Abstract

Why do citizens in democratic states allow governments to monitor them? Studies note that consent to surveillance to a large extent depends on trust in public institutions. But how is surveillance legitimised in states where this kind of trust is low, as in most of the European postcommunist countries? Using data from three former communist states, this study investigates the role of trust in close social networks. The results show that so-called ‘particular social trust’ may work as a substitute for trust in institutions. Particular social trust may produce legitimacy for policy measures, in this case, surveillance.

Democracy builds on ideas of freedom in personal development and the right to privacy. It may therefore seem paradoxical that democratic states all over the world invest vast resources in monitoring their citizens. Why citizens allow this is thus a pertinent question. Frequently, the answer is sought in trust. Although surveillance and trust may seem to be in opposition, ‘Any surveillance system depends on a certain level of trust to be legitimate’ (Svenonius & Björklund Citation2018, p. 126).Footnote1 Reasonably, state surveillance in democracies should rest on a certain degree of popular trust in surveilling institutions, which also seems to be the case: a number of opinion studies confirm that positive attitudes to surveillance are associated with trust in institutions and/or trust in governments (Nakhaie & de Lint Citation2013; Pavone et al. Citation2015; Friedewald et al. Citation2016; Svenonius & Björklund Citation2018). Trust seems to give institutions the legitimacy to monitor. Social trust towards other people, on the other hand, is less important for attitudes to surveillance, according to existing research (Friedewald et al. Citation2016; Svenonius & Björklund Citation2018). However, as Friedewald et al. (Citation2015) argue, social trust is important as a predictor for institutional trust (IT) and, thus, indirectly affects acceptance of surveillance. But in which ways is surveillance legitimised in democratic countries where these kinds of trust are low? Assuming that there is always a need for legitimisation of power in democratic states, there must be some other source of that legitimacy next to those that have been studied previously. May other types of trust be relevant to surveillance attitudes?

A feature of surveillance studies is the focus on IT and generalised social trust (GST)—the abstract form of interpersonal trust probed by the survey question, ‘Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?’ Although particular social trust (PST)—trust in closely related others such as family and neighbours (Yamagishi & Yamagishi Citation1994, p. 145)—engages a rising number of trust researchers, it has not yet entered studies on legitimacy and surveillance. While focusing on low-trust postcommunist states, Ford (Citation2017) calls for more attention to PST. Her argument is that, in these low-trust societies, PST may be an alternative way to build politically significant trust relations. To include PST would potentially move studies on social trust more in accordance with the variety of ways that people enact trust towards others and will allow more accurate predictions of certain social phenomena. Following Newton and Zmerli (Citation2011), we assume that this relation-based kind of social trust is constitutive of other trust types. PST is the root of more abstract forms of trust and, therefore, it may predict attitudes to surveillance in similar ways to GST and IT. The question is thus, ‘Does PST play a legitimising role in relation to surveillance in countries where IT and GST are low?’ Similarly to Ford (Citation2017), our main interest lies in low-trust societies (low on GST and IT). We hypothesise that PST may work as a substitute for more abstract forms of trust in these societies.

This study involves three postcommunist East European states: Estonia, Poland and Serbia. The levels of GST and IT are generally lower in Eastern Europe than in Western European states (Watson & Wright Citation2013), although in one of our cases, Estonia, trust levels come closer to classic high-trust cases such as the Scandinavian countries (Olivera Citation2015; van der Meer & Hakhverdian Citation2017). Thus, our empirical data have been taken from one country with relatively high trust levels and two countries where trust levels are low, with Serbia scoring even lower than Poland. The data spring from a survey administered by the project ‘Like Fish in Water’ (LFiW). It provides a unique opportunity to investigate not only GST and IT, but also the levels of PST, which have not been included to date in surveys on trust and surveillance.

The results of the study indicate that PST may play an independent role in legitimising surveillance, particularly in countries where aggregate national trust levels are low. In countries where national levels of trust are high, PST to a higher extent integrates with GST and IT in positive attitudes to surveillance. We will first describe the state of trust research and focus on issues of surveillance. After that, we describe postcommunism as the empirical context for this study. In the subsequent section, we outline three hypotheses that we then test on the LFiW survey data. Finally, we discuss the results in terms of contextual factors affecting the relationship between trust, legitimacy and surveillance.

Trust and surveillance

Arguably, trust is highly relevant in the context of surveillance, but the relationship is more complex than at first sight. On the one hand, trust is about relating positively to society with benign expectations, while surveillance is motivated by the lack of such confidence. Surveillance is normally a highly intrusive activity affecting citizens’ privacy, among other things, and may be harmful to trust. On the other hand, trust is vital to state surveillance in democratic states. If people do not trust the government, they will be reluctant to give the state a mandate to monitor them. To trust, in this line of thinking, is to grant legitimacy. Surveillance, particularly when authorised by the government, is one of the most legitimacy-consuming activities of all (Denemark Citation2012; Nakhaie & de Lint Citation2013).

Due to the complexity of this issue, academic research has increasingly focused on the relationship between control and trust (Knights et al. Citation2001; Rus & Iglič Citation2005; Kääriäinen & Sirén Citation2011), as well as the relationship between attitudes to surveillance and trust—both trust in institutions and GST. While some case studies focus on trust in particular institutions, such as the police (Sorell Citation2011; Ali Citation2016; Duck Citation2017) or security services (Craven et al. Citation2015), others address trust and surveillance in schools (Perry-Hazan & Birnhack Citation2016) or healthcare systems (Szrubka Citation2013). Characteristically, these qualitative studies demonstrate that surveillance is a factor determining variations in levels of trust, while survey research tends to view trust as the predictor of attitudes. Also, studies based on social surveys usually address institutional trust in a more general sense, that is, combining trust in a number of institutions (Friedewald et al. Citation2015, Citation2016; Svenonius & Björklund Citation2018), or using institutional trust in combination with other factors (Patil et al. Citation2014).Footnote2 However, some comparative studies focus on trust in government and surveillance (Denemark Citation2012; Nakhaie & de Lint Citation2013).

Previous research has shown that IT affects consent to surveillance positively (Patil et al. Citation2014; Friedewald et al. Citation2015, Citation2016; Pavone et al. Citation2015; Svenonius & Björklund Citation2018). The strength of the relationship differs depending on how the question is phrased and which aspects of surveillance respondents are asked about. Svenonius and Björklund (Citation2018), for example, find that IT is more important when it comes to acceptance of secret surveillance by intelligence agencies than it is for more general feelings about surveillance. Social trust covaries with IT in attitudes to surveillance, but when modelled together, it seems to be less important.

Previous research on surveillance solely measures generalised social trust, which is also normally the prime interest of survey studies engaged in social trust issues. During recent years we have witnessed an extensive literature on the effects of social trust on political opinions, social behaviour and political performance.Footnote3 However, GST is a considerably scare resource in many countries. High levels of GST are found in few countries and are limited to certain regions characterised by, for example, healthy democracy, low levels of corruption and economic wealth (Delhey & Newton Citation2005, p. 99).Footnote4 Therefore, there is a growing interest in considering other types of social trust, which may have a broader relevance and possibly compensate for shortcomings regarding the types of trust usually measured.

Particular social trust

A rising number of scholars recognise different forms of social trust relating to different ‘layers’ in society, among them PST,Footnote5 defined as trust in closely related others. To a large extent this literature engages in the internal relationship between PST, GST and IT (Freitag & Traunmüller Citation2009; Newton & Zmerli Citation2011; Freitag & Bauer Citation2013; Cao et al. Citation2015; Welzel & Delhey Citation2015).Footnote6 Scholars also bring PST to the fore in a critique of the extensive use of GST as the only indicator of social trust, a practice that tends to miss aspects of the association between political activities and trust (Crepaz et al. Citation2017). We find this argument in postcommunist studies, which claim that Russian society, for example, features strong social networks (PST) and should therefore not be considered a society low on trust simply because it has low GST and IT scores (Gibson Citation2001; Khodyakov Citation2007). In focusing on the significance of PST in relation to surveillance, and also the interrelationship between different kinds of trust, this article builds on this literature. The topic is particularly pertinent because the history of excessive control was presumably a major factor behind the decay of GST and IT in many postcommunist societies.

Notwithstanding this, scholars do not completely agree on the essence of PST. Some studies find that it works as an alternative to GST, arguing that those who have high levels of trust in close relations are less prone to trust strangers (Wollebaek et al. Citation2012, p. 336). PST is to be considered as a compensation for, and incompatible with, low GST (Rothstein & Eek Citation2009; Alesina & Guiliano Citation2011). States that are dominated by clientelism, nepotism and corruption are extreme examples here (Pena López & Sánchez Santos Citation2014). At the same time, PST is arguably a qualification for GST (Möllering Citation2005; Ford Citation2017). Trust in closely related others is a basic condition in all kinds of societies and an almost essential ingredient in human life. PST and GST should be approached as different degrees of closeness (Frederiksen Citation2012). Tight networks form the bedrock of GST, which appears as a more ‘qualified’ form of trust, occurring at a later stage in socialisation. Still, it is only under certain conditions that PST spills over to GST (Freitag & Traunmüller Citation2009); thus, a generalisation of trust does not always happen. Newton and Zmerli (Citation2011) find that PST is a necessary but not sufficient condition for more general forms of trust.Footnote7 These findings are supported by our data. Very few respondents (three respondents in the total data sample, including all three countries) reported high levels of GST and low levels of PST, while high levels of PST are more evenly spread among high and low GST-trusters.Footnote8

While GST is based on the abstract idea of trust in ‘all’ others (Freitag & Traunmüller Citation2009)—a mental model of what to expect from people you do not know (Rothstein & Eek Citation2009, p. 83)—PST is defined by relationships, such as family, friends and neighbours, or membership of, for example, faith-based communities. Several scholars have pointed to the political relevance of PST (Putnam Citation1993; Gibson Citation2001; Ford Citation2017), and it seems reasonable to expect that it also affects attitudes to such a salient and legitimacy-consuming issue as surveillance. Due to its foundational nature, it is likely that it affects attitudes to surveillance in similar ways as GST and IT. Therefore, we qualify the discussion on trust and attitudes to surveillance by adding PST, to the two trust types—IT and GST—that previously formed the focus of surveillance studies.

In countries with low levels of GST we still find PST. Generally, there is less likelihood of finding different levels of PST than GST and IT. A special focus in this study is the situation where particular forms of trust exist despite the lack of GST and low levels of IT. We expect that in low-trust societies PST becomes relatively more important than the other trust types; namely, it works as a substitute.

Following the current academic consensus we define high-trust societies as societies characterised by high levels of GST as well as high levels of IT. We know from previous studies that GST tends to co-vary with trust in institutions. Although the results are by no means perfect (Newton & Zmerli Citation2011), several recent studies report that expressed high levels of GST are associated with high levels of IT (Rothstein & Stolle Citation2008; Zmerli & Newton Citation2008; Jamal & Nooruddin Citation2010; Sønderskov & Dinesen Citation2016; Delmut & Tallberg Citation2017).

We assume that the aggregate levels of GST and IT condition the relationship between trust and attitude to surveillance at the individual level. In doing so, our study draws on the so-called ‘rainmaker effect’ model (Newton & Zmerli Citation2011), which claims that whether aggregate trust in a society is high or low is relevant to the relationship between, in this case, trust and surveillance at the individual level. When the above-mentioned trust qualities are high in a given society, these types of trust become a more relevant factor behind people’s opinions. They attain a norm-like moral quality (Uslaner Citation2013) that, at the individual level, feeds into support for community-building and for such legitimacy-demanding measures as surveillance. Thus, the political and societal significance of PST is, according to the rainmaker assumption, to a large extent dependent on low national aggregate levels of GST and IT. In low-trust societies, where there is a lack of GST and IT, we assume that PST compensates for this deficit and plays a relatively more important role in popular attitudes, among them the attitude to surveillance. We find the significant trust-building context in immediate connection with people’s relational experiences.

The postcommunist setting

This study concerns trust and surveillance in three former communist societies. We are interested in the difference between states with a communist legacy. The main concern is societies with low levels of GST and IT (Poland and Serbia), that is, low-trust countries, and the role that PST may play in attitudes to surveillance in these societies. Thus, we are not primarily interested in postcommunism in any explanatory sense. Postcommunism works as a setting that enriches the discussion of the results of this study.

There are still only a few studies on surveillance in postcommunist states (Székely Citation1991; Budak et al. Citation2015; Svenonius & Björklund Citation2018).Footnote9 Given the recent legacy of systemic control in these countries, this is a bit puzzling (Svenonius et al. Citation2014). One feature of communist rule was the large-scale surveillance practised by the regimes and directed towards the citizens. An informant system permeating society fostered distrust between people (Horne Citation2014), although communism worked differently in different states within the Eastern bloc (Pop-Eleches & Tucker Citation2012). Studies reveal that personal experiences of surveillance during communism are relevant for attitudes to surveillance after the fall of communism (Svenonius & Björklund Citationnd).

Extensive surveillance was a feature of communist rule and also provided particular cultural and institutional conditions for trust between people and towards institutions (Ford Citation2017). Howard (Citation2002) argues that strong PST worked as an alternative security context in oppressive states where other types of trust relations were undermined. In addition, when economic mismanagement meant that states failed to meet people’s basic needs, they turned to traditional informal networks instead (Cook et al. Citation2004). Did this kind of social organisation outlast communism? This question has engaged researchers in the field. The fall of communism sparked a genre of literature dealing with the relationship between these local forms of trust and democracy, political participation and generalised forms of trust (Mishler & Rose Citation1998; Offe Citation1999; Rose Citation2001; Letki & Evans Citation2005; Sapsford & Abbott Citation2006; Khodyakov Citation2007; Ledeneva Citation2009). Åberg in his study on Western Ukraine notes that social capital in some respects is ‘a more efficient device for practical problem solving compared with the relative failure of formal institutions’ (Åberg Citation2000, p. 313). Gibson argues that, while lacking GST, ‘perhaps in the response to the totalitarianism of the past, Russians have developed extensive social networks with high levels of political capacity’ (Gibson Citation2001, p. 51).Footnote10 In her quantitative study on the postcommunist region, Ford (Citation2017) finds similarities between those who trust particularly and those who trust generally when it comes to support for liberal democracy. Thus, she demonstrates that PST has a political significance in these societies which has seldom been recognised. While relating attitudes towards surveillance to trust, our study draws on these findings.

Hypotheses

The fact that IT is positively associated with acceptance of surveillance, as shown in several studies, is quite easy to understand. In order to accept state surveillance, citizens need to trust the state. However, with regard to social trust, things are a bit more complicated. Intuitively, we expect that people who trust each other will be less positively disposed towards surveillance, since they will not see any need for it. Non-trusting individuals, in contrast, should be more positive. This reasoning entails a rationalistic view of trust that says trust is based on experiences from the past, the individual interests and possible gains involved in each specific situation, and considerations concerning risks involved in trust (Gambetta Citation2000; Hardin Citation2002). From this perspective, surveillance may compensate for a lack of trust. In the absence of trust, it is rational to put faith in surveillance.

However, when considering previous studies based on social surveys, we see that things are not that simple. Not only IT but also GST correlate positively with acceptance of surveillance, although the association is weaker in the latter case. This may seem confusing but makes sense, given an alternative understanding of trust, one that does not see trust primarily as an outcome of rational deliberation. Trust may well be the result of individual and social learning (Glanville & Paxton Citation2007), meaning that trust is not instrumental and decided by situational factors but by factors beyond the situation at hand, for example, early childhood socialisation (Uslaner Citation2000), shared moral values (Uslaner Citation2002, Citation2013), social capital (Putnam Citation1993) or human everyday practices and habitual routines that create a notion of control (Giddens Citation1991). These are socio-cultural understandings of trust. Following from this kind of theory, first, different types of trust—social and institutional—constitute a ladder, starting with trust in small social contexts and evolving into more abstract forms of trust (Glanville & Paxton Citation2007). Thus, it seems most likely that these should determine attitudes in similar ways. Second, drawing on Uslaner (Citation2013), GST addresses not individual strategic interests but rather sentiments of belonging to a society or a moral community, which should entail an interest in protecting those societal values. From this point of view, it seems reasonable that both IT and social trust may result in positive attitudes to surveillance, if control measures are considered to protect core values in a society. Those who do not trust others do not have this sense of belonging and thus should be more prone to reject surveillance. The findings from previous social survey research on GST and surveillance make sense from a socio-cultural perspective, although this is seldom spelled out in the literature. In this study, we apply a socio-cultural perspective on trust.

In building on previous studies on surveillance attitudes, our initial focus is on how GST and IT affect attitudes to surveillance in our three countries. While attending to the difference between high- and low-trust countries we examine whether aggregate levels of GST and IT (trusting or not trusting societies) condition the relation between these kinds of trust and attitude to surveillance at the individual level. Thus, the overall level of trust in society is assumed to reveal itself in individual attitudes. We assume that trust legitimises surveillance but to a different degree, depending on the overall levels of trust.

Our first hypothesis (H1) is as follows: Attitudes to surveillance depend on IT and GST. Trusting individuals accept surveillance but in low-trust societies, the effects are weaker than in high-trust societies. In line with previous research, we expect a positive relationship between IT and, to a lesser extent, GST, and support for surveillance. This should be the case in all our three countries, but the association should be strongest in Estonia (the high-trust society in our sample). In relatively low-trust societies (low GST and IT on an aggregate level), such as Poland and Serbia, we expect the impact of GST and IT on attitude to surveillance to be weaker.

If H1 is confirmed, this initially supports the rainmaker assumption on the significance of a trusting society. Where these kinds of trust are the societal norm, GST and IT are more crucial to legitimacy-consuming measures such as surveillance. Where trust is normatively weaker, we find less of this effect. Since all the countries included in the study are postcommunist, such a result also suggests that a common postcommunist heritage is less important here. Trust levels are more important or, possibly, the capacity to overcome the communist past by creating or restoring trust in society.

We further assume that PST is a predictor of attitudes to surveillance. The literature on postcommunist states and local trust relations gives us particularly strong reasons to expect that this is the case in the three societies that we analyse. From a socio-cultural perspective, local forms of trust are the very heart of the trust construct. Trust in small constellations is where it all starts. Under favourable conditions PST spreads in wider circles and trust eventually includes people in general (Newton & Zmerli Citation2011). To trust is to relate to society in terms of a collection of internalised values. We expect, on the one hand, that trust follows a pattern from PST to more abstract trust forms—GST and IT—meaning that PST may be present even if GST and IT are not yet attained. On the other hand, trust is unidimensional in the sense that different types of trust will affect attitudes in the same directions. In this study, we see PST and GST as indicators of inclusiveness and producers of legitimacy. Both PST and GST are indicators of belonging to a society, which we expect to be positively associated with attitudes relating to law and order, in our case, surveillance.

Thus, the second hypothesis (H2) is: People who trust peers in their close social networks have more positive attitudes to surveillance than those who do not. However, we assume a difference between our three countries when it comes to the role of PST. In our low-trust societies, Poland and Serbia, we expect to find that PST functions as a substitute for the more generalised forms of trust, in attitudes to surveillance. Trust legitimises surveillance; but in these countries, it is PST that plays the most important role and it does so despite low levels of other forms of trust. PST should have a stronger effect on attitudes than GST and IT in Poland and Serbia than it has in Estonia.

Thus, in Poland and Serbia, we expect to find an independent effect from PST on acceptance of surveillance. In Estonia PST is expected to integrate with the other types of trust into an attitude of less concern about surveillance. In line with Friedewald et al. (Citation2016), we expect IT to consume most of the relationship between GST and surveillance but also, particularly in Estonia, the effect of PST.

The third hypothesis (H3) is as follows: In low-trust societies PST works as a substitute for GST and IT and is associated with positive attitudes to surveillance, while in high-trust societies PST does not explain attitudes to surveillance. In sum, we expect that PST is positively related to acceptance of surveillance in all three countries. However, in a high-trust society, where trust is the overall normative standard, it is the integrated effect of different kinds of trust which affects attitudes. If aggregated generalised social and institutional trust is low (low-trust societies), we expect to find a weaker relationship between these kinds of trust and attitudes to surveillance. But this does not mean that people are less positive about surveillance. In the absence of GST and IT, PST works as an independent source of legitimisation that promotes a positive attitude to surveillance.

Methods and operationalisation

This study is carried out using the LFiW survey data (Svenonius et al. Citation2015). The dataset is based on a survey commissioned by IPSOS in 2014 and 2015 by the Like Fish in Water: Surveillance in Post-Communist Societies project, which sought to investigate issues of trust and surveillance in postcommunist societies. Three countries were included in the survey: Estonia, Poland and Serbia. Sample frame populations were the respective national populations, aged 18–80. A random probability sample in each country resulted in a dataset consisting of 995 completed interviews in Estonia, 1,041 in Serbia and 998 in Poland. The survey comprises not only conventional trust measures, namely, GST and IT, but also a range of questions on PST. Within the population of postcommunist societies, the selection of cases for the survey was made based on levels of IT in the European Social Survey, as reported by Jackson et al. (Citation2011). Estonian citizens tend to report high IT levels, whereas Serbian citizens tend to report the opposite. IT in Poland is somewhere in between. The LFiW dataset thus comprises data tailored to test the hypotheses developed above.

Response ratios vary: from high rates in Estonia (72.5%) and Serbia (61.7%) to significantly lower ones in Poland (35.4%). Unit non-response, foremost in Poland, is mainly due to no contacts in apartment buildings or refusals due to a lack of interest. Post-stratification weights compensate for any demographic bias caused by missing data in the analyses below. Differences between cases aside, in each country, the response ratio is slightly higher than comparable surveys.Footnote11

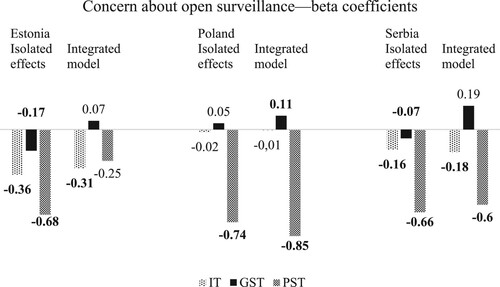

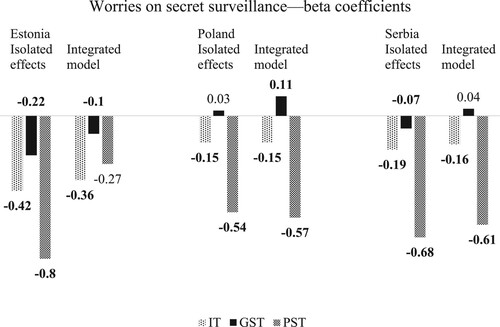

The analysis makes use of a standard statistical toolbox: correlation analysis and linear regression. We emphasise interpretability in the choice of methods and presentation of the results. First, we explore the relationships between the variables, and then focus on the strength of the effects of interest for the hypotheses discussed above. In the following section, we present two sets of linear regression outputs for the two dependent variables that we describe below: concern about open surveillance and worries about secret surveillance.Footnote12 The results are displayed in the form of bar charts, meaning that we gain in accessibility at the cost of complete information. We recommend the interested reader to consult the Appendix for full regression models. A simple model including only the demographic variables functions as the baseline for subsequent regression models introducing the different types of trust one by one. In , which presents regression beta coefficients, each of these are labelled ‘isolated effects’ from IT, GST and PST respectively. Each discrete effect of the different types of trust in the combined model is represented as the ‘integrated model’ value in the bar chart.

Indicators: dependent and independent variables

Social surveys on attitudes to surveillance mainly focus on ‘open’ surveillance, such as CCTV, but there are also studies on attitudes to anti-terrorism measures, particularly in the wake of 9/11 (Denemark Citation2012; Nakhaie & de Lint Citation2013; Steinfeld Citation2017). These works concern surveillance undertaken by intelligence agencies that by nature is of a more covert kind. The distinction between these two types of surveillance—open and secret—is important since they may generate different sentiments among the public and engage trust in different ways. While open surveillance is something that people, at least to some extent, are aware of, secret surveillance is characterised by lack of transparency (Svenonius & Björklund Citation2018). Thus, to trust a surveilling institution or a government in matters of secret surveillance represents a deep level of institutional trust, since measures cannot be checked in the same way as with open surveillance. For the sake of validity, we include both open and secret surveillance in the present study.

These different dimensions of surveillance refer to different political and social aspects in postcommunist societies. Whereas secret surveillance is typically highly controversial, open surveillance such as CCTV is often a desired modern amenity.Footnote13 To explore attitudes to secret surveillance, we make use of an item probing respondents’ worries about surveillance by intelligence agencies. The second variable, open surveillance, is operationalised as privacy concerns about video surveillance. Whilst privacy concerns may not directly be equated with attitudes to surveillance, the survey item used in the analysis below explicitly probes for privacy concerns regarding video surveillance of public places by local police. As such, it juxtaposes privacy and surveillance as opposing values, and can therefore be used to measure attitudes to what we call ‘open’ surveillance. Both survey items measure responses on an 11-degree numeric scale (0–10),Footnote14 ranging from no worries/concern to very worried/concerned. In sum, this study deploys two different items to measure attitudes to surveillance: worries about secret surveillance and concerns regarding video surveillance in public places. This enables us to cover a broader spectrum of surveillance activities, which strengthens construct validity in the analysis below.

shows statistics for each country on our two surveillance indicators. We see that surveillance is slightly more controversial in Poland than in the other two countries. This is true for both indicators. However, we are not primarily interested in the difference between absolute figures on concern.

TABLE 1 Summary Statistics of Dependent Variables

Looking at the independent indicators, our interest lies in different varieties of trust. GST is conventionally operationalised as whether people in general can be trusted or not. The LFiW survey used the wording developed by the European Social Survey for this item, which is measured on an 11-degree scale (0–10). We measure PST through a composite variable consisting of three items: trust in one’s own family, trust in one’s neighbours and trust in acquaintances. An individual mean was taken from these three items resulting in a scale ranging from 0 to 5. IT follows other studies in the field. IT can be measured in a variety of ways but usually a composite variable is constructed consisting of trust in a selection of significant public institutions, including the government. In this study IT is defined by trust in government, the police, intelligence agencies, the tax agency and the courts (legal system). It is measured on a 11-degree scale (0–10). In addition, demographic controls applied in the analysis are age (years), higher education and income.Footnote15 Summary statistics for the independent variables are displayed in .

TABLE 2 Summary Statistics for Independent Variables

The independent variables show different levels of trust between the three countries. Estonia scores highest on GST and IT, followed by Poland and lastly Serbia. PST shows a different picture. The scores are almost equal; negligibly higher for Estonia, while Poland and Serbia show almost identical figures.Footnote16 This is in line with what we expected; the level of PST does not vary between countries to the same extent as GST and IT. Following the reasoning about the socio-cultural foundations of trust above, the IT and GST data displayed in lead us to assume that Estonia is the most cohesive society of the three, followed by Poland and finally Serbia. The Estonian ‘trust culture’—which may or may not correspond to a better system of governance in reality—could in turn suggest that Estonians accept surveillance to a higher degree (as per hypothesis 1). If this is so, our theory leads us to expect that attitudes to surveillance in Poland and Serbia rest on other causes, such as PST.

The next section presents the results of statistical analysis. We first explore the relationships between indicators in terms of their internal correlations, and then proceed with the regression results.

Results

Below (see ) we use pairwise correlation to define the relationship between the trust variables and concerns about video surveillance. As should be noted, the dependent variables are different constructs, meaning that they do not correlate more than circa 30%, which we deem to be an acceptable degree due to their common thematic.

TABLE 3 Pairwise Correlations for Independent and Dependent Variables

Regarding both secret surveillance and open surveillance, IT matters most in Estonia, to a lesser degree in Serbia and, in Poland, not much with regard to worries about secret surveillance and not at all when it comes to open surveillance.

Looking at the first social trust independent variable, GST, we see a pattern whereby Estonia differs from the other two. There is a significant association between GST and worries about secret surveillance. The same is true for GST and concerns about open surveillance in Estonia. The correlations are close to zero in the other two countries. Note that the association in Poland on open surveillance is positive, not negative. More trust means more concern. For PST the figures are more mixed, although it plays into both attitudes to secret and open surveillance. It scores highest for Estonia and Serbia on secret surveillance and highest for Poland on open surveillance. In contrast to the other two trust measures, PST seems to be relevant to both open and secret surveillance in all three countries.

In the bar chart we present linear regression coefficients for attitudes to open surveillance.Footnote17

shows the effects of the three different types of trust on attitudes to open surveillance sorted by country. Firstly, for each country we see the isolated effects from IT, GST and PST (the first three bars). Secondly, the figure shows the effect of each trust variable when considered all together, that is, the integrated effects corresponding to the full model in the linear regression analysis (bar four to six for each country). Please note that negative signs mean that more trust is associated with less concern. Bold figures indicate a non-significant figure.

Before taking other trust forms into consideration, IT has the largest effect in Estonia, followed by Serbia, and then Poland with no effect at all. GST has a small impact in Estonia and a very small one in Serbia, but the significant associations disappear in the integrated model, meaning that they integrate into the other trust forms in attitudes to open surveillance. For Poland there is a small effect from GST in the integrated model, but please note that this is positive. Concerning GST, Poland does not follow the expectation that more trusting individuals accept surveillance; rather, trust seems to increase concern. When looking at Estonia, on the one hand, and Poland and Serbia, on the other, the findings support H1, with some qualifications. H1 assumes that attitudes to surveillance depend on IT and GST, but both seem to be more or less irrelevant in Poland. IT matters most in Estonia for reducing concern about open surveillance, which is in line with expectations, but GST shows no effect when the other trust variables are taken into account.

Initially, PST is negatively related to concern about open surveillance in all three countries, in accordance with the expectation of H2. But the integrated model shows that this effect disappears for Estonia and remains in Poland and Serbia, which, comparing Estonia with the other two, supports H3. PST seems to have the potential to work as a substitute for the other types of trust in the latter countries, while positive attitudes in Estonia can be attributed to IT and the integrated effects from GST and PST. We now move on to see whether this is also true for secret surveillance.

In we find a similar, although not identical, pattern.Footnote18 IT predicts attitudes to secret surveillance in all three countries, more trust is associated with less worry (negative sign). The effect also prevails in the integrated models, but it is stronger in Estonia and weaker in the other two cases. GST has an initial negative effect on worries in Estonia and a very small initial effect in Serbia. It disappears in the integrated model for Serbia and only a minor association remains for Estonia. In the Polish case, GST does not indicate that the respondent believes that secret surveillance is legitimate. If anything, people with generalised social trust are more worried rather than less.Footnote19 Thus, H1 gains support, with some qualification.

FIGURE 2. Linear Regression Coefficients: Worries about Secret Surveillance

Note: Bold figures imply statistical significance on the 1%–5% level. Only in the case of GST in Serbia (isolated effect) is the significance level at 10%.

There is an initial effect from PST in all three countries, but it disappears for Estonia in the integrated model while in Poland and Serbia the effects remain almost the same. In the Estonian case, PST and also, to a large extent, GST integrate with IT into less concern about secret surveillance, while in Poland and Serbia PST has an independent effect. Thus, H2 is supported: people who have a high level of trust in their peers in close social networks have more positive attitudes to secret surveillance than those who trust their peers to a lesser extent. However, in the Estonian case, this kind of trust does not explain attitudes, since the effect is eliminated in the integrated model, while in Poland and Serbia the independent effect remains and is stronger than the effect from IT, thus supporting H3.Footnote20

Concerning both open and secret surveillance, we find that PST works according to two different logics. H3 assumes that in low-trust societies (low on GST and IT), PST serves as a substitute for GST and IT and is associated with more acceptance of surveillance, while in high-trust societies there is less of an independent effect from PST. As shown above, in the Estonian case, PST is consumed by the more abstract forms of trust, IT and GST. Trust as a source of legitimacy, is, to a higher extent than in the other two cases, unidimensional. However, legitimacy may also be achieved in the absence of abstract trust, as the Polish and Serbian cases indicate.

However, it should be noted that the strength of this analysis is the uniformity of the effects, not necessarily the exact size of the coefficients. The models presented above do not explain a high portion of the data, with R2 values in the 5%–10% range for the Estonian data and 1%–5% for Poland and Serbia.Footnote21 This is expected, due to the ‘messy’ type of survey data that we analyse here where high R2 values are not attainable. Here, the effects and the fact that they are consistent with our expectations matter most. This indicates how trust may function in different kinds of settings. Trust in general has only a small significance for surveillance attitudes in Poland and Serbia. In fact, it is only the effect from PST on open surveillance in Poland that explains more than 4% of the variation in attitudes, Still, most of this effect remains when the other types of trust are also taken into consideration.

From and we learn that there is a slight difference between attitudes to open surveillance and attitudes to secret surveillance in Poland. While PST is not a significant independent explanatory factor for any of these in Estonia (integrated models) and affects open and secret surveillance in a similar way in Serbia, in Poland the association between PST and concern about open surveillance seems a bit stronger than between PST and worries about secret surveillance. It is hard to tell why this is the case, but previous research emphasises the complicated lustration processes and public sector corruption scandals during the decade preceding this survey as factors that may have weakened trust in political institutions as well as between people (Horne Citation2014; Svenonius et al. Citation2014). Poland stands out in the data: as we see in the summary statistics in , those worried about secret surveillance in Poland get the highest mean scores amongst attitudes to surveillance in all three countries. Polish respondents’ worries about secret surveillance, to a higher extent than open surveillance, may have to do with other things than trust, possibly the way that people relate to historical experiences.

Particular social trust as a predictor of attitudes to surveillance

We introduced our topic by asking why citizens in democratic states allow state surveillance. Trust matters, but obviously, trust does not provide a complete answer. Our models indicate that a considerable part of the variance is explained by aspects other than trust. Trust is one piece among many in a much larger puzzle. But by extending trust to include PST, we altered and expanded the scenery in relation to previous studies. Most importantly, the introduction of PST shows that trust is more relevant for attitudes than usually expected in countries where the commonly measured trust types, GST and IT, are low.

Our study provides supporting evidence for the assumption that people with positive experiences in their network—high PST—tend to accept surveillance to a higher degree. This is the case in all three countries. One might consider these findings a bit puzzling. Why are people who distrust their fellow citizens not more in favour of surveillance than others? In a way this looks like the most likely scenario. As shown by our results, the answer is that trust works according to a different rationale and can be considered as a process (Khodyakov Citation2007; Ford Citation2017) involving, institutional, generalised and particular social trust. Trust, in this view, is something we learn, and PST functions as the bedrock of all kinds of trust. This study indicates that rather than being in opposition, PST corresponds with GST and IT. Trust is caring about what goes on in society, and this also applies to PST. Local network trust defines an individual’s relationship to society in a similar way to the other kinds of trust, although it concerns a narrower context. Well-established local networks increase the propensity to care also about general political issues. In our understanding, trust is based on a feeling of belonging, which implies that there is something to lose and thus, something that needs protection. Surveillance might be considered as a measure to meet external threats. Thus, trust, including trust in close relationships, is in no way in opposition to assenting to surveillance. As shown, PST might be as effective as other types of trust in underpinning legitimacy.

The postcommunist context is particularly relevant for studying trust as a process. Postcommunist societies, in a sense, all have a common background in being formerly under regimes that destroyed benign trust relations. They also, albeit to different degrees, have experience of systemic surveillance. While all the countries in this study have a legacy of communism, the effects of trust on attitudes to surveillance differ. We find that, despite a common heritage, trust means different things. The significance of PST varies due to varying overall levels of trust. Our results are in line with Gibson’s suggestion that private social networks may substitute for formal organisations and carry ‘considerable political content’ in a postcommunist context of low institutional trust (Gibson Citation2001, p. 60). In our low-trust countries PST seems to ‘create’ legitimacy independently from institutional and general social trust and, thus, function as a substitute for these kinds of trust. In high-trust societies, in this case, Estonia, the picture is different. PST still underpins a positive attitude to surveillance, but it has less of an independent effect. Although PST still matters, the legitimacy-creating function of trust has been transferred to more abstract forms of trust.

In line with previous research, we find that IT and, to a lesser extent, GST are associated with acceptance of surveillance. However, the present study tells us that the effect differs widely between countries. In order to give a fair account of the role of IT in building legitimacy for surveillance, trust needs to be contextualised to a higher extent than it has previously been. Being a high-trust country seems to have a rainmaker effect, which increases the likelihood that attitudes towards surveillance depends on, in particular, the legitimacy of institutions. The task of defining more precisely how the rainmaker mechanism works in practice should be the focus of further studies. Arguably, trust is not something that works in isolation and the more widespread IT is, the more likely that it is associated with stable systemic support, a condition for legitimate institutions that is closely associated with societal norms. If IT is rarer in a given society, it is more likely that it derives from temporary experiences of institutional conduct, which do not affect institutional legitimacy in the long run.

Our results could be construed as Estonia being the country most rapidly leaving behind its postcommunist legacy and entering a stage where more abstract types of trust predict attitudes. However, even though trust should be considered as a process, with PST as the necessary initial condition, it would be naïve to assume that any determinism is involved in the way trust evolves from particular to more generalised forms. Rather, they most likely interact (Ford Citation2017, p. 129), and what this looks like warrants more in-depth study than is provided here.

This study draws on data that were collected in 2014–2015. It is unique in terms of the trust and surveillance items included in the survey. In addition, our research indicates that there are gaps in previous research and that additional studies on the relationship between different types of trust, in general, and how they relate to specific policy areas, in particular, are very much needed. Our analysis provides the research community with input for future research.

In order to make recommendations for policymakers, more evidence needs to be collected and analysed. Surveillance is a policy that should require legitimacy, and this study shows that legitimacy may originate in different kinds of trust constellations, among them PST. Our findings suggest that PST may also be important for social support within other policy areas. Thus, from this study we learn the significance of not neglecting the societal relevance of trust in close relations. As general social trust is declining in many countries, this advice might become even more relevant.

The research for the article was conducted at Södertörn University. This research was funded by the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (Östersjöstiftelsen), grant number A051.12.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Fredrika Björklund

Fredrika Björklund, Professor in Political Science, Södertörn University, 141 89 Huddinge, Sweden. Email: [email protected]

Ola Svenonius

Ola Svenonius, Senior Researcher, Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI), 164 90 Stockholm, Sweden. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 See also Ellis et al. (Citation2013).

2 See Watson et al. (Citation2017) who call for quantitative studies on surveillance attitudes with a more nuanced approach to institutional trust.

3 See for example, Rothstein and Stolle (Citation2008), Bjørnskov and Tinggaard Svendsen (Citation2013), Graeff and Tinggaard Svendsen (Citation2013), and Sønderskov and Dinesen (Citation2016).

4 In addition, GST is criticised from a methodological perspective on the grounds that it is extremely hard to measure trust in people in general; people always have some specific group in mind in terms of trust. See Björklund (Citation2019) for an overview.

5 Sometimes referred to as ‘in-group trust’, in contrast to ‘out-group trust’ (Welzel & Delhey Citation2015; Cao et al. Citation2015), or ‘thick trust’ in contrast to ‘thin trust’ (Newton Citation1997; Khodyakov Citation2007).

6 Some studies add a fourth form of trust, ‘identity trust’ (Freitag & Bauer Citation2013) or ‘community trust’ (Wollebaek et al. Citation2012).

7 The assertion that PST is a casual condition for GST has been contested; see, for example, Welzel and Delhey (Citation2015). They argue that GST may evolve without PST and discriminate between derivative and transcendent ‘out-group trust’ (GST). The latter may emerge regardless of ‘in-group trust’ (PST). Thus, we should not expect a seamless transition from PST to GST.

8 See Appendix 3.

9 The assumption behind the epithet ‘postcommunism’ is that experiences of communist rule continued to affect people’s attitudes or behaviour beyond the fall of communism (Pop-Eleches & Tucker Citation2011; Svenonius et al. Citation2014; Wittenberg Citation2015).

10 Some studies question if postcommunist societies are unique in these matters. In a broad study, including a large number of states in both Eastern and Western Europe, Pop-Eleches and Tucker found no indications that an alternative informal network culture substituted for participation in formalised social organisations in postcommunist states (Pop-Eleches & Tucker Citation2013, p. 61). Delhey and Newton (Citation2003) note that personal social networks affect generalised social trust in both postcommunist and Western states.

11 Please see Appendices 1 and 2 on missing data and sampling methods.

12 ‘Concerns’ and ‘worries’ are used synonymously in this analysis; the differences in semantics are the result of different phrasings in the survey questionnaire.

13 On this issue, see Waszkiewicz (Citation2011), Sojka (Citation2013), and Björklund and Svenonius (Citation2013).

14 Survey items used in the analysis are listed in Appendix 4.

15 The income variable was standardised in order to accommodate differences in currency and reported income levels.

16 The scale is 1–5 for PST and 0–10 for the other independent variables.

17 For full regression models, including the ANOVA test, please consult Appendix 5.

18 For full regression models, including the ANOVA test, please consult Appendix 6.

19 The increased effects in the integrated model in the Polish case relate to the different signs of the values.

20 For the sake of clarity, we omitted the demographic variables in the bar charts since only education in Poland (secret surveillance) and Estonia (open surveillance) have a clear effect. See Appendices 5 and 6.

21 Please note that the R2 values are approximate. Due to the data imputation in the income variable, definite R2 values are not possible. More information and exact figures are available in Appendices 5 and 6.

References

- Åberg, M. (2000) ‘Putnam’s Social Capital Theory Goes East: A Case Study of Western Ukraine and L’viv’, Europe-Asia Studies, 52, 2.

- Alesina, A. & Guiliano, P. (2011) ʻFamily Ties and Political Participation', Journal of the European Economic Association, 9, 5.

- Ali, A. I. (2016) ‘Citizens under Suspicion: Responsive Research with Community under Surveillance', Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 47, 1.

- Björklund, F. (2019) ʻVilken roll spelar risk i tillit. En diskussion om begreppet generaliserad tillit', Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 121, 1.

- Björklund, F. & Svenonius, O. (eds) (2013) Video Surveillance and Social Control in a Comparative Perspective (Abingdon & New York, NY, Routledge).

- Bjørnskov, C. & Tinggaard Svendsen, G. (2013) ʻDoes Social Trust Determine the Size of the Welfare State? Evidence Using Historical Identification', Public Choice, 157, 1.

- Budak, J., Rajh, E. & Anić, I.-D. (2015) ʻPrivacy Concern in Western Balkan Countries: Developing a Typology of Citizens', Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, 17, 1.

- Cao, L., Zhao, J., Ren, L. & Zhao, R. (2015) ʻDo In-Group and Out-Group Forms of Trust Matter in Predicting Confidence in the Order Institutions? A Study of Three Culturally Distinct Countries', International Sociology, 30, 6.

- Cook, K., Rice, E. & Gerbasi, A. (2004) ʻThe Emergence of Trust Networks Under Uncertainty: The Case of Transitional Economies—Insights from Social Psychological Research', in Rose-Ackerman, S., Rothstein, B. & Kornai, J. (eds) Creating Trust in Post-Socialist Transition (New York, NY, Macmillan).

- Craven, K., Monahan, T. & Regan, P. (2015) ʻCompromised Trust: DHS Fusion Centers’ Policing of the Occupy Wall Street Movement', Sociological Research Online, 20, 3.

- Crepaz, M. M. L., Jazayeri, K. B. & Polk, J. (2017) ʻWhat’s Trust Got to Do With It? The Effects of In-Group and Out-Group Trust on Conventional and Unconventional Political Participation', Social Science Quarterly, 98, 1.

- Delhey, J. & Newton, K. (2003) ʻWho Trusts?: The Origins of Social Trust in Seven Societies', European Societies, 5, 2.

- Delhey, J. & Newton, K. (2005) ʻPredicting Cross-National Levels of Social Trust: Global Pattern or Nordic Exceptionalism', European Sociological Review, 21, 4.

- Delmut, L. & Tallberg, J. (2017) ʻWhy National and International Legitimacy Are Linked: Effects of Social Trust', paper presented at the 10th Conference on the Political Economy of International Organizations (PEIO), 12–14 January, Bern.

- Denemark, D. (2012) ʻTrust, Efficacy and Opposition to Anti-terrorism Police Power: Australia in Comparative Perspective', Australian Journal of Political Science, 47, 1.

- Duck, W. (2017) ʻThe Complex Dynamics of Trust and Legitimacy: Understanding Interactions between the Police and Poor Black Neighborhood Residents', ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 673, 1.

- Ellis, D., Harper, D. & Tucker, I. (2013) ʻThe Dynamics of Impersonal Trust and Distrust in Surveillance Systems', Sociological Research Online, 18, 3.

- EU FRA (2014) Violence Against Women; An EU-wide Survey—Survey Methodology, Sample and Fieldwork. Technical Report (Vienna, European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights), available at: http://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/violence-against-women-eu-wide-survey-survey-methodology-sample-and-fieldwork, accessed 6 February 2020.

- Ford, N. M. (2017) Measuring Trust in Post-Communist States; Making the Case for Particularized Trust, doctoral thesis (Tampa, FL, University of South Florida, Scholar Commons).

- Frederiksen, M. (2012) ʻDimensions of Trust: An Empirical Revisit to Simmel’s Formal Sociology of Intersubjective Trust', Current Sociology, 60, 6.

- Freitag, M. & Bauer, P.C. (2013) ʻTesting for Measurement Equivalence in Surveys: Dimensions of Social Trust across Cultural Contexts', Public Opinion Quarterly, 77, Special issue.

- Freitag, M. & Traunmüller, R. (2009) ʻSpheres of Trust: An Empirical Analysis of the Foundations of Particularised and Generalised Trust', European Journal of Political Research, 48, 6.

- Friedewald, M., Rung, S., van Lieshout, M., Ooms, M. & Ypma, J. (2015) Report on Statistical Analysis of the PRISM Survey. Deliverable 10.1, PRISMS Project (Karlsruhe, Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI).

- Friedewald, M., van Lieshout, M., Rung, S., Ooms, M. & Ympa, J. (2016) ʻThe Context-Dependence of Citizens’ Attitudes and Preferences Regarding Privacy and Security', in Gutwirth, S., Leenes, R. & De Hert, P. (eds) Data Protection on the Move: Current Developments in ICT and Privacy/Data Protection (Dordrecht, Springer).

- Gambetta, D. (2000) ‘Can We Trust Trust?’, in Gambetta, D. (ed.) Trust: Making and Breaking of Cooperative Relations (Oxford, University of Oxford).

- Gibson, J. L. (2001) ʻSocial Networks, Civil Society, and the Prospects for Consolidating Russia’s Democratic Transition', American Journal of Political Science, 45, 1.

- Giddens, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (Cambridge, Polity Press).

- Glanville, J. L. & Paxton, P. (2007) ‘How Do We Learn to Trust? A Confirmatory Tetrad Analysis of the Sources of Generalized Trust’, Social Psychology Quarterly, 70, 3.

- Graeff, P. & Tinggaard Svendsen, G. (2013) ʻTrust and Corruption: The Influence of Positive and Negative Social Capital on the Economic Development in the European Union', Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology, 47, 5.

- Hardin, R. (2002) Trust and Trustworthiness (New York, NY, Russell Sage Foundation).

- Horne, C. M. (2014) ʻLustration, Transitional Justice, and Social Trust in Post-Communist Countries. Repairing or Wresting the Ties that Bind?', Europe-Asia Studies, 66, 2.

- Howard, M. M. (2002) ʻThe Weakness of Postcommunist Civil Society', Journal of Democracy, 13, 1.

- IPSOS Mori (2011) Life in Transition Survey II: Technical Report (London, IPSOS Mori), available at: https://www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/economics/Technical_Report.pdf, accessed 6 February 2020.

- Jackson, J., Hough, M., Bradford, B., Pooler, T., Hohl, K. & Kuha, J. (2011) ‘Trust in Justice: Topline Results from Round 5 of the European Social Survey’, European Commission, available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/41680/1/Trust%20in%20justice%28lsero%29.pdf, accessed 26 November 2019.

- Jamal, A. & Nooruddin, I. (2010) ʻThe Democratic Utility of Trust: A Cross-National Analysis', The Journal of Politics, 72, 1.

- Johnsson, P. (2012) ʻGated Communities: Poland Holds the European Record in Housing for the Distrustful', Baltic Worlds, 5, 3–4.

- Kääriäinen J. & Sirén, R. (2011) ʻTrust in the Police, Generalized Trust and Reporting Crime', European Journal of Criminology, 8, 1.

- Khodyakov, D. (2007) ʻTrust as a Process: A Three-Dimensional Approach', Sociology, 41, 1.

- Knights, D., Noble, F., Vurdubakis, T. & Willmott, H. (2001) ʻChasing Shadows: Control, Virtuality and the Production of Trust', Organization Studies, 22, 2.

- Ledeneva, A. (2009) ʻFrom Russia with Blat. Can Informal Networks Help Modernize Russia?', Social Research, 76, 1.

- Letki, N. & Evans, G. (2005) ʻEndogenizing Social Trust: Democratization in East-Central Europe', British Journal of Political Science, 35, 3.

- Mishler, W. & Rose, R. (1998) ʻTrust in Untrustworthy Institutions: Culture and Institutional Performance in Post-Communist Societies', Studies in Public Policy, 310.

- Möllering G. (2005) ʻThe Trust/Control Duality: An Integrative Perspective on Positive Expectations of Others', International Sociology, 20, 3.

- Nakhaie, R. & de Lint, W. (2013) ʻTrust and Support for Surveillance Policies in Canadian and American Opinion', International Criminal Justice Review, 23, 2.

- Newton, K. (1997) ʻSocial Capital and Democracy', American Behavioral Scientist, 40, 5.

- Newton, K. & Zmerli, S. (2011) ʻThree Forms of Trust and Their Association', European Political Science Review, 3, 2.

- Offe, C. (1999) ʻHow Can We Trust our Fellow Citizens?', in Warren, M. E. (ed.) Democracy and Trust (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Olivera, J. (2015) ʻChanges in Inequality and Generalized Trust in Europe', Social Indicators Research, 124.

- Patil, S., Patruni, B., Lu, H., Dunkerley, F., Fox, J., Potoglou, D. & Robinson, N. (2014) Public Perception of Security and Privacy: Results of the Comprehensive Analysis of PACT’s Pan-European Survey, PACT Deliverable 4.2 (Brussels, RAND Europe).

- Pavone, V., Degli-Esposti, S. & Santiago, E. (2015) Key Factors Affecting Public Acceptance and Acceptability of SOSTs. SurPRISE deliverable 2.4 (Florence, European University Institute).

- Pena López, J. A. & Sánchez Santos, J. M. (2014) ʻDoes Corruption Have Social Roots? The Role of Culture and Social Capital', Journal of Business Ethics, 122, 4.

- Perry-Hazan, L. & Birnhack, M. (2016) ʻThe Hidden Human-rights Curriculum of Surveillance Cameras in Schools; Due Process, Privacy and Trust', Cambridge Journal of Education, 48, 1.

- Polanska, D. (2011) The Emergence of Enclaves of Wealth and Poverty: A Sociological Study of Residential Differentiation in Post-Communist Poland, doctoral thesis (Stockholm, Stockholm University).

- Pop-Eleches, G. & Tucker, J. A. (2011) ʻCommunism’s Shadow: Postcommunist Legacies, Values, and Behavior', Comparative Politics, 43, 4.

- Pop-Eleches, G. & Tucker, J. A. (2012) ʻPost-Communist Legacies and Political Behavior and Attitudes', Demokratizatsiya, 20, 2.

- Pop-Eleches, G. & Tucker, J. A. (2013) ‘Associated with the Past? Communist Legacies and Civic Participation in Post-Communist Countries', East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 27, 1.

- Putnam, R. D. (1993) Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press).

- Rose, R. (2001) ʻWhen Government Fails. Social Capital in Antimodern Russia', in Edwards, B., Foley M. W. & Diani, M. (eds) Beyond Tocqueville: Civil Society and the Social Capital Debate in Comparative Perspective (Hanover, NH, University Press of New England).

- Rothstein, B. & Eek, D. (2009) ʻPolitical Corruption and Social Trust', Rationality and Society, 21, 1.

- Rothstein, B. & Stolle, D. (2008) ʻThe State and Social Capital: An Institutional Theory of Generalized Trust', Comparative Politics, 40, 4.

- Rus, A. & Iglič, H. (2005) ʻTrust, Governance and Performance: The Role of Institutional and Interpersonal Trust in SME Development', International Sociology, 20, 3.

- Sapsford, R. & Abbott P. (2006) ʻTrust, Confidence and Social Environment in Post-Communist Societies', Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 39, 1.

- Sojka, A. (2013) Poland—A Surveillance Eldorado? Security, Privacy, and New Technologies in Polish Leading Newspapers (2010–2013), Discussion Papers 2013/6 Prague SECONOMICS (Prague, Prague Graduate School in Comparative Qualitative Analysis).

- Sønderskov, K. M. & Dinesen, P. T. (2016) ʻTrusting the State, Trusting Each Other? The Effect of Institutional Trust on Social Trust', Political Behavior, 38, 1.

- Sorell, T. (2011) ʻPreventive Policing, Surveillance, and European Counter-Terrorism', Criminal Justice Ethics, 30, 1.

- Steinfeld, N. (2017) ‘Track Me, Track Me Not: Support and Consent to State and Private Sector Surveillance’, Telematics and Informatics, 34, 8.

- Svenonius, O. & Björklund, F. (2018) ʻExplaining Attitudes to Secret Surveillance in Post-Communist Societies', East European Politics, 34, 2.

- Svenonius, O. & Björklund, F. (nd) ʻLessons from the Past: Long-term Effects and Legacies from Communist Surveillance', unpublished manuscript.

- Svenonius, O., Björklund, F. & Waszkiewicz, P. (2014) ʻSurveillance, Lustration and the Open Society: Poland and Eastern Europe', in Boersma, K., van Brakel, R., Fonio, C. & Wagenaar, P. (eds) Histories of State Surveillance in Europe and Beyond (New York, NY, Routledge).

- Svenonius, O., Björklund, F. & Waszkiewicz, P. (2015) Like Fish in Water (LFiW) Data Set (Huddinge, Södertörn University).

- Székely, I. (ed.) (1991) Information Privacy in Hungary—Survey Report and Analysis (Budapest, Hungarian Institute for Public Opinion Research), available at: https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/bitstream/handle/1974/7661/Information_Privacy_in_Hungary.pdf?sequence=18%26isAllowed=y, accessed 29 September 2019.

- Szrubka, W. (2013) ʻVideo Surveillance and the Question of Trust', in Björklund, F. & Svenonius, O. (eds).

- Uslaner, E. M. (2000) ‘Producing and Consuming Trust’, Political Science Quarterly, 115, 4.

- Uslaner, E. M. (2002) The Moral Foundations of Trust (New York, NY, Cambridge University Press).

- Uslaner, E. M. (2013) ʻTrust as an Alternative to Risk', Public Choice, 92, 3/4.

- Van der Meer, T. & Hakhverdian, A. (2017) ʻPolitical Trust as the Evaluation of Process and Performance: A Cross-National Study of 42 European Countries', Political Studies, 65, 1.

- Waszkiewicz, P. (2011) Wielki Brat Rok 2010. Systemy monitoringu wizyjnego—aspekty kryminalistyczne, kryminologiczne i prawne (Warsaw, Wolters Kluwer Polska).

- Watson, H., Finn, R. L. & Barnard-Wills, D. (2017) ʻA Gap in the Market: The Conceptualization of Surveillance, Security, Privacy and Trust in Public Opinion Surveys', Surveillance & Society, 15, 2.

- Watson, H. & Wright, D. (eds) (2013) Report on Existing Surveys. Deliverable 7.1, PRISMS Project (Karlsruhe, Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI).

- Welzel, C. & Delhey, J. (2015) ʻGeneralizing Trust: The Benign Force of Emancipation', Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46, 7.

- Wittenberg, J. (2015) ʻConceptualizing Historical Legacies', East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 29, 2.

- Wollebaek, D., Lundåsen, S. W. & Trägårdh, L. (2012) ʻThree Forms of Interpersonal Trust: Evidence from Swedish Municipalities', Scandinavian Political Studies, 35, 4.

- Yamagishi, T. & Yamagishi, M. (1994) ʻTrust and Commitment in the United States and Japan', Motivation and Emotion, 18, 2.

- Zmerli, S. & Newton, K. (2008) ʻSocial Trust and Attitudes Toward Democracy', Public Opinion Quarterly, 72, 4.

Appendix 1.

Non-responses

The response rates differ between the three countries, with Estonia having the highest rate, 72.5%, followed by Serbia 61.7% and Poland 35.4%. Thus, Poland deviates markedly from the other two. However, this is not a unique problem, as other surveys also had low response rates in Poland. See for example, the EU FRA study on violence against women (Citation2014) and Life in Transition II carried out by IPSOS (Citation2011). One reason for low response rates in Poland may be that it is comparatively harder to reach respondents in this country due to the organisation of residential areas. The presence of gated or guarded housing is more common in Poland than in comparable countries (Polanska Citation2011; Johnsson Citation2012). See also Svenonius and Björklund (Citation2018) for further discussion.

TABLE A1 Response Rate (AAPOR System)

Imputation of data

To compensate for missing data, specifically concerning the income variable, values were imputed based on age, gender, education, employment and type of settlement (urban/rural using STATA 15’s multiple imputation commands). Imputation is a process whereby missing data are estimated based on other variables and artificially imputed into the dataset. The new data do not deviate from the pattern of the other variables. In order to avoid random deviations, STATA’s imputation command created a series of datasets that are each a little different. In this case there are ten such datasets. Each regression analysis is carried out in every one of the parallel datasets. The result is an average between the ten parallel datasets. Because of the imputation process, the R2 values are also average approximations between the ten different regressions. While having this drawback, the imputation process allows us to work with the whole dataset instead of substantially fewer observations.

Appendix 2.

Sampling and translation of questionnaire

The survey questionnaire was translated into four languages: Estonian, Polish, Serbian and Russian. The interviews were carried out by IPSOS during winter 2014–2015 in Poland and Serbia, and in spring 2015 in Estonia. In all cases, the study applied a three-stage random sampling procedure. In Estonia, the first stage was carried out using population records. In Poland, NUTS-5 regions were used, and in Serbia, polling-station data. The second stage was a random walk where respondents in each household were selected on the last birthday principle. In each case it was possible to generate a probabilistic sample. Respondents were interviewed face-to-face for 15–20 minutes.

Appendix 3.

Distribution of GST after PST and PST after GST in the entire dataset

Each of the variables were computed into three values: low, medium and high. Low and high consist of the four lowest and the four highest values respectively in the original dataset. Medium covers the values in between.

Appendix 4.

Survey items included in the analysis

Appendix 5.

Linear regression coefficients and standard errors for models 1–5: concern about open surveillance

ANOVA test for the full models:

Estonia: F(7,866.8) = 14.59; Prob > F = 0.0000.

Poland: F(7,877.4) = 7.49; Prob > F = 0.0000.

Serbia: F(7,904.3) = 5.35; Prob > F = 0.0000.

TABLE A2 Estonia

TABLE A3 Poland

TABLE A4 Serbia

Appendix 6.

Linear regression coefficients and standard errors for models 1–5: worries about secret surveillance

ANOVA test for the full models:

Estonia: F(7,867.4) = 11.31; Prob > F = 0.0000

Poland: F(7,871.0) = 4.99; Prob > F = 0.0000

Serbia: F(7,908.4) = 5.18; Prob > F = 0.0000

TABLE A5 Estonia

TABLE A6 Poland

TABLE A7 Serbia