Abstract

Purpose

To explore whether the personal assistance (PA) activities provided by the Swedish Act concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairment in 2010 and 2015 promote participation in society according to Article 19 of the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

Methods

Register data and data from two questionnaires were used (N = 2565). Descriptive statistics and chi-square (McNemar’s test) were used to describe the basic features of the data. Mixed binominal logistic regression was used to examine correlation between gender and hours of PA between 2010 and 2015.

Results

Despite an increase in the number of PA hours, more care activities and a reduction of most PA activities representing an active life were found. The result was especially evident for women, older people, and for a particular person category.

Conclusions

The results offer evidence of a shift to a medical model and indicate a risk of social exclusion due to fewer activities representing an active life. An increase on average of 16 h of PA over the period studied does not guarantee access to an active life and may indicate a marginal utility. The noted decline of PA for participation in society enhances the importance of monitoring content aspects to fulfil Article 19 of the UNCRPD.

Personal assistance (PA) in Sweden is a supportive measure for persons with disabilities; however, there are few studies to show whether PA activities are fulfilling disability rights of participation in society.

The results show that PA activities are used more for medical care and home-based services over the five-year period.

The study highlights the importance of monitoring aspects of content to ensure that the activities of PA comply with the policy objectives of the LSS legislation and Article 19 of the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), i.e., full participation in society. Monitoring efforts should include individualised planning and follow-up, moreover, ensure compliance with social service capacity at PA providers.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Introduction

Personal assistance (PA), as stated in Article 19 of the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD), is a supportive measure that aims to increase participation in society among persons with disabilities [Citation1]. The pillar of PA is that the user can perform any activities with the support of an assistant in order to live an independent life like others, thus eliminating limitations to participation in society. The strongest expression of Swedish policy towards fulfilling Article 19 by PA is regulated in The Swedish Act concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairment, the so-called LSS Act [Citation2].

Swedish studies indicate an incomplete and uneven implementation nationwide, thus compromising the rule of law [Citation3–5]. Over time an increased PA cost beyond the government’s original expectation of 4 billion Swedish kroner to 24.1 billion in 2019 has also been shown [Citation6]. The number of recipients of PA has increased from 6141 (1994) to 14 159 persons (2019) and granted hours of PA have increased from 66.9 in 1994 on average to 128.9 h per week and person in 2019 [Citation7]. Still, the knowledge as to whether the intention of the LSS Act, i.e., participation in society has been met, is limited. A cross-sectional study of the distribution of PA activities showed unequal access to participation across user groups and moreover illustrated that reported activities were predominantly of a caring nature [Citation8]. However, there are no longitudinal studies that show changes in PA activities over time.

The aim of this study was therefore to explore whether the PA activities, provided by the Swedish LSS Act in 2010 and 2015, promote participation in society according to Article 19 of the UNCRPD.

The LSS Act and personal assistance

Users of PA in Sweden represent a wide range of impairments and diversity of needs. PA can be granted from birth up to the age of 65 to persons who belong to one of three eligible person categories: (1) persons with intellectual disabilities, autism, or pervasive developmental disorders; (2) persons with severe disabilities following brain damage in adulthood, caused by external violence or physical illness; and (3) persons with other permanent physical or mental disabilities that are clearly not due to normal aging and cause significant difficulty in daily life, hence providing the extensive need for support and services [Citation2]. Those categories are henceforth referred to as “intellectual disability”, “physical disability”, and “special needs”. Persons eligible for PA are categorised according to their main diagnosis or by special needs; thus, the three categories are not mutually exclusive as to the presence and extent of multiple disabilities.

PA is provided for basic and additional needs. Basic needs are defined in the LSS Act as personal hygiene, meals, getting dressed/undressed, communication, and supervision [Citation2]. Additional needs may, for example, be support for work, studies, or to pursue leisure time activities. The administration of PA is a shared responsibility between governmental authorities. While local authorities remain the principal resources for implementing the LSS Act, the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA) manages the decision-making process of granting the so-called assistance allowance to cover costs for PA in cases when basic needs exceed 20 h per week.

In this study, “participation in society” is defined according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), as “a person’s involvement in a life situation” with respect to the ICF domains: domestic life, interpersonal interactions and relationships, major life areas and community, and social and civic life [Citation9]. Activities belonging to these domains of participation were chosen to reflect Article 19 of the UNCRPD, operationalised in the Swedish context by the intentions in the LSS Act, i.e., full participation in society. In the present study, a PA activity is defined as, for example, “hygiene”, “hobby”, or “work”.

Materials and methods

Design

This was a longitudinal study over a five-year period from 2010 to 2015. Data used in this paper were register data retrieved from the SSIA and data from questionnaires sent to users of PA, 16–84 years of age, who were granted an assistance allowance in 2010 and 2015.

Population

According to SSIA registry data, there were 15 289 persons entitled and granted assistance allowance to be used for PA in November 2010, of which 47% were women and 53% were men, and they were granted on average 112 h per week [Citation7]. By December 2015, there were 16 142 persons entitled to an assistance allowance (46% women and 54% men), all of whom were granted an average of 127 h per week [Citation7].

Procedure

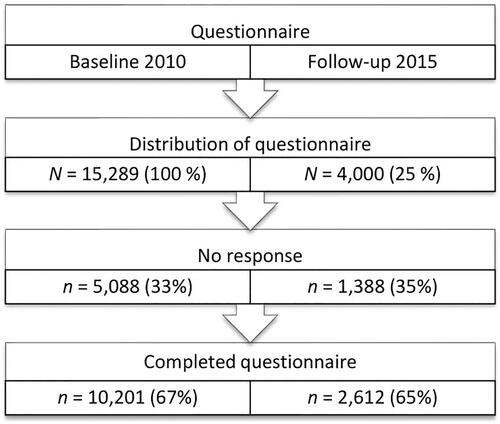

A questionnaire was sent out by SSIA to all 15 115 persons granted an assistance allowance in 2010 with the purpose of creating a baseline [Citation10]. No incentives or remunerations were offered. Two reminders were sent out and the response rate of the baseline questionnaire was 67% (). The non-response analysis showed that the non-responders differed from responders by a lower response rate among younger ages and within certain counties [Citation10]. A follow-up questionnaire was sent out by SSIA in May 2015 and was completed by September 2015. A sample of 4000 persons was drawn by SSIA from the 10 201 persons who responded to the baseline questionnaire in 2010. Deceased persons and persons under the age of 16 were excluded, corresponding to 30% of the respondents in 2010. The sample was stratified by age (≥16 years) and randomly sampled by age, gender, and eligible person categories. The response rate of the 2015 follow-up questionnaire was 65%. A flowchart of data collection in 2010 and 2015 is shown in .

Figure 1. Flowchart of the response rate of baseline and follow-up questionnaire aimed at persons granted assistance allowance.

The 2015 non-response analysis showed that the youngest and the oldest age groups had answered the questionnaire to a lesser extent than the age groups in between. The eligible person category “special needs” accounted for 50% of the non-respondents.

Questionnaires

The purpose of the questionnaires was to collect information on PA; this is the only longitudinal data collection of persons granted an assistance allowance that covers reported PA activities. The relevance and comprehensibility of the questionnaires was examined by two panels of users of PA. The 2010 questionnaire consisted of questions on living arrangements, disability and diagnosis, contacts with SSIA, satisfaction with granted hours for PA, assistance providers, and assistants. The question “Do you receive assistance for …”, contained 22 fixed response alternatives of items. These outline activities for which PA is used. The activities cover needs related to health and care, including the five basic needs defined by the LSS Act, along with further additional needs, i.e., household chores, errands, leisure, social interaction, and daily occupation. Three response formats were offered: a paper questionnaire, a web-based questionnaire, and a telephone interview. It was also possible to answer the questionnaire with the help of or by a proxy with personal knowledge about the respondent. The four possible response alternatives for the 22 items were as follows: not relevant; no, but would wish; yes, sometimes; and yes, regularly.

The 2015 questionnaire included the same 22 items as on the questionnaire distributed in 2010, outlining activities for which PA can be used. A sample of 2565 persons was drawn from the respondents of the 2015 questionnaire that had responded to the question “Do you receive assistance for…”. The same response formats as those of the 2010 questionnaire were offered. Registry data of the population of 2010, 2015, and the questionnaire sample, respectively, are shown in .

Table 1. Registry data categories and variables showed for respondents in 2010, 2015 and sample.

The respondents had a mean of 112 h per week in 2010 and 128 h of PA per week in 2015 (range: 20–339 h). Sixty-nine percent of respondents had answered the questionnaires themselves. In addition, registry data on age, gender, eligible person categories, and hours of assistance allowance, henceforth referred to as PA hours, from December 2015 were obtained from the SSIA.

Data analysis and statistics

The variables used in the analyses were the 2010 and 2015 answers to the question “Do you receive assistance for…”, i.e., the 22 items outlining activities for which PA can be used. The answers were coded as “no” if the response was “not relevant” or “no, but would like to have”, and “yes” if “yes, sometimes” or “yes, regularly”. The proportion of yes responses depended on whether missing values were removed or treated as “no” answers. A “no” answer was imputed as “no” since the difference, to otherwise remove the answer, was generally small (<0.1). The item “Do you have assistance for anything else requiring specific knowledge of you?” yielded a low endorsement rate and was dismissed from the analyses. The remaining 21 items were sorted into seven categories outlined in : “health and care”, “home”, “private economy”, “leisure”, “social interaction”, “daily occupation”, and “moving”. The 21 items were merged with registry data from the SSIA: gender (men and women); age (≥16 years); hours (20–339); and eligible person categories classified as “intellectual disability”, “physical disability”, and “special needs”. Number of PA hours granted for 2010 and 2015 were sorted into three categories, i.e., “increase” was defined by ≥8 h per week (n = 905), “reduction” was defined by ≥8 h per week (n = 194), and “no change” was defined by an increase or reduction of ≤7 h per week (n = 1511). The definition was set to correspond to less than one day's work for one assistant, thus representing a limit for employment and an interface between minor and major changes in PA. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) [Citation11].

Table 2. PA categories and activities for 2015 for total population and difference in proportion of items between 2010 and 2015 showing percent and p value (n = 2565).

Table 3. Share of PA categories and activities for 2015 for increased (n = 905), no change (n = 1511), or reduced (n = 194) hours of assistance allowance and difference in share of items between 2010 and 2015, showing percent and p value (n = 2565).

Table 4. PA categories and activities 2015 for age groups < 30 years (n = 749), 30–50 years (n = 668), >50 years (n = 1238), and difference in proportions of items between 2010 and 2015, showing percent and p value (n = 2565).

Table 5. PA categories and activities for 2015 for eligible person categories, intellectual (n = 942), physical (n = 138), special needs (n = 1456), and difference in proportion of items between 2010 and 2015, showing percent and p value (n = 2565).

Table 6. PA categories and activities for 2015 for men and women and difference in proportion of items between 2010 and 2015, showing percent and p value (n = 2565).

Table 7. Binomial mixed model showing PA categories, activities, and proportions of items across time 2010–2015, gender 2015 and interaction over gender and hours 2010–2015.

Descriptive statistics and chi-square (McNemar’s test) were used to describe the basic features of the data. Mixed binominal logistic regression was used to examine correlation of gender and hours of PA between 2010 and 2015. The study was approved by the Swedish Regional Ethical Review Board (Dnr 2012/1822-31/5).

Results

The number of granted hours for PA activities was 112 h per week 2010 and 128 h per week 2015, representing an increase of 16 h per week. Over the five-year period, significantly more individuals received an increased amount of activities. The results revealed a significant increase in 10 PA activities and a reduction in four PA activities (). One major increase (67.9%) in PA was found for help with private economy: “errands”, such as handling bank or post matters and making purchases.

The change in distribution of granted PA hours across individuals 2010–2015

Changes in PA hours have been studied in two ways: first, they have been studied over time, i.e., changes in hours (2010–2015), divided by groups: “increase”, “no change”, and “reduction”; and second, by the pattern of changes in PA activities during the same five-year period.

As shown in , all the groups reported significantly more PA for private economy: “errands” and less PA for social interaction: “family” and daily occupation: “study”. There were also changes within the groups over time. The “increase” group reported significantly more PA activities in all for nine items, in particular for health and care: “supervision”, private economy: “finance”, and home: “chores”. Significantly less PA was reported for leisure: “play”, social interaction: “family”, and daily occupation: “study”. The group “no change” reported significantly more PA activities for eight items in all. More PA was reported for five activities in health and care as well as for home: “chores” besides private economy: “errands”. Significantly fewer instances of PA were reported for leisure: “play” and “hobby”. Significant changes in the third group “reduction” were common within all groups.

Differences across age and eligible person categories

The distribution of activities for 2015 across age groups showed distinctive features (see ). In health and care, “hygiene”, “meals”, and “dressing” were reported for over 95% of the users across age groups. Additionally, PA for health and care: “medication”, leisure: “stroll and shop”, and moving: “moving outdoors” showed a similar distribution across age groups. Common to all age groups () was a significant increase in PA for health and care: “supervision” and for private economy: “errands”, while for social interaction: “family” and Daily occupation: “study” in particular, it was reduced.

The youngest age group showed an increase in home: “chores”, private economy: “finances”, and daily occupation: “work”, and a reduction in leisure: “play”. Moreover, for the middle-aged group, a significant increase was found for health and care: “hygiene”, “meals”, “dressing”, and “medication”, as well as an increase in home: “chores”. The oldest age group revealed an increase in health and care: “dressing”. Further, a reduction in activities for the oldest age group was found for leisure: “hobby” and “play” and for daily occupation: “work”.

The results also revealed a significant increase as well as a reduction in PA across eligible person categories, i.e., “intellectual disability”, “physical disability”, and “special needs” between 2010 and 2015, as shown in .

Common to all categories of people was an increase in PA for private economy: “errands”. Persons in the category “intellectual disability” reported an increase in nine PA items and a decrease in three. In particular, an increase was reported for health and care: “hygiene”, “meals”, and “supervision”, for home: “chores” and “maintenance”, for private economy: “finance”, for social interaction: “socialise”, and for daily occupation: “work”. Correspondingly, significantly less PA was reported for three items, i.e., leisure: “play”, social interaction: “family”, and daily occupation: “study”.

The person category “physical disability” showed a reduction in leisure: “hobby”. Persons in the category “special needs” reported significantly more PA for health and care: “hygiene”, “meals”, “dressing”, “supervision”, and “medication”, as well as for home: “chores”. Significantly less PA was reported for leisure: “play” and “hobby” and for social interaction: “family” and daily occupation: “study”.

Change in distribution of PA activities across gender

The changes in PA activities between 2010 and 2015 across gender revealed statistically significant changes ().

Women reported significantly more PA activities for health and care: “dressing” and for moving: “moving outdoors” than men, while men reported more PA for health and care: “medication” and private economy: “finances”, such as PA for paying bills but less for leisure: “hobby” activities.

The results of a binominal mixed model () showed significant differences over the five-year period, across PA hours and gender, and an interaction effect of PA hours and gender.

The results revealed a significant increase in hours for nine PA activities, i.e., health and care: “hygiene”, “meals”, “dressing”, “supervision”, “medication”, home: “chores”; private economy: “errands”, “finance”, and daily occupation: “work”. During the course of the five-year period, a reduction was found in leisure: “play”, “hobby”, social interaction: “family”, and daily occupation: “study”.

When comparing the distribution of PA items between men and women for 2015, the results showed that women reported less PA than men for health and care: “life support”, home: “maintenance”, and moving: “driving”. The interaction effect across gender revealed that men reported more PA for three items, i.e., health and care: “dressing”, home: “chores”, and social interaction: “socialise” ().

Discussion

The aim of the study was to explore whether the PA activities provided by the Swedish LSS Act in 2010 and 2015 promote participation in society according to Article 19 of the UNCRPD.

The results showed a reduction in most PA activities representing an active life, such as “study”, “family”, and “hobby”. Instead, PA has come to include more health and care activities over time and a transition to support the user in the home, rather than providing activities for participation in society. Thus, there is a shift to a medical model and a risk of social exclusion due to fewer activities outside the home.

Overall, more hours of PA were provided in 2015 compared to 2010. All groups demonstrated a high prevalence of health and care, in particular “hygiene”, “meals”, and “dressing”. The distribution of activities had changed to a small extent for the group with reduced PA (equivalent to one working day or more for an assistant). Among those for whom the number of PA hours had increased over the period, more individuals received PA for health and care: “supervision” (especially among women and older age groups), for social interaction: “socialise”, and for daily occupation: “work”. The results showed an interaction effect for gender, where men reported more PA hours for health and care: “dressing”, home: “chores”, and social interaction: “socialising” than women. Moreover, the proportion of PA activities were found to decrease with older ages, with the exception of PA activities performed within the home, primarily “chores”, and activities within health and care. How the results relate to the intentions of the LSS Act and to Article 19 of the UNCRPD will be discussed below.

The dominance of health and care prevails over time

The development of three out of five activities for basic needs defined by the LSS Act, i.e., “hygiene”, “meals”, and “dressing”, and to a lesser extent “medication”, stand out in the results by being consistently high over time. These activities had increased for most groups between 2010 and 2015. We can assume that a considerable proportion of PA would be provided for health and care activities since persons with severe disabilities are eligible according to the LSS Act. The result may reflect that PA, initially intended to support an active and independent life, has been changed to health and care activities due to progressive and care-intensive health and impairment conditions. However, details of individual health and impairment conditions were not available.

The results of this study showed that the relationship between users of PA and their assistants in practice resembles a care relationship. In particular, the health and care activity “supervision” is a typical example of a care relationship. Several scholars within the field of disability studies view the caring activities as a contradiction to promote an independent life [Citation12–15]. It can be reasonably assumed that PA develops towards a care relationship, given extended exposure, mutual trust and experiences. Unfortunately, we have no data how consequences of comprehensive care efforts affect the achievement of the LSS goal, which is an important issue to highlight.

Supervising activities may be seen as contradictory to the intentions of Article 19 of the UNCRPD and the policy objectives of the LSS Act [Citation2]. It cannot be ruled out that precedential adjudgements may have contributed to a shift of eligible users with extensive needs [Citation8]. The development of healthcare-related items over time, particularly “supervision”, demonstrates a shift towards a medical reform and reveals that the implementation of the LSS's Act represents a sliding interface towards healthcare.

A transition to home-based PA

Like health and care, personal economy is presumably also mainly carried out in the home. Private economy: “errands”, i.e., PA for banking, post, and purchases showed the highest increase in PA over the five-year period, with an increase of 68% on average and across all groups. This result could be explained by the extensive development of information and communications technology services (ICT). Improved participation through digital accessibility for persons with disabilities in Sweden has been demonstrated [Citation16]. However, major variations in the ability to use ICT services, including e-commerce, to pay bills or make appointments at healthcare centres, were found, and a majority reported the need of assistance. The results showed that over 90% of persons in the oldest age group use PA for “errands”, in comparison to 50% usage of ICT reported by Swedes over 65 years of age [Citation16]. The findings indicate a rapid increase in ICT services and highlight the probable importance of PA for digital participation. This result marks however a likely increase in time spent presumably within the home due to ICT usage and is a development in line with the national population.

Another significant increase in PA was found for the category home: “chores”. “Chores” were found to be one of few items to increase with age, which may be explained by an impaired ability to carry out chores later in life [Citation17]. In the mixed regression model (), men were found to receive more PA for “chores” than women. This corresponds to studies showing that women with severe disabilities receive less home care than men, irrespective of them living alone or living with a partner [Citation8,Citation18]. Reasons for this are probably normative, i.e., men are perceived to need more support for household chores than women. This result indicates gender inequality among PA users.

The observed transition towards home-based PA can explain a change over the studied period by a change in mode of transport. The results showed a shift within the category moving with less “driving” and more “moving outdoors”, especially for women. This shift may indicate an increase in transport by travel services, which in comparison to access to one’s own form of transport, reduces freedom of movement for the individual. Mode of transport affects essential prerequisites for an active and independent life. Studies confirm that a lack of one’s own ability to drive impacts quality of life by way of higher risk of social exclusion [Citation19].

A decline in PA for an active life by social interaction and daily occupation

In spite of significant resources being added by increased hours of PA, corresponding to an average of 16 h per week over the time period, categories representing an active life, that may take place by ICT services or activities outside the home were for the most part reduced.

A shift was found in the category social interaction. While an increase in “socialise” was found for the category intellectual disability and also for women when compared to men, a reduction across all groups was found for “family”. The drastic reduction of “family” can be explained by a reduced attendance over time by family members, especially parents, who work to provide PA to their adult child. PA by family members, as a guarantee of continuity and a social support platform, has been argued as superior to PA provided via the municipality or other external providers. Whether family members’ presence as assistants stands in conflict with the user’s pursuit of self-determination, or even involves risks of social as well as economic lock-in effects on both parts, has, however, been under debate [Citation20,Citation21]. By living close or having a close connection to family, the user of PA may have the advantage of being included in activities and a social life provided by and also for other family members. Thus, there are challenges to arranging other sources of support to replace PA offered by family members. This is inevitable since PA, particularly by ageing parents, phases out over time [Citation13,Citation22].

A reduction in leisure was also found. Not only do leisure activities contribute to well-being, but they are also important for creating social relationships outside the family. The results could indicate that a social lock-in effect, expressed by a reduction of PA for “family”, and also for leisure, occurs over time due to a decrease in PA partly provided by family members. Since non-work rather than paid employment is the norm for persons with disabilities, leisure takes on great significance for a meaningful existence and plays a vital role in habilitation or rehabilitation processes [Citation2,Citation23,Citation24]. It can, however, not be ruled out that the result was due to impaired abilities associated with ageing and disability.

Daily occupation was found to have changed significantly by an overall reduction. An exception was found for “work”, which had increased for the person category “intellectual disability” and for the youngest age group. The result can be explained by the right stated in the LSS Act that gives persons with intellectual disabilities access to daily activities. In all, the result of daily occupation raises awareness of the social and financial exclusions of persons eligible for PA, which is in line with studies showing a significantly lower employment rate for persons with disabilities [Citation25,26].

Methodological limitations

The empirical material offers a comprehensive picture of the content of PA and the development over time for users granted an assistance allowance. Thirty-one percent had answered the questionnaire with the support of a proxy, which presents the risk that the answers do not fully represent the views of the user. There are, however, few options to capture a heterogeneous population in which a portion of the respondents have a limited ability to communicate without the assistance of another person. Since the questionnaires did not include items covering the subjective experience of participation or another form of personal views in relation to the activities, the proxy respondents were expected to be less sensitive to bias. The construction of the questionnaire was based on two panels of users of PA, but it cannot be ruled out that other panels would have deduced other items. Completed questionnaires corresponded to 65% of the population. Despite a large proportion of non-respondents, the results are based on 2565 answers, which must be considered useful.

Policy implications and future research

Article 19 of the UNCRPD recognises disability rights by stating that measures should promote full participation in society. These intentions are reflected in the LSS Act. However, the findings indicate that PA in this study bears the characteristics of a health and care relationship, thus demonstrating that the intention of the Act is at risk of being gradually undermined. The increase in PA activities private economy: “errands” suggests improved participation by digital access. However, the reporting of deteriorating access to community life as well as for social and family activities is a testament to the risk of social exclusion; thus, an increase on average of 16 h of PA over the period studied does not guarantee access to an active life. The results showed virtually a similar pattern for all groups – increase, unchanged, and reduction. This indicates that the hours of PA have marginal utility since even the reduction of hours studied does not imply a decisive difference for participation in society. Thus, the importance of monitoring the content of PA is central to achieving the intention of participation set out in the LSS Act. This monitoring may be a joint effort between the SSIA and the municipality. In order to enhance participation according to the LSS, monitoring should include individualised planning and follow-up as well as users’ perspective, but also aimed towards providers of PA, to ensure available social service capacity and competence.

The results give reason to study further the policy implications of the LSS Act. The results highlight the importance of identifying key factors in the implementation process of granting an assistance allowance, which can explain why and how the observed transformation of the LSS reform, i.e., from citizenship-oriented rhetoric to a model of care, has evolved. It is also important to complement this study with interviews of persons granted an assistance allowance to explore the subjective experience of PA.

Conclusions

Overall, the results reveal that an increase in hours of PA, on average 16 h per week, does not promote participation in society outside the home, which may indicate its marginal utility. The results suggest that PA bears the characteristics of a health and care relationship, in particular via the increasing provision of supervision. Moreover, the results imply a transition to home-based PA over time. This finding is not equivalent to social isolation because the use of ICT services is part of a greater societal change. Nevertheless, the development of less interaction in society indicates a risk of social exclusion for the group studied due to fewer opportunities to perform activities that represent an active life. This is especially evident for women, older persons, and for the person category “special needs”. Taken together, the results illustrate the need to monitor aspects of PA content, directed towards individual and PA providers, to ensure improved participation in society as expressed by Article 19 of the UNCRPD.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the persons who completed the questionnaires. We also wish to give our sincere thanks to statistician and adjunct professor Johan Bring, and statistician Fabian Söderdahl for their advice and processing of data at Statisticon Statistics and Research, Uppsala, Sweden.

Disclosure statement

All authors affirm that they have no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- The UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Geneva: OHCHR; 2006.

- The Riksdag. Lag (1993:387) om stöd och service till vissa funktionshindrade [Act concerning support and service for persons with certain functional impairments]. Stockholm: Riksdagen; 1993. p. 387.

- The Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. Assistansersättning. Brister i lagstiftning och tillämpning [Assistance allowance. Flaws in law and practice]. Stockholm: Inspektionen för Socialförsäkringen; 2015.

- The Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Assistansersättningens utveckling [The development of assistance-allowance]. Stockholm: Försäkringskassan; 2017.

- Brennan C, Traustadottir R, Anderberg P, et al. Are cutbacks to personal assistance violating Sweden's obligation under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Laws. 2017;5:23.

- The Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Utgiftsprognos för budgetåren 2020–2023 [Expenditure forecast for the financial years 2020–2023]. Report for the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; 6 May. Stockholm: Försäkringskassan; 2020.

- The Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Statistics on assistance allowance; 2020 [cited 2020 May 8]. Available from: https://www.forsakringskassan.se/statistik/funktionsnedsattning/assistansersattning

- von Granitz H, Reine I, Sonnander K, et al. Do personal assistance activities promote participation for persons with disabilities in Sweden? Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(24):2512–2521.

- The World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- The Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Statlig personlig assistans – resultat från en undersökning av gruppen assistansberättigade [Government assistance allowance – results from a survey of eligible persons]. Stockholm: Försäkringskassan; 2011.

- IBM Corp. Released 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. New York: IBM Corp.; 2010.

- Morris J. Independent living and community care: a disempowering framework. Disabil Soc. 2004;19(5):427–442.

- Grossman B, Magana S. Introduction to the special issue: family support of persons with disabilities across the life course. J Fam Soc Work. 2016;19(4):237–251.

- Kroger T. Care research and disability studies: nothing in common? Crit Soc Policy. 2009;29(3):398–420.

- Kelly C. Making ‘care’ accessible: personal assistance for disabled people and the politics of language. Crit Soc Policy. 2011;31(4):562–582.

- Johansson S. Design for participation and inclusion will follow. Disabled people and the digital society. Stockholm: Royal Institute of Technology; 2019.

- Leino M, Tuominen S, Pirilä L, et al. Effects of rheumatoid arthritis on household chores and leisure-time activities. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(11):1881–1888.

- The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. Hälsa, Arbete och Kön – Vård på lika villkor? [Health, work and gender – care by same conditions?]. Stockholm: Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner; 2002.

- Davey JA. Older people and transport: coping without a car. Aging Soc. 2007;27(1):49–65.

- Olin E, Dunér A. A matter of love and labour? Parents working as personal assistants for their adult disabled children. Nord Soc Work Res. 2016;6(1):38–52.

- The Swedish Social Insurance Agency. Anhöriga som personliga assistenter. Stockholm: Försäkringskassan; 2018.

- Baumbusch J, Mayer S, Phinney A, et al. Aging together: caring relations in families of adults with intellectual disabilities. Gerontologist. 2017;57(2):341–347.

- Kitis A, Eraslan U, Koc V, et al. Investigation of disability level, leisure satisfaction, and quality of life in disabled employees. Soc Work Public Health. 2017;32(2):94–101.

- Aitchison C. From leisure and disability to disability leisure: developing data, definitions and discourses. Disabil Soc. 2003;18(7):955–969.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Sickness, disability and work: breaking the barriers. A synthesis of findings across OECD countries. Paris: OECD; 2010.

- The World Health Organization and the World Bank. World report on disability. Geneva: WHO; 2011.