Abstract

Purpose

To review the feasibility, acceptability, and effects of physiotherapy when delivered remotely.

Materials and methods

CINAHL, MEDLINE, EBM Reviews, and Cochrane Library databases (January 2015–February 2022) were searched and screened for papers (of any design) investigating remote physiotherapy. Data were extracted by two independent raters. Methodological quality of the identified papers was not assessed. Thematic content analysis drew out the key issues.

Results

Forty-one papers (including nine systemic reviews and six with meta-analyses) were selected involving musculoskeletal, stroke and neurological, pulmonary, and cardiac conditions. The most commonly delivered intervention was remote exercise provision, usually following assessment which was completed in-person. All studies, which assessed it, found that remote physiotherapy was comparably effective to in-person delivery at lower cost. Patient satisfaction was high, they found remote physiotherapy to be more accessible and convenient. It boosted confidence and motivation by reminding patients when and how to exercise but adherence was mixed. No adverse events were reported. Barriers related to access to the technology; technical problems and concerns about therapists’ workload.

Conclusions

Remote physiotherapy is safe, feasible, and acceptable to patients. Its effects are comparable with traditional care at lower cost.

Remote physiotherapy is safe, feasible, and acceptable to patients with comparable effects to in-person care.

Remote delivery increases access to physiotherapy especially for those who cannot travel to a treatment facility whether due to distance or disability.

Remote physiotherapy may increase adherence to exercise by reminding patients when and how to exercise.

Remote physiotherapy does not suit everyone, thus a hybrid system with both in-person and remote delivery may be most effective.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged health care professionals to rapidly change the care they provide and how it is provided. In-patient services were redeploying staff to expanded acute care; patients were discharged earlier to reduce risk of infection and to expand capacity for acute care. Out-patient- and community-based services were often closed and staff redeployed to in-patient care. However, there was also a desire to continue with “business as usual” where possible and many services rapidly started to deliver care remotely without face-to-face contact. We defined remote physiotherapy as those delivered using technologies such as the telephone, video conferencing, apps and web-based systems, rather than in-person [Citation1,Citation2]. With so many changes, which were often introduced under urgent pressure of time and other demands, it is important not to “reinvent the wheel” but use pre-existing resources and evidence. Remote physiotherapy is not new, it has been an area of interest over recent years, particularly in remote and rural areas [Citation3–5] and as a way to triage assessment and management in high volume musculoskeletal services [Citation6–8]. As part of a project to evaluate the implementation of remotely delivered physiotherapy in response to the COVID pandemic, we undertook a scoping review to explore the evidence-base for physiotherapy delivered remotely. As our interest was in implementation of remote physiotherapy as well as its effectiveness, our objectives were to investigate the evidence for outcomes, and feasibility and acceptability in terms of patient satisfaction; advantages and facilitators; adherence; safety and barriers to implementation.

Method

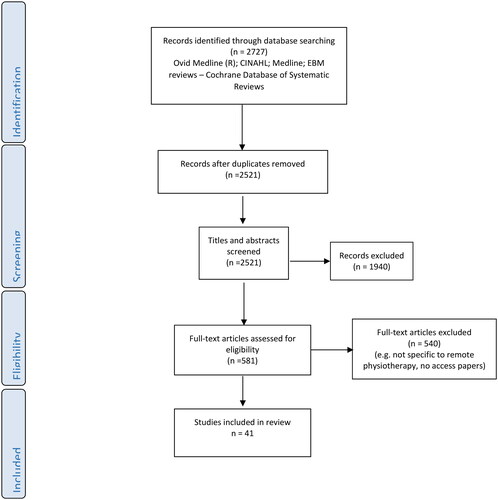

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) scoping review guidelines [Citation9,Citation10] were used as a framework for the review. The review was registered with Open Science Framework (http://osf.io/up62r/). Three electronic databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane library) were searched using key words relating to physiotherapy, remote delivery and experiences or outcomes (). We selected primary research studies or systematic reviews of any design in English which investigated delivery of remote physiotherapy from 2015 (to ensure currency) to February 2022. We excluded studies which delivered electronic treatment in clinic (such as virtual reality); interventions which were not delivered specifically by physiotherapists (e.g., nurse-led cardiac care/rehabilitation); or those which did not examine the effects of remote physiotherapy, such as studies to develop technologies or studies of support to promote exercise after discharge from rehabilitation. Titles, abstracts, and then full text were independently screened by two of the authors against the selection criteria. Reference lists of selected papers were also screened for any other papers which met the selection criteria.

Table 1. Search terms.

Details of the selected papers were extracted and tabulated according to the condition being treated. In keeping with the scoping review approach, the methodological quality of the selected papers was not assessed. Then thematic content analysis was undertaken. Two of the authors independently reviewed each paper and identified and tabulated content regarding each objective (outcomes, feasibility, and acceptability of implementing remote physiotherapy. They then independently coded the material collated under each theme into categories and sub-categories before meeting to revise and iteratively consolidate the information therein. Any differences in interpretation were resolved through discussion.

Results

A total of 2727 papers were identified through the searches. After duplicates were removed and titles and abstracts screened, 540 papers were downloaded for full text screening, with a final 41 papers included in the review [Citation11–57] (). Musculoskeletal problems were the most common condition addressed (n = 13, [Citation11–22]). Nine papers covered stroke and neurological rehabilitation [Citation23–31]; 12 pulmonary disease [Citation33–44], 6 looked at cardiac rehabilitation [Citation45–50], and 8 looked at generic physiotherapy rather than a specific condition [Citation50–57]. A range of study designs were used; with nine systematic reviews [Citation11,Citation12,Citation23–25,Citation32,Citation33,Citation44,Citation45]. Six of which found sufficiently homogenous data to perform meta-analysis [Citation12,Citation24,Citation25,Citation33,Citation34,Citation45]. There were also eight randomised controlled trials [Citation13–15,Citation26,Citation34–37] and two clinical controlled trials [Citation16,Citation46]. Fourteen were cohort studies [Citation17,Citation18,Citation28,Citation29,Citation38–41,Citation46, Citation54] and two were service evaluations [Citation27,Citation50]. There were five surveys [Citation19,Citation20,Citation42,Citation46,Citation48] using questionnaires or mixed methods, one focus group study [Citation43] and four semi-structured interviews [Citation21,Citation22,Citation30,Citation31]. Further details of the selected studies are found in .

Table 2. Selected studies of musculoskeletal conditions.

Table 3. Selected studies of stroke and neurological conditions.

Table 4. Selected studies of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 5. Selected studies of cardiac conditions.

Table 6. Selected studies of physiotherapy.

Methodological quality was not formally assessed in this review, but it was noted that sample sizes were generally small and power calculations seldom used. Furthermore, randomisation processes and concealment of allocation were often poorly reported in randomised controlled trials. Control interventions were traditional in-person physiotherapy whether an out-patient department/clinic or home-based therapy.

The interventions studied were described in several different ways including tele-rehabilitation; tele-care; remote care, e-health, and m-health. For ease of comprehension and consistency, we have referred to the interventions collectively as remote physiotherapy. Unsurprisingly a wide range of technologies were used. The most common were simple technologies such has such as videoconferencing or mobile phones to deliver the same care as would be delivered in-person (n = 22, [Citation18,Citation27,Citation31–37,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43–46,Citation50–55]) and these were also the focus of the systematic reviews [Citation12,Citation23–25]. The most common system developed specifically to deliver physiotherapy involved videos demonstrating patients’ exercise programmes uploaded to a web-site or app (n = 9, [Citation13,Citation15,Citation17,Citation21,Citation26,Citation30,Citation38,Citation44,Citation47]). One system created an avatar to demonstrate the exercises [Citation14]. These were generally asynchronous. Some also monitored adherence and performance of the exercise which was feedback to the patient and/or therapist. Direct contact with the therapist was usually via a “visit” using video conferencing when the exercise regimen was revised, and self-management advice or any other support given. A few of these interactive systems incorporated coaching, psychological support or behavioural change elements as well as exercise. In some systems, equipment such as body-worn movement sensors, heart rate monitors, or pulse oximetres were used to give synchronous feedback on performance to the patient and/or therapist. Further details of the interventions are found in .

As befits the wide ranging aims of the selected studies, the concepts and outcomes investigated were very varied, as were the measurement tools used. The aims of the selected studies could be broadly categorised as investigating the feasibility and acceptability of remote physiotherapy and its effects. Each of these are considered in detail subsequently.

The feasibility and acceptability of remote physiotherapy

Feasibility and acceptability of remote physiotherapy were the most frequent objectives of the selected studies (n = 36), four of which were systematic reviews in which feasibility and acceptability were secondary outcomes [Citation12,Citation25,Citation31,Citation45] with the effects of remote physiotherapy as the primary outcome. Four randomised controlled trials assessed feasibility and/or acceptability [Citation14,Citation15,Citation26,Citation27]. Ten cohort studies [Citation16–18,Citation28,Citation38–41,Citation45,Citation46], four implementation studies [Citation27,Citation48,Citation50,Citation52], seven surveys [Citation20,Citation42,Citation47,Citation51,Citation53,–Citation55], and four interview [Citation19,Citation22,Citation30,Citation31] studies investigated feasibility and/or acceptability, all as the primary objective. Three papers [Citation20,Citation22,Citation42] investigated the views of potential users (i.e., patients and therapists without experience of it), while all other studies involved people with experience of remote physiotherapy.

Feasibility and acceptability are broad concepts which we categorised as patient satisfaction, the advantages/facilitators of remote physiotherapy, barriers to using remote physiotherapy, adherence, and safety.

Patient satisfaction. Sixteen studies assessed patient satisfaction [Citation11–13,Citation15,Citation25–29,Citation40,Citation41,Citation43,Citation45,Citation47,Citation50,Citation51]. Although a variety of quantitative and qualitative measures were used, all, including systematic reviews, reported that patient satisfaction was positive—described as high, very high, or excellent. One study observed that there was no difference in satisfaction between groups receiving remote or traditional physiotherapy [Citation13].

The advantages or facilitators of remote physiotherapy was investigated in eight studies [Citation15,Citation19,Citation21–24,Citation30,Citation31,Citation42,Citation45,Citation47,Citation50,Citation53]. The biggest advantage highlighted was that remote physiotherapy increased access to physiotherapy for those who could not travel for in-person treatment, whether because of the distances involved or the degree of disability. Furthermore, patients found remote physiotherapy more flexible and convenient than traditional delivery, enabling them to access therapy when it was convenient and fitted around work or other commitments. This reduced their costs with less travel and absence from work [Citation19,Citation22,Citation24,Citation30,Citation39]. The other main advantage of remote physiotherapy was that it supported patients to perform their exercises [Citation15,Citation21,Citation45,Citation47] through demonstrations of the exercises. For this reason, remote physiotherapy exercise platforms were preferred over paper handouts [Citation21]. Exercise reminders and reinforcement messages were also useful, if individualised to fit in with the patient’s daily routine to promote engagement and motivation to exercise [Citation15,Citation21,Citation31,Citation38,Citation39,Citation45]. Other features that users found useful were feedback on performance and adherence for both patients and therapists and interaction with a “real” therapist [Citation15,Citation21,Citation42]. In several studies, patients highlighted that the remote physiotherapy platform supplemented rather than replaced contact with a physiotherapist but enhanced the therapeutic relationship by creating an interactive and ongoing connection between them and their physiotherapist [Citation15,Citation21,Citation31,Citation45,Citation47]. These views were broadly echoed by potential users of remote physiotherapy—patients and therapists in a traditional pulmonary rehabilitation services were asked about their interest in, and views of remote physiotherapy [Citation19,Citation42]. They both highlighted that the social aspect of rehabilitation was important and wanted a remote system to maintain this, for example, through group exercise and education sessions and opportunities to interact with each other and the physiotherapists. Studies of patients’ experience of using remote physiotherapy reported that patients reported enhanced self-efficacy, confidence and motivation to exercise when using remote physiotherapy, enabled them to monitor their condition and progress, using heart rate monitors and pulse oximetres, for example, and it also increased their confidence to self-manage their condition [Citation26,Citation38,Citation39,Citation44,Citation45].

Adherence to remote physiotherapy regimen was addressed in eleven studies using a variety of measures [Citation15,Citation17,Citation25–27,Citation32,Citation34,Citation36–39]. Overall, adherence was mixed with some patients hardly exercising or using the remote system at all, and others exercising at or above the prescribed dose. Overall, studies which reported the proportion of patients meeting recommended doses varied from 35–95% (overall, 71%) [Citation17,Citation26,Citation28] with 87–95% of patients completing the programme [Citation17,Citation18,Citation32,Citation46] except one study in which only 57% competed [Citation13]. One study reported much lower uptake of remote exercise sessions and completion of an online symptom diary (56% and 43%, respectively) but this was over a 2-year period [Citation38,Citation39].

Safety of remote physiotherapy (in the form of adverse events) was monitored in seven studies of stroke and pulmonary rehabilitation [Citation24–26,Citation28,Citation32,Citation40,Citation46] including three systematic reviews [Citation24,Citation25,Citation32]. Although all reported that no adverse events occurred, few details about how adverse events were measured/defined or monitored were available.

Barriers (whether perceived or actual) to remote physiotherapy relating to the technology, organisation and the physiotherapists’ workload and skills were reported [Citation18,Citation23,Citation27,Citation30,Citation42,Citation47,Citation50,Citation51, Citation53–55]. Technical barriers included difficulties with setup; connectivity and the interface [Citation18,Citation27,Citation30,Citation51,Citation53,Citation55]. However, few technological problems were reported in the selected studies [Citation18,Citation27,Citation47], and when specifically evaluated satisfaction with the technology was high [Citation18,Citation47]. Organisational barriers to using remote physiotherapy were lack of clarity about the medico-legal/liability situation; licensing and intellectual property ownership; and charging processes and other policies [Citation23,Citation50]. While physiotherapists highlighted the potential impact of using remote physiotherapy on their workload as a barrier if physiotherapists were expected to provide it in additional to in-person care [Citation42]. Lack of familiarity with remote physiotherapy systems and difficulty undertaking patient assessments remotely were further issues [Citation42,Citation54].

The effects of remote physiotherapy

The effects or effectiveness of remote physiotherapy was the objective in 21 studies. Six were systematic reviews [Citation12,Citation24,Citation25,Citation33,Citation34,Citation45], seven were randomised controlled trials [Citation13,Citation14,Citation26,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37] eight were cohort studies [Citation16,Citation29,Citation38–41,Citation45,Citation46]. The outcomes measured tended to reflect the priorities of the clinical group involved. For musculoskeletal conditions, the focus was on joint and muscle impairments; pain and function. For stroke, this was activities of daily living, balance, upper limb function, and health-related quality of life for caregivers and stroke survivors, while for cardiac and pulmonary conditions exercise capacity, physical activity and modifiable risks factors were measured. Regardless of condition, study design, or measures used, remote physiotherapy was found to be effective in that outcome improved, but to a comparable extent to traditional delivery whether measured immediately after the end of treatment or after longer-term follow-up.

Seven studies including five systematic review [Citation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation19,Citation23,Citation24,Citation55] assessed costs, or perceived costs (rather than cost-effectiveness) as a secondary outcome, and reported that remote physiotherapy was less costly than traditional care due to lower therapist input; less travelling and/or fewer hospital re-admissions.

Discussion

This scoping review has indicated that remote physiotherapy is feasible, acceptable and safe, with comparable effectiveness to traditional in-person physiotherapy. Patient satisfaction was high and adherence was mixed. Phase III randomised controlled trials with adequately powered samples are needed to more fully understand the clinical effectiveness of remote physiotherapy. It is noteworthy that the selected studies investigated remote physiotherapy delivered by physiotherapists working specifically to deliver it as part of the research study, rather than alongside all the other aspects of everyday physiotherapy practice. Furthermore, although the care was labelled as “remotely delivered,” only nine studies had no in-person contact at all [Citation13,Citation15,Citation18,Citation21,Citation24–26,Citation28,Citation31]. The remainder involved some combination of in-person assessment, treatment demonstration/initiation or monitoring. These might be considered a “blended” rather than a purely remote approach to care delivery. Therefore, future trials need to use a cluster controlled design and process evaluations to investigate the effectiveness and implementation of remote physiotherapy within everyday practice and to consider the optimal combination(s) of in-person and remote contact for different conditions and types of treatment. The participants in the selected studies were patients and therapists who were sufficiently motivated and invested in remote physiotherapy to participate as there is some suggestion that uptake, satisfaction, and adherence may differ when delivered as part of everyday practice [Citation57–59].

All studies that assessed costs, found remote physiotherapy less costly with less health resource utilisation than traditional physiotherapy. However, the cost-effectiveness has not been addressed which should also be included in future trials.

Patient satisfaction with remote physiotherapy was high. Patients valued the flexibility of remote physiotherapy which could be fitted around other commitments. None of the selected studies directly compared satisfaction with remote physiotherapy with traditional delivery but other studies (which were not selected in this review) have suggested that satisfaction is comparable or higher for remote delivery than for in-person care [Citation58,Citation59]. Future trials should include patients’ satisfaction and experience of traditional physiotherapy delivery as well as remote physiotherapy using mixed methods, to enable a richer, more detailed understanding of the advantages and disadvantages and how services can be optimised.

The biggest advantages of remote physiotherapy from both the patients’ and the therapists’ perspective were that it increased the scope and flexibility of access to therapy. However, the digitally excluded would not have been recruited for these studies. Digital exclusion is linked to social and economic deprivation [Citation60,Citation61] not only in that some patients would be unable to afford the technology or Internet connection but also Internet coverage is often poor in social deprived areas such as remote and inner city locations [Citation62,Citation63]. Furthermore, for physiotherapy, limited language skills, physical, and/or other disabilities may limit patients’ ability to use technologies for remote treatment [Citation62–65]. It is therefore important that traditional delivery remains available for those for whom remote treatment cannot be accessed. Remote physiotherapy systems also need to be suitable for a range of technologies. For example, a mobile (or even landline) phone may be suitable for patients who cannot access or use a web-based system. Patients preferred remote physiotherapy to supplement, rather than replace in-person contact with a therapist [Citation15,Citation21,Citation31,Citation43,Citation45,Citation47]. Thus, a hybrid or blended system, involving both may be most effective and acceptable. Future research needs to consider the exclusion rates for remote physiotherapy in different patient populations and explore ways to overcome them so that physiotherapy services are suitable and acceptable for as many patients as possible.

The other advantage of remote physiotherapy was that patients found systems which demonstrated home exercise plans useful to remind them when and how to exercise, which in turn enhanced adherence and confidence. This is to be welcomed as adherence to physiotherapy home exercise programmes is notoriously patchy and resistant to change [Citation66–68]. Although the mechanisms of increased adherence have not been addressed, patients noted that access to on-going physiotherapy remotely enhanced the patient–therapist relationship, which is important [Citation68].

All the studies that assessed adverse events [Citation24–26,Citation28,Citation32,Citation40,Citation46] reported that no adverse events occurred and concluded that remote physiotherapy is safe. However, it should be noted that few details were provided about how adverse events were defined or monitored. It appears the researchers relied on adverse event reporting processes in research protocols or “clinical incident” procedures used in practice, which focus on serious injurious incidents. Further research or clinical audit is needed to investigate the possible (non-critical/serious) side effects of remote physiotherapy in more detail and to examine the level of risk patients find acceptable.

It is reassuring that no adverse events were reported, as health care professionals have expressed concerns about patient safety if they are not physically present to assist a patient [Citation17,Citation25], of “missing something” if they do not have physical contact [Citation17,Citation26] and of risks to patient privacy and confidentiality [Citation51,Citation53]. Interestingly physiotherapists concerns about the safety of remote physiotherapy appeared to be less of a problem for physiotherapists with experience of working remotely [Citation25,Citation67,Citation68]. These concerns are likely due to the need for therapists to adapt existing skills (such as using observation and patient questioning rather than “hands on” skills) to assess and treat remotely, and to develop new ones (such as mastering the technology). These needs can increase workload, change established routines, and challenge professionals’ confidence and identity [Citation43,Citation55], all of which may contribute to resistance to implementation. To effectively implement and sustain remote physiotherapy, there needs to be a recognition of the complex and often implicit, personal processes involved as well as sufficient resources (in terms of equipment and infrastructure), specific training and on-going support to problem-solve and build expertise [Citation68,Citation69].

The other main barriers to remote physiotherapy highlighted in this review and echoed elsewhere [Citation67–69] focussed on organisational and administrative factors. However, these may be expected to be expedited by the need to rapidly introduce remote working practice in response to the COVID pandemic [Citation69].

Limitations

This was a scoping review so methodological quality of the selected papers has not been formally assessed. Some of the findings may therefore be at risk of bias and therefore should be treated with caution. This is particularly true for the randomised controlled trials (and their systematic reviews) which were usually underpowered and the randomisation, concealment of allocation and blinding processes were not completed or poorly reported.

We also limited the search to the main databases and papers published since 2015 to ensure currency but this may have excluded relevant or important papers published beforehand. Furthermore, we excluded papers which were not specifically about remote physiotherapy so there may be relevant information from studies of tele-rehabilitation involving a multi-disciplinary team which is relevant to physiotherapy which we missed. However, the selected studies were extensive and findings were consistent so it is unlikely that a wider scope of the search would have changed the results, but merely added to their strength.

Conclusions

Remote physiotherapy is safe, feasible, and acceptable to patients with comparable effects to in-person care. Remote delivery increases access to physiotherapy especially for those who cannot travel to a treatment facility whether doe to distance or disability. Remote physiotherapy may increase adherence to exercise by reminding patients when and how to exercise. However, it does not suit everyone, thus a hybrid system with both in-person and remote delivery may be most effective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bettger JP, Thoumi A, Marquevich V, et al. COVID-19: maintaining essential rehabilitation services across the care continuum. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5):e002670.

- Adhikari SP, Dev R, Sandborgh M. Alternatives to routinely used physiotherapy interventions for achieving maximum patients’ benefits and minimising therapists’ exposure in treatment of COVID-19–a commentary. Europ J Physioth. 2020;22(6):373–378.

- Russell TG. Physical rehabilitation using telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13(5):217–220.

- Booth S, Kendall M. Benefits and challenges of providing transitional rehabilitation services to people with spinal cord injury from regional, rural and remote locations. Aust J Rural Health. 2007;15(3):172–178.

- Field PE, Franklin RC, Barker RN, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation services for people in rural and remote areas: an integrative literature review. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18(4):4738.

- Taylor S, Ellis I, Gallagher M. Patient satisfaction with a new physiotherapy telephone service for back pain patients. Physiotherapy. 2002;88(11):645–657.

- Joseph C, Morrissey D, Abdur-Rahman M, et al. Musculoskeletal triage: a mixed methods study, integrating systematic review with expert and patient perspectives. Physiotherapy. 2014;100(4):277–289.

- Enock L, Saad M, McLean S. Is telephone triage an effective and feasible form of treatment within physiotherapy outpatient settings? A systematic review. Int J Ther Rehab. 2014;21(Sup7):S2–S3.

- Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Grona SL, Bath B, Busch A, et al. Use of videoconferencing for physical therapy in people with musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(5):341–355.

- Shukla H, Nair SR, Thakker D. Role of telerehabilitation in patients following total knee arthroplasty: evidence from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(2):339–346.

- Bini SA, Mahajan J. Clinical outcomes of remote asynchronous telerehabilitation are equivalent to traditional therapy following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized control study. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(2):239–247.

- Bettger JP, Green CL, Holmes DN, et al. Effects of virtual exercise rehabilitation in-home therapy compared with traditional care after total knee arthroplasty: VERITAS, a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Jt Surg. 2020;102(2):101–109.

- Levinger P, Hallam K, Fraser D, et al. A novel web-support intervention to promote recovery following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;27:29–37.

- Correia FD, Nogueira A, Magalhães I, et al. Home-based rehabilitation with a novel digital biofeedback system versus conventional in-person rehabilitation after total knee replacement: a feasibility study. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–2.

- Malliaras P, Merolli M, Williams CM, et al. It’s not hands-on therapy, so it’s very limited’: Telehealth use and views among allied health clinicians during the coronavirus pandemic. Musculosk Sci Pract. 2021;52:102340.

- Hoogland J, Wijnen A, Munsterman T, et al. Feasibility and patient experience of a home-based rehabilitation program driven by a tablet app and mobility monitoring for patients after a total hip arthroplasty. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(1):e10342.

- Boissy P, Tousignant M, Moffet H, et al. Conditions of use, reliability, and quality of audio/video-mediated communications during in-home rehabilitation tele-treatment for post knee arthroplasty. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(8):637–649.

- Cottrell MA, Hill AJ, O'Leary SP, et al. Patients are willing to use telehealth for the multidisciplinary management of chronic musculoskeletal conditions: a cross-sectional survey. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(7):445–452.

- Martinez de la Cal J, Fernandez-Sanchez M, Mataran-Penarrocha GA, et al. Physical therapists’ opinion of E-Health treatment of chronic low back pain. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2021 02;18(4):16–19.

- Abramsky H, Kaur P, Robitaille M, et al. Patients’ perspectives on and experiences of home exercise programmes delivered with a mobile application. Physiother Can. 2018;70(2):171–178.

- Tchero H, Tabue-Teguo M, Lannuzel A, et al. Telerehabilitation for stroke survivors: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(10):e10867.

- Laver KE, Adey-Wakeling Z, Crotty M, et al. Telerehabilitation services for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1:CD010255.

- Ramage ER, Fini N, Lynch EA, et al. Look before you leap: Interventions supervised via telehealth involving activities in weight-bearing or standing positions for people after stroke-a scoping review. Phys Ther. 2021;101(6):pzab073.

- Burridge JH, Lee AC, Turk R, et al. Telehealth, wearable sensors, and the internet: will they improve stroke outcomes through increased intensity of therapy, motivation, and adherence to rehabilitation programs? J Neurologic Phys Ther. 2017;41:S32–S38.

- Yang CL, Waterson S, Eng JJ. Implementation and evaluation of the virtual graded repetitive arm supplementary program (GRASP) for individuals with stroke during the COVID-19 pandemic and Beyond. Phys Ther. 2021;101(6):pzab083.

- Held JP, Ferrer B, Mainetti R, et al. Autonomous rehabilitation at stroke patients’ home for balance and gait: safety, usability and compliance of a virtual reality system. Europ J Phys Rehab Med. 2018;54(4):545–553.

- Kizony R, Weiss PL, Harel S, et al. Tele-rehabilitation service delivery journey from prototype to robust in-home use. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(15):1532–1540.

- Tyagi S, Lim DS, Ho WH, et al. Acceptance of tele-rehabilitation by stroke patients: perceived barriers and facilitators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(12):2472–2477.e2.

- Muller I, Kirby S, Yardley L. Understanding patient experiences of self-managing chronic dizziness: a qualitative study of booklet-based vestibular rehabilitation, with or without remote support. BMJ Open. 2015;5(5):e007680.

- Cox NS, Dal Corso S, Hansen H, et al. Telerehabilitation for chronic respiratory disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;1:CD013040.

- Bonnevie T, Smondack P, Elkins M, et al. Advanced telehealth technology improves home-based exercise therapy for people with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2021;67(1):27–40.

- Hansen H, Bieler T, Beyer N, et al. Supervised pulmonary tele-rehabilitation versus pulmonary rehabilitation in severe COPD: a randomised multicentre trial. Thorax. 2020;75(5):413–421.

- Godtfredsen N, Frolich A, Bieler T, et al. 12-Months follow-up of pulmonary tele-rehabilitation versus standard pulmonary rehabilitation: a multicentre randomised clinical trial in patients with severe COPD. Respir Med. 2020;172:106129.

- Cerdán-de-Las-Heras J, Balbino F, Løkke A, et al. Effect of a new tele-rehabilitation program versus standard rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JCM. 2021;11(1):11.

- Cerdan-de-Las-Heras J, Balbino F, Lokke A, et al. Tele-rehabilitation program in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-a single-center randomized trial. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2021;18(19):10016.

- Hoaas H, Andreassen HK, Lien LA, et al. Adherence and factors affecting satisfaction in long-term telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):1–4.

- Zanaboni P, Hoaas H, Aarøen Lien L, et al. Long-term exercise maintenance in COPD via telerehabilitation: a two-year pilot study. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23(1):74–82.

- Paneroni M, Colombo F, Papalia A, et al. Is telerehabilitation a safe and viable option for patients with COPD? A feasibility study. COPD: J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2015;12(2):217–225.

- Marquis N, Larivée P, Saey D, et al. In-home pulmonary telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a pre-experimental study on effectiveness, satisfaction, and adherence. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21(11):870–879.

- Inskip JA, Lauscher HN, Li LC, et al. Patient and health care professional perspectives on using telehealth to deliver pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis. 2018;15(1):71–80.

- Knox L, Gemine R, Dunning M, et al. Reflexive thematic analysis exploring stakeholder experiences of virtual pulmonary rehabilitation (VIPAR). BMJ Open Resp Res. 2021;8(1):e000800.

- Rawstorn JC, Gant N, Direito A, et al. Telehealth exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2016;102(15):1183–1192.

- Subedi N, Rawstorn JC, Gao L, et al. Implementation of telerehabilitation interventions for the self-management of cardiovascular disease: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(11):e17957.

- Kikuchi A, Taniguchi T, Nakamoto K, et al. Feasibility of home-based cardiac rehabilitation using an integrated tele-rehabilitation platform in elderly patients with heart failure: a pilot study. J Cardiol. 2021;78(1):66–71.

- Laustsen S, Oestergaard LG, van Tulder M, et al. Telemonitored exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation improves physical capacity and health-related quality of life. J Telemed Telecare. 2020;26(1-2):36–44.

- Rawstorn JC, Gant N, Rolleston A, et al. End users want alternative intervention delivery models: usability and acceptability of the REMOTE-CR exercise-based cardiac telerehabilitation program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(11):2373–2377.

- O'Doherty AF, Humphreys H, Dawkes S, et al. How has technology been used to deliver cardiac rehabilitation during the COVID-19 pandemic? An international cross-sectional survey of healthcare professionals conducted by the BACPR. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4):e046051.

- Miller MJ, Pak SS, Keller DR, et al. Evaluation of pragmatic telehealth physical therapy implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Phys Ther. 2021;101(1):pzaa193.

- Albahrouh SI, Buabbas AJ. Physiotherapists’ perceptions of and willingness to use telerehabilitation in Kuwait during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2021;21(1):122.

- Cox NS, Scrivener K, Holland AE, et al. COVID-19: a feasibility study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102(4):789–795.

- Reynolds A, Awan N, Gallagher P. Physiotherapists’ perspective of telehealth during the Covid-19 pandemic. Int J Med Inform. 2021;156:104613.

- Hall JB, Luechtefeld JT, Woods ML. Adoption of telehealth by pediatric physical therapists during COVID-19: a survey study. Paediatr Phys Ther. 2021;33(4):237–244.

- Hall JB, Woods ML, Luechtefeld JT. Paediatric physical therapy telehealth and COVID-19: Factors, facilitators, and barriers influencing Effectiveness - A. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2021;33(3):112–118.

- MacNeill V, Sanders C, Fitzpatrick R, et al. Experiences of front-line health professionals in the delivery of telehealth: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(624):e401–e407.

- Button K, Nicholas K, Busse M, et al. Integrating self-management support for knee injuries into routine clinical practice: TRAK intervention design and delivery. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;33:53–60.

- Lawford BJ, Delany C, Bennell KL, et al. I was really sceptical…but it worked really well: a qualitative study of patient perceptions of telephone-delivered exercise therapy by physiotherapists for people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018;26(6):741–750.

- Cottrell MA, O'Leary SP, Raymer M, et al. Does tele-rehabilitation result in inferior clinical outcomes compared with in-person care for the management of chronic musculoskeletal spinal conditions in the tertiary hospital setting? A non-randomised pilot clinical trial. J Telemed Telecare. 2021;27(7):444–452.

- Estacio EV, Whittle R, Protheroe J. The digital divide: examining socio-demographic factors associated with health literacy, access and use of internet to seek health information. J Health Psychol. 2019;24(12):1668–1675.

- Mitchell UA, Chebli PG, Ruggiero L, et al. The digital divide in health-related technology use: the significance of race/ethnicity. The Gerontologist. 2019;59(1):6–14.

- Hawley-Hague H, Tacconi C, Mellone S, et al. One-to-one and group-based teleconferencing for falls rehabilitation: usability, acceptability, and feasibility study. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2021;8(1):e19690.

- Jack K, McLean SM, Moffett JK, et al. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15(3):220–228.

- Bassett SF. The assessment of patient adherence to physiotherapy rehabilitation. N Z J Physiother. 2003;31(2):60–66.

- Moore AJ, Holden MA, Foster NE, et al. Therapeutic alliance facilitates adherence to physiotherapy-led exercise and physical activity for older adults with knee pain: a longitudinal qualitative study. J Physiother. 2020;66(1):45–53.

- Mair F, Hiscock J, Beaton S. Understanding factors that inhibit or promote the utilization of telecare in chronic lung disease. Chronic Illn. 2008;4(2):110–117.

- Cottrell MA, Russell TG. Telehealth for musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;48:102193.

- Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, et al. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(1):4–12.

- Fisk M, Livingstone A, Pit SW. Telehealth in the context of COVID-19: changing perspectives in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e19264.