Abstract

The financial foundation of Germany’s manufacturing success, according to the comparative capitalism literature, is an ample supply of long-term capital, provided to firms by a three-pillar banking system and ‘patient’ domestic shareholders. This premise also informs the recent literature on growth models, which documents a shift towards a purely export-led growth model in Germany since the 1990s. We challenge this common assumption of continuity in the German financial system. Export-led growth, characterised by aggregate wage suppression and high corporate profits, has allowed non-financial corporations to increasingly finance investment out of retained earnings, thus lowering their dependence on external finance. This paper documents this trend and shows that business lending by banks has increasingly been constrained on the demand side, reducing the power – and relevance – of banks vis-à-vis German industry. The case study suggests a need for students of growth models to pay greater attention to the dynamic interaction between institutional sectors in general, and between the financial and the non-financial sectors in particular.

INTRODUCTION

In the comparative political economy literature, Germany has long been viewed as a paradigm of coordinated capitalism thriving on the export of advanced manufactured goods. According to the varieties of capitalism (VoC) approach, German banks, by lending extensively while simultaneously holding shares and controlling large blocs of votes in large enterprises, encouraged firms’ long-term investment in workforce skills and incremental product innovation – the foundations of German export success (Hall and Soskice Citation2001). Although Germany has always been considered an export-oriented economy, in recent years scholars have diagnosed the emergence of a full-fledged export-led growth model, with exports doubling from just under 20 percent of GDP in the early 1990s to more than 40 percent of GDP by 2007 (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016, 14). The new literature on growth models explains this explosion of German exports as the result of wage restraint and the suppression of domestic consumption (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016; Johnston and Regan Citation2016; Stockhammer Citation2016; Stockhammer, Durand, and List Citation2016; Regan Citation2017; Höpner and Lutter Citation2018). According to this literature, nominal wage increases trailing productivity increases, combined with low consumer debt, have stifled domestic spending and price inflation, thus boosting Germany’s real exchange rate and export firms’ price competitiveness, most notably within the European Union. Important differences notwithstanding, the growth model perspective has largely taken for granted the VoC notion of institutional complementarity between the financial and the export sector. The present paper challenges that notion.

We start from the premise that the business activities of economic actors do not automatically reproduce complementarities between sectors and institutions and may, in fact, undermine them. While the declining importance of German banks for the corporate sector has received notable empirical attention, the link to export-led growth has been overlooked. We argue that both VoC and the growth model literature have failed to recognise the feedback effects of Germany’s export-boosting competitive wage and price disinflation on the domestic banking system. The case is one of unintended consequences. Since the early 1990s, the export-led growth model has undercut banks’ erstwhile hegemonic position in the German economy by enabling non-financial corporations to increasingly finance investment from retained profits, and even to accumulate substantial savings.

Our contribution to the comparative political economy literature is threefold. Methodologically, the paper demonstrates the value of detailed, sectoral balance sheet data (Bezemer Citation2016; Allen Citation2018). Headline numbers – such as bank credit as a share of GDP – facilitate cross-national comparison but risk missing changes within economies. In the case of Germany, looking at and (partly) disaggregating both the asset side of bank balance sheets and the liability side of corporate balance sheets reveals important changes that remain invisible from an aggregate, cross-national perspective. Case studies based on detailed financial accounts data can generate important insights (which then, in a second step, can inform new comparative research designs). Theoretically, our argument raises important new questions about the dynamic, out-of-equilibrium interactions between institutions in general, and between the financial and the non-financial sector in particular (Streeck Citation2009; Mertens Citation2015). In particular, it draws attention to endogenous sources of instability within growth models, and thus to their limited life span. The existence at time t of a coherent growth model based on institutional complementarity does not preclude the endogenous emergence of destabilising pathologies (Blyth and Matthijs Citation2017). Social actors may defect, or be excluded, from the dominant ‘social bloc’ supporting the growth model at t + 1, thus helping to bring about the ultimate disintegration of the model at t + 2 (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2019). If our analysis is correct, Germany’s banks may be drifting out of the social bloc carrying the country’s export-led growth model. Finally, our findings are relevant to ongoing policy debates. The argument that ‘bank regulation hurts SME financing’ is ubiquitous in the discourse about financial policymaking. The notion that SMEs are financially constrained has also fuelled the EU agenda for a more market-based financial system with better SME access to capital markets (Braun and Hübner Citation2018; Hübner Citationforthcoming). While SMEs in some euro area countries have indeed suffered a severe credit squeeze, the evidence for Germany points not to weak supply of capital from the financial sector but to weak demand by highly profitable non-financial firms.

The paper proceeds as follows. The first section will briefly review the literatures on corporate finance and on growth models. The second section will present comparative data on non-financial corporations (NFCs) in order to establish that German NFCs have been highly profitable, have had uniquely low levels of debt, and have become net lenders to the economy, accumulating considerable net financial wealth. The third section will delve deeper into data on the liabilities of NFCs and on the assets of the banking sector, showing that bank lending to German businesses has actually declined as a share of GDP and, in the case of the manufacturing sector, even in absolute terms. The fourth section documents how banks have sought to compensate for the loss of business with non-financial corporations, namely through the financialization and internationalisation of their loan books. These substitutions, however, could not prevent the erosion of banks’ net interest income. The final section concludes our discussion and suggests some avenues for further research.

CORPORATE FINANCE AND GROWTH MODELS: DEMAND FOR FINANCING AS A MISSING VARIABLE

The literature on the relationship between the financial and the non-financial sectors has largely focused on the supply side of the capital market. It is a well-established finding in political economy that financial liberalisation and globalisation have generally increased the power – and thus the profitability – of finance vis-à-vis the non-financial sector because of increased capital mobility (Grittersová Citation2014, 363). Firms depend on finance to carry out their activities. For larger companies, the three main external financing instruments are loans, bonds, and shares.Footnote1 The counterparties associated with these instruments vary over time. Loans are still mostly made by banks (but non-bank lenders are on the rise), while bonds and shares are held by a diverse and evolving set of domestic and international investors. In Hirschman’s terms, the power of these financiers over NFCs resides in their ability to (threaten to) discontinue financing relationships (exit) or to leverage their investment to engage directly with NFC management (voice). In addition to the exit options on the supply side of the capital market, however, the exit options on the demand side are equally important. Investor or creditor power varies with the degree to which non-financial corporations depend on external funding. Corporate demand for bank loans, and thus bank power, may decrease because NFCs can substitute bond issuance for bank borrowing (assuming banks do not also dominate bond holdings), or because they enjoy high corporate profits making them less dependent on external financing altogether. Thus, German banks were at their most dominant at the beginning of the twentieth century and again during the postwar decades, before firms’ increased profitability and access to capital markets contributed to a relative ‘decline of the market power of the banks over industry’ (Zysman Citation1983, 263; Deeg Citation1999).

As the primary nexus between the financial and the non-financial sector, corporate finance has long occupied a central place in comparative political economy. Most importantly, the varieties of capitalism approach emphasises the complementarities between different corporate finance institutions and other parts of the economy (Hall and Soskice Citation2001; Amable Citation2003). In liberal market economies (LMEs), market-based finance dominates and power is concentrated in shareholders (and, to a lesser extent, bondholders). In coordinated market economies (CMEs), bank-based finance prevails (or used to). In Germany, banks once served as one-stop shops for the financing needs of firms, acting both as lenders and as anchor investors (further leveraged through widespread proxy voting), as well as underwriters of securities. As NFCs’ dominant creditors, shareholders, and board members, banks overcame the information asymmetries that usually afflict outside stakeholders, thus gaining considerable power over non-financial corporations. This power was consistent with – indeed complementary to – Germany’s manufacturing-focused growth model because banks provided the patient capital that allowed German firms to pursue long-term strategies and engage in incremental innovation (in conjunction with labour market and vocational training institutions, among others) (Deeg Citation1999; Vitols Citation2001; Allen Citation2006).

Since the VoC theory was first established, however, both the financial and the non-financial sectors have changed dramatically – to the point where ‘coordinated market economy’ may no longer capture the essence of former CMEs such as Germany. In the financial sector, both the capital investment chain and business lending have been transformed. Regarding the former, an extensive literature has documented the dissolution of ownership networks, the large-scale entry of US and UK institutional investors into the stock markets of countries such as France, Germany, and Italy, and thus the internationalisation and marketisation of domestic stock markets (Beyer and Höpner Citation2003; Culpepper Citation2005; Deeg Citation2005, Citation2009). Regarding business lending, the notion that European ‘bank-based’ financial systems were still dominated by traditional, relationship-based banking has been challenged by the work of Hardie et al. (Citation2013a, Citation2013b). In the years running up to the 2008 financial crisis, the activities of commercial banks partly shifted from traditional, relationship-based banking to ‘market-based banking,’ defined as wholesale money-market borrowing to finance bank loans, which in turn are designed to be securitised and sold. The result was that banks and securities markets became increasingly indistinguishable in a functional sense.

The non-financial sector too has changed in formerly coordinated market economies. In general, CMEs have seen a much larger decline in the labour share of income than LMEs, while generating higher current account surpluses (Behringer and van Treeck Citation2018). The quintessential case is Germany. Beginning in the 1990s, Germany transitioned from balanced growth – with both domestic consumption and exports contributing to demand growth – to an overwhelmingly export-led growth model (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016; Johnston and Regan Citation2016; Stockhammer Citation2016; Stockhammer, Durand, and List Citation2016; Regan Citation2017). Research on the institutional underpinnings of Germany’s export-oriented growth model focuses mainly on unit-labour cost competitiveness. Germany’s unit labour cost index for the total economy – which is consistent with the real effective exchange rates but considers both intra- and extra-euro area trade – has declined by 17.5 percent since 1999. No other euro area member (except Ireland, arguably a special case) has increased its international cost competitiveness by a comparable margin (ECB Citation2018). In view of this development, the CPE literature has highlighted Germany’s capacity for wage coordination and wage-growth suppression, which has delivered a significant competitive advantage to Germany, both within and beyond the euro area (Palier and Thelen Citation2010; Hassel Citation2014; Johnston, Hancké, and Pant Citation2014; Baccaro and Benassi Citation2017; Hall Citation2017; Di Carlo Citation2018; Höpner and Lutter Citation2018; Scharpf Citation2018). Other factors, notably fiscal federalism and the financing structure of social security, have further contributed to the suppression of wages and of domestic demand (Hassel Citation2017).

It is important to note that our argument does not presuppose a strong causal link between unit-labour cost developments and export growth – an issue that remains hotly debated. Critics of the cost-competitiveness explanation argue, first, that labour costs – which include other employer-borne, labour-related costs in addition to wages – are much lower in the private service sector (€31.5 per hour) than in the export-oriented manufacturing sector (€40.2 per hour). The gap of 21.6 percent is the highest among all EU-28 member states (Albu et al. Citation2018, 7).Footnote2 The second objection is that unit labour cost developments can only explain a small fraction of export growth, which instead has been driven by the non-price (i.e. quality) competitiveness of German exports (Storm and Naastepad Citation2015). For the present argument, however, the question of the causal effect of cost competitiveness on export performance is secondary. Instead, our argument highlights the effect of unit labour costs on the balance sheets of both corporations and banks. Here, what matters is that the labour share of income declined more in Germany than elsewhere (Berger and Wolff Citation2017; Behringer and van Treeck Citation2018). Lower wage costs that are not (fully) reflected in lower prices, regardless of their causal influence on exports, are equivalent to a higher profit share. To the extent that these higher profits are not paid out to owners or shareholders, they increase the financial independence of non-financial corporations (on profit shares, see below).Footnote3

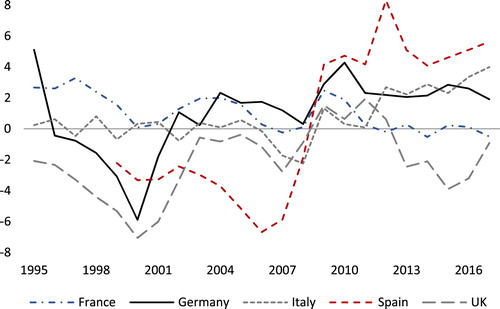

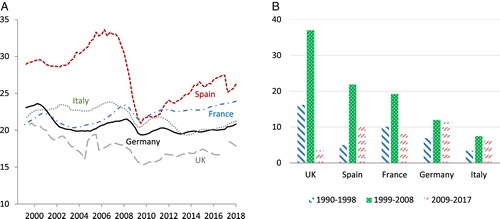

FIGURE 1. NFC GROSS PROFIT SHARE, % OF GPD, 1995–2018. Source: Eurostat.

Note: German and Italian national accounts include quasi-corporations with non-salaried employees in the NFC sector, inflating gross operating surplus relative to other countries

What matters for our argument is timing: When exactly did wage restraint increase and current surpluses take off? The German economy already featured a fully functional ‘undervaluation regime’ during the Bretton Woods period (Höpner Citation2019) and was characterised by a strong export orientation in the 1970s and 1980s – a fact sometimes obscured by the temporary drop of the current account surplus following unification. Still, it was during the period between the Maastricht Treaty and the introduction of the euro that Germany transitioned to a purely export-led growth model: exports as a share of GDP began to grow again in 1993, following a recession brought about by a series of interest rate hikes by the Bundesbank in response to wage and price pressures (Scharpf Citation2018, 28). The trade surplus, which had been growing throughout the 1990s from a low post-unification base, started growing rapidly beginning in 2000 (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016; Behringer and van Treeck Citation2018; Scharpf Citation2018). The surplus continued to increase after the 2008 financial crisis, when demand from outside the euro area – above all from China – compensated for lower demand from within the struggling euro area (Mody Citation2018, 423).

In sum, both developments in the financial sector and developments in the real economy have received significant attention in political economy literature on Germany. The positive contribution of the financial sector to German firms’ internationalisation – in terms of both sales and production – has also been noted, especially with regard to the close cooperation between banks and NFCs. This is mirrored by an appreciation of the contribution of the financial sector to the credit-financed consumption-led growth model, exemplified by the UK, which ‘presupposes the existence of a large financial sector’ (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016, 186).Footnote4 What has been missing from the discussion, however, is the question of feedback effects in the other direction: What, if any, have been the feedback effects from export-led growth on the financial sector? The remainder of this paper seeks to fill this gap.

EXTERNAL FINANCE IN AN EXPORT-LED GROWTH MODEL: WEAK DOMESTIC DEMAND

How much power banks wield vis-à-vis non-financial corporations hinges, in part, on how much the latter depend on the credit provided by the former. We argue that Germany’s export competitiveness – and its flipside, high corporate profits – have weakened its banks’ power.Footnote5 Three conditions must be met for the hallmark of the export-led growth model – competitive wage restraint – to substantially increase firms’ financial independence from banks. First, unit labour cost advantages over competitors are not passed on in full to customers in the form of lower product prices (Storm and Naastepad Citation2015). Second, the resulting higher profits are not fully re-invested (Beyer and Hassel Citation2002) nor, third, fully paid out to shareholders in the form of dividends or share buybacks (De Jong Citation1997). This section presents comparative data establishing five empirical observations: the increase in the profit share of German non-financial corporations, their low debt levels, their high rate of internal financing, their low levels of investment, and the shift of the NFC sector from net borrowing to net lending. Together, these observations suggest that the conditions hold for export-sector strength to feed back into banking-sector weakness.

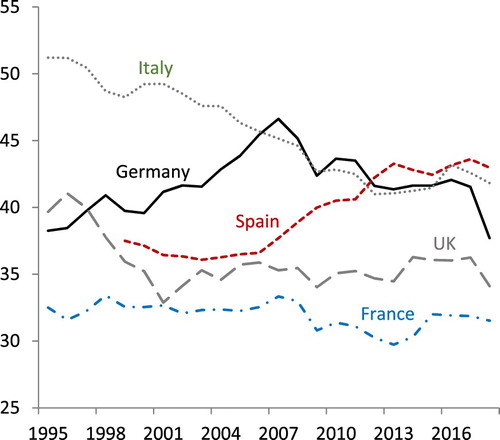

The suppression of wage growth, relative to productivity growth, is a key element of Germany’s post-1990s export-led growth model.Footnote6 Wages have kept up with productivity relatively well for high value-added jobs in the manufacturing sector, but have failed to keep up even with inflation in the service sector and, partly, in the public sector (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016; Baccaro and Benassi Citation2017; Albu et al. Citation2018; Di Carlo Citation2018). To the extent that wage suppression does not translate into lower prices, it raises corporate profits. shows that the gross profit share of German NFCs rose from 38 to 47 percent of GDP during Germany’s competitive wage and price disinflation, making Germany a clear outlier in the period from 1995 through 2007. As a corollary, the wage share, which had stabilised in France, Italy, Spain, and the UK, kept falling in Germany (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016; Berger and Wolff Citation2017; Behringer and van Treeck Citation2018). Since 2007, the corporate profit share in Germany has fallen back to the level of 1995.

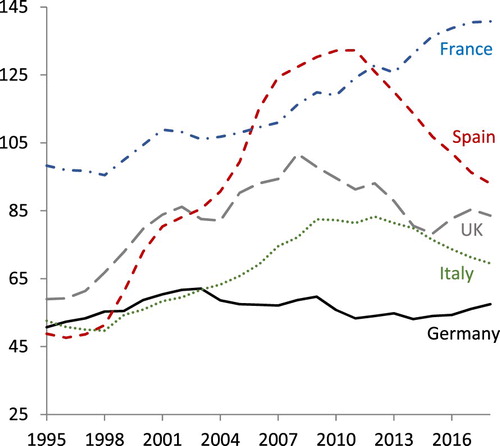

The second observation concerns the volume of borrowing by non-financial corporations, depicted in . As can be expected, the image is reversed: high historical profit shares in Germany are associated with low levels of NFC debt, while relatively lower profits shares in France are associated with steadily rising debt levels. What is most remarkable, however, is that Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK started off in the same place, with NFC borrowing at around 55 percent of GDP in 1995. However, corporate debt levels rose significantly during the 2000s in Italy, Spain, France, and the UK, while actually falling in Germany, from a high of 60 percent of GDP in 2003 to 54 percent in 2017. With regard to borrowing by the non-financial sector, Germany has been a clear outlier.

FIGURE 2. TOTAL BORROWING BY NFCS, % OF GDP, 1995–2018. Source: BIS total credit statistics.

Note: Total borrowing includes loans and debt securities

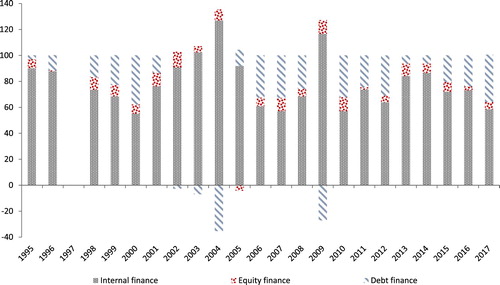

Third, a high profit share and low debt levels imply a high rate of self-financing of German NFCs. Retained earnings constitute the most patient and, according to the pecking order theory of corporate finance (which emphasises information asymmetries), the cheapest form of financing for firms. German firms’ rate of self-financing grew from the early 1970s (Edwards and Fischer Citation1996; Deeg Citation1999, 86) and, as shown in , has remained high throughout the past two decades. Since 1995, the German corporate sector has had an average rate of self-financing of 75 per cent. Note that the mild ups and downs of the black line in , which indicate total borrowing by German NFCs, reflect the fluctuations of debt financing in NFCs’ financing mix, depicted in . The episodes of deleveraging (net repayment of debt) in 2004 and 2009 show up in as periods of declining total borrowing. It is also evident from that stock markets are not a major source of financing for German corporations.

FIGURE 3. SOURCES OF NEW FINANCING OF GERMAN NFCS, % OF THE INFLOW OF FUNDS, 1995–2017. Source: Bundesbank

Fourth, abundant internal finance has not translated into high levels of corporate investment. As shown in (A), gross fixed capital formation – measured as a share of gross value added for comparability – has trended down in Germany since the late 1990s. These numbers do not include outward foreign direct investment (FDI), which might be expected to change the picture, given German NFCs’ push to increase productive capacities abroad, especially in Eastern Europe. (B) shows average annual outward FDI flows, measured as a share of gross fixed capital formation. During the pre-2008 period, German outward FDI was below the average of our five-country sample. It has been slightly higher than in the other four countries only in the post-crisis period.Footnote7 In short, high corporate profits in Germany have not led to increased capital investment.

FIGURE 4. (A) GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION BY NFCS, % OF NFC GROSS VALUE ADDED, 1999–2018. Source: ECB. (B) OUTWARD FDI AS A SHARE OF GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION, 1990–2017. Source: UNCTAD

We have shown that the corporate profit share and the rate of internal financing have been consistently high in Germany, while corporate debt levels have remained uniquely subdued. Together, these factors accentuate the fifth observation, depicted in – the shift of the corporate sector from net borrowing to net lending. Just like the falling labour share, corporate net lending has emerged as a new trend in many advanced economies (Chen, Karabarbounis, and Neiman Citation2017; Glötzl and Rezai Citation2018). Still, the data reveal important differences among the five countries. The late 1990s drop in net lending and spike in net borrowing associated with the dotcom stock market boom was particularly pronounced in Germany. The swift rebound of corporate saving after the dotcom market crash coincided with the developments described above: wage restraint and a rising corporate profit share.Footnote8 A similarly dramatic shift occurred in the UK. In Italy and Spain the corporate sector swung into net lending only after the 2008 financial crisis. Unlike in Germany, this swing was driven by a fall in investment (notably dramatic in Spain, where construction collapsed), mass layoffs, and falling real wages.

Net lending is a flow measure. Another way to measure increased financial independence is corporate balance sheets via net financial wealth, defined as financial assets minus non-equity liabilities. In 1995, net financial wealth of German NFCs stood at zero and has since risen to 38 percent of GDP.Footnote9 In Italy, Spain, and the UK, the NFC sector’s net financial wealth has remained negative throughout the period. Importantly, corporate saving in Germany has not been limited to large corporations. Between 2002 and 2017, small and medium-sized enterprises have increased their equity ratios – assets minus non-equity liabilities, divided by total assets – from 18.4 percent to 30 percent (KfW Citation2018). At least in the post-crisis period, this deleveraging reflects a precautionary motive: it makes a firm more financially independent at a time when banks, under Basel III and its EU implementation, faced stricter regulatory risk weights for SME lending (Keller Citation2018).

In sum, by using high profits to bolster their financial position, German firms have greatly increased their financial independence. Banks have suffered the consequences. This is because, even though non-financial corporations are net lenders (see above), they continue to be the single largest borrowing sector, which means banks still rely heavily on them for their business (see below). How then does this affect the volume and the profitability of business lending by banks? The question has hardly been asked – let alone answered – in comparative political economy. While the literature on market-based banking has rightly pointed to an increase in fee-based activities and increased bank financing via markets, it has not renewed engagement with the role of banks in different growth models. The growth-model literature, meanwhile, has focused mostly on wage dynamics and on the sources of aggregate demand. The remainder of this paper zooms in on the volume and composition of bank lending to NFCs (Section 4) and on the profitability and the coping strategies of the German banking sector (Section 5).

BANK LENDING TO NON-FINANCIAL CORPORATIONS: SHRINKING SLICE OF A SHRINKING PIE

A closer look at the liability side of the aggregate balance sheet of the NFC sector reveals that the share of bank loans in total NFC borrowing has steadily declined. Meanwhile, data from the asset side of banks shows that the composition of bank lending to NFCs has changed, with large commercial banks seeing the largest drop in market share.

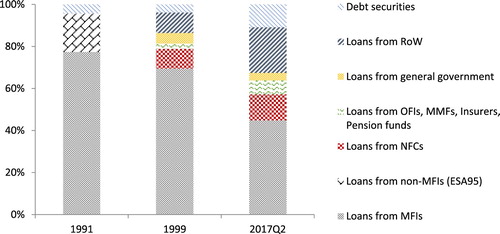

As shown in above, the GDP share of borrowing by German NFCs has been flat for the past two decades. On top of that lack of growth in business lending, German banks have faced increasing competition. shows the structure of NFCs’ outstanding debt liabilities since 1991, including borrowing from monetary financial institutions (MFIs), but also borrowing from non-monetary financial institutions (non-MFIs) as well as debt securities. The share of bank lending in total NFC debt has declined from 75 percent to 50 percent. In other words, of every euro German non-financial corporations borrow, only 50 cents are borrowed from German banks. The remaining 50 percent come from debt securities, the rest of the world (a category that includes foreign banks), and from loans extended by domestic non-banks: other non-financial corporations, institutional investors and asset managers, and the government.

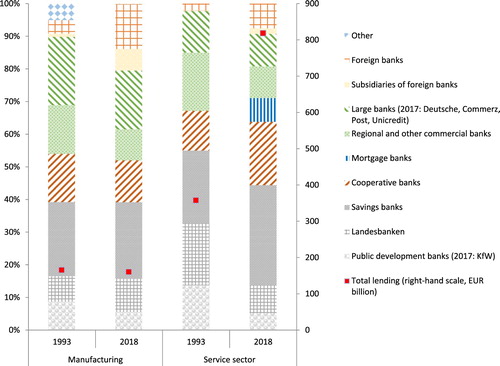

While the shrinking of bank lending relative to other sources of NFC credit would be bad enough for the banking sector, only the next level of granularity – the sectoral distribution and the composition of bank lending – reveals the full extent of bank shrinkage. The sectoral distribution of nominal bank lending is indicated by the red squares in . They show that while the total value of bank lending to the service sector increased by more than 50 percent between 1993 and 2018, bank lending to the export-oriented manufacturing sector decreased slightly. The share of manufacturing loans in total NFC lending by banks fell by half, from 32 to 16 percent, even as the manufacturing share of GDP remained largely stable (De Ville Citation2018, 16).

FIGURE 7. BANK LENDING TO DOMESTIC NON-FINANCIAL CORPORATIONS, BY TYPE OF BANK, 1993 & 2018, PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL (LHS); TOTAL LENDING IN EUR BILLION (RHS). Source: Bundesbank

Beside the absolute amount, the share of bank lending by different types of bank has also changed since 1993 to the detriment of commercial banks. Cooperative banks have held their ground in the manufacturing sector and have expanded significantly in the service sector. The commercial banks (green bars in ), by contrast, have seen their share of lending to manufacturing firms fall from a combined 36 percent in 1993–28 percent in 2018.Footnote10 This represents a shrinking slice of a shrinking pie. The grey-shaded areas in represent public, government-owned banks: Sparkassen, Landesbanken, and the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau or KfW (owned jointly by municipalities, state governments, and the federal government). In contrast to commercial banks, public banks have significantly increased their share of total lending: in the manufacturing sector mostly due to the Landesbanken; in the service sector mostly due to the savings banks. This is consistent with the finding that post-crisis policies in Germany have systematically shielded domestic public banks from competition (Massoc Citation2019).

The KfW, which has long focused on promoting German exports, has also expanded its role in NFC finance along with the intensification of the German export model (Naqvi, Henow, and Chang Citation2018). Until the 1980s, the KfW’s assets and total lending commitments ranged between 0.5 per cent and 1 per cent of GDP. The KfW financed itself largely with funds drawn directly from the Ministry of Finance and focused on export finance for German industry and lending in strategic sectors. Beginning in the 1980s, and especially thereafter as a result of increased restrictions from the EU, the KfW shifted its funding sources to the domestic and international markets. Given its state guarantees, the KfW has top credit ratings and can borrow at the lowest rates. The success of Airbus or the dramatic expansion of the renewable energy industry in Germany (which has become an important export sector), for example, are practically unimaginable without the large-scale funding from the KfW (Ergen Citation2015, 232–233).

In sum, the data presented in this section shows that demand from non-financial corporations for bank loans has declined. Moreover, not only did the pie shrink for domestic banks, they also had to fight foreign and non-bank competitors over the crumbs. Most notably, the commercial banks – long viewed as the pillar of the German export model – fared the worst among all competitors. The developments described continue long-standing trends: in the 1980s tax changes encouraged firms to rely more on internal financing, while in the 1990s regulatory changes, especially at the European level, facilitated capital market financing as well as international borrowing (Deeg Citation1999). Since then, firms have sought to further increase their financial independence, motivated partly by a financial-crisis-induced awareness of the volatility of bank lending, partly by the relatively harsh treatment of corporate loans under Basel II and III (KfW Citation2018).

IN SEARCH OF LOAN DEMAND: FOREIGN AND FINANCIAL BORROWERS, AND THE DECLINING INTEREST MARGIN

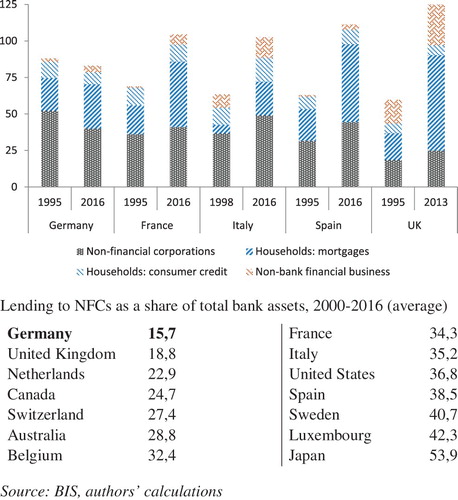

How does the German banking sector cope with the gradual withering away of business lending? The experience of banks elsewhere would point towards household lending as the new name of the game. Newly compiled long-term, cross-country data on bank balance sheets shows a decisive shift over the last four decades from business lending to lending to households as households have increased their indebtedness, primarily in the form of mortgage loans (Jordà, Schularick, and Taylor Citation2016; Bezemer, Samarina, and Zhang Citation2017). , which illustrates the evolution of domestic bank lending in two snapshots – 1995 and 2016 – clearly shows this ‘debt shift’ (Bezemer, Samarina, and Zhang Citation2017). Even with the pre-crisis boom years excluded, lending to the household sector has substantially increased in France, Italy, Spain, and the UK, and today – with the exception of Italy – accounts for the majority of bank lending.

FIGURE 8. LENDING BY DOMESTIC BANKS TO DOMESTIC PRIVATE SECTORS, 1995 VS. 2016 (OR YEARS AS AVAILABLE), PERCENTAGE OF GDP. Source: Bezemer, Samarina, and Zhang (Citation2017)

Germany is, once again, the exception to these broader national trends: the GDP share of bank lending to households has only marginally increased, and lending to non-financial corporations continues to account for almost half of all domestic bank lending. Leaving it there would be highly misleading, however. For one thing, the trend of German bank lending to domestic NFCs has been sharply downward, declining from a maximum of 60 percent of GDP in 2000 (year not shown in the chart) to just under 40 percent in 2016. However, it is only when taking into account total bank assets that the most striking – because it is at odds with the conventional view – feature of business lending becomes apparent: its volume is uniquely small among advanced economies. Between 2000 and 2016, bank lending to NFCs accounted for a mere 16 percent of total bank assets in Germany, versus 34–38.5 percent in France, Italy, and Spain, and 54 percent in Japan. Clearly, then, German banks had to find borrowers elsewhere.

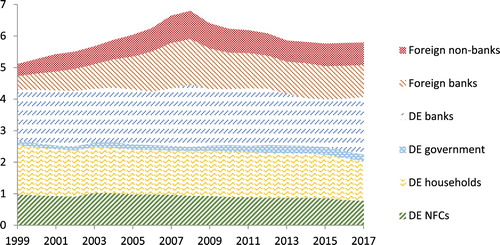

Indeed, debt shift took a different form for German banks, namely a combination of financialization and internationalisation. presents bank lending data segmented by domestic and international borrowing sectors since 1999. The only sectors that have seen growth are banks and foreign borrowers (the latter including both non-bank financial corporations and non-financial corporations). Lending to banks has increased both at home and abroad, from a combined 40 percent to 50 percent of total bank lending. This increase in lending to the financial sector is consistent with another measure of the financialization of banking: in no other country in the euro area do ‘assets held for trading’ account for a larger share of total bank assets than in Germany (cf. Hardie et al. Citation2013a, 721; ECB Citation2017, 34). Thus, both the finance-tilt of the loan book and the size of the trading book indicate that German banks have become increasingly financialized while less directly connected to the real economy.

FIGURE 9. TOTAL LENDING BY GERMAN BANKS, BY BORROWING SECTORS, EUR TRILLION, 1999–2017. Source: ECB, Bundesbank, authors’ calculations

The second aspect of the German variant of the debt shift is the internationalisation of bank lending. Until the 1980s, growth in foreign lending was mostly the result of banks accompanying domestic clients that expanded their operations abroad (Mertens Citation2017, 23). Prior to the introduction of the euro, lending to foreigners grew in line with European financial integration, notably following the Second Banking Directive of 1992 (Mertens Citation2017, 20). Since the introduction of the euro, foreign lending (the top two layers in ) – composed of lending to foreign banks and foreign non-banks – has continued to grow rapidly, from 16 percent of total lending in 1999 to 29 percent in 2017. This internationalisation of banks’ loan books reflects the lending channel of German capital outflows which constitute the flipside of the country’s current account surplus. From this one might argue that the contribution of banks to Germany's current export-led growth model is indirect and resides in their role in facilitating the capital exports that counterbalance trade surpluses. Between 2000 and 2015, Germany’s net financial assets – its foreign assets minus its foreign liabilities – grew from zero to EUR 1.49 trillion, or 44 percent of GDP (Lane and Milesi-Ferretti Citation2007). However, banks are not the only financial institutions intermediating outward capital flows, which take the form not only of bank loans but also of portfolio investment and foreign direct investment. By the end of 2017, the banking sector’s claims against the rest of the world stood at EUR 1.13 trillion – less than the EUR 1.33 trillion of claims held by investment funds, the banks’ main competitor in that area (Sigl-Glöckner Citation2018).

The double-strategy of financializing and internationalising their lending activities allowed German banks to keep their loan assets roughly constant in GDP terms. Have they managed to safeguard their profitability too? Here, we focus on the key determinant of commercial banks’ earnings, the interest margin – the difference between the interest earned on loan assets and the interest paid on deposit liabilities – and the related measure of net interest income. The interest margin is a function of the competition among banks on the supply side, and of the behaviour of borrowers on the demand side.

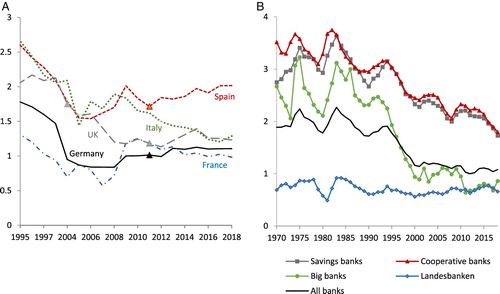

The traditional explanation of banks’ interest margin focuses on the supply side, namely the high level of competition that has long been a feature of German banking (Deeg Citation1999).Footnote11 Starting in the late 1960s, the three groups of banks increasingly competed across the full range of lending activities. Other things being equal, competition between banks, or lack of market power, should lower the cost of borrowing for non-financial corporations, especially SMEs (Ryan, O’Toole, and McCann Citation2014). The effect on banks’ interest margin should be negative. The data, however, suggest that this supply-side story was far less important than the decline in loan demand from NFCs documented in this paper. (A) shows banks’ net interest income over total assets for five countries. German banks (solid black line), which were at the lower end of the spectrum already in 1995, saw a steep drop in their net interest income during the ensuing decade. Whereas interest margins have since recovered in France and Spain, they have remained near record lows in Germany, UK, and Italy. (B), which displays longer time series for German banks only, puts this drop in perspective. Despite increased competition in German banking beginning in the late 1960s, net interest income for the aggregate banking sector was flat, oscillating around 2 percent, up until the early-1990s. Between 1995 and 2008 – the years characterised by export-led growth, a rising profit share, and falling loan demand from NCFs – German banks saw their net interest income fall by more than half, from 1.78 to 0.84 percent of total assets, representing the largest percentage drop among the five countries.Footnote12 While the interest margin has stabilised in recent years for German banks, this is largely due to the experience of Landesbanken and mortgage banks. Net interest income has continued to decline for all other categories of banks (Bundesbank Citation2017, 75).

FIGURE 10. (A) NET INTEREST INCOME OF BANKS, % OF TOTAL BANK ASSETS, 1995–2018. Source: ECB. (B) NET INTEREST INCOME OF GERMAN BANKS, % OF TOTAL BANK ASSETS, 1970–2018. Source: Bundesbank

Note: Linear interpolation over missing values for 1999–2003 and four individual country-years highlighted in panel (A).

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

As recently as twenty years ago many German observers, particularly on the Left, decried the ‘power of the banks’ in Germany. While in reality the decline of bank power began even earlier, it has been especially pronounced over the last two decades. To some extent, this decline was a product of both bank strategy and public policy. The large-scale sell off by banks of their equity stakes in Germany Inc. followed the Eichel tax reform of 2001 and is well documented in the literature. The second mechanism undermining bank power, the growing financial independence of non-financial corporations, was already visible at the inception of the euro (Deeg Citation1999, 86), but greatly increased over the past twenty years. During this period, Germany shifted to a purely export-led growth model based on wage restraint. While the varieties of capitalism literature emphasises the institutional complementarity between the German banking system and NFCs’ export orientation, the growth model literature highlights the low-wage, high-profit nature of Germany’s export-led growth model (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2016; Stockhammer Citation2016). Neither of these literatures, however, has investigated potential negative feedback effects from the export-led growth model on the banking system.

Seeking to fill this gap, we show that the German banking system, the erstwhile secret sauce of Germany’s export success, became a victim of that success. Export-led growth in Germany has been associated with higher corporate profits, higher retained earnings, and thus higher financial independence of non-financial corporations. By and large, NFCs’ internal financial resources suffice to finance their investments, and the non-financial sector has actually become a net lender to the rest of the economy. Both total lending and bank lending to NFCs as a share of GDP have been flat. At the same time, the share of bank lending as a share of total NFC liabilities has fallen by half, from 28 percent to 15 percent. To the extent that they borrow, NFCs have reduced their borrowing, in particular from domestic private banks. Much of this relative decline in business lending has been driven by the manufacturing sector which dominates German exports and whose total bank borrowing has actually declined even in both absolute and real terms. German banks have felt the pain. Despite aggressive attempts to replace domestic business lending with lending to other financial institutions and to foreigners, net interest income collapsed during the late 1990s and early 2000s. We argue that the decline of German banking has, at least in part, been a collateral consequence of this intensification of export-led growth. The post-2008 problems of many large German banks, not least the Landesbanken, Deutsche Bank and the Commerzbank, are arguably additional manifestations of this shrinking role for banks in corporate finance. More broadly, our case study casts further doubt on the notion of stable institutional equilibria. Instead, it provides a compelling example of a negative inter-sectoral feedback effect and thus of the endogenous erosion of institutional complementarities, which are likely to only ever be temporary (Streeck Citation2009; Blyth and Matthijs Citation2017). We expect that Germany’s banking sector – formerly a core pillar of the country’s dominant ‘social bloc’ – can no longer be counted upon as an influential defender of the export-led growth model (Baccaro and Pontusson Citation2019).

Based on these results, we see two promising avenues for future research. The first is to dig deeper into the dynamic interaction between the financial and the non-financial sectors in different growth models. Here, the theoretical argument put forward in this paper is that feedback effects between those sectors need not be positive. For all we know, it is true that German banks helped German non-financial corporations succeed in the world market. It also seems to be the case, however, that the second-round effect of that success on the German banking sector has been devastating. Future research might study similar second-round effects in other countries/growth models, as well as the potential third-round effect in Germany. Could a weakened banking sector spell trouble for the export-led growth model in the future?

The second avenue for future research concerns the knock-on effects of the decline of the power of lenders over large NFCs that have become essentially self-financing. When the number of supervisory boards chaired by financial sector representatives declined in the late 1990s, these positions were duly filled by executives from within the same corporations (Höpner Citation2003, 138). A similar dynamic is likely to play out as a result of the developments described in this paper. If banks are no longer important financiers of the manufacturing sector, and if German firms rely increasingly on internal finance, then other insiders – management and large shareholders – have arguably gained greater autonomy and power over NFCs and their strategic direction. Regarding the role of management, recent signs of renewed interest, in comparative and international political economy, in studying corporations as actors in their own right are encouraging (May and Nölke Citation2018). Regarding shareholders, the first thing to note is that in an economy in which NFCs depend less on external financing, they also depend less on the issuance of equity into the (primary) stock market. As noted above, the stock market has not been a significant source of net financing for German non-financial corporations. Net share issuance, which collapsed after the bursting of the dotcom bubble in 2000, has not been revived under the intensified export-led growth model. This does not, however, necessarily diminish the power of the owners of outstanding shares. This power is sustained through the ability of shareholders (to threaten) to sell their shares in the secondary market and through the statutory rights shares afford their owners. These mechanisms – ‘exit’ and ‘voice,’ in Hirschman’s terms – allow shareholders to exercise power over portfolio companies regardless of the financing situation of the latter. Thus, the power of shareholders should be expected to be more resilient than the power of banks in Germany’s export-led economy not because large corporations need the stock market for financing, but because in the absence of bank-dependence, shareholder rights become the ‘only game in town’ for financial influence over NFCs.

Comparative political economy is concerned not with shareholder power as such but with the use to which shareholders put their power, i.e. which kinds of market strategies and management models they will support. Here, future research will need to go beyond simple dichotomies and investigate the specific incentives and business models of a range of different investors, and their interaction with different types of portfolio firms (Deeg and Hardie Citation2016; Faust Citation2017). For instance, the largest new owners are index funds, managed by global asset managers such as BlackRock and Vanguard (Braun Citation2016; Fichtner, Heemskerk, and Garcia-Bernardo Citation2017). Unlike active – let alone activist – investors, these funds are by definition long-term investors, while their sheer size, diversification, and business models limit their capacity to use their ‘voice’ aggressively (such as to demand increased dividends). Under these conditions, managerial autonomy remains fairly high, permitting firms to continue the long-term strategies leading to export success. Another area for future research on shareholder power is the growing tendency for large, diversified investors to own large stakes in all competitors in a given industry, often via index-tracking funds (Azar, Schmalz, and Tecu Citation2018). To the extent that such ‘common ownership’ has anti-competitive effects, the compatibility of these effects with the export-led growth model is an open empirical question. Overall, pressure to pay out corporate profits at higher rates seems to remain relatively low, thus reinforcing German NFCs’ low dependence on external finance. Thus, the ownership structure and the preferences of the dominant investors in Germany seem compatible with sustaining an export-led growth model dependent on a combination of wage-growth suppression and domestic-demand suppression.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Mareike Beck, Donato Di Carlo, Michael Faust, Martin Höpner, Alison Johnston, Daniel Mertens, Sidney Rothstein, Michael Schwan, and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on earlier versions of this paper.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Benjamin Braun is a senior researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies in Cologne and a member of the School of Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton (2019–2020). His work on the political economy of central banking and finance has been published, among others, in Economy and Society, Review of International Political Economy, and Socio-Economic Review.

Richard Deeg is the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, Temple University. His research focuses on German and European political economy, with a particular focus on the causes and mechanisms of change in financial market regulation and governance. His work has been published, among others, in Journal of European Public Policy, Socio-Economic Review, and World Politics.

Notes

1. In addition to bank loans, smaller enterprises also rely extensively on credit lines and leasing contracts.

2. This is not to say that there was no wage restraint in the German manufacturing sector – between 1999 and 2008 there certainly was (Höpner and Lutter Citation2018, 82). Note that manufacturing firms do benefit from low labour costs in the service sector. German firms have outsourced corporate services, such as food and cleaning, on a very large scale, especially since the 1990s, reducing the wages of service workers by around 10 percent (Goldschmidt and Schmieder Citation2017).

3. Low financial constraints can, of course, also be a determinant of competitiveness. Recent research based on firm-level data has found a strong negative correlation between financial constraints and productivity in the euro area (Ferrando and Ruggieri Citation2018).

4. For a discussion of the financial conditions that enable the asymmetric distribution of growth models between European countries, see Fuller (Citation2018).

5. Though the problems of Germany’s large banks in the 2008 crisis may have been connected to their plight under the export-led growth model, we make no specific claims to this effect. For a discussion of the very different crisis experiences of Landesbanken and savings banks, see Hallerberg and Markgraf (Citation2018). For an in-depth analysis of the evolving business models of German savings banks, see Schwan (Citation2019).

6. Prior to the 1990s when labour power was stronger, productivity gains were passed on to a greater degree in the form of wage increases.

7. It should be noted that an increasing share of FDI, especially within the European Union, reflects the efforts of multinational corporations to optimise their tax and regulatory structures, reducing the interpretability of headline FDI numbers (Reurink and Garcia-Bernardo Citation2019).

8. The notion that corporate saving is related to the ability – or, in the German context, willingness – of organised labour to claim their share of economic growth finds strong support in Redeker (Citation2019).

9. Note that financial accounts data on corporate financial asset holdings (108 percent of GDP for German NFCs) includes foreign direct investment (59 percent of GDP).

10. Consistent with the more international orientation of manufacturing firms, which account for the bulk of German exports, these firms have increased their borrowing from foreign banks and subsidiaries of foreign banks. Cross-border banking has been greatly facilitated by European financial integration since the early 1990s.

11. It is worth noting that the high degree of competition (and low concentration) that has long been a feature of German banking persisted even in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Indeed, German banking stands out for not having gone through a process of consolidation after the crisis, featuring the second-smallest population per banking employee, the highest cost/income ratio, and the smallest share in total assets concentrated in the five largest banks (not counting Malta, Cyprus, and Luxembourg) (ECB Citation2017, 27, 32, 42).

12. When, in addition to net interest income, net fee income is taken into account, German banks fall to the bottom of the five-country ranking.

References

- Albu, Nora, Alexander Herzog-Stein, Ulrike Stein, and Rudolf Zwiener. 2018. Arbeits- und Lohnstückkostenentwicklung 2017 im europäischen Vergleich. Düsseldorf: Institut für Makroökonomie und Konjunkturforschung.

- Allen, Matthew M. C. 2006. The Varieties of Capitalism Paradigm: Explaining Germany’s Comparative Advantage? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Allen, Cian. 2018. “Revisiting External Imbalances: Insights from Sectoral Accounts”.

- Amable, Bruno. 2003. The Diversity of Modern Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Azar, José, Martin C Schmalz, and Isabel Tecu. 2018. “Anticompetitive Effects of Common Ownership.” The Journal of Finance 73 (4): 1513–1565. doi:10.1111/jofi.12698.

- Baccaro, Lucio, and Chiara Benassi. 2017. “Throwing out the Ballast: Growth Models and the Liberalization of German Industrial Relations.” Socio-Economic Review 15 (1): 85–115. doi:10.1093/ser/mww036.

- Baccaro, Lucio, and Jonas Pontusson. 2016. “Rethinking Comparative Political Economy: The Growth Model Perspective.” Politics & Society 44 (2): 175–207. doi:10.1177/0032329216638053.

- Baccaro, Lucio, and Jonas Pontusson. 2019. Social Blocs and Growth Models: An Analytical Framework with Germany and Sweden as Illustrative Cases. Unequal Democracies: Working Papers 7. Geneva: Université de Genève.

- Behringer, Jan, and Till van Treeck. 2018. “Income Distribution and the Current Account.” Journal of International Economics 114: 238–254. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2018.06.006.

- Berger, Bennet, and Guntram B Wolff. 2017. The Global Decline in the Labour Income Share: is Capital the Answer to Germany’s Current Account Surplus? Brussels: Bruegel.

- Beyer, Jürgen, and Anke Hassel. 2002. “The Effects of Convergence: Internationalization and the Changing Distribution of Net Value Added in Large German Firms.” Economy and Society 31 (3): 309–332.

- Beyer, Jürgen, and Martin Höpner. 2003. “The Disintegration of Organised Capitalism: German Corporate Governance in the 1990s.” West European Politics 26 (4): 179–198.

- Bezemer, Dirk J. 2016. “Towards an ‘Accounting View’ on Money, Banking and the Macroeconomy: History, Empirics, Theory.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 40 (5): 1275–1295. doi:10.1093/cje/bew035.

- Bezemer, Dirk J., Anna Samarina, and Lu Zhang. 2017. The Shift in Bank Credit Allocation: New Data and New Findings. Amsterdam: De Nederlandsche Bank.

- Blyth, Mark, and Matthias Matthijs. 2017. “Black Swans, Lame Ducks, and the Mystery of IPE's Missing Macroeconomy.” Review of International Political Economy 24 (2): 203–231.

- Braun, Benjamin. 2016. “From Performativity to Political Economy: Index Investing, ETFs and Asset Manager Capitalism.” New Political Economy 21 (3): 257–273. doi:10.1080/13563467.2016.1094045.

- Braun, Benjamin, and Marina Hübner. 2018. “Fiscal Fault, Financial fix? Capital Markets Union and the Quest for Macroeconomic Stabilization in the Euro Area.” Competition & Change 22 (2): 117–138.

- Bundesbank. 2017. “The Performance of German Credit Institutions in 2016.” Monthly Report, Serptember, 51–85.

- Chen, Peter, Loukas Karabarbounis, and Brent Neiman. 2017. “The Global Rise of Corporate Saving.” Journal of Monetary Economics 89: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.jmoneco.2017.03.004.

- Culpepper, Pepper D. 2005. “Institutional Change in Contemporary Capitalism: Coordinated Financial Systems Since 1990.” World Politics 57 (2): 173–199. doi:10.1353/wp.2005.0016.

- Deeg, Richard. 1999. Finance Capitalism Unveiled: Banks and the German Political Economy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Deeg, Richard. 2005. “Change From Within: German and Italian Finance in the 1990s.” In Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies, edited by Wolfgang Streeck, and Kathleen Thelen, 169–202. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deeg, Richard. 2009. “The Rise of Internal Capitalist Diversity? Changing Patterns of Finance and Corporate Governance in Europe.” Economy and Society 38 (4): 552–579.

- Deeg, Richard, and Iain Hardie. 2016. “What is Patient Capital and who Supplies it?” Socio-Economic Review 14 (4): 627–645. doi:10.1093/ser/mww025.

- De Jong, Henk Wouter. 1997. “The Governance Structure and Performance of Large European Corporations.” Journal of Management & Governance 1 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1023/a:1009931211940.

- De Ville, Ferdi. 2018. “Domestic Institutions and Global Value Chains: Offshoring in Germany’s Core Industrial Sectors.” Global Policy 9 (S2): 12–20. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12610.

- Di Carlo, Donato. 2018. “Does Pattern Bargaining Explain Wage Restraint in the German Public Sector?” MPIfG Discussion Paper 18/3. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- ECB. 2017. Report on Financial Structures. Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

- ECB. 2018. “Harmonised Competitiveness Indicators Based on Unit Labour Costs Indices for the Total Economy.” Accessed September 20, 2018. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/ecb_statistics/escb/html/table.en.html?id=JDF_EXR_HCI_ULCT.

- Edwards, Jeremy, and Klaus Fischer. 1996. Banks, Finance and Investment in Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ergen, Timur. 2015. Große Hoffnungen und brüchige Koalitionen: Industrie, Politik und die schwierige Durchsetzung der Photovoltaik. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

- Faust, Michael. 2017. “A Typology of Shareholders and Constellations of Actors in the External Coalition of the Corporation. An Exploration for the German Case.” Paper submitted to EGOS 2017 Sub-theme 20: Financialization and its Societal Implications: Rethinking Corporate Governance and Shareholders. Copenhagen.

- Ferrando, Annalisa, and Alessandro Ruggieri. 2018. “Financial Constraints and Productivity: Evidence From Euro Area Companies.” International Journal of Finance & Economics 23 (3): 257–282. doi:10.1002/ijfe.1615.

- Fichtner, Jan, Eelke M. Heemskerk, and Javier Garcia-Bernardo. 2017. “Hidden Power of the Big Three? Passive Index Funds, Re-Concentration of Corporate Ownership, and New Financial Risk.” Business and Politics 19 (2): 298–326. doi:10.1017/bap.2017.6.

- Fuller, Gregory W. 2018. “Exporting Assets: EMU and the Financial Drivers of European Macroeconomic Imbalances.” New Political Economy 23 (2): 174–191. doi:10.1080/13563467.2017.1370444.

- Glötzl, Florentin, and Armon Rezai. 2018. “A Sectoral Net Lending Perspective on Europe.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 42 (3): 779–795. doi:10.1093/cje/bex047.

- Goldschmidt, Deborah, and Johannes F. Schmieder. 2017. “The Rise of Domestic Outsourcing and the Evolution of the German Wage Structure*.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (3): 1165–1217. doi:10.1093/qje/qjx008.

- Grittersová, Jana. 2014. “Non-market Cooperation and the Variety of Finance Capitalism in Advanced Democracies.” Review of International Political Economy 21 (2): 339–371.

- Hall, Peter A. 2017. “Varieties of Capitalism in Light of the Euro Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1): 7–30. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1310278.

- Hall, Peter A., and David Soskice. 2001. “An Introduction to Varieties of Capitalism.” In Varieties of Capitalism. The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage, edited by Peter A. Hall, and David Soskice, 1–68. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hallerberg, Mark, and Jonas Markgraf. 2018. “The Corporate Governance of Public Banks Before and After the Global Financial Crisis.” Global Policy 9 (Supplement 1): 43–53.

- Hardie, Iain, David Howarth, Sylvia Maxfield, and Amy Verdun. 2013a. “Banks and the False Dichotomy in the Comparative Political Economy of Finance.” World Politics 65 (4): 691–728.

- Hardie, Iain, David Howarth, Sylvia Maxfield, and Amy Verdun. 2013b. “Introduction: Towards a Political Economy of Banking.” In Market-based Banking and the International Financial Crisis, edited by Iain Hardie, and David Howarth, 1–21. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hassel, Anke. 2014. “The Paradox of Liberalization: Understanding Dualism and the Recovery of the German Political Economy.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 52 (1): 57–81.

- Hassel, Anke. 2017. “No way to Escape Imbalances in the Eurozone? Three Sources for Germany’s Export Dependency: Industrial Relations, Social Insurance and Fiscal Federalism.” German Politics 26 (3): 360–379.

- Höpner, Martin. 2003. Wer beherrscht die Unternehmen? Shareholder Value, Managerherrschaft und Mitbestimmung in Deutschland. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Höpner, Martin. 2019. The German Undervaluation Regime Under Bretton Woods: How Germany Became the Nightmare of the World Economy. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- Höpner, Martin, and Mark Lutter. 2018. “The Diversity of Wage Regimes: Why the Eurozone is too Heterogeneous for the Euro.” European Political Science Review 10 (1): 71–96. doi:10.1017/S1755773916000217.

- Hübner, Marina. forthcoming. Wenn der Markt Regiert: Die Politische Ökonomie der Europäischen Kapitalmarktunion. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Johnston, Alison, Bob Hancké, and Suman Pant. 2014. “Comparative Institutional Advantage in the European Sovereign Debt Crisis.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (13): 1771–1800. doi:10.1177/0010414013516917.

- Johnston, Alison, and Aidan Regan. 2016. “European Monetary Integration and the Incompatibility of National Varieties of Capitalism.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54 (2): 318–336. doi:10.1111/jcms.12289.

- Jordà, Òscar, Moritz Schularick, and Alan M. Taylor. 2016. “The Great Mortgaging: Housing Finance, Crises and Business Cycles.” Economic Policy 31 (85): 107–152. doi:10.1093/epolic/eiv017.

- Keller, Eileen. 2018. “Noisy Business Politics: Lobbying Strategies and Business Influence After the Financial Crisis.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (3): 287–306. doi:10.1080/13501763.2016.1249013.

- KfW. 2018. Hohe Eigenkapitalquoten im Mittelstand: KMU schätzen ihre Unabhängigkeit. Frankfurt am Main: Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau.

- Lane, Philip R., and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti. 2007. “The External Wealth of Nations Mark II: Revised and Extended Estimates of Foreign Assets and Liabilities, 1970–2004.” Journal of International Economics 73 (2): 223–250. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2007.02.003.

- Massoc, Elsa. 2019. “Banks, Power, and Political Institutions: the Divergent Priorities of European States Towards “Too-big-to-fail” Banks: The Cases of Competition in Retail Banking and the Banking Structural Reform.” Business and Politics, Advance Online Publication.

- May, Christian, and Andreas Nölke. 2018. “The Delusion of the Global Corporation: Introduction to the Handbook.” In Handbook of the International Political Economy of the Corporation, edited by Christian May, and Andreas Nölke, 1–25. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Mertens, Daniel. 2015. Erst sparen, dann kaufen? Privatverschuldung in Deutschland. Vol. 82. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Mertens, Daniel. 2017. “Putting ‘Merchants of Debt’in Their Place: the Political Economy of Retail Banking and Credit-based Financialisation in Germany.” New Political Economy 22 (1): 12–30.

- Mody, Ashoka. 2018. Eurotragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Naqvi, Natalya, Anne Henow, and Ha-Joon Chang. 2018. “Kicking Away the Financial Ladder? German Development Banking Under Economic Globalisation.” Review of International Political Economy 25 (5): 672–698. doi:10.1080/09692290.2018.1480515.

- Palier, Bruno, and Kathleen Thelen. 2010. “Institutionalizing Dualism: Complementarities and Change in France and Germany.” Politics & Society 38 (1): 119–148. doi:10.1177/0032329209357888.

- Redeker, Nils. 2019. The Politics of Stashing Wealth: The Demise of Labor Power and the Global Rise of Corporate Savings. Zürich: Center for Comparative and International Studies.

- Regan, Aidan. 2017. “The Imbalance of Capitalisms in the Eurozone: Can the North and South of Europe Converge?” Comparative European Politics 15 (6): 969–990. doi:10.1057/cep.2015.5.

- Reurink, Arjan, and Javier Garcia-Bernardo. 2019. Competing with Whom? European Tax Competition, the “Great Fragmentation of the Firm,” and Varieties of FDI Attraction Profiles. MPIfG Discussion Paper 19/9. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- Ryan, Robert M., Conor M. O’Toole, and Fergal McCann. 2014. “Does Bank Market Power Affect SME Financing Constraints?” Journal of Banking & Finance 49 (Supplement C): 495–505. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.12.024.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. 2018. International Monetary Regimes and the German Model. Cologne: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

- Schwan, Michael. 2019. “Still an Alternative? German Savings Banks in the Era of Financialization.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Sigl-Glöckner, Philippa. 2018. “Euro Area Financial System Explorer.” Accessed March 8, 2019. http://philippasigl.com/WhomToWhom/templates/.

- Stockhammer, Engelbert. 2016. “Neoliberal Growth Models, Monetary Union and the Euro Crisis. A Post-Keynesian Perspective.” New Political Economy 21 (4): 365–379. doi:10.1080/13563467.2016.1115826.

- Stockhammer, Engelbert, Cédric Durand, and Ludwig List. 2016. “European Growth Models and Working Class Restructuring: An International Post-Keynesian Political Economy Perspective.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48 (9): 1804–1828.

- Storm, Servaas, and C. W. M. Naastepad. 2015. “Crisis and Recovery in the German Economy: The Real Lessons.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 32: 11–24.

- Streeck, Wolfgang. 2009. Re-forming Capitalism: Institutional Change in the German Political Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vitols, Sigurt. 2001. “The Origins of Bank-Based and Market-Based Financial Systems: Germany, Japan, and the United States.” In The Origins of Nonliberal Capitalism: Germany and Japan in Comparison, edited by Wolfgang Streeck, and Kōzō Yamamura, 171–199. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Zysman, John. 1983. Governments, Markets, and Growth: Financial Systems and the Politics of Industrial Change. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.