Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate comprehensiveness and acceptability of the patient-reported outcome instrument (PRO-LBP) and the clinician-reported outcome instrument (ClinRO-LBP) included in the low back pain (LBP) assessment tool. Second, to assess degree of implementation after three months.

Methods

Feasibility-testing, training of health professionals, field-testing, and a feedback meeting was undertaken. Field-testing provided data to evaluate comprehensiveness, acceptability, and degree of implementation.

Results

Feasibility-testing and training of health professionals revealed that the LBP assessment tool was usable and ready for field-testing. In total, 152 patients participated in the field-testing of whom 95% considered the PRO-LBP comprehensive and 59% found it acceptable. Health professionals found the ClinRO-LBP comprehensive and acceptable. The feedback meeting revealed that the LBP assessment tool broadened the health professionals’ approach to functioning and facilitated a consultation based on the patient perspective. The degree of implementation reached 79%.

Conclusions

The PRO-LBP and the ClinRO-LBP covered key concepts of LBP and were found acceptable by patients and health professionals. Despite the reduced degree of implementation after three months the LBP assessment tool allowed the health professionals to apply a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach. Future research should investigate whether the LBP assessment can enhance patient-centred care.

The low back pain (LBP) assessment tool is the first evidence-based tangible tool to cover biopsychosocial aspects related to LBP as defined by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

The LBP assessment tool allowed health professionals to apply a biopsychosocial and patients-centred approach and has the potential to be used in rehabilitation planning.

Awareness to continuous facilitation and training of health professionals is important to facilitate and maintain implementation of new procedures into routine clinical practice.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a complex symptom [Citation1]. Consequently, a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach in assessment and management of patients with LBP are recommended [Citation2–4]. However, implementation of this approach into clinical practice is lacking [Citation5–7].

To promote a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach, obtaining the perspective of both patients and health professionals is necessary [Citation8]. The patient perspective is often assessed using patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments in addition to clinician-reported outcomes (ClinROs) [Citation9]. As PROs reflect the patient's perspective, they have the potential to play an important role in advancing patient-centred healthcare [Citation10], but they have found little direct use in consultations among patients with LBP [Citation11]. Commonly used LBP-specific PRO instruments have limitations [Citation12–15]. They lack items identified as being important to patients with LBP [Citation14] and they do not address environmental factors [Citation13,Citation15]. Therefore, it has been suggested to develop new LBP-specific PRO instruments [Citation14,Citation15].

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provide a biopsychosocial approach to assess functioning and disability [Citation16]. The importance of this approach has been widely recognised [Citation17], but its implementation into clinical practice remains sparse [Citation5,Citation18]. Therefore, user-friendly tools to enhance the use of ICF in clinical practice of LBP are needed [Citation8,Citation19].

We developed the LBP assessment tool to support a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach to obtain a complete and holistic assessment of the patient [Citation20,Citation21]. The tool was based on ICF core sets [Citation22,Citation23], and built on three features: a PRO instrument (PRO-LBP), a ClinRO instrument (ClinRO-LBP), and a graphical overview displaying the individual patient's functioning and disability (Patient-Profile-LBP). The development of the LBP assessment tool including aspects of content validity is described in a separate paper (part 1) [Citation21]. This current paper (part 2) aims to test the tool in a real-world setting in which it was intended to be used (“field-testing”) [Citation24].

Implementation of a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach including use of PROs is challenging [Citation25–27]. Adequate training and interdisciplinary assessment can enhance the integration of a biopsychosocial approach in patients with LBP [Citation28,Citation29]. Facilitators to implementation of PROs include training of health professionals, presentation of PRO data in an easy and clinically applicable format, and feedback meetings with health professionals [Citation30–32]. Furthermore, feasibility-testing is an important step in the development and implementation of PROs because it addresses issues of uncertainty before taking on a larger field-testing [Citation33,Citation34]. Implementation of evidence and new procedures into clinical practice is generally accepted to be challenging [Citation35,Citation36]. Therefore, implementation should be assisted by a framework to gain insight into the mechanisms by which implementation is more likely to succeed [Citation37].

The aim was (1) to evaluate comprehensiveness and acceptability of the PRO-LBP and the ClinRO-LBP and (2) to assess the degree of implementation of the LBP assessment tool after three months.

Materials and methods

This study was guided by the integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework [Citation38] in order to gain insight into elements of importance for implementation of the LBP assessment tool [Citation38]. In addition, feasibility-testing, training health professionals, field-testing, and a feedback meeting with health professionals were conducted.

The i-PARIHS framework

The main elements of the i-PARIHS framework are the context, the innovation, the recipients, and facilitation [Citation38].

The context in which the LBP assessment tool was to be used was a specialised spine centre, receiving approximately 12 000 patients with persistent LBP annually. Referral criterion was unsatisfactory improvement within 1–2 months of primary care treatment (general practitioner, physiotherapist, or chiropractors). A specialised multidisciplinary assessment of the patients is performed, followed by a plan for rehabilitation [Citation39]. Most patients are referred from the spine centre to outpatient rehabilitation programmes in the primary health sector.

The innovation including the content and evidence behind the LBP assessment tool is described elsewhere (part 1) [Citation21].

Recipients were patients referred to the spine centre and health professionals assessing the patients. Inclusion criteria for eligible patients were as follows: LBP with or without leg pain symptoms, age 18–60 years and ability to understand and speak Danish. Before the consultation, patients completed the PRO-LBP as part of a standard procedure. The PRO-LBP was designed to prepare the patients for the consultation by asking questions about how their daily life was affected by LBP. The health professionals included were medical doctors, physiotherapists, chiropractors, and nurses (n = 7). The team conducted a specialised multidisciplinary assessment to prescribe the optimal rehabilitation for the patients. The standard procedure was that patients underwent a primary assessment performed by a medical doctor, a chiropractor, or a physiotherapist. Relevant patients were offered an extended LBP assessment performed by a physiotherapist. All patients had a consultation with a nurse regarding medicine and everyday life. The health professionals used the Patient-Profile-LBP (data from the PRO-LBP) in preparation for the consultation to increase their attention to the patient's concerns. The ClinRO-LBP was completed during the clinical examination.

Facilitation is a key element to improve the degree of implementation in clinical practice [Citation38]. Evidence showed that guidelines are three times more likely to be implemented when a local facilitator is used [Citation40]. In this study, the facilitator role was assigned to a medical doctor and an experienced rheumatologist (BSC) who was also head of research at the spine centre. BSC acted as an internal facilitator skilled in working with patients with LBP, had knowledge of the ICF in clinical practice and insight into the LBP assessment tool. BSC had an exhaustive knowledge of the health professionals working at the spine centre and insight into organisational development.

Feasibility-testing

In collaboration with a physiotherapist from the team practical and technical issues was tested in clinical practice. Five patients were invited to participate. The first author observed the consultations taking field notes about technical production, structure, navigation, login, and graphical illustrations. The physiotherapist provided verbal feedback after each consultation. The field notes and feedback were documented and used for improvements.

Training health professionals

Seven health professionals were invited to participate in a training programme containing three components ().

The instruction was given by the two authors, CI and TM. It was centred around expanding the health professionals' knowledge about (1) the biopsychosocial ICF approach used as a framework in rehabilitation, (2) the evidence behind the LBP assessment tool, and (3) patient-centred care and active use and value of PRO assessment for individual patient care. The instruction was tailored to the context, and learning goals were created to describe the knowledge and skills to be achieved after the instruction ().

Table 1. Content areas in the instruction component, including form and learning goals.

The tryout component allowed health professionals to try out the LBP assessment tool before launching the field-testing [Citation37], by means of testing procedures and gain confidence in using the tool [Citation37]. The consultations were observed using a standardised observation form (Supplementary table S1). A follow-up meeting with the health professionals was conducted to discuss observations and experiences from the tryout component. Field notes were taken and used to improve the PRO-LBP, ClinRO-LBP, and Patient-Profile-LBP before the field-testing.

Field-testing

A sample of outpatients attending a project clinic situated at the Spine Centre were invited to the field-testing. The authors proposed a sample size of ≥100 patients in agreement with COSMIN recommendations [Citation41]. The overall field-testing lasted five-month, of which the first three is reported in this paper. Patients attending the project clinic during the time period were consecutively enrolled and assessed by the multidisciplinary team completing the training programme; field-testing followed the same procedure as feasibility-testing.

The field-testing provided data for evaluation of comprehensiveness, acceptability, and degree of implementation after three months. Comprehensiveness of the PRO-LBP and the ClinRO-LBP was evaluated on a Likert scale (1 = to a great degree to 5 = not at all). Other aspects of content validity ("relevance" and "comprehensibility") of the PRO-LBP and the ClinRO-LBP are described as part of the development of the tool [Citation21]. Comprehensiveness of the PRO-LBP was also assessed by reviewing the patients' narratives from the textbox to identify self-identified concerns missing in the PRO-LBP.

Acceptability was defined as "factors that affect the patients' and health professionals' willingness to use the tool" [Citation42], and was evaluated in terms of ease (1 = very easy to complete to 5 = very hard to complete), and completion time (minutes).

Degree of implementation after three months was assessed as presented in .

Table 2. Degree of implementation after three months including the nominated criterion value.

Responses from the patients regarding comprehensiveness and acceptability were collected simultaneously with the PRO-LBP (before the consultation), as one item regarding comprehensiveness and one item regarding ease were integrated into the PRO-LBP. A questionnaire survey among the health professional regarding comprehensiveness and acceptability of the ClinRO-LBP, the use of the PRO-LBP and the Patient-Profile-LBP during consultations was conducted after 10 months (Supplementary table S2). Items 1, 2, and 10 are reported in the present study. Completion time of the PRO-LBP and ClinRO was obtained directly by SurveyXact®. The patients responded to a follow-up questionnaire immediately after their consultation that assessed the use of their PRO responses from the PRO-LBP (item no. 1) and the use of the Patient-Profile-LBP (item no. 2) during the consultation. The questionnaire was sent using a secure online digital mailbox, and up to three reminders were given.

Feedback meeting with health professionals

To evaluate face validity and usability of the LBP assessment tool a feedback meeting was held with the health professionals after three months. Furthermore, the feedback meeting was held to enhance shared learning and implementation [Citation32,Citation45].

Before the meeting, the health professionals were asked to reflect on which modifications the LBP assessment tool had prompted regarding the assessment procedures and the multidisciplinary collaboration. Additionally, they should consider technical barriers when using the LBP assessment tool and identify essential missing information. The 90-min feedback meeting was recorded, and field notes were taken.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe patient characteristics, comprehensiveness, and acceptability of the PRO-LBP and the ClinRO-LBP and degree of implementation after three months. The Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was performed for categorical data, whereas t-test or Mann–Whitney's U test was conducted for continuous data. To analyse data regarding comprehensiveness extracted from the text box, the ICF linking rules were applied [Citation46]. The linking was carried out by two professionals trained in the ICF. A time-trend analysis was performed to identify potential change in time (months) regarding the use of the PRO-LBP and Patient-Profile-LBP. Additionally, a non-responder analysis was performed. The feedback meeting was analysed guided by interpretive description methodology [Citation47]. CI and TM independently reviewed the recording twice, compared with the field notes and independently drafted themes, followed by discussions and agreement upon themes. Recording were re-examined and the themes were condensed. Finally, central topics were described and synthesised in collaboration with BSC.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (file no. 1-16-02-477-16). According to the Central Denmark Region Committees on Health Research Ethics, the study did not need any further approval (file no. 150/2016). A non-commercial research licence from World Health Organization was granted (LC/20/010). All patients and health professionals received oral and written information about the study, and written consent was obtained before participation.

Results

The i-PARISH framework

To improve the degree of implementation, we considered the context, the innovation, the recipients, and facilitation in accordance with the i-PARISH framework [Citation38]. The i-PARISH framework facilitated awareness to the critical elements connected to the implementation of the LBP assessment tool.

Feasibility-testing

Overall, the test of practical and technical issues progressed without complications. Minor adaptations of technical issues regarding logon and the visual presentation of data were made after the feasibility-testing.

Training health professionals

The instruction was conducted as planned. At the beginning of the day, the health professionals were introduced to the content areas and learning goals. At the end of the day, they were asked to reflect on the learning goals. The immediate evaluation was positive, and no further instruction seemed necessary to fulfil the learning goals.

The tryout revealed that the LBP assessment tool was applicable in clinical practice. The use of the PRO-LBP during the consultation varied a great deal among the health professionals. The field notes showed that some technical adaptations to the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP were necessary.

At the follow-up meeting, the health professionals stated that the ClinRO-LBP was easy and quick to fill in, but they missed information regarding body mass index, pain catastrophising, and fear of movement. They experienced that the PRO-LBP facilitated patient involvement. However, using patients' responses as the point of departure was difficult because most health professionals are used to “take a medical history” from the patient by asking the questions. Thus, more training was required, which is in accordance with the findings from the trout. Based on the results from the follow-up meeting, items regarding height and weight were added to the PRO-LBP, and pain catastrophising [Citation40] and fear of movement [Citation41] were added to the ClinRO-LBP. Overall, the health professionals accepted the LBP assessment tool and found it ready to be field-tested in a larger LBP population.

Field-testing

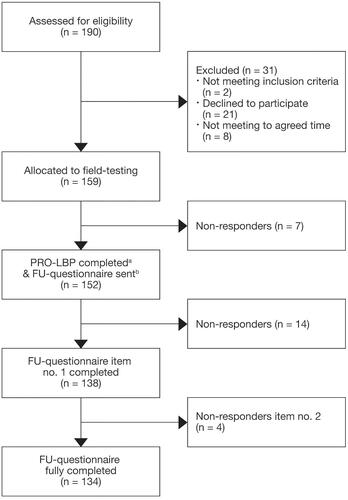

A sample of 159 patients with LBP with or without leg pain symptoms were included. Among these patients, 152 completed the PRO-LBP (96% response rate) and 134 completed the follow-up questionnaire (88% response rate) ().

Figure 2. Flowchart, patients in the field-testing. PRO-LBP: the ICF-based questionnaire patients complete before the consultation; FU-questionnaire: the follow-up-questionnaire patients completed after their consultation. aThe PRO-LBP comprised two additional items regarding ease and comprehensiveness. bThe follow-up questionnaire comprised two items: one about the use of the PRO-LBP (item no. 1) and one about use of the Patient-Profile-LBP (item no. 2).

provides details on the sample of patients completing the PRO-LBP (n = 152).

Table 3. Demographic and clinical variables (n = 152).

The non-responder analysis (n = 25) showed that non-responders had a lower ODI score compared to responders. Moreover, responders were more often employed and had leg pain for more than three months. No statistically significant differences were found for the other demographic and clinical variables.

Seven health professionals participated in the field-testing (Supplementary table S3). Among them (physiotherapists, medical doctors, and a chiropractor), five performed the primary assessment of the patients using the ClinRO-LBP (n = 151). The nurses did not complete the ClinRO-LBP because they did not perform the primary assessment.

Comprehensiveness and acceptability of the PRO-LBP and the ClinRO-LBP

Among the 152 patients, 95% (95% CI: 90; 98) found the PRO-LBP comprehensive and 59% (95% CI: 50; 66) found it “very easy” or “easy” to complete. The mean completion time was 28 minutes. Fifty-five patients (35%) wrote self-identified concerns in the text box in the PRO-LBP. The ICF linking process identified 123 meaningful concepts successfully linked to 41 unique ICF categories; 95% were covered by the PRO-LBP and six additional ICF categories were identified, all mentioned once (). Notably, 33 out of the 55 patients elaborated on their pain (ICF category b280 sensation of pain) even though pain items were a significant part of the PRO-LBP.

Table 4. Additional ICF categories identified in the text box in the PRO-LBP (n = 55).

Five of the health professionals provided data regarding comprehensiveness and acceptability of the ClinRO-LBP. They all agreed on the comprehensiveness of the ClinRO-LBP and four out of the five found the ClinRO-LBP “very easy” or “easy” to complete. The mean completion time was two minutes.

Degree of implementation

In total, 79% of the patients reported that their responses from the PRO-LBP were used during the consultation (criterion value 85%), and 69% saw the Patient-Profile-LBP (criterion value 75%) (). The variation over time analysis showed that the use of PRO-LBP decreased during the three months, whereas the use of the Patient-Profile-LBP varied ().

Table 5. Degree of implementation, in total after three months and variation over time.

The health professional survey after 10 months showed that all seven health professionals used the PRO-LBP to some extent during the consultation. According to the health professionals, they all used the Patient-Profile-LBP.

Feedback meeting

Seven health professionals (Supplementary table S3) participated in the feedback meeting. Overall, they were satisfied with the LBP assessment tool and found it usable for routine clinical practice.

Three main topics were extracted from the feedback meeting. First, it facilitated a smooth and positive consultation based on the patient perspective because all patients were able to fill in the PRO-LBP and their answers were useful. One health professional said: “It was a pleasure to see how patients were able to fill in the PRO-LBP, their answers were useful, and the LBP assessment tool helped address what matters to the patients” (ID 2). Second, the LBP assessment tool allowed for a more biopsychosocial approach to functioning and disability, including interaction between functioning and environmental factors such as support or barriers from family, the general practitioner, the workplace, and social services. A health professional stated: “The LBP assessment tool broadens my approach to functioning and leads me away from only somatic and body function” (ID 1). The health professionals still expressed concerns about their competencies to manage psychosocial issues. Finally, the LBP assessment tool provided a quick overview pinpointing the patient's disability, “It [The LBP assessment tool] gives a quick overview and facilitates a sound use of our time with the patient” (ID 3). The health professionals also discussed the usefulness of the ClinRO-LBP. Overall, they liked it as a checklist for the assessment. However, they requested a text box to be provided at the end of the ClinRO-LBP for additional information. Furthermore, they specified that the ClinRO-LBP did not have any conclusions; thus, they had to look for the conclusion in the patient's health record, for example, to complete referral to rehabilitation. The health professionals suggested improving the design and technical production of the LBP assessment tool and to incorporate the data into the patient's health record. As the field-testing continued after the feedback meeting, no adjustments were performed, but suggestions for improvement were to be discussed after the field-testing.

Discussion

This study showed adequate comprehensiveness and acceptability of the PRO-LBP and the ClinRO-LBP. Overall, patients and health professionals found the LBP assessment tool feasible for use in routine clinical practice. Despite inclusion of essential facilitators as feasibility-testing, training of health professionals and engaging a local facilitator, the degree of implementation did not reach the nominated criterion value of 85% after three months. The feedback meeting with the health professionals served to identify the experiences of health professionals from being partners in the implementation of the LBP assessment tool. The analysis revealed that they used and valued the LBP assessment tool because it promoted a sound use of their time with the patient, it facilitated a smooth and positive consultation based on the patient perspective and it allowed them to apply a more biopsychosocial and a less biomedical approach. The analysis also documented that central topics in the implementation is shared learning among participants and thus an important step in the implementation of patient reported outcomes. Furthermore, this study supports that implementation of a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach into routine assessment of patients with LBP is a complex process affected by multiple factors.

Our process used to develop and test the LBP assessment tool was considered robust because it was evidence-based [Citation24,Citation32–34], patients and health professionals were involved and the process was assisted by the i-PARIHS [Citation38]. We found that involvement of patients and health professionals, feasibility-testing, training of health professionals, support from management, investment of time and resources and appointment of a local facilitator were important factors to facilitate the implementation. However, involvement of patients and health professionals are often an overlooked part in PRO development and implementation studies [Citation48]. Patient involvement was essential during the development of the PRO-LBP [Citation20,Citation21]. The field-testing showed that 1/3 of the patients wrote in the text box, which could indicate that relevant issues were missing in the PRO-LBP. However, this was probably not the case as 95% of the patients found the PRO-LBP to be comprehensive. Review of the content in the text boxes revealed that 60% of the patients' issues concerned pain, which was already covered by the PRO-LBP (Supplementary table S4). This could indicate that patients still have an unmet need to unfold their pain experiences, maybe because pain cannot be expressed solely by ticking off a box. The PRO-LBP comprised a relatively high number of items (minimum 76 items). Concerns have been raised about burdening patients with too many questions [Citation49], because it may affect the validity of the responses and lead to low response rates [Citation50]. However, we found a high response rate (95%), and in addition the health professionals reported that all patients could fill in the PRO-LBP. This finding might indicate that patient involvement in our study resulted in a PRO-LBP that was meaningful to patients and reflected what mattered to them despite the large number of items.

The degree of implementation reached 79% which was slightly lower than the nominated criterion value of 85%. This may be attributed to several reasons. It could be the complexity of the LBP assessment tool, which comprises three features to be implemented along with the aim to change the health professionals from a biomedical approach towards a biopsychosocial approach in assessment of patients. A strong evidence exists that innovations perceived simple to use are more easily adopted [Citation51,Citation52]. We were aware of the complexity of the LBP assessment tool; thus, we incorporated instruction and tryout in the training programme to support the implementation because practical experience and demonstration may reduce the complexity [Citation53]. It may be that health professionals were reluctant to implement PROs because they perceive it as not applicable to some patients or clinical situations or because of time constraints [Citation30]. It may be because several organisational changes were implemented during the field-testing resulting in changed daily workflow and undetermined factors because continuous monitoring was not performed during the field-testing [Citation36]. Finally, the nominated criterion value of 85% was solely based on findings in two previous studies [Citation54,Citation55]. Consequently, it could be argued that the value was set too high and therefore not achievable within the three-month period.

The feedback meeting showed that the LBP assessment tool led the health professionals to be more biopsychosocial and less biomedical oriented. This indicates that the LBP assessment tool can broaden health professionals' approach to functioning by pinpointing psychosocial issues, participation restriction, and influence by environmental factors. The health professionals had concerns about their competencies to manage psychosocial issues. This indicates that they can identify psychosocial factors and value their importance. However, due to lack of confidence in managing psychosocial issues, their use can be limited [Citation43,Citation56]. It appears that we can modify health professionals' beliefs and attitudes about LBP, but to achieve and sustain changes in clinical practice are more challenging [Citation43,Citation44]. One reason can be that educational programmes tend to focus on the biomedical approach to LBP though evidence strongly support use of a biopsychosocial approach [Citation44]. Thus, full implementation of the biopsychosocial approach will not succeed before educational programmes focus more to this approach to start a new professional culture. Furthermore, we need specific frameworks like the ICF to include learning about the biopsychosocial aspects, and we must provide user-friendly tools to facilitate the implementation in clinical practice. With the LBP assessment tool, we believe to have provided a user-friendly tool to support health professionals towards a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach to assessment of patients with LBP. Evidence strongly supports that a biopsychosocial and patient-centred assessment of functioning is an essential fundament towards improved individualised rehabilitation planning [Citation4,Citation57,Citation58]. Therefore, we hypothesise that the LBP assessment tool has the potential to influence clinical practice; this warrants further investigation.

We found that health professionals were satisfied with the LBP assessment tool and found it usable for routine clinical practice. There were particularly high use and satisfaction with the tool among the nurses. This is not surprising, as their defined role includes in-depth assessment of patient needs and focus on the biopsychosocial aspects [Citation55]. On the other hand, the physiotherapists were less satisfied with the LBP assessment tool, which may be explained by their dearth of knowledge and confidence about what to do with patients for whom key psychosocial obstacles to recovery are identified. They tend to practice within their areas of confidence, focusing on physical issues in favour of psychosocial issues to LBP [Citation43].

Methodological considerations

This study has some methodological strengths. We used an acknowledged implementation framework to assist the implementation; thus, we considered concepts of importance before introducing the LBP assessment tool. We also involved patients and health professionals in evaluation of content validity, and the results were based on a relatively large sample size (n = 134) [Citation41] with a high response rate (95% for the PRO-LBP and 88% for the follow-up questionnaire).

We are, however, aware of a number of limitations. The non-respondents (n = 25) might have different perspectives, possibly more negative; the exclusion of which could have led to an overestimation of the LBP assessment tool. The limited use of the tool in our study may be due to reduced implementation time. Carrying out the implementation over an appropriate length of time is crucial to increase the likelihood of successful implementation [Citation59]. Although the patient sample was large, the health professional sample was limited. However, we have no reason to believe that the results are in any way atypical of what would be found with a larger group of health professionals as health professionals varied in age, gender, professional background, and years of work experience (Supplementary table S3). This study was conducted in a single second-line hospital specialised in the assessment and management of patients with LBP. The LBP assessment tool was feasible in this setting, but whether it is feasible in a first-line setting, for example, in general practice or physiotherapy clinics, is unknown. Future studies are needed to evaluate the efficacy of the tool in other settings and with larger health professional and patient samples. Finally, a practical weakness of the LBP assessment tool was that data were not integrated into the patient's electronic health record due to technical and ethical barriers. Integration of these data could probably have increased the degree of implementation.

Conclusions

The PRO-LBP and the ClinRO-LBP covered relevant and important aspects of LBP from the perspective of patients and health professionals. Evaluation of the ClinRO-LBP indicated that the items reflected the construct to be measured; however, further studies among a larger sample of health professionals are needed. The LBP assessment tool was found acceptable by patients and health professionals for use in routine clinical practice. Furthermore, it allowed the health professionals to apply a biopsychosocial and patient-centred approach. The reduced degree of implementation after three months indicates that continuous attention to facilitation and training of health professionals is important to facilitate and maintain implementation of new procedures into routine clinical practice. Future research should investigate whether the LBP assessment can enhance patient-centred care among patients with LBP.

Supplemental_file_part_2_feb2021.docx

Download MS Word (38.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the patients and health professionals who generously contributed to the development and field-testing of the LBP assessment tool and the Spine Centre for hosting the study. We are grateful to research assistant Christina Dam Sørensen for preparing the electronic version of the PRO-LBP and ClinRO-LBP and for her contribution to the data collection. We are also appreciative to data manager Allan Lind-Thomsen for his great work producing the Patient-Profile-LBP.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy could be compromised, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356–2367.

- O’Sullivan P, Dankaerts W, O’Sullivan K, et al. Multidimensional approach for the targeted management of low back pain. In: Gwendolen A Jull, Gregory P Grieve, editors. Grieve's modern musculoskeletal physiotherapy. 4th ed. Edinburg, New York: Elsevier; 2015. p. 465–469.

- O'Sullivan P, Caneiro JP, O'Keeffe M, et al. Unraveling the complexity of low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2016;46(11):932–937.

- Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2368–2383.

- Pincus T, Kent P, Bronfort G, et al. Twenty-five years with the biopsychosocial model of low back pain-is it time to celebrate? A report from the twelfth international forum for primary care research on low back pain. Spine. 2013;38(24):2118–2123.

- Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ. 2001;322(7284):468–472.

- Mescouto K, Olson RE, Hodges PW, et al. A critical review of the biopsychosocial model of low back pain care: time for a new approach? Disabil Rehabil. 2020;1–15.

- Bagraith KS, Strong J. Chapter 22: Rehabilitation and the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. In: van Griensven H, Strong J, Unruh A, editors. Pain: a textbook for health professionals. Churchill Livingstone; 2014. p. 339–360.

- Rauch A, Cieza A, Stucki G. How to apply the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) for rehabilitation management in clinical practice. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008;44(3):329–342.

- Calvert M, Kyte D, Price G, et al. Maximising the impact of patient reported outcome assessment for patients and society. BMJ. 2019;364:k5267.

- Osthols S, Bostrom C, Rasmussen-Barr E. Clinical assessment and patient-reported outcome measures in low-back pain – a survey among primary health care physiotherapists. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(20):2459–2467.

- Chiarotto A, Maxwell LJ, Terwee CB, et al. Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and Oswestry Disability Index: which has better measurement properties for measuring physical functioning in nonspecific low back pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2016;96(10):1620–1637.

- Ibsen C, Schiottz-Christensen B, Melchiorsen H, et al. Do patient-reported outcome measures describe functioning in patients with low back pain, using the Brief International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Core Set as a reference? J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(7):618–624.

- Calmon Almeida V, da Silva Junior WM, de Camargo OK, et al. Do the commonly used standard questionnaires measure what is of concern to patients with low back pain? Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(10):1313–1324.

- Nicol R, Yu H, Selb M, et al. How does the measurement of disability in low back pain map unto the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)? A scoping review of the manual medicine literature. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;100(4):367–395.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- Fehrmann E, Kotulla S, Fischer L, et al. The impact of age and gender on the ICF-based assessment of chronic low back pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(10):1190–1199.

- Maribo T, Petersen KS, Handberg C, et al. Systematic literature review on ICF from 2001 to 2013 in the Nordic countries focusing on clinical and rehabilitation context. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8(1):1–9.

- Rundell SD, Davenport TE, Wagner T. Physical therapist management of acute and chronic low back pain using the World Health Organization's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Phys Ther. 2009;89(1):82–90.

- Ibsen C, Schiottz-Christensen B, Maribo T, et al. "Keep it simple": perspectives of patients with low back pain on how to qualify a patient-centred consultation using patient-reported outcomes . Musculoskeletal Care. 2019;17(4):313–326.

- Ibsen C, Schiøttz-Christensen B, Nielsen CV, et al. Assessment of functioning and disability in patients with low back pain – the low back pain assessment tool. Part 1: development. Disabil Rehabil. 2020. DOI:10.1080/09638288.2021.1913648

- Cieza A, Stucki G, Weigl M, et al. ICF core sets for low back pain. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36:69–74.

- Prodinger B, Cieza A, Oberhauser C, et al. Toward the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Rehabilitation Set: a minimal generic set of domains for rehabilitation as a health strategy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(6):875–884.

- Elwyn G, Kreuwel I, Durand MA, et al. How to develop web-based decision support interventions for patients: a process map. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):260–265.

- Foster NE. Barriers and progress in the treatment of low back pain. BMC Med. 2011;9:108.

- International Society for Quality of Life Research (prepared by Aaronson N ET, Greenhalgh J, Halyard M, Hess R, Miller D, Reeve B, Santana M, Snyder C). User’s guide to implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice; 2015; [cited 2020]. Available from: https://www.isoqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2015UsersGuide-Version2.pdf

- Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: a review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(8):1305–1314.

- Foster NE, Hartvigsen J, Croft PR. Taking responsibility for the early assessment and treatment of patients with musculoskeletal pain: a review and critical analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(1):205.

- Buchbinder R, van Tulder M, Oberg B, et al. Low back pain: a call for action. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2384–2388.

- Basch E, Barbera L, Kerrigan CL, et al. Implementation of patient-reported outcomes in routine medical care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:122–134.

- Brundage MD, Smith KC, Little EA, et al. Communicating patient-reported outcome scores using graphic formats: results from a mixed-methods evaluation. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(10):2457–2472.

- Santana MJ, Haverman L, Absolom K, et al. Training clinicians in how to use patient-reported outcome measures in routine clinical practice. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1707–1718.

- Rothrock NE, Kaiser KA, Cella D. Developing a valid patient-reported outcome measure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90(5):737–742.

- De Vet H, Terwee C, Mokkink L, Knol D. Chapter 3: Development of a measurement instrument. In: Measurement in medicine: a practical guide (Practical Guides to Biostatistics and Epidemiology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011. p. 30–64.

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(4):50.

- Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, et al. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(2):107–112.

- Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci. 2016;11:33.

- Kent P, Kongsted A, Jensen TS, et al. SpineData – a Danish clinical registry of people with chronic back pain. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:369–380.

- Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63–74.

- Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1159–1170.

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):88.

- Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(23):3027–3034.

- Bainbridge D, Seow H, Sussman J, et al. Multidisciplinary health care professionals' perceptions of the use and utility of a symptom assessment system for oncology patients. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(1):19–23.

- Sanders T, Foster NE, Bishop A, et al. Biopsychosocial care and the physiotherapy encounter: physiotherapists' accounts of back pain consultations. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;19(14):65.

- Foster NE, Delitto A. Embedding psychosocial perspectives within clinical management of low back pain: integration of psychosocially informed management principles into physical therapist practice—challenges and opportunities. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):790–803.

- Edmondson AC, Bohmer RM, Pisano GP. Disrupted routines: team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Admin Sci. 2001;46(4):685–716.

- Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J. Refinements of the ICF linking rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;41(5):1–10.

- Thorne S. Part I: interpretive description in theory. Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2016.

- Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ. 2008;337:a1714.

- Basch E. Patient-reported outcomes – harnessing patients' voices to improve clinical care. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):105–108.

- Galesic M, Bosnjak M. Effects of questionnaire length on participation and indicators of response quality in a web survey. Public Opin Quart. 2009;73(2):349–360.

- Denis JL, Hebert Y, Langley A, et al. Explaining diffusion patterns for complex health care innovations. Health Care Manage Rev. 2002;27(3):60–73.

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629.

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovation. 5th ed. New York: New York Free Press; 2003.

- Stilwell P, Hayden JA, Des Rosiers P, et al. A qualitative study of doctors of Chiropractic in a Nova Scotian practice-based research network: barriers and facilitators to the screening and management of psychosocial factors for patients with low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2018;41(1):25–33.

- Cieza A, Stucki G. Understanding functioning, disability, and health in rheumatoid arthritis: the basis for rehabilitation care. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17(2):183–189.

- O'Sullivan P. It's time for change with the management of non-specific chronic low back pain. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(4):224–227.

- Cresswell KM, Bates DW, Sheikh A. Ten key considerations for the successful implementation and adoption of large-scale health information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(e1):e9–e13.