Abstract

‘High-quality talk’ is a fundamental principle of many approaches to teaching grammar. However, relatively few studies have attempted to characterize this talk with attention to the ways in which classroom dialogue might engender metalinguistic thinking. This paper explores how the concepts of procedural and declarative metalinguistic knowledge may be applied to classroom discourse in order to identify the problems and potentials of grammatical ‘Metatalk’. The data is drawn from observations of functionally-oriented grammar lessons in 17 classrooms across England. This opportunity sample was drawn from the intervention group of a randomized control trial, all of whom were working within a pedagogical model which embeds attention to grammar as a resource for meaning-making within the teaching of writing. Given the impact of effective teacher-student dialogue on student learning, studies such as this are valuable for illuminating how classroom talk operates within the teaching of grammar for writing. The findings particularly reveal the role of teacher-guided talk during collaborative writing activities in facilitating bi-directional transfer between declarative and procedural metalinguistic knowledge.

Introduction

There is long-standing debate about the value of explicitly teaching grammar to first-language speakers. Such controversy is often characterized as Anglophone: the US, Australia and the UK have seen curriculum developments in the past 20 years which have placed greater emphasis on the teaching and learning of grammar (e.g. Hancock & Kolln, Citation2010; Hodgson, Citation2017; Macken-Horarik et al., Citation2015; Schleppegrell, Citation2007). However, the issue reaches into a variety of international contexts, including the Netherlands (Coppen et al., Citation2019), Spain (Fontich & Camps, Citation2014), and Norway (Tonne & Sakshaug, Citation2007). At the root of arguments around the value of teaching grammar to L1 learners is disagreement regarding the relationship between explicit knowledge of grammatical structures or terminology, and the ability to speak, read and write effectively. If students develop facility with language implicitly through exposure and practice, there may be little benefit to spending curriculum time developing explicit knowledge of forms, and indeed time spent on this may be to the detriment of other aspects of learning to read and write (Wyse & Torgerson, Citation2017). Conversely, the view that explicit teaching can facilitate students’ understanding of how language can be shaped for impact, and support their ability to use language powerfully, is also strongly asserted (Chen & Myhill, Citation2016; Fontich & Camps, Citation2014; Love & Sandiford, Citation2016). The content of explicit teaching is a further issue: whether students need a technical metalanguage to reflect on language use, or whether ‘everyday’ language is sufficiently reflexive (Galloway et al., Citation2015); which models of grammar best support understanding of writing (Macken-Horarik, Citation2012); and how grammar should be ‘contextualised’ in the teaching of writing (Myhill et al., Citation2012).

In the midst of these debates, a growing body of research has begun to investigate how explicit grammar teaching might support reading and writing. Studies have particularly focused on teacher orientations to grammar (e.g. Bell, Citation2016; Safford, Citation2016; Watson, Citation2015a, Citation2015b), teacher subject knowledge (e.g. Jones & Chen, Citation2012; Macken-Horarik et al., Citation2018), and dialogue (Fontich, Citation2014; Jesson et al., Citation2016; Watson & Newman, Citation2017). There is still limited empirical evidence of what might constitute an effective pedagogy for grammar, and particularly how explicit knowledge about language might transfer into the act of text production. However, research is beginning to show how attention to linguistic forms can be interwoven through the teaching of reading and writing in a way which develops students’ understanding of textual crafting (Macken-Horarik et al., Citation2015; Myhill et al., Citation2012).

Analyses of the metalinguistic knowledge of students who are learning L1 grammar have been relatively more rare, particularly for children who are past the earliest stages of language development. These have drawn on numerous constructs. The explicit/implicit or explicit/tacit duallisms are commonly cited (e.g. Chen & Myhill, Citation2016; Fontich & Camps, Citation2014; Hulstijn, Citation2015; Myhill et al., Citation2016), as is the distinction between declarative and procedural knowledge (e.g. Fontich, Citation2016; Myhill, Citation2005). Fontich (Citation2016), in particular, asserts that the relationship between procedural and declarative knowledge in metalinguistic activity is under-investigated, especially within the context of writing rather than knowledge of grammar per se. This study aims to contribute to this issue by exploring how aspects of procedural and declarative knowledge might be elicited and mediated through classroom talk.

Metalinguistic knowledge

While the learning of L1 speech may be primarily instinctual and experiential (Hulstijn & De Graaff, Citation1994), transforming speech to written text requires an additional degree of abstraction, which creates high cognitive demand. From a Vygotskian perspective, writing requires both spontaneous concepts (developed through experience in everyday life) and scientific concepts (developed in the acquisition of a systematic body of knowledge, through formal instruction): this is elaborated by Jesson et al. (Citation2016) who suggest that writing instruction requires teachers to combine ‘procedural knowledge and scientific concepts’ (p. 158), with attention to the relationship between the two. Knowledge about language is therefore often conceptualised through duallisms such as tacit/explicit, implicit/explicit, conscious/unconscious and declarative/procedural.

As Berry (Citation2005) explains, most knowledge about language possessed by L1 speakers is ‘implicit’ – we communicate meaningfully without having to consciously think about the rules or conventions that govern our language use. ‘Explicit’ knowledge, on the other hand, can be defined in multiple ways: as any conscious reflection on language, or as knowledge that has been gained through ‘formal processes’ (p. 12), or the particular knowledge of a formal metalanguage. In this study, we use ‘explicit’ in the broadest sense, to refer to any conscious knowledge.

While binaries are necessarily reductive, the concepts of ‘declarative’ and ‘procedural’ knowledge may be particularly helpful for exploring how explicit knowledge about grammar might transfer into improvements in students’ writing. Fontich identifies ‘a gap between procedural and declarative knowledge, and a lack of capacity to establish links between them on the part of both teachers and students’ (Citation2016, p. 243). Yet despite this, some studies have reported a relationship between explicit grammatical instruction and improvement in student writing outcomes as measured by standardised tests (Jones et al., Citation2013). The gap, essentially concerned with the difference between what students can say about grammar and what students can do in their writing, is clearly ripe for exploration. In this study, we explore how classroom talk demonstrates and mediates declarative and procedural knowledge as students learn about grammar for writing, particularly to understand how the ‘gap’ identified by Fontich (Citation2016) might be bridged through dialogue.

Declarative and procedural knowledge

The concepts of procedural and declarative knowledge are well-rehearsed in the fields of both L1 and L2 language acquisition. There is not, however, a single, widely-agreed definition of each. It is generally held that declarative knowledge is knowledge which can be made explicit, conscious and articulable (e.g. Ullman, Citation2005; Woolfolk et al., Citation2008). Declarative metalinguistic knowledge might therefore be evident in any reflexive comment on language. Such comments might exist with or without metalinguistic terminology; as Culioli (Citation1990) notes, we can distinguish between metalinguistic activity which is verbalized in everyday language, and that which is organized into systematic formal models and assigned technical terminology. Within a grammar for writing lesson, comments might demonstrate knowledge of grammatical forms (‘Quickly is an adverb’), and/or knowledge of the effects that these might have on a reader (‘Putting “quickly” first makes us feel stressed’).

In this study, we operationalise declarative knowledge as knowledge which is conscious, explicit and verbalized. Because metalinguistic terminology is part of the lesson content, we are interested in how this metalanguage might mediate talk about writing, and therefore particularly examine use of grammatical terminology. As Berry asserts, metalinguistic terminology ‘may be enabling (or disabling), an aid (or a barrier) to learning itself’ (Citation1997, p. 136). However, we recognize that grammatical terminology is not a prerequisite for declarative knowledge about grammar, which might, for example, be shown in a student’s ability to identify patterns of language or discuss the impact of a particular word or phrase without technical vocabulary (see also Berry, Citation2005). This knowledge is observed, in our study, through student and teacher talk about text.

Procedural knowledge is more difficult to define. Again, there is general agreement that procedural knowledge is associated with being implicit, tacit, unconscious and non-articulable (e.g. Ullman, Citation2005; Woolfolk et al., Citation2008), but it is also widely posited that procedural knowledge can be conscious and can be explicit. Camps and Milian (Citation1999), for example, suggest that procedural knowledge may be non-verbalisable but conscious when students have awareness of aspects of their writing which they cannot fully explain. This view is supported by Chen and Jones (2012), who found that young writers were conscious of choices they were making in their writing but found it difficult to articulate them.

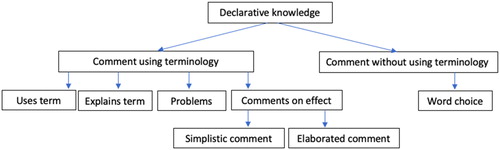

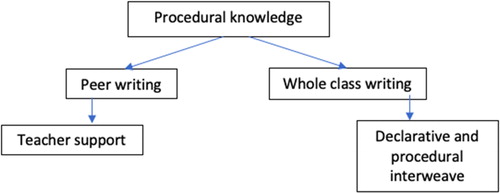

For the purposes of this study, we have separated the conscious and unconscious dimensions of procedural knowledge, in line with Culioli (Citation1990). Unconscious procedural knowledge can be defined as epilinguistic: automated and non-verbalisable, an unconscious manifestation ‘of the rules of the organization or use of language’ (Gombert, Citation1992, p. 13). Conscious procedural knowledge can be defined as metalinguistic, involving conscious reflection or monitoring (ibid). When a student selects a particular word, phrase or form for a particular purpose, they are engaging in metalinguistic procedural activity, drawing on their understanding of how form affects meaning in order to shape their writing with an intention in mind. Because of our focus on classroom talk, we examine metalinguistic procedural knowledge which can be observed in moments of oral composition, when students verbalise the different choices available to them as they compose or revise texts. In keeping with Fontich and Camps (Citation2014), it is the process of deliberation which we see as an indicator of conscious decision-making and hence metalinguistic activity, rather than the epilinguistic ‘intuitive’ and ‘automatic’ application of grammatical knowledge in the creation of texts (Gombert, Citation1992, p. 579). In this article we examine the interplay of declarative and procedural metalinguistic knowledge (operationalised in below) in classroom talk. Further research might usefully take this a step further by examining how the talk relates to samples of student writing.

Table 1. Theorisation of declarative and procedural metalinguistic knowledge.

Grammar as a resource for meaning-making

This study is situated within the pedagogical approach defined by Myhill (Citation2018), which takes a meaning-orientated stance, positioning linguistic knowledge as a semiotic resource. This view of language is influenced by the functional-orientation of Halliday and Matthiessen (Citation2013), concerned with grammar in use ‘related to the study of texts, and responsive to social purposes’ (Carter, Citation1990, p. 104). The aim of teaching grammar is not to develop declarative knowledge of linguistic rules or forms, but rather to make transparent the ways in which language can be shaped for impact, and to develop students’ ability to consciously craft their writing. In common with ‘rhetorical’ approaches to grammar, it foregrounds writing as a social practice (Kolln & Gray, Citation2016), asserting that an approach which ‘helps developing writers to understand how their language choices shape the interaction between authorial intention and the intended reader and gain control of their linguistic decision-making’ is ultimately ‘empowering’ (Myhill, Citation2019, p. 57). The grammatical content is aligned to the demands of the UK curriculum, which requires children to learn traditional terminology and to identify word classes, phrases, clauses and some sentence types, as well as syntactic categories such as ‘subject’ and ‘object’ (Department for Education (DfE), Citation2013). However, the pedagogical principles contextualise this knowledge within the teaching of writing, so that learning objectives are driven by rhetorical aims. The ultimate goal is to support students in developing a wide repertoire of forms and an ability to use these with intent, drawing on their understanding of the impact that their choices may have on a reader. The key pedagogical principles are outlined in the Research Design below, and the theoretical orientation of the approach is explained in detail in Myhill (Citation2018).

Metatalk

The concept of ‘metatalk’ as talk that encodes metalinguistic reflection on language use is familiar from L2 research (e.g. Swain, Citation1998). Within that field it is usually form-focused, but L1 grammar research has expanded this to include talk which explores the relationship between form and meaning, and particularly the impact of grammatical choices. This talk is an important pedagogical tool, allowing teachers to model metalinguistic thinking, to guide the co-construction of metalinguistic reflection, and to assess students’ understanding of writing and language (Newman & Watson, Citation2020).

The concept of ‘high quality’ pedagogical talk in general is an area of ongoing research; Howe et al. have recently highlighted the fact that there is relatively little evidence for how particular features of talk might be ‘productive in practice as well as in theory’ (2019, p. 4). Our understanding of metatalk is founded on conceptions of exploratory and dialogic talk (Alexander, Citation2008; Mercer & Littleton, Citation2007), and particularly the concept of ‘repertoire’ to refer to teachers’ strategic use of different types of talk to meet different goals (Kim & Wilkinson, Citation2019). The grammar for writing pedagogy requires teachers to implement a range of talk strategies aligned to those identified by Howe et al. as characteristic of effective classroom dialogue, including asking open questions, inviting extended student contributions and exploring differences of opinion. In progressing towards the ultimate aim of moving students from a ‘writer-based to reader-based’ approach to writing (Myhill, Citation2019, p. 57), teachers might use talk for a wide range of purposes. These might include clarifying declarative understanding of grammatical forms, developing students’ sensitivity to the range of meanings that particular words or constructions might convey, or supporting students’ ability to articulate their writing intentions. We are interested in how different types of talk might align with these intentions, and particularly in identifying where particular types of talk might support transfer between declarative and procedural knowledge.

Metatalk places high demands on teachers. It requires them to have confidence not only in analysing grammatical forms, but also in explaining the effects they create, and in scaffolding and extending students’ ability to articulate this (Boyd, Citation2015; Newman & Watson, Citation2020). The data explored in this study inevitably captured difficulties associated with classroom talk about grammar. Our intention in sharing these is to acknowledge the complexity of teaching writing, and to highlight common pitfalls in order to help practitioners to avoid them, rather than to present a deficit view of teaching.

Research design

The data for this study was collected alongside an experimental trial funded by the Education Endowment Foundation, Choice and Control in Writing. We observed seventeen classes in fifteen schools, with 10–11 year old students in their final year of primary school. All classes were part of the intervention group, and consequently were following the same unit of work. This focused on writing fictional narratives, with attention to salient grammatical features interwoven throughout.

The teachers in each class attended three training days where they were introduced to the principle of functionally-oriented grammar teaching as developed by Myhill et al. (Citation2012), and particularly to four pedagogical principles which form the acronym LEAD explained in .

Table 2. LEAD principles from the grammar for writing pedagogy.

The classes were an opportunity sample from schools in London, the South West and the North East of England. Most were mixed ability, though in one school we observed top, middle and bottom sets. All classes were mixed gender and were in schools with a high proportion of socioeconomically disadvantaged students. In each lesson, we used three audio recorders: one to capture whole class talk, and two positioned to capture pair or group talk. A written lesson observation record was also created to supplement the recordings.

It was evident from the lesson observations that teacher confidence and ability to enact the pedagogy varied considerably. Teachers used their own professional judgement to amend lesson plans and materials, and this sometimes involved episodes of form-focused teaching. The episodes discussed in the findings below exemplify a range of orientations to grammar, not all of which are aligned perfectly to the underpinning rhetorical and functional approach of the intervention. However, our aim was to explore how talk was functioning within a range of real classrooms, so we did not exclude any data on this basis.

The data comprised audio capture of 17 lessons of approximately one hour each. This was transcribed by the researchers and coded in NVIVO. Coding captured episodes of conversation – exchanges between teacher/student or student/student in which grammar was mentioned or discussed (declarative knowledge), or put into practice through oral composition of text (procedural knowledge), or both. This involved an iterative process in which two researchers collaborated to create, test and refine the application of the coding framework. Initial exploration of the data involved reading and discussing transcripts as a research team. Episodes were then coded deductively as demonstrating either procedural or declarative knowledge, with declarative knowledge then separated into comments with and without formal metalinguistic terminology. Coded transcripts were cross-checked and agreement was reached about the coding. At this point, the research team discussed what would be useful sub-categories to explore, and this generated the full coding structure shown in and . Again, coders worked discursively and collaboratively, manually agreeing how the final framework was applied to each transcript.

With regards to the theoretical concepts outlined above, we note that our data captures only an external representation of internal cognition. Our definitions of declarative and procedural knowledge are designed to enable us to explore some of the different ways in which students demonstrate metalinguistic knowledge within an ecologically-valid learning environment, but we can only analyse the visible. When we infer metalinguistic procedural knowledge from students’ oral composition, we cannot know whether equivalent declarative knowledge is active but unspoken. Nevertheless, we believe that the findings suggest the value of conceptualising students’ understanding in these terms, as it allows us to explore how teachers can use talk to move between explicit declarative discussion and procedural application of knowledge.

Findings and discussion

Declarative knowledge: students’ use of grammatical terminology

As noted earlier, declarative knowledge does not demand the use of formal terminology. However, we were particularly interested in how grammatical metalanguage was used by teachers and students, and whether this appeared to facilitate discussion about the rhetorical impact of texts. In just over half of the lessons, we observed students using grammatical metalanguage, and this terminology was always relevant to the scheme of work (see ). This may appear low; however, a number of lessons were dominated by quiet writing activities, and students often responded to teacher use of terminology – for example, by offering opinions on the effect of different constructions – without using metalanguage themselves. Each reference represents a conversational episode within a lesson. In most cases this was a session of teacher-led whole class talk, but occasionally it includes one to one teacher-student or student-student discussion. Of the 25 episodes which included student use of terminology, 15 came from just four observations, indicating that this was particularly characteristic of a small number of lessons, and these lessons also included more extended episodes of dialogue.

Table 3. Episodes in which students use grammatical terminology.

Frequency counts of student use of terminology () indicate that they are more confident using word level metalanguage than sentence level. While ‘noun phrase’ appears relatively high in frequency, it only appeared when elicited directly by the teacher. While it should be noted that the amount of student-student talk captured was significantly less than teacher-student, it is still noteworthy that students were only observed using a very limited range of terms when talking to each other.

Table 4. Frequency of grammatical terms in student talk.

Most occurrences were heavily elicited by the teacher, and were restricted to recap of terminology previously learned, word-class identification, or simplistic explanation of the effect of a particular grammatical form. These moments of elicitation were more often form-focused than functional in orientation. The following example is typical of the closed elicitation that dominated these episodes:

T. Ok, aggressive, what kind of word is aggressive? What word class is aggressive?

P. Mad

T. What word class is it, what type of word? Yes it is mad, seriously, but come on

P. Adjective

T. Adjective, so we’ve got an adjective.

However, there were a handful of occasions where the terminology did appear to genuinely facilitate discussion between teacher and student or student and student. For example, we saw confident use of terminology to clarify tasks,

P. Could we do some adjectives and nouns?

T. No. You’re asked for nouns and verbs

to give syntactic explanations for choices of punctuation,

T. If you would put a comma in, where and why?

P: I would put it before ‘that’, because ‘that’ is a relative clause

and to analyse texts,

P1: Well it can’t be adjective because if it was going to be an adjective then the adjective would be ‘giant’

P2: Eyes is not an adjective.

P1: I know. What I’m saying is, they can’t be adjectives because if they were adjectives, the only adjective there would be ‘giant’ and that wouldn’t make sense.

Again, the terminology in these examples is used in a form-focused context. However, these brief exchanges were usually embedded in lessons which did incorporate attention to impact elsewhere. There was just one example of students using terminology to explore their own writing choices in peer discussion:

P3. Never look at the beast’s eyes ‘cause they will turn to into ash.

P4. I think it looks better with an adjective in there like crimson.

Here we start to see the terminology being used to support transfer of declarative knowledge into application in writing, though evidence of this is very limited across the whole dataset (partly due to the limited quantity of peer discussion captured). This does provide a glimmer of insight into the potential that knowledge and use of metalanguage might have for enabling students to explore language choices in their own writing.

We also observed a few examples of students actively explaining terminology (), and here it was evident that students were often more confident in using the terms in conversation than they were in providing explanations. Definitions tended to be partial and reliant on rules of thumb or examples, for example, one student defined noun phrases as phrases which used ‘ed and ing words’, and another explained modal verbs as ‘maybe you don’t know and maybe you will’ and giving the examples ‘Could, will, might, or’ (the ‘or’ suggesting an awareness of conditionality but misconception about the nature of verbs).

There were also a minority of lessons in which students demonstrated difficulties with grammatical metalanguage, particularly the concept of abstract nouns (). This was largely related to students’ use of the inadequate ‘can you touch it’ rule of thumb (see also Watson & Newman, Citation2017). Teachers appeared to find these problems difficult to manage – for example, in the following exchange the teacher initially responds to the student’s fixation on the ‘touch it’ rule, when the root of the problem is the misconception that ‘imprisoned’ is any type of noun:

P. Imprisoned?

T. Imprisoned, no that wouldn’t work as an abstract noun, no.

P. But you can’t feel it being in prison.

T. You can’t no, but it’s not, it has to be um something that you can’t touch, ok it’s got to be a noun, yeah?

Such exchanges highlight the importance of teacher’s linguistic subject knowledge for managing classroom metatalk. Teachers must negotiate the twin pedagogic challenges of analysing the grammatical underpinnings of a student response (‘imprisoned’ is a verb not a noun) and of deducing the implicit reasoning behind the response (they are focusing on ‘touch’ without considering ‘noun-ness’). As Boyd (Citation2015) notes in her discussion of the challenges of managing dialogic talk, both of these must be handled within the constraints of the rapid exchange of classroom talk.

Overall, the data suggest that students are likely to use grammatical terminology in conversation before they can confidently define the terms. They may be able to identify ‘adjectives’ and ‘verbs’ and even to talk with accuracy about how they use them in their writing before they can explain what they are. There are also some indications of the value of explicit use of terminology for facilitating precise talk about linguistic choices, though the evidence for this being embedded in student-student talk is very limited.

Extending form-focused declarative knowledge through exploratory talk

We observed one lesson where students engaged in an extended peer discussion of word class and noun phrases. This was not an expectation of the scheme of work, which placed emphasis on student talk about effects and impact rather than grammatical analysis per se. However, the teacher in this class chose to adapt the lesson to include two form-focused pair talk activities: the first requiring students to identify the word class of a group of nouns selected from a passage, and the second to identify the noun phrases around those head nouns.

Students had been reading an extract from Michael Morpurgo’s Arthur High King of Britain and were asked to identify the word class of selected words from a descriptive passage. Our observations captured two paired conversations, extracts from which are below:

A: you could say the ‘giant’, the ‘giant house’, you could say the ‘giant’ as the noun, like the ‘giant rooms’

B: I bet, I bet they’re nouns. ‘Eyes’ you can touch, ‘giant’ you can touch, ‘war horse’ you can touch, ‘clatter’ you can touch.

A: You can’t touch a clatter

B: It’s an abstract noun, it’s an abstract noun then. Clatter is an abstract noun!

****

C: Giant is definitely a noun. ‘Clattering’ is describing the horses’ movement…hooves clattering, that’s describing the horses’ hooves, so it would be an adjective. But that wouldn’t work. A giant man…that means, actually those two are both describing it as an adjective

D: And the war horse, it’s saying like, a horse – that’s a horse that’s supposed to be in the war.

C: ‘Towering’? Yeah, that’s describing.

D: Yeah, that’s describing the horse.

C: But ‘eyes’…that can’t be describing. Wolfish eyes. If it was ‘wolfish’. Actually it is kind of because…because it could say just wolfish.

In both of these pairs we can see students grappling productively with the task, applying their declarative knowledge (not always correctly). Students’ spontaneous reasoning activities here involve rephrasing, trying the words in different contexts, comparison, omission, considering how the target words relate to other words in the extract, and using the non-technical (and here misleading) ‘can you touch it’ rule for abstract nouns. There is evidence of some misconceptions, particularly when students consider the words out of context rather than focusing on syntax (see also Myhill, Citation2000; Watson & Newman, Citation2017). There is, however, an emergent understanding that syntactic relationships between words define their word class, particularly demonstrated when students try pairing words in different ways. It is possible that the focus on semantic categories (abstract vs concrete nouns) may be hindering focus on these syntactic dimensions. The misconceptions here indicate the importance of teacher intervention to reinforce correct understandings, and that is indeed what occurred in the following episode of whole class discussion, where the teacher called on students to explain their reasoning:

T1. Ok, so clatter is a noun. And what else helps us to decide that it was a noun. What’s in front of that word? The? The clatter. What’s it got?

P4. A determiner

T1. It’s got a determiner. It’s introducing the noun.

T: Now, let’s move on the ‘giant’, and there was some debate about this one. A ‘giant of a man’. And still in my mind this one’s quite unclear but I’d like you to help me validate it.

P: Some people might say the ‘giant’ is describing the man, but ‘A giant’…it’s saying that the man is a giant. So it would be a noun.

T: Ok, I’m impressed that you’re thinking about this because you can have giant in a different way, can’t you. You can have a physical giant, like Jack in the Beanstalk. Or, you could have the giant boy as an adjective, but in the case, they are using it as a noun. They’re being very sneaky, that’s Michael Morpurgo for you.

It is worth noting how skillfully the teacher orchestrates this task: she positions herself as co-explorer with the students; she highlights the syntactic position of clatter in relation to the determiner (another example of the technical metalanguage facilitating talk about writing); she clarifies and develops the student’s explanation of why ‘giant’ is a noun by giving examples of how the word can be used differently, then ends with comment which suggests a playful attitude to writing. The value interweaving of exploratory and authoritative talk for developing declarative knowledge is clearly evident here.

Declarative and procedural knowledge: functionally-oriented talk

In the example of exploratory talk above, the focus on understanding grammatical features overrode opportunities to discuss the effect of the author’s choices. This section starts to examine talk which was more closely aligned with the grammar for writing pedagogy, in that its aim was primarily to support students in exploring the relationship between different features and the impact they might have on a reader. Across the lessons, we observed very different levels of sophistication in terms of student talk about effect and impact, depending on whether talk was generalised or referred to specific texts.

In a total of eleven lessons, student comments on language in use were observed (see ). Of these eleven, three lessons included only simplistic, superficial comments. Five lessons included more extended, sophisticated comments by students (two of which also included examples of simplistic commentary). Four lessons included an episode in which language was discussed with no student or teacher use of grammatical metalanguage.

Table 5. Student comments on impact and effect of linguistic choices.

The simplistic comments were often generated in response to generalised teacher questioning, usually at the start of a lesson in a recap of prior learning. These occasions often tended to reify the relationship between form and function – something also seen in previous studies (Watson & Newman, Citation2017). The following example was typical:

T. You need to have compound, complex and simple sentences. Why would we use simple sentences?

S. When you’re like… to build up suspense

T. Yes, to build up suspense and tension in your story.

There is an element of genre appropriacy here with an association between simple sentences and suspense (though there may be confusion between ‘simple’ and ‘short’). However, the meaningless instruction to include three different sentence types, ‘You need to have compound, complex and simple sentences’ conveys little sense of impact. These moments indicated the difficulty of summarising learning in this pedagogy – the need to ensure that learning points which may initially have been generated from contextual discussion do not calcify into formulae when they are abstracted into general principles – raising the question of whether general principles are appropriate at all when discussing linguistic features.

In contrast to the decontextualised or very broadly contextualised discussion of grammatical choices, when students were talking about specific examples many teachers demonstrated great skill in using open questioning to develop students’ responses. Such episodes were, however, not strongly represented across the sample (). They occurred in contexts where teachers and students discussed the mentor texts, teacher-written texts and student-written texts, and were underpinned by the principle of linking reading and writing – inviting students to respond as readers as well as writers – and by a strong understanding that being a writer involves making revisions. From a theoretical perspective, these conversations were characterised by the interweaving of declarative and procedural knowledge.

This talk most often occurred in episodes of shared writing. Students were invited to suggest improvements to their own writing, that of their peers or even the teacher, and these contexts provided rich discussion of forms and effects. The passage below presents an episode in which a class experimented with rewriting a description originally written by the teacher, designed to lead into students’ independent writing:

T. Beautiful long thick flowing tail. What do you think? Beautiful long thick flowing tail.

P1. You need to describe the flowing tail like with a colour?

T. I think now looking at it I think I can see why that’s not great. Not great. S?

P2. It could have err, erm beautiful long flowing charcoal black tail.

T. Oh. That’s getting even more complicated isn’t it? What do you think F?

P3. I think you should cut down the adjectives.

T. I think so too. Sometimes, if you put too many adjectives you lose it a little bit. It becomes a little bit too prescriptive and a little bit. It’s almost you’re putting adjectives there for the sake of putting them there. So, can somebody, I want to say that its got a beautiful tail I want to say it’s long it’s thick it’s flowing. But I don’t want a list of adjectives followed by the noun. How can I turn that around?

P4. His river of a tail whipped his sides.

P5. Beautiful tail, long, thick and flowing.

T. Smashing, so. Anyone want to change anything else there? F?

P6. Beautiful rainbow tail was dancing in the breeze.

T. Can you see, so can you see that using the long list of adjectives doesn’t work as well as moving the adjectives around the noun, putting them after, adding extra detail, using the tail whipped, we’ve followed the noun with an E D verb haven’t we? That’s that non-finite clause? Ok, we could use a relative clause, flaring nostrils which created… so we’re trying to think about using these noun phrases in lots and lots of different ways, trying to make sure you pick an effective noun in the first place and then thinking around that noun, what can you do with it. Thinking about the verb that you are using. Whipped, D said his river of a tail whipped his beautiful sides. What does that conjure up? Whipped?

P7. Does it like um….

T. How is it different from waved? His tail waved against his side, his tail whipped against his side. A?

P7. Is it like he’s going quickly?

T. Yes, it gives us a sense of speed, doesn’t it? Urgency. F?

P8. Even though he’s beautiful he is strong, he’s like thrashing.

T. That’s right, it’s reminding you of that beauty and that strength. Good.

This episode demonstrates how some teachers were able to intertwine declarative and procedural knowledge in a way which fosters the transfer of declarative knowledge into writing. Students are invited to offer declarative comments on language use, ‘cut down the adjectives’ and to activate conscious procedural knowledge by offering alternative ways to write the phrase. Clearly, the declarative and procedural knowledge are enmeshed supportively (see Ullman, Citation2005). The teacher draws out and articulates the impact of students’ choices in order to support their conscious awareness of how their spoken phrases have impact, and students respond with both declarative explanations of choices and oral texts which demonstrate particular features for the teacher to discuss. Typical of these discussions, the teacher takes a lead in technically naming the changes that the students have suggested, while prompting the students to focus on the impact of syntactic and lexical choices. There is confident teacher subject knowledge which enables them to draw precise attention to the grammatical structures being discussed while also maintaining the focus on choice and effect. We argue that these episodes of shared writing appear to be particularly important pedagogical sites for supporting the transfer of declarative knowledge into procedural facility.

Procedural knowledge: students exploring writing choices in peer talk

Two observations included episodes of peer writing which allowed us to capture student talk about their writing as they composed together. Here, we could examine the procedural knowledge demonstrated in their exploration of linguistic choices. This was sometimes accompanied by declarative comments relating to decision-making and impact, but often remained implicit in their oral rehearsal of different words and phrases. In the following example, students had been exploring the impact of subject-verb inversion and delaying the subject in the context of a passage describing ‘The Lady of the Lake’ in Arthurian legend, and were now writing their own continuation passage.

P2. Suddenly turned sharply, suddenly turned sharply

P1. Turned sharply to look behind him

P2. I think, I think it should be into the darkness she went, under the water

P1. Yeah, but it’s got to be like swift and describe how she… so what was it, into

P2. Into the darkness she went. I just put into she

P1. Into the darkness she swiftly… we want to have it a lot of detail, she swiftly.

P2. I’m not doing your, I’m not putting swiftly.

P1. OK

P2. I just think it sounds better. I mean your sentence is a good sentence because it’s not got a lot of description, you don’t have to…

P1. So, into the darkness

P2. She went

P1. Under the water… Into the water… water… that doesn’t make sense, under the water and

P2. Into darkness she went, under the water and back to the hole she came out of

P1. Oh right

P2. What do you think climbed out of or crawled out of

P1. Crawled

P2. Into darkness she went, under the water and back to the hole she crawled out of

We can infer a range of knowledge here – particularly from the presence of the prepositional start which delays the subject in a similar pattern to the example they had explored earlier, but also their understanding that sometimes ‘less is more’, and perhaps that the pace of the sentence, or level of detail it contains, can reflect the speed of the scene they wish to create. P2, in particular, has a feel for the elegance of the sentence, rejecting the clumsy insertion of ‘swiftly’ suggested by P1, and this contrasts with P1’s less sophisticated focus on ‘lots of description’. The absence of grammatical terminology in their discussion does not hinder their writing as there is clearly a focus on purpose and effect- the consideration of what ‘sounds better’, that ‘it’s got to be like swift’ and the close attention to the word choices they can make. The process of articulating their choices acts as a metalinguistic prompt – they are required to bring ‘into consciousness… attention to language as an artifact’ (Myhill, Citation2011, p. 250) as they question the procedural decisions they make in their writing.

Conclusions

The grammar for writing pedagogy specifies ‘high-quality discussion’ as a key principle (). Analysis of these episodes suggests that a core component of this pedagogical talk is the interweaving of declarative and procedural knowledge. We observed teachers guiding conversations so that unconscious procedural knowledge is drawn into consciousness – moving student thinking from the epilinguistic to metalinguistic realm by inviting students to explore different linguistic choices, and enabling declarative thinking by scaffolding students’ articulation of the impact of these choices as well as their ability to use metalanguage to identify them. The use of shared writing may be particularly effective because it activates tacit procedural knowledge alongside explicit procedural and declarative knowledge – combining oral composition of text with explicit metatalk. The transfer of knowledge here is bi-directional – the teacher facilitates explicit reflection on students’ writing choices, and the students practice formulating texts procedurally which respond to the teachers’ instructions. In response to Fontich’s (Citation2016) concern that teachers and students struggle to transfer between declarative and procedural knowledge, we suggest that principles for functionally-orientated grammar teaching might therefore include contextualising declarative linguistic knowledge within procedural writing activities, and contextualising procedural experimentation with language within declarative talk about the impact of linguistic choices.

The analysis also reveals some of the different types of declarative knowledge that students demonstrate: we see evidence of their ability to use and respond to terminology in conversation but only very limited evidence of their ability to define or explain terminology, and this indicates that children are likely to develop propositional knowledge in the form ‘that is an adjective’ before ‘an adjective is a word that…’. For teachers, this is important, as it suggests that foregrounding terminology in use may be preferable to teaching students to state definitions. In this sense, the study mirrors similar findings that students may be able to deliberately use grammatical structures in their writing before they can describe or identify them (e.g. Camps & Milian, Citation1999; Chen & Jones, Citation2013): there may be a procedural element to the use of terminology whereby students are able to use the terms in reference to examples of language use before their ability to offer decontextualised declarative definitions is secure. We also argue that evidence for the use of terminology to support a functional understanding of grammar is still scant. Most of the terminology was used by teachers, and there was very limited evidence of students using terminology to explore writing choices rather than to analyse form. Further studies might gather more evidence of peer talk during joint writing activities in order to examine more closely the extent to which a formal metalanguage helps (or doesn’t help) students to discuss their writing.

Our analysis also revealed some familiar challenges with this pedagogical approach: the inadequacy of rules of thumb definitions (Watson & Newman, Citation2017); the tendency to use semantic rather than syntactic reasoning (Myhill, Citation2000), and the reification of relationships between form and function (e.g. Watson, Citation2015b). The demands on teacher knowledge are clearly high – particularly when they are confronted with student misconceptions. The teachers involved in this study are generalists – that is, they teach all subjects to their students, and are not necessarily English specialists. It is noteworthy, then, that despite the difficulties outlined above, there were many examples of knowledgeable and skillful pedagogical metatalk across the sample.

The categories of declarative and procedural knowledge have enabled us to identify how talk is particularly crucial in facilitating transfer between what students can say and what they can do in their writing. Given the impact of effective teacher-student dialogue on student learning (e.g. Howe et al., Citation2019), we believe that studies such as this provide valuable illumination of how classroom talk operates within a functionally-oriented grammar pedagogy.

Acknowledgements

This article draws on data collected for the Education Endowment Foundation Grammar for Writing study. The authors would particularly like to acknowledge the support of Debra Myhill, the project lead, as well as the anonymous reviewers and journal editors who helped to shape this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Annabel M. Watson

Dr Annabel Watson is a Senior Lecturer in Language Education at the University of Exeter, UK. Research interests focus on the teaching of writing – the role of metalinguistic knowledge in writing development, the teaching of grammar, and the development of students’ writing ability in relation to digital texts and technologies. She works extensively on initial teacher education programmes as well as teaching on Masters courses and supervising doctoral students. Prior to working at Exeter, she taught English and Media Studies in schools in Greater London and the South West.

Ruth M. C. Newman

Dr Ruth Newman is a Senior Lecturer in Language Education at the University of Exeter, UK. Her research interests focus on the role of talk in the teaching of language and literacy, including the role of dialogic metatalk in the development of metalinguistic understanding and writing. She is a member of the Centre for Research in Writing and teach primarily on the Secondary English PGCE programme and MA Language and Literacy. Before joining Exeter, she worked as a secondary English teacher.

Sharon D. Morgan

Dr Sharon Morgan is an Associate Tutor at the University of Exeter, UK. Before joining the Graduate School of Education in 2018, she spent 20 years working as an English teacher in schools in the South West, both in mainstream and alternative provisions. She now works across MA and Initial Teacher Education programmes. Her research interests centre on grammar teaching and the relationship between procedural and declarative metalinguistic knowledge. She is also interested in exploring links between literacy attainment and social disadvantage, the relationship between English/literacy attainment and learner identity (including impact of classroom groupings), gender inequalities and the discourse of underachieving boys, and non-traditional students and writing in HE.

References

- Alexander, R. (2008). Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk (4th ed.). Dialogos.

- Bell, H. (2016). Teacher knowledge and beliefs about grammar: A case study of an English primary school. English in Education, 50(2), 148–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/eie.12100

- Berry, R. (1997). Teachers’ awareness of learners’ knowledge: The case of metalinguistic terminology. Language Awareness, 6(2-3), 136–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.1997.9959923

- Berry, R. (2005). Making the most of metalanguage. Language Awareness, 14(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410508668817

- Boyd, M. P. (2015). Relations between teacher questioning and student talk in one elementary ELL classroom. Journal of Literacy Research, 47(3), 370–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X16632451

- Camps, A., & Milian, M. (Eds.) (1999). Metalinguistic activity in learning to write. Amsterdam University Press.

- Carter, R. (Ed.) (1990). Knowledge about language and the curriculum: The LINC reader. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Chen, H., & Jones, P. (2013). Understanding metalinguistic development in beginning writers: A functional perspective. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Professional Practice, 9(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1558/japl.v9i1.81

- Chen, H., & Myhill, D. (2016). Children talking about writing: Investigating metalinguistic understanding. Linguistics and Education, 35, 100–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2016.07.004

- Coppen, P. A. J. M., van Rijt, J. H. M., Wijnands, A., & Dielemans, R. C. (2019). Educational research on grammar education in the Netherlands. Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal-en Letterkunde, 135, 85–99. https://hdl.handle.net/2066/206

- Culioli, A. (1990). Pour une linguistique de l’énonciation: Opérations et représentations (Vol. 1). Editions Ophrys.

- Department for Education (DfE). (2013). English programmes of study: Key stages 1 and 2 National curriculum in England. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/335186/PRIMARY_national_curriculum_-_English_220714.pdf

- Fontich, X. (2014). Grammar and language reflection at school: Checking out the whats and the hows of grammar instruction. In T. Ribas, X. Fontich, & O. Guasch (Eds.), Grammar at school: Research on metalinguistic activity in language education (pp. 255–284). Peter Lang.

- Fontich, X. (2016). L1 grammar instruction and writing: Metalinguistic activity as a teaching and research focus. Language and Linguistics Compass, 10(5), 238–254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12273

- Fontich, X., & Camps, A. (2014). Towards a rationale for research into grammar teaching in schools. Research Papers in Education, 29(5), 598–625. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2013.813579

- Galloway, E. P., Stude, J., & Uccelli, P. (2015). Adolescents’ metalinguistic reflections on the academic register in speech and writing. Linguistics and Education, 31, 221–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2014.10.006

- Gombert, J. E. (1992). Metalinguistic development. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. (2013). Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Hancock, C., & Kolln, M. (2010). Blowin’in the wind: English grammar in United States schools. In T. Locke (Ed.), Beyond the grammar wars (pp. 31–47). Routledge.

- Hodgson, J. (2017). Affronted adverbials: The debate on grammar. Teaching English, (13), 57–62.

- Howe, C., Hennessy, S., Mercer, N., Vrikki, M., & Wheatley, L. (2019). Teacher–student dialogue during classroom teaching: Does it really impact on student outcomes? Journal of the Learning Sciences, 28(4-5), 462–512. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2019.1573730

- Hulstijn, J. H. (2015). Explaining phenomena of first and second language acquisition with the constructs of implicit and explicit learning. In P. Rebuschat (Ed.), Implicit and explicit learning of languages (pp. 25–46). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Hulstijn, J. H., & De Graaff, R. (1994). Under what conditions does explicit knowledge of a second language facilitate the acquisition of implicit knowledge? A research proposal. Aila Review, 11, 97–112. https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.428191

- Kim, M. Y., & Wilkinson, I. A. (2019). What is dialogic teaching? Constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing a pedagogy of classroom talk. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 21, 70–86 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.02.003.

- Kolln, M. J., & Gray, L. S. (2016). Rhetorical grammar: Grammatical choices, rhetorical effects (8th ed.). Pearson.

- Jesson, R., Fontich, X., & Myhill, D. (2016). Creating dialogic spaces: Talk as a mediational tool in becoming a writer. International Journal of Educational Research, 80, 155–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.08.002

- Jones, P. T., & Chen, H. (2012). Teachers’ knowledge about language: Issues of pedagogy and expertise. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 35(2), 147–172. https://ro.uow.edu.au/edupapers/1224

- Jones, S., Myhill, D., & Bailey, T. (2013). Grammar for writing? An investigation of the effects of contextualised grammar teaching on students’ writing. Reading and Writing, 26(8), 1241–1263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9416-1

- Love, K., & Sandiford, C. (2016). Teachers’ and students’ meta-reflections on writing choices: An Australian case study. International Journal of Educational Research, 80, 204–216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2016.06.001

- Macken-Horarik, M. (2012). Why school English needs a ‘good enough’grammatics (and not more grammar). Changing English, 19(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2012.680760

- Macken-Horarik, M., Sandiford, C., Love, K., & Unsworth, L. (2015). New ways of working ‘with grammar in mind’ in School English: Insights from systemic functional grammatics. Linguistics and Education, 31, 145–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2015.07.004

- Macken-Horarik, M., Love, K., & Horarik, S. (2018). Rethinking grammar in language arts: Insights from an Australian survey of teachers’ subject knowledge. Research in the Teaching of English, 52(3), 288–316. https://uoelibrary.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/rethinking-grammar-language-arts-insights/docview/2007454310/se-2?accountid=10792

- Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A socio-cultural approach. Routledge.

- Myhill, D. (2000). Misconceptions and difficulties in the acquisition of metalinguistic knowledge. Language and Education, 14(3), 151–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780008666787

- Myhill, D. (2005). Ways of knowing: Writing with grammar in mind. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 4(3), 77–96. http://education.waikato.ac.nz/research/files/etpc/2005v4n3art5.pd

- Myhill, D. (2011). The ordeal of deliberate choice: Metalinguistic development in secondary writers. In V. Berninger (Ed.) Past, present, and future contributions of cognitive writing research to cognitive psychology (pp. 247–274). Psychology Press.

- Myhill, D. (2018). Grammar as a meaning-making resource for improving writing. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 18, 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17239/L1ESLL-2018.18.04.04

- Myhill, D. (2019). Linguistic choice as empowerment: Teaching rhetorical decision-making in writing. Utbildning & Demokrati – Tidskrift för Didaktik och Utbildningspolitk, 28(2), 55–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.48059/uod.v28i2.1121

- Myhill, D., Jones, S., & Wilson, A. (2016). Writing conversations: Fostering metalinguistic discussion about writing. Research Papers in Education, 31(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1106694

- Myhill, D. A., Jones, S. M., Lines, H., & Watson, A. (2012). Re-thinking grammar: The impact of embedded grammar teaching on students’ writing and students’ metalinguistic understanding. Research Papers in Education, 27(2), 139–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2011.637640

- Newman, R., & Watson, A. (2020). Shaping spaces: Teachers’ orchestration of metatalk about written text. Linguistics and Education, 60, 100860. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2020.100860

- Safford, K. (2016). Teaching grammar and testing grammar in the English primary school: The impact on teachers and their teaching of the grammar element of the statutory test in spelling, punctuation and grammar (SPaG). Changing English, 23(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2015.1133766

- Schleppegrell, M. J. (2007). The meaning in grammar. Research in the Teaching of English, 42(1), 121–128.

- Swain, M. (1998). Focus on form through conscious reflection. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition (pp. 64–81). Cambridge University Press.

- Tonne, I. O., & Sakshaug, L. (2007). Grammar and developing writing skills – What does the British EPPI Review Study tell us? In S. Matre & T. L. Hoel (Eds.), Skrive for nåtid og framtid. Skriving i arbeidsliv og skole (pp. 167–179). Tapir Akademisk Forlag. http://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-54138

- Ullman, M. T. (2005). A cognitive neuroscience perspective on second language acquisition: The declarative/procedural model. In C. Sanz (Ed.), Mind and context in adult second language acquisition (pp. 141–178). Georgetown University Press.

- Watson, A. M. (2015a). Conceptualisations of ‘grammar teaching’: L1 English teachers’ beliefs about teaching grammar for writing. Language Awareness, 24(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2013.828736

- Watson, A. (2015b). The problem of grammar teaching: A case study of the relationship between a teacher’s beliefs and pedagogical practice. Language and Education, 29(4), 332–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2015.1016955

- Watson, A. M., & Newman, R. M. C. (2017). Talking grammatically: L1 adolescent metalinguistic reflection on writing. Language Awareness, 26(4), 381–398. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2017.1410554

- Woolfolk, A. E., Hoy, A. W., Hughes, M., & Walkup, V. (2008). Psychology in education. Pearson Education.

- Wyse, D., & Torgerson, C. (2017). Experimental trials and ‘what works?’in education: The case of grammar for writing. British Educational Research Journal, 43(6), 1019–1047. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3315