Abstract

Purpose: To investigate outdoor mobility of immigrants in Sweden who are living with the late effects of polio.

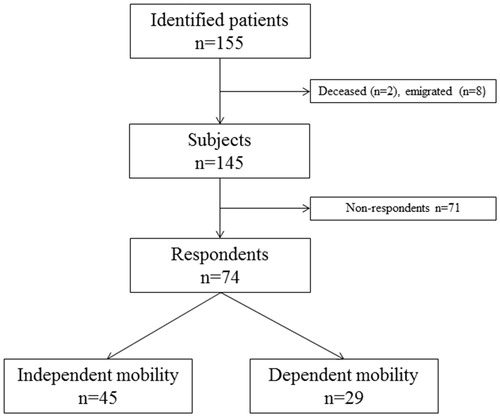

Materials and methods: A total of 145 patients with late effects of polio born outside the Nordic region were identified at an outpatient polio clinic. Of these, 74 completed a questionnaire about their mobility and independence in daily life, self-perceived pain and depression, vocational status, mobility assistive devices/aids, transportation modes and driving. Patient characteristics were based on medical records supplied by physicians.

Results: Twice as many patients had lower extremities that were affected by polio than upper extremities. This affected their use of different transport modes and caused mobility and transfer problems. Indeed, 39% needed mobility aids and help from another person to move outdoors. Those who reported dependence for outdoor mobility were more often unemployed and more often depressed.

Conclusions: Many respondents reported having difficulties with transport mobility, but a large proportion, 57%, were independent and active drivers. It is important to consider outdoor mobility when planning rehabilitation for patients with late effects of polio and foreign backgrounds. In addition to psychosocial factors, dependence on mobility-related activities can lead to dependency and isolation.

Outdoor mobility and access to transport modes are important for independence and an active life and need to be included in the rehabilitation process.

Both personal and environmental factors, can contribute to mobility problems of people with foreign backgrounds, who are living with the late effects of polio.

Factors such as cultural, social and gender aspects are important when planning suitable and individualized rehabilitation.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Although acute poliomyelitis is very rare in industrialized countries [Citation1], 12 to 20 million people globally live with the sequelae of polio [Citation2]. New symptoms may emerge several years after recovery from polio, including new muscle weakness, fatigue, pain and functional loss [Citation3]. Many people who suffer from the late effects of polio have impaired walking ability due to reduced balance, muscle strength and pain, which impacts their daily life [Citation4]. Mobility is of major importance for health, autonomy and well-being [Citation5], and many different lifestyles and living patterns require transportation and mobility [Citation6–8]. Being able to move independently from one place to another is essential for quality of life and for participation in many activities [Citation6–9]. Polio survivors often have impaired muscle function that can result in mobility problems [Citation10]. Community mobility may include walking, using mobility devices, using public transportation like buses or trains, using private transportation such as a ride from a friend or family member and driving a car [Citation11]. A goal in the transport policy in Sweden is that the use of public transportation should be improved by increased safety, reliability and also usability for people with disabilities. Although, the public transportation system is well developed it is not always accessible for all (such as high step to enter the bus/tram) and with a sparse network and low frequencies in the country side. Therefore, Special Transport Service (Taxi) are available but also other types of mobility devices that are subsidized.

Independent mobility, i.e., having access to transportation, is critical for ensuring access to employment and education [Citation12]. According to the ICF (the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health), the term disability can be used to explain the relationship between a specific health condition and factors such as environmental and personal factors [Citation13]. The term ‘environmental factors’ refers to the physical, social and attitudinal environment in which people live. Moreover, mobility is defined as “…moving by changing body position or location or by transferring from one place to another…by walking…and by using various forms of transportation” [Citation13]. According to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, States Parties should ensure that people with disabilities have access to transportation, on an equal basis with others, in both urban and rural areas. However, some rural and suburban areas have fewer transportation resources, and people with physical impairments may have difficulty walking to a bus stop and/or have limited access to other alternative transportation modes [Citation11]. Physical barriers can have a negative impact on independence and on the participation of people in activities outside their home [Citation14]. However, there are often several factors, including personal and environmental factors, that contribute to mobility problems [Citation7].

In Sweden, polio vaccination began in the late 1950’s, so polio survivors who are native to Sweden are often over 65 years old. However, the number of young polio survivors (working age) in Sweden has increased as a result of immigration and adoption [Citation15]. Swedish society has become multicultural, and the number of younger immigrants who are polio survivors is increasing at outpatient clinics [Citation16], especially the number of immigrants from Africa and Asia [Citation17]. In their home countries, many of these individuals did not receive optimal health care during the acute stage of polio, and when they contact the polio clinic, many have contractures, malformations and no or few mobility devices. Moreover, their new symptoms affect their daily life, and there may be factors other than physical impairments that affect their perceived quality of life [Citation18]. The health care system in Sweden faces new challenges when treating these individuals. In addition to medical aid and help with their functional status, many patients experience limitations in everyday activities and need psychosocial and vocational rehabilitation interventions [Citation19,Citation20].

A limited number of studies have focused on mobility transportation and driving for people with physical impairments [Citation21], especially for people with polio. It is particularly important to understand how the late effects of polio affect patients in their daily lives [Citation20,Citation22] in order to provide assistance and treatment for the mobility problems and to help give patients access to safe transport and independent mobility in their communities. This study investigated the outdoor mobility of immigrants in Sweden who are living with the late effects of polio.

Methods

Patient characteristics and questionnaire

In this cross-sectional study, data were retrieved from a database (based on personal identity numbers) at the Polio Clinic [Citation17] at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg, Sweden with first visit between 1994 and 2015. The inclusion criteria for the study were age 18 to 50 years at their first visit at the Polio Clinic and born outside the Nordic countries, with a diagnosis of the late effects of polio (Nordic polio survivors are over 65 years old). The patient characteristics, National Rehabilitation Hospital (NRH) polio classification [Citation23] and electromyography (EMG) data were registered by the physicians at the polio clinic. A questionnaire was mailed to potential participants with questions about mobility and independence in daily life, self-perceived pain and depression, vocational status, mobility assistive devices, transportation modes (car, bus, tram, train and ferry), driving license and driving status. For example, questions regarding mode of transport were assessed with the following multiple-choice questions; Do you perceive any barriers when traveling by train/tram/bus/ferry/car? The response levels were as follows: difficult to transfer to and from (transport mode, e.g., from house to bus stop)/difficult to get on and off (in and out)/difficult to use train or ferry facility/orientation problems/difficulties with booking and payment/fear. The questionnaire (Swedish) took approximately 20–30 min to complete. This questionnaire was based on a questionnaire that was used previously with patients with stroke [Citation24] and traumatic brain injury [Citation25] in Sweden. For this study, it was adapted for people with late effects of polio. After approximately two weeks, a reminder letter was sent to those who had not returned the questionnaire. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg. All respondents provided written informed consent. This study followed STROBE guidelines for observational studies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS Statistics, version 22. A p values < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all tests were two-tailed. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation [SD], min/max) were used for the patient characteristics. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables and Pearson Chi-Square test for dichotomous variables.

Results

A total of 155 patients met the inclusion criteria; of these, 2 were deceased, and 8 had emigrated. Thus, a total of 145 (84 men) were considered for the study ().

A total of 74 questionnaires were returned (51%). The average age of the participants who returned the questionnaire (36 women, 38 men) was 47.8 years (SD 9.9, range 23–70). The age at polio onset ranged from 0 years to 10 years (average age 2.0 years), and there was no significant difference in sex distribution or age between the respondents and the non-respondents. The respondents were all immigrants who were born outside the Nordic region; 7 were born in Europe, 42 in Asia, 17 in Africa and 8 in South America. A majority of the respondents (77%) were married or cohabiting, but as seen in , significantly more women were living alone. However, although men were more often cohabiting than the women, they were more dependent in instrumental activities of daily living (I-ADL); a statistical difference was found between men and women for “shopping” and “cooking” ().

Table 1. Demographic data and characteristics of the patients in the study (n = 74).

Regarding the respondents’ occupations and employment status, 38% reported that they were working, and 10% reported that they were studying. Half of the group reported that they did not work, 5% were seeking work, 28% had sickness benefits, 3% had support from social services and there was no further information for 16% of the respondents (the reasons for the lack of information were unknown).

Some patients had not undergone an EMG examination for unknown reasons. For patients who had an EMG examination of one or more extremities, about twice as many patients had polio verified by EMG in the lower extremities than in the upper extremities ().

Table 2. Polio-affected extremities in the patients in the study as verified by EMG examination.

The NRH classification of polio severity [Citation23] showed that most patients had polio in a lower extremity and that the most common classification groups were classes IV and V (). Clinically unstable polio and severely atrophic polio were uncommon in the upper extremities.

Table 3. Severity of polio in the patients in the study according to the NRH limb classification (n = 74).

Regarding mobility problems, 61% reported they could move independently outdoors, and there were no differences in mobility problems in groups according to marital status, (x2 = 0.04, p = 1.0). The other 39% needed mobility aids and help from another person to move outdoors. Depending on the level of impairment, different mobility aids were used, and the respondents often reported using several aids (i.e., several options were available to them). The respondents most often used a cane, crutches, or walker (62%). Some respondents needed a lower leg bandage (14%) or a whole leg bandage (19%) when walking. Another 22% reported that they used a manual wheelchair, 27% reported using an electric wheelchair and 26% did not report any need for mobility aids.

A total of 43 respondents reported having a driving license, and nearly half of the group drove a car with some sort of adaptation (46%). Notably, 45% of the active drivers were women, and active driving status did not differ according to marital status (living alone versus cohabiting) (x2 = 0.22, p = 0.73). The respondents reported some barriers when using transport modes such as trains, trams, buses, ferries and cars. The self-perceived transport difficulties concerned mobility issues such as transferring from their home to the bus stop and/or getting on or off the bus. The relationship between independent mobility outdoors and dependent mobility outdoors was analyzed and compared according to different variables from the questionnaire (). Although the respondents reported mobility difficulties when using all the transport modes, a significant difference between independent versus dependent mobility outdoors was only found for difficulties experienced with transferring to a car.

Table 4. A comparison of independent versus dependent mobility outdoors according to patient characteristics and self-perceived difficulties.

The respondents often reported pain. Indeed, 72% reported having constant pain or often having pain. Another 28% reported having no pain or seldom having pain. Of the respondents, 24% reported that their need for pain relief was satisfactory, 43% reported partial pain relief, and 23% did not have satisfying pain relief. Many respondents (36%) reported that they often or constantly felt depressed, with no difference between women and men (x2 =0.41, p = 0.63). However, there was a significant difference in feelings of depression between those with independent mobility versus dependent outdoor mobility (). Those who were dependent on others for their outdoor mobility were also more often unemployed ().

Discussion

This study described the characteristics of patients with late effects of polio who reside in Sweden but who were born in other countries or continents. In Swedish clinical settings, this younger group is important to consider as the need of care and support for polio patients has been questioned and decision makers (such as health commissioners) do not think they exists. In Sweden, vaccination against polio began in the late 1950s, so native polio survivors are most often over 65 years old. Accordingly, we could not compare this cohort to a Swedish cohort of the same age. The participants reported a high degree of independence in personal activities of daily living (P-ADL). However, in line with previous research [Citation22], they more often showed dependence on others for the instrumental activities of daily living (I-ADL), which are often mobility-related. In a previous Swedish survey of stroke survivors, one-fifth of respondents reported outdoor mobility problems 5-years post stroke [Citation26]. The reported barriers often concerned mobility problems such as transfer to/from a specific transportation mode.

Although many of the respondents in this study could move independently outdoors, nearly 40% needed mobility aids or help from another person. Depending on their level of impairment, the respondents often needed mobility aids, especially canes/crutches, manual wheelchairs and electric wheelchairs. This is in accordance with earlier studies [Citation17,Citation27]. The need of mobility aids or assistance of another person could be explained by the fact that twice as many participants had polio as verified by EMG in their lower extremities than in their upper extremities. A high number of patients had, according to NRH classification, generally weaker limbs (class IV) or severely atrophic limbs (class V).

Having weak and/or atrophic lower extremities noticeably affected the respondents’ mobility and transport modes, and difficulties with transportation modes were often reported due to mobility and transfer problems. In order for a specific transportation mode or service to be used, it needs to be both accessible (e.g., one must be able to get to the bus stop) and also adaptable (e.g., it must be able to accommodate someone in a wheeled mobility aid) [Citation11]. This was especially true for respondents who used wheelchairs. A wheelchair may be needed for longer journeys outdoors for those with limited walking ability, but crutches are more useful indoors or for shorter distances. However, we do not know which mobility aids the respondents used outdoors.

The respondents reported some barriers to using different transport modes. Those who were dependent outdoors (i.e., who needed help from another person and who needed mobility aids) had significantly more mobility problems when using a car. The mobility problems were related to transferring to and from a car (e.g., from the house to the parking lot) and to getting into and out of a car. Getting into and out of a car involves several steps: lowering down onto the seat and getting up out of the seat, swiveling around to and from the driving position and getting one’s legs into and out of the footwell. Impairment severity and the types of walking aids also impacted the respondents’ access to a car. Therefore, some people living with the late effects of polio might need other types of aids in the car or specific car adaptations, such as swiveling cushions, adapted seats, or wheelchair hoists [Citation11].

Interestingly, 57% of the respondents reported having a driving license and being active drivers. Nearly half of the active drivers drove a car with some sort of adaptation, although we did not collect data about the types of car adaptations that were used. A driver with physical impairments can drive independently with the right type of adapted driving equipment, such as hand controls and steering wheel spinners [Citation11]. Moreover, in order to be independent, the driver needs to be able to transfer into and out of the car and may need storage for a wheelchair. In Sweden, a lack of accessibility to public transport due to a permanent disability can be compensated by a Special Transport Service (Taxi), but there is also the option of receiving a car allowance to buy and/or adapt a car. Having independence in terms of mobility gives one the opportunity to take part in different activities, which benefits both the individual and society, as the need for help and support decreases [Citation9]. Accessibility to transportation is critical for employment success [Citation12]. Notably, in a previous study of drivers with physical impairments, more than 80% of the participants reported they needed a car to get to their workplace [Citation9]. People with disabilities face a number of barriers in their work life related to recruitment procedures. In this study, nearly 50% of the respondents were working or studying. Previous research on participation in daily life of patients with late effects of polio found that more restrictions were reported for occupations related to family roles, work and education and independence outdoors [Citation28].

The interactions of environmental and personal factors can impact mobility, and other variables and psychosocial issues can also present barriers for young immigrants in Sweden, including cultural, social and gender-specific barriers [Citation29]. There was a gender difference regarding the participants’ marital status in the group, as nearly 90% of the male participants were married or cohabiting. In a previous study of patients with late effects of polio, the male patients more often reported a higher quality of life than did female patients [Citation16]. Mobility and quality of life can be linked in different ways and may vary between people, places and activities. A previous study reported higher distress in everyday activities in younger people with late effects of polio [Citation30]. In this study, many respondents reported that they often or constantly felt depressed, but there was no difference between men and women. The underlying reason for their self-perceived depression is unknown. However, it has been reported previously that some post-polio survivors feel that new symptoms are like a second disability, which frequently leads to anxiety and depression [Citation31,Citation32]. Furthermore, anxiety about employment and other psychosocial factors may also have effects on immigrants. Both the disability and being an immigrant interact and affect the participants’ participation in society and impact their health [Citation33]. Furthermore, the majority of our respondents reported that they were often or constantly in pain, which is in accordance with other studies [Citation19,Citation34–36]. This, along with muscular weakness and fatigue, may also contribute to their self-perceived depression.

Dependency during mobility-related activities, such as cleaning, transportation and shopping, has previously been associated with restrictions in daily life activities for people with poliomyelitis [Citation14]. Independent mobility is very important for participation in activities outside the home [Citation37]. Patla and Shumway-Cook note, “When impairments in mobility restrict the ability of individuals to move about in their natural environment in order to carry out activities essential to daily life, mobility itself becomes the disability” [Citation7]. One common goal in planning transportation and infrastructure is making public transport systems accessible to all kinds of people [Citation38]. There are alternatives, such as buses equipped with low entry access that are height-adapted to bus stops or specific spaces for those in wheelchairs. Some places have other transport options, like Special Transport Service and shuttle services, but these are not available to all people, and their availability differs in different cities and countries [Citation14].

One limitation of this study was that it did not take into account the respondents’ knowledge of Swedish, which may have impacted the response rate. Moreover, we did not collect data about how many years the respondents lived in Sweden. However, although some of the respondents may have had some difficulty with Swedish, nearly 50% of them were working or studying. Our results show that this population presents new challenges, both to society and to the Swedish health care system. Due to time and monetary reasons, outdoor mobility training is rare in most rehabilitation settings. Often there is a focus on the patients’ physical functions, treatments and aids but there is no time for out-door mobility and training. More work is needed within rehabilitation that focuses on mobility barriers outdoors, but there are several other factors that need to be considered. In addition to functional status, there are changes over time, such as changes in occupational status, language skills and social and cultural integration, that affect young immigrants in Sweden who are living with the late effects of polio. Living with a disability as an immigrant necessitates interventions from various professionals to prevent involuntary isolation and enable participation in work, education and social life [Citation15].

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the expert assistance of Eva-Lena Bustrén, PT, MSc, who helped with the database, and we thank the participants, who willingly responded to the questionnaire, sometimes with the help of interpreters.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Post-Polio Health International. St. Louis, MO: PHI; 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 1]. Available from: http://www.post-polio.org/edu/pabout.html.

- Farbu E. Update on current and emerging treatment options for post-polio syndrome. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010;6:307–313.

- Trojan DA, Cashman NR. Post-poliomyelitis syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31:6–19.

- Brogardh C, Lexell J. How various self-reported impairments influence walking ability in persons with late effects of polio. NeuroRehabilitation. 2015;37:291–298.

- Peters B. A framework for evaluating adapted passenger cars for drivers with physical disabilities [PhD thesis]. Linköping, Sweden. Institute of Technology, Linköpings University; 2001.

- Oxley J, Whelan M. It cannot be all about safety: the benefits of prolonged mobility. Traffic Inj Prev. 2008;9:367–378.

- Patla AE, Shumway-Cook A. Dimensions of mobility: defining the complexity and difficulty associated with community mobility. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7:7–19.

- Zeilig G, Weingarden H, Shemesh Y. Functional and environmental factors affecting work status in individuals with longstanding poliomyelitis. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35:22–27.

- Henriksson P, Peters B. Safety and mobility of people with disabilities driving adapted cars. Scan J Occup Ther. 2004;11:54–61.

- Santos Tavares SI, Sunnerhagen KS, Willén C, et al. The extent of using mobility assistive devices can partly explain fatigue among persons with late effects of polio – a retrospective registry study in Sweden. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:709–714.

- Pellerito JM. Driver rehabilitation and community mobility, principles and practice. St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Mosby; 2006.

- Martha TM. Rethinking equality and difference: disability discrimination in public transportation. Yale Law J. 1988;97:863–880.

- WHO. Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002 [cited 2018 Nov 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/icfbeginnersguide.pdf?ua=1:

- Thoren-Jonsson AL, Grimby G. Ability and perceived difficulty in daily activities in people with poliomyelitis sequelae. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33:4–11.

- Santos Tavares Silva I. The dynamic nature of participation experiences, strategies and conditions for occupations in daily life amongst persons with late effects of polio. [PhD thesis]. Gothenburg, Sweden: Gothenburg University; 2016.

- Jung TD, Broman L, Stibrant-Sunnerhagen K, et al. Quality of life in Swedish patients with post-polio syndrome with a focus on age and sex. Int J Rehabil Res. 2014;37:173–179.

- Vreede KS, Sunnerhagen KS. Characteristics of patients at first visit to a polio clinic in Sweden. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150286.

- Young CA, Quincey A-MC, Wong SM, et al. Quality of life for post-polio syndrome: a patient derived, Rasch standard scale. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40:597–602.

- Werhagen L, Borg K. Survey of young patients with polio and a foreign background at a Swedish post-polio outpatient clinic. Neurol Sci. 2016;37:1597–1601.

- Vreede KS, Broman L, Borg K. Long-term follow-up of patients with prior polio over a 17-year period. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48:359–364.

- Stressel D, Hegberg A, Dickerson AE. Driving for adults with acquired physical disabilities. Occup Ther Health Care. 2014;28:148–153.

- Thorén-Jönsson A-L, Willén C, Sunnerhagen KS. Changes in ability, perceived difficulty and use of assistive devices in everyday life: a 4-year follow-up study in people with late effects of polio. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;120:324–330.

- Halstead L, Gawne AC. NRH proposal for limb classification and exercise prescription. Disabil Rehabil. 1996;18:311–316.

- Mühr O, Persson HC, Sunnerhagen KS. Long-term outcome after reperfusion-treated stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49:316–321.

- Larsson J, Björkdahl A, Esbjörnsson E, et al. Factors affecting participation after traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45:765–770.

- Persson HC, Selander H. Transport mobility 5 years after stroke in an urban setting. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2018;25:180–185.

- Sandberg A, Stålberg E. Changes in macro electromyography over time in patients with a history of polio: a comparison of 2 muscles. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1174–1182.

- Larsson Lund M, Lexell J. Perceived participation in life situations in persons with late effects of polio. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:659–664.

- Santos-Tavares I, Thoren-Jonsson AL. Confidence in the future and hopelessness: experiences in daily occupations of immigrants with late effects of polio. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:9–20.

- Thorén-Jönsson AL, Hedberg M, Grimby G. Distress in everyday life in people with poliomyelitis sequelae. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33:119.

- Gawne AC, Halstead LS. Post-polio syndrome: pathophysiology and clinical management. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 1995;7:147–188.

- Shiri S, Wexler ID, Feintuch U, et al. Post-polio syndrome: impact of hope on quality of life. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:824–830.

- Santos Tavares Silva I, Thorén-Jönsson A-L, Sunnerhagen K, et al. Processes influencing participation in the daily lives of immigrants living with polio in Sweden: a secondary analysis. J Occup Sci. 2017;24:203–215.

- Kling C, Persson A, Gardulf A. The health-related quality of life of patients suffering from the late effects of polio (post-polio). J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:164–173.

- Werhagen L, Borg K. Impact of pain on quality of life in patients with post-polio syndrome. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45:161–163.

- Stoelb BL, Carter GT, Abresch RT, et al. Pain in persons with postpolio syndrome: frequency, intensity, and impact. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1933–1940.

- Asplund K, Wallin S, Jonsson F. Use of public transport by stroke survivors with persistent disability. Scan J Disabil Res. 2012;14:1–11.

- Risser R, Lexell EM, Bell D, et al. Use of local public transport among people with cognitive impairments – a literature review. Transp Res Part F Traff Psychol Behav. 2015;29:83–97.