?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose

To synthesize common or differing perceptions of patients’ and clinicians’ that influence uptake of online-delivered exercise programmes (ODEPs) for chronic musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions.

Methods

Eight databases were searched from inception to April 2023 for studies including (1) patients with and/or clinicians delivering ODEPs for chronic MSK conditions, and (2) synchronous ODEPs, where information is exchanged simultaneously (mode A); asynchronous ODEPs, with at least one synchronous feature (mode B); or no ODEPs, documenting past experiences and/or likelihood of participating in an ODEP (mode C). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklists were used to assess study quality. Perceptions of patients’ and clinicians’ influencing uptake of ODEPs were extracted. Quantitative and qualitative data were synthesised and integrated.

Results

Twenty-one studies were included (twelve quantitative, seven qualitative, and two mixed-methods) investigating the perceptions of 1275 patients and 534 clinicians on ODEP mode A (n = 7), mode B (n = 8), and mode C (n = 6). Sixteen of the 23 identified perceptions related to satisfaction, acceptability, usability, and effectiveness were common, with 70% of perceptions facilitating uptake and 30% hindering uptake.

Conclusions

Findings highlight the need to promote targeted education for patients and clinicians addressing interconnected perceptions, and to develop evidence-based perception-centred strategies encouraging integrated care and guideline-based management of chronic MSK conditions.

Implications for Rehabilitation

Almost 70% of perceptions related to satisfaction, acceptability, usability, and effectiveness that influence the uptake of online-delivered exercise programmes for chronic musculoskeletal conditions are shared by patients and clinicians.

Patient perceptions that differ from clinicians and that hinder uptake include the risk of misdiagnosis, lack of social support, and advice from their clinic and/or clinician.

Clinician perceptions that differ from patients and that hinder uptake include risk of last-minute appointment cancellations, the cost to set-up, and limitations of camera angles.

Implementation of online-delivered exercise programmes may be supported by targeted education for patients and clinicians that addresses misinformed perceptions.

Introduction

Chronic musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions are a leading cause of pain and disability, with a reported 19.6% increase in the global disability-adjusted life years between 2006 and 2016 [Citation1]. The increasing prevalence has resulted in a substantial economic, social, and functional burden on healthcare resources worldwide [Citation2]. In an effort to reduce this burden, clinical practice guidelines for the management of chronic MSK conditions have been developed, recommending non-pharmacological management (i.e., exercise) as the first intervention method [Citation3]. However, uptake of clinical practice guidelines has been slow resulting in an evidence-to-practice gap [Citation4]. For example, Zadro et al. [Citation5] found that 43% of physiotherapists’ treatments for the management of MSK conditions did not align with guidelines. This may be influenced by health systems and policies, professional training, lack of specificity of guidelines, and consumer participation and engagement [Citation6].

Strategies to address the slow uptake of clinical practice guidelines have been explored. These include delivering self-management exercise programmes that have previously resulted in the provision of care that is more in line with guidelines [Citation7]. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic showed that healthcare services can adapt and offer self-management exercise programmes that can be delivered online [Citation8]. These programmes can be synchronous (e.g., videoconference with a clinician), asynchronous (e.g.,exercise digital images and videos), or hybrid (e.g., a combination of synchronous and asynchronous) [Citation9,Citation10]. Such online-delivered exercise programmes (ODEPs) offer an opportunity to address long waiting lists and assist those who cannot access care due to their location, work/caring responsibilities, or symptoms [Citation11]. Recent systematic reviews have found that delivering ODEPs for the management of chronic MSK conditions is effective and comparable to face-to-face care [Citation12,Citation13].

Despite these benefits and positive findings of effectiveness, an international survey of clinicians (n = 827) who used telehealth to deliver exercise to manage MSK conditions during COVID-19 found that only 42% agreed that telehealth was as effective as face-to-face care [Citation14]. Similarly, Barton et al. [Citation15] found that while 85% of people with MSK pain (n = 172) reported condition improvement as a result of telehealth, this intervention was perceived as inferior to in-person care. Previous research found that patient age and level of education, poor technological self-efficacy, resistance to changing clinical practice, and cost of resources contribute to the slow uptake of guideline-based telehealth services to manage chronic MSK conditions [Citation8,Citation10,Citation15]. Additionally, previous studies report slow uptake due to the misinformed perceptions of patients and clinicians of the effectiveness, accessibility, and flexibility of ODEPs [Citation11,Citation16]. Furthermore, patients frequently seek medical advice and treatments from clinicians, whose acceptance of telehealth can in turn influence their own acceptance [Citation16–18]. This suggests that the perceptions of patients and clinicians of ODEPs are interconnected, highlighting the need to determine the extent of shared perceptions to optimise uptake. Given the increasing prevalence of chronic MSK conditions, identifying patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of ODEPs may inform efforts to address evidence-to-practice gaps, ensure optimal use of resources, and facilitate patient access to high-quality care.

Previously, qualitative studies using semi-structured interviews [Citation17,Citation19], quantitative studies using cross-sectional surveys [Citation14,Citation20], mixed-method studies using qualitative and quantitative methodologies [Citation21,Citation22], and systematic reviews using qualitative [Citation10] or quantitative data [Citation23] have been conducted to explore patient and clinician perceptions of ODEPs for the management of chronic MSK conditions. The current systematic review aims to address important gaps in the existing literature. First, significant heterogeneity in previous reviews due to their focus on one or other aspects of patient and clinician perceptions of ODEPs for the management of chronic MSK conditions. For example, Fernandes et al. [Citation10] qualitatively summarised perceptions of patients with chronic MSK conditions of synchronous and asynchronous telehealth delivery of a pain management intervention. On the other hand, Amin et al. [Citation23] quantitatively summarised the satisfaction of patients’ and rehabilitation professionals’ of telerehabilitation for musculoskeletal disorders. Second, no synthesis of both qualitative and quantitative findings related to patient and clinician perceptions of ODEPs for the management of chronic MSK conditions exists. Such syntheses are known as mixed-methods reviews and are particularly relevant in public health [Citation24]. For example, health policy makers using systematic reviews to inform public health interventions may not only seek to answer, “What is effective and for whom?” but also, “Why is it effective and for whom?”. While the former question may be answered by quantitative evidence, the latter requires qualitative evidence [Citation25]. By integrating objective numerical data and subjective opinions data, a more in-depth understanding of a topic, compared to single method reviews, can be generated [Citation26]. Health policy makers and practitioners may find such an in-depth understanding useful for informing evidence-based decision-making and implementing appropriate public health interventions [Citation27].

Therefore, the current systematic review is timely as it builds on and streamlines the existing literature by including both qualitative and quantitative forms of evidence, addressing both patient and clinician data, and focusing on telehealth exercise services that are either entirely (e.g., videoconference-based) or partially (e.g.,web-based with telephone support calls) delivered via synchronous mediums. Our approach may maximise the ability of the findings to inform policy and practice due to the inclusion of diverse methodologies and perspectives [Citation28]. Thus, our aim is to systematically review, synthesise and integrate the common or differing perceptions of patients and clinicians to inform our understanding of the complexity and interplay of factors related to facilitating or hindering the uptake of ODEPs for chronic MSK conditions.

Methods

The protocol for this review has been previously registered on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42021273773) and published elsewhere [Citation29]. The reporting of this review was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [Citation30].

Eligibility criteria

As shown in , studies with (1) patients with diagnosed or self-reported chronic MSK conditions and/or clinicians, who deliver exercise treatments for chronic MSK conditions; (2) individual or group based ODEPs delivered via: delivery mode A: synchronously, participants exchange information simultaneously (e.g., videoconference call); delivery mode B: asynchronously, with at least one synchronous feature (e.g.,telephone support calls); or delivery mode C: no ODEP, where no exercise treatment was delivered but the authors investigated a participant’s past experiences and/or likelihood of participating in an ODEP (e.g., hypothetical experiences or attitudes); and (3) patients and/or clinicians’ perceptions influencing uptake of ODEPs for chronic MSK conditions (e.g., experiences, opinions, or beliefs) were included. Additionally, studies were considered for inclusion if they were reported in English and utilised either qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methodologies. No restrictions were applied to the intervention setting (i.e., could be a public or private setting) and publication date. Chronic MSK conditions were defined as conditions characterised with persistent pain (3 months) in the muscles, bones, joints, or related soft tissues [Citation31]. Synchronous features were defined as including some element of direct healthcare professional feedback.

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Search strategy and selection process

Eight electronic databases were searched from inception to April 2023: CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE, SportDiscus, and The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, Scopus, and Cochrane Library. Additionally, citation tracking and manual screening of the reference lists of included studies related to the research question were undertaken.

A Boolean search was conducted using an exhaustive list of combinations of key search terms relevant to the research aims in order to gather the current state of knowledge around the topic (). For example: ‘Osteoarthritis OR “Knee osteoarthritis” OR “Hip osteoarthritis” OR Musculoskeletal OR “Chronic pain” OR “Chronic knee pain” OR “Chronic hip pain” OR “Lower limb pain” OR “Lower extremity pain” OR “Persistent pain” OR “Back pain”’ AND ‘Exercis* OR Neuromuscular* OR Aerobic* OR Fitness* OR Resistance* OR Strength*’ AND ‘Telerehabilitation OR Telehealth OR Telemedicine OR Telemonitoring OR Online* OR Video* OR Internet* OR Web* OR Digital* OR Ehealth OR “E-health”’ AND ‘Adopt* OR Uptake OR Avoid* OR Barrier* OR Obstacle* OR Enable* OR Facilitat* OR Motivat* OR Challeng* OR Perception* OR Attitude* OR Belief* OR Experienc* OR View* OR Opinion* OR Accept* OR Satisfact* OR Feasib*’. Results were imported, organised, and stored using EndNote X9 (Version 9.3.3). Duplicates were removed and relevant titles and abstracts screened for eligibility by three independent reviewers (AB, CBW, CT). Full-text articles were screened for eligibility and methodological quality by six independent reviewers (AB, CBW, AE, COR, CT). Discrepancies were resolved by reviewer consensus (AB, CBW, AE, COR, CT).

Table 2. PICO Framework for Eligibility and Search Terms Used.

Data collection process

Two reviewers (AB, CT) independently extracted the data from the included studies into standardised spreadsheets (Microsoft Excel version 16.59, Microsoft Corporation, 2010), which were then merged. Any discrepancies were resolved by reviewer consensus and cross-checked for consistency by a third reviewer (AB, CBW, AE, COR, CT). Data were extracted on (1) perceptions of patients and/or clinicians that facilitate or hinder uptake, and (2) commonalities or differences between data related to patients and clinicians. Descriptive information for each study was extracted: author, year, country, aims, study design, data collection methods, population (i.e., sample, number, gender, type of chronic MSK condition, setting), intervention (i.e., type, delivery mode, description, duration), and outcomes.

Study risk of bias assessment

Quality appraisal was performed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklists [Citation32]. Studies were rated as high, medium, and low quality if they met ≥8, 5–7 and ≤4 criteria, respectively [Citation33]. Any discrepancies were resolved by reviewer consensus and cross-checked for consistency by a third reviewer (AB, CBW, AE, COR, CT).

Synthesis methods

This mixed-methods review involved: (1) qualitizing of quantitative data [Citation26]; (2) thematic analysis of qualitative data [Citation34]; and (3) synthesis combining data from stages (1) and (2) [Citation26]. This approach was adopted to facilitate a richer understanding of perceptions compared to examining qualitative or quantitative data independently. To optimise the applicability and richness of the findings, those perceptions that appeared in at least three studies were included in this review [Citation33]. To counteract any potential bias, reviewers’ personal beliefs and experiences were reflexively assessed using field notes to document decisions.

Stage 1: Qualitizing of quantitative data

Qualitizing involves translating quantitative data into textual descriptions (i.e., a narrative interpretation of the results) [Citation26]. This generates a descriptive summary of the quantitative data in a way that answers the review question independent of the qualitative data analysis and allows integration with qualitative data.

Stage 2: Thematic synthesis of qualitative data

Data from qualitative studies was copied verbatim and imported into QSR International’s NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software (QSR International, 2012). Firstly, free codes were developed through line-by-line coding of the data according to its meaning and content. Secondly, commonalities and differences in data were identified to develop new codes and organise the data into broader descriptive themes. Thirdly, higher order analytical themes were developed based on organisational groupings for facilitators and barriers to uptake. This was a highly repetitive process that involved re-examining and refining the themes continuously within the scope of the review. This cyclical process continued until final themes were agreed upon by reviewer consensus (AB, CT).

Stage 3: Combination of qualitized and qualitative data

To combine syntheses from stages (1) and (2), a table was constructed to juxtapose the qualitative and qualitized data to assess the extent to which the respective data confirmed, expanded, or refuted each other [Citation26].

Results

Study selection

As shown in , the database searches yielded 3056 records, of which 1940 records were identified as duplicates. After screening the title and abstract, 66 records underwent full-text review. Further 12 records were identified from citation tracking and manual screening of the reference lists, resulting in 21 included studies.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study identification and selection, adapted from PRISMA flow chart [Citation30].

![Figure 1. Flow diagram of study identification and selection, adapted from PRISMA flow chart [Citation30].](/cms/asset/1ae4002f-d74c-4ea2-8b87-1e2be419fde2/idre_a_2224085_f0001_c.jpg)

Study characteristics

Of the 21 included studies, twelve studies were quantitative [Citation35–46], seven qualitative [Citation47–53], and two mixed-methods [Citation54,Citation55]. Studies were published between 2005 and 2022 in Australia (n = 6), Netherlands (n = 5), United States of America (USA) (n = 3), Turkey (n = 2), Brazil (n = 1), China (n = 1), Sri Lanka (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), and United Kingdom (UK) (n = 1). Four studies were conducted with patients and clinicians [Citation35,Citation50,Citation53, Citation54], fifteen studies with patients only [Citation36,Citation38–42,Citation44–49,Citation51,Citation52,Citation55], and two studies with clinicians only [Citation37,Citation43]. There were a total of 1275 patients with chronic MSK conditions (range 8–330 per article) and 534 clinicians who treat patients with a chronic MSK condition (range 7–268 per article). Chronic MSK conditions included: Achilles tendinopathy (n = 1; [Citation53]), chronic hip or knee pain/OA (n = 14; [Citation35–38,Citation41–44, Citation46,Citation48–51,Citation55]), and chronic lower back pain (CLBP) (n = 6; [Citation39,Citation40,Citation45,Citation47,Citation52,Citation54]). Eighteen studies (85.7%) reported on individual-based ODEPs [Citation35–40,Citation43–54] and three studies (14.3%) on group-based ODEPs [Citation41,Citation42,Citation55]. These ODEPs were delivered either via delivery mode A (n = 7; [Citation39,Citation42,Citation46,Citation50,Citation51,Citation53,Citation55]), via delivery mode B (n = 8; [Citation35,Citation40,Citation41,Citation44,Citation45,Citation49,Citation52,Citation54]), or via delivery mode C (n = 6; [Citation36–38,Citation43,Citation47,Citation48]). Outcomes reported were measures of participant satisfaction (n = 6), usability (n = 6), acceptability (n = 5), and experiences (n = 11). Twelve studies were rated as high quality [35–Citation38,Citation43–45,Citation47,Citation49,Citation51–55] and seven studies as medium quality [Citation39–42,Citation46,Citation48,Citation50,Citation54]. Summary characteristics and the findings of the methodological quality assessment are presented in .

Table 3. Characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies.

Results of syntheses

Stage 1: Qualitizing of quantitative data

A narrative synthesis of the quantitative data was undertaken (). Overall, patients and clinicians were highly satisfied with telehealth and would recommend it to peers. ODEPs were found to be timesaving, accessible, useful, and flexible. Video-delivered care was preferred over telephone-delivered care, with participants expressing no concerns of privacy and confidentiality. Clinician contact mode (i.e., face-to-face/web-camera/combination), the presence of feedback and monitoring technology, and exercise location were found to be the most important telehealth intervention characteristics that influence uptake. ODEPs were found to be safe, easy to use, and convenient. Daily reminders and access to supporting materials reinforcing the importance of routine exercise were found to be effective in improving patient outcomes. Uptake was hindered by clinicians’ perceptions of the financial cost of setting up telehealth and patients’ perceptions of whether the condition could be adequately monitored via telehealth.

Stage 2: Thematic synthesis of qualitative data

Four themes emerged as the perceptions of patients and clinicians that influence the uptake of ODEPs for chronic MSK conditions: satisfaction, acceptability, usability, and effectiveness. Each theme could be both a facilitator and a barrier, depending on context, and was supported by data from patients, clinicians, or both. A summary of the groupings of facilitators and barriers to uptake that contributed to the development of third-order themes and illustrative quotes from primary studies supporting the themes can be seen in .

Table 4. Development of third-order themes, based on groupings for facilitators and barriers to uptake, with illustrative quotes from primary studies.

Satisfaction with ODEPs

Patients and clinicians were highly satisfied with the delivery of ODEPs and would recommend it to peers. Perceived benefits included being time-efficient, reduced travel times, the flexibility of appointment/exercise times and locations, easily accessible equipment, and an alternative to waiting for traditional care. Synchronous delivery allowed for satisfactory engagement and support from their clinicians, which encouraged goal maintenance and accountability. However, patients expressed concerns over the quality of feedback and monitoring technology, risk of misdiagnoses, lack of contact with fellow patients, and the possibility of alienation/social isolation. Some clinicians noted that flexibility could come at a cost, with appointments being rescheduled at the last minute.

Acceptability of ODEPs

Patients and clinicians found ODEPs to be acceptable. ODEPs suited conditions where the hands-on assessment was not essential and allowed them to focus on the most important and effective treatments/techniques. Furthermore, patients and clinicians felt the exercise location (i.e., home environment) encouraged a focus on the performance/technique of the exercises and integration into daily life. The opportunity to provide and receive regular feedback and monitoring was perceived as beneficial for therapeutic satisfaction and motivation. However, patients relied on their clinic and/or clinician, whose endorsement of ODEPs influenced patient acceptability.

Usability of ODEPs

Patients and clinicians found ODEPs to be easy to execute, structured, and designed to be user-friendly. Positive perceptions included it being an accessible resource for exercise or educational material to monitor self-progress and review correct techniques. However, few expressed concerns over the quality of feedback, difficulty understanding specific words/exercises, poor internet or audio connection, disruptions due to background noise, cost and time needed to set up an ODEP, and limited examination capacity (i.e., only having one camera angle).

Effectiveness of ODEPs

Patients and clinicians perceived ODEPs to be effective in promoting patient self-management, confidence, and routine treatment. Positive perceptions included reduction in pain, increased self-efficacy, ability to observe progress, and improvements in physical function.

Stage 3: Combination of qualitized and qualitative data

Data from qualitized findings confirmed and expanded 19/23 subthemes identified in the four themes. Integration was not possible for 4 subthemes as no qualitized data relating to these were identified. No qualitized data refuted qualitative data. presents this interpretive synthesis and the extent to which the respective data confirmed, expanded, or refuted each other.

Table 5. The extent to which qualitized data confirms, expands, or refutes the themes/sub-themes identified from the qualitative data.

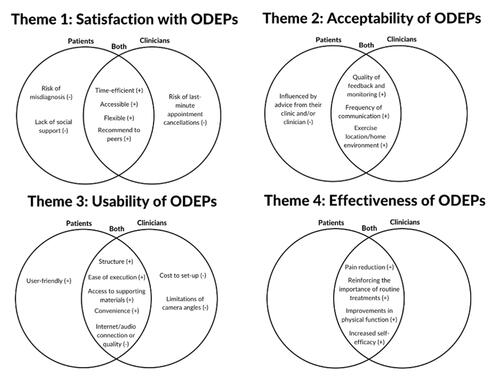

To demonstrate patient and clinician common or differing perceptions influencing the uptake of ODEPs, the integrated data were juxtaposed (). Findings indicated that 4/7 of perceptions related to satisfaction, 3/4 related to acceptability, 5/8 related to usability, and 4/4 related to the effectiveness of ODEPs were common between patients and clinicians.

Figure 2. Thematic schema illustrating the common or differing patient and clinician perceptions of ODEPs for chronic MSK conditions.

Note: ODEP: online-delivered exercise programme; MSK: musculoskeletal condition; +: facilitates uptake; -: hinders uptake.

Patients and clinicians were highly satisfied with ODEPs and would recommend the service to peers. Both found that ODEPs were time-efficient, accessible, and flexible, with these perceptions facilitating uptake. However, uptake was hindered by perceptions concerning the risk of misdiagnosis (patients only), lack of social support (patients only), and risk of last-minute appointment cancellations (clinicians only). ODEPs were also found to be highly acceptable, with patient and clinician perceptions that facilitated uptake including the quality of feedback and monitoring, the exercise location/home environment, and the frequency of communication between participants. For patients, advice from their clinic and/or clinician hindered uptake. Additionally, patients and clinicians found ODEPs to be usable, with perceptions that facilitated uptake including ease of execution, convenience, structure, access to supporting materials/resources, and user-friendly (patients only). Perceptions that hindered uptake included concerns over internet and audio connection/quality (both), limitations of camera angles (clinicians only) and the cost of setting up an ODEP (clinicians only). Furthermore, patients and clinicians found ODEPs to be effective, with perceptions on pain reduction, improvements in physical function, increased self-efficacy/confidence, and reinforcement of the importance of routine treatments/self-management strategies facilitating uptake.

Discussion

This mixed-methods systematic review synthesised evidence to identify the perceptions of patients and clinicians influencing the uptake of ODEPs for chronic MSK conditions. The findings suggest that patients’ and clinicians’ uptake of ODEPs is influenced by perceptions related to the following themes: satisfaction, acceptability, usability, and effectiveness. Specifically, 16/23 perceptions were found to facilitate uptake and 7/23 were found to hinder uptake. Furthermore, almost 70% of perceptions were common across patients and clinicians. The varied perceptions (30%) may be due to an individual’s role in telehealth services (i.e., patients receive vs. clinicians deliver).

Comparison with previous literature

In relation to satisfaction, the findings are similar to those reported previously. Kloek et al. [Citation56] and Winkelmann et al. [Citation57] found that telehealth services were perceived as timesaving. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported that telehealth visits for orthopaedic care were shorter than in-person visits (19 ± 8 min vs. 79 ± 85 min) [Citation58]. Similarly, Tenforde et al. [Citation59] found that patients saved more than 30 min of travel time on average due to telehealth visits. The accessibility and flexibility of telehealth allow for the inclusion of a diverse population (e.g., patients in rural areas) and previously, geographical location has been associated with access to care [Citation11]. Furthermore, Åkesson et al. [Citation60] found that healthcare professionals providing care for patients with OA reported challenges such as limited time to offer programme and high workload. Pearson et al. [Citation61] report on the importance of social support, the lack of which is perceived as negative by patients. While other studies report clinicians’ concerns of accurately diagnosing and treating patients via telehealth services [Citation14,Citation62], we found that patients were concerned about the risk of misdiagnosis. A possible explanation for this contrast could be that only six of the twenty-one (29%) included studies investigated the perceptions of clinicians.

In relation to acceptability, previous investigations also found that regular contact between patients and clinicians allowed for enhanced access to timely feedback and reassurance, and the opportunity to build rapport/trust [Citation63]. Additionally, the finding that exercise location, and the home environment, resulted in patients feeling more comfortable addressing their concerns and/or participating in exercise is similar to Kairy et al. [Citation64] reporting that patients felt less stressed and appreciated the sense of privacy. Furthermore, previous research reports “guidance by the physical therapist” and “preference of practioners for surgery” as important factors to participation [Citation16].

In relation to usability, the finding that access to supporting materials/resources would be useful and ensure an accurate understanding of the exercise technique is similar to previous studies reporting that instructional videos and reminders are elements that facilitate participation in telehealth services [Citation61]. Furthermore, treatment attributes that are important for uptake include ease of use, convenience, and structure [Citation57]. Additionally, previous research supports our finding that the cost of implementing telehealth services hinders uptake [Citation62].

In relation to effectiveness, the findings are similar to those reported previously on the importance of learning to self-manage and improving self-efficacy in patients with chronic MSK conditions [Citation60], and perceptions of symptom reduction and/or effective management [Citation62]. No perceptions that differed, and that hindered uptake were identified. A possible explanation for this could be that to optimise the applicability and richness of the findings, only perceptions that appeared in at least three of the twenty-one studies were included in this review [Citation33].

Implications

Misinformed perceptions (e.g., lack of content flexibility, de-personalization of care) may create barriers to the uptake of and referral to ODEPs [Citation10,Citation65]. Our findings indicate that despite differences in patients’ and clinicians’ roles in telehealth services (i.e., patients receive vs. clinicians deliver), most perceptions influencing uptake are shared, highlighting the significant role interconnected perceptions play in telehealth engagement. Future development and testing of telehealth services must consider addressing interconnected perceptions with targeted education for patients and clinicians. Acceptance of telehealth has been reported as a barrier to uptake [Citation14,Citation18] and such targeted education strategies may encourage patient and clinician acceptance. In addition, targeted education strategies may help facilitate guideline-based management of chronic MSK conditions by addressing computer or e-health literacy, previously reported as one of the main barriers to adoption of telehealth globally [Citation66].

Almost 70% (16/23) of the identified perceptions facilitated uptake, suggesting that patients and clinicians may acknowledge the advantages of telehealth services (e.g., improved accessibility). This suggests that the slow uptake of telehealth services may be significantly influenced by the 30% (7/23) of perceptions that hindered uptake. This is an important finding that researchers, community providers, and health policy makers may find useful when designing telehealth services and developing implementation strategies. Such telehealth services and implementation strategies may adopt a perception-centred approach that addresses key facilitators and challenges to uptake. Strategies addressing facilitators to uptake may include further supporting evidence on the benefits of telehealth (e.g., timesaving, flexible) or a greater number of supporting materials (e.g., exercise videos, educational websites). Strategies addressing challenges to uptake may include highlighting research on the diagnostic accuracy of telehealth, offering clear pathways to engage in online social support (e.g., additional online networking sessions for participants), or advocating for reimbursement of telehealth services (e.g., financial cost of necessary technological equipment is funded by professional bodies). The findings of this review highlight important areas for future studies including, how a perception-centred approach to implementation influences engagement with telehealth services, and how it may be helpful in selecting the most appropriate patients for ODEPs and improving patient outcomes for chronic MSK conditions.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this review is the first to examine the common or differing perceptions of patients and clinicians related to facilitating or hindering uptake of ODEPs for chronic MSK conditions. Uniquely, it synthesized the literature from patients’ and clinicians’ perspectives, whereas others have focused on one or other of these. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were included to maximise applicability of the findings. The studies included were of high to medium quality. Additionally, personal beliefs and experiences of the reviewers were reflexively assessed throughout to counteract any potential bias. Limitations include the exclusion of wider literature from other languages possibly resulting in publication bias, paediatric populations, and other types of telehealth services and health conditions. These findings may not be generalisable to (1) other self-management strategies as the studies focused on exercise, (2) other geographical locations, cultures, and healthcare settings, and (3) other healthcare professionals involved in delivery of care for MSK pain. The heterogeneity of included trials (e.g., context, methods, outcomes) prevented meta-analysis of quantitative results. Lastly, six of the twenty-one included studies were conducted in Australia raising questions of applicability to other countries, and three of the twenty-one included studies were undertaken by the same group of researchers raising issues of potential bias.

Conclusion

Globally, uptake of ODEPs for chronic MSK conditions has been slow, partly due to perceptions of patients and clinicians. This mixed methods review synthesised the common and differing perceptions of patients and clinicians that facilitate or hinder the uptake of ODEPs. Our findings suggest that patients’ and clinicians’ share almost 70% of perceptions related to satisfaction, acceptability, usability, and effectiveness that influence the uptake of ODEPs. The majority of perceptions facilitated uptake, highlighting that the development of telehealth services must strongly focus on and address perceptions that hinder uptake as these may be contributing significantly to patient and clinician uptake. Implementation strategies may be strengthened by targeted education encouraging acceptance of telehealth and e-health literacy for patients and clinicians and by adopting a perception-centred approach addressing key facilitators and challenges to uptake. This may positively influence uptake and ultimately, facilitate long-term sustainability guideline-based management of chronic MSK conditions.

Reporting guidelines

Open Science Framework: PRISMA-P Checklist for “Patient and clinician perspectives of online-delivered exercise programmes for chronic musculoskeletal conditions: protocol for a systematic review,” https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/75GVY (Bhardwaj, 2022). Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero “No rights reserved” data waiver (CC0 1.0 Universal).

Systematic review registration number

PROSPERO CRD42021273773.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

No data are associated with this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017; 390(10100):1211–1259.

- Hagen M, Madhavan T, Bell J. Combined analysis of 3 cross-sectional surveys of pain in 14 countries in Europe, the Americas, Australia, and Asia: impact on physical and emotional aspects and quality of life. Scand J Pain. 2020; 20(3):575–589. doi: 10.1515/sjpain-2020-0003.

- El-Tallawy SN, Nalamasu R, Salem GI, et al. Management of musculoskeletal pain: an update with emphasis on chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Ther. 2021; 10(1):181–209. doi: 10.1007/s40122-021-00235-2.

- Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, et al. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(2):79–86. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099878.

- Zadro J, O’Keeffe M, Maher C. Do physical therapists follow evidence-based guidelines when managing musculoskeletal conditions? Systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e032329. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032329.

- Cunningham J, Doyle F, Ryan JM, et al. Primary care-based models of care for osteoarthritis: a scoping review protocol. HRB Open Res. 2021;4:48. doi: 10.12688/hrbopenres.13260.2.

- Østerås N, Moseng T, van Bodegom-Vos L, et al. Implementing a structured model for osteoarthritis care in primary healthcare: a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. PLOS Med. 2019;16(10):e1002949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002949.

- Ezzat AM, Esculier J-F, Ferguson SL, et al. Canadian physiotherapists integrate virtual care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Physiotherapy Canada. 2022;:e20220092. doi: 10.3138/ptc-2022-0092.

- Fisk M, Rudel D, R R. Definitions of terms in telehealth. Informatica Medica Slovenica. 2011;16:28–46.

- Fernandes LG, Devan H, Fioratti I, et al. At my own pace, space, and place: a systematic review of qualitative studies of enablers and barriers to telehealth interventions for people with chronic pain. Pain. 2022; 163(2):e165–e181. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002364.

- Turolla A, Rossettini G, Viceconti A, et al. Musculoskeletal physical therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: is telerehabilitation the answer? Phys Ther. 2020;100(8):1260–1264. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa093.

- Agostini M, Moja L, Banzi R, et al. Telerehabilitation and recovery of motor function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2015; 21(4):202–213. doi: 10.1177/1357633X15572201.

- Cottrell MA, Galea OA, O’Leary SP, et al. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(5):625–638. doi: 10.1177/0269215516645148.

- Malliaras P, Merolli M, Williams CM, et al. It’s not hands-on therapy, so it’s very limited’: telehealth use and views among allied health clinicians during the coronavirus pandemic. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;52:102340. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102340.

- Barton CJ, Ezzat AM, Merolli M, et al. It’s second best": a mixed-methods evaluation of the experiences and attitudes of people with musculoskeletal pain towards physiotherapist delivered telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2022;58:102500–102500. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102500.

- Hofstede SN, Marang-van de Mheen PJ, Vliet Vlieland TP, et al. Barriers and facilitators associated with non-Surgical treatment use for osteoarthritis patients in orthopaedic practice. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147406.

- Cottrell MA, Hill AJ, O’Leary SP, et al. Service provider perceptions of telerehabilitation as an additional service delivery option within an Australian neurosurgical and orthopaedic physiotherapy screening clinic: a qualitative study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;32:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2017.07.008.

- Wade VA, Eliott JA, Hiller JE. Clinician acceptance is the key factor for sustainable telehealth services. Qual Health Res. 2014;24(5):682–694. doi: 10.1177/1049732314528809.

- Paskins Z, Bullock L, Manning F, et al. Acceptability of, and preferences for, remote consulting during COVID-19 among older patients with two common long-term musculoskeletal conditions: findings from three qualitative studies and recommendations for practice. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):312. doi: 10.1186/s12891-022-05273-1.

- Cottrell MA, Hill AJ, O’Leary SP, et al. Patients are willing to use telehealth for the multidisciplinary management of chronic musculoskeletal conditions: a cross-sectional survey. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(7):445–452. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17706605.

- Albahrouh SI, Buabbas AJ. Physiotherapists’ perceptions of and willingness to use telerehabilitation in Kuwait during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2021;21(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12911-021-01478-x.

- Bennell KL, Lawford BJ, Metcalf B, et al. Physiotherapists and patients report positive experiences overall with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study. J Physiother. 2021;67(3):201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2021.06.009.

- Amin J, Ahmad B, Amin S, et al. Rehabilitation professional and patient satisfaction with telerehabilitation of musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:7366063. doi: 10.1155/2022/7366063.

- Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):29–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440.

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, et al. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2.

- Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, et al. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2108–2118. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00169.

- Pearson A, White H, Bath-Hextall F, et al. A mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews. JBI Evid Implement. 2015;13(3):121–131.

- Shoesmith A, Hall A, Wolfenden L, et al. Barriers and facilitators influencing the sustainment of health behaviour interventions in schools and childcare services: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01134-y.

- Bhardwaj A, Barry Walsh C, Ezzat A, et al. Patient and clinician perspectives of online-delivered exercise programmes for chronic musculoskeletal conditions: protocol for a systematic review. [version 1; peer review: awaiting peer review. HRB Open Res. 2022;5:37. doi: 10.12688/hrbopenres.13551.1.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Treede R-D, Rief W, Barke A, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. PAIN. 2015;156(6):1003–1007. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Studies Checklist 2018. cited 2021 19/4/2021]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- Kanavaki AM, Rushton A, Efstathiou N, et al. Barriers and facilitators of physical activity in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(12):e017042. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017042.

- Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009; 9:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59.

- Bennell KL, Marshall CJ, Dobson F, et al. Does a Web-Based exercise programming system improve home exercise adherence for people with musculoskeletal conditions?: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98(10):850–858. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001204.

- Lawford BJ, Bennell KL, Hinman RS. Consumer perceptions of and willingness to use remotely delivered service models for exercise management of knee and hip osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res . 2017;69(5):667–676. doi: 10.1002/acr.23122.

- Lawford BJ, Bennell KL, Kasza J, et al. Physical therapists’ perceptions of telephone- and internet video-mediated service models for exercise management of people with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2018a;70(3):398–408. doi: 10.1002/acr.23260.

- Cranen K, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Vollenbroek-Hutten MMR, et al. Toward patient-centered telerehabilitation design: understanding chronic pain patients’ preferences for web-based exercise telerehabilitation using a discrete choice experiment . J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(1):e26. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5951.

- Jansen-Kosterink S, Huis In ‘t Veld R, Wever D, et al. Introducing remote physical rehabilitation for patients with chronic disorders by means of telemedicine. Health Technol. 2015; 5(2):83–90. doi: 10.1007/s12553-015-0111-5.

- Selter A, Tsangouri C, Ali SB, et al. An mHealth app for self-management of chronic lower back pain (limbr): pilot study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(9):94–94.

- Smittenaar P, Erhart-Hledik JC, Kinsella R, et al. Translating comprehensive conservative care for chronic knee pain into a digital care pathway: 12-week and 6-month outcomes for the hinge health program. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2017;4(1):e4. doi: 10.2196/rehab.7258.

- Wong YK, Hui E, Woo J. A community-based exercise programme for older persons with knee pain using telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2005;11(6):310–315. doi: 10.1258/1357633054893346.

- Dissanayaka T, Nakandala P, Sanjeewa C. Physiotherapists’ perceptions and barriers to use of telerehabilitation for exercise management of people with knee osteoarthritis in Sri Lanka. Disability and Rehabilitation: assistive Technology. 2022;12:1–10. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2022.2122606.

- Fioratti I, Miyamoto GC, Fandim VJ, et al. Feasibility, usability, and implementation context of an internet-based pain education and exercise program for chronic musculoskeletal pain: pilot trial of the ReabilitaDOR program JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(8):e35743. doi: 10.2196/35743.

- Özden F, Sarı Z, Karaman ÖN, et al. The effect of video exercise-based telerehabilitation on clinical outcomes, expectation, satisfaction, and motivation in patients with chronic low back pain. Ir J Med Sci. 2022;191(3):1229–1239. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02727-8.

- Tore NG, Oskay D, Haznedaroglu S. The quality of physiotherapy and rehabilitation program and the effect of telerehabilitation on patients with knee osteoarthritis . Clin Rheumatol. 2023;42(3):903–915. doi: 10.1007/s10067-022-06417-3.

- Arensman R, Kloek C, Pisters M, et al. Patient perspectives on using a smartphone app to support home-based exercise during physical therapy treatment: qualitative study. JMIR Hum Factors. 2022;9(3):e35316. doi: 10.2196/35316.

- Cranen K, Drossaert CHC, Brinkman ES, et al. An exploration of chronic pain patients’ perceptions of home telerehabilitation services. Health Expect. 2012;15(4):339–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00668.x.

- Cronström A, Dahlberg LE, Nero H, et al. I would never have done it if it hadn’t been digital’: a qualitative study on patients’ experiences of a digital management programme for hip and knee osteoarthritis in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e028388. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028388.

- Hinman RS, Nelligan RK, Bennell KL, et al. Sounds a bit crazy, but it was almost more personal: a qualitative study of patient and clinician experiences of physical therapist-prescribed exercise for knee osteoarthritis via skype. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(12):1834–1844. doi: 10.1002/acr.23218.

- Lawford BJ, Delany C, Bennell KL, et al. “I was really sceptical…but it worked really well”: a qualitative study of patient perceptions of telephone-delivered exercise therapy by physiotherapists for people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018b;26(6):741–750. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2018.02.909.

- Geraghty AWA, Roberts LC, Stanford R, et al. Exploring patients’ experiences of internet-based self-management support for low back pain in primary care. Pain Med. 2020; 21(9):1806–1817. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz312.

- Hasani F, Malliaras P, Haines T, et al. Telehealth sounds a bit challenging, but it has potential: participant and physiotherapist experiences of gym-based exercise intervention for achilles tendinopathy monitored via telehealth. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):138. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03907-w.

- van Tilburg M, Kloek C, Staal JB, et al. Feasibility of a stratified blended physiotherapy intervention for patients with non-specific low back pain: a mixed methods study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022;38(2):286–298. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2020.1756015.

- Patel KV, Hoffman EV, Phelan EA, et al. Remotely delivered exercise to rural older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a pilot study. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2022;4(8):735–744. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11452.

- Kloek CJJ, Bossen D, de Vries HJ, et al. Physiotherapists’ experiences with a blended osteoarthritis intervention: a mixed methods study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;36(5):572–579. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1489926.

- Winkelmann ZK, Eberman LE, Games KE. Telemedicine experiences of athletic trainers and orthopaedic physicians for patients with musculoskeletal conditions. J Athl Train. 2020; 55(8):768–779. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-388-19.

- Chaudhry H, Nadeem S, Mundi R. How satisfied are patients and surgeons with telemedicine in orthopaedic care during the COVID-19 pandemic? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479(1):47–56. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001494.

- Tenforde AS, Iaccarino MA, Borgstrom H, et al. Telemedicine during COVID-19 for outpatient sports and musculoskeletal medicine physicians. Pm R. 2020; 12(9):926–932. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12422.

- Åkesson KS, Sundén A, Hansson EE, et al. Experiences of osteoarthritis guidelines in primary health care – an interview study. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01611-9.

- Pearson J, Walsh N, Carter D, et al. Developing a web-based version of an exercise-based rehabilitation program for people with chronic knee and hip pain: a mixed methods study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(2):e67. doi: 10.2196/resprot.5446.

- Buabbas AJ, Albahrouh SE, Alrowayeh HN, et al. Telerehabilitation during the COVID-19 pandemic: patients and physical therapists’ experiences. Med Princ Pract. 2022;31(2):156–164. doi: 10.1159/000523775.

- Matthias MS, Evans E, Porter B, et al. Patients’ experiences with telecare for chronic pain and mood symptoms: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2020;21(10):2137–2145. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz345.

- Kairy D, Tousignant M, Leclerc N, et al. The patient’s perspective of in-home telerehabilitation physiotherapy services following total knee arthroplasty. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(9):3998–4011. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10093998.

- Green T, Hartley N, Gillespie N. Service provider’s experiences of service separation: the case of telehealth. J Serv Res. 2016;19(4):477–494. doi: 10.1177/1094670516666674.

- Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, et al. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018; 24(1):4–12. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16674087.