Abstract

Purpose

Individuals from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds experience poorer outcomes following traumatic brain injury (TBI), including poorer quality of life. The reasons for these poorer outcomes are unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to qualitatively investigate the experience of injury, rehabilitation, and recovery amongst individuals from a CALD background following TBI.

Materials and methods

Fifteen semi-structured interviews were conducted, and qualitatively analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results

It was demonstrated that: (a) the cognitive and behavioural consequences of TBI were accompanied by stigma and loss of independence; (b) participants held many beliefs related to their TBI, ranging from bad luck to acceptance. Participants’ personal values and beliefs provided strength and resilience, with many viewing the injury as a positive event in their lives; (c) participants were appreciative of the high standard of care they received in hospital and rehabilitation, although communication barriers were experienced; (d) many participants identified with Australian culture, and few believed their cultural background negatively impacted their experience of TBI; (e) external support, particularly from family, was considered central to recovery.

Conclusion

These findings offer insight into the challenges CALD individuals face and factors that may facilitate their recovery and improve functional outcomes.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Access to family support is very important to individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI) from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds.

Education of family and close others is important to minimise stigma following TBI.

Healthcare services should provide competent and qualified interpreters for individuals with TBI who cannot speak English.

Rehabilitation professionals should receive cultural competency training, to maximise cultural sensitivity of their care provision to individuals from CALD backgrounds.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant cause of death and disability globally [Citation1]. Ongoing consequences of TBI include impaired physical, cognitive, and behavioural functioning, as well as emotional changes [Citation2,Citation3]. Such impairments impact daily functioning, including capacity for functional independence, work, study, leisure and relationships [Citation4,Citation5]. There are numerous factors associated with outcomes following TBI, including injury severity [Citation6,Citation7], age [Citation8,Citation9], education [Citation10,Citation11], premorbid intelligence [Citation12,Citation13], and cultural background [Citation14,Citation15].

Australia’s society is culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD); 26% of Australians are born overseas, and 21% of those born overseas speak a language other than English [Citation16]. Potential barriers experienced by individuals from CALD backgrounds in accessing healthcare services include language barriers [Citation17,Citation18], problems with accessibility [Citation19], fear of stigma or discrimination [Citation20], and culturally associated health beliefs [Citation21].

Individuals from different cultural backgrounds hold attitudes and beliefs towards illness and injury that influence how they conceptualise illness, interpret and experience symptoms, and access healthcare services [Citation19,Citation22]. Therefore, beliefs may influence the outcomes of illness and injury [Citation23–26]. For example, societies that are largely influenced by Western European culture, typically consider individuals responsible for their health [Citation27], whilst some traditional, non-Western cultures attribute illness to external entities, such as supernatural causes, or religious interpretations. Therefore illness and recovery may not be considered the individual’s responsibility [Citation22].

Studies comparing the outcome in ethnic minorities, such as African Americans and Hispanics, with those of White Americans, in the United States indicate that these minorities experience significantly worse post-injury functional independence [Citation28,Citation29], productivity [Citation28,Citation29], and community integration [Citation28,Citation29], and report more depression [Citation30] and poorer quality of life and life satisfaction, post-injury [Citation28,Citation29]. However, these findings may be confounded by socioeconomic disparities that influence access to healthcare and rehabilitation services in the US [Citation31].

When participants are of similar socioeconomic status (SES), with similar access to rehabilitation, the cultural background may still influence the outcome [Citation15]. Studies conducted in Australia found that compared to English-speaking individuals with TBI, individuals from a CALD background, born in a non-English-speaking country, reported lower functional independence, social integration, and problem-focused coping. CALD participants also reported greater anxiety and depression symptoms post-injury [Citation14,Citation32], and were more likely to attribute their injury to external factors, such as karma or God [Citation32].

The reason for these differences in outcome occurring in the context of apparent equal access to rehabilitation remains somewhat unclear. Qualitative research offers the opportunity to explore the experience of TBI from the survivor’s perspective, which may shed more light on this issue [Citation33,Citation34]. However, such research has been limited. A series of studies assessing the experience of TBI in Botswana [Citation35–37], found that many individuals attributed their injury to spiritual causes, such as witchcraft, or religious interpretations. Participants sought help from traditional doctors, who utilised spiritual treatments. While families of individuals with TBI provided greater support and care than is typical in high-income countries, extended families avoided contact, due to shame, which socially isolated the individuals with TBI and their families.

The single Australian qualitative study by Simpson et al. [Citation38] investigated cultural understanding of TBI and the experience of rehabilitation in a sample of Italian, Vietnamese, and Lebanese individuals. Participants reported typical cognitive, physical, and psychosocial TBI sequelae. However, little is known of the experience of Australian CALD individuals with TBI beyond rehabilitation.

Considering the national health impact of TBI in Australia [Citation39], the multicultural nature of its population, and the apparent cultural disparities in functional outcome [Citation14,Citation32], there is a need to understand from a qualitative perspective, the experience of TBI amongst individuals from a CALD background, both within rehabilitation and beyond. This may highlight themes that explain the differences in outcome, in turn, allowing implementation of more culturally tailored rehabilitation strategies, to enhance functional outcomes and quality of life for CALD TBI populations. Therefore, this study aimed to qualitatively explore the experience of injury, rehabilitation, and longer-term recovery in individuals from a CALD background following TBI.

Methods

Participants

Fifteen individuals from a CALD background were recruited from the Longitudinal Head Injury Outcome Study, conducted at Epworth Healthcare in the context of a no-fault accident compensation system, which provides multidisciplinary rehabilitation to individuals injured in transport- or work-related accidents. To be eligible, participants had to: (a) have sustained a moderate to severe TBI, with PTA >24 h (b) be at least 18 years old; (c) be >6 months post-injury; (d) be born in a non-English speaking country (i.e., other than Australia, New Zealand, England, North America, etc.); and (e) have the cognitive ability to participate in an interview with or without an interpreter. Participants were purposively sampled based on country of birth, to ensure a diverse range of experiences was captured [Citation40,Citation41].

Procedure

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval No. RES-19-0000099E). For eligible individuals consenting to be contacted for research, the database was consulted to determine whether they required an interpreter. Individuals were contacted via telephone and given a brief description of the study. Prior to interviews, participants received consent forms to sign, and the interview schedule, to allow them time to contemplate their responses to questions.

Data were collected from May to July 2021. Interviews were semi-structured, with mostly open-ended questions to allow participants to discuss aspects of their experience most meaningful to them. Interviews were conducted at Epworth Healthcare or via teleconferencing platforms, due to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. All interviews were audio-recorded using a voice recording application on a mobile phone. Interviews lasted an average of 50 min (ranging from 31 to 82 min). The first two interviews were conducted by a researcher experienced in qualitative interviews, who is not listed as an author in the current paper. Interviews 3–15 were conducted by a trained student psychologist, under the supervision of an experienced researcher. No participants required an interpreter.

The interview schedule was developed by the research team (including a neuropsychologist with over 30 years’ experience in rehabilitation following TBI including previous CALD research, a Senior Research Fellow with over 10 years’ experience in rehabilitation following TBI, and a Psychology research student). Interview questions were based on prominent areas of focus of previous research assessing the impacts of TBI amongst individuals from a CALD background (i.e., areas of life affected by the injury) [Citation14,Citation32,Citation35,Citation36,Citation38]. Questions aimed to encourage participants to reflect on: their experience of what caused their injury, the acute hospital and rehabilitation, the role of their cultural background and support from family post-injury, and what assisted their recovery (see Supplementary Material 1). As participants were from non-English speaking backgrounds, questions were phrased using plain language to allow for ease of understanding. The interview schedule was revised twice throughout the study, through collaborative discussions amongst the research team, regarding whether questions evoked responses that adequately addressed the research aim.

Data analysis

A reflexive thematic analysis was conducted in accordance with the six-phase, recursive process described by Braun and Clarke [Citation42]. Analysis of data was based on a critical realist theoretical foundation, which acknowledges an individual’s reality but recognises the influence of social factors, such as political and cultural contexts. As such, participants’ experiences were regarded as true, but the influence of social context was acknowledged [Citation43]. Analysis of interview data was inductive, and themes were derived from explicit data content, minimising the extent to which the researcher’s theoretical knowledge influenced data interpretation. Transcription and coding occurred concurrently throughout the interview process. The software program NVivo 12 [Citation44] was used to facilitate the process of coding and analysing interview data.

Phase one, data familiarisation, involved frequent transcript readings. Phase two involved organising data into initial codes using NVivo. Whilst transcripts were read by all authors, data were coded by a single author. The coding structure was reviewed and reorganised through collaborative discussions among authors. Phase three involved rearranging and discarding codes and organising them into preliminary themes. Themes were produced at the semantic level or based on surface-level meaning. Consistent with the recursive nature of reflexive thematic analysis, phase two was frequently revisited, as transcripts continued to be coded and re-coded. Phase four involved further refining potential themes. Phase five involved naming and defining the final themes. Additionally, a thematic map was created, and revised, to display relationships between themes and sub-themes. Finally, phase six involved selecting relevant extracts that were representative of themes and sub-themes.

The adequacy of the sample and the data provided was evaluated throughout the research process. At interview 15 it was determined that the data collected was rich enough to address the research aims and extend upon current knowledge [Citation45–47]. As such, no further participants were recruited (see Supplementary Material 2 for further information regarding the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies).

Results

Participants’ years living in Australia at the time of interviews ranged from 2 years to 69 years (M = 19.1, SD = 17.8). Participants were purposively sampled from 13 countries. No participant required an interpreter. Time post-injury ranged from 2 to 20 years (M = 7.2, SD = 5.2). A comprehensive list of participant characteristics is provided in .

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Thematic map

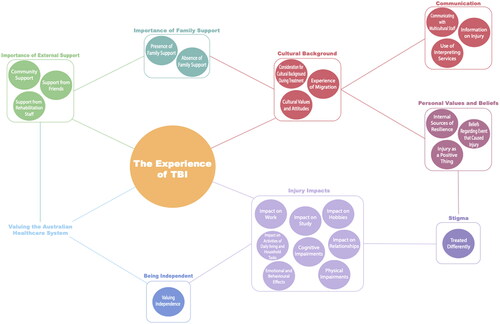

In total 248 initial codes were organised into 34 nodes. Nine themes were created: injury impacts, being independent, valuing the Australian healthcare system, importance of external support, importance of family support, cultural background, communication, personal values and beliefs, and stigma. Each theme and associated subthemes are displayed in . Themes and subthemes are described and followed by participant quotes adhering to the format of (participant number, and country of birth). Square brackets are used to provide clarification. For brevity, portions of some quotes were omitted; ellipses … are used to indicate such instances.

Figure 1. Thematic map of interrelationships between key themes and subthemes.

Injury impacts

Typical physical, cognitive, emotional and behavioural impairments associated with TBI were experienced. These impairments impacted various aspects of life including activities of daily living and household tasks, work, study, social relationships, and hobbies.

Physical impairments

Chronic pain due to bodily injuries was commonly reported. Physical impairments related to the TBI included headaches, fatigue, vertigo, seizures, weakness in limbs, and sensory issues, “I lost my sense of smell” (P7, Turkey).

Cognitive impairments

Most participants experienced cognitive impairments including difficulties with short-term memory, concentration, processing speed, and multi-tasking, “So, thinking speed has dramatically gone slower” (P10, Thailand).

Emotional and behavioural effects

Participants reported a variety of emotional changes following injury, including difficulties with emotional regulation and greater mood fluctuations. Mental health problems were experienced by some, with anxiety most commonly reported, “I became very, very anxious and had this terrible, terrible sense of dread” (P6, Italy).

Following the injury, participants experienced initial frustration as they adjusted to their impairments, including irritability and a limited temper threshold, “for the first few years I was short-tempered. I think that was because I was getting frustrated with myself not being able to remember things, not being able to do certain things” (P7, Turkey).

Some participants experienced changes related to how they interacted with others, and personality changes, “before the accident, I used to be very, very serious with everything. But now, I’m a bit humorous … So, my personality has changed a bit” (P3, India).

Impact on work

Some participants encountered difficulties returning to work. These are often related to physical or cognitive impairments which interfered with work performance. Such difficulties often necessitated a career change, “I wasn’t able to go back to something I could do before. So, I had to think about what I wanted to do” (P15, Mauritius).

Impact on study

Cognitive impairments made resuming studies difficult for some, “I started to go back to my study and was like blacking out, nothing was going in, I just had to get out of class” (P13, Nepal). Despite these challenges, many participants still managed to complete their studies, though some required more time.

Impact on relationships

Emotional and behavioural changes presented challenges to relationships, sometimes resulting in the loss of such relationships, “I was engaged, but I broke up with him because of the brain [injury]–we couldn’t get al.ong” (P5, Ethiopia).

Some participants reported engaging in social activities less, following their injury, “socialising has changed since pretty much day one after the accident … even though I’m sitting with two or three people, I feel like I’m sitting by myself because I don’t feel like I’m connected” (P10, Thailand).

Participants who were parents often experienced changes to their role as a parent and struggled to care for their children upon returning home from rehabilitation, “She used to just ignore me, my daughter. She knew I was her mother, but maybe she had a bit of anger or something in her mind that I had been away for that long” (P12, India).

Impact on activities of daily living and household tasks

Participants reported difficulties completing household tasks such as cooking and cleaning. Tasks that could not be completed by participants were often completed by carers, or family members, “I cook with a carer. Even now, still I’m not left alone to cook because I forget the stoves on. I still have carers to assist with cooking” (P5, Ethiopia).

Impact on hobbies

Some participants lost interest in previously enjoyed activities, whilst for others, their hobbies and interests changed, “I was a coin and stamp collector, and my hobbies was computer programming. And after my accident, ever since athletics, my hobbies are more into fitness and diet, and church activities” (P3, India).

Being independent

Valuing independence

Many participants felt independence was important, and valued being able to depend on and support themselves, “I want to be independent and go out and live my own life as well. I want to be a mother or wife, but I want to make my own identity as well” (P12, India).

Depending on others made some feel like a burden, “I actually feel guilty to let my family worry about me ‘cause I’m always being independent by myself before” (P8, China).

Some felt they received too much support, preventing them from regaining independence:

My friends and family quite annoyingly babied [me] to the extent of thinking you can’t do anything. People are unsure what your capabilities are, if you can do anything, they want to try to help but they end up doing too much. (P15, Mauritius)

Valuing the Australian healthcare system

Participants acknowledged and were grateful for the high standard and quality of care that the Australian healthcare system provided, “we are extremely lucky in Australia … we have a fantastic medical system” (P9, South Africa), “bottom line, if this had happened back in India, I would not have survived, or never been properly rehabilitated” (P2, India).

Participants valued the social aspect of rehabilitation. Connecting with other patients provided social support and validation of their experience:

Being able to interact, there were guys in there that would never walk again, now if I was in hospital and that was me, I would have thought the world was over, but when you’re talking to other people in the same boat as you, you go “right, there might be a bit of light at the end of the tunnel, because I’m not sort of isolated”. (P7, Turkey)

Cultural background

Experience of migration

Some participants had migrated to Australia to pursue study or work opportunities, whilst others were leaving negative circumstances. For some participants, their experience of migration taught them resilience. Participants drew on this following their injury:

And we came out by ship and it was very traumatic … that’s still a very important issue, that migration. It really is traumatising … it helped me to have learnt those things and I think coming out as a migrant had a lot to do with [strength]. (P6, Italy)

Consideration for cultural background during treatment

Participants’ cultural backgrounds were acknowledged by hospital staff to variable degrees. Some felt their cultural background, specifically dietary preferences, were not considered, whilst others felt their background and religious practices were acknowledged, “they kept on asking if it’s allowed or do you prefer only the female carers, the female staff or you got some religious things happening” (P12, India).

Cultural values and attitudes

Participants’ cultural values and attitudes influenced their experience of their injuries. For some participants, their cultural values made them more resilient and able to cope with adversity, “with Indians, they are very resilient. They never back down. I mean, with anything, if they wanna get it done, they get it done … it might have been my culture, my Indian attitude to never back down” (P3, India).

For others, cultural norms regarding the participant’s position in their family, such as emphasis on the oldest or youngest child, influenced their experience of their injury:

In Thailand and I think majority of Asian environment, being the youngest usually get the love and care from the rest of the member. There’s always a perception from the other–the older people say, “They’re youngest. They wouldn’t be able to do this. We need to give them help and assist them”. (P10, Thailand)

Importance of family support

Every participant considered support from family to be central to the experience of their injury and recovery. The importance of family was demonstrated either by the presence of family and their support, or the consequences of their absence, “I think for most people, if the patient can have the family and their loved one, as long as they can be with the patient, I think that’s gonna benefit the patient with recovery and stuff” (P10, Thailand).

Presence of family support

Many participants were living in Australia without family at the time of their injury. However, for many, their families rushed to Australia immediately following the injury, and were present throughout the acute hospital experience, rehabilitation, and some time following rehabilitation discharge, “they were very shocked initially because they were in India, but they flew over to Melbourne and were there by my side in ICU every day” (P3, India).

Most participants believed they received an abundance of support from their families and many largely attributed their recovery to this support, “I think [rehabilitation] and family was a big reason why I was able to do what I could and get to where I could now” (P15, Mauritius).

During hospital and rehabilitation, the role of the family was often to provide comfort and emotional support. Participants who were parents, their spouse, parents, and in-laws often took care of their children whilst they were an inpatient. Upon rehabilitation discharge, family members provided care and assistance to participants in their homes, ranging from emotional support to practical assistance with mobility and household tasks.

For some participants, their families permanently moved to Australia to provide care following the injury:

My sister as well, and the thing is, when she decided to stay here, that is a big thing for me, because being here by myself for too long, it’s just good to have someone that your family here as well. (P4, Vietnam)

Absence of family support

Some participants found living in Australia without family to be a lonely experience, and for some, hospital and rehabilitation was characterised by loneliness as family could not always be present, “most of my family in China … I’m not actually happy by myself” (P8, China).

For some participants, their family members eventually returned home, whilst for others, their family could not visit Australia at all. Participants believed the support their family provided whilst overseas was very limited:

I really probably just mention that support from family and the close one really helped me a lot. I guess in a way that because my family, they live overseas so the extent of time they come and [support] me wasn’t really that long, but they helped me through recovery. (P10, Thailand)

Importance of external support

Support from rehabilitation staff

Many participants felt the support provided by rehabilitation staff exceeded the typical care expected, “they had enough faith to steer me in the right direction and motivate me to keep pushing myself” (P15, Mauritius).

Community support

Participants received practical and moral support from various communities, including work, school, religious, and cultural communities:

I’m from Pakistan and I belong to this community. It’s big in Pakistan … so my whole community was here. And so, they came and visited me all the time at [hospital] … I know a lot of people through that community who came and saw me. (P11, Pakistan)

Support from friends

Participants felt their friends provided comfort during rehabilitation, and practical support and assistance upon rehabilitation discharge, “I had friends and cousins come as well. So I think I was quite lucky ‘cause I know some people there that didn’t have many visitors at all. I think that changes the outcome of how things work” (P15, Mauritius).

Communication

All participants were from non-English speaking backgrounds and spoke English to varying degrees. Some participants utilised interpreting services during treatment, whilst others played the role of an interpreter, communicating medical information to their families. Finally, some participants encountered difficulties communicating with medical staff during hospital or rehabilitation.

Use of interpreting services

Many participants were offered interpreting services during their time in hospital or rehabilitation, though some felt they did not require these services, or preferred to communicate in English, “because I lived here long I understand the terminology kind of stuff, it’s maybe easy for me, but someone come like two to five years, then they need some” (P14, Sri Lanka).

Some participants did utilise interpreting services however they felt the interpreter lacked competence:

I got an interpreter, but the thing is, I’m from the North, and that person from the South, and I feel like my English is better than him … I did feel like I need, but then after I actually have him, I just realised no this worse. (P4, Vietnam)

Communicating with multicultural staff

For some, the presence of multicultural and multilingual medical staff was valued by participants and their families. Some staff spoke the participant’s native language, easing communication:

It was really good because one of the doctor who was in the ward, she was also from India. Before going back home, she used to come, she used to talk in our own language sometimes. She used to say, “If you got any concern, if you’re not finding the word, you can speak in Punjabi with me”. (P12, India)

Information on injury

In relation to the information provided by medical staff, participants felt that the prognoses they were given were often negative and conveyed a sense of hopelessness:

Medicine was saying, “Well, all you can do is stay on medication and be dependent on someone else” … even the psychiatrist said to me, “Look, there’s nothing I can do for you except that you stay on your medications”. (P6, Italy)

Even though they tried to explain it quite slowly and quite easily to understand, my brain wasn’t really fully registering and I just half-absorbed the information … English is my second language, right? So it was always gonna be more difficult, but at that point of time, even when they translated into Thai, which is my first language, I still struggle to understand. (P10, Thailand)

Personal values and beliefs

Beliefs regarding the event that caused the injury

Many participants had an attitude of resignation and acceptance towards their injury and the event that led to it, “these things happen. I know they shouldn’t, but an accident is an accident … this is life, these things happen, you just have to accept them” (P7, Turkey).

Some participants attributed the cause of their injury to themselves, while others felt it was due to other’s actions. Some participants believed luck played a role in their experience of their injury. Some felt their injury could be attributed to chance, whilst others felt lucky to have survived, “I just think that I’m kind of like a lucky guy but unlucky guy at the same time. So, it was kind of lucky but unlucky experience for me” (P8, China).

Some participants held religious interpretations of their injury:

The devil had planned to kill me, but God protected me. So because I’m faithful that I’m a Christian, God brought me back to life … so my time hasn’t come, that’s why God brought me back because I had less than 20% chance to survive. (P5, Ethiopia)

Injury as a positive thing

Whilst many participants did not view the experience of the injury itself as positive, they believed it was a catalyst for positive change in their lives, “I tell a lot of people that accident was the best thing to ever happen to me” (P7, Turkey).

Many participants reported that the injury completely changed their outlook on life. Participants felt grateful to be alive. Many re-evaluated their priorities in life and realised what was important to them:

As traumatic as the experience was, you can sit down and dwell on how bad I was through the accident, and everything I went through, or you can look at it and say “look, this is what I went through, and look at the way I’ve come out”, I was very grateful for a lot of things … your whole perspective on life changes, the little things you take for granted are now amazing. (P7, Turkey)

For others, their injury led to great achievements they did not think possible:

I’ve been proving my doctors wrong with pretty much everything. My doctor said–’cause I crushed my foot really bad, I can’t go back to walking or running, anything. I said, “Okay, I can prove you wrong.” So now, I’m a professional athlete … since my accident in 2011 up until now, I win 15 gold medals. And I was never ever into sports prior to the accident. (P3, India)

Internal sources of resilience

For many participants, their beliefs and attitudes provided them with strength, which influenced how they viewed their injury and dealt with subsequent challenges. Some compared their injuries and circumstances to those of other patients during hospital and rehabilitation. This often provided perspective and elicited gratitude in instances where the injury or circumstances of other’s was considered worse, “I was like doing rehabilitation with a lot of young twenty-year-olds who are now amputees because of their accidents, and I thought ‘wow I’ve got it really lucky’” (P7, Turkey).

For some participants, their faith in themselves, and their positive thinking provided them with a strong sense of determination to recover, “I would say it’s just sheer determination and faith that keeps you going … I mean we have to be consistent and never think negative, and just have a bit of faith” (P3, India).

Some participants reported their faith in God provided them with a source of strength:

Faith in God because I mean that just gives you a bit of positive energy and upliftment and motivation to just go ahead and strive for something better … I attribute [recovery] to my hard work, but that was because of my faith that prompted me doing all this. (P3, India)

Stigma

Most participants believed they were treated differently by others following their injury, and felt they were viewed as disabled. Some felt they were discriminated against for their impairments, whilst others felt they were treated as fragile and were overprotected, “I don’t like to be considered as disabled, I love to be healthy, I always try to be the best of myself” (P4, Vietnam).

Participants felt their friends, family, and members of the wider community lacked an understanding of TBI:

A brain injury it is invisible injury … so they don’t know, they don’t see … they think, especially, in our community they don’t understand what is brain injury … so for our people, our African community, when they think brain injury, they think you are crazy. (P5, Ethiopia)

Treated differently

Most participants believed they were treated differently due to their injury. Some were treated as fragile and were overprotected, whilst others were discriminated against, particularly in the context of employment, “they didn’t reply back when they heard that I have the brain injury” (P12, India).

Some participants believed they were treated differently by others in their cultural community due to cultural beliefs and interpretations of their injury. Some participants were viewed as crazy, whilst others were renowned for defeating death, “I was a celebrity back in India. So, when I landed in the airport, when I came out, there were these drummers playing drums because I mean I just–in a way, defeated death” (P3, India).

Discussion

This study aimed to qualitatively investigate the experience of injury, rehabilitation, and recovery amongst individuals from a CALD background following TBI. Many themes extended across the entire experience of TBI. Whilst some themes represented the typical consequences of TBI, others were unique to participants’ cultural backgrounds.

Participants experienced the typical physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioural changes associated with TBI, which subsequently impacted various areas of their lives. This experience is typical for both culturally diverse [Citation37,Citation38], and English-speaking TBI populations [Citation48–50]. The such universal experience of TBI sequelae, irrespective of cultural background, is likely explained by the underlying pathophysiology of brain injury [Citation38].

Whilst previous research did not characterise a loss of independence or increased reliance on others as distressing [Citation48,Citation49,Citation51], the CALD sample in this study was particularly distressed by their loss of independence. Participants experienced guilt and shame for relying on others, as they considered themselves a burden. This may have reflected the common expectation in non-Western collectivist cultures that one must sacrifice their personal needs and prioritise the interests of the group [Citation52,Citation53].

Participant’s typically endorsed Western beliefs regarding the cause of their injury, rather than traditional, non-Western beliefs [Citation22]. However, participants had lived in Australia for an average of 19 years and were likely acculturated, adapting their beliefs and values to those of Australian society [Citation54]. The one participant who held religious interpretations of their injury had only lived in Australia for two years. Therefore, they may have been less acculturated, endorsing religious beliefs known to be widely held throughout Africa, as informed by studies conducted in Botswana [Citation35–37].

The findings that participants were appreciative of the care they received are consistent with findings that both CALD [Citation38], and English-speaking individuals [Citation51,Citation55] generally report positive attitudes towards rehabilitation. Whilst participants appreciated the care they received; some participants felt that their cultural background was not considered during treatment. Much research has identified that Western healthcare services often fail to provide culturally competent care or consider a patient’s specific cultural needs [Citation56,Citation57]. Such findings necessitate cultural competency training for healthcare professionals, to improve their capacity to provide culturally appropriate care [Citation58,Citation59]. Furthermore, hospital discharge processes, policies and procedures for care provision (e.g., NDIS) also need to be culturally sensitive.

The findings that participants had negative experiences with interpreting services are consistent with previous studies [Citation18,Citation54]. However, previous research indicated negative experiences related to the discomfort felt in the presence of interpreters [Citation18,Citation54], whilst those expressed in this sample related to interpreters’ lack of competence. Where interpreting services were not available, bilingual family members often interpreted information. Such experience is common within the context of the Australian healthcare system, where interpreting services are seldom available [Citation18,Citation20]. However, problems may arise from untrained relatives incorrectly interpreting information [Citation20]. These findings necessitate the use of competent and qualified interpreters, ideally with appropriate training as health interpreters [Citation60].

Another communication barrier related to difficulties understanding the complex information provided by medical staff. Such findings are consistent with those of Simpson et al. [Citation38], where individuals from a CALD background experienced difficulty understanding medical terminology, even after information had been interpreted. Such findings demonstrate the need to improve communication between CALD patients and therapy staff. Studies suggest that many health professionals feel ill-equipped to communicate information to patients with poor health literacy, often due to a lack of formal training [Citation61–63]. Considering poor health literacy is associated with negative health outcomes [Citation64], it is essential that all health professionals are trained to communicate medical information to patients, in a way that is accessible and easily understood.

In relation to factors that facilitated recovery, participants’ values and beliefs often served as a source of strength to cope with the challenges of TBI. Such findings are consistent with those of English-speaking populations [Citation55,Citation65,Citation66], which identified that spirituality, optimism, and gratitude, often provided individuals with inner strength to recover, following TBI. Indeed, research suggests that an optimistic attitude following TBI is positively associated with favourable outcomes [Citation67]. Whilst it is unclear how such attitudes develop, the use of interventions that aim to foster positive attitudes, may enhance recovery following TBI [Citation55].

Additionally, many participants attributed their recovery to support from others. Participants valuing support and encouragement from rehabilitation staff is consistent with both CALD [Citation38], and English-speaking [Citation68] samples, where characteristics of warmth, friendliness, and enthusiasm were valued. Additionally, participants’ respective communities provided moral support and practical assistance. These findings are somewhat consistent with Simpson et al. [Citation38], where individuals’ cultural communities were generally supportive, however, some lacked an understanding of TBI, and subsequently stigmatised the injured individual. Additionally, emotional support from friends was highly valued. Such support is positively associated with greater quality of life and psychological wellbeing, following TBI [Citation69,Citation70].

Support from family was of profound importance to participants throughout their experience of TBI. Consistent with findings for both CALD [Citation38], and English-speaking samples [Citation55,Citation69], the role of family was often to provide emotional and practical support during hospital and rehabilitation, and following rehabilitation discharge. Whilst families have similar roles across cultures, non-Western cultures tend to place greater emphasis on family [Citation56], therefore the family of individuals from a CALD background may tend to be more involved throughout the experience of TBI, and provide greater care than families in Western cultures [Citation36,Citation37].

However, for some participants, their families could not be present in Australia, whilst others experienced conflict with their family. These findings are similar to those of Simpson et al. [Citation38], suggesting that despite the cultural emphasis on family, such support may not always be available. The issue of distance between the CALD individual and their family may be addressed using technological means, such as mobile phones and videoconferencing applications, such as FaceTime, to allow for more frequent interactions [Citation71,Citation72]. However, videoconferencing may not offer the same level of support as the physical presence of family; therefore the provision of funding to support families to visit their injured loved ones may prove beneficial.

In addition to limited support from family, participants’ recovery may have been impeded by their experience of stigma. Stigma, shame, and social isolation are common experiences for culturally diverse populations [Citation35–38]. Stigma often stemmed from others’ lack of understanding of TBI, or the perception that brain injury is associated with madness, highlighting the need to address stigma and reduce its impact on individuals from a CALD background. Stigma within CALD communities may be addressed through collaboration between health professionals and CALD community leaders to raise awareness regarding TBI. Additionally, stigma from close others may be addressed through the provision of psychoeducation to families through rehabilitation programmes, to help them better understand TBI.

This study was limited in that participants with accident-related injuries were treated in the context of a no-fault accident compensation system funded by the Transport Accident Commission (TAC). Therefore, participants received unlimited medical care, rehabilitation, ongoing therapies, and support returning to work or study. This level of support is not typically provided in other states and territories of Australia, or internationally [Citation73]. Therefore, the findings of this study, may not reflect the typical experience of individuals from a CALD background. Future studies could qualitatively investigate the experience of TBI amongst individuals from a CALD background with less access to comprehensive support and/or injuries due to other causes.

Additionally, all participants had been injured in motor vehicle or work-related accidents, therefore findings may not generalise to accidents due to other causes. Additionally, at the time of interviews, participants had lived in Australia for an average of 19 years, all were proficient in English, and many had completed tertiary education. Therefore, this sample may not be representative of the typical CALD TBI patient. Additionally, as education is related to better functional outcomes following TBI [Citation10], this well-educated sample may have experienced better outcomes than what is typical for TBI patients [Citation74]. We experienced many challenges in recruiting less acculturated individuals and acknowledge this as a study limitation. Future studies could attempt to recruit a more diverse sample in relation to educational attainment, English proficiency, and years living in Australia.

Conclusion

This study offers insights into the challenges faced by individuals from a CALD background who sustain a TBI, and factors that may facilitate their rehabilitation. CALD individuals experienced the typical consequences of TBI. Support from others, and particularly family, was central to the entire experience of TBI, and facilitated recovery. Additionally, personal values and beliefs provided strength to participants throughout the entire experience of TBI. Participants were appreciative of the care they received during hospital and rehabilitation, however, there were some communication barriers, including medical staff’s complex terminology, and negative experiences with interpreters. Recovery was impeded by limited support from family, and the experience of stigma. These findings may be used to educate clinicians working with individuals from a CALD background at various stages of recovery, so that medical care, rehabilitative interventions, and follow-up support can be more culturally relevant. This in turn could allow treatment to better meet the needs of a CALD TBI population, improve their functional outcomes and quality of life, and reduce cultural disparities in functional outcomes that exist between CALD and non-CALD individuals with TBI.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (150.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, et al. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2019;130(4):1080–1097.

- Rabinowitz AR, Levin HS. Cognitive sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(1):1–11.

- Sabaz M, Simpson GK, Walker AJ, et al. Prevalence, comorbidities, and correlates of challenging behavior among community-dwelling adults with severe traumatic brain injury: a multicenter study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29(2):19–30.

- Diaz AP, Schwarzbold ML, Thais ME, et al. Psychiatric disorders and health-related quality of life after severe traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(6):1029–1037.

- Ponsford JL, Sinclair KL. Sleep and fatigue following traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2014;37(1):77–89.

- Pavlovic D, Pekic S, Stojanovic M, et al. Traumatic brain injury: neuropathological, neurocognitive and neurobehavioral sequelae. Pituitary. 2019;22(3):270–282.

- Wilson BA. Brain injury: recovery and rehabilitation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2010;1(1):108–118.

- Dhandapani S, Manju D, Sharma B, et al. Prognostic significance of age in traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3(2):131–135.

- Wood RL, Rutterford NA. Demographic and cognitive predictors of long-term psychosocial outcome following traumatic brain injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2006;12(3):350–358.

- Levin HS, Temkin NR, Barber J, et al. Association of sex and age with mild traumatic brain injury–related symptoms: a TRACK-TBI study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e213046.

- Seagly KS, O’Neil RL, Hanks RA. Pre-injury psychosocial and demographic predictors of long-term functional outcomes post-TBI. Brain Inj. 2018;32(1):78–83.

- Fraser EE, Downing MG, Biernacki K, et al. Cognitive reserve and age predict cognitive recovery after mild to severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2019;36(19):2753–2761.

- Ritter J, Dawson J, Singh RK. Functional recovery after brain injury: independent predictors of psychosocial outcome one year after TBI. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021;203. DOI:10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106561

- Ponsford J, Downing M, Pechlivanidis H. The impact of cultural background on outcome following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2020;30(1):85–100.

- Saltapidas H, Ponsford J. The influence of cultural background on motivation for and participation in rehabilitation and outcome following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22(2):132–139.

- Cultural diversity in Australia, 2016. Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2017. (No. 2071.0).

- Clark A, Gilbert A, Rao D, et al. Excuse me, do any of you ladies speak english?’ perspectives of refugee women living in South Australia: barriers to accessing primary health care and achieving the quality use of medicines. Aust J Prim Health. 2014;20(1):92–97.

- Hadgkiss EJ, Renzaho AMN. The physical health status, service utilisation and barriers to accessing care for asylum seekers residing in the community: a systematic review of the literature. Aust Health Rev. 2014;38(2):142–159.

- Hannah C, Le Q. Factors affecting access to healthcare services by intermarried Filipino women in rural Tasmania: a qualitative study. Rural Remote Health. 2012;12(4)

- Taylor J, Haintz GL. Influence of the social determinants of health on access to healthcare services among refugees in Australia. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24(1):14–28.

- Mead N, Roland M. Understanding why some ethnic minority patients evaluate medical care more negatively than white patients: a cross sectional analysis of a routine patient survey in English general practices. BMJ Open. 2009;339(sep16 3):b3450–b3450.

- Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Bakar RC. Cultural health attributions, beliefs, and practices: effects on healthcare and medical education. Med Educ. 2009;2(1):64–74.

- Banja J. Ethics, values, and world culture: the impact on rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 1996;18(6):279–284.

- Durie M. Understanding health and illness: research at the interface between science and indigenous knowledge. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(5):1138–1143.

- Reynolds S. Disability culture in West Africa: qualitative research indicating barriers and progress in the Greater Accra region of Ghana. Occup Ther Int. 2010;17(4):198–207.

- Sanders D, Kydd R, Morunga E, et al. Differences in patients’ perceptions of schizophrenia between Māori and New Zealand Europeans. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(6):483–488.

- Stanhope V. Culture, control, and family involvement: a comparison of psychosocial rehabilitation in India and the United States. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2002;25(3):273–280.

- Arango-Lasprilla JC, Rosenthal M, Deluca J, et al. Traumatic brain injury and functional outcomes: does minority status matter? Brain Inj. 2007;21(7):701–708.

- Arango-Lasprilla JC, Kreutzer JS. Racial and ethnic disparities in functional, psychosocial, and neurobehavioral outcomes after brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010;25(2):128–136.

- Perrin PB, Krch D, Sutter M, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health over the first 2 years after traumatic brain injury: a model systems study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(12):2288–2295.

- Tung EL, Hampton DA, Kolak M, et al. Race/ethnicity and geographic access to urban trauma care. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190138.

- Saltapidas H, Ponsford J. The influence of cultural background on experiences and beliefs about traumatic brain injury and their association with outcome. Brain Impair. 2008;9(1):1–13.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Lloyd V, Gatherer A, Kalsy S. Conducting qualitative interview research with people with expressive language difficulties. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(10):1386–1404.

- Mbakile-Mahlanza L, Manderson L, Ponsford J. Cultural beliefs about TBI in Botswana. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2017;27(1):38–59.

- Mbakile-Mahlanza L, Manderson L, Downing M, et al. Family caregiving of individuals with traumatic brain injury in Botswana. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(6):559–567.

- Mbakile-Mahlanza L, Manderson L, Ponsford J. The experience of traumatic brain injury in Botswana. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2015;25(6):936–958.

- Simpson G, Mohr R, Redman A. Cultural variations in the understanding of traumatic brain injury and brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2000;14(2):125–140.

- Pozzato I, Tate RL, Rosenkoetter U, et al. Epidemiology of hospitalised traumatic brain injury in the state of New South Wales, Australia: a population-based study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2019;43(4):382–388.

- Gentles SJ, Charles C, Ploeg J, et al. Sampling in qualitative research: insights from an overview of the methods literature. Qual Rep. 2015;20(11):1772–1789.

- Robinson OC. Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: a theoretical and practical guide. Qual Res Psychol. 2014;11(1):25–41.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589–597.

- Danermark B, Ekström M, Karlsson JC. Explaining society: critical realism in the social sciences. 2nd ed. London (UK): Routledge; 2019.

- NVivo. Version 12. Melbourne: QSR International Pty Ltd. 2018.

- Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13(2):201–216.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760.

- O’Reilly M, Parker N. ‘Unsatisfactory saturation’: a critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qual Res. 2013;13(2):190–197.

- Glintborg C, Thomsen AS, Hansen TGB. Beyond broken bodies and brains: a mixed methods study of mental health and life transitions after brain injury. Brain Impair. 2018;19(3):215–227.

- Hurst FG, Ownsworth T, Beadle E, et al. Domain-specific deficits in self-awareness and relationship to psychosocial outcomes after severe traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(5):651–659.

- Ljungqvist J. Somatic consequences. In: Sundstrøm T, Grände PO, Luoto T, Rosenlund C, Undén J, Wester KG, editors. Management of severe traumatic brain injury: evidence, tricks, and pitfalls. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 569–573.

- Glintborg C, Hansen TGB. Bio-psycho-social effects of a coordinated neurorehabilitation programme: a naturalistic mixed methods study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2016;38(2):99–113.

- Grossmann I, Na J. Research in culture and psychology: past lessons and future challenges. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2014;5(1):1–14.

- Ryan RM, La Guardia JG, Solky-Butzel J, et al. On the interpersonal regulation of emotions: emotional reliance across gender, relationships, and cultures. Pers Relats. 2005;12(1):145–163.

- Cavallo MM, Saucedo C. Traumatic brain injury in families from culturally diverse populations. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1995;10(2):66–77.

- Downing M, Hicks A, Braaf S, et al. Factors facilitating recovery following severe traumatic brain injury: a qualitative study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2021;31(6):889–913.

- Lequerica A, Krch D. Issues of cultural diversity in acquired brain injury (ABI) rehabilitation. NeuroRehabilit. 2014;34(4):645–653.

- Niemeier J, Arango-Lasprilla JC. Toward improved rehabilitation services for ethnically diverse survivors of traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2007;22(2):75–84.

- Lewis A, Bethea J, Hurley J. Integrating cultural competency in rehabilitation curricula in the new millennium: keeping it simple. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(14):1161–1169.

- Matteliano MA, Stone JH. Cultural competence education in university rehabilitation programs. J Cult Divers. 2014;21(3):112–118.

- Dikengil A, Jones G, Byrne MB. Orientation of foreign language interpreters working with brain-injured patients. J Cogn Rehabil. 1993;11(4):10–14.

- Ali NK, Ferguson RP, Mitha S, et al. Do medical trainees feel confident communicating with low health literacy patients? J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4(2). DOI:10.3402/jchimp.v4.22893

- Howard T, Jacobson KL, Kripalani S. Doctor talk: physicians’ use of clear verbal communication. J Health Commun. 2013;18(8):991–1001.

- Yin HS, Jay M, Maness L, et al. Health literacy: an educationally sensitive patient outcome. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1363–1368.

- MacLeod S, Musich S, Gulyas S, et al. The impact of inadequate health literacy on patient satisfaction, healthcare utilization, and expenditures among older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2017;38(4):334–341.

- Chamberlain DJ. The experience of surviving traumatic brain injury. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(4):407–417.

- Lefebvre H, Cloutier G, Levert MJ. Perspectives of survivors of traumatic brain injury and their caregivers on long-term social integration. Brain Inj. 2008;22(7-8):535–543.

- Powell T, Gilson R, Collin C. TBI 13 years on: factors associated with post-traumatic growth. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(17):1461–1467.

- Abrahamson V, Jensen J, Springett K, et al. Experiences of patients with traumatic brain injury and their carers during transition from in-patient rehabilitation to the community: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(17):1683–1694.

- McPherson K, Fadyl J, Theadom A, et al. Living life after traumatic brain injury: phase 1 of a longitudinal qualitative study. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33(1):44–52.

- Strandberg T. Adults with acquired traumatic brain injury: experiences of a changeover process and consequences in everyday life. Soc Work Health Care. 2009;48(3):276–297.

- Armstrong E, Coffin J, McAllister M, et al. ‘I’ve got to row the boat on my own, more or less’: aboriginal Australian experiences of traumatic brain injury. Brain Impair. 2019;20(2):120–136.

- Hines M, Brunner M, Poon S, et al. Tribes and tribulations: interdisciplinary eHealth in providing services for people with a traumatic brain injury (TBI). BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1). DOI:10.1186/s12913-017-2721-2

- Weisbrot D, Breen KJ. A no-fault compensation system for medical injury is long overdue. Med J Aust. 2012;197(5):296–298.

- Bastos JL, Harnois CE, Paradies YC. Health care barriers, racism, and intersectionality in Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:209–218.