students' sense of belonging, mental health, and use of counseling services at public research universities. Journal of College Counseling, 17(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2014.00044.x

- Thorley, C. (2017). Not by degrees: Not by degrees: Improving student mental health in the UK’s universities. IPPR.

- Universities UK. (2018). Minding our future: Starting a conversation about the support of student mental health. https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/sites/default/files/field/downloads/2021-07/minding-our-future-starting-conversation-student-mental-health.pdf

- Warwick Medical School. (2021). Collect, score, analyse and interpret WEMWBS. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/platform/wemwbs/using/howto/

- Worsley, J. D., Harrison, P., & Corcoran, R. (2021). Bridging the gap: Exploring the unique transition from home, school or college into university. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.634285

- Yao, H., Chen, J.-H., & Xu, Y.-F. (2020). Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), e21.

- Zhai, Y., & Du, X. (2020). Mental health care for international Chinese students affected by the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(4), e22.