Abstract

Purpose

Psychosocial well-being is key to living well after stroke, but often significantly affected by stroke. Existing understandings consider well-being comes from positive mood, social relationships, self-identity and engagement in meaningful activities. However, these understandings are socioculturally located and not necessarily universally applicable. This qualitative metasynthesis examined how people experience well-being after a stroke in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Material and Methods

This metasynthesis was underpinned by He Awa Whiria (Braided Rivers), a model which prompts researchers to uniquely engage with Māori and non-Māori knowledges. A systematic search identified 18 articles exploring experiences of people with stroke in Aotearoa. Articles were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

We constructed three themes which reflect experiences of well-being: connection within a constellation of relationships, being grounded in one’s enduring and evolving identities, and being at-home in the present whilst (re)visioning the future.

Conclusion

Well-being is multi-faceted. In Aotearoa, it is inherently collective while also deeply personal. Well-being is collectively achieved through connections with self, others, community and culture, and embedded within personal and collective temporal worlds. These rich understandings of well-being can open up different considerations of how well-being is supported by and within stroke services.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Psychosocial well-being is critical for people living with stroke.

Well-being should be a priority in rehabilitation, however people with stroke indicate they do no consistently receive psychosocial support.

It is clear that well-being has strong cultural elements, and understanding what supports well-being in individuals, whānau (those within wider networks who the person with stroke considers important), and wider cultural groups is important.

Supporting whānau is crucial as whānau are core to well-being both during and beyond rehabilitation, and their own well-being is impacted by stroke.

Introduction

Stroke has significant psychosocial impacts. The psychological impacts such as depression and anxiety affect many, with approximately one third of people experiencing depression [Citation1] and one quarter experiencing anxiety [Citation2,Citation3]. These rates are higher for those with aphasia [Citation4,Citation5]. Social impacts see changes in social relationships amongst family and friends. It is not uncommon for people to report reduced social supports and networks, strain within family networks and social isolation [Citation6]. The psychological and social effects are interwoven, with social isolation affecting mood, and vice versa [Citation6,Citation7]. Together, these impact on quality of life [Citation6], engagement in rehabilitation [Citation8], participation in one’s community [Citation9] and stroke outcomes [Citation10]. While the need to consider the psychosocial impacts of stroke has been recognised for decades [Citation11,Citation12], this is not consistently integrated into practice [Citation13]. After stroke, people continue to live with significant psychosocial disability [Citation14]. They report that services fail to acknowledge and support their psychosocial needs [Citation15] and in fact, can exacerbate the psychosocial impacts of stroke [Citation16]. As a result, it is a leading area of unmet need [Citation14,Citation15,Citation17].

An orientation to psychosocial well-being, as opposed to psychosocial impacts or needs, reflects a more positive, strengths-based approach to considering the psychosocial element of stroke and moves us beyond an impairment-based and biomedical orientation [Citation18]. However, what constitutes well-being is not always clear or consistent across the literature or in practice [Citation19]. Some authors have worked to develop more nuanced conceptualisations of psychosocial well-being that are grounded in the experiences of those living with stroke to better inform research and practice. Kirkevold’s work is foundational in this area, suggesting that psychosocial well-being is comprised of four components: a mood of joy and the absence of sadness or emptiness; engagement in meaningful activities beyond oneself; good social relationships and a feeling of loving and being loved; and a strong self-concept with self-acceptance and self-belief [Citation14]. These components resonate with findings in allied areas of ‘living well’ and ‘living successfully’ after stroke which highlight the roles of positive outlook, self-acceptance, sense of identity, hope, meaningful relationships and community participation in well-being [Citation17,Citation20,Citation21]. More comprehensive understandings of psychosocial well-being and what supports well-being, grounded in the lived experience of those impacted by stroke may open up new possibilities for supporting people living with stroke, and ultimately, improved well-being.

Ideas around what constitutes well-being, and the ways in which people describe it, may be socioculturally located [Citation22]. As such, we cannot assume that understandings from one location can be readily transferred to others. This paper seeks to understand psychosocial well-being in Aotearoa New Zealand (referred to as ‘Aotearoa’ in the remainder of this paper). Stroke in Aotearoa is the third most common cause of death and disability, with approximately 9,000 New Zealanders being affected by stroke each year [Citation23]. There are significant disparities in who experiences stroke, when, and what outcomes result. Māori, the Indigenous population are two to three times more likely to be affected by stroke than non-Māori and are on average, 15 years younger than New Zealand European stroke patients at the time of stroke [Citation23,Citation24]. There are decades of research documenting inequitable care practices [Citation25] and outcomes, with Māori experiencing greater disability and higher rates of death post-stroke [Citation25–27], on a background of stroke services which are culturally unresponsive [Citation28,Citation29]. In the context of well-being, relying on international conceptualisations may be problematic. These commonly focus on the individual who experienced stroke, while for Māori, well-being is centred in the collective and is multi-dimensional, including whanaungatanga (kinship relationships), uaratanga (values), tikanga (customs), and broader hauora (health and well-being) [Citation30]. As such, international understandings may be problematic and not entirely applicable in Aotearoa. They may reinforce partial understandings of well-being and perpetuate inequities in care experiences and outcomes in Aotearoa. For services to be culturally responsive and not perpetuate inequities, locally-based understandings of well-being are imperative.

The aim of this qualitative metasynthesis is to understand how people living with stroke in Aotearoa, both Māori and non-Māori, experience psychosocial well-being by exploring existing empirical qualitative research. In doing this qualitative metasynthesis, we seek to develop “more comprehensive and integrated understandings” [Citation31] of psychosocial well-being in our unique geographical and sociocultural context of Aotearoa, to inform research and clinical practice [Citation32], and specifically, to underpin a programme of research to enhance psychosocial care practices and outcomes after stroke in Aotearoa

Materials and Methods

This metasynthesis was undertaken as part of a programme of research which utilises Interpretive Description, a qualitative approach that addresses practice-based questions in ways that generate knowledge that can be readily taken up in practice [Citation31]. Within this paper, we use Qualitative Metasynthesis, an approach to literature review which seeks to generate a critically interpretive account of a body of knowledge, so that a phenomenon can be known “more deeply, more fully, and more convincingly” [Citation33]. Core features include using multiple approaches to identifying included articles, engaging with included papers from a variety of disciplinary and methodological perspectives, asking analytic questions to further interpretation, and the requirement to produce a deeply interpretive account, not simply an aggregation of primary studies, which advances theoretical, conceptual and/or praxis knowledge [Citation32–35]. To honour the context of Aotearoa and Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the agreement of partnership between Māori (the Indigenous people of New Zealand) and representatives of the British Crown, we utilised He Awa Whiria (translated as ‘Braided Rivers’) [Citation36] as a guiding framework to reflect and uphold this relationship as we conducted our metasynthesis. He Awa Whiria prompts researchers to engage uniquely with Māori and non-Māori knowledges; the latter based in western approaches to knowledge generation and interpretation. In He Awa Whiria, we conceptualise each approach to knowledge as a ‘stream’ that has mana (standing) in its own right. The approach, Māori or non-Māori, refers not simply to whether a paper is written about Māori experiences by Māori authors, but importantly, the knowledge system that we draw on in analysing and interpreting the paper for this metasynthesis. We refer to the Māori knowledge stream as the ‘Māori’ stream and the other as the ‘General’ stream. Reflecting the metaphor of braided rivers, we sought to bring each stream of knowledge together at different points through the research process to learn from all experiences, whilst also ensuring that nuance was maintained between streams and they were not collapsed into one. Each stream of knowledge stood in its own right with each informing the final analysis presented in this paper.

Recognising that our positions influence how we engage with, interpret and report data [Citation35–37], the positionality and cultural diversity of our research team was integral in upholding He Awa Whiria. Having Pākehā (non-Māori) (FB and CIR) and Māori (BJW, with affiliations to Ngāti Tūwharetoa) researchers who are experienced clinicians and academics (speech-language therapy, FB; physiotherapy, CIR & BJW) with expertise in stroke care and research, psychosocial well-being and qualitative research (FB), programme evaluation (CIR), Māori health and kaupapa Māori research (BJW), and family members of people with stroke (FB & BJW), supported our approach. He Awa Whiria prompted essential team discussions, regarding our critical consciousness (personal and collective) to ensure responsive processes were maintained and culturally appropriate to each stream.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed in conjunction with a health librarian to identify the relevant literature. The keywords for the search can be found in Appendix A. Searches were conducted in May 2021 in the EBSCO Health databases (CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE, SPORTDiscus), SCOPUS and the Australia/New Zealand Reference Centre. The search was supplemented by reference and citation searching of included articles.

Inclusion criteria

Papers were included in this synthesis if they were: qualitative empirical studies or qualitative reviews OR a mixed-methods study where the qualitative component could be clearly identified; conducted with people who experienced stroke in Aotearoa; considering people’s experiences of psychosocial well-being; published between 1990 and 2021; and published in English. Studies were excluded if they only considered family perceptions of stroke survivor well-being or only considered family well-being after stroke; or if they addressed mixed aetiologies (e.g., traumatic brain injury or other acquired neurological conditions) and it was not possible to identify material specific to those with stroke.

Search process

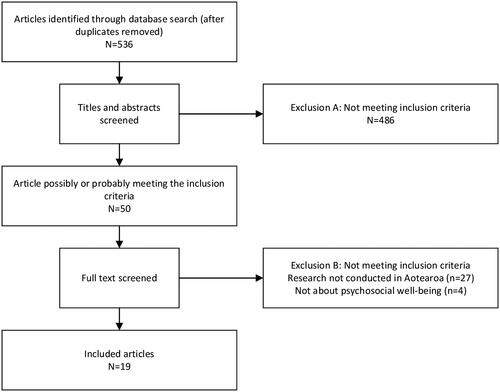

The screening process is depicted in . The search results (n = 536) were downloaded into Endnote after duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by two student reviewers. The full text of the 50 papers which appeared to, or could possibly, meet the inclusion criteria were retrieved and reviewed by these reviewers who identified together if papers met, or possibly met the inclusion criteria. Through discussion with the lead author, the team identified 18 articles met the inclusion criteria (see ), three of which were solely focused on the experiences of Māori [Citation28,Citation29,Citation43]. We then reviewed the reference lists and conducted citation searches to identify any additional articles that may have been missed, however no further articles were identified through this process.

Table 1. Summary of included papers.

Data analysis

Analysis utilised reflexive thematic analysis [Citation38,Citation39] and was jointly conducted by the three authors. He Awa Whiria prompted us to engage with material in ways that were appropriate for each stream. This is evident in how we considered: (1) whose perspectives constituted data for this metasynthesis, and (2) how our research team engaged with material from each stream. All 18 papers were analysed for the General stream by FB and CIR, reflecting that this analysis was done from a Pākehā perspective; the three Māori papers were also separately analysed in the Māori stream, from a Te Ao Māori perspective, by BJW. For the General stream, perspectives from the person who experienced stroke constituted data whilst for the Māori stream, we included material from whānau Māori (the person who had the stroke and those in their support network who participated in the research). This difference reflects that in Te Ao Māori, mātauranga (knowledge and wisdom) is collectively held and therefore should be explored and engaged with, from an inclusive and collective perspective. In engaging with papers, we discussed them collectively as a team, however, the first four stages of analysis of papers in the Māori stream were led by our Māori researcher while the analysis of papers in the General stream was led by our Pākehā researchers. By first four stages, we refer to the first four steps of reflexive thematic analysis – familiarisation, coding, generating initial themes, and developing and reviewing themes [Citation39]. Through this, we ensured that when themes, or aspects of themes, appeared unique to Māori, the analysis of these was led by our Māori researcher though as a team, we continued to explore areas of similarity and difference. By engaging uniquely with the Māori papers, we sought to ensure that these did not become invisible amidst the (majority) general papers. These similarities and differences were core topics of analytic discussions. This approach ensured each knowledge base was engaged with in its own right.

For the purposes of this metasynthesis, material in the Findings and Discussion constituted data, although the Introduction and Methods sections informed understanding of the context and underpinnings of the research, a core component of qualitative metasynthesis [Citation35]. We engaged in iterative and recursive six-step approach to reflexive thematic analysis detailed by Braun and Clark, and Terry and Hayfield [Citation38,Citation39]. The steps are marked with italics. After reading and creating a synopsis of each article to facilitate familiarisation with the literature, we engaged in a process of coding the data using semantic (descriptive) and latent (interpretive) codes. ‘Data’ constituted material which provided insight into understandings and experiences of psychosocial well-being. In determining what we attended to within the original papers, we oriented to data that related to aspects of the concept ‘psychosocial well-being’, with psychosocial referring to psychological, social, and/or emotional aspects of life after stroke, and well-being relating to their overall sense of wellness, and their inner self. Our coding was inductive not deductive, and so these acted as sensitising concepts to help us consider what was relevant ‘data’ for the metasynthesis. We collated the data excerpts and assigned codes in Microsoft Word then met together to discuss the initial codes. Using an online Miro board, we generated initial themes by grouping codes into candidate (potential) themes, assigning labels and generating thematic descriptors for the themes. To develop and review themes, we returned to the original articles, reviewing the coded material and contextual data surrounding it, and in some instances, refining coding with the candidate themes in mind. In doing so, our candidate themes were refined, for example, with ‘a sense of belonging and at homeness’ and ‘a sense of possibility’ being collapsed into one theme: ‘being at-home in the present while (re)visioning the future’. This process of moving back and forward through analysis and between different knowledge sources reflects the recursive nature of reflexive thematic analysis [Citation38] and the intent of He Awa Whiria [Citation36]. At the fifth stage of refining, defining and naming themes, we integrated the general and Māori data and analysis within our analytic writing as we wrote the final analysis. Our Findings reflect the integration of the Māori and non-Māori knowledges.

The quality of the included papers was not appraised as articles are not excluded for lower quality scores in a metasynthesis [Citation33] and because traditional appraisal tools are based on Western constructs of knowledge and quality and do not reflect the “heart and meaning” of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) [Citation40]. Throughout the process of review, we sought to ensure methodological and intellectual rigour by: staying grounded in the data and considering the data extracts in the context of the whole of the original work; maintaining records of analytic thinking which integrated memos, data, and recordings of discussion; integrating original data into the published report; utilising the different knowledges of the research team who have cultural, clinical, and methodological diversity which supports different ways of understanding primary data; and attending to how the data reflected particular research paradigms and privileged particular knowledges [Citation33].

Results

We constructed three themes which provide insight into how people experience psychosocial well-being after a stroke in Aotearoa. These are: (1) Connection within a constellation of relationships which reflects that relationships, connection and belonging are central to well-being; (2) Being grounded in one’s enduring and evolving identity demonstrates how having a sense of identity which grounds people and contributes to the sense of well-being; and (3) Being at-home in the present while (re)visioning the future highlights that well-being was enabled when people had a sense of acceptance of the present, a vision of a desired future, and a sense of movement toward this desired future. Throughout the Findings, we have included direct quotations from the original papers which constituted data for this metasynthesis. If required for context, we have added brief material to ensure the meaning is clear. This is provided in square brackets.

Connection within a constellation of relationships

Central to well-being was connection: being in relationships and having a sense of belonging. Relationships were a resource; through them and what they brought about, came a sense of well-being. Well-being happened in relationships with others, people who provided support, encouragement, and grounding. These relationships were commonly multiple, featuring family, friends, healthcare providers and others with stroke; something other authors have described as a “constellation of relationships” [Citation41]. These different parties provided motivation [Citation42], hope and positivity [Citation42,Citation43], inspiration and validation [Citation44], practical and emotional support [Citation45,Citation46] and were seen to be pivotal in helping people move forward and progress after their stroke [Citation28,Citation43]. Family and friends were perceived to be critical in recovery, supporting people to achieve more than they thought possible [Citation28]. Family were often a constant form of practical and emotional support [Citation28,Citation42,Citation47], described by one person as “the extra team you already had [even before the stroke]” [Citation28]. The social connections and influence of these “nurturing relationships” [Citation46] was not taken for granted. These were considered to have a preventative role, helping shield people from depression [Citation48]. Relational supports helped anchor people and helped hold space for well-being at a vulnerable time in the person’s life.

Friendships were vulnerable to the impacts of stroke, more so than family relationships. Interactional patterns and ways of engaging with others could change. This could see people take a more passive role. A loss of friendships was not uncommon [Citation28], particularly when people experienced aphasia [Citation49]. Shared activities were not always possible because of the impacts of stroke; friends did not always make (or know how to make) the modifications needed to enable the person with stroke to participate [Citation42], something particularly common in the presence of aphasia [Citation42,Citation49]. People described withdrawing from their friends because of shame or stigma [Citation28,Citation49], a loss of confidence [Citation28] or because of the challenge of adjusting to the stroke [Citation48]. Friends themselves may withdraw [Citation49]. With the loss of friendships could come the loss of connection to people, activities and roles that supported well-being. Family support often became more significant as the physical, psychological and relational impacts of stroke become more evident [Citation28,Citation47,Citation49,Citation50]. For those who perceived a ‘shrinking world’ [Citation28,Citation49], family then become their main source of support with one saying “you just shrank down to your family” [Citation49], who took on a role as a ‘connector’, helping people connect to other people and to rehabilitation, and to other sources of well-being. For Māori, whānau is an integral cultural construct which both includes, yet extends beyond commonly understood parameters of ‘family’, to those within a person’s wider network who they identify as important to them. Whānau Māori were actively involved in the care and treatment of the person with stroke [Citation28,Citation29], acting as an anchor and source of well-being. Many assumed responsibility for their whānau member, which they described as “deep” and “almost spiritual” in nature [Citation47]. This sense of responsibility was often taken up by others within the wider community [Citation29]. Whānau Māori experiences reflected that people worked intentionally to support ongoing engagement in roles and to uphold their mana (standing) [Citation29,Citation47], sometimes with implications for their own personal relationships and well-being: “[I] Just let her enjoy as much as she can. I don’t care what I’ve gotta go through” [Citation47]. Through active support of family, people could remain connected with others and with activities that supported well-being and recovery.

Being with others who had a stroke, connecting with others “in the same boat” [Citation42] could be critical in providing a space for well-being to grow. These shared experiences helped co-create a space where people had a sense of belonging and of being understood, a sense that “we are all in the same boat” [Citation51]. These new connections could substitute for previous relationships and activities and positively influence well-being [Citation49]. For some Māori with aphasia, being with others with aphasia provided whanaungatanga (connections and a sense of belonging) [Citation29]. In the early days after stroke, these connections set people at ease and provided a sense of belonging at a time of vulnerability [Citation51]. Seeing or reading about other people’s progress and journeys provided hope [Citation42,Citation51,Citation52], motivation [Citation42] and helped people see that there were a range of future possibilities post-stroke [Citation42,Citation52]. Being exposed “to others living active lives … helped them both look for new possibilities and to ‘find’ a space where they belonged” [Citation53]. Similarly, Kitt et al. [Citation51] found that “having the opportunity to relate to others may have offered the support needed to gain courage and trust in one’s new self and the motivation to engage in [therapy]” (p. 60). For those with aphasia, peer-facilitated groups provided a space for friendships and helped give a sense of community, as outside of these, many felt they “were the only one who couldn’t speak” [Citation49]; a real feeling of aloneness. Being with others provided connections and a sense of being “part of the community again” [Citation49].

Whilst the focus has been on what the constellation of relationships gives to the person with stroke, there is a risk that this positions the person as a passive recipient of support. It was clear that part of belonging was being able to offer that to others. The person with stroke was themselves a resource of support for others and contributed to the well-being of others, which in turn fuelled their own sense of well-being. This was particularly evident within relationships with others who had a stroke. Becker and colleagues [Citation46] identified:

For some, [purpose in life] was achieved by …offering their advice to other stroke survivors … most participants regularly attended Stroke Club, where they would discuss their experiences with stroke or rehabilitation: as Joyce expressed “That is what made me tell it because I thought it may help. (p. 5).

Being grounded in one’s enduring and evolving identities

Identity is multi-faceted, comprised of multiple strands, which together make up the person, many of which were disrupted by the stroke. For some, the stroke was seen to inherently impact on their entire being: “‘it’s not just the brain eh … It’s the whole āhua’. Āhua is one’s presence, being, or identity”[Citation47]. Many of the strands which made people who they are were disrupted by stroke, resulting in a “loss of familiarity with the self” [Citation53]. An inability to maintain previously valued roles and activities could be felt as a “loss of self” [Citation51], impacting upon well-being [Citation28]. This contributed to a sense of disconnection with their “former self” in the early days post-stroke: “… their former lives barely seeming real. Being unable to participate in the same way as prior to their stroke led to a loss of hope of recovering their former self” [Citation51]. A sense of discomfort, and even self-stigma with regard to one’s post-stroke self could leave people feeling disconnected from themselves, and could see them actively disconnect from others, from roles and activities that contributed to their sense of identity pre-stroke [Citation28,Citation43,Citation49,Citation51]. When other people failed to recognise their personhood, it reinforced the disconnection from their sense of self. Health services could dehumanise people, failing to recognise their personhood in mechanistic interactions [Citation51] and requiring people to fit in with inflexible services [Citation54]. One whānau member described services as having “no Māori-ness about them”, and that “by using a resource that Makere was not interested in, the [speech-language pathologist] was not acknowledging Makere’s identity through her ties to her family and land. This was detrimental to the therapeutic relationship and, therefore, to the success of therapy” [Citation29]. In contrast, “when the [therapist] tailored the therapy to their interests, it showed them that she recognized their individual personalities and identities” [Citation29]. Having one’s personal interests, values, cultural identity and language recognised and integrated into care created an engaging therapeutic space that supported and uplifted one’s identity and well-being [Citation29,Citation51,Citation55].

An important element that grounded many Māori living with stroke and their whānau post-stroke and supported well-being was their connection to their cultural identity. This gave them “the strength and resilience to tackle the challenges they faced” [Citation28]. Māori with aphasia experienced particular challenges though, as language is central to identity. Indeed, for one woman, her loss of language was felt as “tragic”. Her daughter described this: “Talking, articulating with voice is foundational to our peoplehood, to my mother’s Aitanga-a-Hauiti identity [her identity in her iwi or tribe]. If you have no one to speak and represent one’s peoplehood, then you die” [Citation47]. Whānau were critical in upholding the person’s identity as Māori and in supporting well-being in the context of services which commonly failed to recognise people’s culture and worldview [Citation29]. One son described himself as having to “jump through all the hoops” [Citation29] to get support which was challenging in a monocultural system that had “no Māori-ness about it” [Citation29]. Despite the central role of whānau in supporting well-being, it appeared that they are not consistently involved in rehabilitation [Citation28,Citation29]. This reflects that services were Eurocentric, focused on the individual rather than the collective whānau as is central in Te Ao Māori. These failed to acknowledge let al.one support cultural identity. This further reduced well-being as they further distanced people from their cultural identity, the very thing that grounded and supported them.

When people were able to (re)connect with “what makes me ‘me’” as one person described [Citation55], it fostered their well-being and helped them cope with the challenges that can result during life after stroke [Citation53]. This sense of identity appeared intrinsically linked to well-being:

Those with a strong sense of self appeared able to sit with uncertainty. For example, Tony expressed a sense of peace with himself and his circumstances: ‘I feel really at peace … I just feel very confident with who I am’ [Citation53].

The stroke also provided an opportunity for many to reshape their sense of identity, through necessity and through choice. While people’s identities were commonly grounded in their pre-stroke identity, people rarely aspired to simply return to this. Many were unable to return to things that supported or reflected their identity. Instead, some viewed the stroke as an opportunity to be “a new person” [Citation53] as the stroke prompted them to revisit what was important in life. Moreover, many people worked through a process of “discovering their new self” following stroke [Citation42]. This was commonly an ongoing process of adapting and recalibrating one’s self-understanding, reflecting on “what was important to them in their life, who they wanted to be and what they wanted to achieve in life” [Citation44]. When people were aware that their identity was evolving but there was an underlying sense of self, and when this evolving identity was seen as acceptable and in many cases welcomed, this contributed to a sense of well-being.

Being at-home in the present while (re)visioning the future

Following stroke, people commonly experienced disruption. Their present reality was somewhat unexpected and ever-changing; their assumptive future uncertain, disrupted by the impacts of the stroke. In a study of hope in people with aphasia, Bright and colleagues [Citation53] suggested “people were living in the present while both looking forward to the future and reflecting on their past” (p.3). Uncertainty, change and unknown possibility were features of the time after stroke [Citation43,Citation44,Citation50,Citation53,Citation55]. In this space, some people were able to sit with uncertainty, ‘be’ in the present, and perceive the potential for forward movement toward a possible future [Citation42,Citation53,Citation55].

Finding balance and stability in the present

Well-being was associated with the ability to be grounded in the present, finding stability despite the uncertainty of life post-stroke [Citation53]. This was commonly a space of hope[Citation43]. Not hopes of specific recovery or defined hopes of what life would look like, but a space in which people had a sense of hope that the future will be good. It was also characterised by an openness to learning about one’s limitations, and adjusting and adapting to one’s new reality [Citation42,Citation44,Citation48,Citation51,Citation52]. This involved making sense of what happened, a degree of accepting the changes brought about by stroke, and reflecting on what is important [Citation44]. In learning to live with change, people drew on aspects of their ‘old normality’, returning to valued activities in order to (re)create patterns of living [Citation46] whilst also engaging in new activities and relationships to create a new ‘normal’ [Citation46,Citation49,Citation51].

Finding grounding in the present was not easy, however. Many people struggled with the process. A multiplicity of emotions were evident in people’s narratives of the time post stroke: despair [Citation51], indifference [Citation46], resignation [Citation47], disempowerment [Citation54], frustration [Citation42] and mourning [Citation51]. The sense of loss was palpable in comments such as “All those good things in my life are over and that is hard to come to grips with” [Citation51]. Negative reactions from the community [Citation42], or a sense of shame and stigma contributed to challenges in adjusting [Citation47,Citation48]. With time, most were able to reach a place where they could sit with uncertainty and accept their current situation [Citation42,Citation48,Citation50,Citation56], aided by hearing the stories of others with stroke [Citation52] which helped adjustment [Citation52] and created a sense of gratefulness, positivity and possibility [Citation42,Citation49]. Making sense of the stroke and why it happened were repeatedly highlighted as important in adjusting to one’s new reality [Citation44,Citation48,Citation50,Citation56]. Being given clear, appropriate information, and having the time and space for the person and their whānau to discuss what was happening appeared to assist the process of feeling more settled in the present [Citation28].

Finding this point of ‘comfort and stability’ in the present did not mean letting go of the past. Even as people drew upon what was important to them during life pre-stroke, the grief, challenges and uncertainty brought about by stroke still remained [Citation44]. Indeed, this was a place of many seemingly contradictory emotions and experiences – gratefulness amidst grief [Citation42,Citation47,Citation49], hope amidst uncertainty [Citation43,Citation53], a familiar self within an unfamiliar body, or a new and strange self within a known body [Citation56]. Māori who had had a stroke identified that people could hold both grief for what was lost and recognition and appreciation of the current situation without this being inherently problematic [Citation47]. Holding hope involved reflecting on past progress and priorities and integrating these with one’s views and desires of the possible future. Bright and colleagues [Citation53] found that people may continue to hold hope for a return to their ‘old normal’, while simultaneously holding hopes for new possibilities and a different, desirable future, holding both together without issue. They suggested that being able to hold onto aspects of the past, present and future in this way may contributes to a sense of continuity, and helps people to experience a sense of ‘dwelling’ in the present. Accordingly, we suggest well-being is associated with an ability to sit with these changes and contradictions, finding balance and stability amidst the uncertainty and challenges.

Holding a vision of the future

A feature of well-being was the process of future-making. Creating “an image of the future” [Citation43] was often required because the person’s assumptive future, the future they thought would unfold, was disrupted by the stroke. Instead, they needed to create a “new life” and “new patterns of living” whilst managing their “new selves” [Citation42]. Active future-making required an ability to imagine and dream [Citation46], to hold hope [Citation53] and to re-envisage one’s priorities and sense of self [Citation44]. (Re)creating a vision of a possible future did not happen immediately after stroke. In fact, it appeared ever-changing:

At times, hopes and expectations for recovery dominated participants’ views of the future, while at other times their uncertainty would dominate. When hopes and expectations dominated, they expressed anticipation and positivity about the future. When uncertainty dominated, the future became restricted and the focus returned to the present, focusing on ‘just getting through’ [Citation43].

For some, moving forward required being able to clearly envisage their desired future and the pathway forward [Citation55]. To assist this, some people wanted clarity on prognosis and what might be possible in the future [Citation29,Citation55]. Some worked to re-establish normality by going back to known life activities and doing them again [Citation46], while others set ambitious personal goals to aim for [Citation52,Citation55] or articulated active hopes for the future, sometimes taking steps to realise these [Citation43]). “Seemingly impossible goals” could bring comfort, although people considered this was under threat from staff who might classify them as “unrealistic” [Citation55]. This highlights how well-being is not individually achieved, but is collectively developed, or diminished. Envisaging the future and pathways forward was commonly aided through goal setting as part of rehabilitation although achievement (or even the possibility of achievement) of said goals was not necessarily important – instead the important thing was that these offered a sense of direction and motivation [Citation55]. For others, however, the path forward did not need to be defined or moving toward a discrete objective or destination. Rather, having a broad sense of looking forward to improvement, a sense of forward movement, perceiving that progress is being made, and having a sense that the future may be positive were key factors in maintaining momentum [Citation45,Citation48,Citation53,Citation55].

Hope and purpose appeared important in enabling people to look to the future [Citation46,Citation53]. People described holding a broad sense of hope following stroke which could provide grounding in the present, while also holding a hope for the unseen future that was revised and recalibrated in response to their changing circumstances. There was a recursive relationship between hope, progress, and future possibilities. Hope increased when people perceived progress [Citation45,Citation48,Citation52,Citation53,Citation55] and when they had a view of a possible future [Citation43]. Sitting alongside hope was purpose and meaning. People described trying to “find a purpose beyond the stroke” [Citation42], sometimes through engaging in activities that helped create purpose in their lives and by contributing to others [Citation46]. This helped people feel there was meaning in their lives, “which led to them being more positive and life-affirming” [Citation46]; it also reinforced their own personal value and contributions, with people “feeling valued and appreciated” [Citation46]. Together, hope, purpose and possibility provided a reason for living [Citation43].

Discussion

This metasynthesis, focusing on the psychosocial well-being of people living with stroke in Aotearoa, demonstrates that well-being is multi-faceted. Within our three themes, we show how well-being comes through an interweaving of connectedness with others, of personal, cultural and collective identities, of feeling at-home in the present, and of having a vision and sense of movement toward a desired future. At the core of this metasynthesis is an understanding that well-being is deeply social, personal, and temporal in nature. This offers a unique perspective on well-being, shifting beyond understandings of well-being as something situated within the individual, as often foregrounded in the literature [Citation22], to understanding it as collectively achieved, through connections with self, others, community and culture. Well-being is inherently collective, grounded, supported and maintained through interactions and relationships with others, fostered through a sense of connectedness and belonging. At the same time, well-being is also inherently personal, experienced uniquely by each person, and deeply grounded in their enduring and evolving identities. This identity, ever-in-development, incorporates people’s enduring pre-stroke sense of self, and their evolving identity that grew and continued to develop after the stroke as people made sense of what happened and what matters to them. Well-being occurs within “overlapping temporalities” [Citation57] of past, present and future, occurring when people could draw on their known and familiar past, whilst having a sense of comfort and stability in their present and looking toward a possible, desirable future. These strands are evident within all the themes presented in the Results, suggesting that well-being comes through the interweaving of personal, social and temporal worlds. While this analysis originates from the perspectives of people with stroke in Aotearoa, these areas also hold relevance, and speak to discussions happening internationally, as can be seen from the fact the remainder of the Discussion draws on literature from both Aotearoa and internationally. Within this discussion, we will focus on several aspects of the Findings which are particularly relevant to the aims of this metasynthesis: to develop understandings of psychosocial well-being in Aotearoa from the experiences of those impacted by stroke, recognising the need for locally-based understandings. Specifically, we focus on the social and temporal elements of psychosocial well-being that have been elucidated in this review.

Our review makes clear the pivotal role of social relationships in psychosocial well-being. These relationships were important in and of themselves because of the sense of belonging and connectedness that they brought about. Beyond that though, these underpinned other aspects of well-being. One’s social world was integral in one’s identity and self-concept, as expressed in our theme ‘being grounded in one’s enduring and evolving identities’. Rather than seeing one’s self-concept and social relationships as separate components of well-being [Citation14], our review demonstrates how these are entwined; that one’s self-concept is inherently social, supported and formed through one’s collective and cultural identities. For many, these externally-mediated identities carried people through times when their self-concept was threatened or fractured by the stroke. Viewing psychosocial well-being as being embedded within one’s cultural and collective identities and entwined within the interactions with one’s social world, rather than something individually achieved, affirms the crucial role of social relationships in well-being after stroke [Citation14,Citation18,Citation20,Citation58,Citation59]. In particular, our review demonstrates the critical role of family, whānau and others who had experienced stroke. Within Te Ao Māori (a Māori worldview), whānau are recognised as a pillar of well-being [Citation60] and the well-being of an individual is viewed as ‘indivisible’ from that of their whānau [Citation61]. The centrality of others in well-being perhaps contrasts with more individualistic Western cultures, and in biomedical health systems which focus on the individual with stroke, not recognising the critical role family and whānau have in supporting well-being and recovery beyond the designated role of ‘carer’, or not attending to specific well-being needs of family members [Citation62,Citation63]. Our review shows how social relationships with others with stroke can be particularly important in well-being. These created a sense of belonging which in turn, helped develop a person’s identity as a person living with stroke, and their post-stroke identity, and supported them in looking toward the future [Citation29,Citation49,Citation51]. This aligns with other literature which demonstrates the critical role of peer relationships in creating spaces of support and belonging [Citation64] and facilitating well-being [Citation65,Citation66]. Our review suggests that social relationships – with family, friends and others with stroke – are generally not facilitated by stroke services across the continuum of care. Instead, it was family members, or the person’s own efforts that built and sustained relationships. In fact, services could inhibit or place significant pressure on relationships, something particularly evident in the experiences of Māori whānau who reported not being recognised or supported, and at times, actively excluded in service design and delivery despite whānau being a source of hauora (health and well-being) [Citation60]. At an institutional level, this represents a form of racism which is a negative determinant of health and well-being [Citation67]. Given that well-being is socially achieved, and that whānau, friends, and people’s wider communities are key in supporting well-being, this needs attention and support within services. By considering the collective(s) who are key in supporting people’s on-going well-being, services can enact a proactive approach to care, sustaining relationships and preventing losses of social networks after stroke [Citation68].

This review prompts us to consider the temporal element of well-being: the interwoven past, present and future. Occupational science literature argues we are always in an ongoing process of being and becoming [Citation69]; this is particularly evident in our theme which considers how identities that are enduring and evolving. Considering well-being as situated within a person’s “overlapping temporalities” [Citation57] of past, present and future reflects Leder’s [Citation70] argument that, after illness, richness in life comes from weaving together temporalities – “remembering the past, anticipating the future and presencing, that is, living fully in the here and now” (p. 99). Others outside stroke rehabilitation have proposed that well-being comes when one has a sense of dwelling-mobility: a sense of dwelling (or ‘at homeness’) in the present and a sense of movement toward the future [Citation71], evident in our theme ‘being at-home in the present whilst (re)visioning the future’. For Māori, looking to one’s past involves looking beyond one’s own history, to draw on the strengths from those who have gone before them as people’s identity sits within a wider sense of belonging within their hapū (sub-tribe) and iwi (tribe) [Citation72], and reflects Māori perspectives of time in which the past, present and future are entwined and the past is central to, and shapes one’s present and future [Citation73]. This further illustrates how collective and cultural identities are important in well-being and how personal, social and temporal domains are entwined. Acknowledging and building on the strengths of a person’s past and present to support people as they create visions of, and move toward their desired future, may be one way to take a person-centred and strengths-based approach to supporting well-being and recovery. Viewing the future as one that is ever-being-made highlights the important role that services can play in supporting future-making, creating opportunities for “new futures … to grow into being” [Citation57].

Whilst our discussion has focused on the social and temporal aspects of well-being, there are other findings which need discussion, in light of how they add nuance to existing conceptualisations of psychosocial well-being. Like Kirkevold [Citation14], our findings reflect the importance of engaging in meaningful activities. This appeared to both support well-being (e.g., when completing activities and roles that supported one’s identity [Citation47]) and reflect an outcome of well-being (e.g., when people experienced a sense of well-being, they were more likely to engage in activities [Citation49]). Of note, in many instances it was not so much that doing activities was important, but what the doing brought about – the sense of making a contribution, of reinforcing a sense of self, of whanaungatanga in being connected with others (whanaungatanga stems from Māori worldviews, referring to developing meaningful connections and relational linkages). This further reflects how the facets of well-being are interconnected. Perhaps the area of greatest difference from the existing well-being after stroke literature is the place of positive mood in well-being. Whilst Kirkevold and colleagues found that positive mood and “the absence of sadness or a feeling of emptiness” [Citation14] was an aspect of well-being and others talked of the value of positive outlooks [Citation20,Citation21], this metasynthesis suggests it is not simply having a positive mood or the absence of psychological sequalae. Instead, we identified that both positive and negative emotions could exist. People could report experiencing well-being whilst also describing loss, grief and uncertainty, to name some emotions. When people had a sense of identity and a degree of being at peace with the past and present, it appeared to enable them to hold multiple emotions without these conflicting or being distressing. Our review suggests that what matters is a sense of equilibrium which allows different emotions to co-exist. This reflects wider understandings of well-being, which propose that well-being is inherently dynamic and that continued movement and change is a feature of well-being [Citation74]. In fact, some suggest that the ability to manage ups and downs is considered to reflect the “true level of well-being” [Citation74].

A strength of this metasynthesis is our use of He Awa Whiria [Citation36] which highlighted particular features for Māori which we might have missed had we not uniquely engaged with the Māori literature – the importance of cultural and intergenerational identity, and the critical role of whānau and of community in well-being, as two examples. This also prompted us to look for evidence of these themes in other papers and thus facilitated a deeper analysis. This is a strength of our research approach which was designed to enable a deeper understanding of diversity in experience, supported through the research team composition and use of He Awa Whiria. At the same time, we also are aware of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) that exists outside Western academic publications [Citation40], and as such, were not captured within our search strategy. As a result, we are conducting a wider review of well-being for Māori, engaging with a range of materials and knowledges to develop our understandings. Our review has focused on the perspectives and experiences of people with stroke, although for Māori, we included the perspectives of whānau. Given our review has demonstrated the collective and relational nature of well-being, there would be benefit from further understanding family and whānau perspectives. Indeed, these may have offered deeper, or different insights into well-being. In this review, however, we wished to give primacy to the voices of those who had had a stroke. Our use of He Awa Whiria and our specific focus on experiences of people in Aotearoa has ensured that we generated findings that reflect “local understandings” [Citation75] of what constitutes and creates well-being. As such, this offers an example of research practice that engages with, represents, and contributes to Indigenous communities. However, the findings of this metasynthesis are limited by the published material from Aotearoa. Few studies explicitly explored psychosocial well-being. Our search was conducted in May 2022; several papers have been published whilst analysis was occurring [e.g., Citation76,Citation77] which may be considered in future work in this area as they offer insight into Māori experiences after stroke. Moreover, studies generally reflected an Interpretive approach focused on understanding individual experiences of life after stroke. There was little consideration of the wider social, structural and material factors which impact on well-being which highlights an area for future research. Willen and colleagues [Citation22] recently asked “who has the opportunity to live a flourishing life, who does not, and why?” (p. 1) and suggested this also applies to well-being. Critical public health research is demonstrating that an individual’s well-being cannot be seen apart from their personal social world and the broader material world they live within. In the context of New Zealand, a country founded through colonisation, in which Indigenous people experience significant marginalisation and disparities in stroke incidence, service provision and outcome [Citation24,Citation25] and institutional and interpersonal racism in health services [Citation78], it is critical to attend to how well-being is impacted by the wider societal context, and how this might be exacerbated when someone has a stroke. It also suggests that supporting well-being after stroke needs to take wider contexts and experiences into account. This public health perspective will be woven into our future work.

Through this metasynthesis, we identify a number of implications for practice. While these are grounded in research in Aotearoa, these recommendations are relevant to stroke care beyond Aotearoa, and indeed, are aligned with stroke research conducted internationally. First, we demonstrate the significant psychosocial impacts of stroke that clinicians and services need to take into account, that people with stroke report are not consistently being addressed. The time that most services are provided is a time of significant grief and a myriad of emotions as people make sense of the stroke and come to realise its impacts [Citation44,Citation79]. While for some this might require specialist psychological support, for many, this requires attentive listening, information, normalising, and support as they navigate through this process [Citation80], developing a sense of equilibrium [Citation74]. Second, this review might prompt clinicians and services to reflect on what is prioritised and supported in care. It clearly demonstrates the importance of social relationships, identity, knowing and building on people’s past, and supporting people to ‘be’ in the present and to look toward a desired future. The unique needs of family as a source of well-being, and as people whose own well-being is often threatened by stroke, are not well-addressed [Citation15,Citation81]. Yet services commonly focus on the individual with stroke, on people’s physical needs and their impairments and basic activities, on short-term outcomes and on helping people move between stroke services [Citation13]. This reflects broader healthcare pressures and a Western, individualistic orientation to health and rehabilitation, but can mean services can themselves be a barrier to well-being [Citation28,Citation29]. Processes such as goal-setting have great potential to support future-making and are nearly ubiquitous within strokes services. However, our review highlights existing processes can see people’s visions of possible futures shut down, or not disclosed for fear of staff reactions. Reflecting on what and who is supported in services, and considering the unintended consequences of dominant practice models may help identify areas for practice development. One aspect of this might be considering how services might create a therapeutic milieu, a physical, social and relational environment that fosters well-being whilst in services and beyond. However, having identified the implications for practice and services, we do not want to give the impression that well-being is the sole responsibility of services. Indeed, this review shows the critical role of one’s social world in well-being. Our own Māori advisors have cautioned us about suggesting the answers to well-being all sit within the healthcare system. Instead, they suggest that services need to consider how they can support, and create space for whānau and communities to support well-being.

Conclusion

This metasynthesis advances understandings of how psychosocial well-being is experienced, and what supports well-being in Aotearoa. Through grounding our analysis in the experiences of those with living experience of stroke [Citation16], we have come to see that well-being is deeply personal yet inherently collective. It is grounded in social connectedness, personal, collective and cultural identities, and sits within and across experiences and visions of the past, present and future. These findings will be tested and developed through future research to build more comprehensive understandings of psychosocial well-being. Integrating knowledge of well-being into services and into support for those impacted by stroke can help foster better experiences and outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank our physiotherapy students, Holly Hing, Kira Milne, Nikita Ngarongo-Porima, and Chelsie Park, for their assistance in literature searching and screening. The authors thank Dr Gareth Terry for his thoughtful critique of an early draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Guo J, Wang J, Sun W, et al. The advances of post-stroke depression: 2021 update. J Neurol. 2022;269(3):1236–1249.

- Campbell Burton CA, Murray J, Holmes J, et al. Frequency of anxiety after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. 2013;8(7):545–559.

- Knapp P, Dunn-Roberts A, Sahib N, et al. Frequency of anxiety after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Stroke. 2020;15(3):244–255.

- Kauhanen ML, Korpelainen JT, Hiltunen P, et al. Aphasia, depression, and non-verbal cognitive impairment in ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2000;10(6):455–461.

- Morris R, Eccles A, Ryan B, et al. Prevalence of anxiety in people with aphasia after stroke. Aphasiology. 2017;31(12):1410–1415.

- Northcott S, Moss B, Harrison K, et al. A systematic review of the impact of stroke on social support and social networks: associated factors and patterns of change. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(8):811–831.

- Aström M, Adolfsson R, Asplund K. Major depression in stroke patients. A 3-year longitudinal study. Stroke. 1993;24(7):976–982.

- Kringle EA, Terhorst L, Butters MA, et al. Clinical predictors of engagement in inpatient rehabilitation among stroke survivors with cognitive deficits: an exploratory study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24(6):572–583.

- Della Vecchia C, Viprey M, Haesebaert J, et al. Contextual determinants of participation after stroke: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(13):1786–1798.

- Boden-Albala B, Litwak E, Elkind MSV, et al. Social isolation and outcomes post stroke. Neurology. 2005;64(11):1888–1892.

- Ellis-Hill C, Horn S. Change in identity and self-concept: a new theoretical approach to recovery following a stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2000;14(3):279–287.

- Glass TA, Maddox GL. The quality and quantity of social support: stroke recovery as psychosocial transition. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34(11):1249–1261.

- Evans M, Hocking C, Kersten P. Mapping the rehabilitation interventions of a community stroke team to the extended international classification of functioning, disability and health core set for stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(25):2544–2550.

- Kirkevold M, Bronken BA, Martinsen R, et al. Promoting psychosocial well-being following a stroke: developing a theoretically and empirically sound complex intervention. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(4):386–397.

- Stroke Association. Feeling overwhelmed. 2015.

- Rixon C. Connection: stories not statistics. Brain Impairment. 2022;23(1):4–8.

- Hole E, Stubbs B, Roskell C, et al. The patient’s experience of the psychosocial process that influences identity following stroke rehabilitation: a metaethnography. The Scientific World Journal. 2014;2014:1–13.

- Manning M, MacFarlane A, Hickey A, et al. Perspectives of people with aphasia post-stroke towards personal recovery and living successfully: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0214200.

- Griffin-Musick JR, Off CA, Milman L, et al. The impact of a university-based intensive comprehensive aphasia program (ICAP) on psychosocial well-being in stroke survivors with aphasia. Aphasiology. 2021;35(10):1363–1389.

- Grohn B, Worrall L, Simmons-Mackie N, et al. Living successfully with aphasia during the first year post-stroke: a longitudinal qualitative study. Aphasiology. 2014;28(12):1405–1425.

- Brown K, Worrall LE, Davidson B, et al. Living successfully with aphasia: a qualitative meta-analysis of the perspectives of individuals with aphasia, family members, and speech-language pathologists. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2012;14(2):141–155.

- Willen SS. Flourishing and health in critical perspective: an invitation to interdisciplinary dialogue. SSM Mental Health. 2022;2:100045.

- Ranta A. Projected stroke volumes to provide a 10-year direction for New Zealand stroke services. N Z Med J. 2018;131(1477):15–28.

- Feigin V, Carter K, Hackett M, et al. Ethnic disparities in incidence of stroke subtypes: auckland regional community stroke study, 2002-2003. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(2):130–139.

- Thompson SG, Barber PA, Gommans JH, et al. The impact of ethnicity on stroke care access and patient outcomes: a New Zealand nationwide observational study. Lancet Reg Health Western Pacific. 2022;20:100358.

- Feigin VL, McNaughton H, Dyall L. Burden of stroke in maori and pacific peoples of New Zealand. Int J Stroke. 2007;2(3):208–210.

- Bonita R, Broad JB, Beaglehole R. Ethnic differences in stroke incidence and case fatality in Auckland, New Zealand. Stroke. 1997;28(4):758–761.

- Dyall L, Feigin V, Brown P. Stroke: a picture of health disparities in New Zealand. Social Pol J N Zeal. 2008;(33):178–191.

- McLellan KM, McCann CM, Worrall LE, et al. Māori experiences of aphasia therapy: "but I’m from hauiti and we’ve got shags. Inter J Speech Lang Pathol. 2014;16(5):529–540.

- Rolleston A, McDonald M, Miskelly P. Our story: a māori perspective of flourishing Whānau. Kōtuitui N Z J Soc Sci Onl. 2021;17:277–297.

- Thorne S. Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice. 2nd ed. New York (NY): Routledge; 2016.

- Levack WMM. The role of qualitative metasynthesis in evidence-based physical therapy. Phys Ther Rev. 2012;17(6):390–397.

- Thorne SE. Metasynthetic madness: what kind of monster have we created? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(1):3–12.

- Thorne S. Qualitative meta-synthesis. Nurse Author Editor. 2022;32(1):15–18.

- Thorne SE. Qualitative metasynthesis: a technical exercise or a source of new knowledge? Psychooncology. 2015;24(11):1347–1348.

- MacFarlane AH, MacFarlane S. Toitū te mātauranga: valuing culturally inclusive research in contemporary times. Psychol Aotearoa. 2018;10(2):71–76.

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–352.

- Terry, G, et al. Thematic analysis. In: Willig C and Stainton Rogers W, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology. London: SAGE; 2017. p. 17–37.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. London: SAGE Publications; 2021.

- Rolleston AK, Cassim S, Kidd J, et al. Seeing the unseen: evidence of kaupapa māori health interventions. AlterNative Inter J Indig Peoples. 2020;16(2):129–136.

- Carolan M, Andrews GJ, Hodnett E. Writing place: a comparison of nursing research and health geography. Nurs Inq. 2006;13(3):203–219.

- Ahuja SS, et al. The journey to recovery: experiences and perceptions of individuals following stroke. N Z J Physiother. 2013;41:36–43.

- Bright FAS, Kayes NM, McCann CM, et al. Hope in people with aphasia. Aphasiology. 2013;27(1):41–58.

- Theadom A, Rutherford S, Kent B, et al. The process of adjustment over time following stroke: a longitudinal qualitative study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2019;29(9):1464–1474.

- Stretton C, Mudge S, Kayes NM, et al. Activity coaching to improve walking is liked by rehabilitation patients but physiotherapists have concerns: a qualitative study. J Physiother. 2013;59(3):199–206.

- Becker I, Maleka MD, Stewart A, et al. Community reintegration post-stroke in New Zealand: understanding the experiences of stroke survivors in the lower South island. Disab Rehabil. 2022;44(12):2815–2822.

- McLellan KM, McCann CM, Worrall LE, et al. For māori, language is precious. And without it we are a bit lost": māori experiences of aphasia. Aphasiology. 2014;28(4):453–470.

- Singh P, Jayakaran P, Mani R, et al. The experiences of indian people living in New Zealand with stroke. Disab Rehabil. 2022;44(14):3641–3649.

- Rotherham A, Howe T, Tillard G. “We just thought that this was christmas”: perceived benefits of participating in aphasia, stroke, and other groups. Aphasiology. 2015;29(8):965–982.

- Rutherford SJ, Hocking C, Theadom A, et al. Exploring challenges at 6 months after stroke. What is important to patients for self-management? Inter J Ther Rehabil. 2018;25(11):565–575.

- Kitt C, Wang V, Harvey-Fitzgerald L, et al. Gaining perspectives of people with stroke, to inform development of a group exercise programme: a qualitative study. NZJP. 2016;44(1):58–64.

- Hale L, Jones F, Mulligan H, et al. Developing the bridges self-management programme for New Zealand stroke survivors: a case study. Inter J Ther Rehabil. 2014;21(8):381–388.

- Bright FAS, McCann CM, Kayes NM. Recalibrating hope: a longitudinal study of the experiences of people with aphasia after stroke. Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34(2):428–435.

- Turner J. Environmental factors of hospitalisation which contribute to post-stroke depression during rehabilitation for over 65 year olds. J Austral Rehabil Nurses Assoc. 2012;15(1):11–15.

- Brown M, Levack W, McPherson KM, et al. Survival, momentum, and things that make me “me”: patients’ perceptions of goal setting after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(12):1020–1026.

- Timothy EK, Graham FP, Levack WMM. Transitions in the embodied experience after stroke: grounded theory study. Phys Ther. 2016;96(10):1565–1575.

- Krogager Mathiasen M, Bastrup Jørgensen L, From M, et al. The temporality of uncertainty in decision-making and treatment of severe brain injury. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0238506.

- Nilsson I, Axelsson K, Gustafson Y, et al. Well-being, sense of coherence, and burnout in stroke victims and spouses during the first few months after stroke. Scand J Caring Sci. 2001;15(3):203–214.

- Brown K, Worrall L, Davidson B, et al. Snapshots of success: an insider perspective on living successfully with aphasia. Aphasiology. 2010;24(10):1267–1295.

- Durie M. Whaiora: māori health development. Auckland Oxford University Press; 1994.

- Love C. Extensions on Te wheke. New Zealand: The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand; 2004.

- Visvanathan A, Mead GE, Dennis M, et al. The considerations, experiences and support needs of family members making treatment decisions for patients admitted with major stroke: a qualitative study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):98.

- Kitzmüller G, Asplund K, Häggström T. The long-term experience of family life after stroke. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(1):E1–E13.

- Suddick KM, Cross V, Vuoskoski P, et al. Holding space and transitional space: stroke survivors’ lived experience of being on an acute stroke unit. A hermeneutic phenomenological study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2021;35(1):104–114.

- Cutler M, Nelson MLA, Nikoloski M, et al. Mindful connections: the role of a peer support group on the psychosocial adjustment for adults recovering from brain injury. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2016;15(3-4):260–284.

- Lamont RA, et al. Shared social identity and perceived social support among stroke groups during the COVID-19 pandemic: relationship with psychosocial health. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 15(1):172–192.

- Palmer SC, Gray H, Huria T, et al. Reported māori consumer experiences of health systems and programs in qualitative research: a systematic review with meta-synthesis. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):163.

- Azios JH, Strong KA, Archer B, et al. Friendship matters: a research agenda for aphasia. Aphasiology. 2022;36(3):317–336.

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. 3rd ed. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; 2015.

- Leder D. Healing time: the experience of body and temporality when coping with illness and incapacity. Med Health Care Philos. 2021;24(1):99–111.

- Todres L, Galvin K. Dwelling-mobility": an existential theory of well-being. Inter J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2010;5(3):5444.

- Moeke-Pickering T. Maori identity within whanau: a review of literature. Hamilton: University of Waikato; 1996.

- Rameka L. Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: ‘I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past. Contemp Issues Early Childhood. 2016;17(4):387–398.

- Dodge R, Daly A, Huyton J, et al. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Intnl J Wellbeing. 2012;2(3):222–235.

- Cele L, Willen SS, Dhanuka M, et al. Ukuphumelela: flourishing and the pursuit of a good life, and good health, in soweto, South Africa. SSM Mental Health. 2021;1:100022.

- Wilson B-J, Bright FAS, Cummins C, et al. ‘The wairua first brings you together’: māori experiences of meaningful connection in neurorehabilitation. Brain Impair. 2022;23(1):9–23.

- Brewer KM, Taki TW, Heays G, et al. Tino rangatiratanga – a rural māori community’s response to stroke: ‘I’m an invalid but I’m not invalid. J R Soc N Z. 2023;53(3):381–394.

- Graham R, Masters-Awatere B. Experiences of māori of aotearoa New Zealand’s public health system: a systematic review of two decades of published qualitative research. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2020;44(3):193–200.

- Salter K, Hellings C, Foley N, et al. The experience of living with stroke: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40(8):595–602.

- Kneebone II. Stepped psychological care after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38(18):1836–1843.

- Denham AMJ, Wynne O, Baker AL, et al. The long-term unmet needs of informal carers of stroke survivors at home: a systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(1):1–12.

- Boland P, Levack WMM, Graham FP, et al. User perspective on receiving adaptive equipment after stroke: A mixed-methods study. Can J Occup Ther. 2018;85(4):297–306.

Appendix A.

Search terms

1. stroke OR “cerebrovascular accident” OR “cerebrovascular disease” OR CVA OR hemiplegia OR aphasia (Title-Abstract-Keyword) AND

2. adjust* OR identity OR recovery OR rehabilitation OR “life after” OR “quality of life” OR “self-management” OR “self management” OR experienc* OR satisfaction OR hope OR wellbeing OR identity OR psychosocial OR “well-being” OR “lived experience” OR “liv* well” OR impact OR relation* OR “social support” (Title-Abstract-Keyword) AND

3. qualitative OR “grounded theory” OR phenomenolog* OR ethnograph* OR interview* OR “focus group*” OR “thematic analysis” OR “content analysis” OR narrative OR “lived experience” OR “interpretive description” OR wananga OR hui OR “mixed methods” OR “Kaupapa Maori” (Title-Abstract-Keyword) AND

4. aotearoa OR “new zealand” OR Māori OR “pacific island*” OR Pasifika OR Indigenous OR fiji* OR samoa* OR tonga* OR native (Title-Abstract-Keyword) AND

5. Aotearoa OR “New Zealand” OR Maori (all text)