Abstract

Purpose

To explore, in a European cohort of people living with Parkinson’s (PD), issues affecting employment and economic consequences, considering age at diagnosis.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional survey (European convenience sample). Inclusion criteria were ≥18 years, a PD diagnosis and in work when diagnosed. Data were collected online on demographics, employment status, occupation, and perceived health. For those no longer in paid work, time from diagnosis until loss of employment, reasons for leaving and enablers to stay in work were ascertained.

Results

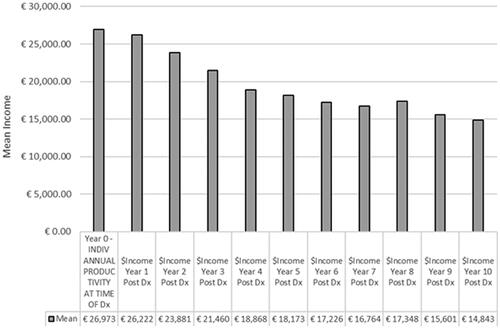

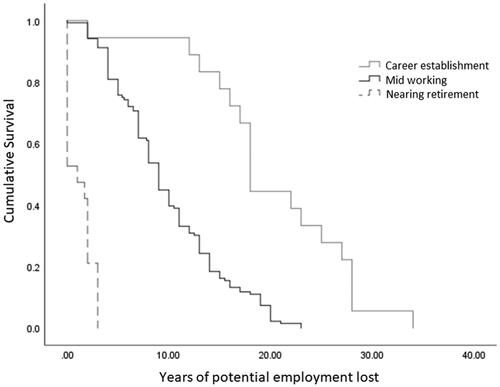

Between April and November 2019, n = 692 enrolled and n = 560 were eligible. Those who had lost paid work (n = 190, 34%) reported worse fatigue, sleep, and general health than those still in work (p < 0.05). Average annual income reduced from €26973.48 ± 12013.22 (year-1) to €14843.85 ± 16969.84 (year-10). Post-diagnosis lost employment potential was 20.1 (95% confidence interval (CI): 16.6–23.6) years at career establishment, 9.8 (95%CI: 8.9–10.7) years at mid working and 1.2 (95%CI: 0.6–1.6) years for those nearing retirement age. A greater proportion of individuals at career establishment age reported dexterity, eating, sleep, fatigue, and anxiety as factors for leaving work (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

This study confirms lost productivity after a PD diagnosis, especially in those with many years of potential employment ahead. The study also identified potential targets for interventions. Clinical trial registration: Clincaltrials.gov (NCT03905954).

People with Parkinson’s diagnosed at career establishment or at mid working age risk losing many years of potential employment.

Most people with Parkinson’s do not receive early intervention to support self-management of problems identified with leaving work early, such as fatigue.

Adaptations to the work environment and more flexible working patterns were identified factors that may help people remain in work.

Implications for rehabilitation

Introduction

Unemployment negatively impacts quality and satisfaction with life [Citation1], particularly when employment is lost due to poor health [Citation2]. For those with Parkinson’s disease (PD), being employed has been found to be important for self-esteem, personal identity and is central for social interaction, role and status [Citation3]. Notwithstanding the impact to the individual and their family, the loss of productivity has a wide economic impact [Citation4] with 70% less likely to be employed than their peers [Citation1].

Globally, approximately six million people have PD with incidence increasing and by 2040 it is projected that 17 million people could be living with PD [Citation5]. In Europe, the estimated annual total cost of PD was estimated at €13.9 billion in 2010 [Citation6] and with increasing prevalence economic burden is predicted to rise. Indirect costs account for 30–40% of total costs [Citation7] in Europe, estimated to be between £11 000 and £12 500 per person per annum in the UK [Citation8].

Studies in European cohorts have found that employment rates within five years of a diagnosis range from 15 to 46% [Citation9–11], with older age, being female, lower-income occupations, duration of disease, cognitive performance, depression, and the ability to perform activities of daily living associated with loss of employment [Citation12,Citation13]. While age of onset correlates negatively with time to loss of employment, Schrag et al. [Citation14] found that compared to older-onset, those with young-onset PD were more likely to be unemployed due to disability, were more frequently depressed and had a lower quality of life.

Despite the personal and wider economic impact of this disease, there is limited understanding on the reasons for leaving employment and interventions which might retain these employees in work. Indeed, concerns persist that people with PD do not receive the support they need to remain in their vocation [Citation15,Citation16].

Our aim was to explore, in a pan European cohort, employment rates and the issues affecting employment in individuals, diagnosed at different ages, to inform the future development of interventions targeted to lessen the financial impact to employees and reduce the wider burden of the condition on the economy. Specifically, in a European sample, we aimed to (1) describe and compare demographic and health factors in those with PD who remain in employment with those who became unemployed after diagnosis, (2) describe time to loss of employment, lost employment potential and economic impact of in those no longer in work in those of different working age at diagnosis, and (3) describe perceived factors associated with losing employment and potential factors in maintaining employment in those of different working ages at diagnosis.

Materials and methods

Design

A cross-sectional survey of the impact of PD on employment was performed. Data were collected via an online questionnaire from a community based European convenience sample. The study was approved by Oxford Brookes University Ethics committee and registered on Clincaltrials.gov (NCT03905954). Reporting took into consideration the STROBE statement on cross-sectional studies [Citation17].

Participants and setting

Between April 2019 and November 2019, participants self-selected entry to the study in response to advertisements placed on the European Parkinson’s Disease Association (EPDA) website. The study was promoted by EPDA and its member organisations, representing 26 nations throughout Europe. After reading information about the study on the EPDA website, individuals were able to choose to take part by clicking a hyperlink to the online survey. To be included participants had to be ≥18 years old and have a diagnosis of PD. There were no exclusion criteria, however, to be included in analysis participants had to have provided data on employment status.

Eligibility was self-assessed and the survey was available in English, Dutch, French, Spanish, Polish, Italian, Slovenian, Danish, German, and Czech languages. The opening page of the survey served as the participant information sheet and detailed their rights as study participants. Consent was obtained through compulsory check boxes that were required to be completed in order to proceed. No formal a priori sample size calculation was performed and the number of responses during the study period determined the sample size. However, at registration, we estimated approximately 1000 people would be recruited. Considering an estimated prevalence of 1 060 000 [Citation18] in Europe and a confidence level of 95%, 1000 people would give a margin of error of 3.1%.

Variables

Data were collected on demographics including, age (current and at diagnosis), gender, country of residence, and education level. Employment questions included employment status, occupation, and basic contract working hours per week at diagnosis. Perceived health was assessed on 0–10 (0 best, 10 worst) visual analogue scales for distress, pain, fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleep, and general health. For those no longer in paid work, time from diagnosis until loss of employment, reasons for leaving paid work (problems with mobility, manual dexterity, sleep, cognition, communication, anxiety, depression, motivation, bladder and bowel, autonomic functions, eating and drinking) and information on what in their opinion would have supported participants to stay in paid work (early intervention, more flexible working, adaption to work environment, more support (from managers, occupational health, colleagues, partners and support with personal care), were sought (see Supplement 1 for questions).

Data sources

All data were obtained via an online survey via the Qualtrics software platform. The survey was designed by the study team in consultation with people with PD, who trialled the survey prior to it being released. The questionnaire bifurcated so that participants were not progressed to questions that were not relevant for them (i.e., those in work were not asked reasons for leaving work questions). The survey was accessed by participants via a device with internet connection (phone, computer, tablet). Names or other identifying details were not collected.

Quantitative variables

Participants were not included in the analysis if they were not in paid work at the time of diagnosis. Participants were then grouped according to whether they were currently in (paid) work or no longer in (paid) work. Age at diagnosis was used to stratify participants into people who were career establishment age (18–40 years), mid working age (>40 to 60 years) or nearing retirement (>60 years). Lost potential employment years was calculated as years between age of loss of employment and 65 years, which is, accounting for country and gender differences, deemed the most general retirement age across Europe [Citation19]. Occupations were grouped into “blue-collar” (services, agriculture, craft, machine, elementary, technical, and armed forces) and “white-collar” (clerical, or managerial) professions, considering the ISCO-08 [Citation20].

Economic evaluation

The economic evaluation sought to quantify the financial impact from an individual productivity perspective, between the ages of 18 and 65 (see Supplement 1 for extra methodology detail). Costs were reported using the Euro dollar adjusted to the year 2019. Each type of occupation was valued based on the median 2017 monthly gross income in Europe in 2017 [Citation21], indexed by CPI and multiplied into an annual full time income. Armed Forces income was calculated separately. Across all occupations, the annual income was applied pro rata for the participants based on self-reported weekly hours of employment, to determine the individual annual income at the time of diagnosis. Average annualised prediagnosis income was compared to average annualised post diagnosis income to present lost average income.

Participants were considered “out of scope” and therefore not included in economic analyses from each one-year time horizon analyses if that time horizon had not occurred at the time of survey (e.g., if the survey was completed by an individual three years post diagnosis, this individual was removed from the years 4 to 10 analyses), or if they were aged over 65 in that one-year time horizon, indicating retirement age.

Participants were mapped according to the following four categories across the year 1 to year 10 time horizon: (1) continued in paid work in the same occupation, (2) ceased paid work while aged between 18 and 65 years, (3) retirement age criteria met (aged 66 years or over; this indicated the data was “out of scope”), and (4) survey completed prior to the 10 year study time horizon (this indicated that some or all of the data were “out of scope” to cover the 10 years).

Only categories 1 and 2 were included in the cost analyses to determine the average annualised post diagnosis income.

Missing data

As the missing data were low, we did not impute data and reported the amount of missing data at variable level in the results.

Statistics

Initial analysis comparing demographic and employment characteristics between those in work versus not in work was performed using χ2, independent samples median test or t-test according to variable type, and was reported with descriptive statistics. The Cox regression analysis was used to estimate the associations with time from diagnosis to loss of employment. Included in the model were age at diagnosis, gender, and type of occupation (white or blue collar). Kaplan–Meier’s analysis was used to estimate average years of lost potential employment (with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)) and determine differences between age groups at diagnosis. Reasons for leaving paid work and what would have supported participants to stay in work were reported descriptively as frequency and compared between age categories using χ2.

For the economic evaluation, the frequency of the four categories ((1) continued paid work, (2) ceased paid work, (3) retirement age, and (4) survey completed prior to full study time horizon) was reported for each year of the 10 year time horizon. Categories 3 and 4 were excluded from the yearly time horizon analyses as they were deemed “out of scope” due to retirement age or an incomplete 10 year time horizon, i.e., if a participant provided 8 years of employment data, they would be removed from the final 2 years of the analysis. The average annual income is reported based on those who continued in paid work in the same occupation (wage maintained per the time of diagnosis) and those who ceased paid work while aged between 18 and 65 years (wage noted as €0). A paired samples t-test was used to report a significant difference between time point 0 (time of diagnosis) and year 1, between year 1 and year 2, and so on until year 9 and year 10. It is expected that each consecutive paired sample t-test will have fewer participants as the number of participants in categories 3 and 4 increased and were therefore excluded from the analyses. All analyses were completed in SPSS Version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and significance was indicated at p < 0.05.

Results

Participants

Between April 2019 and November 2019, a total of 692 people took part in the survey from 28 European counties, including n = 46 (6.7%) who reported living outside Europe at the time of the survey. People living in the UK (n = 187, 27.1%), Netherlands (n = 121, 17.5%), and Italy (n = 103, 14.9%) made up approximately 60% of the sample (Supplement 1, Table 1 for full details).

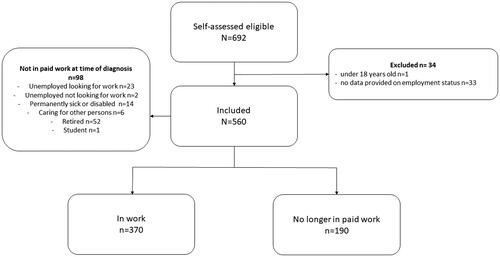

Participant flow can be found in , n = 34 were excluded and n = 98 not in paid work at the time of diagnosis were not included in analysis. Included in analysis were n = 370 in paid work and n = 190 that had lost employment after diagnosis (no longer in work).

Figure 1. Participant flow.

Comparison between those in work and those no longer in work

Demographic and employment data comparing groups according to occupation status can be found in . There was no difference between groups in gender (approximately half female), age at diagnosis, education, or occupation at diagnosis. Individuals no longer in paid work perceived fatigue, sleep, and general health to be worse (p < 0.05). Individuals in paid work were younger at the time of the survey and had been more recently diagnosed with only 29.2% of people in paid work diagnosed for more than 5 years.

Table 1. Comparison of participants in work to those no longer in paid work.

We went on to investigate further factors associated with loss of employment in the individuals’ no longer in work.

Time to loss of employment and lost employment potential in those no longer in work

Mean time from diagnosis of PD to loss of employment was 4.2 ± 4.4 years. There was no association between time to loss of employment and gender (exp β = 1.247, Wald = 2.177, p = 0.140), or type of profession (exp β = 1.353, Wald = 3.560 p = 0.059). An older age at diagnosis was significantly associated with less time between diagnosis and loss of employment (exp β = 1.054, Wald = 29.306, p= <0.01). However, those who were older were closer to retirement and had less potential years of employment remaining.

shows potential years of employment lost were greater for those at a younger age at diagnosis (Mantel–Cox log rank: χ2=74.828, p= <0.001) with 20.1 potential years of employment lost (95%CI: 16.6–23.6, n = 18)) at career establishment age, 9.8 years (95%CI: 8.9–10.7, n = 142) for mid working age and 1.2 years (95%CI: 0.6–1.6, n = 28) for those nearing retirement age.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier’s curve of estimate average years of lost potential employment according to age at diagnosis.

Perceived factors associated with losing employment

Most individuals (80.3%, n = 151) reported PD as their main reason for leaving paid work, with a significantly (χ2=12.48, p = 0.02) greater proportion of those at career establishment (94.4%, n = 17) and of mid working age (83.1%, n = 118) reporting the condition as their main reason compared to those nearing retirement (57.1%, n = 16). Most individuals (67.1%, n = 100, missing data n = 3) reported they would have preferred to stay at work in some capacity.

Problems that contributed to participants leaving employment, in order of frequency reported, were: fatigue (n = 90, 47.4%); mobility (n = 84, 44.2%); manual dexterity (n = 81, 42.6%); sleep problems (n = 63, 33.2%); cognition (n = 44, 23.2%); communication (n = 41, 21.6%); anxiety (n = 41, 21.6%); motivation (n = 37, 19.5%); depression (n = 29, 15.3%); bladder or bowel symptoms (n = 22, 11.6%); autonomic functions (n = 13, 6.8%); eating and drinking (n = 10, 5.3%); none of the listed options (n = 9, 4.7%).

shows a significantly greater proportion at career establishment age reporting, manual dexterity, eating and drinking, sleep, fatigue, and anxiety as factors associated with them leaving work (p < 0.05). Reasons selected by those who were no longer in paid work as to support that may have helped them to stay in work, in order of frequency reported, were: early intervention providing information to manage PD (n = 48, 25.3%); better understanding from managers (n = 40, 21.1%); adaptation to the work environment (n = 33, 17.4%); flexible working hours (n = 33, 17.4%); flexible working pattern (n = 30, 15.9%); better support from occupational health (=24, 12.6%); better support from colleagues (n = 22, 11.6%), better support from partner (n = 12, 6.3%); support with personal care (n = 12, 6.3%). also shows a significantly greater proportion at career establishment age identifying adaptation to the work environment and more flexible working pattern as factors that may have helped them stay at work (p < 0.05).

Table 2. Comparison between ages categories of factors associated with leaving work and factors that may have support remaining in work.

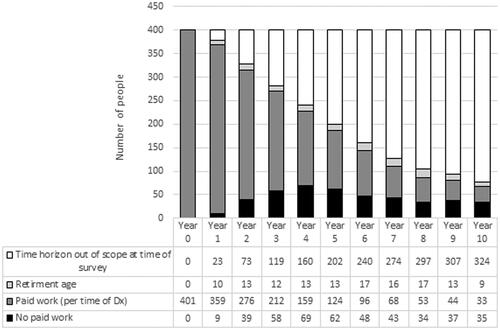

Economic evaluation

shows the economic analysis, the time horizon for those who were “out of scope” throughout the survey, increased year on year with 23 people (5.7%) excluded in year 1 and 324 (80.8%) excluded in year 10. People reaching retirement age remained consistent across each years’ time horizon with a range of 9–17 per year (n = 9, 2.2% in year 10, n = 17; 4.2% in years 6 and 8). The average income followed a similar pattern () and at the time of the survey, the average annual income across all eligible participants was €26973.48 ± 12013.22, by year 5 the average annual income was €18173.19 ± 16583.09, and by year 10 the average annual income was €14843.85 ± 16969.84. Over the 10 year time horizon, all pairs had a reported reduction in income with eight of the years reporting a statistically significant reduction in income (p < 0.05) (Supplement 1, Table 3).

Figure 3. Economic evaluation participant classification over time horizon.

Discussion

Our Pan-European study augments results of previous studies carried out in individual European countries over the last 15 years indicating that within five years of a PD diagnosis approximately half of people will be unemployed [Citation1,Citation9–11]. Notably, these studies consistently demonstrate a need to support people with PD to stay in work, yet our most current data suggest that there has been little improvement over this period. Our results identify potential targets for intervention including work modifications and adjustments, and highlight the potential for impact if a successful intervention can maintain younger people with PD in work, reducing the economic burden caused by this loss of productivity. This study found that less than a quarter of the sample received early intervention to help manage their condition, yet this was most commonly identified in those who became unemployed after a diagnosis as support that might have helped them to remain in work.

Whist, Martikainen et al. [Citation9] (Finland) reported higher rates of unemployment, we found 51% of people were unemployed after 5 years of a PD diagnosis which is consistent with previous earlier European studies in Schrag and Banks (UK), 46% [Citation11], Murphy et al. (Ireland), 60% [Citation10], and Gustafsson et al. (Sweden), 47% [Citation1]. Both Schrag and Banks [Citation11] and Murphy et al. [Citation10] excluded people over 65 years and Gustafsson et al. [Citation1] 67 years. We did not exclude based on an upper age limit. However, people who had already retired at the time of their diagnosis were not included in the analysis and the average age at diagnosis in our sample is comparable to that in the aforementioned studies. These data indicate on-going challenges in maintaining employment after a diagnosis of PD across Europe. Furthermore, minimum statutory pension ages are scheduled to increase in most European countries [Citation19], thus unemployment is set to impact more people with PD for a longer period. In the UK, minimum statutory pension age is set to increase to 68 by 2046, with Parkinson’s UK estimating a PD prevalence in under 69 year olds of 29 545 in 2045 [Citation22]. Together these highlight the pressing need to support people with PD to remain in work.

Reasons for leaving work are individual and multifaceted [Citation15], however, previous studies have found between 23 and 75% of people with PD report retiring early directly because of their condition [Citation16]. We found only 57% of those nearing retirement cited PD as their main reason for leaving work compared to 83% of mid working age and 94% of those at career establishment age. This is particularly relevant in those who are younger and are leaving work due to PD when considering lost productivity was associated with age, with an estimated 9.8 years (95%CI: 8.9–10.7) and 20.1 (95%CI: 16.6–23.6) potential years of employment lost for those of mid working and career establishment ages, respectively. This directly impacts individual lifetime earnings with a consequential increase to societal costs [Citation4,Citation16]. Our economic analysis found that in the 10 years after a PD diagnosis, average annual income reduced from €26973.48 to €18173.19 at year 5, and €14843.85 at year 10. Our findings support that people diagnosed with PD when at a younger age experience a higher loss of lifetime earnings potential, these financial and wellbeing pressures may be exacerbated by considerations such as mortgages and the impact on family members [Citation8]. Schrag et al. [Citation14] compared those with onset before 50 years to those with later onset finding those with younger onset had greater disruption to family life, stigmatisation, and depression than those with older-onset Parkinson’s. Therefore, it may be particularly pertinent to consider factors associated with working for those younger at diagnosis. Compared to those nearing retirement, we found a higher proportion of those at career establishment age reported manual dexterity, eating and drinking sleep, anxiety, fatigue, and anxiety as factors for them leaving work. Manual dexterity was the factor identified in more than three quarters of those at career establishment age (and identified more in mid working age compared to nearing retirement). Interventions to improve manual dexterity (hand-writing) have shown promise and can be pragmatically delivered through self-managed weekly practice [Citation23], and thus may offer a simple low cost way to support people stay in work.

Fatigue was the most frequently reported symptom contributing to people leaving work, especially for those diagnosed at career establishment or mid working ages. This finding was substantiated by those no longer in work reporting their fatigue to be worse than those who remained in work and by previous studies that have identified fatigue as a predominant factor in people leaving work [Citation1,Citation10,Citation16]. Although effective treatments for fatigue have yet to be established [Citation24,Citation25], fatigue has been addressed in self-management interventions for PD [Citation26–28]. Our results suggest access to programs to provide information and promote self-management is limited with only 22% of our cohort reporting receiving early intervention. Widening access to self-management programs to those with PD and including knowledge about employment support options and employment challenges [Citation15] may offer a way to support people to say in work longer, and mitigate the impact on mental health due to the demands of work exceeding capacity and losing paid work [Citation1]. To accommodate self-management of symptoms, such as fatigue, adapting the working environment is seen as a key component of enabling people with PD to remain in work [Citation3]. However, Koerts et al. [Citation16] found requests for adjustments to the workplace were not always supported. A quarter of the current cohort who were not in paid work identified at least one workplace related factor that may have helped them to stay in work. Notably, we found flexible working may be a more important factor in those at career establishment stage, with a third identifying adaptions to the work environment and half identifying a more flexible working pattern would have helped them to stay at work. Recently, to meet employment related resource needs of people with PD a flexible tailored approach to employment adaptations has been advocated [Citation15].

Limitations

There are a number of limitations associated with our study. First, this was a convenience sample and relied on self-confirmed eligibility and reporting and therefore is susceptible to the associated biases. Indeed, our sample was a young PD demographic [Citation5], with 84% diagnosed before 60 years of age and 61% were within 5 years of a diagnosis. However, this demographic is relevant when considering employment and our analysis comparing age at diagnosis. Our pan European sample is both a strength and a weakness of the study. While, EU general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation (2000/78/EC) applies across the EU (including the UK at time of survey, with the Equality Act remaining un-amended post Brexit), cultures, attitudes and some legislation may differ. Furthermore, while the survey was available in 10 languages, the cohort was predominately completed by people living in the UK, the Netherlands, and Italy and in our economic analysis we used cross Europe estimates. Our analysis used a retirement age of 65 as this reflects the most general retirement age across Europe [Citation19]; however, it should also be noted that in the UK, the Netherlands, and Italy minimum statutory pension age is older than this. We also did not reach our expected number of participants over the 8 months when the survey was available, increasing the estimated margin of error to 4%. The above factors should be considered when assessing the generalisability of the findings alongside that the study took place prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. The long-term consequence of the pandemic on working practices is unknown. However, increased home working may present an opportunity to assist people with PD to remain in work, should this flexibility from employers be retained.

Conclusions

This study confirms that there remains the need to support people with PD in work to stay in work. The results particularly highlight the financial impact and lost productivity of younger people with PD leaving work with many years of potential employment ahead of them. The data also provide potential targets for symptom management interventions and work place modifications, reiterating the impact of fatigue and identifying pertinent factors in younger individuals such as manual dexterity. However, a better understanding of the components and delivery of early employment related intervention for those with newly diagnosed with PD is required, and the effectiveness at helping people retain work needs to be evaluated. Future studies should consider cost-benefit including economic analyses workplace modifications, to determine the most cost-effective approaches for retaining employment for people with PD.

Supplement_1_dis_and_rehab.docx

Download MS Word (25.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the European Parkinson’s Disease Association (EPDA) for supporting the development of the survey and facilitating its distribution and the Dutch, French, Spanish, Polish, Italian, Slovenian, Danish, German, and Czech associations for translating the survey. In particular, we like to thank Francesco De Renzis (EPDA) for his support. We would like to thank those who took part in the survey.

Disclosure statement

The following interests are declared: NC is managing director of Cordell Health Ltd; AR is director of the European Parkinson therapy centre. HD is funded by The Elizabeth Casson Trust and NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre and NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

References

- Gustafsson H, Nordstrom P, Strahle S, et al. Parkinson's disease: a population-based investigation of life satisfaction and employment. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47(1):45–51.

- Norstrom F, Virtanen P, Hammarstrom A, et al. How does unemployment affect self-assessed health? A systematic review focusing on subgroup effects. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1310.

- Mullin RL, Chaudhuri KR, Andrews TC, et al. A study investigating the experience of working for people with Parkinson's and the factors that influence workplace success. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(17):2032–2039.

- Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Forjaz MJ, Lizan L, et al. Estimating the direct and indirect costs associated with Parkinson's disease. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(6):889–911.

- Dorsey ER, Sherer T, Okun MS, et al. The emerging evidence of the Parkinson pandemic. J Parkinsons Dis. 2018;8(s1):S3–S8.

- Olesen J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, et al. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(1):155–162.

- von Campenhausen S, Winter Y, Rodrigues e Silva A, et al. Costs of illness and care in Parkinson's disease: an evaluation in six countries. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(2):180–191.

- Gumber A, Ramaswamy B, Thongchundee O. Effects of Parkinson's on employment, cost of care, and quality of life of people with condition and family caregivers in the UK: a systematic literature review. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;10:321–333.

- Martikainen KK, Luukkaala TH, Marttila RJ. Parkinson's disease and working capacity. Mov Disord. 2006;21(12):2187–2191.

- Murphy R, Tubridy N, Kevelighan H, et al. Parkinson's disease: how is employment affected? Ir J Med Sci. 2013;182(3):415–419.

- Schrag A, Banks P. Time of loss of employment in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21(11):1839–1843.

- Armstrong MJ, Gruber-Baldini AL, Reich SG, et al. Which features of Parkinson's disease predict earlier exit from the workforce? Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(11):1257–1259.

- Perepezko K, Hinkle JT, Shepard MD, et al. Social role functioning in Parkinson's disease: a mixed-methods systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(8):1128–1138.

- Schrag A, Hovris A, Morley D, et al. Young- versus older-onset Parkinson's disease: impact of disease and psychosocial consequences. Mov Disord. 2003;18(11):1250–1256.

- Rafferty M, Stoff L, Palmentera P, et al. Employment resources for people with Parkinson's disease: a resource review and needs assessment. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31(2):275–284.

- Koerts J, Konig M, Tucha L, et al. Working capacity of patients with Parkinson's disease – a systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;27:9–24.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–808.

- GBD 2016 Parkinson's Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson's disease, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):939–953.

- Finnish Centre for Pensions. Retirement ages in different countries [online]. Finnish Centre for Pensions 2019; 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 13]. Available from: https://www.etk.fi/en/the-pension-system/international-comparison/retirement-ages/

- International Labour Organization. International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO 08) [online]. International Labour Organization; 2016 [cited 2021 Jul 13]. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/isco08

- Skills Panorama. Monthly gross income: Cedefop; 2018 [cited 2021 Jul 13]. Available from: https://skillspanorama.cedefop.europa.eu/en/dashboard/monthly-gross-income

- Parkinson's UK. The incidence and prevalence of Parkinson's in the UK: results from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink Reference Report; 2017. Available from: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-01/Prevalence%20%20Incidence%20Report%20Latest_Public_2.pdf

- Collett J, Franssen M, Winward C, et al. A long-term self-managed handwriting intervention for people with Parkinson's disease: results from the control group of a phase II randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(12):1636–1645.

- Franssen M, Winward C, Collett J, et al. Interventions for fatigue in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014;29(13):1675–1678.

- Elbers RG, Verhoef J, van Wegen EE, et al. Interventions for fatigue in Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8(10):CD010925.

- Chaplin H, Hazan J, Wilson P. Self-management for people with long-term neurological conditions. Br J Community Nurs. 2012;17(6):250–254, 256–257.

- Hellqvist C, Bertero C, Dizdar N, et al. Self-Management education for persons with Parkinson's disease and their care partners: a quasi-experimental case-control study in clinical practice. Parkinsons Dis. 2020;2020:6920943.

- Soundy A, Collett J, Lawrie S, et al. A qualitative study on the impact of first steps—a peer-led educational intervention for people newly diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. Behav Sci. 2019;9(10):107.