Abstract

We focused on the barriers to the implementation of enabling environments for sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS) in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine. Based on interviews and desktop research, we analyzed overall framework conditions in these countries as well as implementation practices in three cities. Our findings demonstrate that the main problem was the deficit of strategic foresight for urban development. SUDS are mostly promoted by NGOs and fueled by international donors, and this represents a major barrier to their implementation, as NGOs and ‘traditional’ epistemic communities are often not connected. Successful examples of SUDS are missing, often due to regulatory environments forcing SUDS development teams to take suboptimal decisions. In order to be taken seriously by key stakeholders SUDS need to appear in national policy documents. Furthermore, the overall successful implementation of SUDS needs robust governance frameworks while many structural issues are direct results of governance deficits.

1. Introduction

‘Nature-based solutions’ (NBS) is an umbrella term for the family of related ideas and approaches that capture the distinct contributions that ecological processes and ecosystems provide to cities. It was coined in the late 2000s in the context of generating win-win solutions and addressing environmental, economic, and social challenges, in addition to making cities more livable (MacKinnon, Sobrevila, and Hickey Citation2008; IUCN Citation2009; Eggermont et al. Citation2015; Maes and Jacobs Citation2017; Cohen-Shacham et al. Citation2016). It turned from a scholarly concept to a strategic policy approach, as seen in the EU, where the European Commission prioritized NBS as among the top items in the mainstream policy agenda (EC Citation2015, 4; EC Citation2016). According to the European Commission, NBS are deliberate interventions that are “inspired and supported by nature, which are cost-effective, simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic benefits and help build resilience. Such solutions bring more, and more diverse, nature and natural features and processes into cities, landscapes and seascapes, through locally adapted, resource-efficient and systemic interventions” (EC Citation2016).

Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS), as a form of NBS, are also gaining increasing acceptance in urban planning and design to integrate and re(create) the natural water cycle (Fletcher et al. Citation2015; O’Donnell, Lamond, and Thorne Citation2017). By mimicking pre-development hydrology, SUDS offer resilient and adaptive measures that increase infiltration, storage capacity, and attenuation while also providing other co-benefits of green infrastructure (Novotny, Ahern, and Brown Citation2010).

While there is increasing evidence that SUDS can deliver a wide range of goods and services (e.g. de Oliveira et al. Citation2015; Cohen-Shacham et al. Citation2016; Kabisch et al. Citation2016; Sekulova and Anguelovski Citation2017), there is a substantial gap between the promise of NBS and the actual uptake, which is sporadic and below potential (EC Citation2015). As a response, the EU and its member states have initiated several research and capacity-building actions such as Naturvation, Eklipse, OPPLA, ThinkNature, NAIAD etc., that provided fresh insight on indicators, knowledge gaps, and barriers to mainstreaming NBS.

A wide range of such barriers for SUDS and a broader group of NBS were identified and classified as technological, legal, management, institutional, financial, social, and political (e.g. Thorne et al. Citation2018; Kabisch et al. Citation2016; Fernandes and Guiomar Citation2018; Schmalzbauer Citation2018). Barriers may be numerous and difficult to remove, while enabling conditions are insufficient, as SUDS interferes with persistent legacies and capacity constraints in planning, architecture, public health, and municipal management (Kabisch et al. Citation2016), public acceptance of water reuse, contaminant risk, and water reuse management (O’Hogain and McCarton Citation2018). They may require a lot of experimentation, learning, and innovative thinking (Nesshöver et al. Citation2017; Hartmann, Slavíková, and McCarthy Citation2019), and also the presence of institutions accepting and/or promoting them. In most socio-political contexts such conditions are difficult to meet and, as an implication, NBS are rarely mentioned even in the context of the development of sustainable urban water management, whereas “grey” solutions are clearly preferred (Rizvi, Baig, and Verdone Citation2015; Sekulova and Anguelovski Citation2017).

Eastern Europe is particularly interesting in this respect: it has been in the process of continuous socio-economic transition since the late 1980s, which has resulted in a rich mix of institutions belonging to various stages of the transition, and in interplays of many driving forces. These mixes substantially vary across the region, and even such countries as Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, sharing a lot of cultural and historical background, feature distinctively different contexts for sustainability transitions (Shkaruba et al. Citation2021). The same as elsewhere in the region, water-related NBS are largely ignored here (Istenic, Bodík, and Bulc Citation2015; Badiu et al. Citation2019). There are many strong and rather obvious reasons for that; however the reasons (or their relative balance) are not the same in each of the three countries, which is why some variability in approaches may be required in order to approach the situation. At the same time, due to generally out-dated storm drainage infrastructure in massive residential areas, and degradation of river ecosystems, cities in the region urgently need low-cost and low maintenance solutions for sustainable stormwater management.

We recognize the complexity and importance of the problem and consider poor coverage of the region in environmental governance and urban planning literature as well as its vast spatial extent. Our overall aim is therefore to gain a scope on the drivers and implications of enabling and constraining conditions for the development of SUDS in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, and to identify common and individual features of environmental governance regimes in these countries that need to be taken into account when developing relevant policies or transferring best practices. In doing so, we will specifically deal with the following research objectives, recognizing their particular importance for understanding governance contexts for the development of SUDS across Eastern Europe:

to understand socio-cultural, institutional and economic drivers enabling or constraining development of SUDS, with a particular reference to institutional legacies structuring the enabling landscapes, and to the issues with acceptance of technology and policy transfer within these landscapes;

to provide critical reflections on the lessons learned across the EU through the lenses of Eastern European contexts, in a view that the EU is promoting NBS and its best practices worldwide, in particular targeting its neighborhood area through funded actions;

to develop a preliminary comparative perspective on the two previous objectives in order to reflect on sustainability pathways provided by various governance modes and in diverging political cultures and economic contexts.

2. Methodology, case studies, and data

2.1. Analytical approach

Addressing research objective 1, we took a snapshot of barriers for SUDS development in various geographical and governance contexts, and analytical perspectives. The barriers found in the literature were summarized and collated in larger clusters, which were further grouped according to the structure of the research objective in socio-cultural, institutional and economic types of barriers ().

Table 1. Socio-cultural, institutional and economic barriers for SUDS.

demonstrates that the same types of SUDS implementation barriers can be found in contrasting geographical settings and feature in research exploring different analytical perspectives. We can talk, therefore, of common occurrence of the types, although also acknowledging that exact reasons for the barriers to persist may significantly vary in different geographies. For the purposes of our scoping study we therefore used these types of barriers as enquiry points, also checking for any features of enabling landscapes for SUDS in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, which have not been explored in the international literature. In doing so, we used the following analytical plan brought forward based on the review of :

Standards, blueprints, regulations and institutions, paying attention to perceived issues and actual constraints and advantages related to regulatory environments and administrative practices;

Economic considerations as perceived by stakeholders, including considerations related to the economics of SUDS;

Social and behavioral patterns occurring in epistemological and broader stakeholder communities, as they interplay with the above two groups and work together to push or restrain SUDS.

Having consistently employed a comparative cross-regional perspective we have partly addressed the 3rd research objective, and further discussed it in terms of governance of innovation and its following variables:

The overall robustness of national governance frameworks;

Available human and social capital;

Openness to external environmental aid and the availability of institutional infrastructure for fundraising and project implementation;

Openness of policymaking communities and societies at large to SUDS development;

Business climate in countries and particular locations.

To address research objective 2 we took, as a basis for discussion, lessons on NBS policy experimentation drawn from literature based on EU-wide experiences (Sekulova and Anguelovski Citation2017; Frantzeskaki Citation2019), and ensured that the lessons had covered all the types of barriers summarized in .

For the purposes of our analysis we have used a combined approach considering both developments occurring at national levels (including nationwide institutional frameworks, economic and socio-cultural contexts etc) as well as specific situations with SUDS in urban locations in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. We employed a systematic qualitative research methodology to unpack the policy background and the contextual characteristics. Our particular focus was on conditions in which SUDS are emerging, and on factors, processes, mechanisms, strategies, and tools that contributed to their success and failure. We further recognize that although reasons for the development of SUDS can be very different, ranging from flood protection to high-end design statements, any such developments are not very common in the region (and, specifically, in our case study locations). We therefore include in the scope of our study all of them, even “design” ones, keeping in mind their important educational and dissemination functions.

2.2. Case study areas

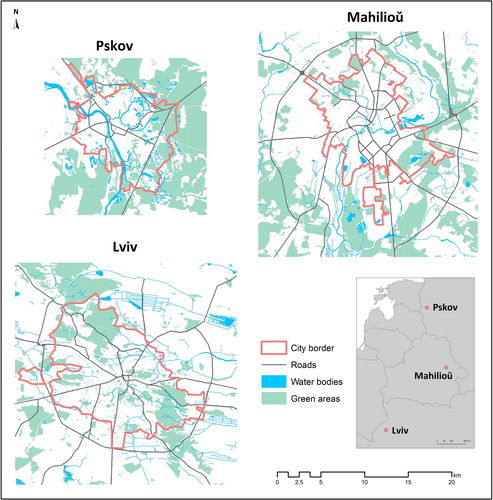

Our case studies were located in Mahilioŭ in Belarus, Pskov in Russia, and Lviv in Ukraine (). Formally, these cities have the same administrative status, although they differ in terms of size and significance (). Our cases cover a broad range of urban contexts while ensuring that they are comparable with each other. Mahilioŭ, Pskov, and Lviv routinely experience major problems with stormwater overflow. Their storm sewerage systems are old and outdated. Municipal services that maintain them do not even have full information on the networks, as we have found out when making an inventory of the cities’ underground infrastructure. In all three cities, significant portions of stormwater are mixed with household and industrial wastewater and are sent to centralized wastewater treatment facilities. The rest of it is discharged into small watercourses without any treatment or with outdated and mostly non-functioning simple sand interceptors installed back in the days of the USSR regime. This aggravates social vulnerability concerns, as long as areas by small watercourses are mostly low-income. None of the studied cities can be recognized as a more successful example of SUDS development compared to others. As such, in this respect they do not stand out from other regional centers in the respective countries. We therefore find our case studies comparable, and also reasonably representative of their national context.

Table 2. Case study areas.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

The qualitative data gathered for the case studies through a mixed-methods approach mainly consists of documents and key-informant interviews, and personal participation and field notes of the authors in some of the SUDS that were studied to resolve or explain ambiguities, if any, and to increase the consistency, reliability, and representativeness of data (Patton Citation2002).

We first focused on the legislative framework, planning documents, regulations, rules, and norms that are relevant for SUDS (see Annex 1, online supplemental data). The list of analyzed SUDS included green roofs, ecoparking and paving surfaces, stormwater management, and green areas and strips (where they are important for infiltration, water purification, or required for water protection purposes). The criteria for the analysis mainly focused on recognizing water-related functions of NBS in the legal framework, setting up general provisions for the design and construction of SUDS, establishing procedures for assessment, and approving NBS-related projects.

The author team ran a series of semi-structured interviews (conducted in 2017–19) with stakeholders involved in the decision-making process on SUDS in all three countries. This included both interviewees concerned with water management or SUDS development specifically in case study locations and with stakeholders concerned with policies and regulations at the national level. The list of interviewees is presented in Annex 2 (online supplemental data). The questions asked were about attitudes toward relevant NBS, own professional perceptions of SUDS, conditions for and barriers to the implementation of SUDS projects, examples and assumptions for future NBS in urban areas, and so on. To fill in the gaps, back up uncertainties and derive alternative perspectives on opinions expressed by interviewees, we consulted local media and social networks.

3. An enabling socio-political environment

3.1. Institutional and regulatory drivers

Major barriers to SUDS recognized in the region were the lack of effective legislation, and the regulatory constraints on SUDS design, construction, operation, and maintenance. NBS and SUDS appeared to be foreign concepts to national regulatory environments, including technical standards and blueprints. Much of technical regulation was outdated, while most of the environmental standards are relatively modern and were often drawn after EU examples or best practices. The following common features have been identified across the region:

Mass-market architectural and planning designs in region’s countries are usually based on ‘typical blueprints’, which are ready-to-use solutions approved by competent national authorities. Checks on construction blueprints and other project documentation are carried out by dedicated agencies that oversee construction expertise, as mandated by national regulation (Annex 1: 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 21, online supplemental data). Some types of projects are exempted from such control, such as landscaping (area improvement), tree planting, arranging flower beds and gardens, and so on. As interviewees assured, any modifications to approved blueprints, even on a one-off basis, involve time consuming and expensive bureaucratic processes and are best avoided, unless a large investment is involved (interviews 1, 2, 16, 18, 24).

Land regulations prescribing permitted land use do not recognize the function of catching and infiltrating rainfall as one that can be associated with green areas and zones (Annex 1: 1, 8, 9, 12, 16, 17, 19, online supplemental data), and only pipe-based sewerage is recognized in this capacity (Annex 1: 13, 15, 20, online supplemental data). When an ‘unrecognised’ SUDS needs to be developed or promoted, the usual way of doing it varies from underplaying the actual purpose in official documents to overlooking all legal constraints altogether (interview 17, 18). Only the following water-related ecosystem functions have been recognized so far in planning documents: water protection zones and strips along water bodies (including special regimes for water bodies used for water supply, recreation, or fishing), groundwater production areas, and periodically flooded zones. All such designations were established back in the USSR era, and ever since the establishment, they have either been challenged (Potapova, Pshenichnikova, and Sokolova Citation2016) or ignored by developers (Shushnyak, Savka, and Verheles Citation2014; Shkaruba, Kireyeu, and Likhacheva Citation2017).

Environmental impact assessment (EIA) and permitting requirements are consistently applied to any new piece of infrastructure (engineering and architectural designs are submitted to expert boards) (Annex 1: 4, 7, 11, online supplemental data). For instance, outdoor parking lots in Belarus and Russia have to be equipped with drainage, sewerage, and local wastewater treatment (Annex 1: 18, online supplemental data; interview 21). If a green parking lot for 2–3 cars needs to be constructed and officially recognized as a parking space, it would evoke all environmental licensing requirements prescribed for parking lots while asphalting a surface of the same size for the same purpose would not need any permissions (interviews 2, 3, 5, 21, 24).

Departmental siloing and segregation were recognized by interviewees who had experience with promoting SUDS-related projects at municipalities, where for example anything that had to do with “green” was always sent to a department responsible for landscape architecture and decoration, while departments dealing with stormwater were interested only in discussions directly concerned with gray infrastructure (interviews 6, 7).

Challenging the regulatory and institutional environment was cited by representatives of various stakeholder groups as a reason for slow development or failure of pilot initiatives involving water-related NBS. As a result, for example, there are no green roofs in Pskov. We identified only one in Mahilioŭ; however, it was designed as a glamorous feature in a premium class apartment bloc. In Lviv, there were no green roofs except one from a pilot project aiming to create green-roofed bus stop pavilions and operating with the intention to scale up if they prove to be a tenable solution (“Green bus stops” Citation2015). Another interesting pilot that was planned to be implemented in Lviv was a green tram line with a grass bed designed to provide stormwater infiltration (“Green tram tracks” Citation2017). However, it is likely to remain a pilot without reaching even the implementation stage, because in order to be implemented it needs a major revision of the actual tram line construction standards (Annex 1: 14, online supplemental data) that still remain unchanged.

Similarly, to develop a constructed wetland, one would need to meet all licensing requirements that are applicable to waste water treatment facilities (interview 3), even if the entire project is only a small vegetated patch designed to slow down stormwater flow discharged from sewerage, and to provide for it some filtering and purification. In many cases involving constructed wetlands, permission-related barriers were even higher than regular ones, because such projects were usually located within water protection zones and strips (interview 3). In known examples from Belarus (interviews 4, 6) and Ukraine (interview 14, 18) the licensing procedure was avoided by branding the wetland as a piece of landscape. Interviewees suggested that the same method would apply to the construction of rainwater filtration beds (interviews 3, 4, 6).

3.2. Economic considerations

Economic considerations have also been mentioned by stakeholders involved in the case studies as an important barrier to SUDS. The following lines of reasoning appeared to be the most commonly used in this context across the whole region:

Paved surfaces are considered by municipalities and businesses to be cheaper to maintain than permeable ones. This concerns both grass and sand/gravel surfaces, and while this standing is very common (interviews 4, 5, 9, 19, 20), it appeared to be a convention not backed by any kind of lifecycle analyses. Calculation of co-benefits (monetary value of cooler or cleaner air, absorption of water, health effects, etc.) or understanding how NBS can save costs as a substitute to conventional infrastructure is not part of the process of evaluating alternatives;

Standard business solutions and proven expertise for the development and maintenance of green roofs, infiltration beds, and constructed wetlands are not available (“Green roofs” Citation2013), which in turn creates unacceptable uncertainties in budgeting, and potentially high costs with the quality not being guaranteed (interviews 1–5, 9, 21);

All relevant SUDS pilots in Mahilioŭ, Lviv, and Pskov that were identified, including landscaping projects based on wild nature-inspired designs, were co-funded by international assistance projects (see Annex 3, online supplemental data for an overview), or by other international initiatives, such as the Covenant of Mayors in Ukraine (Vilkul Citation2014);

The absence of ready blueprints and technical standards for NBS makes their development an exclusive action that raises project costs and delays their implementation significantly (see 3.1); as mentioned in the previous point, such projects are implemented on a one-off basis and with not-for-profit objectives;

Low quality construction within existing housing and commercial stock, as well as poor quality and incomplete construction plans, result in high costs being incurred in preparing for NBS installations such as green roofs (“Green roofs” Citation2013).

Stories of reviewed SUDS projects suggest an additional constraint: most projects in the region are initiated and managed by NGOs, whose knowledge, practical experience, and implementation capacities are substantially limited when compared to, for example, municipalities. With such international projects, NGOs are often trying to plant new concepts, approaches, and terminologies that are foreign to domestic epistemic communities. This may create a misunderstanding, if not conflict, and may lead to lower cost-benefit performance. In top-down administrative set-ups such as Belarus and Russia, NGOs are often not considered as trusted partners that are capable of bringing sizeable benefits to public bodies (Shkaruba and Skryhan Citation2019). This leads to suboptimal partnership building as well as to hindrances to project implementation and sustainability.

3.3. Social and behavioral patterns

Social and behavioral patterns demonstrated by a broad range of stakeholder groups appear to be the most powerful constraint for the development of SUDS. Commonly observed drivers were the following:

Similar to observations in the international literature (Frazer Citation2005; Kronenberg, Bergier, and Maliszewska Citation2017; Badiu et al. Citation2019), citizens recognize housing, parking, and more roads as their primary priorities, while urban nature projects (or any other activities protecting infiltration or infiltration NBS) receive a massive pushback as they usually either require or compete for a lot of space (Klimanova, Kolbowsky, and Illarionova Citation2018) or add extra cost to construction budgets (interviews 1, 2, 11, 16, 18, 24). There is not much appeal for green roofs or parking lots either. They are seen as a luxury rather than as useful utilities, and this further advances social vulnerability issues.

As observed by interviewees, any wilderness in the urban context is strongly associated with mismanagement and poverty, and therefore needs to be managed in a way that often involves the extensive application of paved surfaces. Many water-related NBS are seen as mosquito incubators and cause other concerns about their sanitary soundness (interviews 4, 5, 9, 10, 22). In addition, small watercourses in urban environments are particularly disliked: their networks are steadily shrinking (e.g. confined in underground pipes and tunnels to create greenfields), while wetlands and other ecosystems providing filtration services have already been (or are planned to be) replaced with impermeable pavements.

SUDS were, in principle, recognized and applied by city planners back in the days of the USSR and incorporated in city planning designs as demonstrated by large green spaces allowed between multi-storey houses, abundant green and blue infrastructure elements, etc. (Klimanova, Kolbowsky, and Illarionova Citation2018). However, this segment of the planning and urban management culture does not appear to have survived the hardships of transition, as has also been observed in other countries that were part of the former Soviet bloc (Kronenberg, Bergier, and Maliszewska Citation2017; Badiu et al. Citation2019).

In terms of regulatory non-compliance, we found a silent consensus among public authorities to follow a relaxed approach to breaches in standards and procedures in such areas as public participation (specifically, public hearings), urban forestry, sufficiency of green spaces in city districts or even in master plans and implementation of water protection zoning in cities (Skryhan Citation2014, Citation2016; “Two-thirds” Citation2019; interviews 6, 7, 8, 26). As a result, multi-storey districts developed in the 2000–2010s usually had far less green areas than ones developed in the USSR era (“Two-thirds” Citation2019), and they were also spaced more densely, on average by 2–9% in Pskov and 15% in Lviv (own data). The trend is also observed elsewhere in the region (Datsko Citation2017; “Irina Golubeva” Citation2017; Volynets Citation2017; Dulyaba Citation2018; “Mahilioŭ authorities” Citation2019; Svitanskaya Citation2019). Originally designed flower beds and lawns are replaced by parking lots (interview 6, 7, 12), and this is positively received by local communities with no negative feedback trackable on regular or social media.

Everyday behavioral patterns and social habits are not supportive of the water retention, infiltration, and purification functions of ecosystems. This includes widespread parking on vegetated areas (punishable everywhere, but not enforced), unauthorized construction of garages and sheds in green areas, dumping, and so on. This does not offer much optimism as regards citizens’ self-organization for the promotion of SUDS features in their courtyards. However, there are many local initiatives, usually externally funded, that have managed to develop several convincing demonstration cases (see Shkaruba, Skryhan, and Kireyeu [Citation2015] for analysis and Annex 3, online supplemental data for an overview).

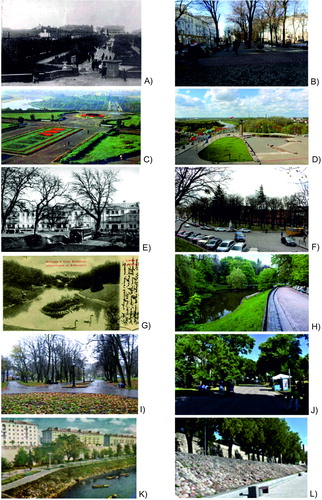

These considerations mostly play the role of a reinforcing factor in regulatory and economic concerns involving budgeting problems, procurement irregularities, corruption, time delays, and missing blueprints. Potentially, they can be overcome with some political will or promises for marketing gains (interviews 6, 7, 17, 23), which are, however, not in place because of the low interest of policymakers and local communities in SUDS and in urban nature in general. This is demonstrated, for example, in many cases in Mahilioŭ or Pskov, where architectural heritage protection regulations were evoked in the case of renovations of large paved squares, which were therefore renovated with no permeable surfaces added (interviews 1, 11, 19). The said reason for this was a desire to preserve historical features, although otherwise the authenticity was not really taken care of (interviews 1, 11, 19). Our analysis of several renovated public spaces in Mahilioŭ and Pskov (including parks) demonstrated that paved impermeable surfaces had never been cut but were always extended as an outcome of renovation projects by 10–15% (). In contrast, in Lviv, reconstructions of parks are reasonably faithful to their historical designs with sand walking pads having been maintained and new constructions having been banned (although not always successfully), at least in historical parks. This is due to a well-developed sense of responsibility for cultural heritage shared by the general public and city leadership (interviews 12, 14, 18). This is a highly idiosyncratic feature of Lviv that is rarely found elsewhere in the region. Mahilioŭ suffered most in this respect as the sense of national identity and heritage value was never cherished in Belarus since its political establishment in 1919 (interviews 6, 7, 10).

Figure 2. Recently renovated public spaces in case study areas. Mahilioŭ: “Kamsamolski park” (A. 1940, B. 2018); Square of Honor (C. 1980, D. 2019) Lviv: “Gubernatorskie valy” (E. 1894, F. 2016); “Stryiskiy park” (G. 1903–1914, F. 2016) Pskov: “Detsky park” (I. 1990s, J. 2013); Embankment of the Velikaya river (K. 1973, L. 2018)

4. Discussion: regional diversity of SUDS enabling landscapes and implications for the governance of innovation

Our findings demonstrate massive problems with SUDS implementation in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, which are aggravated by institutional and economic disorders caused by never-ending socio-economic transitions. It is not surprising in itself, because SUDS implementation appeared to be problematic even in countries with more supportive regulatory frameworks and considerable implementation capacity (see 2.1). Yet, SUDS hold high promise for sustainability transition in the region. They also enjoy some support from EU institutions and member states, while the EU Green Deal and its Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 are expected to bring in more aid and investment (EC Citation2020). In the following section we therefore explore the diversity of SUDS-enabling landscapes across the region and articulate the root causes of implementation barriers and potential opportunities. We further discuss implementation experiences in the region vis-à-vis relevant lessons learned in EU member states.

4.1. Cross-regional diversity of enabling landscapes

Comparisons of Belarus, Russia and Ukraine demonstrate that although the constraints and enabling conditions appear similar, there are also some important differences. summarizes the discussion of fundamental drivers and their impact on national enabling landscapes.

Table 3. Summary of enabling factors for SUDS implementation in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine.

4.1.1. The overall robustness of national governance frameworks

Of the three countries, only Belarus could historically boast of a relatively efficient governance system allowing the achievement of set policy objectives at a reasonable cost (UN 2005), while in Russia and Ukraine governance is rather weak (OECD Citation2006; UN Citation2007). If the regulatory framework restraining SUDS is not functioning well, this malfunction potentially opens up windows of opportunity for SUDS. However, as we observed, important water infiltration and filtering components of green infrastructure such as water protection zones and strips are not enforced strictly in any of the three countries, regardless of the overall robustness of governance (see 3.3 for details).

4.1.2. Available human and social capital

Potentially, Mahilioŭ and Pskov lag far behind Lviv in this respect. Unlike them, Lviv is a large city that attracts creative forces from across the entire country and houses several important universities, research institutions, and activist groups that are also capable of fundraising, including from the EU. As long as external funding is an important precondition for the successful promotion of SUDS (see 3.2), such high fundraising capacity concentrated in Lviv can be expected to bring in substantially more SUDS-related initiatives, and this also helps information and awareness-raising campaigns. The scale and quality of SUDS implementation activities is, nonetheless, not different among these three cities. Some examples that stand apart include, for instance, historical parks in Lviv, which are spared from pavement-dominated reconstruction due to a community-wide feeling for cultural heritage. This is, however, a very authentic feature of Lviv that cannot be extrapolated to the rest of the region, or even to all of Ukraine.

4.1.3. Openness to external environmental aid and the availability of institutional infrastructure for fundraising and project implementation

It is broader in Lviv, and in addition, as long as Ukraine is in association with the EU, it is a target country for many actions and programmes and massive institutional infrastructure is available for fundraising and project management (Delegation of the European Union to Ukraine Citation2016). Some administrative procedures related to international aid are easier to follow in Russia, although there have been some negative recent developments such as the introduction of institutions of ‘foreign agents’ (i.e. NGOs in receipt of foreign grants), and due to recent political trends, public bodies are becoming more cautious as regards finance coming from abroad (Shkaruba et al. Citation2018). As a result of its frontier location, Pskov is still relatively open to international initiatives. Unlike most of Russia, it is also entitled to participate in endeavors of EU transborder regional cooperation (interview 22). In Belarus, any external fundraising was welcomed by public authorities, yet significantly (and increasingly) constrained by resource-consuming and highly restrictive procedures for project registration required by national legislation (interviews 6, 7).

4.1.4. Openness of policymaking communities and societies at large to SUDS development

Overall, gray infrastructure solutions continue to dominate planning and development agendas. This high level of resistance to change represents a strong socio-institutional barrier to mainstreaming NBS and to increasing the confidence of decision-makers and communities to accept, support, and take ownership of new types of infrastructure. In Lviv, the incentives to follow the best EU practices can be assumed as significantly stronger than elsewhere in our case study locations, and it is demonstrable through a number of policy developments. For instance, it was the first city in Ukraine to join the programme for the development of green cities funded by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (“EU to help” Citation2018). In Mahilioŭ and Pskov, we could also identify interest in good practices (interviews 19, 20, 22), but it also needed a strong financial backing, and while it was secured in Pskov and resulted in the reconstruction of the Dendro park (interview 22), in Mahilioŭ, external finance was relatively modest, as were the outcomes of the EU co-funded initiatives (interviews 4, 6, 9). Belarus also had potential for new technology to overcome constraints and barriers because of the administrative culture that encouraged innovative startups in principle. For instance, it helped a student to launch a pilot of green parking lots with recycled plastic used as construction material (“First eco-parking” Citation2018).

4.1.5. Business climate in countries and particular locations

In Ukraine, entrepreneurship plays a very important role and fills more niches than in Belarus or Russia because of weak (although selectively so at times) regulatory environments and low ambitions on the part of the state as regards its participation in the national economy (interviews 2, 6, 24, 26). This creates a large diversity in the supply options in all consumer sectors that are either flexibly responsive to current demands or are also seeking to figure out and address future ones. This does not seem to play an important role at the moment, although it should be encouraging in terms of future endeavors. In Belarus private business, in particular small business, has never been cherished (interviews 1, 2, 3, 5), and public spaces in cities are managed by large companies and municipal-owned companies that retain the names, functions, and management approaches from the USSR era when they were established. While they have large production capacity and, in principle, can be capable of taking on green infrastructure projects of any scale and complexity, they are also very conservative as regards the range of their practices and operations, and prefer to stay within it (interviews 5, 9, 11). In Russia, small business is in a transition from a period of relative laissez-faire in the 1990–2000s to a tighter regulatory environment (Shkaruba, Kireyeu, and Likhacheva Citation2017). The number of business players is shrinking, while corruption in the municipal sector remains high with a common problem of distracting municipal finances from what is necessary to what represents a better opportunity for affiliated businesses (Krylova Citation2018).

4.2. SUDS implementation in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine vis-à-vis EU experience

As long as the EU is considered in Eastern European countries a prime example and source of good practices for most environmental matters (Shkaruba et al. Citation2018), and because NBS and SUDS are broadly and increasingly promoted by EU institutions and member states, the lessons learned by the EU need a critical reflection vis-à-vis the regional SUDS implementation contexts. Indeed, the EU itself provides a very broad variety of such contexts. Although SUDS and NBS are relatively novel management approaches, to date there are already several pioneering scholarly works discussing the lessons of their implementation based on EU-wide overviews, such as Sekulova and Anguelovski (Citation2017) or Frantzeskaki (Citation2019). In our discussion of the relevance of EU implementation experience we loosely followed the key lessons identified in the latter paper. Out of seven lessons brought forward by Frantzeskaki (Citation2019), Lesson #3 focusing narrowly on management and policy experimentation situations was not reviewed as it was found inapplicable to our research context. The remaining Frantzeskaki’s lessons are as follows:

Lesson #1 – NBS needs to be aesthetically appealing for citizens to appreciate and to protect them. This makes a lot of sense in the region’s contexts. Similarly to reports from EU cases (Sekulova and Anguelovski Citation2017), all the known green roof projects were developed because they were considered as glamorous additions to home designs rather than as NBS features. Importantly, it worked from a negative perspective more often, wherein citizens do not like wild nature and are not interested in SUDS. However, if ecosystem services are explained well in detail, this may partly support the reconciliation between citizens and the wilderness, although they may still insist on some grooming.

Lesson #2 – NBS creates new green urban commons. This appears to be fundamentally universal and similar to Lesson #5 – NBS requires a collaborative governance approach. A shared understanding and appreciation of NBS is absolutely important to ensure the acceptance and correct understanding of SUDS functions by units in charge of their maintenance, and to prevent vandalism, at least on the part of the local inhabitants. In the region, SUDS-related projects usually fall outside the mainstream and are funded externally (even if they were locally initiated), and this particularly underlines the value of successful communication strategies reaching a broad range of stakeholders. Our findings reveal an important potential dilemma in relation to these lessons. As discussed in 3.1, in Belarus, in the context of the planning and construction stages of filtering wetlands and infiltration beds, it may be advisable to brand them as landscaping forms in order to rule out building and environmental permitting requirements and/or to escape the negative attitudes of the local citizens. On the one hand, this helps to keep design costs low and avoid significant delays. However, we assume that some potential problems can occur at the maintenance stage. For instance, environmental infrastructure objects can be managed further without considering SUDS, or local citizens would be tempted to request its removal if they do not like the design or need the space for other purposes. Any ethically correct perspective would require that inclusiveness and transparency be incorporated fully from the very first step in such projects. However, this is difficult advice to sell, as project timeframes are usually very tough and deliverables need to be provided before funding eligibility periods run out. SUDS project teams need to be aware of this even before they start their fundraising efforts and must also be aware of choices and non-choices they might face.

Lesson #4 – Different fora are needed for co-creating NBS, and they must include and learn from urban social innovations. This was less obvious in our research contexts. Our lesson focused more on the value of existing institutions of knowledge sharing and creation, and how they should be carefully explored in such conservative policymaking contexts as Russia and, in particular, Belarus. It is even more important to involve municipal and higher-level decision-makers who tend to be hostile to a wave of what they consider deceptive ‘hipster urbanism’. In Lviv, as well as in larger centers in Russia, Lesson # 4 is more relevant, as municipal politicians tend to meet the expectations of their younger and westernized electorate base.

Lesson #6 – An inclusive narrative of the mission for NBS can bridge knowledge and agendas across different departments of the city and tackle departmental disputes. The importance of this lesson is limited by the fact that SUDS developments are, at most, not driven by municipalities, and that environmental concerns are very marginal in policy agendas. This needs to be promoted even in spite of strong siloing in municipalities where is also recognized as an important barrier in EU contexts (Kabisch et al. Citation2016): in the case of some participatory events arranged by third parties (e.g. NGOs) in Mahilioŭ, public servants from various departments were meeting for the first time, although they were tackling similar issues.

Lesson #7 – NBS needs to be designed in such a way and scale that lessons for their effectiveness can be easily harvested and, as thus, can be easily replicated in other locations. This is particularly important in situations in which overall skepticism regarding SUDS is so strong, when demonstration cases are so few, and the quality of implementation is compromised because of low budgets and poor expertise (“Green roofs” Citation2013). The few SUDS that were developed in the USSR era and that have survived since then are not in the best shape now and cannot be taken as convincing examples worth replication.

4.3. Beyond the EU experience: coping with the institutional reality

The main factor diverting Eastern European lessons from the EU’s lessons is that the SUDS agenda is not backed by political will from the highest floors and financial support to both expert communities and specific management actions. The fact that most SUDS-related activities are funded by international donors, on the one hand, drives SUDS developments independently of biases and preconceptions of domestic policy and business circles. On the other hand, it can also drive such activities on one of the diverging paths, the first being successful integration with national and local contexts, while the other is driving the SUDS agenda further into a marginal zone. The former is clearly evolving in Lviv, although with a lot of disruptions. In the case of Mahilioŭ and Pskov, we observe a delicate balance between both processes: while municipalities cautiously accept gifts and are interested in obtaining more, the actual transition of approaches and regular practices does not really take place.

From a donor’s perspective and following the agency theory (McLean Citation2015), the effectiveness of a funded action can be framed as the donor’s ability to provide the recipients (i.e. the agents) with the incentives encouraging the recipients to pursue the donor’s objectives (Victor, Raustiala, and Skolnikoff Citation1998). If measured by the number of their own resources put into the project by aid beneficiaries (Zürn Citation1998), then all the funded actions are extremely successful, as formal co-financing requirements are always met by municipalities and governmental agencies. As observed for Russia (Shkaruba et al. Citation2018) (and partly for Belarus), ‘real’ co-financing (i.e. involving the actual movement of finances or other resources) occurs only if such activities were very likely to be implemented at some point later without any external assistance. On the one hand, this can be interpreted as a sign of a strong degree of interest from the perspective of the recipients; however, on the other hand, that somewhat compromised the very notion of ‘effectiveness’, unless the donor had reasons for this specific action to occur sooner than expected otherwise. At the same time, as our findings demonstrate, the quality of the funded output can be extremely variable, as the actual demonstration value of created solutions can be limited by problems with permitting, or for the same reason, design and location of SUDS can be greatly suboptimal (see 3.1). Most aid recipients aim at the best possible result and as long as donors are supposed to be interested in it, the solution is at their end: for example, providing two-stage grant support including both designing and permitting as well as actual implementation of SUDS, or exploring options for improving the regulatory environment. The latter is addressed in Belarus and Ukraine by several EU co-funded projects, although progress is very slow.

Another significant factor going beyond the EU lessons is that the shadow economy is important in all three countries, as the municipal sector is most prone to corruption. According to the 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index published by Transparency International (Transparency International Citation2019), Belarus ranked 70th globally and this is comparable in terms of perceived corruption among the EU lower ranks (just a bit lower than Greece’s 67th rank and slightly ahead of Bulgaria’s 77th rank). Ukraine and Russia rank even lower with their 120th and 138th positions. For instance, as we noted in the previous section and observed elsewhere (Shkaruba et al. Citation2021; Krylova Citation2018), while corruption mechanisms in the municipalities within the region are usually not legally challenged in a systematic way, many procurement patterns give stakeholders strong suspicions that corruption was indeed involved. The reconstruction of paved surfaces is a particularly sensitive subject (interviews 6, 7, 17, 23), and in itself can be a powerful driver of municipal investments in pavement projects, as opposed to investments in green surfaces. Taking Ostrom’s call for the use of nested institutional arrangements in order to create functional governance regimes (Ostrom Citation1990), one would suggest making use of existing corruption incentives for promoting SUDS. It is not impossible, as doubtful deals involving green infrastructure components are also known to the public in the region (interviews 6, 7, 17, 23). Ethical considerations aside, this would be unlikely to benefit SUDS, as even in the situation with pavements, corruption incentives may only lead either to low quality products or to regular re-pavement, depending on the budgets available. Fighting corruption appears to be a more gainful strategy in the long-term, although a challenging one in terms of short-term success. Although the three countries rank differently in terms of corruption perceptions, it also needs to be noted that forms and mechanisms of corruption in municipalities are different, and their specific impact on SUDS is still be understood.

Last, but not least, our interviewees observed an overall move from a more idealistic kind of thinking to what Mulligan et al. (Citation2020, 12) described as “…more pragmatic solutions based on constraints of space, time, budget, existing conditions and findings on-site, new adjacent infrastructures, and politics”. As we noted elsewhere, the academic urbanism of the late USSR epoch had many aspirational components, encouraged strategic foresight and demonstrated a lot of interest in green and blue infrastructure (Kronenberg, Bergier, and Maliszewska Citation2017). The overall development of urban planning practice in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine gives an impression that such USSR legacy is regarded as a kind of futile idealism that cannot be taken seriously in our pragmatic times. This tendency deserves dedicated research, especially in the light of such concepts and approaches as SUDS, NBS or ecosystem services being internationally recognized as important innovations in urban planning.

5. Concluding remarks

We focused on the barriers to the implementation of enabling environments for SUDS in Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine. There is a high degree of consistency in the responses from all three cities in this study on the importance of implementation barriers and their interrelationships. While these findings generally concur with those of previous studies, they manifest differently because of the differences in the institutional system. Many of the barriers identified are considered difficult to overcome because of their systemic nature, because of how embedded they are within institutional practices, processes, and cultures, and because of the lack of strategies for dealing with such socio-institutional barriers in the region.

Although our approach of combined analysis of the national framework conditions and our in-depth analysis of the case studies does provide a clear understanding of the subject matter, we also realize that this study has its own limitations. A broader range of cases in all three countries would be necessary for a comprehensive understanding of the national and regional enabling environments for SUDS. However, even based solely on our findings, we can offer the first conclusions for key issues and solutions for overcoming implementation barriers:

The main problem is the deficit in strategic foresight for urban development at the national and local levels. Even core strategic documents address short-term rather than long-term problems and perspectives, and international practices (both the best and the worst) are not critically reviewed. Moreover, our findings demonstrate a trend of an overall move in city planning communities from a more idealistic (yet strategic in its nature) kind of thinking embedded within planning approaches from the Soviet era, to more pragmatic ones, where pragmatism is understood as the creation of benefits in the short term at the expense of strategic visions.

SUDS are mostly promoted by NGOs and fueled by international donors. This is a major barrier to their integration into domestic institutional contexts, as NGOs and ‘traditional’ epistemic communities usually have problems in establishing trust and functional relationships.

Successful examples of SUDS are missing. In existing regulatory environments and under commonly occurring grant management rules, such successful examples are extremely difficult to establish, as SUDS development teams are forced to take suboptimal decisions that also impair project sustainability aspects. This needs to be fixed both on the part of both national regulators as well as international donors.

SUDS or NBS in general need to appear in national policy documents in order to be taken seriously by municipal authorities and other key stakeholders. This is feasible in Ukraine given its orientation toward the EU, and in Belarus, given the interest of its government in using innovative practices. However, it is a more difficult affair in Russia because of the scale of its national government and the level of complexity of its policymaking environment.

The successful implementation of SUDS is an iterative process that involves integration across fields and departments as well as adaptive management. All this needs a robust governance framework while many structural issues have been identified in our research directly as a result of governance deficits.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Badiu, Denisa L., Diana A. Onose, Mihai R. Niță, and Raffaele Lafortezza. 2019. “From ‘Red’ to Green? A Look into the Evolution of Green Spaces in a Postsocialist City.” Landscape and Urban Planning 187: 156–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.07.015.

- Bayrak, Galyna. 2016. “The Channels of River of Lviv: Transformation during the Historical Epoch and Modern Stage.” Visnyk of the Lviv University. Series Geography 50 (50): 3–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.30970/vgg.2016.50.8671.

- Brink, Ebba, Theodor Aalders, Dóra Ádám, Robert Feller, Yuki Henselek, Alexander Hoffmann, Karin Ibe, et al. 2016. “Cascades of Green: A Review of Ecosystem-Based Adaptation in Urban Areas.” Global Environmental Change 36: 111–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.11.003.

- Cohen-Shacham, Emmanuelle, Gretchen Walters, Christine Janzen, and Stewart Maginnis, eds. 2016. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges. Gland: IUCN.

- Datsko, Olesya. 2017. “How Lviv Becomes a Ghetto or Inhuman Seal from the City Council.” Forpost, Lviv's Public Portal, May 17. http://forpost.lviv.ua/txt/suspilstvo/3725-yak-lviv-peretvoriuiut-na-hetto-abo-neliudske-ushchilnennia-vid-miskoi-rady

- Delegation of the European Union to Ukraine. 2016. “EU Projects in Ukraine.” Delegation of the European Union to Ukraine. May 16. https://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/ukraine_en/1938/EU%20Projects%20in%20Ukraine

- de Oliveira, Jose A. Puppim, Christopher N. H. Doll, Jose Siri, Magali Dreyfus, Hooman Farzaneh, and Anthony Capon. 2015. “Urban Governance and the Systems Approach to Health-Environment Co-Benefits in Cities.” Cadernos de Saúde Pública 31 (suppl 1): 25–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00010015.

- DMP (Road and Bridge Enterprise). 2020. “About Road and Bridge Enterprise”. Accessed August 1, 2020. http://mgkudmp.mogilev.by/o-nas

- Droste, Nils, Christoph Schröter-Schlaack, Bernd Hansjürgens, and Horst Zimmermann. 2017. “Implementing Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Areas: Financing and Governance Aspects.” In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas. Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice, edited by Nadja Kabisch, Horst Korn, Jutta Stadler, Aletta Bonn, 307–321. Cham: Springer.

- Dulyaba, Natalya. 2018. “The Residents Will Protest against the Total Development of the Residential District.” Latest News, portal.lviv.ua, October 31. https://portal.lviv.ua/news/2018/10/31/meshkantsi-pid-goloskom-protestuvatimut-proti-totalnoyi-zabudovi-mikrorayonu

- Du Toit, Marié J., Sarel S. Cilliers, Martin Dallimer, Mark Goddard, Solène Guenat, and Susanna F. Cornelius. 2018. “Urban Green Infrastructure and Ecosystem Services in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Landscape and Urban Planning 180: 249–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.06.001.

- EC (European Commission). 2015. Towards an EU Research and Innovation Policy Agenda for Nature-Based Solutions & Re-Naturing Cities: Final Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on ‘Nature-Based Solutions and Re-Naturing Cities’. Brussels: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Climate Action, Environment, Resource Efficiency and Raw Materials.

- EC (European Commission). 2016. “Policy Topics: Nature-Based Solutions.” https://ec.europa.eu/research/environment/index.cfm?pg=nbs

- EC (European Commission). 2020. “EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 (COM2020 380).” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1590574123338&uri=CELEX:52020DC0380

- Eggermont, Hilde, Estelle Balian, José Manuel N. Azevedo, Victor Beumer, Tomas Brodin, Joachim Claudet, Bruno Fady, et al. 2015. “Nature-Based Solutions: New Influence for Environmental Management and Research in Europe.” GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 24 (4): 243–248. doi:https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.24.4.9.

- “EU to Help Improve Solid Waste Management in the Ukrainian City of Lviv.” 2018. EU Neighbours: East, News, June 6. https://www.euneighbours.eu/en/east/stay-informed/news/eu-help-improve-solid-waste-management-ukrainian-city-lviv

- Fernandes, João Paulo, and Nuno Guiomar. 2018. “Nature-Based Solutions: The Need to Increase the Knowledge on Their Potentialities and Limits.” Land Degradation & Development 29 (6): 1925–1939. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2935.

- “First Eco-parking was Built in Grodno. Do You Want the Same in Your Yard?” 2018. NewGrodno.by, April 22. https://newgrodno.by/auto/v-grodno-postroili-pervuyu-ekoparkovku-hotite-takuyu-zhe-v-svoem-dvore

- Fletcher, Tim D., William Shuster, William F. Hunt, Richard Ashley, David Butler, Scott Arthur, Sam Trowsdale, et al. 2015. “SUDS, LID, BMPs, WSUD and More: The Evolution and Application of Terminology Surrounding Urban Drainage.” Urban Water Journal 12 (7): 525–542. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1573062X.2014.916314.

- Frantzeskaki, Niki. 2019. “Seven Lessons for Planning Nature-Based Solutions in Cities.” Environmental Science & Policy 93: 101–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.12.033.

- Frazer, Lance. 2005. “Paving Paradise: The Peril of Impervious Surfaces.” Environmental Health Perspectives 113 (7): A456–A462. doi:https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.113-a456.

- “‘Green’ Bus Stops Will be Constructed in Lviv.” 2015. Doroga.ua, June 3. http://www.doroga.ua/Pages/News.aspx?NewInfoID=8845

- “Green Roofs in Russia: Problems and Perspectives.” 2013. Green Buildings 2: 28–31. http://green-buildings.ru/ru/zelenye-krovli-v-rossii-problemy-i-perspektivy

- “Green Tram Tracks Are Wanted to Construct in Lviv.” 2017. Passenger Transport, April 7. https://traffic.od.ua/news/eltransua/1193043

- Hartmann, Thomas, Lenka Slavíková, and Simon McCarthy. 2019. “Nature-Based Solutions in Flood Risk Management.” In Nature-Based Flood Risk Management on Private Land, edited by Tomas Hartmann, Lenka Slavikova, and Simon McCarthy, 3–8. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23842-1..

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). 2009. No Time to Lose: Make Full Use of Nature-Based Solutions in the Post-2012 Climate Change Regime. Position paper on the Fifteenth Session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 15). Gland: IUCN.

- “Irina Golubeva about the Upcoming Construction of Skyscrapers: This is a Chaotic Development of the City, There Is No Smell of Architecture.” 2017. Pskov News Feed, April 20. https://pln-pskov.ru/society/275112.html

- Istenic, Darja, Igor Bodík, and Tjasa Griessler Bulc. 2015. “Status of Decentralised Wastewater Treatment Systems and Barriers for Implementation of Nature-Based Systems in Central and Eastern Europe.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 22 (17): 12879–12884. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-014-3747-1.

- Kabisch, Nadja, Niki Frantzeskaki, Stephan Pauleit, Sandra Naumann, McKenna Davis, Martina Artmann, Dagmar Haase, et al. 2016. “Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Urban Areas: Perspectives on Indicators, Knowledge Gaps, Barriers, and Opportunities for Action.” Ecology and Society 21 (2): 39. doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08373-210239.

- Klimanova, Oxana, Eugeny Kolbowsky, and Olga Illarionova. 2018. “Impacts of Urbanization on Green Infrastructure Ecosystem Services: The Case Study of Post-Soviet Moscow.” Belgeo 4 (4). doi:https://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.30889.

- Kronenberg, Jakub, Tomasz Bergier, and Karolina Maliszewska. 2017. “The Challenge of Innovation Diffusion: Nature-Based Solutions in Poland.” In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas. Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice, edited by Nadja Kabsich, Horst Korn, Jutta Stadler, and Aletta Born, 291–305. Basel: Springer Nature. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56091-5_17.

- Krylova, Yulia. 2018. “The Role of Entrepreneurial Organizations in Organizing Collective Action against Administrative Corruption: Evidence from Russia.” Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 26 (1): 87–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25739638.2018.1419907.

- LVK (Lviv VodoKanal). 2020. “About Lviv Vodocanal”. Accessed August 1, 2020. https://lvivvodokanal.com.ua/aboutus/facts/

- MacKinnon, Kathy, Claudia Sobrevila, and Valery Hickey. 2008. Biodiversity, Climate Change and Adaptation: Nature-Based Solutions from the Word Bank Portfolio. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/6216.

- Maes, Joachim, and Sander Jacobs. 2017. “Nature-Based Solutions for Europe’s Sustainable Development.” Conservation Letters January Letters 10 (1): 121–124. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12216.

- “Mahilioŭ Authorities Refused to Build a Residential Building on the Site of the School Stadium.” 2019. Naviny.by, September 22. https://naviny.by/new/20190401/1554111015-vlasti-mogileva-otkazalis-ot-stroitelstva-zhilogo-doma-na-meste-shkolnogo

- MVK (Mahilioŭ VodoKanal). 2020. “About Mahilioŭ VodoKanal”. Accessed August 1, 2020. http://vodokanal.mogilev.by/history

- MSOL (Main Statistical Office in Lviv Region). 2020. “Region Passport.” Accessed August 1, 2020. http://database.ukrcensus.gov.ua/regionalstatistics/pasport.asp

- MSOM (Main Statistical Office of Mahilioŭ Region). 2020. “Official Statistics.” Accessed August 1, 2020. http://mogilev.belstat.gov.by/ofitsialnaya-statistika/

- McLean, Elena V. 2015. “A Strategic Theory of International Environmental Assistance.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 27 (2): 324–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0951629814531669.

- Mguni, Patience, Lise Herslund, and Marina Bergen Jensen. 2015. “Green Infrastructure for Flood-Risk Management in Dar Es Salaam and Copenhagen: Exploring the Potential for Transition towards Sustainable Urban Water Management.” Water Policy 17 (1): 126–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2014.047.

- Mukhtarov, Farhad, Carel Dieperink, Peter Driessen, and Janet Riley. 2019. “Collaborative Learning for Policy Innovations: Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems in Leicester.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (3): 288–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1627864.

- Mulligan, Joe, Vera Bukachi, Jack Campbell Clause, Rosie Jewell, Franklin Kirimi, and Chelina Odbert. 2020. “Hybrid Infrastructures, Hybrid Governance: New Evidence from Nairobi (Kenya) on Green-Blue-Grey Infrastructure in Informal Settlements. Urban Hydroclimatic Risks in the 21st Century: Integrating Engineering, Natural, Physical and Social Sciences to Build Resilience.” Anthropocene 29: 100227.

- Nesshöver, Carsten, Timo Assmuth, Katherine N. Irvine, Graciela M. Rusch, Kerry A. Waylen, Ben Delbaere, Dagmar Haase, et al. 2017. “The Science, Policy and Practice of Nature-Based Solutions: An Interdisciplinary Perspective.” The Science of the Total Environment 579: 1215–1227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.11.106.

- Novotny, Vladimir, Jack Ahern, and Paul Brown. 2010. Water Centric Sustainable Communities: Planning, Retrofitting and Building the Next Urban Environment. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- O’Donnell, Emily C., Jessica E. Lamond, and Colin R. Thorne. 2017. “Recognising Barriers to Implementation of Blue-Green Infrastructure: A Newcastle Case Study.” Urban Water Journal 14 (9): 964–971. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1573062X.2017.1279190.

- O’Hogain, Sean, and Liam McCarton. 2018. “Constraints and Barriers to the Adoption of NBS.” In: A Technology Portfolio of Nature Based Solutions, 103–104. Cham: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73281-7_5.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development). 2006. Environmental Policy and Regulation in Russia: The Implementation Challenge. Paris: OECD. http://www.oecd.org/environment/outreach/38118149.pdf

- Ostrom, Elinor. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pedersen Zari, Maibritt, Gabriel Luke Kiddle, Paul Blaschke, Steve Gawler, and David Loubser. 2019. “Utilising Nature-Based Solutions to Increase Resilience in Pacific Ocean Cities.” Ecosystem Services 38: 100968. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100968.

- Potapova, Elena V., Maria E. Pshenichnikova, and Oksana E. Sokolova. 2016. “Investigation of the Water Protection Zones of Rivers Irkutsk.” The Bulletin of Irkutsk State University. Series Earth Sciences [Izvestiya Irkutskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta. Serya ‘Nauki o Zemle’] 15: 83–103.

- PCA (Pskov City Administration). 2020. “Territory.” Accessed August 4, 2020. http://pskovadmin.ru/about_pskov/territory

- PVK (Pskov VodoKanal). 2020. “Pskov Vodokanal Today.” Accessed August 1, 2020. http://www.vdkpskov.ru/about_the_company/water_canal_today/

- Rizvi, Ali Raza, Saima Baig, and Michael Verdone. 2015. Ecosystems Based Adaptation: Knowledge Gaps in Making an Economic Case for Investing in Nature Based Solutions for Climate Change. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/45156

- Schmalzbauer, Andreas. 2018. Barriers and Success Factors for Effectively Co-Creating Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Regeneration. Deliverable 1.1.1, CLEVER Cities, H2020 Grant No. 776604. https://clevercities.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/Resources/D1.1_Theme_1_Barriers_success_factors_co-creation_HWWI_12.2018.pdf

- Sekulova, Filka, and Isabelle Anguelovski. 2017. The Governance and Politics of Nature-Based Solutions. Deliverable 1.3. Part VII of NATURVATION. https://naturvation.eu/sites/default/files/news/files/naturvation_the_governance_and_politics_of_nature-based_solutions.pdf

- Shkaruba, Anton, Hanna Skryhan, and Viktar Kireyeu. 2015. “Sense-Making for Anticipatory Adaptation to Heavy Snowstorms in Urban Areas.” Urban Climate 14 (4): 636–649. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2015.11.002.

- Shkaruba, Anton, Viktar Kireyeu, and Olga Likhacheva. 2017. “Rural-Urban Peripheries under Socioeconomic Transitions: Changing Planning Contexts, Lasting Legacies, and Growing Pressure.” Landscape and Urban Planning 165: 244–255. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.05.006.

- Shkaruba, Anton, Olga Likhacheva, Viktar Kireyeu, and Tatiana Vasileva. 2018. “European Environmental Assistance to the Region of Pskov in Northwest Russia: Sustainability, Effectiveness and Implications for Environmental Governance.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 20 (2): 236–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1398639.

- Shkaruba, Anton, and Hanna Skryhan. 2019. “Chernobyl Science and Politics in Belarus: The Challenges of Post-Normal Science and Political Transition as a Context for Science–Policy Interfacing.” Environmental Science & Policy 92: 152–160. . doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.11.024.

- Shkaruba, Anton, Hanna Skryhan, Olga Likhacheva, Viktar Kireyeu, Attila Katona, Sergey Shyrokostup, and Kalev Sepp. 2021. “Environmental Drivers and Sustainable Transition of Dachas in Eastern Europe: An Analytical Overview.” Land Use Policy 100: 104887. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104887.

- Shushnyak, Vladimir, Halina Savka, and Yury Verheles. 2014. “The Inventory Results of Water Objects of Lviv.” Visnyk of the Lviv University. Series Geography 48 (48): 322–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.30970/vgg.2014.48.1357.

- Skryhan, Hanna. 2014. “Is City Planning an Instrument for Urban Conflict Resolution?” In CUI’14: Contemporary Urban Issues Conference Proceedings, November 13–15, 2014, 29–39. Istanbul: DAKAM.

- Skryhan, Hanna. 2016. “Mahilioŭ: Features of the Morphological and Functional City Structures in the Socialist Period.” Bulletin of Brest University. Series 5. Chemistry, Biology, Earth Science 1: 137–144.

- Svitanskaya, Julia. 2019. “Sadovy! Don't Build it! Lviv Is not Your Firm!” Vlogos, July 31. https://vgolos.com.ua/articles/sadovyj-ne-buduj-lviv-ne-tvoya-firma_1031272.html

- Thorne, Colin R., Emily C. Lawson, Conni P. Ozawa, Samantha L. Hamlin, and Leonard A. Smith. 2018. “Overcoming Uncertainty and Barriers to Adoption of Blue-Green Infrastructure for Urban Flood Risk Management.” Journal of Flood Risk Management 11 (52): S960–S972. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12218.

- Transparency International. 2019. Corruption Perceptions Index – 2018. Berlin: Transparency International. https://www.transparency.org/files/content/pages/2018_CPI_Executive_Summary.pdf

- “Two-Thirds of the Country's Cities Do Not Comply with Landscaping Standards.” 2019. SB.by, March 11. https://www.sb.by/articles/zelenoe-more-raboty.html

- UN (United Nations). 2005. “2nd Environmental Performance Review of Belarus.” Environmental Performance Reviews Series No. 22. New York: United Nations.

- UN (United Nations). 2007. “2nd Environmental Performance Review of Ukraine.” Environmental Performance Reviews Series No. 24. New York: United Nations.

- van Ham, Chantal, and Helen Klimmek. 2017. “Partnerships for Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Areas: Showcasing Successful Examples.” In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice, edited by Nadja Kabisch, Horst Korn, Jutta Stadler, and Aletta Bonn, 275–289. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Victor, David G. Kal Raustiala, and Eugene B. Skolnikoff, eds. 1998. The Implementation and Effectiveness of International Environmental Commitments. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Vilkul, O. 2014. “‘Covenant of Mayors’ Empowers Regions to Implement Energy-Saving Technologies.” Governmental Portal, January 23. https://www.kmu.gov.ua/ua/news/246997088

- Volynets, Anna. 2017. “Houses and Cities: Compaction Is Perfect in One Place and Disaster in Another.” Green Portal, October 24. http://greenbelarus.info/articles/24-10-2017/doma-i-goroda-uplotnenie-idealno-v-odnom-meste-i-katastrofa-v-drugom

- Zürn, Michael. 1998. “The Rise of International Environmental Politics.” World Politics 50 (4): 617–649. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100007383.