Abstract

In this research article, I study seasonal labor migration in rural western India to understand gender negotiations in the course of labor migration. Based on qualitative research conducted in six villages in rural Maharashtra state in Western India during the early Kharif cropping season in 2014 and during Kharif and Rabi cropping seasons in 2015–16, I examine gendered labor in migrant home communities and at various rural and urban employment destinations, the relationship of labor to the social construction of masculinities, and gender negotiations across space. I show that in their home communities, the politics of resistance of returnee laborers can be understood by examining how returnee men deploy ‘protest masculinities’ to subvert claims on their body and labor by elite men who have historically been in a dominant relationship with the laborers. Yet, these protest masculinities are buttressed by the continued exploitation of women’s labor. I also show the flexibility of masculinities. More broadly, I show that migrant destinations themselves are gendered spaces that are constructed by the active consensual work of women and male migrants and employers alike. Second, seasonal migrants enter migration cycles from rural spaces that are gendered, both in production and social reproduction. I find that rural workplaces are the preferred choice of destination for migrant women; a choice that migrant men find reasonable. This is so because rural destinations are already gendered as spaces conducive for social reproduction and discursively constructed in the same terms as the idealized woman subject.

Introduction

Globally, 740 million people have migrated within their home geopolitical entities, i.e. they are internal migrants (UNDP Citation2009). Most of these internal migrants live in the world’s two most populous countries; a sixth of China’s population and over a quarter of India’s population (around 326 million) are internal migrants (Hugo Citation2014; Srivastava Citation2012). In India, between 30 million and 100 million people migrate seasonally (Deshingkar Citation2006), i.e. they are circular migrants, which is, ‘the fluid and repeated movement of people … between national rural and urban areas including internal cross-country migration’ (IOM Citation2015, 197). This article focusses on this important stream of population movement in rural western India in order to understand gender negotiations among migrants through the course of their sojourns and when they are back in their home villages. I examine how masculinities are constructed, transformed, and made flexible in the course of seasonal migration and how migrant work is intrinsically connected with gender negotiations and masculinities.

Feminist geographers’ significant contribution to migration studies includes the development of ‘insight into the gender dimensions of the social construction of scale, the politics of interlinkages between place and identity, and the socio-spatial production of borders’ (Silvey Citation2006, 66). A critical examination of migration provides a compelling opportunity to understand how gender subjectivities are constituted through the intersectional politics of class, race, and gender and sexuality (McDowell Citation2008). Additionally, there remains a pervasive challenge within gendered approaches to disengage ‘gender’ from merely being about ‘women’ and to deepen the gendering of masculine migrations (Ahmad Citation2009). Moreover, ethnographies of marginalized men and their performances of masculinities continues to remain understudied (Rogers Citation2008). This paper responds to these existing opportunities for expanding the frontiers of feminist geographic engagements both with studies of masculinities and labor migration in the Global South. In this paper, I draw attention to the sojourns of seasonal migrant laborers to multiple destinations; their negotiations of preexisting social power relations of class, caste, and gender both at these destinations and in their home communities; and the role of migration, work, and various axes of difference in the social construction of masculinities and place-based gender relations. My research, therefore, contributes to feminist geography, which has been at the scholarly forefront of ‘looking at the actions and meanings of gendered people, …, at the meaning of places to them, at the different ways in which spaces are gendered and how this affects people’s understandings of themselves as women or men’ (McDowell Citation1997, 382).

The emphasis in this paper on masculinities instead of merely gender roles is intentional, as this could neglect the ways in which both social discourses and individual performances, which are often in contradiction, together produce these ‘roles’ (Scott Citation1988). In the case of large numbers of people whose lives and livelihoods are determined by the informal labor market and its associated vulnerabilities, work plays an important role in the social construction of their gendered identities. The ability to earn an income and provide for their families is associated with men and the construction and reinforcement of masculinity. Indeed, an important aspect of ‘provider masculinity’ is earning income, and also includes ideas around control over resources, homosocial activity, and participation in the public sphere (Hodgson Citation2003). In Latin America, the increase in women’s participation in the formal labor market and the related decline in men’s employment in the market have empowered women, added additional work on their shoulders, and has often created a ‘crisis of masculinity’ among men (Vigoya Citation2001). Men’s response to social changes around them is often conceptualized as a ‘crisis of masculinity’. However, I argue instead that men’s reactions are a reconfiguration of their dominant position when men who are involved in gender conflicts reconstruct hegemonic masculinity to meet the demands of new economic and political conditions (Jeffrey Citation2010). Within particular cultural and historical contexts, certain forms of masculinity achieve a hegemonic position, and other masculinities are hierarchically positioned in relation to the norms associated with such hegemonic forms of masculinity (Connell Citation1995). ‘Hegemonic masculinity’, thus, denotes both the plurality and hierarchy of masculinities in various cultures and spaces (Connell and Messerschmidt Citation2005).

In several countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, the share of informal sector employment is around 90 percent (Chen Citation2005); yet, informal work may not readily map onto masculine constructs. In some instances, informal work is ‘real’ enough to affirm a valid performance of masculinity, while in other cases, it is not (Whitson Citation2010). Not all work is made the same; ‘it is work, albeit work that is “suitable” for a man, that confers and confirms the central attributes of masculinity’ (McDowell Citation2003, 833). In this paper, I explain the connections between labor in migrant home communities and at various rural and urban employment destinations, the relationship of gendered labor to the social construction of masculinity, and gender negotiations across space. I do this by first examining the breadth of literature on the relationship between gender, labor, and masculinities, and how these relations are embroiled in the processes of seasonal labor migration. Second, I outline the socio-economic profile of the sites in rural India, where this research was conducted. Third, I discuss, in two parts, how gender negotiations happen in the home villages of the returnee laborers and in various rural and urban migrant destinations. Finally, in concluding this paper, I summarize my findings to underscore how gendered migration and the production of gender subjectivities through migration also needs our attention.

Gender and work, the work of masculinities, and gendered migrations

Wo/men and work in the rural global South

Agricultural mechanization in the Global South has pushed men into higher-wage, off-farm work or to urban labor markets within their countries of origin or internationally, resulting in an increase in women’s share of work in agriculture (Pearson Citation2000). Indeed, agriculture is becoming ‘feminized’ across the Global South, from India, where women are dominating the rural wage labor market to Zambia, where women are increasingly diverting their productive labor to their own farms (Jackson Citation2013). However, the feminization of agriculture has not resulted in a corresponding improvement in women’s household decision-making roles (Deere 2005; Gunewardena Citation2010), as wage differentials between women and men continue to be prevalent. Further, the income-earning activities that are taken up by women are ideologically constructed as ‘female’ (Francis Citation2002); with spaces of work at home and at migrant destinations becoming sites for disciplining sexuality and the reproduction of the normative heterosexual family (Preibisch and Grez Citation2010). These important contributions, however, do not clarify, in the context of the circulation of agricultural laborers within rural and between rural and urban areas, how gender is negotiated during, before, and after migration and how these negotiations are situated within the ambit of a rural political economy, where these laborers occupy a decidedly subaltern position within structures of agrarian class, caste, and gender relations.

The role of work in the construction of masculinity

Gendered power relations are better understood through an analysis of the social construction of masculinity (Campbell and Bell Citation2000). In the case of agriculture, the ability to harness nature for production is central to hegemonic masculinity (Bryant Citation1999). There is a clear relation between productive work and masculinity. Men’s work that gives them control over capital and property places them in a position of power; however, for working men, this is not the case since they own little of either. The foundation of masculine predominance over women and children is the ability of men to sustain themselves and their families by engaging in work (Fuller Citation2000).

In South Asia, the distinctive ‘good man’ is one who engages in productive work and thus, provides for his heteronormative family. However, upper caste elites, especially those who either earn from their land or from white-collar jobs, have a disparaging view of agricultural manual labor, to the extent that they withhold the granting of ‘mature male’ status on laboring men and infantilize them as irresponsible adolescents (Osella and Osella Citation2006). Jeffrey (Citation2010) has outlined how leisure practices differentiate and cause animosity among college-educated, urban, upper-caste/class youth and the middle and lower caste/class youth, because of the ability of the former to convert their increased access to full-time, well-paying jobs in a neoliberal economy to expensive acts of leisure, such as eating out at restaurants and buying expensive food. For the latter, however, ‘leisure’ is the temporal waiting room populated by youth hoping to find employment in an economy of jobless growth.

Marginalization creates conditions for exaggerated claims of potency and hyper-masculinity embodied in ‘protest masculinity’ (Connell Citation1995). Men who do not find themselves associated with the dominant culture, construct their own gender identity by ‘negotiating the meanings and practices of their own original culture and that of the dominant majority’ (Gilbert and Gilbert Citation1998, 146). Powerlessness and insecurity build protest masculinity that is deployed to claim power in the context of the absence of resources to secure power (Walker Citation2006). Protest masculinity, thus, encapsulates embodied practices of men who are systemically undermined by the social hierarchies within which they are enmeshed. I argue that the elite and the subaltern are not fixed in place, geographically and culturally. As laborers travel in search of livelihood opportunities, they confront new conditions under which they are forced to negotiate their gender identities. I examine how work and employment are harnessed for the construction of masculinity, the role of work in the construction of non-hegemonic masculinity, and how migration reworks masculinity and gendered social relations, as laborers migrate between one exploitative labor market and another.

Migrant subjectivities and social change

Feminist geographers argue that migration patterns, meanings, and experiences are produced as migrant subjectivities operate in conjunction with labor markets, wage differentials, and legal regulations (Silvey Citation2004). Beyond cultural differences, ‘men’ and ‘masculinity’ come to be defined contra women and femininity. Among men, hierarchization centered on masculine characteristics produces the super-masculine or the dominant form of masculinity, which is hegemonic. In other words, ‘hegemonic masculinity’ is an idealized or desired masculinity discursively produced in ideas and concretized in style and practices of dominance. The values associated with hegemonic masculinity, i.e. certain ways of being and behaving, is what all men measure themselves against (Connell Citation1987). The association of masculinity with power, however, varies with cultural contexts (Cornwall and Lindisfarne Citation1994). Note that hegemonic masculinity does not operate in a social vacuum; our understanding of the impact of the hierarchies beset within class, race, and sexuality on men’s lives would enable a clearer understanding of masculinities more broadly (Hibbins and Pease Citation2009).

In South Asia, productive work, earning and spending money, and the act of being in public spaces are all coded as masculine activities (Chopra Citation2004). In Indian factories, women work in segregated or restricted areas in comparison to their male counterparts. In these factories, a ‘worker’ is often gendered as masculine and the presence of women in a space that is coded as masculine is viewed with suspicion, with association of women and femininity with social reproduction (Osella and Osella Citation2006). Migrants’ temporary stay in cities, however, provides them with unique cultural exposures and an opportunity to view their roles as men and women differently. Migrant men who bring with them to their destinations, firm beliefs and well-established practices about manhood and gender relations, find themselves compelled to change their own understanding of masculine identity and their relationships with their spouses and families (Donaldson and Howson Citation2009). Yet, it remains unclear how migrant destinations and the social relations that constitute these places produce new labor masculinities and how these masculinities become grounds for new contestations over social power in migrant home communities. Hence, I focus on how masculinities are negotiated during seasonal migration by large numbers of the rural poor, applying gender as an analytic of power (Ramamurthy Citation2000). I examine how these categories are constructed through seasonal migration.

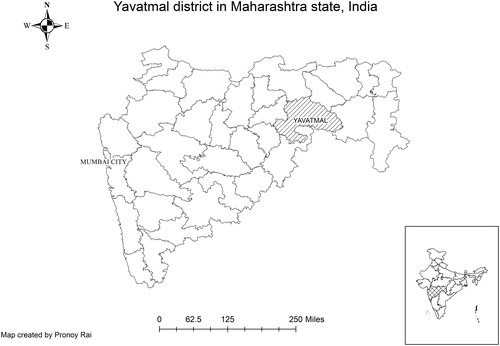

Season migration and gender negotiations in rural Maharashtra

I study the relations between seasonal migration, masculinities, and gender negotiations in Maharashtra state (see ), where rural populations have been impacted by long-term agrarian distress (Vasavi Citation2009). As a result, in Yavatmal district in Maharashtra, where I conducted this research, rural labor relations have been reshaped resulting in the reduced ability of farmers to negotiate down the wages demanded by laborers, increased ability of both returnee and non-migrant laborers to demand dignified conditions of work, and changes in ‘farmer’ subjectivity (Rai Citation2018). In Maharashtra, close to half of the population (around 61.5 million people) live in villages, where farming households own an average of 1.4 hectares of agricultural land (Government of India 2014). In Yavatmal district, around 334,000 people own agricultural land; however, twice as many are landless laborers who work on farmers’ lands (Government of Maharashtra 2014). The dependence of a large population on small landholdings creates fertile conditions for out-migration.

Yavatmal district is a part of the Amravati administrative division in eastern Maharashtra where 10 percent of the state’s population resides, and three-fourths of this population is involved in agriculture. However, the division’s contribution to the agricultural sector of the state is a low 13.6 percent (Government of Maharashtra 2013). This is in part because only six percent of the land where crops are grown is irrigated, while the rest is rainfed. The Compound Annual Growth Rate in agricultural incomes over the period 1999–2012 in eastern Maharashtra is an abysmally low 0.3 percent. This stagnation in agricultural incomes means that agriculture is not a reliable source of livelihood both for laborers as well as farmers who employ them. In rural Maharashtra, migration is central to the social reproduction of marginalized communities. It is important to note, however, that most of this seasonal labor migration is linked with the reproduction of rural households; in Maharashtra, almost three-quarters of the migrants migrate out to work in low-paying temporary jobs and 63 percent of migration is intra-rural (Government of Maharashtra 2010; Chandrasekhar and Sharma 2014). This paper grounded in the experiences of the migration of rural laborers, who are socially and economically marginalized both in their home communities and in the migrant destinations, provides a unique opportunity to understand how gender relations are negotiated at the margins of rural society and how these in turn, produce new meanings of situated masculinity.

Methodology, field villages, and research methods

I conducted research for this paper by applying qualitative methods in five villages in rural Yavatmal district in the early Kharif cropping season in 2014 (June–July) and during Kharif and Rabi cropping seasons in 2015–2016 (June–February.) I created lists of landowners, most of whom are from the upper Hindu castes, and landless laborers who are generally lower-caste Hindus and converted Buddhists. Thereafter, I stratified the landless laborers by caste and then sampled using random sampling within the stratified caste groups. These villages were homogeneous and home to majority landless agricultural laborers and small landowning farmers. Caste hierarchy often determined land ownership.

I conducted 133 interviews, with landless laborers (both women and men), landowning and labor-employing farmers (almost always, men), and labor intermediaries (called Muqaddams, all men) who work on behalf of cane factories to hire, transport, and supervise labor on cane fields in western Maharashtra and neighboring northern Karnataka state. I interviewed all 49 labor-employing farmers and 12 Muqaddams in the villages, given their relatively smaller number. Non-migrant laborers are those who live and work in their home villages. I interviewed a sample of agricultural laborers (both seasonal migrants/returnees and non-migrants) across caste to ensure representation of all major lower castes in the region, such as Mahars and Banjaras. Agricultural labor is tied to untouchability status and is a common occupation among the formerly untouchables or Dalits (Omvedt Citation1993). Farmers who own land and employ agricultural laborers are overwhelmingly not Dalits. Caste and class are, therefore, tied both statistically and through imaginaries (Osella and Osella Citation2006).

The migration cycle of rural laborers in Maharashtra follows the rhythm of crop harvest cycles in migrant destinations and home villages. Laborers typically migrate out across the state’s south-eastern border into Telangana state in October to pick cotton and thereafter in November to western Maharashtra and across the state’s southwestern border into Karnataka state to harvest cane. Conducting research at the home villages of the laborers meant that since I was the only ‘foreigner’, I was learning from my research subjects. The choice that feminist geographers typically make to conduct research, especially interviews and focus group discussions, in the homes or as in the case of my research, the home communities of the research participants, is hinged on the argument that participants can share information freely and that home, as geographic place, plays a vital role in disrupting the power hierarchies between the researcher and the participants (Elwood and Martin Citation2000). The seasonal migrants of Yavatmal district are ‘still rooted’ in their home villages (McHugh 2000, 79), which they clearly identify with ‘home’ through kinship networks, spatial familiarity, and cultural-linguistic knowledge. Given my own acquaintance with the region through my research projects since 2012, I conducted this research while the seasonal migrants were in their home villages. To my knowledge, long-term studies of changes in gendered social relations do not exist in this region [See Rai (Citation2013) and Rai and Smucker (Citation2016)], thus, presenting an opportunity for an empirical inquiry.

During migration: the gendering of migrant destinations and work

Migrants in rural Maharashtra seasonally migrate within and outside their home state to find work in rural, urban, and peri-urban areas. The key migration streams from rural Yavatmal district are to (a) irrigated areas for agricultural labor; (b) cotton processing factories, called ginning and pressing factories; (c) agricultural fields in other rainfed villages to pick cotton; (d) sugarcane fields to harvest cane; (e) brick kilns in peri-urban areas; and (f) cities to work on construction projects as day laborers. Major migration streams, the gender distribution of work, and gender negotiations are now discussed.

Cotton fields: On the cotton fields, migrant women are widely acknowledged as more efficient cotton pickers and thus, are the principal earners. Yet, men are reluctant to code cotton picking as ‘women’s work’. Further, women and men are not paid individual daily wages but paid as a unit for the harvest. Therefore, the extraction of value from cotton fields through cotton picking is undergirded by the valorization of women’s labor. Laborers find cotton fields to be a suitable location for temporary residence. A woman laborer said, ‘I prefer working in the cotton fields. We get a place to stay, firewood, and water. It’s more convenient than any other place that I have worked outside [of my home village]’ (a woman migrant laborer, interview with the author, 3 September 2015). Women prefer to migrate to cotton fields also because cotton fields cause relatively less disruption to the work of social reproduction. A migrant laborer explained,

My husband and I migrate to the cities to work on construction sites and try to return home as soon as we can. If we stayed longer, we wouldn’t be able to go to the cotton fields in Telangana to pick cotton. Our family works together in the cotton fields. In the cities, it would be just me and my husband (a migrant woman laborer, interview with the author, 3 September 2015).

Women cook at home in these destinations as they do in their home villages. While women are responsible for the work of reproduction, despite their labor efficiencies, women gain little relative to men, in terms of their share of the exchange value of cotton. However, the proximity of several of these cotton fields to forests produces risky human-(wild) animal interactions. So, for migrants, cotton fields are desired because these spaces both valorize women’s labor and create conditions for the social reproduction of labor households identical to their home villages.

Sugarcane fields: Sugarcane factories in western Maharashtra contract village-based Muqaddams to hire migrant labor. Migrant laborers are hired in toley (group) of twenty laborers, often consisting of ten married heterosexual couples. The payment for harvesting cane is made to couples in the form of a lump sum loan, months in advance of their travel to the cane fields, which guarantees labor supply for the sugar factories during the harvest season. Toleys move from one sugarcane field to another until they have paid off their loans.

The work of production (harvesting cane) and social production in sugarcane fields are highly gendered, thus, re-producing the patriarchal social power relations that structure social life in migrant home villages. A laborer explained, ‘Men typically cut cane and women tie the cane into bundles. If men slow down or are feeling sick, women take over and cut cane instead. At that point, men would need to tie the cane into bundles’ (a migrant male laborer, interview with the author, July 2014). Women also assist with cutting when men are exhausted. A laborer explained, ‘It’s easy to cut the first harvest but it’s harder to cut the second and third harvests that grow from the cane stump. We need women’s help with the latter’ (a migrant male laborer, interview with the author, 2 September 2015).

Muqaddams, who supervise cane harvesting in the fields, make various ‘concessions’ for the women in the toley so that they can attend to their household responsibilities. A migrant laborer explained,

Men leave early in the morning to cut cane; we join them later after we have finished cooking. When we arrive at the fields, we serve food to our men and then tie up the cane that the men would have cut in the morning into bundles (a migrant woman laborer, interview with the author, 30 July 2014).

In the evening, laborers return to their tents together and women cook and clean their tents. In his longitudinal study of the political economy of cane harvesting in rural western India, Bremen (1990) suggests that the composition of the toleys has become younger, relatively more land-poor/landless and the number of seasons that laborers travel to the cane fields have become fewer, further asserting that ‘only the very strongest are prepared to subject themselves year after year to the murderous work regime associated with the campaign [of seasonal cane harvesting]’ (1990, 590). The payment of labor wages in advance as a loan and the gendering of the work of social reproduction and production, therefore, must be read in the context of socio-economic exploitation of cane laborers.

Urban construction sites: Migrant labor living accommodations are typically leased single-room quarters in the slums adjoining construction sites. Male laborers prefer for the women in their families to not migrate to cities. Men argue that both cane and cotton fields, unlike the cities, are more akin to their home villages and thus familiar for women; cities, the men presume, are difficult for the women to navigate. Construction sites do not provide the kind of extended familial support that is available on cotton and sugarcane fields. A young, unmarried migrant laborer explained,

We migrate as a family to the cane fields. I am unmarried, and I go along with my brother and sister-in-law. She cooks for us there. Women don’t always travel with us to the cities, where meals are expensive. In the cities, I buy prepared meals from roadside eateries, which quickly becomes a drain on my savings. We save more when we are in the cane fields and it’s a bit more convenient there (a migrant male laborer, interview with the author, 22 October 2015).

In urban factories, men work on the machines or engage in tasks that require physical lifting and carrying. Women are employed to cut, sew, and clean. On construction sites, rural migrant men are tasked with mixing concrete while rural women migrants are responsible for carrying concrete in baskets on their heads to the buildings under construction. Regardless of the nature of work, women are paid close to half of men’s wages. This suggests direct wage discrimination as well as women’s limited access to tasks with higher remuneration (Fletcher, Pande, and Troyer-Moore 2017). The inflexibility of wages paid to women regardless of the tasks done by them, however, is reflective of women in the labor market as ‘inferior bearers of labor’ instead of ‘bearers of inferior labor’ (Kabeer Citation1996). In their cramped residential quarters in the urban slums, women wake up earlier than men do, attend to cooking and cleaning, and race to be at work at the same time as men. However, when the women are late to work, their husbands are rebuked by the contractors. Men who travel to cities alone, congregate and cook together. More ‘considerate’ urban labor contractors allow women to leave work a bit earlier than men for household chores. Not only are migrant women laborers’ access to tasks with higher remuneration restricted, but they are also expected to perform unpaid labor for social reproduction, which is sometimes ‘incentivized’ by the contractors through limited flexibility in work hours.

Migrant experiences at various destinations explain multiple strands of gender negotiation during seasonal migration. First, on sugarcane and cotton fields, instead of paying individual wages, piece-rate payments are made to the migrant laborers as heteropatriarchal married couples, thus allowing capitalist farmers to appropriate surplus from women laborers. This tethering of the labor of women and men clearly renders marriage as a gendered social institution that is sine qua non, necessary not just for men to assert and claim masculinity, but also to be able to access particular labor markets for the migrants. Second, the cotton fields where migrant male laborers help pick cotton akin to the women laborers’ assistants, are in stark opposition to farms in migrant home villages where the men would not do the ‘women’s work’ of weeding. Yet, cotton picking, where the male laborers can neither demonstrate their efficiency or ability to perform macho lifting work, is preferred by rural migrant men. Feminist geographers have theorized ‘flexible and strategic masculinities’ that allow men to put on hold characteristics of their gender identity while they are away working in foreign cities temporarily, while selectively emphasizing aspects of their gender identity that would benefit them in the labor market (Batnitzky, McDowell, and Dyer Citation2009). This could be easily said of seasonal migrant men in rural Maharashtra, but more importantly, I emphasize the social construction of flexible masculinities that involves the performance of flexible masculinity by migrant men and the embroilment of migrant women and the (male) employers. Migrant destinations are socially produced gendered spaces where employers often allow migrant laborers to act as properly gendered subjects, where women cook food, clean their dwellings, and attend to their children and men leave for work early in the morning, to mimic gender performances in the migrant home villages. The multitude of constructions of gender relations in the places and spaces outlined in this section that are produced through a mosaic of migration streams for livelihood, further advances and undergirds feminist geographers’ claims of the centrality of geography in the social construction of gender relations and masculinities (Massey Citation1994).

Third, the consensus among seasonal migrants that rural migrant women prefer to work in rural destinations and not in the cities accounts for the weight given in the household to the women’s ability to continue to participate in social reproduction at and away from their home communities in certain migrant destinations. It also accounts for how the ‘rural’ is discursively produced as the virtuous ‘other’ in comparison to the cities, filtered through patriarchal assumptions of where women would become ‘corrupted’ and where they could be better controlled. The connections between women’s decision on where they choose to migrate and their ability to participate in social reproduction have been explored by feminist geographers (Whitson Citation2010). Migrants in rural Maharashtra prefer rural destinations for women migrants, i.e. places where employers provide shelter and access to drinking water and electricity because it is easier for women to bring children along to these places. Rural employers who permit migrant women to attend to household needs, such as cooking food and cleaning their dwellings, effectively allow migrant women to perform their principal roles in social reproduction. Further, men’s paternalistic sense of well-being for women justified through marriage or kinship imposes modes of policing and surveillance on women migrants in rural destinations. Male migrants, thus, characterize rural areas using the same registers that are used to construct an ‘honorable’ woman through the male gaze, which is, virtuous, untainted, and tamable. The broader claim I make here is that the sum of migrant home communities and various migrant destinations are the quintessential ‘cultural contexts’, where the limitations of women’s mobility in terms of identity and space is a means of women’s subordination (Massey Citation1994).

Before and after migration: negotiating gender

Gender negotiation in the home villages of the returnee laborers happens through the active gendering of work in agriculture, the masculinizing of ‘women’s work’ or the compensating of the loss of masculinity that is experienced when men perform ‘women’s work’, by the payment of higher wages to non-migrant men who are employed by farmers, and through gendered power relations that determine where and when women and men migrate.

Gendering work in agriculture

In their home villages, women’s roles in agriculture are limited to weeding and harvesting, while men till, plow, spray pesticides and insecticides, and dig drainage canals. Returnee male laborers do weeding only when they are in conditions of penury. A farmer explained, ‘It doesn’t look good on male laborers to do “women’s work”’ (a labor-employing male farmer, interview with the author, 19 July 2015). The stereotypes that masculinize certain works because of their relation to physical strength are a result of the gender segmentation of the labor market (Pineda Citation2000).

Men do weeding, however, when they are offered wages higher than women’s wages. A farmer remarked, ‘Men ask for two times the “women’s wages” without doing double the work’ (a labor-employing male farmer, interview with the author, 1 July 2014). A returnee laborer explained why these wage differences are not about the relative contribution of productive labor,

Farmers seek to hire us to do weeding and other ‘women’s work’ and pay us ‘women’s wages’. How can we work on women’s wages? Would be it suffice for men to work on women’s wages? So, we don’t work here and find work elsewhere (a migrant male laborer, interview with the author, 5 September 2015).

Despite wage discrimination, men find weeding embarrassing and unbecoming as masculine work. Male farmers and laborers justify their unwillingness to do weeding by explaining the physical inability of men to bend down to work, which is required. In the rural Global South, men plow, sow, spray, fertilize, and transport, while women’s work is transplanting seedlings and weeding. The gender dimension of the agricultural division of labor is reinforced by its ritual aspect, which implicitly represents the land as a goddess, who is plowed, sown, and fertilized (impregnated) by men, while women nurture (grow, gestate) the seedlings. A masculine status apparently consolidated in one arena – work – requires reiterated performance to maintain its effectiveness (Delaney Citation1992).

Another agricultural occupation that is coded as masculine is the Saldari labor contracting system, where laborers work for farmer households arranged through annual contracts. Since women are principally involved in social reproduction, they are not hired as Saldars, who spend around 16-18 hours every day working for a farmer, and hence, do not contribute their labor within their own household.

Protest masculinity and the gendered exploitation of labor

In rural Maharashtra, in addition to spaces of work, the spaces of leisure are gendered. Male migrant laborers upon their return, spend their waking hours sitting in the village square and not working locally. A farmer remarked, ‘Unlike male returnees, women returnee laborers for us. These men just eat and hang around in the village [upon their return]’ (a labor-employing farmer, interview with the author, 26 October 2015). Women laborers do not agree with the farmers on the reasons why men do not work upon their return. A non-migrant laborer explained,

Men [laborers] don’t find a lot of work around here [in agriculture.] Women, both returnee and non-migrant, are willing to work for the low wages offered by the farmers but men would not work for those wages (a non-migrant woman laborer, interview with the author, 31 October 2015).

The male laborers’ ability to migrate, however, has empowered them to decline (the limited) work opportunities at home. In the Indian rural society, where upper-caste landed farmers expect lower-caste laborers to accept any work offered to them on the farmers’ terms (Omvedt Citation1979), laborers can decline work due to their newfound ability to migrate and accumulate savings – as I discuss below.

Landed farmers have little tolerance for returnee men spending their time idling and chatting in the village square, which is a departure from the past when lower-caste men toiled in the upper-caste farmers’ fields all day. This performance of carefree aloofness by returnee male laborers against the historically dominant community of landed farmers has a resonance in the performative politics. The use of public spaces by historically disenfranchised and discriminated men, who have few avenues to leverage well-remunerated work to attain a valued identity to enact forms of protest masculinity for attaining a gendered position of power among all men has also shown to have value elsewhere (Majors and Billson Citation1992; Wilton, DeVerteuil, and Evans Citation2014).

This form of resistance to historically dominant social relations in Yavatmal is gendered, and women are excluded. In rural Gujarat state to the north of Maharashtra, seasonal migration has transformed the political consciousness of young, lower caste Vankar laborers. However, Vankar women are excluded from these changes because their participation, unlike those of Vankar men continues to remain constrained (Gidwani and Sivaramakrishnan Citation2003). The village square, as a space for leisure, is masculinized. A woman laborer explained, ‘women do not hang out in the village square because they are busy throughout the day; they are weeding [farmers’ lands], or cleaning, cooking, or taking care of their children at home’ (a migrant woman laborer, interview with the author, 17 July 2015).

In addition to the significantly higher exploitation of women’s productive and reproductive labor, traditional patriarchal norms regarding gendered access to the village square for leisure occlude women’s access to this space. A local commuting laborer explained,

It’s not a tradition in this village for women to sit and chat in the public. Instead, when women have spare time, they sit together on the mud road in front of their houses and chat with each other. They talk as they peel garlic skin for meal preparation (a commuting male laborer, interview with the author, 19 July 2015).

Public spaces, including the village square and the mud road in front of huts, are not only gendered, but women’s access to their own space of leisure is also merely an extension of their unending burden of reproductive labor in their households.

In southern India, lower caste male agricultural laborers have refused agricultural work offered by upper caste Reddy farmers to express their contempt for the historical farmer-laborer work relations that include laborers’ experience of receiving low/unpaid wages and physical and verbal abuse. For the social reproduction of their households, however, women laborers continue to work for the farmers often under exploitative conditions (da Corta and Venkateshwarlu Citation1999). Yet, the politics of labor resistance understood through the optics of male returnee laborers’ resistance and agency, is circumscribed within and bolstered by the New Social Movements in India because lower caste laborers have demanded equitable outcomes of national development processes since the 1970s (Omvedt Citation1994).

In their newfound ability to decline work and define leisure in their own terms by occupying the village square during ‘work hours’, I find the performance of male returnee laborers’ as a form of protest masculinity. Migrant laborers are both asserting their selves as individuals who can make social and economic choices and who do not exist in semi-feudal relations with farmers. They are declining work offered by upper-caste farmers whose historical legacy of exploitation of lower-caste labor families have left deep scars. Similarly, the continued exploitation of the productive and reproductive labor of women returnees is leading to a temporal, localized feminization of agricultural labor as only (returnee) men withdraw from agricultural labor in their home communities.

The key characteristics of protest masculinities include independence and street space. These are important in creating hyper-masculine identities (Nayak Citation2003), which are central to protest masculinities. I claim here that the association of protest masculinities with working-class men is partial and must account for how these acts of resistance against hegemonic forms of masculinities or class relations are sustained on the exploitation of women’s labor, often with little acknowledgment. I do not claim that protest masculinities have bearing on labor rights, access to privileges in the workspace, and work availability, yet they are a protest of the relations of production (Walker Citation2006). These have stratified the agrarian society both in terms of access to factors of production, and the experiences of discrimination, degradation, and humiliation over generations (Guru Citation2009), with the former telescoped among landed farmers and the latter among lower-caste landless laborers. Elsewhere, I have focused on other, related aspects of the connections between seasonal labor migration and social change in migrant home communities (Rai, Citation2018). Specifically, I have analyzed the returnee laborers’ acts of resistance against their employers (landed farmers) in their own home villages.

Conclusion

I make the following two major claims in this paper. First, the politics of resistance of seasonal migrants can be understood by examining how returnee laborers deploy protest masculinities to subvert claims on their body and labor by elite male farmers who have historically been in a dominant relationship with the laborers. I argue that protest masculinities do not emerge in a vacuum; they are buttressed by continued exploitation of women’s labor, as subaltern men attempt to renegotiate their relations with elite men. Along these lines, I also show the flexibility of masculinities, where male migrant laborers find it offensive to do ‘women’s work’, such as weeding in their home villages, but do not mind working alongside women in cotton fields given the relatively higher monetary returns associated with cotton picking. More broadly, I show that migrant destinations themselves are gendered spaces that are constructed by the active consensual work of migrants and employers alike.

Second, seasonal migrants enter migration cycles from rural spaces that are gendered, both in production and social reproduction. In these spaces, masculinity is iteratively constructed through gendering of work and the masculinizing of ‘women’s work’ when performed by men through monetary incentivization. Rural destinations are preferred by migrant women and for them by migrant men because rural destinations are gendered as spaces conducive for social reproduction and discursively constructed in the language of the idealized woman.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Social Science Research Council and the University of Illinois (Women and Gender in Global Perspectives program, Graduate College, and the Department of Geography and GIS.) I am grateful to Trevor Birkenholtz (The Pennsylvania State University) for his extensive comments on various drafts of this paper and to Tom Bassett and Susan Koshy (both at the University of Illinois) and Sara Smith (The University of North Carolina) for their comments on the original manuscript. This research would not have been possible without the generous hospitality of Gopikabai Sitaram Gawande College in Maharashtra and the support of College Mentors, Sushila Gawande (Auburndale, MA) and Meeta Gawande (Boulder, CO); College Trustee, Yadaorao Raut; College Vice-Principal, Someshwar Vadrabade; and my field assistant, Vatan Rathod (all in Yavatmal district, Maharashtra.) Finally, I am indebted to the journal editor, Kanchana Ruwanpura (Edinburgh), and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that helped me refine my arguments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pronoy Rai

Pronoy Rai is an assistant professor of International and Global Studies, an affiliated faculty in the Department of Geography, and a faculty fellow of the Institute of Sustainable Solutions at Portland State University in the USA. He is also the Treasurer of the Association of American Geographers’ Geographic Perspectives on Women specialty group. His scholarly interests are in masculinities and social reproduction; labor migration and social and environmental change; and agrarian studies. Rai is currently completing a project on the social geographies of labor migration in rural India and has been conducting long-term ethnographic research in rural Maharashtra in India since 2012. He has published his research in Geoforum and the Journal of Rural Studies. Rai earned a Ph.D. in Geography in 2018 and a Graduate Minor in Gender Relations in International Development in 2015 from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His research has received support from the Social Science Research Council, Friends of India Endowment Trust (Athens, OH, USA), University of Illinois, and Ohio University.

References

- Ahmad, Ali Nobil. 2009. “Bodies That (Don’t) Matter: Desire, Eroticism and Melancholia in Pakistani Labour Migration.” Mobilities 4 (3): 309–327. doi:10.1080/17450100903195359.

- Batnitzky, Adina, Linda McDowell, and Sarah Dyer. 2009. “Flexible and Strategic Masculinities: The Working Lives and Gendered Identities of Male Migrants in London.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (8): 1275–1293. doi:10.1080/13691830903123088.

- Breman, J. 1990. “‘Even dogs are better off': The ongoing battle between capital and labour in the cane-fields of Gujarat.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 17 (4): 546–608.

- Bryant, Lia. 1999. “The Detraditionalisation of Occupational Identities in Farming in South Australia.” Sociologia Ruralis 39 (2): 236–261. doi:10.1111/1467-9523.00104.

- Campbell, Hugh, and Michael Mayerfeld Bell. 2000. “Introduction. Rural Masculinities Special Issue.” Rural Sociology 65 (4): 532–546. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2000.tb00042.x.

- Chandrasekhar, S., & Sharma, A. 2014. Urbanization and Spatial Patterns of Internal Migration in India. Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

- Chen, Martha Alter. 2005. The Progress of the World’s Women 2005: Women, Work and Poverty. New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women.

- Chopra, Radhika. 2004. “Encountering Masculinity: An Ethnographer’s Dilemma.” In South Asian Masculinities: Context of Change, Sites of Continuity, edited by Radhika Chopra, Caroline Osella, and Filippo Osella, 36–59. Delhi: Women Unlimited.

- Connell, Raewyn W., and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept.” Gender & Society 19 (6): 829–859. doi:10.1177/0891243205278639.

- Connell, Raewyn W. 1987. Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity.

- Connell, Raewyn W. 1995. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Cornwall, Andrea, and Nancy Lindisfarne. 1994. “Dislocating Masculinity. Gender, Power and Anthropolgy.” In Dislocating Masculinity, edited by Andrea Cornwall and Nancy Lindisfarne. London and New York: Comparative Ethnographies.

- da Corta, Lucia, and Davuluri Venkateshwarlu. 1999. “Unfree Relations and the Feminisation of Agricultural Labour in Andhra Pradesh, 1970–95.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 26 (2–3): 71–139. doi:10.1080/03066159908438705.

- Deere, Carmen Diana. 2005. The Feminization of Agriculture? Economic Restructuring in Rural Latin America. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

- Delaney, Carol. 1992. The Seed and the Soil: Gender and Cosmology in Turkish Village Society. Vol. 11. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Deshingkar, Priya. 2006. Internal Migration, Poverty and Development in Asia. ODI Briefing Paper 11. London: The Overseas Development Institute.

- Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Government of Maharashtra. 2010. A Report on ‘Migration Particulars’ Based on Data Collected in State Sample of 64th Round of National Sample Survey (July 2007–June 2008). Mumbai: Planning Department, The Government of Maharashtra.

- Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Government of Maharashtra. 2014. Population Census - Standard Reports. Retrieved from Maharashtra State Data Bank (2011): https://mahasdb.maharashtra.gov.in/population1.do.

- Donaldson, Mike, and Richard Howson. 2009. “Men, Migration and Hegemonic Masculinity.” In Migrant Men: Critical Studies of Masculinities and the Migration Experience, edited by Mike Donaldson, Raymond Hibbins, Richard Howson, and Bob Pease, 210–217. New York: Routledge.

- Elwood, Sarah A., and Deborah G. Martin. 2000. “‘Placing’ Interviews: Location and Scales of Power in Qualitative Research.” The Professional Geographer 52 (4): 649–657. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.00253.

- Francis, Elizabeth. 2002. “Gender, Migration and Multiple Livelihoods: Cases from Eastern and Southern Africa.” Journal of Development Studies 38 (5): 167–190. doi:10.1080/00220380412331322551.

- Fletcher, Erin and Pande, Rohini and Moore, Charity Maria Troyer, Women and Work in India: Descriptive Evidence and a Review of Potential Policies (December 1, 2017). HKS Working Paper No. RWP18-004. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3116310.

- Fuller, Norma. 2000. “Work and Masculinity among Peruvian Urban Men.” The European Journal of Development Research 12 (2): 93–114. doi:10.1080/09578810008426767.

- Gidwani, Vinay, and K. Sivaramakrishnan. 2003. “Circular Migration and the Spaces of Cultural Assertion.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 93 (1): 186–213. doi:10.1111/1467-8306.93112.

- Gilbert, Rob, and Pam Gilbert. 1998. “Masculinity Crises and the Education of Boys.” Change (Sydney, NSW) 1 (2): 31.

- Gunewardena, Nandini. 2010. “Bitter Cane: Gendered Fields of Power in Sri Lanka’s Sugar Economy.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35 (2): 371–396. doi:10.1086/605481.

- Guru, Gopal. 2009. Humiliation: Claims and Context. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Hibbins, Raymond, and Bob Pease. 2009. “Men and Masculinities on the Move.” In Migrant men: Critical studies of masculinities and the migration experience, edited by Mike Donaldson, Raymond Hibbins, Richard Howson and Bob Pease, 1–19. New York: Routledge.

- Hodgson, Damian. 2003. “Taking It like a Man”: Masculinity, Subjection and Resistance in the Selling of Life Assurance.” Gender, Work & Organization 10 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1111/1468-0432.00001.

- Hugo, Graeme. 2014. Urban Migration Trends, Challenges, Responses and Policy in the Asia-Pacific. Background paper for the World Migration Report 2015, Migrants and Cities: New Partnerships to Manage Mobility. Geneva: IOM.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2015. World Migration Report 2015; Migrants and Cities: New Partnerships to Manage Mobility. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

- Jackson, Cecile. 2013. Men at Work: Labour, Masculinities, Development. New York: Routledge.

- Jeffrey, Craig. 2010. “Timepass: Youth, Class, and Time among Unemployed Young Men in India.” American Ethnologist 37 (3): 465–481. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01266.x.

- Kabeer, Naila. 1996. “Agency, Well‐Being & Inequality: Reflections on the Gender Dimensions of Poverty.” IDS Bulletin 27 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.1996.mp27001002.x.

- Majors, Richard, and Janet Mancini Billson. 1992. Cool Pose: The Dilemmas of Black Manhood in America. New York: Touchstone.

- Massey, Doreen. 1994. “Introduction to Part III: Space, Place and Gender.” In Space, Place and Gender, edited by Doreen Massey, 1–280. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McDowell, Linda. 2008. “Thinking through Work: Complex Inequalities, Constructions of Difference and Trans-National Migrants.” Progress in Human Geography 32 (4): 491–507. doi:10.1177/0309132507088116.

- McDowell, Linda. 2003. “Masculine Identities and Low-Paid Work: Young Men in Urban Labour Markets.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27 (4): 828–848.

- McDowell, Linda. 1997. “Women/Gender/Feminisms: Doing Feminist Geography.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 21 (3): 381–400.

- McHugh, Kevin E. 2000. “Inside, outside, upside down, backward, forward, round and round: a case for ethnographic studies in migration.” Progress in Human Geography 24 (1), 71–89.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India. 2014. Agriculture Census 2010-11. Agriculture Census Division, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India. 2014. “Last of the “Real Geordies”? White Masculinities and the Subcultural Response to Deindustrialization.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 21 (1): 7–25. doi:10.1068/d44j.

- Nayak, Anoop. 2003. “Last of the “Real Geordies”? White Masculinities and the Subcultural Response to Deindustrialization.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 21 (1): 7–25. doi:10.1068/d44j.

- Omvedt, Gail. 1994. “We Want the Return for Our Sweat’: The New Peasant Movement in India and the Formation of a National Agricultural Policy.” J. Peasant Stud 21 (3-4): 126–164. doi:10.1080/03066159408438557.

- Omvedt, Gail. 1993. Reinventing Revolution: India’s New Social Movements and the Socialist Tradition in India. Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe.

- Omvedt, Gail. 1979. “The Downtrodden among the Downtrodden: An Interview with a Dalit Agricultural Laborer.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 4 (4): 763–774.

- Osella, Caroline, and Filippo Osella. 2006. Men and Masculinities in South India. London and New York: Anthem Press.

- Pearson, Ruth. 2000. “All Change? Men, Women and Reproductive Work in the Global Economy.” The European Journal of Development Research 12 (2): 219–237. doi:10.1080/09578810008426773.

- Pineda, Javier. 2000. “Partners in Women‐Headed Households: Emerging Masculinities?” The European Journal of Development Research 12 (2): 72–92. doi:10.1080/09578810008426766.

- Planning Department, Government of Maharashtra. 2013. Report of the High Level Committee on balanced regional development issues in Maharashtra. Planning Department, Government of Maharashtra.

- Preibisch, Kerry L., and Evelyn Encalada Grez. 2010. “The Other Side of El Otro Lado: Mexican Migrant Women and Labor Flexibility in Canadian Agriculture.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35 (2): 289–316. doi:10.1086/605483.

- Rai, Pronoy. 2018. “The Labor of Social Change: Seasonal Labor Migration and Social Change in Rural Western India.” Geoforum 92: 171–180. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.04.015.

- Rai, Pronoy, and Thomas A. Smucker. 2016. “Empowering through Entitlement? The Micro-Politics of Food Access in Rural Maharashtra, India.” Journal of Rural Studies 45: 260–269. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.04.002.

- Rai, Pronoy. 2013. The Indian State and the Micropolitics of Food Entitlements. Athens, OH: Ohio University Master’s Thesis.

- Ramamurthy, Priti. 2000. “The Cotton Commodity Chain, Women, Work and Agency in India and Japan: The Case for Feminist Agro-Food Systems Research.” World Development 28 (3): 551. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00137-0.

- Rogers, Martyn. 2008. “Modernity, ‘Authenticity’, and Ambivalence: Subaltern Masculinities on a South Indian College Campus.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14 (1): 79–95. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00479.x.

- Scott, Joan Wallach. 1988. Gender and the Politics of History. New York: Columbia University Press. doi:10.1086/ahr/95.4.1156-a.

- Silvey, Rachel. 2006. “Geographies of Gender and Migration: Spatializing Social Difference.” International Migration Review 40 (1): 64–81. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00003.x.

- Silvey, Rachel. 2004. “Power, Difference and Mobility: Feminist Advances in Migration Studies.” Progress in Human Geography 28 (4): 490–506.

- Srivastava, Ravi. 2012. Internal Migration in India: An Overview of Its Features, Trends, and Policy Challenges. Workshop Compendium Volume II. New Delhi: UNICEF and UNESCO.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2009. Human Development Report. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vasavi, Aninhalli R. 2009. “Suicides and the Making of India’s Agrarian Distress.” South African Review of Sociology 40 (1): 94–108. doi:10.1080/21528586.2009.10425102.

- Vigoya, Mara Viveros. 2001. “Contemporary Latin American Perspectives on Masculinity.” Men and Masculinities 3 (3): 237–260. doi:10.1177/1097184X01003003002.

- Walker, Gregory Wayne. 2006. “Disciplining Protest Masculinity.” Men and Masculinities 9 (1): 5–22. doi:10.1177/1097184X05284217.

- Whitson, Risa. 2010. “The Reality of Today Has Required Us to Change”: Negotiating Gender through Informal Work in Contemporary Argentina.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100 (1): 159–181. doi:10.1080/00045600903379059.

- Wilton, Robert, Geoffrey DeVerteuil, and Joshua Evans. 2014. “‘No More of This Macho Bullshit’: Drug Treatment, Place and the Reworking of Masculinity.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 39 (2): 291–303. doi:10.1111/tran.12023.