Abstract

Purpose: The efficacy of a community-based mentoring program for adolescents with a visual impairment vs. care-as-usual was tested on social participation including satisfaction with social support.

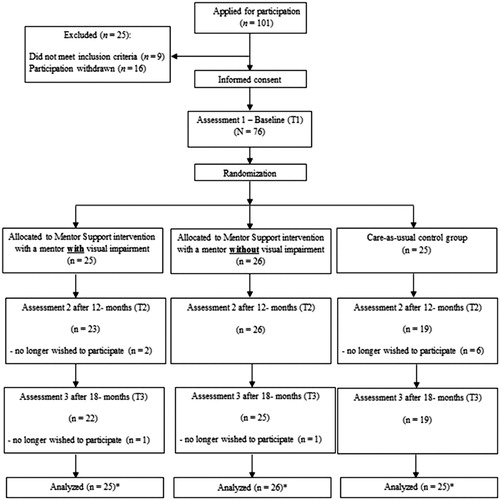

Materials and methods: Adolescents (15–22 years; 46% boys) were randomized to an intervention group with mentors with visual impairment (N = 25), an intervention group with mentors without visual impairment (N = 26), or care-as-usual (N = 25). One-on-one mentoring activities regarded school/work, leisure activities, and social relationships.

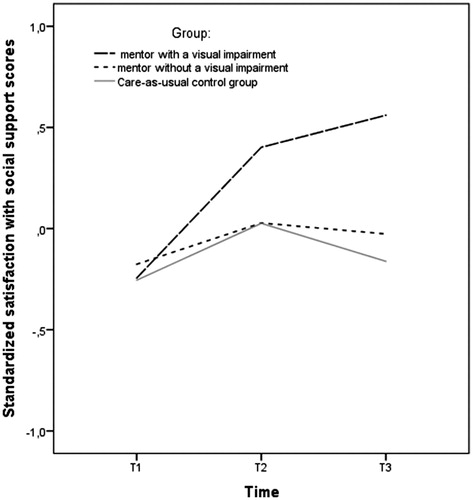

Results and conclusions: Multilevel growth modelling revealed no effect of mentoring on changes in social participation compared to the care-as-usual group (participation [95% CI –0.30, 0.21, d = 0.1]; social participation composite [95% CI –0.24, 0.26, d = 0.24]). Mentees matched to mentors with visual impairments increased more on satisfaction with their social support compared to mentees matched to mentors without impairments and the care-as-usual group [95% CI 0.02, 0.49, d = 0.38]. Age, characteristics of the impairment, and number of match meetings were not associated with change in social participation during the mentoring program. This evaluation showed no benefit of mentoring for social participation of adolescents with a visual impairment. The value of mentors and mentees sharing the same disability needs further investigation. This trial is registered in the Netherlands Trial Register NTR4768.

A community-based mentoring program resulted in no benefits for adolescents with a visual impairment on their social participation.

A community-based mentoring program should not replace care-as-usual provided to young people with a visual impairment in the Netherlands. It could only be thought of as an additional service within rehabilitation.

Matching mentees and mentors based on sharing the same disability could strengthen the effect of a community-based mentoring program. However, these benefits are rather small.

Providing additional support for the social participation of young people with a visual impairment might be especially helpful for those with a progressive impairment and with comorbid problems.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Having a disability can limit participation in daily living activities and reduce participation in social activities [Citation1–3]. In particular, young people with a visual impairment face challenges with establishing and maintaining relationships, performing group leisure and physical activities, and building successful school and work careers [Citation4–12]. These forms of social participation are vital to successfully completing social developmental tasks on time and contribute to health, psychological wellbeing, and quality of life [Citation13,Citation14]. Successful social participation is especially important during adolescence when major life transitions occur such as transitioning from school to employment, exploring romantic relations, and commencing independent living [Citation15]. Given the compromised social opportunities for young people with a visual impairment, effective programs aiming to improve social participation are needed.

Social participation

In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced a framework, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), to conceptualize functioning of people with a disability [Citation16]. Within this framework, participation is presented as a key component that classifies a person’s functioning in addition to body functions and structures, activities and contextual factors. Several studies have emphasized the complexity of the concept of participation [Citation17,Citation18] and underlined that a clear definition is still lacking [Citation19]. In the ICF-model, participation is defined as “involvement in a life situation” [Citation16]. Social participation not only captures the aspect of capacity and performance, but also involves aspects of social integration and inclusion [Citation20].

Social participation occurs within three subdomains, namely education and employment, social relationships, and leisure activities [Citation5]. Having a visual disability may impact social participation in all of these domains. Imms et al. [Citation21] suggested that interventions enhancing social participation in people with disabilities could be divided into two traditions. The first tradition is derived from the “biomedical” model. Interventions based on this tradition target body structure and functions to enable functions that facilitate participation. An example might be the implementation of an intervention designed to promote motor performance or working memory [Citation22]. However, little evidence exists for the effectiveness of the biomedical approach for actually increasing social participation [Citation17, Citation23].

The second tradition described by Imms et al. [Citation21] is based upon a multidimensional worldview, in which overcoming psychosocial resistance, the use of social models, and social inclusion are important strategies for increasing social participation [Citation23]. Social inclusion strategies focus on creating possibilities for every person to participate in the same activities as others. An example of this type of intervention is mainstream education with individualized support for children with disabilities [Citation24]. There is some evidence to support this approach for increasing social participation, but this evidence is still weak [Citation25]. Therefore, more research is needed to explore the potential positive effects associated with interventions designed to enhance social participation of people with disabilities. Community-based, one-to-one mentoring could be conceptualized as being an example of a social inclusion intervention and, thus, potentially a way to enhance social participation.

Community-based mentoring

An important factor that fosters resilience in young people is having connections with the community, such as bonds with non-related adults and positive role models [Citation26]. Mentoring programs involve a caring and supporting relationship between a young person and a non-parental older person [Citation27]. There is a great diversity of mentoring programs within different settings. Community-based mentoring programs support mentor–mentee matches that take place within the community on mutually convenient locations and times [Citation28]. Meetings within a site-based mentoring programs mostly take place within predetermined settings (e.g., schools, workplace or a religious context) and at fixed scheduled meeting times (e.g., 1 h each week after regular school hours). The context of mentoring program was found related to program effectiveness, favoring community-based mentoring program [Citation29].

The effects of community-based mentoring programs on young people’s development and wellbeing have been reported across multiple studies [Citation26]. Although these results seem promising, the effect size is relatively small. Improvements were especially evident within the subdomains of education and employment, including increased educational engagement and performance, reduced school drop-out, and enhanced employment rates [Citation17,Citation30,Citation31]. Mentoring programs have also been shown to be effective in enhancing social relations [Citation26] including improvements in relationships with parents, teachers [Citation32], and peers [Citation33]. Less evidence exists for the effect of mentoring on increasing participation in leisure activities and to the best of our knowledge, no evidence exists for demonstrating the effectiveness of mentoring programs on improving all three subdomains of social participation.

Six programmatic standards about how to create, sustain, and improve mentoring relationships have been outlined [Citation34]. For example, recruitment materials should contain realistic perspectives of mentoring activities to prevent unrealistically high expectations in mentors which can lead to premature closure and deleterious outcomes [Citation35]. Pre-match training, to manage goals and expectations for being a mentor, can increase mentor’s preparedness and self-efficacy [Citation36] and is therefore prescribed as a benchmark practice for mentoring programs as well. Further, mentoring programs should match mentors and mentees based upon mutuality in interests rather than matching on surface-level characteristics, such as gender, ethnicity, or race [Citation37].

The importance of mentor program design is underlined by meta-analyses DuBois et al. [Citation26] showing significant heterogeneity of mentoring effectiveness. In addition to individual participant characteristics (e.g., level of behavioral problems, gender, household composition), program practices (e.g., matching procedures, background characteristics of mentors) were associated with the effect sizes for the impact of mentoring programs on youth outcomes. DuBois et al. concluded that program effectiveness would be enhanced when programs had a relatively low proportion of female mentees participating; had mentees with either a background of relatively low individual risks and high environmental risks, or were not high on both risk factors; included an advocacy and teaching/information role for mentors; and based on their matching criteria on similarity of interests and not on similarity of ethnicity/race [Citation26]. Rhodes [Citation38] described that factors related to the interpersonal history, developmental stage, social competence, family and community context, demographic factors, and program practices would influence the positive effects of mentoring on youth outcomes.

Mentoring for youth with disabilities

Several studies have examined the effectiveness of mentoring on youth with a disability or chronic illness [Citation39–43]. These studies show positive effects of mentoring relationships on a variety of youth outcomes, such as self-efficacy, academic success, problem-solving skills, employment, and communication skills. Just a small number of studies have been conducted with young people with a visual impairment. Positive effects of mentoring were found for academic achievement and career success within young people with a visual impairment, aged 16–26 years [Citation44]. However, the study did not include a control group. In contrast, O’Mally and Antonelli [Citation45] used random assignment to either mentoring or care-as-usual. With this controlled design, they did not find a significant intervention effect of mentoring on employment rates and job satisfaction. Mentees, aged 20–35 years with a visual impairment did improve in their assertiveness skills for job hunting compared to the control group. These two studies only focused on one domain of social participation (i.e., education and employment). As a result, the impact of mentoring on leisure activity involvement and social relationships of young people with a visual impairment is not known.

Both Bell [Citation44] and O’Mally and Antonelli [Citation45] matched legally blind mentees with legally blind mentors. They proposed that similarity in disability would potentiate positive outcomes in mentees. Nevertheless, Britner et al. [Citation39] concluded that matching based on having similar disability might only benefit mentees who have not been exposed to positive role models with similar disabilities previously. Specifically, one study did randomly assign students with a wide variety of disabilities to either a mentor with or without similar disability-challenges or a control group, but no differences in youth outcomes were found [Citation46]. While the results of these previous studies do not indicate that having a mentor with a similar disability confers benefits to their mentees, this had not been tested for youth with a visual impairment using mentors with and without a visual impairment.

The current study

In the current study, we used a randomized controlled trial design to study the efficacy of a community-based mentoring program for improving the social participation of youth with a visual impairment [Citation47]. The primary aim of the study was to compare those who received the mentoring intervention to those who only received care-as-usual. Based on previous work on community-based mentoring programs [Citation26], participants receiving mentoring support were expected to increase more on their social participation than participants receiving no mentoring support. A secondary aim of this study was to test the effect of matching mentees with a mentor with a similar disability (a visual impairment) or to a sighted mentor without disabilities. As previous evidence was limited, the secondary aim was exploratory. Based on prior research, potential moderators such as age, severity of the visual impairment, comorbidity, and treatment adherence were hypothesized to be associated with program efficacy and were tested in the current study.

Methods

Study design

The study followed a randomized controlled trial design with two experimental groups and one care-as-usual group. Full details of the study protocol and the content of the mentoring program were reported in studies by Hepp et al. [Citation47,Citation48]. Randomization stratification on geographic proximity to ensure equal allocation to regions as well as to reduce travel time for mentors to the homes of mentees was conducted by an independent researcher with the use of a computerized random number generator. Participants within each regional group were block randomized into the following study groups: (1) the “Mentor Support” program group consisting of mentors with a visual impairment (visual impairment mentor group), (2) the “Mentor Support” program group consisting of mentors without a visual impairment (no-visual impairment mentor group), and (3) the care-as-usual group. All youth with a visual impairment across all three study conditions received usual care provided by the rehabilitation centers throughout the Netherlands. This study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Authors’ University and is registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (NTR4768). Reporting conformed to the CONSORT Statement (CONSORT 2010 statement [Citation49]).

Participants

Inclusion of participants began in September 2014 and the last follow-up measurement was completed in May 2017. Participants were eligible for participation if they were aged 15–22 years old, living in the Netherlands, and diagnosed with a visual impairment. Visual impairment was defined as an impairment in vision including both the conditions of blindness and being partially sighted, which even with assistance from the use of visual aids affects a person’s social participation. Adolescents having severe additional impairments, such as complete deafness or an intellectual disability were not eligible to participate in the present study. Another exclusion criterion was not having a mastery of the Dutch language. As shown in , participants in the mentoring condition and the care-as-usual group did not differ significantly from one another at baseline (p > 0.05) on age, gender, education history (special or mainstream education), comorbidity (e.g., hypermobility, mild hearing loss, diabetes), or characteristics of their impairment. No differences were found between the three conditions (VI mentor group, no-VI mentor group, and care-as-usual group) for the same demographic variables at baseline.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Procedure

Participants were recruited for one year beginning in September 2014 from two national service organizations for people with visual impairments in the Netherlands (Bartiméus and Royal Dutch Visio) as well as through online banners on social media, brochures, and internet-magazine-website advertisements. After participants signed up via the recruitment website (accessible for people with visual impairments), they were contacted by telephone or email to assess their eligibility for the study. Eligible adolescents and their parents (if participants were under 18) received an information letter and informed consent form. In this information letter, the purpose and procedures of the study were explained. All participants were told that they had “a chance” of being assigned to the mentoring program. After participants provided informed consent, they were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions. Those assigned to the care-as-usual group were called on the telephone by the first author and informed about the results of the randomization procedure. Parents also had the opportunity to ask questions during these conversations. An e-mail summarizing the conversation was sent to the participants and/or their parents following the telephone interview. Those assigned to a mentor were informed about the results of the randomization process by email.

Baseline measurements (T1) were conducted through computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) at the authors’ University before participants were randomly allocated in blocks of 15 adolescents within each region by an independent researcher. Post-test measurements (T2) took place after 12 months and follow-up measurements (T3) after 18 months post-match. This process was started at two time points. Cohort 1 began in May of 2015 and Cohort 2 began in November of 2015. Matching of mentees and mentors took place within one month after the baseline measurements were completed.

All measurements were conducted by extensively trained interviewers. The interviewers were trained on two separate days for a total of 8 h. The training was provided by the first and the third author of this current study and the content of the training was support by a training manual that was set up before the start of the study. Within the training manual information on the content of the study, answers to frequently asked questions, and predetermined synonyms for difficult words could be found. During the training, the interviewers practiced interviewing in couples by taking turns in being the interviewer or the participant. After the first training day, interviewers had to practice further at home by interviewing two persons from their own social network. In the second training day, their experiences were evaluated and feedback was provided by the trainers. At T2 and T3, new interviewers were recruited and extensively trained in order to keep the interviewers blinded.

As the flowchart shows (), 76 participants were assessed at baseline. The recruitment goal was 120 participants based upon the power analyses [Citation47]. However, only 101 candidates applied to participate in the study, of which nine were not eligible (having severe additional impairments) and 16 withdrew from the study, because they chose to participate in other support programs. A total of 51 of the 76 participants were randomized into one of the two experimental conditions and 25 to the control condition. Due to the complexity of implementing a long-term mentoring program in natural settings within a low incidence population, matching mentors and mentees based on randomization in either the mentoring condition with or without a visual impairment was not always possible. Nine matches were not based upon randomization and therefore, they were excluded from the analyses examining the impact of match similarity on mentee outcomes.

Figure 1. Participant flow through study. *Longitudinal analyses include all available data from each subject up to withdrawal or study completion.

Of the 51 participants randomized to one of the experimental groups, four participants dropped-out of the study. A total of six participants from the care-as-usual group withdrew from the study. As a result, 47 experimental (93% of allocated) and 19 control (76% of allocated) participants completed the study. The drop-out rate of the total study (N = 76) was about 13%. Analyses comparing those who dropped-out and those who remained in the study showed no significant differences with respect to participants’ age, gender, onset of the visual impairment, severity, prognosis, inherited condition, comorbidity, or educational history (i.e., enrolled in special or mainstream education) (p > 0.05). Based on the 76 participants within two groups, we achieved lower-than-planned power (0.47) to detect a medium effect size in a within-between group design (f = 0.25; α = 0.05, two –tailed) (Gpower [Citation50]). Post hoc sensitivity analysis with β = 0.80 yielded a medium effect size of f = 0.36, given the sample size of n = 76.

Mentoring program

The mentoring protocol and program, called Mentor Support, was designed based upon the Elements of Effective Practice for Mentoring (EEPM) [Citation51,Citation52]. For example, mentors were extensively trained pre-match; criminal background checks were conducted on mentors as part of pre-match screening; matching was based upon mentors and mentees having common interests; and at least one post-match training was conducted with mentors. The program studied was self-designed by the first, second, and fifth author and described in a Mentor Support Handbook (Mentor Support Handbook; by Heppe, Kef, and Schuengel). Exercises and assignments in the Mentor Support Handbook were offered in the form of suggestions to the mentors and mentees in order to preserve their intrinsic motivation for participation.

The primary purpose of the Mentor Support program was to improve the social participation of youth with a visual impairment in three domains of social participation: (1) school/work, (2) leisure activities, and (3) social relationships. In total, Mentor Support consisted of 12 planned face-to-face meetings (number of meetings provided by mentors; M= 6.45, min = 1 max = 13, SD = 4.28) of a mentor and mentee across an overall period of 12 months. On a weekly basis, dyads also had contact with one another via email, internet, or telephone. Meetings took place in or near the mentee’s homes and were mostly conducted outside of the house. Activities (e.g., going to the movies, theater, library or art gallery, inviting friends over for a high-tea or preparing a meal for friends, participating in (unknown) sports, and discussing personal goals over lunch, dinner or drinks) accomplished during the meetings were based on mentees' interests or goals, or came from ideas as described in the Mentor Support Handbook. Having success experiences and positive thinking were the main focus of the meetings. The mentors role was to guide, to give advice, and to support mentees by providing mentees information, modeling possible actions, and offering strategies on how to improve their social participation.

Volunteer mentors were recruited through online banners on social media, brochures, and advertisement in internet-magazines. Mentors had to sign up through the Mentor Support recruitment website, where they entered information about their backgrounds, such as their age, educational background, working history, and impairments. Volunteers who met the inclusion criteria (aged between 18 and 45 years and either having a visual impairment or not having any type of disability) were invited to participate in an intake interview conducted by the first author. These structured in-depth telephone interviews contained questions about the volunteers level of social participation, life experiences, expectations for being a mentor, understanding of the responsibility of being a mentor, ideas on how to establish a mentoring relationship, and their level of commitment to the mentoring program. After the intake interview, each candidate was discussed within a research team consisting of the first and third author and additional research staff. Volunteers were excluded when they had a pervasive lack of social participation, mental health issues, were overcommitted, or in search of new friends. Eligible volunteers were emailed and invited to participate in a two days, 4 h, in person, training workshop. This workshop included the topics of do’s and don’ts, safety, and strategies for establishing a positive mentor–mentee relationship (Mentor Support Training Manual; by Heppe, Kef, and Schuengel). Mentors had to sign an informed consent form and submit a certificate of good conduct (i.e., obtained from their town council that declares if a person had committed criminal offences relevant to the performance of duty) before being matched.

Based on this extensive screening process, 50 volunteers were eligible to be mentors. During the study, three mentors were excluded because they did not live within the geographic proximity to the homes of the mentee. Of the remaining total (N = 47) almost 60% were female and 57% had a visual impairment. Their ages ranged between 22 and 44 years (M = 31.64, SD = 6.53) and 64% were involved in a romantic relationship. Only 8 mentors were not employed at the moment and 34% of those with a job were employed in a helping profession. More information about the selection process and background characteristics of mentors can be found in a recent study [Citation48].

No material incentives were provided for participation as a mentor or research participant in this study. An official certificate was provided by the authors’ university when mentors successfully completed the training, attended supervision groups, and completed the evaluation forms after every meeting with their mentee. Furthermore, mentors were provided with a financial budget of 420 Euros to support the costs of their match activities with their mentee. After randomization, matching of the mentees and mentors was based upon their geographic proximity to one another. Then, matches were made based upon mentors and mentees having similar interests. A self-designed questionnaire with four questions was administered before randomization to assess participants’ and mentors’ interests.

Measures

Several questionnaires were used to assess social participation within the three domains: school/work, leisure activities, and social relationships.

Primary outcome measures

Participation scale. The Visual Activity and Participation (VAP) scale [Citation53] was used to assess participation. The VAP scale was specifically designed to assess visual functioning, self-reliance, and participation in young people with a visual impairment and was based upon the ICF framework. In the current study, two of the three subscales of the questionnaire were used, namely the self-reliance subscale (20 items) and the problematic participation subscale (20 items). Self-reliance assesses the ability to perform a task of daily living (e.g., How independent are you in finding your way to the grocery store or library?; How easily do you make social contact with peers?; How independent are you in participating in sports?). Problematic participation assesses participants’ perceptions about whether their performance is normal or problematic (e.g., Do you believe that your participation in this activity is normal or problematic?). A 10-point rating scale for each item was completed ranging from 0 for “always needed help” to 10 “independent” for the first scale and “problematic or no participation” (0) and “normal participation” (10) for the second scale. Thus, the measure included both the activity (self-reliance) and participation (problematic participation) ICF-codes. A mean score of the 40 items was used in the analyses and higher average scores indicated higher levels of social participation. The internal consistencies of the questionnaire were good at T1 (α = 0.91), T2 (α = 0.95), and T3 (α = 0.95). This measure was used in one previous study to study participation in 26 low sighted youth (aged between 12 and 18 years). A total internal consistency score of the measure, taken the two subscales together, was not provided. However, the internal consistency scores of the two subscales separately were good (self-reliance α = 0.83; problematic participation α = 0.91) [Citation53].

Social participation composite score. In the interview, 13 questions were asked about the three areas of social participation including: school/work (e.g., Do you have a job?; How many hours a week do you work?), leisure activities (e.g., Do you do sports?; What kind of activities do you perform during your leisure time?; Are you a volunteer?), and social relationships (e.g., Do you have a romantic relationship?; How many times did you have a romantic date?). Ten out of the 13 questions were answered by a yes (1) or no (0). One question measuring the amount of sport activities completed during a typical week was dichotomized as (1) two or more than two times a week and (0) less than two times a week. Also two questions measuring full-time or part-time voluntary and paid employment were dichotomized as (1) working 24 or more hours a week (0) working less than 24 h a week. These two questions were mutually exclusive and could not both be true, because having a paid job for 24 h or more within a 40 h workweek leaves no option for also working 24 h or more as a volunteer. Therefore, a summed score of 13 was not possible and answers could range between 0 and 12. Higher scores on this social participation composite score reflected higher levels of social participation.

Secondary outcome measures

Degree of peer activity (DPAL) was assessed with a Dutch translation of the DPAL questionnaire measuring the amount and frequency of peer contact in leisure time [Citation54]. This questionnaire consists of five items rated on a six-point response scale ranging from “never” to “every day”. An example of a question is: “How many times do you meet with friends outside school?”. High scores on this questionnaire indicate more leisure activities. The internal consistencies of the questionnaire were acceptable at T1 (α = 0.67), T2 (α = 0.62), and T3 (α = 0.65). In a previous study among typically developing adolescents (N = 8206), aged between 14 and 18 years old, the internal consistency was also acceptable α = 0.68 [Citation54].

Social network size was assessed with the Social Network Map [Citation7, Citation55] measuring the size of the social network. The original map uses a technique in which a circle is drawn to display the social network visually. As a visual map is not of added value for our participants due to their visual impairment, data were collected by asking them to list network members for every subdomain orally. The seven original subgroups of people included relatives (i.e., father, mother, brothers/sisters), family, friends, colleagues from work or peers from school, peers from clubs or organizations, neighbors, and service providers. Also, one subgroup was added of “people you live with”, because participants could also live within or near a rehabilitation center or a school offering special education services during week days. The social network was mapped out by asking, “First, think of people in your family. Who do you want to include in your Social Network Map?” People could not be included in the Social Network Map twice. All of the unique individuals within one subgroup were counted. A total network size was calculated by summing the subtotals across each subgroup.

Perceived social support was assessed using the Personal Network List (PNL) which uses the role-relation method [Citation56]. The PNL assesses perceived social support in three domains including leisure time, school/work problems, and relational/emotional problems that is obtained from six persons (father, mother, best friend, friends, classmates, and colleagues) resulting in three items administered for each person. The three items administered for each person included: “How important is your …… (e.g., father) in your leisure time?, If you encounter a problem in school or at work, how important is your ……?, and If you encounter a problem in a relationship with another person, how important is your ……?”. Responses ranged from 10 for “not important” to 100 for “very important.” The highest score rated for mothers or fathers was selected for each item and summed into one overall perceived parent support score. The highest score of best friends, other friends, and classmates/colleagues for each item was summed to one score for perceived peer support. For both perceived parent and perceived peer support, the total summed scores ranged from 30 to 300. The internal consistency of the two sources of support on the three measurement points ranged between α = 0.69 and α = 0.88. Within a previous study, the separation of the two constructs of perceived parent support and perceived peer support was tested by a factor analysis resulting in a clear two factor structure [Citation57].

Online social support was assessed using four items from the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) [Citation58,Citation59]. The internal consistency of the MSPSS scale measure in a previous study among typically developing adolescents (N = 275), aged between 17 and 22 years old, was good α = 0.88 [Citation58]. The internal consistency of a adapted version of the MSPSS measure for Facebook use in another previous study among typically developing adolescents (N = 910), with a mean age of 15.44 years, was also good α = 0.95 [Citation59]. In the current study, the items of the original MSPSS were also modified by adding “on social media” to the questions. An example item is: “When I’m feeling down or in a difficult situation…… I can find help on social media”. Questions were answered on a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. The internal consistency of the questionnaire in our study was also good at T1 (α = 0.88), T2 (α = 0.91), and T3 (α = 0.86).

Satisfaction with social support was measured with two items [Citation7]. The first item assesses satisfaction with instrumental support (How satisfied are you with the support you get with practical problems?). The second item measures satisfaction with emotional support (How satisfied are you with the support you get for personal problems?). The questions were answered on a five-point rating scale ranging from 1 for “Strongly disagree” to 5 for “strongly agree.” The average mean of the two items was used in the analyses. The internal consistency between the items was acceptable at T1 (α = 0.58), T2 (α = 0.68), and T3 (α = 0.73).

Statistical analyses

Preliminary analyses examined the variables on outliers and skewness. No outliers were detected but the variables for participation, the VAP scale, perceived parent support, and perceived peer support were negatively skewed, with skewness ranging from –0.98 (SE = 0.17) to –0.66 (SE = 0.17). A majority of the participants had high scores on these variables. The variable social network size was positively skewed (skewness = 1.68, SE = 0.17), indicating that most participants had low scores. For handling bias as a result of these deviations from normality, the models fitted to the data were bootstrapped (stratified method, percentile confidence intervals, CIs). Confidence intervals were used to test for statistical significance.

Due to the longitudinal design of the study, with the data structure of assessment occasions nested in participants, and in order to model individual change in social participation, growth modelling with multilevel analyses in SPSS Mixed Models was conducted (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY; Statistics version 23). The multilevel model accounted for dependency among measurement points (level 1) within individuals (level 2). Intra-class correlations (ICCs) were calculated separately for each variable to calculate the proportion of variation across measurement points, compared to the proportion of variation within measurement points. No ICC levels were below 0.05 and all variables had a design effect bigger than 2.0, indicating intra-individual dependency [Citation60]. The model fitted to the data consisted of a random intercept and a random slope allowing for variation between participants.

First, to test the effect of the mentoring program, group, and interaction between group and time were entered into the model. Second, this procedure was repeated with the three-group variable (visual impairment mentor group and care-as-usual group vs. no-visual impairment mentor group). Third, differences between one of the mentoring conditions and the care-as-usual group (visual impairment mentor group and no-visual impairment mentor group vs. care-as-usual group) were tested, but were only tested when a significant difference between visual impairment mentor group and no-visual impairment mentor group was found to indicate the effect size. All analyses were performed for each outcome separately. After every analysis, a deviance statistic was computed. If the model fit improved, the multivariate bootstrapped statistics of the predictors were interpreted. An alpha of 0.05 was used to test the statistical significance of the parameters.

Finally, to test for possible predictor effects on change in social participation over time, a moderation model was tested. These analyses were only performed on participants who received the mentoring program. In the model, a random intercept and slope were included together with moderators (age, onset of impairment, severity and stability of impairment, comorbidity, and average number of match meetings) and the interaction between these characteristics and time. All characteristics were tested for the primary outcomes only. As these analyses were exploratory, CI of 99% were used to test for significant effects [Citation61].

Results

Social participation outcomes

The mean scores and standard deviations for the outcome variables operationalizing social participation are shown in . There were no significant baseline differences between participants in the mentoring condition and the care-as-usual group in outcome measures.

Table 2. Mean score and standard deviations of social participation outcome variables of both conditions, at the first assessment (T1), after 12 months at the second assessment (T2), and after 18 months at the third assessment (T3).

Growth model. Regardless of study group, a significant increase over time was found for DPAL scale and satisfaction with social support, as shown in . No significant increase or decrease over time, regardless of study group, was found for the participation VAP scale, the social participation composite score, social network size, perceived peer support, perceived parent support, and online social support.

Table 3. Parameter estimates for multilevel model of effectiveness of the mentoring intervention on social participation outcome variables.

Mentoring condition vs. care-as-usual group. As shown in , the experimental groups were not significantly related to change in any of the dependent variables.

Visual impairment mentor group vs. no-visual impairment mentor group. As shown in , the visual impairment mentor group increased significantly more on satisfaction with social support compared to the no-visual impairment mentor group. Additional analyses indicated that the visual impairment mentor group also increased more on satisfaction with social support compared to the care-as-usual group (B = 0.27, SE = 0.13, 95% CI [0.02, 0.54], d = 0.43), while the no-visual impairment mentor group was not significantly different from the care-as-usual group (B = 0.03, SE = 0.13, 95% CI [–0.24, 0.30], d = 0.05). No significant differences were found between the visual impairment mentor group and the no-visual impairment mentor group for any of the other dependent variables.

Moderation outcomes

Significant main effects were found for stability of impairment, comorbidity, and age. On average, adolescents with stable impairment (B = 0.86, SE = 0.46, 99% CI [0.06, 1.92]) and with no comorbid problems (B = –1.03, SE = 0.43, 99% CI [–1.93, –0.25]) reported higher levels of social participation on the VAP scale. Those who were younger (B = –0.32, SE = 0.15, 99% CI [–0.59, <–0.01]) reported higher levels of social participation on the social participation composite score.

No significant differences were found on the dependent variable slopes for the primary outcomes of social participation, indicating that change in social participation over time was equivalent for all mentees regardless of their age, onset of impairment, severity and stability of impairment, comorbidity, and amount of match meetings (99% bootstrapped CI contained zero in all results).

Discussion

The first aim of this study was to examine the efficacy of a community-based mentoring program to improve social participation of adolescents with a visual impairment. A secondary aim was to compare efficacy of mentees being matched with a mentor with a visual impairment to mentees being matched to mentors without impairments. The mentoring condition did not show benefits compared to the care-as-usual group. In all conditions, adolescents with a visual impairment increased in their amount of peer activity and satisfaction with social support. Despite a lack of differences between the mentoring condition and the care-as-usual group, one significant difference was found between the two mentoring groups (visual impairment mentor group vs. no-visual impairment mentor group). Mentees of mentors with a visual impairment increased more on satisfaction with social support compared to mentees with mentors who had no impairments.

Increased satisfaction with social support among mentees mentored by mentors with visual impairments could be the result of spending time with members of the same underrepresented group, who have faced and overcame the same life challenges. These “peer support” interactions could provide more satisfying views of oneself because it is easier to identify with a role model who shares important personal characteristics [Citation62–64]. Insight into the lives and experiences of a person within the same subpopulation might lead to more life satisfaction. Furthermore, providing adolescents with a role model and, thus, a potential support figure may have filled the gap in support that mentees might have experienced before they participated in the mentoring program. It is interesting that satisfaction with social support did not decrease after the post-test, this may suggest that mentors remained a source of support even after the mentoring program was completed or that other support figures in the social network of the mentees of mentors with visual impairments provided more suitable support.

The lack of support for the effectiveness of the overall mentoring program compared to care-as-usual might be the result of the lower than planned statistical power, especially for those outcomes with a medium effect size. Earlier studies showing a positive effect of mentoring programs on youth were primarily conducted in larger samples and in populations with a higher prevalence of psychosocial problems. For example, in a study conducted by Black et al. [Citation65], a moderate effect of a mentoring program to prevent obesity was found among 235 urban Afro-American youths. Similarly, Wyman et al. [Citation66] found a medium positive effect of a mentoring program in a sample of 226 at risk children. These findings are consistent with the results of a meta-analysis on the small (d = 0.21), positive effects of mentoring on youth outcomes [Citation26]. Previous studies examining the effects of mentoring on youth with visual disabilities have also used small samples (e.g., N = 49 in Bell [Citation44]; N = 51 in O’Mally & Antonelli [Citation45]) which led to methodological limitations such as lack of use of a randomized control group and conducting only univariate statistics.

Our results are also consistent with findings from previous studies on the effect of other types of programs designed to improve social participation among youth with a disability [Citation67–69]. Notably, these RCTs demonstrated no or minimal differences between those receiving the program and the control group. Several intervention methods designed to improve social participation were implemented in these studies, such as community-based exercise programs, day camps, or physical therapy. In a study testing, the effectiveness of a mentoring program for improving career-oriented outcomes for youth with a visual impairment, the primary outcome of increased employment rates was also not enhanced [Citation45]. This result is consistent with the results reported in a review on the effect of interventions aimed at improving social participation by Adair et al. [Citation17], who concluded that due to the multidimensional complexity of social participation, change in this construct is difficult to realize.

Other methodological limitations, such as a limited time frame and treatment diffusion, are unlikely to explain the findings in the present study. Treatment adherence was tested as a moderator of mentoring program effectiveness, but it was not associated with differences in social participation outcomes between the conditions. Furthermore, a time frame of 12 months with a follow-up at 18 months was regarded as a reasonable time frame for mentoring to make a contribution on youth outcomes. Research showed that mentoring programs with relationships that last at least one year show the most positive benefits in youth [Citation70] and that the effects of a mentoring program have the potential to extend a year beyond the end of the program [Citation26].

Another possible explanation for not finding differences in social participation between those receiving the mentoring program and the control group could be that the community-based mentoring program did not include all of the benchmark practices that were just recently added to the EEPM [Citation34]. This Fourth Edition containing new research-informed, safety-based, and practitioner-approved standards was released in September 2015, a few months after the first match meetings were conducted in the current study (May 2015). Most of the benchmark practices outlined in the Fourth Edition of the EEPM for recruitment, training, and how to manage relationship closure were congruent with the former editions [Citation34]. However, new benchmarks for the standards “matching and initiating” and “monitoring and support” differed from the practices implemented in this RCT. For example, in the current study, staff members were not on site during the initial match meetings, which is now a benchmark practice; less frequent monitoring contact meetings were conducted with both mentors and mentees than described in the EEPM; no in-depth assessment of the quality of the mentoring relationship in both mentors and mentees was conducted during participation in the mentoring program; and less frequent monitoring contacts with a responsible adult in the mentees’ lives were conducted provided by the program staff than required in the EEPM. Greater adherence to the benchmark practices of the EEPM was associated with positive outcomes for matches in general [Citation36]. These findings suggest that more complete implementation of the updated benchmark practices that compose the standards in the EEPM might have enhanced the efficacy of the mentoring program evaluated in this study.

Limitations

While the study’s randomized design was a particular strength that addressed many threats to validity, the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability and replicability of the findings. One possible explanation why a smaller-than-planned sample size was achieved, could be the combination of the low prevalence of youth with a visual impairment in the population and the design of the study. The fact that there was a 33% chance of ending up in the care-as-usual group and not receiving mentoring support could have discouraged participants to participate in the study, especially those who specifically sought mentoring support. Being scared and feelings of uncertainty that come along with participating in a randomized controlled trial with a no treatment control group, have been shown to be a barrier for participants before [Citation71].

Another limitation to the study was the large amount of time that participants had to overcome between recruitment and the start of the mentoring program. This delay was mostly due to needing to implement time-consuming practices related to implementing a mentoring program in natural settings such as finding and training eligible mentors within the geographical location of the mentees. Also, the low average number of match meetings might have negatively impacted the quality of the mentoring program. The more time matches spend together on a consistent basis within a significant period of time the greater the chance of developing a strong effective mentoring relationship [Citation72]. However, no statistical significant relationship was found between the number of match meetings and social participation outcomes.

Furthermore, matching mentors and mentees based on their exact visual impairment was not possible, due to the low prevalence of young people with a visual impairment. Matches could, for instance, consist of mentees who became low sighted at a later age with mentors who were legally blind from birth. Matching based on the preferences of the mentee and characteristics of the impairment might be better for creating a stronger mentor–mentee relationship. Also, matching primarily based on similarity of interests could have increased relationship quality. Due to practical constraints, matching was first based on randomized condition and the geographic location of the homes of mentors and mentees, and only after that on shared interests. This could have diminished the positive effect of the mentoring program. More insight is needed on how matching mentors and mentees based on interest similarity may affect the success of mentoring.

Another limitation of the current study is the alpha level associated with the questions assessing satisfaction with social support. This means that conclusions made based on this outcome variable should be taken with caution. Future research is needed on further developing and validating this scale measuring satisfaction with social support among youth with a (visual) disability. Furthermore, due to time constrains it was not possible to conduct cultural validations of questionnaires used in this study. Also, for a large majority of the primary and secondary measures of this study information on their responsiveness to change was not available. This could have limited the possibility to detect change.

Implications for practice and research

The relationship between exposure to mentoring or the selection of mentors with disabilities as a method to establish changes in social participation might be more complex than originally expected. Future research is needed to explore what roles “peers” from the same underrepresented group can play within mentoring programs aiming to improve social participation. Recent research has shown that the roles played by mentors are an important element to the success of mentoring relationships and mentoring programs [Citation36,Citation73]. More insight is needed in how the inclusion of mentors with disabilities should be established such that a significant positive change above and beyond the previously established positive effect of mentoring programs is created. This insight could provide tools also for other programs or interventions including people with disabilities within their curriculum. Assessing what kind of role mentors with visual impairments played within the current study and how mentees perceived these actions may help better understand the effect of including mentors with disabilities in a mentoring program. This could provide insight in how to train and support them to become maximally effective.

Also, a comparison should be made between the efficacy of mentoring programs for people with disabilities implemented in a community-based setting or provided by a more structured setting such as within a rehabilitation and (special) education centers. By implementing a mentoring program within already exiting support provided by these centers, mentoring can be facilitated as an additional program. This might enhance the commitment to the mentoring program since the content and activities performed during the match meetings can be based on preexisting social participation rehabilitation goals established during intake interviews within the center. This could provide a more clear rationale to participants and mentors on how mentoring can be effective in the enhancement of social participation.

Earlier research has shown that especially deep-level similarities, based on at shared values, interests, or beliefs, facilitate positive effects of mentoring [Citation37]. More research is needed in how to operationally define and measure deep-level similarities, and to empirically examine this hypothesis for mentoring of youth with a visual impairment.

Mentoring in general has been associated with benefits for many youth outcomes. The DuBois et al. [Citation26] meta-analysis showed that mentoring also enhances psychological, emotional, and motivational outcomes. An important direction for future research is to obtain a more comprehensive picture of the effectiveness of the mentoring program of this current study on a wider range of theoretically based youth outcomes.

Furthermore, more effort should be made to study the effect of mentoring programs in multiple countries, because the effect of mentoring is mostly studied in the USA. Earlier research showed that the effect size of evidence-based psychotherapy vs. care-as-usual decreased when interventions, demonstrated to be effective in North America, were tested in other countries [Citation74]. As high levels of basic social care are provided in the Netherlands, due to the social security system, citizens might be less active and responsible for helping others and interventions aiming to support at risk groups could be perceived as less urgently needed, compared to countries with lower levels of basic social care. Future research should identify if specific factors of mentoring programs outperform common forms of care-as-usual in countries and cultures where this type of intervention is embedded.

Conclusions

Based upon the findings from the current study, it can be concluded that exposure to a community-based mentoring program does not outperform care-as-usual on improving the social participation of Dutch youth with a visual impairment. It remains possible that mentor-effects are enhanced when mentors and mentees share the same disability. This study shows that more research is needed on the efficacy of mentoring programs for youth with disabilities. Relevant to the debate about selecting mentors with disabilities as mentors for other people with disabilities, our finding suggest that benefits are primarily in the realm of perceived social support.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the two national Dutch rehabilitation centers (Bartimeus and Royal Dutch Visio) for supporting us with the recruitment of participants. In addition, we would like to thank our research assistants for assisting with the data collection. This trial is registered in the Netherlands Trial Register NTR4768 (registered 4 September 2014). The study protocol has been published in Trials [Citation45].

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jaarsma EA, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB. Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: a systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24:871–881.

- Shields N, King M, Corbett M, et al. Is participation among children with intellectual disabilities in outside school activities similar to their typically developing peers? A systematic review. Dev Neurorehabil. 2014;17:64–71.

- Shikako-Thoma K, Majnemer A, Law M, et al. Determinants of participation in leisure activities of children and youth with cerebral palsy: systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2008;28:155–169.

- Elsman EBM, Van Rens G, Van Nispen R. Impact of visual impairment on the lives of young adults in the Netherlands: a concept-mapping approach. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:2607–2618.

- Gold D, Shaw A, Wolffe K. The social lives of Canadian youths with visual impairments. J Vis Impair Blind. 2010;104:431–443.

- Greguol M, Gobbi E, Carraro A. Physical activity practice among children and adolescents with visual impairment – influence of parental support and perceived barriers. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37:327–330.

- Kef S. The personal networks and social supports of blind and visually impaired adolescents. J Vis Impair Blind. 1997;91:236–244.

- Kef S, Bos H. Is love blind? Sexual behavior and psychological adjustment of adolescents with blindness. Sex Disabil. 2006;24:89–100.

- Kef S, Hox JJ, Habekothe HT. Social networks of visually impaired and blind adolescents. Structure and effect on well-being. Soc Netw. 2000;22:73–91.

- McDonnall MC. The employment and postsecondary educational status of transition-age youths with visual impairments. J Vis Impair Blind. 2010;104:298–303.

- Salminen AL, Karhula ME. Young persons with visual impairment: challenges of participation. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21:267–276.

- Pinquart M, Pfeiffer JP. Perceived social support in adolescents with and without visual impairment. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:4125–4133.

- Larson RW, Verma S. How children and adolescents spend time across the world: work, play, and developmental opportunities. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:701–736.

- Law M. Participation in the occupations of everyday life. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56:640–649.

- Schulenberg JE, Bryant AL, O’Malley PM. Taking hold of some kind of life: how developmental tasks relate to trajectories of well-being during the transition to adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:1119–1140.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Adair B, Ullenhag A, Keen D, et al. The effect of interventions aimed at improving participation outcomes for children with disabilities: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57:1093–1104.

- Granlund M. Participation—challenges in conceptualization, measurement and intervention. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39:470–473.

- Piskur B, Daniëls R, Jongmans JJ, et al. Participation and social participation: are they distinct concepts? Clin Rehabil. 2014;28:211–220.

- Koster M, Nakken H, Pijl SJ, et al. Being part of the peer group: a literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. Int J Inclusive Educ. 2009;13:117–140.

- Imms C, Adair B, Keen D, et al. 'Participation': a systematic review of language, definitions, and constructs used in intervention research with children with disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:29–38.

- Wright F, Rosenbaum PL, Goldsmith CH, et al. How do changes in body functions and structures, activity, and participation relate in children with cerebral palsy? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:283–289.

- Gabel S, Peters S. Presage of a paradigm shift? Beyond the social model of disability toward resistance theories of disability. Disabil Soc. 2004;19:585–600.

- Nilholm C. Special education, inclusion and democracy. Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2006;21:431–445.

- Göransson K, Nilholm C. Conceptual diversities and empirical shortcomings–a critical analysis of research on inclusive education. Eur J Spec Needs Educ. 2014;29:265–228.

- DuBois DL, Portillo N, Rhodes JE, et al. How effective are mentoring programs for youth? A systematic assessment of the evidence. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2011;12:57–91.

- Rhodes JE, Spencer R, Keller TE, et al. A model for the influence of mentoring relationships on youth development. J Commun Psychol. 2006;34:691–707.

- Karcher MJ, Kuperminc GP, Portwood SG, et al. Mentoring programs: a framework to inform program development, research, and evaluation. J Commun Psychol. 2006;34:709–725.

- DuBios DL, Holloway BE, Valentine JC, et al. Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: a meta-analytic review. Am J Commun Psychol. 2002;30:157–197.

- DuBois DL, Silverthorn N. Natural mentoring relationships and adolescent health: evidence form a national study. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:518–524.

- Geenen S, Powers LE, Powers J, et al. Experimental study of a self-determination intervention for youth in foster care. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 2013;36:84–95.

- Chan CS, Rhodes JE, Howard WJ, et al. Pathways of influence in school-based mentoring: the mediating role of parent and teacher relationships. J Sch Psychol. 2013;51:129–142.

- Karcher MJ. The study of mentoring in the learning environment (SMILE): a randomized evaluation of the effectiveness of school-based mentoring. Prev Sci. 2008;9:99–113.

- Garringer M, Kupersmidt JB, Rhodes JE, et al. Elements of effective practice for mentoring. Boston: MENTOR: The National Mentoring Partnership; 2015.

- Grossman JB, Rhodes JE. The test of time: predictors and effects of duration in youth mentoring relationships. Am J Commun Psychol. 2002;30:199–206.

- Kupersmidt JB, Stump KN, Stelter RL, et al. Predictors of premature match closure in youth mentoring relationships. Am J Commun Psychol. 2017;59:25–35.

- Eby LT, Allen TD, Hoffman BJ, et al. An interdisciplinary meta-analysis of the potential antecedents, correlates, and consequences of protégé perceptions of mentoring. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:441–476.

- Rhodes JE. Stand by me: risks and rewards in youth mentoring. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 2002.

- Britner PA, Balcazar FE, Blechman EA, et al. Mentoring special youth populations. J Commun Psychol. 2006;34:747–763.

- Lindsay SR, Hartman L, Fellin M. A systematic review of mentorship programs to facilitate transition to post-secondary education and employment for youth and young adults with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:1329–1349.

- Maslow GR, Chung RJ. Systematic review of positive youth development programs for adolescents with chronic illness. Pediatrics. 2016;131:1605–1618.

- McDonald KE, Balcazar FE, Keys CB. Youth with disabilities. In: DuBois L, Karcher MJ, editors. Handbook of youth mentoring. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications; 2005.

- Shpigelman CN, Weiss PL, Reiter S. E-mentoring for all. Comput Hum Behav. 2009;25:919–928.

- Bell EC. Mentoring transition-age youth with blindness. J Spec Educ. 2012;46:170–179.

- O'Mally J, Antonelli K. The effect of career mentoring on employment outcomes for college students who are legally blind. J Vis Impair Blind. 2016;110:295–307.

- Sowers JA, Powers L, Schmidt J, et al. A randomized trial of a science, technology, engineering, and mathematics mentoring program. Career Dev Transit Except Individ. 2017;40:196–204.

- Heppe ECM, Kef S, Schuengel C. Testing the effectiveness of a mentoring intervention to improve social participation of adolescents with visual impairments: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:506–517.

- Heppe ECM, Kupersmidt JB, Kef S, et al. Does having a similar disability matter for match outcomes? A randomized study of matching mentors and mentees by visual impairment. J Commun Psychol. 2018;47:1–17.

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:726–732.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191.

- MENTOR/National mentoring Partnership. How to build a successful mentoring program using the elements of effective practice: a step-by-step toolkit for program managers. Alexandria (VA): MENTOR; 2005.

- MENTOR/National Mentoring Partnership. Elements of effective practice for mentoring. 3rd ed. Alexandria (VA): MENTOR; 2009.

- Looijestijn PL. Visuele activiteiten en participatie [Visual activity and participation]. Huizen, The Netherlands: Royal Dutch Visio; 2007.

- Kandel D, Davies M. Epidemiology of depressive mood in adolescents: an empirical study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:1205–1212.

- Tracy EM, Whittaker JK. The Social Network Map: assessing social support in clinical practice. Fam Soc. 1990;71:461–470.

- Meeus W. Ouders en leeftijdsgenoten in het persoonlijke netwerk van jongeren [Parents and peers within the social network of adolescents]. Pedagogisch Tijdschrift. 1990;15:25–37.

- Helsen M, Vollebergh W, Meeus W. Social support from parents and friends and emotional problem in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2000;29:319–335.

- Frison E, Eggermont S. The impact of daily stress on adolescents’ depressed mood: the role of social support seeking through Facebook. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;44:315–325.

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, et al. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Personal Assessment. 1988;52:30–41.

- Peugh JL. A practical guide to multilevel modeling. J Sch Psychol. 2010;48:85–112.

- Armstrong RA. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthal Physiol Opt. 2014;34:502–508.

- Davidson L, Chinman M, Sells D, et al. Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: a report from the field. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:443–450.

- Lockwood P. “Someone like me can be successful”: do college students need same-gender role models? Psychol Women Quart. 2006;30:36–46.

- Verhaeghe M, Bracke P, Bruynooghe K. Stigmatization and self-esteem of persons in recovery from mental illness: the role of peer support. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54:206–218.

- Black MM, Bentley ME, Papas MA, et al. Delaying second births among adolescent mothers: a randomized, controlled trial of a home-based mentoring program. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1087–1099.

- Wyman PA, Cross W, Brown CH, et al. Intervention to strengthen emotional self-regulation in children with emerging mental health problems: proximal impact on school behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:707–707.

- George CL, Oriel KN, Blatt PJ, et al. Impact of a community-based exercise program on children and adolescents with disabilities. J Allied Health. 2011;40:55–60.

- Hillier S, McIntyre A, Plummer L. Aquatic physical therapy for children with developmental coordination disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2010;30:111–124.

- Sakzewski L, Ziviani J, Abbott DF, et al. Participation outcomes in a randomized trial of 2 models of upper-limb rehabilitation for children with congenital hemiplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:531–539.

- Grossman JB, Chan CS, Schwartz SE, et al. The test of time in school-based mentoring: the role of relationship duration and re-matching on academic outcomes. Am J Commun Psychol. 2012;49:43–54.

- Fayter D, Mcdaid C, Ritchie G, et al. Systematic review of barriers, modifiers and benefits involved in participation in cancer clinical trials. York, UK: University of York; 2006.

- Spencer R. “It’s not what I expected”. A qualitative study of youth mentoring relationship failures. J Adolesc Res. 2007;22:331–354.

- Pryce J. Mentor attunement: an approach to successful school-based mentoring relationships. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2012;29:285–305.

- Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Eckshtain D, et al. Performance of evidence-based youth psychotherapies compared with usual clinical care: a multilevel meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:750–761.