ABSTRACT

Although the involvement of botanic gardens in the colonial expansion of the British Empire is well documented, the public communication of this part of the history of the gardens is not as visible as it has increasingly become in many ethnographic museums, where the topic has been dealt with more actively within recent years. In this article, presenting findings from ethnographic fieldwork conducted in the botanic gardens of Oxford and Kew in 2022 and 2023,Footnote1 I show how colonial-era scientific practices are still used in the namegiving of plants, although scientists within the field have become increasingly aware of the importance of recognising Indigenous people and places.Footnote2 Through an analysis of the wording applied in signs and guided tours, I furthermore demonstrate how the colonial legacies of the plant collections of the two gardens are only superficially communicated to their visitors, despite numerous initiatives taking place behind the scenes.Footnote3

Introduction

The Botanic Garden at the University of Oxford is the oldest of its kind in the United Kingdom. Since 1621, it has been located along the banks of the Cherwell River, across the road from Magdalen College. Like the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, founded in 1759, the Botanic Garden in Oxford thus predates the time during which the British Empire was the largest the world has ever seen.Footnote4 Despite their age, and the fact that the colonial era significantly transformed the ‘specific organisational forms and roles’ of both gardens (Barber Citation2016, 660), their imperial legacies are not made immediately visible to their visitors. However, as this article will demonstrate, both gardens not only have deep roots in colonialism, they also to some extend reproduce colonial-era worldviews in their written and oral communication, by celebrating ‘discoveries’ made by European botanists, plant scientists and colonial ‘explorers’, who still to this day are often admirably described as people who ‘help[ed] discover and introduce exotic plants from many parts of the world’ (Jackson and Sutherland Citation2013, 508). By questioning the use of words like ‘discoveries’ in situations where plants were most likely already known and used by Indigenous communities, the article contributes to the literature on botanic gardens with a critical approach to the many writings celebrating European naturalists and plant scientists as ‘explorers’ ‘discovering’ the world.

While publications uncovering the colonial legacies of botanic gardens, and their associated ‘plant hunters’ collecting plants in the service of the British Empire, are nothing new (Barber Citation2016; Brockway Citation1979; Cornish Citation2015; Cornish, Driver, and Nesbitt Citation2021; Frost Citation1996; Grove Citation1995; Harris Citation2015; Citation2017a; Citation2017b; Citation2021; Hoogte and Pieters Citation2014; Jackson Citation2009; Mackay Citation1996; Naumann Citation2006; Nesbitt and Cornish Citation2016; Parker and Ross-Jones Citation2013; Schiebinger Citation2009; Smith and Figueiredo Citation2022; Voeks and Greene Citation2018), this article is unique in providing a fieldwork-based analysis of how these colonial legacies are communicated to visitors of the botanic gardens in Oxford and Kew. By demonstrating how colonial legacies of plant collections in two of the most prominent and influential botanic gardens in the United Kingdom are dealt with, the examples presented in this article will shed light on an area of museum studies that has so far not been researched as thoroughly as other parts of the museum world. The article thus contributes to the field of museum studies with an analysis of a part of the museum sector, which generally speaking tends to focus more on loss of biodiversity than on the impact of colonialism. However, as I will argue, communicating the consequences of colonial exploitation need not stand in contrast with the important initiatives made by botanic gardens to widen public understandings of the impacts of climate change.

Building on and expanding previous ethnographic fieldwork conducted in ethnographic museums and art galleries in the United Kingdom (Nielsen Citation2022c) and South Africa (Nielsen Citation2019; Citation2021; Citation2022b; Citation2023), the examples presented in this article highlights that unlike ethnographic museums such as the Pitt Rivers, where curators in recent years have worked actively towards highlighting the colonial legacies of the collection to their visitors,Footnote5 the text panels of the botanic gardens in Oxford and Kew do not contain the same level of critical self-reflexion regarding the origin and historical significance of their collections. Although the involvement of botanic gardens in the colonial expansion of the British Empire is undeniable (Barber Citation2016; Brockway Citation1979; Schiebinger Citation2009), a decolonial, critical approach did not come through on the guided tours that I participated in as part of my fieldwork within and around the gardens, nor in the text panels communicating the cultural history of their plants to the public.

The participant observations and interviews forming the basis of this article, has been conducted as part of a largerscale research project on decolonial curatorial practices in the United Kingdom and France, in which I demonstrate that although initiatives towards greater inclusion of Indigenous perspectives are being made, the colonial legacies of museum collections remain a difficult and continuous presence (Nielsen Citation2022c). This is perhaps even more evident in botanic gardens than in ethnographic museums, where initiatives to confront and discuss colonial legacies have become more visible in recent years (Ariese and Wróblewska Citation2021; Nielsen Citation2022b; Janes and Sandell Citation2019). Although the researchers and plant scientists, whom I met behind the scenes, are well aware of the complex histories of their collections, visitors walking through the botanic gardens of Oxford and Kew, like I did, would in most cases not be confronted with the colonial roots of the plants on display. Meta-level stories about how the plants ended up in what was once two of the key financial and scientific centres of the British Empire, and why they, or the seeds from which they originate, were brought to the shores of England, are not immediately present. Nor is the local knowledge from Indigenous peoples, which in many cases was lost in the process of systematising the flora and fauna of the world into one, European-founded, Latin system.

Through an analysis of how the cultural history of the plants in two of the oldest and most trendsetting botanic gardens in the United Kingdom is communicated to the visiting public, I seek to highlight that it is not only the collections of ethnographic or cultural historical museums, which have deep roots in colonial-era collection practices. So too have the biological parts of the museum world – the ones, which are found growing in botanic gardens. Here, the worldviews of colonial times are also evident: partly through namegiving traditions and classification methods of species ‘new’ to science, but also with regard to the lack of visibility of local knowledge from Indigenous populations, which in many cases were lost or simply undocumented, at the time of collection.

Similarly to the thousands of objects that were acquired – or stolen – by military officers, missionaries, anthropologists and others outposted by the former colonial powers of Europe, and later were presented in European museums in settings designed to portray Indigenous and non-European peoples as less developed on the ladder of evolution (Bayley Citation1860, 5; BM Citation1899, 98; Tricoire Citation2017, 33),Footnote6 the colonial collection and organisation of plants brought with it a uniformity of thought that rarely acknowledged Indigenous or locally produced knowledge. The loss of invaluable expertise about the effect and uses of objects and plants has left present-day curators with few clues to retrace the original meaning and histories around their collections: How does one deal with a museum object (biological, ethnographic or otherwise) whose only recorded information remaining from the time of collecting is the name of the collector and the moment this person acquired it?

These and other complex questions caused by a museum system developed at a time, when the classification and dissemination of objects justified European colonial expansion, are challenging museum professionals around the world. At a time, where recent demands for decolonisation, within and from outside museum institutions, are increasingly pushing for a rethinking of collections and the ways they are communicated to the public, these questions have become even more poignant.Footnote7 Discussions about how – and not least where – stories about objects collected by European museums during colonial times are best conveyed are at the forefront of many a debate within the museum world. Especially within ethnographic museums, where the repatriation or return of objects is a topic full of political tension.Footnote8 But what about botanic gardens? Although discussions about repatriation of plants are mostly had in relation to access to digitalised archives and herbaria,Footnote9 classifications of collections in botanic gardens are also a result of the time and context in which the objects or – in this case – plants were collected. The ways in which collections of any kind are prestended to the public reveals a great deal about the underlying structures of society, which often unnoticed determines how an object or plant is described. Or – as Kew itself puts it in its History, Equity and Inclusion Action Plan from 2022 – ‘What RBG Kew chooses to say, or not say, reflects what it is as an institution today’.Footnote10

Collecting in the service of the British Empire

The volunteer guide leading the tour of Kew Gardens that I attended in April 2022 enthusiastically opened her arms as she welcomed the group of visitors that I was part of to the south wing of the impressive Temperate House: ‘Welcome to Africa’ she said, explaining that here, visitors can experience examples of plants from the temperate zones of the African continent – primarily from South Africa, which is home to over 24,000 species, half of which are endemic. Further on, the tour guide took us past plant compositions from other parts of the world, spread over five continents and sixteen islands ( and ). Section after section, we passed through small pieces of representations of the temperate parts of the planet: Africa, Australia, New Zealand, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific Islands. All gathered under one roof, in what Kew Gardens itself refers to as its ‘glittering cathedral’.Footnote11

From 1862 onwards, the Temperate House, which still today is considered the largest greenhouse in the world,Footnote12 made it possible to display plants from distant temperate regions that could survive and be experienced by visitors all year round in the otherwise not so temperate English climate. The construction of the Temperate House complemented the Victorian Palm House, which in 1848 had combined ‘the latest in glass and iron manufacturing techniques to construct a building of unprecedented lightness and grace’ (Teltscher Citation2020, 4). Together, the two greenhouses provided a unique opportunity for British visitors to the garden, to experience unusual plants, collected from tropical and temperate regions around the world, without ever having to venture further away than the outskirts of London:

Without even boarding a ship, the public could experience the damp heat and lush vegetation of the colonies. In recreating the tropics on the banks of the Thames, the Palm House declared technology’s victory over nature. (Teltscher Citation2020, 4)

Figure 1 and 2. The Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew’s Palm House from 1848, with labels showing the origin of the plants within. Source: Photos taken by the author during fieldwork in London in May 2022.

Although its website clearly describes the parts of Kew Gardens’ history during which plants, seeds and seedlings were required and redistributed in the service of the British Empire,Footnote14 the many stories about how central Kew and its collectors and botanists became in the global exchange of plants (Nielsen Citation2022a; Frost Citation1996, 75; Grove Citation1995, 414; Jackson Citation2009; Parker and Ross-Jones Citation2013, 34; Voeks and Greene Citation2018, 556), were not part of the guided tour that I participated in as part of my fieldwork. The enthusiastic welcome our volunteer guide gave during the tour of the Temperate House’s miniature version of Africa was instead served with a certain dose of pride about the vastness of the unique collection held by the botanic gardens. Impressive indeed, but why exactly does the botanic gardens in Kew hold such a rich collection? This is clearly linked to London's past as the capital of the British Empire – a connection that could have been highlighted to a greater extent, both in this specific guided tour, but, as I will illustrate below, also in the written communication in Kew, where the celebration of European ‘discoverers’ of plants remain part of the narrative communicated to visitors.

What’s in a name? Namegiving of plants then and now

As Gideon F. Smith and Estrela Figueiredo (Citation2022, 2) have argued,

[p]lants collected in the colonised countries were almost invariably described in books, journals and other publications that were published by the colonizers, in the colonising (mostly European) countries, in languages – including (botanical) Latin – that were often foreign to the citizens of the countries (then colonies) from which the plants originated.

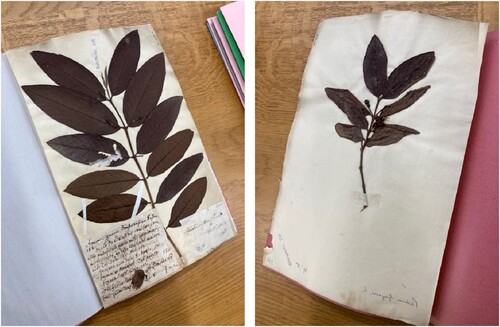

Figure 3 and 4. Examples of plants from the University of Oxford’s Herbarium: the specimen on the left is accompanied by a thorough handwritten description noted down at the time of collection, while the specimen on the right has virtually no information about the plant’s habitat, the circumstances under which it was collected or the plant’s original use and history. Source: Photos taken by the author during fieldwork at the University of Oxford’s Department of Plant Science in May 2022.

In addition, many species were named after people who are closely associated with colonial exploitation. Among these are the British imperialist Cecil John Rhodes (1853–1902), who dreamt of a British Empire stretching from Cape to Cairo,Footnote15 and firmly believed that the world would be a better place if more people were subject to British imperial control.Footnote16 From 1899 to 1976 as many as 126 plant species were named in his honour (Smith and Figueiredo Citation2022, 2). It was, in other words, not only the botanic collectors, sent out by European colonial powers, who functioned as what David Mackay (Citation1996) has called Agents of Empire. The names that botanists and plant scientists gave to the species they ‘discovered’ can similarly be considered ‘tools of empire’ (Schiebinger Citation2009, 11).

In the article ‘If “Rhodes”- must fall, who shall fall next?’ Sergei L. Mosyakin (Citation2022) has highlighted the challenges involved in changing existing names in the International Code of Nomenclature of Plants, Algae, and Fungi. Instead, he argues that botanists and plant scientists in the future should follow ‘a universal recommendation […] recommending authors to create a name in a way that would not hurt (or even potentially hurt) the feelings, beliefs, or prejudices […] of any real or even imaginable group of people’ (Mosyakin Citation2022, 253). Stephen Harris (Citation2015, 9), who is curator of the Oxford University Herbaria and author of a long list of publications about the history of the University of Oxford’s Botanic Garden,Footnote17 similarly agrees that it is important to keep the existing standardised binomial names in the International Code of Nomenclature. When I met him at his office in the University of Oxford’s Department of Plant Sciences, during my fieldwork in Oxford in May 2022, he argued that a consequence of changing the already given Latin names of plants, would most likely be several different naming systems that researchers would have to navigate.

Like Mosyakin (Citation2022), Harris would prefer making people aware of the origin and histories of the names and broaden the knowledge about the collection methods and namegiving traditions that through history have ignored and undermined Indigenous knowledge about the effects and uses of plants. Through his research, Harris has experienced an increase in recent years, in taking Indigenous places, peoples and individuals into account in the namegiving of new or re-found species. In time, he believes that this focus will contribute to a diversification of the internationally recognised namegiving system once established by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778).

But even if curators, botanists and other natural scientists in Kew and Oxford’s botanic gardens decide to keep the Latin names of their plant collections, the existing dissemination of the plants and their cultural historical origins could be improved, if the original meanings, effects and uses of the plants were taken more seriously into account in text panels, signs and guided tours. The botanists and curators, whom I spoke with during my fieldwork, are aware of this side of the history of plants and are regularly adding signs aimed at expanding the visitors’ attention to the multifaceted history of the plants in their collections. However, as the following example illustrates, the namegiving of suposedly ‘new-found’ species are still influenced by colonial-era celebrations of European ‘discoverers’ and so is the dissemination of these plants, when presented to the public.

The guided tour around Kew Gardens that I attended in April 2022 ended with a plant presented as a bit of a sensation: the Wollemi Pine Tree (Wollemia nobilis) from the temperate rainforest area of The Wollemi National Park in New South Wales in southeastern Australia. It is estimated that less than a hundred examples of the tree exist in the wild, although it is now common in public gardens around the United Kingdom.Footnote18 With a certain element of pride in being able to show a living example of this critically endangered tree at Kew, the tour guide enthusiastically told the story behind the unique ‘find’, which is also described on the sign planted in front of the tree ():

In 1994, David Noble stumbled upon something that would shock the scientific community. He found a grove of trees growing deep within a gorge, in a remote part of the Wollemi National Park, Australia. As a field officer, he expected to know the trees he came across, but he had never seen anything like these before. With the help of botanists, the tree was identified. It belongs to an ancient family of trees thought to have died out millions of years ago. Noble had found a living fossil.

Figure 5. The sign in Kew Gardens describing the legendary ‘find’ of the Wollemi Pine Tree by the Australian canyoner and botanist David Nobles in the Wollemi National Park in New South Wales. Source: Photo taken by the author during fieldwork in Kew Gardens in April 2022.

The Wollemi National Park is the home of up to 6,000-year-old cave paintings, made by Indigenous peoples, testifying to their long presence in the area (Taçon et al. Citation2006, 235). Their historical knowledge of the tree may not necessarily be possible to prove, but their presence in the area that was later given English names by British colonialists, who colonised the land they had ‘discovered’ and triumphantly brought home botanical and cultural-historical treasures from the area should perhaps be recognised in situations like these. Especially, in the context of a descriptive sign in Kew Gardens, which holdings of one of the ‘largest and most diverse’ plant collections in the world,Footnote19 is a direct result of British imperialism. As Peter Naumann (Citation2006, 78) points out in relation to the events following the 1994 ‘discovery’ of the Wollemi pine, the very

act of ‘discovering’ relates to the idea of revealing something, to make known what was unknown before […] It does, however, seem likely that if white Australians stumbled over the tree within two hundred years of the beginning of their occupation of the continent (and much more recent use of the area in which the tree was found), then Indigenous Australians, in their 40,000-50,000 year occupancy of the continent, and 4,000-5,000 year history of use of the area, may have also known of it.

What have plants ever done for us?

In the University of Oxford’'s Botanic Garden, the written dissemination of a selection of recognisable plants in the collection has in recent years been supplemented by cultural-historical text panels, based on Steven Harris’ book What have plants ever done for us? from 2015. The text panels communicate information about plant-based products that most people are familiar with in their everyday lives, but do not necessarily associate with the plants they come from. Through the text panels, visitors can now closely study what the plants that bear the fruits of the coffee bush or cocoa tree and the leaves of the tobacco plant look like, and in addition get information about the cultural-historical origins of the plants.

Although the cultural history of many plants are closely associated with Britain’s past as a world-spanning colonial empire, this is only superficially acknowledged in the cultural-historical text panels in the Botanic Garden in Oxford. An example of the lack of attention to this part of history is the sign by the entrance to the Glasshouse Collections that presents the story of how seeds and plant specimens, which ended up contributing to the financial success of the British Empire, were transported back to Britain. Under the headline Plants that changed the world and how they were moved, illustrations from the British linen producer John Ellis’ (1710–1776) Directions for bringing over seeds and plants, from the East-Indies and other distant countries in a state of vegetation from 1771 are depicted. Below these, the story about how an unspecified ‘we’ invented baskets, boxes and barrels to protect seeds and seedlings from their ‘ardous journeys across continents’. These transportation solutions were, however, not very efficient, so it was not until the 1820s, with the invention of the Wardian Case, a transportable miniature greenhouse, that ‘the efficient transport of plants across the planet’ became possible. Further down, the text informs visitors to the garden that, when first the unspecified ‘we’ understood the needs of the plants, it became possible to control the temperture, light, water and nutrition. In conclusion it is mentioned that:

By the mid-Victorian period, conservatories, where tender evergreens retreated for the winter, were joined by sophisticated palaces of iron and glass where plants from across the globe could be grown and displayed at their best.

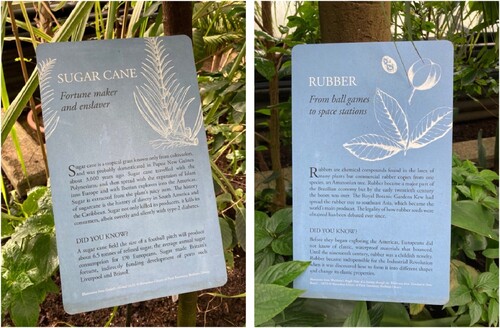

Another example of what I in this article have chosen to call the colonial roots of botany, is the sign conveying the cultural history of sugar cane: under the headline Fortune maker and enslaver, visitors are presented with the history of the tropical grass known as sugar cane, which was ‘probably domesticated in Papua New Guinea about 3,000 years ago [and later] travelled with the Polynesians, and […] spread with the expansion of Islam into Europe and with Iberian Explorers into the Americas’ (). The text acknowledges that the ‘history of sugarcane is the history of slavery in South America and the Caribbean’ and that sugar not only ‘killed its producers [but also] its consumers, albeit sweetly and silently with type-2 diabetes’. The sign concludes with the statement: ‘Sugar made Britain’s fortune, indirectly funding development of ports such as Liverpool and Bristol’. However, the text panel does not mention how the trade in sugar was not only closely associated with, but directly dependent on, the trade of the British Empire with enslaved people in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Figure 6 and 7. Text panels in the University of Oxford’s Botanic Garden with cultural historical information about the sugar cane (left) and the rubber tree (right). Sourc: Photos taken by the author in March 2022.

The wording ‘killed its producers’ is a rather unvarying description of the inhuman conditions under which the millions of people, who lost their lives producing sugar for the European colonial powers in the Caribbean, were exposed. Caribbean sugar production did indeed establish ‘Britain’s fortune’ but did so based on the gross exploitation and inhuman treatment of the people, who were transported across the Atlantic on slave ships financed by the British Empire and other European colonial powers, sold as slaves and forced to work in sugar plantations. Squeezing this essential part of history into the same sentence as a statement about the fact that the consumption of sugar causes deadly lifestyle diseases such as type-2 diabetes, testifies to the botanic garden’s rather superficial treatment of Britain’s colonial past and its present-day legacies.

Similarly, the sign presenting the cultural history of the rubber tree could have included information about the fatal working conditions of the colonial era in connection with the rubber production in the Amazon, Belgian Congo and the British colonies in Southeast Asia (Harris Citation2015, 207). Instead, it is only briefly mentioned that the ‘Royal Botanic Gardens [of] Kew had spread the rubber tree to southeast Asia, which became the world’s main producer’ and that the ‘legality of how rubber seeds were obtained has been debated ever since’ (). Where is the information on how central a role British botanic gardens played in the collection and redistribution of seeds and plants in the service of the British Empire? These stories are well documented (Brockway Citation1979, 459; Cornish Citation2015; Harris Citation2015, 205–207; Parker and Ross-Jones Citation2013, 34), but are only superficially presented, if at all, to visitors of the Botanic Garden in Oxford. The description of rubber as ‘a childish novelty’ before it was used as an industrial component in Europe and North America in the nineteenth century, furthermore undermines the qualities that the Indigenous population of South America undoubtedly associated with the tree during the more than 2,500 years it was used before the first Europeans became aware of it in the seventeenth century (Harris Citation2015, 205).

It is thought-provoking that the cultural-historical dissemination of plants in the University of Oxford’s Botanic Garden does not, to the same extent as the dissemination of objects in other museum collections in the University’s Gardens, Libraries and Museums network, take into account the human consequences of colonial collections. The collection, naming and redistribution of – in this case – seeds and plants initiated by the botanic gardens of Oxford and Kew, in direct extension of the colonial power apparatus, is not significantly different from the collection of the artworks and cultural artefacts that were aquired by officers, missionaries, anthropologists and other emissaries of Europe’s (former) colonial powers and subsequently exhibited in museums around Europe, based on a notion that other peoples’ material cultural heritage could exhibit Europeans as more ‘developed’ and ‘civilised’ than others.

The difference is perhaps simply that the decolonial discourses that in recent years have gained more ground in museums with art and cultural-historical or ethnographic objects have not gained the same degree of popularity among curators and botanical researchers who manage the public dissemination of botanic gardens. Presumably, based on a notion that visitors to botanic gardens are not as interested as visitors to art and cultural history museums in this part of history, but prefer a potentially less conflict-filled history, evolving around the medicinal and nutritional properties, as well as the aesthetic qualities of plants. As Lucile E. Brockway (Citation1979, 461) has expressed it, ‘[b]otanic gardens are generally seen by the public as beautiful green enclaves with rare trees and flowers, with a laboratory where botanists pursue the mysteries of plant cytology, or nowadays, the ecology of the biosphere’. Like other museum institutions, however, botanic gardens are also products of the changing times of which they are part. They are not neutral institutions, but (among other things) results of colonial-era exploitation and collection methods, which in many cases did not prioritise Indigenous knowledge about the uses and histories of plants that were often collected in order to support the British Empire financially.Footnote20

Brockway (Citation1979, 461) has described how botanic gardens through ‘the exercise of sheer power as well as by their scientific expertise […] increased the comparative advantage of the Western core of nations over the rest of the world [with] systemic results that we still wrestle with today’. In the years that have passed since Brockway wrote her analysis of the colonial legacies of Britain’s botanic gardens more than forty years ago, museums have increasingly become more aware of the importance of making this legacy visible to their visitors. However, as this article shows, the botanic gardens in Oxford and Kew still have work to do in order to secure that their visitors are not simply invited to enjoy a leisurely ‘walk in the park’ but are in addition presented with the complex colonial legacies of the plants in their collections. In a country ‘anecdotally renowned as a nation of garden lovers’ (Connell Citation2004, 229), a more thorough examination of the strong links between plants and colonialism would undoubtedly add another layer of complexity to the visitor experience, which might not necessarily be considered part of a ‘pleasant day out’ (Connell Citation2004, 234), but is nevertheless important to recognise. Since much Indigenous knowledge is associated with respect for nature and local environments, the inclusion of perspectives ‘new to science’ need not be in contrast to the important work put in by plant scientists and curators in botanic garden to secure public awareness about loss of biodiversity and climate change. On the contrary, the stories linked to the colonial legacies of plant collections, could add new aspects with added layers to the communication already taking place.

Conclusion

Plants are much more than their aesthetic appearance, their medicinal and nourishing properties. Like objects held by ethnographic and art historical museums, the collections held by botanic gardens are the result of centuries of human influence that have changed them and their original habitats to such an extent that many of them can be considered at least as curated as other kinds of museum objects. As this article demonstrates, a significant part of the human impact of plants is associated with Europe’s colonial conquests from the end of the sixteenth century onwards. European colonisation brought with it changes that had far-reaching consequences – not only for the world’s natural resources and the exploitation of them, but also for the people who lived among and of them. Species were displaced, cultivated and propagated and nature was put into system by colonial-era botanists, natural scientists and collectors, who gave them names according to the system invented by Linnaeus that is still in use. Species that were new to visiting Europeans were given new Latin names and were also often named after the European botanist who had alledgedly ‘discovered’ them, rather than the people who already lived among them and used them in their everyday lives. As shown in the example of the pine tree Wollemia nobilis, named after the English-born Australian David Noble, this practice is still ongoing, despite an increased focus among plant scientists on taking Indigenous sites, populations, and individuals more into account and – to a much greater extent than previously – honouring them in the naming of ‘newly found’ or perhaps rather re-found species.

As my observations in the Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew and the University of Oxford’s Botanic Garden illustrate, the dissemination of this part of the cultural history of plants is only superficially presented to visitors of the gardens. A greater focus on this part of the cultural history of plants would emphasise how substantial the legacies of the colonial era still are and how widespread the consequences of empire remain: the way the world is organised today is very much a result of past thoughtpatterns and colonial perceptions of the world. As museums and other cultural institutions increasingly engage in public discussions with a new level of self-criticism, the public communication of botanic gardens could similarly benefit from a thorough examination of the wording applied in labels and guided tours. As I have shown, further efforts could be made to ensure that the written and oral communication of the two botanic gardens does not unilaterally perpetuate colonial-era worldviews that present ‘discoveries’ of ‘new found’ species with a level of pride that at best reflects inattention, at worst exclusive Eurocentrism, which uncritically continues to celebrate London and Oxofrd as the world’s obvious epicentres.

Acknowledgements

I am sincerely grateful for the opportunity that the Carlsberg Foundation has given me through its generous financial support of my postdoctoral research of decolonial curatorial practices in the United Kingdom and France, which has enabled me to conduct the fieldwork behind this article. I thank Professor Stephen A. Harris from the Department of Biology at the University of Oxford, who kindly took the time to answer my many questions about namegiving practices of plant species and showed me around the University of Oxford Herbarium in May 2022, as well as Dr Sarah Edwards, who took the time to meet with me in the Botanic Garden in Oxford in July 2023. I would like to thank Dr Chris Thorogood for pointing me in the right direction, Dr Mark Nesbitt and Dr Nick Leimu-Brown for our interesting conversations about the colonial roots and contemporary dilemmas of botanical practices, Dr Ashley Coutu for her invaluable comments and suggestions during my final stages of writing, as well as Dr Trine Hass and Dr Fergus Cooper for inspiring tours around the botanic gardens of Oxford and Kew. My sincere thanks also go to the guides and volunteers who facilitated the botanic garden tours that I took part in during my fieldwork – in order to protect their anonymity, I have chosen not to list their individual names. Finally, I owe a huge thank you to the Pitt Rivers Museum, Linacre College, the San Cataldo monastery as well as the Landmark Trust for their generous hospitality and moral support during the writing of this article, as well as the editors of the Museum Management and Curatorship journal and the anonymous peer-reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Vibe Nielsen

Dr Vibe Nielsen is affiliated with the Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford and holds a Carlsberg Foundation Junior Research Fellowship at Linacre College. Her research focuses on processes of decolonisation and changing curatorial practices in the United Kingdom and France. She defended her PhD thesis Demanding Recognition: Curatorial Challenges in the Exhibition of Art from South Africa at the Department of Anthropology at the University of Copenhagen in 2019 and has published her research in the Routledge-anthology Global Art in Local Art Worlds – Changing Hierarchies of Value (2023), the Ethnic and Racial Studies Journal article ‘In the Absence of Rhodes: decolonizing South African universities’ (2021) and most recently in the Fayard-anthology Dé-Commémoration : Quand le monde déboulonne des statues et renomme des rues (2023).

Notes

1 The fieldwork conducted for this article has taken place as part of a largerscale research project supported by the Carlsberg Foundation (CF20-0141), demonstrating how museums in the United Kingdom and France attempt to change and challenge their curatorial practices in light of recent calls for decolonisation, expressed by movements such as Black Lives Matter and Rhodes Must Fall.

2 An earlier version of this article, presenting preliminary findings from the parts of my fieldwork conducted in the first half of 2022, was published in Danish by the cultural historical journal Kulturstudier in their special issue on the cultural history of plants (Nielsen Citation2022a).

3 Among these, the Miscellaneous Reports Project, which enables access through cataloguing and conservation to the Miscellaneous Reports Collection, can be mentioned. As Kew mentions on its website, the collection is ‘an essential resource for exploring the central role of Kew in the colonial and global networks of economic botany and scientific activity [from] 1850-1928’ (http://web.archive.org/web/20210302105408/https://www.kew.org/science/our-science/projects/miscellaneous-reports). In 2021, the project hosted a three-day online conference called Botany, Trade and Empire: Exploring Kew’s Miscellaneous Reports Collection, which examined the collection as ‘a crucial source of evidence for critically examining and confronting Kew’s own history and colonial role’ (http://web.archive.org/web/20210307062042/https:/www.kew.org/science/engage/get-involved/conferences/botany-trade-empire) [Accessed 18 August 2023].

4 During its first years, Oxford Botanic Garden functioned as a physic garden that enabled students of the University of Oxford as well as their teachers to engage with living examples of the plants they studied (Harris Citation2017a, 5–8; Thorogood and Hiscock Citation2019, 9).

5 In the article “‘What’s in a name?’ Gentænkning af genstandstekster på Pitt Rivers Museum” (Nielsen Citation2022c) in the special edition of Jordens Folk about ethnographic museums, I examine, in conversation with research associate at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Marenka Thompson-Odlum, how curators at the University of Oxford’s leading ethnographic museum rethink object labels through the Labelling Matters project.

6 As I have described in more detail elsewhere (Nielsen Citation2019), Richard Bayley (Citation1860, 5), who in September 1860 reported on the inauguration of the new buildings erected for the South African Public Library and Museum by Prince Alfred (1844–1900), ‘the African tribes’ of South Africa, which the British colonial power attempted to ‘civilise’, were in ‘a state of heathen barbarism […] so complex in its structure […] and, in some respects, so adapted to and so attractive to uncivilised men, that to overturn it and destroy it has been deemed by many impossible, and has been found by all who have attempted it a task of no ordinary difficulty’. Perceiving ‘African tribes’ as peoples in need of civilisation, the European colonisers in Africa attempted to establish ‘civilization and Christianity [and spread] their blessings through the boundless territories which lie beyond our borders’ (Bayley Citation1860, 6).

7 In Practicing Decoloniality in Museums – A Guide with Global Examples, which I have reviewed in the ten year anniversary edition of the Museum Worlds journal (Nielsen Citation2022b), Csilla E. Ariese og Magdalena Wróblewska (2021) present a number of contemporary examples of how museums around the world engage themselves in the decolonisation of their curatorial practices. Robert R. Janes and Richard Sandell (2019) have similarly, in the anthology Museum Activism, collected examples of how museums over the past decade have begun to seriously develop their ‘largely untapped potential […] as key intellectual and civic resources to address inequalities, injustice and environmental challenges’. Personally, I have worked thorouhgly with the topic in my PhD thesis Demanding Recognition – Curatorial Challenges in the Exhibition of Art from South Africa (Nielsen Citation2019), as well as in my current research project at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford and Musée du Quai Branly in Paris.

8 For more information about the repatriation of museum objects collected during colonial times see Karolina Kuprecht’s (Citation2014) Indigenous Peoples’ Cultural Property Claims: Repatriation and Beyond and Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Heritage edited by Elizabeth Edwards, Chris Gosden og Ruth B. Phillips (Citation2006). Thomas Laely, Marc Meyer and Raphael Schwere (Citation2018) have furthermore examined the collaboration between museums in Europe and Afrca in the anthology Museum Coorporation between Africa and Europe: A New Field for Museum Studies.

9 Daniel Park (2023) estimates that since ‘herbaria as we know them today are largely a European creation [which] grew as imperial powers expanded their colonial empires and amassed all kinds of resources from their colonies […] over 60% of herbaria and 70% of specimens are located in developed countries with colonial histories’. https://theconversation.com/colonialism-has-shaped-scientific-plant-collections-around-the-world-heres-why-that-matters-207375 [Accessed 23 August 2023].

10 https://www.kew.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/14702%20HEI%20Action%20Plan%20Final%20WebAccessible%2012%2010%2022%20updated.pdf [Accessed 18 August 2023].

11 On the website of the Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew, the Temperate House is presented as follows: ‘Travel the world in this glittering cathedral – home to 1,500 species of plants from Africa, Australia, New Zealand, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific Islands’ https://www.kew.org/kew-gardens/whats-in-the-gardens/temperate-house [Accessed 13 May 2022].

12 In its visitor brochure, Kew Gardens recommends visitors to ‘Step into the world’s greatest glasshouse’.

13 The British Museum often refers to itself as ‘a museum of the world for the world’ – amoung other places in the presentation of its travelling exhibitions, through which the museum ‘shares its rich and diverse collection of more than 8 million objects with audiences around the globe’: https://www.britishmuseum.org/our-work/international/international-touring-exhibitions [Accessed 22nd August 2022].

14 See for example ‘Kew and colonialism: A history of entanglement’ (https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/kew-empire-indigo-factory-model), ‘It’s time to re-examine the history of botanical collections’ (https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/time-to-re-examine-the-history-of-botanical-collections), ‘Botany, Trade and Empire: Discover the Miscellaneous Reports Collection’ (https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/botany-trade-empire) and ‘Addressing racism past and present’ (https://www.kew.org/read-and-watch/kew-addresses-racism) [All accessed 14th February 2023].

15 According to Sir Leander Starr Jameson (1853–1917), who was an intimate associate of Rhodes and the appointed administrator of the British colony of Matabeleland in Southern Rhodesia, the ’idea of the occupation of unoccupied Africa, South and Central, for England’s benefit, was always in Cecil Rhodes’s mind’ (Jameson 1897 in Harlow and Carter Citation2003, 532).

16 During his time as a student at the University of Oxford, Rhodes formulated the following defence of British colonisation: ‘I contend that we are the finest race in the world and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race. Just fancy those parts that are at present inhabited by the most despicable specimen of human beings, what an alteration there would be in them if they were brought under Anglo-Saxon influence’ (Rhodes 1877 quoted in Walker Citation2016, 703).

17 See among others Harris (Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2021).

18 http://www.wollemipine.com [Accessed 2 June 2022].

19 On the Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew’s website the plant collection is described as follows: ‘Our incredible living plant collections are among the largest and most diverse in the world’ https://www.kew.org/kew-gardens [Accessed 11 May 2022].

20 In the case of the collection of the life-giving quinin bark, used against malaria, which in the crown colony of India alone killed up to a million people per year, Voeks and Greene (Citation2018, 556) have argued that ‘Britain had every reason to discredit Indigenous knowledge and use of cinchona, which they ultimately did’. With access to quinin, the British Empire was capable of securing their presence in the malaria-effected parts of the world, at the expense of the newly independent states of ‘Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia [who] each lost native industry as a result of these transfers’ (Brockway Citation1979, 451), ‘the indigenous people of the Andes, whose knowledge of the healing properties of a local rainforest tree is now the world’s knowledge’ (Voeks and Greene Citation2018, 557), as well as India and the countries in West Africa, where malaria, after the prevalence of quinin, no longer stood in the way of British colonial rule (Brockway Citation1979, 451; Voeks and Greene Citation2018, 557).

References

- Ariese, C. E., and M. Wróblewska. 2021. Practicing Decoloniality in Museums – A Guide with Global Examples. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Barber, Zaheer. 2016. “The Plants of Empire: Botanic Gardens, Colonial Power and Botanical Knowledge.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (4): 659–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1185796.

- Bayley, R. 1860. Inauguration of the New Building Erected for the South African Public Library and Museum by H.R.H. Prince Alfred, Cape Town: Saul Solomon & Co., Steam Printing Office.

- BM. 1899. “Ethnographical Gallery.” In A Guide to the Exhibition Galleries of the British Museum (Bloomsbury), Printed by Order of the Trustees of the British Museum at William Clowes and Sons, 98–101. London: William Clowes and Sons.

- Brockway, L. H. 1979. “Science and Colonial Expansion – The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens.” American Ethnologist 6 (3): 449–465. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1979.6.3.02a00030.

- Connell, Joanne. 2004. “The Purest of Human Pleasures: The Characteristics and Motivations of Garden Visitors in Great Britain.” Tourism Management 25: 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2003.09.021

- Cornish, Caroline. 2015. “Nineteenth-Century Museums and the Shaping of Disciplines: Potentialities and Limitations at Kew’s Museum of Economic Botany.” Museum History Journal 8 (1): 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1179/1936981614Z.00000000042.

- Cornish, C., F. Driver, and M. Nesbitt. 2021. “Kew’s Mobile Museum: Economic Botany in Circulation.” In Mobile Museums: Collections in Circulation, edited by F. Driver, M. Nesbitt, and C. Cornish, 96–120. London: UCL Press.

- Edwards, E., C. Gosden, and R. B. Phillips. 2006. Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Heritage. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

- Frost, Alan. 1996. “The Antipodean Exchange: European Horticulture and Imperial Designs.” In Visions of Empire: Voyages, Botany, and Representations of Nature, edited by D. P. Miller and P. H. Reill, 58–79. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grove, R. H. 1995. Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harlow, B., and M. Carter, eds. 2003. Archives of Empire Volume II: The Scramble for Africa. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Harris, Stephen A. 2015. What Have Plants Ever Done for Us? Western Civilization in Fifty Plants. Bodleian Library, Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Harris, Stephen A. 2017a. “Oxford Botanic Garden & Arboretum: A Brief History.” Bodleian Library, University of Oxford in Association with the University of Oxford Botanic Garden and Arboretum.

- Harris, Stephen A. 2017b. “Seventeenth-Century Plant Lists and Herbarium Collections: A Case Study from the Oxford Physic Garden.” Journal of the History Collections 30 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhx015.

- Harris, Stephen A. 2021. Roots to Seeds: 400 Years of Oxford Botany. Bodleian Libray, Oxford: University of Oxford.

- Hoogte, Arjo R. van der, and Toine Pieters. 2014. “Science in the Service of Colonial Agro-Intrustrialism: The Case of Cinchona Cultivation in the Dutch and British East Indies, 1852–1900.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Botanical and Biomedical Sciences 47: 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsc.2014.05.019.

- Jackson, Joe. 2009. The Thief at the End of the World: Rubber, Empire and the Obsessions of Henry Wickham. London: Duckworth.

- Jackson, P. W., and L. A. Sutherland. 2013. “Role of Botanic Gardens.” Encyclopedia of Biodiversity 6: 504–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384719-5.00392-0.

- Janes, R. R., and R. Sandell. 2019. Museum Activism. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

- Kuprechts, K. 2014. Indigenous Peoples’ Cultural Property Claims: Repatriation and Beyond. New York: Springer.

- Laely, T., M. Meyer, and R. Schwere, eds. 2018. Museum Coorporation Between Africa and Europe: A New Field for Museum Studies. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839443811

- Mackay, D. 1996. “Agents of Empire: The Banksian Collectors and Evaluation of New Lands.” In Visions of Empire: Voyages, Botany, and Representations of Nature, edited by D. P. Miller and P. H. Reill, 38–57. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mosyakin, S. L. 2022. “If ‘Rhodes-’ Must Fall, Who Shall Fall Next?” Taxon 71 (2): 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.12659.

- Naumann, P. 2006. “What’s in the Box? Linneaus Legacy.” Journal of Museum Ethnography 18: 77–94.

- Nesbitt, M., and C. Cornish. 2016. “Seeds of Industry and Empire: Economic Botany Collections Between Nature and Culture.” Journal of Museum Ethnography 29: 53–70.

- Nielsen. 2019. “Demanding Recognition – Curatorial Challenges in the Exhibition of Art from South Africa.” PhD diss., University of Copenhagen.

- Nielsen. 2021. “Kunstbegrebets Koloniale Klassifikationer til Forhandling på Museer i Sydafrika.” Kulturstudier 1: 89–112.

- Nielsen. 2022a. “Botanikkens Koloniale Rødder – Kulturhistorisk formidling af plantesamlinger i Storbritanniens botaniske haver.” Kulturstudier 13 (2): 161–184. https://doi.org/10.7146/ks.v13i2.134665.

- Nielsen. 2022b. “How to Practice Decoloniality in Museums: A Review of Practicing Decoloniality in Museums – A Guide with Global Examples by Csilla E. Ariese and Magdelena Wróblewska.” Museum Worlds: Advances in Research 10: 230–234.

- Nielsen. 2022c. “‘What’s in a Name?’ Gentænkning af genstandstekster på Pitt Rivers Museum.” Jordens Folk 2 (57): 83–93.

- Nielsen. 2023. “Ambivalent Art at the Tip of a Continent: The Zeitz MOCAA and its Quest for Global Recognition.” In Global Art in Local Art Worlds: Changing Hierarchies of Value, edited by O. Salemink, A. Corrêa, J. Sejrup, and V. Nielsen, 77–99. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

- Parker, L., and K. Ross-Jones. 2013. The Story of Kew Gardens in Photographs. London: Arcturus.

- Schiebinger, L. 2009. Plants and Empire: Colonial Biospecting in the Atlantic World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvk12qdh.

- Smith, G. F., and E. Figueiredo. 2022. “‘Rhodes’ - Must Fall: Some of the Consequences of Colonialism for Botany and Plant Nomenclature.” Taxon 71 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.12598.

- Taçon, P.S.C., M. Kelleher, W. Brennan, S. Hooper and D. Pross 2006. “Wollem Petroglyphs, N.S.W., Australia: An Unusual Assemblage with Rare Motifs” Rock Art Research 23 (2): 227-238.

- Teltscher, K. 2020. Palace of Palms – Tropical Dreams and the Making of Kew. London: Picador.

- Thorogood, C., and S. Hiscock. 2019. Oxford Botanic Garden: A Guide. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford in Association with the. Oxford: University of Oxford Botanic Garden and Arboretum.

- Tricoire, D. 2017. “The Enlightenment and the Politics of Civilization: Self-Colonization, Catholicism, and Assimilationism in Eighteenth-Century France.” In Enlightened Colonialism: Civilization Narratives and Imperial Politics in the Age of Reason, Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series, edited by D. Tricoire, 25–46. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Voeks, R., and C. Greene. 2018. “God’s Healing Leaves: The Colonial Quest for Medicinal Plants in the Torrid Zone.” Geographical Review 108 (4): 545–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12291.

- Walker, G. 2016. “‘So Much to Do’: Oxford and the Wills of Cecil Rhodes.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 44 (4): 697–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2016.1211295.