Abstract

We studied prewar public discourse by analysing the origin, content and sentiment of more than 4,000 letters written by people from all walks of life and published in the Belgrade broadsheet Politika loyal to the regime of Slobodan Milošević during the three years directly preceding the Yugoslav wars. Our analysis combined lexicon-based tools of automated topic and sentiment analysis with data on the sociodemographic characteristics of the letter writers and their localities. The results of our analysis show the importance of the politicisation of a history of violence in shaping public discourse in the run-up to war.

In the run-up to armed conflict, the tone and content of public discourse go through a marked change. The image of the nation’s, ethnic group’s or ruling regime’s real and imagined opponents is transformed into that of ‘others’, undeserving of empathy or compromise. Past relations with these opponents are cast in dark tones with a rise in references to times of conflict and violence rather than cooperation and peace. The gatekeepers of public discourse, usually in the media or the ruling regime, in these pre-conflict circumstances solicit and privilege certain kinds of voices in order to promote the discursive spiral of dehumanisation and recrimination. This process of pre-conflict public discourse ‘othering’—a form of negative political campaigning with the greatest possible stakes—has been observed in virtually all social and historical contexts in which armed conflicts occur: from the clashes between the Kikuyu and the Kalenjin tribes in Kenya (Buyse Citation2014) through the conflicts in the Caucasus (Garagozov Citation2012) to the United States’ ‘war on terror’ and its military operations in the Middle East (Merskin Citation2004).

Although public discourse is by nature a form of social interaction between the holders of political power and the general public, studies of public discourse in pre-conflict and conflict societies usually focus on the political elites without acknowledging much of a role for the general public in the creation and evolution of public discourse (Merskin Citation2004; Ryan Citation2004; Hogenraad Citation2005; Reese & Lewis Citation2009; Esch Citation2010; Kettell Citation2013). Such an approach creates an incomplete picture. The social distribution of interaction with, input into and support for a negative campaign against national, ethnic or political opponents in the run-up to armed conflict is obviously not uniform. But what are the determinants of this social distribution? What kind of voices are brought to the public’s attention and become sources of public discourse in the run-up to conflict? What kind of personal or social contexts do they come from? What kind of discourse do they ultimately present to the public? And, how do they use the past to solicit support for current political campaigns that potentially lead to armed conflict?

We answered these questions by analysing the origin, content and sentiment of a corpus of more than 4,000 readers’ letters published on the pages of the Belgrade newspaper Politika in the three years directly preceding the Yugoslav wars. In the summer of 1988, the editors of Politika, who were politically appointed and loyal to the regime of Slobodan Milošević, opened the pages of Yugoslavia’s oldest and most respected broadsheet to its readers in a section titled ‘Echoes and Reactions’ (Odjeci i reagovanja). Over the 33 months that followed, the public was exposed to a deluge of attacks, accusations, denunciations and tirades—most often against the opponents of the Milošević regime—written by people from all walks of life and read and discussed widely among the Serbian public (Mimica & Vučetić Citation2001). ‘Echoes and Reactions’ was an essential tool of the regime in the build-up of the populist and nationalist frenzy which consumed Serbian society in the months and years preceding the onset of armed conflict. Crucially, however, it was more than just a tool of the political power holders. ‘Echoes and Reactions’ was the product of the newspaper readership, embodying the interaction between the regime and media gatekeepers, on the one hand, and the general public on the other.

The analysis presented here combines our close reading of the entire corpus, lexicon-based tools of automated topic and sentiment analysis of the letters’ content, a database of biographical information we were able to collect on the letters’ more than 2,000 authors from public sources, and sociodemographic and economic data of the authors’ geocoded locations of origin. Our approach represents a significant and novel contribution to the field, as there have been no other studies using this combination of methodological tools on any similar corpus of text. The results of our analysis demonstrate convincingly that the vital determinant of the corpus’s nature and tone was the country’s World War II past, which acted as a frame and a reference point for the conflicts which took place in the late 1980s and were still to come in the 1990s. The geographic distribution of the letters’ authors was fundamentally determined by the patterns of ethnicity and World War II violence, as letters disproportionally came from communities populated by Serbs and with higher proportions of people involved in World War II combat as partisans. The sentiment analysis of the letters, on the other hand, shows that negative discourse came predominantly from authors who were either themselves World War II veterans of partisan resistance or who came from communities with high proportions of World War II partisan combatants and which were at the same time harder hit by Yugoslavia’s economic crisis. The narratives of interethnic strife in World War II—almost uniformly consisting of stories of violence perpetrated against the Serbs or of various forms of betrayal suffered by the Serbs at the hands of Yugoslavia’s other nations—were being grafted onto contemporary conflicts in order to explain and justify what was happening and what was yet to come. It was a perfect example of a violent past becoming present in public discourse. This dynamic of (ab)uses of World War II past in Yugoslavia on the brink of its collapse has been noted in a string of studies of media discourse (Kolstø Citation2009), historical cultures (Sindbæk Citation2012), intellectual elites (Dragović-Soso Citation2002) and practices of public memory and commemoration (Verdery Citation1999) in late Yugoslav socialism. Using a novel application of the tools of quantitative discourse and statistical analysis, we validated and built on those previous findings, making an important substantive and methodological contribution not only to conflict studies but also to the history of Yugoslavia and its dissolution.

Conflict and public discourse: negativity and history in context

All crises change public discourse, particularly if they involve the prospect of armed conflict. Narratives are created in order to make sense of distressing unfolding events and issues. Rivals become cast in a negative light and the conflict becomes framed in ways that often distort the record of inter-group relations. Contemporary troubles are presented as a natural consequence of a history of disputes and betrayals. A vast literature has provided ample evidence for this process of ‘othering’ and the uses and abuses of the past to justify the present in a variety of historical and social contexts. For example, the decline in the political leaders’ discourse of affiliation with members of the opposing group and the rise in their discourse of power (McClelland Citation1975) has been shown to be a solid predictor of armed conflict in international crises ranging from World War I to the Russian attack on Georgia in 2008 (Hogenraad Citation2005; Hogenraad & Garagozov Citation2010). Public discourse by religious leaders in Israel has been shown to be highly responsive to the evolution of relations with the Palestinians, turning markedly more nationalist in times of conflict (Freedman Citation2019). Soviet-era histories of interethnic relations and legal development have been transformed to justify post-Soviet wars (Garagozov Citation2012). All sides of the debate in the United States Congress prior to NATO’s Operation Allied Force and the 1999 bombing of Serbia and Montenegro engaged in a discursive ‘war of historical metaphors’ to justify their political positions and frame the underlying conflict for the public (Paris Citation2002). History, political myths and racial stereotyping were invoked by the Bush administration and the pliant US media in the run-up to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (Bostdorff Citation2003; Merskin Citation2004; Ryan Citation2004; Esch Citation2010). Most relevantly, media studies of the former Yugoslavia and its successor states show a gradual ethnicisation of the process of othering, where public narratives during the conflicts of the 1990s steadily became defined in national/ethnic terms (Kolstø Citation2009). As Dragojević (Citation2019) has shown in her recent study of the microdynamics of violence during the war in Croatia, this process of ethnicisation originates in the discourse of political leaders and in media representations, and culminates in the use of violence as a political strategy. Regardless of context, it is safe to say that in times of crisis—particularly if there is potential for events to turn towards armed conflict—public discourse related to projected opponents turns into an amplified negative political campaign.

Contemporary news media and political campaigns are negative even in peaceful times, let alone in the run-up to armed conflict. Although nearly all genres of language have more words that carry positive rather than negative sentiment (Proksch et al. Citation2019), there is consensus in the literature that media coverage in democratic polities, and most notably in the United States, is increasingly negatively biased in the twenty-first century (Soroka Citation2012, Citation2014; Soroka & McAdams Citation2015). Some have argued that the source of this bias lies in the combination of the organisational format of mass production of contemporary news content and the inherent biases of the media gatekeepers—journalists, editors, media owners—who push for content skewed toward sensationalism, conflict and negativity for their own narrow political ends (Shoemaker & Vos Citation2009). A growing body of evidence, however, shows that both news media and political campaigns are increasingly negative for a very simple reason: because it is effective and popular. Negative communication has become the dominant characteristic of modern politics, largely because voter choice is primarily rooted in negative considerations and rejection rather than endorsement of particular policies (Brie & Dufresne Citation2020). The dominance of negative over positive considerations (or of loss over gain in utility) has been confirmed in psychology (Cacioppo & Gardner Citation1999), economics (Tversky & Kahneman Citation1991) and evolutionary biology (McDermott et al. Citation2008). The steady increase in negative advertising and smear campaigns is the product of political strategists and politicians learning this lesson that negative discourse works (Geer Citation2006; Soroka & McAdams Citation2015; Haselmayer et al. Citation2019). The same can be said of media content. News coverage is negative because it is created by negatively biased humans for negatively biased humans (Soroka Citation2014).

The social consequences of this bias toward the negative have been disastrous. In the US context, it has been argued that the reliance of the mass media on ‘problem frames’ and the language of fear has led to the transformation of America’s political and popular culture into one driven by fear (Altheide Citation1997). Experimental studies have shown that the increase even in mildly violent political public discourse by the US elites can lead to an increase in support for political violence, especially among aggressive individuals (Kalmoe Citation2014). The language of aggression tends to prime aggression in aggressive partisans, leading to greater intransigence on party positions and greater party polarisation (Kalmoe et al. Citation2018). The role played in this process by the notoriously partisan and increasingly uncivil US media cannot be overstated. Tuning into such content leads media consumers to turn themselves into (re)producers of uncivil discourse (Gervais Citation2014) and increases their propensity to view the ‘other’ side more negatively and to be less supportive of compromise and bipartisanship (Levendusky Citation2013). In social contexts of armed conflict, these dynamics can be even more poisonous. For example, chronic exposure to violence via the media has been shown to harden attitudes among Israeli and Palestinian youths toward the outgroup, as well as to increase their support for war (Gvirsman et al. 2016). The language and images of violence transmitted through the media lead to a reinforcing spiral of public acceptance and support for violence. As virtually all contributors to an edited volume on media discourses during the Yugoslav crisis and wars concluded, media was not only an indicator but also an active contributor to the explosion of discursive and real violence (Jusić Citation2009).

The empirical literature on public discourse has almost exclusively viewed public discourse as the product of a top-down relationship between the political power holders and media gatekeepers, on the one hand, and the general public on the other. Politicians, policy lobbyists, journalists, editors and media owners have commonly been seen as the producers of public discourse while the individual citizens have been seen as its consumers. This view has been partly grounded in the long tradition of public opinion research showing that people have highly malleable political opinions, if they have political opinions at all (Zaller Citation1992). Moreover, the thriving literature on ‘framing effects’ has shown convincingly that opinions can be arbitrarily manipulated by skilled opinion influencers—journalists, politicians or academics designing public opinion research experiments (Chong & Druckman Citation2007). In the context of (potential) armed conflict, this tendency to consider public discourse as a one-way street has led to the view that public discourse in pre-conflict and conflict societies differs little from propaganda. Such a view, however, is incomplete. Although public discourse is heavily influenced by media gatekeepers and political power holders, it is ultimately the product of their interaction with the general public. Individual citizens can contribute to and shape public discourse. This was always the case, but it is increasingly so with the advent of new technologies, the democratisation of public access to media outlets, and the blurring of lines between media consumers and producers. As a new wave of scholarship shows, this was also the case in Yugoslavia’s late socialism, with the events being driven in the process of active interaction between members of the discontented public and political power holders (Vladisavljević Citation2008; Grdešić Citation2019; Musić Citation2019).

What is crucial to note here is that the distribution of the general public’s active interaction with and contribution to public discourse is not uniform. People’s individual and contextual characteristics matter. Freedman (Citation2019), for example, showed that nationalist rhetoric by religious leaders in Israel is conditioned by the political theology of the community they belong to. Eshbaugh-Soha (Citation2010) demonstrated that the tone of local newspaper coverage of the US president depends on the political allegiance of the local media market. In her masterful study of support for ISIS in France, UK, Germany and Belgium, Mitts (Citation2019) found that social media users’ level of discursive support for the Islamic State is conditioned by the level of support for far-right parties in their localities. Voigtländer and Voth (Citation2012) demonstrated that the geographic pattern of anti-Semitic letters written to the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer between 1935 and 1938 corresponded closely to the geographic pattern of medieval pogroms against the Jews. All these disparate pieces of evidence from a variety of historical and geographic settings show that people’s interactions with and contributions to public discourse are highly contingent on local context and the associated history of political conflict. The aim of this article is to use our understanding of the historical and political context in Serbia and Yugoslavia as a whole in the late 1980s and early 1990s in order to draw broader theoretical lessons for our understanding of the evolution of prewar public discourse in general.

Setting the scene: prelude to the Yugoslav wars

The 1980s in Yugoslavia were a time of extraordinary social, political and economic upheaval. On the economic front, the decade was marked by falling incomes, rising poverty and unemployment, rampant inflation, collapsing investments and austerity in an effort to service foreign debts, all while struggling to reform the large socialist enterprises and make their products competitive on international markets (Lydall Citation1989; Archer et al. Citation2016). At the same time as Yugoslavia struggled with an economic crisis of unprecedented proportions, the political leaderships of its six constituent republics, two autonomous provinces, and the ruling League of Communists (Savez komunista Jugoslavije—SKJ) were in the midst of a protracted conflict over the country’s constitutional system, while the academic elites and the general public were engaged in an often vicious process of re-evaluation of the country’s recent past (Ramet Citation2006). In the constitutional conflict, the two principal camps could best be labelled unitarist and federalist. The unitarist camp was led by Serbia, which insisted that the solutions to the economic crisis lay in greater centralisation and in curtailing the powers of the republic’s two autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. The federalist camp, led by Slovenia, insisted that the solution to the economic crisis lay in more liberalisation and decentralisation of political and economic decision-making. In the conflict over Yugoslavia’s recent history, the primary bone of contention was the position of Serbia in Titoist socialism. Serbian academics questioned the fairness of the political system instituted after World War II and began to see it as a betrayal of the sacrifices Serbs suffered in the war, bringing the topic of genocide (almost exclusively anti-Serb and supposedly spanning centuries until the present day) to the fore of public discourse (Dragović-Soso Citation2002). Cross-ethnic cooperation under the slogan of ‘brotherhood and unity’, which brought Tito’s partisans victory in World War II, was set aside in favour of narratives of interethnic carnage where even communists of other nationalities could no longer be trusted (Banac Citation1992; Budding Citation1998). Public discourse became saturated with what Sindbæk (Citation2012, p. 12) called a ‘cardinal theme’ of World War II revision in the historical culture of Serbia’s society at the time. In other words, constitutional problems were grafted onto economic problems, and both were further grafted onto simmering long-standing national questions and conflicts that had remained unresolved over more than four decades of Yugoslavia’s socialist regime, which had come to power after the interethnic violence of World War II (Haug Citation2012).

The economic crisis and the inability of the communist leaderships of the eight republics and provinces to find credible policy solutions or to resolve the constitutional impasse steadily eroded the legitimacy of the one-party state. As was the case with other socialist countries of Eastern Europe at the time, Yugoslavia’s communists struggled to maintain control, but with one crucial difference. Yugoslav society was freer than those behind the Iron Curtain and its citizens increasingly expressed their frustrations in the form of strikes, protests and public campaigns (Archer et al. Citation2016). Particularly important was the campaign of protests by the Kosovo Serbs against their alleged discrimination at the hands of the province’s Albanian majority (Vladisavljević Citation2008). Slobodan Milošević, who was the leader of the League of Communists of Serbia at the time, recognised the mobilising power of these protests in the search for his regime’s legitimacy and for greater power in the republic and the federation. Starting in the summer of 1988, Milošević used the state and party apparatus under his control to transform the sporadic and limited protest rallies of the Kosovo Serbs into travelling mass events directed against the ‘bureaucrats’ and the party elite disloyal to him. It was the largest campaign of protests and demonstrations in socialist Eastern Europe during the late 1980s, and soon became known as the ‘anti-bureaucratic revolution’ (Ramet Citation2006). While this campaign helped him consolidate power in Serbia, it ultimately precipitated the collapse of the federal League of Communists in January 1990. In the first democratic elections, which took place in spring and autumn of 1990, the communists/socialists remained in power in Milošević’s Serbia and Montenegro, but lost in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia & Hercegovina and Macedonia. The scene was gradually being set for actual armed conflicts, which commenced in the summer of 1991.

The ‘anti-bureaucratic revolution’ would not have been possible without the critical contribution of the largest media houses, which were controlled by the Milošević regime, particularly the state-run television and the main Belgrade broadsheet Politika. Politika was the newspaper of record in Serbia, with a history of seriousness and reliability spanning more than eight decades and a readership disproportionally among the intellectual and more ideologically conservative members of the Serbian communist elite. Under the editorship of Milošević’s close associate Živorad Minović, however, it became one of the strongest weapons in the arsenal of the Milošević regime. As one of its former editors put it, Politika’s pages at the time became ‘an unrestrained eruption of not only cheap homespun pseudo-patriotism, chauvinism, and uncontrolled political gossip, but also an eruption of blind hatred towards Albanians, Croats, Muslims, Slovenes, Macedonians … and “Serb traitors”’ (Nenadović Citation1996, p. 607). One of the more notable ways in which Minović and his staff achieved that was by opening Politika’s pages to the contributions of its readership. ‘Politika has no right to think differently from the people’, Minović stated at the time (Kurspahić Citation2003, p. 46) and the section ‘Echoes and Reactions’ was the perfect means to achieve this unity of thought. Between the summer of 1988 and the spring of 1991, ‘Echoes and Reactions’ published more than 4,000 letters from readers from all sorts of backgrounds. Unsurprisingly, the initial contributions were published concurrently with the first protest of the Kosovo Serbs in the capital of Vojvodina Novi Sad in July 1988, which marked the beginning of the ‘anti-bureaucratic revolution’. The section was unceremoniously shut down in March 1991, concurrently with the wave of opposition protests against the Milošević regime on the streets of Belgrade. Apparently, the time had come for Politika to start thinking differently from the people.

Empirical propositions

Considering the historical and political context of the time when the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ corpus was created, the nature of public discourse in prewar societies, the general negative bias of the media, and the context dependency of people’s contributions to public discourse, we make two general empirical propositions. First, we expect the geographic pattern of readers’ contributions to ‘Echoes and Reactions’ to follow the geographic pattern of the dominant political conflicts of the period. The bloody interethnic conflicts in Yugoslavia during World War II became a crucial reference point for the conflicts between the Serbs and Yugoslavia’s other nations in the 1980s (Banac Citation1992; Ramet Citation2006; Sindbæk Citation2012). The history of common cross-ethnic struggle for a socialist federation during World War II was being actively redefined by Serb academics, politicians and the general public as a loss for the Serbs, who were supposedly swindled by the other nations into a union where Serbia was disadvantaged (Budding Citation1998; Dragović-Soso Citation2002). Moreover, as noted above, Yugoslavia was experiencing an unprecedented economic crisis with workers organising strikes and demonstrations of significant proportions in order to protest the dire working conditions and rising inequalities (Archer et al. Citation2016). We expected these two dynamics to be reflected in the geographic pattern of readers’ contributions. Thus, our first hypothesis (H1) was that the letters would come disproportionally from areas with a greater level of participation in World War II partisan combat and from areas with a greater level of exposure to the economic crisis.

If the past is to be called upon to make sense of and justify the present, then those who experienced the difficult past and those experiencing the difficult present are called upon to do it credibly. Furthermore, we expected the general tone of the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ corpus to be negative and believed this negative sentiment would vary in tandem with the fortunes of the ruling Milošević regime. We agree with Young and Soroka (Citation2012), who see sentiment as a central component of the empirical study of issue frames. In the framework of this article, we cannot know to what extent the letters published in ‘Echoes and Reactions’ represent the full corpus of both published and unpublished letters sent to Politika’s editors or to what extent they were chosen for publication because they served the editors’ or the ruling regime’s narrow political aims on a given day. That is why we argue that the corpus of published letters needs to be viewed as the product of both the members of the public who wrote the letters and the media gatekeepers in Politika’s editorial office who chose to publish them. It is at the same time a reflection of the full body of all written letters (which were, unfortunately, not saved for posterity in Politika’s archives) and an indication of where the editors stood at a given point in time vis-à-vis events on the ground. In other words, the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ corpus, although written by more than 2,000 people (and curated by several lower-level editors whose identities remain unknown), is a coherent body whose purpose was to frame the political situation in Serbia and Yugoslavia as a whole. Its sentiment is thus a valid proxy for how that situation was framed in the leading media house of Serbia’s ruling regime.

Crucially, however, we also expected this degree of negativity to be decisively conditional on the same political conflicts that we believed determined the geographic pattern of the letters’ origin. Considering the biographical data we collected on the letter writers, we expected the World War II legacy to be significant both at the individual author level and the level of the communities from which the authors came. Following a similar logic as above, we anticipated negative sentiment to come disproportionally from authors who either themselves experienced World War II combat, or who came from areas which participated more in World War II partisan resistance. We also expected negative sentiment to come disproportionally from authors writing from areas that experienced the economic crisis more profoundly. Our second hypothesis (H2), therefore, was that the negative sentiment would disproportionally come from authors and areas more exposed to World War II partisan combat and to the economic crisis.

Thus spoke the people: the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ corpus

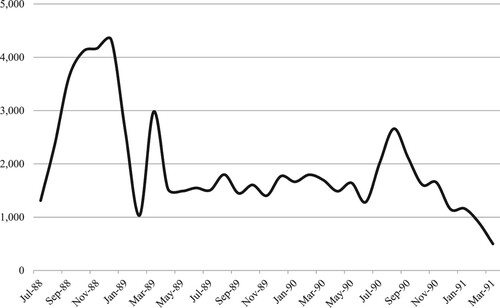

In 2001, Belgrade-based NGO Humanitarian Law Centre (Fond za humanitarno pravo—FHP) published a study accompanied by a CD presenting the readers’ letters published in ‘Echoes and Reactions’ (Mimica & Vučetić Citation2001). The CD contained an interactive archive of all published letters as well as a preliminary database of their authors. Although FHP coded and organised the meta-information for about a half of individual letter authors, thus providing a great service to the field of media studies in the region, their dataset was not error-free and their analyses were rudimentarily descriptive, leaving much work to be done. We completed that work using information in the letters as well as publicly available online sources and press coverage contemporaneous to ‘Echoes and Reactions’ for high-profile letter writers (politicians, academics, artists). We were thus ultimately able to collate the information we needed on the authors of more than 85% of the relevant letters.Footnote1 As already noted, ‘Echoes and Reactions’ was created at the onset of the wave of public rallies and protests against politicians opposed to the regime and platform of Slobodan Milošević. The distribution of letters across time reflects this fact very well, with the public outcry in the summer and autumn of 1988 and the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ section subsequently settling into its standard of two pages per day. shows the temporal distribution of sentence-based trigrams, that is, three-sentence consecutive sections extracted from the original letters published in ‘Echoes and Reactions’ across the whole period of its existence.

Newspapers in the former Yugoslavia had reader contribution sections before ‘Echoes and Reactions’, though these were usually reserved for people of social and political standing or for members of the general public who did not challenge the ruling dogmas. What distinguishes ‘Echoes and Reactions’, apart from its radical content, is that it was open to (dominantly male) readers of virtually all backgrounds. Only about 16% of the letters (and 21% of the trigrams) were written by readers with some form of higher education title (PhD, MA).Footnote2 Close to 7% of the letters were written by various groups or institutions. Fewer than 10% of the letters (and only 8% of the trigrams) were written by women. Particularly relevant to our argument is the fact that nearly 12% of the letters were written by World War II veteran partisans.Footnote3 Many of these authors offered deeply personal reflections on the events that were unfolding, making their contributions exceptionally popular (Grdešić Citation2019)—unsurprising considering recent experimental research showing the power of personalised storytelling in swaying public opinion (Gooch Citation2018).

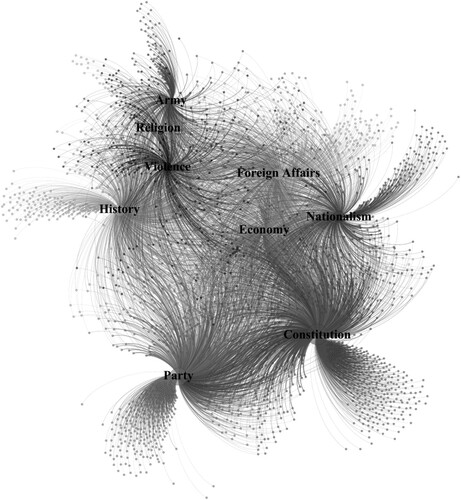

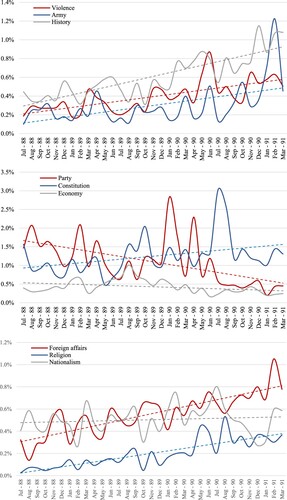

Summarising the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ corpus, with about 1.6 million words, in terms of its content was difficult because it is a mixture of overlapping topics. FHP established a scheme of letter topic allocation which we found deeply problematic and inconsistent since most letters did not neatly fit into any single topic. We needed a consistent system that would capture this dynamism, so we tried different unsupervised techniques of topic modelling such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) with Gibbs sampling. Unfortunately, none of them yielded substantively intelligible or satisfactory results. Eventually we opted for a lexicon approach based on our own close reading of the whole corpus and selection of context-relevant keywords, an approach similar to that of Aaldering and van der Pas (Citation2020). Our lexicon captures nine substantive topics we believe are interwoven throughout the corpus: Constitution, Party, History, Nationalism, Foreign Affairs, Economy, Violence, Army and Religion. We created it by first generating a frequency list of used words in our corpus and then selecting ten most typical ones for each topic (listed in Appendix ). Having the lexicon, we ran a counting algorithm, which counted numbers of times each of the selected words occurred in a letter. The word frequencies were then normalised by the overall number of words in a letter. This was done on an aggregated level for each topic per letter. The result was a vector of indexes that showed the letters’ relative links to pre-defined topics. We then used the information to illustrate these links in a graph, showing the network-like structure of letter–topic relations.Footnote4 We present these structures here in two-dimensional space in . A three-dimensional interactive model is also available online (Mochtak Citation2022).

Ultimately, however, the most important thing to understand about the content of ‘Echoes and Reactions’ is that this section reflected an interactive process between the editorial staff responsible to the editors of Politika, who were politically appointed by and loyal to Slobodan Milošević, and the public (Mimica & Vučetić Citation2001). Newspaper pages were opened to the people, ostensibly to emancipate them from the one-party political system and to provide a release valve for their frustrations, but also to harness this ‘people power’ to get rid of political opponents and to set the policy agenda in Serbia and Yugoslavia as whole. It was populism in its purest form (Grdešić Citation2019), as reflected in the contributors’ generous use of the term narod, which in Serbian means both ‘people’ and ‘nation’. The narod knew what the problems were: constitutional, political, economic, historical. The narod knew who was to blame. As one contributor to ‘Echoes and Reactions’ put it, in 28 November 1988:

In the section ‘Echoes and Reactions’ our man and his soul have spoken … . [Here] one will find the names of those who contributed to our current condition and who have been seen through by the narod. Together will be listed the names of provocateurs, cowards, armchair politicians, thugs, hypocrites, irreplaceable demagogues, and all others who brought us to the wall.

The political geography of the letters

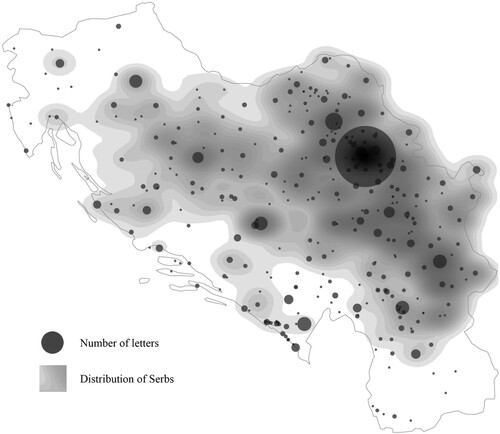

Politika may be the oldest running newspaper in the Balkans with a regional reach, but it is a Belgrade paper published in Cyrillic script with an overwhelmingly Serb readership. , where we map the geographic distribution of letters together with the geographic distribution of Serbs in Yugoslavia, provides rather convincing (if only correlational) evidence for this conclusion.

Our analysis of the geographic origin of the letters and their local contextual determinants, however, went further than superimposing the letters’ geocoded locations and the distribution of ethnicity on the map of Yugoslavia. We collected a string of economic and sociodemographic variables on the level of the federation’s nearly 500 municipalities and analysed them in a sequence of fractionalised logit regression models (Papke & Wooldridge Citation1996). We used fractional logit models for our multivariate regression analyses since our dependent variable, ‘Letters per capita’ (representing the number of letters per municipal population), was a proportional variable distributed on a unit interval (0, 1).

We modelled the state of the local economy with two variables, ‘Unemployment’ and ‘Investments’, representing the municipal unemployment rate recorded in the 1991 census (the closest reliable unemployment figures available) and the monetary value of economic investments by socialist enterprises and the government per capita in 1989, as the central year of the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ corpus. Per our first hypothesis (H1), we wished to test whether the state of the local economy (proxied by the unemployment figures) or the response by the socialist system to the economic crisis (proxied by the investment figures) had an impact on the propensity of the local population to write letters to Politika. As robustness checks, we also tested the models with other specifications of investment figures and whatever other economic variables were available for the period on the municipal level (such as government spending on health and education, salaries of workers employed in a municipality, and productivity of the local state sector), but due to their lower reliability, caused in part by flawed public statistics in the environment of high inflation, and the lack of any impact on our models, we chose not to include them. We modelled the participation of the municipal population in World War II resistance with our variable ‘World War II combat’, which captured the proportion of the municipal population receiving pension or disability benefits as partisan veterans of World War II (Savezni zavod za statistiku Citation1985). As control variables, we used ‘Education’, which represented the average number of years of schooling of the adult municipal population in the 1981 census (census figures for 1991 were not collected or estimated in Kosovo), as well as the municipal ethnic distribution, captured by the proportions of all major Yugoslav ethnic/national groups and the Ethnic Polarisation Index (EPI) as an indicator of possible local ethnic conflict (Montalvo & Reynal-Querol Citation2005). All models also included republic/province dummies as a form of control for media markets, though the results remained substantively the same if they were excluded. The results also remained substantively the same if we used ordinary least squares (OLS).

We present the results of our analysis in (full results, including republic/province controls, are available in the Appendix). The Table lists marginal effects for ease of interpretation.

TABLE 1 Contextual Determinants of Letter Origin

Three things stand out immediately from the results. Firstly, and most significantly, the results of our analysis confirm the first half of our first hypothesis (H1) and show that the letters disproportionally originated in areas whose populations participated more in World War II partisan resistance. Throughout this period, the narrative of common cross-ethnic struggle for a socialist federation during the war was being actively redefined in Serb society, turned into a narrative of World War II interethnic carnage followed by a postwar swindle supposedly perpetrated by the non-Serb communists in the form of a federal union in which Serbia was disadvantaged. This was in fact the ‘cardinal theme’ in Serbia’s public discourse at the time, dominated by literary and historiographical contributions revising the dominant post-World War II socialist narratives (Dragović-Soso Citation2002; Sindbæk Citation2012) and is reflected in the geographic pattern of readers’ contributions to ‘Echoes and Reactions’. Readers in areas with higher levels of participation in World War II partisan resistance, many of them World War II partisan veterans themselves, actively contributed to the perpetuation of this narrative. They offered backing for the activities of prominent members of the Serbian intellectual elite, ostensibly using their first-hand experiences of combat and building a socialist Yugoslavia in the immediate postwar period. The economic circumstances of the local context, by contrast, had no bearing on the geographic distribution of the letters.

Secondly, the letters originated disproportionally from areas with higher levels of education. This is unsurprising since newspaper readership and consequent interaction with the public discourse employed in the newspapers is likely to be higher in areas with better-educated populations and, as mentioned previously, Politika was an elite publication. Nevertheless, it is a lesson that is worth being mindful of: public discourse in the media is generally determined by the educated classes who run such outlets or own them. Finally, the ethnic dimension of the distribution of letters was clear and as expected: the letters mostly came from areas populated by Serbs. This was also to be expected, considering that Politika, despite its regional reach, is a Serb newspaper with dominantly Serb readership. Nevertheless, this result is notable because it signifies the extent to which ‘Echoes and Reactions’ was a mono-ethnic echo chamber, devoid of input by members of other Yugoslav nations. As Hayes and Guardino (Citation2011) have demonstrated, using the example of the US and the Second Iraq War, foreign dissenting voices can have an impact on public opinion. In ‘Echoes and Reactions’, non-Serb dissenting voices were virtually non-existent.

Individual and contextual sources of negative sentiment

After demonstrating that the letters’ origin was decisively determined by ethnicity, education and the level of the local population’s participation in World War II partisan combat, we turn our attention to explaining the sources of negativity in the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ corpus. On this front, we expected the level of negativity to be decisively conditional on the same political conflicts—the legacy of World War II and the economy—that we believed were affecting the geographic pattern of the letters’ origin. We tested this hypothesis with automated sentiment analysis of all letters in our corpus. With the advent of new technologies and methods, automated sentiment analysis has in recent years become a staple of research in virtually all social sciences, from economics (Bollen et al. Citation2011; Gade et al. Citation2013; Soroka et al. Citation2015) through political science (Soroka Citation2012; Mitts Citation2019; Proksch et al. Citation2019; Brie & Dufresne Citation2020) to sociology (Evans & Aceves Citation2016).

Our approach was based on a sentiment lexicon trained on a Croatian corpus (with excellent correspondence to Serbian) which consists of two lists of words each containing approximately 37,000 lemmas (dictionary base forms of words) ranked by their positivity and negativity. The ranks were created automatically based on small positive and negative seed sets and co-occurrence frequencies, using the PageRank algorithm (Glavaš et al. Citation2012). In order to use the lexicons, we lemmatised the letters, so the actual counting was based on a comparison between lemmas. To do so, we used a Python tagger and lemmatiser for Croatian, Slovene and Serbian (Agić et al. Citation2013). The results were stored in a data frame with all metadata defining the original letters, including the string of contextual variables introduced in the previous section, as well as the sociodemographic information on the letter writers that we had managed to collect. The final step was the counting algorithm which assessed the overall polarity of the letter. This—the ‘letter sentiment polarity’—is the dependent variable in our analysis. It refers to a positive or negative polarity of a given letter, defined as the sum of cosine distances of all words in the letter as represented in the positive sentilex dictionary, minus the sum of cosine distances of all words in the letter as represented in the negative sentilex dictionary. Recent research has demonstrated the reliability of lexicon-based sentiment analyses to be comparable to that of studies using manual coding (Brie & Dufresne Citation2020). We should say here that, as a robustness check, we performed all our analyses with sentence-based trigrams as units of analysis. Substantively we achieved nearly identical results.

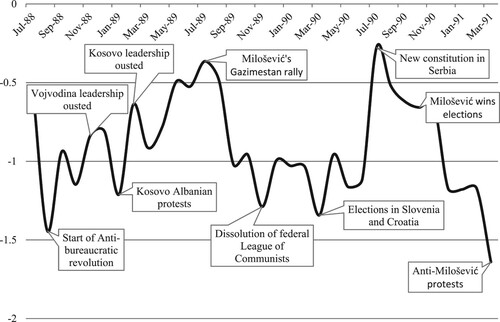

As we remarked in the introduction, ‘Echoes and Reactions’ was notable as a collection of attacks, accusations, denunciations and tirades against various opponents of the Milošević regime. This overall tone is reflected in the sentiment polarity scores of the letters with the average ‘letter sentiment polarity’ being −0.88 and the average monthly sentiment polarities of the corpus varying between −0.28 and −1.64.Footnote5 As we suggested, the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ corpus is indeed characterised by overall negative sentiment. It was, for all intents and purposes, a form of a negative political campaign against the real or imagined opponents of the Milošević regime. We traced the evolution of average monthly sentiment polarities in to assist our discussion of how the level of overall negativity varied with the fortunes of the regime. The figure also shows time stamps of what we see as ten crucial turning points in the events in Yugoslavia throughout the life of ‘Echoes and Reactions’, based on our close reading of the corpus and a broad literature on this period of Yugoslavia’s history (Ramet Citation2006; Vladisavljević Citation2008; Glaurdić Citation2011; Grdešić Citation2019). The five peaks all represent Milošević’s successes during this time: the overthrow of the disloyal leaderships of Vojvodina and Kosovo; his speech at the Gazimestan rally on 28 June 1989 in front of more than one million spectators; the promulgation of the new constitution of Serbia which de facto ended Kosovo’s and Vojvodina’s autonomy; and the victory of his party in Serbia’s first democratic elections in November 1990. The five valleys, on the other hand, mark the outpouring of negative sentiment against the Vojvodina leadership at the outset of the ‘anti-bureaucratic revolution’; the protesting Kosovo Albanians in early 1989; Milošević’s opponents in the federal League of Communists in advance of the party’s 14th Congress where its federal organisation effectively collapsed; nationalist parties during the electoral campaign in Slovenia and Croatia; and, finally, anti-Milošević demonstrators and opposition leaders in March 1991.

Our analysis of the letters’ sentiment, however, went beyond tracking their peaks and valleys in tandem with the concurrent events in Yugoslavia. In addition to the contextual municipality-level variables introduced in the previous section, we collected individual-level data on gender, higher education, World War II partisan veteran status, and group authorship for over 85% of the relevant letter writers. We tested the relationship of these data with the letters’ sentiment in a string of multi-level models, individual letters being embedded within authors who are further embedded within municipalities. We present the results of our analysis in with ‘Letter sentiment polarity’ as our dependent variable throughout. Model 1 presents the impact of ‘technical’ variables such as time (here defined as day count from the launch of ‘Echoes and Reactions’), the number of letters the author had published in ‘Echoes and Reactions’ and the word count of the letter. Model 2 tests the comparative impact of the four author-level demographic variables: gender, higher education, World War II partisan veteran status and group authorship. Models 3 and 4 look at the municipality-level variables introduced in the previous section, with Model 4 crucially interacting the variables ‘World War II combat’ and ‘Unemployment’ to discern whether their effect was interrelated. Finally, Model 5 combines all these variables. All models have republic/province controls for media markets, as well as controls for the nine topics identified above. This was a crucial piece of our puzzle because we wanted to establish, for example, whether World War II partisan veterans or people from areas disproportionally participating in World War II partisan resistance wrote more negatively in general or simply because they wrote about topics such as History or Violence. The full results of the models presented in , including republic/province and topic controls, are available in the Appendix. As a robustness check, we tested the same models with OLS and achieved substantively nearly identical results.

TABLE 2 Determinants of Letter Sentiment Polarity

The results of Model 1 show that the ‘technical’ characteristics of the letters matter. Time has a positive relationship with sentiment, though this effect is not robust to the exclusion of topic controls when it becomes insignificant. This is the case because topics carrying more negative sentiment appeared more often later in the life of ‘Echoes and Reactions’. We present the prominence of our nine topics over time graphically in the Appendix. Immediately apparent are the peaks and valleys in different topics in tandem with the events (for example, the party was prominent during the 14th Congress of the League of Communists in January 1990; the Constitution was prominent during the constitutional changes in Serbia in the summer of 1990). What is also immediately apparent is the clear upward trend over time in the topic History, which has the strongest correlation with negative sentiment across the whole corpus. In other words, history was becoming increasingly politicised and was used to explain, frame and justify contemporary events as the conflicts that ultimately led to war were intensifying. This is a clear validation of a string of research on the increasing social importance and intensity of the history of World War II violence in Serbia’s historical culture and practices of public memory and commemoration at the time, instigated primarily by the members of the Serbian intellectual elite (Verdery Citation1999; Dragović-Soso Citation2002; Sindbæk Citation2012). The results of Model 1 also show that authors who wrote multiple letters and those who wrote longer letters were more likely to be the sources of negativity, though only the latter effect (letter length) survived the inclusion of all other variables in Model 5. This effect was not only highly statistically significant but also substantively sizeable. One standard deviation increase in ‘Word count’ (equal to 291 words) meant a decrease of 0.6 in the ‘Letter sentiment polarity’. Considering that the standard deviation of the dependent variable was equal to 2.1, this was indeed a sizeable effect.

Author-level variables also proved highly revealing. Gender narrowly missed out on statistical significance, though it achieved it at the 5% level if we excluded topic controls. Women were less prone to engage in negative discourse, though this was likely due to their choice of topics. There is, on the other hand, no need to qualify the findings on ‘Higher education’ and ‘World War II veteran’. Letter writers with higher degrees were more likely to engage in negative discourse, as were World War II partisan veterans. The effect of ‘Higher education’ disappeared in the full model, but solely on account of the variable ‘Word count’. In other words, authors with higher degrees were more likely to write longer and more negative letters. Members of the academic elite—often university professors or members of the Serbian Academy of the Sciences and Arts—contributed significantly to the negative tone of ‘Echoes and Reactions’. This finding speaks directly to the seminal research of Budding (Citation1998) and Dragović-Soso (Citation2002) on the role of Serbia’s intellectual elites in the revival of Serbian nationalism in the late 1980s.

The members of the academic elite were, however, surpassed in the negativity of their discourse by the World War II partisan veterans. The effect of an author’s ‘World War II veteran’ status survived the inclusion of all other variables in Model 5 and was substantively large. The sentiment polarity of a letter from a World War II partisan veteran was, all else equal, lower by 0.65 (the standard deviation of sentiment polarity, once again, being 2.1) than that of a letter from a non-veteran. This finding went some way toward confirming our second hypothesis (H2) related to negative discourse, namely that it was conditioned by an author’s individual-level World War II experience.

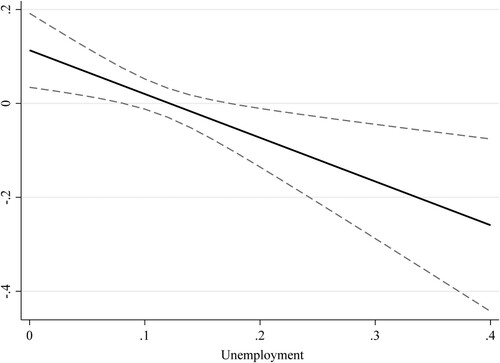

Models 3 and 4 tested the impact of the contextual municipality-level variables on sentiment polarity. Similar to Model 2, they showed that negative discourse was more likely to come from municipalities with better-educated populations. More letters and more negative public discourse came from these areas. Model 3 also showed that negative discourse was more likely to come from areas with higher unemployment, which means that the economic crisis did contribute to the appearance of negative sentiment in public discourse. This was an additional piece of the puzzle in the confirmation of our second hypothesis (H2). As Model 4 showed, however, this effect was compounded by the municipalities’ level of participation in World War II partisan combat. In other words, such participation had a negative effect on sentiment polarity only in areas where the economic crisis was worse and actually had a positive effect on sentiment polarity in areas where the economic crisis was not so severe. To be more precise, using the average marginal effects figures from Model 5 where this relationship survived and was also highly statistically significant, ‘World War II combat’ turned negative at around a 12% rate of unemployment, which was just about the average rate of municipal unemployment for the whole of Yugoslavia at the time, as well as for the 226 municipalities associated with the letters in our corpus. In areas with below-average unemployment, a history of World War II partisan resistance led to more positive public discourse, while in areas with above-average unemployment, such a history led to more negative discourse. The economic crisis and the history of World War II were becoming deeply intertwined. One could say that if socialist Yugoslavia fulfilled the economic needs of an area whose population fought for it in World War II, people from this area were less likely to engage in the negative campaign against the opponents of the Milošević regime. On the other hand, if socialist Yugoslavia economically failed the local population, they were more likely to engage in such a negative campaign. In many ways, it is understandable that the dependence of public discourse on economic performance was contingent on the communities’ deep and historically rooted commitment to the country and its system. If a community fought for socialist Yugoslavia in World War II and the system failed/succeeded to deliver, it was logical that members of this community would be even more negative/positive than members of communities that did not have a historically rooted commitment to the country and its system. This finding offered a nuanced partial confirmation and revision of our second hypothesis (H2) related to the letters’ sentiment polarity. We believe it also opens avenues for new and deeper research into the geographic patterns of discursive and real violence, not only in the former Yugoslavia of the 1980s and 1990s, but also in other geographic and historical contexts. We show this interactive effect of ‘Unemployment’ and ‘World War II combat’ on ‘Letter sentiment polarity’ graphically in .

Conclusions

Public discourse in the run-up to armed conflict can be best understood as a form of negative campaign against the projected opponents. This negative campaign, however, is not purely the creation of the political and media elites. Public discourse is a product of interaction between the political power holders and the general public. This is particularly the case today with the advent of new technologies and the democratisation of the media space. With this article, we aimed to show that it was also the case three decades ago on the eve of Yugoslavia’s breakup and wars. Our analysis brings the public back into prewar public discourse. In that sense, it builds on recent scholarship (Vladisavljević Citation2008; Grdešić Citation2019; Musić Citation2019) which aimed to provide correctives to narratives highlighting only the role of political leaders in the spiral towards armed conflict in the former Yugoslavia. Our analysis also shows that the social distribution of access to, interaction with, and contribution to public discourse in the run-up to armed conflict is not uniform and is an important object of study. We furthermore make an important methodological contribution to the field, as this article is first to use this combination of tools to shed light on the nature of prewar public discourse or discourse in general in a language often neglected by scholarship written in English.

People from all walks of life and from all sorts of local social contexts contributed to Politika’s ‘Echoes and Reactions’ letter pages. Some, however, contributed more, in terms of both content and the negative tone directed at the real and imagined opponents of the Milošević regime. Our analysis shows that it was those who could call upon their own personal or contextual experiences of armed conflict and interethnic strife during World War II who were significant sources of content in ‘Echoes and Reactions’. We also show that the interaction between the writers’ localities’ World War II past and their experience of the economic crisis was a crucial determinant of the letters’ level of negative sentiment. People who came from areas which disproportionally fought for a socialist Yugoslavia in World War II and which, at the same time, disproportionally bore the brunt of the 1980s economic crisis were the sources of some of the most negative discourse in ‘Echoes and Reactions’. Thus, Yugoslavia’s violent World War II past was grafted onto its devastating contemporary economic crisis, creating a poisonous blend of nationalist recriminations and resentments which led Serbian society into a series of disastrous wars.

We have no illusions about the role of the editorial staff of Politika in shaping the ‘Echoes and Reactions’ corpus and its dominant narrative. To the contrary: we can be certain that the letters published in Echoes and Reactions were not selected randomly for publication but were chosen for their content and—in the case of prominent personalities—for their authors. In our view, however, this does not detract from our effort to expose how a violent past blends with the political present in prewar public discourse. Whether one interprets our results as evidence that in prewar societies people who are prepared to speak about past conflicts based on direct experience are selected by the media gatekeepers, or as evidence that such people are more likely to volunteer their stories, is somewhat beside the point. What matters is that it is exactly those kinds of voices that disproportionally constitute public discourse in a prewar context.

That is indeed the principal lesson of our article. As we stated in the introduction, the tone and content of public discourse in the run-up to war go through a marked change. The image of adversaries is transformed into that of ‘others’, undeserving of empathy or compromise. Past relations with these adversaries become dominated by references to times of conflict and violence rather than cooperation and peace. A violent past becomes a frame for the political present. ‘Echoes and Reactions’, as a social and media phenomenon, represented a dramatic culmination of the process of change in the dominant public discourse of interethnic cooperation in Serbia’s public discourse three decades ago. The consequences were disastrous. Serbian society, as well as all other societies of the region, fell into the spiral of quasi-historical stereotypes and tropes. Many of those stereotypes and tropes dominate public discourse to this day, reinforced and ‘confirmed’ by the wave of interethnic violence of the 1990s. We hope this article helps us understand the roots of that process, so that we may better understand how postwar societies can climb out of such a spiral of negativity and aim instead for cooperation and mutual understanding.

Acknowledgement

The work for this article was supported by the ERC Starting Grant 714589; H2020 European Research Council. The authors wish to thank Rafaëlle de La Tullaye for her research assistance; participants of the Impresso Talks workshop at the University of Luxembourg for their valuable comments; and Fond za Humanitarno Pravo for access to the digitised ‘Echoes and Reactions’ archive.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Josip Glaurdić

Josip Glaurdić, Associate Professor of Political Science, Faculty of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Université du Luxembourg, Belval Campus, 2, avenue de l’Université, L-4365 Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg. Email: [email protected]

Michal Mochtak

Michal Mochtak, Institute of Political Science, Université du Luxembourg, Luxembourg. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 We disregarded 269 letters that either concerned administrative matters or expressed congratulations to Politika on its 85th anniversary in January 1989.

2 This figure is higher than the comparable figure of 5% of the adult population of Serbia holding higher education degrees in the 1991 census but is still in stark contrast to the background of people who wrote letters to Politika before ‘Echoes and Reactions’.

3 This figure is much higher than the actual number of World War II partisan veterans, which numbered some 55,000 in Serbia in 1982, namely, less than 1% of the adult population (Savezni zavod za statistiku Citation1985).

4 To be more specific, in each letter we first counted the number of words per topic as determined by our lexicon. We then normalised the count by the number of all words per letter. Finally, we filtered only those links with a relative frequency higher than 0.01. For example, say a letter contains words that belong in four topic categories (40 for Constitution, 30 for Party, 7 for Economy and 7 for History). If the letter is 1,000 words in total, its relative links to topics would be 40/1000 = 0.04, 30/1000 = 0.03, and twice 7/1000 = 0.007. The graph would then visualise only the links to Constitution (0.04) and Party (0.03) as those two are the most empirically relevant for the document. The arbitrary threshold of 0.01 was needed as the graph with all links had no clear structure and very little empirical value.

5 To provide a comparative sense of the negativity of ‘Echoes and Reactions’, we conducted the same analysis on two digitised corpora from the period which dealt with similar topics: the manifestos of the ruling League of Communists from the 1970s and 1980s, and articles published between 1988 and 1991 in Politička misao, the leading political science journal in Yugoslavia. Given the widely different lengths of documents, we conducted our analyses on the level of sentence-based trigrams. ‘Echoes and Reactions’ sentence-based trigrams had the average sentiment polarity of −0.11 and were more than twice as negative as the sentence-based trigrams in the SKJ manifestos (−0.05). The Politička misao corpus, by contrast, was positive, with the comparable sentiment polarity value being 0.02.

References

- Aaldering, L. & Van Der Pas, D. J. (2020) ‘Political Leadership in the Media: Gender Bias in Leader Stereotypes During Campaign and Routine Times’, British Journal of Political Science, 50, 3.

- Agić, Ž., Ljubešić, N. & Merkler, D. (2013) ‘Lemmatization and Morphosyntactic Tagging of Croatian and Serbian’, in Proceedings of the 4th Biennial International Workshop on Balto-Slavic Natural Language Processing, available at: https://aclanthology.org/W13-2408.pdf, accessed 28 January 2022.

- Altheide, D. L. (1997) ‘The News Media, the Problem Frame, and the Production of Fear’, The Sociological Quarterly, 38, 4.

- Archer, R., Duda, I. & Stubbs, P. (eds) (2016) Social Inequalities and Discontent in Yugoslav Socialism (London, Routledge).

- Banac, I. (1992) ‘The Fearful Asymmetry of War: The Causes and Consequences of Yugoslavia’s Demise’, Daedalus, 121, 2.

- Bollen, J., Mao, H. & Zeng, X.-J. (2011) ‘Twitter Mood Predicts the Stock Market’, Journal of Computational Science, 2, 1.

- Bostdorff, D. M. (2003) ‘George W. Bush’s Post-September 11 Rhetoric of Covenant Renewal: Upholding the Faith of the Greatest Generation’, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 89, 4.

- Brie, E. & Dufresne, Y. (2020) ‘Tones from a Narrowing Race: Polling and Online Political Communication During the 2014 Scottish Referendum Campaign’, British Journal of Political Science, 50, 2.

- Budding, A. H. (1998) Serb Intellectuals and the National Question, 1961–1991, PhD thesis (Cambridge, MA, Harvard University).

- Buyse, A. (2014) ‘Words of Violence: “Fear Speech,” or How Violent Conflict Escalation Relates to the Freedom of Expression’, Human Rights Quarterly, 36, 4.

- Cacioppo, J. T. & Gardner, W. L. (1999) ‘Emotion’, Annual Review of Psychology, 50.

- Chong, D. & Druckman, J. N. (2007) ‘Framing Theory’, Annual Review of Political Science, 10.

- Dragojević, M. (2019) Amoral Communities: Collective Crimes in Time of War (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press).

- Dragović-Soso, J. (2002) ‘Saviours of the Nation’: Serbia’s Intellectual Opposition and the Revival of Nationalism (London, Hurst & Company).

- Esch, J. (2010) ‘Legitimizing the “War of Terror”: Political Myth in Official-Level Rhetoric’, Political Psychology, 31, 3.

- Eshbaugh-Soha, M. (2010) ‘The Tone of Local Presidential News Coverage’, Political Communication, 27, 2.

- Evans, J. A. & Aceves, P. (2016) ‘Machine Translation: Mining Text for Social Theory’, Annual Review of Sociology, 42.

- Freedman, M. (2019) ‘Fighting from the Pulpit: Religious Leaders and Violent Conflict in Israel’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 63, 10.

- Gade, T., Salines, M., Glöckler, G. & Strodthoff, S. (2013) ‘“Loose Lips Sinking Markets?” The Impact of Political Communication on Sovereign Bond Spreads’, ECB Occasional Paper Series 150, available at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2291222, accessed 23 December 2021.

- Garagozov, R. R. (2012) ‘Narratives in Conflict: A Perspective’, Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, 5, 2.

- Geer, J. G. (2006) In Defense of Negativity: Attack Ads in Presidential Campaigns (Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press).

- Gervais, B. T. (2014) ‘Following the News? Reception of Uncivil Partisan Media and the Use of Incivility in Political Expression’, Political Communication, 31, 4.

- Glaurdić, J. (2011) The Hour of Europe: Western Powers and the Breakup of Yugoslavia (New Haven, CT, Yale University Press).

- Glavaš, G., Šnajder, J. & Dalbelo Bašić, B. (2012) ‘Semi-Supervised Acquisition of Croatian Sentiment Lexicon’, in Sojka, P., Horák, A., Kopeček, I. & Pala, K. (eds) Text, Speech and Dialogue (Berlin, Springer).

- Gooch, A. (2018) ‘Ripping Yarn: Experiments on Storytelling by Partisan Elites’, Political Communication, 35, 2.

- Grdešić, M. (2019) The Shape of Populism: Serbia Before the Dissolution of Yugoslavia (Ann Arbor, MI, University of Michigan Press).

- Gvirsman, S. D., Huesmann, L. R., Dubow, E. F., Landau, S. F., Boxer, P. & Shikaki, K. (2016) ‘The Longitudinal Effects of Chronic Mediated Exposure to Political Violence on Ideological Beliefs About Political Conflicts Among Youths’, Political Communication, 33, 1.

- Haselmayer, M., Meyer, T. M. & Wagner, M. (2019) ‘Fighting for Attention: Media Coverage of Negative Campaign Messages’, Party Politics, 25, 3.

- Haug, H. K. (2012) Creating a Socialist Yugoslavia: Tito, Communist Leadership and the National Question (London, I.B. Tauris).

- Hayes, D. & Guardino, M. (2011) ‘The Influence of Foreign Voices on U.S. Public Opinion’, American Journal of Political Science, 55, 4.

- Hogenraad, R. (2005) ‘What the Words of War Can Tell Us About the Risk of War’, Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 11, 2.

- Hogenraad, R. & Garagozov, R. R. (2010) ‘Words of Swords in the Caucasus: About a Leading Indicator of Conflicts’, Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 16, 1.

- Jusić, T. (2009) ‘Media Discourse and the Politics of Ethnic Conflict: The Case of Yugoslavia’, in Kolstø, P. (ed.).

- Kalmoe, N. P. (2014) ‘Fueling the Fire: Violent Metaphors, Trait Aggression, and Support for Political Violence’, Political Communication, 31, 4.

- Kalmoe, N. P., Gubler, J. R. & Wood, D. A. (2018) ‘Toward Conflict or Compromise? How Violent Metaphors Polarize Partisan Issue Attitudes’, Political Communication, 35, 3.

- Kettell, S. (2013) ‘Dilemmas of Discourse: Legitimising Britain’s War on Terror’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 15, 2.

- Kolstø, P. (ed.) (2009) Media Discourse and the Yugoslav Conflicts (Farnham, Ashgate).

- Kurspahić, K. (2003) Prime Time Crime: Balkan Media in War and Peace (Washington, DC, United States Institute of Peace Press).

- Levendusky, M. (2013) ‘Partisan Media Exposure and Attitudes Toward the Opposition’, Political Communication, 30, 4.

- Lydall, H. (1989) Yugoslavia in Crisis (New York, NY, Oxford University Press).

- McClelland, D. C. (1975) Power: The Inner Experience (New York, NY, Irvington).

- McDermott, R., Fowler, J. H. & Smirnov, O. (2008) ‘On the Evolutionary Origin of Prospect Theory Preferences’, The Journal of Politics, 70, 2.

- Merskin, D. (2004) ‘The Construction of Arabs as Enemies: Post-September 11 Discourse of George W. Bush’, Mass Communication and Society, 7, 2.

- Mimica, A. & Vučetić, R. (2001) ‘Vreme kada je narod govorio’: Rubrika ‘Odjeci i reagovanja’ u listu Politika (juli 1988.–mart 1991.) (Belgrade, Fond za humanitarno pravo).

- Mitts, T. (2019) ‘From Isolation to Radicalization: Anti-Muslim Hostility and Support for ISIS in the West’, American Political Science Review, 113, 1.

- Mochtak, M. (2022) ‘Politika Network Data Visualization’, available at https://mochtak.com/wp-content/uploads/DATA/Data_viz/Politika/Politika-Network-gjs.html, accessed 28 January 2022.

- Montalvo, J. G. & Reynal-Querol, M. (2005) ‘Ethnic Polarization, Potential Conflict, and Civil Wars’, American Economic Review, 95, 3.

- Musić, G. (2019) ‘Provincial, Proletarian, and Multinational: The Antibureaucratic Revolution in Late 1980s Priboj, Serbia’, Nationalities Papers, 47, 4.

- Nenadović, A. (1996) ‘Politika u nacionalističkoj oluji’, in Popov, N. (ed.) Srpska strana rata: Trauma i katarza u istorijskom pamćenju (Belgrade, Republika).

- Papke, L. E. & Wooldridge, J. M. (1996) ‘Econometric Methods for Fractional Response Variables with an Application to 401(k) Plan Participation Rates’, Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11, 6.

- Paris, R. (2002) ‘Kosovo and the Metaphor War’, Political Science Quarterly, 117, 3.

- Proksch, S.-O., Lowe, W., Wäckerle, J. & Soroka, S. (2019) ‘Multilingual Sentiment Analysis: A New Approach to Measuring Conflict in Legislative Speeches’, Legislative Studies Quarterly, 44, 1.

- Ramet, S. P. (2006) The Three Yugoslavias: State Building and Legitimation, 1918–2005 (Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press).

- Reese, S. D. & Lewis, S. C. (2009) ‘Framing the War on Terror: The Internalization of Policy in the US Press’, Journalism, 10, 6.

- Ryan, M. (2004) ‘Framing the War Against Terrorism: US Newspaper Editorials and Military Action in Afghanistan’, Gazette: The International Journal for Communication Studies, 66, 5.

- Savezni zavod za statistiku (1985) ‘Borci, vojni invalidi i porodice palih boraca: korisnici osnovnih prava po saveznim propisima’, Statistički bilten, 1463.

- Shoemaker, P. J. & Vos, T. (2009) Gatekeeping Theory (New York, NY, Routledge).

- Sindbæk, T. (2012) Usable History? Representations of Yugoslavia’s Difficult Past from 1945 to 2002 (Aarhus, Aarhus University Press).

- Soroka, S. (2012) ‘The Gatekeeping Function: Distributions of Information in Media and the Real World’, The Journal of Politics, 74, 2.

- Soroka, S. (2014) Negativity in Democratic Politics: Causes and Consequences (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Soroka, S. & McAdams, S. (2015) ‘News, Politics, and Negativity’, Political Communication, 32, 1.

- Soroka, S., Stecula, D. A. & Wlezien, C. (2015) ‘It’s (Change in) the (Future) Economy, Stupid: Economic Indicators, the Media, and Public Opinion’, American Journal of Political Science, 59, 2.

- Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. (1991) ‘Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice: A Reference-dependent Model’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106, 4.

- Verdery, K. (1999) The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change (New York, NY, Columbia University Press).

- Vladisavljević, N. (2008) Serbia’s Antibureaucratic Revolution: Milošević, the Fall of Communism, and Nationalist Mobilization (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Voigtländer, N. & Voth, H.-J. (2012) ‘Persecution Perpetuated: The Medieval Origins of Anti-Semitic Violence in Nazi Germany’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127, 3.

- Young, L. & Soroka, S. (2012) ‘Affective News: The Automated Coding of Sentiment in Political Texts’, Political Communication, 29, 2.

- Zaller, J. R. (1992) The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

Appendix

TABLE A1 Words Defining Topics

TABLE A2 Contextual Determinants of Letter Origin

TABLE A3 Determinants of Letter Sentiment Polarity