Abstract

Purpose

Person-centred care (PCC) is an essential component of high-quality healthcare across professions and care settings. While research is emerging in subacute nutrition services more broadly, there is limited literature exploring the person-centredness of nutrition care in rehabilitation. This study aimed to explore person-centred nutrition care (PCNC) in rehabilitation units, as described and actioned by patients, support persons and staff. Key factors influencing PCNC were also explored.

Materials and methods

An ethnographic study was undertaken across three rehabilitation units. Fifty-eight hours of field work were completed with 165 unique participants to explore PCNC. Field work consisted of observations and interviews with patients, support persons and staff. Data were analysed through the approach of reflexive thematic analysis, informed by PCC theory.

Results

Themes generated were: (1) tensions between patient and staff goals; (2) disconnected moments of PCNC; (3) the necessity of interprofessional communication for PCNC; and (4) the opportunity for PCNC to enable the achievement of rehabilitation goals.

Conclusions

PCNC was deemed important to different stakeholders but was at times hindered by a focus on profession-specific objectives. Opportunities exist to enhance interprofessional practice to support PCNC in rehabilitation. Future research should consider the system-level factors influencing PCNC in rehabilitation settings.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Understanding what matters to patients in rehabilitation was reported as essential in person-centred nutrition care (PCNC), however varying degrees of this were observed in practice, with tensions exposed between the priorities of patients and staff.

Collaborative goal setting is needed to enact PCNC, placing the patient at the centre of the process, rather than focusing on pre-determined, profession-specific agendas. However, reorientating this process must coincide with consideration of influencing systems, service priorities and cultures.

Nutrition and mealtime-related goals of patients should be communicated not only within clinical teams, but also with dietetic support staff to better inform interprofessional practice and PCNC.

Opportunities exist to better connect nutrition and dietetic services with the broader goals and objectives of rehabilitation.

Introduction

Person-centred care (PCC)—a more holistic extension of patient-centred care [Citation1]—is touted as an essential component of high-quality care in both nutrition/dietetic [Citation2] and rehabilitation [Citation3–5] services. While there continues to be a lack of consensus regarding the definition of PCC [Citation6, Citation7], it has been suggested that “person-centredness in healthcare is a philosophical approach in which decision-making and caregiving is explicitly undertaken with, and not for the person, with their needs, values and preferences positioned as centred to the care they receive” (p.1) [Citation8]. Key features identified as exemplifying PCC in rehabilitation at an individual level include care that is: tailored to and respectful of the person beyond individualising interventions for the patient; adaptive to the situation; empowering, enabling, and collaborative; fosters a supportive relationship; and focused on strengths, hope and meaning [Citation4]. The core outcome of PCC is frankly summarised by McCormack and McCance as “a good care experience” (p.19) [Citation9]. There are also various contextual factors within the care environment that influence PCC, including the physical environment, staff skill mix, organisational systems, sharing of power, potential for innovation and risk taking, and staff relationships [Citation10, Citation11].

Demand for rehabilitation is increasing worldwide due to our global ageing population and increasing burden of chronic disease [Citation12, Citation13]. The provision of PCC is advocated in providing high-quality rehabilitation [Citation4]. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of rehabilitation care being personalised and meaningful to patients, and the need for team- and system-wide commitment to person-centred rehabilitation services [Citation3, Citation10, Citation14, Citation15]. Team collaboration is also widely acknowledged as a key part of effective rehabilitation [Citation16, Citation17]. There is a growing recognition of the need to include family, carers, and friends of patients (referred to herein as support persons) alongside staff and patients in the rehabilitation team to provide PCC [Citation16]. Support persons are thought to be crucial allies in healthcare safety and quality, due to their influence on patients’ health and wellbeing [Citation18].

Dietetics is one discipline involved in the interprofessional rehabilitation team, with a well-established role in malnutrition prevention and treatment [Citation19–21] and, to a lesser extent, ongoing nutritional issues following acute illness, as well as chronic disease and weight management [Citation22, Citation23]. Mealtimes have become a focal point in multifaceted approaches to target malnutrition in rehabilitation and other long term care facilities [Citation24–26]. Mealtime interventions known to positively influence the nutritional, clinical and functional outcomes of patients include communal dining models and dining room enhancements [Citation27]. Person-centred approaches to mealtimes have been shown to improve nutritional intake, compared to traditional task-focused mealtimes [Citation25, Citation28]. Furthermore, we have identified interprofessional practice as influencing the delivery of both mealtime and nutrition care [Citation29]; also acknowledged in other research [Citation30–33]. This highlights the need for nutrition research, especially person-centred nutrition care (PCNC) research, to focus not only on the work of nutritional professionals, but also on the influence of other healthcare team members and the system that they work within.

There is an increasing focus in health services on delivering value-based healthcare, which emphasises identifying and considering what matters most to patients, thus supporting PCC [Citation34]. Literature has emerged exploring patient-centred dietetic care in the primary care setting, suggesting that patients want to receive care that is individualised, be involved in their care, and have caring relationships with their dietitian [Citation35]. However, the modes and focus of nutrition care are known to vary across different healthcare settings, with a recent scoping review highlighting the limited evidence on how person-centred dietetic care is conceptualised and provided, and the lack of patient-reported PCNC outcomes, specifically in rehabilitation [Citation6]. Consequently, it is essential that current nutrition and mealtime practices in rehabilitation are studied through a PCC lens. This will help to progress understanding of what patients, staff and support persons value, and to identify areas for improvement in PCNC delivery and outcomes in rehabilitation settings.

Aim

We aimed to explore PCNC in rehabilitation units as described and actioned by patients, support persons and staff. Additionally, we aimed to explore the key factors that influence the delivery of PCNC in rehabilitation.

Materials and methods

Study design

Our ethnographic study explored PCNC in rehabilitation through an interpretivist research paradigm. In coherence with this paradigm, we embraced subjectivity, recognising participants’ diverse perspectives and experiences, reflecting on and valuing the central role of the first author HO in guiding exploration through data collection and analysis [Citation36, Citation37] and seeking to make sense of how participants understand and enact PCNC in rehabilitation. The use of ethnography supported the collection of data within its “natural” setting, whereby HO participated in the social world studied [Citation38]. Ethnography differs from other qualitative research approaches in that it focuses on the relationship between day-to-day interactions and wider aspects of culture [Citation39, Citation40]. In our study, data were collected through field work including observations and interviews (opportunistic and scheduled) with staff, patients and support persons. This supported exploring PCNC through both participants’ descriptions and actions.

Setting

Three subacute rehabilitation units from two sites within one metropolitan public health service in Australia were included in our study. Two units were co-located at one site. The average age of patients admitted to the co-located units in 2021 was 61.3 years, and 76.2 years at the other unit (unpublished report). The three most prevalent impairment groups across sites were stroke, reconditioning, and orthopaedic fracture. Similar groups of staff were employed across the units, including rehabilitation physicians, nurses, allied health staff, allied health assistants, food service officers (FSOs) and patient support officers (PSOs). Across all three units, FSOs completed operational tasks, such as food preparation/delivery and/or meal ordering. Nutrition assistants or dietetic allied health assistants (referred to herein as NAs), completed some operational tasks and/or clinical tasks involving nutrition screening, assessment or intervention, as delegated by a dietitian, or provided mealtime care. The three units shared a purpose in that they provided subacute services to support the rehabilitation of patients by enhancing their functional capacity, ability, and independence post-illness or injury (e.g., after a stroke or fall with consequent fracture). However, the food service systems and dietetics models of care across the two sites differed. Thus, sampling two sites supported our consideration of how diverse cultures, systems or models of care may influence PCNC.

Participants

Participants were identified by HO through a combination of purposive, convenience and snowball sampling, and included any patients, support persons, and staff from diverse professions who were on the study units. Given the interprofessional nature of care in rehabilitation, we decided that any staff member involved in the planning, delivery, adaptation, or evaluation of nutrition or mealtime care was eligible, including medical, nursing, allied health (dietetics, speech pathology, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, social work and psychology), food services, support services (e.g., NAs and PSOs) and administration staff. Eligible patients and support persons, and key staff were identified in conjunction with the interprofessional team, through targeted recruitment discussions and advice from staff who were aware of the study (e.g., existing participants).

Data collection

Fifty-eight hours of field work, involving 165 unique participants (n = 46 patients, n = 6 support persons and n = 113 staff) occurred from September 2021–April 2022, with brief pauses in data collection during the local COVID-19 pandemic peaks. All data were collected by HO, a doctoral candidate and clinical dietitian, who had previously worked across both study sites and was working at one of these sites during the study. To enhance transparency, HO reminded potential participants when she was on the unit for the research study, as opposed to providing clinical care as a dietitian. She also clearly displayed identification badges to outwardly distinguish her two roles. HO collected all data, which supported her familiarly with the dataset. Field work continued until HO, in consultation with the research team, felt that sufficient data were collected to answer the research questions.

Thirty-six observation episodes of 125 unique participants (n = 27 patients, n = 3 support persons and n = 95 staff) were completed over 28 non-consecutive hours. Observations focused on a range of different events, interactions and behaviours which occurred as part of day-to-day clinical nutrition and mealtime care, such as clinical care related to nutrition provided by dietitians or other health professionals, main and mid meal service, and team meetings (e.g., case conference). Observations were completed across different days and times of the week to capture a diverse sample of participants and different events. HO considered nine observational dimensions to guide the recording and reconstruction of field notes (see ) [Citation41, Citation42]. Handwritten field notes were reconstructed into a Microsoft® Word document as soon as possible following the observation episode to enhance accuracy [Citation43, Citation44]. This resulted in 100 pages (34,208 words) of typed field notes including reflexive notes, which recounted HO’s interpretation of the data collection process and data gathered. In some instances, illustrations and maps were also drawn of environments and activities.

Table 1. The nine observational dimensions as described by spradley [Citation40, Citation41] with examples showing application to this ethnographic study on person-centred nutrition care in rehabilitation.

Additionally, 91 interviews (59 scheduled and 32 opportunistic) were undertaken by HO over 30 h, with 77 unique participants (n = 23 patients, n = 5 support persons and n = 49 staff). Most interviews were completed one-on-one (HO and the participant), however some occurred with multiple participants, such as with both patients in a two-bed bay or with a patient and their support person/s. Ten participants (most commonly NAs, FSOs and dietitians) were interviewed multiple times (2–4 interviews each) which offered the opportunity for reflexive elaboration. Opportunistic interviews were often ad-hoc, taking place face-to-face with participants to explore observed events. Scheduled interviews were offered to some participants (face-to-face or over Microsoft® Teams), such as nursing and allied health staff, to allow dedicated time for participants to discuss PCNC more deeply and elaborate on related systems and workflows.

All interviews were conversational in nature despite having an interview guide (see ). HO tailored questions to participants, allowing for further elaboration on ideas as they arose or events observed [Citation45]. Interviews were audio recorded with consent and transcribed using Microsoft® Office 365 transcription. The transcripts were verified by HO as soon as possible following the interaction by listening back to the recorded audio and making edits.

Table 2. Example interview questions for the ethnographic study on person-centred nutrition care in rehabilitation.

Data analysis approach

We began data analysis during field work using reflexive thematic analysis (referred to herein as “reflexive TA”) [Citation46, Citation47]. Reflexive TA supported an iterative approach to analysis, informed by PCC theory. The six phases of reflexive TA familiarisation, coding, initial theme generation, theme review, theme refinement, and report writing were embraced in a fluid approach to analysis, whereby the phases were not always followed in a step-wise fashion [Citation47]. Both inductive and deductive orientations to the data were considered. Data were also coded for context and profession to explore differences between sites and participant groups. Data analysis occurred by hand (e.g., drawing mind maps) and with the support of software such as NVivo (QSR International Version 12), and Microsoft® Word. Reflexive notes taken during field work supported the consideration of how HO’s own perspectives or experiences influenced data collection and analysis, with regular discussions with the research team enriching this process.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the hospital and university ethics committees (HREC/2021/QRBW/75477; 2021/HE001190). Verbal or written consent was obtained for participation in opportunistic or scheduled interviews, respectively. An opt-out consent approach was approved for the observations; that is, patients, support persons and staff on the units were notified of the study and could contact HO if they did not want to be included. Flyers summarising the purpose of this research and the HO’s contact details were displayed around the study units and shared with staff by managers through internal channels. As well, flyers were offered to patients and support persons by dietetics support staff prior to and during the study. Each participant included in the study was given a unique identifier to ensure anonymity. Participants captured in field notes who were not the focus of a discrete observation episode were not ascribed a unique identifier.

Rigor

Various strategies were employed to support rigor in our study. Internal coherence was ensured by aligning the philosophical positioning, methodology and methods [Citation48]. The depth and breadth of data collected and in turn the credibility of findings were supported by different data collection methods, as well as the prolonged engagement of HO in the field. To promote reflexivity and the consideration of alternative viewpoints, sample transcripts were independently coded by TG, an experienced qualitative researcher, and then discussed with HO. Discussion with all members of the research team supported coding and theme generation. This further enhanced reflexivity and interpretive depth in our study, as all team members offered unique and critical viewpoints [Citation49] to enrich HO’s perspective. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research were considered to support thorough and transparent reporting of this study [Citation50], alongside a tool for evaluating manuscripts that report thematic analyses [Citation51].

Results

Four themes were generated relating to the description and action of PCNC in subacute rehabilitation units. These were: (1) tensions between patient and staff goals; (2) disconnected moments of PCNC; (3) the necessity of interprofessional communication for PCNC; and (4) the opportunity for PCNC to enable the achievement of rehabilitation goals.

Theme 1: tensions between patient and staff goals

Whilst staff across sites stated that an important step in PCNC was understanding what mattered to patients, this was often at tension with professional agendas. Dietitians described how they identified and applied patient preferences, needs, and goals to inform nutrition care plans. Whilst most dietitians expressed confidence in identifying nutrition goals with patients and consciously tried to let go of preconceived plans to better include patients in their care planning, this was not always observed. Consequently, individual patient goals—nutrition-related or otherwise—were rarely seen to lead or be discussed in patient-dietitian consultations. Instead, dietitians’ goals appeared to be formed prior to patient interaction and largely focused on addressing and/or explaining the consequences of ongoing poor nutritional intake. This may have been exacerbated by the primary focus of nutrition services in rehabilitation settings being malnutrition prevention and treatment, as per evidence-based guidelines. Therefore, while dietitians felt they were providing PCNC, this was not always reflected in their practice, leading to an imbalance in decision-making power. This, too, was highlighted by some dietitians and managers who lamented that staff struggled to let go of pre-determined profession-specific objectives to inform patient care:

…I think we [health professionals] assume we know what patients want, but I don’t think we actually ask them. And then when we do ask them, I think we just do whatever we want to do anyway. … We kind of fit that into what we’re already doing, instead of truly listening and then creating interventions that are tailored to those goals. – Allied Health Manager 1

I find that hard [setting nutrition goals]. I’ve been trying to do it. I’m not always the best at it and a lot of the time patients just say, ‘I don’t have any goals’. But I have some goals, especially if they’re malnourished. So usually, I ask the patient if there’s anything they wanted to work on from a nutrition point of view while they’re here. Sometimes they might…. But if not, then I just make up my goal, like aiming to meet energy and protein needs and slow down weight loss… – Dietitian 2

The insights of patients corroborated these findings. Whilst patients acknowledged the value of nutrition in supporting their rehabilitation outcomes, and they recalled being asked about their food and beverage preferences during their stay, not all had the opportunity to discuss their nutrition goals with staff. Further, in some instances, patients’ goals were reported to be dismissed by medical or dietetic staff, as they were at odds with typical health professional-led goals:

…I did say to somebody, ‘Well I hope I lose some weight while I’m here’ and they just said, ‘Oh we don’t want you to lose weight, you’ll just lose muscles’, but I’m like, yeah, no I do want to lose weight. – Patient 21

Furthermore, what is considered PCNC was noted to vary from person to person, adding another layer of complexity to facilitating the balance of power. For example, some patients wanted to lead their nutrition and mealtime care decisions, with or without dietetics input, while others simply wanted to be kept informed about what they were working towards each day/therapy session, and how this was helping them achieve their goal, such as getting home. Other patients held the mentality that the professionals know best and thus, they were happy to do as the team advised when it came to their nutrition care. This emphasised the essentiality of patient-staff collaboration and negotiation in PCNC to identify patient goals, as well as the level of power-sharing and decision-making involvement desired by patients.

Theme 2: disconnected moments of PCNC

Collaboration between patients, support persons and staff was frequently reported by participants as essential in delivering PCNC. However, opportunities for collaboration lacked connection at times, with different team members responsible for different aspects of nutrition care.

Speech pathologists and occupational therapists reported having greatest involvement in identifying strategies to support eating (e.g., positioning or aids) and meal preparation (e.g., practise for home), due to the tasks embedded within their role and their expertise. This occurred with or without dietetic consultation. Additionally, occupational therapists reported identifying and considering food-related goals in collaboration with patients to facilitate involvement in occupational therapy-led meal preparation groups. Sporadic interprofessional collaboration with speech pathologists was reported through these groups, but dietitians were not observed to be involved as these groups were a low clinical priority within the existing models of care and staffing allocations. This was, however, acknowledged by one manager as a future opportunity for interprofessional practice.

Dietitians deemed it their responsibility to identify the nutrition goals of patients. Although NAs completed tasks delegated by dietitians, they were not reported or seen to identify or review nutrition-related goals with patients, unless explicitly asked to do this, or they proactively sourced this information from the documentation of other staff in medical chart. Some dietitians and NAs suggested that NAs may not engage with this aspect of PCNC because it is not deemed as part of their role, with dietitians also proposing that this may be a consequence of a protocolised model of care:

… I think a limitation [of the protocolised care model] would be that it doesn’t always include patient goals… they [the patient] might be screened as a 2 [Malnutrition Screening Tool score of 2, at risk of malnutrition], but the patient wants to stay weight stable, yet [the NAs] are still implementing high protein, high energy, frequent meals. Following that flowchart without taking a step back and perhaps considering what the patient’s goals are. – Dietitian 1

…from a dietetic perspective, it [PCNC] would be asking them as well, clarifying if they need assistance, preferences. If you’re going to do things like supplements, what times do they want them? Often [with] our supplements, we’ll go, oh, morning tea and afternoon tea. Usually they’re not there [in their room]. They don’t want them then anyway. So, I found often patients would want things at 7:00 o’clock at night. So, trying to work in around their day. – Dietitian 3

Many [patients] are dependent on assistance for transfers and mobility. The nurses don’t ask [where they want to eat their meal] because that might mean, I now need to find a second nurse to transfer you onto your wheelchair so we can get you out there [to the dining room]. … I don’t have any staff to get you up, so I’m just gonna leave you [in your room] for now. – Occupational Therapist 5

A further disconnect was noted in case conferences where patient-identified goals (nutrition-related or otherwise) were raised in only a few instances, and even when these were reported, they did not consistently guide team conversations. Instead these conversations were largely focused on functional ability, medical stability, and discharge barriers or plans. Additionally, nutrition was rarely discussed in this forum unless it was a barrier to discharge, such as considerations with enteral nutrition. This suggests that nutrition care was perhaps disconnected from the goals of rehabilitation aligned with other therapies; alternatively it may suggest that nutrition was not a key focus of care planning until it became a service-related a problem.

Theme 3: the necessity of interprofessional communication for PCNC

The interprofessional communication and handover of information regarding nutrition and mealtime care influenced the ability of dietitians, speech pathologists, support staff and nurses to enact PCNC. Interprofessional communication was reported to enable staff awareness and use of this information when providing nutrition and mealtime care. For example, conversations between PSOs and nurses about where patients wanted to eat their lunch (i.e., in their room or the dining room). Interprofessional communication was also noted to be particularly important for patients and support persons who were reluctant to approach and discuss their needs with busy staff. Examples of this cited by participants included timely communication (i.e., soon after admission) from NAs and nursing staff of details such as how to order meals and access the dining room.

While interprofessional handover from occupational therapists and speech pathologists to NAs routinely occurred with respect to patients’ needs for modified cutlery or diets, further communication about patients’ mealtime goals was limited. However, NAs explained how knowing more about patients’ nutrition-related goals would help them to support patients in achieving these goals:

…there could be more goals around food, like patient goals and how we can support their goals. Like it might be a goal of theirs to independently eat their food. When people go and offer assistance continually, they’re not going to be independent. So, if we could have that information about what patients want out of their mealtime, that would help as well. – Nutrition Assistant 3

Some dietitians and NAs also highlighted that patients’ goals and needs around nutrition and mealtimes may change throughout rehabilitation, yet this was not always captured or communicated across the team. This seemed to reflect a lack of established supporting processes regarding the update or sharing of this information which thus hinder the provision of care aligned with the patient’s needs. Consequently, staff felt that creating and embedding processes which support the regular review, update and interprofessional communication of these goals, and any changes, was needed. This would help to ensure that patients receive care which is tailored to their changing needs, workloads are appropriately distributed, and patients’ autonomy is not compromised.

Staff used different methods of communication, depending on the information to be shared and with whom. However, all units employed hybrid approaches with combinations of verbal (face-to-face or telephone) and written (digital handover systems, printed lists, tray tickets or whiteboard) methods. Dietetic and nursing staff at one site suggested that digital handover systems and processes could be better harnessed with state-wide consistency in terminology and assessments to support comprehensive understanding of each patient’s meal and mealtime preferences or needs across the team, thereby enhancing person-centredness of mealtime care:

… If you had a drop-down box [that] says needs supervision or needs assistance, needs set up with meals… independent with meals or uses special spoon or feeders … I think the whole organisation will benefit from that. … MST was a state-wide change… and now if there’s a tool that you do [a] nutritional assessment [in] rather than just MST… that would be something that you know nurses would benefit [from]… the entire MDT [multidisciplinary team] will benefit from. – Nurse 21

Theme 4: the opportunity for PCNC to enable the achievement of rehabilitation goals

Empowering the physical recovery, adaptation to a new reality, as well as patient autonomy (where possible) were frequently cited as important within the PCNC process. However, even when the goal of rehabilitation was physical recovery, there was often a missed opportunity to emphasise the positive impact of nutrition in this process. For example, by expanding profession-specific care plans or activities to explicitly highlight the relationship between patients’ goals (e.g., regaining strength to support recovery) and the sharing of profession-specific expertise to support goal attainment (e.g., sufficient nutritional intake to enhance energy and strength). This was rarely emphasised in patient-dietitian interactions despite having numerous opportunities to do so, nor was it raised in exchanges between patients and other staff, with staff observed to be primarily focused on their own profession-specific contribution to patient care.

Occupational therapy groups focused on patients adapting and practising meal preparation for home, and these groups were suggested and seen to be an opportunity for PCNC. Interestingly, there was no effort observed to empower nutrition knowledge in this setting such as discussing the nutrient content of food prepared in relation to patients’ nutrition goals. Nevertheless, patients considered these groups an extension of the nutrition care system with food and meals a key focus, suggesting that dietetics should be more involved in this aspect of rehabilitation:

If you are working with the OT [occupational therapist] and doing the cooking lesson … I think there would be good value in a nutritionist who sits on one of the classes. … I think that might be good for people who don’t know how to cook or adapting their way of life. – Patient 24

Patient 13 starts walking into the dining room. Another patient who’s already seated, Patient 11, calls out to him excitedly, “Oh [patient’s name]!” Patient 13 then sits down directly across from Patient 11 at the table. Speech Pathologist 4 arrives and stands next to Patient 13 aligned with the middle of the table. The speech pathologist appears to be encouraging communication between the two patients. She encourages Patient 11 to ask Patient 13 how are you? Which he achieves! They all cheer and continue to chat and laugh.

[Speaking about why they encourage their loved one to eat in the dining room:] So he can get used to eating at the table again at home … eating in bed just wasn’t working with his left hand, and we thought let’s go back to a table. – Support Person 2

Discussion

Our ethnographic study aimed to extend previous research by moving from broad examinations of rehabilitation nutrition and mealtime care, to explore the person-centredness of nutrition care practice as a fundamental element of rehabilitation. We found that providing PCNC was important across stakeholders, with individualising care plans and processes according to what matters most to patients deemed essential. However, varying degrees of this were observed in practice, with tensions exposed between patients’ goals and profession-specific objectives. Similarly, patients and support persons emphasised the value of rehabilitation nutrition and mealtime care being personalised and meaningful to the individual and their goals but noted that this was not always achieved. Our findings highlight person-centred moments [Citation10] in nutrition and mealtime care, but suggest that more work needs to be done to create a culture of PCNC across rehabilitation units.

In relation to our findings that patients’ nutrition goals were sometimes dismissed in favour of profession-specific objectives, this may be due to the malnutrition-focused priorities of dietetic services in inpatient settings [Citation19, Citation52]. It may also reflect the confidence of staff in using patient goals to practically guide care and provide PCC (as raised by managers in our study), the tension between task-focused or service-centric systems and PCC [Citation15, Citation53], the power imbalance between dietitians and patients when identifying nutrition care goals [Citation54], the constraints of time [Citation6, Citation15, Citation55], or other environmental factors such as staffing, competing demands and organisational culture [Citation9]. Promisingly, patients’ preferences and needs were routinely considered by dietitians, speech pathologists, nurses and support staff to individualise mealtime and nutrition care plans. This demonstrates how person-centred strategies are being used to some extent. However, similar to other research, opportunities exist to better integrate patients’ nutrition goals into the nutrition care process [Citation56], and for these goals to be shared with support staff to better support PCNC, particularly at mealtimes. This may be enhanced by reimagining healthcare policies, physical environments, care processes, and service quality indicators to create healthcare services that better support cultures of PCC [Citation15].

A further missed opportunity for PCNC was the lack of discussion regarding how nutrition can help to achieve broader rehabilitation goals and objectives, and other health outcomes, similar to existing research [Citation57]. This points towards the need for staff education and training on the contribution that nutrition can make, which may be conceptualised as shared decision-making [Citation58]. A recent systematic review found that clinicians recognised the importance of effective communication with patients but lacked the knowledge and skills to engage in shared decision-making [Citation58]. While prior research has highlighted that dietitians may benefit from further targeted training to enhance aspects of PCC [Citation59, Citation60], our findings, like others, suggest this should coincide with consideration of local processes and environments [Citation15, Citation61] with attention to the alignment of systems, care processes and staff actions [Citation62].

We found that patients, support persons, and staff conceptualised PCNC in rehabilitation in four main ways, with similarities to previous PCC models [Citation4, Citation63]. These were: tailoring nutrition and mealtime care and processes with patients; empowering physical recovery through optimising nutrition; enabling adaptation to a new reality in nutrition and eating; and promoting autonomy through patient choice, particularly with meals and mealtimes. This suggests that these elements were most valued in PCNC systems by the patients, support persons and staff included in our study.

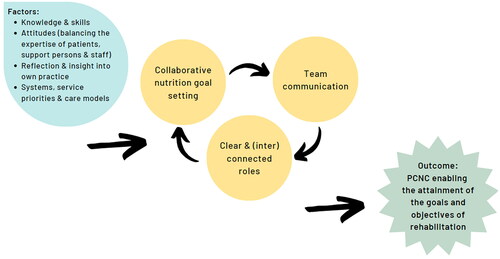

Overall, our study suggests a series of factors and processes considered integral by patients, support persons and staff to enact PCNC, which we have illustrated in . Firstly, identifying what matters most to patients in rehabilitation nutrition care to support collaborative nutrition goal setting which aligns patients’ rehabilitation goals, nutrition goals and nutrition preferences. Activities included in this step may be more structured (e.g., goal setting) or casual (e.g., discussions of patient preferences), depending on the roles and skills of staff. Secondly, ensuring information regarding patients’ nutrition goals and preferences is readily available across the team, including to support staff who are involved in aspects of clinical or mealtime care. This step may be supported by internal handover processes, as tailored to local processes or systems which challenge traditional hierarchies inherent to healthcare teams by better including support staff [Citation64]. Strategies such as the integration of support staff into clinical team meetings, spaces, and informal discussions may be useful to flatten these hierarchies and enable this change. Thirdly, connecting the different aspects of nutrition and mealtime care which occur across the team through interprofessional practice. This step again may be supported by local systems and processes, as well as the skill and attitudes of staff. Finally, the aspirational outcome of this process is that PCNC enables the attainment of the goals and objectives of rehabilitation.

Figure 1. An infographic outlining the influential factors identified in person-centred nutrition care (PCNC) in rehabilitation.

Through our study, we identified opportunities to further explore system-level factors such as digital systems and care models which may impact PCNC in the rehabilitation setting. Additionally, further research may be beneficial to inform service priorities by developing quality indicators for rehabilitation nutrition care systems based on what patients and support persons value. As well, our findings highlight the need for organisations to invest in education and training to empower staff to not only identify what matters most to rehabilitation patients, but better use this information to guide person-centred nutrition and mealtime care. Using tools, such as the Person-Centred Practice Inventory-Staff questionnaire to investigate changes in the person-centredness of practice may also be useful to evaluate skill-building interventions [Citation65].

Limitations & strengths

A limitation of this study is that it primarily on activities and interactions at a unit level. Meetings and discussions at managerial and strategic levels were not observed and thus the influence of organisational and systems-level factors on PCNC may have not been fully realised. Strengths of this study include HO’s prolonged engagement in the field, as well as the use of different qualitative data collection methods. This strengthened the depth and breadth of the data collected, thus supporting the credibility of our findings.

Conclusion

Our findings reveal that identifying what matters to patients and using this to guide care plans is considered essential in PCNC by stakeholders. However, this is at times in tension with profession-specific agendas. We also identified differences and influential factors in the action of PCNC across staffing groups, as well as opportunities to better link PCNC with broader rehabilitation goals and objectives. Future research should consider the healthcare structures, processes and priorities that influence PCNC in rehabilitation settings.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the planning and design of this study. HTO led the completion of data collection and analysis. TLG also provided input into formal analysis, with EO, AMY and TLG all providing supervision and support during the entire analysis process. HTO completed the initial draft of the manuscript, with all authors providing input into further writing, review and editing. All authors have critically reviewed the content of this manuscript and approved the definitive version submitted for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients, support persons and staff who contributed to and/or supported this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hakansson Eklund J, Holmstrom IK, Kumlin T, et al. Same same or different?" a review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(1):3–11.

- Sladdin I, Ball L, Bull C, et al. Patient-centred care to improve dietetic practice: an integrative review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30(4):453–470.

- Barnett A, Ball L, Coppieters MW, et al. Patients’ experiences with rehabilitation care: a qualitative study to inform patient-centred outcomes. Disabil Rehabil. 2023;45(8):1307–1314.

- Jesus TS, Papadimitriou C, Bright FA, et al. Person-Centered rehabilitation model: framing the concept and practice of Person-Centered adult physical rehabilitation based on a scoping review and thematic analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103(1):106–120.

- Jesus TS, Bright FA, Pinho CS, et al. Scoping review of the person-centered literature in adult physical rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2021;43(11):1626–1636.

- Olufson HT, Young AM, Green TL. The delivery of patient centred dietetic care in subacute rehabilitation units: a scoping review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2022;35(1):134–144.

- McMillan SS, Kendall E, Sav A, et al. Patient-centered approaches to health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(6):567–596.

- Morris JH, Kayes N, McCormack B. Editorial: person-Centred Rehabilitation - Theory, practice, and research. Front Rehabil Sci. 2022;3:980314.

- McCormack B, McCance T. The Person-Centred nursing framework. Person-centred nursing research: methodology, methods and outcomes. Switzerland: springer Nature; 2021. p. 12–25.

- McCormack B, Dewing J, McCance T. Developing person-centred care: addressing contextual challenges through practice development. Online J Issues Nurs. 2011;16(2):Manuscript 3.

- McCormack B, McCance TV. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(5):472–479.

- The World Health Organisation. [Internet]. Rehabilitation. [update. 2023 Jan 30; cited 2023 August 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation.

- Landry MD, Jaglal S, Wodchis WP, et al. Analysis of factors affecting demand for rehabilitation services in Ontario, Canada: a health-policy perspective. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(24):1837–1847.

- Young AM, Chung H, Chaplain A, et al. Development of a minimum dataset for subacute rehabilitation: a three-round e-Delphi consensus study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(3):e058725. Mar 25.

- Kayes NM, Papadimitriou C. Reflecting on challenges and opportunities for the practice of person-centred rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2023;37(8):1026–1040. Feb 1:2692155231152970.

- Wade DT. What is rehabilitation? An empirical investigation leading to an evidence-based description. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(5):571–583.

- Jesus TS, Bright F, Kayes N, et al. Person-centred rehabilitation: what exactly does it mean? Protocol for a scoping review with thematic analysis towards framing the concept and practice of person-centred rehabilitation. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e011959.

- Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. [Internet]. Partnering with Patients and Families to Design a Patient- and Family-Centered Health Care System: recommendations and Promising Practices. updated 2008 Apr; ctied 2022 Aug 20] Available from: https://ipfcc.org/resources/PartneringwithPatientsandFamilies.pdf.

- Collins J, Porter J. The effect of interventions to prevent and treat malnutrition in patients admitted for rehabilitation: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015;28(1):1–15.

- Watterson C, Fraser A, Banks M, et al. Evidence based practice guidelines for the nutritional management of malnutrition in adult patients across the continuum of care. Nutr Diet. 2009;66: s1–S34.

- Marshall S, Bauer J, Isenring E. The consequences of malnutrition following discharge from rehabilitation to the community: a systematic review of current evidence in older adults. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27(2):133–141.

- Mullins N. Nutrition and hydration management among stroke patients in inpatient rehabilitation: a best practice implementation project. JBI Evid Implement. 2021;19(1):56–67.

- Dorner B, Friedrich EK. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: individualized nutrition approaches for older adults: long-Term care, Post-Acute care, and other settings. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(4):724–735.

- Pashley A, Young A, Wright O. Foodservice systems and mealtime models in rehabilitation: scoping review. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(11):3559–3586.

- Keller HH, Syed S, Dakkak H, et al. Reimagining nutrition care and mealtimes in Long-Term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(2):253–260 e1.

- Ottrey E, Porter J, Huggins CE, et al. Meal realities" - an ethnographic exploration of hospital mealtime environment and practice. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74(3):603–613.

- McLaren-Hedwards T, D’Cunha K, Elder-Robinson E, et al. Effect of communal dining and dining room enhancement interventions on nutritional, clinical and functional outcomes of patients in acute and Sub-acute hospital, rehabilitation and aged-care settings: a systematic review. Nutr Diet. 2022;79(1):140–168.

- Keller HH, Carrier N, Slaughter SE, et al. Prevalence and determinants of poor food intake of residents living in Long-Term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(11):941–947.

- Olufson H, Ottrey E, Young A, et al. Opportunity, hierarchy, and awareness: an ethnographic exploration across rehabilitation units of interprofessional practice in nutrition and mealtime care. J Interprof Care. 2023;16:1–10.

- Mudge AM, McRae P, Cruickshank M. Eat walk engage: an interdisciplinary collaborative model to improve care of hospitalized elders. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):5–13.

- Hazzard E, Barone L, Mason M, et al. Patient-centred dietetic care from the perspectives of older malnourished patients. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30(5):574–587.

- Bell JJ, Young A, Hill J, et al. Rationale and developmental methodology for the SIMPLE approach: a systematised, interdisciplinary malnutrition pathway for impLementation and evaluation in hospitals. Nutr Diet. 2018;75(2):226–234.

- Ottrey E, Porter J, Huggins CE, et al. Ward culture and staff relationships at hospital mealtimes in Australia: an ethnographic account. Nurs Health Sci. 2019;21(1):78–84.

- Queensland Clinical Senate. [Internet]. Value-based healthcare – shifting from volume to value. [update 2016 Mar; cited 2022 May 10]. Available from: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0028/442693/qcs-meeting-report-201603.pdf.

- Sladdin I, Chaboyer W, Ball L. Patients’ perceptions and experiences of patient-centred care in dietetic consultations. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018;31(2):188–196.

- Brown MEL, Duenas AN. A medical science educator’s guide to selecting a research paradigm: building a basis for better research. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(1):545–553.

- Ryan G. Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Nurse Res. 2018;25(4):14–20.

- Atkinson P, Atkinson P. Ethnography: principles in practice. London: routledge; 2007.

- Angrosino MV. Doing ethnographic and observational research. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2007.

- Bressers G, Brydges M, Paradis E. Ethnography in health professions education: Slowing down and thinking deeply. Med Educ. 2020;54(3):225–233.

- Reeves S, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Qualitative research methodologies: ethnography. BMJ. 2008;337(aug07 3):a1020–a1020.

- Spradley JP. Participant observation. New York: holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1980.

- Tenzek KE. Field notes. The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2017.

- Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, et al. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE guide no. 80. Med Teach. 2013;35(8):e1365-1379–e1379.

- Brinkmann S, Kvale S. Doing Interviews London: SAGE; 2018. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/doing-interviews-2e.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis a practical guide. London: SAGE Publications; 2021.

- Palermo C, Reidlinger DP, Rees CE. Internal coherence matters: lessons for nutrition and dietetics research. Nutr Diet. 2021;78(3):252–267.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual Psychol. 2022;9(1):3–26.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251.

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–352.

- Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(1):10–47.

- Terry G, Kayes N. Person centered care in neurorehabilitation: a secondary analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(16):2334–2343.

- Al-Adili L, McGreevy J, Orrevall Y, et al. Setting goals with patients at risk of malnutrition: a focus group study with clinical dietitians. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(7):2103–2109.

- Whitehead K, Langley-Evans SC, Tischler V, et al. Communication skills for behaviour change in dietetic consultations. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2009;22(6):493–500.

- Swan WI, Vivanti A, Hakel-Smith NA, et al. Nutrition care process and model update: toward realizing People-Centered care and outcomes management. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(12):2003–2014.

- Holdoway A, Page F, Bauer J, et al. Individualised nutritional care for Disease-Related malnutrition: improving outcomes by focusing on what matters to patients. Nutrients. 2022;14(17):3534.

- Waddell A, Lennox A, Spassova G, et al. Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making in hospitals from policy to practice: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):74.

- Jones M, Eggett D, Bellini SG, et al. Patient-centered care: dietitians’ perspectives and experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(11):2724–2731.

- Levey R, Ball L, Chaboyer W, et al. Dietitians’ perspectives of the barriers and enablers to delivering patient-centred care. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2020;33(1):106–114.

- Laur C, Valaitis R, Bell J, et al. Changing nutrition care practices in hospital: a thematic analysis of hospital staff perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):498.

- Laird EA, McCance T, McCormack B, et al. Patients’ experiences of in-hospital care when nursing staff were engaged in a practice development programme to promote person-centredness: a narrative analysis study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(9):1454–1462.

- Yoshida KK, Self HM, Renwick RM, et al. A value-based practice model of rehabilitation: consumers’ recommendations in action. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(20):1825–1833.

- Huglin J, Whelan L, McLean S, et al. Exploring utilisation of the allied health assistant workforce in the victorian health, aged care and disability sectors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1144.

- Slater P, McCance T, McCormack B. The development and testing of the person-centred practice Inventory - Staff (PCPI-S). Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29(4):541–547.