ABSTRACT

This article explores the capacity of randomly-selected, citizen deliberation procedures to deliver on their promise to generate inclusive and considered citizen judgements, connecting these to political authority and the broader public sphere. These ‘mini-publics’ are increasingly adopted in representative democratic systems. Germany is no exception and has been at the forefront of this trend. The article begins with a historical overview of citizen deliberation in Germany, followed by in-depth analysis of the pioneering case of the Bürgerrat Demokratie. This analysis shows mini-publics can produce more inclusive and considered citizen input into policy-making than self-selected participation, but highlights the need for attitudinal stratification in participation selection if mini-publics are to represent politically alienated citizens. Furthermore, it details how the Bürgerrat Demokratie's combination of an innovative, four-phase process design with civil society campaign expertise holds lessons for connecting citizen deliberation to both political authority and the public sphere without institutionalising the process.

The rise of deliberative democratic scholarship has drawn increased attention to the relevance of citizen deliberation in the democratic will-formation process for democratic legitimacy (Dryzek Citation2000; Warren Citation2017). This has provoked the creation of a range of innovative participatory-deliberative processes that aim to add more citizen deliberation into legislative and policy processes. The most prominent of these innovations are called deliberative ‘mini-publics’ (Elstub Citation2014; Harris Citation2019). Mini-publics come in a variety of different shapes and sizes, but share several core features, such as randomly selected participation and facilitated discussions (see OECD Citation2020 for a comprehensive overview). They range from small-scale ‘Citizens’ Juries’ of between 15 and 25 participants to large-scale ‘Deliberative Polls’ of more than 500 participants. These deliberative mini-publics are rapidly spreading around the world (Dryzek et al. Citation2019) in what the OECD (Citation2020) has called a ‘deliberative wave’. Germany has been at the forefront of the wave since, in the 1970s, Peter Dienel invented one of the first small-scale mini-publics, which he called ‘Planning Cells’.

Advocates of mini-publics claim they are a potential solution to increasing concerns about the dysfunctionality of representative institutions. The argument is that by including a broader cross-section of the population in shaping the public will, providing avenues for citizens to reach considered judgements on important political issues, and connecting these considered judgements to the legislative and policy process, they can make politics and policy-making more responsive, allaying growing distrust and dissatisfaction in the functioning of democracy (e.g. Dryzek et al. Citation2019). There is strong public support for the introduction of more citizen deliberation in federal level politics. Surveys show widespread desire to make representative institutions more responsive to public voice by adopting more federal-level participation opportunities (Geissel et al. Citation2014), including a large majority in favour of the introduction of deliberative mini-publics (Decker et al. Citation2019). Political elites have become interested in this topic too: the 2017–2021 ‘Grand Coalition’ Government promised an expert commission to investigate how citizen participation procedures can complement representative democracy (Federal Government of Germany Citation2018, 163), in 2020 the Bundestag commissioned a federal-level Citizen’s Assembly on the topic of Germany’s role in the world, and the Sondierungspapier in preparation of the ‘Ampel Coalition’ between the SPD, FDP and the Greens also calls for the use of more Citizens’ Assemblies. Citizen deliberation seems set to become an important component of federal-level politics in Germany. Nevertheless, there remains well-founded scepticism concerning whether deliberative mini-publics can deliver on these promises, with arguments that they are too detached (Papadopoulos Citation2012; Pateman Citation2012), too weak to provide effective challenge (Dean, Boswell, and Smith Citation2020), or simply a democratic veneer for power politics (Johnson Citation2015).

This article explores whether the claims that large-scale, federal-level mini-publics can strengthen democracy in Germany are warranted by scrutinising the Bürgerrat Demokratie (Citizens’ Assembly on Democracy) as a pioneering case. What does it tell us about the capacity of mini-publics to make democratic will-formation more inclusive, generate considered citizen judgements and connect these to decision-making authority? The article begins with a general overview of the use of mini-publics in Germany, charting the journey to the current point in time. It then outlines the regularly claimed objectives of mini-publics to foster inclusive, considered and consequential citizen judgements. This is followed by an in-depth analysis of the case of the Bürgerrat Demokratie, assessing how it performed on these objectives and drawing out lessons for future efforts at citizen deliberation. The article, accordingly, provides both a thorough documentation of this novel case, as well as evidence to inform a live issue in German politics: how to strengthen federal-level political institutions to make them more participatory and deliberative.

Citizen Deliberation in Germany: the Bürgerrat Demokratie in Context

The Bürgerrat Demokratie forms part of a long tradition of citizen deliberation in Germany. A recent OECD report (2020) suggested that, along with Australia, the Federal Republic has conducted the most deliberative mini-publics of any nation between 1986 and 2019. Nevertheless, the Bürgerrat Demokratie is a significant development in this tradition. It is the first national-level Citizens’ Assembly exclusively initiated by civil society organisations (CSOs). This distinguishes the process from other deliberative initiatives in Germany in terms of its administrative level and number of participants as well as the commissioning organisation and level of institutionalisation.

Citizen deliberation in Germany has largely been shaped by the use of Planning Cells and Agenda21 processes. Planning Cells were developed by German professor Peter Dienel in the early 1970s. Along with citizens’ juries (invented simultaneously in the US), they were the first form of deliberative mini-publics to be developed and have become an archetypal model (Elstub Citation2014; Setälä and Smith Citation2018; Harris Citation2019). They aim to increase governing capacity by bridging the gap between citizens and the political-administrative sphere by involving citizens in will-formation (Dienel and Renn Citation1995). Planning Cells have proved popular with public authorities, making them the most frequently used type of mini-public in Germany (Hendriks Citation2005; Smith Citation2009; OECD Citation2020). Unlike Planning Cells, Agenda21 processes do not meet all the definitional criteria of a deliberative mini-public, since they do not select their participants through random selection. Still, their widespread adoption means they have been an equally important venue for citizen deliberation in Germany.

There are two significant differences between the Citizens’ Assembly process, used for the Bürgerrat Demokratie, and the more commonly employed Agenda21 and Planning Cells. One is the number of participants involved in the deliberations: Citizens’ Assemblies typically recruit more than 100 participants – the Bürgerrat recruited 160 – whereas Planning Cells restrict each cell to 25 people, running multiple cells in parallel. The second difference is that Planning Cells are normally conducted on the local level. There have been some on the state level – in Bavaria on consumer protection (Hendriks Citation2011, 108–129) and in Baden-Württemberg on volunteering and societal engagement – and some isolated examples of federal level planning cells – for instance, by the former Federal Ministry of Postal Service and Telecommunication on the future of the digital telephone, as well as by the Ministry of Research and Technology on new information technologies and national energy policies (Dienel and Renn Citation1995). Agenda21 processes have been even more locally focused. Following the ‘Agenda21-resolution’ established by the UN Conference on Environment and Development in 1992, which assigned particular importance to the local level, many procedures have been carried out in German municipalities. In contrast to the ad-hoc character of mini-publics in general and planning cells in particular, local Agenda21 processes are designed as long-term participatory processes for community organising in order to implement sustainable development.

The Bürgerrat Demokratie is part of a growing trend of adopting deliberative mini-publics at higher-levels of government. On the state level, this includes a pioneering attempt to develop more institutionalised forms of deliberative participation in the state of Baden-Württemberg, which began implementing citizen deliberation in the legislative process and introduced a state-councillor on civil society and citizen participation in 2011. This was a direct consequence of difficulties with the infrastructure project ‘Stuttgart21’, which led to the adoption of a ‘politics of being heard’, with the participation of randomly-selected citizens employed to pursue ‘participatory law-making’ (Brettschneider and Renkamp Citation2016).

There have also been other recent experiments that have aimed to involve randomly-selected citizens in deliberative initiatives on the federal level. The Federal Ministry for Environment, Conservation and Nuclear Safety is the most active proponent, seeing citizen participation as a necessary element in shaping environmental policies (Pfeifer, Opitz, and Geis Citation2020). These processes were often conducted on a similar scale to Citizens’ Assemblies. In 2015 the Ministry initiated the ‘Climate Protection Plan 2050 (‘Klimaschutzplan 2050’), involving 472 randomly selected citizens in five cities throughout Germany (Faas and Huesmann Citation2017) and the ‘ProgRess II’ resource efficiency programme, involving 200 randomly-selected citizens. Four years later, 250 citizens and 50 youth representatives were involved in ‘ProgRess III’. There was also a process on the ‘integrated environmental program 2030’, and a permanent mixed assembly since 2016 in the ‘National Monitoring Body on the Selection Process of a Nuclear Disposal Site’. The Bürgerrat Demokratie should therefore be seen as part of an increasing tendency to adopt large-scale deliberative initiatives to influence federal level policy-making.

There is an important difference between the Bürgerrat Demokratie and previous federal processes: it was initiated, funded, and run by CSOs. The local, state and federal level initiatives referred to above were initiated by executive or administrative actors in order to influence their own policy-making and implementation processes. The Bürgerrat Demokratie was intended to influence an expert commission on democratic reform, promised (but never established) by the ‘Grand Coalition’ Government, but had no formal connection to the promised commission. The process therefore had a stronger connection to civil society and a weaker connection to political institutions than is typical of most other deliberation processes in Germany. This is a significant development because government-led mini-publics have been criticised for being too far removed from civil society, in the worst cases even crowding out bottom-up participation (Boswell, Settle, and Dugdale Citation2015). Following the Bürgerrat Demokratie, the ÄltestenratFootnote1 of the Bundestag initiated a Citizens’ Assembly on the subject of Germany’s role in the world (Deutscher Bundestag Citation2020a), the first legislative-initiated mini-public in Germany. This Assembly was to be modelled on the Bürgerrat Demokratie and run and funded by the same CSOs, marking a new hybridisation between the legislative and civil society in conducting deliberative-participatory exercises (Deutscher Bundestag Citation2020b). This was then followed by a further civil society organised, federal-level Citizens’ Assembly on Climate Change (Bürgerrat Klima) in 2021. As such, the increased interest in and use of larger-scale deliberative mini-publics to complement representative democratic processes makes it important to learn the lessons of the Bürgerrat Demokratie regarding what these initiatives can contribute to the democratic system.

Objectives of Citizen Deliberation

Inclusive Participation

A key objective of deliberative mini-publics is to address a well-documented problem in contemporary democracies: unequal participation. The fact that the wealthy and well-educated participate in politics substantially more than other socio-economic groups (Verba and Nie Citation1987; Dalton Citation2017) poses a challenge to the foundational concept of political equality. Under-representation of poorer and less-educated members of society is apparent in voting behaviour (Schäfer Citation2015) and is even stronger for more demanding forms of participation such as involvement in parties or citizens’ initiatives. Mini-publics are designed to guard against this by replicating the diversity of the public in miniature. By using stratified random selection, they aim to recruit participants that reflect the population on salient characteristics. This attempt to expand the diversity of voices that influence policy formation and public debates, nevertheless, cannot be fully addressed through random selection. Since invitees can freely choose to accept or decline the invitation, the risk of selection bias remains. In addition, there are concerns that reproducing the public in miniature could reproduce the same structural exclusions as the broader public sphere, with marginalised groups included in too small numbers to really make their voices count. Mini-publics typically employ trained facilitators to reduce these forms of exclusion. Nevertheless, there is evidence showing that women and less-educated people can be disadvantaged regarding their actual contributions to discussions (Karpowitz, Mendelberg, and Shaker Citation2012; Karpowitz and Mendelberg Citation2014; Gerber Citation2015). To understand whether processes like the Bürgerrat Demokratie can contribute to making citizen deliberation in Germany more inclusive, it is therefore important to examine who was selected to participate in the process in terms of sociodemographic as well as attitudinal representativeness, as well as whether there was relative equality of participation within the process itself.

Considered Judgement

A claimed strength of mini-publics vis-à-vis other democratic innovations is that they arrive at considered judgements (Smith Citation2009). Deliberative democracy itself emerged from concerns that the prevailing liberal and elite conceptions of democracy paid insufficient attention to the quality of processes of will-formation (Dryzek Citation2000). Deliberative mini-publics were therefore designed to provide opportunities for citizens to reach considered judgements through the free and fair exchange of reasons in an environment structured to approximate ideal conditions for deliberation. This is intended to expand the breadth of inputs into political institutions beyond professionalised interest groups and experts by including a citizen perspective, whilst also ensuring this perspective is more substantial than ‘raw’ public opinion (Fishkin Citation2009; Setälä and Smith Citation2018). This is achieved through providing participants with sufficient time to deliberate, up-to-date information and expert witnesses to inform their discussions, as well as using ground-rules for discussion and trained facilitators to ensure mutually respectful exchanges. The claim is that ‘when citizens are given the time, resources and support to learn and deliberate about public issues, they can engage with complex debates and collectively make considered judgements’ (Escobar and Elstub Citation2017, 6). To learn the lessons of the Bürgerrat Demokratie for citizen deliberation in Germany, this article examines the timing, expert information, and facilitation, using a combination of researcher observations of the process and participants’ reported views in a post-event survey.

Consequences on the Political Process

The value of any deliberative initiative is partly determined by how consequential the deliberations are (Dryzek Citation2009): do they have any tangible influence on public policies, for instance? To contribute considered citizen judgements into the democratic system and make it more inclusive, deliberation must be connected to the system, either working indirectly through the public sphere, or directly with representative institutions and administrative actors to achieve ‘macro political impacts’ (Goodin and Dryzek Citation2006). A significant criticism of mini-publics has highlighted their difficulties in making these connections (Dean, Boswell, and Smith Citation2020). The argument is that, commonly conducted as ad hoc, one-off processes, mini-publics do not become embedded in the regular political cycle, and the use of random selection also means that they are disconnected from civil society actors (Papadopoulos Citation2012; Pateman Citation2012). This concern has resulted in a growing focus situating mini-publics within a broader deliberative system (Niemeyer Citation2014; Curato and Böker Citation2016; Felicetti, Niemeyer, and Curato Citation2016), in particular, exploring their connections to representative decision-making processes (Hendriks Citation2016; Setälä Citation2017; Green, Kingzette, and Neblo Citation2019; Kuyper and Wolkenstein Citation2019). It has even been observed how deliberative-participatory processes are themselves becoming more system-like, operating multiple channels in order to achieve these connections (Dean, Boswell, and Smith Citation2020).

Policy effects are not the only way that mini-publics can have impacts. As Jacquet and van der Does (Citation2020) have highlighted, they can also have individual-level effects on the participants in the mini-public that radiate outwards, and structural effects on the political system, by shifting the mode of policy-making in a participatory-deliberative direction. Mini-publics can provide an ‘educative forum’, offering participants opportunities to listen to the interests and opinions of others, engage in reasoned and respectful discussion, and find compromises (Fung Citation2003, 340). They can strengthen political knowledge and interest (Fournier et al. Citation2011), as well as participants perceptions of their internal and external political efficacy (Farrell, O’Malley, and Suiter Citation2013; Knobloch and Gastil Citation2015). One indirect consequence on the political system is thus through strengthening participants’ democratic capacities for long-term political engagement (Geissel Citation2012; Escobar and Elstub Citation2017), so that the participants take their own independent actions. To draw out the lessons from the Bürgerrat Demokratie for how citizen deliberation initiatives can be consequential, this article examines how the processes was designed to connect to political institutions and public debate, as well as support for participants to take their own actions.

The Process of the Bürgerrat Demokratie

The Bürgerrat DemokratieFootnote2 is a multi-stage, citizen deliberation process tasked with considering means for reforming federal level democracy in Germany in order to improve public participation and public trust. The aim was to advance long-standing debates about supplementing the federal political system with direct democratic procedures (see, e.g. Grotz Citation2013; Mörschel and Efler Citation2013) and/or citizen deliberation procedures (see, e.g. Huber and Dänner Citation2018; Roth Citation2018; Geissel and Jung Citation2019). This debate was given renewed impetus by the ‘Grand Coalition’ Government’s announcement that it would ‘set up an expert commission in order to elaborate suggestions whether and how the well-proven parliamentary-representative democracy can be complemented by elements of citizen participation and direct democratic procedures’ (Federal Government of Germany Citation2018, 163). This motivated two CSOs – Mehr Demokratie e.V. and the Schöpflin Foundation – to initiate the Bürgerrat Demokratie with the aim both to provide input for the planned commission and showcase a prototype for citizen deliberation on the national level. Two consultancies – IFOK GmbH and nexus e.V. – were instructed to conduct the process, supported by an academic and civil society advisory council to ensure quality and independence. The total cost was €1.4 million, funded by Mehr Demokratie (€1 million), Schöpflin Foundation (€250,000) and Mercator Foundation (€150,000).

The centrepiece of the process was the Bürgerrat – a Citizens’ Assembly that took place for four days across two weekends in Leipzig. The selection of a Citizens’ Assembly was inspired by the recent Irish Constitutional Convention, which had successfully deployed this technique to deliberate a range of contested constitutional questions (Farrell and Suiter Citation2019). It consisted of 160 citizens recruited by stratified random selection. Participants were tasked with deliberating the over-arching question of whether and how Germany’s representative democratic system should be supplemented by citizen participation and direct democracy. The programme was structured along seven themes: challenges of democracy, direct democracy, citizen participation, lobbyism, representativeness, online participation and combinatory models of democracy. Each theme began with plenary sessions containing presentations from and discussions with subject experts, followed by professionally facilitated small group deliberations. These small groups formulated recommendations which were collected and summarised by a team of seven participants supported by a team of editors. This produced 22 recommendations, which were voted upon by all the participants in plenary, then compiled into a citizens’ report (‘Bürgergutachten’Footnote3).

The Bürgerrat comprised the second of four phases of the process; it was preceded by six regional conferences (‘Regionalkonferenzen’), held consecutively in Erfurt, Schwerin, Koblenz, Gütersloh, Mannheim and Munich. These six events were open for all interested citizens and additionally, the organisers invited CSOs and politicians of all levels. In each event, participants discussed potential issues and questions for the agenda of the Bürgerrat in small groups. Then, the results were prioritised by all participants to concretise the agenda for the Bürgerat.

Phase three – the ‘Day for Democracy’ (‘Tag für die Demokratie’) – was a public event to raise awareness of the Bürgerrat and its recommendations. All participants of the regional conferences and the citizens’ assembly were invited to Berlin, where the recommendations were handed over to the president of the Bundestag, Wolfgang Schäuble, and then discussed by delegates from all parties represented in the Bundestag.

Phase four was the implementation phase (‘Umsetzungsphase’). In order to support the implementation of the recommendations, there were meetings of members of the Bürgerrat and representatives of the Bundestag and state parliaments, as well as chairmen of the parliamentary groups. At the close of the analysis 22 conversations had been held with politicians about the deliberative procedure and its outcome, as well as an online press conference summarising developments during the first 100 days after the handover of the recommendations.

Table 1. Overview of the Bürgerrat Demokratie process.

Our below analysis considers all four phases of the Bürgerrat Demokratie process () but the main focus is the centrepiece Citizens’ Assembly. This provides the foundation for our assessment of the capacity of deliberative mini-publics to strengthen federal level democracy through more inclusive participation and considered public judgements. The other three phases are analysed in terms of their contribution to connecting the Bürgerrat to the democratic system, which was their primary aim. Accordingly, the focus of our analysis mirrors the focus of the process. The five different data sources we employ and how they relate to the three criteria of inclusiveness, considered judgement and consequences are detailed in the methodological appendix.

Analysis

Inclusive Participation

The Bürgerrat aimed to reflect the population of Germany in its composition by recruiting a stratified random sample of participants. The selection process involved three steps to attempt to ensure a representative group of participants. First, 98 municipalities across all federal states were randomly selected, stratified according to population size, and asked to provide a random sample of citizens. 76 municipalities responded culminating in a list of 4362 residents who were then invited to participate, with 250 people accepting the invitation – a response rate of 5.7%. The 160 participants were then selected to mirror as closely as possible the population of Germany on gender, age, education, migration background, size of municipality and region. Other best-practice techniques were also used to try to reduce the well-known issue of selection bias in the acceptance of the invitation to participate. Participants were sent personal invitations, endorsed by the President of the Bundestag to demonstrate the legitimacy of the process. Moreover, all participants received an honorarium of 300€ in total (75€ per day being the standard rate employed by the organising participation consultancies), plus costs of travel, food and accommodation.

The Bürgerrat was largely successful in generating a representative population sample according to the socio-demographic characteristics it employed for stratification. The composition of the group was very similar to the population in terms of gender, age, municipality and migration background (see ). However, the highly educated were heavily overrepresented. The recruitment process also did not employ any attitudinal stratification criteria, but this information was collected as a part of the evaluation process. It showed an over-representation of those with high levels of political interest and of those who favoured a participatory conception of politics, for example: 45 per cent of the respondents of the Bürgerrat stated that citizens should decide important issues rather than politicians, while, according to a recent representative survey, 35 per cent of the population share this preference (ALLBUS 2018). This is concerning because, if the sample is attitudinally biased on the topic of the deliberations, then they may produce recommendations that would not be supported by the population.

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of the Bürgerrat compared to the population.

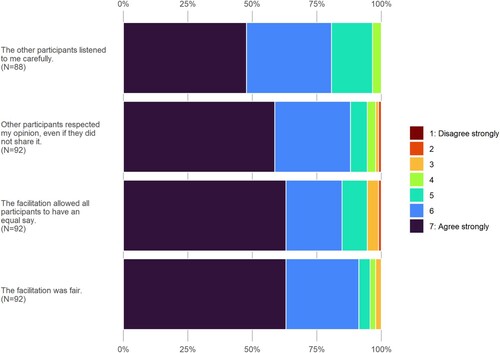

Overwhelming majorities of the respondents reported that the facilitation was fair and provided equal opportunities for everyone to speak (). Similarly, the respondents reported that their deliberations with each other were characterised by honesty and respect for each other’s opinions (). These assessments are supported by researcher observations of the deliberations. Though there was not the resource to observe every small group discussion, two observers followed a sample of these throughout the event, completing a standardised protocol that qualitatively assessed the inclusiveness of the facilitation and the participants’ exchanges with each other. These observations did not find any systematic exclusion of participants from the deliberations.

Figure 1. Participant assessment of the inclusiveness of deliberation. Source: Post-survey of the participants.

To understand whether citizens’ assemblies can foster more inclusive participation it is important to compare them, not only to an ideal of representativeness, but also to the performance of other relevant alternatives. The over-representation of the highly educated and politically motivated is a well-known problem of citizen participation, which stratified random selection does not automatically overcome (see also: Faas and Huesmann Citation2017, 30). Within the Bürgerrat Demokratie it did mitigate the problem compared to open self-selection. The Regional Conferences that preceded the Bürgerrat used open, self-selection (with some stratification when they were oversubscribed), so provide a direct comparison of the two selection techniques. Whereas 62 per cent of the participants in the Bürgerrat were highly educated, this increased to 80 per cent for the Regional Conferences. Similarly, the Bürgerrat compares favourably to the Regional Conferences on political interest: 47 per cent of the Bürgerrat participants had a strong interest in politics compared to 90 per cent of the Regional Conference participants. The recruitment strategy of the Bürgerrat did not, however, manage to redress the under-representation caused by eroding turnout in elections of those with a low education and low political interest. Only 4 per cent of the Bürgerrat participants reported not voting in the last federal election, and the voting public is significantly more representative of the population than the Bürgerrat on these dimensions.

Citizens’ assemblies, like the Bürgerrat, provide a promising avenue for making citizen participation more inclusive compared to more traditional forms of self-selected participation, but require improvements to recruitment if they are to be part of the solution to deeper forms of political exclusion. In particular, the stark over-representation of the highly educated in the agenda-setting and deliberation is a problem that needs to be addressed, especially given the importance of educational background in a range of salient political cleavages. Recruitment could, for instance, include over-sampling in low-income neighbourhoods to account for differential uptake of the invitation to participate. In addition, stratification should go beyond socio-demographic characteristics to include an attitudinal component, as, for instance, in the case of the UK Brexit Assembly (Renwick et al. Citation2017). This would not only ensure that people with diverse opinions on the topic under discussion are included but could also be used to ensure recruitment of those with different levels of political interest and behaviour.

Considered Judgement

The Bürgerrat employed all the common methods of mini-publics to support the deliberations of participants and ensure they reach considered judgements: background information was posted to the participants before the meeting, each thematic topic included an expert input sessionFootnote4 with the chance for participants to discuss this information and ask questions, and professional facilitation aimed to ensure the full variety of participants’ opinions were heard.

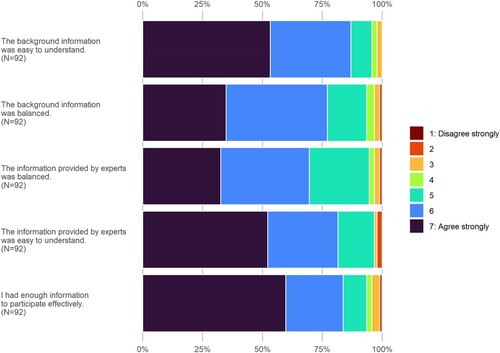

The high-level of participant satisfaction with the facilitation was already discussed in the previous section and equally large majorities approved of the background information and expert inputs (). More than 90 per cent of the respondents said they found the background information and expert inputs balanced and comprehensible, reporting they had enough information to participate effectively in the deliberations. Documentary analysis and observations of the sessions mostly supported this positive assessment, but also revealed two issues.

Figure 2. Participant assessment of the quality of information. Source: Post-survey of the participants.

The first issue was that the organisers struggled to attract experts critical of citizen participation, direct democratic procedures, and combinatorial models of democracy. Hence, the input by experts was unbalanced on these topics – for instance, the session on direct democratic procedures consisted of three proponents against one opponent. This was mitigated by the attempt of two of the academics to draw a balanced picture, and the fact that a comparison of the expert input and the table discussions showed that the participants also raised their own points on these subjects. Still, some common arguments against direct democracy were missing. This shows the difficulty of conducting a balanced discussion about participatory reform of democracy within a participatory process. There are obvious reasons that opponents of more participation would be reluctant to attend a participatory process to raise arguments against participation. Nevertheless, this issue is not likely to be so pronounced for other mini-publics on other themes, such as climate change, that are not so tightly connected with the nature of the process itself.

Researcher observations of the small-group discussion also revealed issues of deliberative quality. An in-depth analysis of selected table discussions (Wipfler Citation2020) showed that they did not engage with the full range of arguments before making recommendations. In addition, they tended to follow a pattern of consecutive point-raising by participants rather than the back-and-forth exchange of reasons. Two elements of the process design contributed to this issue. First, the time for in-depth discussion was limited by the fact that seven topics were covered in four days. On average only 1.5 h was spent on each complex topic. Due to the short amount of time and the format of the process, participants had less opportunities to exchange reasons and argue for and against recommendations compared to other citizen assemblies. Second, the output of the process was a bullet-point list of 22 recommendations accompanied by a vote tally of those for and against the recommendations, rather than a collective agreement on a specific solution, as for example in the British Columbia Citizens Assembly, which proposed a new voting system. This kind of output does not entail the same intensity of deliberation as reaching a collective agreement. Moreover, this was compounded when a final session to deliberate the recommendations before voting was cut.

Whether citizens assemblies contribute considered citizen judgements into the democratic system should therefore be understood as a matter of degree. The votes by the participants of the Bürgerrat in favour or against the 22 recommendations for democratic reform can definitely be viewed as informed by relevant considerations, much more so than the snap judgements of public opinion surveys and focus groups that are more commonly used to gauge public opinion. This citizen perspective also provides an informed input into will-formation that is different from professionalised interest groups or experts. In this case the value of the recommendations consists in the fact that informed citizens could agree almost unanimously on complex recommendations, rather than providing a specific solution to a political problem. Future deliberative initiatives could build on the strengths of the Bürgerrat by selecting a narrower topic and an output format more oriented towards encouraging practical reasoning.

Consequences on the Political Process

The initial conditions for the Bürgerrat Demokratie to influence the political process appeared unpromising. As a civil society organised event it had no formal connection to government institutions, and the commission it originally intended to inform was never established. In addition, producing a list of 22 recommendations, many of which are quite broad in nature opens up the possibility for substantial cherry-picking in the uptake of those recommendations. Nonetheless, the process has achieved some notable successes. It provoked the aforementioned Citizens’ Assembly on Germany’s Role in the World, the first procedure to be initiated by a legislative-connected body. Furthermore, a session of the Bundestags Subcommittee on Civic Engagement subsequently discussed the use of citizens’ assemblies for parliamentary advice.Footnote5 In addition, it has been cited as an influence by a growing number of local climate assemblies and has built a network for further projects. As such, the Bürgerrat provides a number of important lessons for future attempts at consequential citizen deliberation.

The centrepiece Citizens Assembly did not follow the ‘Irish-model’ of integrating political representatives directly into the deliberations, but it did connect to politicians in other ways. The former Prime Minister of Bavaria, Günther Beckstein acted as Chairperson, attending all four days of deliberation and using his influence to advocate for deliberative processes in the media. Moreover, the president of the Bundestag, Wolfgang Schäuble, acted as patron for the process, both by endorsing the invitation letters to participants and receiving the recommendations of the Bürgerrat at the ‘Day for Democracy’, a public event at the Bundestag. These connections have proved important. Wolfgang Schäuble, for instance, was instrumental in securing the backing of the legislature for the Citizens’ Assembly on Germany’s Role in the World.

As aforementioned, the design of deliberative mini-publics is increasingly becoming more complex, incorporating multiple stages in order to improve connections to important stakeholders (Dean, Boswell, and Smith Citation2020). The four-phase design of the Bürgerrat Demokratie pioneered some interesting developments in this respect. The six Regional Conferences that comprised the first phase not only performed an agenda-setting function, but also built a constituency of stakeholders in the process. Politicians of all levels were invited. Many members of state parliaments, the Bundestag, and Heads of Divisions attended these events, including prominent figures like the Prime Minister of Thuringia, Bodo Ramelow, and the Chairman of the CDU/CSU Parliamentary Group, Ralph Brinkhaus. Invitations were also extended to CSOs, drawing on the organisers’ extensive networks. All participants in the Regional Conferences were kept updated about the Bürgerrat and later invited to participate in the third phase, the Day for Democracy, to discuss the results of the Bürgerrat. The first and third phases thus worked to involve interested stakeholders who, by the nature of random selection, were excluded from the Bürgerrat, functioning to better connect the Bürgerrat to political representatives and civil society.

The multi-phase design was accompanied by extensive public relations work to drive interest in the Bürgerrat and promote its recommendations. Media analysis uncovered more than 400 print, online, radio and TV reports on the process (as of 22.11.2019). This included articles in leading newspapers such as the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, the Süddeutsche Zeitung and Die Zeit. The majority of the media attention focused on the Bürgerrat, but the Regional Conferences were also covered in their own right and, following an eye-catching, large-scale public art demonstration outside the Bundestag, the Day for Democracy was featured on the prime-time TV news show, Tagesschau. As is often typical with media reporting of Citizens’ Assemblies, much media coverage concentrated on the novelty of randomly-selected citizen participation, rather than the recommendations themselves. However, this is less of an issue for the Bürgerrat than other processes since some of the recommendations were to introduce and institutionalise more randomly-selected citizen participation. The public relations work was thus successful in attracting media attention to new forms of participation, however; it remains beyond the scope of this article to understand the extent this translates into public awareness or public pressure to adopt these forms of participation.

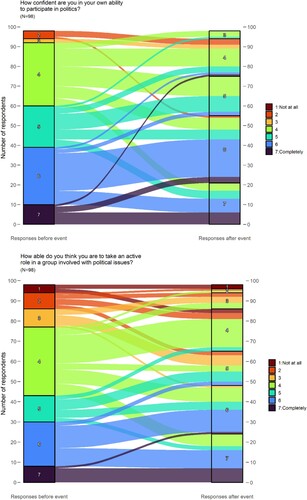

The Bürgerrat also impacted the democratic capacities of individual participants, as observed in other mini-publics. Comparison of pre-event and post-event survey responses found respondents’ self-perception of their capacities to participate increased ((a,b)). Participants additionally reported greater willingness to participate in some common political activities, such as voting and signing petitions. Attitudinal changes have been matched with actions. Some participants have acted on their own initiative to promote the implementation of the Bürgerrat’s recommendations and push for more participation in local and regional politics. These efforts have been supported by the organisers of the Bürgerrat Demokratie. For instance, some have contacted representatives of their respective constituency to discuss their experience with the procedure. Overall, there have been 22 meetings with representatives of state parliament as well as the Bundestag.

Figure 3. a, b Internal efficacy of Bürgerrat participants before and after event. Sources: Pre-survey and post-survey of Bürgerrat participants

Though it is difficult to attribute a direct causal effect, it does appear that the Bürgerrat had consequences on the political process, most notably in encouraging discussion of new forms of federal level participation in both the Bundestag and the media. The effect should not be overestimated. The commissioning of a Citizens’ Assembly on Germany’s Role in the World is only a small step towards the participants’ recommendations of the Bürgerrat Demokratie, for instance, for a ‘legal anchoring’ of these processes. In addition, though there have been these steps towards more citizen deliberation, the recommendations for more direct democracy on the federal level have received little attention. The lesson for future processes is more the means by which the Bürgerrat built pathways to impact. The commissioners and organisers recognised that extensive work was needed before and after the Assembly to achieve this, producing a design and campaigning strategy that was able to connect to political representatives, civil society and the media through informal strategies of influence, despite a lack of formal connection to any government institution. The importance of developing and sustaining a campaign around a citizens’ assembly is rarely addressed in the academic literature on these processes. Yet this proved to be a significant strength of commissioning by CSOs with expertise in developing strategies for informal influence. A deliberative process directly organised by a public authority with the power to implement the recommendations of the deliberation has no need to generate public pressure in order for its recommendations to receive attention. Formally institutionalised processes may therefore more efficiently translate recommendations into policy, but at the expense of generating a broader discussion of the recommendations in the public sphere.

Conclusion

To explore the prospects for citizen deliberation in Germany this article has examined Germany’s first civil-society-led citizens’ assembly on the federal level, the Bürgerrat Demokratie, on three criteria: inclusiveness, considered judgement and consequences on the political process. We demonstrate a mixed picture across the three. Though the Bürgerrat showed random-selection can produce a more representative set of participants than is likely from open, self-selection, the highly educated and politically active were still over-represented. The recommendations of the Bürgerrat were informed by relevant considerations, but we have doubts concerning the quality of deliberation that can take place when seven topics are discussed in four days. And, though the Bürgerrat has inspired further experimentation with citizen deliberation initiatives, this falls considerably short of full implementation of the participants’ recommendations. We believe these findings have some important lessons for the future practice of citizen deliberation and future research.

As this article demonstrates, assessing whether a mini-public has been successful or not is a difficult task. There is now wide-ranging literature and practical guidance on which normative criteria should form the basis of assessment, but little consideration regarding where the threshold for success/failure lies within these criteria. How inclusive is inclusive enough, for instance? Or take the consequence criteria – should we only judge the Bürgerrat successful if its recommendations are fully adopted? This seems in one sense unreasonable, since few advisory inputs into policy-making have this level of impact, and in another sense, it is even questionable that elected politicians should be viewed as bound to implement the recommendations of a mini-public in this way (Lafont Citation2019), especially an informally constituted one like the Bürgerrat. There remains considerable work for future research to work through these complex conceptual issues. In this article, we have proposed that a potential starting point is to view this as a comparative question – has the mini-public performed better than other plausible alternatives would? – yet this still opens up the question of what the right points of comparison are.

The case of the Bürgerrat also makes apparent the need to better conceive the range of potential consequences of mini-publics, which have been heavily focused on policy impacts and impacts on individual participants (see: Jacquet and van der Does Citation2020). Arguably, the most useful function of the Bürgerrat Demokratie was to reflexively legitimate through public deliberation the demands of civil society organisations for a more participatory federal politics, condensing these into a set of publicly supported recommendations. This is very useful for civil society organisations as it makes it harder to reject their demands as unrepresentative. However, mini-publics have never previously been theorised as having this function.

A broader conception of consequences has lessons for practice too - drawing attention to the value of building multiple pathways to impact, rather than focusing narrowly on policy uptake. This has implications for institutionalisation. A more formal connection to political authority would have its benefits in making transparent how participants’ recommendations are to be implemented. Still, moves to institutionalise should not privilege connections with political institutions over connections with the broader public sphere. One important lesson of the Bürgerrat is that civil society involvement brings networks and campaigning capacity that is an important element in securing these latter forms of connection.

The second lesson for practice is about the importance of aligning the scope of the agenda with the time available for discussion, as well as the function and the topic of the mini-public. It should not be forgotten that policymakers commonly begin from a position of scepticism concerning whether citizen participation can respond to the genuine complexity of their agendas (Dean Citation2019; Hendriks and Lees-Marshment Citation2018). Balancing the breadth of the agenda with the time available for discussion is key to any claims for epistemic quality and likely to prove important in convincing policymakers that mini-publics can perform a valuable advisory function. Similarly, defining the topic of discussion so that it is appropriate to the intended function will play a significant role in whether a mini-public fulfils that function. A broad agenda that produces a long list of recommendations may be effective for legitimating a raft of civil society demands, whereas policymakers will likely prefer a tighter topic that addresses a specific problem (as, for instance, the OECD (Citation2020) suggests). This brings us back to two of the previous lessons for empirical research. First, to assess a mini-public requires a clear understanding of its intended function, because different set-ups may work more or less well to realise different intentions. Second, this variability in functions reiterates the difficulty of developing a standard set of evaluation criteria that can be universally applied, since contextual factors, like the intended function, should be a core consideration.

The third and final lesson for practice is that if mini-publics are to realise their claim to be genuinely representative of the population, then they need to put additional focus on overcoming selection bias to attract politically alienated people to participate. Some first steps towards achieving this would be improved targeting on socio-demographic characteristics, for instance, by over-sampling in low-income, low-voter-turnout neighbourhoods, and the adoption of attitudinal and political behaviour dimensions into the stratification process. This is paramount when the topic is reform of democracy and participatory policy-making itself. However, it is likely to be key for citizens’ assemblies more generally if they are to become part of the solution to growing political alienation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.8 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rikki Dean

Rikki Dean is a postdoctoral fellow in the Democratic Innovations Research Unit, Goethe-University Frankfurt. His research interests encompass democratic theory, public administration theory, participatory policy-making, process preferences and social exclusion.

Felix Hoffmann

Felix Hoffmann has a master’s degree in political science from Goethe-University Frankfurt. During his studies he worked as a project assistant on the evaluation of the Bürgerrat Demokratie. He is now a fellow in a consulting firm that shapes change processes in business, politics and society, focusing on citizen participation and stakeholder engagement in infrastructure processes.

Brigitte Geissel

Brigitte Geissel is professor of political science and political sociology and head of the Democratic Innovations Research Unit at Goethe-University Frankfurt. Her research interests include democratic innovations, new forms of governance and political actors (new social movements, associations, civil society, parties, political elites, citizens).

Stefan Jung

Stefan Jung is a PhD candidate at the Research Unit Democratic Innovations, Goethe-University Frankfurt. He studied at Goethe-University Frankfurt, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and Universidad de Granada. His research focuses on democratic innovations, direct democracy, local politics, and social inequality.

Bruno Wipfler

Bruno Wipfler has a master’s degree in public planning and participation from the University of Stuttgart. During his studies he worked as a project assistant on the evaluation of the Bürgerrat Demokratie. He is now employed in the public sector and concerned with citizen participation and sustainability in a city in Southern Germany.

Notes

1 The ‘Ältestenrat’ is a committee that manages the processes and meetings of the Bundestag. It consists of the President of the Bundestag, the vice presidents and twenty-three representatives appointed by the parliamentary groups according to their distribution of seats in the parliament.

2 Further information: www.buergerrat.de

4 Details of participating experts and videos of their contributions are publicly available at: https://demokratie.buergerrat.de/buergerrat/buergerrat-auf-bundesebene/dokumentation/

5 For more information see: https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2020/kw41-pa-buergerschaftliches-engagement-793926.

References

- Boswell, John, Catherine Settle, and Anni Dugdale. 2015. “Who Speaks, and in What Voice?” Public Management Review 17 (9): 1358–1374.

- Brettschneider, Frank, and Anna Renkamp. 2016. Partizipative Gesetzgebungsverfahren. Bürgerbeteiligung bei der Landesgesetzgebung in Baden-Württemberg. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Curato, Nicole, and Marit Böker. 2016. “Linking Mini-Publics to the Deliberative System.” Policy Science 49 (2): 173–190.

- Dalton, Russel. 2017. The Participation Gap. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dean, Rikki. 2019. “Control or Influence? Conflict or Solidarity? Understanding Diversity in Preferences for Public Participation in Social Policy Decision Making.” Social Policy & Administration 53 (1): 170–187.

- Dean, Rikki, John Boswell, and Graham Smith. 2020. “Designing Democratic Innovations as Deliberative Systems.” Political Studies 68 (39): 689–709.

- Decker, Frank, Volker Best, Sandra Fischer, and Anne Küppers. 2019. Vertrauen in Demokratie: Wie Zufrieden Sind die Menschen in Deutschland mit Regierung, Staat und Politik? Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Deutscher Bundestag, Pressestelle. 2020a. “Bundestag beschließt neue Form der Bürgerbeteiligung”. Pressemitteilung vom 18. Juni 2020. Accessed 23 November, 2020. https://www.bundestag.de/presse/pressemitteilungen/701614-701614.

- Deutscher Bundestag, Pressestelle. 2020b. “Bundesweiter Bürgerrat unter Schirmherrschaft Schäubles”. Pressemitteilung vom 27. August 2020. Accessed 23 November, 2020. https://www.bundestag.de/presse/pressemitteilungen/pm-200827-buergerrat-710238.

- Dienel, Peter, and Ortwin Renn. 1995. “Planning Cells: A Gate to ‘Fractal’ Mediation.” In Fairness and Competence in Citizen Participation, edited by Ortwin Renn, Thomas Webler, and Peter Wiedemann, 1–32. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Dryzek, John. 2000. Deliberative Democracy and Beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dryzek, John. 2009. “Democratization as Deliberative Capacity Building.” Comparative Political Studies 42 (11): 1379–1402.

- Dryzek, John, André Bächtiger, Simone Chambers, Joshua Cohen, James Druckman, Andrea Felicetti, James Fishkin, et al. 2019. “The Crisis of Democracy and the Science of Deliberation.” Science 363 (6432): 1144–1146.

- Elstub, Stephen. 2014. “Mini-publics: Issues and Cases.” In Deliberative Democracy: Issues and Cases, edited by Stephen Elstub, and Peter McLaverty, 168–188. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Escobar, Oliver, and Stephen Elstub. 2017. “Forms of Mini-Publics: An Introduction to Deliberative Innovations in Democratic Practice.” Research and Development Note. Canberra: newDemocracy.

- Faas, Thorsten, and Christian Huesmann. 2017. Die Bürgerbeteiligung zum Klimaschutzplan 2050: Ergebnisse der Evaluation. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Farrell, David, Eoin O’Malley, and Jane Suiter. 2013. “Deliberative Democracy in Action Irish-Style.” Irish Political Studies 28 (1): 99–113.

- Farrell, David, and Jane Suiter. 2019. Reimagining Democracy: Lessons in Deliberative Democracy from the Irish Front Line. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Federal Government of Germany. 2018. “Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD, 19.” Legislaturperiode, Berlin.

- Felicetti, Andrea, Simon Niemeyer, and Nicole Curato. 2016. “Improving Deliberative Participation: Connecting Mini-Publics to Deliberative Systems.” European Political Science Review 8 (3): 427–448.

- Fishkin, James. 2009. When the People Speak. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fournier, Patrick, Henk Van der Kolk, Kenneth Carty, André Blais, and Jonathan Rose. 2011. When Citizens Decide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fung, Archon. 2003. “Recipes for Public Spheres: Eight Institutional Design Choices and Their Consequences.” The Journal of Political Philosophy 11 (3): 338–367.

- Geissel, Brigitte. 2012. “Impacts of Democratic Innovations in Europe.” In Evaluating Democratic Innovations: Curing the Democratic Malaise?, edited by Brigitte Geissel, and Kenneth Newton, 163–183. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Geissel, Brigitte, Roland Roth, Stefan Collet, and Christina Tillman. 2014. “Partizipation und Demokratie im Wandel.” In Partizipation im Wandel, edited by Bertelsmann Stiftung, and Staatsministerium Baden-Württemberg, 489–503. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann.

- Geissel, Brigitte, and Stefan Jung. 2019. Mehr Mitsprache wagen: Ein Beteiligungsrat für die Bundespolitik. Bonn: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- Gerber, Marlène. 2015. “Equal Partners in Dialogue? Participation Equality in a Transnational Deliberative Poll (Europolis).” Political Studies 63 (1): 110–130. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12183.

- GESIS. 2019. “ALLBUS/GGSS 2018” GESIS Data Archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13250.

- Goodin, Robert, and John Dryzek. 2006. “Deliberative Impacts: The Macro-Political Uptake of Mini-Publics.” Politics & Society 34 (2): 219–244.

- Green, Jon, Jonathon Kingzette, and Michael Neblo. 2019. “Deliberative Democracy and Political Decision Making”. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Accessed 23 November, 2020. https://polisci.osu.edu/sites/default/files/OxfordEncDelibDecisionMake.pdf.

- Grotz, Florian. 2013. “Direkte Demokratie in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.” In Deutsche Kontroversen, edited by Alexander Gallus, Thomas Schubert, and Tom Thieme, 321–332. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Harris, Clodagh. 2019. “Mini-publics: Design Choices and Legitimacy.” In Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by Stephen Elstub, and Oliver Escobar, 45–59. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Hendriks, Carolyn. 2005. “Consensus Conferences and Planning Cells.” In The Deliberative Democracy Handbook, edited by John Gastil, and Peter Levine, 80–110. New York: Jossey-Bass.

- Hendriks, Carolyn. 2011. The Politics of Public Deliberation. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hendriks, Carolyn. 2016. “Coupling Citizens and Elites in Deliberative Systems.” European Journal of Political Research 55 (1): 43–60.

- Hendriks, Carolyn, and Jennifer Lees-Marshment. 2018. “Political Leaders and Public Engagement.” Political Studies 67 (3): 597–617.

- Huber, Roman, and Anne Dänner. 2018. “Experiment Bürgergutachten: Wie Können wir die Demokratie Stärken?” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 1-2: 169–175.

- Jacquet, Vincent, and Ramon van der Does. 2020. “The Consequences of Deliberative Minipublics.” Representation, doi:10.1080/00344893.2020.1778513.

- Johnson, Genevieve Fuji. 2015. Democratic Illusion. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Karpowitz, Christopher, and Tali Mendelberg. 2014. The Silext Sex: Gender, Deliberation, and Institutions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Karpowitz, Christopher, Tali Mendelberg, and Lee Shaker. 2012. “Gender Inequality in Deliberative Participation.” American Political Science Review 103 (3): 533–547.

- Knobloch, Katherine, and John Gastil. 2015. “Civic (re)Socialization: The Educative Effects of Deliberative Participation.” Politics 35 (2): 183–200.

- Kuyper, Jonathan, and Fabio Wolkenstein. 2019. “Complementing and Correcting Representative Institutions. When and how to use Mini-Publics.” European Journal of Political Research 58 (2): 656–675.

- Lafont, Cristina. 2019. Democracy Without Shortcuts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mörschel, Tobias, and Michael Efler. 2013. Direkte Demokratie auf Bundesebene. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Niemeyer, Simon. 2014. “Scaling up Deliberation to Mass Publics.” In Deliberative Mini-Publics, edited by Kimmo Grönlund, André Bächtiger, and Maija Setälä, 177–201. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- OECD. 2020. Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Papadopoulos, Yannis. 2012. “On the Embeddedness of Deliberative Systems: Why Elitist Innovations Matter More.” In Deliberative Systems, edited by Jane Mansbridge, and John Parkinson, 125–150. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pateman, Carole. 2012. “Participatory Democracy Revisited.” Perspectives on Politics 10 (1): 7–19.

- Pfeifer, Hanna, Christian Opitz, and Anna Geis. 2020. “Deliberating Foreign Policy: Perceptions and Effects of Citizen Participation in Germany.” German Politics, doi:10.1080/09644008.2020.1786058.

- Renwick, Alan, Sarah Allan, Will Jennings, Rebecca McKee, Meg Russell, and Graham Smith. 2017. “The Report of The Citizens’ Assembly on Brexit.” London: The Constitution Unit, UCL.

- Roth, Roland. 2018. “Warum Eine Demokratie-Enquete des Deutschen Bundestags überfällig ist.” Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen 25 (1-2): 160–169.

- Schäfer, Armin. 2015. Der Verlust Politischer Gleichheit. Frankfurt, NY: Campus.

- Setälä, Maija. 2017. “Connecting Deliberative Mini-Publics to Representative Decision Making.” European Journal of Political Research 56 (4): 846–863.

- Setälä, Maija, and Graham Smith. 2018. “Mini-Publics and Deliberative Democracy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, edited by André Bächtiger, John Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark Warren, 300–314. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, Graham. 2009. Democratic Innovations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). 2019. “Statistisches Jahrbuch Deutschland 2019.” https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Querschnitt/Jahrbuch/statistisches-jahrbuch-2019-dl.pdf?__blob = publicationFile.

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). 2021. “GENESIS-Online” October 23, 2021. https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online.

- Verba, Sidney, and Norman Nie. 1987. Participation in America. New York: Harper & Row.

- Warren, Mark. 2017. “A Problem-Based Approach to Democratic Theory.” American Political Science Review 111 (1): 39–53.

- Wipfler, Bruno. 2020. “How Citizens Talk about Democracy: Discourse Quality at Germany's ‘Bürgerrat Demokratie’ and Lessons Learned for the Design of Participatory Processes.” Master's thesis, University of Stuttgart. doi:10.18419/opus-11179.