Abstract

Purpose

Identify ethical issues that arise in the coordination of return-to-work (RTW) among employees on sick leave due to common mental disorders (CMDs).

Material and methods

41 semi-structured individual interviews and one focus group interview with stakeholders (n = 46) involved in RTW: employees on sick leave due to CMDs, coordinators and physicians at primary health care centres, managers, representatives of the Swedish social insurance agency and occupational health services. A six-step thematic analysis focused on the ethical values and norms related to autonomy, privacy, resources and organization, and professional values.

Results

Five themes were identified: (1) autonomous decision-making versus the risk of taking over, (2) employee rights versus restrictions to self-determination, (3) respect for employee privacy versus stakeholders’ interests, (4) risk of unequal inclusion due to insufficient organizational structure and resources, (5) risk of unequal support due to unclear professional roles and responsibilities.

Conclusion

The main ethical issues are the risks of unequal access to and unequal support for the coordination of RTW. For the fair and equal provision of coordination, it is necessary to be transparent on how to prioritize the coordination of RTW for different patient groups, provide clarity about the coordinator’s professional role, and facilitate ongoing boundary work between stakeholders.

Unfair and arbitrary criteria for inclusion to the coordination of RTW implicate risks of unequal access for the employee on sick leave due to CMDs.

Unclear professional roles and responsibilities among stakeholders in the coordination of RTW implicate risks of unequal support for the employee on sick leave due to CMDs.

Coordination of RTW should be transparently prioritized on policy and organisational levels to secure fair and equal inclusion.

The coordinator’s professional role should be clearly defined to facilitate boundary work between stakeholders and improve the competence around the coordination of RTW.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

Diagnoses related to common mental disorders (CMDs) such as stress, depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorders are one of the leading causes of long-term sick leave in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries (OECD) [Citation1], including Sweden [Citation2]. The burden of CMDs harms the employee as well as the local economy. In the European Union, the costs of mental health problems were estimated at €600 billion in 2018 [Citation3]. The individual and societal costs of sick leave related to CMDs make interventions to improve return-to-work (RTW) outcomes imperative.

Supporting the individual in RTW after CMDs is complex partly due to the organizational structure for RTW, with stakeholders situated in the healthcare services, the workplace, and legislative and social insurance systems [Citation4,Citation5]. Previous research has identified several barriers to collaboration among stakeholders [Citation6–9]. The identified barriers are partly explained by different perspectives and interests among stakeholders [Citation8] and a lack of routine in the RTW-process [Citation6,Citation9]. Uncertainty about roles and courses of action among stakeholders can lead to ineffective RTW-processes for the employee on sick leave due to CMDs [Citation5]. Considering the multiple stakeholders involved in RTW, the professional values of individual stakeholders can have implications for the implementation of RTW and can influence the treatment and support received by the patient. A coordinated approach to RTW is increasingly being implemented to overcome barriers to collaboration in RTW [Citation9–13]. In Sweden, for example, a new act on coordination measures for persons on sick leave specifies the legal requirement for healthcare services to coordinate RTW [Citation14].

The decision to implement a new intervention, such as the coordination of RTW, should be based on science and best practice. In decision-making, any potential ethical issues arising from the intervention must be taken into consideration. This can help to determine whether the intervention is ethically sound and whether future development or adaptations are needed [Citation15,Citation16]. The effects of RTW coordination programs on sick leave and RTW outcomes remain uncertain [Citation17,Citation18]. Moreover, a lack of ethical integration into the scientific literature on RTW regarding ethics theories, principles, and concepts has been identified. Ethical analysis of dilemmas in the RTW-process can guide the systematic examination of the interests, actions, and interactions of the stakeholders involved in RTW [Citation19,Citation20]. In addition, because coordination of RTW involves several specific systems, it is important to understand the ethical values and norms of these different systems—and consequently, adapt the ethical analysis for the specific setting in which the intervention is proposed.

To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have analyzed ethical aspects of the coordination of RTW. Therefore, this study aimed to identify ethical issues that arise in the coordination of RTW among employees on sick leave due to CMDs. This study will explore ethical values and norms related to: (1) autonomy, to what extent the person with CMD is able and allowed to influence the process of RTW; (2) privacy, how private and sensitive information is handled in this process; (3) fair distribution and equality of resources in the process of RTW and, finally; (4) professional values, how the ethos of having a professional role might impact the process. These are included in an established ethical framework developed by Swedish authorities [Citation15] and are in line with established ethics frameworks for health technology assessment [Citation21]. In our study, coordination of RTW was defined as the support given to/received by the employee to achieve RTW and cooperation with his or her manager by means of a three-party meeting—in line with the implementation of psychiatric guidelines in the primary health care sector [Citation22].

Methods

This qualitative, descriptive study used empirical data included in a thematic analysis [Citation23,Citation24]. The authors represent different research areas: organisational ethics in healthcare, public health, and occupational medicine, and are experienced in research about RTW among persons with CMDs. The present study is part of a larger project focusing on the coordination of RTW among employees on sick leave due to CMDs (the CORE-project) and follows the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research [Citation25]. The design of the CORE-project is described in a study protocol, published open access [Citation26]. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Reg. no 2018/677-31/2 and 2018/2119–32).

In Sweden, the healthcare and social insurance systems are mainly tax-funded. Responsibility for RTW is shared between the Swedish social insurance agency (SSIA), the manager, the employee, and the healthcare services. The SSIA carries overall responsibility for monitoring and coordinating RTW and decides eligibility for sick leave benefits based on a certificate issued by a physician [Citation27]. The manager is responsible for supporting an efficient RTW-process [Citation27] and for making adjustments for the employee [Citation28]. The occupational health services (OHS), voluntary for Swedish employers, may assist in health promotion, preventive measures, and RTW-processes. The employee on sick leave is obliged to provide information to form the basis for sickness certification and rehabilitation measures and to actively engage in the RTW-process. With the new act on coordination measures for persons on sick leave [Citation14], the healthcare services should—in addition to providing medical care and rehabilitation—focus on individual support for the employee on sick leave and the internal and external coordination of stakeholders. As a result, the coordination of RTW, organized by an on-site coordinator has been broadly implemented at primary health care centres (PCCs) [Citation29]. Although no minimum qualifications are provided, having a health care professional background is common, such as being a registered occupational therapist, nurse, or physiotherapist. Because coordination of RTW in Sweden is organized within the healthcare system, the ethical values and norms of Swedish healthcare legislation are central to our study.

Participants

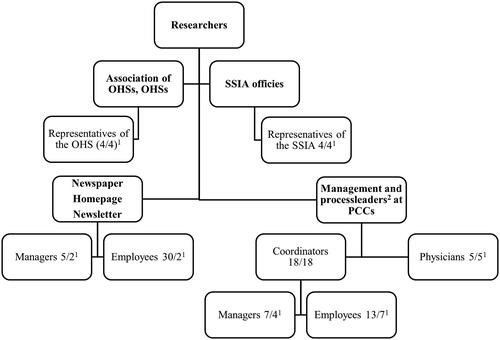

Recruitment of employees, managers, coordinators, SSIA-officers, and OHS-representatives followed strategic sampling with the eligibility criteria: (1) having participated in a three-party meeting initiated by the healthcare services, and conducted at the PCC, the employee’s workplace, or as a telephone conference, with at least the employee, their manager, and a coordinator present at the three-party meeting, and (2) being able to speak and understand Swedish or English. There were three additional criteria for employees: (1) age 25–65, and (2) ongoing sick leave, or on sick leave for a maximum of 12 weeks in the previous six months due to mild to moderate depression, anxiety, or adjustment disorder. The diagnosis was self-reported. Participants were recruited from three Swedish regions: Västra Götaland, Uppsala, and Stockholm. See for an overview of the recruitment process.

Figure 1. Procedure for the recruitment (n = 46). PCCs: Primary care centres; OHS: Occupational Health Services; SSIA: Swedish social insurance agency. 1Number of contacts, persons who after information from a third party or announcement had agreed to contact the researchers/number of included participants. 2Process leaders are providing operational support to coordinators in their daily work.

Initially, persons in managerial positions and process leaders at PCCs in the three regions were informed about the study and asked to contact coordinators and physicians. Coordinators, in turn, forwarded information about the study to managers and employees. Representatives of the SSIA and the OHS were contacted through their organizations. Eligible persons expressed their interest to participate to the principal investigator EBB or co-author TH. Those who expressed an interest in participating were provided with information before consent by EBB or TH. Three employees declined to participate due to the severity of their CMD symptoms and the perceived sensitivity of speaking about their work situation. A further three employees and three managers did not reply when contacted by the research team. Therefore, further steps were taken to increase the recruitment rate via announcements in different media, and additionally, two employees and two managers met the eligibility criteria and were included.

The sample consisted of 46 individuals (see and for characteristics of the sample). Four coordinators worked full-time in their coordinating role; others combined the role with being a process leader, being in a managerial position, or in their healthcare profession. Eight had formal coordinator training (about 7.5 credits). The physicians were employed as general practitioners or trained to become general practitioners. They represented different PCCs, located in urban and suburban areas of Region Västra Götaland. The managers were chief executive officers or human resource specialists responsible for rehabilitation. The employees were 25–61 years of age, seven had returned to part-time work and two were receiving full-time sick leave benefits.

Table 1. Professional stakeholders (n = 37), characteristics and type of interview.

Table 2. Employees on sick leave due to common mental disorders (CMDs) (n = 9), characteristics and type of interview.

Data collection

In total, 41 semi-structured individual interviews and one focus group interview were conducted. The interviews were held face-to-face or by telephone between June 2018 and December 2019 and they lasted 20–60 min. They were conducted by the EBB and TH with previous experience in performing qualitative interviews [Citation26]. If a face-to-face interview was not possible due to personal reasons or geographical distance, telephone interviews were offered. In the overall project [Citation26], three interview guides were developed for interviews with the: (1) employee, (2) manager, and (3) representatives from primary health care services, SSIA, and OHS. Each interview guide consisted of two parts, barriers of and facilitators to the coordination of RTW, and ethical aspects of the coordination. Examples of questions were: (employees) how did you experience being offered coordination; (managers) how was your employee’s right to self-determination taken into account in the contact with you in coordination; (representatives from the primary health care services, SSIA, and OHS) how should you describe your role at the three-party meeting with the employee and manager? The interview guides are available elsewhere [Citation26].

Because of their workload, individual interviews with physicians were deemed by their managers to be impossible. In dialogue with the physicians and their managers, a focus group interview was considered a feasible option. A focus group during the physicians’ administrative time was more appealing to them because of the possibility of interactive discussions around RTW. Because the focus group was conducted as the last interview and because the physicians’ experiences, which otherwise would have been lacking, were considered important, the use of a focus group interview was decided to be the best option. The focus group was facilitated by a moderator and an assistant moderator (EBB) and lasted 90 min. At the start of all interviews, the interviewee/s were informed about the confidentiality procedures, the purpose of the interview, and the definition of coordination of the study. All interviews were recorded digitally, telephone interviews using the Tape a Call application, and transcribed verbatim. Due to technical problems, one individual interview was documented in writing by EBB. The accuracy of the notes was checked with the interviewee at the end of the interview session. For transparency, all participants were offered the opportunity to review their interview transcripts. None of the participants who received their transcripts suggested any changes.

Data analysis

The analysis follows the six phases of thematic analysis by Braun and Clark. Their thematic approach is flexible in terms of theory informing analysis and focuses on common patterns in the data [Citation23]. The focus of the analysis was values and norms of healthcare and the possible impact/-s the coordination of RTW has on the employee who is on sick leave due to CMDs. However, the entire interview transcripts were included in the analysis. The N-Vivo 11 software was used to organize the data. In the first phase (familiarizing yourself with your data), LH and LS read the interview transcripts. In the second phase (generating initial codes), features of the data set pertaining to ethical aspects (autonomy and privacy, resources and organization, and professional values) included in Swedish healthcare legislation and the ethical framework developed by Swedish authorities [Citation15] were identified using initial codes. Coding thus focused on ethical issues chosen for the study and that can arise in the coordination of RTW, although with opportunities for expansion with additional inductive coding. For reflexivity during the process of coding, critical discussions were held by three of the co-authors (LH, LS, EBB) regarding the conceptualization of ethical issues and interpretation of patterns in the data. In the third phase (searching for themes), all authors drew on an understanding of compatibility with ethical norms (autonomy and privacy) and structural factors with implications for equality (resources and organization, professional values) visualized in [Citation15]. During phases four (reviewing the themes), five (defining and naming themes), and six (producing the report) the authors moved back and forth in a constant comparative process between the text material, codes, and themes [Citation23]. In this process, all authors were involved and contributed to reviewing whether themes represented the data accurately and that the essence of what each theme represented was clear. In the last phase, data extracts were chosen to represent each theme. The interviews and coding were conducted in Swedish. The data extracts were translated into English by (1) the first author, then (2) reviewed by the last author, and thereafter (3) by a language editor.

Table 3. Overview of themes.

Results

Five themes were identified in the analysis ().

Autonomous decision-making versus the risk of taking over

General prerequisites for the individual to be able to make autonomous decisions are autonomous ability and access to relevant information [Citation30,Citation31]. In this study, employees felt that their autonomous ability could be limited by CMD symptoms and by the complex systems for RTW, including multiple stakeholders and regulations. While coordinated RTW meant that the employee was supported in making autonomous decisions during the RTW-process, it was important for the supportive strategies to avoid paternalism if professional stakeholders took over the decision-making.

Limited autonomous ability was identified in relation to employees’ struggles in understanding and managing the RTW-process. They struggled with understanding their rights and responsibilities and those of others, and having the energy to familiarize themselves with, and manage, legal frameworks. One employee said: “It’s difficult to be ill and at the same time be well enough to try to manage your project.” [ES09] Both the employee and the coordinators exemplified how the coordinator used empowering strategies during their encounters, such as establishing a trusting relationship, providing knowledge translation, helping to identify and prioritize problems, and motivation. In essence, this voiced much of the ideals of shared decision-making. Generally, employees and other stakeholders saw the coordination of RTW as a means of getting employees’ needs met. However, representatives of the OHS and the SSIA raised concerns about situations in which they felt that healthcare professionals looked at the situation primarily from the employee’s perspective. In other words, they were concerned that healthcare professionals lacked the manager’s perspective and acted to protect the employee by hindering contact with the workplace, i.e., the OHS and SSIA identified the risk of paternalism. This was exemplified by one OHS representative:

When the healthcare services step in and …/… protect their patient… I feel they have a one-sided perspective, the patient’s perspective, of what has happened and what their workplace conditions are like. They don’t have the full picture. [OHS1]

In the experience of the OHS and SSIA, a one-sided perspective and paternalism risked discouraging employees from autonomous decision-making. Overall, lacking the workplace perspective could negatively affect decision-making in the RTW-process. Thus, while coordinated RTW strengthened the employee’s ability to make autonomous decisions it was also necessary to find a balance between different support strategies by considering the views of other parties. Hence, even if voicing ideals of shared decision-making, there were examples of a lack of clear roles and objectives for different stakeholders in this sharing.

Employee rights versus restrictions to self-determination

An important norm in healthcare and society at large is the individual’s right to make decisions about their own life [Citation30,Citation32]. An ethical issue arises here because the employee’s self-determination in the RTW-process was restricted by the systems and organizations involved in RTW, such as legal systems and their workplace. Instead of facilitating full self-determination for the employee, the coordination of RTW was a mediator to establish a balance between individual rights and these restrictions.

It was customary to obtain the informed consent of the employee before initiating coordination of RTW. However, the employee’s self-determination through the RTW-process was restricted by the legal frameworks for sick leave. For example, the individual could discuss their symptoms with the physician, and how they perceived the symptoms affecting their workability. Still, the employee could not make decisions about eligibility for sick leave or length of sick leave due to regulations and statutory time-limits for assessing eligibility for sick leave. In addition, the employee on sick leave was obligated to actively participate in the RTW-process. One OHS representative said:

Then of course it’s their decision, and if they don’t want to participate, they don’t want to; but you are obliged to participate in your rehabilitation. Sometimes the rehabilitation process is terminated because the individual isn’t participating. It’s rare, but if it does happen—then it can lead to legal sanctions. [OHS2]

Moreover, the manager’s ability to accommodate the needs of the employee (or interest in doing so) is sometimes limited. When the employee returned to work in a gradual RTW-process, symptoms or difficulties could still be present and workability limited, even though the employee was given a salary for their part-time work. The manager was responsible to find solutions for the employee returning to work, their co-workers, and for the operation. Some managers expressed that it could be difficult to find adjustments or alternative placements for an employee within the organization and consider other interests. One manager explained: “Sometimes the doctor thinks, yes, it’s a good idea to make some small adjustments, but that’s not so easy because it affects co-workers…” [M06] Hence, the manager’s autonomy and interests restricted their ability to meet the employee’s wishes and needs in the RTW-process. Information and dialogue were necessary to achieve a balance between the autonomy of the employee and the manager. Through increased awareness of the RTW-process and each other’s needs and obligations, it was possible to reach a consensus around a plan for RTW. In this way, the three-party meeting could facilitate shared decision-making.

Respect for the employee’s privacy versus stakeholders’ interests

In Swedish healthcare, there is a high level of protection of individual privacy when handling sensitive information [Citation33,Citation34]. An ethical issue arises here related to the potential tension between the manager’s interest in obtaining relevant information about the employee’s situation and the employee’s right to privacy. Given the responsibility of a healthcare professional to protect the individual’s privacy, they cannot exchange information with the employer without the employee’s consent.

Openness about the employee’s health status was experienced by the managers as facilitating their understanding of how the CMD affected the employee at work and therefore guiding them in providing accommodations. However, sharing sensitive information about a CMD with the manager can make the employee feel vulnerable or generate a conflict with the employee’s view of themselves and how they feel others view them at work. For these reasons, uncertainty about what information the health professional might share during the three-party meetings was stressful for the employee.

You expose yourself in a way. Makes you vulnerable, and that’s my problem with it—I’m an achiever that would preferably… maybe be evaluated based on what I do, or I’ve always identified myself with what I do…/… you paint a sort of this-is-the-private-me and this-is-the-work-me picture, and I want to present that work-me first. [ES08]

In contrast to the above citation, some employees had a more unrestrained approach and were prepared to openly share information. The managers emphasized their need for work-related information and felt that exhaustive information about the employee’s health status was not necessary. Achieving the right balance of disclosure was delicate. A certain “give and take” to help both protect and if relevant, expand the individual’s privacy limits was therefore necessary. One coordinator explained:

Before the meeting, I usually say briefly that it’s important for your manager to know, yet of course, it’s your decision, you don’t have to tell them everything, you choose what you want to tell them. But at the same time, you must be aware that it affects the manager’s ability to understand and be able to do something about it. [C10]

Representatives of the OHS and the SSIA also gave examples of this “give and take” in supporting the individual in decision-making about disclosure [Citation35]. A preparatory conversation could help to distinguish the information of a private character from work-related issues before the three-party meeting and empower the employees to speak for themselves. During the meeting, strategies were for health care professionals to share only general information about CMDs and to keep a focus on work-related issues. Awareness of the delicacy of information exchange and how the privacy of the employee can be balanced against other relevant interests was essential in the different stages of RTW coordination.

Risk of unequal inclusion due to insufficient organizational structure and resources

A fundamental principle of Swedish healthcare is that patients with similar conditions should have equal access to healthcare interventions [Citation36,Citation37]. The ethical issue which arises here is related to the fact that the inclusion of patients in coordinated RTW varied between PCCs. This in turn was related to a lack of resources and structure. Lack of or arbitrary criteria for inclusion presented a risk of unequal access to coordinated RTW for persons with CMDs.

To ensure the systematic inclusion of employees in coordinated RTW, some PCCs used medical records to screen for and contact employees on sick leave, irrespective of diagnosis. However, in most cases, employees were referred to a coordinator at the PCC by physicians. At several PCCs, referrals for coordination could also be made by other colleagues or directly by the employee or the manager. Overall, referrals and the decision about whether an employee should be offered coordination services tended to vary according to the decision maker’s awareness of, and attitude to, coordinator services. One coordinator said:

… it’s only the doctors who see the need for coordinators’ rehab measures; it’s only the patients who see those doctors who get the support. Sometimes I can pick up cases from the statistics, from our medical record, but there are so many patients on sick leave that I can’t always do that. [C02]

Because of a lack of resources, many coordinators found it difficult to make systematic use of medical records. Similarly, the physicians reflected on the lack of time available to carry out the proper assessments to make referrals. They also noted differing attitudes among physicians. One said: “Sometimes I feel that we doctors, as a group, differ a little in how we deal with or take care of that resource [coordinator]. Some of us feel we haven’t got time, aren’t so interested.” [P02] Moreover, due to limited resources, coordination of RTW could not be offered to all persons on sick leave due to CMDs. Some followed regionally developed criteria for priority setting, i.e., employees with less than 180 days of sick leave and 20–40 years of age. Others followed their tacit knowledge of which employees needed support. Patients on long-term sick leave due to CMDs were rarely included. Thus, unfair, or arbitrary inclusion criteria gave rise to the risk of unequal access depending on age, employment status, place of residence, or registration with a specific PCC.

Risk of unequal support due to unclear professional roles and responsibilities

The RTW-process involves multiple professional stakeholders whose responsibilities and values are linked to their profession and working context. The ethical issues identified here relate to unclear professional roles and responsibilities, and conflicting professional values between health care professionals’ roles and the roles in RTW-coordination. These unclarities or conflicts can affect stakeholders’ actions throughout the RTW-process and can result in the employee receiving arbitrary or unclear information, and unequal support.

Coordinators lacked a clear description of how their role at the PCC was to be carried out. Moreover, their professional background and employment in healthcare services naturally influenced their professional values. Tensions between their role as coordinator and their professional background could cause moral distress [Citation38]. The uncertainty and lack of clarity felt by many of the coordinators gave rise to the risk of variations in practice. Some favored being a patient representative and using their therapeutic skills in their coordinator role. Others argued for neutrality and a more consultative role. The physicians experienced a similar conflict between their medical role and, for example, sick leave certification. One physician said: “It’s actually a very strange role. Having to set limits [through sick leave certification] and then also comfort, treat, and relieve.” [P04]

The lack of clarity in roles and responsibilities between stakeholders also gave rise to ethical issues in the coordination of RTW. Coordinators and representatives of the SSIA identified certain managers as reluctant to participate in the RTW-process, while the OHS and managers emphasized their difficulties to fulfil their responsibilities. For example, the OHS and managers found it difficult to provide a sufficient RTW-plan if the sick leave certificate was vague, or if the employees were reluctant to involve them in contact with the primary health care services. When the manager lacked information about the employee’s health status, they experienced a responsibility to give support in matters beyond their primary responsibilities, and beyond their competence. Lack of clarity between the primary health care services and the OHS regarding the medical and RTW-support available could also add to conflicts and the risk of employees slipping through the net. Therefore, it was important to clarify roles and responsibilities through an open dialogue between the different stakeholders. One representative from the SSIA said:

Yes, I think that in many cases, after these meetings the managers know what’s at their desk, what responsibilities they have… and the health care also knows a bit about what’s needed from our perspective [regarding sick leave certification] …/… I get information about what the manager can do to adjust, and if it is possible to accommodate for and facilitate the return [to work]. [SSIA 02]

All stakeholders felt that a consensus about RTW for the employee could be facilitated through three-party meetings. In addition, professional networks could help to promote an open dialogue about professional roles and responsibilities in RTW. This could limit the risk of conflicts between professional stakeholders, reduce moral stress, and minimize the risk of unequal coordination of RTW for employees.

Discussion

This study is unique in its focus on the ethical issues that arise in the coordination of RTW for employees on sick leave due to CMDs. Our study identified ethical issues related to restrictions on employee autonomy and risks associated with employee privacy, which were balanced in the coordination of RTW by the use of empowering strategies, shared decision-making, and support in the decision about disclosure. The main ethical issues in our results were the risks of unequal access and unequal support.

The unequal access to the coordination of RTW identified in our study was related to a lack of, or arbitrary criteria for inclusion, and the use of regionally developed inclusion criteria based on length of sick leave and age. In healthcare and welfare systems struggling with resource constraints, prioritization, and rationing are inevitable. In the last few years, there have been strong developments in theories about distributive justice and fairness to handle this challenge [Citation39]. From a utilitarian perspective, prioritizing those with shorter-term sick leave could be warranted for cost-benefit reasons, this is in line with research indicating short-term sick leave as an indicator for stainable RTW [Citation40]. As such, giving priority to employees with shorter sick leave might be a more effective use of resources. However, according to egalitarian theories, there is a strong rationale to prioritize patients with greater needs above patients with lesser needs, all else being equal. According to prioritarian theories, effectiveness should be balanced against needs but greater needs are generally prioritized [Citation41,Citation42]. A potential problem with focusing strictly on the size of the need is that we might end up with fewer resources to spend on healthcare, if people who can return to work and contribute to the economic system are not prioritized. Another problem is that having to wait until the need becomes great enough, might imply generally down-prioritizing preventive work. This seems counter-productive if we want to achieve a healthy population. Hence, most jurisdictions do apply some mix of the above theories in distributing resources, where both the size of need and the overall health outcome of interventions are considered. This is certainly true for Sweden, where considerations of patient needs and effective and equal distribution of health are integral to healthcare legislation.

We also found that some PCCs prioritized employees of younger age. Younger age as a predictor for access to coordinated RTW has also been identified in previous research [Citation10]. While this prioritization might be explained by a predominance of onset of sick leave due to psychiatric diagnoses in the ages 30–39 [Citation2], mental ill-health is obviously not restricted to these ages. According to theories of justice, considerations about age are a complex matter. Utilitarian theories advocate distributing resources to achieve as much health as possible. Lifetime egalitarian theories distribute health evenly throughout human lives in a society, and prioritarian theories advocate that both the severity of the condition and how much health benefit we can achieve should be considered. Utilitarian, lifetime egalitarian and prioritarian theories of justice would likely support age being taken into consideration, but for different reasons. Utilitarian and prioritarian theories would support age being taken into consideration because RTW might imply a greater lifetime gain for younger patients. Egalitarian and prioritarian theories support reference to age since younger people could be in greater need, having to suffer for a longer time if no intervention is provided [Citation41,Citation42]. However, from a Swedish perspective age limits are only acceptable if there is an underlying biological reason [Citation36,Citation43]. To allow factors to be taken into consideration that are not supported by a clear ethical rationale also breaches the principle of formal equality or justice, according to which irrelevant considerations should not be allowed to give rise to different outcomes between cases [Citation32].

The principle of formal equality also relates to the unclear professional roles and responsibilities identified in our and other studies [Citation6–8]. This implies a risk of unequal support for the employee on sick leave. There is, obviously, no acceptable ethical rationale for such differences, regardless of which theory of justice we adhere to. On the one hand, our study shows that an open dialogue among stakeholders, for example, in three-party meetings or professional networks, seemed to encourage boundary work between professions. Boundary work is described as an ongoing and constructive process, and could potentially develop and sustain patterns of collaboration and can increase competence and consensus around the coordination of RTW [Citation44]. On the other hand, the vagueness of the coordinator role [Citation9] presented a risk of drift in coordinator practice and unequal support for the employee. In a narrow understanding of ethics, one might question whether organizational or professional issues should be included in an ethics assessment. However, as organizational ethics and decision science have developed, they have identified structural issues as decisive for whether ethical norms and values are adhered to or not [Citation45,Citation46]. The Swedish ethics framework for assessing health technology, which was used in our study, explicitly specifies that organizational factors, professional roles, and interests must be taken into consideration [Citation15]. In line with our results, Corbiere et al. [Citation5] emphasize the importance of understanding the roles and actions of different stakeholders in the RTW-process and adopting a collaborative approach in RTW to facilitate employee support and communication among stakeholders. They conclude that the coordinator role is important in the RTW-process after sick leave due to CMDs and that this role is less described in research. Clearly defining the role of the coordinator, at policy and organizational levels (for example healthcare), based on the best practice for RTW, would potentially facilitate the necessary boundary work between stakeholders. This might also reduce the risks of unequal support.

Our study shows how the coordinator supported the identification and prioritization of problems and facilitated knowledge translation in the dialogue between the employee and the manager. This is in line with earlier research [Citation9,Citation47]. As such, coordination of RTW could help clarify roles and responsibilities and mediate between the employee’s needs and contextual circumstances (e.g., legal systems and needs of the workplace). In line with Svärd et al. [Citation47], our study found that a preparatory dialogue between the coordinator and the employee (before the three-party meeting) was perceived as beneficial for the RTW-process. Our study shows that a preparatory dialogue could function to support the employee in their decision-making about disclosure before the coordination meeting. Stigma and disclosure are complex problems in the workplace context for people with mental ill-health [Citation35,Citation48]. Toth et al. [Citation35] emphasize that the decision to disclose relates to individual factors, leadership, and social norms present in the organization. A preparatory dialogue where the individual’s situation is explored through contextual circumstances [Citation49], and information about CMDs to the manager in a three-party meeting, could potentially support the employee’s decision and improve manager attitudes. Overall, a balance in coordinated RTW between empathy and respect for the employee’s health status and rights, and dialogue about how RTW is situated at the interface between the employee and context (workplace, regulations, etc.), can potentially raise awareness about restrictions to self-determination and support autonomous decision-making in the RTW-process. Having an open dialogue in a three-party meeting is also part and parcel of shared decision-making, where the ideal is that different parties bring their perspectives to the interaction and end up in a joint decision. Ideally, this might also prevent paternalism—i.e., the healthcare professionals taking over, or protecting the employee, and thus becoming gatekeepers in the RTW-process. Rather, following shared decision-making, each stakeholder is viewed as competent to take part and communicate their perspective.

Further research on ethical issues is warranted and should focus on the specific content and effectiveness of coordinator measures, this can assist in clarifying the coordinator’s professional role and how to conceptualize the interaction in terms of shared decision-making. Further research on ethical issues in the coordination of RTW after sick leave due to CMDs should also explore the role of gender, type of work, and educational level in access to coordination measures.

Methodological considerations

Our study is positioned within empirical and normative dimensions of practice. The empirical approach contributed with a multi-faceted description of ethical issues in the coordination of RTW from the perspective of stakeholders involved in the process [Citation50]. This was facilitated by theoretically grounding the analysis in ethical aspects used in Swedish health care. The strategic sample, with diversity in demographic characteristics and viewpoints on coordination of RTW, was critical to providing rich data [Citation51].

A limitation here pertains to the balance of experiential accounts of different stakeholder groups and the inclusion of Swedish-speaking participants. Equal input from each stakeholder group and a more culturally and linguistically diverse sample would have allowed for a greater breadth of experience. Another limitation is the variety of methods used for data collection. Telephone and face-to-face interviews differ in context and focus group interviews generate data co-constructed among participants. To use a focus group interview was a pragmatic choice to include all stakeholder groups, which otherwise would have been impossible. The focus group included an interactive discussion among physicians, who represent a central stakeholder group in RTW, and contributed to the individual interviews. However, the use of one focus group needs to be considered when interpreting the results.

For trustworthiness, all interviewees were informed about a definition of coordination, the study purpose, and confidentiality procedures. This was important for the interviewees to address the same problem and to establish a setting where the participants felt that they could speak freely [Citation51]. All interviews were conducted with open questions in a private environment. Follow-up questions and prompts were used to obtain rich data and all participants were offered the opportunity to review transcripts. Moreover, the critical discussions held within the interprofessional research team throughout the analysis facilitated reflection for distinguishing between participant meaning and research interpretation [Citation51].

The transferability of research about the coordination of RTW can be limited by the variation in policy and coordinator practices between countries. Detailed descriptions of the healthcare and social insurance systems in this study can guide the assessment of the transferability of the Swedish experience regarding the ethical issues that arise in the coordination of RTW among employees on sick leave due to CMDs to other settings and populations [Citation51].

Conclusion

Our study identified potentially unfair and arbitrary criteria for inclusion and therefore risks of unequal access to the coordination of RTW for the employee on sick leave due to CMDs. The inclusion criteria seemed to breach principles of equality and justice and conflict with Swedish legislation and priority setting. Moreover, the unclear professional roles and responsibilities among stakeholders identified in our study implied risks of unequal support in the coordination of RTW. To ensure justice and fairness it is necessary to be transparent on how to prioritize the coordination of RTW for different patient groups. Clear definitions of the coordinator’s professional role and coordination of RTW could improve competence and awareness about coordination and facilitate the employee’s decision-making throughout the RTW-process. However, the effectiveness of these strategies would need to be evaluated in future studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the individuals who participated in the study, and the primary health care managers and rehabilitation coordinators who recruited eligible participants. We also want to thank Py Andersson Liselius for moderating the focus group.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]. Fit mind, fit job: from evidence to practice in mental health and work. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015.

- The Swedish Social Insurance Agency [SSIA]. Uppföljning av sjukfrånvarons utveckling 2020 [follow up of the development of sickness absence 2020]. Stockholm: Försäkringskassan; 2020.

- OECD E. Union (EU). Health at a glance: Europe 2018: State of health in the EU cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2018.

- Loisel P, Buchbinder R, Hazard R, et al. Prevention of work disability due to musculoskeletal disorders: the challenge of implementing evidence. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):507–524.

- Corbiere M, Mazaniello-Chezol M, Bastien MF, et al. Stakeholders’ role and actions in the return-to-work process of workers on Sick-Leave due to common mental disorders: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2020;30(3):381–419.

- Russell E, Kosny A. Communication and collaboration among return-to-work stakeholders. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(22):2630–2639.

- Liukko J, Kuuva N. Cooperation of return-to-work professionals: the challenges of multi-actor work disability management. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(15):1466–1473.

- Ståhl C, Svensson T, Petersson G, et al. The work ability divide: holistic and reductionistic approaches in swedish interdisciplinary rehabilitation teams. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(3):264–273.

- Holmlund L, Hellman T, Engblom M, et al. Coordination of return-to-work for employees on sick leave due to common mental disorders: facilitators and barriers. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;2020:1–9. Epub ahead of print.

- Skarpaas LS, Haveraaen LA, Smastuen MC, et al. Horizontal return to work coordination was more common in RTW programs than the recommended vertical coordination. The Rapid-RTW cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):759.

- Durand MJ, Nastasia I, Coutu MF, et al. Practices of return-to-work coordinators working in large organizations. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(1):137–147.

- Karkkainen R, Saaranen T, Rasanen K. Return-to-work coordinators’ practices for workers with burnout. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(3):493–502.

- Bohatko-Naismith J, Guest M, James C, et al. Australian general practitioners’ perspective on the role of the workplace return-to-Work coordinator. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(6):502–509.

- Lag om koordineringsinsatser för sjukskrivna patienter [act on coordination measures for persons on sick leave] (SFS:2019:1297). Stockholm: Socialdepartementet; 2019.

- Heintz E, Lintamo L, Hultcrantz M, et al. Framework for systematic identification of ethical aspects of healthcare technologies: the Sbu approach. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2015;31(3):124–130.

- Hofmann B. Toward a procedure for integrating moral issues in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(3):312–318.

- Schandelmaier S, Ebrahim S, Burkhardt SCA, et al. Return to work coordination programmes for work disability: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49760.

- Vogel N, Schandelmaier S, Zumbrunn T, et al. Return-to-work coordination programmes for improving return to work in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3(3):CD011618.

- Li W, Wolbring G. Analysis of engagement between ethics and return-to-work discourses in respective academic literature. Work. 2019;64(1):3–19.

- Ståhl C, MacEachen E, Lippel K. Ethical perspectives in work disability prevention and return to work: toward a common vocabulary for analyzing stakeholders’ actions and interactions. J Bus Ethics. 2014;120(2):237–250.

- European network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA). EUnetHTA Joint Action 2, Work Package 8. HTA Core Model® version 3.0 (Pdf). 2016 [cited 2021 Oct 12]. Available from: http://www.eunethta.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/HTACoreModel3.0-1.pdf.

- Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering [Swedish agency for health technology assessment and assessment of social services]. Implementeringsstöd för psykiatrisk evidens i primärvården: en systematisk litteraturöversikt [implementation of psychiatric guidelines and evidence-based knowledge in the primary care sector]. Stockholm: SBU; 2012.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589–597.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357.

- Björk Brämberg E, Sandman L, Hellman T, et al. Facilitators, barriers and ethical values related to the coordination of return-to-work among employees on sick leave due to common mental disorders: a protocol for a qualitative study (the CORE-project). BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e032463. 17

- Socialförsäkringsbalk [Social Insurance code] (SFS 2010:110). Stockholm: Socialdepartementet; 2010.

- Arbetsmiljölagen [Work Environment Act] (SFS 1977:1160). Stockholm: Arbetsmarknadsdepartementet; 1977.

- Hälso- och sjukvårdsförvaltningen. Lägre sjukskrivning med rehabkoordinator: utvärdering och utveckling av rehabkoordinator för patienter med långvarig smärta och/eller lätt medelsvår psykisk ohälsa i Stockholms läns landsting. Stockholm: Stockholms läns landsting; 2018.

- Patientlag [Patient Act] (SFS: 2014:821). Stockholm: Socialdeparementet; 2014.

- Juth N. Genetic information – values and rights. The morality of presymptomatic genetic testing [dissertation]. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg; 2005.

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- Patientdatalag [Patient Data Act] (SFS: 2008:355). Stockholm: Socialdepartementet; 2008.

- General Data Protection Regulation. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC. 2016.

- Toth KE, Yvon F, Villotti P, et al. Disclosure dilemmas: how people with a mental health condition perceive and manage disclosure at work. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;1–11.

- Prioriteringar inom hälso- och sjukvården [Ethical platform for healthcare priority setting] (Proposition 1996/97:60). Stockholm: Socialdepartementet; 1996.

- Hälso- och Sjukvårdslag [The Health and Medical Services Act] (SFS 2017:30). Stockholm: Socialdepartementet; 2017.

- Kalvemark S, Hoglund AT, Hansson MG, et al. Living with conflicts-ethical dilemmas and moral distress in the health care system. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(6):1075–1084.

- Bognar G. The ethics of healthcare rationing: an introduction. London: Routledge; 2014.

- Etuknwa A, Daniels K, Eib C. Sustainable return to work: a systematic review focusing on personal and social factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2019;29(4):679–700.

- Parfit D. Equality or priority? In: Clayton MWA, editor. The ideal of equality. Basingstoke: Palgrave; 2002. p. 81–125.

- Hirose I. Egalitarianism and prioritarianism. In: Brooks T, editor. New waves in ethics. Basingstoke: McMillan; 2011. p. 88–107.

- Diskrimineringslag [Discrimination Act] (2008:567). Stockholm: Arbetsmarknadsdepartementet; 2008.

- Langley A, Lindberg K, Mork BE, et al. Boundary work among groups, occupations, and organizations: from cartography to process. ANNALS. 2019;13(2):704–736.

- Kahneman D. Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2011.

- Johnson CE. Organizational ethics – a practical approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.; 2018.

- Svärd V, Friberg E, Azad A. How people with multimorbidity and psychosocial difficulties experience support by rehabilitation coordinators during sickness absence. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:1245–1257.

- Brouwers E. Social stigma is an underestimated contributing factor to unemployment in people with mental illness or mental health issues: position paper and future directions. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):36.

- Holmlund. Return to work: Exploring paths toward work after spinal cord injury and designing a rehabilitation intervention [dissertation]. Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet; 2019.

- Davies R, Ives J, Dunn M. A systematic review of empirical bioethics methodologies. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:15.

- Williams EN, Morrow SL. Achieving trustworthiness in qualitative research: a pan-paradigmatic perspective. Psychother Res. 2009;19(4–5):576–582.