ABSTRACT

This article proposes that reactance theory can be used to better understand how tourists’ perceptions of climate change affect their travel decisions. Reactance theory explains how individuals value their perceived freedom to make choices, and why they react negatively to any threats to their freedom. We study the psychological consequences of threatening tourist's freedoms, using a range of projective techniques: directly, using photo-expression, and indirectly, through collage, photo-interviewing and scenarios. We find that reactance theory helps to explain the extent of travel to two destinations: Svalbard and Venice, providing a nuanced understanding of how travellers restore their freedom to travel through three incremental stages: denying the climate change threat, reducing tensions arising from travel and heightening demand particularly for the most visibly threatened destinations. The theory suggests a fourth stage, helplessness, reached when consumers dismiss the value of destinations once they can no longer be enjoyed, but for which we, as yet, have no data. Reactance theory questions the validity of awareness-raising campaigns as behavioural change vehicles, provides alternative explanations of why the most self-proclaimed, environmentally aware individuals travel frequently, and helps identify nuanced, socially acceptable forms of sustainability marketing, capable of reducing resistance to change.

理解旅游者对由于气候变化而失去旅游自由的威胁的感抗:一个鼓励微妙的行为改变的新的可选择的方法

该文章提出感抗理论可以被用来更好的理解旅游者对气候变化的看法如何改变他们的旅行决策。感抗理论解释了个体如何看重他们认为的自由来做决定,并且为什么他们对于他们自由的威胁如此负面地抵抗。我们研究威胁到旅游者自由的心理后果,使用一系列的投射技术:直接地,使用照片表达,和间接地,通过拼接,照片采访和场景分析。我们发现感抗理论帮助解释旅行到两个不同目的地的程度:斯瓦尔巴群岛和威尼斯,提供一个对旅游者如何通过三个递增阶段存储他们的自由来旅行的微妙理解。这三个阶段为:否认气候变化威胁,减少因旅行而引起的紧张,提高需求特别是对最受威胁的目的地。理论建议第四个阶段,无助,当消费者不再享受,他们将目的地的价值驳回。这种情况对我们来说,还没有数据。感抗理论对提高活动作为行为改变的方法的认知是否有效性提出疑问,提供了另外的解释,关于最经常自我宣布具有环保认知个人旅行的,和帮助对可持续性市场营销微妙地确认,社会接受形式的,有能力减少对抗改变。

Introduction

Further research on the psychology underpinning the behaviour that results in climate change is needed, because most environmental problems are rooted in human behaviour (Gifford, Citation2008; Schott, Reisinger, & Milfont, Citation2010). Planned behaviour theory, attribution theory and the value–belief–norm theory of environmentalism have recently been used to explain the justifications given by tourists to restore the misalignment of beliefs and behaviours seen in cognitive dissonance (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014). Based on these findings, it has been suggested there is potential to change behaviour by targeting certain beliefs and preventing the use of some personal coping strategies (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014), an approach that resonates with stimulus–response or reinforcement theories. Yet there is evidence of environmental knowledge and activism not affecting holiday behaviour (Hares, Dickinson, & Wilkes, Citation2010; Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014; Prillwitz & Barr, Citation2011; Reiser & Simmons, Citation2005), meaning there may be value in seeking alternative explanatory models relating to the impact of environmental awareness on consumer behaviour.

Reactance theory may allow us to do this, as it differs from cognitive dissonance in its emphasis on resistance to social influence. Since reactance is reactive, not proactive, it results from the withdrawal of a previously available behaviour choice. It suggests that as we escalate the pressure on consumers, through additional information about the deterioration of tourist destinations, their reaction may be to not accept the need to change their behaviour. They may actually attempt to ignore the threat, seek justifications for not changing their behaviour and potentially consume more of the resources now acutely known to be under threat, until these are depleted.

While reactance theory has not been used previously in hospitality and tourism studies (Tang, Citation2014), it could potentially help to explain why tourists travel to destinations under threat from climate change (Hindley & Font, Citation2014), and, by extension, to explain the continuation of other forms of tourism that damage tourist destinations. This paper explores the explanatory value of reactance theory in this field. It is structured as follows. First, we argue how reactance theory provides an alternative account of consumer behaviour by understanding the threat of not being able to travel. Then, we outline the use of projective techniques to test whether reactance theory can be used to explain consumer motivations to travel to two examples of “disappearing destinations”, namely Svalbard and Venice. Next, the results are presented and discussed; the study shows that, when interviewed, tourists reassert their freedom to travel through denial, reduction of tensions and an increase in demand. Finally, the conclusion expands the model of Miron and Brehm (Citation2006) to explain tourists’ responses to the threat of freedom to travel, in relation to the intensity of reactance and the difficulty of restoring freedom.

Reactance theory

Reactance theory explains that individuals value their perceived freedom to make choices, and react negatively to threats to that freedom. Scarcity, such as the threat of tourist destinations changing (e.g. Cuba as a result of political transition) or disappearing (e.g. the Maldives due to climate change) increases the value of any product or service. Thus, any reduction in the freedom of behaviour to satisfy one's needs generates motivational arousal to re-establish such freedom. Reactance theory considers that with diminishing availability, our freedom to choose the things that we can have also reduces proportionally; we react against the interference to our prior access and this manifests itself in an increased desire to want, or to possess, the item more than before (Brehm, Citation1966; Brehm & Brehm, Citation1981). In our case it is the threat of reduction of one's freedom to travel to a particular destination due to the effects of climate change that is considered. The magnitude of reactance depends on: (1) the importance of the behaviour to travellers; (2) the extent of the behaviours eliminated; and (3) the likelihood of the threat (Brehm, Citation1966).

Taking each in turn, first, importance will vary between tourists as it depends on the person's relation between the freedom and the unsatisfied need (the desire to travel to the destination), the person's competence to make choices (their understanding of the choices being made) and the cognitive overlap between the choices available to them (the availability of alternative choices that could satisfy their same need to travel). Travel entitlement is enshrined in the UNWTO Code of Ethics and is part of our Western culture; it also has symbolic meanings in terms of freedom and payback for work (Becken, Citation2007). Thus, resistance to accepting climate change is ideological, based on a perceived threat to a traditional way of life and human supremacy (Campbell & Kay, Citation2014). As a result, tourists underplay the significance of climate change and, even when acknowledged, believe that sustainable behaviour at home compensates them for the impacts of their holidays (Barr, Shaw, Coles, & Prillwitz, Citation2010; Miller, Rathouse, Scarles, Holmes, & Tribe, Citation2010; Weeden, Citation2011).

Second, the extent of the behaviour options eliminated determines the perception of threat. Individuals less aware of climate change will see the threat more narrowly than those with a greater awareness; they will believe this is just about seeing polar bears or the eventual but slow sinking of Venice or disappearance of some random island. In such cases, reactance from not being able, morally, to travel to long-desired destinations, due to the threat of their disappearance, would be low, because these places may have a high emotive value but a low instrumental value (Lemelin, Dawson, & Stewart, Citation2012). Yet freedom to travel and discover the unspoilt is partly constituted by the tourism industry discourse, which provides reassurance to consumers by normalising their intended behaviour (Caruana & Crane, Citation2011). Therefore, for those individuals who are more aware of the impacts of climate change (either to the planet or to their lifestyle), the threat by implication is much greater. This is because the disappearance of some destinations threatens not only further destinations, but also the whole concept of flight-dependent holidays. The disappearing destinations may infer that our entire lifestyle needs to change (Brehm & Brehm, Citation1981) and this may explain why self-proclaimed environmentalists feel highly motivated to justify their travel behaviours and restore their rights (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014).

Third, society in general does not perceive that the threat of climate change is likely to affect their hedonistic lifestyles. There is a general belief that if changes occur, these will affect other people and there is an assumption that increasing temperatures will be positive for northern European tourist destinations (Gössling, Scott, Hall, Ceron, & Dubois, Citation2012). If this were the case, climate change also suggests that the currently dominant group of international tourists (sun and beach lovers from Western Europe) would travel less far, or even stay in their home country, implying a fall of total, international tourist numbers. This may explain consumers’ beliefs that long-term changes in climate parameters or environments will not threaten the immediate future of tourist behaviour (Scott, Jones, & Konopek, Citation2008). Hoffarth and Hodson (Citation2016) show evidence that climate change denial is linked to conservative views supporting the current economic system and Western free market thinking. As impacts of climate change become more evident, and despite more information becoming available, there is an increasing polarisation of views between individualists who feel a threat to their rights and collectivists who consider the impacts on society overall (Campbell & Kay, 2014).

We find, however, that while individualists may be reacting more strongly towards sustainability messages, collectivist environmentalists are not acting on their self-declared values when it comes to travel. Qualitative studies show that sustainability and climate change are not considered when planning holidays; tourists dismiss their own contribution to the overall impact as well as the difference their personal choices could make (Hares, Dickinson, & Wilkes, Citation2010; Miller, Rathouse, Scarles, Holmes, & Tribe, Citation2010). Higham, Cohen, and Cavaliere (Citation2014) find that there is little sense of personal responsibility with regard to climate change responses and the entrenched nature of contemporary air travel practice results in a resistance to change. Gössling, Scott, and Hall (Citation2013) in their search for evidence of a consumer response to lessen the climate change impacts of travel, found that there has not been a response. The ethical decisions of tourists travelling to destinations threatened by climate change are self-serving, and raising awareness of climate change feeds this self-interest, rather than resulting in pro-environmental behaviour (Hindley & Font, Citation2014).

Freedom can be threatened by self-control arising from one's environmental identity (Caruana, Glozer, Crane, & McCabe, Citation2014). For example, a person can make some upfront, moral choices that should influence holiday consumption patterns, such as not wanting to damage the places visited. However, these are subsequently revised when in practice they are seen to limit one's ability to travel in the way intended. Hares, Dickinson, and Wilkes (Citation2010) found that climate change is not an attitudinal set from which tourism choices are made. Reactance theory explains why consumers deny engaging in pro-social behaviour when this has high personal costs (Tyler, Orwin, & Schurer, Citation1982). There is extensive evidence that environmentally aware tourists are unwilling to alter their behaviour and some of the most climatically aware are the most active travellers (Gössling, Scott, & Hall, Citation2013), perhaps because self-sacrifice (for the greater good) is seen as being of no value unless others follow the same course of action (Shaw & Thomas, Citation2006).

Reasserting freedom

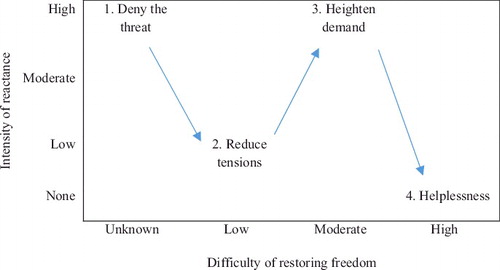

This article contributes to the literature on consumer behaviour impacting on climate change by outlining four stages commonly employed by consumers to reassert and restore their tourism freedoms. The stages indicate a progression in the behavioural responses of individuals, according to the level of pressure they are under, to acknowledge both climate change and their potential responsibility towards it. Increased awareness of the desirability of a behaviour, resulting from increased communication of the impact of climate change on tourist destinations and coupled with the threat of increased financial or social costs of travel, justifies the argument of stages. In the first stage, society dedicates a significant amount of effort to denying the threat of climate change. In the second stage, consumers reduce tensions to re-establish cognitive consonance. In the third, due to raised desire, there is increased demand and a consequent growth in consumption of travel to threatened destinations (Eijgelaar, Thaper, & Peeters, Citation2010; Lemelin et al., Citation2012; Lemelin, Dawson, Stewart, Maher, & Lueck, Citation2010). The fourth stage refers to the helplessness of society acknowledging that the previously acquired freedom is now lost. Each of the stages has been interpreted as a separate psychological barrier to acting on climate change (Gifford, Citation2011) but they have also been explained as consequences of reactance (Brehm, Citation1966) because they are explained in relation to the perceived increased threat of elimination to freely enjoy a desirable behaviour.

Taking the four stages in turn, first, freedom threatened by social pressure leads to the denial of such pressure, most typically by knowledge denial (“we didn't know” or “we weren't really sure” [Phillips, Citation2012]). There is extensive evidence of the great lengths to which society has undergone to deny the consequences of climate change (Klein, Citation2014; Lorenzoni, Nicholson-Cole, & Whitmarsh, Citation2007) and the limited progress made in decarbonising travel and tourism as a result (Hall et al., Citation2015; Scott, Gössling, Hall, & Peeters, Citation2016). Any trade-offs between the individual and the group, concern the pressure to comply with group norms, with short-term individual sacrifice being required for the long-term benefit of the group (Sen, Gürhan-Canli, & Morwitz, Citation2001). Individuals mainly act in their own best interest when this is at odds with collective interests (VanLange, Liebrand, Messick, & Wilke, Citation1992). Denial acts to maintain the attitude–behaviour gap with regard to climate change norms (Stoll-Kleemann, O'Riordan, & Jaeger, Citation2001) and therefore allows for disassociation from involvement in possible solutions (Lorenzoni & Pidgeon, Citation2006). It is therefore expected that one will defend personal behaviour but not acknowledge that this is driven by reactance (Brehm, Citation1966).

Second, a consumer's need to reduce tension means that when there are differences between their personal beliefs and behaviours, they will seek to eliminate the inconsistencies of this cognitive dissonance by aligning or adjusting their beliefs and/or behaviours (Schwartz, Citation1992). Juvan and Dolnicar (Citation2014) reported the most detailed account of attempts to re-establish consonance between environmental beliefs and travel behaviours, including denial of consequences, downward comparison, denial of responsibility, denial of control, exception handling and compensation through benefits. The dissonance of human presence in remote locations, and the corresponding carbon footprint, is rarely acknowledged and commonly retrospectively justified by “I won't do it again - in that place”. The temporary nature of travel gives privileges to the traveller and tourists make the most of the opportunity, while justifying, as a special case, out of the ordinary or excessive behaviour. The distancing from daily realities allows them to reframe their responsibility and normalise the versions of truth that they are comfortable with (Grimwood, Yudina, Muldoon, & Qiu, Citation2015). For example, Malone, McCabe, and Smith (Citation2014) explain that hedonism is used to rationalise and reinforce ethical holiday choices of a constructed ethical reality, which compensates for the, often climate change related, impacts. A further example of reducing tension between competing values is self-justification in the name of social ambassadorship, which is travelling in the name of raising awareness amongst peers, of the importance of conservation (Eijgelaar et al., Citation2010).

As a result of cognitive dissonance, individuals apportion blame to assert their freedom of responsibility, in the form of control denial (“we knew, but couldn't do anything about it”) and connection denial (“whether we knew or not, it's the responsibility of someone else” [Phillips, Citation2012]). Reactance is often directed at the social acts of others, who have limited one's choices (Brehm, Citation1966). Blaming others for creating climate change that limits one's own ability to travel is not unlike a driver blaming all other drivers (while excluding themselves) for a traffic jam. There is dissonance in attributing climate change to one's flying because travel is a personal right, despite denying others the same right for the good of the planet (Hall, Scott, & Gössling, Citation2013). Both Hares, Dickinson, and Wilkes (Citation2010) and Hindley and Font (Citation2014) found that consumers blame both the occurrence of climate change and the responsibility for addressing it on governments, businesses and other countries, but not on individual travellers, because these supposedly lack behavioural control. Those better informed about climate change employ “denial of responsibility”, because low self-efficacy makes them feel less, rather than more responsible for it (Norgaard, Citation2011).

Third, reactance is typified by an overreaction therefore, because the endangered issue or the item is valued more than previously, consumers who are aware of such a threat are expected to reassert their freedom by demanding the threatened item more than before. This explains, for example, how Svalbard recorded a 32% increase in foreign tourist guest nights in the year to February 2013 in response to greater awareness of the disappearance of the habitats of polar bears (Statistics Norway, Citation2014), and the existence of many other, similar accounts from places publicised as being under threat of disappearing (Lemelin et al., Citation2012). This scarcity effect is often used by marketers to increase the subjective desirability of products (Cialdini, Citation2009; Dawson et al., Citation2011; Jung & Kellaris, Citation2004). As Lemelin et al. (Citation2010) contend, perceptions of rarity are fuelled or manipulated by various interest groups (such as travel operators, marketers, the scientific community and researchers) who often argue for a call to action.

The loss of unique landscapes, because of climate change impacts, is part of the rationale for Last Chance Tourism (Lemelin et al., Citation2010). Yet, Last Chance Tourism itself accounts for a disproportionate amount of greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to the disappearance of those destinations (Dawson et al., Citation2011; Eijgelaar et al., Citation2010). This hedonic consumption of tourism is the result of a “construction of a desired ethical reality beyond its objective context” that creates the perception of a positive impact and compensates for known negative impacts (Malone, McCabe, & Smith, Citation2014, p. 250). Moreover, it allows self-declared responsible travellers to engage more in travel (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014).

Fourth, tourists display helplessness (Brehm & Brehm, Citation1981) when their expectation of being able to do something is jeopardised. They become aware that they were going to fail to achieve what they wanted, or that a freedom is lost rather than simply threatened, and, as a result, they give up having that expectation. Individuals subjectively decrease or dismiss the attractiveness of the desired object or behaviour when it is clear that it is no longer an option. Individuals often also reassert their freedom by social implication, as disapproval of impacts arguably caused by others can result in avoiding certain destinations, leading to a sense of superiority (Malone et al., Citation2014). Psychogenic needs, acquired in the process of becoming a member of a culture (e.g. status, power, affiliation) are activated depending on stimuli external to the individual (Burger, Citation2008). Recognition (the need to gain approval and social status) accounts for the need “to keep up with the Joneses”, hence freedom re-established by implication can include engaging in alternative behaviour of the same class (travel to a destination similar to those being threatened), or by social implication (travelling to other destinations favoured by peers). The parallels with Plog's model of psychocentrism–allocentrism provide ample evidence of the reasons for destination decline as typologies of tourists stop desiring them (Plog, Citation2001).

Method

Projective techniques were chosen for their ability: (1) to circumvent rational thought and normative responses (Porr, Mayan, Graffigna, Wall, & Vieira, Citation2011), (2) to reach an understanding of both surface and deeper psychological motives (Carducci, Citation2009), and (3) to explore the denial of socially undesirable actions or behaviours (Chung & Monroe, Citation2003). An interpretivist approach is selected to model the typical meanings of Last Chance Tourism (Blaikie, Citation2009). A relativist ontology is subscribed to, as there are multiple realities (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, & Jackson, Citation2012), such as a selfish desire to see a destination before it disappears or an altruistic desire to help the locals, perhaps through dissemination of the experience of the destination visit. A subjectivist epistemology is employed as judgements on analysis and interpretation of the resulting data are made by the researcher (Blaikie, Citation2009). A value-laden axiology is selected as the researcher role will be to uncover the conscious and unconscious explanations of participants (McGregor & Murnane, Citation2010). A naturalistic inquiry focuses on the quality and richness of information in an investigation of the phenomena as a whole (Decrop, Citation2006). With no handbook to offer guidance on which projective techniques to employ, most researchers design their own materials (Bond & Ramsey, Citation2010).

Photo-expression, through its indirect questioning procedure, could reveal tourists’ motivations for visiting destinations that are disappearing because of climate change. Photo-expression is a semi-projective, photo-elicitation technique, where the respondent takes photographs of what is important to them (Hurworth, Clark, Martin, & Thomsen, Citation2005) and a story is constructed from the stimulus (Donoghue, Citation2000; Soley & Smith, Citation2008). Tourist photography transcribes “miniature slices of reality”, with idealised images constructed to beautify the object being photographed (Urry, Citation2002, p. 127). This subjective and objective reality (Urry, Citation2002) is captured in an instant so that holiday photographs can provide a future substitute for what time will destroy (Bourdieu, Citation1990).

The SHOWED (“what do you See here?”, “what's really Happening here?”, “how does this relate to Our lives?”, “why does this problem, concern or strength Exist?” and “what can we Do about it?”) questioning procedure is designed for use with photo-expression and leads respondents to think about problems and solutions (Soley & Smith, Citation2008, p. 105). For this study, the procedure required modification because holiday photographs were unlikely to present negative images. Finding workable phrasing was a limitation of the method, but “what is happening in your pictures?” and “how do these pictures relate to your life?” worked well in the pilot study. The final question needed to be more contrived, as the pilot returned no perceived “problems” of any description. To determine if climate change was a motivation to visit the destination, it was decided to employ a leading phrase “thinking about the location in your photographs, what possible environmental issues could you resolve?” In advance of the interviews, Venice and Svalbard respondents were instructed, “Please select two of your favourite holiday photographs from […] and bring them to …”

Narratives produced in direct response to a specified projective technique were assessed for a specified aspect of consumer behaviour. The collage technique directly assessed influences, photo-interviewing directly assessed beliefs and scenarios directly assessed ethics. Through indirect assessment, these narratives were also able to reveal other consumer behaviour aspects in the study. Projective techniques are often used to analyse the narrative of the participants to justify their choices made, but we found that the use of multiple techniques, in conjunction with one another, can also expose insights related to their motivations for travel.

The collage technique initially stimulates non-verbal activity but then goes on to stimulate verbal responses when probed for meaning (Boddy, Citation2007). No artistic skills are required for collage construction (Koll, von Wallpach, & Kreuzer, Citation2010) as respondents are able to pull together images at random from the materials or collections provided (Boddy, Citation2007; Gonzalez Fernandez, Rodriguez Santos, & Cervantes Blanco, Citation2005). Photo-interviewing elicits cognitive evaluations about real situations by using images that represent significant behaviours or places (Soley & Smith, Citation2008). Respondents explain what they see in the photos, revealing clearer responses than questions alone can achieve (Soley & Smith, Citation2008). In the Hunt–Vitell model, scenarios assist in determining how respondents make decisions that involve ethical issues, and the extent to which they rely on ethical norms (deontology) versus the perceived consequences (teleology) (Vitell, Singhapakdi, & Thomas, Citation2001). Three factors, namely ethical judgements, prevailing social norms and intentions, are assessed through a participant's agreement or disagreement with given statements (Vitell et al., Citation2001).

Purposive sampling is normally used with respondents who have been deliberately selected for certain characteristics of interest to the study (Hennink, Citation2007; Ritchie & Lewis, Citation2003). Devinney, Auger, and Eckhardt (Citation2010) assert that research has failed to focus on the complete range of consumers (i.e. those who act ethically and those who do not). Szmigin and Carrigan (Citation2005) categorise consumers as “non-ethical consumers” who are ethical some of the time, and “ethical consumers” who are not ethical all of the time, because they cannot ensure that everything they purchase is ethically produced. In recognition of these two arguments, the sample for this study was taken from the entire population of visitors to Svalbard and Venice, which was assumed to be heterogeneous.

The narratives of 23 respondents provided evidence that was interpreted through reactance theory and was seen to be consistent with similar studies (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014). The sample was sufficient for theory testing and achieved surprisingly quick data saturation (see such as Mason, Citation2010). The sample was split between direct and indirect responses as well as between destinations and stages in the customer journey. Eight direct participants produced motivation narrative in response to the photo-expression technique, while 15 indirect respondents produced narrative responses to other projective techniques, which were then indirectly assessed for motivation.

The eight direct participants comprised four Venice participants (one during-visit and three post-visit, coded DV and PV, and then numbered) and four Svalbard participants (one during-visit and three post-visit, coded DS and PS, also numbered). The 15 indirect respondents comprised 5 Venice (two before-visit, three post-visit) and 10 Svalbard respondents (three before-visit, three during-visit and five post-visit), with coding and numbering continuing as previously described. “During-visit” interviews were conducted in the destinations, while “before-visit” and “post-visit” interviews were conducted in the UK. No interviews were conducted with individuals who had specifically chosen not to travel to these destinations; either because of the damage caused by their own travel or that already caused by previous travellers, who had deemed the place noteworthy of visit. Therefore, no data were uncovered on helplessness (stage 4).

The destinations of Svalbard and Venice were selected because of their contrasting environments and visitor numbers. The Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard is a natural environment located between Norway and the North Pole, whereas the Italian city of Venice is a built environment, consisting of 116 islands and a system of canals (Bing & Landon, Citation2012; Umbreit, Citation2013; World Travel Guide, Citation2012). In 2013, 107,000 tourists visited Svalbard, whereas 9.8 million tourists visited Venice (Città di Venezia, Citation2014; Statistics Norway, Citation2015).

Potentially influencing consumer decision-making, both destinations had been “popularly reported” as disappearing due to the impacts of climate change. Such reports appeared in travel guides (such as Fodor's Travel, Citation2013), press reports (Willis, Citation2015), BBC documentaries and targeted campaigns such as the WWF campaign to adopt a Svalbard polar bear (WWF UK, Citation2015). The participant sample was predominantly achieved through requests for research volunteers using message boards, holiday exhibitions, local press, direct communications (phone, email and face-to-face) and holidays taken by one researcher.

A limitation of the sampling method was the difficulty in recruiting the post-visit Svalbard sample. This was ultimately resolved by using one Greenland respondent and one Antarctica respondent, both of whom were considered acceptable alternatives, because of environmental and visitor number similarities of these destinations to Svalbard. Environmentally, the cryosphere is the dominant feature in both polar regions, there are common temperature regimes and the effects of climate change will be particularly intense in the polar regions (Pienitz, Douglas, & Smol, Citation2007). In terms of tourist numbers, around 100,000 tourists stayed in Greenland accommodation during 2013, while around 37,400 tourists visited Antarctica (IAATO, Citation2015; Statistics Greenland, Citation2015).

As their source data, data triangulation used the customer journey stages (before-visit, during-visit and post-visit), environmental triangulation used contrasting destinations (Venice and Svalbard), and methodological triangulation used “within methods” and “between methods” (Flick et al., Citation2007). The narrative was recorded using a tablet and the transcription was subsequently analysed for patterns and themes. As the use of computer-based analysis could potentially result in a failure to detect emerging themes (or impact on the cognitive processes of the researcher) a manual analysis approach was employed (Davidson & Skinner, Citation2010).

The summaries from each respondent were triangulated within the customer journey and destination sample groups. Emerging themes were identified and a summary report (including a brief interpretation of the findings) was completed. Quotes from the questions posed in photo-expression, collage design justifications, photo-interviewing explanations and reasoning for choices in the scenarios technique were used collectively to exemplify evidence for the four stages. While quotes from these narratives, now out of context, could be questionably placed under a different stage, they were chosen to exemplify more complex discourses the respondents used to justify their answers.

Results

Stage 1. Denying the threat

Knowledge/problem denial is the most classic form of reactance until the threat is more imminent (Brehm, Citation1966). Overall the Venice narrative response on environmental problems suggested that what travellers perceived they could resolve is limited. The images they took did not help them make the link between their travel choice and the impacts caused on the destination (see Image 1). The arising themes centred on flooding, responsibility and pollution. Two Venice respondents struggled to identify environmental impacts or provide solutions. They focused on visible impacts such as “the water is polluted”, “the water is smelly” and “only pigeons I suppose” (PV1), and they commented “… I haven't a clue … [and there is] … nothing I could change” (PV2). This reflects the sentiments of both knowledge of, yet personal denial of, the direct effects of climate change (Phillips, Citation2012), which allows for dissociation from involvement in possible solutions (Lorenzoni & Pidgeon, Citation2006). When faced with four photos showing St Mark's Square flooded and not flooded, and an extensive ice glacier compared to one with very little ice left years later, PV4 said to the question: What do you think is happening in these pictures?

First and foremost I think it looks like there has been a flood. So top left hand one, it looks like there has been a flood in St Mark's Square. Top right one, looks like a normal day. Bottom left, definitely a flood, severe and bottom right a cool winter day, I would suggest.

When PV4 was asked how these pictures relate to our lives, their answer referred back to the attractiveness of the places in terms of visiting them (“looks very empty and not very dynamic”), and when asked about how to resolve the problems their response related to raising awareness in tourists of when to visit in order to avoid the risk of encountering floods; they did not refer to raising awareness about the causes of flooding.

The subconscious motivation of consumers to visit a disappearing destination could be determined by environmental pressures, combined with the need for self-fulfilment and cognisance. However, within the motivations narrative there is no evidence that any need is determined directly by a connection between tourism and the environment. This reflects the results of previous research, which has indicated that the level of awareness of climate change amongst tourists is low, questionable or seen not to contribute (Becken, Citation2004, Citation2007; Gössling & Peeters, Citation2007; Shaw & Thomas, Citation2006; Whitmarsh, Citation2009). If we accept that an individual's level of awareness has a bearing on their motivation to take personal responsibility, then we can conclude that low levels of awareness (i.e. low appreciation of their personal impacts) will inevitably result in low, or no, responsibility being taken. Answers within this stage often support this argument, including statements such as: “I haven't a clue” or “there is nothing I could change” (PV2).

(See Image 1, which can be found in the Supplementary Data section of the web-based version of this paper.)

Stage 2. Reducing tensions

The narrative obtained from consumers visiting Svalbard was more extensive than for those visiting Venice, with arising themes centred on awareness, responsibility and behaviour. Perhaps it was a greater appreciation of the fragile nature of Svalbard that accounted for the greater environmental awareness evidenced. Image 2 was typical of the photos brought by the respondents, in that global warming was explicitly mentioned (PS3) and there was a high level of awareness that “… the melting of the icecap could cause serious problems …” (PS3). A visit to the destination “… made me much more environmentally aware of my carbon footprint …” (PS3). This personal experience was offered as a proposed solution to the question of how to increase others’ awareness: “… more people need to see this to make them think, wow!” (PS3). Yet ambassadorship is a form of reassertion of freedom by aligning competing values, a classic Last Chance Tourism social justification for travel (Eijgelaar et al., Citation2010).

In general, the narrative from both sets of respondents suggested that they consider individuals to be deserving of a holiday and there was a lack of inclination to change: “you only go on holiday once a year” (PS3), “[there is] nothing I could change” (PV2) and “the only way to get to these places is by flying” (PS3). These beliefs inevitably have a bearing on their motivations to take responsibility for their own individual contribution to overall impacts. For example, when DS4 was asked why most people would act the same as the protagonist in a given scenario, the response was a reflection on a previous holiday choice:

I went to Antarctica (it took eight years to be able to do this) for my 50th birthday. I wanted to go there for ages. I went. What was my impact? I don't know; perhaps one chick died because the mother was stressed; I don't know. I try not to come too close, because we had so many metres not coming close to them. I try to behave, I try not to be in their way, but I was really amazed to be there and I know that everybody has to make the effort of not intruding more in their life. I saw first hand how badly this can go, but if I had the chance I would go back any time and I know it's very selfish, but it's like that.

(See Image 2, which can be found in the Supplementary Data section of the web-based version of this paper.)

The freedoms articulated in tourists’ accounts were part of an effort to normalise their behaviour in accordance to the context they were in and the perceived social expectations placed on them (Caruana & Crane, Citation2011; Hollinshead, Citation1994), which may explain why Svalbard tourists felt more compelled to acknowledge climate change. Citation Caruana and Crane (2011) find that a responsible tourism discourse (bound by ethical considerations) limits the freedom of travellers in comparison to an independent traveller discourse (prompted to discover the destination's backstage). This is similar to findings of pro-environmentalists’ justification for their travel (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014). Yet previous studies also found that part of the responsible tourism discourse legitimises the presence of tourists backstage, when that presence is mediated by its own normalised, ethical behaviour. The individual responsibility theme in both the Venice and Svalbard narratives emphasised the independent traveller's desire for freedom to discover without the added responsibility of moralising. This produced the common notion that “minimising one's detrimental impact is quite possible” (DV1) but “I think my effect would be a drop in the ocean” (PS3). This cognitive dissonance reduction (or avoidance of action, for example “I cannot resolve much” [DS2]) was satisfied by the need to justify one's actions.

Throughout the narratives, the consequences of travel received little consideration and the result was that individuals were willing to compromise how ethically they behaved: “… the melting of the ice-cap could cause serious problems …” (PP3) but “… you only go on holiday once a year …” (PS3). This result supports the findings of Caruana et al (Citation2014), who find that tourists’ level of involvement in responsible tourism relates to their self-identity and their efforts to present a moral self. They find that “interviewees could convey a fluid sense of ethicality that fitted their own sense of self without committing to a high level of involvement … even where there is an explicit understanding that responsible tourism involves sacrifices, obligations and commitments, respondents’ narratives ring-fenced their own holiday at the lower end of involvement” (2014, p. 123). Environmental psychological reactance and identity threat are overlapping behaviour constructs, and the defensive of one's right to impact on the environment has been explained as a result of the threat to one's identity (Murtagh, Gatersleben, & Uzzell, Citation2012). We interpret this as reactance to any restrictions on their freedom, which subsequently leads them to engage in travel behaviours that arise from their need to satisfy their personal goals.

There was extensive evidence in the narrative of individuals constructing discourses to apportion blame for the behaviour they wanted to engage in. Although most air travellers believe that climate change is real and that it is a problem to which aviation contributes, only about one-third admit that emissions caused by flying are their personal responsibility (Gössling, Haglund, Kallgren, Revahl, & Hultman, Citation2009). For example, only one Venice respondent identified flooding as an environmental threat, suggesting “… if the water rises too much, the city will sink …” and “… it would be a pity if Venice cannot survive because of floods …” (PV3). However, although they considered flooding to be “one of the obvious things” (PV3) they proposed no solutions to resolve the problem, suggesting responsibility denial as a form of restoring freedom. Likewise, one respondent apportioned blame by saying that “Whether he goes or doesn't go, the flight will fly; the flight will go anyway” (DS4).

In contrast, one respondent considered that “minimising one's detrimental [environmental] impact is possible” (DV1), which suggested that they were taking personal responsibility. They proposed “using overland public transport rather than flying” (DV1), thus making an explicit link between carbon emissions from transportation, climate change and flooding. This respondent went on to suggest that tackling such issues requires “continued involvement (financial, campaigning etc.) with groups working for environmental change [which] can bring results” (DV1). Nevertheless, having articulated possible ways to resolve environmental issues, they considered that the “resolution of environmental issues by one person would be unlikely” (DV1), which appeared to be a case of dissonance reduction through reducing tensions, i.e. the person reasserted their freedom as a result of having acknowledged the issue, as if this already provided a moral high ground (Brehm, Citation1966). A good example of apportioning blame can be seen in the response by DS4 to a scenario in which the protagonist (Kai) chooses not to travel due to carbon emissions. When asked to evaluate whether the choices made were the right ones, DS4 apportioned blame on the locals as well as other travellers:

if I wanted to go somewhere, I would go, knowing that the impact would be pollution of the atmosphere. Then I would try, as I said before, to behave. Not to hurt or to be offensive towards the population and to behave in accordance to the places I am going to … Not to go and help the planet – that's giving a lot of credit I would say, because no matter what, it would mean a lot more people behaving the same way and people are selfish that way, so most people wouldn't do according to what Kai is doing. I have seen people behave and misbehave, so I'm not too optimistic, but also I have been surprised many times by people locally one at a time, but mass population has a tendency to really not care because they are in mass and the other is doing it the right way, so good thing for Kai not going, but I am a little more selfish, I would go.

Nevertheless, the narrative that “… if everyone does their bit, then it helps …” (PS3), certainly seemed to suggest that taking personal responsibility and sharing the load can result in a good outcome. However, countering this with “… my effect would be a drop in the ocean …” (PS3) or “… I cannot resolve much …” (DS2) were attempts to apportion blame on others for not working together, or to engage in control denial (“we knew, but couldn't do anything about it”). The above are examples of reactance by apportioning blame for a global problem (Brehm, Citation1966) to reduce tension by suggesting that one's values are not the reason for climate change (Schwartz, Citation1992). Clearly, changing behaviour will not be so straightforward, not least because “trying to behave [is] … a goal” (DS2), and yet the rhetoric revealed coping strategies triggered by threats to their earned right to travel.

Stage 3. Heightened demand

Freedom gained from travel is essential to today's understanding of society, framed as liberation (freedom from the daily reality) and licence (freedom to behave differently) (Caruana & Crane, Citation2011; Ross & Iso-Ahola, Citation1991). In fact, this freedom is so central to today's society that the increased demand arising from the threat of losing control over one's ability to travel only became apparent as the conversations developed, when it became evident how the motivational power of scarcity, combined with diminishing availability, increased the general desire to want or possess the “disappearing destination” more than before (Brehm, Citation1966; Brehm & Brehm, Citation1981).

In this study, some of the responses acknowledged “we want to go [to disappearing destinations] because they are disappearing … [we] want to go and visit before they disappear” (BS2). Self-fulfilment and need satisfaction were evident in the beliefs of those travelling to Svalbard, for example “everybody is looking for something that he has not got in his ordinary life” (DS1). The narrative for both destinations centred either on the individual (or self), where there was a tendency to “… just do what is best for you” (BV1) or on conscious altruism, which required “… a set reason to help the locals [that] would dictate the destination they go to” (PS2). Even those aware of their own carbon footprint and possessing a desire to make others think about it, seemed willing to admit “it probably wouldn't stop me flying” (PS3). A good example of this was seen in DS4's responses. Despite having shown great awareness of climate change earlier in the scenario justification, further into the interview, in relation to Svalbard, they made reference to their once in a lifetime opportunity to see and do things while the opportunity is still there:

I asked one of the tour guides if there was a helicopter company and she said it is forbidden and she felt very strongly about that, it was a very warning answer in a way, because it was ‘no way’ and that's good that she could not answer differently, so I understand that we are trying to save this archipelago. As a tourist, I regret not being able to see it from a different angle, as a person, trying to save a little bit of the planet, and still, there is regret, but if I had the possibility, I would have taken the helicopter, so, the way it goes, it helps and doesn't go and impact, it's selfish and selfish but served according to each action we are doing.

Herein is the denial that acts to maintain the climate change norms attitude–behaviour gap (Stoll-Kleemann et al., Citation2001), the individual is protecting the hedonistic travel rights they have already gained by re-establishing their freedom. There is a need for personal growth that can result in iconic experience goal setting “it is something we had to do once in our life” (PV3), but as each goal is achieved (or need fulfilled) it is then pursued by another “to see nothing else but ice for 1000 kilometres just blew my mind. I would so like to [cross] that” (PS3). Environmental pressures then determine the new goals (Burger, Citation2008), resulting in those who “… want to go [to disappearing destinations] because they are disappearing” (BS2).

The experience of this different travel motivation was reflected in an awareness of climate change related factors, which remain latent until triggered by indirect questioning techniques. A Venice respondent considered “it would be a pity if Venice cannot survive because of floods” (PV3), but the Svalbard respondents had a heightened awareness. The visit “… gave me a perspective on the sea levels which are going to rise if the ice melts” (PS3). It gave “… insight into global warming” (PS3) and “it made me much more environmentally aware of my carbon footprint” (PS3). Nevertheless, despite this heightened awareness and personal experience “it probably wouldn't stop me flying” (PS3), because “you only go on holiday once a year” (PS3) and environmental behaviour is aspirational, seen for example in saying that “… trying to behave has been a goal for 30-35 years” (DS2).

Conclusion

Reactance theory overlaps with other psychological theories to explain behaviour (Murtagh et al., Citation2012). Although the results could have been interpreted with cognitive dissonance theory, tackling them through reactance theory allowed for a more nuanced understanding of resistance to change as the explanatory mechanism for the lack of progress in behaviour change is induced by raising environmental awareness. The difference is that other theories appeal to reason and judgement as the trigger to behaviour change, while theories focusing on resistance to change (such as reactance theory and identity process theory) focus on the threats imposed on behaviour as triggers to coping strategies.

This paper argues that reactance has a unique value in explaining how tourists will respond to efforts to raise awareness of climate change. adapts Miron and Brehm's energisation model of reactance to show the level of energy committed to restore a threatened freedom. Notwithstanding the limitations of linear models of social change (Cohen, Citation1979), this article argues that there is value in postulating that the amount of energy tourists will dedicate to restore their perceived right to travel will depend on (1) their knowledge of climate change as a threat to travel and (2) the probability of success in restoring their freedom to travel. The model suggests that when a person does not know how difficult it will be to restore a threatened behaviour, they will mobilise as many available resources to restore their right as they consider the behaviour to be worth. This is evident in the substantial effort of climate change deniers to reframe all efforts of climate change policy as anti-capitalist, as reported in detail by Klein (Citation2014). We argue that consumers will go to great lengths to deny a threat (stage 1) such as climate change, because they perceive that threat as fundamentally challenging the dominant social paradigm of consumerism and Western lifestyle to which they belong. At this stage, they also lack the knowledge of how difficult it would be to live and travel sustainably. When a person believes a freedom would be easy to restore, they will perceive little reactance. As their knowledge of climate change and sustainable travel options increases, the perception of threat is arguably reduced, not because they consider the options unimportant, but because they are aware of the social unacceptability of prohibiting travel (Thøgersen, Citation2005). Hence in stage 2, the reaction is to reduce tensions by justifying the social acceptability of their behaviour.

As the awareness of the threat to their freedom increases, through more knowledge of the likelihood of threats to their lifestyle in general and, in particular, not being able to travel to desired destinations, the perception of restoring the freedom to travel will increase, and subsequently the intensity of reactance, hence mobilising more resources to resume their rights to travel. This will result in heightened demand for the threatened destinations (stage 3). Because reactance is context-specific, tourists will perceive the threat imposed by climate change on travel at different stages, depending on the characteristics of the destination, hence the phenomenon of Last Chance Tourism being more observable in places such as Svalbard than Venice. Ultimately, tourists stop desiring to travel to places that they perceive have lost their appeal, explained as helplessness (stage 4). The growth and dismissal stages (3 and 4) have parallels with Butler's tourism lifecycle model (Citation1980) and are best exemplified by Last Chance Tourism's emotional response to the threat of not being able to visit a destination because it is disappearing (Dawson et al., Citation2011, p. 255).

Reactance theory speaks of the consequences of raising awareness of an issue amongst consumers, this being the cognitive and behavioural adjustments needed to defend oneself from the threat of losing freedom to act, which can result in resistance to change. An increased awareness of the impacts, which can be attributed to the consumer's behaviour and point to their need to take responsibility, will inevitably create discomfort. The rhetoric of the rationalisation for consumer choices primarily reflects the hedonism of travel, while acknowledgement of the impacts of their choices, and of their own personal responsibility for those impacts, only arises as research goes deeper, with increasingly probing questions. Furthermore, such acknowledgements were couched in carefully chosen words of how rare their travel behaviour is and how their impact is negligible in the greater scheme of things. Each of these stages is a freedom-restoration behaviour even though some of this evidence can be explained by other theories (cognitive dissonance in particular). Yet the value of considering it through reactance theory is to acknowledge head-on the ineffectiveness of awareness-raising as a behaviour change approach (Hares et al., Citation2010; Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014; Prillwitz & Barr, Citation2011). The findings of this study demonstrate the difficulties of promoting positive behaviour change in response to raised awareness and have particular relevance in the design of social marketing interventions (Hall, Citation2016).

In this study, we face the wicked problem of the social need to raise awareness of climate change impacts, which is surely necessary to create the beliefs and feed the social values necessary to save the planet, while recognising that in so doing, it can backfire by creating resistance to change, which promotes the over-consumption of the desired objects, in our case most visible through what is known as Last Chance Tourism. Awareness of environmental impacts may not be the vehicle to move from the denial of consequences to enlightened pro-environmental behaviour (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014; Miller et al., Citation2010) and awareness-raising policies may be ineffective when a traditional segment of society sees environmentalism as a threat to the status quo (Campbell & Kay, Citation2014). Reactance, as a motivational force, has the effect of increasing the intent to visit a disappearing destination, until it loses its appeal and is discarded. Hoffarth and Hodson (Citation2016) suggest that threats to one's identity and differences between inter-group identity will increase reactance to climate change and that policy instruments to promote pro-environmental behaviour should focus on the benefits of a broader group identity. For travel specifically, efforts to promote behavioural change need to complement existing self-interest behaviours (Caruana et al., Citation2014) and provide an alternative but equally hedonistic holiday choice (Malone et al., Citation2014). Promoting sustainable behaviour through offering alternative choices may be a better strategy than simply awareness-raising per se. Offering alternatives that provide equally fulfilling, but less impacting, holidays, or by positively framing the benefits of the more sustainable options in relation to the purchasing attributes sought by consumers (Gunn & Mont, Citation2014) may prove more effective. These are conclusions reached, however, with a heavy heart, for surely they undermine the long-term need to create a social conscience that common sense would suggest is necessary to reach climate change solutions.

If nothing else, this study is further proof of the complexity of engaging consumers in the protection of the environment and may partly explain the failures of some pro-environmental behaviour campaigns. It shows how, collectively, we require a better understanding of consumer behaviour in relation to motivations, which is far more complex than suggested by simple surveys of environmental awareness and purchasing. In practical terms, this research better informs the consultancy practices of our team when designing and testing methods to promote mainstreaming the consumption of sustainable tourism products. The findings help us to identify socially acceptable forms of marketing and communication of the sustainability practices of tourism businesses, specifically intended to reduce resistance to change, while finding more subtle ways to inform consumers of the benefits to themselves of engaging in sustainability practices.

RSUS_1165235_Supplementary_Material.zip

Download Zip (1.9 MB)Acknowledgments

This article was presented at the COP21 side event “Tourism and the International Climate and Sustainable Development Agenda: The Path to Low Carbon Development” in Paris on 11 December 2015, to inform the debate about validity of policy instruments to promote sustainable production and consumption in the context of tourism's contribution to climate change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Xavier Font

Dr Xavier Font is a reader at the International Centre for Research in Events, Tourism and Hospitality at Leeds Beckett University, UK. His research focuses on understanding reasons for pro-sustainability behaviour and market-based mechanisms to encourage sustainable production and consumption.

Ann Hindley

Dr Ann Hindley is a senior lecturer in tourism management at the University of Chester, UK. Her research focuses on consumer behaviour aspects of climate change and tourism and the use of projective techniques to avoid social desirability bias.

References

- Barr, S., Shaw, G., Coles, T., & Prillwitz, J. (2010). ‘A holiday is a holiday’: Practicing sustainability, home and away. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(3), 474–481.

- Becken, S. (2004). How tourists and tourism experts perceive climate change and carbon-offsetting schemes. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 12(4), 332–345.

- Becken, S. (2007). Tourists’ perception of international air travel's impact on the global climate and potential climate change policies. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(4), 351–368.

- Bing, A., & Landon, R. (2012). Lonely Planet Venice & the Veneto (7th ed.). London: Lonely Planet.

- Blaikie, N. (2009). Designing social research. Cambridge: Polity.

- Boddy, C. (2007). Projective techniques in Taiwan and Asia-Pacific market research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 10(1), 48–62.

- Bond, D., & Ramsey, E. (2010). The role of information and communication technologies in using projective techniques as survey tools to meet the challenges of bounded rationality. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 13, 430–440.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). Photography: A middle-brow art (S. Whiteside, Trans.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Brehm, J. (1966). Theory of psychological reactance. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Brehm, S., & Brehm, J. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Burger, J. (2008). Personality (Vol. 7). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Butler, R.W. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24, 5–12.

- Campbell, T.H., & Kay, A.C. (2014). Solution aversion: On the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 809–824.

- Carducci, B. (2009). The psychology of personality: Viewpoints, research, and applications. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Caruana, R., & Crane, A. (2011). Getting away from it all: Exploring freedom in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1495–1515.

- Caruana, R., Glozer, S., Crane, A., & McCabe, S. (2014). Tourists’ accounts of responsible tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 46, 115–129.

- Chung, J., & Monroe, G.S. (2003). Exploring social desirability bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(4), 291–302.

- Cialdini, R.B. (2009). Influence: Science and practice (Vol. 4). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

- Città di Venezia. (2014, May 31). The Annual Tourism Survey presented yesterday in Venice: Figures help the city decide how to manage flows efficiently. Retrieved 29 December 2015 from http://www.comune.venezia.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/74151

- Cohen, E. (1979). Rethinking the sociology of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(1), 18–35.

- Davidson, L., & Skinner, H. (2010). I spy with my little eye: A comparison of manual versus computer-aided analysis of data gathered by projective techniques. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 13, 441–459.

- Dawson, J., Johnston, M.J., Stewart, E.J., Lemieux, C.J., Lemelin, R.H., Maher, P.T., & Grimwood, B.S.R. (2011). Ethical considerations of last chance tourism. Journal of Ecotourism, 10(3), 250–265.

- Decrop, A. (2006). Vacation decision making. Oxon: CABI.

- Devinney, T.M., Auger, P., & Eckhardt, G.M. (2010). The myth of the ethical consumer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Donoghue, S. (2000). Projective techniques in consumer research. Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences, 28, 47–53.

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Jackson, P. (2012). Management research. London: Sage.

- Eijgelaar, E., Thaper, C., & Peeters, P. (2010). Antarctic cruise tourism: The paradoxes of ambassadorship,‘last chance tourism’ and greenhouse gas emissions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(3), 337–354.

- Flick, U., Kvale, S., Angrosino, M.V., Barbour, R.S., Banks, M., Gibbs, G., & Rapley, T. (2007). Qualitative research kit. London: Sage.

- Fodor's Travel. (2013, November 5). 10 places to see before they're gone. Retrieved 28 December 2015 from http://www.fodors.com/news/photos/10-places-to-see-before-theyre-gone

- Gifford, R. (2008). Psychology's essential role in alleviating the impacts of climate change. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(4), 273–280.

- Gifford, R. (2011). The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. American Psychologist, 66(4), 290–302.

- Gonzalez Fernandez, A.M., Rodriguez Santos, M.C., & Cervantes Blanco, M. (2005). Measuring the image of a cultural tourism destination through the collage technique in cultural tourism research methods. In G. Richards & W. Munsters (Eds.), Tourism research methods: Integrating theory with practice (pp. P156–172). Wallingford: CABI.

- Gössling, S., Haglund, L., Kallgren, H., Revahl, M., & Hultman, J. (2009). Swedish air travellers and voluntary carbon offsets: Towards the co-creation of environmental value? Current Issues in Tourism, 12(1), 1–19.

- Gössling, S., & Peeters, P. (2007). It does not harm the environment! An analysis of industry discourses on tourism, air travel and the environment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(4), 402–417.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C.M. (2013). Challenges of tourism in a low-carbon economy. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 4(6), 525–538.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., Hall, C.M., Ceron, J.P., & Dubois, G. (2012). Consumer behaviour and demand response of tourists to climate change. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 36–58.

- Grimwood, B.S., Yudina, O., Muldoon, M., & Qiu, J. (2015). Responsibility in tourism: A discursive analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 50, 22–38.

- Gunn, M., & Mont, O. (2014). Choice editing as a retailers’ tool for sustainable consumption. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 42(6), 464–481.

- Hall, C.M. (2016). Intervening in academic interventions: framing social marketing's potential for successful sustainable tourism behavioural change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(3), 350–375.

- Hall, C.M., Amelung, B., Cohen, S., Eijgelaar, E., Gössling, S., Higham, J., … Scott, D. (2015). On climate change skepticism and denial in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(1), 4–25.

- Hall, C.M., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2013). The primacy of climate change for sustainable international tourism. Sustainable Development, 21(2), 112–121.

- Hares, A., Dickinson, J., & Wilkes, K. (2010). Climate change and the air travel decisions of UK tourists. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(3), 466–473.

- Hennink, M.M. (2007). International focus group research: A handbook for the health and social sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Higham, J., Cohen, S.A., & Cavaliere, C.T. (2014). Climate change, discretionary air travel, and the ‘flyers’ dilemma’. Journal of Travel Research, 53(4), 462–475.

- Hindley, A., & Font, X. (2014). Ethics and influences in tourist perceptions of climate change. Current Issues in Tourism (ahead-of-print), 1–17. Retrieved 29 April 2016 from http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.946477

- Hoffarth, M.R., & Hodson, G. (2016). Green on the outside, red on the inside: Perceived environmentalist threat as a factor explaining political polarization of climate change. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 40–49.

- Hollinshead, K. (1994). The unconscious realm of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(2), 387–391.

- Hurworth, R., Clark, E., Martin, J., & Thomsen, S. (2005). The use of photo-interviewing: Three examples from health evaluation and research. Evaluation Journal of Australasia, 4(1/2), 52–62.

- IAATO. (2015). Tourism statistics. Retrieved 29 December 2015 from http://iaato.org/en_GB/tourism-statistics

- Jung, J.M., & Kellaris, J.J. (2004). Cross-national differences in proneness to scarcity effects: The moderating roles of familiarity, uncertainty avoidance, and need for cognitive closure. Psychology and Marketing, 21(9), 739–753.

- Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 76–95.

- Klein, N. (2014). This changes everything: Capitalism vs. the climate. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

- Koll, O., von Wallpach, S., & Kreuzer, M. (2010). Multi-method research on consumer–brand associations: Comparing free associations, storytelling, and collages. Psychology and Marketing, 27(6), 584–602.

- Lemelin, H., Dawson, J., & Stewart, E.J. (2012). Last chance tourism: Adapting tourism opportunities in a changing world. London: Routledge.

- Lemelin, H., Dawson, J., Stewart, E.J., Maher, P., & Lueck, M. (2010). Last-chance tourism: The boom, doom, and gloom of visiting vanishing destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 13(5), 477–493.

- Lorenzoni, I., Nicholson-Cole, S., & Whitmarsh, L. (2007). Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Global Environmental Change, 17(3–4), 445–459.

- Lorenzoni, I., & Pidgeon, N.F. (2006). Public views on climate change: European and USA perspectives. Climatic Change, 77(1–2), 73–95.

- Malone, S., McCabe, S., & Smith, A.P. (2014). The role of hedonism in ethical tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 44, 241–254.

- Mason, M. (2010). Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(3), 8. Retrieved 29 April 2016 from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/viewArticle/1428/3027#g11

- McGregor, S.L.T., & Murnane, J.A. (2010). Paradigm, methodology and method: Intellectual integrity in consumer scholarship. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 34(4), 419–427.

- Miller, G., Rathouse, K., Scarles, C., Holmes, K., & Tribe, J. (2010). Public understanding of sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 627–645.

- Miron, A.M., & Brehm, J.W. (2006). Reactance theory-40 years later. Zeitschrift Für Sozialpsychologie, 37(1), 9–18.

- Murtagh, N., Gatersleben, B., & Uzzell, D. (2012). Self-identity threat and resistance to change: Evidence from regular travel behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(4), 318–326.

- Norgaard, K.M. (2011). Climate denial: Emotion, psychology, culture, and political economy. In J.S. Dryzek, R.B. Norgaard, & D. Schlosberg (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of climate change and society (pp. 399–413). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Phillips, R. (2012). Ethics and network organizations. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(3), 533–543.

- Pienitz, R., Douglas, M.S.V., & Smol, J.P. (Eds.). (2007). Paleolimnological research in polar regions: An introduction. In Long-term environmental change in Arctic and Antarctic lakes (Vol. 8, pp. 1–19). Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Plog, S. (2001). Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity: An update of a Cornell Quarterly classic. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 42(3), 13–24.

- Porr, C.J., Mayan, M., Graffigna, G., Wall, S., & Vieira, E.R. (2011). The evocative power of projective techniques for the elicitation of meaning. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 10(1), 30–41.

- Prillwitz, J., & Barr, S. (2011). Moving towards sustainability? Mobility styles, attitudes and individual travel behaviour. Journal of Transport Geography, 19(6), 1590–1600.

- Reiser, A., & Simmons, D.G. (2005). A quasi-experimental method for testing the effectiveness of ecolabel promotion. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13(6), 590–616.

- Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage.

- Ross, E.L.D., & Iso-Ahola, S.E. (1991). Sightseeing tourists’ motivation and satisfaction. Annals of Tourism Research, 18(2), 226–237.

- Schott, C., Reisinger, A., & Milfont, T.L. (2010). Tourism and climate change. In C. Schott (Ed.), Tourism and the implications of climate change: Issues and actions (Bridging tourism theory and practice) (Vol. 3, pp. 1–24). London: Emerald Group.

- Schwartz, S.H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65..

- Scott, D., Gössling, S., Hall, C.M., & Peeters, P. (2016). Can tourism be part of the decarbonized global economy? The costs and risks of alternate carbon reduction policy pathways. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(1), 52–72.

- Scott, D., Jones, B., & Konopek, J. (2008). Exploring potential visitor response to climate-induced environmental changes in Canada's rocky mountain national parks. Tourism Review International, 12(1), 43–56.

- Sen, S., Gürhan-Canli, Z., & Morwitz, V. (2001). Withholding consumption: A social dilemma perspective on consumer boycotts. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(3), 399–417.

- Shaw, S., & Thomas, C. (2006). Discussion note: Social and cultural dimensions of air travel demand: Hyper-mobility in the UK. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 14(2), 209–215.

- Soley, L., & Smith, A.L. (2008). Projective techniques for social science and business research. New York, NY: Southshore Press.

- Statistics Greenland. (2015). Greenland tourism statistics. Retrieved 29 December 2015 from http://www.tourismstat.gl/

- Statistics Norway. (2014). This is Svalbard 2014. What the figures say. (Official Statistics of Norway No. 5). Norway: Statistics Norway. Retrieved 29 April 2016 from https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/_attachment/213945?_ts=14aca3dea58

- Statistics Norway. (2015). This is Svalbard 2014. What the figures say. (Official statistics of Norway No. 5). Norway: Statistics Norway. Retrieved 26 December 2015 from https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/artikler-og-publikasjoner/this-is-svalbard-2014

- Stoll-Kleemann, S., O'Riordan, T., & Jaeger, C.C. (2001). The psychology of denial concerning climate mitigation measures: Evidence from Swiss focus groups. Global Environmental Change, 11(2), 107–117.

- Szmigin, I., & Carrigan, M. (2005). Exploring the dimensions of ethical consumption. Advances in Consumer Research, 7, 608–613.

- Tang, L.R. (2014). The application of social psychology theories and concepts in hospitality and tourism studies: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 36, 188–196.

- Thøgersen, J. (2005). How may consumer policy empower consumers for sustainable lifestyles? Journal of Consumer Policy, 28(2), 143–177.

- Tyler, T.R., Orwin, R., & Schurer, L. (1982). Defensive denial and high cost prosocial behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 3(4), 267–281.

- Umbreit, A. (2013). Bradt Svalbard: Spitzbergen with Frank Josef Land & Jan Mayen (5th ed.). Chalfont St Peter: Bradt Travel Guides.

- Urry, J. (2002). The tourist gaze. London: Sage.

- VanLange, P., Liebrand, W.B.G., Messick, D., & Wilke, H. (1992). Social dilemmas: The state of the art. In W.B.G. Liebrand (Ed.), Social dilemmas: Theoretical issues and research findings (pp. 3–28). London: Routledge.

- Vitell, S.J., Singhapakdi, A., & Thomas, J. (2001). Consumer ethics: An application and empirical testing of the Hunt-Vitell theory of ethics. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(2), 153–178.

- Weeden, C. (2011). Responsible tourist motivation: How valuable is the Schwartz value survey? Journal of Ecotourism, 10(3), 214–234.

- Whitmarsh, L. (2009). What's in a name? Commonalities and differences in public understanding of ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’. Public Understanding of Science, 18(4), 401–420.

- Willis, A. (2015, November 26). 10 islands you need to see before they sink. Retrieved 17 January 2016 from http://metro.co.uk/2015/11/26/10-islands-you-need-to-see-before-they-sink-5527258/

- World Travel Guide. (2012). Venice travel guide and travel information. Retrieved 13 May 2012 from http://www.worldtravelguide.net/venice

- WWF UK. (2015). Adopt a polar bear. Retrieved 28 December 2015 from http://www.adoptananimal.uk.com/charities/wwf-animal-adoptions/adopt-a-polar-bear/