Abstract

Purpose: Parents’ attendance, participation and engagement are thought to be critical components of children’s rehabilitation services; however, these elements of therapy are typically under-investigated. The purpose of this study was to develop a substantive theory of parents’ attendance, participation and engagement in children’s rehabilitation services.

Methods: A constructivist grounded theory study was conducted. Data collection included interviews with parents (n = 20) and clinicians (n = 4), policies regarding discharge, and child-health records. Data was analyzed using constant comparison, coding and memoing. To promote credibility, authors engaged in reflexivity, peer debriefing, member checking, triangulation and recorded an audit trail.

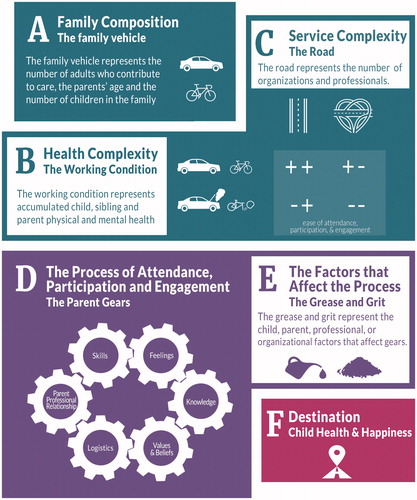

Results and conclusions: The Phoenix Theory of Attendance, Participation and Engagement was developed. This theory is described metaphorically as a journey to child health and happiness that has six components including: parent’s feelings, skills, knowledge, logistics, values and beliefs and parent’s relationship with the professional. The child, parent, service provider, and organizational factors that impact engagement are described. Service providers, policy makers, organizational leaders and researchers can use this information to promote engagement in children’s developmental rehabilitation services.

Introduction

Parent attendance, participation and engagement are necessary components of children’s developmental rehabilitation therapy (children’s therapy), including physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech-language therapy services. Typically, these therapy services aim to integrate principles of family-centered care that require parent-service provider collaboration in order to promote child development [Citation1–3]. A systematic review examining the use of family centered service in medical, nursing, sociology and psychology literature reported that family-centered services increase access and efficient use of services, and improve health status and satisfaction with care [Citation1]. Under-investigated elements of family-centered service include parent attendance [Citation4], participation [Citation3,Citation5] and engagement [Citation6–8].

Non-attendance at children’s health care appointments is thought to limit the efficacy and efficiency of the service and raise questions about child safety [Citation4]. Attendance has also been used to indicate participation, engagement, adherence and compliance [Citation5]. However, nonattendance does not necessarily mean that a family is lacking participation or engagement, as various factors may account for missed appointments, ranging from organizational barriers (e.g., poor communication with families and inadequate staffing) to family barriers (e.g., lack means to travel to appointments, forget about appointments) [Citation4,Citation9,Citation10]. Additional barriers concern the quality of the interaction between the family and the service provider, with families being less likely to attend if the parents feel judged or that their children are ignored during appointments [Citation4,Citation11]. Service providers who have well-developed interpersonal and therapeutic skills can help to mitigate these barriers and promote equitable access to services with improved family engagement.

Parents who participate in children’s therapy services identify that therapist communication is the primary way to promote parent participation in all stages of therapy [Citation3]. Communication skills are considered to be a key component of therapists’ best practice that can improve the effectiveness of therapy interventions and increase satisfaction with services [Citation12]. Effective communication can help parents to negotiate their role within their child’s services. For example, mothers in an infant development program clearly identified their primary role as a learner and their expectations of professionals to be knowledge translators, supporters and systems navigators [Citation13]. Good communication between parents and professionals also promotes parent involvement in goal setting, which increases parents’ feelings of competence and partnership [Citation14] and allows them to focus on their priorities, namely child happiness via fulfillment and acceptance [Citation15]. Therapists’ abilities to focus on these holistic goals and provide flexible services to promote engagement depends on their level of expertise [Citation16]. Forsingdal et al. [Citation17, p. 588] fully explore the factors that influence mothers’ involvement in goal-setting and their collaboration and engagement in children’s therapy services, stating that “engagement itself should be a therapeutic goal”.

Although parent engagement is considered to be a central element in children’s therapy services it has been poorly defined, with minimal investigation by which to understand or promote engagement [Citation6–8,Citation18]. Current conceptualizations of parent engagement, developed from the mental health literature, identify affective, behavioral and cognitive components of engagement such that “engagement is an optimal state comprised of a hopeful stance, conviction with respect to the appropriateness of intervention goals and processes, and confidence in personal ability to carry out the intervention plan” [Citation8, p. 6]. Researchers have started to use this conceptualization of engagement within rehabilitation therapy [Citation7], but have yet to report parents’ perspectives on the meaning of attendance, participation and engagement in children’s rehabilitation.

The purpose of this grounded theory study was to develop a substantive theory to explain how parents attend, participate and engage in their children’s developmental rehabilitation therapy service. The theory is presented in two papers, the first is titled “Parent engagement in children’s developmental rehabilitation services: Part 1. Contextualizing the journey to child health and happiness”. This paper describes the child, family and service conditions that impact the ease with which attendance, participation and engagement may occur. Reading Part 1 of this theory first will provide an important context in which the results presented in this paper, Part 2, can be best understood and appreciated. The goal of this work is to provide a theory that service providers, parents, organizational management and policy makers can all apply to promote attendance, participation and engagement in children’s therapy services.

Methods

Key methods information is included below and additional details can be accessed in Part 1 of this theory. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (December 23, 2015) and the Children’s Therapy Centre (CTC) ethics committee.

A constructivist grounded theory study was undertaken in order to inductively derive a theory of how parents participate and engage in their child’s therapy service [Citation19–21]. This approach includes the key features of grounded theory (e.g., constant comparison, cyclical and inductive data collection and analysis) and posits that the theory generated will reflect a combination of the participant’s and researcher’s own experiences and socially constructed understanding of the world [Citation21]. An audit trail was developed to enhance dependability by recording the project decisions and steps [Citation22].

Sampling

Recruitment was done at one community-based CTC in Ontario, Canada, where publicly funded rehabilitation services (e.g., occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech-language therapy and social work) are provided to children who have a developmental delay or disability. The first author was employed clinically at this center and practiced reflexivity to account for her influence and potential bias throughout the study [Citation23].

Initially purposeful sampling was used to recruit mothers and fathers who had attended at least one therapy session at the CTC for their child who was 0–6 years old. Throughout the study theoretical sampling was employed to identify areas of analysis that required additional data from individuals with a specific experience (e.g., families with a history of missed appointments) [Citation24,Citation25]. Critical case sampling was used to identify clinicians at the CTC who practiced clinically and in leadership positions in social work, occupational therapy, speech language pathology and physical therapy.

Sample

Twenty parents and four clinicians participated in the study. The parents included 15 mothers and 5 fathers from 18 unique families. Families were required to speak English to participate in the study, however 4 also spoke another language at home. The participants varied with respect to income, education, martial status, and employment. All children had at least one area of developmental delay and seven children had a formal medical diagnosis (e.g., Down Syndrome, Autism Spectrum Disorder). 12 children were involved with more than one discipline at the CTC and 10 children used additional community-based services (e.g., home care, hospital care, or private therapy services). Additional details about the sample are available in Part 1.

Data collection

Data was collected between January 2016 and February 2017. Parents completed the initial interview at their home or in the community and follow up interviews were completed by phone. A total of forty parent interviews and 4 clinician interviews were completed. Parents and clinicians completed a demographic form at the time of their initial interview. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, with the exception of one initial interview in which the parent was not comfortable being recorded and notes were taken instead. All transcripts were stored and coded using a qualitative software program, NVivo 10. Field notes were recorded after every interview.

Two additional data sources were collected in order to triangulate the parent interview data. Data was extracted from the children’s electronic health care record regarding the appointments attended, types of services received, reasons for missed appointments and methods for communicating with the family. In order to understand the broader context in which children’s rehabilitation services are provided, 90 policy and procedure documents regarding discharge for reasons of non-contact or missed appointments were collected from 18 of the 21 CTCs in Ontario. 3 centers did not respond to the request for documents.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis were done concurrently using inductive and iterative processes to guide theoretical development. To begin analysis all authors separately reviewed the first transcript, then met with the first author individually to discuss initial impressions and potential codes. From that point onwards the first author completed all coding beginning with an open coding phase in which short, active, descriptive labels were assigned to small segments of data [20]. The method of constant comparison, central to grounded theory, was used to compare data to data within a transcript, between transcripts using child codes, between child codes to build parent codes, and within and across parent codes to build categories [Citation26–28].

A focused coding phase was completed during which related codes were grouped together and the total number of codes being pursued was reduced in a process described by Glaser and Strauss [Citation28] as ‘delimiting the theory’, with attention given to codes that showed potential for theoretical reach, direction and centrality [Citation20]. Memo writing and diagraming were used to develop the properties, dimensions, and relationships between each code and category [Citation20,Citation29]. Memo writing encourages the researcher to enter an ambiguous space where concepts can be explored and refined, and new analytic leaps are welcome through the process of abduction [Citation20,Citation30]. In addition to memo writing the first author enhanced the credibility and theoretical strength of this work by peer debriefing with committee members, academic and clinical colleagues [Citation22]. Member checking was done with all parent participants during follow up interviews in which they reviewed and commented on the emerging theory and provided information on any elements that were unclear. Data collection ended when theoretical saturation was achieved, meaning no new theoretical categories were being described and existing categories were fully defined [Citation25]. The clinician interview data, child health records, and policy documents were used to triangulate the parent interview data and promote credibility of the results [Citation22,Citation31].

Results

The Phoenix Theory of Attendance, Participation and Engagement can be viewed metaphorically as a journey towards child health and happiness (). The conditions that affect families’ journeys are presented in the Part 1 of this theory and include the family composition (the family vehicle, ), the family health complexity (the vehicle’s working condition, ) and the service complexity (the road, ). No matter how straightforward or complex the family journey might be, the family vehicle is moved along the road via their attendance, participation and engagement in therapy services, represented metaphorically as the parent gears (). There are six parent gears including: logistics, knowledge, skills, feelings, relationship with the professional, and values and beliefs. Movement of these gears can be facilitated or inhibited by grease or grit concerning the child, parent, professional or organization with respect to: expectations, motivation, communication, resources, and timing (). When the gears are moving well or there is adequate grease to facilitate movement the family’s journey is smooth, characterized by good attendance, participation and engagement. However, if there is significant difficulty with at least one gear, or if the gear movement is limited by grit in the system, the family’s journey may be slowed or stalled, where parents may attend inconsistently or withdraw from service. Every gear has the potential to help families move through therapy or limit their movement, and the grease and grit also have the ability to facilitate or limit families’ attendance, participation and engagement. These elements of attendance, participation and engagement are explored in depth through the results.

Parent gears: how parents attend, participate and engage

Logistics

The most significant logistic hurdle for families was traveling to therapy sessions. This was extremely challenging for families that did not have a vehicle or a license, especially when they lacked money for the bus or taxi, or someone that could drive them to therapy. In some cases, families discussed these challenges with their service providers and were able to get volunteer drivers, or paid bus or taxi support. However, this support was not available for out-of-town appointments and some families were not comfortable discussing their needs with service providers. One young single mother (of two children who both used multiple services at the CTC) further explains that limited access to transportation ultimately ends in her canceling the session and providing an alternate reason to the agency:

Well yeah, I mean, if I didn’t have bus fare, I don’t drive, so if I don’t have bus fare I’m not going to be like yeah, I’m too poor to get there. I’m going to just be like I’m sick.

The child’s disability could also make travel challenging, with some behavioral or sensory needs limiting families’ ability to take the bus and children with physical needs experiencing pain in a car seat if the family did not have a wheelchair-accessible vehicle. All parents talked about the time needed to travel to and from appointments, with additional time needed for travel to work, school, childcare or additional health care appointments. It was exhausting for parents to consistently attended appointments with multiple disciplines and specialized services (e.g., Augmentative Communication Clinic) at the CTC and with other community partners. One mother in a dual parent household, stayed at home and had previous work experience in the health care system, attended all appointments with her son and reported:

It’d be racing from one appointment…it felt like ahhh, another appointment. But you know, I just did it because it was important for Joe. And then once I got there it was okay. It was just the actual physical commuting that would feel overwhelming sometimes and really tiring.

In families where parents worked full time, taking time off work to attend appointments was a significant barrier. In some cases, parents changed their job or quit their job in order to attend hospital or therapy appointments with their child as described by a father who was the only driver in their household:

Yeah, sometimes I used to miss my work…I used to work two weeks afternoon, two weeks morning. Then I quit that job because of my sons’ appointments. I don’t want to miss his appointments. It’s very important to us.

Parents ability to maintain employment while attending their child’s therapy appointments often depended on the flexibility of the employer and the service providers. For example, one participant, who is a teacher, squeezed her daughter’s therapy into her ‘planning time’ with family and friends driving the child to and from appointments. In a family where both parents participated in therapy and the study, they described negotiating their workplace meetings so that they didn’t conflict with their son’s therapy schedule. A father of a child with Cerebral Palsy explained that he used his sick days and family illness days, combined with flexible scheduling by his therapist in order to continue working while attending his daughter’s appointments:

We are really lucky that our therapists have been flexible in times. I think too, they are a little sensitive of the fact that we spent so much time in hospitals… we spend so much time at (Hospital Name) and in other areas just in follow-up appointments and appointments throughout the day that this is really hurting our um… sick days, our family illness days, to the point where we are not getting paid some days to do these things, right, and that’s frustrating.

In addition to missing work, parents were also frustrated by having to pull children out of school or daycare to attend appointments. When there was more than one child in the home, parents often had challenges finding childcare while they were in hospital or attending therapy appointments.

Parent knowledge

The parents’ knowledge that affected their attendance, participation and engagement in their child’s therapy was broken into three main areas: general knowledge of child development, knowledge specific to their child’s disability, and knowledge regarding services. Parents gained knowledge of child development from their experiences raising other children, and from their educational or work experiences. For example, several participants were teachers, one was a therapist who worked with children with Autism and two studied to be special education resource-consultants. These parents used their knowledge to identify their child’s difficulty, set goals, develop practice ideas, and access services. Parents were least confident in their knowledge when this was their first child, or if their other children had not used services and they had no prior educational or vocational experiences with children’s therapy. They generally did not know what to expect from services and were appreciative of the information given to them by therapists, for example one young mother who shared custody of her child stated:

They were pretty good with giving information. Like I didn’t really know what to ask ’cause I’ve never really been through this kind of thing before. My other son was really, really good with his speech so I didn’t … I have no idea, but like they were just really, really good at giving the information I needed.

Parents often talked about learning alongside their children and developing knowledge that was specific to their child’s needs, for example learning how to fix a wheel chair, interpret non-verbal communication or reading about neuroplasticity. This knowledge allowed parents to understand their children and to help them at home. Parents reported positive experiences of therapy when they viewed services as a means for them to learn how to support their child, as described by a father who shared custody of his daughter who uses multiple services at the CTC:

It can be a nuisance having to go into appointments and stuff and everybody agrees but it’s like I feel good because I can go and I can learn. So, I’m basically on the same path that she’s taking, so I mean, for me as a parent it’s a learning curve. I got to learn with her, right? So what she is learning, I’m learning and then I can use that to help her at home, right?

Parents were most confident in their knowledge when they had other children who had been through developmental rehabilitation services. This helped parents to identify developmental issues sooner, know what services were available and how to access them, and know how to help their child. One mother had many insights to share from her experiences raising three children who have a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder:

I’m just going to say that you have to be a squeaky wheel and you got to know the system… not the system, you have to know the facility, you have to know the needs of your child and you have to fight… being educated helped me and they all get services.

Parent skills

There are two main therapy related skill sets that parents developed throughout the family’s journey through services. The first skill set is case management for their child and the second is therapeutic skills. Case management skills often related to scheduling appointments and included: timing/spacing appointments, remembering appointments, coordinating appointments, being organized and multi-tasking. This became more difficult for families when there were multiple children at home who used therapy services and had many organizations and professionals involved as illustrated by this single mother who did not drive and was raising two children who used multiple services at the CTC:

I’m pretty organized with staggering appointments. Mason has always had like … when he was Liam’s age he had six, seven appointments a week so we were, you know, like I learned how to make sure that I had enough travel time and stuff like that and making an appointment with somebody on the phone for me takes like five minutes because I’m like actually no, we have to move it here and well what about your day and … so like, you know, I’m a stay at home mom but I gotta schedule like them. So it’s really hard to collaborate sometimes but we … I always fit it in where it’s possible, right?

Parents often identified doing therapy practice at home as one of the main ways that they participated and were engaged in their child’s therapy service. In order to carry out therapy at home most parents watched the therapist during their child’s session so that they could copy them, learn about the child’s goals and what to focus on, and pick up structured or unstructured practice ideas from the therapist. Sometimes parents attended groups in which they were taught specific skills they could use to help their child. As parents of preschool aged children, participants often identified the skills they developed to work therapy into their everyday life and make it fun for their child. Several parents noted that once they had developed the skills they needed to help their child, they no longer felt the need to attend therapy. For example, a mother who’d attended speech therapy with her child who had a mild speech sound disorder talks about being empowered through knowledge “Once I had the information I needed to know how to teach those specific skills that he needed, I was empowered and able to do that on my own.”

Parent feelings

Parents expressed intense feelings that served to promote or limit their attendance, participation or engagement in therapy. Initially, parents often felt worried and anxious about their child’s survival, development, and happiness. This was especially true for children who underwent extensive diagnostic testing or had life-threatening conditions. Parents’ worries were often related to the child’s future, for example school entry and the potential for their children to experience bullying or fall behind academically. Mothers in particular often worried and felt guilty that they were not doing enough to help their children. This guilt could be externally driven by family or care providers when parents felt blamed or judged for their child’s difficulties, their parenting decisions, or the amount they were doing to help their child. Often mothers who were very engaged in their child’s therapy spoke about self driven guilt, vividly illustrated below as the tension between wanting to do more and being exhausted as expressed by one mother who had previous work experience with children with disabilities.

And as parents, particularly moms, you know, are for the most part naturally inclined to feel that sense of guilt all the time. Are we doing enough? But then when you have that background information too, you know, it’s I find for me it …I’m constantly feeling like I’m not doing enough and … but then I’m so tired. So it’s almost like a paradox because there is a sense of not doing enough but then also this I’m so tired, I don’t really want to do anything.

In comparison, the fathers who participated in this study felt compelled to ‘be strong’ and support their children and partner, especially when their partner was experiencing mental health difficulties as shown below. Although typically seen as ‘negative feelings’ parents described worry, guilt and the need to be strong as feelings that increased their attendance, participation and engagement in their child’s therapy service.

I have to be strong, you know, like uh … (my wife) was always crying then I used to say it’s okay, God give us and we have to take care of him. We have to be strong. If we’re… if we be like sick who is going to take care of … you know, crying and worrying doesn’t help you, we have to be strong especially for your son.

There were also positive feelings that parents associated with therapy. Parents felt relieved to get information that would help them to understand and support their children. They were proud, excited and hopeful when they saw their child grasp a new skill in therapy or at home. Parents often spoke about how they felt when leaving a therapy session, which included positive descriptions of relief and feeling “buoyed up”. Service providers contributed to parents’ positive feelings during therapy when they recognized the efforts that parents make to help their children and pointed out the child’s improvements. The perspectives of a mother and clinician are captured below:

And she does it and then they are like, you did, that’s so great. I’m proud of you. You know, like that kind of thing makes a difference to how she feels when she is there and how I feel… That’s pretty amazing…I do really like that part.

(A mother of a child with complex needs who used multiple CTC services)

I loved the fact that (parents) could say ‘yeah, I am seeing progress’ because sometimes when you’re in this vacuum of all this stuff coming at you sometimes all (parents) see is the negative and I think they miss key moments to celebrate.

(A clinician who had over 10 years of experience at the CTC)

Parents also expressed strong negative feelings associated with therapy that led to decreased attendance, participation and engagement. Some parents experienced “anger, upset, disillusionment and disengagement” when leaving a therapy session, especially if their expectations were not met or they disagreed with the service providers’ approach or information. Anger, upset and fear were also elicited when parents were involved with a child protective agency, which occurred for 5 of the 18 families who participated. Parents often associated therapy with feeling frustrated and overwhelmed, which coincided with exhaustion, stress and depression and could lead to decreased engagement as recounted here:

Um, sometimes I used to just lock the door and not let [the rehabilitation service providers] in and I would just go and lay in bed with Sadie all day. But, now I feel like they hear me more and that they understand that she’s my kid ’cause the other ones used to just be like oh, this is how you do it and you are going to do it like this, this and this, then I want you to do it for ten hours and then the next therapist would be like the same thing and there’s not that many hours in the day so I could never do it all. And I felt like I was failing her, but she is progressing now and I don’t feel like a failure anymore.

Parent professional relationship

The relationship between the parent and the therapist was identified as a critical component of engagement. Their relationship can be described according to the connection between the parent and the service provider, their level of agreement and how much the parent trusts the service provider. The connection refers to the personal aspects of the relationship and parents who have a strong connection often referred to their service provider as a “friend”, “buddy” or “extended family”. In these cases, the parents felt like the service provider knew them and their child well. Often these service providers paid personal attention to the family, for example by staying to have coffee. Here, three parents describe positive connections with service providers in various environments, these are contrasted with a parent’s negative relationship with a services provider:

[Hospital nurses] were like extended family…extremely supportive, helpful, anything I had, any questions, any of my worries…they made it all better.

(Mother’s reflection on the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit nurses)

Yeah, [child protection services worker] comes in here, kicks her feet up on my couch and has coffee with me, like she is … like she is a worker and I mean she would never let me get away with anything bad but I consider her a buddy. Like, she comes and chats with me and like she is an inexpressible like support system.

(Mother’s reflection on involvement with child protection agency worker)

I really love going to the physio and the occupational therapy and the speech sessions. So all of those ones I look forward to going to partially because they are kind of fun and I love like the therapists so much that they are like friends now.

(Mother’s reflection on service providers at the CTC)

I just find that that particular individual treats us like a number and doesn’t look out for our best interests. And that persists today, she is still our case worker. I just don’t call. I’ll go every other means before calling this woman.

(Mother’s reflection on Autism case worker)

When parents experience the personal connection with the service provider they often describe trusting that person. Sometimes it takes time for that trust to develop and may be dependent on child progress. When parents do not trust the service provider they may discontinue a service or change service providers. It was also important that parents felt that the service provider trusted and believed the information they shared about their child. When there is a positive connection and trusting relationship between parents and professionals, they tended to reach agreement about the child’s skills, needs, and how to move forward, often described by parents as “being on the same page” as illustrated by a mother, “You kind of want your therapist to, you know, remember you and know you and be on the same page as you about your child’s need or your family need” and a father, “Our physio…we’re on the same page when it comes to…just trying whatever, just pushing, going forward and not setting limitations.” Progression through therapy was disrupted when parents and service providers did not reach agreement about the child’s skills or an approach to therapy, as was the situation for this parent, “I think I would tune out because I thought that her advice did not apply to us. And I didn’t think she was gauging Sally’s real level of skills appropriately”. The three parents quoted in this section had expertise in children’s learning, with training as teachers or health care professionals. They did extensive independent learning about their child’s needs and approaches to therapy and were strongly influenced by their therapists’ agreement with their own knowledge.

Parents’ values and beliefs

Parents often identified their values and beliefs as the most important gear affecting their engagement in their child’s therapy because these (values) underlie everything else:

I’d have to say values because that’s the root of it all, right? That’s the fire that ignites me into going. If I didn’t believe it I wouldn’t do it, right? And go through all of the logistics and all those things, so I’m going to have to say my values… my values and how much I value the effectiveness and the practice of going to therapy, how important it is for his development.

(Mother in a dual parent family who stayed at home to care for two children who each had a diagnosis and a need for service).

Engagement was promoted when parents valued inclusion, independence, education, and therapy. The beliefs that led to attendance, participation and engagement include: the belief that it is a parent’s responsibility to help their child to reach their full potential, that we should be optimistic about what children can achieve, and that children will improve with consistent practice and this takes time.

The factors that affect parent attendance, participation and engagement: grease and grit

Five factors affect movement of the parent gears; these are viewed as grease that promotes gear movement or grit that inhibits gear movement (). The grease and grit exist at the child, parent, therapist and organizational levels. The five factors include: motivation, communication, expectations, timing, and resources, and each will be presented with the most compelling examples of how they can affect parent gear movement.

Motivation

Motivation is closely aligned with the parent feelings gear described above. Initially parents are motivated by their worry about their child experiencing hardships and hope for their child’s future. However, they are strongly influenced throughout their therapy journey by the child’s motivation and progress. When children resist practice, or are unhappy during therapy, it is challenging for parents to stay motivated. But when children enjoy going to therapy and have a good relationship with the service provider parents report that therapy can be fun and highly motivating. In particular, parents are motivated when their service provider appears to be committed, genuinely excited and concerned about the child, prepared and willing to try new things. When children make improvements, it increases parents’ motivation until a point where parents report backing off because they feel the child is doing well and catching up, as noted by this mother whose child had a speech sound disorder “I’d say (my motivation) it’s getting lower because he is getting better but when he was struggling the most it was pretty high.” In situations where the parent does not feel like the therapy is effective they may lose all motivation and stop attending:

I attended mostly however I have to admit that I would call in sick when Sally was not sick. It’s just that I was so angry with the level of service that I couldn’t sometimes deal with it because it was depressing ’cause at times I felt like I was being blamed. So I have the skillset to attend but I didn’t like what was happening in the um… sessions. And the quality of speech language pathology was really, really bad.

Expectations

The therapy related expectations held by parents, children, clinicians and organizations were an important influence on attendance and engagement. Parents reported higher engagement when there was alignment between what they thought the service would provide and what was delivered. Parent expectations were closely related to the knowledge gear, with parents’ understanding of services increasing through service use. This mother who used services for the first time for her child with a speech sound disorder observed:

There’s no magic to making it happen, right? It’s just work. When we first went you know I kind of and in fact I know other parents, you just kind of think you just go and they’re going to fix your kid, right? Like that’s what I had in my head. We’re going to go to a few things and they’re going to fix it and we’re going to be good. You get there and you’re like oh it’s daily homework this isn’t this isn’t fixed overnight.

Service providers and organizations had expectations of parents regarding attendance, participation during sessions, and the work parents would do at home to support their child. Attendance expectations were often expressed through organizational policies and 16/18 children’s treatment centers in Ontario had a policy or procedure whereby families are discharged if they miss a pre-specified number of appointments without prior notice. At the recruitment site service providers were inconsistent in enforcing these organizational policies, however they consistently shared expectations regarding the work parents could do at home to support their child. One parent who was involved with multiple services and organizations was frustrated by the number of expectations placed on her and the service provider’s judgement:

Yeah and then we had other people for OT and Speech and they got us to do the Nuk Brush and oh you got to do it like seven times a day, for this long but then PT wants you to do this for this many times a day for this long and this person wants you to do this for this many times and for this long…And then they’d show up and be like oh well I can tell you haven’t been doing it for this much. Well how am I supposed to do this and this and this and this.

Service providers often felt overwhelmed with organizational expectations regarding number of clients to be seen, amount of time spent on client work versus non-client related work (e.g., meetings), and direct client work vs indirect client work (e.g., documentation). The tensions between organizational expectations of service providers and their own expectations of themselves arose frequently, for example, a clinician stated “you are working really hard at capacity all the time to meet those standards and I’m a person not a machine” and another clinician commented “I think in a place like this, quota shouldn’t be as important as quality of care for the children, right?” Administrative expectations about having calendars booked with clients in advance meant that service providers had limited flexibly with scheduling clients, causing tension when service providers and their clients expected timely responses to address client needs as expressed by the clinician quote below:

We are working with families not just with little kids whose own little crazy schedules are all over the place and things happen, but because these are kids with disabilities and special needs. So, like their family lives are not following nice schedules, I mean, their whole lives are around meeting their kid’s needs. So yeah, like if we can’t accommodate to that like who else in the system does?

Resources

Parents’ resources, their willingness to use their available resources, or their lack of resources are critical in determining how the gears function, especially in conditions that are likely to challenge gear movement, such as single parent families with multiple children or families who are using many different services. Resources are only described briefly here due to space constraints, but can be grouped in the following types: people, faith, services or funding, information, and organizational support. Participants described varied levels of support from their partner, parents, and friends. Supportive partners helped with the skills gear by helping to keep track of appointments and the logistics gear by watching siblings or driving to appointments. Grandparents helped with the knowledge gear especially for young parents who relied on grandparents for general childhood and medical advice; they also helped with the logistics gear by paying for devices or private therapy, helping with travel and attending appointments with the child. Notably partners and grandparents negatively impacted the feelings gear when they blamed the parent for the child’s difficulties. Faith groups and a belief in God helped some parents to find the emotional strength they needed to participate and stay engaged in therapy.

Tangible support described by parents included funding for services such as respite, home cleaning, or childcare. Resources that families used were not always specific to the child’s disability, such as mental health counseling services for parents, drug addiction programs, and income support programs. Informational resources that parents accessed included web-based searches, diagnostic-specific online or in person support groups, and library books. These resources could impact the parents’ skills, knowledge or feelings gears. The logistics gear was most impacted by organizational support, including:

travel support such as volunteer drivers, paid bus tickets or taxi support

therapy services provided at home or daycare

services provided outside of traditional working hours for families that work full time

offering joint appointments with more than one discipline present or limiting the number of disciplines directly involved to decrease the overall number of appointments for a family.

These resources, offered by the organization, could make the difference between a family who was able to use services and one that was not.

Timing

Families often pointed out that therapy happens in the context of their lives, and some phases of life are more conducive to therapy than others. One single parent who disclosed mental health issues spoke about these ‘phases’ as days in her life that affected her motivation:

Like I have my own issues in life so…I’m going through my own things depending on, like I said, it depends on the day. Everybody is either highly motivated some days or you know, they could be least motivated on really bad days, right? If they have to deal with their own personal life, so unfortunately that affects those around you and what you are supposed to be doing in day to day life, right?

Other parents spoke about specific phases in life marked by significant events. A father, who became a parent as a teenager, spoke about his challenges related to moving out of his parents’ home, getting engaged, learning to live independently and raise a child with significant medical needs, all at the same time. Another parent talked about overcoming drug addiction and now that her children are old enough for childcare, she is finishing her high school diploma and feeling optimistic about her life. Normative life events, such as having another child could increase engagement when mothers were home on maternity leave and had more time for attending appointments or decrease therapy engagement if mothers were tired by a pregnancy. Parents also faced significant legal battles, changed jobs, moved across cities or provinces, got divorced, and got married. These periods of major change taxed families’ time and emotional resources, leaving limited capacity for engagement in therapy.

Communication

Parents and service providers both identified communication as one of the most important factors in determining whether a parent would be engaged in therapy or not. Parents needed to feel that service providers were listening to them, were understanding, and that they valued parents’ input. The need for listening and empathetic responses were highlighted by the parent and clinician quoted here:

CTC (name) is more understanding and they listen when I talk, as the other places they just wanted it their way. And um, it was right after we got out of the hospital so then I was worried about (the child protective agency) cause like they were involved my whole life and my sister was taken away for foster care for a little bit. So um, yeah I didn’t want that in my kids’ life.

(A young mother whose child had high health complexity)

They don’t need to hear that everything is going to be okay and they don’t want to hear just wait. They want to hear, no your concerns are valid, we are seeing this stuff, but we are here with you and we are going to support you and we are going to journey this with you.

(A clinician in a leadership position at the CTC)

When these safe and supportive communicative relationships were developed, parents were willing to share information, ask questions, and raise concerns. When parents felt that service providers were dismissive or unresponsive they were unlikely to share their ideas or challenges. The way in which service providers shared information with parents critically affected the skills, feeling, and knowledge gears. Parents reported that they understood the information and were confident about knowing what to do if service providers broke things down, took time to answer questions, and avoided use of jargon. However, care providers should be aware of whether they are condescending in their attempts to share information with families as this was received negatively by parents, for example a young parent said “well I like it when the Doctors talk to you like you’re stupid because like yes, it’s a new thing and it’s scary but like the way they talk to you is like oh they are better than you.”

It was helpful for parents when service providers communicated with one another and avoided giving parents conflicting information. Communication was further supported when therapists wrote things down, gave websites or pamphlets for additional information, and made dual sets of information for divorced parents. For parents who spoke English as a second language, having written information allowed them to share it with friends or family members who could help to translate and promote understanding.

Parent priorities: Destination child health and happiness

Every parent who participated in the study wanted their child to be happy and healthy, a sentiment that resonated with me (lead author) as a parent and with my peer debriefing groups. Often parents know that their child has a delay in one or more areas of development and when the child has a diagnosis it will be with them for life (e.g., Autism Spectrum Disorder or Cerebral Palsy); therefore, their main concern was whether their child would be healthy and happy. Families described health in terms of survival, limiting pain and illness, and promoting physical growth. In times when health was limited or survival was threatened, everything else was put aside including parents’ self care, care for other children, and involvement in other therapy services. Happiness was attributed to the enjoyment of therapy and practice activities and the attainment of skills that would allow children to play, interact with others, and experience inclusion and independence. Parents shared many examples of skills that they worked on in order to promote their child’s happiness, for example by being able to climb structures at the park, join the family at skating, or make friends in school. One father summarizes nicely by saying “Is she going to live a happy life or not?…I know she is going to be delayed…I want to know if she is going to live… if she is going to live a happy and full life, I’m happy”.

Discussion

The Phoenix Theory of Parent Attendance, Participation and Engagement includes: the conditions that can make it easier or more challenging for families to attend, participate and engage in children’s rehabilitation services (), the six parent gears that function together to move families towards child health and happiness via attendance, participation and engagement (), and the factors that can positively or negatively affect this journey (). This theory is inductively derived using grounded theory methods and the components of the theory and their relationship to one another would benefit from quantitative testing.

Although this is a novel holistic conceptualization of parent engagement that is specific to parents’ experiences of children’s developmental rehabilitation services, not all components of the theory are new. The logistic barriers to use of children’s public health, social, and educational services use are well described in a systematic review [Citation9]. The parents’ knowledge, skills, and feelings presented here align well with the conceptualization of parent engagement within a therapy session as developed by King, Currie, and Petersen [Citation8] using mental health literature. These authors also identify parent beliefs, motivation and trust as factors that impact engagement. The fact that these engagement factors were inductively derived from the parent interview data in the present study suggests that there are similarities between the children’s mental health environment and that of children’s developmental rehabilitation services, and that in-session engagement and out-of-session engagement have similar components for parents. The theory of attendance, participation and engagement presented here aligns well with Bright’s conceptual definition of engagement in healthcare, that suggests engagement is both a state and a process that is constructed by the patient and health care provider [Citation6].

The parent-professional relationship has been studied more than any other ‘gear’, including bodies of work on the therapeutic relationship [Citation32,Citation33], collaborative goal setting [Citation17,Citation34], and negotiated roles [Citation13,Citation35]. In addition to negotiating roles with parents, service providers should discuss their expectations of parents, and parents’ expectations of therapy, given that this can lead to improved client outcome and satisfaction [Citation35,Citation36]. Parents in the study presented here echoed the experiences of other parents who used pediatric occupational therapy [Citation37] and speech therapy services [Citation38,Citation39]; where early expectations for a specific type of therapy or a ‘fix’ were adjusted given child progress, parent satisfaction and experience with the service. Organizational expectations of parent attendance and participation as indicated through CTC policies and procedures have received minimal attention in the literature. Parent values and beliefs are also rarely studied; however, authors have described the potential discrepancy between child, parent, therapist and researcher values and assumptions that can impact goal-setting and outcome measurement [Citation17,Citation40] and the field of rehabilitation [Citation41,Citation42]. This is an area that deserves further attention, given that parents often place their values and beliefs at the heart of their engagement in services.

It will be difficult for clinicians and researchers to join families as they move through therapy services if they have their eyes trained on different destinations. Families consistently identified child health and happiness as their desired destination and their reason for participating and being engaged in therapy services. While medical services that follow a traditional medical model of ‘assess, diagnose, treat, recover’ may be appropriate to treat the child’s health concerns, happiness cannot be ‘treated’ in a similar manner. The revised International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) shifts thinking from a biomedical model to a biopsychosocial model, that includes consideration of the body functions and structure, activity, participation, the environmental and personal factors [Citation43]. Application of this model in research and practice encourages a focus on the family, functional use of skills and the child’s participation in real world contexts [Citation44,Citation45]. Definition and measurement of the family environment in pediatric rehabilitation [Citation46] and the personal factors component of the ICF has been a challenge [Citation47]. Given that parents reported that their child’s happiness is a driving force behind their engagement, it is necessary for service providers and researchers to consider the home environment, personal factors, and what would be “fun” [Citation48] when offering therapy to families. Children’s perspectives on attendance, participation and engagement in therapy were not directly elicited in this study. Given that parents described the motivation of their children as either grease or grit that impacted their engagement, direct study of children’s perspectives is recommended. Imms and coauthors [Citation49] deeply explored the participation of children with disabilities and the complex multidimensional and transactional relationships between participation, attendance and engagement. The delineation of these related, yet distinct, constructs in a therapy context continues to challenge researchers and service providers who seek to study and promote parents’ attendance, participation and engagement in children’s therapy. The Phoenix Theory of Attendance, Participation and Engagement offers service providers, researchers and policy makers with a conceptual means of understanding how parents attend, participate and engage in children’s rehabilitation services and the ways in which we can facilitate these aspects of intervention.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the inclusion of participants who would traditionally be seen as ‘hard-to-reach’ due to multiple missed appointments and parents who consistently attend their appointment. These participants provided diverse perspectives that allowed for a comprehensive understanding of properties and dimensions of the major categories that comprise parents’ engagement in their child’s therapy services.

A limitation of this work is that all parents were recruited from a single developmental rehabilitation organization. Therefore, the transferability of this theory may be limited for other groups traditionally viewed as hard-to-reach (e.g., Indigenous families in Canada) or those accessing other models of care (e.g., school-based services).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the parents and clinicians that participated in this research study. We are appreciative of the transcription services of Caroline Phelan and the data management done by Tessa Dickison.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kuhlthau KA, Bloom S, Van Cleave J, et al. Evidence for family-centered care for children with special health care needs: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11:136–143.

- Rosenbaum P, King S, Law M, et al. Family-centred service: a conceptual framework and research review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 1998;86:1–20.

- Siebes RC, Wijnroks L, Ketelaar M, et al. Parent participation in paediatric rehabilitation treatment centres in the Netherlands: a parents' viewpoint. Child Care Health Dev. 2007;33:196–205.

- Arai L, Stapley S, Roberts H. 'Did not attends' in children 0-10: a scoping review. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40:797–805.

- Littell J, Alexander L, Reynolds W. Client participation: central and underinvestigated elements of intervention. Soc Serv Rev. 2001;75:1–28.

- Bright FAS, Kayes NM, Worrall L, et al. A conceptual review of engagement in healthcare and rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:643–654.

- D'Arrigo R, Ziviani J, Poulsen AA, et al. Child and parent engagement in therapy: what is the key? Aust Occup Ther J. 2017;64(4):340–343.

- King G, Currie M, Petersen P. Child and parent engagement in the mental health intervention process: a motivational framework. Child and Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2014;19:2–8.

- Boag-Munroe G, Evangelou M. From hard to reach to how to reach: a systematic review of the literature on hard-to-reach families. Res Pap Ed. 2012;27:209–239.

- Phoenix M, Rosenbaum P. Development and implementation of a paediatric rehabilitation care path for hard-to-reach families: a case report. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41:494–499.

- Winkworth G, McArthur M, Layton M, et al. Opportunities lost––why some parents of young children are not well-connected to the service systems designed to assist them. Aust Soc Work. 2010;63:431–444.

- King G, Servais M, Shepherd TA, et al. A listening skill educational intervention for pediatric rehabilitation clinicians: a mixed-methods pilot study. Dev Neurorehabil. 2017;20(1):40-52.

- Hurtubise K, Carpenter C. Parents' experiences in role negotiation within an infant services program. Infants Young Child. 2011;24:75–86.

- Øien I, Fallang B, Østensjø S. Goal-setting in paediatric rehabilitation: perceptions of parents and professional. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:558–565.

- Wiart L, Ray L, Darrah J, et al. Parents' perspectives on occupational therapy and physical therapy goals for children with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:248–258.

- King G, Currie M, Bartlett DJ, et al. The development of expertise in pediatric rehabilitation therapists: changes in approach, self-knowledge, and use of enabling and customizing strategies. Dev Neurorehabil. 2007;10:223–240.

- Forsingdal S, St John W, Miller V, et al. Goal setting with mothers in child development services. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40:587–596.

- Staudt M. Treatment engagement with caregivers of at-risk children: gaps in research and conceptualization. J Child Fam Stud. 2007;16:183–196.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2006.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014.

- Higginbottom G, Lauridsen EI. The roots and development of constructivist grounded theory. Nurse Res. 2014;21:8–13.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Dir Eval. 1986;30:73–84.

- Gentles SJ, Jack SM, Nicholas DB, et al. Critical approach to reflexivity in grounded theory. Qual Rep. 2014;19:1–14.

- Breckenridge J, Jones D. Demystifying theoretical sampling in grounded theory. Grounded Theory Rev. 2009;8. http://groundedtheoryreview.com/2009/06/30/847/

- Gentles SJ, Charles C, Ploeg J, et al. Sampling in qualitative research: insights from an overview of the methods literature sampling. Qual Rep. 2015;20:1772–1789.

- Boeije H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual Quant. 2002;36:391–409.

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1758–1772.

- Glaser BG, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967.

- Birks M, Chapman Y, Francis K. Memoing in qualitative research: probing data and processes. J Res Nurs. 2008;13:68–75.

- Timmermans S, Tavory I. Theory construction in qualitative research: from grounded theory to abductive analysis. Soc Theory. 2012;30:167–186.

- Farmer T, Robinson K, Elliott SJ, et al. Developing and implementing a triangulation protocol for qualitative health research. Qual Health Res. 2006;16:377–394.

- King G. A relational goal-oriented model of optimal service delivery to children and families. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2009;29:384–408.

- King G. The role of the therapist in therapeutic change: how knowledge from mental health can inform pediatric rehabilitation. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2017;37(2):121-138.

- Brewer K, Pollock N, Wright FV. Addressing the challenges of collaborative goal setting with children and their families. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2014;34:138–152.

- Hessell S. ‘Entering the unknown? ’ Identifying potential expectations of paediatric occupational therapy held by families. New Zealand J Occup Ther. 2004;51:5–11.

- Coyne I. Families and health-care professionals' perspectives and expectations of family-centred care: Hidden expectations and unclear roles. Health Expect. 2015;18:796–808.

- Andrews F, Griffiths N, Harrison L, et al. Expectations of parents on low incomes and therapists who work with parents on low incomes of the first therapy session. Aust Occup Ther J. 2013;60:436–444.

- Carroll C. "It's not everyday that parents get a chance to talk like this": exploring parents' perceptions and expectations of speech-language pathology services for children with intellectual disability. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2010;12:352–361.

- Lyons R, O'Malley MP, O'Connor P, et al. 'It's just so lovely to hear him talking': exploring the early-intervention expectations and experiences of parents. Child Lang Teach Ther. 2010;26:61–76.

- Gibson BE, Teachman G, Wright V, et al. Children's and parents' beliefs regarding the value of walking: rehabilitation implications for children with cerebral palsy. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38:61–69.

- Gibson BE, Darrah J, Cameron D, et al. Revisiting therapy assumptions in children's rehabilitation: clinical and research implications. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:1446–1453.

- Gibson BE. Rehabilitation: a post-critical approach. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016.

- World Health Organization. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

- Cunningham BJ, Washington KN, Binns A, et al. Current methods of evaluating speech-language outcomes for preschoolers with communication disorders: a scoping review using the icf-cy. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2017;60:447–464.

- Darrah J. Using the ICF as a framework for clinical decision making in pediatric physical therapy. Adv Physiother. 2008;10:146–151.

- Ketelaar M, Bogossian A, Saini M, et al. Assessment of the family environment in pediatric neurodisability: a state-of-the-art review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59(3):259-269.

- Geyh S, Peter C, Müller R, et al. The personal factors of the international classification of functioning, disability and health in the literature - a systematic review and content analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1089–1102.

- Rosenbaum P, Gorter JW. The 'f-words' in childhood disability: i swear this is how we should think!. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38:457–463.

- Imms C, Granlund M, Rosenbaum P, et al. Participation, both a means and an end: a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:16–25.