Abstract

Approaching populism at the intersection of ideology and discourse, in this article we analyse how politicians in Slovenia responded to migration during and after the ‘refugee crisis’ (2015–2019). Based on a frame analysis of parliamentary debates that addressed migration, we explore differences and similarities in the speeches of different politicians and identify ‘populist frames’ that reveal how various actors speak about migration. We argue that distinct features of populist communication extend from exclusionary, ethnonationalistic populist frames to inclusionary solidary discourses, reflecting the transversal political logic of populism that fits the ideological maps of political actors.

Populist imaginings of democracy have been analysed by Fareed Zakaria (Citation2007) as rising forms of ‘illiberal democracy’ when democratically elected regimes routinely ignore constitutional limits on their power and deprive citizens of basic rights and freedoms. This shift towards forms of illiberal democracy is the outcome of governments that ignore the balance of powers, attack the independence of institutions and deny the rights of minorities (Mudde Citation2004), as exemplified in Central and Eastern Europe by, amongst others, the Orbán government in Hungary and the Janša government in Slovenia. In power, right-wing populists have claimed to represent democratic and liberal values, while producing ‘captive democracies’ (Mair Citation2013) with exclusivist ethnonationalist and anti-democratic sentiment triumphing in the name of ‘the people’. On the other hand, left-wing populism builds on the ramifications of political and economic crises and the incapacity of the governing parties to address social conflicts, including the demands of campaigns in environmentalist, anti-racist, feminist and other domains (Aslanidis Citation2017). Left populism is debated as a possibility to bridge the cleavages between ‘the people’ and the elite and reclaim the people’s sovereignty from the elites (Laclau Citation2005; Gerbaudo Citation2018; Mouffe Citation2018), but a closer look reveals that the idea of ‘the people’ has always been present in the discourses of communist and socialist parties, being synonymous with the working class.

Populism emerges when there is a strong sense of crisis (Taggart Citation2004, pp. 275–76). Since 2015 we have seen how the refugee crisis has fuelled a nationalist-populist rhetoric across Europe and in particular throughout Central and Eastern Europe, with President Viktor Orbán constructing a razor wire fence along Hungary’s borders, an approach that was followed by the then ruling centrist-liberal Modern Centre Party (Stranka modernega centra—SMC) in Slovenia. Our analysis of a specific period of the ‘refugee crisis’ in the national context of Slovenia is in line with Taggart’s explanation that populism is contextually contingent and heavily coloured by its context (Taggart Citation2004, pp. 274–75). Canons of populist cases may be ‘chameleonic’ (Taggart Citation2004, p. 275) as populists take on the language of popular sovereignty across the political field, adopting left-wing and right-wing orientations and discourses.

Populism research has been on the rise over the past two decades, and a literature review shows that Mudde’s definition of populism as a ‘thin ideology’ (Mudde Citation2004) has gained the most attention, whereas still unexplored are approaches that combine an understanding of populism as ideology with discursive formation. In this article we develop this kind of intersectional analysis of populism. We suggest frame analysis as an approach, which we combine with the operationalisation of three ‘tropes’ or antagonisms of populism manifestations: people-centrism, anti-elitism and the othering (of minorities). We expect that the combination of ideologically and discursively driven analysis of populism approached through frame analysis will enable us to capture the specifics of right-wing and left-wing populism.

This article contributes to existing research by conducting a qualitative frame analysis of parliamentary debates on migration between 2015 and 2019 in Slovenia, which is located near the end of the so-called Balkan migration route. Recently, Hungary and Poland have emerged as notable examples of right-wing, ethnonationalist populism and illiberal democracy in Central and Eastern Europe (Brubaker Citation2017), while other national contexts have received less attention. Our aim, therefore, is to contribute to a better understanding of the populist shifts in the region beyond the countries of the Visegrád group. Slovenia has been predominantly a transit country during and after ‘the refugee crisis’, as is also evident in considerably lower numbers of applications for international protection (Kogovšek Šalamon Citation2019). Nevertheless, as confirmed by our analysis, populist perspectives often build on ethnonationalism. Based on a frame analysis of parliamentary debates in the Slovenian National Assembly that addressed migration, we explore the speeches of different politicians identifying distinct ‘populist frames’, revealing how various political actors spoke about migration and refugees. Our results confirm that left-wing populism exemplifies thinner populism, displaying people-centrism and/or anti-elitism compared to the right-wing variations, which also build on minority exclusion. Moreover, we see that the right-wing as well as centre-left variations of populism fit better and more fully with people-centrism compared to the political party The Left (Levica), with its class rather than ‘pure people’ focus.

Populism: intersecting ideology and discourse in party communication

Canovan’s (Citation2002) observation that populism changes in combination with other ideologies was considered by several scholars who have argued that populism is a ‘thin ideology’ (Mudde Citation2004) that functions in combination with ‘thicker’ or ‘full’ ones, such as nationalism or nativism (Pelinka Citation2013; Brubaker Citation2017). As a thin ideology populism is based on recognisable but fewer core concepts, the meanings of which are highly context-dependent (Mudde & Kaltwasser Citation2012, pp. 150–51). Stanley (Citation2008, pp. 106–8) observed that the thinness of populism means that it is a complementary ideology, which diffuses through other full, host ideologies. Freeden (Citation2002, p. 759) argued that populism, as a ‘belief system of a limited range’, ‘arbitrarily severs itself from wider ideational contexts’, while March (Citation2017) has called populism an ‘unusual ideology’, describing its pragmatism, its capacity to be appropriated for and mobilised by any political position. Taggart (Citation2004) has similarly noted the ‘chameleonic’ nature of populism, which adapts to similar impulses in different instances and in the context of different ideologies.

Following these debates, we define populism as a ‘thin ideology’ (Mudde Citation2004) and analyse how it is formed in discourses in combination with other stronger or ‘thicker’ ideologies. Further, we approach populism at the crossroads of ideology and political discourse, not contrasting, as is often the case, the classical definition of Mudde (Citation2004), who opted for an ideational approach to populism, and of Laclau (Citation2005), who prioritised the discursive structures, but reading them in parallel. We thus suggest that populism as ideology is not separate from speech but rather is shaped through it; populism is manifested in speech formations and performances. Further, our contribution to the existing research lies in our analysis of populism within and beyond party affiliations, and not focusing solely on right-wing populism, as is the case in several existing (empirical) studies published in the aftermath of Mudde’s (Citation2007) influential analysis of the populist radical right. We therefore explore the ‘transversal political logic’ (Gerbaudo Citation2018) of populism. In so doing, following March’s (Citation2017, p. 300) analysis of the differences between right-wing and left-wing populism and his ‘ideology-trumps-populism thesis’, we explore whether and in which instances host ideology is more important than populism per se in explaining the essence of left- and right-wing populism variations.

With respect to the contextual specificities of populism, Mudde and Kaltwasser (Citation2012) argued that left-wing populism in Latin America is more inclusionary compared to European or US traditions. In the UK context, March similarly found left-wing populism to be more socioeconomically focused, inclusionary and egalitarian than its right-wing counterpart (March Citation2017, pp. 283–84). The crucial part of the inclusion/exclusion differentiation relates to the manner in which populist actors define the people and the elites and other elements that are attached to populist ideology (Mudde & Kaltwasser Citation2012, pp. 148–69). Populism can thus be based on inclusionary perceptions related to liberal notions of equality, solidarity and human rights, which are, for example, evident from an inclusive idea of ‘the people’ regardless of national, ethnic and religious affiliations, class, gender, sexual orientation and other circumstances. Generally, left-wing populism is found to be ideologically more related to liberal concepts of equality, solidarity and human rights, while right-wing populism is less inclusive and foregrounds elements characteristic for the conservative right, such as an ethnonationalistic exclusionary attitude towards minorities. It should be noted, however, that the differences between right-wing and left-wing populism may not always appear as clear-cut divisions of ethnonativist populism versus more egalitarian forms.

This article explores, in the postsocialist Slovenian context, whether the left operates on the basis of class or other factors rather than on that of ‘pure people’ and whether it exhibits a different combination of populist antagonisms compared to right-wing positions. We also expect to see a certain convergence of right-wing and centrist-liberal party discourses exemplifying the fluidity of the postsocialist party system. We adopt an understanding of populism as a crosscutting ideology and discourse and analyse the colours of ‘chameleonic populism’ that develop across the political spectrum (Pajnik & Sauer Citation2018, p. 2; Pajnik Citation2019). We use frame analysis, reviewing frames as forms of explanation or as sense-making structures made by representatives of political parties on migration. We argue that populism as a political discourse develops through frames as ‘performative features’ in a stylised contemporary political landscape (Moffitt & Tormey Citation2014). Or, in other words, some frames as intentional speech formations might be more prominent for some political parties and less so for others; speech formation, we argue, is thus dependent on party ideology. We expect that the frame analysis approach will enable us to capture speech characteristics, showing different populist manifestations in relation to party ideologies. Such an approach enables us to see how populism is performed in context.

To empirically operationalise populism, we measured three populist antagonisms, presented in the literature as main populist ‘tropes’: people-centrism, anti-elitism and othering. Recent literature on populism agrees that people-centrism and anti-elitism represent two main antagonisms (Canovan Citation2002; Mudde Citation2004; Taggart Citation2004; Rooduijn & Pauwels Citation2011; March Citation2017). We have included the additional antagonism of othering in line with recent conceptualisations, namely, Jagers and Walgrave (Citation2007), Suiter et al. (Citation2018), Zulianello et al. (Citation2018) and Bobba et al. (Citation2018), which stress that the antagonism between ‘the people’ and the culprit ‘other’ constitutes a visible antagonism that should be considered in populism analysis. People-centrism in itself implies the construction of out-groups (the elites or others). Othering is a non-dispensable antagonism as our theme here is migration. However, in contrast to Suiter et al. (Citation2018) we limited othering as populist antagonism to cases where speech constructs opposition between ‘the people’ and minority groups, and not for speech that opposes elites (treated as others). Exclusionary populist communication thus builds on perceptions that some groups’ values and behaviour are opposed to ‘the people’s’ general interests. This is connected to the stigmatisation and scapegoating of such groups, which are excluded from ‘the people’, constructed as a burden on and threat to society and blamed for the problems of ‘the people’ (Jagers & Walgrave Citation2007, p. 324).

The (post)socialist legacy: populism in the Slovenian context

Brubaker (Citation2017) has determined that Central and Eastern European countries largely exhibit ‘ethno-national’ variations of populism, forming a distinct cluster that embraces securitarian and nativist attitudes towards social problems in general and minority issues in particular.Footnote1 In the postcommunist/postsocialist legacy, the nationalist portraits of ‘the people’ as a central focus of populist concern externalise liberalism, constructing it as non-national and a threat emanating from communist ideology and foreign domination. Social democrats maintain a sizable presence in several Central and Eastern European countries, although to a visibly lesser extent than in the West, and they are not necessarily significant advocates of human rights issues, while leftist and environmental/green groupings are rarely strong. The left in Central and Eastern European countries confronts similar crises as elsewhere, such as electoral defeat or stagnation and internal dissent but, in this region, they are largely formed vis-à-vis the contradictory communist and socialist legacy. Anti-communism is a constant feature of political discourse in Central and Eastern Europe, contributing to the stigmatisation and marginalisation of left-wing actors.

Right-wing populism in Central and Eastern Europe has been analysed by Ramet (Citation1999) as the rise of anti-democratic attitudes, intolerance, anti-intellectualism and the traditionalisation of society. For the Slovenian case, Rizman (Citation1999, pp. 148–49) suggested that right-wing populism rested on the narrative regarding the emergence of Slovenia as an ethnic state, exhibiting an anti-Balkan and anti-communist rhetoric that constructs the Slovenian nation by excluding ‘others’ on the basis of ethnicity, religion, gender, sexual orientation and political affiliation.

Pervasive populism in the Slovenian context was first observed in the example of the Slovenian National Party (Slovenska nacionalna stranka—SNS) and its leader Zmago Jelinčič, whose popularity was greatly boosted during the first parliamentary elections in independent Slovenia in 1992 (Rizman Citation1999, p. 151), based on advocating for the purification of the Slovenian nation from Yugoslavs, migrants and communists. The slogan ‘masters on our own land’ (gospodarji na svoji zemlji) further showed the ethnonationalist orientation of the SNS (Fink-Hafner Citation2016, p. 1331). While Jelinčič has remained a visible populist political actor, who re-entered parliament in 2018 after several years of running extra-parliamentary activities, the main orchestration of ‘nativist populism’ (Pelinka Citation2013, pp. 15–6) or ‘ethno-national populism’ (Brubaker Citation2017) has come from Janez Janša, the leader of the Slovenian Democratic Party (Slovenska demokratska stranka—SDS) since 1993.Footnote2 ‘Yesterday’s renegade’ and ‘today’s authoritarian’ (Rizman Citation1999, p. 156) Janša, who is close to the Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, and who supported the declaration of Donald Trump’s ‘victory’ in the 2020 US presidential elections, exemplifies the paradoxes of transition that have radicalised right-wing populist politics in the region since 1989 (Rizman Citation2008, p. 59).

The traditionalisation of Slovenian society, with conservative and religious actors regaining power after years of being repressed under socialism, provided a context in which populism could flourish. A combination of Christian democratic ideology and right-wing populism can be found in the Christian Democratic Party New Slovenia (Nova Slovenija—NSi), established in 2000, which has mobilised against migrants and been the main actor opposing marriage equality, reproductive rights and abortion, pursuing populism based on biological interpretations of culture and a nativist understanding of state and citizenship. Ideas of national purification were also advanced by the secret removal of more than 25,671 persons from the register of permanent residents of Slovenia back in 1992. This illegal and unconstitutional administrative measure targeted people who (or whose parents) had been born in other republics of former Yugoslavia, which suggests that the erasure was based on ethnic origin (Dedić et al. Citation2003).Footnote3

In addition to the two political parties mentioned, our analysis includes speeches by the SMC, which was established just before the elections in 2014 by Miro Cerar, and the circle around him, without other visible candidates or a distinct party programme. Cerar’s party perceived itself as a party of ethical and responsible people who would break with the old and corrupted Slovenian political elite and ensure the well-being of Slovenian citizens (Fink-Hafner Citation2016, p. 1328). The party, which won the elections and was able to form the government, represents itself as a centrist and liberal political force and is a member of ALDE, the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats. Cerar himself does not appear, at first glance, to be an ethnonationalist populist like Orbán but rather a technocrat and legalist.

The SMC was the biggest coalition party in the time frame of our analysis and the most active party in the debates on migration. The second most active party was NSi, followed by The Left, a party established in 2017, after the dissolution of the United Left Coalition (Združena levica) established in 2014, which got 6% of the votes at the national parliamentary elections in the same year. Also active was DeSUS, the Democratic Party of Pensioners of Slovenia (Demokratična stranka upokojencev Slovenije), which is part of the European Democratic Party. The least active parties in the analysed debates were the Social Democrats (Socialni demokrati—SD), a member of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, and the Party of Alenka Bratušek (Stranka Alenke Bratušek—SAB), a member of ALDE. In the period between 2014 and 2018, covering the ‘refugee crisis’, the coalition consisted of SMC, DeSUS and SD.

In the context of the theoretical outlines described above, we expect differences amongst political parties to reveal that, at certain points, host ideology trumps populism; in other words, right–left differences remain hegemonic. In this way we expect to find support for the thin ideology thesis, showing at the same time how populism is performed by different parties. Additionally, we also pay attention to similarities across parties; whether, for example, the discourses of SDS, NSi and SMC converged and at what point and why this occurred. Similarities in party discourses demonstrate populism’s capacity to be appropriated and mobilised by any political position.

Methods and sample

To explore the populist framing of migration in Slovenian parliamentary debates, we adopted frame analysis, a discursive approach to the study of frames and populist antagonisms that are embedded in texts. Frame analysis enables us to detect how content is selected and classified and what aspects of a phenomenon are emphasised and how this is done (Entman Citation1993, p. 54). According to Verloo, a frame is an ‘organizing principle that transforms fragmentary or incidental information into a structured and meaningful problem, in which a solution is implicitly or explicitly included’ (Verloo Citation2005, p. 20). Thus, we have analysed texts by noting which problem (diagnosis) the speakers address and what is offered as a solution to the problem (prognosis). After the coding, we first classified the frames of the coders into sub-frames (a longer list of frames) and then further merged these into main frames (see and ), which we considered as the basis for the analysis.

TABLE 1 Overlap of Populist Antagonisms and Frames in Discourse of Political Parties—Diagnosis

TABLE 2 Overlap of Populist Antagonisms and Frames in Discourse of Political Parties: Prognosis

Approaching the analysis of discourse by devising problem–solution frames, the method of frame analysis differs from more linguistically oriented approaches to semantically analyse meanings of language specificities such as the use of metaphors, metonymy and intonation. In contrast, adopting frame analysis enables us to look at manifestations of ‘strategic framing’ of issues, which Carol Bacchi defines as the ‘conscious and intentional selection of language and concepts to influence political debate and decision-making’ (Bacchi Citation2009, p. 39).

As explained above, to empirically operationalise populism we measured three populist antagonisms. We define people-centrism as populist antagonism embedded in speech when special reference to ‘the people’ is made, namely, ‘the people’ is presented as a unifying whole, including references to the nation, country, ‘homeland’, ‘us’ and ‘our’, and the different ‘kinds of people’, that is, ‘the working people’, ‘taxpayers’ and so forth. As populist ‘othering’ we included any antagonism along the lines ‘we–them’, ‘in–out-group’: ‘we, the people’ against ‘them, the migrants’; migrants represent a threat to the homogeneity of ‘the people’ (Taggart Citation2017); out-groups (for example minorities) are framed as a burden to society and responsible for all the problems of ‘the people’ (Jagers & Walgrave Citation2007). We considered ‘anti-elitism’ to be a populist antagonism that builds on discrediting and blaming the elite and detaching them from ‘the people’. This includes, for example, perceiving elites as corrupt, harmful and not representing ‘the people’ (Ernst et al. Citation2019, p. 168). Anti-elitism includes in its antagonistic stance subcategories such as ‘establishment parties’, ‘EU bureaucrats’, ‘the state’ and the ‘asylum industry’, with reference to ‘globalists’, ‘corporations’, media and so forth. Anti-elitism is defined as ‘populist antagonism’ when it is related to ‘the people’. Not all critique of the elite/government was classified as anti-elitist populist antagonism, only that which centred on ‘the people’ in juxtaposition to the elite.

Our research material consisted of transcripts of the National Assembly’s sessions on seven migration-related bills passed between March 2015 and May 2019.Footnote4 The adopted bills were proposed in reaction to increased migration from the so-called Balkan migration route and included, inter alia, the Law on Foreigners, the Defence Act and the Act on the State Border.Footnote5 We selected bills that related directly to the refugee crisis and where one of the reasons for proposing it was the refugee crisis and/or it had a direct influence on the rights and treatment of refugees.

The transcripts of selected discussions amounted to 269 pages. The material was further reduced by taking into account the function and political affiliation of the speaker. For the coding we selected the speeches of the proposer of the bill, the party representativesFootnote6 and the speeches of the two MPs from each political party who have spoken first in the debate regarding the selected legislation. By applying these selection criteria, all the key parts of discussions and the entire political spectrum were included. Our sample includes 95 speeches by representatives of the seven political parties described above. The total amount of material analysed was 113 pages. In the speeches we identified 219 problem–solution pairs, which represent the unit of analysis. For the purpose of coding, we prepared a coding manual and an online tool for coding.Footnote7

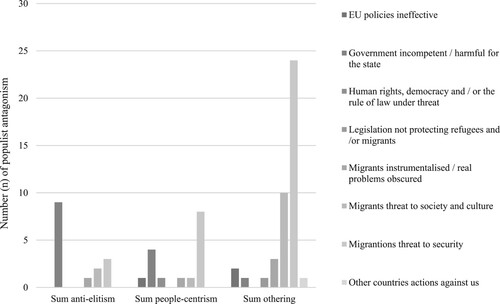

Intersection of populist antagonisms and frames on migration in diagnosis

When discursive frames are related to populism, they indicate different populist perspectives; we will therefore explore which frames are most frequently associated with the three populist antagonisms. When frames are associated with several antagonisms, the degree of populism is stronger. As antagonisms represent the essential feature of populism, our aim is also to analyse who is perceived to be part of ‘the people’, elites or others, and why, along with the differences between the political parties in their use of populist speech.

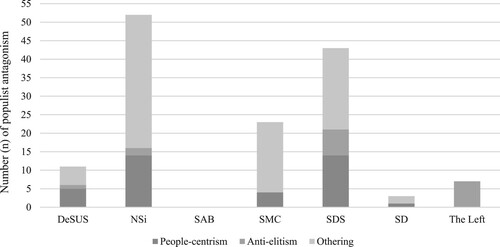

Populist othering: migrants as a security and cultural threat

‘Othering’ was the most prevalent antagonism in parliamentary debates on migration-related bills in Slovenia, and we detected it in 60% (n = 84) of all populist antagonisms in diagnosis and prognosis (n = 139) (see and ). On the level of diagnosis (problem definition), the most salient overlap was between the antagonism ‘othering’ and the frame ‘migration as a threat to security’ (see ). This frame is present in over half of cases in which othering was detected (57%, n = 24 of 42).

Figure 1. Intersection of Populist Antagonisms and Frames: Diagnosis

Note: The frames ‘landowners harmed by border fence’, ‘police and army overburdened’ and ‘shortage of specialised labour’ do not overlap with populist antagonism(s).

Amongst the political parties that showed this overlap most often were NSi (50%, n = 12), SMC (25%, n = 6) and SDS (21%, n = 5) (see ). One of the reasons the SMC, which presents itself as a centrist and liberal political party, deployed populist securitisation discourse was to pass migration-related bills. These bills were in six out of seven cases proposed by the government, which includes SMC as the biggest coalition party. The SMC’s warnings about migration as a security issue led to public concern and assisted the passing of these bills, which restricted the rights of asylum seekers on Slovenian soil, increased police numbers to deal with migration and approved military assistance to police on the border.Footnote8

As for the NSi and SDS, several studies have highlighted their discriminatory discourse and politics against minorities (Frank & Šori Citation2015; Šori Citation2015; Pajnik et al. Citation2016; Pajnik Citation2019). Our analysis confirms these findings, as the results show the highest level of exclusionary populism by these two parties (see ).Footnote9 One example of the intersection between the frame ‘migration as a threat to security’ and the antagonism ‘othering’ was in the speech of an NSi representative, MP Jožef Horvat, who emphasised that migrants and refugees were a big security risk for the local population.Footnote10 Anja Bah Žibert, a representative of the SDS parliamentary group, made similar claims that migrants could endanger peace in Europe and European values.Footnote11

The rhetoric of fear was also evident in the discourse of SMC. The Prime Minister, Miro Cerar, in this case speaking as the representative of the proposer of the bill (the government) and who won the elections based on his ‘trademark’ ethics and morality, emphasised that the influx of migrants to Slovenia was endangering public safety, peace and private property.

In all these cases, ‘the people’ (the local population, European people in general, Slovenian people in particular) were constructed as a homogeneous in-group by separating them from the out-group (migrants and refugees), which was portrayed as threatening. Reinemann et al. (Citation2017, pp. 20–1) point out that migrants as an out-group were also perceived as homogenous.

‘Migrants as a threat to society and culture’ was the second most prominent frame seen in combination with the populist antagonism ‘othering’ (see ) and was present in almost half of the othering cases (42%, n = 10 of 24). We noted their merging in the discourse of the right-wing parties SDS (50%, n = 5) and NSi (50%, n = 5) (see ). For example, Jernej Vrtovec, a representative of the NSi parliamentary group, claimed, ‘what we give to migrants, we have to take away from our citizens’.Footnote12 Similarly, Žan Mahnič, a representative of the SDS parliamentary group, stated:

We have 300,000 citizens below the poverty line. You can say this is populism, but I think it is a sad reality that we have many of our own people that we have to take care of and it is wrong to behave in a stepmotherly way towards our own citizens just to satisfy some international community.Footnote13

In both cases, migrants were viewed as endangering the economic well-being of Slovenian citizens. The examples point to welfare chauvinism, which is one of the crucial elements of the populist radical right agenda in general. Welfare chauvinism implies that people designated as belonging to the majority national community are entitled to a fairly generous welfare state, whereas foreigners are to be excluded from it (Mudde & Kaltwasser Citation2012, p. 160).

We also detected the populist antagonism ‘othering’ and the presentation of migrants as a threat to Slovenian society and culture in a speech by NSi MP Jožef Horvat, who said accepting migrants would lead to ‘leaving the homeland and continent to another civilisation’, and who viewed welcoming migrants to Slovenia as ‘denying our Slovenian traditional values’.Footnote14 These arguments confirm the right-wing parties’ idea of Slovenia as a state of Slovenians, thereby excluding others on the basis of ethnicity. Horvat also asserted that due to migration ‘in half a century, our granddaughters will have to cover their faces with veils’. This quote highlights the danger of sexist practices and gender relations being imported to Slovenia if Muslims are admitted (Farris Citation2017, p. 74). Research on the discourse of some right-wing populist parties and movements frequently finds their instrumentalisation of gender for portraying certain social groups as ‘others’ (Mayer et al. Citation2014, p. 263; Farris Citation2017).

Populist people-centrism: our citizens are endangered

Our analysis showed a substantial connection between the frame ‘migration as a threat to security’ and the populist antagonism ‘people-centrism’ (see ). This intersection is present in half of the cases in which this antagonism was identified (n = 8 of 16). One reason for identifying ‘migration as a threat to security’ as a ‘populist frame’Footnote15 relates to the link between the framing of migration as a security threat and the expanded identification with Slovenian citizens, who are viewed as endangered because of migration. The selected frame was clearly combined with two antagonisms, people-centrism and othering, which additionally confirms its populist dimensions. The party whose discourse showed the largest overlap between the mentioned frame and people-centrism is SDS (50%, n = 4), followed by NSi (37.5%, n = 3) and the centrist-liberal party DeSUS (12.5%, n = 1) (see ).

The selected cases below explicitly refer to ‘the people’, who are perceived as a monolithic group with no internal differences (Jagers & Walgrave Citation2007, p. 322). Results indicate that the composition of ‘the people’ differs amongst political parties. NSi representative Horvat, for example, expressed concerns that because of migration, ‘the purpose and even existence of our EU are being called into question’.Footnote16 In this case the actors who are affected by migration are ‘our EU’ and ‘our citizens’, constructed as the in-group. Moreover, we can also detect the antagonism ‘othering’, as the in-group is perceived to be endangered by the out-group (migrants). The SDS MP Marijan Pojbič made similar comments and showed a nativist understanding of the state by praising the ‘homeland’, while commenting on the Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners:

I think the name Slovenia must be heard in this parliament today. The name Slovenia must be heard! To me, it is about Slovenia! To me, it is about the Slovenian people, the Slovenian nation and this splendid, magnificent homeland of Slovenia, whose independence we have gained … . To me, it is about this. Citizens of the Republic of Slovenia voted for me as a member of parliament in order to work in their interest. And ensuring security in this country is certainly one of the primary tasks of every member of this parliament. Not even one MP sitting here has the right to sit in the Slovenian Parliament and work against the interests of the Slovenian people. Today, we are adopting a law that seeks to protect the Slovenian people.Footnote17

Anti-elitism: the government is not caring for ‘the people’

Anti-elitist discourse is based on the notion of alienation and distance between the elites and ‘the people’. Populists claim they are on the side of ‘the people’. They blame all problems on the political incompetence of the elites, who act in their own interests and neglect those of ‘the people’. (Jagers & Walgrave Citation2007, p. 324).

The results of our analysis show that members of parliament mostly blame the political elites for the country’s ills, opposition politicians target in particular the government and the coalition. The frame most frequently linked to anti-elitism is ‘government incompetent/harmful for the state’ (see ). This link is present in 60% of cases where this antagonism was detected (n = 9 of 15). This populist frame is based on criticism of the government, whose actions are harmful for ‘the people’, and therefore intersects with anti-elitism. The party that stressed this kind of discourse the most is The Left (56%, n = 5), followed by the SDS (44%, n = 4) (see ). In the speech on the International Protection Act that covers the right of refugees to asylum, SDS MP Anja Bah Žibert accuses the government of failing to act in the interests of its citizens, shows her closeness to ‘the people’ as she wants to portray herself as knowing what ‘the people’ want and caring about their concerns:

While other European countries due to the worsening situation have been adopting renewed or additional legal restrictions after the initial legislative changes, our government throughout this time has failed to prepare a bill on international protection that would justify the trust of citizens and allay their concerns.Footnote19

The government and the coalition, which have a duty to care for the well-being of citizens, are doing something completely different. They intimidate, warn against an external enemy and … create the impression that a state of emergency prevails in Slovenia. It has to be clearly said to the people that it is not the refugees who are threatening their future, it is not the refugees who are threatening their jobs, nor are they to blame for a far too high level of poverty. It is mainly the government’s fault. … The government allows the exploitation of workers, non-payment of pension contributions and a minimum wage that does not guarantee a decent life. The government is to blame … for the deepening of poverty and social exclusion. … If the public is convinced that the absent refugees are to blame for the situation, it will be easier for the government to continue to care only for the welfare of the elites and the lobbies they represent. In the United Left, we condemn this kind of culture of fear, which is used by the government, the coalition and, unfortunately, most of the rest of the opposition.Footnote20

You, the government, the coalition, the political right, have been intimidating people … you still support military conflict, the impoverishment of countries in the Middle East. You are sending military units abroad and helping to start new wars. You are closing borders, denying help and protection to … the victims of these wars that you support. … Why, after you rejected the proposal to raise the minimum wage, do you claim today that the Aliens Act primarily protects the rights of Slovenian citizens? It is completely clear that these are manipulations and outright lies. And refugees are not to blame for the increase of poverty in Slovenia … . All this is the fault of this and all previous governments, which … use the policy of intimidation, to introduce austerity measures that have deepened the social hardships of people.Footnote21

The government … also want to limit the rights of persons with international protection, for example, to maximally limit the possibility of family reunification … you also want to abolish the possibility of obtaining a temporary residence permit for all foreign pupils and students … the budget for 2018 cuts the largest amount, 40 million euros, from social and security benefits … the government and coalition proposals … reduce the rights of refugees, ease [legal] procedures for employers who benefit at the expense of violating the rights of foreign workers … . This Law on Foreigners deepens the plight of foreign workers and refugees, we will not support it … what you want now for foreigners will soon become applicable to most of us. And even today, with your policies, many citizens in Slovenia feel like foreigners.Footnote22

The antagonism ‘anti-elitism’ is most clearly exhibited in the discourse of The Left on the level of diagnosis and prognosis, while all three antagonisms on both levels can be detected in the discourse of the right-wing party SDS (see ).

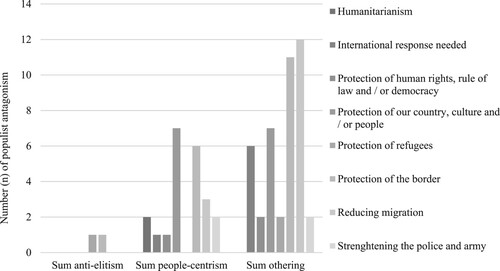

Intersection of populist antagonisms and frames on migration in prognosis

Populist advocacy of protectionist measures

On the level of prognosis, which is centred on what members of parliament perceive as a solution regarding the issue of migration, the populist antagonisms ‘othering’ and ‘people-centrism’ are linked to multiple frames compared to anti-elitism, which is connected solely to two frames: ‘protection of the border’ and ‘protection of refugees’. Our analysis indicates the most notable connection between the populist antagonism ‘othering’ and the frame ‘reducing migration’ (see ), which is present in more than a quarter of cases in which this antagonism was coded (29%, n = 12 of 42).

Figure 3. Intersection of Populist Antagonisms and Frames: Prognosis

Note: The frames ‘compensation for landowners’ and ‘social reforms’ do not overlap with populist antagonism(s).

Because this frame presents an opposition between ‘the people’ (Slovenia, Slovenian citizens) and ‘others’ (migrants), we labelled it ‘populist’. This intersection appeared most often in the discourse of NSi (67%, n = 8), followed by SDS (25%, n = 3) and SMC (8%, n = 1) (see ).

For example, NSi representative Jernej Vrtovec urged adopting restrictions on Slovenia’s obligations to refugees under international law:

Its content should be a reflection of all the facts regarding the migrant crisis and all the consequences of large numbers of migrants for our country. On the one hand, in adopting this legislation we should mostly have in mind the economic aspect, the capacities of the Republic of Slovenia, and on the other hand, the security issue.Footnote23

Populism advancing ethnonationalism

Protecting the border is closely linked to protecting the country and its culture and people. Our analysis shows a strong connection between the frame ‘protection of our country, culture and/or people’ and the populist antagonism ‘people-centrism’ (see ). This was the case in almost one third of examples in which this antagonism was detected (32%, n = 7 of 22), which leads us to identify this frame as populist. The party whose discourse showed the intersection between the identified frame and antagonism the most was NSi (42.9%, n = 3), followed by SDS (28.5%, n = 2), while it appeared in one speech each of the liberal parties SD (n = 1, 14.3%) and SMC (n = 1, 14.3%) (see ). For example, Jernej Vrtovec (NSi) highlighted the welfare of Slovenian citizens as the fundamental objective: ‘The obligation of every country is to take care of its own citizens first’.Footnote26 According to Mudde and Kaltwasser (Citation2012, pp. 160–61), such proposals follow the principle of ‘national preference’, which is based on the idea that ‘our own people’ should be given priority in welfare, employment and accommodation.

The exclusion of migrants was also present in the speech of an SMC MP, Marko Ferluga, who asserted that ‘our country’ has the legitimate right to act according to the Draft Act amending the Act on Control of the State Border and ensure the safety of Slovenian citizens and Slovenia.Footnote27 Ferluga invoked Slovenia and its people as the legitimate political sovereign (Aslanidis Citation2018) and emphasises the safety of Slovenian people as the ultimate aim. This case shows an attempt to demonstrate his priority of caring for and defending Slovenian citizens (Jagers & Walgrave Citation2007). Populist perspectives thus identify society’s real or perceived issues and populist actors present themselves as the only ones with the ability and will to solve them (Mikucka-Wójtowicz Citation2019, p. 475).

The populist frame ‘protection of the border’ was also combined with the populist antagonism ‘people-centrism’ (see ), which occurred in more than one quarter of cases in which this antagonism was coded (27%, n = 6 of 22). Amongst the parties that expressed this kind of discourse were NSi (66.6%, n = 4), DeSUS (16.7%, n = 1) and SMC (16.7%, n = 1) (see ). The NSi MP Jožef Horvat stressed the importance of the state border for the sovereignty of ‘our country’ in times of increased migration.Footnote28 Jernej Vrtovec (NSi) similarly claimed, ‘the Draft Act amending the Act on Control of the State Border together with the Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners … represent the first step to protection of our sovereignty’.Footnote29 DeSUS MP Uroš Prikl also emphasised the sovereignty of the state, which in his opinion included also ensuring control over its state borders; ensuring the security and rights of Slovenian citizens and ensuring that the ‘migration crisis’ did not have any negative effects on the security and economic well-being of Slovenians.Footnote30 As seen from these examples, the goal of populist communication is to appeal to ‘the people’, with a focus on their sovereignty and the popular will (Jagers & Walgrave Citation2007, p. 323).

The actors who in a populist perspective are often blamed for ignoring the will of ‘the people’ are the elites, particularly the political elite. On the level of prognosis, the populist antagonism anti-elitism connects solely with two frames, ‘protection of the border’ and ‘protection of refugees’ (see ). The first frame, apart from overlapping with the antagonisms ‘people-centrism’ and ‘othering’, was also linked to ‘anti-elitism’, although with regards to the latter antagonism, the overlap was seen in only one case. This frame follows the argument that Slovenia has to protect its borders from migrants in order to ensure the sovereignty of its borders, ‘the people’ and state, while the political elite must respect the will of ‘the people’.

Conclusion

In this article we have acknowledged populism as a central phenomenon of illiberal democracy, conceptualising it at the crossroads of ideology (Mudde Citation2004) and political discourse (Laclau Citation2005). This has enabled us to identify shifts across the political spectrum, also emphasising the differences between the leftist and rightist manifestations of populism. We used frame analysis to analyse populism in parliamentary speeches on migration-related bills in Slovenia and measured three populist antagonisms: people-centrism, anti-elitism and othering.

As emphasised by Taggart (Citation2004), migration is one of the most contested topics in contemporary political debates at the European level as well as globally and has mobilised distinct populist antagonisms in the Central and Eastern European context. Our results show that the discourse on migration-related bills in Slovenian parliamentary debates in the period 2015–2019 was populist in about one-third of the analysed cases, pointing to the prevalence of exclusionary, ethnonationalistic populist frames that treat migrants as ‘others’ who need to be kept separate from ‘us’, ‘the people’. The results confirm Brubaker’s (Citation2017) thesis of a strong presence of an ethnonationalist populism cluster in the Central and Eastern European region.

The degree of populism was considered higher when a discursive frame overlapped with more than one populist antagonism. For example, we showed that the frame ‘migration as a threat to security’ overlaps with the antagonisms ‘othering’ and ‘people-centrism’ and that the frame ‘government incompetent/harmful to the state’ also connects with two antagonisms, ‘people-centrism’ and ‘anti-elitism’. We found that the frame ‘protection of the border’ can be considered a full populist frame because it merges with all three populist antagonisms. The prevalence of exclusionary populist frames was noticed both on the level of diagnosis and prognosis; in diagnosis they included ‘migration as a threat to security’ and ‘migrants as a threat to society and culture’ and in prognosis they encompassed ‘protection of the border’, ‘reducing migration’ and ‘protection of our country, culture and/or people’. The results did not indicate any prevalent inclusionary populist frame: while we found some cases that showed an inclusionary perspective (such as ‘protection of refugees’ and ‘protection of human rights, rule of law and/or democracy’), these had weak correlation with populist antagonism(s). Thus, exclusionary discourse on migration is much more likely to be populist compared to a discourse that is more inclusive towards migrants.

As for the distribution of populist antagonisms amongst political parties, the results indicate the highest level of populist discourse by the traditionally right-wing parties NSi (37%, n = 52 of 139) and SDS (31%, n = 43) and the (then governing) centrist-liberal SMC (17%, n = 23). Populism is present to a lesser extent in the discourse of parties associated more with the centre, such as DeSUS (8%, n = 11), while the lowest share of populism was detected in the discourse of SD (2%, n = 3) and The Left (5%, n = 7).

We have shown in this article that distinct features of populist communication on migration range from exclusionary, ethnonationalistic to inclusionary, solidary discourse that fit the ideological views of various political actors. Our analyses indicated that the ideological perspectives of political parties are reflected in the degree of populist speech, whereby party political affiliation relates to different kinds of populism. Right-wing parties expressed much higher degrees of populism (more populist antagonisms and ‘populist frames’ detected) compared to parties on the left, as well as exclusionary populism, directed against migrants.

The empirical illustrations show that the construction of ‘the people’ differs between left-wing and right-wing populism. The former, in our case, applied an inclusionary vision of ‘the people’ that included foreign workers and refugees, but this is not to say that left-wing populism in general does not take an exclusionary view, for example, of foreign workers. The prevalent feature in this case encompasses the idea of ‘the people’ as the working class in antagonistic relation with capitalists and their allies in the government. In addition, left-wing populism blames the government and coalition for supporting military conflicts, advancing elite interests and neglecting those of its citizens, especially workers.

By contrast, right-wing populism defines ‘the people’ as an ethnonational entity, focusing on a nativist understanding of ‘the homeland’ and Europe. An important component of right-wing populism revolves around ‘national preference’ that entitles ‘our own people’ to priority in welfare, employment and accommodation, and focuses on the protection of the state border to ensure the sovereignty of ‘our country’. Right-wing populism thus often builds on exclusionary perspectives directed against migrants, which are based on an antagonistic portrayal of the split between ‘the people’ (as Slovenian citizens, a local population and Europeans) and the out-group, migrants and refugees, who are constructed as belonging to ‘another civilisation’ and posing a threat to the security, culture and the economic well-being of ‘our people’. The results show that the persona (or, in this case, the group) non grata in right-wing populist communication includes migrants, while in left-wing populist communication this role is reserved for certain political and economic elites, reflecting the division between the people and the oligarchy.

Our foremost aim in this article was to contribute to the conceptualisation of populism, bridging the ideology–discourse divide, and analysing them in parallel, which is an approach that we hope will be further developed in future research. Our approach to identifying populism, distinguishing between its left and right manifestations, is not specific to the Slovenian context but can be applied to other contexts internationally. Moreover, we hope to further develop the concept of ‘populist framing’ for use in future empirical analysis of populism in the national and international context.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mojca Pajnik

Mojca Pajnik, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Kardeljeva ploščad 5, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; Peace Institute, Metelkova 6, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia. Email: [email protected]

Emanuela Fabijan

Emanuela Fabijan, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Aškerčeva 2, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Kardeljeva ploščad 5, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 The countries along the Balkan route—Slovenia, North Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia—were mostly transit countries for migrants; nevertheless, all four countries adopted a security-driven approach to migration (Šabić Citation2017, p. 68). This was evident also in the stationing of heavily armed officers with police dogs and military equipment on the borders in Slovenia and Croatia (Applegate Citation2016, p. 73).

2 Janša’s SDS was the party in power in the periods 2004–2008 and 2012–2013 and has been the major party in opposition since 2013. In February 2020, Janša formed his third ruling coalition. The SDS finished first in the 2018 parliamentary elections, obtaining one-quarter of the votes, but was unable to gather the support needed for a governing coalition, as most parliamentary parties refused to join a coalition with the SDS. The position of prime minister was eventually occupied by Marjan Šarec—leader of the second largest parliamentary party, the newly emerged List of Marjan Šarec (Lista Marjana Šarca)—who formed a minority government. This government lost power after two years and Janša was able to form a new coalition with New Slovenia (NSi), the Democratic Party of Pensioners (DeSUS) and the Modern Centre Party (SMC).

3 Slovenia saw increased immigration from the late 1990s onwards; migration to Slovenia had already begun in the 1950s from other parts of the Yugoslav federation. Intra-state mobility in the Yugoslav period was a strong trend due to industrialisation and urbanisation that made Slovenia a popular destination for people looking for jobs, particularly from the south-eastern regions of Bosnia & Hercegovina, Serbia and Kosovo. This trend significantly affected the current composition of Slovenia’s foreign population, since the majority came—and continue to come—from Yugoslavia’s successor states. Geographical, cultural and linguistic proximity remain decisive factors for other former Yugoslavs, once co-nationals and now ‘third-country nationals’, to continue migrating to Slovenia into the 2000s. Additionally, there was a notable increase in migrants from post-Soviet countries, Africa, Asia and Latin America, and with the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ from the Middle East. Regardless of migrants’ state of origin, Slovenia’s migration regime was securitised in the name of a nationalist ideology that viewed ‘the other’ as a threat to ‘the people’ (Pajnik Citation2016).

4 First, we carried out a test screening of the potential material for the analysis and gathered all discussions which include references to migration in sessions from the year 2015. For this purpose we searched for lexical roots migr* (migration/migrant) and beg* (refugee/refugee crisis) in the transcripts of all sessions from that year.

5 The analysed bills include the following: Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners (passed in March 2015), proposed by four members of parliament, first signatory Peter Vilfan, member of ZaAB—Alliance of Alenka Bratušek; Draft Act amending the Defense Act (passed in October 2015); Draft Act amending the Act on the Organization and Work of the Police (passed in November 2015); Draft International Protection Act (passed in March 2016); Draft Act amending the Act on Control of the State Border (passed in January 2017); Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners (passed in January 2017); and Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners (passed in October 2017). Apart from the first bill, all the others were proposed by the government. Three out of seven selected bills were adopted by an urgent procedure, one by a shortened procedure and three by regular procedure. Some of the aims of the mentioned bills included, for example, military assistance to the police in light of the refugee crisis in order to protect the Slovenian border; increasing the number of police staff and including reserve police to better meet the security challenges of the refugee crisis and making asylum legislation more restrictive.

6 Each parliamentary party has a deputy group in the National Assembly.

7 The coding was carried out by three coders, who synchronised the coding based on several tests, followed by joint group meetings, where they discussed and resolved dilemmas.

8 See also Žagar et al. (Citation2018).

9 Previous research has shown that SDS led the securitisation discourse in Slovenia, based on selective information, simplification and exaggeration; for example, reports regarding terrorists infiltrating migrant groups (Malešič Citation2017, p. 965). In general, the right-wing parties, and SDS in particular, saw the ‘refugee crisis’ as an opportunity for strengthening their position (González Villa Citation2017, p. 353). For example, in the 2018 elections SDS gained almost 20% more votes compared to the 2014 elections. For more on election results see State Election Commission, available at: https://elections.gov.si/, accessed 28 June 2021.

10 Member of Parliament Jožef Horvat. Speech from the discussion on the Draft International Protection Act (1 March 2016) (Predlog zakona o mednarodni zaščiti, 1 March 2016), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=5B12D69C435F30C3C1257FB00029CDD9, accessed 2 November 2022.

11 Representative of SDS’s parliamentary group Anja Bah Žibert. Speech from the discussion on the Draft International Protection Act (1 March 2016) (Predlog zakona o mednarodni zaščiti, 1 March 2016), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=5B12D69C435F30C3C1257FB00029CDD9, accessed 2 November 2022.

12 Representative of NSi’s parliamentary group Jernej Vrtovec. Speech from the discussion on the Draft International Protection Act (1 March 2016) (Predlog zakona o mednarodni zaščiti, 1 March 2016), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=5B12D69C435F30C3C1257FB00029CDD9, accessed 2 November 2022.

13 Representative of SDS’s parliamentary group Žan Mahnič. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners (17 October 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o tujcih, 17. oktober 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=CC28B28727D33CDBC12582430039AB72, accessed 2 November 2022.

14 Member of parliament Jožef Horvat. Speech from the discussion on the Draft International Protection Act (1 March 2016) (Predlog zakona o mednarodni zaščiti, 1 March 2016), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=5B12D69C435F30C3C1257FB00029CDD9, accessed 2 November 2022.

15 We identified a frame as ‘populist’ when a certain frame is present in at least one-quarter of cases when a populist antagonism was coded.

16 Member of Parliament Jožef Horvat. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Act on Control of the State Border (23 January 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o nadzoru državne meje, 23 January 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=E22692C76021397AC125817600475343, accessed 2 November 2022.

17 Member of Parliament Marijan Pojbič. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners (26 January 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembi in dopolnitvah Zakona o tujcih, 23 January 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=B687B9028372D4D9C125818E003B790D, accessed 2 November 2022.

18 Member of Parliament Vinko Gorenak. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners (26 January 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembi in dopolnitvah Zakona o tujcih, 26 January 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=B687B9028372D4D9C125818E003B790D, accessed 2 November 2022.

19 Representative of SDS’s parliamentary group Anja Bah Žibert. Speech from the discussion on the Draft International Protection Act (1 March 2016) (Predlog zakona o mednarodni zaščiti, 1 March 2016), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=5B12D69C435F30C3C1257FB00029CDD9, accessed 2 November 2022.

20 Member of Parliament Franc Trček. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Act on Control of the State Border (23 January 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o nadzoru državne meje, 23 January 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=E22692C76021397AC125817600475343, accessed 2 November 2022.

21 Member of Parliament Matej T. Vatovec. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners (26 January 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembi in dopolnitvah Zakona o tujcih, 26 January 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=B687B9028372D4D9C125818E003B790D, accessed 2 November 2022.

22 Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Law on Foreigners (17 October 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o tujcih, 17 October 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=CC28B28727D33CDBC12582430039AB72, accessed 2 November 2022.

23 Speech from the discussion on the Draft International Protection Act (1 March 2016) (Predlog zakona o mednarodni zaščiti, 1 March 2016), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=5B12D69C435F30C3C1257FB00029CDD9, accessed 2 November 2022.

24 Representative of DeSUS’s parliamentary group Franc Jurša. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Defense Act (20 October 2015) (Predlog zakona o dopolnitvi Zakona o obrambi, 20 October 2015), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=0EE67BB8C0A32470C1257F7300488927, accessed 3 November 2022.

25 Member of Parliament Marko Ferluga. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Act on Control of the State Border (23 January 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o nadzoru državne meje, 23 January 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=E22692C76021397AC125817600475343, accessed 2 November 2022.

26 Representative of a parliamentary group Jernej Vrtovec. Speech from the discussion on the Draft International Protection Act (1 March 2016) (Predlog zakona o mednarodni zaščiti, 1 March 2016), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=5B12D69C435F30C3C1257FB00029CDD9, accessed 3 November 2022.

27 Member of Parliament Marko Ferluga. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Act on Control of the State Border (23 January 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o nadzoru državne meje, 23 January 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=E22692C76021397AC125817600475343, accessed 3 November 2022.

28 Member of Parliament Jožef Horvat. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Act on Control of the State Border (23 January 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o nadzoru državne meje, 23 January 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=E22692C76021397AC125817600475343, accessed 3 November 2022.

29 Representative of NSi’s parliamentary group Jernej Vrtovec. Speech from the discussion on the Draft Act amending the Act on Control of the State Border (23 January 2017) (Predlog zakona o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o nadzoru državne meje, 23 January 2017), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=E22692C76021397AC125817600475343, accessed 3 November 2022.

30 Member of Parliament Uroš Prikl. Speech from the discussion on the Draft International Protection Act (1 March 2016) (Predlog zakona o mednarodni zaščiti, 1 March 2016), available at: https://www.dz-rs.si/wps/portal/Home/seje/evidenca/!ut/p/z1/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zivSy9Hb283Q0N3E3dLQwCQ7z9g7w8nAwsPE31w9EUGAWZGgS6GDn5BhsYGwQHG-lHEaPfAAdwNCBOPx4FUfiNL8gNDQ11VFQEAF8pdGQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/?mandat=VII&type=sz&uid=5B12D69C435F30C3C1257FB00029CDD9, accessed 2 November 2022.

References

- Applegate, T. M. (2016) ‘Slovenia: Post-Socialist and Neoliberal Landscapes in Response to the European Refugee Crisis’, Human Geography, 9, 2.

- Aslanidis, P. (2017) ‘Avoiding Bias in the Study of Populism’, Chinese Political Science Review, 2, 3.

- Aslanidis, P. (2018) ‘Measuring Populist Discourse with Semantic Text Analysis: An Application on Grassroots Populist Mobilization’, Quality & Quantity, 52, 3.

- Bacchi, L. C. (2009) ‘The Issue of Intentionality in Frame Theory: The Need for Reflexive Framing’, in Lombardo, E., Meier, P. & Verloo, M. (eds) The Discursive Politics of Gender Equality: Stretching, Bending and Policy-Making (New York, NY, & London, Routledge).

- Bobba, G., Cremonesi, C., Mancosu, M. & Seddone, A. (2018) ‘Populism and the Gender Gap: Comparing Digital Engagement with Populist and Non-Populist Facebook Pages in France, Italy, and Spain’, International Journal of Press/Politics, 23, 4.

- Brubaker, R. (2017) ‘Between Nationalism and Civilizationism: The European Populist Moment in Comparative Perspective’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40, 8.

- Canovan, M. (2002) ‘Taking Politics to the People: Populism as the Ideology of Democracy’, in Mény, Y. & Surel, Y. (eds) Democracies and the Populist Challenge (New York, NY, Palgrave).

- De Cleen, B. & Stavrakakis, Y. (2017) ‘Distinctions and Articulations: A Discourse Theoretical Framework for the Study of Populism and Nationalism’, Javnost–The Public, 24, 4.

- Dedić, J., Jalušič, V. & Zorn, J. (2003) Erased: Organized Innocence and the Politics of Exclusion (Ljubljana, Mirovni inštitut).

- Deiwiks, C. (2009) ‘Populism’, Living Reviews in Democracy, 1.

- Entman, R. M. (1993) ‘Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm’, Journal of Communication, 43, 4.

- Ernst, N., Blassnig, S., Engesser, S., Büchel, F. & Esser, F. (2019) ‘Populists Prefer Social Media Over Talk Shows: An Analysis of Populist Messages and Stylistic Elements Across Six Countries’, Social Media + Society, 5, 1.

- Farris, R. S. (2017) In the Name of Women’s Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism (Durham, NC, Duke University Press).

- Fink-Hafner, D. (2016) ‘A Typology of Populisms and Changing Forms of Society: The Case of Slovenia’, Europe-Asia Studies, 68, 8.

- Frank, A. & Šori, I. (2015) ‘Normalizacija rasizma z jezikom demokracije: primer Slovenske demokratske stranke’, Časopis za kritiko znanosti, 43, 260.

- Freeden, M. (2002) ‘Is Nationalism a Distinct Ideology?’, Political Studies, 46, 4.

- Gerbaudo, P. (2018) ‘Social Media and Populism: An Elective Affinity?’, Media, Culture and Society, 40, 5.

- González Villa, C. (2017) ‘Passive Revolution in Contemporary Slovenia. From the 2012 Protests to the Migrant Crisis’, Tiempo devorado, 4, 2.

- Jagers, J. & Walgrave, S. (2007) ‘Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium’, European Journal of Political Research, 46, 3.

- Kogovšek Šalamon, N. (2019) ‘Asylum in Slovenia: A Contested Concept’, in Stoyanova, V. & Karageorgiou, E. (eds) The New Asylum and Transit Countries in Europe During and in the Aftermath of the 2015/2016 Crisis (Leiden & Boston, MA, Brill Nijhoff).

- Laclau, E. (2005) On Populist Reason (London, Verso).

- Mair, P. (2013) Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy (London, Verso).

- Malešič, M. (2017) ‘The Securitisation of Migrations in Europe: The Case of Slovenia’, Teorija in praksa, 54, 6.

- March, L. (2017) ‘Left and Right Populism Compared: The British Case’, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 9, 2.

- Mayer, S., Ajanovic, E. & Sauer, B. (2014) ‘Intersections and Inconsistencies: Framing Gender in Right-Wing Populist Discourses in Austria’, Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 22, 4.

- Mikucka-Wójtowicz, D. (2019) ‘The Chameleon Nature of Populist Parties. How Recurring Populism is Luring “The People” of Serbia and Croatia’, Europe-Asia Studies, 71, 3.

- Moffitt, B. & Tormey, S. (2014) ‘Rethinking Populism: Politics, Mediatisation and Political Style’, Political Studies, 62, 2.

- Mouffe, C. (2018) In Defence of Left Populism (London & New York, NY, Verso).

- Mudde, C. (2004) ‘The Populist Zeitgeist’, Government and Opposition, 39, 4.

- Mudde, C. (2007) Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Mudde, C. & Kaltwasser, R. C. (2012) ‘Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America’, Government and Opposition, 48, 2.

- Pajnik, M. (2016) ‘Nationalizing Citizenship: The Case of Unrecognized Ethnic Minorities in Slovenia’, in Ramet, S. & Valenta, M. (eds) Ethnic Minorities and Politics in Post-Socialist Southeastern Europe (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

- Pajnik, M. (2019) ‘Media Populism on the Example of Right-Wing Political Parties’ Communication in Slovenia’, Problems of Post-Communism, 66, 1.

- Pajnik, M. & Sauer, B. (2018) ‘Populism and the Web: An Introduction to the Book’, in Pajnik, M. & Sauer, B. (eds) Populism and the Web: Communicative Practices of Parties and Movements in Europe (Abingdon & New York, NY, Routledge).

- Pajnik, M., Kuhar, R. & Šori, I. (2016) ‘Populism in the Slovenian Context: Between Ethno-Nationalism and Retraditionalisation’, in Lazaridis, G., Campani, G. & Benveniste, A. (eds) The Rise of the Far Right in Europe: Populist Shifts and ‘Othering’ (New York, NY, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Pelinka, A. (2013) ‘Right-Wing Populism: Concept and Typology’, in Wodak, R., Khosravinik, M. & Mral, B. (eds) Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse (London, Bloomsbury Academic).

- Ramet, S. P. (1999) The Radical Right in Central and Eastern Europe Since 1989 (University Park, PA, Pennsylvania State University Press).

- Reinemann, C., Aalberg, T., Esser, F. & de Vreese, C. (2017) ‘Populist Political Communication: Toward a Model of its Causes, Forms and Effects’, in Aalberg, T., Esser, F., Reinemann, C., Stromback, J. & De Vreese, C. (eds) Populist Political Communication in Europe (New York, NY, Routledge).

- Rizman, R. (1999) ‘Radical Right Politics in Slovenia’, in Ramet, P. S. (ed.) The Radical Right in Central and Eastern Europe Since 1989 (University Park, PA, Pennsylvania State University Press).

- Rizman, R. (2008) ‘“Onkraj demokracije” kot demobilizacija (depolitizacija) družbe in izziv populizma’, in Drčar-Murko, M., Flajšman, B., Vezjak, B. & Štrajn, D. (eds) Pet minut demokracije: podoba Slovenije po letu 2004 (Ljubljana, Liberalna akademija).

- Rooduijn, M. & Pauwels, T. (2011) ‘Measuring Populism, Comparing Two Methods of Content Analysis’, West European Politics, 34, 6.

- Šabić, SŠ (2017) ‘The Impact of the Refugee Crisis in the Balkans: A Drift Towards Security’, Journal of Regional Security, 12, 1.

- Šori, I. (2015) ‘Za narodov blagor: skrajno desni populizem v diskurzu stranke Nova Slovenija’, Časopis za kritiko znanosti, 43, 260.

- Stanley, B. (2008) ‘The Thin Ideology of Populism’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 13, 1.

- Suiter, J., Greene, D. & Siapera, E. (2018) ‘Hybrid Media and Populist Currents in Ireland’s 2016 General Election’, European Journal of Communication, 33, 4.

- Taggart, P. (2004) ‘Populism and Representative Politics in Contemporary Europe’, Journal of Political Ideologies, 9, 3.

- Taggart, P. (2017) ‘Populism in Western Europe’, in Kaltwasser, C. R., Taggart, P., Espejo, P. O. & Ostiguy, P. (eds) The Oxford Handbook of Populism (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

- Verloo, M. (2005) ‘Mainstreaming Gender Equality in Europe: A Critical Frame Analysis’, Greek Review of Social Research, 117.

- Žagar, I., Kogovšek Šalamon, N. & Lukšič Hacin, M. (2018). The Disaster of European Refugee Policy: Perspectives from the ‘Balkan Route’ (Newcastle, Cambridge Scholars Publishing).

- Zakaria, F. (2007) The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad (New York, NY, W.W. Norton).

- Zulianello, M., Albertini, A. & Ceccobelli, D. (2018) ‘A Populist Zeitgeist? The Communication Strategies of Western and Latin American Political Leaders on Facebook’, International Journal of Press/Politics, 23, 4.