?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The paper studies a unique education reform that decreased the length of secondary-level vocational education from 4 to 3 years, reducing the time spent on general subjects while keeping the time spent on vocational training. We use a difference-in-difference strategy by comparing reformed schools with early adopters before and after the reform. We find that students’ general skills have dropped considerably, but the probability of dropout has decreased, and the probability of getting a secondary qualification has increased. These results suggest that such a reform will have mixed labour market consequences, at least in the short run.

Highlights

A vocational education reform decreased the length of studies from 4 to 3 years,

It decreased time spent on general and kept time spent on vocational education

We compare early adopters to reformed schools before and after the reform

We show that the effects of the reform are mixed

General skills have decreased, but dropout decreased and graduation probability increased

1. Introduction

There is a growing argument that a well-designed vocational education system can benefit society in many ways. It might speed up the school-to-work transition and increase the initial wages of graduates (Ryan Citation2001; Wolter and Ryan Citation2011; Piopiunik and Ryan Citation2012; Machin et al. Citation2020), while also reducing social inequalities by decreasing dropout (Hemelt, Lenard, and Paeplow Citation2019) or increase employment chances and earnings of lower socioeconomic status people (Field et al. Citation2019; Kemple and Willner Citation2008). At times, when the level of youth unemployment is large and there is a shortage of skills in technical and professional jobs (OECD Citation2019) these are crucial benefits. However, vocational education focused very narrowly on specific skills is also argued to harm graduates in the long run, as specific skills become outdated and adapting to technological change becomes difficult (Hampf and Woessmann Citation2017; Hanushek et al. Citation2017).

Previous research on the effects of vocational education typically studied educational reforms that aim to provide students with better general skills instead of vocational skills (Croatia: Zilic Citation2018; Finland: Ollikainen and Karhunen Citation2021; France: Canaan Citation2020; Italy: Comi, Grasseni, and Origo Citation2022; Norway: Bertrand, Mogstad, and Mountjoy Citation2021; The Netherlands: Oosterbeek and Webbink Citation2007; Romania: Malamud and Pop-Eleches Citation2010; Spain: Bellés-Obrero and Duchini Citation2021; Felgueroso, Gutiérrez-Domènech, and Jiménez-Martín Citation2014; Sweden: Hall Citation2012, Citation2016). In general, the results of these studies are mixed. Other types of studies look at the effect of separate vocationally oriented program types, such as the Career Academies in the US (Hemelt, Lenard, and Paeplow Citation2019; Kemple Citation2004; Kemple and Willner Citation2008, Citation2000), or the University Technical Colleges in England (Machin et al. Citation2020) comparing students attending these programs with their peers, who do not.

Our study is much closer to the first set of studies, looking at educational reforms, except that most of these explore the impact of decreased vocational but increased general training, whilst ours does the opposite. Looking at these country case studies, not all reforms delivered what had been expected of them. Most have mixed results, some of which are certainly not positive.

Hall (Citation2012, Citation2016), for instance, studies the pilot phase of a major education reform in Sweden in two different papers. The Swedish reform increased the academic content of the vocational tracks and offered students a path to universities. She finds that the reform increased attainment (number of years completed) but had no impact on tertiary-level outcomes or earnings. Moreover, the reform also increased the probability of dropout for students with low grades (GPA). Oosterbeek and Webbink (Citation2007) looked at a reform in the Netherlands in 1975, when the length of education increased in about half of the basic vocational schools from 3 to 4 years. They studied the effect of this change on wages in 1995 and showed that the returns to an additional year of vocational education did not exceed the returns to an additional year of labour market experience; that is, the net returns to education for vocational students are not positive. In a similar vein, Ollikainen and Karhunen (Citation2021) studied a Finish reform implemented between 1999 and 2001, where two-year vocational school programs were extended to three years and graduates could then apply to university. This meant that the general content of the new vocational track was increased relative to that of the vocational content. They showed that this change had no impact on the labour market outcomes or the chances of further education, but it did increase the dropout rate. As they argue ‘the results highlight a trade-off between higher demands placed on students and increased dropout rates’ (p.5).

From Malamud and Pop-Eleches (Citation2010) looked at a Romanian reform in 1973. In this reform students, who were born after 1959. January 1, were required to spend two more years in general education and it also shortened the length of their vocational training. They find no differences between the pre – and post-reform cohorts in their labour market participation or earnings, but post-reform cohorts were less likely to be employed as manual workers or craftsmen. Zilic (Citation2018) looked at another early reform in an East-European country, Croatia, where a two-year general training, common to all students, was introduced in all secondary-level programs. Thus, selection into vocational programs was postponed. However, all academic or general programs were assigned a vocational context (academic programs remained, but were placed under a school centre that had to have a vocational program). While he finds no effect for females, the reform increased the probability of completing elementary school but also decreased the probability of a having university education for male students. Zilic also finds that the reform did not significantly affect individuals’ labour market prospects.

Results from other vocational reforms are more positive. Bellés-Obrero and Duchini (Citation2021) studied a Spanish reform that decreased vocational tracking from age 14–16 and increased the compulsory age of schooling. The authors found that the reform increased the share of individuals with a general secondary or tertiary qualification, and decreased those with advanced vocational qualifications. The reform also increased average wages and the probability of being employed in a high-skilled occupation. However, all these positive effects were driven by middle to highly-educated individuals, while the reform significantly decreased the employment prospects of those with basic general education. Bertrand, Mogstad, and Mountjoy (Citation2021) looked at the reform of 1994 in Norway that changed the vocational education system in three ways. It improved the quality of vocational training by increasing the initial 3-year study to a 2 years general plus 2 years apprentice training system. It also broadened the vocational subject areas and integrated more general training elements in it, thereby improving the pathways between vocational and academic tracks, and, thirdly, added a feasible path to college. This ‘Reform 94’ increased the ratio of vocational students both among men and women and it also increased earnings and lowered crime in adulthood. Moreover, it reduced high school dropout among disadvantaged women. It did not reduce college-going among disadvantaged youth and it also did not meaningfully increase college enrolment among men, despite the easier pathways between academic and vocational tracks. Canaan (Citation2020) studied a de-tracking reform in France in 1977. Previously, students had been tracked at age 11 into different schools (general, technical and two vocational tracks). After the reform, this tracking has been postponed to age 13. However, within school (ability) grouping is increased. The overall, long-term effect of the reform was positive as it raised individuals’ wages at ages 40–45. In Italy, the length of vocational tracks has also been extended from two to three years after 2003. Here, too, the general content of the new vocational track was increased, which ceased the previous dead end structure and allowed graduates of the three year vocational track to further their studies. Comi, Grasseni, and Origo (Citation2022) shows that these changes speeded up the school-to-work transition in general, especially for women and immigrants.

Our analysis contributes to this country-specific line of the literature in that we study a national reform that has impacted the Hungarian vocational track. Contrary to the increases in the general content of the vocational track that has been apparent in most reforms, the Hungarian reform reduced the time spent on general subjects. We assess the short-term outcomes of this Hungarian vocational education reform that decreased the overall length of the secondary vocational track from 4 to 3 years while keeping the total amount of time spent on vocational subjects. We assume that this change should have had a direct negative effect on the general skills of the students, as they spend less time on these subjects, but shortening the time of training and tying it more to the labour market could also decrease dropout by decreasing the (time and effort) costs of obtaining a qualification.

Our contribution is twofold. We analyse a unique reform that went in the opposite direction compared to other reforms studied in the literature. Recent policy scenarios include various elements that suggest that vocational training move towards more practically (as opposed to general) oriented training (Cedefop Citation2016; Markowitsch and Bjørnåvold Citation2022). The analyzed Hungarian reform did just this. Looking at such alternative reforms will inform us of the expected effects of such scenarios. Secondly, the utilized data allows for the analysis of this reform on general skills (proxied with test scores) as well as on dropout and school completion. Two separate but equally interesting outcomes.

We use a difference-in-difference strategy (two-way fixed effects), where we compare a group of early adopter schools within the vocational track with the non-adopter schools affected by the reform. Our results indicate that decreasing the time spent on general subjects decreases general skills (reading and math), and shortening the time spent in school decreases early dropout and is likely to increase school completion in the future. Considering that decreased dropout/increased attainment increases the average employment probability of vocational graduates, while at the same time lower test scores decrease vocational track students’ employment probability, especially in the long run, the effects of this reform seem to be two-sided.

2. The reform

The Hungarian secondary education system is divided into three tracks, of which the vocational track is the only one that trains directly for the labour market with vocational qualifications offered at the successful exit. This is also the only track that does not allow graduates to apply for tertiary education. Little over 20% of each cohort of students enter these schools after the 8th grade of lower secondary (general) education. The social status of students as well as their level of performance is well below the two other tracks, the academic track, offering a maturity exam, and the technicum, which offers both pre-vocational education and the maturity exam (see Varga et al. Citation2021, indicators C2.4–C2.6 on participation and D1.1 on performance).

In 2013 the length of studies in the vocational track decreased from 4 to 3 years. Before the reform, the first two years (9th and 10th grade) were dedicated to general and pre-vocational education, while the 11th and 12th grades were devoted exclusively to vocational training and no general education was offered. After the reform, both general education and vocational training have been provided from grades 9–11, but the overall teaching time for general education has substantially decreased while the time spent on vocational education remained roughly the same. Before the reform, each mathematics, Hungarian language, and literature were taught at least three hours per week in the first two years. After the reform, two hours per week were assigned to each of these subjects in grade 9, and only one hour per week in grade 10, and there were no such subjects in grade 11 (see below).Footnote1 Besides the curriculum change, the education structure also changed in that vocational training could be offered in a dual (apprentice) structure during all three years, while before the reform, it was only possible in the last two years. The main rationale behind these changes was that students should have more practical vocationally oriented knowledge in their studies and make the transition to the labour market more quickly. Making the track more attractive for the students and decreasing the dropout rate has also been an explicit goal. Albeit there was no detailed official communication for the parts of the reform, we assume that the aim was to decrease learning costs for disadvantaged or low-ability students by decreasing the years spent in education and by decreasing the general content during the first years of the track and thus decrease dropout. By offering dual training from grade 9 the aim might have been to strengthen the ties between the school and the firms as well as offer work-based training even for the early dropouts.

Table 1. Allocation of general classes per week in the different grades before and after the reform.

Before the reform, schools could adopt the new school organization method (Bükki et al. Citation2012; Tárki-Tudok Citation2012). We call them early adopters. From 2010 schools could introduce programs that were one year shorter and focused more on vocational training and relatively less on general training. Unfortunately, we do not have precise school-level evidence on the year of early adoption of the 3-year training, but anecdotal evidence suggests that most early adopter schools opted for this shorter training in 2012, one year before the general reform. We use this group of early adopter schools as our control.

At the time of the reform, the compulsory age of education was 16 years in Hungary. Therefore, the 2012 pre-reform cohort had to stay in school for two years beyond the compulsory age to get a degree, while after the reform, it decreased to one year to complete secondary education.Footnote2 Thus the reform could have impacted dropout by decreasing (halving from two to one) the expected years of education students had to spend in schools after the compulsory age to get a secondary-level qualification.

3. Data

We use the National Assessment of Basic Competencies (NABC) (Sinka Citation2010) to test the reform's effect on general skills. We can assess the reform's effect on the dropout and school completion using the individual-level administrative panel database (Admin3) of the Centre for Economic and Regional Studies (Sebők Citation2019). We link these two datasets to the school-level administrative data (KIRSTAT), which we use to identify early adopter schools.Footnote3

The NABC database contains standardized reading literacy and mathematics test scores and various parental background measures of all 6th, 8th, and 10th-grade students since 2008. Mathematics and reading test scores were standardized to a 1500 mean and 200 standard deviation for the 2008/6th-grade cohort. All cohorts and grades are since linked to this mean and standard deviation so that both momentums of each cohort and grade are comparable. That is, for instance, if the 2010/6th-grade cohort – on average – scores higher than 1500, then their general skills are (measured to be) higher. We will use the linked 8th and 10th-grade panel to test the reform's effect on the value-added.

The Admin3 database is a 50% sample of the Hungarian population (above age 3) in 2003. The dataset contains individual-level anonymized monthly information on education, work, health, and other characteristics between 2003 and 2017.

The analytical sample consists of two cohorts of vocational track students who finished lower secondary (8th-grade) education in 2012 or 2013, right before and after the reform.Footnote4 The NABC sample consists of 13,938 students in the pre-reform and 12,502 in the post-reform cohort, while the Admin3 sample has 6762 pre-reform and 6084 post-reform observations.

4. Analytical strategy

Using a difference-in-difference strategy, we compare students from two groups of schools and two cohorts of students before and after the reform. Earlier pre-reform cohorts are not included in the sample as the compulsory age of education was decreased in 2012 (see Hermann Citation2020; Adamecz-Völgyi et al. Citation2021), and this might have interfered with the vocational reform, while later post-reform cohorts are omitted due to the lack of data after 2017.Footnote5

The basis of our analytical strategy is that early adopter schools were unaffected by the 2013 vocational reform, while all other vocational track schools were influenced by it. Hence comparing early adopters to reformed schools before and after the reform should show the causal impact of the reform, assuming that the reform was independent of the potential outcomes of the two groups of schools.

We have estimated the following regression:

(1)

where Y is the outcome variable for cohort c, school s, and individual i. REF is a dummy variable for the reform cohort, while VT4 is a dummy for students in the treatment (initially 4 years long) vocational track schools. Hence the reference category contains students before the reform in early adopter schools. The effect of the reform is shown by the β1 coefficient of the interaction term. X is a set of individual characteristics, such as gender, education level of father and mother, number of books at home, the disadvantaged status of the student, special education needs of the student, 8th-grade math and reading literacy test scores, and 8th-grade teacher given class-mark in mathematics (see the descriptive statistics in table A1 in the appendix). Asides from the test scores, all of these variables are categorical and were transformed into dummy variables, including the missing values. SC is a set of dummy variables denoting the separate vocational track schools (school fixed-effect).

Outcome variables are the 10th-grade mathematics and reading literacy test scores, dropout (student is not in education and has no finished secondary level qualification), and finished secondary degree. The latter two are dummy variables; hence we have estimated linear probability models.

‘Dropping-out’ and ‘finished secondary degree’ (completing school) are measured at two time points. Dropout is measured first three years and then four years after the start of secondary education. In this format, it is informative of the effects of the reform on the amount of schooling (did students go to school longer after the reform). Completing school is measured first at the expected date of school finishing, and then one year later. For the control group, the expected date of finishing school is 3 years after the 8th grade, while for the treatment group, it is 4 years after 8th-grade for the pre-reform cohort and 3 years for the post-reform cohort. Due to a lack of data after 2017, we cannot lengthen our period of observations.Footnote6

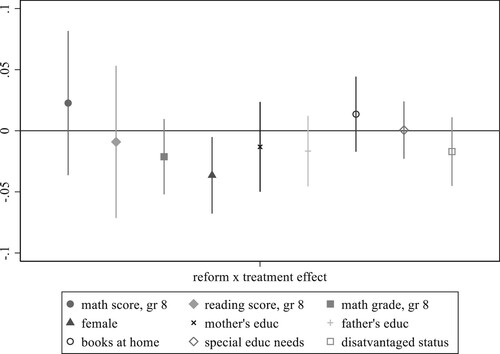

One of the core assumptions in our identification strategy is that the relative composition of the treatment and the control schools has not changed due to the reform. So students have not changed their school choice behaviour due to the reform. We have estimated a similar dif-in-dif regression to (1), with the separate control variables as dependent variables. . shows the coefficient plots for the β1 reform coefficient for the different regressions. The reform did not affect the composition of the students, as only the effect of the reform on gender seems to be marginally significant.

Figure 1. Estimated effect of the reform on student composition. Each coefficient is estimated in a separate regression. 95 per cent confidence intervals based on standard errors clustered at the school level. Parental education, books, and math grade denote low levels of the categorical variable. We have standardized the 8th-grade scores to 0 mean and 1 standard deviation here, to be able to fit the coefficients into this figure.

Unfortunately, due to the change in compulsory schooling in 2012 and our data limitations after 2017, we cannot test parallel trends in dropout or school completion. However, we can test the parallel trends on 10th-grade test score outcomes, as these are available for 3 more cohorts after the reform (post-trend) and were less likely to be affected by the change in compulsory age of schooling (students in 10th grade are 16-year-olds). We can also look at the composition of the treatment and the control schools in the long run. Figures A1 and A2 in the appendix show that albeit there were significant level differences between the early adopters (control) and the reform (treatment) schools throughout the years, the gap between them remained similar before the reform (see next section for a detailed discussion of the yearly differences in table A3). Figure A3. also shows that the student composition of the two groups (the share of mothers or fathers with low education, the number of books, and the share of disadvantaged, special education needs and female students) has changed similarly in the observed period.

5. Results and discussion

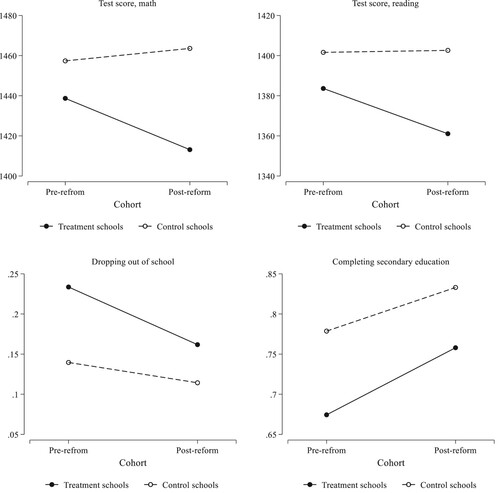

. depicts the averages of the different outcomes for the treatment and control groups before and after the reform. Students before the reform scored higher in both math and reading in both groups of schools, but the drop in test scores was much higher in the treatment schools. Also, dropout decreased while school completion increased after the reform, but the change was more pronounced in the treatment schools.

Figure 2. The mean of the outcome variables before and after the reform. Test scores are measured at grade 10; dropping out is measured four years after starting secondary education, and completing education is measured one year after the expected time of completing studies.

shows the β1 coefficients from six separate dif-in-dif regressions. Mathematics test scores of the treated schools have decreased by 31.24 points (cca. 0.15 standard deviation), while the reading test scores decreased by 20.04 points (cca. 0.1 standard deviation) due to the reform. This is a non-beneficial, negative effect of the reform.

Table 2. The effect of the vocational reform on test scores, dropout, and finishing school.

On the other hand, the reform has decreased dropout by 5.1 percentage points four years after starting secondary school. The difference measured three years after the start of secondary school is smaller and non-significant. Considering that the pre-reform dropout rate of non-treated vocational track students was 23.4 four years after starting school, 5.1 per cent is a moderate, non-negligible effect. We see that students in the treatment group are 6.4 percentage points less likely to have finished school in time, but this difference turns positive (3.5 percentage points but non-significant) one year after. This result implies that the share of students still in school one year after the expected finishing time increased by about 4 percentage points. Because some of them can be expected to complete their studies later, the reform is likely to increase secondary qualifications by more than 3.5 percentage points.

As a robustness check to the internal validity of our results, we have run the placebo tests on test score outcomes for the years before and after 2013 (table A3 in the appendix). That is, we have run the same regressions as in our main specification, but we always compare two adjacent cohorts from 2008 to 2009 until 2015–2016. Columns 9 and 10 in table A3 are the same as our main specifications (table A2 columns 1 and 2). We expect that there are no differences in the change of outcomes between our treatment and control groups in any two years besides 2012 and 2013. As can be seen, the biggest differences between the two groups of schools are between 2012 and 2013, when the reform happened, as we expected. However, there are also other significant ‘Reform x treatment group’ estimates in table A3. Namely, there is a smaller, but marginally significant (on the 10% level) negative change between the treated and control in 2009–2010, a larger positive and highly significant increase in math in 2011–2012 and also a largely positive but marginally significant (5% level) change in 2014–2015. All of these results can also be seen visually in figures A1 and A2.

The largest and most significant placebo coefficient (in 2011–2012) might be due to the early adopters. The control schools (early adopters) are self-selected. Schools could adopt the 3-year vocational structure from 2010 onwards. However, anecdotal evidence shows that most schools opted into this group in 2012 (one year before the main reform). Thus positive 2011–2012 placebo-treatment effect is likely to reflect the decrease in mathematics scores of the control group due to decreasing the length of studies from 4 to 3 years (which we see in figure A1). This way this coefficient is consistent with the estimated effect of the main reform.

The other 5% level significant change between 2014 and 2015 might only be a simple convergence between the treatment and control groups two years after the reform. That is, the treatment (late-adopters) have adopted the same teaching techniques, and school organisation as the early adopters, which caused their scores to increase. We have no explanation for the 2009–2010 change (small and marginally significant increase in differences between the two groups).

6. Conclusion

In this study, we assess the short-term outcomes of a Hungarian vocational education reform that decreased the overall length of the secondary vocational track from 4 to 3 years and also reduced the time spent on general subjects while keeping the amount of time spent on vocational subjects. Our results indicate that the reform has decreased the general skills (test scores) of vocational track students, but at the same time, it has decreased the probability of dropout and increased the probability of getting a secondary qualification, at least in the short run. Considering that decreased dropout/increased attainment increases the average employment probability of vocational graduates, while at the same time lower test scores decrease vocational track students’ employment probability, especially in the long run, the effects of this reform seem to be two-sided. Whether, on average, this reform will help or harm students’ labour market chances, in the long run, is subject to future research.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (172.2 KB)Acknowledgment

We thank Hedvig Horváth and seminar participants at the Quantitative Social Science Seminar of the University College London, the Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, and Corvinus University for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Of the total 4,5 classes allocated to general classes in grade 11, two were dedicated to a foreign language, one for the ‘head teacher’s class’ (osztályfőnöki óra ∼ weekly class for organizational issues) and 1,5 was freely available for the school to decide.

2 Assuming they have not repeated a grade previously.

3 Note that vocational schools can run various programs and might have become early adopters only in a portion of their programs. As we can only link students to schools and not to programs in the KIRSTAT, we have dropped these ‘mixed adopter’ schools from our sample. Running robustness checks with these ‘mixed adopter’ schools as an alternative control category shows that their outcomes are in between the treatment and the control (fully early adopter) schools.

4 We link 8th and 10th grade testscores on the individual level, allowing for one year of grade repetition in 9th grade; i.e. we link the 2012 8th grade sample to the 2014 and 2015 10th grade data, and the 2013 8th grade sample to the 2015 and 2016 10th grade data

5 Using an alternative (somewhat inferior) identification strategy (comparing vocational track schools to schools offering maturity exam, and hence unaffected by the reform) and looking at only test score outcomes of the NABC data in 10th grade, when the drop in the age of compulsory education is less of an issue, we have used a longer before-after window, and results were very similar (Hermann, Horn, and Tordai Citation2019).

6 Note that these outcomes are observed only for those, who had not dropped out before the 10th grade. The reason for this is that we can only observe the track of the student at grade 10. Hence, if someone is only observed in grade 8 in our sample, but not in grade 10, then we cannot identify their track. We tested for the change in the ratio of vocational track students before and after the reform in grade 10, and it has not changed. The ratio of students in early adopter schools before the reform was 41,57%, while after the reform it was 41,27%. The ratio of students in non early adopter schools before the reform was 26,92%, while after the reform it was 26,36%. The remaining students attended schools that provided both 3 and 4 years long programmes before the reform. These ‘mixed-adopter’ schools were excluded from the analysis.

References

- Adamecz-Völgyi, A., D. Princz, Á Szabó-Morvai, and V. Suncica. 2021. “The Labor Market and Fertility Impacts of Decreasing the Compulsory Schooling Age.” KRTK-KTI Working Papers 2021 (40): 1–34.

- Bellés-Obrero, C., and E. Duchini. 2021. “Who Benefits from General Knowledge?” Economics of Education Review 85: 102122. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102122.

- Bertrand, M., M. Mogstad, and J. Mountjoy. 2021. “Improving Educational Pathways to Social Mobility: Evidence from Norway’s Reform 94.” Journal of Labor Economics 39: 965–1010. doi:10.1086/713009.

- Bükki, E., K. Domján, G. Mártonfi, and L. Vinczéné Fekete. 2012. A szakképzés Magyarországon - ReferNet országjelentés. Budapest.

- Canaan, S. 2020. “The Long-run Effects of Reducing Early School Tracking.” Journal of Public Economics 187: 104206. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104206.

- Cedefop. 2016. “Leaving Education Early: Putting Vocational Education and Training Centre Stage.” Cedefop Research Paper 143. doi:10.2801/893397.

- Comi, S. L., M. Grasseni, and F. Origo. 2022. “Sometimes it Works: The Effect of a Reform of the Short Vocational Track on School-to-Work Transition.” International Journal of Manpower, doi:10.1108/IJM-06-2021-0391.

- Felgueroso, F., M. Gutiérrez-Domènech, and S. Jiménez-Martín. 2014. “Dropout Trends and Educational Reforms: The Role of the LOGSE in Spain.” IZA Journal of Labor Policy 3: 9. doi:10.1186/2193-9004-3-9.

- Field, E. M., L. L. Linden, O. Malamud, D. Rubenson, and S.-Y. Wang. 2019. “Does Vocational Education Work? Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Mongolia” Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Mongolia. Working Paper Series, doi:10.3386/w26092.

- Hall, C. 2012. “The Effects of Reducing Tracking in Upper Secondary School Evidence from a Large-Scale Pilot Scheme.” J. Human Resources 47: 237–269. doi:10.3368/jhr.47.1.237.

- Hall, C. 2016. “Does More General Education Reduce the Risk of Future Unemployment? Evidence from an Expansion of Vocational Upper Secondary Education.” Economics of Education Review 52: 251–271. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.03.005.

- Hampf, F., and L. Woessmann. 2017. “Vocational vs. General Education and Employment Over the Life Cycle: New Evidence from PIAAC.” CESifo Economic Studies 63: 255–269. doi:10.1093/cesifo/ifx012.

- Hanushek, E. A., G. Schwerdt, L. Woessmann, and L. Zhang. 2017. “General Education, Vocational Education, and Labor-Market Outcomes Over the Lifecycle.” Journal of Human Resources 52: 48–87. doi:10.3368/jhr.52.1.0415-7074R.

- Hemelt, S. W., M. A. Lenard, and C. G. Paeplow. 2019. “Building Bridges to Life After High School: Contemporary Career Academies and Student Outcomes.” Economics of Education Review 68: 161–178. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.08.005.

- Hermann, Z. 2020. “The Impact of Decreasing Compulsory School Leaving age on Dropping out of School.” In The Hungarian Labour Market 2019, edited by K. Fazekas, M. Csillag, Z. Hermann, and Á. Scharle, 70–78. Budapest: Hungary.

- Hermann, Z., D. Horn, and D. Tordai. 2019. “The Effect of the 2013 Vocational Education Reform on Student Achievement.” In The Hungarian Labor Market 2019, edited by K. Fazekas, M. Csillag, Z. Hermann, and Á. Scharle, 64–69. Budapest: Institute of Economics, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies.

- Kemple, J. J. 2004. Career Academies: Impacts on Labor Market Outcomes and Educational Attainment. MDRC.

- Kemple, J. J., and C. J. Willner. 2000. Career Academies: Impacts on Students’ Engagement and Performance in High School. MDRC.

- Kemple, J. J., and C. J. Willner. 2008. Career Academies: Long-Term Impacts on Labor Market Outcomes, Educational Attainment, and Transitions to Adulthood. MDRC.

- Machin, S. J., S. McNally, C. Terrier, and G. Ventura. 2020. “Closing the Gap Between Vocational and General Education? Evidence from University Technical Colleges in England” SSRN Electronic Journal, doi:10.2139/ssrn.3728420.

- Malamud, O., and C. Pop-Eleches. 2010. “General Education Versus Vocational Training: Evidence from an Economy in Transition.” Review of Economics and Statistics 92: 43–60. doi:10.1162/rest.2009.11339.

- Markowitsch, J., and J. Bjørnåvold. 2022. “Scenarios for Vocational Education and Training in Europe in the 21st Century.” Hungarian Educational Research Journal 12: 235–247. doi:10.1556/063.2021.00116.

- OECD. 2019. Getting Skills Right: Future-Ready Adult Learning Systems. Paris, France: OECD.

- Ollikainen, J.-P., and H. Karhunen. 2021. “A Tale of Two Trade-Offs: Effects of Opening Pathways from Vocational to Higher Education.” Economics Letters 205: 109945. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2021.109945.

- Oosterbeek, H., and D. Webbink. 2007. “Wage Effects of An Extra Year of Basic Vocational Education.” Economics of Education Review 26: 408–419. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2006.07.013.

- Piopiunik, M., and P. Ryan. 2012. Improving The Transition Between Education/Training and The Labour Market: What Can We Learn from Various National Approaches? EENEE Analytical Report.

- Ryan, P. 2001. “The School-to-Work Transition: A Cross-National Perspective.” Journal of Economic Literature 39: 34–92. doi:10.1257/jel.39.1.34

- Sebők, A. 2019. “A KRTK Adatbank Kapcsolt Államigazgatási Paneladatbázisa.” Közgazdasági Szemle, 1230–1236. doi:10.18414/KSZ.2019.11.1230

- Sinka, E. 2010. OECD Review on Evaluation and Assessment Frameworks for Improving School Outcomes. HUNGARY. Country Background Report.

- Tárki-Tudok. 2012. Előrehozott szakképzés. Záró Tanulmány.

- Varga, J., T. Hajdu, Z. Hermann, D. Horn, and H. Hönich. 2021. A Közoktatás Indikátorrednszere 2021 (No. 4). KRTK Közgazdaságtudományi Intézet. Budapest: Hungary.

- Wolter, S. C., and P. Ryan. 2011. “Apprenticeship.” In Handbook of the Economics of Education, edited by S. M. Eric A. Hanushek, and L. Woessmann, 521–576. Elsevier.

- Zilic, I. 2018. “General Versus Vocational Education: Lessons from A Quasi-Experiment in Croatia.” Economics of Education Review 62: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.10.009.