ABSTRACT

Today, most museums in Europe and the United States present themselves as democratic institutions. Meanwhile, scholarly literature puts much emphasis on the democratising potential of social media for museum practice. Prompted by the scarcity of factual data on museums’ employment of social media, this article presents an empirical study on how art museums use Instagram. Specifically, the research focuses on the extent to, and the ways in which, art museums are harnessing Instagram in order to fulfil their democratic aspirations. Through content analysis, the study shows that Instagram’s potential for a more democratic museology is being harnessed to a very limited extent. Museums predominantly use Instagram for more traditional promotional purposes or adopt an authoritative knowledge-telling attitude in their posts. Nevertheless, we present several promising exceptions, that we analyse through close reading. These examples pave the way to a more democratic museum practice on Instagram.

Introduction

The idea of the democratic museum is virtually omnipresent among scholars, policy makers and museum professionals (see Barret Citation2011; Black Citation2015; Hooper-Greenhill Citation1994; Marstine, Dodd, and Jones Citation2015; Council of Europe Citation2005; ICOM Citation2017). To remain relevant in contemporary democratic societies, museums need to make their existence meaningful to all audiences, including those who have traditionally felt excluded by art museums (Black Citation2015), and they need to communicate with audiences in mutual directions (Hagedorn-Saupe, Kampshulte, and Nouschka-Roos Citation2013).

In this discussion, one theme is particularly recurrent: the potential of the Internet for a more democratic museum practice (see Iversen and Smith Citation2012; Kelly Citation2013; Marselis and Schutze Citation2013; Meecham Citation2013). Social media in particular are regarded as pivotal means to fulfil the democratic aims that most museums claim to have, thanks to their people-centred, participatory and inclusive nature. The lockdowns following the Covid-19 pandemic in many countries in 2020 and 2021, turned the spotlight on social media museology even further. Institutions were forced to carry on their missions exclusively virtually (ICOM Citation2020), resulting in a vast increase of social media posts, a small increase of account followers and more diverse types of posts (see Agostino, Arnaboldi, and Lampis Citation2020; cf. Gribbon Citation2021; Ou Citation2020; Potts Citation2020; Samaroudi, Rodriguez Echavarria, and Perry Citation2020).

Despite the strong theorisation on how museums should use social media, though, empirical research on museums’ actual use of social media is lagging behind (cf. Suh Citation2020; Suzić, Stříteský, and Karlíček Citation2016). Most of the existing literature focuses on the perspective of museum professionals (Booth, Ogundipe, and Røyseng Citation2020; Fletcher and Lee Citation2012; Lotina Citation2014), specific case studies (Badell Citation2015; Wong Citation2011) or audience groups that are often excluded (McMillen and Alter Citation2017; Stuedahl and Smørdal Citation2015). Only few authors engaged in a systematic analysis of social media posts published by museums: Gerrard, Sykora, and Jackson (Citation2017) performed a quantitative computational processing of data from Twitter museums’ accounts; Ruggiero, Lombardi, and Russo (Citation2021) assessed, through content analysis of museums’ Facebook posts, that communication is still unilateral and promotional, while Suzić, Stříteský, and Karlíček (Citation2016) performed a structural and semantic analysis of Facebook posts by museums in Berlin and Prague, to conclude that social media are primarily used for branding and promotional activities. It is Gronemann, Kristiansen, and Drotner (Citation2015) who provided the most comprehensive study to date, by analysing through discourse analysis both the types of Facebook posts and the interaction chains that follow. They demonstrate how dialogic modes of interaction mainly result when museums harness audience knowledge resources.

Studies focusing on Instagram – a platform on which art museums are quite active – are even scarcer, but are gradually growing in number. Instagram is an interesting medium for museums, because of its rapidly growing worldwide use among a large – relatively young and ethnically and socially diverse – audience (Laestadius Citation2016), and because of its visual nature, compared to Facebook and Twitter. Regarding Instagram, there are some interesting studies that focus on visitor-generated content (Amanatidis et al. Citation2020; Arias Citation2018; Budge and Burness Citation2018; Weilenmann, Hillman, and Jungselius Citation2013), co-creation by teens to foster engagement (Scott Citation2017), the crowdsourcing of images for an exhibition (Rao Citation2017), and marketing tools to maximise a museum’s visibility and reach (Smith Citation2015). Jarreau, Dahmen, and Jones (Citation2019) were the first ones to perform a content analysis of actual Instagram posts, but they focus on science and technology museums and do not engage with the notion of the democratic museum (cf. Gribbon Citation2021).Footnote1 The actual content of art museums’ Instagram accounts, however, has not received any scholarly attention.

In order to fill this gap, this article presents a content analysis of 400 Instagram posts by 8 art museums in Europe and the US published in early 2019, hence before the pandemic caused a worldwide rethinking of digital possibilities. We studied what are the main practices undertaken on Instagram by art museums with democratic aspirations, and which of these practices can actually be considered democratising. It will show that such truly democratic practices are relatively scarce, as more traditional museum practices still prevail. Subsequently, the article offers a close reading of three posts that are illustrative of practices which, if implemented more widely, could lead to more democratic uses of Instagram.

The democratic museum

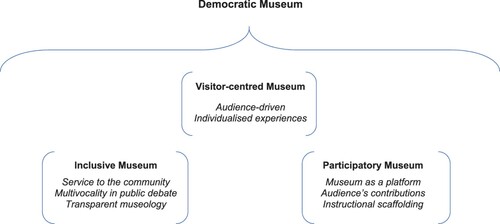

When talking about the democratic museum, we follow the definition of democracy held by the United Nations (Citation2020), which considers democratic governance as ‘a set of values and principles that should be followed for greater participation, equality, security and human development’. The belief that museums should be democratic institutions gradually emerged over the last few decades, turning away from the model of museums born after the French Revolution which aimed at the construction of a unified and univocal national memory through an authoritative and knowledge-telling attitude (Brown and Mairesse Citation2018, 528). From 1970, the ICOM (Citation1970) has considered museums as institutions for laypeople and as agents of societal development. Using Barret’s words, we can consider the contemporary democratic museum an institution that supports processes of democracy by facilitating public debate in an inclusive yet monitored environment (Barret Citation2011). Today, in the literature on the democratic museum, three words are recurrent, which often seem to be used interchangeably: inclusive, visitor-centred and participative. We will disentangle these related concepts, while in this research we understand the term ‘democratic museum’ as an umbrella term for museums which adopt at least one of these practices (see ).

The first notion, of the inclusive museum, was developed in reaction to the view of museums as exclusive and elitist institutions, where prevailing social practices are reproduced and social differences are thus legitimated (e.g., Bourdieu Citation1984). Instead, drawing on Cotton Dana (Citation1920), supporters of the inclusive museum argue that museums should be of service to their communities, meaning that the majority of residents should be able to easily visit them. Furthermore, museums should bring objects and activities outside the physical confinements of their walls, and should be permeable to ideas coming from those generally excluded by the museum (Hudson Citation1975). Over the last few decades, museums moved from Bourdieu’s class-based definition of inclusivity to a broader conceptualisation of the term, which encompasses issues of, for instance, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, disability, religious faith and so on (Sandell Citation2007). A related issue is the plea for a more ‘transparent’ way of making exhibitions, which does not impose on the artwork any univocal interpretation attributed to it by an established authority (Vergo Citation1989, 48). Instead, museums should embed many different, and perhaps conflicting, views, interests and perspectives, while being self-reflective on the arbitrariness of their curatorial work.

Second, the idea of the visitor-centred museum gained popularity thanks to Falk and Dierking’s The Museum Experience in 1992, which shifted the point of view from the institution’s perspective to the audience’s perspective. They argued – drawing on Cotton Dana, too – that museum professionals do not have control over visitors’ experiences, since every individual experience is different. This depends on the personal and socio-cultural context, but also on the physical context, which ‘includes the architecture and the ‘feel’ of the building, as well as the objects and the artefacts contained in it’ (Falk and Dierking Citation2013, 28). In a time in which the cultural sector has to compete with other leisure industries which fully embrace the experience economy mantra (Pine and Gilmore Citation1998), museums are increasingly branding themselves as providers of cultural and leisure experiences. These include all types of events inside the museum walls, alongside traditional visits. However, a true democratic museum should not overstress such practice at the cost of its core educational mission (Balloffet, Courvoisier, and Lagier Citation2014).

Finally, in the participatory museum, visitors not only take centre stage, but they are also encouraged to participate, to talk back, to deliver meaningful input. Such opportunities contribute further to the demise of authoritative, univocal interpretations by the museums themselves. Simon (Citation2010), in particular, has propagated this type of museum. She argues that such possibilities should be balanced with constraints, as open-ended self-expression is likely to produce unrewarding outputs. In Simon’s view, participatory activities should rest on the idea of ‘instructional scaffolding’, where educators provide visitors with enough input to develop personal skills and competencies, while the outcomes of their participation are not prescribed. Also, Simon argues, these outcomes should be taken into consideration by the institution, by showing responsiveness to participants’ contributions, such as evolving in response to what participants suggest or creating crowd-sourced exhibits.

The democratic museum online

In the discourse around the democratic museum, much emphasis is put on the democratising potential of the Internet. The Internet’s relation to museology has been discussed systematically since 1997, when the convention The Museum and the Web was first held to explore the Internet as a new platform to engage audiences and participants (Museweb Citation2020). Today, a large group of scholars sees the Internet and its promises of digital democracy as a powerful tool in the hands of the democratic museum. Among this group the enthusiastic perspective of Meecham (Citation2013) stands out, who argues that digital technologies can cause a shift in power relations between the established authorities and the public in a democratic sense (cf. Fairclough Citation2012).

However, whereas some enthusiastically embrace the transformation offered by the internet as if it has already happened, others warn that its democratising potential has not been actually employed yet (Gronemann, Kristiansen, and Drotner Citation2015; Henning Citation2006; Hull and Scott Citation2013; Jarreau, Dahmen, and Jones Citation2019; Kidd Citation2011; Parry Citation2013; Russo Citation2012; Silberman and Purser Citation2012). In particular, Parry (Citation2013) points out that, compared to the rest of the Internet, museums remain fairly conservative in their online practices, by embracing a heavily information-oriented approach and emphasising their curatorial and interpretative role. Hull and Scott (Citation2013, 132) call this the ‘knowledge-telling mode’. Kidd (Citation2011) argues that the museums’ intentions are often not aligned with the audience’s perceptions.

So what could museums do to fully harness the democratising potential of the Internet? The discussion on this issue centres around five main themes. First, social media serve the aims of the inclusive museum in that they afford a broader engagement with the museum’s communities (Higgins Citation2015; Kelly Citation2013; Meecham Citation2013; Russo Citation2012). More particularly, they provide an opportunity for those who are often excluded – such as people between 18 and 30 years old – to accidentally stumble on museum content (Arnold Citation2015; Bell and Ippolito Citation2015). Second, social media provide museums with the infrastructure to sustain active participation (Davidson Citation2015; Fairclough Citation2012; Giaccardi Citation2012; Iversen and Smith Citation2012; Kelly Citation2013; Reeve and Woollard Citation2015; Russo Citation2012; Wellington and Oliver Citation2015), by attempting a bi-directional knowledge exchange with its audience (Drotner and Schrøder Citation2013; Kidd Citation2011; Gronemann, Kristiansen, and Drotner Citation2015). Third, the participatory and inclusive museum come together by fostering multivocality. This means allowing different perspectives in the same online space without giving predominance to any of them (Barret Citation2011; Giaccardi Citation2012; Hull and Scott Citation2013; Meecham Citation2013; Silberman and Purser Citation2012). Fourth, regarding the visitor-centred museum, the role attributed to museum objects is disputed. Hagedorn-Saupe, Kampshulte, and Nouschka-Roos (Citation2013) and Hull and Scott (Citation2013) claim that users should not only be the recipient of information, but they should be supported in engaging with digitised museum objects actively and becoming architects of their own learning experience. Finally, the visitor-centred museum comes to the fore in the possibility of personalising the museum experience. Social media are assumed to provide tools to meet the individual interests of the audience while enabling users to contribute something personal to the museum experience (Parry Citation2013).

Materials and methods

In order to capture the actual ways in which art museums use Instagram, we performed a quantitative content analysis of 400 Instagram posts of 8 different art museums. This enabled us to quantitatively analyse the presence and variation of types of posts and modes of communication within a certain time period. Subsequently, we analysed three particular posts through a more qualitative reading, to delve deeper into actual practices and to provide examples of a truly democratic use of social media.

The 8 selected museums are situated in either the US or Europe, which are the main sources of theorisation around the democratic museum and its use of social media that we referred to. Museums were eligible for selection when they displayed democratic aspirations on their websites and in their mission statements (see British Museum Citation2019; MoMA Citation2019; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca Citation2019; Rijksmuseum Citation2019; Kunsthal Citation2019; Pioneer Works Citation2019; Guggenheim Bilbao Citation2019; Museo del Novecento Citation2019). For the selection we applied purposeful sampling: rather than being statistically representative, the museums are diverse in several ways, as we were aiming for diversity rather than comparison or generalisation. Three variables were taken into account: the museum’s mode of governance (public or private), its size and whether or not it has a permanent collection. Furthermore, the museums differ in regard to seniority and the relative emphasis on art compared to heritage. These considerations resulted in the 8 museums that are presented in .

Table 1. Museums in the sample.

For each museum, we selected the 50 most recent Instagram posts that had been published by 4 April 2019, within a mean time period of 68 days.Footnote2 Each post was considered as a unit of analysis, meaning that both the image(s) or video and the accompanying text were analysed. The unity of visual and textual analysis is pivotal to fully make sense of Instagram data (Laestadius Citation2016). In order to limit down our data collection, we focused on museums’ posts, such as attempts to foster interaction, without including visitors’ actual reactions, such as the number of likes and the types of responses. However pivotal to the communication process, such a methodological approach would lack the descriptive richness of our content analysis. Hence, it is a study on museums’ initial practices rather than on the full communication chain that ideally occurs (see for such a full account in the case of Facebook: Gronemann, Kristiansen, and Drotner Citation2015).

Both the actual subject of the post and the mode of communication were coded. The former often – but not necessarily – comes down to the picture/video, such as a museum object or visitors, while the latter is usually found in the caption: e.g., providing information on an artwork or fostering interaction. For the coding process we adopted a combined deductive and inductive approach: while our theorisation and the focus of our research question called for a top-down approach, the integration with bottom-up coding led to the conceptual refinement of our categories. Hence, codes were partly derived from literature on the corporate use of Instagram (McNely Citation2012) and on the three aspects of democratic museums discussed above, and partly emerged from the data during a pilot coding session of 80 posts. For example, this pilot session made us distinguish posts simply fostering interaction from posts providing proper instructional scaffolding. This resulted in 10 different codes for the posts’ subjects and 11 for the modes of communication (explained in and ) for the eventual deductive analysis. Each post was attributed one code for its – mutually exclusive – subject and either one or two codes for its – often coexisting – modes of communication.Footnote3

Table 2. Subjects of the Instagram posts.

Table 3. Communication modes in the Instagram posts (One or two codes per post).

An inter-coder reliability test with two extra coders, who – after a thorough instruction and training session – both coded a random sample of 50 posts, resulted in a similar distribution of frequencies. However, not all individual codes appeared to be equally reliable, as some posts, particularly those with longer captions, often allow more than one undisputed interpretation.Footnote4 However, we will focus our discussion of the results not on the frequencies per individual museum, but on general tendencies, museums that stand out and, above all, pivotal examples of good practices.

Results

Quantitative analysis

and present the percentages of each subject and mode of communication in all 8 museums. Drawing on the literature presented above, each code was considered representative either of a more traditional model of curation, authoritative and unidirectional, or of a more democratic museum practice. The tables also show each code’s median value for the 8 museums, in order to correct for statistical outliers.

Subjects

Let us first consider the posts’ subjects. shows that by far the most common subject, making up almost half of all Instagram posts in our sample, is the depiction of (part of) a museum object, such as a painting or a performance.Footnote5 This is not equally distributed, though. It is particularly the three largest museums (MoMA, British Museum, Rijksmuseum) that make a habit of displaying an object from their rich collections (over 60% of all the posts by these museums), whereas three of the smallest museums do so far less. To what degree this practice can be considered truly democratic, depends on the mode of communication employed, and will therefore be discussed below. The only type of post that we unequivocally associated to a more traditional modern of curation is place making (4.3%), which stresses the prestige and hence the authority of the institution.

Almost half of the posts display subjects that we label as potentially apt for democratic museology, although we will see below that the accompanying communication mode is essential to truly count as such. A large proportion consists of visitor-centred posts. This particularly counts for explicit reposts of visitors’ posts on their private Instagram accounts. However, two museums outweigh all others in this practice: the Museo del Novecento (half of their posts) and the British Museum (28%). Other visitor-centred practices involve the actual picturing of museum visitors or a larger museum space. Visitors are also sometimes pictured in events inside the museum space, such as DJ sets, and in workshops, which involve the visitors’ active participation in cultural activities. As a result, Instagram users get the idea of an engaging institution where the audience has a primary role in determining the nature and outputs of museum activities. Finally, all museums sometimes give a glimpse behind the scenes, making the museum practice more transparent and thereby potentially more inclusive.

Communication modes

As anticipated, the type of subjects in Instagram posts alone rarely tells the whole story, as the museums’ aims in posting on Instagram become clear only through carefully studying the interplay between visual and textual information. In our analysis, the mode of communication is always the determining factor in the distinction between traditional and more democratic museology on Instagram. The distribution of each mode of communication, presented in , shows that democratic curatorial practices are actually less common on museums’ Instagram accounts than the coding of subjects as such potentially seemed to suggest.

The most frequent aim of Instagram posts is – when added up – advertising. Reasonably, museums take advantage of social media as an additional marketing tool to attract visitors to their entrance gates. The main content advertised is temporary exhibitions that are opening or closing soon. Permanent collections are advertised less often, even if one takes into account the absence of such collections in three of the observed museums (cf. Kidd Citation2011; Ruggiero, Lombardi, and Russo Citation2021; Suzić, Stříteský, and Karlíček Citation2016). Furthermore, particular events within the museum space are often promoted, such as lectures, parties and workshops. While workshops and events may be visitor-centred on-site practices, we consider its sheer promotion on Instagram as a traditional museum practice, as this remains a top-down communication mode. Furthermore, limiting Instagram’s potential to a tool to bring visitors to the physical space of the museum means overlooking the possibilities for active learning offered by the digital environment.

The second most frequent mode of communication, often co-occurring with the former, is knowledge-telling, the unidirectional providing of information about an object or exhibition.Footnote6 This communication mode is the epitome of an object-centred model of curation, opposed to the object-as-a-prompt model which encourages active learning and meaning-making on behalf of visitors. Particularly the more traditional and conservational museums in our sample, the British Museum and the Rijksmuseum, apply such teaching methods. However informative these lessons may be, when museums put themselves between the object and the public in a unidirectional way (cf. Henning Citation2006) and do not provide much opportunity for individual meaning-making, the democratising effect of such practices can be questioned. Such art lessons might even turn out very elitist in practice, despite the desire to inclusively reach a broader audience through a presence on Instagram.

A mode of communication that does try to reach a more inclusive audience but that we do not perceive as a truly democratic practice, is humanising: emotionally engaging with the audience on a personal level, in order to strengthen their commitment to the museum. Though this may sound similar to the visitor-centred mode of communication, such posts do not include much cultural content, but focus instead on informal, off-topic messages, such as wishing everyone a nice weekend, or using a holiday like Valentine’s Day for a connection with a specific artwork.

In order to engage Instagram users in a more active way, museums can actively foster interaction in relation to artworks. However, while one would expect the main goal of museums’ activities on a social medium such as Instagram to be to increase audience participation, it occurs on average in only about 10% of all examined posts – in half of the accounts the percentage even drops below 5.Footnote7 Furthermore, in most cases this method is adopted in a quite superficial way. The British Museum encourages its followers to get involved most frequently (42%), yet often with questions as ‘What’s the weather like where you are?’Footnote8 Occasionally, questions do involve cultural content, but when they take the form of a quiz (e.g., ‘Who created this painting?’, followed by a number of possible answersFootnote9), the authoritative way of teaching is not left behind.

As Simon (Citation2010) argued, a more comprehensive way of fostering interaction is instructional scaffolding: providing some guidance and sustenance for visitors to develop a meaningful answer, while not prescribing the outcomes. This, however, rarely occurs (cf. Gronemann, Kristiansen, and Drotner Citation2015). The same goes for some more inclusive modes of communication: addressing socio-political issues, providing multivocality and engaging in self-reflection. Although more traditional ways of communication still remain worthwhile, we do want to argue for an intensification of more specifically democratic practices that could bring institutions closer to the hard-to-reach audience. The next section will give more in-depth analyses of such rare practices, in order to illustrate the possibilities that other museums might embrace.

Qualitative analysis

The posts presented in this section are considered good empirical examples of current museum practices which, if implemented more widely, could restructure the use of Instagram in a more democratic sense. In line with our theoretical framework, this sample of posts is meant to explore the different ways in which a post can fulfil the aspiration of post-modern curation – that is, by being participatory, inclusive or visitor-centred.

Instructional scaffolding and self-reflection

We consider the post published by the MoMA on 21 March 2019 an interesting object of inquiry, because it provides an example of how digitised museum objects can be used on Instagram as a base for instructional scaffolding.Footnote10 As instructional scaffolding fosters personal meaning-making and prompts public discussion, it is the best form of participatory experience a museum account can provide. The visual part of the post consists of two shots of the 1941 MoMA exhibition ‘Organic Design in Home Furnishing’. The first picture features, in the foreground, three partially disassembled armchairs hanging on the wall. The second picture features a single chair, pictured from two different angles which highlight the sophisticated details of this design product. Its refinement clashes with the anonymous look of the disassembled chairs, subtly inciting Instagram users to draw a comparison. The incitement to draw a comparison is made explicit in the caption, where the first armchair is defined as ‘overstuffed’, as opposed to the second armchair, which was ‘created to give the sitter maximum support while avoiding heavy construction and cumbersome upholstery’. Through these descriptions, the post gives Instagram users some means to interpret the two armchairs. In other words, the descriptions scaffold the users’ meaning-making process, providing guidance for developing a personal interpretation of these museum objects.

Subsequently, through the open question ‘Which chair supports your design values?’, users are prompted to finalise and contribute their personal interpretation. It must be noted that, as in every well-scaffolded participatory activity, the question limits users’ interpretative activity to a very specific issue. Yet, it allows more than one possible answer. Put in another way, the museum account’s role becomes that of a facilitator that, making participation meaningful for the users, harnesses Instagram’s potential as a platform for the exchange of ideas.

As for the post’s inclusive character, it also provides some form of self-reflection on museum practice, as it indirectly invites users to assess the MoMA’s curatorial work throughout its history. Specifying in the copy that the aim of the curators of this 1941 exhibition was ‘to crusade against’ the first armchairs’ ‘horrible’ features, the museum makes very clear that exhibition design is not an objective business at all. Rather, museum professionals tend to impose specific narratives on the reading of museum objects. The idea that curators can be quite impartial in imposing these narratives is accentuated by the sharp irony in the curators’ reported words – which, for example, describe the first armchair’s design as devouring ‘small flora and fauna of the domestic jungle’. Presenting the museum’s interpretation of collection objects as biased is more inclusive than it might appear at first glance. Indeed, recognising its supposed impartiality, the museum admits that the interpretation it once provided is not the only interpretation. By asking Instagram users ‘Which chair supports your design values?’, it also proves itself open to incorporating conflicting interpretations in the discussion. In sum, with one single post, the MoMA attempts to be more transparent regarding the social messages it promoted throughout its history, and attempts to create a sphere for public debate on Instagram which is, at once, participative and inclusive.

Socio-political issues

The post published by the MoMa on 7 March 2019 exemplifies a way in which museums, by carrying out socio-political activism on Instagram and giving voice to under-represented social groups, can shape their image as more inclusive places.Footnote11 The post pays tribute to the artist Carolee Schneeman, who had died a day earlier. The visual of the post consists of a short video in which Schneeman stands in front of one of her ‘kinetic paintings’, turns it upside down and makes it spin on the wall. The whole scene is connoted as something ground-breaking, as it breaks the ‘look and do not touch’ convention of art museums where paintings are supposed to hang on the walls without being moved. The focus on the disruptive character of the act is restated by the caption, which says: ‘Today, we celebrate the life of a woman who turned the art world upside down’. Then, bringing into focus the far-reaching influence of her work, it adds: ‘#CaroleeSchneemann leaves behind a legacy of ground-breaking innovations in performance, film, and installations. Join us in remembering a true radical’. With this, the whole post qualifies as a celebration of the artist’s radical actions that yielded consistent advancements in the art world.

Yet, the scope of Schneemann’s actions is brought even further. Transcending the limits of the art world, her artistic innovations are framed, in all respects, as important for society as a whole. Indeed, the caption reports the following quote by Schneemann: ‘I had no precedent in being valued. Everything that came from a woman’s experience was considered trivial. I wasn’t sure if my work would shift that paradigm or not, but I had to try.’ With this, through her own voice, her work as a woman artist is framed in the wider context of women’s rights activism. Her attempt to push boundaries in the art world is seen as a plea for greater representation and dignification of the female figure in society. Apparently, this claim is supported by the MoMA which, by giving visibility to Schneemann’s advocacy and successes on its Instagram account, amplifies the reach of her work. The museum’s online space is thus employed to voice the claims of a traditionally underrepresented social group. Championing the advancement of women’s rights, the institution takes action to foster a societal development – thus giving shape to its Instagram account as an inclusive space of debate where important social issues can be tackled.

Reposts and multivocality

Museum accounts can employ reposts in order to represent a museum visit through the eyes of the visitor. In particular, the repost published by the Museo del Novecento on 16 March 2019 exemplifies the meaning-making process undertaken by a visitor within the museum walls.Footnote12 By posting it on Instagram, the museum legitimates the visitor’s interpretation of the art object. This repost, in particular, is focused on Piero Manzoni’s artwork Merde d’Artiste. The picture is shot from the side, from a rather high angle. In such a way, the attention is focused on a detail of this exemplar of Merde d’Artiste, namely a dent on the tin can. Drawing on the work of Budge and Burness (Citation2018), the peculiar angle and focus of the photography can be considered to represent the gaze of the visitor who posted the picture originally. It proposes his peculiar way of approaching the artwork, focusing on certain details and leaving out others; basically, it reproduces his way of making sense of the museum object. Therefore, by reposting such a picture, the museum gives visibility to a meaning-making experience that, rather than common and standardised, is peculiar and individualised. Also, it accepts this meaning-making experience as valuable.

Museo del Novecento indeed refuses to authoritatively provide the interpretation of the artwork. Rather than adopting a knowledge-telling attitude, the museum uses the caption to add another voice to the interpretation of Manzoni’s work. The caption quotes a line from a song by the Italian band Baustelle in which the artist is praised, adding ‘This is what, right in the middle of the 2000s, the Baustelle were singing’Footnote13 The reference to the 2000s and to a popular band brings Manzoni’s conceptual artwork into a semantic domain closer to Instagram users. In this way, it sparks a dialogue between the 1961 museum object and contemporaneity; at the same time, it makes the object available for resignification on behalf of the users. The fact that artworks are open for resignification is also remarked on in the second part of the caption, which continues: ‘Today, we are feeling a little romantic too … And we will spend this Saturday (re)discovering the art of the Short Century.’ Through the word (re)discovering, the museum’s interpretative work is compared to the meaning-making process of the band Baustelle and of the author of the repost’s picture – establishing in such a way a truly multivocal environment that can prompt personal meaning-making. In sum, through a repost and a multivocal interpretation of the artwork, the museum recognises the visitors’ authority in creating their own museum experience and developing personal meaning-making.

Discussion

This article evaluated to what extent and how museums with democratic aspirations can actually be considered democratic in their use of Instagram, following the surprising scarcity of empirical data on this heatedly debated issue. Our content analysis of 400 posts by 8 art museums in Europe and the US shows that, although the content of the pictures and videos often seems innovative at first sight, the modes in which museums communicate are not as inclusive, visitor-centred and participatory as one might expect. In other words, while the images strive to give a picture of participatory museum activities or visitor-centred experiences, Instagram’s infrastructure for participation, personalisation and inclusion is not yet fully utilised. The most common types of posts include the dissemination of digitised artworks complemented with a – however informative – authoritative, knowledge-telling attitude, and the advertising of upcoming exhibitions and events. When interaction by users is fostered, this only rarely happens in a meaningful and scaffolded way, providing space for multivocal responses. Finally, Instagram is only sporadically used as a platform for socio-political issues and self-reflection regarding past and present museum practices.

It is thus clear that, on Instagram, the high promises of social media as powerful tools to achieve museums’ democratic aspirations have not yet been fulfilled. A number of democratising practices is, however, starting to emerge. Three posts we deemed illustrative of these more democratic practices were analysed in the study. Instagram’s participatory potential is harnessed by posts fostering meaningful and multivocal interaction between the institution and internet users by means of instructional scaffolding. Museums can also intelligently use reposts, which acknowledge museum experiences as highly dependent on the visitor. Finally, posts addressing socio-political issues or self-reflection on past and present practices emerged as significant in contributing to a more inclusive use of Instagram.

Some limitations of our study can be met by doing further research. First, a content analysis of a more comparative and longitudinal nature might be conducted with a larger sample of (art) museums in more parts of the world and over a longer time period. Particularly, since the pandemic of Covid-19 and the following lockdowns, things have changed since we collected our data. If the virus accelerated the digitalization of museum practice, did these lockdowns also accelerate the process of the democratisation of museums on Instagram, and does this process continue once museums reopened to the public? Similar questions can be asked considering political activism, such as Black Lives Matter, which led several museums to join #BlackoutTuesday (posting a black square on 2 June 2020), albeit with diverging reactions.Footnote14 Second, considering that the length of Instagram captions demands a high degree of interpretation, a quantitative account could benefit from more factual codes that leave less room for interpretation. Alternatively, further studies could adopt qualitative rather than quantitative methods. Third, the results of this study could be cross-referenced with a study on users’ response: it is still to be determined whether Instagram users are actually willing to respond in meaningful ways to museum’s efforts for instructional scaffolding and opening a dialogue, and how museums in their turn respond to these reactions (cf. Gronemann, Kristiansen, and Drotner Citation2015). Moreover, it would be profitable to assess how to reach online groups who are often excluded. Finally, it might be useful to study the relation between the model of curation in the brick-and-mortar museum and the modes of communication adopted by the social media managers. Particularly smaller museums might lack sufficient staff and resources to invest significantly in their social media accounts, regardless of their democratic aspirations in the museums as a whole.

Nevertheless, we hope to have shed some light on the methods museums can apply to contribute to a more democratic use of Instagram and other social media. If museums want to remain true and profitable to its declared democratic intents, it is necessary to recognise that social media activities are democratising only if they are designed with this purpose (Russo Citation2012; Silberman and Purser Citation2012). The availability of more factual data regarding museums’ use of Instagram is likely to foster this transition. The aim of this article is, in fact, to provide institutions with both a conceptual framework and practical tools to assess their presence on social media and to devise strategies to effectively pursue their democratic aims.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Maaike van Leendert and Marlijn Metzlar for their valuable help as additional coders for the inter-coder reliability test.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Greta Bosello

Greta Bosello, MA has a Master's degree in Creative Industries from Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands. Now based in Milan, Italy, she works in the field of digital communication for arts and design. This article draws on her Master’s thesis #ArtToThePeople? Instagram, Art Museums and Democratising Practices (2019).

Marcel van den Haak

Dr. Marcel van den Haak is a cultural sociologist. At the time of this research, he worked as Assistant Professor of Cultural policies and Cultural education at the department of Modern Languages and Cultures of Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands. Currently, he is a lecturer at Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Notes

1 We performed our content analysis before the article by Jarreau et al. was published.

2 The time needed to publish 50 posts ranged from 29 days (Guggenheim) to 125 days (British Museum).

3 In rare cases when more than two communication modes seemed appropriate, the two codes were chosen that were deemed the most obvious.

4 For the posts’ subjects, Krippendorff’s alpha could be measured directly, resulting in an acceptable alpha of 0.75. Because each post could be attributed up to two modes of communication, the alpha of this variable could only be calculated separately for each code. Two of the most frequently occurring codes received proper alphas (advertising events: 0.78; knowledge-telling: 0.67), but the other codes did not (see Krippendorff Citation2013, 325). However, this is an often-occurring problem with codes with low frequencies (De Swert Citation2012).

5 This percentage is much higher than in science museums, where 19% of all posts depict objects (Jarreau, Dahmen, and Jones Citation2019).

6 In Danish museums in 2013, this type (framed as ‘stories’) was the most commonly used on Facebook (Gronemann et al. Citation2015). Agostino, Arnaboldi, and Lampis (Citation2020) show that this practice significantly increased during the Covid crisis in Italy.

7 Gribbon (Citation2021, 29–30) observes that posts that are explicit ‘calls to action’ are relatively rare, but do garner by far the most comments.

9 An example is Museo Guggenheim’s post published on 20 March 2019: https://www.instagram.com/p/BvPAOLoHY4u/

13 Translation by the authors (similar below).

14 See for instance https://www.instagram.com/p/CA6xVfqFMEU/ and https://www.instagram.com/p/CA7sJs3ncXh/

References

- Agostino, D., M. Arnaboldi, and A. Lampis. 2020. “Italian State Museums During the COVID-19 Crisis: From Onsite Closure to Online Openness.” Museum Management and Curatorship 35 (4): 362–372. doi:10.1080/09647775.2020.1790029.

- Amanatidis, D., I. Mylona, S. Mamalis, and I. Kamenidou. 2020. “Social Media for Cultural Communication: A Critical Investigation of Museums’ Instagram Practices.” Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing 6 (2): 38–44. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3836638.

- Arias, M. 2018. Instagram Trends: Visual Narratives of Embodied Experiences at the Museum of Islamic Art. MW18: MW 2018. https://mw18.mwconf.org/paper/instagram-trends-visual-narratives-of-embodied-experiences-at-the-museum-of-islamic-art/.

- Arnold, K. 2015. “From Caring to Creating: Curators Change Their Spot.” In Museum Practice: The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, edited by C. McCarthy, 317–340. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Badell, J.-I. 2015. “Museums and Social Media: Catalonia as a Case Study.” Museum Management and Curatorship 30, 244–263.

- Balloffet, P., F. Courvoisier, and J. Lagier. 2014. “From Museum to Amusement Park: The Opportunities and Risks of Edutainment.” International Journal of Art Management 16 (2): 4–19.

- Barret, J. 2011. Museums and the Public Sphere. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Bell, J., and J. Ippolito. 2015. “Diffused Museums: Networked, Augmented, and Self-Organized Collections.” In Museum Media. The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, edited by M. Henning, 473–499. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Black, G. 2015. “Developing Audience for the Twenty-First-Century Museum.” In Museum Practice: The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, edited by C. McCarthy, 123–152. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Booth, P., A. Ogundipe, and S. Røyseng. 2020. “Museum Leaders’ Perspectives on Social Media.” Museum Management and Curatorship 35, 373–391.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- British Museum. 2018. Review 2017-2018. London. https://www.britishmuseum.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/British_Museum_Annual_Review%202017_18.pdf.

- British Museum. 2019. About us. https://britishmuseum.org/about_us/management/about_us.aspx.

- Brown, K., and F. Mairesse. 2018. “The Definition of the Museum Through its Social Role.” Curator: The Museum Journal 61, 525–539.

- Budge, K., and A. Burness. 2018. “Museum Objects and Instagram: Agency and Communication in Digital Engagement.” Continuum 32 (2): 137–150. doi:10.1080/10304312.2017.1337079.

- Cotton Dana, J. 1920. A Plan for a New Museum: The Kind of Museum it Will Profit a City to Maintain. Woodstock, VT: The Elm Tree Press.

- Council of Europe. 2005. “Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society.” Council of Europe Treaty Series No. 199. https://rm.coe.int/1680083746.

- Davidson, L. 2015. “Visitor Studies: Towards a Culture of Reflective Practices and Critical Museology for the Visitor-Centred Museum.” In Museum Practice: The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, edited by C. McCarthy, 503–528. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- De Swert, K. 2012. Calculating Inter-Coder Reliability in Media Content Analysis Using Krippendorff's Alpha. Amsterdam: Center for Politics and Communication.

- Drotner, K., and K. Schrøder, eds. 2013. Museum Communication and Social Media: The Connected Museum. New York: Routledge.

- Fairclough, G. 2012. “Others: A Prologue.” In Heritage and Social Media. Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture, edited by E. Giaccardi, xiv–xvii. New York: Routledge.

- Falk, J. H., and L. D. Dierking. 2013. The Museum Experience Revisited. Walnu Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Fletcher, A., and M. Lee. 2012. “Current Social Media Uses and Evaluations in American Museums.” Museum Management and Curatorship 27 (5): 505–521. doi:10.1080/09647775.2012.738136.

- Gerrard, D., M. Sykora, and T. Jackson. 2017. “Social Media Analytics in Museums: Extracting Expressions of Inspiration.” Museum Management and Curatorship 32, 232–250.

- Giaccardi, E. 2012. Heritage and Social Media: Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge.

- Gribbon, E. 2021. “Museums in British Columbia During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Continuing to Engage the Public Online.” (BSc honors thesis). University of Victoria.

- Gronemann, S. T., E. Kristiansen, and K. Drotner. 2015. “Mediated Co-Construction of Museums and Audiences on Facebook.” Museum Management and Curatorship 30 (3): 174–190.

- Guggenheim Bilbao. 2018. Guggenheim Bilbao XX Anniversary: Art Changes everything. http://www.guggenheim-bilbao-corp.eus/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/MEMORIA-2017-EN.pdf.

- Guggenheim Bilbao. 2019. Mission, Vision and Value. Retrieved April 20, 2019, from http://www.guggenheim-bilbaocorp.eus/en/bilbao-guggenheim/mission-vision-values.

- Hagedorn-Saupe, M., L. Kampshulte, and A. Nouschka-Roos. 2013. “Informal, Participatory Learning with Interactive Exhibit Settings and Online Services.” In Museum Communication and Social Media. The Connected Museum, edited by K. Drotner, and K. C. Schrøder, 111–129. New York: Routledge.

- Henning, M. 2006. Museum, Media and Cultural Theory. New York: Open University Press.

- Higgins, P. 2015. “Total Media.” In Museum Media. The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, edited by M. Henning, 305–326. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Hooper-Greenhill, E. 1994. “Museum Education: Past, Present and Future.” In Towards the Museum of the Future, edited by R. Miles, and L. Zavala, 133–146. London: Routledge.

- Hudson, K. 1975. A Social History of Museums. What the Visitors Thought. London: The MacMillan Press.

- Hull, G., and J. Scott. 2013. “Curating and Creating Online: Identity, Authorship and Viewing in a Digital Age.” In Museum Communication and Social Media. The Connected Museum, edited by K. Drotner, and K. C. Schrøder, 130–151. New York: Routledge.

- ICOM. 1970. “Ethics of Acquisitions” Statement. ICOM. archives.icom.museum/acquisition.html#1.

- ICOM. 2017. Statutes. https://icom.museum/wpcontent/uploads/2018/07/2017_ICOM_Statutes_EN.pdf.

- ICOM. 2020. Museums, museum professionals and COVID-19: follow-up survey. https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FINAL-EN_Follow-up-survey.pdf.

- Iversen, O. S., and R. C. Smith. 2012. “Connecting to Everyday Practices: Experiences from the Digital Natives Exhibition.” In Heritage and Social Media. Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture, edited by E. Giaccardi, 216–144. New York: Routledge.

- Jarreau, P. B., N. S. Dahmen, and E. Jones. 2019. “Instagram and the Science Museum: A Missed Opportunity for Public Engagement.” Journal of Science Communication 18 (2): 1–22. doi:10.22323/2.18020206.

- Kelly, L. 2013. “The Connected Museum in the World of Social Media.” In Museum Communication and Social Media. The Connected Museum, edited by K. Drotner, and K. C. Schrøder, 54–74. New York: Routledge.

- Kidd, J. 2011. “Enacting Engagement Online: Framing Social Media use for the Museum.” Information, Technology and People 24 (1): 64–77.

- Krippendorff, K. 2013. Content Analysis. An Introduction To Its Methodology. London: Sage.

- Kunsthal Rotterdam. 2018. Annual Report 2017. http://jaarverslag.kunsthal.nl/?lang=en.

- Kunsthal Rotterdam. 2019. What We Do. https://www.kunsthal.nl/en/about-kunsthal/organisation/what-we-do/.

- Laestadius, L. 2016. “Instagram.” In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods, edited by A. Quan-Haase, and L. Sloan, 573–592. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Lotina, L. 2014. “Reviewing Museum Participation in Online Channels in Latvia.” Museum Management and Curatorship 29 (3): 280–292. doi:10.1080/09647775.2014.919167.

- Marselis, R., and L. M. Schutze. 2013. ““One Way to Holland”: Migrant Heritage and Social Media.” In Museum Communication and Social Media. The Connected Museum, edited by K. Drotner, and K. C. Schrøder, 75–92. New York: Routledge.

- Marstine, J., J. Dodd, and C. Jones. 2015. “Reconceptualizing Museum Ethics for the Twenty-First Century: A View from the Field.” In Museum Practice: The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, edited by C. McCarthy, 69–96. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- McMillen, R., and F. Alter. 2017. “Social Media, Social Inclusion, and Museum Disability Access.” Museums and Social Issues 12 (2): 115–125. doi:10.1080/15596893.2017.1361689.

- McNely, B. J. 2012. “Shaping Organizational Image-Power Through Images: Case Histories of Instagram.” Professional communication conference (IPCC) (pp. 1–8).

- Meecham, P. 2013. “Social Work. Museums, Technology, and Material Culture.” In Museum Communication and Social Media. The Connected Museum, edited by K. Drotner, and K. C. Schrøder, 33–53. New York: Routledge.

- MoMA The Museum of Modern Art. 2018. Year in Review 2016-17. https://www.moma.org/interactives/annualreportFY17/.

- MoMA The Museum of Modern Art. 2019. Mission Statement. www.moma.org/about/who-we-are/moma.

- Museo del Novecento. 2018. Inforeport 2017. https://www.museodelnovecento.org/images/inforeport/Museo900_Report2017-2.pdf.

- Museo del Novecento. 2019. The Museum. Retrieved April 20, 2019. http://www.museodelnovecento.org/en/museum2%3E.

- MuseWeb. About. Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.museweb.net/welcome-to-museumsandtheweb-com/.

- Ou, J. 2020. “China Science and Technology Museum Boosting Fight Against COVID-19.” Museum Management and Curatorship 35, 227–232.

- Panzarin, F. 2018, March 16. Fondazione Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, un modello unico di #arttothepeople. Il Giornale delle Fondazioni. http://www.ilgiornaledellefondazioni.com/content/fondazione-pirelli-hangar-bicocca-un-modello-unico-di-arttothepeople.

- Parry, R. 2013. “The Trusted Artifice: Reconnective with the Museum’s Fictive Tradition Online.” In Museum Communication and Social Media. The Connected Museum, edited by K. Drotner, and K. C. Schrøder, 17–32. New York: Routledge.

- Pine, J., and J. Gilmore. 1998. “Welcome to the Experience Economy.” Harvard Business Review 76 (4): 97–107.

- Pioneer Works. 2018. Sciences at Pioneer Works. http://www.sciencepartnershipfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/science_proposal_2017.pdf.

- Pioneer Works. About. Accessed April 20, 2019. http://pioneerworks.org/about/.

- Pirelli Hangar Bicocca. 2019. About Us. www.hangarbicocca.org/en/pirelli-hangarbicocca/#.

- Potts, T. 2020. “The J. Paul Getty Museum During the Coronavirus Crisis.” Museum Management and Curatorship 35, 217–220.

- Rao, S. 2017. “Interstitial Spaces: Social Media As A Tool For Community Engagement.” MW2017: museums and the Web 2017. https://mw17.mwconf.org/proposal/interstitial-spaces-social-media-as-a-tool-for-community-engagement/.

- Reeve, J., and V. Woollard. 2015. “Learning, Education, and Public Program in Museums and Gallery.” In Museum Practice. International Handbooks of Museum Studies, edited by C. McCarthy, 551–576. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Rijksmuseum. 2018. Jaarverslagen 2017. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/organisatie/jaarverslagen.

- Rijksmuseum. 2019. Vision and Mission of the Rijksmuseum. www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/organisation/vision-and-mission.

- Ruggiero, P., R. Lombardi, and S. Russo. 2021. “Museum Anchors and Social Media: Possible Nexus and Future Development.” Current Issues in Tourism, 1–18. doi:10.1080/13683500.2021.1932768.

- Russo, A. 2012. “The Rise of the “Media Museum”: Creating Interactive Cultural Experiences Through Social Media.” In Heritage and Social Media. Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture, edited by E. Giaccardi, 145–158. New York: Routledge.

- Samaroudi, M., K. Rodriguez Echavarria, and L. Perry. 2020. “Heritage in Lockdown: Digital Provision of Memory Institutions in the UK and US of America During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Museum Management and Curatorship 35, 337–361.

- Sandell, R. 2007. Museum, Prejudice and Reframing the Difference. London: Routledge.

- Scott, K. 2017. “#TeensCan: Let Teens Be Your Social Media Voice.” MW17: MW 2017. https://mw17.mwconf.org/paper/teenscan-let-teens-be-your-social-media-voice/.

- Silberman, N., and M. Purser. 2012. “Collective Memory as Affirmation. People-Centred Cultural Heritage in a Digital Era.” In Heritage and Social Media. Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture, edited by E. Giaccardi, 13–29. New York: Routledge.

- Simon, N. (2010). The Participatory Museum. Museum 2.0.

- Smith, J. 2015. “The Me/Us/Them Model: Prioritizing Museum Social-Media Efforts for Maximum Reach.” MW2015: museums and the Web 2015. https://mw18.mwconf.org/paper/instagram-trends-visual-narratives-of-embodied-experiences-at-the-museum-of-islamic-art/.

- Stuedahl, D., and O. Smørdal. 2015. “Matters of Becoming, Experimental Zones for Making Museums Public with Social Media.” International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts 11 (3–4): 193–207.

- Suh, J. 2020. “Revenue Sources Matter to Nonprofit Communication? An Examination of Museum Communication and Social Media Engagement.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 1–20. doi:10.1080/10495142.2020.1865231.

- Suzić, B., V. Stříteský, and M. Karlíček. 2016. “Social Media Engagement of Berlin and Prague Museums.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 46, 73–87.

- United Nations. Democracy. Accessed August 20, 2020. https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/democracy/.

- Vergo, P. 1989. “The Reticent Object.” In The New Museology, edited by P. Vergo, 41–60. London: Reaktion Books.

- Weilenmann, A., T. Hillman, and B. Jungselius. 2013. “Instagram at the Museum: Communicating the Museum Experience Through Social Photo Sharing.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1843–1852. Paris: ACM Press. doi:10.1145/2470654.2466243.

- Wellington, S., and G. Oliver. 2015. “Reviewing the Digital Heritage Landscape: The Intersection of Digital Media and Museum Practice.” In Museum Practice: The International Handbooks of Museum Studies, edited by C. McCarthy, 577–198. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wong, A. 2011. “Ethical Issues of Social Media in Museums: A Case Study.” Museum Management and Curatorship 26 (11): 97–112.