Abstract

In 2013, Mexico was the first developing country to adopt a carbon tax, confounding expectations that adoption of such taxes is mostly driven by international commitments and hindered by economic concerns: Mexico was not subject to international climate commitments and constituted an economy dependent on oil and exports to its NAFTA trading partners, which did not price carbon. To address this puzzle, we examine the relationship between environmental and economic factors in the adoption of the tax and whether they originate from the international or national level. We find that the idea of carbon pricing was introduced from abroad, allowing entrepreneurs to frame the carbon tax as economically and environmentally beneficial and build a coalition spanning economic and environmental actors. The 2012 elections and resulting fiscal reform moved the tax onto the legislative agenda and secured its passage.

1. Introduction

An increasing number of countries have adopted carbon taxes (World Bank Citation2019). These countries cover countries at varying levels of income, emissions intensity, environmental policy and international commitment to mitigate climate change, confounding the expectation that carbon taxes would diffuse among similar countries (Skovgaard, Sacks Ferrari, Knaggård Citation2019). In this context, the 2013 Mexican carbon tax is highly instructive. It was the first carbon tax adopted by a developing country.Footnote1 At the time of adoption, Mexico did not have the mitigation commitments it has today under the Paris Agreement, puzzling those who define carbon taxes as a response to an international, environmental collective action problem (see inter alia Aldy and Stavins Citation2012; Nordhaus Citation2019; Keohane and Victor Citation2016). More importantly, Mexico was characterized by a range of economic factors often identified as impeding climate policy, especially carbon taxes (Steinebach, Fernández-I-Marín, and Aschenbrenner Citation2020; Mildenberger Citation2020). The Mexican economy largely depends on oil production (OECD Citation2019) and carbon-intensive exports, particularly to its NAFTA partners, which did not have carbon pricing policies at the time (Ramírez Sánchez, Calderón, and Sánchez León Citation2018). Furthermore, Mexico is not characterized by a high level of environmental governance, and its low-carbon industry is limited in size and political influence, in contrast to the nationally owned oil company PEMEX (Rosas-Flores Citation2017). The literature on economic-environmental relations and carbon taxes would expect economic objectives to outweigh environmental objectives in countries characterized by fossil fuel production, competition from countries without similar environmental protections, and limited attention to environmental issues (see e.g. Mildenberger Citation2020; Steinebach, Fernández-I-Marín, and Aschenbrenner Citation2020), all of which apply to Mexico. Furthermore, economic and environmental factors in Mexico operate through a majoritarian political system and decentralized policy-making (Mayer-Serra Citation2017), factors considered detrimental to climate action and particularly carbon pricing (Mildenberger Citation2020; Harrison and Sundstrom Citation2007; Lachapelle and Paterson Citation2013).

This context would lead to the expectation that Mexico would not adopt the carbon tax, which was set at US$3.50 (low compared to developed country carbon taxes), yet has abated estimated 1.8 million tCO2-and covered over 30% of national greenhouse effect gas emissions—the second largest coverage in the region (Pizarro Citation2021; MEXICO2, Environmental Defense Fund, and IETA Citation2018). Based on the above-mentioned literature, we focus on economic and environmental factors, arguing that whether their relationship is conflictual or synergetic has been underexplored. We explore the relationship between these factors from the starting point that whether economic factors work in favor of or against carbon taxes is not pre-given. The relationship between environmental and economic factors has often been decisive for environmental policymaking, since synergistic relationships between economic and environmental objectives improve the chances of adopting environmental policies, and vice versa for conflictual relationships (Jacobs Citation2012; Skovgaard Citation2014). Carbon taxes may be framed as entailing either a synergistic relationship between environmental and economic objectives (if its fiscal benefits and economically rational nature are emphasized) or a conflictual one (if the negative effects on the country’s economic competitiveness are emphasized). Furthermore, we focus on whether economic and environmental factors originate within Mexico or abroad, since their role may differ depending on their origin. For instance, the idea of pricing carbon has international origins, whereas fiscal concerns originate on the national level.

The relationship between international and national, economic and environmental factors is important, since explaining the adoption of a policy requires not only identifying the presence of a factor, but also how it actually influenced the process leading to the adoption (Paterson et al. Citation2014). Several countries may be described as unlikely cases for carbon taxation given the factors present, but still adopt it (e.g. Mexico), and focusing on the relationship between economic and environmental factors and the levels they originated from may explain why they, rather than more likely cases, have adopted such taxation. The emphasis on relationships between factors leads us to draw on the Advocacy Coalition Framework (Jenkins-Smith et al. Citation2014), particularly the relationships between the economic and environmental policy subsystems, including cross-cutting coalitions.

We find that the adoption of the Mexican carbon tax was driven by synergies between economic and environmental factors: the idea that the carbon tax was an environmentally friendly and economically rational policy instrument stemmed from the international level and allowed for a coalition spanning the Ministries of Environment and Finance, the latter also motivated by the fiscal benefits of the tax. This coalition got the carbon tax adopted as part of the fiscal reform following Enrique Penã Nieto becoming President in 2012. Opposition industry groups and carbon-intense regions could not block the tax due to the all-encompassing nature of the fiscal reform (Hernández Gutíerrez Citation2020) and its environmental benefits, but managed to lower its rate and exempt natural gas.

Studying the adoption of the Mexican carbon tax contributes to the academic literature in two ways. First, we contribute to the literature on carbon taxes and pricing by identifying the factors driving a critical case of carbon tax adoption. We go further than existing literature by exploring the relationships between economic and environmental factors and which level they originate from. The findings are instructive for the study of other carbon taxes, especially within the cluster of emerging and developing countries that have adopted carbon taxes since 2013 (most with tax rates comparable to Mexico’s) (Skovgaard, Sacks Ferrari, and Knaggård Citation2019). Especially in carbon-intense countries within this cluster, such as Argentina, Colombia and South Africa, a focus on the relationships between international and national, economic and environmental factors may explain why they have adopted such taxation. Second, we contribute to the literature on the relationship between economic and environmental factors, by exploring whether they are synergistic or conflictual. The role of this relationship is pronounced in the case of carbon taxes, since such taxes as environmental policy instruments are strongly rooted in both economic and environmental paradigms (cf. Pigou Citation1932), but also constitute fiscal policy instruments with the portfolios of finance ministries and can affect industrial competitiveness.

The paper proceeds with a discussion of the literature examining carbon taxes and their adoption. The subsequent section outlines our analytical framework, which focuses on the relationships between economic and environmental factors, coalitions and framing, and whether they originate on the international or national level. The following section describes the qualitative methods and materials used when applying this framework to the Mexican carbon tax. The analysis constitutes the ensuing section, in which we find that the adoption of Mexican carbon tax was driven by a combination of the idea of carbon taxation from the international level, the 2013 fiscal reform, and the prevailing synergistic relationship between climate mitigation and the economic objectives of economic rationality and fiscal benefits. The conclusion discusses the findings and future research studying other cases of adoption of carbon taxes or other environmental policy instruments.

2. Carbon taxes—an economic instrument addressing climate change

The notion of addressing climate change through a tax is rooted in the idea that externalities stemming from an activity should be internalized by imposing a tax corresponding to the social costs (Pigou Citation1932). According to this view, fundamental to mainstream environmental economics (Katz-Rosene and Paterson Citation2018), climate change constitutes a global externality that is optimally addressed by a global carbon tax set at a level corresponding to the costs of climate change (Nordhaus Citation2019). Taxing fuels on the basis of their carbon content, i.e. climate impact, allows for framing carbon taxes as both economically rational and environmentally beneficial. Economists have promoted carbon taxes and carbon pricing in general. Since a global carbon tax has not been politically possible, the adoption of carbon taxes (and emissions trading systems) has been decided on the level of countries as well as subnational (e.g. US states) entities. Carbon taxes were first adopted in Nordic countries in the early Nineties, spreading to other countries in Europe (e.g. France) and Latin America (e.g. Mexico) as well as substate entities, e.g. British Colombia (Andersen Citation2019; Skovgaard, Sacks Ferrari, and Knaggård Citation2019). Importantly, not all environmentalists are in favor of carbon taxes and carbon pricing: several scholars have argued it constitutes symbolic policy that often prevents structural reform (Green Citation2021).

The existing literature has found that economic and environmental factors are very important for the adoption of carbon taxes (Harrison Citation2010; Rabe Citation2018; Andersen Citation2019; Steinebach, Fernández-I-Marín, and Aschenbrenner Citation2020; Stevens Citation2021; see also Best and Zhang Citation2020; Levi, Flachsland, and Jakob Citation2020; Dibley and Garcia-Miron Citation2020; Ryan and Micozzi Citation2021). According to this literature, some economic factors hinder the adoption of carbon taxes (industry interest groups and labor unions from carbon intense sectors, competitiveness concerns, especially if trading partners do not have similar taxes), whereas others promote them (fiscal concerns, level of income). Likewise, some environmental factors, including international climate commitments and earmarking of revenue for environmental purposes, encourage the adoption of carbon taxes (Steinebach, Fernández-I-Marín, and Aschenbrenner Citation2020; Bachus, Van Ootegem, and Verhofstadt Citation2019). Beyond economic and environmental factors, scholars have also identified factors such as International Organizations (Harrison Citation2010), left-wing government orientation (Skovgaard, Sacks Ferrari, and Knaggård Citation2019), proportional representation and neo-corporatist institutions (Andersen Citation2019), presidential systems (Stevens Citation2021), confidence in government (Criqui, Jaccard, and Sterner Citation2019) and the agency of entrepreneurs as being conducive to the adoption of carbon taxes (Harrison Citation2010; Rabe Citation2018; Ryan and Micozzi Citation2021). Scholars have also found that good governance and awareness of climate change are conducive to higher carbon prices (Levi, Flachsland, and Jakob Citation2020), whereas fossil fuel dependence leads to lower prices (see Levi, Flachsland, and Jakob Citation2020; MacNeil Citation2016).

3. Analytical framework: economic-environmental relations and levels

The framework employed here for carbon tax draws on literature on economic-environmental relations and policy process literature, especially the Advocacy Coalition Framework (Jenkins-Smith et al. Citation2014), focusing on explaining policy adoption understood as a subtype of policy change. Explaining why a policy instrument, in this case a carbon tax, was adopted, it is “important to study (1) the role of policy actors in the decision-making process and (2) their policy preferences” (Kammerer et al. Citation2020, 241).

The economic and environmental factors identified by the carbon pricing literature vary in kind. Some of them consist of agency of e.g. interest groups or entrepreneurs, others of structural factors such as competition from abroad, and others again of beliefs (see e.g. Harrison Citation2010; Steinebach, Fernández-I-Marín, and Aschenbrenner Citation2020). To study this diverse set of factors, we draw on the Advocacy Coalition Framework (Jenkins-Smith et al. Citation2014) and organize the factors according to which policy subsystem they influence. Focusing on policy subsystems allows for studying how the relationship between different factors translated into relations between actors in different subsystems, including coalitions, and their policy core ideas, and shaped the adoption of the carbon tax.

The policy subsystem is defined by the policy topic, territorial scope and the actors affecting policy subsystem affairs (Jenkins-Smith et al. Citation2014: 189–191). Within policy subsystems, actors can be organized into advocacy coalitions on the basis of shared policy core ideas (or beliefs) and strategies (Jenkins-Smith et al. Citation2014, 191). The policy core ideas can be normative (reflecting the orientation and priorities of actors within the subsystem and including objectives and preferences) and empirical (concerning the seriousness of a given problem, its causes and solutions (Jenkins-Smith et al. 2014). We argue that within policy subsystems the policy core ideas generally concern how to address the policy topic, and may be framed as synergetic or conflictual. Policy subsystems can be nested within other policy subsystems, and often overlap regarding particular issues. Such overlap may lead to coalitions of actors forming across subsystems.

All policy subsystems involved in the policy process leading to the adoption of the Mexican carbon tax have a territorial scope covering all of Mexico, but may be affected by international factors, as discussed below. The economic policy subsystem is characterized by addressing economic topics, involving economic actors (in Mexico particularly the Ministry of Finance, business and their interest groups) and economic policy core ideas. These policy core ideas include normative ones, such as pursuing growth and good fiscal balances as objectives, and empirical ideas, such as the belief that economically rational and market-based solutions are optimal for addressing policy problems.

Likewise, the environmental policy subsystem is characterized by addressing environmental issues, involving environmental actors (in Mexico, particularly the Ministry of Environment) and policy core ideas, such as the normative idea of the objective of reducing Mexican emissions. Factors exist which concern neither the economic nor the environmental policy subsystem but constitute external events, including changes in other policy subsystems, such as health or energy,Footnote2 or public opinion or system-wide governing coalitions (Jenkins-Smith et al. Citation2014, 194). We expect environmental and economic factors to constitute the most important factors regarding the adoption of carbon pricing. The relationship between economic and environmental factors is particularly salient regarding carbon taxes, which simultaneously constitute an instrument of environmental and fiscal policy.

Neither environmental nor economic factors pull in one sole direction. Within each policy subsystem there are nested subsystems, e.g. the fiscal policy or industrial policy subsystems in the case of the economy policy subsystem; or climate change and biodiversity in the case of the environmental policy subsystem. The policy core ideas of coalitions within one nested subsystem are not necessarily synergistic with the policy core ideas of coalitions within another nested subsystem of the same policy subsystem. For instance, a policy may mitigate climate change but be detrimental to other environmental objectives such as biodiversity (e.g. first-generation biofuels); and be beneficial to public budgets but detrimental to carbon-intense industries (e.g. carbon pricing; Skovgaard, Sacks Ferrari, and Knaggård Citation2019). While not all environmentalists are in favor of carbon taxes, we expect that they will not oppose such a proposal. Our focus on to what degree policy core ideas are synergistic or conflictual differs from the related literature on co-benefits (see Karlsson, Alfredsson, and Westling Citation2020 for an overview of this literature) in focusing on negative as well as positive relations between policy core ideas.

Furthermore, the literature on the relationship between environmental and economic policy core ideas often defines them as competing, with inevitable tradeoffs between them (Hoffman and Ventresca Citation1999). While economic core ideas usually receive top priority, policy-making addressing environmental core ideas is enhanced when the relationship with economic core ideas is framed as synergetic (Jacobs Citation2012; Skovgaard Citation2014).

Hence, cross-cutting alliances between actors from the economic and environmental policy subsystems are enhanced if a policy proposal is framed as being synergistic with their respective policy core ideas (on actors using policy framing to get policy proposals adopted or rejected, see Schön and Rein Citation1994). Since Mexico has politically influential emission-intense industries, but also a powerful Ministry of Finance (Stevens Citation2021; Mayer-Serra Citation2017; Dibley and Garcia-Miron Citation2020), there is reason to expect that economic factors pulled in both directions. How the economic and environmental factors affected the adoption the carbon tax thus depends on how actors framed the idea of carbon pricing in relation to core policy ideas (e.g. from particular nested policy subsystems). Other strategies, such as agenda-setting, may also play a role, as may previously mentioned external events.

Altogether, we expect that while neither economic nor environmental factors on their own can explain the adoption of the carbon tax, synergies between them were crucial for the adoption of the Mexican carbon tax. We also expect framing of the economic-environmental relations to be an important strategy.

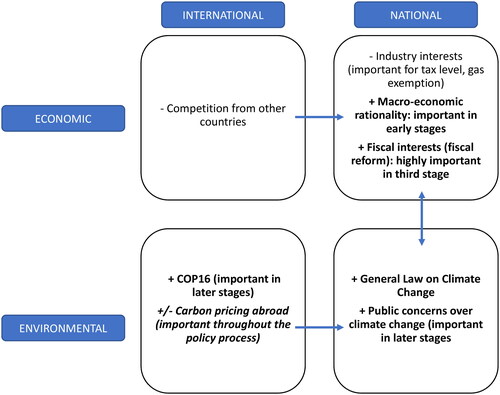

Beyond the role and relationship between economic and environmental factors, we study whether these factors are international or national in origin, since international and national factors are expected to have different kinds of impacts (Marsh and Sharman Citation2009). In this paper, we are mainly interested in international and national factors that affect the economic and environmental subsystems (see ). International factors cover factors originating outside the country, including international institutions and other countries. National factors include influences originating within economic and environmental subsystems, but also national external events. There may be considerable interaction between international and national factors, e.g. competition from industry in countries without carbon taxes leading to the mobilization of domestic industry groups. The carbon pricing literature outlined above has identified international factors such as international institutions, competition and learning, as well as national ones such as public concerns over climate change, as important to the adoption of carbon taxes.

Table 1. Potential international and national, economic and environmental factors.

In the case of Mexico, we expect international environmental factors such as the UNFCCC, international economic factors such as competition from the other NAFTA countries not subject to carbon pricing, as well as national economic factors such as fiscal concerns and industry interest groups to play important roles. While we treat competition from abroad as an international factor, it also influences policy-making by mobilizing industry interest groups.

National environmental factors such as public concern over climate change or existing climate legislation have not figured prominently on the political agenda in Mexico, during the period studied. Hence, we do not expect them to play substantive roles.

4. Methods and sources

The analysis relies on a causal process tracing of the policy processes leading to the adoption of the Mexican carbon tax. We employ causal process tracing because it allows us to study the causal configurations in the shape of interaction between factors and provides a narrative “with a dense storyline, deep insights into the structures and motivations of (…) actors and a fine-grained picture of the critical moments in which various factors came together to produce an important outcome” (Blatter and Blume Citation2008: 323–324). This approach allows for drawing inferences from the causal interaction between economic and environmental, international and national factors in the case of the Mexican carbon tax to the wider set of cases of environmental policy adoption in which similar interactions between these factors have been at play. Similar tracing of the policy processes has been applied to other cases of policy adoption, including on the adoption of carbon taxes (Stevens Citation2021; Karapin Citation2020).

The process tracing is based on interviews and written sources. Regarding the former, 12 interviews were carried out with officials from the Ministries of Environment and Finance; experts from independent think tanks, civil society organizations and international organizations; representatives of industry associations; and political aides to members of the budget and environmental affairs committees of the two chambers of the Mexican Congress. As by their recognition, there is a small group of people involved in the adoption of the Mexican carbon tax of which we managed to interview a great majority, especially civil servants and policy experts, following a snowball approach. Although reaching policy-makers was more difficult, we interviewed their aides and assessed their positions in transcribed congressional sessions. The interviews were carried out in Mexico City 6–17 May 2019, and in some cases over Skype and telephone. The interviews were semi-structured and based on questions concerning the role of the informant and other key actors in the policy process: development of the policy process; the motivations of actors; and key turning points. The transcribed interviews were coded to map the policy process and identify different objectives and strategies and the extent to which their influences were international or national, environmental or economic. The written sources consist of primary sources from the Ministries of Finance and the Environment, the Mexican Congress, and non-governmental actors, including declarations, reports, opinions and transcripts of congressional debates. Finally, secondary sources, particularly academic publications and newspaper articles, have been utilized to triangulate our findings and shed light on developments not covered by the interviews or the primary sources. When using interviews to trace policy processes that began more than two decades ago, there is a risk that the informants interpret past events, strategies, and preferences in the light of current developments. Therefore, triangulating interviews with each other and with written sources was highly important, considering how many and how centrally placed informants support a given version of events. There has been a very high degree of consistency between the interviews, especially when it comes to the key actors, entrepreneurs, and events of the policy process, as well as between their recall of events and their portrayal in press archives and transcribed congressional sessions.

5. Mexican climate policy

Mexico is characterized by increasing emissions, a fossil fuel dependent energy system, an emissions-intensive industry, particularly a politically influential oil sector, in which the state-owned PEMEX is the largest company and provides a third of the federal government’s revenue (Rosas-Flores Citation2017; Simon, Naegler, and Gils Citation2018). Despite a lack of international commitments until 2015 and an overall insufficient level of environmental governance (Climate Action Tracker Citation2021), successive Mexican governments have committed to climate change policies (Veysey et al. Citation2016). In 2010, Mexico committed to voluntary reduction targets following the Cancun Climate Change Conference. The cornerstone of Mexican climate policy is the General Law on Climate Change (GLCC), adopted in 2012. The GLCC established a National Climate Change System, that operationalized the goal of 50 percent reduction in emissions compared to 2,000 levels by 2050 (Gobierno Federal de Mexico Citation2013; Silva Rodríguez de San Miguel Citation2018).

The National Climate Change System established three specific economic instruments: first, the reform of an existing fossil fuel subsidy; second, a carbon market that would enter a pilot phase in 2020; and third, the carbon tax (Arlinghaus and van Dender Citation2017; ICAP Citation2019). The subsidy reform was part of an energy system reform and removed a mechanism stabilizing domestic prices of fuels by lowering a tax or subsidizing the fuel when international prices went up, and vice versa when they went down (Silva Rodriguez de San Miguel Citation2018; COFECE Citation2019).

Regarding the carbon tax, environmental economists and environmental policy experts have—inspired by international discussions—debated such a tax as early as the 1990s, including its design (i.e. whether a carbon tax or an emissions trading system was preferable), and the possibilities for adoption.Footnote3 These experts were mainly environmental economists from academia, the Ministry of Environment and think tanks such as Centro Mario Molina, a highly influential and unaffiliated (in party terms) institution.

The increasing interest in a carbon tax became particularly relevant in the context of major structural reforms supported by all major political parties under an agreement called ‘Pacto por Mexico’, proposed by the incoming government of Enrique Peña Nieto from the centrist Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) (Barrientos del Monte and Añorve Añorve Citation2014). The ‘Pacto por Mexico’ was a reform coalition consisting of the political leaders of the three main parties, which would benefit the government and the opposition centre-right Partido Acción Nacional (PAN) by allowing them to pass reforms the latter had been unable to adopt in their past (2000–2012) governments due to PRI opposition. Fearing the alliance between PAN and PRI would give the government a majority to pass almost any reform project, the left-wing Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD) decided to join as well (Mayer-Serra Citation2017). The agreement consisted of 95 agreements ranging from democratic governance to competitiveness.

One reform was a comprehensive fiscal restructuring (taking place within the fiscal policy subsystem), which aimed at making the tax system more efficient, increasing tax revenue corresponding to 1% of GDP, and granting more autonomy and authority to subnational entities in collection (Cárdenas Sánchez Citation2018). Within the fiscal reform proposed in 2013, the carbon tax was included as an amendment to a special tax, which also included taxes on tobacco, alcoholic beverages, sodas and pesticides (Diario Oficial de la Federación de Estados Mexicanos Citation2017).

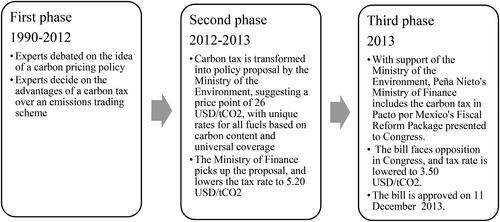

The external event of the Pacto por Mexico and the resulting processes within the fiscal subsystem led to a second phase in the adoption of the carbon tax. Starting in 2012, a coalition of officials from the Ministry of Environment and experts from Centro Mario Molina turned the idea of a Mexican carbon tax into a policy proposal and promoted it to the Ministry of Finance in 2013. The proposal was revised several times, and the proposed tax level was lowered from around 26 dollars to 5.70 dollars per ton due to insistence from the Ministry of Finance.Footnote4 The tax would include all fossil fuels and price them at a rate per unit equivalent to the carbon they contained (Presidencia de la República de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos Citation2013). But unlike other components of the Pacto por Mexico reforms, that had been drafted and discussed by the three parties’ leaderships before hand to ensure they had multi-partisan support and would be approved (Mayer-Serra Citation2017), this bill was met with opposition by the PAN (Garduno and Méndez Citation2013). During the third legislative phase of the process, legislators from the regions of the North characterized by oil production and carbon-intense industry exports to the US sought support from industrial and agricultural associations, fossil fuel producers, the Council of Enterprises, and CESPEDES, the coordinating body for different Mexican business’ sustainable development initiatives. In an open consultation process by the lower chamber’s Treasury Commission, which handles budgetary issues, this coalition argued that the tax would harm the competitiveness of national energy sources; disproportionately impact the country’s poorest; and overall, not reduce emissions substantively (CESPEDES Citation2013). Instead, they argued for a carbon market. Nevertheless, the broad scope of the tax reform limited the possibility for lobbying: such a high number of organizations attempted to get legislators’ attention that the legislators could only meet with each group of lobbyists for twenty minutes within a four day period (Hernández Gutíerrez Citation2020).

The lobby attempts were partially successful: while the large congressional majority of Peña Nieto’s political coalition had guaranteed all other parts of the reform to be passed practically unchallenged, the discussions in the lower and upper chambers’ fiscal committees meant that the carbon tax’s rate was lowered and subjected to different rates per carbon unit for each fuel type, de facto exempting natural gas. These amendments guaranteed the tax’s passage by securing large majorities in both the upper and lower chamber, yet was still opposed by PAN legislators from northern states (Senado de la República de México Citation2013). The process is summarized in .

Starting in 2014, all fossil fuels (except natural gas) have been subject to a carbon tax of around US$3.50 per tCO2 with some variation based on carbon content (Arlinghaus and van Dender Citation2017). The Ministry of the Environment has estimated that the policy has led to an abatement of 1.8 million tCO2-equivalent (MEXICO2, Environmental Defense Fund, and IETA Citation2018). In 2019, total revenue from the tax was over 275 million USD; around 0.2 per cent of federal government revenue (Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público Citation2020).

6. Explaining the adoption of the carbon tax

In the first two stages of the policy process, international environmental factors were particularly important. Both the idea that it was appropriate for Mexico to act on climate change, and the idea that carbon pricing constitutes an efficient climate policy instrument came from abroad and had climate protection as its main objective. The latter idea also had a strong economic component, since the objective was to have a climate policy that mitigated climate change at the lowest possible cost, and carbon pricing being based on the notion of climate change constituting an externality (SEMARNAT Citation2014). In these first stages of the policy process, the framing of the carbon tax as an economic as well as an environmental issue by experts from the Centro Mario Molina was important in convincing particularly economists (notably from the Ministry of Finance in the second stage) of the desirability of carbon taxation. This framing entailed defining the carbon tax as environmentally and fiscally beneficial and consistent with economic policy core ideas. The fiscal benefits mattered greatly to the Ministry of Finance officials.Footnote5 Similarly, Ministry of Environment officials were motivated by the hope that carbon tax revenue would be earmarked for environmental projects under its portfolio.Footnote6 Yet, the actors skeptical of carbon tax were worried about the economic impact to the competitiveness of the Mexican industry,Footnote7 but given the (at the time rather recent) public support for the idea that Mexico should mitigate climate change, they could not outright argue against the tax. Rather they argued for lowering it and exempting natural gas (both proposals largely successful) and for recycling revenue to the sectors targeted and the possibility for using carbon credits to meet their tax obligations (both proposals unsuccessful).

The coalition in favor of the tax gradually expanded from a limited circle of experts (in the first stage) over the Ministry of Finance (in the second) and politicians, especially from PRI (in the third). Winning over the Ministry of Finance was a turning point,Footnote8 a piece of coalition-building spanning the economic and environmental policy subsystems based on the mentioned economic and environmental framing of the tax. The coalition building between the Ministries of Environment and Finance were also aided by personal contacts and shared understandings between powerful officials, who inter alia knew each other from having attended the same Masters’ programmes at American universities; programmes which included classes in environmental economics.Footnote9 The latter enhanced the resonance of the framing of the tax as economically rational among them.

In the third phase of the policy process, the most important factors were economic, particularly the fiscal reform package adopted following the 2012 election of Peña Nieto as President. Our informants all underscore the importance of the fiscal reform package to the adoption of the carbon tax; had the carbon tax been negotiated on its own, it is uncertain whether it would have been adopted. The framing of the tax as environmentally and economically beneficial also meant that it was possible to first place the tax on the agenda of the Ministry of Finance. Being on the agenda of the Ministry of Finance was an important condition for the subsequent inclusion of the tax in the fiscal reform package, and consequently also for the pro-tax coalition placing it on the agenda of fiscal and environmental protection committees of the Mexican Chamber of Deputies and Senate. This strategy meant it would progress through the Congressional process as part of the package, and it would be difficult for opponents to vote against the tax without rejecting more widely supported parts of the package, such as taxes on carbonated sodas and junk food.Footnote10

Furthermore, the carbon tax being addressed by actors from the fiscal policy subsystem increased the possibilities for its adoption. Environmental policy subsystem actors had less power to overcome opposition from other actors than the fiscal policy actors. The coalition opposed to the carbon tax (formed in response to the proposal) was united by opposition to the consequences to industry. These actors were able to build a strong coalition across a variety of business associations (part of the industrial policy subsystem) that lobbied the lower chamber’s Treasury Commission, opposing the raising of production taxes in general, and the carbon tax, in particular, by arguing it would be incompatible with the carbon market proposed in the National Law of Climate Change and with Mexican competitiveness. The argument of the carbon tax being detrimental to competitiveness was important for the lowering of the tax rate and the exemption of natural gas, which was framed as a cleaner alternative to oil and coal.

The inclusion of the tax in the fiscal reform package also meant limited public attention and time to mobilize the public against the tax. In this stage, the carbon tax was framed to the public as an instrument addressing climate change rather than raising revenue, since environmental protection was more popular than ‘taking people’s money’.Footnote11 The environmental framing also made it difficult for opponents from the industrial policy subsystem to reject the tax outright. Instead, they focused on diminishing the costs to industry,Footnote12 arguing first that the tax would not embody the ‘polluter pays’ principle, since there was not a clean energy market in Mexico allowing actors to choose not to pollute; and second, that a general tax would neither guarantee reduced emissions nor foster investment in sustainable alternatives, as regulatory policies promoting low-carbon technologies would (CESPEDES Citation2013). This strategy was also important in lowering the tax rate and exempting natural gas.Footnote13

Altogether, the environmental factors worked in favor of the adoption of the tax, while economic factors worked both in favor of and against it; and without framing of the tax in terms of synergies between economic (specifically fiscal and economic rationality) and environmental policy core ideas, the tax would not have been adopted.

Regarding international and national factors, international ones (especially the idea of carbon taxation) were most important in the early stages, and national ones (especially the fiscal reform) in the last stage. Concerning the international level, the idea of having a carbon tax was introduced to Mexico from abroad through academic channels and gained a foothold among the abovementioned environmental economists. It was further supported by international actors such as the OECD and the World Bank, which provided funding for workshops on carbon pricing. Beyond the introduction of the idea of carbon pricing, the hosting of COP16 in 2010 was crucial in broader circles of policy-makers and the public in increasing awareness of climate change, as well as introducing the idea that Mexico had a responsibility to mitigate climate change. This change is evident in the 2012 General Law on Climate Change. Regarding the national level, the external events of the election of Peña Nieto and the Pacto por Mexico, and the economic factor of fiscal reform were by far the most important. Mexico had no previous experience of environmental taxation to learn from, and although increasing domestic willingness to address climate change strengthened environmental subsystem actors, the increasing willingness was spurred by international influences such as COP16.Footnote14

Thus, national economic factors worked both in favor of and against the adoption (with fiscal benefits being more influential than costs to industry), while international economic factors (competitiveness) worked against it, but was nowhere as influential, and interacted with domestic economic policy core ideas emphasizing industrial competitiveness. Environmental factors played consistent roles irrespective of their origin (see ).

Experiences from the international level were utilized by both those in favor and opposed to carbon pricing. Those in favor referred to the experiences of other countries with carbon pricing, including how they have designed carbon taxes and pointed to their successful implementation.Footnote15 Particularly, parliamentarians from the UK were brought in to share their experience with a climate change law and carbon taxation with Mexican peers. Furthermore, the US$5.70 rate was proposed based on it being the current carbon price in the EU emissions trading system.Footnote16 Those skeptical of the carbon tax referenced the failed experiences in Australia and the US, and argued that other carbon pricing policies tended to be financially neutral for the sectors regulated, in the sense that the revenue was recycled to the sectors, or that it was possible to offset the tax by submitting carbon credits in lieu of paying the tax.Footnote17 Thus, actors skeptical of the tax proposed submitting credits corresponding to one tCO2 for each tCO2 emitted (instead of paying the tax), the price of such credits at US$0.15 per tCO2 being a fraction of both the proposed and adopted tax rates. Yet, these proposals failed. Finally, the external events of the election of Peña Nieto leading to the Pacto por Mexico empowered the coalition in favor of the tax to a degree that the coalition against the tax could not prevent its adoption. Importantly, these events could only be utilized in favor of the tax because the Ministry of Finance had earlier been convinced about the economic merits of the tax.

7. Conclusion

The Mexican carbon tax was the first one adopted by a developing country. Mexico is an emissions-intense economy exposed to competition from countries without carbon taxes, and did not have international commitments to mitigate climate change or powerful pro-climate actors at the time of adoption. The combination of these factors is expected to be detrimental to the adoption of a carbon tax. Yet, we started from the assumption that the relationship between economic and environmental factors, and their level of origin, could explain this adoption. Our analysis proved that assumption to be largely right. More specifically, it found that the policy process started with the notion of a carbon tax being introduced from abroad, then promoted to a growing range of actors, most notably the Ministry of Finance, and finally in 2013 it was adopted as part of the fiscal reform. Environmental factors, understood as factors influencing the environmental policy subsystem, worked in favor of the tax, while economic factors, or factors influencing the economic policy subsystem, worked both in favor (the notion it was economically rational, fiscal preferences) and against it (competitiveness preferences). Thus, our expectations were largely met: First, economic and environmental factors were the most important sets of factors, but could not explain the adoption on their own. Second, without the coalition between actors from the fiscal and environmental policy subsystems based on the framing of the tax as synergetic with policy core ideas from both subsystems, the tax would not have been adopted.

Third, international environmental factors and national economic factors played important roles. Regarding the latter, national economic factors in favor of the tax were most influential, although the factors detrimental to it lowered the tax rate and exempted natural gas. International environmental factors were especially important in the first two stages, when they were conducive to the adoption of the tax. Later, national economic (fiscal reform) factors and external events (the election of Peña Nieto) changed the relative power of actors in favor of the pro-carbon tax coalition and against the anti-tax coalition.

Finally, national environmental factors played a larger role than expected.

These findings contribute to the academic literature in two ways. First, the analysis contributes to the carbon pricing literature by underscoring the importance of framing in terms of synergistic relations between economic and environmental factors, and to some degree also the level of origin. Future research could explore whether relationships between economic and environmental factors were important to the adoption of carbon pricing in countries such as Argentina, Colombia, and South Africa. Second, the finding that the fiscal policy subsystem was in favor and large parts of the industry policy subsystem was against the tax contributes to the literature on the relationship between economic and environmental factors, particularly which factors shape coalitions across policy subsystems. These findings underscore that economic factors do not unequivocally pull in favor of or against adoption of environmental policy. Future research could explore the role of framing for the relationship between different economic and environmental factors, e.g. whether synergistic framing is a condition for coalitions across economic and environmental subsystems, particularly involving nested subsystems, in the adoption of environmental policies.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interests.

Notes

1 And the second carbon pricing policy after the Kazak emissions trading scheme.

2 The policy core ideas of energy policy are typically defined as energy equity (affordable energy), security and sustainability (Sanderink, Pattberg, and Widerberg Citation2020). Given that sustainability is an inherently environmental policy core idea, access to affordable energy overlaps with economic policy core ideas, and energy security was not relevant to the carbon tax; we find focusing on economic-environmental relations more relevant.

3 Interview 1

4 Interview 2

5 Interview 3

6 Interview 4; Interview 5

7 Interview 6

8 Interview 4

9 Interview 2; Interview 5

10 BBC Mundo. n.d. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/ultimas_noticias/2013/11/131031_ultnot_mexico_impuesto_comida_chatarra_jgc.

11 Interview 3

12 Interview 6

13 Interview 3

14 Interview 4

15 Interview 1; Interview 4

16 Interview 1

17 Interview 6

References

- Aldy, J., and R. Stavins. 2012. “The Promise and Problems of Pricing Carbon.” The Journal of Environment & Development 21 (2): 152–180. doi:10.1177/1070496512442508.

- Andersen, M. 2019. “The Politics of Carbon Taxation: How Varieties of Policy Style Matter.” Environmental Politics 28 (6): 1084–1104. doi:10.1080/09644016.2019.1625134.

- Arlinghaus, J., and K. van Dender. 2017. The Environmental Tax and Subsidy Reform in Mexico. OECD Taxation Working Papers. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/a9204f40-en.pdf?expires=1592251162&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=0A6847DD2977D1C3187ED0820C40274D

- Bachus, K., L. Van Ootegem, and E. Verhofstadt. 2019. “‘No Taxation without Hypothecation’: Towards an Improved Understanding of the Acceptability of an Environmental Tax Reform.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (4): 321–332. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2019.1623654.

- Barrientos del Monte, F., and D. Añorve Añorve. 2014. “México 2013: Acuerdos, Reformas y Descontento.” Revista de Ciencia Política (Santiago) 34 (1): 221–247. doi:10.4067/S0718-090X2014000100011.

- Best, R., and Q. Zhang. 2020. “What Explains Carbon-Pricing Variation between Countries?” Energy Policy 143: 111541. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111541.

- Blatter, J., and T. Blume. 2008. “In Search of Co-Variance, Causal Mechanisms or Congruence? Towards a Plural Understanding of Case Studies.” Swiss Political Science Review 14 (2): 315–356. doi:10.1002/j.1662-6370.2008.tb00105.x.

- Cárdenas Sánchez, E. 2018. “Política Hacendaria En México de 2013 a 2017. Una Primera Aproximación Al Sexenio.” El Trimestre Económico 85 (340): 887. doi:10.20430/ete.v85i340.764.

- CESPEDES 2013. Propuesta Al Impuesto Al Carbono: Notas Para El Posicionamiento de CESPEDES. http://www.cespedes.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Impuesto-al-carbono-extenso.pdf.

- Climate Action Tracker. 2021. Countries Rating System: Mexico. https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/mexico/.

- COFECE. 2019. Transición Hacia Mercados Competidos de Energía: Gasolina y Diésel. Mexico City. https://www.cofece.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/CPC-GasolinasyDiesel-30012019.pdf.

- Criqui, P., M. Jaccard, and T. Sterner. 2019. “Carbon Taxation: A Tale of Three Countries.” Sustainability 11 (22): 6280. doi:10.3390/su11226280.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación de Estados Mexicanos. 2017. Ley de Impuesto Especial Sobre Producción y Servicios. Ciudad de México. https://www.sep.gob.mx/work/models/sep1/Resource/17e0fb21-14e1-4354-866e-6b13414e2e80/ley_impuesto_especial.pdf.

- Dibley, A., and R. Garcia-Miron. 2020. “Can Money Buy You (Climate) Happiness? Economic Co-Benefits and the Implementation of Effective Carbon Pricing Policies in Mexico.” Energy Research & Social Science 70: 101659. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101659.

- Garduno, R., and E. Méndez. 2013. La Reforma Fiscal de Peña Recibió 317 Votos a Favor y 164 En Contra. La Jornada. October 18.

- Gobierno Federal de Mexico. 2013. Estrategia Nacional de Cambio Climático. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/41978/Estrategia-Nacional-Cambio-Climatico-2013.pdf.

- Green, J. 2021. “Does Carbon Pricing Reduce Emissions? A Review of Ex-Post Analyses.” Environmental Research Letters 16 (4): 043004. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abdae9.

- Harrison, K. 2010. “The Comparative Politics of Carbon Taxation.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 6 (1): 507–529. doi:10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.093008.131545.

- Harrison, K., and L. Sundstrom. 2007. “The Comparative Politics of Climate Change.” Global Environmental Politics 7 (4): 1–18. doi:10.1162/glep.2007.7.4.1.

- Hernández Gutíerrez, L. 2020. “Cabildeo de Los Grupos Empresariales En El Congreso Mexicano: LXII Legislatura.” Estudios: Filosofía, Historia, Letras 18 (135): 55–87.

- Hoffman, A., and M. Ventresca. 1999. “The Institutional Framing of Policy Debates.” American Behavioral Scientist 42 (8): 1368–1392. doi:10.1177/00027649921954903.

- ICAP. 2019. ETS Detailed Information: Mexico. https://icapcarbonaction.com/en/?option=com_etsmap&task=export&format=pdf&layout=list&systems[]=59.

- Jacobs, M. 2012. Green Growth: Economic Theory and Political Discourse. GRI Working Papers 92. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

- Jenkins-Smith, H., D. Nohrstedt, C. Weible, and P. Sabatier. 2014. “Advocacy Coalition Framework: Foundations, Evolution, and Ongoing Research.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by P. Sabatier and C. M. Weible. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Kammerer, M., K. Ingold, and J. Dupois. 2020. “Switzerland: International Commitments and Domestic Drawbacks.” In Climate Governance Across the Globe: Pioneers, Leaders, and Followers, edited by R. Wurzel, M.S. Andersen, and P. Tobin, Paul. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Karapin, R. 2020. “The Political Viability of Carbon Pricing: Policy Design and Framing in British Columbia and California.” Review of Policy Research 37 (2): 140–173. doi:10.1111/ropr.12373.

- Karlsson, M., E. Alfredsson, and N. Westling. 2020. “Climate Policy Co-Benefits: A Review.” Climate Policy 20 (3): 292–316. doi:10.1080/14693062.2020.1724070.

- Katz-Rosene, R., and M. Paterson. 2018. Thinking Ecologically about the Global Political Economy. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Keohane, R., and J. Victor. 2016. “Cooperation and Discord in Global Climate Policy.” Nature Climate Change 6 (6): 570–575. doi:10.1038/nclimate2937.

- Lachapelle, E., and M. Paterson. 2013. “Drivers of National Climate Policy.” Climate Policy 13 (5): 547–571. doi:10.1080/14693062.2013.811333.

- Levi, S., C. Flachsland, and M. Jakob. 2020. “Political Economy Determinants of Carbon Pricing.” Global Environmental Politics 20 (2): 128–156. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00549.

- MacNeil, R. 2016. “Death and Environmental Taxes: Why Market Environmentalism Fails in Liberal Market Economies.” Global Environmental Politics 16 (1): 21–37. doi:10.1162/GLEP_a_00336.

- Marsh, D., and J. Sharman. 2009. “Policy Diffusion and Policy Transfer.” Policy Studies 30 (3): 269–288. doi:10.1080/01442870902863851.

- Mayer-Serra, C. 2017. “Reforma de La Constitución: La Economía Política Del Pacto Por México.” Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales 62 (230): 21–49. doi:10.1016/S0185-1918(17)30016-8.

- MEXICO2, Environmental Defense Fund, & IETA. 2018. MEXICO: A Market Based Climate Policy Case Study. www.mexico2.com.mx%7Cwww.edf.org%7Cwww.ieta.org.

- Mildenberger, M. 2020. Carbon Captured: How Business and Labor Control Climate Politics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Nordhaus, W. D. 2019. “Climate Change: The Ultimate Challenge for Economics.” American Economic Review 109 (6): 1991–2014. doi:10.1257/aer.109.6.1991.

- OECD. 2019. OECD Economic Surveys: Mexico 2019. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/a536d00e-en.

- Paterson, M., M. Hoffmann, M. Betsill, and S. Bernstein. 2014. “The Micro Foundations of Policy Diffusion toward Complex Global Governance: An Analysis of the Transnational Carbon Emission Trading Network.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (3): 420–449. doi:10.1177/0010414013509575.

- Pigou, A. 1932. The Economics of Welfare. London: Macmillan.

- Pizarro, R. 2021. Sistemas de instrumentos de fijación de precios del carbono en América Latina y jurisdicciones de las Américas relevantes. Santiago: ECLAC. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/46765/4/S2100035_es.pdf.

- Presidencia de la República de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. 2013. Iniciativa Por El Que Se Reforman, Adicionan y Derogan Disposiciones de La Ley Del Impuesto Al Valor Agregado, de La Ley Del Impuesto Especial Sobre Producción y Servicios y Del Código Fiscal de La Federación. Cámara de Diputados de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. http://www.diputados.gob.mx/PEF2014/ingresos/03_liva.pdf.

- Rabe, B. 2018. Can We Price Carbon? Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ramírez Sánchez, J., C. Calderón, and S. Sánchez León. 2018. “Is NAFTA Really Advantageous for Mexico?” The International Trade Journal 32 (1): 21–42. doi:10.1080/08853908.2017.1387623.

- Rosas-Flores, J. 2017. “Elements for the Development of Public Policies in the Residential Sector of Mexico Based in the Energy Reform and the Energy Transition Law.” Energy Policy 104: 253–264. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2017.01.015.

- Ryan, D., and M. Micozzi. 2021. “The Politics of Climate Policy Innovation: The Case of the Argentine Carbon Tax.” Environmental Politics 30 (7): 1155–1173. doi:10.1080/09644016.2021.1899648.

- Sanderink, L., P. Pattberg, and O. Widerberg. 2020. “Mapping the Institutional Complex of the Climate-Energy Nexus.” In Governing the Climate-Energy Nexus: Institutional Complexity and Its Challenges to Effectiveness and Legitimacy, edited by F. Zelli, K. Bäckstrand, N. Nasiritousi, J. Skovgaard, and O. E. Widerberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schön, D. A., and M. Rein. 1994. Frame Reflection: Toward the Resolution of Intractable Policy Controversies. New York: Basic Books.

- Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público. 2020. Ingresos Presupuestarios Del Gobierno Federal. http://presto.hacienda.gob.mx/EstoporLayout/Layout.jsp.

- SEMARNAT. 2014. Mexico’s Climate Change Laws and Policies. https://www.thepmr.org/system/files/documents/Mexico_Climate_Change_Law_and_Policies.pdf.

- Senado de la República de México. 2013. Registro de Votaciones: Ley de Impuesto Especial Sobre Producción y Servicios. https://www.senado.gob.mx/64/votacion/1820.

- Silva Rodríguez de San Miguel, J. 2018. “Climate Change Initiatives in Mexico: A Review.” Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 29 (6): 1042–1058. doi:10.1108/MEQ-03-2018-0066.

- Simon, S., T. Naegler, and H. Gils. 2018. “Transformation towards a Renewable Energy System in Brazil and Mexico: Technological and Structural Options for Latin America.” Energies 11 (4): 907. doi:10.3390/en11040907.

- Skovgaard, J. 2014. “EU Climate Policy after the Crisis.” Environmental Politics 23 (1): 1–17, doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.818304.

- Skovgaard, J., S. Sacks Ferrari, and Å. Knaggård. 2019. “Mapping and Clustering the Adoption of Carbon Pricing Policies: What Polities Price Carbon and Why?” Climate Policy 19 (9:) 1173–1185, doi:10.1080/14693062.2019.1641460.

- Steinebach, Y., X. Fernández-I-Marín, and C. Aschenbrenner. 2020. “Who Puts a Price on Carbon, Why and How? A Global Empirical Analysis of Carbon Pricing Policies.” Climate Policy 21 (3): 1–13.

- Stevens, D. 2021. “Institutions and Agency in the Making of Carbon Pricing Policies: Evidence from Mexico and Directions for Comparative Analyses in Latin America.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice (Accepted) 23 (4): 485–504. doi:10.1080/13876988.2020.1794754.

- World Bank. 2019. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2019. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/191801559846379845/State-and-Trends-of-Carbon-Pricing-2019.

- Veysey, J., C. Octaviano, C. Calvin, S. Herreras Martinez, A. Kitous, J. McFarland, and B. van der Zwaan. 2016. “Pathways to Mexico’s Climate Change Mitigation Targets: A Multi-Model Analysis.” Energy Economics 56 (May): 587–599. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2015.04.011.

Appendix: List of interviews

Interviewee 1—Former Senior Centro Mario Molina and Ministry of Finance employee, 7 May, 2019

Interviewee 2—Former Senior Ministry of Environment official, 22 October 2019

Interviewee 3—Senior Ministry of Finance Official, 14 May 2019

Interviewee 4—Former Centro Mario Molina expert, 14 May 2019

Interviewee 5—Former Senior Ministry of Environment Official, 8 May 2019

Interviewee 6—Industry association representative, 10 May 2019

Interviewee 6—Industry association representative, May 10, 2019