?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper compares the evolution of critical characteristics of the party systems in Eastern and Western Germany since unification. While the institutionalisation hypothesis implies that the party system in Eastern Germany should adjust towards its Western German counterpart, the ongoing dealignment suggests a loosening of party-voter-linkages and, ultimately, non-institutionalisation in Eastern Germany and party system de-institutionalisation in Western Germany. However, both hypotheses predict a convergence. Against the backdrop of persisting regional differences in party strengths, a third hypothesis assumes that Eastern and Western Germany still have two distinct party systems thirty years after reunification. Using election results and survey data since the 1990s, we inspect the development of five indicators of party systems – volatility, vote-switching, electoral availability, fragmentation, and differences in vote shares – in light of the hypotheses. There are three main results: First, most of the indicators point to party system institutionalisation in Eastern Germany and convergence to Western Germany in the 1990s. Second, for the last 20 years or so, the indicators point to parallel developments of dealignment and partial party system de-institutionalisation. Third, regarding the specific parties and their vote shares, there has been no convergence between Eastern and Western Germany.

Introduction

Eighty years ago, Schattschneider (Citation1942, 53) apodictically stated that ‘(…) modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the parties.’ Without competing parties, citizens lack meaningful choices. Meaningful choices, however, are a precondition for functioning political representation (Wessels and Schmitt Citation2008). The plural – parties – refers to the necessity of a party system, not just a single party. Mair (Citation2015, 567) defines a party system as ‘the system of interactions between political parties that results from their mutual competition or cooperation’. Its critical elements can be sorted into two groups – numerical properties like the number of competitors, the fragmentation and the volatility of the party system and substantive properties which refers to the policy issues and policy dimensions on which politicians compete and try to win electoral support (Kitschelt Citation2013, 619f.; Niedermayer Citation2013).

Comparisons of party systems and their degree of institutionalisation usually focus on numerical elements, in particular on fragmentation, social anchoring, and stability (Casal Bértoa Citation2018). For comparisons within a country, e.g. over time or between different regions, one can add an additional perspective and ask whether the relevant parties are identical, or whether the party system is nationalised (Caramani Citation2012). In this paper, we compare the evolution of critical characteristics of the party systems in Eastern and Western Germany at the federal level since unification.

Three hypotheses guide the study. First, according to the institutionalisation hypothesis, voters should have found their ideological or party-political home after a period of orientation; an initially higher fluidity and fragmentation in Eastern Germany should therefore, over time, adjust towards the (lower) level of Western Germany. Parallel to this (presumed) institutionalisation process of electoral democracy in Eastern Germany, the last decades have also been characterised by a loosening of linkages between citizens and parties in the established democracies of Western Europe. The descriptive hypothesis of ‘asymmetric convergence’ (Emanuele, Chiaramonte, and Soare Citation2020) with a convergence of Eastern to Western Germany is challenged by a second descriptive convergence hypothesis, which, however, assumes that the formerly more stable party system of Western Germany has become de-institutionalised and thus more similar to Eastern Germany’s party system (convergence thesis Western to Eastern Germany). In contrast to these two convergence hypotheses, however, a difference hypothesis is also plausible: against the backdrop of regional differences in party strengths, the question is whether East and West still have two distinct party systems thirty years after unification.

In the next section, we will develop the argument and present the three hypotheses. Section three gives an overview over the operationalisation and data basis. Subsequently we will explain the five indicators used – volatility, vote-switching, electoral availability, fragmentation and the differences in vote shares – and inspect the results in the light of the hypotheses. Some indicators point to a rather short period of party system institutionalisation in Eastern Germany and convergence to the level in Western Germany after 1990. For the last 20 years or so, however, most indicators point to parallel developments of dealignment or even party system de-institutionalisation. Then again, with regard to the specific parties and their vote shares, there has been no convergence between Eastern and Western Germany. A conclusion discusses these findings in view of the question regarding the development and current state of the German party system(s).

Party Systems in Eastern and Western Germany – Three Hypotheses

After reunification, there were two notable developments. First, the institutions of the pre-1989 Federal Republic were transferred to the new federal states. Second, the parties and the party system were also largely adapted from Western to Eastern Germany. Thus, after the merger of Bündnis 90 and the West German Greens, the East essentially had the same parties as Western Germany, with the exception of the PDS. One could therefore expect that, in the coming years, the Eastern German party system – especially the political competition between the parties, its stability, and the parties’ vote shares– would come to resemble the Western German party system. Thus, according to this thesis, following a transformation and adjustment phase, the SPD and CDU as the major centre-left and centre-right parties would also become the most relevant partisan actors in Eastern Germany, dominating politics in coalition constellations similar to those in the West. The party system in the eastern federal states would become ‘an extension of the party system from the West (with the addition of the PDS)’ (Dalton and Jou Citation2010, 35).

These assumptions and expectations about party system stabilisation and voter alignment are based on findings from comparative party system research. Party systems in young or new democracies develop a stable programmatic basis after a couple of elections. Initially, the parties and party systems are not programmatically oriented; they also tend to be weak and locally oriented. Only later do the parties develop a stronger programmatic and nation-wide orientation. Weßels and Klingemann (Citation2006) found that after the democratisation of 1990, programmatic competition emerged in the party systems in Central Eastern Europe over time. Tavits (Citation2005) observed that volatility initially increases after regime change. She also observed that it took about a decade for this trend to reverse and the volatility of the party system to decrease.

The underlying mechanism is the institutionalisation of the party system. Institutionalisation consists of the genesis of partisanship, the decline of electoral openness of the voters and the stabilisation of the dimensions and patterns of political competition (Dalton and Weldon Citation2007). Previous studies primarily analysed partisanship and volatility (Mainwaring and Mariano Citation2006; Brader and Tucker Citation2008). Electoral openness of the citizens or, from the perspective of campaigning parties, the availability of votes, has been less analysed in depth so far. If party system institutionalisation consists of emerging partisanship and individual-level party identification, this process implies that citizens find a partisan home and stable party-voter alignments come about. Wagner (Citation2017) showed that partisans are less open to other parties. Thus, an institutionalised party system corresponds to lower levels of availability in the electorate. In the German case, this party system institutionalisation is particularly plausible for the reasons mentioned above referring to the transfer of Western German political institutions and the most relevant actors – the political parties. Accordingly, we would expect a convergence of Eastern and Western Germany. More precisely, this perspective implies an asymmetric convergence (Emanuele, Chiaramonte, and Soare Citation2020), since the two regions are not expected to equally move towards each other. Rather, the party system of one part of the country converges to the other part.

However, from the perspective of international party system research, German reunification took place in turbulent times. Two aspects are particularly important here. First, together with globalisation and Europeanisation, the change in the dimensionality of the political space is relevant: after decades in which the ‘old’, socioeconomically oriented left-right axis was dominant, the hitherto secondary axis of competition gained relevance. This was connected to the shift in values in Western societies following the 1960s (Inglehart Citation1990). This axis is less concerned with state intervention in the economy or with questions about the level of taxes and the extent of redistribution and the welfare state. Rather, it refers to the confrontation between the Green-Alternative-Libertarian and Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist poles (Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Citation2002). This dimension also encompasses the issues of internationalisation, globalisation and Europeanisation (Kriesi et al. Citation2008).

This shift has changed the structure of political competition: the parties now compete in a two-dimensional policy space (Dalton Citation2018; Kitschelt Citation1994; Rovny and Whitefield Citation2019). Second (although not unrelated to the first point), German reunification occurred at a time of increasing dealignment, the loosening of ties between citizens and parties (cf., e.g. Franklin, Mackie, and Valen Citation1992). Increasing individualisation and the decline of traditional cleavages, including the declining relevance of the supporting organisations (especially churches, trade unions, etc.), are associated with the weakening of citizens’ socio-psychological ties to political parties. This results in an increase in vote-switching and a higher volatility on the party system level. Therefore, some researchers speak of a de-institutionalisation of party systems in European democracies in recent decades (Chiaramonte and Emanuele Citation2017, Citation2019; see also Hebenstreit this issue).

(Western) Germany is no exception in this respect: For example, the proportion of citizens with party identification has declined in recent decades (Dalton Citation2014) and partisan dealignment has progressed, which has resulted in a decline in linkages between parties and citizens. Instead of, or in addition to, the conversion of the Eastern German party system, the Western German party system would consequently become more unstable and converge toward the Eastern German party system in terms of stability and fragmentation. We would also observe asymmetric convergence, but in the inverse direction: instead of Eastern Germany becoming more similar to Western Germany, we would observe the opposite – Western Germany would become more like Eastern Germany, analogously to what has been observed in comparisons of Western and Eastern Europe (Emanuele, Chiaramonte, and Soare Citation2020).Footnote1

Thus, two contrary developments are plausible: on the one hand, we might expect the Eastern German party system to develop into a replica of the Western German party system. Accordingly, stable partisanship develops in the Eastern Länder, the patterns of competition between the parties converge, voters find their political and partisan identity and are become less open to other parties. Based on the results of comparative research, we can, however, assume that party ties have loosened in Western democracies in recent decades, that new patterns of political competition have been established, and that voters have become more open to a variety of parties. If this assumption holds, the expected alignment in Eastern Germany – the creation of ties between citizens and parties and (also) the resulting convergence of the Eastern German party system with the Western German party system – would fail to materialise, as the expected alignment would enter a phase of general dealignment. According to this view, the Western German party system would undergo a similar trend and resemble its Eastern German counterpart.

Both scenarios assume convergence. However, there is another possibility, namely that the differences between party systems in Eastern and Western Germany remained even after the first years after reunification (Birsl and Lösche Citation1998) and that a ‘regionally differentiated transfer of the West German party system’ occurred (Saalfeld Citation2002, 126; also see Jörs Citation2003).

Even three decades after reunification, the assumption of no-convergence between Western and Eastern Germany seems justified. For example, research on political culture suggests that the different experiences in the political socialisation phase may have led to lasting differences in Eastern and Western Germany (socialisation hypothesis; see, for example, Finkel, Humphries, and Opp Citation2001; Gabriel Citation2007; see also Pickel and Pickel this issue). This enduring-differences hypothesis is also plausible in light of the debate about the strongly differing successes of certain parties in Eastern or Western Germany (Pappi and Brandenburg Citation2010; Abedi Citation2017, Arzheimer forthcoming). The different electoral successes of parties in Eastern and Western Germany and the persistence of these differences – driven primarily by the strength of the Left and the AfD in Eastern Germany and the weakness of the mainstream parties as well as Bündnis 90/Die Grünen and the FDP – imply the existence of two different party systems. Should this apply, a different party system than in Western Germany may have been institutionalised in Eastern Germany and/or fragmentation may continue to be higher in the East.

In the following, we will empirically examine this tension between the three possible paths of development: the (expected) institutionalisation of an Eastern German party system along Western German lines at a time of de-institutionalisation of West European party systems, and the possible consequences for convergence and difference. Following this perspective, this paper examines the three descriptive hypotheses suggesting party system shifts in both Eastern and Western Germany since 1990:

H1: After a decade of transition, the party system in Eastern Germany institutionalises along Western German lines: Party-voter linkages stabilise, fragmentation decreases, and party diversity and strengths correspond to those in Western Germany (convergence hypothesis I).

H2: Party system de-institutionalisation takes place in Western Germany. Thus, the Western German party system converges with and resembles the Eastern German party system: party-voter linkages dissolve, fragmentation increases, and party diversity and strengths correspond to those in the East (convergence hypothesis II).

H3: Party systems in Eastern and Western Germany remain different. The institutionalised party system in Western Germany is characterised by stronger party-voter linkages and less fragmentation, and the vote shares of the parties differ.

Specifically, these hypotheses are less concerned with providing explanations at the substantive level of party systems (Niedermayer Citation2013) – for instance, relating to party positions (see also Hebenstreit this issue). Results concerning the substantive characteristics of party systems and their development can be found in studies such as Bräuninger et al. (Citation2020). In contrast, the hypotheses presented here refer to the numerical properties of party systems. They are not deduced from a standing body of theory but represent three equally plausible developments of the party system(s) in Germany since reunification. To address these hypotheses, we first empirically analyse the macro-level of party systems in Eastern and Western Germany: we look at the vote shares of the relevant parties and their volatility, fragmentation, and East-West deviations over time. Second, going beyond existing analyses of party system institutionalisation, we compare vote-switching behaviour as well as the underlying electoral openness of voter markets, i.e. the availability of votes in the last 30 years. These latter two indicators are aggregated micro-level indicators. The operationalisation as well as the advantages and disadvantages of each of the indicators will be discussed in the next section.

According to the first hypothesis (party system institutionalisation), we expect volatility, the share of vote switchers, and the electoral availability of the electorate in Eastern Germany to decrease and to adjust to the (lower) levels of Western Germany. The same is true for fragmentation: Hypothesis 1 would lead us to expect a decrease in fragmentation, volatility, vote-switching, and availability in Eastern Germany. Furthermore, we expect to see a decrease in vote share differences between Eastern and Western Germany. In accordance with Hypothesis 2 (party system de-institutionalisation) volatility, vote-switching, electoral availability, and fragmentation should increase in Western Germany leading to a convergence of the levels in Western Germany to Eastern Germany. Vote share differences, however, are also expected to decrease. Hypothesis 3 (differences) suggests (a stability in the) differences in all five indicators – the differences from the early 1990s are expected to endure. It is noteworthy to emphasise that these three hypotheses do not make any normative claims about the indicators. The question of whether an increase or decrease in, e.g. fragmentation or availability itself facilitates representation or the quality of democracy is beyond the scope of this article (but see Bartolini 2002 for a discussion). summarises the hypotheses.

Table 1. Hypotheses

By looking at all five indicators, we aim to provide new perspectives and answers to the question of the convergence of party systems in Eastern and Western Germany almost 30 years after reunification.

Data and Operationalisation

In this analysis of the party system change in Germany since reunification, we rely on five measures: volatility, vote-switching, availability, fragmentation, and vote share difference. The first three indicators are logically connected but still point to different aspects of a (potential) party system (de-)institutionalisation. Volatility is the most used indicator for stability in studies on party system institutionalisation (Casal Bértoa Citation2018). To measure electoral volatility, we use the formula proposed by Pedersen (Citation1979):

where i stands for parties, p denotes a party’s vote share, and t indicates elections. Our data source is the Bundeswahlleiter (Citation2018). Volatility equals the net change in the parties’ vote shares between two consecutive elections (Bartolini and Mair Citation1990).

Sometimes, however, volatility hides the true level of instability of a party system. As Wagner and Krause (Citation2021) argue, vote-switching is a necessary but not sufficient condition of volatility. This implies that high levels of volatility are always associated with high levels of vote-switching – if a party system is very volatile voters are obviously not very strongly tied to the political parties. But the opposite is not necessarily true. We cannot infer an institutionalised party system and low levels of vote-switching from observing low levels of volatility. If 100 voters of party A switch to party B and 100 voters of party B switch to party A, the net volatility equals zero. The result of many switching voters would be the same as if all voters stayed with their former party. Consequently, according to the volatility measure there is party system stability although vote transfers point to a complete shift on the level of individual behaviour.

Voters whose retrospective and prospective vote choices differ are considered vote switchers ( = 1), and those with the same party choice in the last parliamentary elections for the Bundestag are considered non-switchers ( = 0).Footnote2 For each election, the mean for Eastern and Western Germany is calculated (equalling the share of switchers). To obtain this information, we rely on different sources. We used data from the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES) to calculate the values for 2017 and 2013 (Rattinger et al. Citation2017; Roßteutscher et al. Citation2018). For the elections 1994–2009 we relied on estimations presented in reputable German academic publications.Footnote3

Van der Eijk and Oppenhuis (Citation1991) even go one step further and suggest focusing on potential behaviour. Discussing the concept of electoral competition, they recommend analysing the voters’ inclination to vote for multiple parties (see also Wagner Citation2017). This argument can be transferred to the analysis of party systems: Even in situations of similarly low levels of vote-switching there may be variance in the levels of the voters’ openness to multiple parties, i.e. the availability of the electorate. Consequently, availability is a necessary but not sufficient condition for vote-switching: only if many voters are available to a plurality of political parties, high levels of vote-switching can occur. But even if there is a higher level of availability, this does not automatically translate into higher levels of switching – maybe only a fraction of the available voters change their party choice (cf. Wagner and Krause Citation2021). Availability, then, represents the attitudes beneath the electoral behaviour, the roots of observable vote-switching. Availability points to the inclination of voters, vote-switching represents the actual behaviour, and volatility represents the net effect for the strengths of the political parties in parliament.

To measure individual-level availability, we use an operationalisation proposed by Wagner (Citation2017). According to him, a measure of an individual’s availability on the electoral market must meet certain criteria. First, if a citizen is similarly inclined to vote for different parties – i.e. if she has similar Propensities to Vote (PTVs)Footnote4 for various parties – her availability is higher, as she is undecided about who to vote for. This voter is therefore approachable for different parties. Second, as the voters can cast a vote for only one party in elections for the German Bundestag (the decisive second vote), the measure should consider the differences of the PTVs of all parties to the most preferred party. Third, higher levels of individual PTVs imply a higher availability of an individual’s vote. Thus, the higher the respective PTVs, the higher the availability (if and

the availability score is higher than if

and

).

Satisfying these criteria, individual electoral availability calculates as follows:

where

denotes voters,

stands for the propensity to vote for party i and

refers to the party the person has the highest inclination to vote for.

denotes the number of parties. The measure ranges from 0 (available to only one party) to

(equally available to all parties in the party system; cf. Wagner and Krause Citation2021 for further discussion and a comparative application).Footnote5 The data source for the Propensity to Vote survey items are the European Parliament Election Study Voter Surveys (Schmitt et al. Citation1997; Citation2015; Citation2020; Van der Eijk et al. Citation1999; Van Egmond et al. Citation2013).Footnote6

For fragmentation, we calculated the effective number of electoral parties (ENEP) based on the election results (vote shares provided by the Bundeswahlleiter (Citation2018)). The formula proposed by Laakso and Taagepera (Citation1979) reads:

where, again, i stands for parties,

denotes a party’s vote share, and t indicates elections.

The Difference Score between the vote shares in East and West represents the different party strengths of the parties in the Bundestag. It is calculated as:

with, again, i for the parties in the Bundestag,

for a party’s vote share (in East and West, respectively), and t for elections. We will now turn to the empirical findings regarding these five indicators in Eastern and Western Germany since 1990.

Empirical Findings

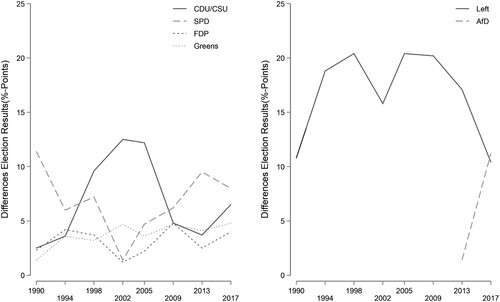

shows the first measure of party system institutionalisation, volatility. It corresponds to the change in the parties’ vote shares in a federal election compared to the previous election. Evidently, volatility in Eastern Germany decreases in the first ten years or so after reunification. The parties’ vote shares thus changed less from election to election, and the party system stabilised. This can be read as a sign for institutionalisation. A comparison with Western Germany shows a convergence. In the 2002 federal election, volatility in Eastern Germany was almost at the same low level as in Western Germany, where it had remained largely constant since 1990. This development speaks in favor of the hypothesis of party system institutionalisation and convergence after about ten years.

Figure 1. Volatility in Eastern and Western Germany, 1994–2017. Data Source: Bundeswahlleiter (Citation2018).

The second period from 2002 to 2013 is characterised by an increase in volatility in both regions. In Eastern Germany, volatility once again rises to above 10 as early as 2005, while in Western Germany it does so in the 2009 election. The differences between Eastern and Western Germany were small in 2009 and 2013. The increase in volatility, which is similar in both parts of the country, speaks in favour of the hypothesis of convergence in dealignment, for a similar degree of institutionalisation of the party systems that are changing at the same pace.

In 2017, however, things changed. While volatility increased only slightly in Western Germany, it reached an all-time high (over 20) in Eastern Germany. The party system in Eastern Germany is thus undergoing greater change than that in Western Germany and shows stronger tendencies toward de-institutionalisation. The difference line also shows that while the first period is in line with the first hypothesis (institutionalisation) and convergence, the course of the second period is more in line with the second hypothesis of joint dealignment and parallel development. The third period is more in line with the expectation formulated in the third hypothesis of a difference between Eastern and Western Germany – the difference line once again rises for the 2017 federal election.

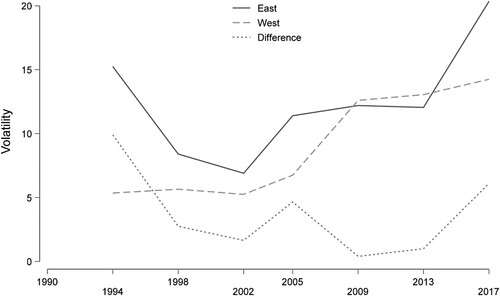

The findings are similarly heterogeneous regarding vote-switching (cf. ). In the 1990s, the share of those who said they voted for a different party in the last election than in the current election was higher in Eastern Germany (solid line) than in Western Germany (dashed line). Since 2002, however, the proportion of vote switchers has been increasing in both regions. In the 1990s, the share of vote switchers in Western Germany was still about a quarter; in the 2000s, it rose to about 30 percent in both Eastern and Western Germany, and in the last federal election it reached more than 40 percent. The gap between the different regions narrowed slightly over time.

Figure 2. Vote-switching in Eastern and Western Germany, 1994–2017. Data Source: Schmitt et al. (Citation1997, Citation2015; Citation2020); Van der Eijk et al. (Citation1999); Van Egmond et al. (Citation2013).

Again, these results do not support any of the hypotheses entirely. While the 1990s is mostly in line with the institutionalisation hypothesis – the share of vote switchers in Eastern Germany is approaching the lower level of vote-switching in Western Germany – the development since 2002 is in accordance with the dealignment hypothesis. The data does not support the difference hypothesis. Rather, the uniform trend in Eastern and Western Germany is noteworthy given the differences in volatility in 2017 mentioned before. Although the share of vote switchers was about the same in both regions in 2017, they cancel out to a greater extent in Western than in Eastern Germany (due to two-way flows of voters). Thus, even in the Western German party system, voters often switch parties; it simply does not translate to the same extent into net changes in vote shares. These differences between the measures highlight the usefulness of examining more than just volatility – it is worthwhile looking at the behavioural level.

Regarding the hypotheses, two findings are especially noteworthy. In the first years after reunification, the data is in line with the institutionalisation hypothesis and a convergence of Eastern and Western Germany. In the period that followed, we observe a co-evolution in line with the de-institutionalisation and dealignment hypotheses.

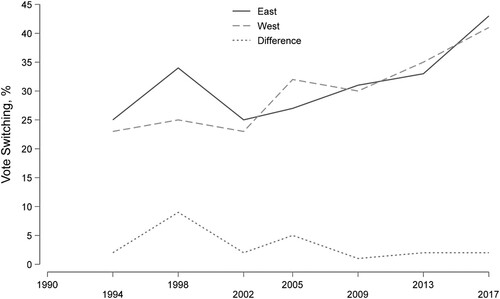

In a third step, we examine whether behavioural intentions and inclinations also follow the developments described. Therefore, we look at the development of electoral availability in Eastern and Western Germany since reunification. As described above, this measure of electoral availability depicts the openness or inclination of voters to vote for different parties. It is based on the so-called Propensity to Vote (PTV) survey items and represents the number of parties the average citizen is open to or, put differently, to how many parties her vote is available. If a voter leans similarly towards a plurality of parties, her vote is available on the electoral market. If, on the other hand, a person considers only one party as eligible and does not view any other party as a potential voting option, her vote is not available, it is beyond competition. As this measure is based on survey data from the European Election Studies (Voter Surveys), data points refer to the European Elections between 1994 and 2019.

As shows, the electorates in the Eastern (dashed line) and Western (solid line) have become more available since the late 1990s, with voters less tied to their highest-preference party and more open to other parties. In the last two decades, availability increased significantly and was over one-third higher in 2019 than in the 1990s. Again, the differences between the two regions of the country hardly matter and are not statistically significant in any year. There has never been a relevant difference between the availability of voters in Eastern and Western Germany since reunification. The comparison of and shows that in the 1990s, West Germans, given the same level of availability to multiple parties as East Germans, were more likely to stay with their previously elected party, resulting in lower levels of vote-switching.

Figure 3. Electoral Availability in Eastern and Western Germany, 1994–2019. Data Source: Schmitt et al. (Citation1997, Citation2015; Citation2020); Van der Eijk et al. (Citation1999); Van Egmond et al. (Citation2013).

The findings for volatility and vote-switching show a convergence of East and West until around the year 2000. This speaks mainly in favour of Tavits’ thesis of the institutionalisation of young party systems within about ten years and for our first hypothesis. Since the 2000s, we observe an increase in availability, vote-switching, and volatility in Eastern and Western Germany. Only volatility differed again in 2017. Thus, the findings speak in favour of the first two descriptive hypotheses: In the 1990s, the Eastern German party system became institutionalised and thus aligned with the Western German party system. This applies above all to volatility and vote-switching. Availability was already similarly high in the 1990s in Eastern and Western Germany but did not equally translate into vote-switching. Voters’ ties to a party had therefore already become weaker in Western Germany in the 1990s as well. For about 20 years, all three indicators of party system de-institutionalisation have been increasing – again quite similarly in both regions.

Additionally, show the added value of analysing vote-switching and availability besides looking at volatility. Only the analysis of availability shows that the potential for party system de-institutionalisation has been just as great in Western as in Eastern Germany since the 1900s; there have never been any relevant differences since reunification. For vote-switching, a convergence of Western and Eastern Germany took place. However, the changes in volatility in Eastern Germany are greater, and the differences follow a U-shape: from greater differences to similarities to once again greater differences.

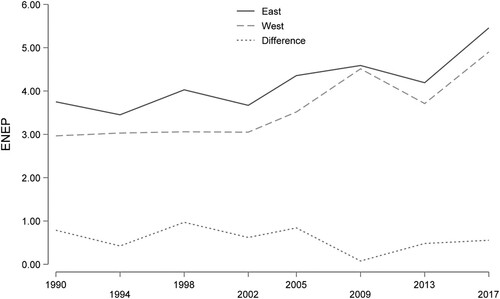

The increase in electoral availability in both parts of the country correlates with an increase in fragmentation. Fragmentation – measured as the effective number of electoral parties (ENEP), i.e. the inverse of the sum of squared vote shares – is shown in For Western Germany (dashed line), there is again largely stability up to 2002 at a lower level than in Eastern Germany (solid line). In Eastern Germany, the party system was always larger – up to one ‘effective’ party – without any convergence taking place. There was no party system concentration as in the early days of the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1950s and 1960s. After 2002, the ENEP values converged. Furthermore, fragmentation has increased in both regions by 2017, reaching an all-time high for the FRG. The findings thus argue against the first hypothesis of institutionalisation and in favour of the second hypothesis (dealignment). Moreover, we see no support for the third hypothesis in the development of electoral fragmentation (persistent differences between Eastern and Western Germany).

Figure 4. Effective Number of Electoral Parties in Eastern and Western Germany, 1994–2019. Data Source: Bundeswahlleiter Citation2018.

Taken together, the indicators show stability in Western Germany until the year 2002, while the values for Eastern Germany show an asymmetric convergence. In Western Germany, however, the potential for change is already present in the 1990s in the form of a similarly high electoral availability as in Eastern Germany. Since the beginning of the millennium, tendencies toward de-institutionalisation in Western Germany became obvious. Once again, asymmetric convergence occurs, but this time the Western German party system becomes more similar to its Eastern German counterpart. Additionally, the indicators point to a co-evolution: In both regions, the proportion of vote switchers as well as fragmentation increase, and the electorates became even more available.

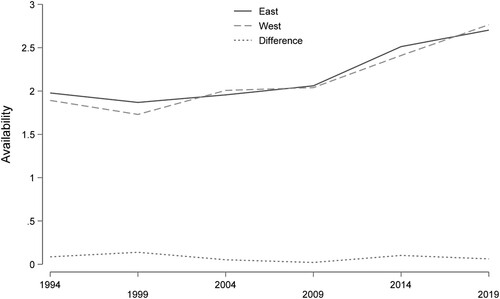

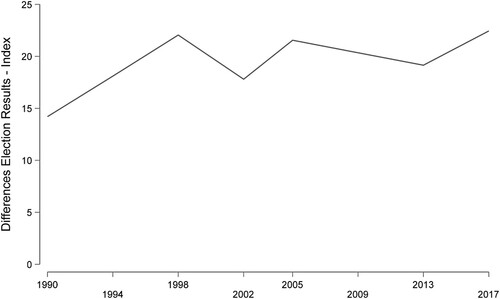

However, similarly high volatility, comparable proportions of vote switchers and available voters and a similar fragmentation of the party system do not necessarily imply identical party systems. It is true that the relevant parties at the federal level are the same in both Eastern and Western Germany. In order to examine whether the German party system in East and West can indeed be said to be converging with subsequent co-evolution, the last necessary step is to examine the differences in the vote shares of the parties in the Bundestag. shows the dissimilarity index, which is calculated as the absolute sum of the differences in the vote shares of the parties in the Bundestag in Eastern and Western Germany divided by two. Contrary to the expectation of the convergence hypotheses H1 and H2, the dissimilarity of party strengths increases until 1998 and, after a one-time drop in 2002, fluctuates at about 20per cent. A differentiated analysis on the individual party level in shows that until 2013 the disparity was mainly due to the better results of the Left in Eastern Germany.

Figure 5. Difference Index of Vote Shares between Eastern and Western Germany, 1994–2019. Data Source: Bundeswahlleiter (Citation2018).

In 2017, however, it is the election results of the right-wing populist AfD that differ most between Eastern and Western Germany. While the Left's vote shares in Eastern and Western Germany levelled up, the differences in the AfD vote shares surged (see also Hebenstreit this issue). At the level of specific parties and their vote shares in the two regions, then, we see no convergence of party systems nearly 30 years after reunification. The development rather speaks for the third hypothesis of persistent differences between the two regions.

Conclusions and Discussion

How can we characterise the development of the German party systems in the three decades since reunification? Was there an alignment of Eastern Germany's party system with the Western German model? Did the party system in Eastern Germany become institutionalised? Comparative findings from Central Eastern Europe for the first years after democratisation support this expectation. It is particularly likely for the Eastern German case, since the political parties were largely imported from Western Germany. Therefore, after reunification the Eastern German party system should soon have resembled the one in Western Germany. However, party system scholars have also observed a trend toward less party system stability, towards dealignment and possibly even party system de-institutionalisation in the established democracies of Western Europe in the last decades. Therefore, we could also expect the formerly stable party system in Western Germany adapting to the not yet institutionalised party system in Eastern Germany. Alternatively, the party systems in the two parts of the country could remain different. This article explores these questions on the basis of three hypotheses. Five indicators were analysed over time: volatility, vote-switching, availability, electoral fragmentation, and the difference in the vote shares of the parties in Eastern and Western Germany.

We observed similar trends for the first four indicators: In the first years after reunification, there was an institutionalisation and stabilisation of the party system in Eastern Germany. This is true for volatility, vote-switching, availability, and fragmentation. As time progressed, it once more became more fragmented and volatile, with voters more willing to switch their party choice and their votes becoming more available on the electoral market. The situation in Western Germany is only slightly different: After a prolonged period of stability in the 1990s, party system stability decreases, indicated by an increase in volatility, fragmentation, availability, and the proportion of vote switchers. Comparing the present situation with the 1990s, we can conclude that the greater party system transformation did not take place in Eastern Germany, but in Western Germany. This does not imply, however, that this process was triggered by the reunification and the party systems in Eastern Germany drove the developments in Western Germany. Taken together, the findings are in line with both the first and second hypotheses of convergence, but only in certain and different periods. In the first ten to twelve years, the data tends to support the first hypothesis of convergence by institutionalisation in Eastern Germany; since then, the data suggests a parallel development or even a convergence by stronger de-institutionalisation in Western Germany.

At the more detailed level of differences in the parties’ vote shares, both convergence hypotheses predict a decrease of differences – the strength of the parties would be similar over time in Eastern and Western Germany. In line with the first hypothesis, we would expect the mainstream parties CDU and SPD to establish themselves in Eastern Germany to the same degree as in Western Germany. The second hypothesis implies the leftist party Die Linke to have similar results in Western as in Eastern Germany. In fact, however, the differences did not decrease. The vote share differences increased during the 1990s and have remained at a high level ever since. The three findings – 1) the differences (mainly due to the greater success of the AfD in Eastern Germany in 2017), 2) the similarly high proportions of vote switchers in Eastern and Western Germany, and 3) the higher volatility scores in Eastern Germany – point to the fact that voters in Western Germany are similarly available and switch to a similar extent as voters in Eastern Germany. However, West Germans (still) have a stronger link to the established parties.

In conclusion, we observe a shift in Western Germany from the stability of the old Federal Republic to more instability and fragmentation, whereas in Eastern Germany we see only an initial formation of party system stability in the 1990s, followed by an increase in fluidity and fragmentation. This shows both institutionalisation and dealignment consecutively. In an East-West comparison, the similarities of the party systems outweigh the differences. Nevertheless, the party constellations in Eastern and Western Germany, which form the structurally similar party systems, are still different. Based on the findings presented here, we can assert that the party systems have undergone substantial transformations and the hyper-stability of German party politics is certainly a thing of the past. It seems possible to detect symptoms of de-institutionalisation of Germany’s party system in the coming years. Thus, when studying German politics, we must not disregard the potential consequences of party system de-institutionalisation on the legitimacy and functioning of an established representative democracy.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aiko Wagner

Aiko Wagner is a Research Fellow at the Research Unit Democracy and Democratization at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center. Since 2009, he has been part of the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES). His main research interests include political attitudes and behaviour, electoral and party systems, and representation and political competition.

Notes

1 Arzheimer (Citation2017), however, shows that dealignment in Western Germany and therefore the trend of loosening ties between parties and voters slowed down in the last decade.

2 The equation for individual vote-switching is , where t indicates elections.

3 Specifically, the data source for 1994 is Zelle (1998), for 1998–2005 Hofrichter and Kunert (Citation2009), and for 2009 was Merz and Hofrichter (Citation2013).

4 The question reads as follows: ‘How probable is it that you will ever give your vote to the following parties? Please use the numbers on this scale to indicate your views, where ‘1’ means ‘not at all probable’ and ‘11’ means ‘very probable’’’. For simplicity, all PTVs are recoded to 0–1, with 0 = ‘no inclination whatsoever’ and 1 = ‘very likely to give this party the vote’.

5 If a voter rates three parties equally high (,

, and

), the availability score equals two (1- (1-1) + 1- (1-1)) 2. If another voter has a clear party preference (e.g.

,

, and

), the availability score equals zero (1- (1-0) + 1- (1-0)) 0.

6 Consequently, the dates refer to the European Parliament (EP) elections. Using data from EP elections might bias the estimates as EP elections are generally said to be second-order elections. On average, there is lower turnout in EP election and smaller and more radical (opposition) parties win more votes than in first-order elections (typically national parliament elections). Thus, availability might be higher when measured in the context of EP elections compared to scores obtained for Bundestag elections. However, this potential bias is the same for citizens in both parts of Germany, East and West. Thus, it does not affect the differences and/or convergence of the two party systems.

Bibliography

- Abedi, Amir. 2017. “We Are Not in Bonn Anymore: The Impact of German Unification on Party Systems at the Federal and Land Levels.” German Politics 26 (4): 457–479.

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2017. “Another Dog that did not Bark? Less Dealignment and More Partisanship in the 2013 Bundestag Election.” German Politics 26 (1): 49–64.

- Arzheimer, Kai. Forthcoming. “Regionalvertretungswechsel von Links Nach Rechts? Die Wahl von Alternative für Deutschland und Linkspartei in Ost-West-Perspektive.” In Wahlen und Wähler. Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagswahl 2017, edited by Bernhard Weßels, and Harald Schoen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Bartolini, Stefano, and Peter Mair. 1990. Identity, Competiton and Electoral Availability - The Stabilisation of European Electorates 1885-1985. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Birsl, Ursula, and Peter Lösche. 1998. “Parteien in West- und Ostdeutschland: Der gar Nicht so Feine Unterschied.” Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 29 (1): 213–217.

- Brader, Ted, and Joshua A. Tucker. 2008. “Pathways to Partisanship: Evidence from Russia.” Post-Soviet Affairs 24 (3): 263–300.

- Bräuninger, Thomas, Marc Debus, Jochen Müller, and Christian Stecker. 2020. Parteienwettbewerb in den Deutschen Bundesländern. 2., ed. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Bundeswahlleiter. 2018. „Ergebnisse früherer Bundestagswahlen“: https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/dam/jcr/397735e3-0585-46f6-a0b5-2c60c5b83de6/btw_ab49_gesamt.pdf, accessed 8 March 2021.

- Caramani, Daniele. 2012. “The Europeanization of Electoral Politics: An Analysis of Converging Voting Distributions in 30 European Party Systems, 1970-2008.” Party Politics 18 (6): 803–823.

- Casal Bértoa, Fernando. 2018. “The Three Waves of Party System Institutionalisation Studies: A Multi- or Uni-Dimensional Concept?” Political Studies Review 16 (1): 60–72.

- Chiaramonte, Alessandro, and Vincenzo Emanuele. 2017. “Party System Volatility, Regeneration and de-Institutionalization in Western Europe (1945–2015).” Party Politics 23 (4): 376–388.

- Chiaramonte, Alessandro, and Vincenzo Emanuele. 2019. “Towards Turbulent Times: Measuring and Explaining Party System (De-)Institutionalization in Western Europe (1945–2015).” Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 49 (1): 1–23.

- Dalton, Russel J. 2014. “Interpreting Partisan Dealignment in Germany.” German Politics 23 (1-2): 134–144.

- Dalton, Russel J. 2018. Political Realignment: Economics, Culture and Electoral Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dalton, Russell J., and Willy Jou. 2010. “Is There a Single German Party System?” German Politics and Society 28 (2): 34–52.

- Dalton, Russell J., and Steven Weldon. 2007. “Partisanship and Party System Institutionalization.” Party Politics 13 (2): 179–196.

- Emanuele, Vincenzo, Alessandro Chiaramonte, and Sorina Soare. 2020. “Does the Iron Curtain Still Exist? The Convergence in Electoral Volatility Between Eastern and Western Europe.” Government and Opposition 55 (2): 308–326.

- Finkel, Steven E., Stan Humphries, and Karl-Dieter Opp. 2001. “Socialist Values and the Development of Democratic Support in the Former East Germany.” International Political Science Review 22 (4): 339–361.

- Franklin, Mark N., Tom Mackie, and Henry Valen. 1992. Electoral Change. Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gabriel, Oscar W. 2007. “Bürger und Demokratie im Vereinigten Deutschland.” Politische Vierteljahresschrift 48 (3): 540–552.

- Hofrichter, Jürgen, and Michael Kunert. 2009. “Wählerwanderung bei der Bundestagswahl 2005: Umfang, Struktur und Motive des Wechsels.” In Wahlen und Wähler. Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagswahl 2005, edited by Oscar W. Gabriel, Bernhard Weßels, and Jürgen W. Falter, 228–250. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, Gary Marks, and Carole J. Wilson. 2002. “Does Left/Right Structure Party Positions on European Integration?” Comparative Political Studies 35 (8): 965–989.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1990. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Jörs, Inka. 2003. “East Germany: Another Party Landscape.” German Politics 12 (1): 135–158.

- Kitschelt, Herbert. 1994. The Transformation of European Social Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kitschelt, Herbert. 2013. “Party Systems.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Science (Online Edition), edited by Robert E. Goodin. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey. 2008. West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Laakso, Markku, and Rein Taagepera. 1979. ““Effective” Number of Parties.” Comparative Political Studies 12 (1): 3–27.

- Mainwaring, Scott, and Torcal Mariano. 2006. “Party System Institutionalization and Party System Theory After the Third Wave of Democratization.” In In Handbook of Party Politics, edited by Richard S. Katz, and William Crotty, 34–46. London: Sage.

- Mair, Peter. 2015. “Party Systems.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (Second Edition), edited by James D. Wright, 567–569. Elsevier.

- Merz, Stefan, and Jürgen Hofrichter. 2013. “Wähler auf der Flucht: Die Wählerwanderung zur Bundestagswahl 2009.” In Wahlen und Wähler. Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagswahl 2009, edited by Bernhard Weßels, Harald Schoen, and Oscar W. Gabriel, 97–117. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Niedermayer, Oskar. 2013. “Die Analyse von Parteiensystemen.” In Handbuch Parteienforschung, edited by Oskar Niedermayer, 83–117. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Pappi, Franz Urban, and Jens Brandenburg. 2010. “Sozialstrukturelle Interessenlagen und Parteipräferenz in Deutschland.” KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 62 (3): 459–483.

- Pedersen, Mogens N. 1979. “The Dynamics of European Party Systems: Changing Patterns of Electoral Volatility.” European Journal of Political Research 7 (1): 1–26.

- Rattinger, Hans, Sigrid Roßteutscher, Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck, Bernhard Weßels, Christof Wolf, and Aiko Wagner. 2017. “Post-Election Cross Section (Gles 2013). Za5701, Data File Version 3.0.0.”

- Roßteutscher, Sigrid, Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck, Harald Schoen, Bernhard Weßels, Christof Wolf, Aiko Wagner, Reinhold Melcher, and Heiko Giebler. 2018. “Post-Election Cross Section (Gles 2017), Za6801, Data File Version 4.0.0.”.

- Rovny, Jan, and Stephen Whitefield. 2019. “Issue Dimensionality and Party Competition in Turbulent Times.” Party Politics 25 (1): 4–11.

- Saalfeld, Thomas. 2002. “The German Party System: Continuity and Change.” German Politics 11 (3): 99–130.

- Schattschneider, Elmar E. 1942. Party Government. New York: Transactions Publishers.

- Schmitt, Hermann, Stefano Bartolini, Wouter van der Brug, Cees van der Eijk, Mark Franklin, Dieter Fuchs, Gabor Toka, Michael Marsh, and Jacques Thomassen. 2009. “European Election Study 2004 (2nd Edition).” edited by Cologne. ZA4566 Data file Version 2.0.0 GESIS Data Archive.

- Schmitt, Hermann, Sara B. Hobolt, Wouter van der Brug, and Sebastian Adrian Popa. 2020. “European Parliament Election Study 2019, Voter Study.”, edited by Cologne. ZA7581 Data file Version 1.0.0 GESIS Data Archive.

- Schmitt, Hermann, Sebastian Adrian Popa, and Felix Devinger. 2015. “European Parliament Election Study 2014, Voter Study.” edited by Cologne. ZA5161 Data file Version 1.0.0 GESIS Data Archive.

- Schmitt, Hermann, Cees van der Eijk, E. Scholz, and M. Klein. 1997. “European Election Study 1994.” edited by Cologne. ZA2865 Data file Version 1.0.0 GESIS Data Archive.

- Tavits, Margit. 2005. “The Development of Stable Party Support: Electoral Dynamics in Post-Communist Europe.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (2): 283–298.

- Van der Eijk, Cees, Mark Franklin, K. Schoenbach, Hermann Schmitt, and H. Semetko. 1999. “European Election Study – 1999”.

- van der Eijk, Cees, and Erik V. Oppenhuis. 1991. “European Parties’ Performance in Electoral Competition.” European Journal of Political Research 19 (1): 55–80.

- Van Egmond, Marcel, Wouter van der Brug, Sara Hobolt, Mark Franklin, and Eliyahu V. Sapir. 2013. “European Parliament Election Study 2009, Voter Study.” edited by Cologne. ZA5055 Data file Version 1.1.0 GESIS Data Archive.

- Wagner, Aiko. 2017. “A Micro Perspective on Political Competition: Electoral Availability in the European Electorates.” Acta Politica 52 (4): 502–520.

- Wagner, Aiko, and Werner Krause. 2021. “Putting Electoral Competition Where It Belongs: Comparing Vote-Based Measures of Electoral Competition.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 1–18.

- Wessels, Bernhard, and Hermann Schmitt. 2008. “Meaningful Choices, Political Supply, and Institutional Effectiveness.” Electoral Studies 27 (1): 19–30.

- Weßels, Bernhard, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann. 2006. “Parties and Voters—Representative Consolidation in Central and Eastern Europe?” International Journal of Sociology 36 (2): 11–44.

- Zelle, Carsten. 1998. “Modernisierung, Personalisierung, Unzufriedenheit: Erklärungsversuche der Wechselwahl bei der Bundestagswahl 1994.” In Wahlen und Wähler. Analysen aus Anlaß der Bundestagswahl 1994, edited by Max Kaase, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, 221–257. Opladen/Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.