Abstract

Purpose: To better understand patient perspectives on the life impact of spasticity.

Methods: Global Internet survey (April 2014–May 2015) of 281 people living with spasticity.

Results: Respondents indicated that spasticity has a broad impact on their daily-life: 72% reported impact on quality of life, 44% reported loss of independence and 44% reported depression. Most respondents (64%) were cared for by family members, of whom half had stopped working or reduced their hours. Overall, 45% reported dissatisfaction with the information provided at diagnosis; main reasons were “not enough information” (67%) and “technical terminology” (36%). Respondents had high treatment expectations; 63% expected to be free of muscle spasm, 41% to take care of themselves and 36% to return to a normal routine. However, 33% of respondents had not discussed these expectations with their physician. The most common treatments were physiotherapy (75%), botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT, 73%) and oral spasmolytics (57%). Of those treated with BoNT, 47% waited >1 year from spasticity onset to treatment.

Conclusions: This survey emphasises the broad impact of spasticity and highlights unmet needs in the patient journey. Improvements with regards to communication and the therapeutic relationship would be especially welcomed by patients, and would help manage treatment expectations.

Spasticity has broad impact on the lives of patients and their families that extends beyond the direct physical disability.

Patients with spasticity need to be well informed about their condition and treatments available and should be given the opportunity to discuss their expectations.

Physicians need to be aware of the patient’s individual needs and expectations in order to better help them achieve their therapeutic goals.

Implications of Rehabilitation

Introduction

The term “spasticity” refers to increased, involuntary, velocity-dependent muscle tone that causes resistance to movement. The condition commonly follows damage to the central nervous system and can be caused by a variety of disorders or traumas, such as a stroke, a tumour, cerebral palsy (CP), multiple sclerosis (MS) or a brain or spinal cord injury. Although fairly common, the diversity of aetiologies makes it hard to define the prevalence of spasticity. However, current estimates are that spasticity occurs in 17–38% of stroke survivors, 17–53% of MS patients, 40–78% of those with spinal cord injury and up to 34% of patients with traumatic brain injury.[Citation1]

The pattern of spasticity, both in terms of anatomy and severity, depends on the condition, age and onset of the lesion, its location and size, and thus no patient presents in the same way as another. This heterogeneity means that the rehabilitation process of patients with spasticity can often be very challenging. However, it is very important to manage spasticity because it is a significant contributor to functional impairment, reduced activities of daily living (ADL) and poorer quality of life (QoL).[Citation2,Citation3] As such, the management of spasticity plays an important role on the journey to autonomy, independence and increased self-esteem. However, the “life impact” of spasticity is often taken for granted by professionals and there is actually very little information about what matters most to the patient and their families. To date, most patient surveys in this field have been small and/or very focused on specific issues such as service provision [Citation4,Citation5] or satisfaction with specific treatments.[Citation6]

Health related quality of life has been defined as “the gap between our expectations of health and our experience of it”.[Citation7] Likewise, patient-centred approaches to care delivery are increasingly advocated by consumers and clinicians with the intent to improve patient satisfaction with their care.[Citation8] Consequently, in order to help patients to engage with their care plan and manage expectations of treatment it is vital that we understand the patients’ own perspective on the management of their spasticity, including how satisfied they are with their diagnosis, therapeutic relationship with their physician and their medical treatment. For this reason, an international online survey “Patients Living With Spasticity” was undertaken to assess patient views on the impact of living with spasticity with the aim of gaining insights into the impact of spasticity on different domains of patients lives, including physical and psychological aspects, identifying unmet needs in patient care and highlighting where improvements in the management approach may be required.

Methods

Survey design

This international online survey was conducted between April 2014 and May 2015. The structure and contents of the survey were designed in collaboration with World Federation for NeuroRehabilitation (WFNR), and the survey was supported by an unrestricted grant from Ipsen Pharma. The survey was designed to be self-completed by the patients, it was first designed in English, and then translated in French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Polish, Russian and Spanish.

The survey was hosted online and included four demographic screening questions and 25 disease related questions grouped into categories (Supplementary appendix). All questions were asked in the context of spasticity, however since this term may not be familiar to patients, the questions were phrased in relation to “muscle stiffness or muscle spasm”. The questions were multichoice, and 17 included a free entry format as one of the options. Survey responses were anonymous. The survey was designed to take approximately 15–20 min to complete, however there was no set time limit for completion.

Survey participants

People with spasticity were encouraged to participate in the survey by their treating healthcare professional (HCP). The WFNR advertised the availability of the survey to their member physicians by regular email flyers every 6 weeks and there was a permanent link to the survey on the WFNR website. The survey was announced at the World Congress of NeuroRehabilitation 2014 to all attending physicians and also discussed at a number of other neurorehabilitation congresses by discussing the survey design in symposia. Other than having a diagnosis of spasticity, there were no formal inclusion or exclusion criteria for participating in this survey.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise all survey data collected in this study.

Results

Sample

Over the 13 months that the Living With Spasticity Patient Survey was available online, 281 respondents from 29 countries and four continents completed the survey. Respondents were not equally distributed between countries; 22 of 29 countries had representation from <10 respondents. Survey respondents were almost equally split between the genders (52% female and 48% male) and two thirds (66%) were aged less than 54 years old (). Respondents had spasticity of various origins; the most common aetiology (47%) was post-stroke spasticity. Almost half (49%) of respondents indicated that their lower limbs were affected, 44% reported upper limb spasticity and 13% said their whole body was affected.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics.

Impact of spasticity on daily living

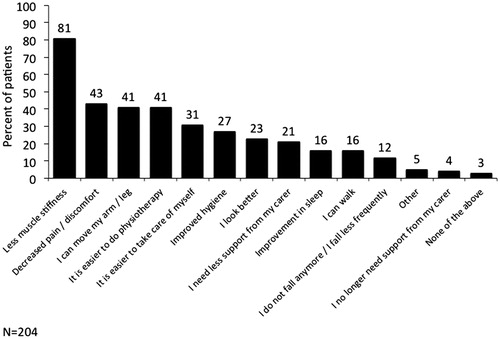

In terms of employment, 37% of respondents were employed (full time [18%], part time [9%], self-employed [7%], full time student [3%]), 15% were retired and 10% were not currently employed; 38% responded that they were unable to work/disabled. When asked how their spasticity affected them, 72% reported impact on their overall QoL, 44% reported a loss of independence and the same percentage (44%) reported depression and mood alterations; only 3% of respondents reported no impact on their lives ().

Figure 1. Impact of spasticity on daily life (a) and patient daily life (b) impact on family carers.

The impact of spasticity was not limited to the person with the condition. Almost two thirds (64%) of respondents reported being cared for by a family member, half of whom (n = 89) had made a change to their working life [changed working hours (35%) or even stopped working (15%)]. Few respondents (7%) said they had a carer who visits on a regular basis, 22% said that they did not require support and 7% said they needed support but did not know where to get it ().

Therapeutic relationship, information provided and self-management

The majority of respondents were first seen by a neurologist (53%) or rehabilitation specialist (22%); other HCPs involved in first discussions about spasticity included: general practitioners (GPs) (12%), physiotherapists (4%) and nurses (2%). When first discussing spasticity with their healthcare professional, just over half (55%) of respondents said they were satisfied with the information they received about their condition and its treatment options. Of those who reported dissatisfaction with the information provided (n = 127), 67% wanted more information, 36% felt the specialist used too many technical words or there were problems with communication and 35% said they wanted more time with their doctor to better understand their diagnosis and its future consequences. Conversely, a small number (n = 6, 5%) said they were overwhelmed by the information provided. After diagnosis, around half (53%) of all respondents looked for more information on the Internet, and 47% looked to their GP for more information. Overall, 51% of respondents reported receiving written support materials (leaflets and brochures 34%, information from a computer given by the HCP 20% and patient/support group details 15%).

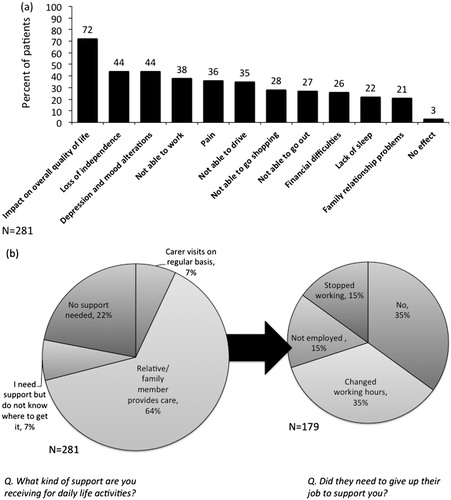

During appointments with their physicians, 67% of respondents said that they had discussed treatment expectations. Patient expectations of treatment were high, with 63% expecting freedom from spasms and 41% expecting to regain independence (take care of myself). About a third (36%) expected to be able to return to a normal routine ().

Figure 2. Expectations of treatment following discussion with a doctor. Base =187 patients who had discussed expectations regarding treatment.

Respondents reported that they usually gave feedback to their HCP by: arranging another appointment (n = 207, 74%) and calling or writing/emailing the HCP (26%). A minority (n = 42, 15%) said that they were not asked to provide feedback about their treatment. Relatively few (n = 39, 14%) respondents had contacted a patient association during the course of their disease, but most of these (n = 33, 85%) would recommend patient societies to other patients.

Treatment of spasticity

Most respondents (75%) reported receiving physiotherapy/physical therapy. Other non-pharmacological therapies included: massages (43%), active or passive stretching and regular light exercise (41%), splinting or corrective footwear (38%), postural advice (21%) and managing factors that make the spasticity worse (12%). Overall 15% of respondents had received psychological counselling/support and 6% said they were advised to use stress reduction techniques.

With regards to medical treatment, most (73%) had been treated with botulinum toxin (BoNT) injections, 57% were prescribed oral medications and 4% had intrathecal baclofen therapy. Although the main reason for not being prescribed treatment with BoNT was that the HCP did not propose it as a treatment (56% of the 77 respondents not prescribed BoNT), there were many issues regarding access to treatment reported (too expensive for the patient 13%, too expensive for healthcare provider 10%, not available in country 4%, travel inconvenience 4%, lack of access to an experienced injector 4%).

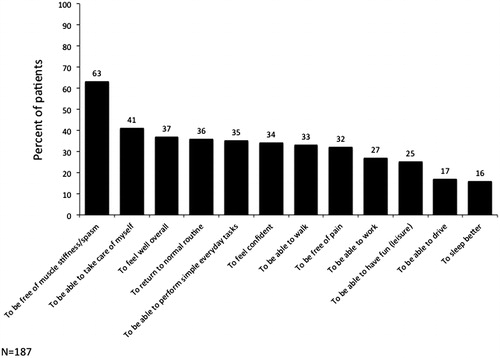

Of the respondents who reported receiving BoNT (n = 204), the majority (80%) reported that they had discussed the potential benefits and side-effects of treatment with their doctor. With regards to the start of the BoNT treatment, just over half (53%) of respondents reported receiving their first BoNT injection within a year of developing spasticity, a quarter (23%) received BoNT treatment within 1–3 years and the same proportion (23%) waited more than 3 years for their first injection. Regarding the duration of BoNT effect, overall, almost half of respondents (49%) said it lasts 3–4 months, while a quarter (25%) said it lasts 4–6 months, and 24% said their BoNT treatment lasted for less than 3 months. A small number of respondents (2%) reported the effects lasting for more than 6 months. Since receiving treatment with BoNT, the vast majority (89%) of respondents reported symptom improvement. However, there were some respondents who reported either no improvement (9%) or worsening of symptoms (2%). The main reported benefit of BoNT treatment was less muscle stiffness/muscle spasm in the affected area (). Of the 22 respondents who did not report symptom improvement, 41% said it “did not work for me”, 18% reported side effects and 14% reported disagreement with the HCP on what needed to be done.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this International Patient Survey is the first and largest survey undertaken to collect patient’s own perceptions of their spasticity management. The survey was purposefully designed to be broad in scope, asking questions about life impact, therapeutic relationships with HCPs as well as treatment and expected treatment outcomes. In line with clinical studies, the survey found that the signs and symptoms associated with spasticity significantly impact on several aspects of daily life and highlight the importance of managing the full range of problems a person living with spasticity might suffer.

The survey results confirm that the presence of spasticity is associated with worse QoL and loss of independence. These ‘direct’ effects are relatively well recognised and are therefore more likely to be discussed when a patient visits their HCP. However, the survey also shows that significant proportions of patients also have other problems including depression or mood alterations and financial difficulties. The broad range of reported problems emphasises the need to ask our patients about the full range of their problems. It also reinforces the need to work within a multidisciplinary environment, which should include access to mental health and social services. In addition, the results clearly demonstrate the fact that spasticity not only impacts the person with spasticity, but also their family members. A relative cared for almost two thirds of respondents, and many of these informal carers had either stopped working or changed their working hours. Considering the significant health and economic burdens associated with caregiving,[Citation9,Citation10] it is vital a comprehensive approach to spasticity management also considers ways to ensure that carers are properly supported within the healthcare system.

The present findings also reveal an international need for a better therapeutic relationship and information sharing between people living with spasticity and their HCPs. In this survey, most health care contacts seemed to be with single professionals rather than specialized teams. Physicians, nurses and therapists should be a key source of information for their patients, and a team approach may increase levels of satisfaction with the information provided at diagnosis. Importantly, respondents appeared to have relatively high expectations of treatment, with 63% expecting to be “free” of spasms and 41% hoping for independence, yet a third reported that they had not discussed treatment expectations with their HCP. While such aspirations may be possible for some patients, it is important that patients are quickly made to understand that spasticity is typically a life-long symptom of their central nervous system damage. Although there are effective treatment options for spasticity, there is currently no complete cure. Therefore, discussing the patient expectations and explaining what can realistically be achieved might improve patient satisfaction with care and also help to prevent secondary depression. With the ever-increasing time restraints imposed on HCPs it is obviously important to find a good balance between patient assessment and information provision. In this respect, the development of a goal setting approach is being forged in the field of neurorehabilitation.[Citation11–13] Under this approach, HCPs discuss the goals of treatment with the patient (and caregivers), explaining what can realistically be achieved with the proposed treatment. As such, goal-setting is a complex interaction in which HCPs can help educate participants regarding the goals of the proposed treatment. The process not only offers a method of documenting treatment effectiveness, but also offers an opportunity for dialogue and negotiation between the patient and the treating team thereby engaging the patient in their own care and establishing expectations for the outcome.[Citation14,Citation15]

Another important aspect of HCP communication identified by this survey is the need to use terminology that can be understood by the patient and their carers and family members. Use of complicated terminology was cited as a key reason for dissatisfaction with information provision. Previous studies have found that patients typically use words reflecting muscle tone and spasms to describe spasticity.[Citation16] For this reason, although the survey was entitled “Patients Living With Spasticity”, all questions were worded in the context of their “muscle stiffness” and/or “muscle spasm”.

With regards to information provision, the results of this survey indicate two potential opportunities for development. First, only a third of respondents indicated that they had been provided with leaflets or brochures to help explain the condition. The development of easy to read and understand patient literature that is made widely available in the relevant treatment settings (e.g. physician office and therapist centres) would be one way to address the communication gap. Such materials could even be developed for use in the clinic visit, helping the treating physician explain spasticity, its potential consequences and treatment to the patient and their carers. Second, although the respondents in this study were living with chronic diseases, there was a relatively low use of patient societies. However, of those who were in contact with patient societies, most would recommend them to others. While there are no well-recognised support groups for people living with “spasticity”, it is a symptom of many chronic conditions that do have well-established support mechanisms in place and patients undergoing rehabilitation could be directed to these. The percentage of patients who used the Internet and other media to research their condition is in line with the literature [Citation17] and is consistent with feelings of dissatisfaction with the amount of information provided at clinic visits. In the age of patient-centred healthcare and almost unlimited information, it is important that treating physicians acknowledge patients' need for detailed information, that they discuss the information offered by patients and guide them to reliable and accurate health websites.

In accordance with current guidelines, the majority of patients reported receiving physiotherapy/physical therapy, which is well established as the backbone of rehabilitation for patients with spasticity.[Citation18,Citation19] The use of BoNT was equally high in this survey, which is also in line with guidelines for its use in spasticity management.[Citation18] Of those patients who did not receive BoNT, the main reason was that it was “not proposed by my physician”. Not all patients are suitable for BoNT injections, and it may be reasonable to assume that these patients were not good candidates for therapy. However, the survey also indicated several issues with patient access to treatment; these included costs to healthcare providers or patients (Russia, UK and USA), and access to experienced injectors (Russia and Croatia). It is also of note that almost half of respondents reporting waiting at least a year after developing symptoms of spasticity (23% received it more than 3 years after their symptoms developed). This in contrast to recent studies in post-stroke patients indicating potential benefits of very early intervention (injection within 6 weeks–3 months).[Citation20–22]

Limitations of this study are those inherent to patient surveys, which are based on the patient’s own understanding of their condition, and are not compared with objective clinical information (e.g. about symptom severity, or response to treatment). For example, 16% of respondents indicated that they had spasticity of aetiology not on the multi-choice list of answers (denoted as “other”). Closer inspection of their individual free-form responses shows that many of these patients had post-stroke spasticity, but used terms such as “cerebrovascular event”, indicating that they did not recognise the terminology. Another important limitation is the method of recruitment, as the survey was advertised to WFNR member physicians who then encouraged their patients to participate. It may be that physicians pre-selected patients who were most able to complete such a survey – thereby discounting older patients who might not have had Internet access, or cognitively affected patients. Some sort of selection bias is indicated by the young age of the survey respondents (64% were aged less than 54 years old) despite the fact that half of respondents had a stroke (nearly 75% of all strokes occurs in people aged over 65 years old). Likewise, most individual countries had representation from <10 patients, which not only limits the generalisability of data, but also prevented any analysis of potential differences between countries.

Although all questions were framed in relation to “muscle spasm” and “muscle stiffness”, it is important to consider that many of the survey respondents (especially the respondents with MS) likely had other disabling symptoms, which may have impacted on the way they answered how spasticity impacts their daily life. In addition, the parameters of the online tool used meant that we were unable to perform detailed analyses of answers where patients could tick more than one answer. For example, it would be of interest to understand which treatments were commonly used together.

Despite these limitations, this international survey provides key insights that may help improve the management experience for patients living with spasticity. The survey emphasises the broad impact of spasticity and identifies unmet needs in the patient journey – especially with regards to the therapeutic relationship and communication. Patients with spasticity need to be better informed about their condition and should be given the opportunity to discuss their expectations.

Funding information

Medical writing support was provided by Anita Chadha-Patel (ACP Clinical Communications, London, UK), and Ipsen Pharma supported the survey, data analysis and preparation of this report. M. B. has nothing to report. SK reports personal fees from Allergan and Ipsen for providing training. M. M. F. reports personal fees for consultancy from Ipsen, Merz Pharma and Allergan, and participation in speaker’s bureau for Merz Pharma, and Allergan. J. B. is an employee of Ipsen. K. F. reports research support from Ipsen and Merz Pharma, personal fees for consultancy from Ipsen, Merz Pharma and Allergan, and participation an Ipsen speaker’s bureau.

downloadFromZipFile.pdf

Download PDF (92.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank World Federation for NeuroRehabilitation and all the patients who participated in this survey. We thank Alison Doughty, Zoey Jackson and Anna Hoang (Inspired Science) for supporting the online survey and data collation.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Esquenazi A, Albanese A, Chancellor MB, et al. Evidence-based review and assessment of botulinum neurotoxin for the treatment of adult spasticity in the upper motor neuron syndrome. Toxicon. 2013;67:115–128.

- Doan QV, Brashear A, Gillard PJ, et al. Relationship between disability and health-related quality of life and caregiver burden in patients with upper limb poststroke spasticity. Pm R. 2012;4:4–10.

- Welmer AK, von Arbin M, Widen Holmqvist L, et al. Spasticity and its association with functioning and health-related quality of life 18 months after stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21:247–253.

- Sakel M, Mackenzie R. Patient satisfaction with botulinum txin therapy in adult spasticity. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2009;16:280–288.

- Mahoney JS, Engebretson JC, Cook KF, et al. Spasticity experience domains in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:287–294.

- Bensmail D, Hanschmann A, Wissel J. Satisfaction with botulinum toxin treatment in post-stroke spasticity: results from two cross-sectional surveys (patients and physicians). J Med Econ. 2014;17:618–625.

- Carr AJ, Gibson B, Robinson PG. Measuring quality of life: is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ. 2001;322:1240–1243.

- Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:351–379.

- Collins LG, Swartz K. Caregiver care. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:1309–1317.

- Viana MC, Gruber MJ, Shahly V, et al. Family burden related to mental and physical disorders in the world: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013;35:115–125.

- Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:362–370.

- Turner-Stokes L, Williams H, Johnson J. Goal attainment scaling: does it provide added value as a person-centred measure for evaluation of outcome in neurorehabilitation following acquired brain injury? J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:528–535.

- Turner-Stokes L, Fheodoroff K, Jacinto J, et al. Upper limb international spasticity study: rationale and protocol for a large, international, multicentre prospective cohort study investigating management and goal attainment following treatment with botulinum toxin A in real-life clinical practice. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002230.

- Ward AB, Wissel J, Borg J, et al. BEST Study Group. Functional goal achievement in post-stroke spasticity patients: the BOTOX® Economic Spasticity Trial (BEST). J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:504–513.

- Schoeb V, Staffoni L, Parry R, et al. “What do you expect from physiotherapy?”: a detailed analysis of goal setting in physiotherapy. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36:1679–1686.

- Bhimani RH, McAlpine CP, Henly SJ. Understanding spasticity from patients' perspectives over time. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:2504–2514.

- McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: how this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63:24–28.

- Royal College of Physicians (UK). Spasticity in adults: management using botulinum toxin. UK: Royal College of Physicians; 2009.

- Wissel J, Ward AB, Erztgaard P, et al. European consensus table on the use of botulinum toxin type A in adult spasticity. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:13–25.

- Tao W, Yan D, Li JH, et al. Gait improvement by low-dose botulinum toxin A injection treatment of the lower limbs in subacute stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27:759–762.

- Rosales RL, Kong KH, Goh KJ, et al. Botulinum toxin injection for hypertonicity of the upper extremity within 12 weeks after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012;26:812–821.

- Fietzek UM, Kossmehl P, Schelosky L, et al. Early botulinum toxin treatment for spastic pes equinovarus – a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:1089–1095.