Abstract

Tourism has been viewed as a development pathway, with alternative tourisms such as volunteer tourism perceived as promising. However, critics have highlighted how white saviourism and Western ideologies of superiority may underpin both development agendas and activities like volunteer tourism. The COVID crisis has impacted both tourism and international development and calls for rethinking. This case study is situated at the intersections of tourism, development and humanitarianism. It charts the evolution of the Cambodian Children’s Trust which emerged in 2007 from the co-founding of an orphanage by an Australian volunteer tourist and a local Khmer leader. Through a process of conscientisation, the orphanage has given way to a community development approach under the leadership of a 100 percent Khmer team in country, leaving footprints of empowering spaces rather than dependency structures. This article addresses the research question of how might we transform the paternalistic desire to “do good” found in both voluntourism and development into a practice of mutual solidarity? Illuminating issues of power and inequality in Western-led models, this article offers a framework for more just partnerships based on Freirian praxis: dialogue building critical consciousness, co-development of transformative praxis, capacity sharing and trust in the capabilities of the people.

Introduction

The important thing to remember is that children are not tourist attractions - Tara Winkler, Cambodian Children’s Trust Co-Founder (Winkler, Citationn.d.).

Tourism has been considered a pathway to development for countries of the Global South (Scheyvens, Citation2002; Sharpley & Telfer, Citation2015). The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the worst development crisis of the 21st century (Steiner, Citation2020), highlighting additionally the vulnerabilities that tourism dependency may bring to developing countries. From the Seychelles to Bali to Croatia, communities are grappling with how to address the sudden loss of international tourists as countries have experienced lockdowns and border closures to protect public health during the global pandemic (Hall et al., Citation2020). What is a moment of important learning on tourism dependency may be over-shadowed by a myopic focus on a rapid return to business as usual after the pandemic crisis (Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020).

This article argues that the larger crisis exposed by the pandemic calamity of 2020–21 is a crisis in development that results from operationalising tourism as a development strategy in the neoliberal framework that perpetuates dependency and inequalities. Development agencies and non-government organisations (NGOs) have fostered strategies built particularly on forms of special interest tourism that carry ideological agendas that must be addressed (Mowforth & Munt, Citation1998). In this study, voluntourism and orphanage tourism are the focus.

Orphanage tourism has proliferated in the Global South as travellers from the Global North are eager for voluntourism opportunities that provide “feel-good” experiences. Voluntourism and orphanage tourism have been criticised for reinforcing inequitable relationships between the Global North and South; particularly, they often emphasise the “development” of the tourists over host community benefit (Banks & Scheyvens, Citation2014). These forms of travel are premised on the traveller’s ability to “make a difference” and on “white saviourism” rooted in neo-colonialism. Bott has suggested “rescue ideologies” underpin them and they are best understood in terms of the “… broader structures of inequality and exploitation underpinning global tourism markets” (Citation2021, p. 11). A Lumos report argued that “orphanage trafficking is more prevalent in countries where there is a significant tourism industry, with orphanages generally being established in key tourist areas” (Citation2021, p. 7).

With the passage of Australia’s Modern Slavery Act 2018, Flanagan (Citation2020) described promising practices for NGOs seeking to strengthen families and reduce institutional care of children. In this context, the story of how Australian Tara Winkler co-founded the Cambodian Children’s Trust (CCT) in 2007 is well documented in a book (Winkler & Delacey, Citation2016) and television documentaries (e.g., ABC, Citation2010, Citation2014). These sources help record the evolution in thinking that resulted in CCT transforming from a non-profit child orphanage that hosted orphanage tourism (particularly by CCT donors) to a Cambodian-led organisation that facilitates empowerment of Cambodian communities, works to build exit strategies in its programmes and co-creates projects for community development.

This article offers a case study analysis of CCT in order to better understand development dynamics, filling a knowledge gap identified by Delvetere and De Bruyn (Citation2009) on private initiatives’ contributions to development. It also critiques the humanitarian impulse found in niches like voluntourism that too often fail to address the problem of development dependency in tourism and may act to sustain poverty. It addresses the research question of how might we transform the paternalistic desire to “do good” found in both voluntourism and development into a practice of mutual solidarity? Here, we chart the evolution of CCT, illuminating the change in consciousness and practice that has seen CCT become an effective, recognised agent and innovative leader of community development in Cambodia and beyond (Nee, Citation2020). Turning to Freirian thinking (Freire, Citation1970), this case study supports conscientisation for those with an inclination to “do good” to instead become partners working in mutual solidarity. This transition is essential in the face of the crisis of development that we now confront (Steiner, Citation2020). Such efforts are timely and in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 17 focused on “global partnerships for sustainable development”.

Literature review

Tourism and development

Until the recent COVID-19 pandemic crisis, the conventional wisdom held that tourism supports development in countries such as Cambodia (Sharpley & Telfer, Citation2015). With the almost total shutting off of the tourism supply chain in 2020, it is possible to now see how dependency on tourism can be perceived as a crisis of development. But critical analysts have identified crucial problems for decades. For instance, Mowforth and Munt (Citation1998) delineated in detail “the uneven and unequal nature of tourism development” (p. 141), demonstrating how alternative forms of tourism that have attracted the new middle classes (e.g., voluntourism) do not necessarily provide sustainable development outcomes but rather may materialise as pathways to sustaining poverty. One chapter specifically addressing the role of external NGOs is subtitled “where shall we save next?” suggested these may represent forms of “neocolonialism” and be “devoid of notions of social justice and concern for local people’s perceptions” (Mowforth & Munt, Citation1998, p. 160).

Revisiting development studies’ dependency paradigm, “dependency theory positions tourism as a new form of imperialism” (Scheyvens, Citation2002, p. 28). Western development models have been based on ideologies that conceive of developed countries as mature, “developing” countries as like “children” and developmentalism as the pathway to guiding the latter to evolve into modernity and maturity (Manzo, Citation1991). Dependency theory and the “development of underdevelopment” are theories explaining how Western approaches to development work in the interests of these wealthy, powerful countries and perpetuate underdevelopment in the countries of the Global South (Mowforth & Munt, Citation1998). Britton’s analysis of Fiji explained how use of international mass tourism as a pathway to enter the global economy required the “subordination of national economic autonomy” (Citation1982, p. 334). However, Mowforth and Munt’s (Citation1998) work showed that even alternative tourisms that are thought to be more benign and even beneficial, harbour power differentials and are implicated in ongoing unequal development.

Debate continues about tourism’s contribution to development and its poverty-alleviating capabilities – particularly for the poorest (see Harrison, Citation2012; Meyer, Citation2012; Scheyvens, Citation2012). Equity and diversity feature strongly in more recent interventions. Rogerson and Saarinen suggested: “the poor are mostly invisible and without agency in the existing debates on tourism on tourism in the Global South” and that we should also focus on the poor as potential tourists themselves (Citation2018, p. 32). From an Indigenous perspective, Kuokkanen outlined a war against subsistence economies as a strategy to make Indigenous communities and others dependent on capitalist economies; as a strategy of resistance and resurgence, she recommends revival of Indigenous subsistence through social economy frameworks as a pathway to Indigenous governance and livelihoods (Citation2011, p. 232).

However, dependency arguments are being revived in COVID’s wake. Despite some analysts dismissing the relevancy of dependency theory in a globalising world, Ghosh (Citation2021) argued it remains relevant to understanding development, underdevelopment and economic relations between the Global North and South. Recent work describing “the drain from the global South” argued:

“Advanced economies” rely on unequal exchange to facilitate their economic growth and to sustain high levels of income and material consumption. In recent years, the drain has amounted to around [US]$2.2 trillion per year (constant 2011 dollars) in Northern prices… These patterns of appropriation through North–South trade are a major driver of global inequality and uneven development (Hickel et al., Citation2021, p. 13).

In recent years, development aid has become more complex, with the entry of new actors undertaking private initiatives, such as the one under study here, that have been labelled a “fourth pillar” (governments, multilateral institutions and established NGOs being the original 3 pillars) (Delvetere & De Bruyn, Citation2009). Delvetere and De Bruyn (Citation2009) argued that these private initiatives for development: deserve greater research focus; have mixed potential as they offer “…involvement and enthusiasm, but often lack… essential knowledge and experience”; and potentially offer the Global South partnerships “… which… will be more horizontal, accommodating, generous and durable in nature than with the traditional development organisations” (pp. 920-1).

Voluntourism and orphanage tourism

Voluntourism (volunteer tourism) is one of the niches of tourism generally thought to be more beneficial. Voluntourism involves: “tourists who, for various reasons, volunteer in an organized way to undertake holidays that might involve aiding or alleviating the material poverty of some groups in society…” (Wearing, Citation2001, p. 1). However, there are critics of this impulse to “do good”. Illich (Citation1990) criticised American voluntary service missions to Mexico as paternalistic, neo-colonial interventions that distort local lifeways, tying people into a developmentalist, modernisation modelFootnote1 that only benefits a small elite.

More recently, Wearing and McGehee cautioned that voluntourism “… can lead host communities to become dependent upon volunteer tourism sending organizations, undermining the dignity of local residents, exceeding the carrying capacity of the community if not properly managed…” (Citation2013, p. 125). With a critical lens, serious issues of power discrepancies, racism and exploitation become evident. Sin noted “… unfortunately, volunteer tourism, similar to geographies of responsibility and care, has more often than not been framed in the position of the ‘First world’ being responsible for the wellbeing for a ‘Third world’, poor, and marginalized subject” (Citation2010, p. 988). Research by Freidus on voluntourism found “…westerners are christened more knowledgeable than locals in whatever project they endeavor to complete…This can reify the hegemony of western cultural authority that undergirds the types of projects volunteer tourists undertake” (Citation2017, p. 1308). This can have contradictory, material impact as volunteers take up valuable job opportunities from more qualified, unemployed locals.

This issue of power and inequality at this interface is even more pronounced for orphanage tourism, a popular component of alternative tourism. A report on the global volunteering market released in June 2018 identified Cambodia among the top 10 global orphanage voluntourism destinations and the USA, UK and Australia as the top countries sending volunteers to orphanages overseas (ReThink Orphanages, Citationn.d.). Pelling reported:

Between 2005 and 2015 it’s estimated that the number of orphanages in Cambodia increased by more than 60 per cent. Most… of that growth has been attributed to a boom in so-called “orphanage tourism”, where tourists turn up, spend some time with the children, then leave behind a nice wad of cash (Citation2019).

Children in orphanages are often kept in slavery like conditions, fully owned by orphanage directors and exploited for profit through forced “cultural” performances for tourists, forced begging, and forced interaction and play with visitors. Children are often kept in poor health, poor conditions and are malnourished in order to elicit more support in the form of donations and gifts (cited in Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade (JSCFADT. ,), Citation2017, n.p.).

Anti-slavery discourse implies that the eradication of orphanage tourism will automatically improve the lives and uphold the rights of children. It fails to acknowledge the painful fact that poverty remains the principal cause of the violation of children's rights because lack of resources seriously impedes, or entirely prevents, their access to basic human rights such as healthcare, water, food and education (Citation2021, p. 3).

It is difficult to accept that orphanage tourism, voluntourism and donor benevolence actually drive child exploitation and trafficking through orphanages in developing countries (JSCFADT. , Citation2017). Unfortunately, monetising this humanitarian desire can in fact lead to devastating consequences and a vicious circle of exploitation. This circle includes: NGOs who need funds and a reason to exist; voluntourists and donors who naively act on their humanitarian desire; families in the Global South with insufficient resources to care for all of their children; and an aid system that is built on ongoing inequality and dependency.

Initiatives to address child welfare and vulnerabilities in tourism are underway. The first International Summit on Child Protection in Travel and Tourism in 2018 issued a call to action asking: “all key stakeholders to adopt a comprehensive, child rights-centered and multi-stakeholder framework where all actors actively work together to end impunity of the travelling child sex offenders” (Global Study of Sexual Exploitation of Children in Travel & Tourism, Citation2018). Guidelines entitled “Child Welfare and the Travel Industry” offered comprehensive advice to guide the tourism sector to responsible practices (ChildSafe Movement & G Adventures, Citation2018). It specifically addressed tourist visits to orphanages and other children’s spaces, advising tourism companies:

Children centres are meant to be a safe place for children. They are not tourist attractions. Visiting school classrooms and orphanages not only disrupts child development but can also put children at risk of emotional or physical harm through direct or indirect contact with travellers with inadequate supervision (ChildSafe Movement & G Adventures, Citation2018, p. 13).

White saviourism

White saviourism has recently received attention from tourism analysts (e.g., Bandyopadhyay & Patil, Citation2017; Wearing et al., Citation2018) and this provides the missing piece to the puzzle of motivating ideologies that underpins the development dynamics described here. White saviourism describes a situation when a “…white person guides people of colour from the margins to the mainstream with his or her own initiative and benevolence…[this] has the tendency to render people of color incapable of helping themselves — infantile or hapless/helpless victims who survive by instinct” (Cammarota, Citation2011, pp. 243-4). As well as individuals, this syndrome is also operative among some development NGOs (Mowforth & Munt, Citation1998, p. 160). White saviour analyses represent critical interrogation of the humanitarian impulse and the way that it is enacted in a neoliberalised context.

In his assessment of the “white savior industrial complex”, Cole (Citation2012) gave a scathing assessment of young Westerners’ impetus to do good while lacking wider political insight:

Africa has provided a space onto which white egos can conveniently be projected. It is a liberated space in which the usual rules do not apply: a nobody from America or Europe can go to Africa and become a godlike savior or, at the very least, have his or her emotional needs satisfied. Many have done it under the banner of “making a difference” (p. 2).

The historic roots of racial inferiority/superiority are further perpetuated by contemporary neo-colonial aid relationships in volunteer tourism … The colonial narratives are retold through modern discourses of volunteer tourism and development, where those in the global South come to believe that they have lower capacity for development augmented by inferior science, technology, and resources… (Citation2017, p. 652).

Freire’s “pedagogy of the oppressed” and working in mutuality

Certain voluntourism analyses have considered how the relations between communities, mediating organisations and volunteers can be reconfigured for justice (e.g., Guttentag, Citation2011). Simpson insisted that a “pedagogy of social justice” (PSJ) (Citation2004, p. 690) must underpin voluntourism. Henry (Citation2019) advanced these discussions by outlining three steps to support a PSJ: researcher reflection, action research and continued engagement with returned volunteers to support their ongoing radical consciousness and action. Henry’s proposed agenda was intended to foster an approach based on social justice “embedded within and continuing beyond voluntourism…” (Citation2019, p. 563).

This article employs Freire’s (Citation1970) analysis of the “pedagogy of the oppressed” and his articulation of mutuality as a way of answering the research question of how we might move beyond “doing good” in voluntourism and development. Here, Freire addresses how those in positions of power and privilege may want to support those who suffer oppression. He outlines the nature of oppression, explaining that the humanity of both the oppressed and the oppressor are undermined. Some in the oppressor category may develop a guilty awareness of their role in oppression and seek to mitigate it; but if these efforts fail to address the structural roots of oppression, they only offer “false generosity”, thus maintaining the oppressed in binds of dependency (Citation1970, p. 49). For Freire, “oppression is domesticating” (p. 51) and so members of both the oppressor and oppressed classes must continually struggle for their humanisation and freedom. Critical to this is conscientisation (conscientização), which refers to mutual, critical awareness work that the oppressed do in understanding their conditions leading to a determination that “the concrete situation that begets oppression must be transformed” (p. 50). The fundamental basis of this work is the recognition of the oppressed’s own knowing (p. 68) and abilities to transform their situation.

The aim of this mutual work is to become, both oppressed and oppressor, “human in the process of achieving freedom” (p. 49). This work is achieved through “praxis: reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it” (p. 51) in an effort to gain full humanity and carry out “revolutionary” change (p. 66). Allies work in solidarity with the oppressed but they are cautioned to not fall into the trap of trying to lead and thereby return to oppressing. The method for this work is dialogical action where allies (revolutionary leadership in Freire’s terms) support the oppressed in conscientisation and their praxis towards liberation (p. 67). This transformative work is not something the oppressed can do alone nor something others can do for them; it is derived from working with and not for (p. 67). “Founding itself upon love, humility, and faith, dialogue becomes a horizontal relationship of which mutual trust between the dialoguers is the logical consequence” (Freire, Citation1970, p. 91).

This thinking from Freire offers a framework for transforming both tourism and development for working in mutuality rather than in the “false generosity” of white saviourism. It is built on critical consciousness developed through dialogue, co-development of a praxis for changing the material conditions of the community, what we would call “capacity sharing” and trust in the capacities of the people. It is an ongoing process in which the people and their allies come to understand their context and how it might be transformed for the better and co-create a shared humanity in this mutual praxis.

Linking together the concepts set out in the literature review, a framework is revealed pertaining to conventional international development which is based on an ideological worldview that recipients are inferior, supporting practices that may be best described as paternalistic. Integrated relationships feature between voluntourism, development, development aid NGOs and countries of the Global South which perpetuate a cycle of dependency. Yet, as Lediard (Citation2016) demonstrated if justice is placed to the fore, volunteer tourism relations can be transformed “from power-over to power-with” (p. 100). This is the promise of the Freirian conceptualisation of mutuality in praxis. Following a discussion of research methods, we present a case study of an NGO and its co-founder that illustrates the development of a mutual praxis towards liberation from dependency.

Methodology

This research has employed qualitative case study methods to consider the case of the Cambodian Children’s Trust and the role of its co-founder Tara Winkler. A case study is “the in-depth investigation of a phenomenon in its context” and has been well utilised in qualitative organisational research (Piekkari & Welch, Citation2018, p. 357). Case study approaches are effective when research seeks to answer “how” and “why” questions and when the research questions “…require an extensive and ‘in-depth’ description of some social phenomenon” (Yin, Citation2014, p. 4). Qualitative case studies offer “an intensive, holistic description and analysis of a bounded phenomenon such as a program, an institution, a person, a process or a social unit” (Merriam, Citation1998, p. xiii).

This research follows a critical, social constructionist approach recognising that people construct their own understanding of the world through their experiences and reflections on these experiences (Schwandt, Citation1998). This holds true for both the researcher and the researched. However, as Sauer and Lyle explained, Ricoeurian ethical philosophy can help ground narrative constructionism and overcome its “postmodern predicament” through “an ontology of action, ethics, and the ‘responsible self’” (Citation1997, p. 203). Thus, in this perspective of constructionism, the narrative of the self is always in relation to others; “ethical identity concerns not just the being of the self but being with and for others” (p. 221). This combined with critical research praxis, prepares research with tools to name, critique and overcome forces of oppression and support emancipatory collaborations (Giroux & Giroux, Citation2006).

The first author has been a donor to CCT after learning of Winkler’s work through a television documentary (ABC, Citation2010). This research project was developed following a donor update zoom meeting with Winkler in 2021. In that discussion, a shared interest in decolonising development became clear and we agreed to undertake research that studied CCT’s transition from child rescue to community empowerment. The second author contributed vital development studies expertise to the project, and she has no prior or ongoing association with CCT. The third author has worked in development (often with a gender focus), including in Bangladesh. Here, she first experienced the dependency of local communities on NGOs and the limiting effect of this on the transformational capacity of individuals (becoming evident after the rollback of long-standing programs). Inspired by CCT’s village hive model to bring power back to communities, she is currently involved in designing impact assessment strategies with CCT.

The data included primary and secondary resources as well as a small number of focused interviews. Primary data included CCT annual reports, program evaluations, Winkler’s book How (not) to start an orphanage…by a woman who did (Winkler & Delacey, Citation2016), audio-visual materials (e.g., TED Talks and television documentaries), testimony to the 2018 Australian Parliamentary Inquiry into establishing a Modern Slavery Act and numerous reports about child protection and orphanages in Cambodia (deriving from the Cambodian government and NGOs such as UNICEF and Save the Children). The book assisted in identifying preliminary themes as Winkler was courageously honest in addressing the issue of white saviourism, following a driving ethic of “act to do better when we know better” (additional themes included “CCT as empowering youth of Cambodia”, “a rising consciousness leading to action” and a “transition of approach from doing good for, to working with” (Winkler & Delacey, Citation2016). Descriptive coding was applied to this content setting out a categorised inventory of Winkler’s work and CCT (Saldaña, Citation2015).

Interviews occurred by video-link between May and September 2021 and included both Australian and Cambodian leadership of CCT and its sister organisation CCT Australia (CCTA) (n = 5). Each interview, conducted in English, lasted up to one and a half hours in duration following a semi-structured interview protocol (Appendix A); two of the five interviewees with the most holistic insights were interviewed three times for securing greater detail and clarification. The project was approved through the ethics approval process of the University of South Australia’s Business School, which informed the protocols for obtaining informed consent and securing participant rights. Anonymity was waived by all interviewees after an informed consent process. Participants were given access to the interview transcripts for clarification and correction and the chance to review a draft of the themes and findings in support of stakeholder validity checks. Analysis of the interview data followed an inductive approach being very attentive to the voices of the informants. A second round of analysis then followed using abduction as a flexible approach to refine themes with attention to the literature and its gaps (Pierce, Citation1978).

As critical, social constructivist research, this work presents the evolution of Winkler’s and CCT’s work from child welfare to community development in Cambodia. This leads to considerations of dependency in both tourism and development. While an independently conducted external program evaluation validating CCT claims is available (Nee, Citation2020), this aspect was not the focus of our study, which instead prioritised the seldom accessed personal narratives of white saviourism and how conscientisation may dismantle it.

Background to the Cambodian children’s trust

“To create systemic, lasting change, we focus our efforts on an ‘upstream’, preventative approach that addresses the root causes of complex social problems that make children unsafe and unable to access their basic needs” (CCT, Citation2020, p. 7).

Tara Winkler’s involvement in Cambodia began when she travelled to the country on an Intrepid Tour of Southeast Asia in 2005. She planned to stay on after the tour concluded but, because she felt disconcerted holidaying in a place struggling with poverty, she decided to volunteer with the Akira Landmine Museum. Following this, she was invited on some orphanage visits and experienced the compulsion to buy materials to support the children she encountered there.

A visit to one of these orphanages resulted in the founding of CCT in 2007 by Tara Winkler and Jedtha Pon, both of whom rescued 14 children from a corrupt and abusive orphanage in the Cambodian province of Battambang.Footnote2 Following this rescue, CCT initially operated as a well-resourced orphanage. Winkler sought donor support from her native Australia and some of these donors and others visited and volunteered at CCT as orphanage tourists.

While operating the orphanage, Winkler became aware that such institutional care wrought unintended harm on children’s development and after becoming fluent in Khmer learnt that all the children had family. Their families had only given them up to institutional care due to poverty, thinking that the orphanage would give their children access to education and better futures. As a result of this awareness, CCT undertook a coordinated effort at reunification and reintegration of the children with their families and communities of origin. CCT then became the first orphanage in Cambodia to transition from orphanage to a family-based care approach which evolved into the “Village Hive” model (more below).

CCT is now a Khmer-led organisation focused on community-run child protection to strengthen families and keep children safe through promoting local agency, community empowerment and sovereignty. CCT has followed a reflective and transformative praxis to working with communities on identifying and meeting their development needs all the while partnering in capacity sharing. CCT’s efficacy is demonstrated by the way it has evolved to implement constant improvement and the long-term sustainability of its programs. As an NGO, it particularly developed a commitment to embedding exit strategies in its programmes as a result of this learning process, consciously rejecting the fostering of dependency while planting seeds for community empowerment. CCT’s operations in Cambodia are supported by the fundraising, promotions, donor liaison and impact evidence-gathering of its sister organisation CCT Australia (CCTA), made up of a team of four Australians.

CCT established a social enterprise restaurant called Jaan Bai [‘rice bowl’] in 2013. The restaurant is now independently operated and managed by Cambodian youth in a profit-share agreement. In 2015, CCT identified the need for strong Information and Communication Technology (ICT) training for youth, commencing a partnership with all five public high schools and the teacher training college in Battambang City to develop an ICT programme. This programme is now integrated into the national high school curriculum and is fully funded and operated by the public schools, with to date over 27,000 students having completed the course and more than 1,100 teachers trained to deliver the ICT curriculum. Further evidence of success is found in the number of students who have advanced to enrol in higher studies in computer science (n = 827) and who have won or placed in national and international STEM competitions (CCT, Citation2019).

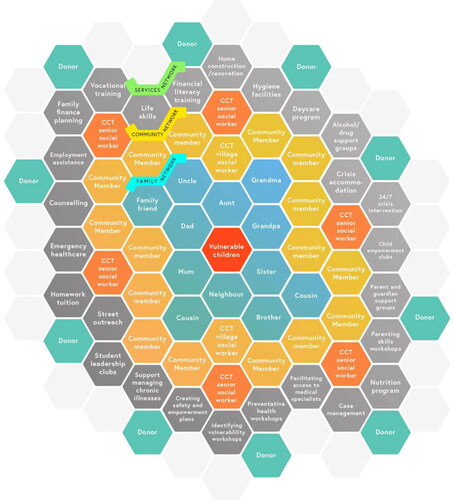

Learning from the success of the Jaan Bai and the ICT programmes, CCT launched the first formal pilot of its Village Hive model in 2017 (Hive standing for Holistic Interventions Vulnerability to Empowerment). The approach is co-created with local communities from ideation to implementation through CCT-led workshops (see Appendix B “Co-creating child protection networks within villages”). Its purpose is to combat and prevent multidimensional poverty by bringing multisectoral services into villages and mobilising community-wide action to protect children from maltreatment, prevent child-family separation, reunite families and foster long-term resilience and self-sufficiency within families. This addresses the sustainability of the village community and recognises the intersectionality of the social space. Today, CCT’s Village Hive reaches 104 villages in Battambang province and has prevented thousands of children from being separated from their families and reunited hundreds of children in orphanages with their families. and indicate the holistic approach of the Village Hive model, embedding needed services within the community to be integrated under local governance rather than separate NGO authority. Appendix C outlines the Ou Char pilot of the Village Hive model and shows the embedded, inclusive, collaborative approach. Appendix D highlights the main programmes of CCT presented chronologically demonstrating the evolutionary change of its programmes from a “downstream” child rescue approach to an “upstream” community empowerment approach.

Figure 2. CCT’s vision of a self-contained Village Hive approach centred on vulnerable children within empowered family, community and services networks, and strengthened by CCT staff and donor support in its establishment phase (see CCT, Citation2020).

CCT follows a partnership approach with families, communities, all levels of government, other NGOs and NGO networks such as Family Care First and large donors such as United States Agency for International Development (USAID). CCT’s track record in systems building and sustainable programming has led to CCT being recognised as an innovative leader in the Cambodian child protection sector and becoming the largest implementing partner of the Family Care First/REACT Network (FCF, Citationn.d.).

Findings

"I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better" - Maya Angelou

The evolution of CCT features an urge to do good but built on an open, reflective and responsive approach that enabled significant change from mainstream practice. The findings from this research are arranged by the major themes that emerged from the research data. These include: white saviourism and moving beyond it; when you know better, do better; and Cambodians know.

White saviourism and moving beyond it

In her book, Winkler explained her initial desire to do good and her evolving critical consciousness as she gained greater insights through experience. One incident demonstrates this as she described beginning to teach English to the children:

The words of Nelson Mandela kept running through my mind: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world”. In my own little way, I thought I was changing the world. Insert face palm here… I had a lot to learn about the potential harm that could come from volunteering with vulnerable children (Winkler & Delacey, Citation2016, pp. 67-8).

CCT former Operations Manager Erin Kirby stated:

Everybody wanted to meet with Tara and gave her this white saviour title… that she saved these kids, that’s the whole narrative of the original ABC Australian Story. It got put onto her and I think it took her years to see it, to learn that term white saviour and [to] back away from [it]… but at the same time people wouldn’t want to give us money unless they got to meet her … I think it’s something that she’s had to do a lot of critical reflection on, a lot of work personally… to see how can she still do the work that she wants to do, but in a way that is actively working against that, rather than benefitting from it (pers. comm., 6 August 2021).

Leadership qualities are more often made, not born. The opportunities I’ve been granted, thanks to my white privilege, has allowed me to cultivate and hone the unique set of skills required to be an effective leader. Truth is, as a young, naive and inexperienced expatriate, I should never have given the opportunity to set up an orphanage in Cambodia. However, I did at least use those privileges to bring Jedtha [CCT Co-Founder] and Sinet [orphanage survivor and Director on the CCT Board] along with me so that they too had the opportunities to develop the leadership qualities that were vital to their ultimate empowerment as they stepped into their rightful roles as CCT’s leaders (pers. comm., 10 May 2021).

If Tara didn’t step out of her power, Jedtha wouldn’t be able to run this work by himself, as he does today. I think, you can say that [CCT] is not only Jedtha’s family, but also Tara’s too. It takes courage for a person to give up the one thing that they love the most… for a change that… will make a better future for the Cambodian people. I think that is an incredible role model and incredibly empowering … we can learn from… that … It’s not easy… you have the power to do anything you want, that is your life, your job, why would you give that away to other people? But I think she inspires us to see what real leadership and a real role model looks like.

So, for me too, as a care leaver facilitator and a care leaver myself, I will never be a care leaver leader for the rest of my life. I am coaching and giving advice to other care leavers to run it by themselves, because later … I will step aside. This is what new power means: let the local people do it and the right people will come to do the job (pers. comm., 3 September 2021).

Handing over a self-contained Village Hive involves restructuring our model, to ensure we are working within public systems and operating out of public facilities, rather than privately run programs in parallel. Handing over to the local council means the commune makes valuable contributions to the Village Hive in the form of human, social and financial capital. This demonstrates the value the community place on the Village Hive and shows their commitment to its long-term success. CCT can then exit and move on to partner with the next community, thereby having an actionable, tangible exit strategy that allows us to scale economically (CCT, Citation2020, p. 17).

However, Winkler noted that CCT has not fully arrived at a point where empowerment and emancipatory practices are fully enacted because of the ongoing structural context of CCT operations:

CCT works at a sort of omnishambles of very complicated sectors - the child protection and international development sectors mirror each other in their roots and their historical complexities around colonialism, race, paternalism and power dynamics. It is no wonder we started where we started (pers. comm., 10 May 2021).

When you know better, do better

Currently CCT activities in Cambodia are 100 per cent Khmer operated, a quite radical transformation from the beginnings based on the humanitarian impetus of a young Australian woman. CCT’s evolution is built on a dedicated practice of engaged reflection and learning which is the organisation’s defining feature. As CCTA Managing Director described it, “…a process of a pilot, reflection and adaption is really that thread that’s been through CCT right from the beginning” (Keir Drinnan, pers. comm., 10 July 2021).

The most important example of critical reflection and responsive change is evident in the change in consciousness of Co-Founder Tara Winkler herself. Her ability to reflect on poor practices, to be open to change and to be humble in openly sharing these stories in her book, speeches and media interviews offers others a chance to develop critical consciousness. Winkler has noted:

I have made all of those mistakes myself. I came to Cambodia as an orphanage tourist, and then I was a voluntourist when I volunteered at the orphanage, and then I set up an orphanage, and then I facilitated orphanage tourism. I have learnt from those mistakes… the hard way … when you make mistakes in development, you're making mistakes with people's lives (cited in Ryan, Citation2015).

CCT has piloted programmes and evolved its practices through this dedicated learning approach (See Appendix D). Keir Drinnan explained:

Two years ago, we looked at the issues and reflected on some of the successful programmes that we’d had and realised that they were all embedded within the local infrastructure. They were partnering with the local stakeholders, [so] ownership and accountability for that program laid with them. That’s why they continued on after the funding had stopped. I think that changed our thinking around how we would deliver programmes (pers. comm., 10 July 2021).

Cambodians know

Development agencies and NGOs have often relied on expatriate consultants to provide expertise. Underpinning the mindset is that the local people lack skills and capabilities. In its early years, CCT also brought in external experts to advise, train and set up processes for managing, for instance, human resources, social work, project management and finance. It now actively avoids hiring foreigner consultants and has transitioned to a 100 per cent Khmer leadership team in Cambodia. As Sinet Chan, a Director on the Board of CCT, stated: “I think that many NGOs in Cambodia don’t know about the power of the local people” (pers. comm., 3 September 2021). In her interview, Keir Drinnan explained there was a three-year plan developed in 2019 to transition from foreign involvement to solely Khmer leadership which was expedited due to the COVID pandemic and its border closures.

Jedtha Pon, CCT Co-Founder and Director, stated the value of the shift to 100% Khmer leadership of CCT and the critical discovery of Cambodian voice:

It’s really important for our Cambodian people … because we know our culture, we speak our language… We know what we want… we live it; we’re owning it. Everyone here has accountability for what we are doing.

Previously, the communication team was all foreigners and now it is all Khmers. It has been important for us to recruit and look for local staff to fill such roles. You can imagine that for the social work, Cambodia has only [recently] had university degrees in social work… That has made it hard to find experienced, qualified social workers to do this job. That is why sometimes we needed [foreign experts]. But now… all leadership roles are for Khmer (pers. comm., 20 August 2021).

Chan’s positionality as a child that experienced both abusive and non-abusive forms of institutional care informs her practice in leadership in CCT. She explained in her interview how CCT leadership recognised the harms of institutional care on children and responded by planning the closure of the orphanage and reuniting and reintegrating children with their families. But from her own personal experience, she identified a need to support care leaversFootnote3 (those that leave institutional care to live in the community at adulthood):

… back then I was only a CCT Ambassador and only a kid’s voice. CCT had changed from an orphanage to reuniting all the children back with their families. But at the same time, I turned 18… an adult, so, I moved to living independently… since then, I became an activist for children’s rights, for children survivors from the orphanage. … now we have a care leavers club which I run. I support care leavers who are living independently after leaving the orphanage. Now we provide support to them as well (Sinet Chan, pers. comm., 3 September 2021).

Former Operations Manager Erin Kirby explained how CCT staff began working more closely and effectively with commune level governance:

… it’s not just having an MOU with the government or going to the required meeting, sitting there and getting your name ticked off a list… When we take on a new family, we get our referral coming from the CCWC, who are responsible for child protection cases at a local level… [We] then go out with our assessment forms which are government forms that our social workers use…In the past they would go out and do it themselves and then they would take those forms to be signed off by the CCWC member because that person’s really busy… and not always available. However, now that the social workers understand how… important it is, they’re undertaking collaborative case management in partnership with CCWC and coaching and mentoring government social workers to build their capacity (pers. comm., 6 August 2021).

I lived like a queen, because CCT back then was the best; we had tutors… painting, dancing, music, … holidays. But it’s a small amount of people that received that support. But now there’s resources going to different houses, different villages, different communities. Each home then can plan for themselves… I don’t think it is good to empower one person like me or other children, but rather all the donors’ support that we get is going to the household… Helping the … whole family. I think it’s a great [approach], because we know that raising one kid in an orphanage is expensive versus raising them in the family (pers. comm., 3 September 2021).

The most important point of distinction in CCT’s Village Hive model from mainstream models of development based on dependency is the embedded exit strategy. CCT described it:

We are working towards integrating the Village Hive into the public sector where it can be delivered sustainably by communities.

The ultimate aim of the pilot is to create an evidence base for a prevention-focused child protection system that can be scaled across Cambodia.

The pilot will transfer the delivery of the Village Hive multi-sector services from CCT to the local councils, who rightfully hold the responsibility to provide services to their community (CCT, Citationn.d.).

Ensuring vulnerable families are connected to universal services and support, within their own communities, to enable them to care for and raise their children well. That’s working with the local authorities to help embed those services into existing public facilities, such as public schools, within those communities, and providing mechanisms for families to be able to be referred for those supports and services. This includes working with the community to obtain the financial support required through their commune investment plans for social protection mechanisms within their own communities… the Village Hive is utilising the power of networks - family networks, community networks and services networks (pers. comm., 10 July 2021; see also Appendix C).

To achieve systemic change our approach must also be empowering. The term “empowerment” is so overused by charities that it’s almost lost its real meaning and has been reduced to a buzzword…

We believe empowerment should be a conversation about power. The people whose lives are affected by programming decisions, need to be the ones making them. They need to have seats at the decision-making table and be the architects of the programs. Our experience has shown us that local people hold all the wisdom required to design and implement programs that safeguard children and empower families in their own communities (CCT, Citation2020, p. 7).

Discussion

This research has offered an in-depth case study to learn from one NGO co-founder who traversed the path from white saviour to ally and who supported her organisation to simultaneously transition from fostering development dependency to fostering local agency through the Village Hive approach. This work continues on from the earlier, in-depth work of Guiney (Citation2015) and reported also in Guiney and Mostafanezad (Citation2015). The latter documented the beginning of the anti-orphanage movement in Cambodia from 2011 and questioned the Cambodian government’s ability to fund orphanages and social welfare if private and corrupt orphanages were shut down. CCT’s example models an approach where white saviourism and NGO hegemony are abandoned after a committed praxis of transformation. Understanding that Cambodian communities and governments are the foundations for sustainable development, a practice of “working with” has been established based on recognising and supporting their capabilities at the local level through the Village Hive approach.

Freire’s work (Citation1970) concerning conscientisation referred to earlier is useful in theorising Winkler’s and CCT’s work with rather than for communities in Cambodia. Freire connected conscientisation to action which is based on a trust in the capabilities of communities: “To achieve this praxis, however, it is necessary to trust in the oppressed and in their ability to reason. Whoever lacks this trust will fail to initiate (or will abandon) dialogue, reflection, and communication…” (Citation1970, p. 66). This case study has explained both the evolving conscientisation of Winkler but also of her CCT colleagues that enabled them to co-develop a practice of working with Cambodian families and communities. Instead of the traditional “capacity building” approaches to development, this Freirian practice is best described as “capacity sharing”, describing when parties in the development process share experiences and knowledge to strengthen decision making under an agreed development trajectory.

Freire provides a useful way of understanding this transformation:

Authentic help means that all who are involved help each other mutually, growing together in the common effort to understand the reality which they seek to transform. Only through such praxis—in which those who help and those who are being helped help each other simultaneously—can the act of helping become free from the distortion in which the helper dominates the helped (cited in hooks, Citation1993, p. 150).

What I thought would be the biggest challenge was the willingness of the stakeholders to take control of the project and the administrative burden that would come along with it. On reflection, this revealed a personal blind spot. In reality, each and every stakeholder responded with an overwhelming enthusiasm to take on the responsibility (Tara Winkler, pers. comm., 21 December 2021).

As Lediard (Citation2016) demonstrated, if justice is placed to the fore, volunteer tourism relations can be transformed “from power-over to power-with” (p. 100). Cammarota argued further that “justice can occur with the oppressed in leadership positions and the oppressor adhering to and following this leadership” (Citation2011, p. 245). This is indeed what CCT’s evolution has modelled as CCT has transitioned to a full Khmer leadership team, with CCTA acting as support for donor engagement in Australia.

Freire’s conceptualisations of conscientisation and mutuality also suggest that partners from the Global North can and should learn from partners in the Global South. Therefore, the Village Hive model that CCT developed may be considered for adaptability in communities throughout the world. Absent a white supremacy mindset of white saviourism, reciprocal learning and action for development is not only possible but may be imperative as we seek to address multiple, future crises confronting us all.

CCT has exhibited some of the strengths and weaknesses identified by Delvertere and De Bruyn (Citation2009) as a private initiative for development. However, what this research has demonstrated is that a commitment to continual critical reflective praxis has helped it evolve successful programmes built on transitioning to Cambodian leadership, partnership approaches with all stakeholders and a belief in the capacities of families and communities to build their own livelihoods with the right kinds of supports from these partnerships (in contrast to perpetual dependency- see Appendix B).

However, there are some difficulties with the upstream approach of CCT’s Village Hive model. Individual donors may prefer an individualised, child sponsorship approach that often pertains to NGO aid to orphanages (Sinet Chan, pers. comm., 3 September 2021). Drinnan concurred, stating: “it’s difficult for donors to understand our model, even institutional donors. I know USAID is adverse [to local authorities managing aid funds given to CCT]… there’s a perceived lack of transparency and accountability that such organisations require…” (pers. comm., 10 July 2021). Winkler expanded:

The biggest challenge encountered in shifting power to local communities turned out to be the Global North’s pervasive belief in the corruption and incompetence inherent in Cambodian people, authorities and institutions. This results in a lack of trust that prevents most institutional donors from funding projects in which they don’t retain sufficient control. I see this as a glaring impediment to Cambodia’s development and the ultimate empowerment of its people (pers. comm., 21 December 2021).

Recommendations arising from this research include:

All children must be protected from the exploitation and commodification that the neoliberal model brings.

Development must be focused on a commitment to tangible actions for change in the material causes of oppression rather than being the “false generosity” of continual aid.

Development models should be reconfigured as collective, collaborative and co-created engagements for capacity sharing and empowerment; dependency is anathema.

Collective dialogue for conscientisation offers a pedagogy of justice to develop co-understanding of the conditions under which projects are undertaken.

Trust in the capacities of “recipients” is essential to this Freirian approach to development.

Tertiary studies in tourism and development should include curricula on pedagogies of social justice, white saviourism and applied praxis for working mutually with stakeholders for empowerment and co-created positive change.

Conclusion

With ten per cent of children in Cambodia reportedly not living with their biological parents despite having at least one living parent, children are clearly vulnerable (UNICEF. , Citation2018, p. 43). Orphanage tourism is a catalyst to child trafficking, exploitation and labour and measures are being implemented to address this. This falls under the SDG agenda as target 8.7 calls for the end of child labour in all of its forms by 2025. Clearly, all stakeholders must support the termination of orphanage tours and associated voluntourism experiences. The case of CCT presented here illustrates these issues but it also points to the imperative to not stop there; it is essential to build a mutual praxis to address the structural injustices at the root of these issues.

This article has argued that we confront a crisis of development which results in poor outcomes for communities. Dynamics exposed here include: white saviourism; a corresponding ideology that the receiving community is inferior and incapable; and a resultant dependency approach to development. When we think about SDG 17 on partnerships for sustainable development in light of the CCT case study presented here, we might think of it in a Freirian sense of mutuality as illustrated in this case study of CCT. This work suggests a guiding framework for more just partnerships: critical consciousness developed through dialogue, co-development of a praxis for change, capacity sharing and trust in the knowledge and capabilities of the people.

Despite the limitations of case study research in terms of non-generalisability, the findings of this research may be used to inform tourism research, education and industry practice. Many university programmes engage students in internationalisation experiences and fieldwork that might involve voluntourism and orphanage visits. While we encourage all tourism advocates to seek to make a positive difference and support those who are disadvantaged in our global community, critical literacy concerning white saviourism, neo-colonial practices and the wider context of structural injustices is essential to inform effective and just praxis (see Scheyvens & Storey, Citation2014). Additionally, curricula and training for Freirian practices are helpful in guiding efforts to build pedagogies of social justice in the tourism domain.

After the COVID pandemic, development assistance will be even more important as countries of the Global South will have carried a heavier burden, particularly tourism dependent nations. One United Nations Development Program representative placed aid top on the list in addressing the pandemic’s impacts: “Governments need to boost foreign aid spending now, and sustain it” (Steiner, Citation2020, n.p.). This study suggests simultaneously rethinking our approaches to work from a consciousness of mutual solidarity if we are to transition from sustaining poverty to sustainable development.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (466.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Cambodian Children’s Trust, and in particular Tara Winkler Keir Drinnan, for their support of this research. We also thank Dr Jacky Desbiolles who provided vital research support. Finally, we appreciate the advice and support provided by the journal’s Editors, Guest Editors and anonymous peer reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Freya Higgins-Desbiolles

Freya Higgins-Desbiolles is Adjunct Senior Lecturer in Tourism Management, Business Unit, University of South Australia and Adjunct Associate Professor with Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies, University of Waterloo. Her work focuses on social justice, human rights and sustainability issues in tourism. She has worked with industry, community and non-profits on projects that have worked at the cutting edge of ethical and sustainable tourism. She is the co-editor of the recent books Socialising Tourism: Rethinking Tourism for Social and Ecological Justice (2021) and Activating Critical Thinking to Advance the Sustainable Development Goals in Tourism Systems (2021).

Regina A. Scheyvens

Regina A. Scheyvens, Professor & Co-Director - Pacific Research and Policy Centre. Her research focuses on the relationship between tourism, sustainable development and poverty reduction, and she has conducted fieldwork on these issues in Fiji, Vanuatu, Samoa, the Maldives and in Southern Africa. She also very interested in gender and development, sustainable livelihood options for small island states, and in theories of empowerment for marginalised peoples. Recent collaborative projects explore economic development on customary land in the Pacific, links between tourism and the SDGs, and links between corporate social responsibility and development in the Pacific.

Bhanu Bhatia

Bhanu Bhatia, PhD, work as a lecturer in Business and Economics at Charles Darwin University. Her research focuses on inequality, gender, microfinance, diffusion, social capital and health. Using the theoretical framework of economic sociology, her empirical work employs multiple methodologies including social network analysis, GIS, econometrics and discourse analysis.

Notes

1 This corresponds to Elite Development Theory, which Selwyn (Citation2016) described as seeing: “the poor” as human inputs into or, at best, junior partners within elite-led development processes” (p. 781).

2 SKO orphanage is accused of abuse and neglect of the orphans in its care and corruption in the use of donations (see Winkler & Delacey, Citation2016; Chan, Citation2017). SKO closed in early 2020.

3 Care leavers are more at risk of exploitation and trafficking (Lumos, Citation2021, p. 45).

References

- ABC. (2010). Children of a lesser God. Australian Story. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://www.abc.net.au/austory/children-of-a-lesser-god/9172650.

- ABC. (2014). The house of Tara. Australian Story. Retrieved December 29, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRUwbzQipZI.

- Bandyopadhyay, R., & Patil, V. (2017). The white woman's burden’ – the racialized, gendered politics of volunteer tourism. Tourism Geographies, 19(4), 644–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1298150

- Banks, G., & Scheyvens, R. (2014). Ethical issues. In R. Scheyvens & D. Storey (Eds.), Development fieldwork: A practical guide (pp. 160–187). Sage.

- Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

- Bott, E. (2021). My dark heaven’: Hidden voices in orphanage tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 103110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103110

- Britton, S. (1982). The political economy of tourism in the Third World. Annals of Tourism Research, 9(3), 331–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(82)90018-4

- Cammarota, J. (2011). Blindsided by the Avatar. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 33(3), 242–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2011.585287

- CCT. (2019). 2019 was a year for winners in ICT. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://cambodianchildrenstrust.org/2019-was-a-year-for-winners-in-ict/

- CCT. (2020). 2020 Annual Impact Report. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://cambodianchildrenstrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/CCT_AnnualImpactReport-2020_WEB_FA.pdf

- CCT. (n.d.). Exit strategy. Retrieved October 17, 2017, from https://cambodianchildrenstrust.org/village-hive/exit-strategy/

- Chan, S. (2017). Testimony to the Australian Parliamentary Inquiry into Modern Slavery. Retrieved October 3, 2021, from https://cambodianchildrenstrust.org/listen-sinet-chan-and-tara-winkler-give-evidence-at-2017-moden-slavery-inquiry/.

- Chan, S. (2021). Sinet addresses the UN. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://cambodianchildrenstrust.org/sinet-addresses-the-un/.

- Cheney, K. E., & Rotabi, K. S. (2014). Addicted to orphans: How the global orphan industrial complex jeopardizes local child protection systems. In C. Harker, K. Hörschelmann, & T. Skelton (Eds.), Conflict, violence and peace: Geographies of children and young people (pp. 89–107). Springer.

- ChildSafe Movement & G Adventures. (2018). Child welfare and the travel industry: Global good practice guidelines. Retrieved October 4, 2021, from https://media.gadventures.com/media-server/dynamic/admin/flatpages/17-502-00-PT-GL_Child_Welfare_Guidelines_v4_03_2018.compressed.pdf.

- Cole, T. (2012). The white-savior industrial complex. The Atlantic. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/03/the-white-savior-industrial-complex/254843/.

- Develtere, P., & De Bruyn, T. (2009). The emergence of a fourth pillar in development aid. Development in Practice, 19(7), 912–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614520903122378

- FCF. (n.d.). Family Care First-React. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from www.fcf-react.org

- Flanagan, K. (2020). Promising practices – Strengthening families and systems to prevent and reduce the institutional care of children. In J. Cheer, L. Matthews, K.E. van Doore & K. Flanagan (Eds.), Modern day slavery and orphanage tourism (pp. 63–81). CABI.

- Freidus, A. L. (2017). Unanticipated outcomes of voluntourism among Malawi's orphans. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(9), 1306–1321. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1263308

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

- Ghosh, B. N. (2021). Dependency theory revisited. Routledge.

- Giroux, H., & Giroux, S. S. (2006). Challenging neoliberalism’s new world order. Cultural Studies < => Critical Methodologies, 6(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708605282810

- Global Study of Sexual Exploitation of Children in Travel and Tourism. (2018). The international summit of child protection in travel and tourism. Retrieved October 4, 2021, from https://www.protectingchildrenintourism.org/resource/declaration-and-call-foraction-for-the-protection-of-children-in-travel-and-tourism-international-summit-bogota-2018/

- Guiney, T. (2015). Orphanage tourism in Cambodia: The complexities of “doing good” in popular humanitarianism [PhD thesis]. University of Otago.

- Guiney, T., & Mostafanezhad, M. (2015). The political economy of orphanage tourism in Cambodia. Tourist Studies, 15(2), 132–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797614563387

- Guttentag, D. (2011). Volunteer tourism: As good as it seems? Tourism Recreation Research, 36(1), 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2011.11081661

- Hall, C. M., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2020). Pandemics, transformations and tourism. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 577–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759131

- Harrison, D. (2012). Pro-poor tourism: Is there value beyond “whose” rhetoric? In T. V. Singh (Ed.), Critical debates in tourism (pp. 137–149). Channel View.

- Henry, J. (2019). Directions for volunteer tourism and radical pedagogy. Tourism Geographies, 21(4), 561–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1567577

- Hickel, J., Sullivan, D., & Zoomkawala, H. (2021). Plunder in the post-colonial era. New Political Economy, 26(6), 1030–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1899153

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after Covid-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- hooks, b. (1993). bell hooks speaking about Paolo Freire. In P. McLaren & P. Leonard (Eds.), Paolo Freire: A critical encounter (pp. 145–152). Routledge.

- Illich, I. (1990). To hell with good intentions (1968 speech). In J. C. Kendall (Ed.), Combining service and learning (pp. 314–320). National Society for Internships and Experiential Education.

- JSCFADT. (2017). Orphanage trafficking. Retrieved September 3, 2021, from https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Joint/Foreign_Affairs_Defence_and_Trade/ModernSlavery/Final_report/section.

- Kabeer, N. (2011). Between affiliation and autonomy: navigating pathways of women's empowerment and gender justice in rural Bangladesh. Development and Change, 42(2), 499–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01703.x

- Kuokkanen, R. (2011). Indigenous economies, theories of Subsistence, and women: Exploring the social economy model for Indigenous governance. American Indian Quarterly, 35(2), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.5250/amerindiquar.35.2.0215

- Lediard, D. E. (2016). Host community narratives of volunteer tourism in Ghana: From developmentalism to social justice [Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1862]. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1862.

- Lumos. (2021). Cycles of exploitation. Retrieved December 19, 2021, from https://lumos.contentfiles.net/media/documents/document/2021/12/LUMOS_Cycles_of_exploitation.pdf.

- Manzo, K. (1991). Modernist discourse and the crisis of development theory. Studies in Comparative International Development, 26(2), 3–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02717866

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

- Meyer, D. (2012). Pro-poor tourism: Is there actually much rhetoric? And if so, whose? In T. V. Singh (Ed.), Critical debates in tourism (pp. 132–136). Channel View.

- Mowforth, M., & Munt, I. (1998). Tourism and sustainability. Routledge.

- Nee, M. (2020). CCT Program Evaluation Report. Unpublished consultancy report in authors’ possession.

- Pelling, O. (2019). The secret world of modern-day slavery. Smith Journal, 30 (Online). Retrieved May 7, 2021, from https://oliverpelling.com/australia-modern-slavery.

- Piekkari, R., & Welch, C. (2018). The case study in management research. In C. Cassell, A. L. Cunliffe & G. Grandy (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods (pp. 345–358). Sage.

- Pierce, C. S. (1978). Pragmatism and abduction. In C. Hartshorne & P. Weiss (Eds.), Collected papers (pp. 180–212). Harvard University Press.

- ReThink Orphanages. (n.d.). Facts and figures about orphanage tourism. Retrieved October 7, 2021, from https://rethinkorphanages.org/problem-orphanages/facts-and-figures-about-orphanage-tourism.

- Rogerson, C. M., & Saarinen, J. (2018). Tourism for poverty alleviation: Issues and debates in the Global South. In C. Cooper, S. Volo, W. C. Gartner, & N. Scott (Eds.), The Sage handbook of tourism management (pp. 22–37). Sage.

- Ryan, R. (2015). 'Making mistakes with people's lives': The ethics of orphanages and voluntourism. ABC Online. Retrieved October 17, 2021, from https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/latenightlive/tara-winkler-the-ethics-of-orphanages-and-voluntourism/6819486.

- Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Sauer, J. B., & Lyle, R. R. (1997). Narrative, truth, and self. The Personalist Forum, 13(2), 195–222.

- Scheyvens, R. (2002). Tourism for development: Empowering communities. Prentice-Hall.

- Scheyvens, R. (2012). Pro-poor tourism: Is there value beyond the rhetoric? In T. V. Singh (Ed.), Critical debates in tourism (pp. 124–132). Channel View.

- Scheyvens, R., & Storey, D. (Eds.). (2014). Development fieldwork: A practical guide. Sage.

- Schwandt, T. A. (1998). Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research (pp. 221–259). Sage.

- Selwyn, B. (2016). Elite development theory. Third World Quarterly, 37(5), 781–799. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1120156

- Sharpley, R., & Telfer, D. J. (2015). Tourism and development: Concepts and issues. Channel View.

- Simpson, K. (2004). ‘Doing development’: The gap year, volunteer-tourists and a popular practice of development. Journal of International Development, 16, 681–692. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1120

- Sin, H. L. (2010). Who are we responsible to? Locals’ tales of volunteer tourism. Geoforum, 41(6), 983–992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.08.007

- Steiner, A. (2020). How to avert the worst development crisis of this century. UNDP. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https://www.undp.org/blog/how-avert-worst-development-crisis-century.

- UNICEF. (2018). A statistical profile of child protection in Cambodia. Retrieved October 11, 2021, from https://www.unicef.org/cambodia/reports/statistical-profile-child-protection-cambodia.

- Wearing, S. (2001). Volunteer tourism: Experiences that make a difference. CABI.

- Wearing, S., & McGehee, N. G. (2013). Volunteer tourism: A review. Tourism Management, 38, 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.03.002

- Wearing, S., Mostafanezhad, M., Nguyen, N., Nguyen, T., & McDonald, M. (2018). Poor children on Tinder’and their Barbie Saviours: towards a feminist political economy of volunteer tourism. Leisure Studies, 37(5), 500–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1504979

- Winkler, T. (n.d.). Voluntourism & volunteering in Cambodia. Retrieved July 7, 2021, from https://cambodianchildrenstrust.org/volunteer-in-cambodia/.

- Winkler, T., Delacey, L. (2016). How (not) to start an orphanage… by a woman who did. Allen & Unwin.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage.