ABSTRACT

An ambitious reform programme in the UK to digitalise the justice system has been underway since 2016. The recent report carried out for the Administrative Justice Council (AJC) by the authors Digitisation and Accessing Justice in the Community, described how prepared advice providers were for giving digital assistance concerning welfare benefits, and found that organisations were unable to meet the demand for services across all levels of social welfare law, and that there was a high level of demand for digital assistance. This paper then adds data from the follow up Welfare Advice Survey carried out for the JUSTICE/AJC benefits reform working party by the authors, which examines the technical capability of the advice sector to provide remote social welfare advice delivery after the onset of the pandemic (see fns 1 and 3 below). The paper describes how advice providers have been working during the first seven months of the pandemic in 2020 and how the migration to remote advice delivery has changed their services and impacted on their clients. A conceptual framework of needs is then developed and offered as a lens through which to think about the new sets of demands on advisers and clients.

Introduction

This paper is concerned with access to social welfare [law] advice in general, and how it has been affected by digitisation and the pandemic in particular. The pandemic has made the need for remote advice delivery a premature reality, leaving many ‘vulnerable’ groups without access. The discussion is situated in the overall context of the court digitisation agenda that the Ministry of Justice has been pursuing since 2016. The paper is based on two surveys. The first survey is reported in Digitisation and Accessing Justice in the Community (Sechi Citation2020).Footnote1 It was conducted before the pandemic (late 2019) to explore how prepared the advice sector was for the transition to digitally assisted service provision. The pandemic in 2020 radically changed how the advice sector was operating, leaving the findings of the Digitisation and accessing justice in the community report somewhat unnoticed. As part of the JUSTICE/AJC working party on Reforming Benefits Decision-MakingFootnote2 (which looks specifically at the challenges faced by clients and social welfare advice providers during the pandemic), the authors decided to run a second survey to explore how advice providers were coping with the provision of advice in these unprecedented circumstances. This second survey Pandemic Welfare Advice SurveyFootnote3 was conducted after the first pandemic lockdown in 2020. We argue that the delivery of remote advice has produced new categories of vulnerabilities while erasing other vulnerable groups from accessing advice. This paper advances a conceptual framework of needs that has been developed out of the survey data, to help improve understanding of the situation.

Setting the scene

The ambitious court reform programme ‘Transforming our Justice System’ (Mo Citation2016) includes a shift to digital provision of justice. This means that people will engage and interact with the justice system through new digital pathways rather than through traditional paper-based and face-to-face ones. The third phase of the reform programme is expanding online services with a promise, however, to also retain paper-based procedures (HM Courts & Tribunals Service Reform Update Summer Citation2019). A worry remains about online services and access to justice for those who are digitally challenged and digitally excluded (JUSTICE Citation2018). As the Bach commission found: ‘Technology has the capacity to enhance, empower and automate, but it also has the potential to exclude vulnerable members of society’ (Fabian Policy Report Citation2017). Although assisted digital services are part of the reform programme (MoJ Citation2016) so as to safeguard against exclusion (Low Income Tax Reform Group Citation2012), it is essential that the design and implementation of any assisted digital support and any remote method of working is able to catch and support those who are most ‘vulnerable’ (Brown et al. Citation2017). Many ‘vulnerable’ and disadvantaged individuals have already been affected by austerity and following the effects of the introduction of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act Citation2012 (LASPO). The provision of advice in the context of the post-implementation review of LASPO in 2019 (MoJ 2019a) commits MoJ in its action plan to ‘explore how to deliver services remotely to those who are geographically isolated and may not have easy access to local providers’ (MoJ Citation2019b).

The report on Digitisation and Accessing Justice in the Community (Sechi Citation2020), finds that ‘many of the respondent organisations have service users who are “vulnerable” and the most needy in society. A large number of people approaching advice providers for help with a legal problem would need support and legal advice, together with ongoing digital assistance to navigate an online justice system’ (ibid , p. 7). Obtaining legal advice can help prevent problems from becoming unmanageable and assist people to access their rights. The Low Commission follow-up report found that people being left without early advice and possible redress makes services less accountable to their users (Low commission Citation2015).

This discussion has taken a radical turn. The COVID-19 pandemic forced advice service providers to move to remote service delivery, practically overnight, in March 2020. The well documented clustering of people’s legal problems (Genn Citation1999, Pleasence and Balmer Citation2014) has been exacerbated by the pandemic (e.g. challenge to accessing legal advice, buildings closing, court delays). This paper builds on empirical research into how the advice sector has been coping in the new everyday provision of advice to its clients. As Lindsey Poole puts it:

The experience of the advice sector over the past few months has been something of a roller coaster ride, full of lows and highs, but now arriving at a clearer and more secure position. There are concerns regarding both the long-term survival of all pre-Covid19 services and the on-going capacity of the sector to cope with the anticipated level of advice needs at current resource levels. (Lindsey Poole, director Advice Service Alliance Citation2020)

The advice landscape has changed dramatically due to the pandemic. Those who provide advice and those who receive advice are confronted with different sets of challenges. The provision of advice has become a question of having the appropriate IT equipment for a home office, a reliable internet and telephone connection (Burton Citation2018), and a new set of skills to provide remote service delivery. For those who seek advice the landscape has become rather challenging, and for some, impossible to navigate. Those who are Internet savvy and are used to conducting everyday life on their devices are better able to access the remote services than those who are digitally challenged or excluded. There are cohorts of people for whom digitisation presents an unsurmountable obstacle (e.g. those who are digitally excluded, or digitally challenged, people with certain additional needs, some people who are blind) and in the shift to remote service provision, care needs to be taken not to create a societal class of ‘digitally abandoned’. A similar concern arises in studies about remote hearings as to how realistic it is for people to join without the technology or good internet connectivity (Byrom et al. Citation2020).

The concern about the impact of the pandemic on the advice sector gave rise to a new collaborative online forum, a legal and advice sector roundtable. The round table meets once a month, under the Chatham House Rule, provides information exchange, learning and cross-sector working, and serves as a channel for communication with government bodies. This collaboration brings together organisations from the broader advice sector and includes funders and other representatives.Footnote4 The issue of the shift to a remote way of delivering advice and the impact both on the advice sector and the end service user is frequently debated and, while recognising that the advice sector has responded well, with a lot of good work already happening, it is acknowledged that access to services remains a concern for particular communities and those with complex needs.

We discuss these issues in this paper in five parts. Part one offers a brief background to the advice landscape in the England and Wales; part two provides the methodology and introduces the empirical dataset; in part three the data is discussed with a focus on the delivery of advice during and after the pandemic; part four presents a conceptual framework and part five concludes the paper.

Part 1: the advice landscape in England and Wales

The advice landscape in England and Wales is made up of well-known national advice services such as Citizens Advice, Law Centres and other independent advice agencies within the voluntary sector including not for profit organisations, charities, housing associations and community centres. Some of these advice providers offer specialist advice, including legal advice, and many are members of umbrella bodies such as the Advice Services Alliance (ASA) and Advice UK. Some also offer outreach services delivering advice to the community (Selita Citation2019) and in NHS settings (Woodhead et al. Citation2017), for example. The provision of advice also forms part of many public sector organisations such as local councils and probation services. MPs also offer advice to their constituents and trade unions offer advice to their members. Some faith-based groups and ethnic minority groups provide advice to their communities and the people they represent. All of these different organisations and entities provide different levels of advice (e.g. formal, informal, specific, generalist) and form the matrix of the advice sector landscape in the UK (Law Society Citation2019). This paper is mainly concerned with the provision of welfare advice (e.g. debt, benefits, housing, employment).

Jurisdiction impacts on the legal aid funding for advice provision. The availability of legal aid that funds the provision of advice is different between the UK jurisdictions. England and Wales have had very harsh legal aid cuts which have not taken place in Scotland and Northern Ireland. This makes a difference to the sustainability of advice services which rely on legal aid funding for their income. More income security or resources might mean that services are better equipped to engage with technology, and/or have been better equipped to deal with the immediate implications and aftershock of the pandemic (Law Centres Network Citation2020). This paper focusses on England and Wales.

The advice landscape in England and Wales has been heavily impacted by LASPO (Sommerlad and Sanderson Citation2013, Organ and Sigafoos Citation2018). Despite the commitment by the MoJ to explore how to better deliver remote services to those who are geographically isolated and not able to access services, the advice sector has taken a significant hit. In a report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (Equality and Human Rights Commission Citation2018, p. 6) the ‘emotional, social, financial and mental health impacts for individuals who have attempted to resolve their legal problems without legal aid, following LASPO in 2013’ is explored. LASPO brought funding cuts to legalFootnote5 aid and made it difficult for individuals to access legal advice in areas such as employment (Maclean and Eekelaar Citation2019), family (Trinder and Hunter Citation2015) immigration (Organ and Sigafoos Citation2018) and welfare benefits law (George Citation2019). The lack of legal advice resulted in many people being financially deprived leading to detrimental effects on security and wellbeing. The removal of welfare benefits law, for example, from the scope of legal aid has had a significant impact on the advice landscape and individuals in search of support (Organ and Sigafoos Citation2018).

Against this setting, those worst hit by the pandemic have been those who were already struggling to access the system of advice and justice. This is reflected in the most recent reports from advice providers: law centres, Citizens Advice, ASA and Advice UK which will be briefly discussed in the following selection.

This year saw the 50th anniversary of Law Centres, and in their report ‘Law for All’ (Law Centres Network Citation2020) the issues facing Law Centres and the advice sector created by the pandemic were addressed. The change in demand for certain types of advice was particularly marked in employment law where Law Centres reported a five-fold increase. Concern was raised in the report about a new client group emerging of those who were having to seek advice for the first time, while traditional clients such as those with mental health problems were failing to engage with a remote service provision. The report noted:

The demographic of Law Centre clients has changed and a new group of Living Outside of Legal Aid (LOLA) individuals are finding themselves in need of support that is not covered by Legal Aid funding. These new clients may be more aware of their rights than more traditional clients, but they are often first-time users of Law Centres. Many traditional clients who rely on face-to-face services due to language and health barriers, or who cannot access digital services due to poverty or inexperience, now largely do not access Law Centre services or other frontline advice services (Law Centres Network Citation2020, p. 9).

Citizens Advice reported that the areas they advise on have shifted in the pandemic. Their most frequently used four areas of advice provision are benefits and tax credits, universal credit, debt and employment. When compared to demand in August 2019, the order changed to: benefits and tax credits, debt, universal credit and housing; it can be seen that the need for employment advice has increased (Citizens Advice Citation2020a). One of the main issues people sought advice for was redundancy which, given the impact of the lockdown on the economy, is unsurprising. With a focus on accessibility of advice, Citizens Advice is advocating for a new approach and for a process to be built around those who need it the most. This process needs to be built around a recognised, trusted and implicit consent process in order to improve confidence in accessing digital services and sharing personal information (Citizens Advice Citation2020b).

In line with the appeal by Citizens Advice for a new way to ensure accessibility to (digital) advice provision for those who need the services the most, the ASA (Advice Service Alliance Citation2020) found in their report on the impact of social welfare advice in Advising Londoners that

Despite channel shift and increasing use of new technology, most consultees and respondents believed that the most vulnerable Londoners need holistic, face-to-face advice services. But in many agencies this kind of advice now tends to be reserved for people who have difficulty with telephone and online access (Advice Service Alliance Citation2020, p. 87).

The report also found that the shift to online processes was a huge change for clients and advice providers. The transition to ‘digital by default’ has spread throughout all public services, including local authorities, tribunals, courts and some health services settings. It characterises Universal Credit, the main benefit for those people of working age. As seen in other reports during the pandemic, there are worries about the exclusion that clients face if they cannot access the technology to reach the service providers.

The principal characteristic of good online advice resources is that they supplement and augment frontline services, not replace them (Advice Service Alliance Citation2020, p. 88).

This raises important issues around principles of good online advice delivery. Advice UK (Citation2020) published a briefing for its members in a guidance and resource guide for advice services and organisations covid-19 in June 2020. This report aims to ‘help AdviceUK members to consider, manage and respond to the impacts of COVID-19 on their organisations and the individuals and communities they advise and support’ (Advice UK Citation2020, p. 5). Among other things, the report lists areas in which AdviceUK members need to particularly consider the impacts of the pandemic. This is a welcome start to collecting best practice for a model of post-pandemic advice provision where lessons learned during the pandemic can be transferred into a new, possibly hybrid way of working.

In sum, the advice landscape in England and Wales has been hugely affected by the pandemic. The shift to remote delivery has created challenges for clients as well as for advice providers. We sought to explore how these effects had manifested themselves in daily practice. To do so, we designed a Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey and distributed it to advice providers in England and Wales. The next part introduces the methodology and the dataset.

Part 2: methodology and empirical dataset of the pandemic welfare advice survey

Method

In 2019, the Administrative Justice Council (AJC) surveyed the advice sector on its capacity to deliver digital support services as part of the court and tribunal modernisation programme. A Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey was conducted which resulted in a report on Digitisation and Accessing Justice in theCommunity(Sechi Citation2020). Since then, the pandemic changed the way in which advice is provided and we designed the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey to get a better understanding of how advice providers have been working during the pandemic, and how the migration to remote advice delivery has changed their services and impacted on their clients. This paper offers descriptive statistics of the dataset and provides an analysis of the answers to the open-ended questions. The narratives inform the theoretical framework below. Further analysis of the survey will form a report that will be published in support of the JUSTICE/AJC working party on welfare benefits reforms.Footnote6

The online Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey was sent out to advice providers by JUSTICE,Footnote7 for the AJC/JUSTICE working party on Reforming Benefits Decision-Making.Footnote8 Its main aim was to better understand the challenges the pandemic posed to those who deliver welfare advice, and how they perceived the impact on those whom they advise. We designed the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey as a mixture of closed Likert style questions as well as open-ended questions. This survey was anonymous, but organisations were encouraged to leave their contact details for follow-up information about publications. As with the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey, JUSTICE sent the link to the online Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey to contacts provided by their advice sector networks and the AJC networks: Advice Service Alliance, Advice UK, CA, law centres. This means that we used the same approach to the sample as in the previous Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey. Advice providers were encouraged to share the link with others. The survey was live between September 14th – 29 October 2020. The online link to the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey was sent out in two waves, in the first wave the link was sent to 328 service providers and in the second wave the link was shared on twitter. The twitter link added 13 responses which brings the total number of responses to 133. If we only count the email links that were responded to, the response rate is 37%. The sampling frame was limited, we were aware that we were sending the survey to organisations that are offering their services in the middle of a pandemic and as such had a certain degree of survey fatigue. 37% is not a representative sample, and we did not send the survey to all advice providers in England and Wales. This survey does, however, give us a good sense of the shared themes and issues faced by the advice sector during the pandemic.

The dataset

The dataset has a quantitative and a qualitative element. Quantitative data was collected about the type of organisation, the type of social welfare [law] advice provided, how well the organisation is placed to move to remote delivery, how they communicated with their service users and how all of this worked during the pandemic. Further, the advisers were asked to explain how the remote delivery of advice impacted on themselves and their clients in open-ended questions. A summary of the answers follows, divided into type of organisation and advice, remote delivery of advice, and impact on delivery and clients. The descriptive tables below (–) show respondents’ answers to the categories provided in the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey. Some questions were multi-answers and others were one choice answers; this is identified in the tables. Where necessary a question had an ‘other’ response option to provide the respondent with the opportunity to elaborate and clarify their answer. Each table has the population size (n) that answered the question.

Type of organisation and advice

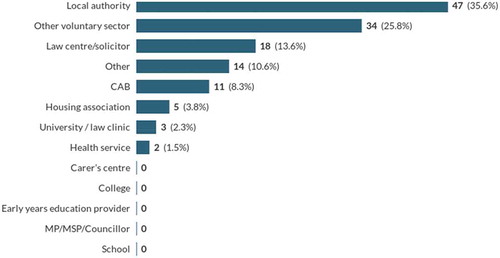

shows the different types of organisations that responded to the survey, ordered by self-identification with the set options. The respondents who chose other were specialist charities (e.g. NHS, legal advice centre, DIAL, welfare rights service, department for communities, national charity).

Multi answer: Percentage of respondents who selected each answer option (e.g. 100% would indicate that all this question’s respondents chose that option)

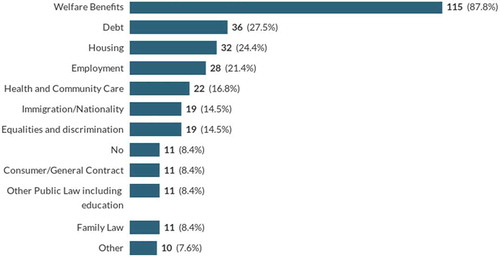

shows the type of social welfare advice the respondents reported that they provided.

The vast majority (87.8%) of respondents were helped with welfare benefits, with debt and housing being the next most prevalent areas, 27.5% and 24.4% respectively. The finding that welfare benefits was the most common area for advice is commensurate with the findings in the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey. The rise in claims for Universal Credit during the pandemic will no doubt have served to increase demand for assistance even further.

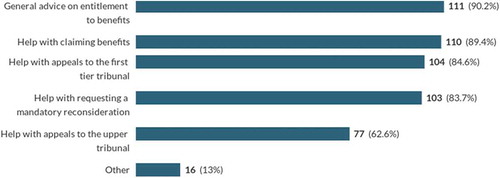

below provides a breakdown of the levels of assistance the organisations provide for welfare benefits. This ranges from general advice on entitlement to benefits, help with claiming benefits, help with requesting mandatory reconsideration, help with appeals to the first-tier tribunal and help with appeals to the upper tribunal. The ‘other’ areas covered for welfare benefits include public law solutions, case work, intermediary dispute resolution, advice on judicial review, training on benefits and providing second tier support, for example.

Remote delivery of advice

In response to the question of whether their organisation was well placed to move to remote advice delivery (n = 131), 81.7% responded yes and 24% responded no. Further, 81.1% stated that they had the necessary software and 18.9% reported they did not (n = 132).

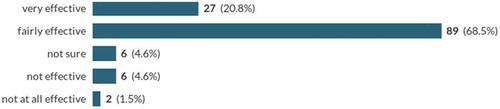

shows the answers to the question about how effective advice providers thought the remote delivery was. Here the majority (89.3%) reported that the delivery or remote advice was very (20.8%)/fairly effective (68.5%).

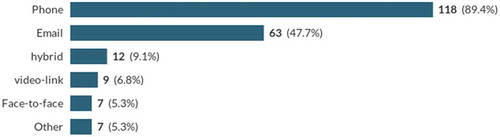

gives the frequency for each mode of communication as telephone (89.4%), followed by email (47.7%), a hybrid model (9.1%), video-link (6.8%) and face-to-face (5.3%).

Multi answer: Percentage of respondents who selected each option (e.g. 100% would show that all respondents chose that option)

Impact on delivery and clients

Whilst the majority of respondents felt that the delivery of remote advice was effective, this could indicate the respondents’ view of the actual mechanics of the technology rather than the effectiveness of service users’ ability to understand and act on the advice.

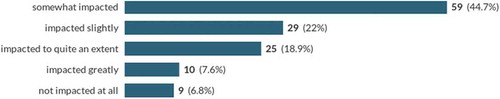

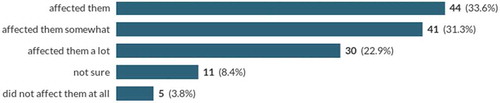

show the responses to questions about the perceived impact on the relationship between the advisor and the client and the impact upon the clients’ experience of the service. shows that 44.7% of respondents felt their relationship with their clients was somewhat limited by remote delivery. And , most significantly, shows that most advisers believed that their clients have been affected by the remote delivery of advice.

When asked what the advisors think was most problematic for the clients who reached out to them (n = 131), they reported the ability to provide necessary documentation (86%), the ability to access the services (53.5%), the ability to understand the information (52.7%), the ability to act on the information (51.9%), and the ability to tell their story (41.1%). To a follow up question, asking if clients have problems understanding advice given, (n = 131), 64.9% responded yes and 26% responded no, whereas 9.4% gave other responses which included:

It’s difficult for me to tell. I think I’ve managed to foster a decent understanding via phone and email, but it is sometimes difficult to gauge remotely whether a client is understanding the information I am imparting.

It’s very hard to tell if advice is understood in those cases where it’s just general initial signposting. When representing or acting for client in more complex matters it is easier to tell if they understand.

We analysed the qualitative data by reading through the responses to the open-ended questions which allowed us to identify emerging themes. These themes informed a conceptual framework which will be introduced below.

Emerging themes

The changes in the advice sector as a whole have affected the people providing advice, their particular organisations and, of course, the clients they advise. In what follows we present four emerging themes we identified by analysing the dataset: changes in demand, the move from face-to-face to telephone, the move from paper to digital, and the wellbeing of advisers.

Change in demands

The sector has had to respond to a significant change in demands, and some of this affects advisers and their clients. As noted elsewhere in this paper, advice service providers have had to adapt both to the delivery of remote advice and in many cases to a changing demographic of service users. Some of the advisers reported that the profile of their clients had changed, and that they had lost touch with certain communities, for example BAME clients. The latter group, as well as other groups, may be more likely to experience social welfare problems to start with (existing legal needs), which means that the groups who are already struggling are affected further (Genn Citation1999, Pleasence and Balmer Citation2014).

As reported by many advice providers in the dataset, the service overall is slower due to several factors. For example, most advice providers are working with a reduced capacity (including a loss of volunteers), while the volume of contacts (requests for particular assistance) is going up. This is especially so for requests for assistance with employment issues. Advisers are not able to provide the same level of service and advice, including the emotional support for their clients, that they are used to when dealing with them face-to-face. This makes the process much more time-consuming for all parties. Clients have reduced access, mainly due to digital exclusion (low income, lack of technical devices, poor communication skills) and their needs are often complex, presenting as more urgent during the time of the pandemic with remote interactions, or lack thereof.

The move from face-to face to mainly telephone advice

Advisers reported that the interaction on the phone is just not as good as being able to interact face-to-face with clients. This mode of communication poses special difficulties for clients, for instance, who are autistic, elderly, have anxiety disorders, sensory impairments, language barriers or literacy issues. As a result, advisers spend more time on the phone with their clients especially those clients with more complex needs who are not easily able to access advice during the pandemic. This resonated with the findings of Balmer et al. (Citation2012) that telephone advice takes longer than face-to-face advice and that the mode of advice differs between clients with particular demographic characteristics. In other words, existing challenges have been reinforced through the pandemic.

The move from paper to digital

The need for evidence in many cases, such as evidence in support of claims or to support applications and to verify facts, requires the provision of documents. This is not straightforward with remote service delivery and can cause delays, especially for those who have difficulty with technology. Some clients send documents by post which further delays the process, and some advisors reported challenges with form filling when not seeing clients face to face. Advisers also reported that using remote technology and IT services poses a significant challenge to some of their clients and alienates them from the process. It is an ongoing challenge to communicate effectively with those clients.

A transition to digital welfare claims occurred in 2012 when the government created Universal Credit which consolidated social security benefits into a single monthly payment (Stuart and Browne Citation2013). The aim of the move to digital by default was to ease access for claimants and to save money when delivering this online service. The outcome revealed, generally speaking, resembles what we found in the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey: that government’s digital aspirations are not matched with vulnerable users’ needs and capabilities (Tarr and Finn Citation2012, Toh Citation2019).

Wellbeing of advisers

Some respondents highlighted the fact that they themselves felt isolated working from home. They miss being close to their colleagues and the opportunity to ‘pick their brains’, have discussions over lunch and miss the general social element of the job. Another major obstacle that advisors working for smaller charities reported was the lack of equipment and the lack of multilingual volunteers. In addition, some respondents noted the isolation and loneliness of working by themselves at home. This is a phenomenon the pandemic induced and it needs attention. Advice providers have to make sure that the wellbeing of their staff is looked after in this challenging time.

Part 3: discussion: delivery of advice during the pandemic

Let us now discuss the emerging themes from the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey in conjunction with the findings of the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey. The data resulting from the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey highlights the extraordinary situation the pandemic has created for the delivery of welfare advice. The Digitisation and Accessing Justice in the Community Report (Sechi Citation2020) concluded that there were serious concerns about funding, equipment and staffing of welfare advice organisations. It offered the following four key findings: (1) there is a high level of need for digital assistance; (2) barriers are preventing frontline advice providers from meeting demand for digital assistance; (3) lack of funding was preventing organisations from being able to scale up not only in terms of offering digital assistance but being able to offer essential face to face advice; (4) organisations were unable to meet demand for services across all levels of social welfare law. The report concludes that front line advisers are already overstretched and at capacity. Finally, the report found that many people approaching advice services with a legal problem in the area of social welfare, for example, would require digital assistance to navigate the online justice system. The demand for digital assistance cannot be met, which means that vulnerable groups are not able to access justice.

The data gathered for the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey was collected a few months before the pandemic spread. The emphasis of the report was to explore the advice sector’s preparedness for the court modernisation programme which includes a shift to a remote way of working and digitisation of the justice system. The concern was about the delivery of access to justice and whether a move to digitisation could also ensure that the digitally challenged would not be left behind. Only a couple of months after the Digitisation report (Sechi Citation2020) was published, the pandemic forced advice provision to go online by default, speeding up the digitisation and remote delivery process under the court modernisation programme. This created a challenge for the provision of, and access to, advice.

The Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey is a follow-up to the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey and explores how advice providers have managed this abrupt transition. As found in the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey, there are different types of service providers who face different challenges. Further, the surveys have different sets of questions, different sets of organisations responding and different response rates. This means that there can be no direct comparison between the two surveys; rather, the responses serve as an indication of what shared challenges and potentials are in the provision of advice during the pandemic. The pandemic survey allows us to consider whether the shift to a remote way of working with more reliance on digital technology has heralded the challenges as anticipated by the responses articulated in the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey. We take the four key findings of the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey as a starting point to discuss the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey responses.

The pressing need for digital assistance

Frontline advice providers had reported in the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey that they were not prepared for the provision of digital assistance to support their clients to access the justice system (LEF Citation2019, Tomlinson Citation2020). They identified that between 35–50% of their service users would require digital assistance and support to access the digital justice system (p. 7). This is also clearly reflected in the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey responses. Some services were able to adjust to digitally assist most of their clients, but not those most vulnerable. An example of a common concern:

For the most part, we have been able to successfully work remotely and have taken measures to adapt our services to continue supporting clients. However, we do believe that there are extremely vulnerable individuals who we have not been able to access due to the restrictions in being able to meet with them face to face. We have seen an increase in the strength of partnership relationships which has helped us in still reaching some vulnerable clients.

It is clear that the shift to remote service delivery has led to a radical exclusion of those who are not able to manoeuvre in the digital space. As found in the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey, the move from face-to-face to telephone advice has been quite a challenge for those who are used to seeing advisers in person. Several advice providers reported challenges for their vulnerable clients, ranging from clients not having enough data on their mobile devices to being digitally excluded. It is evident that the clients who have been most affected are those who are digitally excluded and/or housebound. A common example:

They cannot drop things into our office or do things online/via email and we have been prevented from going to see them. The most vulnerable clients are the ones who have been most affected by the restrictions on how we can work.

Other respondents from the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey report that the shift from a largely in person service to an almost entirely telephone and digital one poses an opportunity to digitally innovate. They report that the forced transition to remote digital assistance by the pandemic has accelerated their programme of digital innovation and allowed them to experiment with various channels; for example branching out to the use of video advice and social media platforms. This particular respondent, unlike others we have highlighted, reported helping more people now than they did before the pandemic. Interestingly, there is a new user group that was created through the pandemic, one that is faced with seeking welfare advice for the first time. The concern about those who do not have access to appropriate equipment, broadband or those without sufficient digitals skills remains.

Several respondents reported that they are working more closely with community spaces and services to try to reach those clients who have fallen through the digital space.

Barriers to meeting the demand for digital assistance

The Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey described the barriers to meeting the demand as lack of funding, not enough staff, no appropriate IT equipment, not enough space and a lack of expert knowledge. While most of these barriers remained the same during the pandemic, solutions had to be found quickly. For many advice providers the solutions meant a considerable reduction to their service. In turn, this meant that some client groups have disappeared and others present with challenges to the remote reception of advice.

A common concern of respondents of the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey was to foster a similar rapport with the client over the phone and via email as it is not straightforward to gauge remotely whether their clients are understanding the information. Some advice providers solved this by adding a series of checks which meant more time spent on each case. Here, language barriers and clients with mental health problems posed an additional challenge, as mentioned by many respondents. Some advice providers have used multilingual volunteers to help communicate and some reported additional funding for digital exclusion to provide SIM top ups and technology to clients. Respondents reported a greater use of WhatsApp as it suits younger clients. In turn, some of their elderly clients rely on their family members to support them in their interactions which was not the case previously. When advising those who are most vulnerable and needy, the respondents agree that face-to-face encounters are essential.

Lack of funding prevents upscale of IT and face-to-face

The Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey found that advice providers needed funding to provide digital assistance as well as for the delivery of face-to face advice. These issues have become more prevalent during the pandemic. Some selected examples from the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey state that much can be done over the phone, but the pandemic has also highlighted for those participants how important home visits and face-to-face contact are for vulnerable clients. In particular, for those clients with more complex needs, poor literacy, and digital disadvantage, telephone advice has not been able to meet their needs as effectively. Additionally, for those who have a hearing impairment, or other language barriers, this is not a good way to deliver services. Similarly, for those with mental health and learning difficulties, a phone service is not the best way to deliver and receive services. This mirrors a reoccurring theme in the literature, which is the lack of funding for advice provision and its impact on those who are most ‘vulnerable’ (Morris Citation2013). Sommerlad and Sanderson (Citation2013) set LASPO in its historical context and argued that the policy discourse of consumerism and responsibilisation has led to the radical development of cuts and ultimately left service providers unable to deliver their services.

Unable to meet demands for services across all levels of social welfare law

The Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey found that the advice sector was not able to meet the demands across the complex landscape of service and diverse client base. This situation has also become more prominent during the pandemic; especially as a new client group has emerged competing with the demands from the traditional client groups. The responses to the pandemic survey showed, however, that there is a huge amount of goodwill and flexibility in the way that advice is provided.

We predict that this will come to a turning point as we find ourselves coming out of the third lockdown. The third lockdown (beginning in January 2021) has seen the advice sector more prepared for remote delivery of services, but access to justice is still compromised especially in light of the changing demographics of those seeking help and there is a real concern that those clients who traditionally would use the advice sector have disappeared. As noted by the Information Law and Policy Centre:

Policymakers need to move away from making assumptions that all users will have access to technology or that technology is a more efficient means of advice. Such assumptions do not take into account the ‘digital divide’ that exists, nor the diversity in relation to digital literacy skills and the variety of specific challenges faced by clients with disability, those from culturally and/or linguistically diverse background, older people and others (Gordon et al. Citation2020).

This section used the Digitisation report’s (Sechi Citation2020) findings as a starting point to put the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey findings into context. It shows clearly how the issues and fears the advice sector reported facing when asked about assisted digital, came to full fruition in the provision of advice during the pandemic. As a theoretical contribution, the data allowed us to identify similarities between the responses and to construct a conceptual framework. This framework is aimed to further understanding of the situation that the advice sector is facing and to help develop targeted solutions.

Part 4: a conceptual framework of needs: access to advice during the pandemic

We propose a conceptual framework of needs based on the empirical data collection and informed by literature and reports on advice provision during the pandemic discussed above. The aim of this conceptual framework is to group the phenomenon of advice provision during the pandemic into distinct – yet related – categories (Hatch Citation2002).Footnote9 The conceptual framework below is inspired by the patient centred accessibility framework (Levesque et al. Citation2013). This model is attractive as there are substantial cross-overs in the conceptualisation of access. While in the healthcare setting access is understood as the ability of the population to seek and obtain care (Frenk Citation1992), this translates into the justice setting as the ability of the population to seek and access advice (and redress). Therefore, the framework () is adapted broadly to the welfare advice setting during the pandemic. The categories are a tool for understanding better the needs that arise for the provision (advisers), the receipt (clients) and the access (vulnerable clients) to advice. This has immediate implications for access to justice and advice.

Five main categories form the stepping stones in the centre of this model. These are social welfare needs, perception of needs, advice provision settings, access to the setting and the outcome. There are two main perspectives on this pathway, the service providers (top row) and the capacities of users (bottom row). To make services accessible, the providers need to ensure four dimensions of accessibility: (1) approachability, (2) remote delivery, (3) availability, and (4) presence. The six dimensions at the bottom relate to users’ abilities to interact with the categories to realise access. These include (a) capacity to perceive (a need), (b) capacity to seek (help), (c) capacity to reach (advice), (d) capacity to access (an advice setting), (e) capacity to engage and understand (with the adviser and the advice provided), and (f) unmet needs (people who are invisible due to not being able to access remote services).

Advice providers

Approachability of service means that people who have welfare benefit needs have to be identified and signposted towards the services. During the pandemic this is the largest challenge. While advice providers are busier than ever, this is not necessarily because of more clients, but rather about individual assistance and casework taking much more time. This is related to the phone replacing the face-to-face consultations and creating delays in practical matters of understanding, form filling and being able to obtain documents. A further aspect is the added hurdles for certain vulnerable groups. In other words, the service providers are not only faced with a range of new challenges that technology forced upon them but they also have to find a way to reach out to those clients who are just not able to approach them.

Remote delivery as the new normal during the pandemic is a challenge that has been met in a variety of ways by advice providers. Each one of them was faced with different sets of obstacles to overcome. For some it meant that the technology was not available, or not able to perform the requisite tasks from a remote access point. For others, remote delivery meant switching to telephone and email to be able to interact with their clients. There was a clear sense in the data that, although the remote delivery might be working for some clients, others just cannot do without face-to-face interactions.

An added dimension to consider is that of the adviser’s wellbeing. Our data highlights that some advice providers, working from home during the pandemic, are feeling isolated, miss the interaction with their colleagues and are struggling with technology. These are added pressures that have been created through the remote working situation and we cannot tell what the long-term effects will be.

Availability refers to the service provision and if it can be reached easily. This concern is twofold. First, due to the remote service delivery, and as seen in the data, many clients are cut off from accessing existing services. There is additional work to be done to assist these individuals to find the support they need. Second, and related, the data showed that there are not enough advice providers to meet the demand. This reflects the shrinking of the advice sector in general and how, in the current climate and moving forward, the issue of the continued existence of the advice sector may be a real concern. An additional client group has been created through the pandemic. These are clients who, for the first time, find themselves in a situation of having to claim benefits and access advice at a time of personal upheaval such as loss of job and family related matters.

Presence refers to the lack of advice provision which leaves people’s needs unmet both due to their abilities but also due to the fact that there are insufficient remote services to meet the need for them. In order to deliver a remote service, there needs to be an infrastructure and the shrinking of the advice sector means that the infrastructure is also compromised.

Users

Users have to be able to accept that they have a problem for which they need to seek help. This can be quite a challenge (Ewick and Silbely Citation1998, Genn Citation1999, Buck et al. Citation2008). Once a person is aware that they need to seek help the next step is to reach out, access and engage with the service provision. This process is heavily influenced by the pandemic. Our data shows that it has become harder for ‘vulnerable’ people to access service providers. The majority of users who used to walk into an advice setting and expect to see an adviser face-to-face, are now cut off. Despite a considerable effort to communicate to clients that, although the doors are closed, they can still reach out over the phone or online, many are not able to do so. Furthermore, this is also limited by the restrictions laid down by the pandemic.

For example, many people calling advice lines during the pandemic will have been exposed to automated messages saying that they should leave their details, and someone would get back to them. This has been exacerbated by the high volume of calls during the pandemic. The ability of service providers to return calls during this period has been delayed due to this high volume of calls and a lack of staff and volunteers able to assist. With advice centre doors being closed, those people unable to access phone services were left with nowhere to go and no immediate access to any assistance.

Unmet needs. Certain groups of clients are not accessing the system any more. The data suggests that clients have vanished from the system due to remote access. These ‘disappeared’ clients are typically digitally and socially excluded and used to having face-to-face interactions. During the pandemic they have literally fallen off the radar; they are digitally abandoned.

The proposed conceptual framework highlights the areas that need desperate attention when thinking about the delivery of welfare advice during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. The abrupt switch to remote service delivery has seen existing challenges to the advice sector and its clients base expand and new ones being created. The framework focuses on the challenges faced by advice providers and service users, and also identifies groups that have been left behind. The framework might help focus attention on these areas and provide a basis for consideration of solutions.

Part 5: Conclusions

In this paper we discussed the shift to remote and digital delivery of welfare advice during the pandemic. Based on two surveys (Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey and the Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey) we were able to empirically capture the growing concerns that came to light in the provision of remote advice. We built on emerging patterns in the data and the literature and developed a conceptual framework. The framework, broadly speaking, identifies three areas of concern. First, a concern about the advisers’ ability to deliver advice in the current setting, as well as their wellbeing. Second, a concern about clients’ capacity to access and take full advantage of the services. Third, a concern about those clients who have been cut off from the services due to the pandemic and remote delivery. We call this group the digitally abandoned.

What lessons can be drawn from the empirical findings? Urgent work has to be done to support the advice sector in their provision of advice and to enhance and enable accessibility for a diverse cohort. With growing demands and people working from home the sector is stretched to a worrying degree. While office-based working may return post pandemic, the way services are provided will change and hybrid models encompassing face-to-face, telephone, email and digital platforms will be the norm. This will cater to the needs of the diversity of service users but can only work if the advice sector is supported and funded to fully adapt. This is echoed in the foreword by Julie Bishop in the Law for All report: ‘Let us work together to “build back better” people’s access to justice in the UK’ (Citation2020, p. 7).

This discussion raises wider concerns about the sector as a whole. What future does the advice landscape have? A great deal has been written about the benefits of early advice provision (Baring Foundation Citation2013, ISPOS MORI Citation2017). There is both social welfare and economic value in [early] advice. There is a large evidence base on the social value of welfare advice, especially in relation to debt advice (Cookson and Mould Citation2014). Research has shown that problems tend to cluster (Genn Citation1999, Pleasence and Balmer Citation2014). This means that the effect is cumulative on a person’s life and the resulting choices have a direct effect on their circumstances, to prevent potential spiralling into more and more problems. The idea is that a person experiencing problems (debt, housing, welfare …) could receive advice at an early stage to gain help with these connected issues, to start to move beyond them (McKeever et al. Citation2018).

The Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey has shed some light on the wider cracks in the system. The reality of a shrinking advice sector is emerging. The Pandemic Welfare Advice Survey explored how existing agencies adapted quickly to a remote way of working. This still left many clients’ needs unmet. The reasons for this are both the fact that remote service is just not accessible for all; but also the fact that not enough services exist to serve the demand. Therefore, we conclude that although remote services may have addressed some of the issues regarding pre-existing geographical problems and the so-called advice deserts (Advice Service Alliance Citation2020), the advice agency and infrastructure must first exist for there to be a remote service.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mavis Mclean for her support and patience, Jess Mant, Ciara Fitzpatrick, Ian Loader and the anonymous reviewer for constructive comments and feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. We also thank the JUSTICE/AJC working party on reforming benefits decision-making for supporting the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Sechi led on the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey with support from Creutzfeldt and other members of the AJC panels. The results were published as a AJC report: https://ajc-justice.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Digitisation.pdf

2. JUSTICE, reforming benefits decision-making, https://justice.org.uk/our-work/civil-justice-system/current-work-civil-justice-system/reforming-benefits-decision-making/

3. A more detailed analysis of the survey will be available in a forthcoming report ‘Welfare benefit advice provision during the pandemic’ to be produced by JUSTICE/AJC. It will be available on the AJC website: https://ajc-justice.co.uk/council/reports/

5. For an overview of the effects of LASPO on civil legal aid in Wales: https://dev.publiclawproject.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/LASPOA_briefing_Wales.pdf

7. The survey was sent out to the same contacts the Digitisation Welfare Advice Survey was sent out to across England and Wales: Citizens Advice, Law Centres, ASA, Advice UK members. They were asked to forward the survey to their networks.

9. A typology sets itself apart from a taxonomy by not having a hierarchy and items not being mutually exclusive.

References

- ‘Getting it right in social welfare law’ the low commissions follow up report, 2015. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.lowcommission.org.uk/.

- Advice Service Alliance, 2020. Advising Londoners: an evaluation of the provision of social welfare advice across London, Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://asauk.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Advising-Londoners-Report-30072020-1.pdf.

- Advice UK, 2020. Guidance and resources for advice services and organisations COVID-19. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.adviceuk.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/AdviceUK-Coronavirus-Briefing-20200602.pdf.

- Balmer, N., et al., 2012. Just a phone call away: is telephone advice enough? Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 34 (1), 63–85. doi:10.1080/09649069.2012.675465.

- Baring Foundation, 2013. Social welfare legal advice and early action. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://baringfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/STVSEA9.pdf.

- Brown, K., Ecclestone, K., and Emmel, N., 2017. The many faces of vulnerability. Social Policy and Society, 16 (3), 497–510. ISSN 1474-7464. doi:10.1017/S1474746416000610.

- Buck, A., Pleasence, P., and Balmer, N., 2008. Do Citizens know how to deal with legal issues? Some empirical insights. Journal of Social Policy, 37 (4), 661–681. doi:10.1017/S0047279408002262.

- Burton, M., 2018. Justice on the line? A comparison of telephone and face-to-face advice in social welfare legal aid. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 40 (2), 195–215. doi:10.1080/09649069.2018.1444444.

- Byrom, N., Beardon, S., and Kendrick, A., 2020. The impact of COVID-19 measures on the civil justice system. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CJC-Rapid-Review-Final-Report-f.pdf.

- Citizens Advice, 2020a. Citizens advice coronavirus data report. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/Covd-19%20Data%20trends/Data%20report%20-%20August%202020.pdf.

- Citizens Advice, October 2020b. Getting Support to those who need it: how to improve consumer support in essential services. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/Energy/Final%20-%20modernising%20consumer%20support%20in%20essential%20markets.pdf.

- Cookson, G. and Mould, F., 2014. The business case for social welfare advice services: an evidence review – lay summary, legal action now: low commission evidence review. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiIqrTg4M_tAhX7TRUIHUIyCQgQFjAAegQIARAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.lag.org.uk%2F%3Ffileid%3D-17039&usg=AOvVaw1MFWjrzVhaS4TgiCIBNF33.

- Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2018. The impact of LASPO on routes to justice. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/the-impact-of-laspo-on-routes-to-justice-september-2018.pdf.

- Ewick, P. and Silbely, S., 1998. The common place of law: stories from everyday life. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Fabian Policy Report, 2017. ‘The right to justice;’ the final report of the bach commission. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://fabians.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Bach-Commission_Right-to-Justice-Report-WEB-2.pdf.

- Frenk, J., 1992. The concept and measurement of accessibility. In: K.L. White, et al., eds. Health services research: an anthology. Washington: Pan American Health Organization, 858–864.

- Genn, H., 1999. Paths to Justice: what people do and think about going to law. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- George, R., 2019. Matters of welfare and matters of law. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 41 (3), 358–361. doi:10.1080/09649069.2019.1628429.

- Gordon, F., Mant, J., and Newman, D., 2020. Is technology the answer to addressing the legal needs of vulnerable social groups during the COVID-19 pandemic? Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://infolawcentre.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2020/11/11/is-technology-the-answer-to-addressing-the-legal-needs-of-vulnerable-social-groups-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-faith-gordon-jess-mant-and-daniel-newman/?subscribe=success#blog_subscription-3.

- Hatch, J., 2002. Typological analysis. Doing qualitative research in education settings. Aelbany: State University of New York Press, 152–161.

- HM Courts & Tribunals Service Reform Update Summer, 2019. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/806959/HMCTS_Reform_Update_Summer_19.pdf.

- ISPOS MORI, 2017. Analysis of the potential effects of early legal advice/intervention. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/en/topics/research/research-on-the-benefits-of-early-professional-legal-advice.

- JUSTICE, 2018. Preventing digital exclusion from online justice. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://justice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Preventing-Digital-Exclusion-from-Online-Justice.pdf.

- JUSTICE/AJC, forthcoming. Welfare benefit advice provision during the pandemic. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://ajc-justice.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Advice-pandemic-report-final.pdf https://ajc-justice.co.uk/council/reports/.

- Law Centres Network, 2020. Law for all: the 50th anniversary campaign for law centres. London: Law Centres Network. Available from: https://www.lawcentres.org.uk/asset/download/981. https://ajc-justice.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Advice-pandemic-report-final.pdf

- Law Society, 2019. Legal aid deserts. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.lawsociety.org.uk/campaigns/legal-aid-deserts.

- LEF, 2019. Digital Justice: HMCTS data strategy and delivering access to justice report and recommendation, Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://research.thelegaleducationfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/DigitalJusticeFINAL.pdf.

- Levesque, J.-F., Harris, M.F., and Russell, G., 2013. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12 (1), 18. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-12-18.

- Low Income Tax Reform Group, 2012. Digital exclusion. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.litrg.org.uk/sites/default/files/digital_exclusion_-_litrg_report.pdf.

- Maclean, M. and Eekelaar, J., 2019. After the act: access to family justice after LASPO. Oxford: Hart.

- McKeever, G., Simpson, M., and Fitzpatrock, C., 2018. Destitution and paths to justice. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://research.thelegaleducationfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Destitution-Report-Final-Full-.pdf.

- MoJ, 2016. Transforming our justice system. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/553261/joint-vision-statement.pdf.

- MoJ, 2019. Legal Support: The way ahead. An action plan to deliver better support to people experiencing legal problems. Accessed on 24 April 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/777036/legal-support-the-way-ahead.pdf.

- Morris, D. 2013. The impact of legal aid cuts on advice-giving charities in liverpool: first results. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Impact-of-Legal-Aid-Cuts-on-Advice-Giving-in-Morris/31af59762f5cac9b549f3b032eed1ce0fd8a5e90?p2df.

- Organ, J. and Sigafoos, J., 2018. The Impact of LASPO on routes to justice. Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report 18. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/the-impact-of-laspo-on-routes-to-justice-september-2018.pdf.

- Pleasence, P. and Balmer, N., 2014. How people resolve ‘legal’ problems. London: Legal Services Board.

- Sechi, D., 2020. Digitisation and accessing justice in the community. London: Administrative and Justice Council. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from https://ajc-justice.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Digitisation.pdf.

- Selita, F., 2019. Improving access to justice: community-based solutions. Asian Journal of Legal Education, 6 (1–2), 83–90. doi:10.1177/2322005819855863.

- Sommerlad, H. and Sanderson, P., 2013. Social justice on the margins: the future of the not for profit sector as providers of legal advice in England and Wales. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 35 (3), 305327. doi:10.1080/09649069.2013.802108.

- Stuart, A. and Browne, J., 2013. Do the UK government’s welfare reforms make work pay, IFS Working Papers, No. W13/26. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

- Tarr, A. and Finn, D., 2012. Implementing universal credit: will the reforms improve the service for users? London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion.

- Toh, A., 2019. The disastrous roll-out of the UK’s digital welfare system is harming those most in need. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/10/disastrous-roll-out-uks-digital-welfare-system-harming-those-most-need.

- Tomlinson, J., 2020. Justice in the digital state. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/25109.

- Transforming our justice system: summary of reforms and consultation ‘legal aid, sentencing and punishment of offenders act’, 2012. Accessed on 24th April 2021. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/10/contents/enacted.

- Trinder, L. and Hunter, R., 2015. Access to Justice? Litigants in person before and after LASPO. The Family in Law, 45, 535–541..

- Woodhead, C., et al., 2017. Impact of co-located welfare advice in healthcare settings: prospective quasi-experimental controlled study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 211 (6), 388–395. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.117.202713.

![Figure 8. Conceptual framework of access to advice [during the pandemic] for providers and users](/cms/asset/765d85e8-e94d-470d-b7c1-41327d8764ff/rjsf_a_1917707_f0008_oc.jpg)