Abstract

This article contributes to a feminist geographic analysis of how urban food and health environments and non-communicable disease experience may be being constructed, and contested, by healthcare professionals (local elites) in two secondary Ugandan cities (Mbale and Mbarara). I use thematic and group interaction analysis of focus group data to explore material and discursive representations. Findings make explicit how healthcare professionals had a tendency to prescribe highly classed and gendered assumptions of bodies and behaviours in places and in daily practices. The work supports the discomfort some have felt concerning claims of an African nutrition transition, and is relevant to debates regarding double burden malnutrition. I argue that a feministic analysis, and an intersectional appreciation of people in places, is advantageous to food and health-related research and policy-making. Results uncover and deconstruct a dominant patriarchal tendency towards blaming women for obesity. Yet findings also exemplify the co-constructed and malleable nature of knowledge and understandings, and this offers encouragement.

Introduction

This article starts with the call of feminist geographers to bring the experiences of individuals and ‘the geographies of everyday life’ (Dowler and Sharp Citation2001, 171) to research, and to consider phenomena not only from a macro-level but also at the scale of the body, the household, the community (Dowler and Sharp Citation2001; McDowell Citation1999). Feminist geographers have explored how to take multiple and diverse viewpoints (Hiemstra and Billo Citation2017; McEwan Citation2001) into account and how to ground discourses ‘in practice (and in place)’ (Dowler and Sharp Citation2001, 171). Consideration of the ‘material conditions of everyday life’ (Preston and Ustundag Citation2005) and the intersectional (Valentine Citation2007) and multi-layered nature of people and places (Massey Citation2004) are necessary for nuanced understandings of material or discursive phenomena. In addition, feminist geographers have highlighted how representations of individuals and categorisations of classed, gendered, or otherwise prescribed bodies, ‘are constructed and reconstructed around political and patriarchal boundaries through discourses’ (Dowler and Sharp Citation2001, 173), playing out across interlinked scales. An aim of this article was to explore how I could contribute to such calls by conducting a feminist geographic interrogation of my Ugandan research material, and what such an approach might reveal. I thus explore material and discursive (re)presentations of the urban food and health environments, through focus groups discussions (FGD) with local healthcare professionals, in two cities: Mbarara and Mbale. The research question was twofold: how do healthcare professionals in these cities experience, understand and interpret the food and health environments of the people they support? Secondly, what factors, processes or behaviours, in their experience, may be influencing perceived changes in food and health circumstances? I was interested in how healthcare personnel represented such phenomena, and whom they described as being more, or less, affected. In addition, I explore their reactions to findings from a 2015 household survey in these cities, with which I was involved (Mackay et al. Citation2018). The survey depicted socio-economic and geographic inequalities in relation to diets, food security, and non-communicable disease (NCD) experience (such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity) that cast doubt on commonly assumed causal processes as espoused by nutrition transition theory (Popkin Citation2001).

Findings make explicit some (of likely many) localised discourses on identity and representation among healthcare professionals, regarding men and women’s bodies, behaviours, and food and health experiences within these Ugandan cities. Findings support the discomfort concerning claims of African nutrition transition (Riley and Dodson Citation2016), and are relevant to debates regarding double burden malnutrition (Shrimpton and Rokx Citation2013) and rising non-communicable disease (Swinburn Citation2013).

The article continues by outlining nutrition transition theory, and key components of a feminist analytical approach, before providing some Ugandan contextual background. I describe data collection and analysis under methodology, before discussing the results of applying a feminist geographic lens to the focus group data through thematic content and group interaction analysis. The article contributes to feminist scholarship on how food and health-related issues may be being constructed and contested in these Ugandan cities. I do not claim representativeness of all healthcare workers, nor of all secondary cities. Findings are time and place-specific. Nevertheless, insights revealed may be of some relevance to other Sub-Saharan African communities experiencing similar food and health-related circumstances in similar socio-economic contexts.

Nutrition transition theory

There has been much recent discussion of nutrition transition theory, and the implications of urbanisation for food, health and livelihoods in cities, particularly those of Sub-Saharan Africa (Popkin, Adair, and Ng Citation2012; Swinburn Citation2013; Steyn and Mchiza Citation2014). The theory arises from the work of Barry Popkin and is informed by modernisation theory assumptions (Nhema and Zinyama Citation2016). Essentially it describes how as societies consolidate in more urban environments the systems of food production, distribution, and access evolve from more local, small-scale and unprocessed forms to food systems characterised by longer supply chains and more processed and industrial foods (Popkin (Citation1998, Citation2001)). Interrelated with such changes are assumed lifestyle and dietary transitions leaving people less physically active (farm less, work sedentary jobs in denser communities) with more diverse diets with higher animal fat and refined sugar content (ibid). Linked to, and usually taken to be a result of these nutritional, lifestyle and food system changes, are epidemiological changes where urban residents becomes less affected by undernutrition and infectious diseases and more affected by NCDs (ibid).

Uganda is generally described as a country at early stage food system transition (Haggblade et al. Citation2016), particularly outside the capital of Kampala. Additionally, the country is not highly urbanised country with just 23.8% urban (UN Citation2018) though future rapid growth, particularly in secondary cities, is anticipated (Satterthwaite, McGranahan, and Tacoli Citation2010; Schwartz et al. Citation2014). The country thus might not be expected to display advanced nutritional, food system and epidemiological transitions. Indeed previous research does suggest that nutritional and food system changes are not highly advanced in Mbale and Mbarara, yet NCD experience is already keenly apparent (Mackay et al. Citation2018). Other studies of NCD presence within Uganda also suggest that the claims of nutrition transition theory, especially regarding causes of epidemiologic change, require careful nuance and contextualisation (Kavishe Citation2015; STEPS Citation2014). Nutrition transition theory, and international agencies, tend to paint coherent images of change, but recent work recognises contextual, pyscho-social and city-specific influences of urban food and health environments and decision-making, and call for specificity (IFPRI Citation2017; FAO Citation2017) similar to the calls of feminist geographers outlined earlier.

Research approach: a feminist geographic lens

I interrogate nutrition transition theory, and my research material, from a ‘third wave’ (Moss Citation2002, 3) feminist geographic epistemology. Third wave feminism is concerned with social justice across a multiplicity of difference for both men and women, including income, race, class and ethnic grouping rather than exclusively focusing on a homogenised conceptualisation of ‘women’ as first-wave feminism did, or the more deconstructionist second wave feminism that recognised female differences such as black women, queer women, low-income women (for elaboration on evolving feminisms see Moss Citation2002, 2–3 and 21–24). Feminist geographers have applied themselves to ‘spatializing the constitution of identities, contextualizing meanings of places in relation to gender, and demonstrating how gender as a social construction intersects with other socially constructed categories within particular spatialities…’ (Moss Citation2002, 3). Geographers have also been concerned with the relevance of, and yet fluidity associated with, space (Massey Citation2004). Embodied and emplaced socio-spatial practices characterise both places and behaviours in specific and evolving ways (McDowell Citation1999). These socio-spatial practices are created and reproduced by ‘relations of power and exclusion’ (McDowell Citation1999, 4). My analysis reveals gendered and classed assumptions of bodies, behaviours, and embedded power structures, which make up the mutually constitutive (ibid) socio-spatial practice of people and place in Mbale and Mbarara.

A feministic analysis embraces intersectionality (Valentine Citation2007) as essential for a sophisticated understanding of how the multiple, sometimes conflicting, markers of a person’s position in their society such as age, religion, ethnic grouping, legal status, sexual preference, cultural background (Preston and Ustundag Citation2005), might enable or constrain their food and health situation. These factors affect an individual’s social location (McGibbon et al. Citation2014) which in turn influences that person’s interpretations of, and access to, material and pyscho-social underpinnings for life (ibid).

It is unwise to claim to use feminist approaches to topics including eating behaviours, body image and natural science classifications such as obesity without acknowledging the discomfort many feminists have had with such investigations and biological categorisations. There is a history of critique where the ‘impasse sits on an ontological and epistemological divide’ (Warin Citation2015, 50). Material feminism offers a bridge over this impasse as it tries to ‘register the inextricable entanglements of bodies in time and place, with histories, the socio-political and the material’ (Warin Citation2015, 52). I take this material feminist view which understands that obesity and other NCDs are not predetermined biological truths (as some natural science research might imply), but neither are they purely social constructions (as some feminists have proposed) (Warin Citation2015).

Ugandan gender relations and food and nutrition context

In 1995 the government of President Yoweri Museveni made a public commitment to women’s equal rights in the constitution (Mbire-Barungi Citation1999). There have been shifting discourses in Ugandan gender relations. The discourse of women’s rights as human rights is ‘refracting gender relations in new ways in Uganda, creating fault lines and tension that destabilize prevailing notions of male authority and men’s proper roles’ (Wyrod Citation2008, 801). Twenty years of government-led championing has had positive impact, claims Wyrod, describing a destabilising of ‘conventional notions of masculinity, opening up space for new formulations of African masculinities, both hegemonic and transgressive’ (Wyrod Citation2008, 818) but that for still too many ‘men’s authority within the home remains uncontestable’ (Wyrod Citation2008, 819). These representations of the masculine ideal of the ‘provider’, and of female dependency (Miller et al. Citation2011) are clearly depicted and hotly debated during my FGDs. Such depictions are not without contestation, with signs that younger men, in particular, may be resentful of expectations (Barratt, Mbonye, and Seeley Citation2012).

Emplacing nutrition transition claims

Mbale is located in the mountainous region towards the border with Kenya and the core urban area houses approximately 70,000 people. Mbarara is the administrative centre of the Western region located at a major road junction on the high plateau with approximately 90,000 population (see (Mackay et al. Citation2018) for more on the cities). My 2015 household survey collected data from 1000 households per city. Analysis led to the conclusion that there was, in these two cities at that time, uncertain evidence for advanced nutritional and food system transitions (Mackay et al. Citation2018). Yet the presence of NCDs–often claimed to be caused by changing food and nutritional systems–were clearly apparent (ibid). In addition, body mass index data was highly gendered with 60% of underweight adults being male and 83% of overweight/obese adults being female. Other studies have found such greater female obesity prevalence and high diabetes and hypertension burden (Schwartz et al. Citation2014; Maher et al. Citation2011). These findings complicate claims from nutrition transition regarding how such urbanisation, food and health transitions interlink (Mackay et al. Citation2018). An intention with the FGDs was to further explore these food and health circumstances from the healthcare professionals’ perspectives.

Methodology

Positioning

My research approach is constructivist: I recognise that my very presence in the social context that I am investigating, and how those I wish to interview perceive me, influences, and thus is a part of, the research process (Lincoln, Lynham, and Guba Citation2011). This is true of any type of research action but is perhaps especially clear when I as an obvious outsider (betrayed by my white colour, blue eyes, Scottish accent, body language, choice of attire) am researching in a Ugandan context. I am also female, and clearly perceived as that locally. I am a geographer, interviewing healthcare professionals about health and food. I was introduced to participants by my local collaborator as a PhD student in geography who had been working with issues surrounding health, food and farming in their cities since 2015. Thus I was not presented as a health expert, and I suspect that the denotation of ‘student’ perhaps put participants at ease more quickly than if I had been presented (or attempted to present myself) as an experienced healthcare professional. Overall, it is my feeling that my presence with this research was perceived with interest, politeness and engagement. My thoughts here attempt to highlight my positioning as researcher. This is clearly partial, written from my own perspectives, but nevertheless an essential part of attempting to work in a feministic manner (Mkandawire-Valhmu and Stevens Citation2007; Moss Citation2002).

Data collection

The cities were purposively chosen by counterparts at Makerere University as secondary (for the country's urban profile) and rapidly growing. The focus group discussions (FGD) took place in February and March 2017, one in each city. Healthcare professionals were key informants considering the diets, food environments, and health circumstances of the urban communities they served. Feminist geographers have written about the value of focus groups to geographic research (Pini Citation2002). This is particularly when exploring ‘meaning, identity, subjectivity, emotion, affect, politics, knowledge, power, performativity and representation’ (Longhurst Citation2003, 113) as this study aimed.

One FGD lasted one hour, the other 45 minutes. There were a total of eleven participants (seven in one city [three females, four males], four in the other [three females, one male]). A senior healthcare-related member of the Municipal Council had invited participants from their network of community clinics. They announced it as a voluntary opportunity, and, as such, a number of participants failed to show up, implying to me that they did not feel obligated. The aim was not for statistical representativeness of health workers nor city communities, but rather towards thick description (Holliday Citation2016). As well as viewing the FGDs as data, I agree that ‘the interactions that occur among the participants can yield important data’ (Onwuegbuzie et al. Citation2009, 2). I conducted the focus groups in English. This did not appear to be a problem since English is the national language of Uganda and all education is conducted in English and these were tertiary-educated individuals. Transcripts were audio recorded, with permission, and I later transcribed the recordings, yielding 35 pages of transcripts totalling 15,000 words. Immediately after an FGD I would write a field journal (occasionally discussing with my Ugandan colleague), recording my reflections, observations, the atmosphere, body language, questions that provoked humour, confusion or consternation (Moss Citation2002; Pini Citation2002). These journal notes comprise an additional 10-page data source important for analysis of group interaction.

FGD participants comprised five female ‘In-Charge Nurses’ (their positions titles, denoting senior ranking nurse manager of a local health clinic) in total (two in one FGD, three in the other). They ranged in age from an estimated 45-55 years. There were two (one per focus group) male medical doctors (one in his late 30s and one in his late 50s). In the larger focus group there was also one senior female health manager at the municipal council (est. age mid-50s) and a more junior male working in a similar capacity with health policy and inspections (est. late 20s). Finally, there were two more junior males (one a recent university graduate and another est. 30 years) who both worked in local clinics with health education and community outreach, and were both quite new in their jobs. The In-Charge nurses had many years experience dealing with patients (diagnostics, treatment) but were now also involved in clinic management. FGD participants also said they were involved in meetings with health planners and decision-makers and thus had some influence on policy-making. Those working in health planning were not involved in primary care. With these compositions one could suggest that I am ‘studying up’ (Hiemstra and Billo Citation2017) and dealing with elites (England in (Moss Citation2002)).

Data analysis

I first employed a thematic content analysis of discussion in response to questions on the food environment, diets and NCDs, and then I analyse the group interaction. I have changed names to preserve anonymity and I chose not to make explicit which data was from which city since these are small professional communities. I was the only person involved in analysis. Thematic content analysis entailed labelling (or coding) each text section, as close to the data as possible, to capture the main thrust. After this, I grouped similar pieces of data (same topic or making similar suggestions) to create broad categories. I then re-read the text, further reflecting on main points, and looking for more procedural or causal suggestions made by participants. Further sorting and reclassifying followed an abductive iterative exploratory process (Locke, Feldman, and Golden-Biddle Citation2015). This process led me to three overarching themes (see findings).

I then analysed the group dynamics and participant interaction, inspired by Onwuegbuzie et al. (Citation2009). They argue that considering the argumentation and dispute, the consensus built or not built, during FGDs provides crucial insights. The data that informed this interaction analysis of key players, which ideas came from whom, the overall atmosphere, comprise my field journal, my memories, discussion with my Ugandan colleague, the written transcripts and audio recordings (Pini Citation2002; Moss Citation2002). Analysis of the performativity (Longhurst Citation2003) and group interaction (Onwuegbuzie et al. Citation2009) within FGDs, is another source of data which enriches findings (Pini Citation2002).

Findings from thematic content analysis

In both FGDs participants started talking first about malnutrition, and communicable diseases (malaria, pneumonia). However, they noted declining case numbers with improved diagnostic abilities and vaccination programmes. Both FGDs thereafter described a growing trend towards non-communicable diseases, with obesity, hypertension and diabetes increasingly present (even in youth).

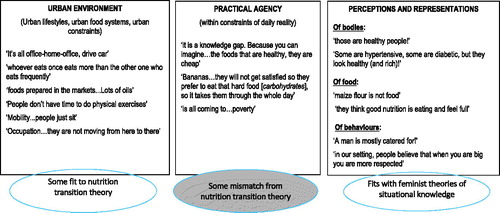

provides visual representation of the three major themes arising from my thematic content analysis, showing example quotes. The figure is not in any particular order, does not present consensus and is not a model, rather a descriptive presentation. I labelled the themes 1) Urban Environment, 2) Practical Agency, 3) Perceptions and Representations. Within urban environment were participants’ descriptions and reflections upon urban lifestyles, specificities of the urban food environment and some aspects of the constraints of urban life upon daily-lived experience. Theme 2, termed Practical Agency, describes the agency of urban residents to make decisions regarding their food and health environments within the parameters of the urban environment (as perceived by FGD participants). The third theme of Perceptions and Representations captures the depictions, claims and counter-claims made by the healthcare professionals of the urban communities that they serve. I have superimposed, in , my reflections of where views and experiences seem to accord with nutrition transition theory propositions, and highlight a key mismatch: that of practical agency, where people are forced to focus on lower diversity carbohydrate-dense diets due to practical needs for satiation within budgetary restrictions. The remainder of this section discusses these themes.

Influence of the urban environment

The claims of FGD participants regarding sedentary urban lifestyles, less physical jobs, more moving by car or motorcycle, greater use of oil for cooking and a lack of time for, or cultural interest in, physical exercise (see ) are quite in line with claims of nutrition transition theory (Popkin Citation2001). Some FGD participants did raise the idea of change over time, suggesting these factors as part of a transition from rural to urban ways:

Also … change in lifestyle … in those days people used to be feeding on these grains, erm, but nowadays chips and chicken …. They are not balancing the diet. A person is eating chicken or meat Monday to Sunday … thinking that that is good feeding. (Ebo, FGD, Uganda 2017)

The participants also talked about the food available within the urban environment, a growing tendency to consume cheap high-energy low nutritional value snacks, greater meat and more fried food consumption – another claim of nutrition transition thinkers:

Because there the majority of the people [working] in town … their condition is they eat from those restaurants where they prepare a certain type of foods hhmm? The macroni [as in pasta], fried meats, muchomo [stick of roasted meat] (Benjamin, FGD, Uganda 2017)

Yet the discussions on the daily lived reality of many in their communities, particularly regarding the topic of low dietary diversity (see following sections), somewhat contradict the tenets of nutrition transition. Before considering these in more detail however, it is necessary to note (and participants took time to discuss) that the concept of ‘food’ is not always understood in the same way in Uganda as in a Euro-American context:

Because, you know in Africa we have a lot of foods …. We tell them that, every food that you have in the household is important. Equally important. Don’t think that, when you have flour, maize flour, it’s not food …. (Margaret, FGD, Uganda 2017)

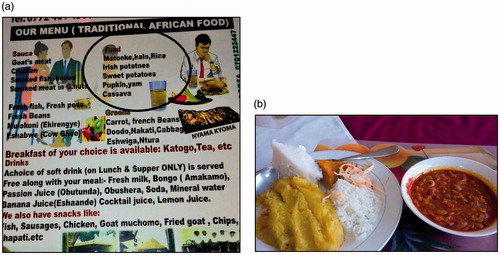

What Margaret is referring to is the common local understanding that ‘food’ refers only to the major staple food products, such as matooke (cooking bananas), potatoes, or cassava, but especially matooke. In a restaurant you might order chicken and they will ask you ‘And for food?’ meaning which of the major carbohydrates should accompany it (, circled). Restaurants commonly serve at least three different types of starchy carbohydrate per meal (). Thus posho (which can be made from maize flour, millet flour or cassava flour and is mixed with water into a mash) on its own, or with beans (one of the most common meals in these cities (Mackay et al. Citation2018) might not always be considered ‘food’. Such spatially and culturally-embedded thinking is critical for food-related researchers to understand (McDowell Citation1999; Nagar et al. Citation2002).

The focus groups further discussed carbohydrates; partly blaming them for rising NCDs (see also ):

Yeah we have a lot of carbohydrates! You go into families; you ask what they have to eat. You find people eat more of, of, carbohydrates, even children. Like a child feeds on potatoes, cassava. The proteins are not good. So, what happens is that you will find that people will grow fat because … their diet is not balanced (Rebecca, FGD, Uganda 2017).

Practical agency within the constraints of daily life

Urban food-related behaviour claims included the need for budget-balancing decisions that tended to sacrifice nutritional diversity for the feeling of fullness ( and ).

Table 1. Dietary diversity unaffordable.

Both FGDs described low dietary diversity as being very common, along with irregular eating patterns. As already noted, this factor that does not fit well with traditional conceptions of a nutrition transition. Charity says ‘We don’t have regular meals eh?’ and ‘the type of food also. You regularly eat and it is the same type eh. If it would be a different one. Like in the village you have fruits eh, milk…cassava…millet’ (Samuel, FGD Uganda 2017).

Urban residents were presented, in contrast to rural residents, as being less able to access a diversity of foodstuffs. The health workers propose (assume?) that rural residents are more easily able to access fruit, vegetables and a greater diversity of (more nutritious) carbohydrates because they farm such produce or live close to those who do. The poorest urban residents are less able to farm such produce or to purchase such produce in urban markets due to price and the budget-balancing requirements described earlier.

In addition, some of the In-Charge nurses described the daily reality that many of the mothers they meet face whereby they are often left home with the children without any food in the house to feed them and without any money: we deal directly with the women … they are aware [here she means women are aware about good nutrition and healthy eating] … they say ‘He left and he didn’t even leave us with anything!’ (Jasmine, FGD, Uganda 2017).

Here she is describing what they termed the irresponsible or uncaring man ( and ) where the man keeps money to himself and leaves for work in the morning without leaving any money for the women to provide for the family. How common this kind of man is, is of course not clear, but Jasmine and Amaka claimed they see this all the time and other research raise the issue of women’s burden and time constraints and male prioritisations (Tacoli Citation2012; Wyrod Citation2008; Miller et al. Citation2011; Mbire-Barungi Citation1999).

Would you like your maize boiled, mashed or fried?

Continuing within this theme of practical agency within the constraints of daily life limiting dietary diversity, as one FGD participant stated so succinctly: ‘You boil, you mash, you fry, but it’s all maize’. Diversity simply came from how it was cooked. Quite some time in the focus groups revolved around these claims of a low dietary diversity, and reasons for this. As I highlighted in , this is an area that fits less neatly with transitional thinkers’ supposition that as societies urbanise their diets become more diverse, higher in fat and protein, more processed (Popkin, Adair, and Ng Citation2012). The common claim that obesity is rising due to ‘increased consumption of foods that are high in energy, fats, added sugars or salt, and an inadequate intake of fruits, vegetables and dietary fibre’ (FAO Citation2017, 81) as a result of urbanisation, processed foods, and less active lifestyles, does not resonate with FGD claims nor with my earlier survey and later interviews. These food system/nutritional transitions are claimed causes of epidemiological transition towards NCDs. Yet urban residents of Mbale and Mbarara were predominantly eating maize, matooke and beans with little vegetable and fruit consumption (FGDs and (Mackay et al. Citation2018)). The reason for such low dietary diversity was largely, according to FGDs, daily uncertainty and financial limitations ( and ). Obesity in these cities, I suggest, is rather another expression of malnutrition, increasingly recognised as such (Popkin, Adair, and Ng Citation2012). The health workers discussed at some length the financial cost-benefit evaluation urban residents may consider: they described the need to get maximum feeling of fullness for minimal expenditure (see and ). This area of starchy carbohydrate consumption, along with its quality, processing (Mattei et al. Citation2015), how it is cooked, as well as portion sizes and frequency of eating (both mentioned by FGDs) are also pertinent areas of research (for example (Gissing et al. Citation2017)). As urban areas develop diets may well improve in diversity as theory proposes (Popkin, Adair, and Ng Citation2012), but the discussions of Mbale and Mbarara’s healthcare professionals imply that income and urban development do not always correlate, nor do they necessarily translate into linear improvements in food and health systems, as research in urban Malawi also highlights (Riley and Dodson Citation2016).

Perceptions and representations

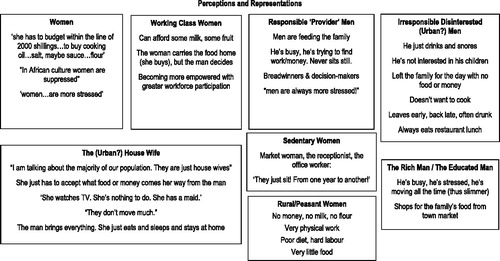

The third theme, labelled Perceptions and Representations, is my conceptualisation of what was going on when FGD participants talked about different types of people, for example, the ‘urban man’, ‘housewife’, ‘rural woman’. For the large textual elements in this category I tried to assess who was being described, and what they were doing or not doing, according to focus group participants, keeping the overall research question in mind. reveals and explores these different categories of people represented by the healthcare professionals. It does not present consensus, nor depict causal mechanisms, but rather overviews the kind of claims presented and contested by the health workers. There is overlap here with the previous two themes of urban environment and practical agency.

There was the greatest debate (accompanied by much laughter and teasing), and greatest lack of consensus around whether men were largely the ‘provider’ (Wyrod Citation2008) or the ‘irresponsible, disinterested’, and around the depiction of the housewife. shows parts of this debate, and the strongly classed and gendered views put forward: the women generally saying the men were irresponsible, the men generally claiming that women were lazy and expectant.

Table 2. Gendered and classed people.

examines more closely the repeatedly heard claims, in both FGDs, about the housewife. This persona was put forward as a reason for why women in Sub-Saharan Africa are being more affected by obesity than men (Ziraba, Fotso, and Ochako Citation2009). The ‘housewife’ was presented as a particular new modern woman associated with urbanisation in the minds of some of the FGD participants. She has a maid; she is idle; she just eats and gets fat; were some of the claims ( and ). A rural women was never described as being ‘just a housewife’ throughout the FGDs. She does very physical work–by this, participants’ meant that she digs and hoes and plants in the garden/rural farm ().

Table 3. The urban housewife.

Yet a number of the women in the FGDs strongly contested this image of an idle urban housewife. The one-dimensional disempowered representation of the urban housewife also did not find much purchasing power in my subsequent fieldwork Mackay, Citation2019 (forthcoming) nor in wider research (Kinyanjui Citation2014, Tacoli Citation2012). Many stay-at-home women, in reality, engage in a number of practices to bring food or cash (field notes, unpublished data). Indeed, one of the participants (in a separate interview) noted that when she had been running community workshops most women (when asked about their occupation) first said they were housewives. When further probed, almost all engaged in informal activities, including sewing, washing clothes for others, farming, selling clothes, cooking food for sale (unpublished interviews). The socio-economic and demographic realities of the urban Ugandan context afford very few women the luxury of being an idle housewife (FGD, and field notes). These findings, and the obvious scepticism of the female In-Charge nurses in , leads me to be cautious about (predominantly, though not entirely, male) claims of passive, sedentary women without agency.

Findings from group interaction analysis

My analysis of the participant interaction in the focus groups suggests that people generally felt comfortable. They were able to debate with each other and there was a good degree of lack of consensus. Humour was used liberally in disagreeing. There were periods when I just listened as participants discussed and joked, slapped hands and heartily disagreed. This happened in particular when rather provocative claims regarding women’s bodies and behaviours were made.

Many of the participants knew each other, though I did not feel this was a hindrance to discussion. I felt that FGDs, were deemed rather enjoyable. This was certainly in evidence from about midway when the atmosphere became quite expansive with much humorous debate. The local council participants seemed more comfortable with theoretical/policy type questions rather than discussing experiences of people on-the-ground. Those who worked clinically were more confident in their assertions of community experiences.

In one of the cities there were two men (roughly in their late 30s) who played an important ‘provocateur’ role. They voiced highly gender-stereotyped, somewhat naïve and (many might consider) patronising or offensive, views of women in relation to food, eating behaviours, and health. Their views also seemed somewhat divorced of the realities of lived experiences that I found during fieldwork, and what I observed of Mbale and Mbarara life. They seemed to conceive of women in a one-dimensional way as simply stay-at-home, do-nothing-housewives. This despite being in a group comprising largely career women. Those few women that did work, they said, tended to ‘just sit’ (). Such claims provoked Justine and Amaka in particular, who began to challenge them (with good-natured laughter from all sides). The men took this well, and during the course of discussion, I felt I saw the men recognise they were guilty of strong generalisations, and they began to defer more to the grounded experience of these experience In-Charge nurses. At this point Robert admits ‘So we don’t know. We are guessing!’ (FGD, Uganda, 2017). It was also clear that these men were younger, were less experienced at service provision, being largely office-based. The concerning thing is that these two men were either in positions of some managerial authority over clinic managers (such as Jasmine and Amaka), and/or were educated to a postgraduate level.

There was not quite the same energetic debate in the second FGD, partly because there was no one making such controversial claims. However, there was definitely hot debate around the issue of why obesity in particular may be affecting women at a higher level than men, without clear consensus. These FGD participants also made similar claims about the stay-at-home housewife who did nothing but eat, and were also quick to put blame on women (Warin Citation2015) saying ‘Women can eat too much!’, (Charity, FGD Uganda 2017). There was a lack of awareness among healthcare professionals of the double burden of malnutrition (Shrimpton and Rokx Citation2013) and of research which suggests a link between in-utero/early childhood undernutrition and later-in-life obesity (Barker Citation1997; Caballero Citation2005; Popkin, Adair, and Ng Citation2012; Swinburn Citation2013). There are socially and biologically gendered differences which leave females significantly more likely than males to manifest childhood malnourishment with later adulthood obesity (Case and Menendez Citation2009). Here we see the materiality of the body making itself heard–a conceptualisation in keeping with the material feminist perspective that I described under Research Approach. Work such as this highlights the importance of gendered understandings of food and nutrition-related socio-spatial practices (McDowell Citation1999; Preston and Ustundag Citation2005).

Considerations and implications

Co-construction and creative destruction

The analysis of both the content and the group-interaction in these focus groups shows clearly, in my view, a lack of intersectional (Valentine Citation2007) thinking by health professionals. An intersectional analysis tries to make discrimination and hidden power relations visible (ibid). The findings in this article clearly show FGD participants constructing identities (the housewife, the provider man), obscuring power relations and failing to recognise the embedded specificity of the patriarchal hetero-normal (Hovorka Citation2012) of the social context. Yet at the same time, I think the debate among the participants, the revelation of assumptions, and the breakdown of these, also reveals the creative co-constructed nature of our depictions of ourselves and of others (Holliday Citation2016).

The obvious enjoyment participants had in the discussion, and the sense that some participants (such as Robert) had recognised their uni-dimensional characterisations, and admitted that daily life comprised a greater level of fluidity and complexity (McDowell Citation1999; Massey Citation2004) was empowering. In this sense then, the FGDs may have had an emancipatory effect, as Pini (Citation2002) found. The FGDs may have facilitated a creative destruction of uncritical assumptions and a co-creation of something more nuanced, grounded and emplaced, and a recognition of socially-differentiated power geometries (Massey Citation2004) between people and place, bodies and behaviours. Indeed three different participants said afterwards that they had found it interesting and had appreciated the discussion (field notes). This was not an intention of the FGD per se, but rather something I see as a positive unplanned consequence (Pini Citation2002). The topic of greater female obesity prevalence prompted energetic and contested discussions around gender roles, who was more stressed in the average household (generally, the men saying the men, the women saying the women), who was more responsible, who worked most, who ate most, who moved around more. It is my feeling that humour was deliberately used as a tool of contestation, to soften the impact of critique or disagreement. This seemed to be a productive strategy given how the more provocative claimants adjusted their position.

Normalcy, patriarchy, maternity

An overall assumption apparent in the FGDs, and it permeates all themes, is that of the nuclear family always living together under the same roof. There was no talk of households where someone worked in a distant city (which I came across more than once during fieldwork), nor of the youth, of single-parent families (comprising 30% of Ugandan see Mackay (Citation2019 forthcoming) households (UBoS Citation2016), of extended family households (13% Mbarara, 33% Mbale (Mackay et al. Citation2018)). There is an underlying assumption of the nuclear family. This is another example of the normalcy of patriarchy (Hovorka Citation2012; Dowler and Sharp Citation2001), and the commonplace assumptions associated with concepts such as ‘household’ or ‘family’ (McDowell Citation1999).

Of interest when reflecting on the discussions, is also what was not contained. Obvious in its absence is the lack of discussion of the fact that it is women who bear the children (relevant to female obesity). This is clearly associated with weight-gain in any time-space, and with possible difficulty losing that weight after. An additional unmentioned point is that of family planning. I was given the impression (by five or six people in subsequent interviews) that women in Uganda generally take responsibility for family-planning and that this commonly involves contraceptive pills or hormonal injections (field notes) and that these cause weight gain. This anecdotal evidence however goes somewhat against the widespread discourse of disempowered women regarding family planning (for example (Ghanotakis Citation2017)). It is not an aim of this research to investigate family planning but I mention it here precisely because it came up during subsequent fieldwork as a contributing factor to female-weight gain, yet its absence from the FGDs is striking, particularly given these were healthcare professionals. This overlooking of the female reproductive role (McDowell Citation1999) is an area requiring further investigation.

The power and positioning of health workers

Uganda’s public healthcare provision has evolved from being one of the best in Africa during the 1960s, through decline, scarcity and corruption in the 80s, to revitalisation and successful public-private partnerships since the 1990s (Streefland Citation2005). Some have suggested that prevalent healthcare regimes in Uganda remain entrenched in discourses of power (McEwan Citation2001, Veronese, Prati, and Castiglioni Citation2011) and highlight continuing colonial influences prejudicing education systems: ‘Nursing knowledge continues to be grounded in Western biomedical hegemony and its philosophical premises in positivism’ (McGibbon et al. Citation2014, 184). I write of these concerns because such may be influencing the structures and training, thus the power and positioning, of the Ugandan healthcare professionals in my FGDs. These professionals were representatives of their local and national healthcare systems. Yet it is impossible to disentangle how much of their considerations were presented from this position of civil servants and healthcare professionals, or how much they spoke simply as educated individuals puzzling about patterns, processes and behaviours within the communities they both serve and yet were also part of. Are they reproducing Foucauldian hegemonic discourses of power (Müller Citation2008), or reductionist individualised ‘healthy-lifestyle-choice’ (McGibbon et al. Citation2014, 188) assumptions which fail to acknowledge structural determinants of health? Structural concerns socio-economic, political, ethical influences on a society and how these interact with disease discourses of illness and health (McGibbon et al. Citation2014). Health workers are positioned within wider care systems. Identifying and deconstructing the attitudes and understandings of health workers is thus likely to help refute neo-colonial ideas/approaches that may further embed health inequalities (Mkandawire-Valhmu and Stevens Citation2007). Such analysis, towards which this article makes a contribution, is an integral part of decolonising healthcare regimes (McGibbon et al. Citation2014; McEwan Citation2001).

Value of a feminist geographic lens

The findings in this article reveal the prevalence of strong, sometimes unconscious, gendered and classed assumptions and stereotypes, among educated healthcare professionals. There was a tendency to make blanket generalisations and not well problematise claims or categorisations (the stay-at-home housewife, the peasant, the working class, ). A feminist analysis tries to reveal and disrupt notions of such a ‘homogenous category’ (Brah and Phoenix Citation2004, 82), whether that is of women or men, of the poor, the rich. It is also a reminder that, just with femininity, ‘masculinity is neither homogenous as a concept nor in terms of its impacts’ (Sharp Citation2007, 386). My FGD data certainly reveals such homogenising thinking but also shows some disrupting of such designations through humour and contestation (see ).

While not advocating to ignore materiality, a material feminist analytical approach recognises the importance of socio-cultural-political implications of concepts, such as food, work, femininity, masculinity (Nagar et al. Citation2002). My data reveals and explores such varied local cultural and political meanings, for example that ‘when you are big you are more respected’ (), or the assumptions around provider man or the suppressed woman (). What was also apparent in the initial discussions surrounding overweight was that even healthcare professionals first assumed this to be a sign of health and wealth. After further probing an ‘aha’ moment ran almost visibly around the room (field journal). I understood this to signify that participants realised they had been making assumptions. This in itself is quite revealing of local healthcare knowledge and discourse (McGibbon et al. Citation2014; Dowler and Sharp Citation2001) and is likely spatially and culturally constituted (Massaro and Williams Citation2013). It is also a clear example of the co-constructed nature of inquiry (Holliday Citation2016).

In the spirit of feminist geographic analysis, this study has uncovered some of the implicit assumptions about gender, class or other dimensions of difference in the context of Mbale and Mbarara at this time. These interact in varied and personalised ways to influence the structuring ‘of thought, of knowledge itself’ (McDowell Citation1999, 13). A feminist approach investigates the manner in which power operates as a ‘way that links the discursive aspects of identity and representation to the lived realities of individuals and community’ (Massaro and Williams Citation2013, 569). In these Ugandan cities we see focus group participants making claims of the limited spatial range and social value of ‘women’ and ‘housewives’ ( and ) who stay home doing nothing, as an example of McDowell (Citation1999) and Massey’s (2004) mutually constitutive and relational socio-spatial practices. ‘Men’, ‘providers’, the ‘rich man’ and even ‘irresponsible disinterested men’ are assumed to have a wider spatial reach, and to shoulder the burden of care, stress and accumulation () in order to fend for dependents (), that is, women, children, elderly (Barratt, Mbonye, and Seeley Citation2012; Wyrod Citation2008; Miller et al. Citation2011).

The claims made about women’s behaviour in relation to food and eating practices: ‘they eat the best bits’, they ‘eat too much’, or they ‘may eat a bone on the plate’ while ‘the man is catered for’ (FGD transcript, Uganda 2017) are provocative. Such assertions chime with findings from Riley and Dodson (Citation2016) who describe intimate interactions between gendered and spatialised urban identities and varying Malawian food cultures and traditions. The claim that women’s spatial relation to the urban environment is more circumscribed than men’s, centred around home, or market () is also not new (Riley and Dodson Citation2014). The positioning of men’s disregard for the care of the family and their poor health seeking behaviours (FGD transcript, Uganda 2017) are also examples of gendered constructions. Such propositions within these FGDs make apparent a partial view (Hiemstra and Billo Citation2017) of some of the ways that gendered assumptions structure thoughts around food, bodies, health (McDowell Citation1999) in these two Ugandan towns.

An intriguing aspect of the propositions of the FGDs was the implicit suggestion that the idle dependent housewife, and the irresponsible, disinterested man ( and and ) were particular new creatures of the urban environment–a socio-spatial creation of the daily material conditions of the city (Massaro and Williams Citation2013; Moss Citation2002; McDowell Citation1999). Health professionals suggest that these lazy creatures would be unable to exist in the harsh lived reality of Ugandan rural contexts. My data does not allow further investigation of these ‘new’ urban beings in the Mbale/Mbarara context–how common or uncommon they are, whether more fictive or more real. Future work could further investigate this representation of such supposed new and specifically urban Ugandan men and women.

Conclusions

Reflecting on my findings, I found myself wondering whether policymakers would share the tendency to think in the uni-dimensional way so vividly depicted in the focus groups. If so, how might this influence how policy is designed? To bring it closer, for whom might a policy to stem a growing burden of non-communicable disease in urban Uganda be designed? Is it for the (largely fictional?) not-working, not-moving, just eating, expectant housewife, or is an intervention designed with intersectionality in mind? To my mind, a policy targeted at one-dimensional representations of who is at risk and why, are likely to fail.

In this article I have used a feminist geographic lens to analyse the constitution and contestation of the knowledge, understandings and discourses of healthcare professionals regarding the food environment and material health-related issues in urban Uganda. I have tried to show how such a lens, and an intersectional appreciation of people in places, may be advantageous to food and health-related research and policy-making. Findings from both a thematic content and a group-interaction analysis make explicit how groups of healthcare professionals in these two intermediate-sized cities (Mbale and Mbarara), had a tendency to assign highly classed and gendered assumptions of bodies and behaviours. This permeated down to such mundane topics as who does the food shopping, and what (and how often/how much/in what form) people ate. The work uncovers and deconstructs a dominant patriarchal tendency towards ‘gendered and classed discourses of blame’ (Warin Citation2015, 54) towards women and mothers, particularly regarding obesity. I sought to interrogate, embody and emplace these understandings, and the macro-rhetoric of nutrition transition, in the ‘everyday lives of real people’ (Massaro and Williams Citation2013, 567) in line with calls from feminist geographers.

The feminist geographic lens I apply reflects the hallmarks of a feminist approach, being concerned with interrogating power relations, geographic scales, a suspicion of binaries, a preference for relational analysis and a grounded contextual understanding (Nagar et al. Citation2002; Massey Citation2004). Some of the healthcare professionals’ representations of ‘passive women and places’ (Nagar et al. Citation2002) are created by spatialised discourses and in turn further perpetuate such representations. Some of the focus group participants clearly wished to depict women (very especially urban housewives) as passive. Yet these same individuals also showed willingness to reassess some of their everyday unproblematised assumptions and I found this encouraging, as, I believe, did the participants.

Notes on contributor

Heather Mackay is a PhD Candidate at the Department of Geography, Umeå University, Sweden. Heather is a geographer working at the intersection of agriculture, food, and health in Africa. She completed her bachelors in Geography at Aberdeen University, Scotland. She has a Masters degree in Rural Resources and Environmental Management from Imperial College London, and a Masters in Spatial Planning and Development from Umeå University, Sweden. Her doctoral research investigates in what ways transitions at the nexus of urbanisation, food environments, and health are occurring in secondary cities of Uganda.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my colleagues Aina Tollefsen, Magnus Jirström and Marco Eimermann for taking the time to comment on an earlier draft of this article. I am also grateful to Belinda Dodson, Department of Geography, Western University, Canada for her guidance and encouragement. Thank you to Prof. Frank Mugagga, Department of Geography, GeoInformatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University for being the most incredible fieldwork facilitator and ensuring that I always had the best field support. Thank you also to the Municipal Councils of Mbale and Mbarara for their interest in this research, and to Joe Odori for support in fieldwork, transcription and debate. It is with humility that I especially thank all the focus group participants for their engagement and interest.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barker, David JP. 1997. “Maternal Nutrition, Fetal Nutrition, and Disease in Later Life.” Nutrition 13 (9): 807–13.

- Barratt, Caroline, Martin Mbonye, and Janet Seeley. 2012. “Between Town and Country: Shifting Identity and Migrant Youth in Uganda.” The Journal of modern African studies 50 (02): 201–23. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X1200002X.

- Brah, Avtar, and Ann Phoenix. 2004. “Ain’t I A Woman? Revisiting Intersectionality.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 5 (3): 75–86.

- Caballero, Benjamin. 2005. “A Nutrition Paradox—Underweight and Obesity in Developing Countries.” New England Journal of Medicine 352 (15): 1514–16.

- Case, Anne, and Alicia Menendez. 2009. “Sex Differences in Obesity Rates in Poor Countries: Evidence from South Africa.” Economics & Human Biology 7 (3): 271–82.

- Dowler, Lorraine, and Joanne Sharp. 2001. “A Feminist Geopolitics?” Space and Polity 5 (3): 165–76. doi: 10.1080/13562570120104382.

- FAO. 2017. “The Future of Food And Agriculture. Trends and Challenges.” In Annual Report. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation.

- Ghanotakis, Elena, Theresa Hoke, Rose Wilcher, Samuel Field, Sarah Mercer, Emily A. Bobrow, Mary Namubiru, et al. 2017. “Evaluation of a Male Engagement Intervention to Transform Gender Norms and Improve Family Planning and HIV Service Uptake in Kabale, Uganda.” Global Public Health 12 (10): 1297–314.

- Gissing, Stefanie C., Rebecca Pradeilles, Hibbah A. Osei-Kwasi, Emmanuel Cohen, and Michelle Holdsworth. 2017. “Drivers of Dietary Behaviours in Women Living in Urban Africa: A Systematic Mapping Review.” Public Health Nutrition 20 (12): 2104–13. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000970.

- Haggblade, Steven, G. Kwaku Duodu, D. John Kabasa, Amanda Minnaar, Nelson K. Ojijo, and R. N. John Taylor. 2016. “Emerging Early Actions to Bend the Curve in Sub-Saharan Africa’s Nutrition Transition.” Food Nutrition Bulletin 37 (2): 219–41. doi: 10.1177/0379572116637723.

- Hiemstra, Nancy, and Emily Billo. 2017. “Introduction to Focus Section: Feminist Research and Knowledge Production in Geography.” The Professional Geographer 69 (2): 284–290. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2016.1208103.

- Holliday, Adrian. 2016. Doing & Writing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hovorka, Alice J. 2012. “Women/Chickens vs. Men/Cattle: Insights on Gender–Species Intersectionality.” Geoforum 43 (4): 875–84. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.02.005.

- IFPRI. 2017. Global Food Policy Report. Washington D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Kavishe, Bazil, Samuel Biraro, Kathy Baisley, Fiona Vanobberghen, Saidi Kapiga, Paula Munderi, Liam Smeeth, et al. 2015. “High Prevalence of Hypertension and of Risk Factors for Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs): A Population Based Cross-Sectional Survey of NCDS and HIV Infection in Northwestern Tanzania and Southern Uganda.” BMC Medicine 13: 126.

- Kinyanjui, Mary Njeri. 2014. Women and the Informal Economy in Urban Africa: From the Margins to the Centre. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- Lincoln, Yvonna S., Susan A. Lynham, and Egon G. Guba. 2011. “Paradigmatic Controversies, Contradictions, and Emerging Confluences, Revisited.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonne S. Lincoln, 97–128. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Locke, Karen, Martha S. Feldman, and Karen Golden-Biddle. 2015. “Discovery, Validation, and Live Coding.” In Handbook of Qualitative Organizational Research. Innovation Pathways and Methods, edited by Kimberly D. Elsbach and Roderick M. Kramer, 371–380. New York: Routledge.

- Longhurst, Robyn. 2003. “Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Groups.” In Key Methods in Geography, edited by Nicholas Clifford, Meghan Cope, Thomas Gillespie, and Shaun French, 117–132. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Mackay, Heather, Frank Mugagga, Lydia Kakooza, and Linley Chiwona-Karltun. 2018. “Doing Things Their Way? Food, Farming and Health in Two Ugandan Cities.” Cities & Health 1–24.

- Mackay, Heather. 2019 forthcoming. Food Sources and Access Strategies in Ugandan Secondary Cities: An Intersectional Analysis. Environment and Urbanization.

- Maher, Dermot, Laban Waswa, Kathy Baisley, Alex Karabarinde, and Nigel Unwin. 2011. “Epidemiology of Hypertension in Low-Income Countries: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Survey in Rural Uganda.” Journal of Hypertension 29 (6): 1061–8.

- Massaro, Vanessa A, and Jill Williams. 2013. “Feminist Geopolitics.” Geography Compass 7 (8): 567–77. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12054.

- Massey, Doreen. 2004. “Geographies of Responsibility.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86 (1): 5–18. doi: 10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00150.x.

- Mattei, Joseimer, Vasanti Malik, Nicole Wedick, M., Frank Hu, B., Donna Spiegelman, Walter C. Willett, Hannia Campos, and Initiative Global Nutrition Epidemiologic Transition. 2015. “Reducing the Global Burden Of Type 2 Diabetes by Improving the Quality of Staple Foods: The Global Nutrition and Epidemiologic Transition Initiative.” Global Health 11: 23.

- Mbire-Barungi, B. 1999. “Ugandan Feminism: Political Rhetoric or Reality?” Women’s Studies International Forum 22 (4): 435–439. doi: 10.1016/S0277-5395(99)00037-0.

- McDowell, Linda. 1999. Gender, Identity and Place. Understanding Feminist Geographies. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers.

- McEwan, Cheryl. 2001. “Postcolonialism, Feminism and Development: Intersections and Dilemmas.” Progress in Development Studies 1 (2): 93–111. doi: 10.1177/146499340100100201.

- McGibbon, Elizabeth, Fhumulani M Mulaudzi, Paula Didham, Sylvia Barton, and Ann Sochan. 2014. “Toward Decolonizing Nursing: The Colonization of Nursing and Strategies for Increasing the Counter‐Narrative.” Nursing inquiry 21 (3): 179–191.

- Miller, Cari L., David R. Bangsberg, David M. Tuller, Jude Senkungu, Annet Kawuma, Edward A. Frongillo, and Sheri D. Weiser. 2011. “Food Insecurity and Sexual Risk in an HIV Endemic Community in Uganda.” AIDS and Behavior 15 (7): 1512–1519. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9693-0.

- Mkandawire-Valhmu, Lucy, and Patricia E Stevens. 2007. “Applying a Feminist Approach to Health and Human Rights Research in Malawi: A Study of Violence in the Lives of Female Domestic Workers.” Advances in Nursing Science 30 (4): 278–289.

- Moss, Pamela, ed. 2002. Feminist Geography in Practice: Research and Methods. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

- Müller, Martin. 2008. “Reconsidering the Concept of Discourse for the Field of Critical Geopolitics: Towards Discourse as Language and Practice.” Political Geography 27 (3): 322–338. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.12.003.

- Nagar, Richa, Victoria Lawson, Linda McDowell, and Susan Hanson. 2002. “Locating Globalization: Feminist (Re) Readings of the Subjects and Spaces of Globalization.” Economic Geography 78 (3): 25–284. doi: 10.2307/4140810.

- Nhema, Alfred G. and Tawanda Zinyama. 2016. “Modernization, Dependency and Structural Adjustment Development Theories and Africa: A Critical Appraisal.” International Journal of Social Science Research 4 (1): 151–166.

- Onwuegbuzie, Anthony, J. B. Wendy Dickinson, L. Nancy Leech, and G. Annmarie Zoran. 2009. “A Qualitative Framework for Collecting and Analyzing Data in Focus Group Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8 (3): 1–18. doi: 10.1177/160940690900800301.

- Pini, Barbara. 2002. “Focus Groups, Feminist Research and Farm Women: Opportunities for Empowerment in Rural Social Research.” Journal of Rural Studies 18 (3): 339–351. doi: 10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00007-4.

- Popkin, Barry M. 1998. “The Nutrition Transition and its Health Implications.” Public Health Nutrition 1 (1): 5–21.

- Popkin, Barry M. 2001. “The Nutrition Transition and Obesity in the Developing World.” Journal of Nutrition 31 (3): 871S–873S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.871S.

- Popkin, Barry M., Linda S. Adair, and Shu W. Ng. 2012. “Global Nutrition Transition and the Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries.” Nutrition Reviews 70 (1): 3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x.

- Preston, Valerie, and Ebru Ustundag. 2005. “Feminist Geographies of the “City”: Multiple Voices, Multiple Meanings.” In A Companion to Feminist Geography, edited by Lise Nelson and Joni Seager, 211–227. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Riley, Liam, and Belinda Dodson. 2014. “Gendered Mobilities and Food Access in Blantyre, Malawi.” Urban Forum 25 (2): 227–239. doi: 10.1007/s12132-014-9223-7.

- Riley, Liam, and Belinda Dodson. 2016. “Intersectional Identities: Food, Space and Gender in Urban Malawi.” Agenda 30 (4): 53–61. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2017.1299970.

- Satterthwaite, David, Gordon McGranahan, and Cecilia Tacoli. 2010. “Urbanization and Its Implications for Food and Farming.” Philosophical Transactions Royal Society London 365 (1554): 2809–2820. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0136.

- Schwartz, Jeremy I., David Guwatudde, Rachel Nugent, and Charles M. Kiiza. 2014. “Looking at Non-Communicable Diseases in Uganda Through a Local Lens: An Analysis Using Locally Derived Data.” Globalization and Health 10: 77.

- Sharp, Joanne. 2007. “Geography and Gender: Finding Feminist Political Geographies.” Progress in Human Geography 31 (3): 381–387. doi: 10.1177/0309132507077091.

- Shrimpton, Roger, and Claudia Rokx. 2013. The Double Burden of Malnutrition. A Review of Global Evidence. In Health, Nutrition, and Population (HNP) Discussion Paper. Washing D.C.: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

- STEPS. 2014. Noncommunicable Disease Risk Factor. Baseline Survey. Uganda 2014 Report. STEPS Report. Ministry of Health, World Health Organization, UNDP, World Diabetes Foundation.

- Steyn, Nelia P, and Zandile J Mchiza. 2014. “Obesity and the Nutrition Transition in Sub‐Saharan Africa.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1311 (1): 88–101.

- Streefland, Pieter. 2005. “Public Health Care under Pressure in sub-Saharan Africa.” Health Policy 71 (3): 375–382.

- Swinburn, Boyd, Gary Sacks, Stephanie Vandevijvere, Shiriki Kumanyika, Tim Lobstein, Bruce Neal, Simon Barquera, et al. 2013. “INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/Non-Communicable Diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): Overview and Key Principles.” Obesity Reviews 14: 1–12. doi: 10.1111/obr.12087.

- Tacoli, Cecilia. 2012. Urbanization, gender and urban poverty: paid work and unpaid carework in the city. Human Settlements Group, IIED.

- UBoS. 2016. The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Main Report. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

- UN. 2018. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision. Online Edition. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- Valentine, Gill. 2007. “Theorizing and Researching Intersectionality: A Challenge for Feminist Geography.” The Professional Geographer 59 (1): 10–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9272.2007.00587.x.

- Veronese, Guido, Marco Prati, and Marco Castiglioni. 2011. “Postcolonial Perspectives on Aid Systems in Multicultural Contexts: Palestine and Uganda.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 15: 545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.139.

- Warin, Megan. 2015. “Material Feminism, Obesity Science and the Limits of Discursive Critique.” Body & Society 21 (4): 48–76. doi: 10.1177/1357034X14537320.

- Wyrod, Robert. 2008. “Between Women’s Rights and Men’s Authority: Masculinity and Shifting Discourses of Gender Difference in Urban Uganda.” Gender & Society 22 (6): 799–823. doi: 10.1177/0891243208325888.

- Ziraba, Abdhalah K., Jean C. Fotso, and Rhoune Ochako. 2009. “Overweight and Obesity in Urban Africa: A Problem of the Rich or the Poor?” BMC Public Health 9 (1): 465.