Abstract

Many developing countries aim at balancing macro-level, growth-oriented economic policies with local community-based development strategies under the auspices of global governance organizations. South Africa adopts such a strategy to be competitive in the global market and, simultaneously, to alleviate domestic socio-spatial inequalities inherited from the apartheid period. Based on a qualitative case study in and around Pilanesberg National Park, this paper assesses whether this seemingly contradictory policy combination elicits the empowerment of traditionally marginalized actors. We use an institutional approach to evaluating sustainable development policy. Results of a policy perception analysis indicate that the substantive aspects of South Africa’s policies are widely acknowledged in the Pilanesberg area. The problem rests with the procedural aspects of how to deal with the shared responsibility of stakeholders with different interests and levels of authority. The paper concludes that power can be meaningfully shifted to community stakeholders only when the investments of global and national-level players are redirected towards establishing a system of procedures to solve local-level disparities in skills and power between the “jointly responsible” actors. These disparities currently result in deadlocks regarding local sustainable development in the Pilanesberg area, despite promising multi-level policies implemented in the post-apartheid era to avoid such situations.

Introduction

Community-based tourism (CBT) and local entrepreneurship are often hailed as sustainable development drivers in the policies of many developing countries. Yet, there are few examples where the full development potential of tourism for local communities is reached. Research has shown that tourism development efforts in developing countries often run into individual, collective and institutional challenges for fostering durable entrepreneurship and community collaboration (Adiyia & Vanneste, Citation2018; Lenao, Citation2015; Manyara & Jones, Citation2007). Without guidance or facilitation by governmental stakeholders, backward linkages between the accommodation sector and local services, such as food provision, are mostly not pro-poor, but target well-established small, medium and micro enterprises (SMMEs) (Pillay & Rogerson, Citation2013). Hence, despite the emphasis of CBT on local ownership and empowerment, national and regional policies should search for synergies between tourism, agriculture and nature conservation, facilitate the incorporation of emplaced socio-cultural dynamics in tourism development practices, spread out tourists in space to avoid the creation of “tourist bubbles”, and improve market access for local tourism enterprises (Adiyia, Stoffelen, Jennes, Vanneste, & Ahebwa, Citation2015; Giampiccoli, Saayman, & Jugmohan, Citation2014; Kirsten & Rogerson, Citation2002; Rogerson, Citation2013).

Establishing such policies is a challenge. In many cases, government policies appear to be weak, too centralized and too bureaucratic in terms of decision-making, or without the instruments to facilitate local skills creation and empowerment (Adiyia et al., Citation2015; Lenao, Citation2015; Saufi, O’Brien, & Wilkins, Citation2014). CBT initiatives run the danger of ending up in a stalemate by depending on top-down guidance in a context of weak institutional support and low private sector engagement. This situation could result in a financial dependency on NGO intervention. Such external funding schemes can become disconnected from local socio-cultural and economic dynamics and may hinder local initiatives to become financially viable in their own right (Manyara & Jones, Citation2007; Stone, Citation2015).

South Africa forms a fascinating case in this regard. As a country struggling with immense inequalities, but with a high tourism potential, especially in the economically-weak rural areas, South Africa has adopted several strategic national policies aimed at tourism-led local economic development (LED) (Nel & Rogerson, Citation2007; Rogerson, Citation2014). The country’s post-apartheid policy on reducing its socio-economic and spatial inequalities focuses on community-based strategies to support local participation, entrepreneurship and black economic empowerment in the largely underdeveloped former Homelands. Since the end of the 1990s, this decentralized strategy has been and still is solidly framed within a neoliberal, macro-economic growth agenda (Bek, Binns, & Nel, Citation2004; Houghton, Citation2011; Rogerson, Citation1997). The combination of neoliberal macro-economic policies and local development strategies oriented towards mopping up the unwanted effects of exactly such overarching policies raises questions as to whether South Africa, fuelled by a post-apartheid sense of urgency, has found a solid approach, or if this approach is structurally inefficient.

The objective of this paper is to evaluate whether South Africa’s specific combination of macro and micro-level tourism-induced development policies is able to elicit the empowerment of traditionally marginalized actors in the local economy. Such a study is also relevant from an international perspective. Macro-economic policies aimed at generating foreign revenue are widely present in developing countries and are supported in global governance by players such as the World Bank that, paradoxically, also emphasise community empowerment (Nyakunu & Rogerson, Citation2014; World Bank, 2013). These policies are often critiqued for being insensitive to local power imbalances and, despite macro-economic growth, for increasing rather than mitigating socio-economic inequalities (Boström, Citation2012). By placing South Africa’s seemingly strongly organized local development policies in this broader context, our study assesses whether macro-economic growth policies can go hand-in-hand with local place-based development in the right policy context.

In line with the paper’s objectives, we aim to answer the following question:

What are the local sustainable development processes resulting from South Africa’s specific combination of macro and micro-level tourism-induced development policies, as perceived by the different actors that are supposed to be collectively responsible for local development?

We use a qualitative enquiry into Pilanesberg National Park (PNP) and its surrounding areas to answer the research question. We combine insights into experienced difficulties for business development, local employment and the establishment of local linkages – in other words, an evaluation of the functioning of the system of community-based tourism and local economic and community development – with a mapping of the perceptions of tourism stakeholders at the midst of the country’s seemingly contradictory development policies.

By doing so, the paper contributes to the discussion on community-based, tourism-induced sustainable development in two ways: (1) through its holistic perspective, which focuses on the institutionalization of development policies instead of focusing on individual policy instruments, and (2) through an assessment of not just the power position of individual stakeholders, but the functioning of the collective system on the local level, as characterized by information exchange and (dis)trust among the different players, who are supposed to be collectively responsible for local development.

Literature review

Institutional approaches to sustainability in community-based tourism

Government involvement is a precondition and a powerful tool for organizing tourism as a transformative development sector (Nyakunu & Rogerson, Citation2014; World Bank, 2013). Often-noted international examples of successful CBT policy, such as the COBRA programme in Kenya and the CAMPFIRE plans in Zimbabwe, have highlighted several success factors. These include the presence of a widespread sensitization among residents of the potential of community-based enterprise development, community empowerment, effective leadership, characterized by common purpose, capacity building and skills creation, and an appropriate national policy framework for catalysing local-level action (Manyara & Jones, Citation2007).

A best-practice national policy framework for community-based tourism and natural resource management is epitomized in the communal area conservancy policy in Namibia. It builds on the systematic devolution of management authority to communities to enable them to achieve the success factors mentioned above. The managing community is required to have a clear membership structure in place, and also physical boundaries, as well as a representative committee, preferably with several sub-committees in order to increase accountability. Additionally, they are required to plan for the equitable distribution of benefits, and have a formal legal structure (Jones & Weaver, Citation2009).

However, while local benefits are significant in many of these well-developed initiatives, studies have shown that they are not necessarily pro-poor or empowering in the long run (Bandyopadhyay, Humavindu, Shyamsundar, & Wang, Citation2009; Saarinen, Citation2010, Citation2011). Research has found that the potential described for these best practices can only be mobilized into action by a policy-regulated partnership between communities, enterprises and non-profit organizations in order to avoid dependency on external donors or support organizations (Lapeyre, Citation2011; Manyara & Jones, Citation2007; Stone, Citation2015). Framed under the label of social sustainability, Murphy (Citation2012) found in a literature review that he conducted of academic and global governance documents, that four general elements should be considered by such policy partnerships: public awareness of the concept “sustainability”, equity (the fair distribution of opportunities and benefits), participation, and social cohesion (social interaction, tolerance and solidarity). The recognition of these domains is relevant beyond the social sphere as the social pillar of sustainability is not just substantive (content-based) but also incorporates procedural aspects as to how sustainability policies should be integrated across the individual sustainability pillars (Boström, Citation2012).

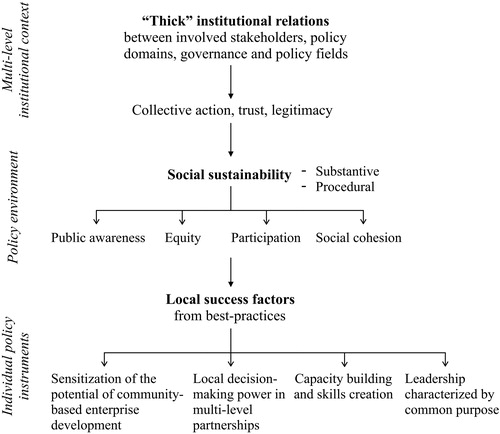

The focus on the procedural elements of sustainability policies shifts the attention from individual policy instruments to the larger system of policy institutionalization. Policy environments are driven by their broader multi-scalar institutional contexts (Nyakunu & Rogerson, Citation2014). Institutional perspectives on regional development place the emphasis on social relations and inter-stakeholder connections, which, when strongly developed, are characterized by “inter-institutional interaction and synergy, collective representation by many bodies, a common industrial purpose, and shared cultural norms and values” (Amin & Thrift, Citation1994, p. 15). “Thick” institutionalization could result in collective action, trust and the established legitimacy of stakeholders as relevant actors in the policy process (Dredge & Jenkins, Citation2003).

Such perspectives on the institutionalization of sustainability policy are particularly useful in the context of tourism. As a sector with a pronounced fragmentation in terms of space, stakeholders, relevant policy domains and sustainability spheres, individual policy instruments should be interpreted as part of their broader institutional framework to capture the underlying processes that influence the results that these instruments may achieve (Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2016). This is particularly the case in developing countries characterized by international value chains, the lack of a spatial co-location of the drivers of the tourism economy and local communities and SMMEs, and the unequal dispersal of decision-making power in these systems. For example, Balint and Mashinya (Citation2006) argue that even for CAMPFIRE in Zimbabwe, a noted best practice in CBT policy, the local participation and empowerment is dependent on continuing interaction between stakeholders with inherently contrasting interests, resulting in a fragile situation, where external overview and policy catalysts are a precondition for sustainable benefits. Lamers, Nthiga, Van der Duim, and van Wijk (Citation2014) found similar results for a community-based conservation tourism project with positive development results in Kenya.

Different concepts and approaches have been put forward to tackle this challenging situation in tourism of finding a balance between stakeholders and impacts in different societal spheres. These include attention to governance typologies (Hall, Citation2011), tourism value chain relations (Adiyia et al., Citation2015; Adiyia & Vanneste, Citation2018; Snyman & Spenceley, Citation2012), local backward linkages (Kirsten & Rogerson, Citation2002) and general relational approaches that incorporate, for example, trade associations and triple helix models of governance (Carlisle, Kunc, Jones, & Tiffin, Citation2013). These academic approaches have in common that they have an open multi-scalar view on tourism and sustainable development policies and focus on the interrelations between stakeholders with different levels of power and interest, policy spheres and spheres of impact. They implicitly refer to the complexity of tourism systems where adaptive, non-linear and continuous policies should be paired with co-management in which the diversity of involved stakeholders, particularly the disempowered ones, is maximized (Jones & Weaver, Citation2009; Plummer & Fennell, Citation2009). While the frameworks for such policies can be set on national levels, previous research has shown that practical application needs to be set locally or regionally, bringing together context-specific issues and overarching strategic policies in functional networks that build on existing community capacities in a process of continuous learning (Manyara & Jones, Citation2007).

Combining institutional views on development with the social sustainability literature shows that one should simultaneously look at the content of sustainability policy and the process through which this policy is mobilized. This entails moving beyond focusing on the structure of cooperation between the actors. Tourism-induced regional development can be structurally hampered, both in cases of organizational “over-mobilization” and in cases of organizational “under-mobilization” (Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2017). The essence is how the policy content is incorporated across policy levels and how it is lived and collectively enacted by the involved actors – in other words how it is congruent (Ochieng, Visseren-Hamakers, & Van der Duim, Citation2017) and institutionalized (Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2016). To mobilize collective action, bridging actors or policy partnerships need to align perceptions, competences and sometimes contrasting interests in an adaptive empowering process that institutionalizes the social sustainability dimensions outlined above (see Murphy, Citation2012). This implies the formulation of policies compatible between macro and micro levels, as well as between different policy spheres, the internalization of these policies by the stakeholders of divergent interest, to sharpen their awareness of the relevant issues, and the local-level enactment of the policies in terms of participation, equity and social cohesion (see ).

Post-apartheid tourism and local development policies in South Africa

South Africa’s balance between macro and micro-level development policies

South Africa inherited massive social, economic, ethnic and spatial inequalities from the apartheid era. These required strenuous efforts from the new ANC government in its quest to establish an inclusive framework for development in the immediate post-apartheid years. The initial Reconstruction and Development Programme, developed in 1994, with an emphasis on poverty alleviation through grassroots initiatives, failed in its quest to alleviate inequalities and to achieve macro-economic stability. Instead of creating a concrete, workable policy, the state lacked the capacity to take up its developmental role, and rather focused on its broad “wish-list” framing (Luiz, Citation2002). In response, the Growth, Employment and Redistribution Framework was initiated in 1996 with the focus being on export and private investments to stabilize the economy (Bek et al., Citation2004; Luiz, Citation2002; Rogerson, Citation2005).

The subsequent opening up of the economy to global economic flows, in combination with an awareness of the need to attend to pressing local development needs, led to the decentralization of both administrative power and responsibility for decision-making (Bek et al., Citation2004; Rogerson, Citation1997, Citation2014). In the context of ineffective traditional top-down planning, South Africa strove for local governments to adopt attitudes that were more entrepreneurially inspired (Rogerson, Citation1997, Citation2014). LED initiatives, supported by international NGOs, marked a shift from government to governance with the objective of increasing the international competitiveness of regions and of reducing socio-economic inequalities through the (assumed) trickle-down effect of economic benefits (Houghton, Citation2011; Nel & Rogerson, Citation2007).

Simultaneously, the traditional industrial focus, particularly important during the apartheid era, when the Homelands were used as sources for cheap labour (Nel, Citation1994), made room for a more flexible specialization to link up to post-Fordist, globalizing economies (Rogerson, Citation1997). Place-based sectors, such as tourism, took on an important role in local development (Rogerson, Citation2014). Furthermore, since the early 2000s, black economic empowerment (BEE) certificates, a state-supported scheme to increase the participation of the black community in economic life through employment, ownership and entrepreneurship, became top priorities of the government (Iheduru, Citation2004). BEE policies have led to a growing black middle class, yet they are also critiqued for the anti-democratic preferential treatment of ethnic groups and for increasing the inequality within black communities. For this reason, the BEE scheme changed into a “broad-based black economic empowerment” (BBBEE) campaign to work towards more equal empowerment, also within the ethnic communities (Iheduru, Citation2004). In addition, the 2009 New Growth Path and the 2012 National Development Plan increased the developmental role of the state by stimulating SMME start-ups with business incubators to boost job creation (Rogerson, Citation2014).

Despite these national policies that try to achieve a balance between global economic connections and local pro-poor effects through entrepreneurial stimulation, Bek et al. (Citation2004, p. 37) argue that “something has been lost in the translation of the wording of these and other programmes when it comes to actual delivery on the ground”. Several authors (e.g. Bek et al., Citation2004; Houghton, Citation2011) blame the retreating state as part of neoliberal politics of scale and weak local administrative capacities. Additionally, overregulation and bureaucracy are noted as market-entry barriers for emerging SMMEs (Pillay & Rogerson, Citation2013; Rogerson, Citation2005). Despite government efforts, informal operators and family and friends are often still important suppliers of start-up capital in South Africa (Rogerson, Citation2008).

LED policy and tourism entrepreneurship: a South African success story?

Despite the critique on LED implementation, the post-apartheid CBT policy of South Africa has become an example for other developing countries (Pillay & Rogerson, Citation2013). Responsible tourism, where the tourism industry, government and communities take responsibility for the sustainable use of environmental resources, the involvement of local communities and cultures, and protect them from overexploitation, has become the guiding principle of tourism development since the publishing of the 1996 White Paper on the development and promotion of tourism in South Africa (Government of South Africa, Citation1996).

In the early 2000s, the qualitative transformation of the tourism economy through skills training, infrastructural development and increased black ownership was added as a national policy focus (Rogerson, Citation2005). The national rural tourism strategy of 2012 was installed to further foster an integrative rural tourism economy in identified priority district municipalities, mostly in the former Homelands (Rogerson, Citation2015). Even though studies on the implementation of these tourism policies show mixed results (Giampiccoli et al., Citation2014; Lyon, Hunter-Jones, & Warnaby, Citation2017), “many of the most successful small towns and rural areas […] have been driven by tourism-led development” (Rogerson, Citation2014, p. 213).

Noted success factors in best-practice areas are strong local leadership that catalyses collective local action in a partnership approach, a clear vision, private sector engagement and a supportive local policy framework (Nel & Binns, Citation2002). The 2011 National Tourism Sector Strategy actively encourages local governments to engage in tourism planning for development and attempts to strengthen their capacity to do so (Rogerson, Citation2013). Governmental empowerment initiatives have also stimulated large tourism enterprises to establish SMME support structures. As a result, “many, if not most, of these business linkages would not have existed without government policy requirements” (Kirsten & Rogerson, Citation2002, p. 40).

Pilanesberg National Park

Study area

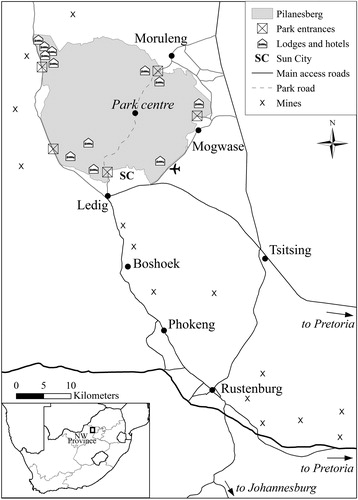

The area around Pilanesberg National Park () in North West Province is located in the former Bophuthatswana Homeland. PNP was redesigned from a pastoral farmland to become a protected natural area in the 1970s. The land belonging to the local Bakgatla, Bakubung and Bafokeng communities was expropriated. The Bakgatla settled mainly around Moruleng, the Bakubung live in the Ledig area, and the Bafokeng tribal office is located in Phokeng (). Land restitution processes have been ongoing since the end of the apartheid era but have still not been finalized.

Figure 2. Spatial situation of the PNP area. The location of the lodges is according to PNP (Citation2019). Own mapping.

The national park, which opened as a nature reserve in 1977, aimed to include the neighbouring communities in decision-making, to share revenues and to boost employment with nature-based tourism centring on the “Big Five” that were reintroduced to the park. It was developed in combination with Sun City, a luxury casino resort, which opened in 1979 (Carruthers, Citation2011). In the 1980s, high-end lodges were established at the park’s edge. The lodges operate on long-term concessions from the provincial North West Parks Board. The park’s planning arrangement prevented resort development within the park (Carruthers, Citation2011).

Since the beginning of the 2000s, local guesthouses have mushroomed in the park’s surroundings, clustering in the southern and eastern corridor between Boshoek, Ledig and Mogwase, around the public gates of the park. While tourism businesses in the Boshoek/Ledig area are mostly owned by white entrepreneurs, as is generally the case in South Africa (Republic of South Africa, Citation2011), almost all of the guesthouses in Mogwase are black-owned. The north-western side of the park is the driest part of the area, with more pastoral land and habitations even more spread out than those in the south and east.

Platinum and other ore mines, which, together with tourism, form the economic drivers of the area (North West Planning Commission, Citation2013a), are clustered in the southern corridor, extending from Rustenburg to Ledig, and continue along this western, relatively undeveloped boundary of the park (). Currently, the park is a nature-based tourism destination of medium intensity for South African standards. Combined with Sun City, it attracts both international tourists and weekend visitors on account of its accessibility to the residents of Pretoria and Johannesburg and the regional airport (Kgote & Kotze, Citation2013).

Methodology

Considering the economic transformation fuelled by the high-end resorts at the park’s edge and the locally-owned tourism businesses in the park’s surroundings, PNP provides a fascinating area for assessing the (perceived) role of South Africa’s policy for tourism-induced local economic and community development. Since we were predominantly interested in the perceptions of stakeholders involved in South Africa’s responsible tourism policy, we organized a qualitative enquiry, built on semi-structured interviews. We contacted actors in the public, private and community development spheres that were operating on different levels in order to compare the visions of stakeholders in different positions of power.

In total, we conducted 46 semi-structured interviews in July and August, 2015. The interviewees included two local business development catalysts and 25 local entrepreneurs including guesthouse owners, local tour operators, handicraft salesmen and food providers. These respondents were identified on the basis of detailed and continuous on-site explorations into entrepreneurial activity in the settlements surrounding PNP. This exercise was followed by canvassing these places and supplementing them with the results of snowball sampling. This allowed us to identify other potential respondents in the interviewed company’s supply chain. In this way, we were able to cover the majority of local tourism-related businesses and support organizations in the area. Data saturation was apparent during the final interviews.

Interviews were also conducted with 16 representatives from high-end resorts and three government officials on the local and regional level. We used purposive sampling, on the basis of desktop research into policy documents and applied research reports, to identify and contact the relevant stakeholders in the area’s tourism governance system. We reached almost full coverage of these stakeholders.

The interviews lasted from eight to 80 minutes, with an average time period of 36 minutes per interview. Discussed topics covered general sector and area-specific characteristics, the personal experiences of the respondents in terms of tourism in the area, business development strategies and challenges, and experiences with policies and cooperation. The literature review on CBT and South Africa’s tourism-focused LED policies constituted the inputs for the interview protocols. A short follow-up visit took place in the spring of 2018 during which observations to check the validity of the preliminary results were made. An additional seven informal interviews were conducted with four resort and hotel employees and three local entrepreneurs. These respondents, who had not been contacted in the first data collection phase, were selected on the basis of on-site convenience sampling. The interviews dealt with the same topics as in the first interview phase. The preliminary results, which were obtained using the thematic analysis method described below, were used by the interviewer to phrase secondary questions. These questions served the purpose of evaluating whether the respondents confirmed the preliminary results and whether they were able to enrich the results with additional anecdotal information. These insights were used in the data triangulation phase of the post-coding process discussed below.

After transcription, the data were thematically analysed with NVivo™ software. We followed the data analysis scheme of Stoffelen (Citation2019), who composed and critically discussed a coding/post-coding scheme for interview transcripts and policy documents in tourism research. The scheme departs from the descriptive coding of the interview transcripts and policy documents. Text excerpts were individually and non-comparatively assigned initial topic labels, that were defined only on the basis of the content of the selected text. In a subsequent step, the resulting list of topic labels was aggregated in a pattern coding scheme to provide an overview of the main themes emerging from the transcripts. This pattern coding scheme was compared to a provisional coding scheme that consisted of predefined codes on the basis of the literature review in the South African CBT context. Thus, it was possible to provide a systematic comparison between the “bottom-up” empirical content and the “top-down” theoretical input (Stoffelen, Citation2018). The comparison resulted in a “hierarchical” coding scheme in which first-order observations were interlinked with second-order concepts and more overarching aggregate dimensions and themes (see ).

Table 1. The two highest levels of the hierarchical coding scheme.

All interviews were coded again on the basis of this hierarchical coding scheme. For the post-coding process, we composed a summarized content analysis document with short summaries that had been made for each node in the hierarchical coding scheme. The addition of supplementary information from policy documents and notes from the second data collection phase triangulated the data.

Analysis of the summarizing document resulted in the main findings presented below. The structure of the results section is in tandem with the identified overarching aggregate dimensions and themes summarized in . The first three aggregate dimensions provided mainly descriptive information. The content of these dimensions was used to provide context in the results section. The last three aggregate dimensions, which provided the main results on the functioning and perceptions of South Africa’s tourism-induced local development policy, added structure to the results section. Supportive quotes were selected from the hierarchically coded data on the basis of their illustrative value for the identified results.

Results

Local tourism entrepreneurship in the Pilanesberg area

The rapid emergence of locally-owned tourism businesses in the 2000s, on the back of the success of PNP, its lodges, and Sun City, has resulted in strong competition between the SMMEs in Mogwase and the Boshoek/Ledig area. In Mogwase, the guesthouses are busy in the summer months but struggle to attract tourists during winter. In the Boshoek/Ledig area, the dependency on tourism is less on account of a more balanced economy, with mining activities in particular providing for an off-season and midweek alternative:

People around here have seen that the guesthouses are working [as a livelihood option], especially during the holidays when Sun City and Pilanesberg are full. … That’s why everybody around is turning their house into a guesthouse. By doing so, it’s going to cripple us. (Guesthouse operator, Mogwase)

We’re not relying just on tourism. … There are a lot of mines opening with [related] specialized services and all those people need accommodation. … Out of season, it helps a lot because we’re very quiet in the winter (Guesthouse operator, Ledig/Boshoek).

Because PNP is accessible from Johannesburg and Pretoria, tourism received a short-term boost during the 2010 FIFA World Cup with the establishment of new accommodations and the renovation of the Royal Bafokeng stadium in Phokeng. However, recent years have seen a slow decline in arrivals (North West Parks & Tourism Board, 2015), for which there is no clear explanation, but which may be connected to the lower number of visitors to Sun City. The 2015 South African Tourism Review shows that visitor numbers for the combined national parks of South Africa increased during this period, reflecting that PNP lost share in the tourism market (SA Tourism Review Committee, Citation2015). The strong competition, partly on account of over-investment in accommodations for the FIFA World Cup, the seasonality, and the spatially uneven impacts with the park’s surroundings on the western and northern margins almost totally missing out, make it difficult to sustain local livelihoods from tourism around the year and for the whole area. Nevertheless, interviewed local entrepreneurs and policymakers were moderately positive about the sector’s growth potential, also relative to the mining industry. The latter is currently the dominant regional economic driver, with greater employment opportunities and higher wages than those offered in the tourism sector, but has a limited lifespan.

The interviewees identified challenges for local business development very much like those noted in the current literature. Apart from establishing market access (see below), difficult access to finances and start-up capital was noted by the SMMEs as the main growth inhibitor. All interviewed SMMEs relied fully or predominantly on their own savings or asked their family for financial help. There was a general feeling among interviewees that it is hard to access loans, especially from the banks, which ask for collateral in order to increase the accountability of the local entrepreneurs:

Luckily, I was assisted by my family, so I didn’t have the normal barriers you would have of getting money from the bank, because that’d be the biggest issue. (Guesthouse operator, Boshoek/Ledig)

Regional policymakers, NGOs and the larger economic players identified a relatively weak local entrepreneurial attitude and skills. Respondents noted that, as a legacy of apartheid, previously disempowered stakeholders are often not used to being part of the decision-making process or to taking responsibility for the future of their own businesses.

This situation results in rather limited entrepreneurial activity. Existing businesses were often noted to be underprepared when attempting to attract tourists, applying for loans or engaging in procurement contracts with the lodges. A paucity of market knowledge and a lack of strategic decision-making prowess result in many overambitious projects and unrealistic expectations of quick returns, with large failure rates as a consequence. Interviewees noted the remaining need for external guidance and training to bridge the gap between the actual and the required business skills, mentality and commercial viability of the local entrepreneurs:

We’ve got a tourism incentive programme where we assist with grading, marketing and whatever. The unfortunate part is that when people hear about these things, they come empty-handed (unprepared). … The entrepreneurial attitude is still lacking. That I can assure you. (Regional policymaker A)

A lot of the people around the area have skills. They are builders, welders, and they own their own little businesses. They do have that sense of wanting to do it themselves. The one thing they lack is the business etiquette. You may find that they have skills, but they don’t know how to run their businesses. (Manager, Resort A)

These barriers to local business development are almost identical to the challenges already identified in the 1996 White Paper (Government of South Africa, Citation1996). Even though most interviewees noted that business activities have improved since 1996, this result shows that twenty years of policies have not fully eradicated the post-apartheid challenges for local entrepreneurship in tourism. Put differently, post-apartheid policies were expected to speed up and streamline local development through tourism. Yet, there is no evidence in the Pilanesberg area that these policies have succeeded in preparing local stakeholders for the intricacies of operating local tourism businesses.

Local linkages among stakeholders and entrepreneurs

Local employment and labour linkages

The main drivers of the Pilanesberg area’s tourism economy are the resorts at the park’s edge that offer on average 100 to 400 beds per establishment. These accommodations are owned by hotel and resort groups. The local community benefits from the large employment numbers, as required by the lodges’ operating concession. The large pool of local labour results from the limited economic opportunities in the area apart from mining. Consequently, the resorts are strongly embedded in the community:

Here, you’re very close to the communities. … What happens out there in the community, happens in my place. What happens here, happens in the community. (General Manager, Resort B)

However, most jobs are in non-skilled positions, and with poor terms of employment. While all lodges offer in-house training programmes, the managerial personnel are mostly recruited from outside the region. This is on account of the limited availability of an experienced workforce. Lodge managers noted in their interviews that even though they prefer to hire locally, skills should come first when recruiting people. The same comment was prevalent regarding the BBBEE policy. The lodges noted that they experience a difficult balance between their obvious responsibility to the community and their main focus on business performance:

[The BBBEE] is a good approach for bringing the previously disadvantaged group into participation [to the benefit] of the whole [economy]. But if you’re running a business like in my case … you find yourself in a catch-22 situation. Do you look for the skill or do you look to be compliant? (General Manager, Resort C)

Corporate social investments were seen by the lodges as a way in which to show that, despite the low wage levels, they do care about the community. These actions were fuelled by a sense of moral justice, but also by an economic rationale, with ideas that these social investments could create sentiments of loyalty and commitment among the workforce:

If they believe that I do understand their background, that I really care about them as human beings, not because they are working for us, then they will give 101%. (General Manager, Resort A)

Local entrepreneurs and intermediaries supported the idea behind the BBBEE policy for similar reasons. However, many negative perceptions came to light: either owing to misinformation on what is required from them in the BBBEE system, or owing to the bureaucracy that is perceived to not deliver tangibles:

We need to be empowered; we need to get to a certain level of participation, and the economy of the country needs to be balanced. … In my opinion, BBBEE is necessary and we just need to make sure that we do it. (Local agricultural intermediary)

I don’t see it working. To me, it’s just a requirement. (Guesthouse operator, Mogwase)

When you make an application for a tender, you’re gonna need all the documents: BBBEE, tax clearance, everything. (Local transportation provider)

Local business linkages in procurement and outsourcing

Alongside the spatial separation between the SMMEs at the park’s perimeter and the lodges within the park, PNP is characterized by a large gap between the higher and lower ends of the market. The lodges cater for a high-end public, with an average price of roughly R2500 (±200 US Dollars) per room per night and often more. Local guest houses charge on average R300 to R500 (±25–40 US Dollars) per room per night. The accommodation portfolio misses the middle range, meaning that, in cases of overbooking, guests are not transferred from the lodges to local guesthouses.

A similar mismatch is evident between the quality of the service as required by the lodges and as available in the park’s surroundings. Since outsourcing and procurement are predominantly financially-driven, the balance between the quality and cost of the provided service is crucial for the high-end resorts. Interviewed lodge managers noted that they have fixed contracts and enduring business relations with companies which they know can deliver the required quality of service. These companies are almost without exception located in Johannesburg, Pretoria and to a lesser extent, Rustenburg.

The scale of the operations is a second stumbling block. Local suppliers often cannot keep up with the volume of products required. Finally, local produce is often more expensive owing to limited economies of scale and the lack in awareness of the local entrepreneurs of the prevailing market prices. For these reasons, even local guesthouses predominantly buy directly from supermarkets or from the national market in Johannesburg. Consequently, local procurement and outsourcing primarily take place on an irregular basis, on a small scale, or as a back-up option when something goes wrong with the delivery from Johannesburg:

We paid a consultant’s fee; we went all over the North West; we went to the chicken farms; we went everywhere. But it was still difficult because of quality. (General Manager, Resort B)

[Local entrepreneurs] come to you and say “we want the business, we want the business”. The problem is: they don’t realize the volume that we actually need. … There was a woman who said: “I can make sure you have spinach all the time”. Well, that lasted about three weeks. (General Manager, Resort D)

We’ve ordered uniforms from them (a local business) over a period of three weeks. That we can deal with because it’s a once-off demand and they deliver and that’s it. (General Manager, Resort C)

While there is a governmental Social and Labour Plan to force large companies to invest in local agricultural businesses, the interviewees complained about poor compliance and a feeling of tokenism as major orders still go to non-local wholesalers. Small farmers and guesthouse operators are dependent on interest groups to connect them to larger players and to coordinate the required training and quality upgrades to bridge the gap between the lower and higher ends of the tourism market.

However, the interviews showed that tourism associations are limited in number and scale and are clouded by their lack of transparency and through perceptions of nepotism. Most interviewees were consciously not members of the associations despite membership being a prerequisite for accessing governmental training and loans. Consequently, the local entrepreneurial environment is rather deregulated, with cooperation between the SMMEs taking place mostly on informal terms:

I feel that there are a lot of disadvantages being in an association … It’s not transparent. I asked them: “Why don’t you have a central office where we know you’ve got people employed? Where we can have access, where we can go at any time, where we’re copied in all the e-mails that come in? They couldn’t answer that. (Guesthouse operator, Mogwase)

There’s another company working that side (with a lodge). … We give each other a chance to grow. If he’s fully booked, he will call me and say “Come and help me’, and when I’m fully booked, I say “Come and help me”. We help each other. (Local transportation provider)

As major landowners, the three tribal offices in the area co-own some of the lodges, own some of the mine shafts, and some even have their own development institutions. However, the interviews revealed that their involvement is interpreted by local stakeholders and policymakers as mixed. Since the administration of these authorities is organized along traditional lines of leadership that are not bound by external (e.g. governmental) supervision, they are sensitive to mismanagement by individuals in positions of power (North West Planning Commission, Citation2013b). Interviewees had positive perceptions of two tribal administrations but were less positive about the third. Several interviewees mentioned a locally notorious case where millions of Rands in mining concessions disappeared, resulting in local unrest close to the park’s entrance.

Lodge interviewees all indicated that they actively search for useful businesses and individuals in their surroundings. They do this mainly with the help of intermediaries such as well-connected employees or business development NGOs. In the Pilanesberg area, Black Umbrellas is the main NGO with training programmes for promising local entrepreneurs. An example of a private sector entrepreneurial catalyst is Greenbuds, a locally-owned vegetable wholesaler and agricultural business incubator, which combines market logic with community development actions. Greenbuds buys produce from local farmers at fixed prices, irrespective of market fluctuations. It collects and processes the products, combines these with foodstuffs from the national market and sells the products under a fixed contract to mining companies and lodges. By doing so, the company provides a critical mass of supply and quality control, which are needed to access the higher end of the market. However, like Black Umbrellas, Greenbuds remains an exception, and its scale of operations remains small as it manages to source only about 20 percent of the produce from the local SMMEs.

Institutionalization of LED policies

South Africa’s tourism policies centre on local procurement, on involving communities in decision-making and on improving access to finances and training (Republic of South Africa, Citation2011; SA Tourism Review Committee, Citation2015). Despite a clear overall vision, the interviews indicated that policymakers struggle to break down the national and regional plans into implementation strategies. In the interviews, the regional policymakers and SMMEs described numerous individual projects and support schemes but no one was able to provide a clear overview of the prevailing operations. LED policy in the Pilanesberg area is characterized by a scattershot approach, where several actions are present but there is no strategic coordination to implement policies locally:

How do you break down that message from the president to affect the people on the street, at the lower level? … There isn’t coordination; there isn’t a strategy that gets filtered down. (Local agricultural intermediary)

Government plans focus on local associations and NGOs to disseminate this information, with, for example, the PNP management plan stating that it prefers to work through the existing regional or tribal structures (North West Parks & Tourism Board, 2015). However, earlier results indicated that associations and local interest groups are ineffective in the Pilanesberg area.

Moreover, government officials noted that weak intergovernmental cooperation hampers the translation of these policies to the local level. In Pilanesberg and its neighbouring areas, this is most explicit in the ambiguous relationship between mining and tourism development (North West Planning Commission, Citation2013a). Even though mining is the area’s main economic driver, the noise and light pollution, as well as the presence of dust and debris along the western corridor of the park, conflict with high-end tourism activities. This situation requires integrative policies but these are currently still open for discussion, as indicated by the following quotes:

The government operates in silos. … There’s no integration. It looks like there’s nobody who [sees] what the left hand does and what the right hand does. So, some of their interventions don’t have [a] sustainable impact. (Local agricultural intermediary)

Remember, we … cannot stand up on the top of the table and say: “Stop mining because you’re impacting negatively on tourism.” Because we need to remember that [the] Department of Mineral Resources has entered into agreements with the mines. It’s quite a delicate balance. (Regional policymaker B)

Interviewees disagreed on who is responsible for implementing the policies. Theoretically, the accountability is shared by the public sector, the private sector and community stakeholders since the concept of responsible tourism was put forward as the guiding principle to the country’s tourism development in the White Paper of 1996 (Government of South Africa, Citation1996). In practice, everybody agrees that they have a role to play but that they do not hold the final responsibility. During the interviews, the resort managers felt that they should engage with the community, both from a business perspective and from an ethical point of view. However, they need to be profitable, otherwise they would not be in business and there would be no local employment either. All they can and should do is to complement their business activities by employing the local community members and focus on socially-minded actions:

Who’s the sole custodian of the needs of the community? The government. That goes without saying. … We have a responsibility. It does not mean that we’re the custodians of your wellbeing. We’re not. We have a social responsibility. It’s something entirely different. (Manager, Resort A)

Even though the government is actively involved in community and business development, as described above, some government officials feel that the responsibility lies with the communities, who need to group themselves into associations to become accountable and have a common goal for the future. Others feel that they are responsible for providing a facilitative framework, but indicate that this framework is in place, for example with the BBBEE act:

You need strong collaborations among the community [members]. They must thrust themselves into a cooperative; they must engage all the community members … It should be a strong community initiative. (Regional policymaker B)

I think that, as the government, we have to be responsible as well. … But there’s a law in South Africa, the BBBEE act, which, I think, some of our private sector players are flaunting. It’s a very serious concern for us. Because at times, when we would want to go full force (enforce this policy strictly), you might end up closing shop. (Regional policymaker A)

These contrasting visions create a stalemate that impedes the progress made in terms of the LED policies that are already characterized by implementation difficulties.

Discussion

The study in and around Pilanesberg uncovers structural issues in the institutionalization of South Africa’s specific combination of macro and micro-level policies pertaining to sustainable development. An institutional perspective on social sustainability policies highlights the fact that attention should be paid to the internalization of policies in the awareness of fragmented stakeholders with divergent interests, and the enactment of such policies on the local level in terms of social cohesion, participation and equity (see Murphy, Citation2012).

In terms of awareness of sustainability issues, it is remarkable how the general rationale behind South Africa’s national policies has permeated down to lower administrative levels and to the representatives of the tourism industry in the Pilanesberg area. There is widespread recognition throughout the PNP area of the need to improve the power position of communities and the joint responsibility of the government, private sector, and communities in achieving this. One exception is the practical evaluation of individual policies such as the BBBEE and the local procurement regulations. These are seen by some as an administrative burden and in an economic sense, irrational. This finding provides evidence for the scientific value of interpreting individual instruments, not in isolation, but as part of their broader institutional environment.

In terms of social cohesion, the results show that intra-group contact and exchange is strong and is particularly expressed in the form of informal ties. Conversely, the between-group stakeholder exchange is more formal and, consequently, also more tense. It is guided by an economic rationale instead of a sense of common purpose and collective action. Despite strong informal ties, community stakeholders and local entrepreneurs have not succeeded in formalizing their cooperation to form a critical mass to participate collectively. Their limited systematic, collective involvement undermines the establishment of an inclusive and continuous co-management regime in the area (Plummer & Fennell, Citation2009). The combined situation in the social sustainability domains has resulted in a clear economic disconnection between the high-end lodges and the SMMEs, thus limiting spatially- and socially-inclusive development that could be achieved through tourism, thereby undermining the equity of the current practices.

Put differently, the substantive aspects of South Africa’s sustainable development policy are widely acknowledged in the Pilanesberg area. The problem rests with the procedural aspects, particularly on the local level in terms of how to mobilize actors and deal with the shared responsibility of stakeholders with different interests and served by different national policies (Boström, Citation2012).

Results show that even a policy framework that is strong on paper is inclined to bring with it difficulties in coping with the above-mentioned issue. The responsible tourism mantra, with the shared responsibility between government, tourism operators and community stakeholders and entrepreneurs, seems an elegant way to bridge the gap between seemingly contradictory macro-economic growth policies and local community-based development strategies. However, results indicate that because of the feeling of shared responsibility, no one has taken on the final responsibility, and the actions of other stakeholders are perceived as substandard or inefficient. Consequently, national policies do not result in a constructive middle ground for stakeholders.

National and regional policies that attempt to counteract this stalemate by operating through partnerships and associations are useful on paper as they follow the call from several researchers that public-private arrangements are needed to facilitate CBT (Adiyia et al., Citation2015; Dodds, Ali, & Galaski, Citation2018; Manyara & Jones, Citation2007). However, these plans do not consider that on the local level in and around Pilanesberg these associations are clouded by perceptions of limited returns, nepotism and inefficiency. There are no bridging actors in place to align the perceptions, actions and authority of the stakeholders operating in the system that is characterized by structural local-level institutional under-mobilization (Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2017). As such, South Africa’s combination of policies currently does not allow the country to deal with structural inequalities in the tourism economy. Even though individual policy instruments and decisions may contribute to the effective functioning of the country’s policies, there are systemic problems in how these policies are institutionalized among stakeholders that should collectively negotiate these into a workable practice.

Conclusion

This paper assesses the local sustainable development processes fostered by South Africa’s specific combination of neoliberal, growth-oriented, macro-level policies and micro-level community-based tourism-induced development strategies. We combined insights into the functioning of the current system of community-based tourism and local economic and community development with a study of the institutionalization of sustainable development policies at the grassroots level. The study found that despite the national policies that provide a solid rationale, there is an implementation gap (Stoffelen & Vanneste, Citation2016) in their enactment as a driver for social sustainability on local levels in PNP.

Almost unanimously, the stakeholders in and around Pilanesberg have shown that they perceive the substantive aspects of South Africa’s sustainable development policy as positive. The problem rests with the procedural aspects as to how to get this policy mobilized in practice. The resultant stalemate in transformative actions has resulted in the absence of a solid CBT strategy in operation at the local level, no signs of it being implemented, and limited concrete evidence of local sustainable development processes emanating from the government’s policies.

The study’s findings are interesting in areas beyond the South African context. The case study indicates that there are missing elements for making the combination of macro-level, growth-oriented strategies and local community-based development policies work at the grassroots level. The situation identified in and around PNP raises questions as to whether, if at all, high-end nature-based tourism in rural areas could have a significant empowering effect on local communities, even in cases where the national and provincial policies are well-informed.

The results of this research provide indications to the effect that global governance strategies, for example by the World Bank, are at odds with the aims of the large-scale shifting of power to marginalized stakeholders in the tourism economy of the Global South. Systemic change is needed in order to be able to make significant inroads. Individual policy instruments drafted at the national level do provide a first step towards achieving LED. However, the emphasis, also of global governance support aiming to uncover the tourism sector’s transformative development effect, should be on the institutionalization of social sustainability domains in the overall tourism policy system, hence, among stakeholders with differently scaled operations and power positions. To this end, the sector’s pro-growth paradigm should be challenged by global players such as the World Bank.

The fundamental mismatches in the interests and the power of stakeholders cannot be expected to be solved at the local level where the disparities in skills, capacity and (financial) power between “jointly responsible” actors are the largest and most tangible. A system of procedures coordinated among global organizations, national and regional policymakers, and tourism enterprises is needed to put the interests of local stakeholders first. Only then, and with regional policies in place that catalyse the collective representation of local actors, can the power be meaningfully shifted to the stakeholders in the communities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arie Stoffelen

Dr. Arie Stoffelen ([email protected]) is an assistant professor at the University of Groningen (Netherlands). He is also coordinator of the Master Cultural Geography and the Tourism Geography and Planning track at that university. His research interests centre on tourism-induced regional development and tourism landscape creation, including geotourism development. He studies the role of tourism in cross-border cooperation processes, mainly in European contexts, as well as tourism livelihood creations in the Global South.

Bright Adiyia

Dr. Bright Adiyia is a municipal sustainability officer in Belgium as well as a research collaborator at the Division of Geography and Tourism at the University of Leuven (KU Leuven, Belgium). His main research interest is sustainable development, tourism and poverty alleviation, and livelihood perspectives in the Global South.

Dominique Vanneste

Dr. Dominique Vanneste is a full professor at the Division of Geography and Tourism at the University of Leuven (KU Leuven, Belgium). Her research focuses on regional and destination development and (cultural) heritage with an emphasis on identity building and preservation. She works on tourism networks and the role of brokers, as well as on heritage tourism as a lever for development. Further, she studies the relationship between war heritage and tourism from a memoryscape perspective.

Nico Kotze

Dr. Nico Kotze is an associate professor at the Department of Geography at the University of South Africa (UNISA). His main research interests deal with South African housing issues and urban redevelopment questions in the country.

References

- Adiyia, B., Stoffelen, A., Jennes, B., Vanneste, D., & Ahebwa, W. M. (2015). Analysing governance in tourism value chains to reshape the tourist bubble in developing countries: The case of cultural tourism in Uganda. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2–3), 113–129. doi:10.1080/14724049.2015.1027211

- Adiyia, B., & Vanneste, D. (2018). Local tourism value chain linkages as pro-poor tools for regional development in western Uganda. Development Southern Africa, 35(2), 210–224. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2018.1428529

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (1994). Living in the global. In A. Amin and N. Thrift (Eds.), Globalization, institutions, and regional development in Europe (pp. 1–22). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Balint, P. J., & Mashinya, J. (2006). The decline of a model community-based conservation project: Governance, capacity and devolution in Mahenye, Zimbabwe. Geoforum, 37(5), 805–815. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2005.01.011

- Bandyopadhyay, S., Humavindu, M., Shyamsundar, P., & Wang, L. (2009). Benefits to local communities from community conservancies in Namibia: An assessment. Development Southern Africa, 26(5), 733–754. doi:10.1080/03768350903303324

- Bek, D., Binns, T., & Nel, E. (2004). Catching the development train’: Perspectives on ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ development in post-apartheid South Africa. Progress in Development Studies, 4(1), 22–46. doi:10.1191/1464993404ps047oa

- Boström, M. (2012). A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 8(1), 3–14. doi:10.1080/15487733.2012.11908080

- Carlisle, S., Kunc, M., Jones, E., & Tiffin, S. (2013). Supporting innovation for tourism development through multi-stakeholder approaches: Experiences from Africa. Tourism Management, 35, 59–69. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.05.010

- Carruthers, J. (2011). Pilanesberg National Park, North West Province, South Africa: Uniting economic development with ecological design—A history, 1960s to 1984. Koedoe, 53(1), 1–10. doi:10.4102/koedoe.v53i1.1028

- Dodds, R., Ali, A., & Galaski, K. (2018). Mobilizing knowledge: Determining key elements for success and pitfalls in developing community-based tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(13), 1547–1568. doi:10.1080/13683500.2016.1150257

- Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (2003). Destination place identity and regional tourism policy. Tourism Geographies, 5(4), 383–407. doi:10.1080/1461668032000129137

- Giampiccoli, A., Saayman, M., & Jugmohan, S. (2014). Developing community-based tourism in South Africa: Addressing the missing link. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation & Dance, 20(September), 1139–1161.

- Government of South Africa. (1996). White paper on the development and promotion of tourism in South Africa. Cape Town, Pretoria. Retrieved from http://scnc.ukzn.ac.za/doc/tourism/White_Paper.htm.

- Hall, C. M. (2011). A typology of governance and its implications for tourism policy analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 437–457. doi:10.1080/09669582.2011.570346

- Houghton, J. (2011). Negotiating the global and the local: Evaluating development through public-private partnerships in Durban, South Africa. Urban Forum, 22(1), 75–93. doi:10.1007/s12132-010-9106-5

- Iheduru, O. C. (2004). Black economic power and nation-building in post-apartheid South Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 42(1), 1–30. doi:10.1017/S0022278X03004452

- Jones, B., & Weaver, L. C. (2009). CBNRM in Namibia: Growth, trends, lessons and constraints. In H. Suich, B. Child, and A. Spencely (Eds.), Evolution & innovation in wildlife conservation. Parks and game ranches to transfrontier conservation areas (pp. 223–242). London: Earthscan.

- Kgote, T., & Kotze, N. (2013). Visitors perceptions and attitudes towards the tourism product offered by Pilanesberg National Park, South Africa. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation & Dance, 19(Sup. 2), 323–335.

- Kirsten, M., & Rogerson, C. M. (2002). Tourism, business linkages and small enterprise development in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 19(1), 29–59. http://doi.org/10.1080/0376835022012388 doi:10.1080/03768350220123882

- Lamers, M., Nthiga, R., Van der Duim, R., & van Wijk, J. (2014). Tourism-conservation enterprises as a land-use strategy in Kenya. Tourism Geographies, 16(3), 474–489. doi:10.1080/14616688.2013.806583

- Lapeyre, R. (2011). The Grootberg lodge partnership in Namibia: Towards poverty alleviation and empowerment for long-term sustainability? Current Issues in Tourism, 14(3), 221–234. doi:10.1080/13683500.2011.555521

- Lenao, M. (2015). Challenges facing community-based cultural tourism development at Lekhubu Island, Botswana: A comparative analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 18(6), 579–594. doi:10.1080/13683500.2013.827158

- Luiz, J. M. (2002). South African state capacity and post-apartheid economic reconstruction. International Journal of Social Economics, 29(8), 594–614. doi:10.1108/03068290210434170

- Lyon, A., Hunter-Jones, P., & Warnaby, G. (2017). Are we any closer to sustainable development? Listening to active stakeholder discourses of tourism development in the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve, South Africa. Tourism Management, 61, 234–247. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.010

- Manyara, G., & Jones, E. (2007). Community-based tourism enterprises development in Kenya: An exploration of their potential as avenues of poverty reduction. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 628–644. doi:10.2167/jost723.0

- Murphy, K. (2012). The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 8(1), 15–29. doi:10.1080/15487733.2012.11908081

- Nel, E. (1994). Regional development in South Africa: From Apartheid planning to the reform era. Geography Research Forum, 14, 13–29.

- Nel, E., & Binns, T. (2002). Place marketing, tourism promotion, and community-based local economic development in post-apartheid South Africa. The case of Still Bay—The “Bay of the Sleeping Beauty”. Urban Affairs Review, 38(2), 184–208. doi:10.1177/107808702762484088

- Nel, E., & Rogerson, C. M. (2007). Evolving local economic development policy and practice in South Africa with special reference to smaller urban centres. Urban Forum, 18(2), 1–11. doi:10.1007/s12132-007-9003-8

- North West Parks & Tourism Board. (2015). Pilanesberg National Park management plan. Mogwase.

- North West Planning Commission. (2013a). North West mediation strategy and plan for tourism, mining and land claims. Rustenburg.

- North West Planning Commission. (2013b). Provincial development plan. Rustenburg.

- Nyakunu, E., & Rogerson, C. M. (2014). Tourism policy analysis: The case of post-independence Namibia. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 3(1), 1–13.

- Ochieng, A., Visseren-Hamakers, I. J., & Van der Duim, R. (2017). The battle over the benefits: Analysing two sport hunting arrangements in Uganda. Oryx, 52(2), 359–368. doi:10.1017/S0030605316000909

- Pillay, M., & Rogerson, C. M. (2013). Agriculture-tourism linkages and pro-poor impacts: The accommodation sector of urban coastal KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Applied Geography, 36, 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.06.005

- Plummer, R., & Fennell, D. A. (2009). Managing protected areas for sustainable tourism: Prospects for adaptive co-management. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(2), 149–168. doi:10.1080/09669580802359301

- PNP. (2019). Pilanesberg National Park map. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://www.pilanesbergnationalpark.org/map/

- Republic of South Africa. (2011). National tourism sector strategy. Pretoria.

- Rogerson, C. M. (1997). Local economic development and post-apartheid reconstruction in South Africa. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 18(2), 175–195. doi:10.1111/1467-9493.00015

- Rogerson, C. M. (2005). Unpacking tourism SMMEs in South Africa: Structure, support needs and policy response. Development Southern Africa, 22(5), 623–642. doi:10.1080/03768350500364224

- Rogerson, C. M. (2008). Tracking SMME development in South Africa: Issues of finance, training and the regulatory environment. Urban Forum, 19(1), 61–81. doi:10.1007/s12132-008-9025-x

- Rogerson, C. M. (2013). Tourism and local development in South Africa: Challenging local governments. African Journal for Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 19, 9–23.

- Rogerson, C. M. (2014). Reframing place-based economic development in South Africa: The example of local economic development. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series, 24(24), 203–218. doi:10.2478/bog-2014-0023

- Rogerson, C. M. (2015). Tourism and regional development: The case of South Africa’s distressed areas. Development Southern Africa, 32(3), 277–291. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2015.1010713

- SA Tourism Review Committee. (2015). Review of South African tourism. Pretoria.

- Saarinen, J. (2010). Local tourism awareness: Community views in Katutura and King Nehale Conservancy, Namibia. Development Southern Africa, 27(5), 713–724. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2010.522833

- Saarinen, J. (2011). Tourism development and local communities: The direct benefits of tourism to Ovahimba communities in the Kaokoland, Northwest Namibia. Tourism Review International, 15(1), 149–157. doi:10.3727/154427211X13139345020534

- Saufi, A., O’Brien, D., & Wilkins, H. (2014). Inhibitors to host community participation in sustainable tourism development in developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(5), 801–820. doi:10.1080/09669582.2013.861468

- Snyman, S., & Spenceley, A. (2012). Key sustainable tourism mechanisms for poverty reduction and local socio-economic development in Africa. Africa Insight, 42(2), 76–93.

- Stoffelen, A. (2019). Disentangling the tourism sector’s fragmentation: A hands-on coding/post-coding guide for interview and policy document analysis in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(18), 2197–2210. doi:10.1080/13683500.2018.1441268

- Stoffelen, A., & Vanneste, D. (2016). Institutional (dis)integration and regional development implications of whisky tourism in Speyside, Scotland. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(1), 42–60. doi:10.1080/15022250.2015.1062416

- Stoffelen, A., & Vanneste, D. (2017). Tourism and cross-border regional development: Insights in European contexts. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 1013–1033. doi:10.1080/09654313.2017.1291585

- Stone, M. T. (2015). Community-based ecotourism: A collaborative partnerships perspective. Journal of Ecotourism, 14(2–3), 166–184. doi:10.1080/14724049.2015.1023309

- World Bank. (2013). Tourism in Africa: Harnessing tourism for growth and improved livelihoods. Washington D.C.: World Bank.