Abstract

Background

Recovery Colleges are an innovative approach to promoting personal recovery for people experiencing mental illness.

Aims

This study was to explore experiences of students, supporters, staff, educators and external stakeholders (i.e. partner organisations) of a pilot Recovery College in the Australian Capital Territory (ACTRC), and the impact of participation in the College for students and supporters.

Methods

ACTRC students, supporters, staff and educators, and external stakeholders were invited to participate in a mixed-method evaluation via an online survey, interviews and/or focus groups. The survey included questions regarding experiences and recovery-orientation of the College environment, and for students and supporters only, satisfaction with the College. Qualitative data from interviews and focus groups was inductively coded, thematically analysed and triangulated with survey responses.

Results

The findings suggest that the ACTRC provides a safe space, promotes meaningful connections within and beyond the college, and offers steppingstones supporting recovery and growth. Participants spoke positively about cross institutional partnerships and collaboration with several organisations within the ACT.

Conclusions

This evaluation reiterates the role of Recovery Colleges as an innovative approach to promoting personal recovery for people living with mental illness. Adequate resourcing and collaboration are essential in realising the value of co-production whilst ensuring sustainability.

Introduction

Personal recovery for individuals experiencing mental health challenges entails a journey to (re-) establish a meaningful life in their community (Slade & Wallace, Citation2017). A systematic review of recovery literature identified the key dimensions of personal recovery: connectedness and inclusion; hope and purpose; identity; meaning; and choice and empowerment (Leamy et al., Citation2011). Lived experience perspectives on recovery have introduced a shift in mental health policy and practice in Australia and internationally (Pincus et al., Citation2016). A recovery perspective adopts a person-centred and strengths-based approach to promote hope, meaning, growth and collaboration, in safe and inclusive environments (Le Boutillier et al., Citation2011; Winsper et al., Citation2020). Despite this shift, a sense of purposelessness, loneliness and disconnection continue to be reported by those experiencing mental illness (Fortuna et al., Citation2020). Thus, providing opportunities for engagement and connection should be prioritised in service design and resourcing (Doroud et al., Citation2022).

Recovery Colleges have been developed to promote recovery, wellbeing, growth, connectedness and inclusion (Crowther et al., Citation2019; Ebrahim et al., Citation2018; Muir‐Cochrane et al., Citation2019; Windsor et al., Citation2017). Recovery Colleges offer an educational approach to recovery, delivering courses co-designed and co-facilitated by people with lived experience of mental illness (hereafter, referred to as “lived experience”). Recovery colleges are open to anyone who wish to learn about mental health; participants are “students,” not “patients” or “clients”, reflecting a shift in focus from treatment to education and inclusion (Perkins et al., Citation2012).

Toney et al. (Citation2018) identified four mechanisms of action in Recovery Colleges: (1) an empowering environment; (2) enabling relationships; (3) facilitating personal growth; and (4) shifting the balance of power. These elements improve mental health outcomes, including mental wellbeing and social inclusion; satisfaction with life and attainment of recovery goals; employment; empowerment; and reduced service use (Bourne et al., Citation2018). Recovery Colleges also encourage power sharing between healthcare practitioners and service-users through co-production (Thériault et al., Citation2020). Co-production involves planning, designing and delivering college courses in collaboration with service-users with lived-experience (Roper et al., Citation2018).

This external evaluation, led by La Trobe University and commissioned by the Australian Capital Territory government, explored the experiences of students and other stakeholders involved with a pilot Recovery College in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) from January 2019 to June 2021. The evaluation question was: What are the experiences of students, support persons, staff, educators and external stakeholders (e.g., partner organisations) of the ACT Recovery College (ACTRC) and its impact in their lives?

Methods

Study design

A convergent mixed-methods evaluation design was used to identify the experiences of students, support persons, staff, educators and external stakeholders (i.e. partner organisations) and the impact of participation in the college for students and supporters. Quantitative data were collected via routine enrolment and feedback procedures, and an online survey. Qualitative methods included open-text items in the survey, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. Qualitative and quantitative data were synthesised during analysis (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). A steering committee, comprised of members of the research team, ACTRC staff, student representatives and external stakeholders, contributed to the study design, recruitment, data collection, and analysis. This is important to demonstrate our commitment to Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) (Morgan, Citation2016) and our aspiration to conduct this evaluation in partnership with service-users with lived-experience ensure they had a voice in the project and engaged in evaluation of the college. Members were nominated by the ACTRC, and the committee was chaired by the principal investigator [initials removed] and co-chaired by a committee member with lived experience. Members of the steering committee were eligible to participate in the research.

Researchers

The main research team were employed by La Trobe University, with experience in mental health service provision and evaluation, and qualifications in research, social work and occupational therapy. Two members of the team were consumer researchers. All team members identify as female.

Setting

The ACT Government funded a two-year pilot of the ACTRC, commencing in January 2019, which was extended by six months in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The ACTRC was auspiced by a non-government mental health organisation, with the support of local stakeholders including state-funded health services and vocational education providers. The ACTRC was open to public and offered free courses to adults living in the ACT and surrounds, who were interested in learning about mental health, recovery and wellbeing. In a Recovery College setting, the term “student” is used for anyone who attends the college. The students are typically people with lived experience of mental illness, who can self-enrol any time (i.e., referral or using other mental health services is not necessary). Recovery Colleges are open to anyone, and healthcare professionals may also attend as student.

The ACTRC shared many of the core features of Recovery Colleges worldwide: as a place of education; as a “soft entry point” for people living with mental illness; and adherence to principles of adult learning, co-production and recovery (Brophy et al., Citation2022).

Participant recruitment

Participants were purposively recruited from five stakeholder groups: students (i.e., people with lived experience of mental illness); support persons (i.e., carers, family, friends); staff (i.e., managerial and administrative staff both in paid or volunteer roles); educators (i.e., those involved in development and delivery of courses); and external stakeholders (i.e., staff of partnering organisations).

Apart from members of the steering committee, participants had no contact with researchers prior to their participation.

Potential participants (including all students, support persons, staff, educators and external stakeholders) received an invitation to participate via e-mail, printed flyers distributed by ACTRC staff during face-to-face courses (prior to COVID-19 public health restrictions), and the ACTRC’s Facebook group. Participants with current or past involvement with the ACTRC were eligible to participate in the study.

Data collection

Data collection included two phases: (i) survey and/or individual interviews; (ii) focus groups. Participants were offered the option of participating in the online survey, an individual interview and/or a follow-up focus group. The survey was supported by the Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) platform and pilot tested by the research team for accessibility via personal computer or handheld device (e.g., phone, tablet). Interviews (except one, completed by telephone) and focus groups were conducted via the Zoom videoconferencing application, which had been used by the ACTRC for online courses since the implementation of COVID-19 public health restrictions.

Survey

An online survey was available for participants to complete at any time during an 11-week period. It included closed and open-ended questions regarding participants’ experiences of ACTRC. For students and supporters, the survey also included scales measuring their satisfaction and the impact of their participation in the ACTRC.

The survey was developed based on a previous Recovery College evaluation (Hall et al., Citation2018). Open questions were reviewed and modified with feedback from the project steering committee, within the parameters stipulated by funders. The survey also included 14 closed questions from the developing recovery enhancing environment Measure (DREEM) (Dinniss et al., Citation2007), a validated self-report instrument widely used to evaluate the coherence of a health service with recovery-oriented principles (Ridgway & Press, Citation2004). Responses were on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” For students and supporters, the modified Mind Australia satisfaction survey (MASS) was included. The MASS is a self-report questionnaire used by Mind Australia services to assess client satisfaction (Hall et al., Citation2018). It includes 10 closed questions with responses ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” with the option of “no comment.”

Interviews

Individual in-depth interviews were conducted using a semi-structured approach based on the open-ended questions used in the survey to further explore participants’ perspectives and identify experiences not captured in the survey. Questions pertained to the experiences and impact of the ACTRC for participants. The research team met regularly to review the interview questions and procedures so to identify emerging themes and to decide whether the questions need to be refined. Interviews took 40 – 60 minutes. Interview participants also completed the DREEM described previously.

Focus groups

Four separate focus groups were conducted with students, staff, educators, and external stakeholders to discuss preliminary findings and further explore participant perspectives. One support person was available for focus group who was offered an individual interview. Separate focus groups encouraged participation and exploring various perspectives (e.g. conflicting perspectives).

Prior to each focus group, participants received a summary analysis of the survey and interview data; and recommendations to stimulate discussion. Groups were facilitated by four of the authors (CB, LB, ND, TZ) and took approximately 90 minutes. Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded, professionally transcribed and returned to the research team using an encrypted cloud-based platform (CloudStor).

Data analysis

Survey responses to the DREEM were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics. Open-text responses were imported to NVivo 12 QSR software (QSR International Pty Ltd., Citation2020) that helped with organizing and coding the data.

The first author inductively coded data from the interviews and focus groups using thematic analysis methods (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) in combination with constant comparative methods (Birks & Mills, Citation2015; Bryant & Charmaz, Citation2007). This began with line-by-line coding of the interview transcripts and generating tentative themes, followed by coding the focus group data and comparing them with the tentative themes. After this, three authors (CB, LB, ND) independently coded three transcripts and met to refine codes and themes. Finally, the first author compared the themes with the data and grouped them under categories. This allowed to generate of an understanding grounded in participants’ experiences.

Survey, interview and focus group data were compared for similarities and discrepancies through several discussions amongst the authors and synthesized into one coding framework, summarized in a report on completion of the project (Brophy et al., Citation2022).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by ACT Health and La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference 2020.ETH.00100/REGIS 2020/ETH01043). All participants provided informed consent.

Results

Participant characteristics

shows the number of participants (n = 82) by stakeholder group and research activity. Twenty-three participants identified with more than one role and thirteen participated in several research activities. ACTRC documents report 85% of staff and educators identified as having lived experience. Routinely collected enrolment data indicated students represented a mix of backgrounds () with many “wearing multiple hats”. ACTRC progress reports indicate high demands and completion rates (Brophy et al, Citation2022).

Table 1. Participant numbers by stakeholder group for each data collection method (n = 82).

Table 2. Backgrounds of students attending ACTRC (May 2019 to March 2020).

demonstrates the age and gender of participants by research activity. A small number of participants identified as non-binary or genderqueer and some chose not to report their gender.

Table 3. Age and gender of participants by data collection method (n = 82).

Sixty-seven participants (82%) self-identified as Australian. Other ethnic identifications included North-West, Southern and Eastern European; South-East, North-East, Southern and Central Asian; Other Oceanian; and Sub-Saharan African. Participant demographics reflected a similar pattern of participation to the overall student group at the ACTRC, as reflected in routinely collected data (Brophy et al., Citation2022).

Quantitative results

Overall, the findings from the DREEM and the MASS were very positive; indicating high levels of satisfaction with the ACTRC among students. Details about the MASS findings are reported elsewhere (Brophy et al., Citation2022).

The developing recovery enhancing environment measure (DREEM)

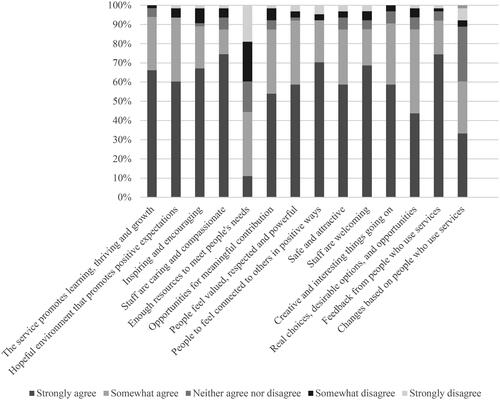

Participants who completed the DREEM (n = 74) were very positive, with more than 70% strongly agreeing that the ACTRC is “safe and attractive”, and staff are “compassionate” (). The domain addressing resources was reported as an area of improvement with only 10% of participants agreeing the ACTRC was sufficiently resourced.

Qualitative findings

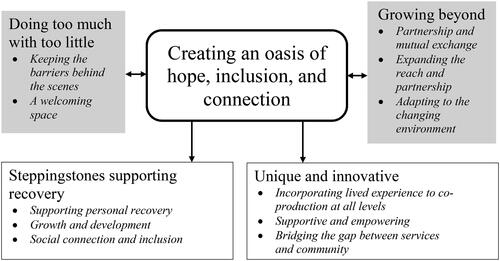

Creating “an oasis of hope, inclusion and connection” emerged as the central theme from the qualitative data that represents the sense of growth, hope, and connectedness within and beyond the college. The theme included four interrelated categories: 1) steppingstones supporting recovery; 2) creating a unique and innovative space; 3) doing too much with too little; striving and thriving within constrained resources; and 4) growing beyond through expanding the reach and partnerships (). These categories are presented with illustrative quotes below.

Table 4. Core categories and themes.

Steppingstones supporting recovery

The findings highlights that the ACTRC provided “steppingstones” that supported recovery, growth and inclusion for students and educators. Students spoke of experiencing personal growth through their participation in the ACTRC courses:

“I wasn’t sure recovery was possible in my case. I can see changes I’m making in my life and positive progress I’ve already made.” (Survey, student)

“[The college can] provide a space which springboards them into exploring options for improved mental health and recovery.” (Online survey participant, supporter)

“That is almost where the big gains are because someone comes in and says, “Well, I might like to learn something about recovery,” and then ends up feeling so confident and empowered […] that they then go onto teach those courses.” (Interview, educator)

Students, educators, and staff also described the ACTRC as a welcoming and inclusive space for “anyone regardless of if [they’re] a student or not, or lived experience or clinician” (Interview, educator). The college environment facilitated connections within the ACTRC and wider community. Friendship was described by a number of participants as an example of connectedness and inclusion. Students also valued opportunities to meet with others, share their experiences and attend social events, describing the ACTRC as a safe and non-judgemental space that helped them to “re-enter the universe” (Focus group, student). ACTRC offered courses to anyone interested in learning about mental health. The healthcare professionals who participated in the courses also benefited from the college in learning about living the experience of mental illness through a lived experience lens:

“[Healthcare professionals] can walk away with knowledge of being around mental health people, they get an idea what and how others feel, and they get a certificate. So [I] think, they get more than what they would get if they went to [an education institute].” (Interview, student)

“Recovery College opened up the opportunity to me to know the people in [the] Hockey team.” (Interview, student)

Creating a unique and innovative space

Participants described the ACTRC as a unique and innovative space that encouraged a shared learning environment that may not be available at other mental health services:

“…it offers a unique opportunity for people living with mental ill health, and those who care for them, to come together and learn about relevant topics and learn skills to aid recovery and wellbeing for free.” (Survey, student)

“…there isn’t another form of activity that just gives you that safe, not really guided but the guidance is there if you want it. […] [My daughter]’s a very different person now.” (Interview, supporter)

“We’re providing an opportunity for people to come to learn about their mental health… give them invaluable tools that they can utilise in order to sustain going on and thriving, not just surviving day to day. […] We’re bridging that gap between crisis care and recovery.” (Focus group, staff)

“[The ACTRC] provides a safe environment, where barriers to participation are taken into account and people are treated with respect, no matter what their needs are. Mental health issues are normalised, and don’t feel like such a “problem” or something to be ashamed of.” (Survey, educator/student)

Participants described the ACTRC as an empowering space, that offers choice and determination, and encourages shared decision making and power-sharing through the process of co-production. One staff member emphasized the positive impact of engaging with people with lived experience in the ACTRC:

“…definitely people with lived experience have equal voice to professionals in the college. […] I think it helps most of us… all of us staff have lived experience, as well, so we sit in both buckets” (Interview, staff).

Doing too much with too little

“Doing too much with too little” represents the ACTRC’s efforts towards striving and thriving within constrained resources. Staff and educators spoke about doing “a lot of work behind closed doors” (Interview, staff) to ensure resource limitations did not impact the delivery of courses:

“I think [of] the product of the college, of being there for students […] it’s working really well. But the duck is just paddling its little feet off just below the water […] We were just working our tails off, just trying to get courses up and running” (Interview, educator).

Growing beyond

“Growing beyond” represents the ACTRC’s ongoing endeavours to work collaboratively with organisations within ACT, expanding its reach and recognition, and adapting to changing conditions. Participants spoke positively about partnerships with several organisations within the ACT, for example in co-delivering courses. Some talked about hosting student placements as a mutually beneficial partnership that enabled them to expand their reach:

“We’ve had three or four rounds of students that have come on board and done their community service placement here […] That partnership has worked well. And we get a lot of referrals from those connections” (Interview, staff).

The ACTRC continued to operate and adapt during the COVID-19 pandemic, running online courses, providing social and emotional support for students, and encouraging them to stay connected. This has a potential for future Recovery Colleges to consider the value of online courses that can be offered to a broader range of students, encouraging them to stay connected and addressing access barriers (e.g. transport), although not ideal for everyone.

“[The ACTRC] worked really hard to get over the barriers of COVID. …They did a whole session that was a practice run of getting everybody on [Zoom] and testing it out, figuring out what all the buttons meant.” (Interview, external stakeholder)

Discussion

The findings from this evaluation project add to previous knowledge by highlighting the role of Recovery Colleges in creating a unique and inclusive space, steppingstones towards recovery and participation, and a shared learning environment facilitating co-production (Hall et al., Citation2018; McGregor et al., Citation2014; Sommer et al., Citation2019; Thériault et al., Citation2020; Toney et al., Citation2018) ().

Figure 2. Themes and categories; ACTRC offered steppingstones and a unique and innovative space promoting recovery through thriving within constraints and growing beyond by developing partnership and expanding the reach.

High levels of satisfaction, that were reported by students in both quantitative and qualitative findings, describe the ACTRC as an innovative, unique and empowering learning environment. Students and other stakeholders in this study emphasised the ACTRC filled a gap not previously met by mental health services in the ACT. Participants generally felt that the ACTRC was a safe space to not only share their stories but also to help others.

Critically, this study adds to the existing evidence by highlighting the role of the Recovery College in creating an inclusive space that valued service-users’ experiential expertise and offered opportunities for personal growth (Dalgarno & Oates, Citation2018; Thériault et al., Citation2020; Toney et al., Citation2018). The fluidity between the roles of students, educators and staff members, often referred to as wearing “multiple hats” by a number of participants, demonstrates how the ACTRC integrated lived-experience into development and delivery of the courses. This has encouraged service-users to transit from “learner” to “expert” roles that fostered a positive identity and self-confidence as illustrated by several participants in this study. Re-establishing a positive identity is a key dimension of personal recovery (Leamy et al., Citation2011; Winsper et al., Citation2020). Several studies have also identified the transformative potential of Recovery Colleges in offering empowering and inclusive environments (Kay & Edgley, Citation2019; Sutton et al., Citation2019; Thériault et al., Citation2020; Toney et al., Citation2018).

Participants in this evaluation commonly referred to the ACTRC as providing steppingstones that empowered students to move forward in their personal recovery. This echoes findings from previous research that also used the “steppingstone” metaphor and described the role of Recovery Colleges in encouraging personal growth and confidence, empowering students to gain new skills, and paving the path towards participating in employment, education and volunteering (Hall et al., Citation2018; Muir‐Cochrane et al., Citation2019; Reid et al., Citation2020; Sommer et al., Citation2019; Thériault et al., Citation2020; Toney et al., Citation2018).

The ACTRC provided a safe space to establish meaningful connections within and beyond the college. Making friends, participating in social events and linking with community resources are a few examples. This adds to the existing evidence by demonstrating how Recovery Colleges can act as conduit for many people, who may be lonely and isolated, towards opportunities for social inclusion (Meddings et al., Citation2015; Sommer et al., Citation2018).

Despite the significant role of Recovery Colleges in supporting recovery and inclusion, this study identified some challenges for enacting this vision. Aligned with previous studies in the Australian context (Muir‐Cochrane et al., Citation2019), the Recovery College was seen as experimental or “new”. Comments from participants in this study demonstrated the additional burden of running the pilot program and within constrained resourcing, as also reflected in the findings from the DREEM. This may have contributed to potential overreliance on the voluntarism and good will of those with lived-experience. It is thus recommended that Recovery Colleges receive adequate funding to support the co-production, and operational and strategic planning functions central to achieving their purpose (see also Muir‐Cochrane et al., Citation2019; Reid et al., Citation2020).

Through co-production, educators from a range of backgrounds involved with the ACTRC had genuine opportunities to work collaboratively and share their expertise. However, workload demands on staff appeared to limit the potential impact of partnerships on recovery-oriented practice. This is in line with previous literature that suggested that implementing co-production and recovery in practice requires organisational commitment, power re-structure, and workforce training and support (Le Boutillier et al., Citation2011; Winsper et al., Citation2020). It is therefore important for Recovery Colleges to not only expand their reach within and beyond health services (Cameron et al., Citation2018), but also to invest in workforce development and support to ensure the co-production remains at the colleges’ core. Workforce support is also essential to ensuring sustainability and fidelity to the Recovery College model.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this mixed-methods evaluation was gathering data from various sources and participants with multiple roles. This has led to understanding the role of Recovery Colleges in promoting recovery, role transition, personal growth, partnership and social inclusion. Moreover, this evaluation facilitated a reflective dialogue between consumer researchers, researchers from social work and occupational therapy, and the ACTRC steering committee. The multidisciplinary nature of the research team has added to the depth of understanding and collaborative research process by integrating multiple perspectives and bringing together the unique knowledge and expertise from social work and occupational therapy; however, required time and investment to ensure consistency and collaboration.

Public health restrictions of COVID-19 impacted the evaluation positively and negatively. Researchers were able to offer more flexibility in scheduling interviews using videoconferencing technology. Also, a larger number of participants completed the online survey than anticipated. However, the shift to online delivery of courses and evaluation methods may have excluded participants unfamiliar with online technologies. Efforts to address this included distribution of paper flyers when face-to-face courses resumed; text message invitations; and telephone interviews.

As encountered in other evaluation studies (Hall et al., Citation2018), recruiting supporters was challenging, though somewhat mitigated by the multiple channels for participation such as survey, online or phone interviews. Another consideration was the limited cultural and linguistic diversity of participants and representation of First Nations Australians in this study, which was reflective of the current student group of the ACTRC (for details see Brophy et al., Citation2022), but remain areas of attention for future evaluations. Recovery Colleges are, hence, encouraged to explore opportunities for broader gender and cultural diversity among students, supporters, educators, and external stakeholders.

The aspiration of co-production was actively pursued throughout the project; however, funding requirements, timelines, and ethics procedures imposed limits on opportunities for seeking participants’ inputs on the project design prior to ethics application.

Conclusion

This evaluation study reiterates Recovery Colleges as an innovative and important complement to mental health services. In particular, the role of co-production in creating inclusive and empowering spaces for healing and transformation, not found in other mental health services, was underlined. Adequate resourcing is essential in realising the full potential of co-production for students and partnering organisations, ensuring sustainability and fidelity to core principles of the Recovery College model.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support of the ACT Recovery College Co-design Committee and co-chairs, [removed], for their invaluable guidance. We also thank the Recovery College staff for assisting with recruitment, the participants for sharing their insights, and Megan Jacques and Nina Whittles who contributed to the literature review.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bourne, P., Meddings, S., & Whittington, A. (2018). An evaluation of service use outcomes in a Recovery College. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 27(4), 359–366. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1417557.

- Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brophy, L., Doroud, N., Hall, T., Minshall, C., Jordan, H., King, A., Zirnsak, T, Whittles, N., & Jacques, M. (2022). ACT Recovery College Evaluation. Final Report. La Trobe. Report. La Trobe University. doi: 10.26181/17148863.v1.

- Bryant, A., & Charmaz, K. (2007). Introduction Grounded theory research: Methods and Practices. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage handbook of grounded theory (pp. 1–28).

- Cameron, J., Hart, A., Brooker, S., Neale, P., & Reardon, M. (2018). Collaboration in the design and delivery of a mental health Recovery College course: experiences of students and tutors. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 27(4), 374–381. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1466038.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Mixed methods procedures. In Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed., pp. 213–246). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Crowther, A., Taylor, A., Toney, R., Meddings, S., Whale, T., Jennings, H., Pollock, K., Bates, P., Henderson, C., Waring, J., & Slade, M. (2019). The impact of Recovery Colleges on mental health staff, services and society. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 28(5), 481–488. doi: 10.1017/S204579601800063X.

- Dalgarno, M., & Oates, J. (2018). The meaning of co-production for clinicians: An exploratory case study of Practitioner Trainers in one Recovery College. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 25(5–6), 349–357. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12469.

- Dinniss, S., Roberts, G., Hubbard, C., Hounsell, J., & Webb, R. (2007). User-led assessment of a recovery service using DREEM. Psychiatric Bulletin, 31(4), 124–127. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.106.010025.

- Doroud, N., Fossey, E., Fortune, T., Brophy, L., & Mountford, L. (2022). A journey of living well: a participatory photovoice study exploring recovery and everyday activities with people experiencing mental illness. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 31(2), 246–254. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2021.1952950.

- Ebrahim, S., Glascott, A., Mayer, H., & Gair, E. (2018). Recovery Colleges; how effective are they? The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 13(4), 209–218. doi: 10.1108/JMHTEP-09-2017-0056.

- Fortuna, K. L., Brusilovskiy, E., Snethen, G., Brooks, J. M., Townley, G., & Salzer, M. S. (2020). Loneliness and its association with physical health conditions and psychiatric hospitalizations in people with serious mental illness. Social Work in Mental Health, 18(5), 571–585. doi: 10.1080/15332985.2020.1810197.

- Hall, T., Jordan, H., Reidels, L., Belmore, S., Hardy, D., Thompson, H., & Brophy, L. (2018). A Process and Intermediate Outcomes Evaluation of an Australian Recovery College. Journal of Recovery in Mental Health, 1(3), 7-20. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/rmh/article/view/29573

- Kay, K., & Edgley, G. (2019). Evaluation of a new Recovery College: delivering health outcomes and cost efficiencies via an educational approach. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 23(1), 36–46. doi: 10.1108/MHSI-10-2018-0035.

- Le Boutillier, C., Leamy, M., Bird, V. J., Davidson, L., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). What does recovery mean in practice? A qualitative analysis of international recovery-oriented practice guidance. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 62(12), 1470–1476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.001312011.

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733.

- McGregor, J., Repper, J., & Brown, H. (2014). “The college is so different from anything I have done”. A study of the characteristics of Nottingham Recovery College. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 9(1), 3–15. doi: 10.1108/JMHTEP-04-2013-0017.

- Meddings, S., McGregor, J., Roeg, W., & Shepherd, G. (2015). Recovery Colleges: quality and outcomes. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 19(4), 212–221. doi: 10.1108/MHSI-08-2015-0035.

- Morgan, K. (2016). Patient and public involvement in research, why not? McPin Foundation, Talking Point Papers (Report No.2, Edition 1), McPin Foundation.

- Muir‐Cochrane, E., Lawn, S., Coveney, J., Zabeen, S., Kortman, B., & Oster, C. (2019). Recovery College as a transition space in the journey towards recovery: an Australian qualitative study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 21(4), 523–530. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12637.

- Perkins, R., Repper, J., Rinaldi, M., & Brown, H. (2012). Recovery Colleges. Centre for Mental Health.

- Pincus, H. A., Spaeth-Rublee, B., Sara, G., Goldner, E. M., Prince, P. N., Ramanuj, P., Gaebel, W., Zielasek, J., Großimlinghaus, I., Wrigley, M., van Weeghel, J., Smith, M., Ruud, T., Mitchell, J. R., & Patton, L. (2016). A review of mental health recovery programs in selected industrialized countries. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10(1), 73. doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0104-4.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). NVivo (released in March 2020). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Reid, N., Khan, B., Soklaridis, S., Kozloff, N., Brown, R., & Stergiopoulos, V. (2020). Mechanisms of change and participant outcomes in a Recovery Education Centre for individuals transitioning from homelessness: a qualitative evaluation. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 497. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08614-8.

- Ridgway, P., & Press, A. (2004). Assessing the recovery-orientation of your mental health program: A user’s guide for the Recovery-Enhancing Environment scale (REE). University of Kansas.

- Roper, C., Grey, F., & Cadogan, E. (2018). Co-production - putting principles into practice in mental health contexts. Creative Commons Attribution, University of Melbourne. https://healthsciences.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/3392215/Coproduction_putting-principles-into-practice.pdf

- Slade, M., & Wallace, G. (2017). Where are we now? Recovery and mental health. In M. Slade, L. Oades, & A. Jarden (Eds.), Wellbeing, recovery and mental health (pp. 24–34). Cambridge University Press.

- Sommer, J., Gill, K. H., Stein-Parbury, J., Cronin, P., & Katsifis, V. (2019). The role of Recovery Colleges in supporting personal goal achievement. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42(4), 394–400. doi: 10.1037/prj0000373.

- Sommer, J., Gill, K., & Stein-Parbury, J. (2018). Walking side-by-side: Recovery Colleges revolutionising mental health care. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 22(1), 18–26. doi: 10.1108/MHSI-11-2017-0050.

- Sutton, R., Lawrence, K., Zabel, E., & French, P. (2019). Recovery College influences upon service users: A recovery academy exploration of employment and service use. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 14(3), 141–148. doi: 10.1108/JMHTEP-06-2018-0038.

- Thériault, J., Lord, M.-M., Briand, C., Piat, M., & Meddings, S. (2020). Recovery colleges after a decade of research: A literature review. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 71(9), 928–940. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900352.

- Toney, R., Elton, D., Munday, E., Hamill, K., Crowther, A., Meddings, S., Taylor, A., Henderson, C., Jennings, H., Waring, J., Pollock, K., Bates, P., & Slade, M. (2018). Mechanisms of action and outcomes for students in recovery colleges. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 69(12), 1222–1229. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800283.

- Windsor, L., Roberts, G., & Dieppe, P. (2017). Recovery Colleges–safe, stimulating and empowering. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21(5), 280–288. doi: 10.1108/MHSI-06-2017-0028.

- Winsper, C., Crawford-Docherty, A., Weich, S., Fenton, S.-J., & Singh, S. P. (2020). How do recovery-oriented interventions contribute to personal mental health recovery? A systematic review and logic model. Clinical Psychology Review, 76, 101815. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101815.