Abstract

Based on original survey data, this essay analyses the political attitudes of individuals displaced by the war in eastern Ukraine. We systematically compare attitudinal differences and similarities along three axes: the displaced relative to the resident population; the displaced in Ukraine relative to the displaced in Russia; and the displaced from the (non-)government-controlled areas relative to the resident population in the (non-)government-controlled areas of Donbas. This fine-grained comparative analysis highlights the variety of attitudes held by the displaced, similarities in attitudes across displacement locations, and the effect of war casualties on attitudes and self-declared political interest.

War and displacement fundamentally disrupt people’s everyday lives. These disruptions are likely to shape attitudes and behaviour, but social scientists tend to lack the data to study the attitudes of those who are most directly affected by war. Beyond a focus on the needs, health and rights of the displaced, or their views on issues directly related to the war—for example, their self-reported identities and perspectives on inter-group relations or proposals for peace—we lack a good understanding of the views of these individuals on a wider range of political issues. What do people experiencing war and displacement think of democracy or the direction their country is headed in, and how interested are they in politics in general? Including these issues in the discussion prevents us from reducing the people exposed to war and displacement to these experiences. Painting a fuller picture of their attitudes also provides us with an insight into some of the more long-term political challenges linked to war and displacement.

Since the start of the war in Donbas in 2014, Ukraine has become one of the countries with the highest number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) worldwide. Additionally, the war has generated significant external displacement, mostly to the Russian Federation. These individuals are not simply objects of humanitarian aid or social policy, and they do not represent a community characterised, above all, by the experience of displacement. In this essay, we explore the self-reported levels of political interest, support for democracy, and foreign policy preferences of the internally and externally displaced from Donbas.

Our analysis is based on original cross-sectional survey data (2016) that cover the resident population of both the government- and non-government-controlled areas of the Donbas region,Footnote1 the internally displaced who fled from either part of Donbas—government or non-government controlled—to other regions of Ukraine, and the externally displaced who moved from Donbas to the Russian Federation. On the basis of this four-part survey, we capture attitudes nearly three years after the onset of war.

In this essay, we systematically compare attitudinal differences and similarities along three axes: the displaced relative to the resident population; the displaced in Ukraine relative to the displaced in Russia; and the displaced from the (non-)government-controlled areas relative to the resident population in the (non-)government-controlled areas of Donbas.

More specifically, we ask the following questions: are the views of those who left either part of the Donbas region different from those who still live there? Do the views held by the internally displaced differ from the views held by the externally displaced? Do the displaced from the government-controlled areas of Donbas differ from those who still reside in this part of Donbas—and do the displaced from the non-government-controlled areas differ in their views from those who reside in these areas not currently under Kyiv’s control? In all three comparisons, the effects of personal experiences with physical violence and death are an important factor in the analysis.

The essay has three main objectives. First, it presents and analyses rare data on different sub-groups of the population most directly affected by war, thereby contributing to the discussion about the war in eastern Ukraine and the study of war and displacement more generally. Second, by focusing on political attitudes beyond identity- and war-related issues, this essay treats the displaced as fully fledged social and political actors. Third, through a systematic comparison of the displaced along three different dimensions based on the former and current locations of the displaced and the resident population in the region, this essay also makes a broader methodological contribution, insofar as it highlights the significance of different comparative reference points when analysing the views held by the displaced.

We proceed as follows: first, we frame our analysis by drawing on the literature on the war and societal cleavages in Ukraine, the wider literature on forced migration, and the comparative study of war and violence. Building on these different strands of scholarship, we generate the hypotheses guiding our analysis. We then present our survey data and research design before moving on to the discussion of our findings.

Our analysis highlights the variety of attitudes held by the displaced. The war has not had a homogenising effect on the views of the displaced. We find the biggest discrepancies in political attitudes between the displaced from the non-government-controlled areas and the resident population in this part of Donbas. The second most significant difference exists between all the displaced taken together, irrespective of their current location (Ukraine or Russia), on the one hand and the resident population of Donbas as a whole on the other hand. This result also shows that basic political attitudes do not adjust quickly to a new, potentially quite different political environment, as we can see in the case of the displaced in Russia. Lastly, across all three comparisons, we find a significant effect of personal experiences with violence irrespective of origin or current destination: such experiences are linked to a self-reported increase in political interest, but also to more sceptical views of Ukraine’s political development and the principle of democracy.

Framing the analysis

The war in eastern Ukraine

The war in Donbas began in the aftermath of the Euromaidan protests in 2013–2014 and the annexation of Crimea by Russia in early 2014, when Moscow provided political and military support for local separatists in parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasti. By August 2019, the war had cost more than 13,000 lives, including the lives of at least 3,339 civilians (OHCHR Citation2019), and effectively cut off the self-declared, Russia-backed ‘People’s Republics’ of Donetsk and Luhansk from the rest of Ukraine. The Minsk II Agreement of 2015, resulting from the negotiations by the ‘Normandy Four’ (Russia, Ukraine, Germany and France), has contained but not ended the war.

Since 2015, Ukraine has been among the ten countries with the largest IDP population worldwide, comparable in numbers to countries such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Sudan (UNHCR Citation2016a). By the summer of 2016, the Ukrainian Ministry for Social Policy had already registered close to 1.8 million internally displaced people (IDPs).Footnote2 Moreover, an estimated one million people have fled from the war zone to the Russian Federation (UNHCR Citation2016b). The displaced in Russia figure even less in Ukrainian or international media coverage or scholarly analysis. This essay takes a step towards rectifying this trend.

The effects of the war on Ukrainian politics and how Ukrainian citizens identify with the Ukrainian state have been profound. A growing number of studies are attempting to trace these effects on Ukrainian political elites, perceptions of the Ukrainian state and citizenship, and the status of the Ukrainian language (Kulyk Citation2016, Citation2018; Onuch et al. Citation2018; Onuch & Hale Citation2018; Sasse & Lackner Citation2019). There is, however, considerably less attention, both among policymakers and the scholarly community, on the individuals most directly affected by the war, that is, the residents in both parts of the currently divided Donbas region and the displaced (Sasse & Lackner Citation2018).

The displaced, by and large, remain below the radar of standard opinion polls and, if they are considered at all, it is as objects of humanitarian aid or social policy rather than as a political constituency. In Ukraine, delays in easing registration requirements in order to guarantee IDPs voting rights in national and local elections have been, at least in parts, politically motivated (Council of Europe Citation2019; Sokolova Citation2019). The displaced may not be a cohesive social or political group, but they are seen as a potential risk for incumbents at different levels of government who have failed or are seen to have failed to address their needs.

The emerging scholarly work on the displaced from Donbas has focused on contextualising the dynamics of this displacement process (Pikulicka-Wilczewska & Uehling Citation2017; Woroniecka-Krzyzanowska & Palaguta Citation2017; Kuznetsova Citation2018), the adaptation strategies of the displaced (Mikheieva & Sereda Citation2015), and processes of ‘othering’ in the identity discourse in Ukraine (Bulakh Citation2017; Ivashchenko & Stadnik Citation2017). While these studies highlight the challenges the displaced face, including the dynamics of stigmatisation, the focus generally remains on the perceptions of the displaced and the adaptation of the displaced to their current situation. What is missing, is a perspective that treats the displaced as ‘ordinary’ citizens who may be interested in politics and hold a range of different views on political principles, such as democracy, and concrete domestic and foreign policy issues. This essay builds on the initial, primarily ethnographic, scholarly impetus of restoring agency to the displaced as an amorphous community and extends it into the political sphere.

The importance of regional factors in Ukrainian domestic politics and as a factor shaping foreign policy preferences has long been recognised (Birch Citation2000; Kubicek Citation2000; Barrington Citation2002) but what exactly ‘region’ captures—ethnic, linguistic, historical, socio-economic, historical, policy cleavages, a mixture of all of these, or an additional distinctive cleavage—continues to be discussed by scholars working on contemporary Ukraine (Arel Citation1995, Citation2002, Citation2014; O’Loughlin Citation2001; Shulman Citation2004; Barrington & Faranda Citation2009; Sasse Citation2010; Frye Citation2015; Onuch et al. Citation2018; Onuch & Hale Citation2018). In particular, the distinctive regional identity of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasti has been highlighted, with reference to the historical development and socio-economic characteristics of this region, as well as its unified political outlook, at least until the Euromaidan (Osipian & Osipian Citation2006, Citation2012). We take the existence of a distinctive regional Donbas identity as a baseline for our subsequent analysis and hypothesise that the displaced from Donbas share certain norms and preferences regardless of their location.

Forced migration and internal displacement

Scholars have generally concentrated more on the host societies and their attitudes towards refugees and the effects of integration policies rather than on the views of the recently arrived. A noteworthy exception is a two-way study that combines the views of the host society on Syrian refugees and the views of the refugees about their host society (Yigit & Tatch Citation2017). When the attitudes of the displaced individuals themselves are at the centre of the empirical research agenda, four main strands of research are apparent. First, there is a large literature in the medical sciences and psychology on physical or mental health-related issues affecting the displaced and the effectiveness of policies targeting these issues.Footnote3 The second strand is a multi-disciplinary literature focusing on the refugees’ perceptions of and willingness to cooperate with integration or aid policies and rehabilitation projects; for example, Pottier (Citation1996). Third is a smaller literature, rooted in the social sciences, analysing the views of the displaced on issues related to conflict resolution; for example, property issues and physical return (Toal & Grono Citation2011). The fourth strand is social science research on the dynamics of intra- and inter-group identities and trust in the aftermath of violent conflict. This literature includes, but usually does not single out, the displaced. Instead, the main focus has been on the consequences of ethnic polarisation on voting patterns in the aftermath of war (see below).

Although the pitfalls of ‘methodological nationalism’ that equates migrant communities with ethnic groups have been recognised (Wimmer & Glick Schiller Citation2002; Glick Schiller & Çağlar Citation2009), the forcibly displaced tend to be thought of as homogenous groups, even more so than other migrants.

A long tradition of analysing patterns of assimilation or integration in the study of migration has put the emphasis on ethnic and cultural identities. Even if the discussion is widened to include a human capital dimension, identity issues tend to be prioritised over political attitudes or values (Colic-Peisker & Walker Citation2003). In his study of Sudanese refugees, Marlowe has rightly warned of the essentialising resulting from a ‘trauma-focused understanding’ of refugees and argued for ‘elevating the ordinary’ in refugees’ life trajectories (Marlowe Citation2010, pp. 183, 194).

Effectively, forced migrants are not treated as ‘ordinary citizens’ whose political preferences can be tracked. There is no a priori reason to assume that a displaced person is less interested in politics, less informed or less opinionated. On the contrary, the experience of displacement and war can be expected to shape political attitudes, including trust in political institutions, and possibly increase political interest or engagement, as politics is thrust upon the individuals concerned. Thus, we need to trace if the views of the displaced differ systematically from the population in the region they left behind.

A recent study based on original survey experiments with members of the Syrian refugee population in Turkey analysed the refugees’ attitudes about the termination of conflict (Fabbe et al. Citation2019). Here, refugee attitudes are not treated as fixed outcomes of their exposure to violence but are shown to be responsive to the framing of wartime experiences and the identity of the political actors proposing a peace agreement. Building on this logic beyond the issues of war and peace, the hypothesised malleability of the attitudes of the displaced should also manifest itself in a diversity of political attitudes among the displaced from Donbas.

Scholars have tried to understand the patterns underlying the choice to stay or to leave a setting of armed conflict and the consequences of these choices. Given that there is at least a degree of choice behind displacement and the displacement destination, the displaced from Donbas—just like migrants generally—are likely to have gone to where they can rely on existing personal or other migrant networks and where they feel relatively comfortable. Thus, we could expect the displaced who moved to the Russian Federation to hold political views more amenable to those held by Russian citizens. We hypothesise that IDPs and the displaced in Russia are exposed to different narratives about the war which, in turn, shape their political attitudes.

A hypothesis backed by quantitative and qualitative data from Colombia, for example, is that those who do not leave tend to align with the dominant group in the war zone that is capable of offering protection and they develop closer associations over time, while simultaneously exhibiting a narrower range of attitudes (Steele Citation2009). By comparison, those who leave have been found to adopt different settlement strategies (settling in clusters or hiding in more anonymous urban settings) resulting in cleavage formation (Steele Citation2009). Based on this logic, we hypothesise that those who have left Donbas, in particular, the territory of the so-called ‘People’s Republics’, differ in their attitudes compared to those who continue to reside in the region.

The study of war and political violence

The study of war has been more concerned with the causes than the consequences of war. Among the causes discussed in the comparative literature on war is the role of divisive identities. However, the effects of war on identities or the multi-directional identity transformations during and after war remain underexplored (Esteban & Schneider Citation2008; Sambanis Citation2002; Kalyvas Citation2008; Wood Citation2015). War puts the characteristics and salience of ethnic and other identities to the test and has the potential to both intensify or modify identities (Onuch et al. Citation2018). These dynamics are still poorly understood, in part due to a lack of empirical data collected during war.

There is an assumption that violent conflict hardens identities and leads to a polarisation along the conflict lines (Posen Citation1993; Gurr Citation2000; Fearon & Laitin Citation2000; Esteban & Schneider Citation2008). This line of reasoning also implies a homogenising effect within the conflicting groups which has not yet been sufficiently analysed. Empirical research on Bosnia & Hercegovina and Croatia, for example, has called this hypothesis about the polarisation of ethnic and social identities into question, showing instead that those directly involved in or affected by war do not become more ethnonationalist (Massey et al. Citation2003; Sekulic Citation2004; Dyrstad Citation2012). In the case of Ukraine, recent survey data have revealed that the experience of war can sustain or even reinforce mixed and civic identities (Sasse & Lackner Citation2018, Citation2019).

While these results caution us against assumptions about the streamlining and polarisation of identities through war, the range of attitudes analysed in war contexts has been too limited to date. We need to know more about the perceptions and political preferences studied in other crisis situations. In periods of attempted democratisation, such as the ‘colour revolutions’ in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, the analysis has naturally focused on individual-level attitudes on topics such as democracy, economic reforms and foreign policy. These issues are just as important in political contexts shaped by war. However, social science analysis still tends to reduce people living through war to carriers of identity characteristics that may or may not change as a result of the experience of violence or displacement.

Recently, scholars have focused on the effects of violent conflict on intra- compared to inter-group trust. This research suggests that the social norms shaped by violence prove resilient over long periods of time and, where they foster collective action among those affected, further undermine trust in national institutions (Grosjean Citation2014). This literature does not yet sufficiently address the time frame during which a war-induced reordering of social norms occurs and the dynamics behind the observed effects on trust.

Research on the effects of political violence on political interest and participation remains limited to date. Contrary to the findings on the detrimental effects of war on trust, several studies have shown an increase in political interest among those affected by war (Bellows & Miguel Citation2009; Blattman Citation2009; Gilligan et al. Citation2014; Oto-Peralias Citation2015). More specifically, there is also empirical evidence of IDPs exhibiting more political knowledge or political interest. Toal and Grono, for instance, found that Georgian IDPs from Abkhazia were more aware of the bigger security context of the Georgian–Abkhaz conflict than the resident Abkhaz in Abkhazia (Toal & Grono Citation2011). However, in this case, the displaced represented a distinctive ethnic group, thereby blurring the effects of displacement and ethnic cleavages. A multigenerational survey of Crimean Tatars, for example, traced a long-lasting correlation between displacement (and the memory of displacement) and a higher level of political engagement (Lupu & Peisakhin Citation2017). In our survey analysis, we use the self-declared increase or decrease in political interest as a baseline measure for the mobilisation hypothesis suggested by existing research.

Most of the literature on displacement and war deals with conflictual relations between ethnic groups. Instead, in the case of Ukraine, we are tracing similarities and differences within one reference group: the residents of Donbas region, who are characterised by a diversity of ethnic and linguistic characteristics and a sense of regional identity. Thus, in our case, the variation in attitudes is not centred on ethnic groups and inter-ethnic relations. Instead, we are opening up a different perspective on displacement and its aftermath.

In sum, our analysis of the political attitudes of the displaced from Donbas starts from the role of regional factors in Ukrainian politics. Based on a critical reading of the literature on displacement and its apparent gaps, our analysis is guided by the assumption of a diversity of political attitudes among the displaced. From the study of war and political violence, we consider the inconclusive evidence about the polarisation of identities during or after war. Our cross-sectional data do not allow a comparison of pre- and post-war attitudes, but the four interlinked surveys allow for a closer look at ‘sub-groups’ of the displaced and the resident population and potential patterns in their political views. From the literature on war and political violence, we learn that war is correlated with low trust in political institutions but, also, that war and displacement can have a mobilising effect, boosting political interest and participation.

We generate three concrete hypotheses for our analysis. First, that those who left their homes in Donbas region differ in their political attitudes from those who still reside in the region. Second, that individuals leaving the region of war either choose their destination, based on their attitudes and preferences, or re-socialise into the predominant set of attitudes at their destinations. Thus, we hypothesise that a different destination of displacement (Ukraine or Russia) is mirrored in different political attitudes. Third, we further differentiate between the two parts of Donbas—government and non-government controlled—and the displaced from these two areas and hypothesise, first, that those who fled the non-government-controlled areas differ in their views from those who continue to reside in those territories and, second, that those who fled the government-controlled areas differ significantly in their attitudes from those who still reside there. The effect of a personal experience of violence is traced in connection with each of the three hypotheses.

Data and research design

Opinion polls in Ukraine are currently not truly ‘nationally representative’. The displaced are harder to reach through standard sampling methods, and the population in the non-government-controlled areas of Donbas and Crimea have been dropped from standard country-wide surveys (KIIS Citation2019). Going against this trend, our analysis is based on original survey data on four different populations: internally displaced people in Ukraine; displaced people from Ukraine residing in the Russian Federation; the resident population of Kyiv-controlled Donbas; and the resident population of the non-government-controlled territories.

Collecting data on displaced individuals is a challenging task. Large-n data are by and large absent. The wider literature on displacement refers to a range of unconnected case studies, often based on a small number of interviews or participant observation. These types of data contain a wealth of information about particular individuals and their living conditions, but it is hard to judge whether they are representative of the larger group of IDPs in a particular setting, or to compare them across cases.Footnote4

Our surveys contribute to building a base of quantitative data on displacement. They include IDPs in Ukraine (n = 999) and individuals who fled to Russia (n = 1,007). The survey was implemented by R-Research in the period 1–18 December 2016 among registered displaced persons and persons who were providing for themselves and their families independently without registering their status.Footnote5 The survey of IDPs covered six oblasti in Ukraine, among them those with the highest concentration of registered IDPs, namely Donetsk and Luhansk oblasti (from both the government- and non-government-controlled regions), Kharkiv Oblast’ (accounting for 60% of the sample), Dnipropetrovsk Oblast’ as a further region bordering the conflict, Kyiv City and Kyiv Oblast’, and Lviv Oblast’. The quota sampling was based on official data on the profile of the IDPs; the majority were middle-aged and about two-thirds were women.Footnote6 The survey among the displaced in Russia covered Moscow city and 11 western and central oblasti with known concentrations of the displaced.Footnote7 In the absence of information on the displaced in Russia, the quotas were aligned with the IDP sample. A priori there was no reason to believe that the profile of the internally and externally displaced would vary significantly.Footnote8

Two further surveys conducted at the same time in the government-controlled areas and the non-government-controlled areas helped to contextualise the data on the displaced. The resident population in the two parts of Donbas provided a comparative baseline in our analysis of attitudes.

The two surveys in Donbas were implemented by R-Research in the period 1–15 December 2016. In Kyiv-controlled Donbas, face-to-face interviews were conducted based on a multi-stage quota sample (n = 1,200 split evenly between Donetsk and Luhansk oblasti). The sample was aligned with the age, gender and educational attainment quotas of the urban and rural populations as recorded in official state statistics from 2016.Footnote9 In the absence of reliable official data on the occupied territories, the same quotas were applied to the non-government-controlled areas. Due to the difficulties of access and ethical considerations, a shorter telephone survey was carried out in the non-government-controlled areas (n = 1,200) rather than face-to-face interviews.Footnote10

Dependent variables

All dependent variables were derived from survey items concerned with attitudes towards democracy and foreign policy, the respondents’ interest in politics and their satisfaction with the general development of Ukraine.

Attitudes towards democracy were measured by asking respondents whether or not they agreed with the statement, ‘Democracy is the best form of government’. Five answer categories were given (1 = strongly agree; 2 = somewhat agree; 3 = neither agree nor disagree; 4 = somewhat disagree; 5 = strongly disagree). For the purposes of our analysis, the middle category ‘neither agree nor disagree’ was considered to be conceptually close to a ‘don’t know’ answer and recoded to a missing value. A dummy variable was created by combining the two answer categories signalling agreement (1) and the two categories signalling disagreement (0) respectively.

Foreign policy attitudes were measured by two items regarding the respondent’s opinion on whether Ukraine should join the European Union (EU) and, in order to tap into security perceptions, whether Ukraine should remain a neutral country (as opposed to joining NATO). These items were based on yes/no answers (1 = yes; 2 = no), and both were recoded as dummy variables (1 = yes; 0 = no).

Interest in politics was measured by the respondents’ self-reported level of interest in politics compared to three years ago (1 = more interested; 2 = the same; 3 = less interested). This variable was recoded as a dummy variable (1 for all respondents who answered that they were now more interested in politics, and 0 for all other respondents).

Attitudes regarding Ukrainian internal developments were captured by the standard question of whether developments in the country were headed in the right or wrong direction (1 = right direction; 2 = wrong direction). This variable was recoded to a dummy variable (1 = right direction; 0 = wrong direction).

Independent variables

The datasets relating to the four sub-groups included in our analysis (IDPs, the displaced in Russia, residents in Kyiv-controlled Donbas and residents of the non-government-controlled areas) were merged into one dataset. Subsequently, individual datasets on the sub-groups were used as independent variables in order to explore similarities and differences in the attitudes across sub-groups and locations.

Hypothesis 1 was concerned with the question of whether the individuals displaced from both parts of Donbas differed from the resident population in Donbas. A dummy variable was created to compare the entire displaced population with the resident population of the Donbas region as a whole. The displaced in Russia and Ukraine correspond to the value 1 on this variable; people who resided in Donbas have the value 0.

In the second round of the analysis, we tested the second hypothesis on potential differences in the attitudes between people who had fled to Russia and people who were displaced within Ukraine. The main independent variable in this model was a dummy variable comparing IDPs to the displaced in Russia (1 = displaced in Russia; 0 = displaced in Ukraine).

For our third analysis, testing the two elements of our third hypothesis, we examined commonalities and differences between the displaced and the resident population in more detail: the displaced both in Ukraine and in Russia were categorised according to whether they had come from Kyiv-controlled Donbas or from the territory of the DNR/LNR. Then, two variables were generated as the main independent variables: the first compared the displaced who came from the DNR/LNR with the resident population in the DNR/LNR (1 = displaced from DNR/LNR; 0 = DNR/LNR); the second variable compared the displaced from government-controlled Donbas with the resident population in government-controlled Donbas (1 = displaced from government-controlled Donbas; 0 = government-controlled Donbas).

If the respondents themselves had suffered injury or if they know people who were injured or killed during the war, this experience could have an impact on their stance regarding Ukrainian politics, democracy in general, or the country’s foreign and security policy. In the survey, respondents were asked whether they or their immediate family had suffered directly as a result of the war in Donbas. Furthermore, respondents were asked if they personally knew somebody who had suffered directly as a result of the war. Both items had yes/no answer categories (1 = yes; 2 = no) and both were transformed into dummy variables (1 = yes; 0 = no).

Various standard socio-demographic controls were included in our analysis. Age was introduced as a continuous variable, starting at the age of 18. As for gender, all male respondents were coded 1 and all female respondents were coded 0. The level of education was measured using a categorical variable ranging from 1 (primary education) to 9 (completed graduate degree). This variable was recoded as a dummy variable with the value 1 for all respondents scoring 6 or higher on the original variable and 0 for all respondents with a value below 6.

A variable was generated to display the respondent’s position on an income ladder. The income variable in each dataset was sorted and cut into ten equally sized groups, labelled from 1 to 10 in the newly generated variable ‘income quantile’. A respondent with the value 10 on this variable belonged to the 10% at the top of the income hierarchy among the respondents across all four datasets. The employment status was measured using a categorical variable with 12 categories, including, among others, full-time and part-time work, maternity leave, and unpaid leave. A dummy variable was generated by coding all respondents who were either in full-time or part-time employment as 1, and all others as 0.

Urban and rural locations were differentiated based on the dummy variable ‘urban’, recoding the original response categories ‘city/town’ and ‘urban-type settlement’ as 1, and ‘rural’ as 0. Lastly, at the time of the survey, three religious denominations were identified as the dominant ones across all four datasets: Orthodox—Kyiv Patriarchate; Orthodox—Moscow Patriarchate; and Atheism. Three different dummy variables were generated, one for each denomination. For example, for the variable ‘orthodox_Kyiv’, all followers of the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate were coded 1, and followers of any other confession were coded 0. The other two dummy variables were coded following the same logic.

Analytical strategy

Below we first present the descriptive statistics for the dependent variables in each of the four datasets. We then investigate the differences between the four populations by comparing them in a series of regression models. Since all dependent variables were coded as dummy variables, logistic regression models (maximum likelihood) were applied. Independent variables were introduced in two steps to investigate possible overlaying effects. The regression results are reported as odds ratios.

Findings

Descriptive statistics

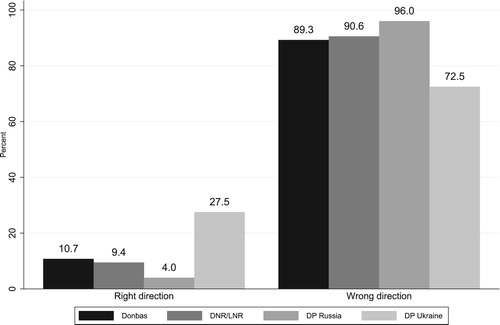

displays the descriptive statistics from all four datasets for the views on the statement ‘Democracy might have its problems, but it is still the best form of government’.

Figure 1. Democracy is the Best Form of Government

Note: Donbas: n = 972; DNR/LNR: n = 1,136; DP Russia: n = 931; DP Ukraine: n = 933.

A minority of respondents in all four populations disagreed with the statement; between about 40 and 60% of the respondents either ‘strongly’ or ‘somewhat’ agreed. Thus, people in and from the Donbas region tended to agree that democracy is indeed the best form of government. Yet, there was also a significant degree of insecurity, as around a third of each respective group positioned themselves in the category ‘neither agree nor disagree’. Furthermore, the resident population in the government-controlled areas and the DNR/LNR were more likely to disagree with the statement than the displaced. This finding indicates either that the daily experience of war informs a more sceptical attitude towards the democratic system as such, or that people who value democracy were more likely to flee from the non-government-controlled areas.

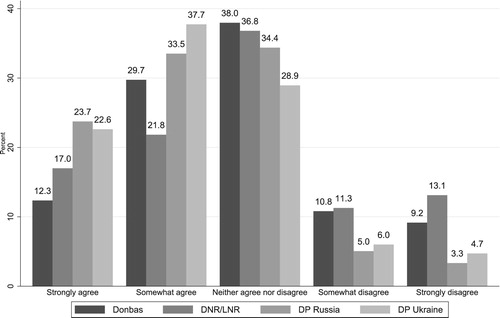

sums up the responses to the question of whether Ukraine should join the EU. At first glance, there is an apparent difference between the IDPs and all other groups: more than half of the IDP respondents (55%) agreed with the statement that Ukraine should join the EU, but only about one third (government-controlled Donbas), one fifth (DNR/LNR) and one seventh (displaced in Russia) of the respondents voiced their support for EU membership. Thus, the IDPs stand out as the sub-population with the most pronounced pro-EU views. It is possible that they already held those views prior to their displacement, but they may also have developed them in the course of their relocation. Their pro-EU view marks a clear contrast to the rest of the respondents: a clear majority in government-controlled Donbas (72%) disagreed with the statement about Ukraine joining the EU, and more than 80% of DNR/LNR residents and the displaced in Russia rejected this idea.

Figure 2. Ukraine Should Join the European Union

Note: Donbas: n = 867; DNR/LNR: n = 1,063; DP Russia: n = 838; DP Ukraine: n = 795.

displays the descriptive results for the question of whether Ukraine should remain neutral rather than joining NATO. Among the resident population, around 40% disagreed and 60% agreed with the statement that Ukraine should remain a neutral country. The displaced population was rather evenly split between those in favour of and against neutrality. Overall, the stronger wish in the DNR/LNR and government-controlled Donbas to remain neutral may be rooted in the wish to bring an end to the fighting and avoid future conflict.

Figure 3. Ukraine Should Remain Neutral

Note: Donbas: n = 872; DNR/LNR: n = 1,031; DP Russia: n = 755; DP Ukraine: n = 772.

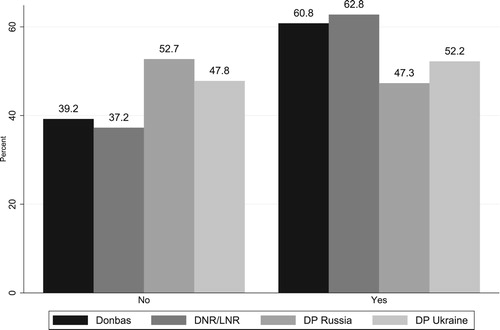

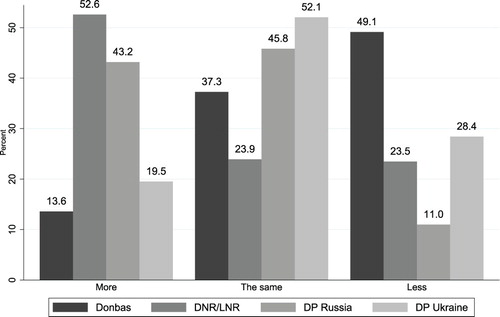

The survey tapped into the changes in people’s interest in politics by asking respondents whether they were more or less interested in politics compared to 2013, i.e. the time before the war. shows that all four populations differed significantly in their responses to this question. In government-controlled Donbas, the majority (49%) said that they were less interested in politics than three years ago, and only 14% stated that they had become more interested. Conversely, people living in the DNR/LNR had become much more interested in politics (53%). Most of the displaced in Russia said that they had become more interested—or were at least as interested as before the war. Only 11% reported becoming less interested over time. The IDPs in Ukraine were similar to the resident population in government-controlled Donbas: a third reported being less interested than before the war, while the majority (52%) was as interested as before, and 20% said that they were now more interested in politics than in 2013. As the question asks about a self-reported change in interest rather than the level of interest, it captures a newly mobilised political awareness. Thus, those not reporting a change could still have been interested in politics before 2013.

Figure 4. Interest in Politics Compared to 2013

Note: Donbas: n = 1,111; DNR/LNR: n = 1,167; DP Russia: n = 984; DP Ukraine: n = 943.

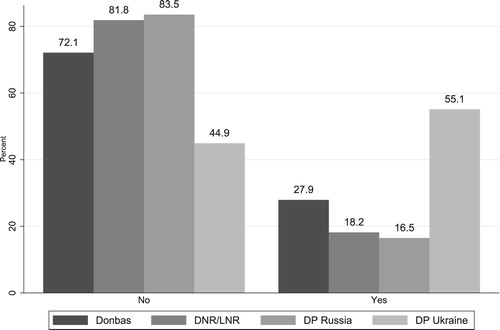

displays the descriptive statistics for the question ‘Are developments in Ukraine going in the right or wrong direction?’. A clear majority said that Ukraine’s overall direction was wrong: 90% in government-controlled Donbas and the DNR/LNR, and 96% in the population of displaced people in Russia. Only the IDPs displayed a different attitude: almost a third (28%) said that the developments in Ukraine were headed in the right direction, suggesting that a proportion of the IDPs felt at least sufficiently removed from the war zone or integrated into their new locations to appreciate the direction of Ukrainian domestic developments.

Regression analysis

In order to test our first hypothesis, we compared both groups of displaced people with both groups of the resident population in Donbas as a whole. We then tested our second hypothesis by comparing the displaced in Russia with the IDPs in Ukraine. Lastly, we tested our third hypothesis by comparing the displaced people from the DNR/LNR with the resident DNR/LNR population, and the displaced from Kyiv-controlled Donbas with the resident population in this part of Donbas. In the following section, only the significant regression results are discussed. All regression results are reported as odds ratios.

Analysis 1: displaced people compared to resident population in Donbas

Our logistic regression analysis shows that the displaced people in Ukraine and Russia (taken together) differed significantly in almost all aspects (in four out of the five questions) from the resident population in the Donbas region as a whole (see ).

TABLE 1 Analysis 1: Displaced People Compared to Resident Population

Irrespective of their current location, the displaced differed significantly from the resident population with regard to their attitudes towards democracy: a displaced person was 2.7 more times more likely to say that democracy is the best form of government than a resident of Donbas. Irrespective of whether a respondent was displaced or not, ‘men were 38% less likely to agree than women’, and the more highly educated and the employed were 1.3 times more likely to say that democracy is the best form of government.

With regard to the question of whether Ukraine should join the EU, above showed a similar distribution for the displaced in Russia and the resident population in Donbas and the DNR/LNR, while IDPs came out more strongly in favour of Ukraine joining the EU. Taking both displaced groups together, they were 1.7 times more likely than the resident population to agree that Ukraine should join the EU. For both the displaced and the resident population, knowing someone who had suffered during the war reduced the chances of a respondent saying that Ukraine should join the EU by 25%. Furthermore, followers of the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate were almost 100% more likely than all other religions to agree with the proposition that Ukraine should join the EU, while followers of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate were about 50% less likely to agree.

The descriptive statistics suggested that the displaced were more sceptical of Ukraine remaining a neutral country (see ). This trend was confirmed in the regression analysis: the displaced were 31% less likely to agree with neutrality, compared to the resident population in the two parts of Donbas taken together. Additionally, irrespective of displacement, people living in an urban environment were 25% less likely to agree with the statement that Ukraine should remain neutral, and followers of the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate were 27% less likely.

showed that the four groups were rather diverse with regard to their self-reported change of interest in politics. Yet, the regression analysis suggests that the resident population of both parts of Donbas, taken together, had a higher propensity than the displaced to say that they were more interested in politics than in 2013. Overall, having a family member or knowing someone who had suffered during the war significantly increased the chances that an individual would become more interested in politics (by 55% and 96% respectively). The key finding here is the effect of war casualties on political interest. The differentials in the effects may result from the fact that the emotional experience of someone close being affected might also be accompanied by a sense of frustration or resignation and thereby dampen the mobilising effect somewhat.

In line with general expectations about education being correlated with political interest, more highly educated individuals had a 33% higher chance of reporting an increase in the level of political interest. For each income quantile, the chances of being more interested in politics than in 2013 were increased by 3%.

above showed that IDPs had a higher propensity than all other groups to say that developments in Ukraine were going in the right direction. Yet, both groups of the displaced, taken together, did not differ significantly in this regard compared to the resident population. Again, several other factors had an impact for both the displaced and the resident population in Donbas as a whole: having a family member or knowing someone who had suffered during the war decreased the likelihood of saying that the direction was right by 30–35% respectively. A higher education level increased the chances by 46%, and for each income quantile, a respondent was 9% more likely to agree with the direction of the developments in Ukraine. Conversely, being a follower of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate reduced this likelihood by 38%, compared to all other religious denominations.

Summarising the differences in political attitudes between all the displaced on the one hand and the resident population of two parts of Donbas taken together, it can be said that the displaced seemed generally more westward- or EU-oriented than the resident population. The displaced exhibited a stronger belief in democracy as a principle, and they were more likely to say that Ukraine should join the EU. This may be a surprising result, especially for the displaced in Russia, both because either a conscious move towards Russia or subsequent socialisation could be linked to anti-Western views. It is possible that those who had fled the warzone held stronger democratic beliefs in the past, but displacement may also serve as a way to preserve a belief in democracy. The daily experience of war, by contrast, may undermine the hopes placed in the idea of democracy.

With regard to the question on neutrality, the displaced were less inclined to say that Ukraine should stay neutral. Thus, it seems that neutrality was a more pressing issue for those with first-hand experience of the ongoing war. Lastly, the analysis shows that some socio-demographic factors, in particular education and income, remain important predictors even in a crisis situation.

In sum, our first hypothesis can be confirmed: with the exception of one item (the question on the direction of the developments in Ukraine), the displaced differed significantly from the resident population in all investigated aspects. Thus, in spite of the fact that the populations considered had been socialised in the same region with its distinctive profile, there were significant differences between the displaced and the resident population. These attitudinal differences may either have resulted from the displacement, or they may have been a factor informing people’s displacement in the first place.

Lastly, the personal experience of violence was clearly linked to a higher level of political interest and more sceptical views on Ukraine’s domestic politics and EU integration, thereby highlighting one powerful causal mechanism behind the effects of war.

Analysis 2: displaced people in Russia compared with IDPs in Ukraine

Analysis 2 tests our second hypothesis by comparing the displaced people in Russia with the IDPs in Ukraine. In three of the five questions asked, the displaced in Russia differed significantly from the IDPs, namely with regard to whether Ukraine should join the EU, whether the level of a respondent’s interest in politics had changed, and whether Ukraine was headed in the right direction.

The regression results (see ) show that the displaced in Russia did not differ significantly from the internally displaced in Ukraine with regard to the question of whether or not democracy is the best form of government. Irrespective of the displacement location, gender and socio-economic factors matter: men were less likely to see democracy as the best form of government, while those in employment were significantly more likely to say that it was.

TABLE 2 Analysis 2: Displaced People in Russia Compared to Internally Displaced People

In line with the descriptive statistics in , we found that the displaced in Russia were 85% less likely than the IDPs to agree with the statement that Ukraine should join the EU. In both groups, this also held for those with family members who had suffered from the war: here the odds of saying that Ukraine should join the EU were 31% lower compared to people without this personal experience. Of the controls, being in a higher income category, being a follower of the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate and being an atheist all increased the chances that a respondent would favour EU membership, while living in an urban environment decreased the odds.

With regard to the question on whether or not Ukraine should remain neutral, respondents in Russia did not differ significantly from respondents in Ukraine. Yet, across both groups of the displaced, those who knew somebody who had suffered during the war had a 48% higher chance of saying that Ukraine should remain neutral. People living in an urban area were less likely to say that Ukraine should remain neutral.

shows different distributions for all four populations with regard to whether their interest in politics had changed since before the war. The displaced in Russia were four times as likely as the IDPs to say that they were more interested in politics than before 2013. Across both groups, having family members who had suffered during the war increased the chances of reporting a higher interest in politics by about 94%. A higher education level increased the likelihood by 48%, and moving up in the income hierarchy to the next highest category increased the likelihood by about 9%.

The descriptive statistics above show the IDPs to be more optimistic about developments in Ukraine. This trend was confirmed in the regression analysis: the displaced in Russia were significantly less likely than the displaced in Ukraine to say that the developments in Ukraine were headed in the right direction. Across both groups, a respondent who either had family members or knew someone who had suffered as a result of the war was less likely to approve of Ukraine’s domestic developments (reduced by a factor of 0.5). Higher education and income levels increased the likelihood of saying that the direction was right. Living in an urban environment decreased those odds, possibly capturing a greater awareness of being worse off than one’s neighbours.

While our first analysis revealed a stronger belief in democracy among the displaced compared to the resident population in Donbas, our second analysis demonstrates that neither sub-group of the displaced differed in their attitude towards democracy. Thus, irrespective of the displacement destination, the displaced either already held or have developed a stronger belief in democracy compared to the resident population in Donbas.

It is perhaps not surprising that the displaced in Russia were less likely to say that Ukraine should join the EU, given the prevalent anti-Western official discourse surrounding them. Yet, our first analysis showed that both displaced groups, taken together, supported Ukraine’s EU membership aspirations more than the resident population in Donbas. Thus, while the displaced in Russia showed less support for the idea of EU membership than the IDPs, all the displaced, taken together, were still more supportive of EU-membership than the resident population of Donbas. The daily reality of the war and the perceived inability of international actors like the EU to end the war can be expected to shape these attitudes.

Analysis 1 indicates that the displaced were significantly less likely than the resident population of Donbas region as a whole to say that Ukraine should stay militarily neutral, but no significant difference could be found between the IDPs and the displaced in Russia in this regard. Thus, either displacement in itself, or proximity to the war, seem to inform the views on neutrality or alignment with military alliances, rather than the actual displacement location.

Analysis 2 demonstrates that the displaced in Russia were more likely than the IDPs to say that they were more interested in politics than before the war. This result needs to be considered alongside the previous analysis that did not distinguish the displaced by location: in general, displaced individuals were less likely to say that they had become more interested in politics.

While the resident population and the displaced did not differ significantly in their views on the overall direction of Ukraine’s development, the displaced in Russia exhibited a stronger tendency than the IDPs to say that Ukraine was heading in the wrong direction. Thus, the daily experience of war in the DNR/LNR and government-controlled Donbas, as well as the experience of displacement, seemed to be reflected in the evaluations of the current state of Ukraine’s development. A pre-existing sceptical view may have informed the choice of destination, if indeed a choice existed, or the perspective gained while being in Russia may have resulted in increased scepticism about Ukraine’s overall direction.

A self-reported increase in the level of political interest among the displaced in Russia, which could refer to both Ukrainian and Russian politics, seems to go hand in hand with a sense of disappointment about or opposition to the overall direction of politics in Ukraine.

Overall, our second hypothesis is partly confirmed: the displaced in Russia and the IDPs in Ukraine differed with regard to three out of the five questions. Moreover, personal experience of war injuries and death was linked to more sceptical views on Ukraine’s internal development, its westward orientation and an increase in political interest.

Analysis 3: comparison by the origin of the displaced

Building on the previous analyses, we also wanted to know whether the origin of the displaced mattered in attitudinal patterns. Thus, in our next step, we tested our third hypothesis by comparing displaced people from the DNR/LNR with the resident population in the DNR/LNR, and displaced people from government-controlled Donbas with the resident population in this part of the region. In our survey, 65% of the displaced in Russia said that they had come from the DNR/LNR, 12% from government-controlled territory and 23% from other places. Of the internally displaced, 91% had come from the DNR/LNR and 9% from Kyiv-controlled Donbas. Our data revealed that the displaced from the DNR/LNR differed from those who resided in the DNR/LNR in all the political attitudes investigated here (see ).

TABLE 3 Analysis 3A: Displaced People from DNR/LNR Compared to Resident Population in DNR/LNR

Displaced individuals from the DNR/LNR were 3.5 times more likely than the population of the DNR/LNR to believe that democracy is the best form of government. The only socio-demographic variable with a significant effect in both groups was gender, with men being less likely than women to agree that democracy is the best form of government. With respect to Ukraine’s foreign policy orientation, the displaced from the DNR/LNR were 2.5 times more likely to support Ukraine’s EU membership compared to the population of the DNR/LNR. Across both groups, those who knew somebody affected by the war had significantly lower odds of favouring EU membership.

A higher education level increased the chances of believing that Ukraine should join the EU by 31%. Religion also mattered: followers of the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate were 74% more likely than all other denominations to agree with the statement about EU membership, while the followers of the Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate were less likely to agree. When asked whether Ukraine should remain neutral, the displaced from the DNR/LNR had a lower chance of agreeing with the statement compared to the resident population of the DNR/LNR. Here no other independent variable displayed a significant effect.

As for the question about being interested in politics, the displaced from the DNR/LNR were significantly less likely than the resident population to say that they were now more interested in politics than three years ago. On the other hand, having a family member who had suffered because of the war increased the odds of respondents being more interested in politics by almost 38%. Moreover, wealthier respondents were slightly more likely to report an increase in their interest in politics.

The displaced from the DNR/LNR were 95% more likely to believe that the general direction of the developments inside Ukraine was right, compared to the resident population in the DNR/LNR. The odds significantly decreased across both groups once a respondent had a family member or knew somebody who had suffered as a result of the war. By comparison, the more highly educated and the wealthier a respondent, the more likely they were to think that developments in Ukraine were headed in the right direction.

To what extent is the origin of the displaced a significant factor in explaining variation in the political attitudes? First, let us recall that, irrespective of the displacement destination, the displaced in general held a stronger belief in democracy than the resident population of Donbas (Analysis 1). This trend also holds when comparing the displaced from the DNR/LNR with the resident population in the DNR/LNR. Thus, irrespective of where individuals went, the displaced had a stronger tendency to say that democracy is the best form of government.

The same is true for the question about EU membership for Ukraine. The displaced from the DNR/LNR had a stronger tendency than the resident population in the DNR/LNR to favour EU membership. This also holds when comparing all the displaced taken together with the overall resident population (see Analysis 1). The only sub-group that proved less keen on this foreign policy orientation were those displaced to Russia, who were less inclined than the IDPs to agree with the idea of EU membership for Ukraine (see Analysis 2). Similarly, the displaced from the DNR/LNR were less likely to say that Ukraine should stay a neutral country compared to the resident population of the DNR/LNR. This finding is in line with Analysis 1 and 2: both displaced groups, taken together, were less positive about neutrality, and we found no difference between IDPs and those who fled to Russia.

The displaced from the DNR/LNR were less likely to say that they had become more interested in politics than the resident population in the DNR/LNR. This finding is in line with the previous result that both groups of the displaced, taken together, exhibited a weaker tendency to state an increase in political interest compared to the resident Donbas population as a whole.

The first part of our analysis shows that the resident population in Donbas and both groups of the displaced, taken together, did not differ significantly in their responses to the question as to whether developments in Ukraine were headed in the right direction, while the displaced people in Russia displayed a stronger tendency than the IDPs to say that the direction was wrong. Furthermore, the third step in our analysis demonstrates that the displaced from the DNR/LNR were more likely to approve of Ukraine’s internal developments compared to the resident DNR/LNR population. Thus, both the destination and the origin of displacement were found to be linked to different perceptions of the current situation in Ukraine. The first part of our third hypothesis can therefore be confirmed, as the displaced from DNR/LNR differed from the resident population on all dimensions included in the analysis.

In a subsequent step, we tested the second part of our third hypothesis. Contrary to the trend identified above, the displaced individuals from government-controlled Donbas only differed in two out of the five questions from the resident population in this part of Donbas (see ).Footnote11

TABLE 4 Analysis 3B: Displaced People from Donbas (GCAs) Compared to Resident Population in Donbas (GCAs)

No significant difference in attitudes could be found between the resident population in Kyiv-controlled Donbas and the displaced from this part of the region with regard to the question about democracy as the best form of government. Still, across both groups, the older and the wealthier a respondent, the less likely they were to think that democracy was the best form of government. When asked about their views about EU membership, again, no significant differences could be found between the two sub-groups. Generally, men were less likely than women to favour Ukraine’s membership in the EU, while followers of the Orthodox Church of the Kyiv Patriarchate were more than twice as likely, compared to all other religious denominations, to favour the prospect of joining the EU. Furthermore, employed respondents were less likely than unemployed respondents to think that Ukraine should remain neutral.

When asked about the direction of Ukraine’s overall development, the displaced from government-controlled Donbas had a significantly lower chance than the resident population in this part of Donbas to say that the direction was right. Moving up from one quantile of the income hierarchy to the next, the chances of thinking that developments inside Ukraine were going in the right direction increased by 17%, thereby suggesting a familiar socio-economic mechanism.

The resident population in Kyiv-controlled Donbas and the displaced people from this part of the region were not found to differ significantly in their attitudes towards democracy and Ukraine’s foreign policy, whether on EU membership or staying neutral. Yet, the displaced from government-controlled Donbas were around 2.5 times more likely than the resident population in this part of Donbas to say that they were more interested in politics than before 2013. This is contrary to the results for the DNR/LNR: here, the displaced were less likely than the resident population to say that they had become more interested in politics. These results mirror the differentials in the severity of the war-related experiences, with the resident population in the DNR/LNR being most directly affected by the ongoing war. Men and individuals living in urban settings were generally more likely to report an increase in the level of political interest. By contrast, a higher income level was associated with either being less interested or reporting no change in the level of interest in politics.

Thus, the second part of our third hypothesis was confirmed in part: the displaced from government-controlled Donbas differed in two out of five items from the resident population. Once again, personal experience with war-related injury or death correlated with being more interested in politics and being more sceptical of Ukraine’s development, including its integration into Western institutions.

Conclusion

This essay has examined a range of political attitudes within and across different sub-groups of the former and current Donbas population: the displaced in Ukraine and Russia, and the resident populations in the government- and non-government-controlled areas of Donbas. The main research questions concerned the potential differences in the views held by the displaced individuals and the resident population in Donbas as well as the diversity of attitudes among the displaced, depending on their displacement destination (Russia or Ukraine).

Depending on the point of reference in each of the three comparisons presented, the different war-affected sub-groups of Donbas varied in their political attitudes. Here our analysis makes a methodological contribution to the wider study of forced migration. The attitudes of the displaced varied depending on how the data were sliced and which comparative point of reference was used. The most striking difference was found when comparing the displaced from the DNR/LNR with the resident DNR/LNR population. The two sub-groups differed significantly in all the political attitudes we investigated.Footnote12

The second strongest difference could be found in the comparison of all the displaced taken together, irrespective of whether they were currently based in Ukraine or Russia, with the resident population in Donbas as a whole: in four out of the five items, the displaced people differed from the resident population, the only point of agreement being the general direction of developments in Ukraine. The different attitudes of the displaced on the one hand and the resident population on the other suggest that displacement is associated with distinctive sets of attitudes, while the actual destination of displacement is less consequential. Whether certain pre-existing attitudes inform the decision to leave the war zone, or whether the process of displacement shapes attitudes, or whether the causal arrows point in both directions, cannot be established on the basis of our survey data, as we lack comparable data on the views of these respondents before the war. However, our data suggest that basic political beliefs do not adjust quickly to a new, quite different political environment, as we can see in the case of the displaced in Russia, who differed from IDPs in three out of five attitudinal items. Moreover, the data illustrate a diversity of attitudes in a war setting rather than a clear trend of polarisation, as implied by many scholars of war and political violence.

What are the overarching tendencies characterising the political attitudes held by the four sub-groups examined in this essay? First, the displaced displayed more ‘Western’ attitudes compared to the overall resident population. No matter where they had come from or where they were currently based, the displaced were more inclined to say that democracy was the best form of government. Furthermore, a more favourable view towards Ukraine joining the EU could be found among both displaced populations (with the displaced in Russia agreeing somewhat less with the statement about EU membership for Ukraine than IDPs). We found that military neutrality was more important to the resident population than to the displaced. The wish for political neutrality, which we regarded as shorthand for stability, appeared to be more prevalent among those who were still experiencing war as part of their daily lives.

Our data do not support the thesis about a lack of political interest in war settings. However, the question about changes in the self-reported level of political interest was the only one that showed significant differences across our three axes of comparison. The resident population in Donbas as a whole was more likely to say that it had become more interested in politics than both displaced groups taken together. When differentiating further between the sub-groups, the same pattern could be found with regard to the DNR/LNR: the current DNR/LNR population was more likely to say that it had become more interested in politics than those displaced from the DNR/LNR. The intensity of war as a daily experience seems to mobilise an interest in politics. Yet, when singling out the case of government-controlled Donbas, the reverse trend was found: the displaced from this part of Donbas had become more interested in politics compared to the resident population. Following the logic suggested above, displacement from government-controlled Donbas appears to have amounted to a bigger disruption of an individual’s life than residing in this part of the region (provided that the individual did not live too close to the so-called contact line). Further research is needed to unpack these layered responses related to self-reported increases in political interest.

With respect to whether developments in Ukraine were headed in the right direction, the displaced and the resident population in the region of war did not differ significantly from one another. Yet, we found an effect that would have been blurred had we not additionally separated the displaced according to their origin: the displaced from the DNR/LNR were more likely to say that the direction of Ukraine’s internal development was right, compared to the resident DNR/LNR population. By contrast, the displaced from Kyiv-controlled Donbas displayed a weaker tendency to say that the direction was right, compared to the resident population in the government-controlled areas. These findings underline the importance of examining sub-groups of the displaced and comparing them with different reference groups.

Our analysis also showed that some socio-demographic factors known to correlate with political attitudes—such as gender, education and income levels—remained important predictors for both political attitudes and political interest, even in the presence of other strong factors, such as the personal experience of war and displacement.

Overall, our findings amplify our call for a greater focus on the displaced as ‘ordinary citizens’ who express views on a wide range of political issues, and also point to the need to include different axes of comparison in order to contextualise political attitudes and draw out nuances among relevant sub-groups.

Throughout the essay we have avoided implying causality when our data speak to correlations. One of our independent variables, however, ties into a causal dynamic: the attitudes of a displaced or resident respondent were clearly linked to the fact of having a family member or acquaintance killed or injured. Those with first-hand experience of death and injury were shown to have become more interested in politics and to be more critical of Ukraine’s overall development, EU and NATO membership. Such experience is thus an important predictor of political interest and a range of domestic and foreign policy preferences. This result calls for further empirical research on the mobilising effects of personal war experiences that seem to cut across different sub-groups of those in and from the war region.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gwendolyn Sasse

Gwendolyn Sasse, Department of Politics and International Relations, Nuffield College, University of Oxford, New Road, Oxford OX1 1NF, UK. Director, Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS), Mohrenstrasse 60, Berlin 10117, Germany. Email: [email protected]

Alice Lackner

Alice Lackner, Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS), Mohrenstrasse 60, Berlin 10117, Germany. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 In the Tables below we use the abbreviation GCAs for the government-controlled areas of Donbas. For the sake of a clearer distinction in the Table format, we refer to the non-government-controlled areas as DNR/LNR, a reference to the self-declared, Russia-backed Donetsk and Luhansk ‘People’s Republics’. In the text we vary between ‘non-government-controlled areas’ and DNR/LNR.

2 ‘Social Policy Ministry Registers 1.786 Million IDPs’, Interfax-Ukraine, 22 June 2016, available at: https://en.interfax.com.ua/news/economic/351907.html, accessed 15 January 2020.

3 On the Ukrainian displaced see, for example, Nidzvetska et al. (Citation2017) and Roberts et al. (Citation2019).

4 See also Jacobsen and Landau (Citation2003).

5 The ratio of these two groups in the sample was as follows: 90% of registered IDPs and 10% of non-registered IDPs. The survey was conducted in the following locations: organised IDP accommodation (halls of residence, camps, hostels, modular dwellings); settings where IDPs concentrate (such as NGO offices, banks, official agencies); private homes of non-registered IDPs. All non-registered individuals were contacted using the referral method, with a registered IDP usually serving as the first contact person.

6 According to official published data, around the time of the survey, 62% of IDPs were women and 38% men. The age breakdown for the whole of Ukraine was reported as follows (September 2016): 15–24 years: 7.8%; 25–29: 14.3%; 30–34: 18.8%; 35–44: 29.9%; 45–54: 23%; 55+: 6.2% (Smal Citation2016). The actual distribution by region was not known; therefore, the ZOiS survey applied the quota to the overall sample.

7 Moscow City, Belgorodskaya Oblast’, Vladimirskaya Oblast’, Voronezhskaya Oblast’, Kaluzhskaya Oblast’, Krasnodarskii Krai, Nizhegorodskaya Oblast’, Orlovskaya Oblast’, Rostovskaya Oblast’, Samarskaya Oblast’, Tul'skaya Oblast’, Ul'yanovskaya Oblast’. The ratio between registered and unregistered refugees in the Russia sample was 56%–44%, reflecting the rate of camp closures and the more difficult access to the displaced in government-organised accommodation.

8 The widening of the regional catchment area and the necessary reallocation of interviews across regions in response to access difficulties resulted in a slight oversampling of the younger cohort of the displaced in Russia compared to the quotas based on Ukrainian IDP data.

9 ‘Population Data’, State Statistics Service of Ukraine, available at: http://ukrstat.org/en/operativ/operativ2007/ds/nas_rik/nas_e/nas_rik_e.html, accessed 7 January 2020.

10 The overall response rate in Kyiv-controlled Donbas was 41% (36% in Donetsk Oblast’ and 46% in Luhansk Oblast’). The discrepancy between the two oblasti was due to a significantly higher number of eligible households that could not be reached after three call-backs rather than the number of refusals to participate, which was equal across both oblasti. The response rate in the DNR was 17%; in the LNR, 20%. The inability to establish contact was by far the most important reason for these rates: 83% of eligible households in the DNR and 86% of eligible households in the LNR proved impossible to contact after three call-backs. Refusals by eligible households to take part accounted for only 10% of the contacts achieved in the DNR and 7% in the LNR.

11 It ought to be noted that only a smaller proportion of the displaced in our datasets came from government-controlled Donbas, which may also lead to lower statistical significance.

12 The pseudo-R-squared figures in our models are fairly low, suggesting that future analyses should include other explanatory variables and attitudes.

References

- Arel, D. (1995) ‘Language Politics in Independent Ukraine: Towards One or Two State Languages?’, Nationalities Papers, 23, 3. doi: 10.1080/00905999508408404

- Arel, D. (2002) ‘Interpreting “Nationality” and “Language” in the 2001 Ukrainian Census’, Post-Soviet Affairs, 18, 3. doi: 10.2747/1060-586X.18.3.213

- Arel, D. (2014) ‘Double-Talk: Why Ukrainians Fight Over Language’, Foreign Affairs, 18 March, available at: http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/141042/dominique-arel/double-talk, accessed 6 December 2019.

- Bakewell, O. (2008) ‘Research Beyond the Categories: The Importance of Policy Irrelevant Research Into Forced Migration’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 21, 4. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fen042

- Barrington, L. W. (2002) ‘Examining Rival Theories of Demographic Influences on Political Support: The Power of Regional, Ethnic, and Linguistic Divisions in Ukraine’, European Journal of Political Research, 41, 4. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00019

- Barrington, L. & Feranda, R. (2009) ‘Re-Examining Region, Ethnicity, and Language in Ukraine’, Post-Soviet Affairs, 25, 3. doi: 10.2747/1060-586X.24.3.232

- Bellows, J. & Miguel, E. (2009) ‘War and Local Collective Action in Sierra Leone’, Journal of Public Economics, 93, 11–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.07.012

- Birch, S. (2000) ‘Interpreting the Regional Effect in Ukrainian Politics’, Europe-Asia Studies, 52, 6. doi: 10.1080/09668130050143815

- Blattman, C. (2009) ‘From Violence to Voting: War and Political Participation in Uganda’, American Political Science Review, 103, 2. doi: 10.1017/S0003055409090212

- Braithwaite, A., Salehyan, I. & Savun, B. (2019) ‘Refugees, Forced Migration, and Conflict: Introduction to the Special Issue’, Journal of Peace Research, 56, 1. doi: 10.1177/0022343318814128

- Bremmer, I. (1994) ‘The Politics of Ethnicity: Russians in the New Ukraine’, Europe-Asia Studies, 46, 2. doi: 10.1080/09668139408412161

- Bulakh, T. (2017) ‘“Strangers Among Ours”: State and Civil Responses to the Phenomenon of Internal Displacement in Ukraine’, in Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A. & Uehling, G. (eds) Migration and the Ukraine Crisis. A Two Country Perspective (Bristol, E-International Relations).

- Castles, S. (2003) ‘Towards a Sociology of Forced Migration and Social Transformation’, Sociology, 37, 1. doi: 10.1177/0038038503037001384

- Cohen, R. (2007) ‘Response to Hathaway’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 20, 3. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fem020

- Cohen, R. & Deng, F. M. (1998) Masses in Flight. The Global Crisis of Internal Displacement (Washington, DC, Brookings Institution Press).

- Colic-Peisker, V. & Walker, I. (2003) ‘Human Capital, Acculturation and Social Identity: Bosnian Refugees in Australia’, Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 13. doi: 10.1002/casp.743

- Council of Europe (2019) Voting Rights of Internally Displaced People at Local Level Elections (Kyiv, Council of Europe Office in Ukraine), available at: https://rm.coe.int/voting-rights-of-idps-at-local-level-in-ukraine-strengthening-democrac/1680933f7e, accessed 15 January 2020.

- Davenport, C. A., Moore, W. H. & Poe, S. C. (2003) ‘Sometimes You Just Have to Leave: Domestic Threats and Forced Migration, 1964–1989’, International Interactions, 29, 1. doi: 10.1080/03050620304597

- Dyrstad, K. (2012) ‘After Ethnic Civil War: Ethno-Nationalism in the Western Balkans’, Journal of Peace Research, 49, 6. doi: 10.1177/0022343312439202

- Esteban, J. & Schneider, G. (2008) ‘Polarization and Conflict: Theoretical and Empirical Issues’, Journal of Peace Research, 45, 2.

- Fabbe, K., Hazlett, C. & Sınmazdemir, T. (2019) ‘A Persuasive Peace: Syrian Refugees’ Attitudes Towards Compromise and Civil War Termination’, Journal of Peace Research, 56, 1. doi: 10.1177/0022343318814114

- Fearon, J. D. & Laitin, D. D. (2000) ‘Violence and the Social Construction of Ethnic Identity’, International Organization, 54, 4. doi: 10.1162/002081800551398

- Frye, T. (2015) ‘What Do Voters in Ukraine Want? A Survey Experiment on Candidate Ethnicity, Language, and Policy Orientation’, Problems of Post-Communism, 62, 5. doi: 10.1080/10758216.2015.1026200

- Gilligan, M. J., Pasquale, B. J. & Samii, C. (2014) ‘Civil War and Social Cohesion: Lab-in-the-Field Evidence from Nepal’, American Journal of Political Science, 58, 3. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12067

- Glick Schiller, N. & Çağlar, A. (2009) ‘Towards a Comparative Theory of Locality in Migration Studies’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35, 2. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.723253

- Grosjean, P. (2014) ‘Conflict and Social and Political Preferences: Evidence from World War II and Civil Conflict in 35 European Countries’, Comparative Economic Studies, 56, 3. doi: 10.1057/ces.2014.2

- Gurr, T. (2000) Peoples Versus States. Minorities at Risk in the New Century (Washington, DC, United States Institute of Peace Press).

- Hale, H. E. (2010) ‘Ukraine: The Uses of Divided Power’, Journal of Democracy, 21, 3. doi: 10.1353/jod.2016.0035

- Harrell-Bond, B. & Voutira, E. (2007) ‘In Search of “Invisible” Actors: Barriers to Access in Refugee Research’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 20, 2. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fem015

- Hathaway, J. C. (2007) ‘Forced Migration Studies: Could We Agree Just to “Date”?’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 20, 3.

- Holdar, S. (1995) ‘Torn between East and West: The Regional Factor in Ukrainian Politics’, Post-Soviet Geography, 36, 2. doi: 10.1080/10605851.1995.10640982

- Ivashchenko-Stadnik, K. (2017) ‘The Social Challenge of Internal Displacement in Ukraine: The Host Community’s Perspective’, in Pikulicka-Wilczewska, A. & Uehling, G. (eds) Migration and the Ukraine Crises. A Two Country Perspectives (Bristol, E-International Relations).